Corporate Financial Distress Guidance note (HTML)

Updated 25 February 2026

1. Context

The contents of this Guidance Note are relevant to all central government departments, their executive agencies, and non-departmental public bodies.

Where suppliers are contracted to deliver services to government there is a risk that interruption to delivery could put the government in breach of its statutory obligations, or have a significant adverse impact on public health and safety or national security. One cause of interruption to delivery could be the financial failure of the supplier.

The Economic and Financial Standing (EFS) of bidders should be assessed at the selection stage in order to identify the overall financial risk of a supplier. Subsequently, the financial health of suppliers can deteriorate after procurement, either suddenly (for example because of the loss of a major contract or major litigation) or over time (for example, as a result of gradual changes to the profitability of a sector).

Contracting authorities should therefore monitor the financial health of their Key Suppliers (i.e. those providing critical services to government) on an ongoing basis. Key Suppliers should be monitored even if the contract has been procured through a framework (though this responsibility is shared with the contracting authority that procured the framework). Early recognition of the risk of supplier failure should allow contracting authorities to be better prepared to deal with such failure, and limit its impact on the continuity of critical public services.

1.1. Purpose of the guidance

The purpose of this guidance is to provide a basic understanding of corporate financial distress for individuals engaged in the management of government contracts.

Specifically, the guidance is intended to:

- Assist in identifying indicators of financial distress at an early stage;

- Provide an overview of different restructuring outcomes (solvent and insolvent);

- Suggest practical steps, in the short and medium term, for contract managers where they have concerns over a supplier’s financial health (including escalation outside the contracting authority);

- Support contingency planning to ensure contracting authorities have plans to manage continuity of supply;

- Provide an understanding of the key stakeholders and their various positions; and

- Provide a list of key contacts for additional support and advice.

This guidance is not intended to be a detailed technical manual and should be read in conjunction with existing government guidance, including guidance on Assessing and Monitoring the Economic and Financial Standing of Suppliers.

Where contracting authorities and/or individuals are unsure of the approach to take, they should seek specialist support from within HM Government (see Section 6. Additional Support).

1.2. Glossary

The following terms are used throughout this document:

| Financial Distress Event | An indicator of possible financial distress defined in a contract which, if it arises, gives the contracting authority the right to require the supplier to put forward a remediation plan and could ultimately lead to the contracting authority terminating the contract. There are a number of contractually defined Financial Distress Events in the Model Services Contract (in the Financial Distress Schedule) and Mid-Tier Contract (in the Definitions Schedule) |

| Model Services Contract | The Cabinet Office’s Model Services Contract (“MSC”) forms a set of model terms and conditions for major/ complex services contracts that is published for use by government departments and many other public sector organisations. |

| Mid-Tier Contract | The Cabinet Office’s Mid-Tier Contract forms a set of model terms and conditions for less complex services (and goods) contracts that is published for use by government departments and many other public sector organisations. |

| Strategic supplier | A supplier to government listed as a strategic supplier. |

| Key supplier | Contracting authorities should identify their key contracts and suppliers using the Contract Tiering Tool. “Key Suppliers” include all suppliers of critical (Gold) contracts or important (Silver) contracts. Contracting authorities should also consider whether any other suppliers should also be regarded as “Key Suppliers”. |

2. Understanding corporate financial health

2.1. What is corporate financial health and why is it important?

Corporate financial health refers to an organisation’s overall financial stability and performance. A key component of corporate financial health is whether an organisation has sufficient cash to continue operating (in the short to medium term) without significant concern over its ability to meet its liabilities. Good financial health allows an organisation to maintain the confidence of its stakeholders and invest in its business with a view to generating future growth.

From the perspective of contracting authorities, financial health is a measure of ensuring an organisation has the resources to deliver its contractual obligations over the life of the contract. The more critical the contract, the more emphasis needs to be placed on good supplier financial health. Under the Procurement Act 2023, supplier financial capacity should initially be assessed as part of the Conditions of Participation or, for dynamic markets, Conditions for Membership prior to contract award.

Financial health is therefore important, not just to an organisation’s owners and employees, but also to its other stakeholders, such as the government as a customer.

Where financial health declines and an organisation experiences greater financial challenge, the risk of it failing and not being able to maintain service provision increases.

2.2. What is financial distress and what are the causes?

Broadly, an organisation experiences financial distress when it has, or expects to have, difficulty paying its liabilities as they fall due. The root causes of this distress can sometimes be identified before symptoms show.

2.2.1 Potential causes of financial distress

Management:

Poor decisions made by an overly dominant CEO or an ineffective board, or high management turnover can cause financial distress.

Business specific:

There are many triggers of financial distress that are specific to the organisation. These can include: large loss-making contracts, loss of key customers, fines from regulators indicating poor practices, cyber-attacks, high turnover of staff, and unsupportable debt can cause an entity to fail.

Management information:

Poor quality management information can render a business unable to detect a deterioration in performance. In many cases poor management information can lead to poor cash flow management resulting in insolvency.

Market issues:

Wider economic trends or shocks can impact some organisations more than others. Examples include; inflationary pressures, global supply chain disruption, and volatile exchange rates.

Financial management:

Unrealistic budgeting, poor investment decisions, an overemphasis on profit as opposed to cash flow/liquidity and aggressive accounting policies are all examples of poor financial management that could cause distress within an organisation.

There is no single indicator of distress, but distress can manifest itself through poor profitability and cash flow. If not addressed, the organisation ultimately risks running out of cash and having to enter a formal insolvency procedure.

Many organisations experience financial challenges at some point. In some cases, this may not be evident externally, and in other cases, the organisation may be visibly distressed. Each situation will be different and will require a different response.

Organisations are very sensitive to signs of financial distress becoming public as this in itself can have significant adverse consequences:

- Loss of banking facilities: An organisation’s lenders may seek to reduce their exposure by reducing the size of the organisation’s credit facility (i.e. the organisation may not be able to borrow as much) or placing conditions (e.g. covenants) on the terms of loans;

- Loss of trade credit insurance: Inability of the supplier’s supply chain to secure insurance protecting them against the risk of the supplier not paying them for goods or services;

- Loss of trade credit: Its suppliers may start to offer less generous credit terms or demand cash up front before supplying the organisation;

-

Requirement to provide bond collateral: Providing cash as guarantee for project delivery may become more common, placing further risk on cash;

-

Loss of custom: Customers may begin to lose confidence in the organisation’s ability to continue to trade as a going concern and seek alternative suppliers; and

- Loss of key staff: Employee morale may suffer and the organisation may start to lose key staff and other employees as they seek safer employment elsewhere.

The impact of these issues often exacerbates the financial distress an organisation is experiencing.

2.3. Identifying the signs of financial distress

When monitoring an organisation’s financial health, it is important to consider a broad range of potential indicators beyond its profitability and cash position. Both financial and non-financial indicators can be helpful. Some of the more common potential indicators are set out below.

2.3.1. Potential financial indicators

Revenue declining or not growing as budgeted:

This can put pressure on profits and cash flow if the organisation is unable to reduce its costs in response. It is particularly relevant for organisations with a significant proportion of fixed costs (i.e. where costs do not fall in line with revenue).

Margin declines and/or losses:

These can be a sign that an organisation is unable to pass on cost inflation to its customers, or that it is lowering its prices, or taking on less profitable work to fill its capacity.

High debt-to-equity ratios:

If an organisation has a high proportion of debt relative to equity on its balance sheet, it will probably have higher finance costs, and its profits and cash flow will be more exposed to any deterioration in performance.

Covenant breaches or waivers:

A lender will generally attach conditions (known as covenants) to the credit facility it provides, such as the organisation maintaining a certain level of free cash flow to service its debt obligations. If these covenants are breached, this can cause the organisation to default on its credit agreement, allowing the lender to demand immediate repayment of all its outstanding debt. An organisation may seek a waiver of these covenant requirements for a period of time to facilitate their recovery.

Falling credit ratings:

Independent credit ratings and other agencies monitor the financial health of organisations. If the credit rating of a supplier is downgraded, or its credit score falls, this is a good indicator that it may be experiencing financial distress.

High borrowing costs:

When an organisation borrows money its cost of borrowing (typically the interest rate it pays) will reflect lenders’ perception of its financial health. If its borrowing cost is high, relative to its competitors, or is increasing, this can be a sign that it is experiencing financial distress. A lender is likely to have access to a greater level of financial information on the organisation than is publicly available.

Not paying creditors on time (‘creditor stretch’):

If an organisation is experiencing cash pressures it will often resort to paying its creditors later than they are contractually due to be paid. Where trade creditors are rising as a proportion of cost of sales, this may indicate financial distress. Creditor days, the average number of days a company takes to pay its suppliers, can support monitoring. For large companies, another way to identify late payments would be to review published payment practice reports[footnote 1].

Increased focus on recovering cash:

An organisation with cash flow concerns may place a greater emphasis than previous on being paid early/on time, or may settle disputes for less than expected in order to resolve them and realise payment.

Refinancing:

If an organisation is repeatedly refinancing maturing debt without reducing the principal, this may indicate that it is unable to meet its existing obligations.

Trade credit insurance:

Withdrawal or reduction of trade credit insurance limits generally indicates the insurer judges the supplier’s trade debtors, or the supplier’s ability to collect from them, to be at increased risk of non‑payment.

Sale of assets:

An organisation may sell assets or business units to improve its cash position. This can address short-term cash shortfalls, but may be at the expense of future revenue generated by the disposed assets.

Share price performance:

Where an organisation is quoted, underperformance of its share price relative to its competitors can indicate investor concern over its future profitability or financial position.

Audit opinion:

A company’s audited accounts are a significant indicator of its financial health. When an auditor audits a company, they not only have an obligation to consider whether the financial statements represent a ‘true and fair’ view of the company’s performance, but also the company’s ability to continue as a going concern. If, in the auditor’s opinion, there is substantial doubt over its ability to continue to trade in the future (defined as the following twelve months), the auditor must include a ‘going concern’ qualification in their opinion on the company’s financial statements[footnote 2].

2.3.2. Potential non-financial indicators

Poor relationship with lenders:

If the relationship between an organisation and its lenders has deteriorated, this can often be a sign of financial distress.

Poor operational performance:

Poor operational performance, such as declining Key Performance Indicators, declining quality, or supply chain concerns can often result in poor financial performance; for example, it may suggest the existence of management issues or that an organisation is trying to cut the cost of providing the service as a result of short-term financial pressure. Declining service quality can also lead to falling new business or to regulatory action when a supplier is not meeting required standards.

Unexpected resignations of key management or high staff turnover:

Staff morale is often low in poorly performing companies, resulting in a high turnover of staff. If a key member of management unexpectedly resigns, this can also be an indicator of distress.

Weak management:

It is helpful to understand the structure of the management team and to assess the key members of management. Organisations with poor corporate governance, or where the directors lack key skills, are often less effective.

Delayed filing of statutory accounts or late provision of management information:

Management teams will often delay providing information showing poor performance. Where company statutory accounts are filed late at Companies House, the company unexpectedly changes its financial year end dates, or management information you expect to receive is delayed, even by just a few days, this can be an indicator of financial distress.

Failed corporate transactions:

An unsuccessful or withdrawn corporate transaction may indicate financial distress, for example, if a potential acquirer had the opportunity to scrutinise an organisation and subsequently withdrew.

Change in level of engagement with contracting authority:

Where a contract manager has previously enjoyed a high level of engagement with a supplier and has been granted access to additional information, such as management information, the withdrawal of that access should be investigated. Additionally where a supplier seeks to renegotiate aspects of the contract, the reasons for this should be understood.

Inability to retain supply chain members:

Where key or longstanding supply‑chain partners are unwilling to continue trading with the organisation, or insist on onerous conditions as a prerequisite of business, this indicates the organisation is experiencing operational and/or financial difficulties.

These non-financial indicators can often provide an early warning of financial distress, as published financial information is often backward-looking.

A summary table of financial and non financial indicators of distress has been included in Appendix 1.

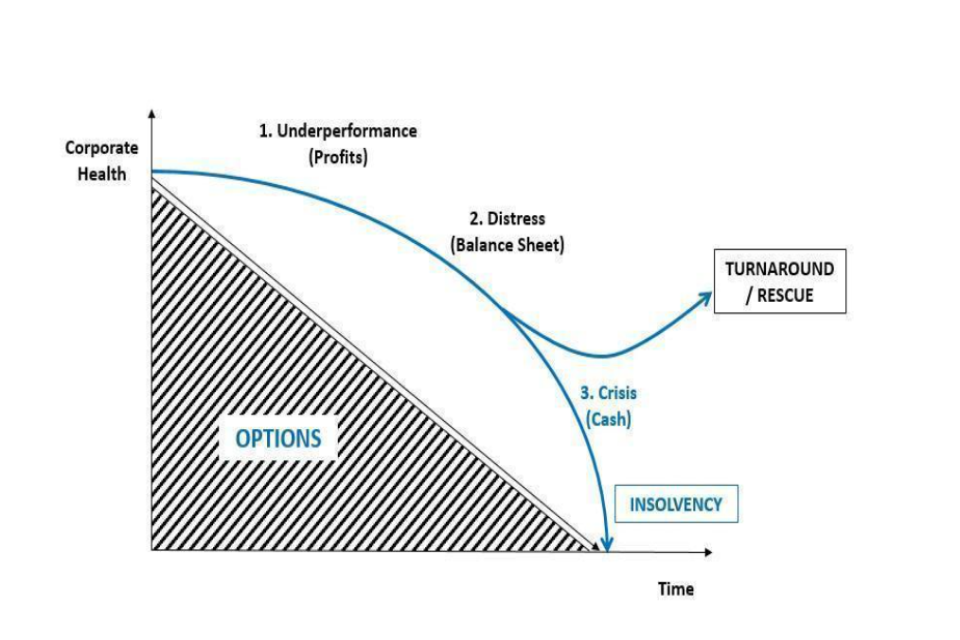

2.4. Distressed organisation decline curve

Financial decline often first manifests itself through worsening profitability, then, over time, as a weakening balance sheet. Finally, a crisis arises as the organisation runs out of cash (as illustrated in the following decline curve). Financial decline can arise quickly, therefore an entity’s financial statements may not include signs of distress.

The number of options available to an organisation will decrease as it becomes more distressed; therefore, the earlier issues are identified and addressed, the greater the prospect of recovery.

3. Guidance: Monitoring and managing concerns over suppliers’ financial health

3.1. Monitoring suppliers’ financial health

The financial health of suppliers can change throughout the term of a contract. Therefore, contracting authorities should regularly monitor the Economic and Financial Standing (EFS) of their suppliers, to satisfy themselves that i) the supplier is delivering the contract to the agreed service levels; and ii) the supplier has sufficient financial strength to continue to provide the services.

Further information regarding contract criticality and the monitoring of suppliers following contract award can be found in the Guidance Note Assessing and Monitoring the Financial and Economic Standing of Suppliers.

Contracting authorities should identify their Key Suppliers and monitor their EFS on an ongoing basis. Its frequency should reflect the criticality of the contracts held. The “Financial Distress” / “Financial Difficulties” Schedules in the Model Services Contract and Mid-Tier Contract provide model contractual provisions dealing with monitoring the ongoing EFS during the life of a contract.

Contracting authorities are responsible for overseeing and monitoring strategically important companies in their sector, including any private sector suppliers.

The Markets, Sourcing and Suppliers team, a central team within the Government Commercial Function, provides supplier, market and sector intelligence to departments and is responsible for monitoring the government’s strategic suppliers[footnote 3].

For all critical (Gold) or important (Silver) contracts, as well as any other Key Suppliers, financial monitoring should be carried out at least annually, and include a review of performance against EFS metrics and Financial Distress Event triggers under the contract. In addition, reviewing contractual performance including monitoring KPIs as required under the Procurement Act 2023, and reviewing wider commercial behaviours (including supply chain payments, requests to customers to be paid early, payment mechanism and recoverable cost challenges) can support financial monitoring.

Financial monitoring should be undertaken using financial results and public and/or reported information under the contract. Contracting authorities should utilise any forward-looking financial information provided, such as management accounts or cash flow forecasts, understanding the limitations of information that is not independently verifiable.

More regular reviews are particularly recommended for suppliers flagged by contracting authorities as critical for their services, or which are perceived to have anything other than a low risk of financial failure.

The scale of the financial risk will depend on:

- The level of financial distress at the supplier and risk of collapse (see Section 4 ‘What are the options for an organisation in financial distress?’);

- The criticality of the service;

- The risk of service interruption as a result of the distress and/or collapse; and

- The extent of prior preparation within the contracting authority/government.

Each situation will be different. However, there are a number of steps that contracting authorities can take in the short and medium term to better understand the situation and put themselves in a stronger position.

This guidance should be read in conjunction with contracting authorities existing guidance, processes and protocols for dealing with such events.

If contracting authorities require further support in establishing appropriate processes relating to ongoing financial monitoring and financial distress, they should contact the Cabinet Office Markets, Sourcing and Suppliers team at: markets-sourcing-suppliers@cabinetoffice.gov.uk.

3.2 Actions where financial distress is identified

For the avoidance of doubt, these situations are highly sensitive and therefore any concerns regarding a supplier’s financial health must be held in strictest confidence.

3.2.1 Short Term Actions

When concerns emerge over the financial health of a supplier, contracting authorities should consider the following steps:

1. Articulate the issue:

Depending on the circumstances, action may need to be taken quickly. Being able to articulate clearly and concisely the reasons for your concerns and, so far as you can ascertain them, the potential implications for the contracting authority or government, is important.

Key information includes:

- The basis of your concern(s) (e.g., profit warning, external credit analysis, notice from the supplier, intelligence gathered from the supply chain);

- The dates (when did this first arise and/or when was the last piece of information?);

- The perceived extent of the financial distress (is the supplier lightly challenged and does it just require further monitoring, or is it deeply distressed and at risk of being unable to continue paying its debts as they fall due?);

- The potential implications for the contracting authority or government (What services does the supplier provide and is there a risk of interruption? Are there wider risks, for example, might the supplier provide other public sector services or hold confidential data? Are there reputational risks?).

2. Escalate internally:

Engage colleagues from commercial, operational, risk management and business continuity teams to identify any additional information to support your concerns. For example; have commercial colleagues identified a deterioration in contract performance, have financial concerns been raised before over this supplier, have colleagues experienced this issue with other suppliers and what action did they take? Discussions with the operational teams utilising the contract on a day to day basis can give a clearer understanding of the impact of a sudden cessation of services, so are crucial to helping form a proportionate continuity plan.

Gathering a broad range of information (financial and nonfinancial) will provide a more rounded view of the issue.

3. Engage finance teams:

Discussing the position with the contracting authority’s finance team may:

- Provide additional insight into the supplier’s behaviour. For instance, financially challenged suppliers may request that invoices are paid earlier than usual (or in advance) to improve their own cash flow; and

- Provide an independent and experienced view of the concerns.

4. Ensure inclusion on organisational risk register for ongoing monitoring:

The decision to escalate within a contracting authority will depend on a number of factors. The most critical will be the likelihood, and timing, of a break in supply - if the risk is high and imminent then the issue should be escalated immediately.

5. Increase supplier engagement:

Individual contract managers will normally have liaised with the supplier to seek reassurance prior to escalating the issue. Where significant concerns remain regarding a supplier’s ability to maintain service provision, contracting authorities should consider engaging at higher levels with the supplier to understand whether the concerns are valid.

Depending on the sensitivity and complexity of the issue, engagement should be led by officials with sufficient knowledge of the contract and organisation, escalating as appropriate considering the overall risk exposure.

Key issues to understand from the supplier include:

- Confirmation, or not, of the facts that have led to the contracting authority’s concerns and our interpretation of them;

- The implications for the supplier organisation (e.g. is it business as usual, what action is the supplier taking, what are the timescales involved);

- The implications for the contracting authority (i.e. is there a risk to service continuity, what is the timing of any potential event);

- Who the contracting authority should contact if it has further concerns or requires further information.

6. Contract modifications to support distressed suppliers:

Contract modifications to support distressed suppliers: The contracting authority may explore contract modifications to support a supplier’s recovery, ensuring all adjustments remain compliant with the Procurement Act 2023. This involves considering what flexibilities will be permissible under section 74 and Schedule 8 (Permitted Contract Modifications). Key options include: - Reprofiled payment schedules: To improve the supplier’s cash flow and liquidity, and better align payments with the suppliers’ contract-related cash outflows; - Scope adjustments: Where feasible, reducing non-essential service requirements, whilst understanding the potential impact on overall contract value; - Price adjustments: justifiable variations that maintain supplier solvency and performance whilst still demonstrating value for money. This requires careful scrutiny; and - Contractual changes already provided for: Implementing existing clauses allowing changes for events such as materialisation of a known risk, provided that the nature of the contract is not fundamentally changed.

Any proposed modifications must be assessed for compliance with the Procurement Act 2023, expert legal and commercial advice should be sought.

7. Review and update contingency plans:

Contracting authorities that continue to have concerns regarding the ability of the organisation to provide ongoing services should review their current contingency plans, and consider updating them or, where appropriate, asking the supplier to update their plans (see Section 3.3 ‘Developing and maintaining contingency plans’).

Where the contract was procured under a Crown framework agreement, the Crown Commercial Service (‘CCS’) may also advise on contractual rights or processes. CCS’s Public Sector Contract, which underpins many CCS frameworks, contains model contractual provisions dealing with defined Financial Distress Events.

Contracting authorities should ensure that they have access to:

- Copies of the signed versions of all relevant contracts with the supplier (including all of the schedules and any deeds of variation and change control notes, as well as copies of subcontracts, where the contract provides for this information);

- Contemporary contract management and administration documents (e.g. commercial data, relevant warranties, deeds executed, vesting certificates, handover documentation); and

- Any service continuity plans, exit plans and resolution planning information to which they are entitled under the contract (see guidance on Resolution Planning). Both the Model Services Contract (on a mandatory basis) and Mid-Tier Contract (on an optional basis) contain schedules in relation to service continuity plans, and exit management - including the development of exit management plans.

The contracting authority’s legal team should be engaged to provide further advice regarding the rights and obligations of both parties to support this process.

3.3. Escalation within government

Where a distressed supplier delivers services to multiple government departments, it may be more appropriate to coordinate the government’s strategy and overall response.

Generally Cabinet Office leads on strategic suppliers in distress, with support of departments with the largest or most critical exposure.

For other suppliers in distress with contracts across multiple departments, Cabinet Office will consider the exposure and criticality of contracts, and will make a recommendation to designate a lead government department to the Minister for the Cabinet Office and Cabinet Office Permanent Secretary.

If there is no clear lead department, or if the failure of the supplier would have wider implications for government, Cabinet Office may be designated as the lead government department.

Cabinet Office will offer support to the designated lead government department in scoping the work and with communication to other government departments, but responsibility for managing the risk, e.g., appointing external advisers/legal support lies with the lead government department.

Where a coordinated response is adopted, features typically include:

- Team: A working group may need to be established depending on the severity of the situation. Potential participants include Cabinet Office (Markets, Sourcing and Suppliers team), the lead HMT spending team for the relevant department, the HMT Special Situations team, the UK Government Investments (UKGI) Special situations team , Crown Commercial Service (where relevant) and Government Legal Department (GLD) as well as any external expertise (financial advisers, insolvency practitioners, lawyers) that may be required. Care should be taken to ensure external advisers do not have any conflicts of interest, and care should be taken to share only crucial information.

- Press lines and communication: Establish contact with the lead department’s press team to coordinate media responses across central government. Clarify the level of communication required. All documentation should be marked with the appropriate security classification and weekly updates should be written for relevant officials and ministers as necessary.

- International engagement: Where distressed organisations are based outside of the United Kingdom or have significant public contracts internationally, engagement with the international governments will often be required.

- Other workstreams: Every situation will be different depending on the breadth and depth of the supplier’s contracts. Other workstreams may be needed.

One potential workstream may be to identify and resolve any disputes or issues with contracts which may be contributing to or exacerbating the difficulties of the supplier (provided the risks and/or impact to government can be managed).

Another potential workstream may be for the lead department to procure expert financial, legal and insolvency advice including all necessary project and budgetary approvals.

The workstreams above are indicative and will evolve over time. Certain situations may have more time to establish a programme management team while other situations may not, so prioritisation and judgement is required.

3.4. Developing and maintaining contingency plans

There are broadly two aspects to maintaining services in the event of supplier insolvency:

- Short-term maintenance of the services provided, should a supplier become insolvent with little or no notice, or there is a controlled cessation of the service; and

- Putting in place an alternative commercial solution for the longer term through processes such as retendering or, if necessary, bringing the services in-house, either into the contracting authority or into a government owned company.

Contingency plans to maintain continuity of critical outsourced services should include both short-term and medium-term components.

Many contracts, including the Model Services Contract (on a mandatory basis) and Mid-Tier Contract (on an optional basis), contain obligations on suppliers to provide:

- Business continuity and disaster recovery (BCDR) plans to deal with interruptions to key dependencies;

- Supply chain mapping obligations setting out the details and functions of entities in the supply chain; and

- Exit plans and provision of exit information including for an emergency exit.

Contracting authorities should check whether these are available, confirm that they cover BCDR events and exits arising from the insolvency of a supplier or a key member of its group, and ensure they are regularly updated. Contracting authorities should consider the implications of insolvency on BCDR plans, recognising that the insolvency practitioner’s agreement may be necessary, and that their decision to grant consent will be subject to their statutory obligations (See Section 4.3 for more details on insolvency).

Suppliers of Gold (critical) contracts are also subject to obligations to provide additional resolution planning information (see guidance on Resolution Planning). Where resolution planning information is available, it should provide a wider view on the potential implications of a supplier’s insolvency and the key dependencies to which continued service provision is subject.

Contracting authorities should maintain their own internal contingency plans for critical services dealing with risks arising from supplier insolvency. These should build on any plans provided by the supplier and consider items such as the contracting authority’s options to re-procure the services or bring them in-house at short notice. See Contingency Planning template.

As with all contingency planning, the extent of preparations should be risk-based to ensure the effort and level of readiness is proportionate to the risk.

Contingency plans should involve staff from commercial, finance, operational, risk management and business continuity teams from an early stage.

4. What are the options for an organisation in financial distress?

4.1. Why are the options for an organisation in financial distress important?

It is important to understand the implications of various options for organisations in financial distress as they will affect the ability of the entity to maintain delivery of the contract. Solvent restructuring options are far more likely to result in contract delivery being maintained to an acceptable level. Insolvent options may result in the eventual termination of service delivery, likely with little notice, which can lead to exceptional costs and service disruption.

4.2. Solvent restructuring options

Where organisations are experiencing financial distress, early intervention is key. The earlier that the directors of an organisation recognise the challenges, the more time and options they have to try to turn it around and avoid insolvency.

There are a number of possible restructuring options open to an organisation before it needs to contemplate insolvency. These are set out below.

4.2.1. Turnaround plan

The starting point is generally a credible turnaround plan:

- An organisation undertakes a detailed review of itself and its business to understand its current financial position and the factors (operational or financial) that are driving its underperformance;

- The management team then formulates a series of plans to address whatever issues it has identified and return the business to profitability/cash generation over a period (usually one to two years);

- This might include the wind-down or sale of unprofitable business units and contracts. Customers may be asked to renegotiate contracts with higher prices and more favourable terms for the supplier in order to ensure continuity. Where contracting authorities receive such approaches from suppliers, they should engage their commercial teams as early as possible and consider any procurement law, subsidy control implications and other issues.

4.2.2. Options to improve liquidity

In parallel with a turnaround plan, an organisation might explore a number of other options to provide access to cash or reduce debt such as:

Amend and extend:

The terms of the organisation’s borrowings are renegotiated, and the repayment profile extended to provide a greater level of headroom or breathing space while the turnaround plan is executed;

New money:

Additional cash is injected into the organisation sufficient to meet an expected shortfall. Ideally, this would be provided by the shareholders, but it may be provided in conjunction with (or sometimes solely by) the lenders. If this is in the form of debt, the overall level of borrowings will increase further, so the way this is structured is important.

In this option, contracting authorities may sometimes be asked, as key customers, to provide financial support to the organisation alongside other stakeholders/lenders. Extreme care must be taken in this situation to avoid i) breaching subsidy control rules and procurement law, and ii) a commercial agreement that does not represent value for money. If this is an option, contracting authorities should contact UK Government Investments (UKGI) for advice immediately.

Debt for equity swap:

The lenders agree to write-off a proportion of a company’s borrowings in return for an ownership (i.e. equity) stake in the company meaning the existing shareholders’ percentage ownership is significantly diluted or wiped out.

This will reduce the company’s debt and could provide the lenders with “upside” in the long term should the turnaround plan be successful. This is likely to be a last resort however as i) most lenders are not in the business of owning distressed businesses, and ii) existing shareholders are typically very unwilling to surrender ownership.

Asset sale:

The organisation may sell strategically valuable or non-core assets/business units to raise cash. This can then be used either to repay existing borrowings or to meet future cash requirements.

If successful, the organisation will emerge from the turnaround process in a stronger and more sustainable position, and be able to continue servicing its contracts without ever having entered insolvency.

4.3. Insolvent options

In this and subsequent sections we refer to limited companies and describe the position in England and Wales; slightly different insolvency rules apply to other forms of organisation. There are separate, equivalent rules for companies incorporated in Northern Ireland. The insolvency rules for companies incorporated in Scotland are distinct in some respects.

4.3.1. What is insolvency?

Insolvency occurs when a company is unable to pay its debts as they fall due.

To determine whether a company is insolvent, either or both of the following two tests apply:

Cash flow test:

Is the company unable to pay its debts as they fall due?

Balance sheet test:

Are the company’s assets worth less than its liabilities, taking into account its contingent and prospective liabilities?

These tests are not mutually exclusive. A company can be insolvent if the answer to either of these questions is yes. This is a complex area of law; however, in practice, courts more commonly find a company is insolvent on the basis of the cash flow test as this is demonstrably easier for creditors to evidence.

4.3.2. Directors’ responsibilities

If the directors continue to trade when there is no reasonable prospect of avoiding an insolvent liquidation they risk being liable for wrongful trading. As soon as the directors become aware that the company may not pass either of the tests, they are likely to seek professional advice from the company’s lawyers and financial advisers.

While a company is trading solvently, the duties of the directors are owed to the company for the benefit of its shareholders. However, once a company becomes insolvent or there is a doubt as to the solvency of the company, the directors must also consider or act in the interests of the creditors in order to minimise the potential loss to them.

If the directors breach these duties, they can be personally liable for losses and face disqualification from acting as a director or being involved in the promotion, formation or management of a company for a specified period.

There are three main forms of insolvency for companies:

- Administration;

- Company Voluntary Arrangements; and

- Liquidation.

4.3.3. Administration

Administration is designed to keep an insolvent company running while the insolvency practitioner (the Administrator) determines the most appropriate course of action (e.g. sale of the business as a going concern or a wind-down). It should be noted that during administration, contracts are not terminated automatically (aside from contracts with automatic termination clauses in the event of insolvency) as the business can continue to trade. In practice, however, administrations often involve ceasing trading relatively quickly; the legal entity may remain in administration for a period, but the trading of the business itself may be curtailed or halted as part of a wind-down. Any decision to keep trading, and which aspects of the business continue to trade, is at the discretion of the administrator who will assess the likelihood of recovery.

An administration is only viable if sufficient funds are available to cover the costs of the process and the ongoing working capital needs of those parts of the business the administrator chooses to continue.

The administrator can raise funds from the sale of assets, from cash available in the business, or from stakeholders providing money to support the process in the expectation that they will get a better return from an administration than the alternative of winding up the company through a liquidation. From a contracting authority’s perspective, it is worth highlighting that an administrator may well increase prices and seek to renegotiate contracts to cover their costs.

There are two ways in which a company can go into administration; by court order or by the lodging of certain documents at court (the “out of court” route). An application for a court order can be made by a number of people/organisations such as one or more creditors of the company, the company itself, its directors or a liquidator. The out of court route, which is more common and quicker, can be commenced by the company itself, its directors or by a party with a qualifying floating charge (for more details see section ‘5.3.8. Secured creditors’ ).

The directors will usually appoint an administrator (who must be a qualified insolvency practitioner), although certain secured creditors can also appoint the administrator. The administrator (instead of the board of directors) will run the company while considering future options.

The first objective of administration is to rescue the company as a going concern. If this is not possible, the objective is to achieve a better outcome for the company’s creditors than would be achieved in liquidation, or, failing that, to make a distribution to one or more secured or preferential creditors.

Once a company goes into administration there is a moratorium which prevents creditors and others from taking or pursuing legal proceedings against the company, giving the company time to get its affairs in order.

4.3.4. Pre-pack sales in administration

A pre-packaged (‘pre-pack’) sale of some or all of the assets of a company is an option available to the administrator. This happens when all or part of the business is sold immediately after the appointment of the administrator.

The terms of sale are negotiated by the directors prior to the appointment of the administrator but under their advice. The swift nature of the process preserves value for creditors by minimising damage to the business arising from public knowledge of its financial distress (see Section 2.2 ‘What is financial distress and what are the causes?’). It also enables the business to continue to trade, preserving jobs for employees and maintaining services for customers.

The business is normally sold without the burden of the company’s debts. This can lead to a negative perception that it is a method to shed debts at the expense of creditors, especially where the existing owners of the company buy the business back.

An administrator must not make a substantial disposal to a connected person within the first 8 weeks of administration unless they either:

- Obtain approval of the transaction from creditors; or

- Have received and considered a report obtained by the connected person from an independent evaluator on the reasonableness of the proposed disposal.

4.3.5. Moratorium

A moratorium is a formal, temporary protection for a company in financial distress, designed to provide breathing space to evaluate and pursue rescue and restructuring options. It is established under part 1 of the Corporate Insolvency and Governance Act 2020 and is initiated by the company, with supervision by the court. It is overseen by a licensed insolvency practitioner, known as a ‘monitor’, who ensures that the moratorium remains likely to result in a rescue of the company as a going concern.

During the moratorium, certain ongoing payments, such as a mortgage on a property or those necessary to preserve essential assets or contracts (for example, payment for leased equipment) must continue to be paid; however, other debts are frozen, and creditors cannot take actions while the moratorium is in effect.

The moratorium lasts for an initial period of 20 business days and may be extended by a further 20 business days without creditor consent, or for longer with creditor consent, by filing relevant statements with the court.

4.3.6. Scheme of Arrangement

A scheme of arrangement is a court-sanctioned agreement or compromise between a company and its creditors (and, where relevant, its members) designed to restructure or reorganise the company’s debts and obligations. It provides a controlled route to rescue or stabilise a business without immediate liquidation.

A scheme is usually proposed by the company, though administrators may also propose one. The process begins with the company presenting a scheme to the court, accompanied by a clear explanation of the proposed compromises and an implementation timetable. Creditors (and, where relevant, members) are grouped into classes with similar interests, and each class is invited to vote. In each voting class, the scheme must be approved by at least 75% in value and by a simple majority in number; if the required majorities are attained, the court may sanction the scheme, making it binding on all parties, including those that voted against, subject to the terms of the compromise. The court may also approve related arrangements, such as novation of contracts, to give effect to the scheme.

4.3.7. Restructuring Plans

A restructuring plan is a court-approved mechanism that operates as a formal plan to restructure a company’s liabilities. It enables a financially distressed company to reach a formal compromise with its creditors, allowing it to continue trading during and after the process while addressing liabilities in a sustainable and affordable way.

A restructuring plan is similar to a scheme of arrangement in that creditors are divided into ‘classes’, and each class votes on the proposed plan. A class votes in favour if 75% (by value) of the creditors in that class approve. However, unlike the scheme, not all classes need to vote in favour for the plan to be approved, provided the court is satisfied that none of the dissenting classes would be worse off under the plan than under the alternative. The court may sanction the plan if at least one creditor class with an economic interest has voted in favour.

4.3.8. Company voluntary arrangements

A company voluntary arrangement (“CVA”) allows a company to continue trading by agreeing a payment plan with its creditors.

Under a CVA, creditors agree to accept reduced or rescheduled repayments while the company is restructured. In order to proceed, a CVA will need the approval of 75% of creditors (by value).

A CVA must be authorised and overseen by an insolvency practitioner, to whom the company directors will submit a report on the company’s finances, together with a debt repayment plan. Importantly, the directors retain control of the company unlike in an administration.

The insolvency practitioner is responsible for ensuring that the company makes payments to creditors. If payments are not made as agreed, the CVA will fail and the creditors will take steps to agree a new CVA or to place the company into administration or liquidation.

If the CVA is completed with all payments made, the company will emerge from the process with its debts repaid.

4.3.9. Liquidation (“winding up”)

An insolvent company can be put into liquidation if it is determined that the company needs to be closed down and its business operations stopped in order to avoid accruing further debts. Once this happens, there is no chance for the company to rescue itself.

Liquidation can happen in two ways:

Compulsory liquidation:

This is a creditor led process where creditors petition the court to wind up the company and appoint a liquidator; or

Voluntary liquidation:

The directors determine that the company is insolvent and pass a resolution to appoint a liquidator, then approach creditors to secure their agreement to the process.

A creditors’ voluntary liquidation should be distinguished from a members’ voluntary liquidation. The latter is a solvent winding up of the company in which all creditors are paid in full and the company ceases to exist.

Once appointed, the directors’ executive powers cease, and the liquidator sells the assets of the company and, provided there are sufficient funds after his/her own costs have been covered, makes a distribution from the proceeds to creditors. The liquidator will normally be an insolvency practitioner. However, where there are insufficient assets to fund the appointment of an insolvency practitioner as liquidator, the Court will appoint an Official Receiver (an employee of the Insolvency Service).

In some instances, a court may appoint a liquidator on a provisional basis (known as a provisional liquidation), usually to safeguard the company’s assets and maintain the status quo until the court can determine the petition for liquidation. This may be necessary where there are allegations of fraud or misconduct.

There are other forms of insolvency, such as the appointment of a fixed charge receiver, an LPA (Law of Property Act) receiver, or an administrative receivership, but these are less common.

The purpose of these receivers is to realise security for the benefit of the security holder only, as opposed to administration or liquidation, which aim to benefit all creditors - both secured and unsecured (refer to Section 5.3 ‘Who are the principal stakeholders in an insolvency situation?’).

5. Guidance: During a financial restructuring

5.1. Government’s objectives

In the potentially short period of time between a supplier experiencing financial difficulty and entering a restructuring process, government will need to develop a view as to its preferred outcome. In most situations, government will have several, possibly competing, objectives, principally;

Ensuring continuity of critical services:

While the uninterrupted provision of some operational services will be paramount, other services may be interruptible for a period without a material impact.

Protecting national security interests:

Some contracts may be vital for national security, others less critical. This includes data security.

Minimising financial, operational and employee impact:

Government will wish to minimise the financial, operational and employee impact.

Value for money:

Government will need to consider the value for money of each option, taking into account both the direct costs and any wider impacts.

Fostering a vibrant and competitive market for public services:

A financially stable outsourcing market plays an important part in creating a healthy and competitive tendering environment for public sector contracts. The sale of one company’s contracts or business to a competitor will likely concentrate the market.

Inappropriate intervention from government could result in mispriced risk in future contracts;

- Maintaining public trust: Where a supplier provides politically sensitive services, its insolvency can damage public trust. Careful planning and management can limit this; and

- Compliance with legal frameworks: Government must act within procurement, insolvency, subsidy control and public law frameworks, which may limit the range of available response options.

5.2. What happens to outsourced contracts during a potential insolvency?

There are a number of possible outcomes. In the various scenarios discussed above, the contracting authority will normally have a right to terminate the contract. Both the Model Services Contract and Mid-Tier Contract provide for this termination upon meeting the criteria set out in the “Financial Distress” and “Financial Difficulties” Schedules.

Whether it chooses to do so will depend upon individual circumstances.

In a solvent restructuring and CVA (and in the absence of any termination by the contracting authority), contracts will generally continue as previously, subject to any permitted changes negotiated to their terms and conditions to support the longer-term sustainability of the contract (and therefore the organisation). Any changes will need to be permissible under the Procurement Act 2023 (see Guidance: Contract Modifications).

Where a company has entered into an insolvency process (see Section 4.2 ‘Insolvent options’) however, there is greater uncertainty with contracts at risk of termination either by the insolvency practitioner or by the contracting authority.

An Administrator who decides to trade the business as a going concern may consider a contract worthwhile if it is cash generative and profitable and, if continued, would result in a higher return to creditors. However, an administrator may choose not to honour certain contracts (typically unprofitable or onerous) and may either terminate under a contractual right or simply cease performance (leaving counterparties with an unsecured claim), normally at short notice unless improved terms can be agreed.

In a liquidation, the company is wound up. All contracts and supplies will therefore be terminated, normally at very short notice, unless arrangements to assign or novate the contracts to another supplier can be agreed (and are permitted). Alternative arrangements will be required.

Modifying a contract to change the supplier will only be permitted under the Procurement Act 2023 where an assignment or novation to another supplier is required following a corporate restructuring or similar circumstance.

It is worth noting that there have been cases where companies have continued trading during liquidation with government agreeing to meet all of the company’s liabilities as they fall due and to indemnify the insolvency practitioner against any claims. In practice, this is a very uncommon occurrence due to the complexity and expense of the process, and it will only be considered for the most critical contracts. If a department is considering this they must contact the Markets, Sourcing and Suppliers team in the Cabinet Office.

For contracting authorities, the issue is typically how swiftly they can switch suppliers at short notice - particularly where the services are critical and uninterruptible, and where continued delivery depends on central services or other dependencies.

For suppliers, their ability to bid for future contracts will be affected because the Procurement Act 2023 provides for a discretionary exclusion ground where a supplier or connected person is declared bankrupt, or is subject to certain types of insolvency or pre-insolvency proceedings in the UK or similar procedures outside of the UK. For more information on the discretionary exclusion ground of insolvency and bankruptcy, see Guidance: Exclusions.

5.3. Who are the principal stakeholders in an insolvency situation?

In a potential insolvency situation, there are a number of interested stakeholders. For information purposes the most common stakeholders and their respective positions are summarised below.

5.3.1. Directors

In the ordinary course of business, the directors have a statutory duty to act in the best interests of the company to ensure that it meets all of its obligations. In an actual or potential insolvency situation, the directors have a duty to act in the best interests of the company’s creditors.

Directors are therefore critical to a solvent restructuring and have the ability to declare insolvency but lose relevance once an administrator or liquidator has been appointed.

5.3.2. Shareholders

The shareholders own the company and have a significant stake in its performance but are not responsible for its day-to-day management. They have no enhanced rights and no ability in their shareholding capacity to place the company into a formal insolvency process.

In an insolvency shareholders rank behind all creditors in the ‘distribution waterfall’ (the order in which proceeds are distributed). It is therefore highly unlikely that they will receive any distribution once the assets of the insolvent company have been realised.

Shareholders are important in a solvent restructuring as a possible source of additional funds or where their approval is required (e.g., for a debt-to-equity swap). In an insolvency situation however, they have limited relevance save to the extent that they may represent a purchaser for the business if it is sold.

5.3.3. Insolvency Practitioners

Insolvency practitioners (IPs) are the individuals who take on the office holder roles of liquidator, administrator or CVA supervisor. They are typically qualified accountants who hold an insolvency practitioner’s licence.

On appointment, it is typical for at least two IPs to be appointed to an office holder role for each insolvent company, with joint and several liability for their actions. IPs are appointed to realise the assets of the company for the benefit of its creditors and therefore owe certain duties to those creditors as well as being officers of the court.

Note that in some cases IPs may not be prepared to take on an office holder role for an insolvent company. In addition, in certain circumstances the role may be taken on by the official receiver through the Insolvency Service. This may arise if the liquidation is compulsory, lenders do not wish to fund an administration or the returns from a liquidation are likely to be insufficient to cover their costs.

5.3.4. Advisers (Lawyers/Accountants)

Lawyers and accountants play a key role in assisting the directors of a company through the, often challenging, period of uncertainty that precedes the formal insolvency of a company. The advice provided can take the form of reviewing cash flows, providing restructuring advice, assisting in the accelerated sale of the distressed business (sometimes termed “Accelerated M&A”) including pre-pack sales, contingency planning for the company’s insolvency, through to providing advice to directors on their duties and the mechanism for placing the company into an insolvency process.

Creditors may also appoint their own accountants and lawyers to provide advice on how to protect and improve their positions prior to and following the insolvency of a company.

5.3.5. Auditors

An auditor providing an adverse opinion regarding the financial statements, or a going concern qualification, will be of significant concern to the company’s customers and creditors. This can often lead lenders to withdraw credit facilities. A company will typically delay issuing its audited accounts while it explores options to achieve a solvent restructuring and avoid the inclusion of such a statement.

5.3.6. Regulators

Regulatory bodies provide sector oversight and monitor individual companies to ensure they adhere to regulatory guidelines. Entities such as the Prudential Regulation Authority and the Care Quality Commission are able to prescribe sanctions on companies if they are not performing to the standards required, the ultimate sanction being the removal of the company’s licence to operate in a particular sector. The Charity Commission is the independent regulator for charities in England and Wales and may have a regulatory interest, depending on the reason for the insolvency.

The financial distress of a company can result in enforcement action being taken against it. Conversely, enforcement action itself can lead to the financial distress of a company if the entity is no longer able to operate in its chosen sector. Companies House in particular has the ability to strike off companies that miss statutory filing deadlines.

5.3.7. Lenders

Many companies rely heavily on credit facilities, loans and overdrafts provided by lenders for the day-to-day running of their businesses. Such facilities are predicated on the company’s ability to repay sums owed under those facilities when demanded. A company in financial distress will find it difficult to repay its debt yet is even more likely to rely on credit facilities to enable it to continue to trade.

Of all types of creditors, lenders are perhaps the most important to the ongoing trading of a distressed business. If a business is in financial distress, it will almost certainly rely on the ongoing support of its lenders to survive. If the lenders take the view that the facilities they are providing may not be recovered in full then they are likely to withdraw support. If there is no possibility of refinancing with alternative lenders, or a significant cash injection, the company will face almost certain insolvency.

Perhaps more significantly, lenders typically control the timing of a company’s insolvency – either by enforcing any security (see below) they hold and directly appointing an administrator to protect their interests, or by withdrawing support and forcing the directors’ hands.

Lenders are principally driven by the need to avoid further lending - and therefore additional exposure – and by the need to recover all, or as much as possible, of their existing debt.

5.3.8. Secured creditors

Secured creditors have greater protection in an insolvency than unsecured creditors, as they have the first claim on a company’s assets – typically through legal contracts. The most common secured creditors are the company’s lenders, who usually hold a charge over property, similar to a mortgage for individuals.

One type of secured creditor is a qualifying floating charge holder. If a creditor holds security over substantially all of a company’s assets, this may constitute a qualifying floating charge. These creditors are known as qualifying floating charge holders and have additional rights under the insolvency process.

5.3.9. Unsecured creditors

Unsecured creditors of insolvent companies are any creditors who do not hold security. They typically include suppliers and others owed money – for example, creditors under a guarantee or landlords owed rent.

In an insolvency situation, unsecured creditors rank near the bottom of the distribution waterfall, after secured creditors but before shareholders. As a result, they may receive only a few pence for every pound they are owed when the company’s assets are realised and distributed.

However, being unsecured does not mean these creditors lack influence over the insolvency process. Administrators and liquidators must seek creditor approval for certain key decisions. Unsecured creditors can also group together to form creditors’ committees to hold office holders, such as administrators and liquidators, to account and ensure that they act appropriately and in the interest of all creditors.

Where unsecured creditors include suppliers further down the supply chain, those businesses may experience financial challenges as a result of delayed payment of, or unpaid, invoices.

5.3.10. Subcontractors

Subcontractors will typically rank as unsecured creditors for sums owed for goods, works or services already supplied. They also have a strong interest in continuity of the existing contract or opportunities under any replacement contract. They are therefore a key stakeholder in a contracting authority’s insolvency response and should be engaged early.

5.3.11. Employees

The rights of employees of companies in insolvency depend on the type of insolvency procedure and what happens to the company.

Where an administrator keeps the business operating, employees may be asked to continue to work, either for a limited period or on an ongoing basis if the administrator is able to turn the business around.

If the business, or parts of the business, is sold as a going concern, employees may have rights under the Transfer of Undertakings (Protection of Employment) (TUPE) Regulations. These may include a right to transfer to the new owner and rights of consultation.

If employees are made redundant, they may be entitled to redundancy payments. Statutory redundancy payments and statutory notice payments may, in certain circumstances, be guaranteed by the National Insurance Fund. Claims for unfair dismissal may be made against the company; however, these would normally require a stay on legal proceedings to be lifted. Depending on the number of proposed redundancies, there may be a requirement for collective consultation with employee representatives for a set period of time, and for the Secretary of State to be notified.

The law in this area is complex and specific advice should be sought from the contracting authority’s legal team or externally where required.

In some situations, claims from employees may be paid before claims from other secured and unsecured creditors. For example, remuneration owed for the four month period before the start of the relevant insolvency proceedings, subject to a capped amount; in these cases the employees will be preferential creditors.

As mentioned in Section 2.2, during a Financial Distress Event employees are likely to find alternative, safer employment. Therefore, it is a crucial part of contingency planning to identify key staff and retain them during a financial restructuring. This may require discretionary payments to secure the employees in question.

5.3.12. HMRC

HMRC plays a key role in almost all insolvency situations. It is common for directors of companies in financial distress to use sums which should be payable to HMRC (for corporation tax, VAT and PAYE) to fund their business through difficulties.

Unlike other creditors of a distressed company, HMRC has little appetite to reach a commercial settlement for the sums owed to it, particularly where there appears limited chance of recovering any sums due. As such, HMRC does not hesitate to issue winding up petitions against companies with unpaid taxes where demands for repayment have not been met. Once a winding up petition has been issued by HMRC, it is unlikely to withdraw the petition unless the sums owed to it are repaid in full. The implications for the distressed company are significant. An advertised winding up petition can lead to a company’s bank accounts being frozen, making attempts to restructure the business more difficult.

When a business enters insolvency, taxes collected and held by businesses on behalf of other taxpayers (VAT, PAYE Income Tax, employee NICs, and Construction Industry Scheme deductions) will be repaid to HMRC on a preferential basis (i.e. ahead of floating charge realisations and unsecured creditors). For taxes owed by businesses themselves, such as Corporation Tax and employer NICs, HMRC receives distributions as an unsecured creditor.

5.3.13. Government

Government is actively involved in all insolvencies through the Insolvency Service. As well as acting as the official receiver (the office holder of last resort as outlined above), the Insolvency Service examines the affairs of insolvent companies reporting on any director misconduct, banning individuals from acting as directors where appropriate, and investigating and prosecuting breaches of company and insolvency legislation and other criminal offences.

5.4. Other considerations

5.4.1. Government subsidies

Government provision of financial support to companies which are insolvent is governed by the UK subsidy control regime. The Subsidy Control Act 2022 provides the framework for the regime.

Although government is able to provide funding to rescue and restructure companies in difficulty, there are strict guidelines as to what can be provided, for how long, and whether the funding in question needs to be repaid.

It should therefore normally be assumed that government subsidies will not be an option unless there are compelling reasons to the contrary. The Department for Business and Trade has published guidance on the UK subsidy control regime.

5.4.2. Pensions

Employees whose pension is an Occupational Pension Scheme will be reimbursed for some payments on a preferential basis. Subject to certain limits, these broadly comprise contributions deducted by the supplier from the employee’s pay and not yet paid to an occupational pension scheme (limited to four months before the insolvency date), plus contributions due from the employer to the scheme in the twelve months preceding the insolvency date, but not yet paid in by the supplier.

This may be relevant to contracting authorities if affected employees require clarification - advice should be sought from contracting authority’s legal teams or externally where required.

5.4.3. Use of government owned companies (GovCos)

Where a supplier becomes insolvent, contracting authorities sometimes establish a government owned company to assume ownership and delivery of the service in the short-term (this is a form of in-house delivery). This may be due to uncertainty over whether there is sufficient time or market appetite to re-procure the service externally in the time available.

Although GovCos can be quickly set up legally, contracting authorities should not underestimate the time and cost required to make them operational (for example, arranging management, bank accounts, insurance, systems, contracts with the contracting authority, etc). Where a contracting authority wishes to establish a GovCo it should liaise with the Cabinet Office Public Bodies Review Team over the categorisation of the body for public accounts purposes.

5.4.4. Budget considerations

It is likely that any contracting authority that has a contract with a company that enters financial distress will need to find additional budget. This might be needed to cover the additional resources required to fully develop/update contingency plans, to renegotiate contracts, or to do a quick procurement for an alternative provider, which may be at a higher cost.

Ultimately, if a supplier enters into an insolvency process of any kind, contract costs are likely to increase. It is never going to be business as usual for the contracting authority during an insolvency process, either operationally or financially. The general expectation is that costs associated with any government intervention, or work undertaken in support of a company in financial distress, will be borne proportionately by the contracting authorities that benefit from the work.

5.4.5. Supply chain risk

The Model Services Contract and Mid-Tier Contract include various protections against supply chain risk. These include step-in rights, the approval of key subcontractors, and assignment and novation provisions.

When planning a procurement, contracting authorities can choose to incorporate contractual provisions to mitigate distress events in the supply chain[footnote 4]. For the Model Services Contract, requires suppliers to undertake financial monitoring of key subcontractors.

5.4.6 Sensitive data

Where suppliers hold sensitive information, contracting authorities need to ensure they have access to this data - including physical access to buildings, and server rights, as well as passwords and the means to transfer the data. Data may be held in third-party systems; access may be possible via a direct contract with the third-party supplier or with the support of the Administrator. Contracting authorities should secure their own systems that might have been accessed by the organisation/their employees. In the event of supplier failure, contracting authorities need to be confident the business has fulfilled its obligations to securely delete data.

6. Additional support

6.1. Resources and contacts

Cabinet Office, Markets, Sourcing and Suppliers Team (within the Government Commercial Function):

Responsible for overseeing contract performance and managing the government’s relationship with strategic suppliers. The team has extensive experience in managing complex supplier situations and can provide practical recommendations and support for contracting authorities regarding economic and financial standing of suppliers, as well as corporate resolution planning policies, as outlined in the Sourcing Playbook.

Email contact: markets-sourcing-suppliers@cabinetoffice.gov.uk; Website: https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/government-commercial-function

UK Government Investments (UKGI)

UKGI is the government’s centre of excellence in corporate finance and corporate governance. Its Special Situations Group comprises experts drawn from the private sector with experience in financial restructuring. The team will provide support where the level of criticality is appropriate.

Email contact: SpecialSituations@ukgi.org.uk; Website: https://www.ukgi.org.uk/

HM Treasury Special Situations

The HM Treasury Special Situations Team reviews and applies principles for government intervention in response to bespoke requests for last-resort support for companies, divestment cases, and complex insolvencies, such as compulsory liquidations. It supports and coordinates departments in designing broader sector strategies and negotiating with private companies.

Email contact: special.situations@hmtreasury.gov.uk

Department for Business & Trade (DBT)

The DBT Economic Shocks Team provides support to sector teams and collaborates across Whitehall to assess, prepare for, and respond to economic shocks resulting from companies in distress.

Email contact: special.situations@businessandtrade.gov.uk

Resolution Planning Guidance

This Guidance Note explains how contracting authorities can mitigate the risk of interruption to UK public services caused by supplier insolvency by requiring the supplier to provide resolution planning information.

Resolution Planning Guidance Note; Email contact: resolution.planning@cabinetoffice.gov.uk

7. Appendix 1: Corporate Financial Distress Indicators

Table 1: Potential indicators of future financial distress

| Category | Financial | Non-financial |

|---|---|---|

| Business performance/Operating efficiency | - Adverse changes in the market/market structure - Declining revenues - Declining profit margins - Declining Return on Capital Employed - Declining Cash Conversion - Public profit warnings - Increases in creditor days/delayed payments to suppliers - Decreases in debtor days - Declining Stock Turnover - Declining funding (VCSE Sector) |

- Unexpected resignations of key management/high employee turnover - Weak management or overly controlling CEO - Delayed filing of statutory accounts/late provision of management information - Competitor gossip/market intelligence - Regulatory action - Declining share price/sudden share price falls/significant shorting of shares - Major adverse announcements (e.g., major litigation, large contract losses, etc.) |

| Liquidity/ Solvency | - High/rising net debt to EBITDA - Declining interest cover - High/rising gearing - Deteriorating liquidity/declining headroom - Lending covenant breaches - Increasing reliance on short-term or uncommitted debt - Use of non-standard financing markets - Going concern qualifications in published accounts - Requests for payments in advance - Invoice discounting/factoring - Other means of raising short-term cash - Rising pension deficits - Rising contingent liabilities - Cuts in/cancelled dividends - Over-reliance on a small number of funders (VCSE Sector) |

- Poor or deteriorating relationship with lenders - Withdrawal of coverage of a supplier’s debts by credit insurers - Falls in, or withdrawal of, credit ratings (or announcements of credit watch with negative implications) by major credit agencies - Fall in score from a credit scoring agency below the relevant warning of default level for the applicable credit scoring agencies. For example: - Company Watch H score falling below 25 - Dun and Bradstreet failure score falling below 10 |

-

Company payment practice reports are available to view via the gov.uk web service. ↩

-

For more information on audit opinions please see the Financial Reporting Council’s (FRC’s) guidance on modifications to auditors reports ↩

-

The overall EFS of strategic suppliers to government is monitored by the Cabinet Office Markets, Sourcing & Suppliers Team. ↩

-

Further details on contractual provisions to mitigate distress events can be found in the Assessing and Monitoring the Economic and Financial Standing of Bidders and Suppliers Guidance Note (PDF, 603KB) ↩