The role of Voluntary, Community, and Social Enterprise (VCSE) organisations in public procurement

Published 30 August 2022

Applies to England

Foreword by the VCSE Crown Representative

The Voluntary, Community and Social Enterprise (VCSE) sectors and the social value they create play a crucial role in our journey of transforming how the government delivers smarter, more thoughtful and effective public services that meet the needs of people across the country. Over 75 percent of VCSEs deliver public services where they are based, with strong links to that locality. Their place-based solutions can create a greater impact for those most in need, who are hard for the traditional public sector to reach. VCSEs contribute to economic growth, making the economy more innovative, resilient and productive. They can open up opportunities for people to engage with their community, foster belonging and enrich lives. Therefore the VCSE sector’s unique role in public services is vital, more now than ever.

DCMS commissioned independent analysis to assist the government in targeting efforts first, to unlock public service spend for maximum social value and second, to support the sustainability of the VCSE sectors. This research explores the role which VCSEs can play in public services. It identifies how we can reduce barriers to increase VCSE participation in public service markets. A particular focus lies in areas such as health and social care, disability, employability, where tailored and bespoke support is often beneficial to best support vulnerable groups.

The research engaged with my VCSE Advisory Panel, the Diversity Task Forces and their members including BAME-, women- and disability led organisations. The researchers consulted with nearly 30 interviewees - relevant policymakers, civil society leaders and academics. They reviewed the existing literature, and systematically analysed data from three key data sources including the Charity Commission register. The evidence and insights generated are informing our steps ahead.

There is much to do to enable the VCSE sectors work even more closely with the government as part of government supply chains, and as the VCSE Crown Representative I would like to highlight the distance we have travelled. 2022 marks the ten year anniversary of the Public Services (Social Value) Act 2012, the first legislation of its kind anywhere in the world. The Act helped transform the debate on what we can achieve through public spending. The UK has established itself as a world leader in social value. We are committed to awarding contracts not just on price, but on the long-term benefits they deliver for our society. This is why last year, our Social Value Model came into force following a public consultation.

Our Social Value Model strengthens the use of the Act and is designed to enable VCSEs and SMEs to compete alongside larger organisations. This has been the biggest change in government procurement for our VCSE sectors in recent times, covering £49bn spent by central government. It is critical for the sustainability of our VCSE sectors to use the opportunities the Social Value Model opens up. This is why I published an updated ‘Guide to working with government’ for VCSEs. I also hosted a webinar series including bespoke engagement with VCSEs which typically do not enter the public procurement market, like BAME-, Women- and Disabled-person-led organisations.

We have taken further steps to enable VCSEs’ participation, for example, the possibility of reserving below threshold procurement, increasing transparency by updating the requirements for the public sector to publish contracts on Contracts Finder, and increasing accountability by strengthening the Government Prompt Payment Policy. Indeed our public procurement reforms as a whole aim to open up public procurement to new entrants such as VCSEs and SMEs so that they can compete for and win more public contracts. In short, the government has stepped up the ambition to enable more VCSE participation in public procurement.

Whilst acknowledging efforts and progress over the last decade, I also want to challenge us to go further, and emphasise that the government cannot do this alone. This is why I welcome this research report. It shows that whilst much good work has been happening, much work remains ahead. This report offers a critical base on which to build our collective efforts going forward, harnessing £300 billion of government spend each year to truly benefit our VCSE sectors and the communities they serve.

Claire Dove CBE

Claire Dove CBE

Voluntary, Community and Social Enterprise (VCSE) Crown Representative

Executive Summary

Perspective Economics has been commissioned by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media, and Sport (DCMS) to assess the role and potential role of Voluntary, Community, and Social Enterprise (VCSE) organisations in delivering public sector contracts. The research contributes to an evidence base regarding the barriers and growth potential for VCSEs that engage in delivering public sector contracts, providing new in-depth analysis that explores four key areas:

- The current levels of participation in public procurement by VCSEs

- The growth potential, and factors influencing growth potential for VCSEs

- The barriers facing VCSEs, and how these might be addressed through policy or design initiatives

- The implications for policy and commissioning, with particular focus on political, economic, social, technological, legal, and ethical and environmental (PESTLE) factors

Current Levels of Participation by VCSEs in Public Procurement

- Data suggests that there are up to 250,000 active VCSEs in the UK. We estimate that between 9,200 and 12,500 VCSEs[footnote 1] engage in government contracting each year, i.e., up to 5% of active VCSEs

- The ability and willingness of VCSE organisations[footnote 2] to participate in procurement can be impacted by a range of factors such as size and alignment of their purpose with procurement criteria

- Local government is an important source of public contracts for the VCSE sector. Overall, 68% of contracts awarded to VCSEs come from a local government client. This is followed by central government (13%) and the NHS (11%)

- Section 4 explores the income from public contracts secured by charities using the Charity Commission Register. This is a rich dataset which provides insight into how much income registered charities are generating from procurement each year. The size of the charity is a major determinant for the level of engagement with procurement. In the most recent year (2020), two-thirds of income (£6.2bn) from government contracts was secured by charities earning in excess of £10m despite these charities only representing a group of just over 500 providers (6% of VCSEs currently engage with procurement)

- Future supply-side initiatives that seek to increase the extent of VCSE involvement in public procurement should target larger VCSEs (e.g. c. £100k annual turnover[footnote 3]) as these organisations are more likely to have the capacity to scale up public contracting activity

- Receipt of public grants by charities (approximately one in five) aligns strongly with the likelihood to participate in procurement. Grant participation may be linked with contract readiness in smaller charities and may influence future targeted capacity building exercises

- One in five (19%)[footnote 4] social enterprises report that their main source of income is from trading with the public sector, suggesting significant growth potential for social enterprises working with the public sector, either through procurement or other trading

- Regional variation is an important consideration, e.g., VCSEs in the North West and West Midlands are twice as likely as their regional counterparts to win a contract from the NHS. Proximity to contracting organisations is another factor in shaping public procurement

Growth potential

Section 5 explores VCSE participation and growth potential within a number of key sectors (health and social care, disability, and employability). Growth potential is explored by factors such as size and scale, and the current data (derived from Tussell for VCSEs[footnote 5]) suggests that:

- Health and social care (HSC) is likely to be both a core market for VCSEs (driving the majority of spend with VCSEs in public procurement) as well as an opportunity for growth. This market is likely to grow substantially given wider demographics, and HSC pressures. HSC contracts could grow at up to 9% per annum (compound annual growth rate) and by the mid-2020s, the value of HSC awards to VCSEs could exceed c. £5bn – one quarter of the c. £20bn market

- There is clear evidence of VCSEs being well engaged in the procurement of services relating to disability, employability, and vulnerable adults. The current high levels of VCSE participation in these markets may mean that growth potential (with respect to increasing share) may be limited, but policymakers should continue to track the coverage of VCSEs in these markets to ensure VCSEs can maintain market share and competitiveness

- For most of the sectors explored, commissioning primarily occurs at a local government level. Growth is therefore most likely at the local commissioning level, but should be considered alongside grant income (e.g., whereby VCSEs are currently receiving grants from local authorities, but could feasibly be positioned to secure both grants and contracts in future)

Key barriers facing the VCSE sector

Section 6 explores a wide range of barriers[footnote 6] impacting VCSE participation in public procurement. We summarise the key barriers below.

- Definition and understanding of the sector can result in reduced practical engagement and understanding of the sector

- While sunk costs are viewed as a necessary part of procurement, this investment of time should be proportional to a contract’s scale and complexity

- Contract payment timelines, receiving payment on time and managing cashflow on public contracts can be challenging for VCSEs

- Supply chain issues can lead to smaller VCSE organisations feeling overburdened or face challenges within public contract supply chains

- Awareness of opportunities and access to information regarding current and upcoming tenders was frequently cited by VCSEs as a key barrier

- Contracts marked as suitable for VCSEs varies between central government and local government authorities, which may impact likelihood, or perception of VCSE’s ability to engage

- Technological barriers are important to consider. With the digitisation of contract notices, it can often become challenging for smaller VCSEs with less technological know-how to track contract opportunities across multiple sources. Recent literature highlights a digital skills gap, with less than half of the VCSE sector rating their digital skills as “good.” Cyber security is also cited as an area in which VCSEs could be supported

- Skills and Capacity issues should be considered. This can be affected by the size and scale of organisational structures. Smaller VCSEs can be disadvantaged when compared to larger organisations with greater structural capacity and experience of bidding for contracts

- Contract design can act as a barrier to engagement for organisations with different geographic reach, human resource, or sector specialisms. VCSEs may be excluded based on the scope of the project’s tender specification (i.e., whether the requirements are specialist or general), the scale (i.e., local or across regions), and the price (i.e., are budgets realistic enough to meet the needs of the VCSE’s service users)

There are several actions that can be taken to practically reduce barriers faced during procurement. Consultees discussed the role of tender criteria and the scored use of Social Value to ensure that the benefits of the VCSE sector can be reflected within the bidding process. This should include increased involvement of the sector in the commissioning, decommissioning, and recommissioning of contracts, and the standardisation of procurement portals and tender questions where possible. Other options could include ring-fencing funding for the sector that can be awarded to smaller organisations with fewer resources. This funding could include a less resource-intensive process to encourage participation, and greater flexibility in requirements to ensure smaller VCSEs can continue to adjust their services to meet regional needs.

Implications for policy-makers and commissioners

Findings from the research suggest a series of potential implications:

-

Improving data quality: There are several steps that can be taken to improve data quality for understanding VCSE participation in public procurement. Key considerations include:

- Availability of data for different types of VCSEs: By improving the quality of data available for different types of VCSE, commissioners can be supported to engage relevant groups and to support delivery catering to the needs of specific service users

- Data available at the local level: Local government commissioning is important for the sector. Developing infrastructure to support collaboration could help stimulate procurement opportunities for specialist VCSEs at a local level

- Supply-chain data enrichment: There is limited data available regarding VCSE sub-contracting. Future research should enrich government’s understanding of where sub-contracting spending is allocated to VCSEs

-

Potential survey to assess VCSE attitudes towards procurement: Given the diversity that exists within the sector, a survey approach within future projects may be useful to explore representative views on procurement from the VCSE sector

- Addressing capacity concerns: It is important to acknowledge and mitigate the capacity limitations that exist on both the supplier and commissioning side. This could include provision of resources to develop formal VCSE procurement strategies or the identification of ‘sector champions’ within commissioning bodies to articulate the role of social value, and the potential impact of VCSEs

- Limited capacity, particularly among local commissioners, has arguably resulted in poor levels of understanding, and an inadequate capacity to facilitate meaningful or consistent engagement with the VCSE sector. This has also led to fragmented policy and practice between regions and means that contracts are rarely designed with the VCSE sector in mind. It has also been noted that co-production and co-design are limited due to capacity issues

- Need to build strategic, long-term partnerships: Engagement between commissioners and the sector is typically viewed by consultees as ‘ad hoc’. This limits the ability of the sector to work effectively in partnership, both together, and with commissioners to address long-term regional need

- Awareness of user-led value-added and engagement: Commissioner awareness of user-led engagement should be increased. These organisations can ensure that both culturally appropriate and tailored support services are available, and that the most marginalised members of a community can feel safe when being signposted to mainstream support

With respect to further understanding the growth potential of VCSEs in public procurement:

- Government should further explore VCSE intention to bid or scale using public procurement, potentially through a representative survey. This would enable an assessment of the potential volume of VCSEs currently not engaging with procurement that wish to do so

- Central and local government stakeholders should consider the areas of strategic expertise and VCSE strengths within key markets, and should explore the potential for ‘matching’ skills against contracting opportunities (at a scale which VCSEs can engage with). This could involve co-production or feedback sessions between commissioners and VCSE bidders

- Growth potential should also account for both the risk of market displacement and the wider size of each core market. There may be opportunities to grow the market for VCSEs through either growing the aggregate market, encouraging sub-contracting of VCSEs by private teams, or by encouraging commercial entities to have more social focus

- Growth potential could feasibly exist at a sub-contractor level; however, this area has limited data and has been underexplored in the past. We recommend that the use of enhanced data within central and local government commissioning at a sub-contractor level, shared where possible to further the understanding of the size of subcontracting opportunities available to VCSEs

- Growth potential for VCSEs could also be enhanced through practical interventions with respect to awareness of contracts. For example, all contracts should be marked as suitable for VCSEs by default (unless suitable reasons are given) and proportionality should be adopted, i.e., using appropriate frameworks could be used to commission smaller lots of services where specialist VCSEs may be well placed to deliver services

Section 1: Introduction

1.1 Study Background

Perspective Economics has been commissioned by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media, and Sport (DCMS or “the Department”) to assess the role, and potential role of Voluntary, Community, and Social Enterprise (VCSE) organisations in delivering public sector contracts.

DCMS is the government lead for VCSE policy and coordinates across government to ensure that VCSE organisations are fully represented in civil society policy and wider government strategies. The Department places strategic priority upon stewarding a strong, stable, and more sustainable VCSE sector, and unlocking public service spending to maximise social value.

When discussing the VCSE sector within this report, the research team refer to the wide range of organisations that exist with a social or environmental purpose. VCSE organisations can include charities, public service mutuals, social enterprises, and many other non-profits.

The Department believes that VCSE organisations can provide better, more effective public services, while also creating social value that benefits society more widely[footnote 7]. Social value is the creation of additional social outcomes ‘through the performance of a contract and includes the wider social, environmental, or economic benefits that can be delivered through government contracting.

This research builds on previous analysis of procurement practices conducted on behalf of DCMS by Tussell[footnote 8], and provides a more in-depth view of how procurement practices vary between regions, different levels of Government, and between VCSEs of different sizes, and service provision. The research makes use of both quantitative and qualitative research methods (outlined in Section 2), while also consolidating wider literature relevant to public procurement within the VCSE sector.

1.2 Research Questions

This research explores the potential of VCSE organisations in public sector contracting and the barriers they face in entering and delivering within public markets. There are a number of research questions that this report considers, which are summarised below:

Growth Potential:

These questions are focused on understanding how VCSE participation (with respect to volume or value) can be increased within public markets, and where the opportunities exist. Key questions include:

- How many VCSEs are there currently in the UK, and of these how many are currently winning Government contracts?

- Which markets exist where non-VCSE organisations currently deliver contracts, that VCSE organisations could feasibly run? What are the implications for government policy?

-

How does growth potential differ within health and social care, disability, and employability markets? How is this affected by factors such as:

- Government Level: Where is the largest growth potential?

- Contract Level: Is there potential for VCSEs to secure contracts further down the supply chain?

- Geography: Where is VCSE participation in public procurement lower than in other areas?

- Size of Organisation: What is the growth potential for VCSEs within the selected public markets depending on size?

-

Type of Organisation: To what extent is there room for new entrants within the markets of interest?

- How much does the growth potential change depending on whether a provider is a specialist in a particular type of service only, vs a provider of a wider range of services or engaged in multiple service markets?

Barriers

These questions focus on the key barriers facing VCSE organisations when bidding for or delivering government contracts, and potential mechanisms to address these. Key questions include:

- What are the barriers for VCSE organisations, and to what extent do these vary by sector, government level, contract level, geography, size, and type of organisation?

- Are any of these barriers specific or unique to one type of VCSE organisation?

- How has the Government and the VCSE sector tackled these barriers since 2007? What has worked well, or less well, and why?

PESTLE Analysis

It is also important to understand the context within which policy objectives are being delivered. Therefore, in addition, the research also includes a PESTLE analysis of the following factors for both growth potential and barriers:

- What are the key political, economic, social, technological, environmental, and legal factors influencing growth potential and barriers?

- Are there markets set to grow due to socio-economic factors like an aging population where a VCSE organisation within a market may grow their share of market income but not market size?

- How are these factors likely to affect change in the growth potential and barriers to entry in the future and how might they affect policy recommendations?

This report provides a summary of the key findings, and we also provide a full annex setting out relevant policies, literature, data, and consultation feedback.

Section 2: Methodology

This research uses a mixed methods approach to identify barriers and opportunities for VCSEs in public procurement. Table 2.1 provides an overview of the three parallel research strands undertaken as part of this research. Please note an in-depth methodology is set out in Appendix 2.

Table 2:1 Methodology overview

| Methodology | Approach |

| Literature Review | The review of the existing literature, including policy papers relevant to the sector and procurement relating to areas such as empowering civil society, simplifying procurement practice, and addressing sectoral barriers. The literature review includes close to ninety reports, c.50 reports produced by government, and c.40 academic and grey literature sources relating to civil society. |

|---|---|

| Consultee Engagement | Interviews with 29 strategically placed consultees. A purposive approach to sampling has been taken, and organisations engaged include four representatives from government, four representatives working to support public health, three representatives from research institutes and universities, nine representatives of the sector (including umbrella organisations, smaller VCSEs); and nine disabled people’s organisations (DPOs). Discussions centred on barriers experienced by VCSEs engaging in procurement, where growth opportunities exist, the identifications of current needs, examples of best practice, alongside wider considerations for the sector. Please note that the feedback provided by consultees offers a viewpoint of sector representatives, and while providing insight into the barriers faced, is qualitative in nature and does not carry statistical significance. |

| Data Collection and Analysis | Review of Charity Commission register, a combination of England and Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland Charity Registers detailing key metrics for analysis, Bureau van Dijk’s FAME-a supplementary dataset, used to identify social enterprise, charity, and community interest companies, Tussell: Provides a rich dataset detailing procurement activity within identified VCSE organisations at both the local and central government level. |

Study limitations

While this report provides an assessment of the current level of VCSE procurement, it is important to acknowledge where limitations exist.

VCSE attitude and willingness to participate in procurement: While this analysis provides an insight into current levels of procurement in the UK, future market growth is dependent on existing ambition within the sector to participate. While consultations provide some insight in this area, future projects should assess VCSE ambition to scale and participate in procurement (beyond the qualitative feedback received through this study).

Varying levels of data quality available for different VCSE types: Although this analysis has identified up to 250,000 VCSE organisations there are varied levels of data available for different types of organisations across the sector. The organisation-level analysis included in this report therefore focuses on Charity Commission organisations only (i.e., this includes analysis of size, income and location as defined within the Charity Commission register) and is detailed in Section 4. Section 5 and 6 focus on the wider VCSE sector[footnote 9].

The study brings together data on VCSE organisations from a range of sources. Data sources are set out below, alongside the strengths and limitations relating to each:

Table 2:1 Data sources used within this report

| Dataset | Description (incl. Level of Detail) | Strengths & Limitations | Use within Report |

| Charity Commission Register | Organisation-level data on over 170,000 charities in the UK, including data fields for registration date, organisation size, location and source(s) of income (e.g., voluntary income, activities generating funds, investment income, other income etc.) | Robust source of data on charitable organisations Granular data on source of income, including income from government contracts Available for charitable organisations only Similar data not available for all voluntary, community or social enterprise organisations | Section 4: Granular analysis of charity engagement with public procurement in the UK, including analysis of income from government contracts by size and location etc. |

| Tussell Procurement Data | Proprietary dataset detailing procurement activity (e.g., government buyers, sectors, scale and type of contracts etc.) among VCSE organisations at both the local and central government level. This data draws on published contract notices and awards. | Data on contracts awarded to a broader set of VCSE organisations (i.e., including Charitable Organisations and the wider VCSE sector) Provides useful insights into procurement of goods and services from VCSEs by different government buyers Requires some matching / classification to match VCSE organisations to contract awards Requires contract awards to be published on time and in the wider public domain / identified by Tussell. While the analysis of contract-level data with Tussell provides insight into the volume of contracts won directly by VCSEs, there is limited data available lower down the supply chain (e.g., subcontracting). | Section 5: assessment of the key markets within which VCSEs (including charities and social enterprises) are engaged in, using Tussell data to identify market trends, key buyers, and opportunities for growth |

| Bureau van Dijk FAME | Proprietary dataset containing data on more than 6m UK active companies and charitable organisations. | Provides an additional data source to identify where organisations are registered with Charity Commission, or Companies House or similar. Provides a marker for charitable organisations, charitable incorporated organisations, companies limited by guarantee and community interest companies – but does not have a marker for social enterprises | Used in Section 4 and 5 to validate and test population findings (e.g., estimate of up to 250,000 active VCSEs in the UK) |

Section 3: Policy Context

3.1 Introduction

This section sets out the key policies that are relevant to the VCSE sector and its role in public procurement. It also includes a brief timeline of VCSE-related policy since 2007 and highlights how HM Government’s most recent policy commitments are intended to increase the level of VCSE participation in public procurement. Please note that Appendix 3 provides a more in-depth view on policy alongside links to core documents.

3.2 Policy timeline

Key policy documents included in this review are outlined in Figure 3.1 below:

Figure 3:1 Policy timeline (2007 – 2022)

| Year | Policy |

| 2007 | The future role of the third sector in social and economic regeneration |

|---|---|

| 2010 | The Equality Act, The Compact, Building a Stronger Civil Society |

| 2011 | The Charities Act |

| 2012 | Public Services (Social Value) Act, The Charitable Incorporated Organisations (General) Regulation |

| 2014 | Article 19 (European Directive) |

| 2015 | Public Contracts Regulations Act |

| 2016 | Joint VCSE Review |

| 2018 | National Procurement Strategy for Local Government in England, VCSE Action Plan (Health and Social Care), Civil Society Strategy |

| 2020 | Transforming Public Procurement (Green Paper), Procurement Policy Note (06/20), Guide to using the Social Value Model |

| 2021 | VCSEs: A Guide to Working with Government |

| 2022 | Levelling up the United Kingdom, Response to Danny Kruger MP’s report |

Source: Perspective Economics

The policies included in Figure 3.1 are reflective of commitments to foster and sustain a collaborative relationship between the VCSE sector and government.

The Equality Act (2010), for example, sets out anti-discrimination law within the UK around key protected characteristics such as age, race, and disability. Other policies, such as the Public Services (Social Value) Act (2012) act as strategic levers and encourage commissioners to engage with the VCSE sector and to better design services to incorporate social value.

Wider policy provides clarity to the sector. The Charities Act (2011), for example, covers important rules, such as the definition of a charity, the requirement to register with the Charity Commission, and details how to prepare and submit annual accounts and reports. The Charitable Incorporated Organisations (General) Regulation (2012) also sets out what should be included in a governing document for a CIO. Other policy updates have been designed to simplify the procurement process and to increase transparency (e.g., Public Contract Regulations Act (2015)).

3.3 Recent policy commitments (2018 – 2022)

In more recent years, one of the most ambitious policy developments is the Cabinet Office’s Transforming Public Procurement Green Paper (2018). This document outlines ambitions to simplify the procurement process and current legislation as far as possible into a single, uniform regulatory framework, while also increasing transparency within procurement.

Several guides to support the sector have also been produced. Cabinet Office’s “Guide to working with Government” aims to support sector understanding and engagement with Government by setting out how VCSEs can bid for and win government contracts. It also outlines Government’s commitment to diversifying the supply chain and to place increased emphasis on social value.

This guidance highlights the steps taken by Government to encourage VCSE procurement, such as the abolition of pre-qualification questionnaires for low-value public sector contracts; increasing transparency by requiring the public sector to publish contracts on Contracts Finder; and increasing accountability by requiring the public sector supply chain to be paid within 30 days.

Further guidance on the Social Value Model also offers advice to commissioners around evaluating social value in tenders, and contract management, reporting, and case study development. The guide sets out ambitions to increase supply chain resilience, ensuring that VCSEs, SMEs, and new businesses all have the same opportunity to bid for contracts.

This guidance is part of wider ambitions to further incorporate social value. It expands on the original Social Value Act (2012), and complements Public Procurement Note 06/20, which further embeds social value within central Government procurement practices.

Levelling Up the United Kingdom also recognises the importance of voluntary and community groups in building skills and social capital, acknowledging the need for strategic coordination, suggesting that a mission-oriented approach is most effective in addressing complex, systemic problems. The document outlines the importance of shared leadership across key sectors at the community level.

Danny Kruger MP’s response to Levelling Up, “Levelling Up Our Communities: Proposals for a New Social Covenant” also includes recommendations relevant to the VCSE sector which focus on improving data quality, strengthening social value commitments, empowering communities, improving social infrastructure, and supporting the voluntary sector.

PPN 11/20 can also be leveraged to support the sector. This note sets out options that may be considered by contracting authorities when procuring contracts for goods, services and works with a value below the applicable thresholds. This gives contract authorities the ability to run competitions specifically for SME and VCSE organisations.

Section 4: Current participation in public procurement

4.1 Introduction

This section of the report explores how VCSEs are engaging with public procurement in the UK, based on analysis of Charity Commission data which provides granular detail on how charities source their income, including through government contracts.

It later explores how government buyers are engaging with the VCSE sector, through analysis of contract awards using Tussell data. A full methodology is set out in Appendix 2. Additional data tables are also set out in Appendix 4.

Please note that due to data limitations, the majority of the analysis within this chapter (Section 4) relates to organisations registered with the Charity Commission only. The research team has undertaken data cleaning (across the Charity Commission data for England, Wales, Northern Ireland and Scotland), which results in a population of 170,560 charitable organisations for analysis. These organisations are explored in this chapter across a range of measures such as size, location, and sources of income. The rationale for use of Charity Commission data is that this provides high quality granular data at an individual level regarding size, location, and income source. For example, it allows the research team to identify which charities (by size and location) have secured some income from a government contract in the past year.However, it is recognised that this is likely to under-represent social enterprise participation in public procurement. This is due to limited firm-level data available to identify and match social enterprises to procurement data. Please note that we provide recommendations regarding data availability in Section 8.

Key insights

Number of charities engaging in public procurement:

- We estimate that 9,180 charitable organisations[footnote 10] currently participate in public procurement (in 2020), generating an income of £9.2bn (5% of contract award value).

Size:

- Of the 9,180 charities that have won a contract, 80% (7,339) had an income above £100,000 per annum. This suggests that income can be considered as a significant determinant of participation with procurement

- Two-thirds (68%, £6.2bn) of income from government contracts is received by super major and major charities, despite these charities only representing a group of just over 500 providers (i.e., 6% of the charities currently engaging with procurement). Larger organisations are therefore securing most of the procurement income received by charities

Income:

- Approximately one in five charities (20%) receive income from grants, compared to one in twenty (5%) receiving income from government contracts. This illustrates a higher tendency within the sector to receive grant funding compared to contracting. This can be linked to several factors (such as restrictive tender requirements and resources to bid, explored in detail in Section 6)

- The 9,180 charities that participate in public procurement raised c. £3.8bn from grant funding in 2020. This is almost equal to grant funding raised by other charities (161,380 charities, £3.9bn in funding), despite being a significantly smaller group. This challenges the viewpoint that some VCSEs choose to opt for grants or procurement, and illustrates the importance of both as income sources, as well as suggesting that if an organisation received income from grants, there may be potential for this organisation to scale up and participate in procurement

Regional income for charitable organisations:

- Super major (income over £100m) and major (income over £10m) charities headquartered in Greater London and the South East perform particularly strongly in securing income from government contracts

- Across the regions, super major, major, and large (income over £1m) charities drive most of the income from government contracts, receiving £8.5bn in 2020 (c. 92% of contract values).

- These contracts are typically large-scale contracts, with multidisciplinary components e.g., large work packages to support communities with particular social interventions at scale. This has potential implications for smaller charities, or organisations that deliver specialist services, and highlights the important role of contract design in facilitating participation in procurement

Demand side factors

- 68% of contracts awarded to charities are issued by local government, compared to 13% of contracts through central government, and 11% by the NHS. The analysis of demand-side factors reiterates the importance of local government for engaging VCSEs in public procurement across the UK. Local authority buyers also represent 57% of relative spend in the last five years

- There is some regional variation that could be explored further. For example, suppliers headquartered in the North West and West Midlands are approximately twice as likely as their regional counterparts to win a contract from the NHS

- Further, proximity is a clear factor in shaping public procurement, with organisations headquartered in London and the South East (and devolved examples in Northern Ireland and Scotland) securing more central government contracts than the UK average

4.2 Current levels of participation in public procurement

We estimate that within the UK there are up to 250,000 active VCSEs (with at least one employee). Those identifiable within the search strategy used include:

- 170,560 charities mapped against Charity Commission annual returns[footnote 11]; and

- Approximately 120,000 other VCSEs mapped using BvD FAME. These include c.26,000 community interest companies, c. 84,000 companies limited by guarantee (of which an estimated c. 20,000 may be VCSEs)[footnote 12], and c. 8,500 mutuals. There is also a wider estimate that there are approximately 100,000 social enterprises[footnote 13],[footnote 14] active in the UK, of which many will be included in these figures

Please note that given the diversity in definition, and the limitations that exist within current data sources, this figure relating to VCSE sector size is an estimate only. Further, there will be some overlap between these two datasets, therefore we use an estimate of 250,000 VCSEs in total. Appendix 2 sets out the population and definitional work in detail.

Of identified VCSE organisations, we have been able to identify:

- Approximately 9,180 charities reported income from the delivery of government contracts in 2020 (identified through Charity Commission data). This is consistent with the Tussell estimates which suggest c.12,500 VCSEs appeared on a government contract (identified awards or spend data) between 2016 - 2020

The subsequent section focuses on the organisational characteristics of the 170,560 charities flagged by the Charity Commission data for England and Wales, and Scotland and Northern Ireland[footnote 15],[footnote 16] (unless specified). The 170,560 unique charities with an identifiable income (Charity Commission, Year End 2020) have been grouped together under six income size bands[footnote 17] as follows:

- Super Major (£100m + income)

- Major (£10m - £100m)

- Large (£1m - £10m)

- Medium (£100k - £1m)

- Small (£10k - £100k)

- Micro (<£10k)

Appendix 4 sets out the size, income, location, and service offering of these charity organisations in more detail.

4.3 Factors influencing participation in procurement

This section explores charity participation with procurement, providing an overview of key organisational factors that influence an organisation’s likelihood to participate in procurement. As above, please note that further data tables are provided in Appendix 4.

Income

For the charities that secured income from government contracts in 2020 (n = 9,180), the vast majority (7,339 providers, 80%) earn more than £100,000 per annum. This is outlined in table 4.1 below

Table 4:1 In Receipt of Contract Income for Charity Organisations

| Size Band | Count | Count Receiving Income from Government Contracts | Percentage Engaging with Government Contracts |

| Super Major (£100m +) | 116 | 57 | 49% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Major (£10m - £100m) | 1,342 | 465 | 35% |

| Large (£1m - £10m) | 6,856 | 2,266 | 33% |

| Medium (£100k - £1m) | 30,225 | 4,551 | 15% |

| Small (£10k - £100k) | 70,757 | 1,771 | 3% |

| Micro (<£10k) | 61,264 | 70 | 0% |

| Grand Total | 170,560 | 9,180 | 5% |

Source: Perspective Economics analysis of Charity Commission data

Note, the average income for charities receiving income from government contracts is c.£4.3m and the average proportion of their total income received from the delivery of public contracts is 35%.[footnote 18]

We segment these organisations into four quadrants, detailing the total number of strategic suppliers, charities showing high levels of engagement, and charities with low levels of engagement. Figure 4.1 is based on the 7,339 non-small / non-micro charities that receive an income from procurement.

- High Income, High Engagement (364 charities, 5% of current charities engaging in procurement): These are organisations with a greater-than-average income, and greater-than-average percentage of income from government contracts. These organisations are considered highly engaged within public procurement and can potentially be considered as strategic suppliers

- Low Income, High engagement (2,662, 36%): These are organisations with a lower-than-average income, but a greater-than-average percentage of income from government contracts. These organisations are more reliant upon delivery of contracts to sustain their services, and this may present an opportunity for growth, as these organisations are highly engaged but smaller, typically earning less than £5m per annum

- High Income, Low Engagement (618, 8%): These organisations generate a higher-than-average income but are considered less reliant upon the delivery of government contracts (i.e., less than average / <35% of income is generated through contracts). Each charity in this cohort should be explored on an individual basis, as very major providers may deliver significant contracts that may be a small part of their overall operations

- Low Income, Low Engagement (3,695, 50%): These organisations have both a lower-than-average income and lower-than-average percentage of income from government contracts. These organisations may typically be delivering small volumes of contracts but have provided some indication of engagement with contracts. This population may therefore have scope to be supported to grow and scale the level of government contracting, or grant and contract readiness support

Figure 4.1 visualises this relationship between charity income, and the percentage of this income that comes from government contracts.

Figure 4:1 Total income (£) and percentage of income from government contracts (charities)

Figure 4:1 Total income (£) and percentage of income from government contracts (charities)

Source: Perspective Economics analysis of Charity Commission data n = 7,339 non-small / non-micro organisations. The y-axis is income and is logarithmic.

Wider analysis of income data set out in Table 4.2 below and in Appendix 4 suggests that:

- The 9,180 providers involved in the delivery of government contracts earned approximately £9.2bn in 2020 (27% of their total income)

- Smaller organisations place more importance on income from government contracts, which makes up 66% of their total income, and larger organisations have more diversified income sources

- More than two-thirds (68%, £6.2bn) of income from government contracts is declared by super major and major charities, despite these charities only representing a group of just over 500 providers (i.e., 6% of charities currently engaging with procurement)

Table 4:2 In Receipt of Contract Income for Charity Organisations

| Size Band | Count | Total Income | Income from Govt Contracts | Average Income from Govt Contracts | Median |

| Super Major (£100m +) | 57 | £12.6bn | £2.3bn (18%) | £41m | £11m |

| Major (£10m - £100m) | 465 | £12.4bn | £3.9bn (32%) | £8.4m | £3.3m |

| Large (£1m - £10m) | 2,266 | £7bn | £2.3bn (33%) | £1m | £470k |

| Medium (£100k - £1m) | 4,551 | £1.8bn | £560m (32%) | £124k | £76k |

| Small (£10k - £100k) | 1,771 | £97m | £64m (66%) | £36k | £26k |

| Micro (<£10k) | 70 | ** | ** | ** | |

| Grand Total | 9,180 | £33.8bn | £9.2bn (27%) | £1m | £1.3m |

Source: Perspective Economics analysis of Charity Commission data (2020)

Grant Income

Grant income secured by charity organisations is made available through the Charity Commission register dataset. Exploring grants as an alternative to contracts as well as grants as a potential precursor to contracts are two important considerations for policy-makers, as this may demonstrate a) the link between contract and grant readiness and b) it may flag where some commissioners are currently using grants as an alternative to contracts.

Charities in Receipt of Income from Government Contracts and Grants:

Table 4.3 provides an outline of the c. 170,000 charities, detailing income from procurement and grants by charity size, comparing charities that have previously received income from procurement to those that have not.

Table 4:3 Income from government summary

| Marked as engaging with public procurement | Size Band | Count | Income (2020) | Income from Contracts | Income from Grants | Average Grant |

| Super Major (£100m+) | 57 | £12.6bn | £2.3bn (18%) | £1.3bn (10%) | £23m | |

| Major (£10m - £100m) | 465 | £12.4bn | £3.9bn (32%) | £1.3bn (10%) | £2.7m | |

| Large (£1m - £10m) | 2,266 | £7bn | £2.3bn (33%) | £0.9bn (12%) | £400k | |

| Medium (£100k - £1m) | 4,551 | £1.8bn | £560m (32%) | £0.3bn (19%) | £74k | |

| Small (£10k - £100k) | 1,771 | £0.1bn | £64m (66%) | £25m (26%) | £14k | |

| Micro (<£10k) | 70 | ** | ** | ** | ** | |

| Subtotal | 9,180 | £33.8bn | £9.2bn | £3.8bn | £414k | |

| No procurement activity identified | ||||||

| Super Major (£100m+) | 59 | £16.6bn | Nil | £1.5bn (9%) | £25m | |

| Major (£10m - £100m) | 877 | £21bn | Nil | £1bn (5%) | £1.1m | |

| Large (£1m - £10m) | 4,590 | £13.9bn | Nil | £0.7bn (5%) | £150k | |

| Medium (£100k - £1m) | 25,674 | £7.4bn | Nil | £0.4bn (6%) | £16k | |

| Small (£10k - £100k) | 68,986 | £2.3bn | Nil | £0.2bn (10%) | £3k | |

| Micro (<£10k) | 61,194 | £0.1bn | Nil | £0.04bn (6%) | <£1k | |

| Subtotal | 161,380 | £61.2bn | £nil | £3.9bn | £24k |

Source: Perspective Economics analysis of Charity Commission data

Of the organisations included in Table 4.3:

- 9,180 charities receive income from government contracts (£9.2bn)

- Of these, 6,953 (76%) receive income from contracts and grants (£3.8bn in value)

- The remaining 161,380 charities that did not receive income from government contracts received a similar value in grants (£3.9bn overall)

This suggests that organisations that secure income from government contracts are more likely to secure proportionally higher levels of grant funding (securing £3.8bn in grants, an average of £400k per organisation) compared to those that are not marked as engaging with public procurement (securing £3.9bn, an average of £24k per organisation).

This data suggests that some organisations in receipt of grants could be able to move towards contracting opportunities; and that there may be potential to support targeted growth of VCSEs engaging in the procurement market by upskilling or supporting capacity building activities within VCSEs that currently acquire a proportion of their income capacity to acquire grant funding.

Regional income:

Figure 4.2 sets out the income from government contracts by supplier location[footnote 19]. This provides insight into the value of contracts across NUTS regions, and the size of charities winning contracts. It highlights how strongly super major and major organisations headquartered in Greater London and the South East perform with respect to securing income from government contracts. This is likely due to larger charities that operate nationally working from these regions.

Across the regions - super major, major, and large organisations drive most of the income from government contracts. These contracts are typically large-scale, with multidisciplinary components e.g., large work packages to support communities with particular social interventions at scale. Income among larger organisations is an important consideration as this seems to drive regional variance, compared to smaller charities, who earn a much more consistent income across regions.

Figure 4:2 Income from government contracts

| Region | Super Major | Major | Large | Medium | Small | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greater London | £1,219m | £1,426m | £416m | £106m | £8m | £3,175m |

| South East | £427m | £803m | £375m | £78m | £13m | £1,697m |

| North West | £177m | £441m | £351m | £72m | £5m | £1,046m |

| South West | £103m | £304m | £265m | £60m | £10m | £742m |

| East Midlands | £290m | £172m | £86m | £38m | £6m | £593m |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | £0m | £201m | £222m | £63m | £6m | £492m |

| West Midlands | £0m | £185m | £240m | £49m | £5m | £480m |

| East of England | £65m | £145m | £162m | £51m | £8m | £432m |

| Wales | £79m | £139m | £136m | £34m | £3m | £391m |

| North East | £0m | £171m | £108m | £30m | £1m | £311m |

Source: Perspective Economics analysis of Charity Commission data (£9bn in 2020)

Demand side factors:

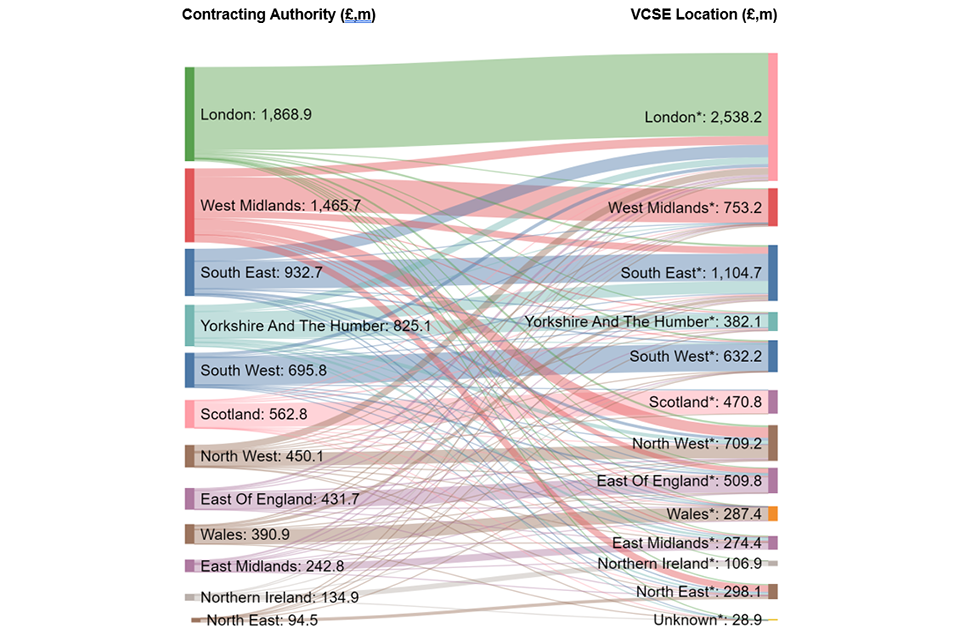

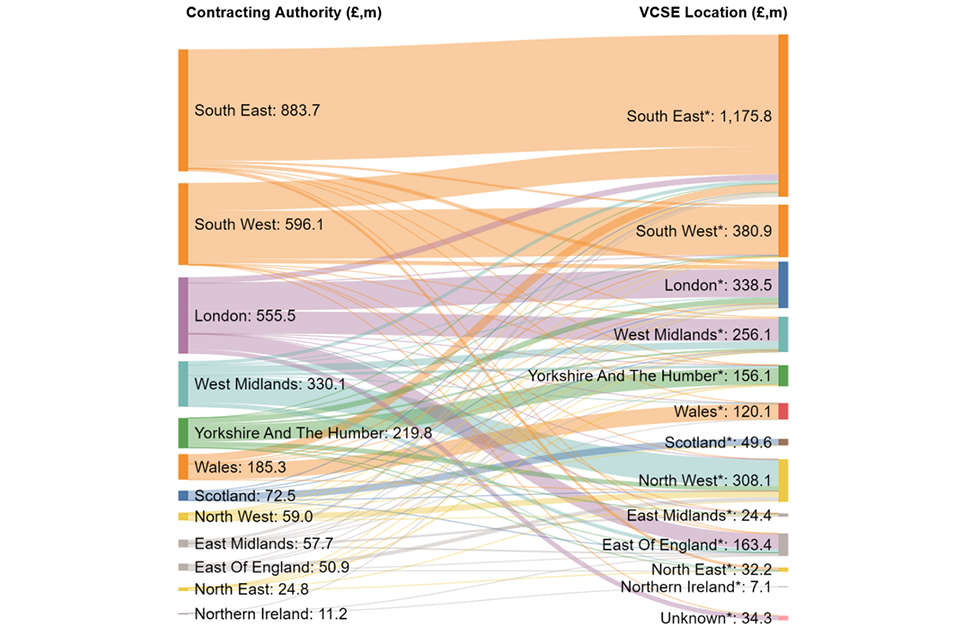

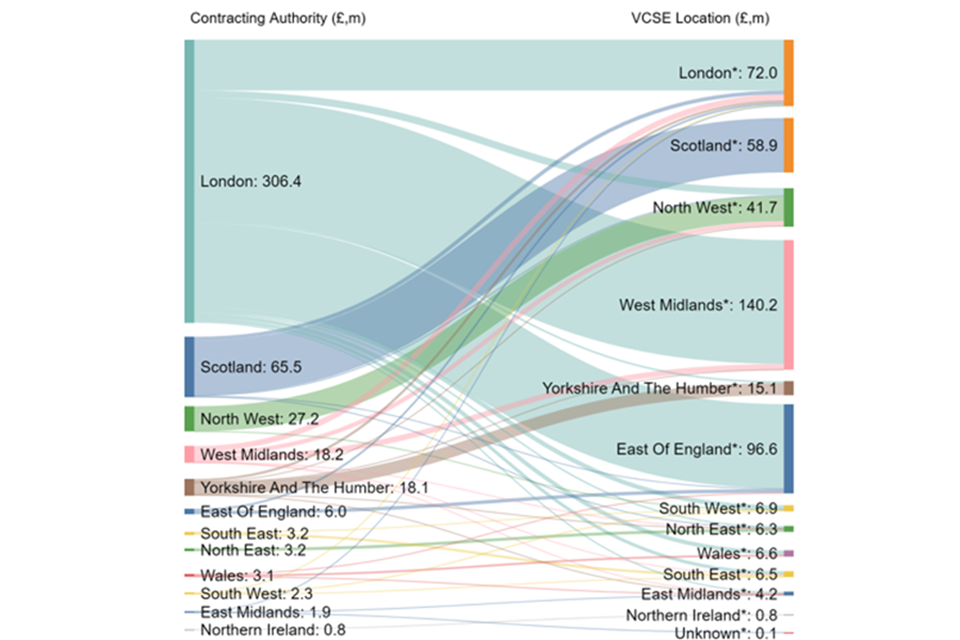

Figure 4.3 outlines contracts awarded to VCSEs by supplier region and buyer type, matching all identified VCSE organisations against contracts available via Tussell. The figure explores the buyers and supplier location identified within contracts won by VCSEs between 2016 - 2021 (where available) by region.

The analysis reiterates the importance of local government for engaging VCSEs in public procurement across the UK. It also highlights where there is regional variation. For example, VCSEs in the North West and West Midlands are approximately twice as likely as their regional counterparts to win a contract from the NHS. Additionally, a region’s proximity to central government also influences the extent to which VCSEs will engage therein.

Figure 4:3 Contracts Awarded to VCSEs by Supplier Region and Contracting Authority Type

| Region | Local Government | Central Government | NHS | Other | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| London | 60% | 21% | 11% | 7% | 3,822 |

| North West | 66% | 5% | 23% | 6% | 1,744 |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 85% | 4% | 6% | 6% | 1,388 |

| South East | 69% | 17% | 8% | 6% | 1,207 |

| West Midlands | 68% | 7% | 21% | 5% | 1,161 |

| South West | 71% | 12% | 5% | 12% | 1,133 |

| East of England | 73% | 14% | 7% | 6% | 941 |

| Scotland | 74% | 17% | 6% | 3% | 917 |

| North East | 84% | 5% | 4% | 7% | 800 |

| East Midlands | 64% | 11% | 14% | 12% | 611 |

| Wales | 61% | 11% | 16% | 11% | 449 |

| Northern Ireland | 42% | 41% | 12% | 4% | 210 |

Source: Perspective Economics (VCSEs - mapped against 14,383 contracts by region. Includes all contracts awarded to VCSEs between 2016-2020).

Section 5: Growth Potential

5.1 Introduction

To develop policy and initiatives to further VCSE participation in public procurement, there is a need to explore growth potential across buyer and contract types, and segmentation by VCSE type. Growing VCSE involvement in government contracts is not simply about VCSEs winning more contracts compared to non-VCSEs, but rather includes:

- Growing markets in which VCSEs participate (demand-side) i.e., increased participation from the VCSE sector due to increased demand for services, whereby VCSEs win a larger volume of contracts (by number or value)

- Growing the VCSE sector’s share of the market (supply-side), whereby VCSE organisations may merge or bid jointly to deliver services (reflecting a smaller number of providers, but increased market share)

- Structural changes in the delivery of public services (demand-side) e.g., where a government grant becomes a contractual provision of services, and is delivered by a VCSE

- Increased subcontracting (both supply and demand-side) of VCSE organisations in government contracts

The importance of service quality and impact should also be included when considering the growth of the VCSE sector. This section assesses overall growth potential for VCSEs currently participating (or that could feasibly participate) in public procurement, providing analysis that relates to all VCSEs identified that currently participate in public procurement using Tussell data. This includes an analysis of growth potential in eight key sectors as defined in Appendix 2. These include:

- Health and Social Care

- Disability

- Employability

- Offender Rehabilitation

- Legal and Advocacy

- Domestic Violence and Sexual Abuse

- Homelessness

- Youth Services

This research builds on the original research completed by Tussell by assessing the key factors influencing VCSE market growth potential. Factors include whether contracts are marked suitable for VCSEs, organisation size, level of government, and regional activity.

Please note that this section uses data from Tussell, and includes analysis of all VCSE contracts, where they could be identified either using identification and matching of VCSE organisations against organisational data held by Tussell, or through Tussell firm-level identifiers for non-profit, charitable, and CIC organisations.

Key Insights:

-

Health and social care is by far the largest market for VCSEs in absolute terms with £11.6bn awarded between 2016 and 2020. It is possible by the mid-2020s that the value of HSC awards to VCSEs could exceed c. £5bn per annum within the context of a c. £20bn market (based on current growth trends)

-

The overall value of contracts within the disability market has remained consistent in recent years (approximately £1.3bn - £1.5bn per annum) but the number of contracts has steadily increased (e.g., over 1,000 contract awards to all suppliers in 2020). There may be opportunities for further growth where groups can work closely with beneficiaries to help design and provide personalised care and support

-

Employability services generated £1.1bn in awards for VCSEs (25% of the sector) between 2016 and 2020 but year on year, the volume and value of contracts awarded to VCSEs has remained static. Interestingly, a significant proportion of central government contracts within the employability market go to VCSEs in the West Midlands and the East of England

-

Homelessness support, and support for victims of domestic violence and sexual abuse are smaller sectors. However more than two-thirds of contract values were awarded to VCSEs, demonstrating specialism by VCSEs in these social areas. These markets could reflect areas of best practice of VCSE participation in procurement and are markets where growth can be sustained

-

There is clear evidence of specialisms offered by VCSEs being recognised in the procurement of services relating to disability, employability, and vulnerable adults. The existing coverage of VCSEs within these supply chains may mean that growth potential (with respect to increasing share) may be limited, but policy makers should continue to track the coverage of VCSEs in these markets to ensure VCSEs are able to maintain market share and competitiveness, whilst deploying high quality specialist services

-

For many of the sectors explored, commissioning is undertaken at a local government level, which is consistent with previous findings. This suggests that growth potential is most likely to occur at the local commissioning level, but should be considered alongside grant income (e.g., whereby VCSEs are currently receiving grants from local authorities, but could feasibly position to secure both grants and contracts in future). Local authorities should also explore opportunities for co-production of requirements alongside VCSEs (and other providers)

5.2 Market Overview

This section provides a high-level overview of the eight identified markets in which VCSEs typically service through public procurement. Figure 5.1 highlights how VCSEs engage with each of these public markets by absolute and relative size (2016 - 2020).

Figure 5:1 Value of contracts awarded to VCSEs by sector:

| Sector | Value | Percentage of Value to VCSEs | - |

| Health and Social Care | £11.6bn | 24% | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disability | £2.4bn | 43% | |

| Employability | £1.1bn | 25% | |

| Homelessness Support Services | £0.5bn | 69% | |

| Domestic Violence and Sexual Abuse | £0.5bn | 66% | |

| Legal Advocacy | £0.3bn | 24% | |

| Youth Services | £0.3bn | 20% | |

| Offender Rehabilitation | £0.3bn | 6% |

Source: Tussell (2021) UK Public Procurement through VCSEs, 2016 - 2020

The following sub-sections set out the current levels of participation, estimated growth potential, and factors for policy consideration. A fuller assessment of factors such as size, location, type, and growth (to date, and potential) is set out in Appendix 4 for the three largest markets (health and social care, disability, and employability).

Health and Social Care:

Current: Health and social care is by far the largest market for VCSEs in absolute terms with £11.6bn awarded between 2016 and 2020. This represents just 24% of award value across the health and social care sector, with the remaining 76% awarded to private businesses.

Growth potential: There is an estimated CAGR (compound annual growth rate)[footnote 20] of 9% per annum for HSC contracts within the market, but a growth rate of 20% per annum for VCSE awards. It is possible therefore, by the mid-2020s, the value of HSC awards to VCSEs could exceed c. £5bn per annum within the context of a c. £20bn market (based on current growth trends). Wider literature suggests health and social care is particularly important for public service mutuals, with just under half of the mutuals included in Social Enterprise UK’s State of the Sector (2019) report working in healthcare.[footnote 21]

Factors to consider: Approximately two thirds (66%) of VCSE income from health and social care contracts comes from local government contracts, the majority of which is awarded to super major (27%), major (25%) and large (21%) VCSE providers. However, there are also over 1,500 VCSEs with an income of less than £10m engaged with this market, and there may be potential to support these organisations to scale to meet increased demand for HSC by local authorities, particularly among specialist providers who currently make up two thirds (67%) of the value HSC market.

Areas such as the West Midlands and the North West perform strongly with respect to VCSE values (compared to local non-VCSEs). There are opportunities to further stimulate the growth of local VCSEs within these regions. For example, buyers in the West Midlands procured approximately £1.5bn in health services between 2016 - 2020 with VCSEs – but VCSE suppliers in the West Midlands were only commissioned to deliver c. £750m of services in this period.

Disability

Current: Disability services are a key market for VCSEs, with £2.4bn awarded (43% of contract values). This highlights the relative strength of VCSEs in provision of such services.

Growth potential: The overall value of contracts within the disability market has remained consistent in recent years (approximately £1.3bn - £1.5bn per annum) but the number of contracts has steadily increased (e.g., over 1,000 contract awards to all suppliers in 2020). There may be opportunities for further growth where groups can work closely with beneficiaries to help design and provide personalised care and support. It is however important to note that there has been a disproportionate increase in the number of non-VCSEs winning contracts in this area which may suggest a rise in private organisations contracts.

Factors to consider: Local government is a significantly important market for VCSEs involved in disability service provision, as local government awards approximately 41% of its contracts to VCSEs. The majority of contract value within local government is awarded to super major (32%), major (17%) and large (40%) VCSE providers.

There is also some evidence of small and micro VCSEs securing contracts relating to disability services, particularly with local government. Whilst these contracts are a small proportion of the market size (£143m awarded to micro VCSEs between 2016-2020), they may offer insight into the relationships between very small but specialist VCSEs that can use procurement opportunities to scale and grow (57% of the total market value was awarded to specialist providers). This might include the provision of particularly specialist services, or the use of VCSEs within social policy pilot schemes.

Regionally, in the South East, the value awarded to VCSEs (£1.2bn) outstrips non-VCSEs (driven by contract awards to Communities First Wessex and Dimensions UK). Further, 90% of contract values relating to disability services in Wales were won by VCSEs.

Approximately 58% of contracting spend is awarded to VCSE suppliers within the same region. This reiterates the importance of local commissioning and buy-in when seeking to grow the VCSE sector through procurement.

Employability

Current: Employability services generated £1.1bn in awards for VCSEs (25% of the sector) between 2016 and 2020.

Growth potential: Year on year, the volume and value of contracts awarded to VCSEs has remained static (approximately £0.3bn per annum across c. 200 contracts). Data suggests that central government and local government award a similar value of contracts in this area, potentially suggesting a greater need to explore the role of central government (e.g., DfE, DWP) compared to other sectors.

Factors to consider: The majority of employability contracts awarded to VCSEs are to larger providers. Super major, major, and large VCSEs secured approximately three-fifths (60%) of income relating to employability contracts. However, the 40% of income to medium, small, and micro VCSEs highlights higher participation by smaller VCSEs in this market compared to others, and highlights scope to grow smaller VCSEs in this market through government contracts.

It is important to note that there is a relatively small proportion of supplier income awarded to VCSEs compared to non-VCSEs across regions. Given the size of the market, this may indicate some growth potential if VCSEs were to increase their relative market share. In terms of regions, the West Midlands appear to have relatively strong VCSE participation within employability markets.

Legal Advice and Advocacy

Current: Legal advice and advocacy provision aims to ensure fairness and representation within the legal process. This market is smaller than other sectors identified (approximately £1.4bn market in awards over four years, 24% of which was awarded to VCSEs, i.e., £0.3bn).

Growth Potential: This market has remained broadly consistent in recent years (c. £300m - £400m per annum, with an average of 100 VCSEs being awarded contracts each year). Most contracts are awarded at a local government level, typically for advocacy provision. Legal advice more generally appears to be awarded more at a central government level to private firms, and therefore a focus on advocacy provision among VCSEs may be worth undertaking.

We do not expect this market to have significant growth potential for VCSEs based on historic performance; however, it would be worth engaging with existing providers to further identify their growth ambitions or scalability across different local government levels. This could also include understanding levels of subcontracting or VCSE engagement with private law practices.

Support for victims of domestic violence or sexual abuse

Current: This area of government contracting requires highly specialist and sensitive provision to fully support victims of violence and abuse. Of the £700m worth of contracts between 2016-2020, 66% (£455m) was awarded to VCSEs. This demonstrates the consistent strength of VCSE organisations in securing contracts for support services. These contracts are typically issued by local government.

Growth Potential: Given the strong proportional involvement of VCSEs currently within this market area, growth potential is likely to be determined by the absolute growth of support services across local government more generally, rather than targeted support or encouraging participation from VCSEs.

Spending within this sector has been broadly consistent over the last four years (c. £150m - £200m per annum), as has VCSE participation. Therefore, this market, and proportion of VCSEs therein, may not be expected to grow substantially in the years ahead.

However, there may be opportunities to work directly with VCSEs engaging with these contracts, as well as commissioners, to understand current delivery models and what could be undertaken to further enable providers in the delivery of high-quality support.

Homelessness support services

Current: Homelessness support services is another sector in which VCSE suppliers are highly prominent, winning contracts worth £500m between 2016-2020 (69% of the total value). However, there are only a relatively small number of VCSEs engaging in this market (c. 100), and contracts are typically awarded at a local government level.

Growth Potential: The historic data for contract awards suggests limited capacity for growth potential (given relatively low market size - c. £150m - £200m awarded per annum) and high VCSE participation currently as a proportion. However, this is a clear market for exploring VCSE expertise, engagement, and delivery models, particularly given the need for sensitive and impactful service provision.

Offender rehabilitation

Current: The public sector awarded contracts worth £6bn for offender rehabilitation between 2016 and 2020. However, despite the social focus of these contracts, VCSEs only won £300m over this period (c. 5% of the total). These contracts are typically awarded via central government, rather than at the local level. There is also a small number of providers (both private and VCSE) suggesting a relatively concentrated market. Current contracts delivered by VCSEs typically focus on areas such as drug and alcohol support, substance misuse, and victim referral.

Growth Potential: The low incidence of contract values being awarded to VCSEs does suggest there may be opportunities for VCSEs to either directly secure a greater volume of contracts or increase sub-contracting as part of these contracts. However, this may be a challenging market for VCSEs to scale within, given the role of many strategic suppliers (private) delivering support for offender rehabilitation.

Youth Services

Current: Tussell identifies c. £1.6bn of ‘youth services’ awards between 2016 - 2020. However, £1.1bn relates to ad hoc National Citizen Service contracts awarded in 2019, and therefore this market typically awards a low annual value (c. £100m per annum). Of this, VCSEs typically win approximately 25% of the value, and 40% of the awards. This is a key market for a small number of specialist providers in youth work e.g., Groundwork, London Youth, and Catch 22.

Growth Potential: Given the nature of this market, many VCSEs that provide youth services may have greater focus on grants and co-delivery with local government than market size for contracting.

5.3 ‘Suitable for VCSE’ Markers

Within government contracts, there is often a marker (provided by the contracting authority) for whether the contract is suitable for VCSEs (or SMEs) to bid and deliver. Figure 5.2 demonstrates the proportion of contracts (across the eight contract sectors) that are considered suitable for VCSEs, and Figure 5.3 shows the proportion of contracts awarded to VCSEs which were marked as being suitable for VCSEs.

Figure 5:2 Percentage of contracts marked as suitable for VCSEs

| Buyer Type | Suitable for VCSEs | Not Suitable for VCSEs | No Marker |

|---|---|---|---|

| Central Government | 25% | 59% | 15% |

| NHS | 15% | 25% | 61% |

| Local Government | 12% | 13% | 75% |

| Other | 22% | 48% | 30% |

Source: Perspective Economics analysis of Tussell data since 2016 (Central, n = 2,966 contracts, NHS = 1,987, Local = 21,689, Other = 1,650)

Figure 5:3 Percentage marked as suitable for VCSEs won by VCSEs

| Buyer Type | VCSEs | Non-VCSEs |

|---|---|---|

| Central Government | 20% | 80% |

| NHS | 25% | 75% |

| Local Government | 44% | 56% |

| Other | 27% | 73% |

Source: Perspective Economics Analysis of Tussell since 2016 (Central, n = 770 contracts, NHS = 305, Local = 2,659, Other = 381)

Within central government, 85% of contracts have a marker, and 59% of all central government contracts are marked as not suitable for VCSEs. Note that at this level of government VCSEs win just 20% of all contracts marked as suitable. This suggests that at this level, the higher number of contracts marked as unsuitable creates a perception that central government is unwilling, or less likely to engage with VCSEs, resulting in less engagement from the sector

Conversely, a lower percentage (25%) of local government contracts have a marker, and just 13% are marked as not suitable for VCSEs. VCSEs however win 44% of contracts marked as suitable at this level.

To increase the perception that different levels of government are open to engaging with VCSEs future contracts should, where possible, be marked as suitable for VCSEs by default, unless a valid reason is otherwise given.

5.4 Other types of commissioning models with potential for VCSEs

As part of this research, it is important to consider the different funding mechanisms that can support VCSE engagement in delivering government contracts, beyond direct and traditional procurement channels.

The social outcomes approach is one such example, known more commonly as social outcomes contracts (SOCs), or social impact, or impact bonds in the UK. The impact bond is an outcomes-focused funding mechanism used to address social issues. Data made available through the INDIGO community project[footnote 22] suggests that there are 89 bonds in the UK, just over two-thirds of which are already complete.

UK projects stored on the INDIGO database have run from 2010 and have been used to support employment and training (27%), homelessness (25%), child and family welfare (24%), health (15%), education (8%), and criminal justice (2%). Across all SOCs included in this dataset, c.53% are involved at a local government level, 29% central, 13% at the regional level, and 5% “other”.

In a European context, several policies exist to increase the number of SOCs, such as InvestEU and the Council of Europe Development Bank’s HERO pilot. Currently, however there are still significant gaps in publicly available information and evidence of impact[footnote 23]. By encouraging buyers to develop tenders using the SOC approach, VCSEs may be better able to demonstrate their value and engage with procurement.

More recently in the UK, the Low Value Purchase System has been developed as a new route for public sector buyers to market their below threshold common goods and services. This system can be used to support Government’s SME policy, contributing to the Social Value outcome of increasing supply chain resilience and capacity, while acting as a lever to support smaller VCSE organisations to participate in procurement[footnote 24]. However, policy-makers should be mindful that low value contracts may be suitable for some VCSEs, but should not be a proxy for VCSE entry into public procurement if they are not able to deliver higher-value contracts.

The role of grants in supporting the sector is also an important consideration, with several consultees raising concerns around the diversity of scale and capacity that exists in the VCSE sector, and how this impacts willingness and ability to participate in procurement (this is outlined in more detail in Section 6 of the report). It is important that grants are still viewed as a feasible mechanism to support growth. This is due to several reasons, such as the flexibility they offer VCSEs as they address complex or changing regional needs.

Consultees have also noted how it is important to consider international best practice:

“In the US, federal government categorises businesses from historically underserved communities. For these businesses congress sets a target. The Small Business Administration focuses on this and builds capacity across government” – Academic organisation

This consultee notes the potential to adopt best practice from other countries, highlighting the importance of targets and ring-fenced funding as a mechanism to grow the sector.

The European Commission (2019)[footnote 25] provides a summary of good practice in relation to the inclusion of social considerations in public procurement procedures. The European Commission’s document outlines good practice and several examples of capacity and relationship building exercises. Example activities include:

- the development of capacity within government, with responsibilities to inform public bodies of the existence of the social clause in government contracts and promote their use in procurement, to help contracting authorities select the most appropriate social clause, to analyse prospective contracts, to educate private and VCSE sector on the purpose of the social clause and provide various training opportunities, and to monitor tenders containing social clauses and support contracting authorities so that clauses can be used effectively;

- the development of flexible clauses within contracts which gives firms the ability to provide placements for trainees directly into their own workforce, or to subcontract specific workers from social enterprises which aim to integrate people with disabilities, or people from disadvantaged backgrounds. To support this, regional government developed a network of public buyers, companies, social enterprises, and training organisations, within which social clause facilitators were appointed, serving as a point of contact to support administration and collaboration; and

- The development of a national network of social clause facilitators which provides buyers access to an online resource centre containing a list of local facilitators, good practice examples, legal advice, publications, etc., and on-demand access to technical expertise to support local facilitators facing specific difficulties.

Section 6: Barriers to VCSE Procurement

6.1 Introduction

This section provides an overview of key barriers faced by the VCSE sector. Barriers outlined in the section below have been identified through both the systematic review of existing literature, as well as strategic engagement with 29 consultees. Note that findings are grouped under four themes, namely:

- Supply-side barriers: a review of the current capacity within the VCSE sector to bid for contracts, capacity to deliver, supply chain barriers, and the sector’s digital skills gap

- Demand-side barriers: a review of the commissioner’s current understanding of the VCSE sector, the impact of contract design and commissioner approach, the data available to support procurement, and the current approach to sector partnerships

- The experience of disabled persons’ organisations: an overview of the unique perspective of organisations run by and working on behalf of disabled communities

- Government action to reduce barriers: an overview of the current activity being undertaken to support the sector and to reduce barriers

Key insights:

- Capacity is a key issue on both commissioner and supplier-side. This relates to VCSE capacity to bid and delivery contracts, and capacity to form meaningful relationships between the sector and local commissioners

- Governance is a key barrier faced by smaller VCSEs. This often means they are excluded from contracts due to eligibility criteria

- VCSE willingness to bid is a key consideration. Contracts can be seen as restrictive, or unconducive to the VCSE’s unique mission