Public Design in the UK Government: A review of the Landscape and its Future Development (HTML)

Updated 21 August 2025

Authors:

Lucy Kimbell, Professor of Contemporary Design Practices, Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts London and Director, Fieldstudio Design Ltd

Catherine Durose, Professor of Public Policy and Co-Director of the Heseltine Institute for Public Policy, Practice and Place at the University of Liverpool

Rainer Kattel, Deputy Director and Professor of Innovation and Governance, Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose, University College London

Liz Richardson, Professor of Public Administration in the Department of Politics, University of Manchester

Executive summary

All governments face challenges of a changing social context, system complexities and barriers to delivery requiring innovation. There is growing evidence that public design has untapped potential to help address such challenges. The term ‘design’ encompasses a range of activities and skills, including: a human-centred focus; prototyping; and co-creation. All of these activities are now widely used in industry, the public sector and governments. These activities and skills inform a range of government activities, from the creation of digital interfaces to the design of government services, to the development and testing of policy proposals, to the implementation of interventions. However, the varied range of methods, skills, personnel and teams involved in design and differences in their use across the policy cycle make the term confusing. There is a need to distinguish design from other approaches, when it adds value and to specify the outcomes it leads to. The evidence suggests that ‘public’ design has greater potential than is being used at present, situated in a wider family of positive policy approaches that have in common a belief in the capacity of collective action, coupled with multiple forms of knowledge, to address challenges facing governments.

Approach/method

The report reviews and synthesises the existing evidence and activities across the UK government associated with ‘design’. This report has been written by an interdisciplinary team of academics, and is aimed at public servants in central, devolved and local government interested in the potential of design. The authors synthesised materials commissioned and collated by the Civil Service as part of the Public Design Evidence Review (PDER). These were: three Literature Reviews of academic work and ‘grey literature’ (Literature Review Paper 1 - Public Design,[footnote 1] Literature Review Paper 2 - Public Value,[footnote 2] Literature Review Paper 3 - Public Design and Public Value);[footnote 3] a set of 13 case studies of design being used by central and local government (Case Study Bank);[footnote 4] and analysis of interviews with 15 international and UK thought leaders expert in public design (Interviews with International Thought Leaders in Public Design).[footnote 5] In addition, the authors reviewed an independent report funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council produced by the Design Council[footnote 6] summarising two roundtables with 32 public sector design leaders and a survey of 1018 public sector employees. Producing this report involved several months of dialogue across the Civil Service, public services, local government, and organisations such as the Design Council.

Design in the UK Government

Over the past 20 years design approaches and skills have been embedded in the UK Government including in the Government Digital Service, policy teams in departments and local government, within a growing international ecosystem. There are now a range of design specialisms across government including communication design, content design, interaction design, organisation design, policy design, service design, strategic design and urban design. In some cases, these specialisms have a clear relationship to existing roles, professions, teams, and processes in government such as the Central Digital and Data Office; in others, they do not.

Defining design

Noting the lack of clarity about terminology, a way of thinking about public design is set out with three inter-related components. The first component is a list of practices generally seen as associated with design (see Table 1).

Table 1. Practices of public design

| Practice | Detail | Example tools or methods |

|---|---|---|

| Understanding people’s experiences of and relations to people and things in communities, systems and places | Combining a focus on embodied lived experience of a target group within wider social, organisational and technological systems and infrastructures, and mediating between these | User journey or systems mapping based on interview or fieldwork data |

| Conceiving of and generating ideas | Coming up with, exploring, and refining ideas individually or collectively | Workshops with citizens to generate ideas rooted in their lived experience |

| Visualising, materialising and giving more concrete form to ideas | Producing outputs that embody, explore and tangibly communicate insights and ideas or result in changes in visual, material and digital formats | Illustrations, maps and models |

| Integrating and synthesising perspectives, ideas and information | Combining varied sources of information to articulate, reframe and clarify problem definitions, options and solutions, taking different forms during a design process | Problem statements |

| Enabling and facilitating co-creation and citizen involvement | Prompting and supporting the inclusion and synthesis of varied positions, perspectives and sources of information from citizens to achieve co-creation and integration of lived experience in learning and design | Co-design workshops to explore problems and generate ideas |

| Enabling and facilitating multi-disciplinary and cross-organisational collaboration | Prompting and supporting the inclusion and synthesis of varied expertise, perspectives and sources of information in learning and design | Intensive ‘sprint’ workshops with experts, specialists and citizens to develop responses to a challenge |

| Practically exploring, iterating and experimenting | Creating and enabling engagement and iterative practical experimentation with potential options to test ideas and further reveal different understandings of an issue | Prototyping and testing a mock-up service |

The second component is a working definition of public design:

- Public design is an iterative process of generating, legitimising, and achieving policy intent whilst de-risking operational delivery. It involves a range of practical, creative and collaborative approaches grounded in citizens’ day-to-day experiences of - and relations to - people, objects, organisations, communities and places.

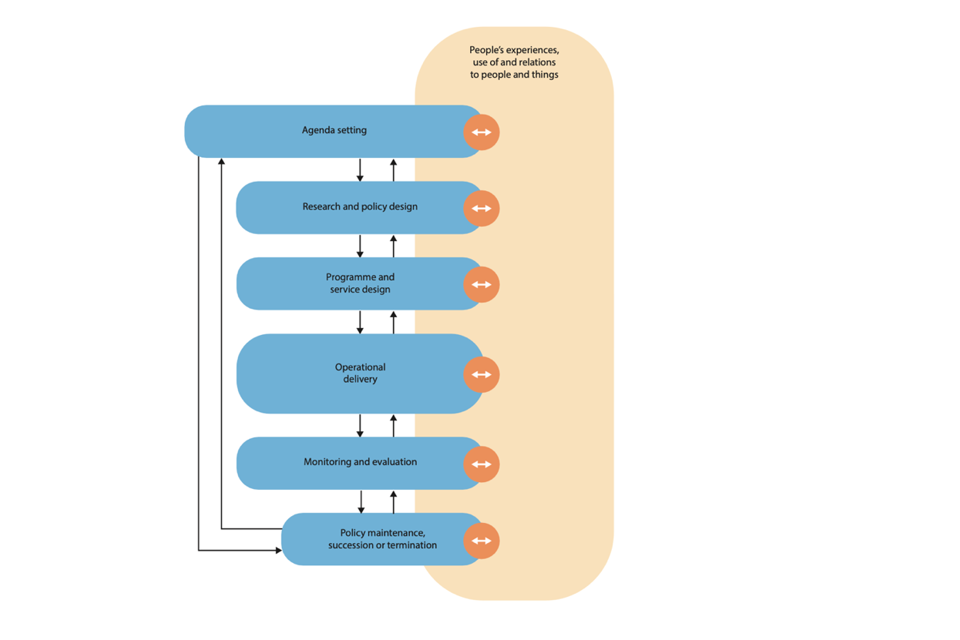

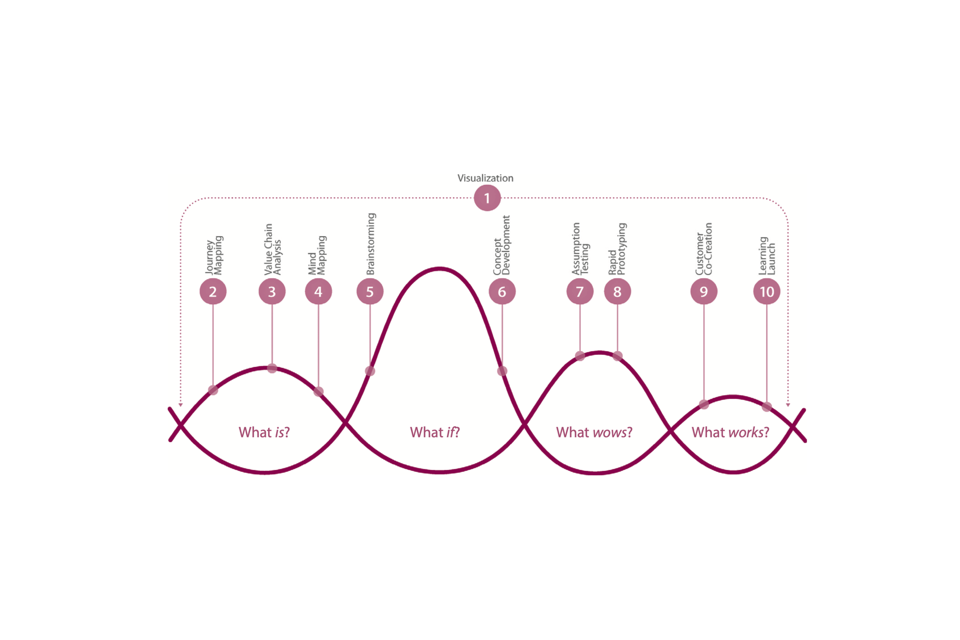

Figure 1. Iterative policy cycle oriented to people’s experiences of systems

The third component is a framework that shows what public design adds to the policy cycle (see Figure 1), with three contributions. The first is grounding the policy cycle in people’s day-to-day experiences of and relations to people, objects, and organisations within wider systems and infrastructures. The second is integrating and synthesising perspectives, evidence and expertise across and beyond government through iterative cycles of learning in context. The third is enabling practical, system-wide learning through feedback loops across the policy cycle.

What public design achieves in the UK government

Using the evidence base available, the report offers illustrative examples of an important range of outcomes and impacts from using public design practices. Public design practices achieve five significant ‘outcomes’ or intermediate benefits for government. These outcomes are:

- Collaboration, enabling people to work together to integrate, synthesise and facilitate perspectives and expertise into a purposeful iterative process involving citizens, across departmental silos and beyond government.

- Insight into citizens’ experiences of and relations to ‘the system’, polices, services, organisations and infrastructures.

- Inspiration by engaging diverse voices and expertise in co-creation.

- De-risking of operational delivery by surfacing assumptions and revealing the ‘fit’ between proposed solutions and existing processes and infrastructures.

- Increased legitimacy, by exploring, co-creating and testing ideas with stakeholders.

Through their combination, these outcomes lead to substantial impacts for government, enabling it to meet the challenges of a changing social context, system complexities, and barriers to delivery (such as working in silos), in the form of:

- Innovative solutions to policy challenges: using insights into people’s experiences and systems thinking, combined with inspiration activated through co-design and collaboration. This results in new ways of doing things, de-risked through iterative development in context, that have legitimacy with stakeholders and that work better for people, and which can be adapted, scaled and applied elsewhere.

- Increased effectiveness: enabling government to identify and avoid interventions that will cause unintended consequences or simply ‘shift the problem’ to another part of the system, by instead addressing the root problem.

- Increased efficiency: generating opportunities and activating new collaborations to deliver interventions, in ways that save resources and reduce waste.

- A reduced gap between government and citizens: increasing trust, legitimacy and engagement by citizens in terms of both government’s ability to bring about positive social change, and the way in which government goes about doing it.

Realising the potential of public design

While these outcomes and impacts are positive, further research is needed to detail and assess the contributions of design practices to innovation across the policy cycle, and to evaluate the current extent and maturity of public design in the UK. There are also important questions about how to address barriers that inhibit the potential of design to be realised in government. Along with frameworks proposed in this report, these questions provide a starting point for further research, practice development and capability building, organised into these themes:

- Purpose and distinctiveness

- Extent, maturity and scope

- Leadership and advocacy

- Institutionalisation and professionalisation

- Learning, evaluation and development.

Practices associated with design have potential beyond addressing today’s public service delivery issues. Public design can help prepare and shape government to be creative, engaged and responsive in the face of the mounting challenges of the 21st century. This review will help underpin the further development of public design and steps towards realising its potential.

1 Introduction

All governments face challenges of a changing social context, system complexities, and barriers to delivery, such as silos and cumbersome processes, requiring innovation. Those challenges are key drivers for changes in how government approaches its business. There is growing evidence that public design has untapped potential to help address the challenges facing governments. The term ‘design’ encompasses a range of activities and skills, including: a human-centred focus; prototyping; and co-creation. All of these activities are now widely used in industry, the public sector and governments. These activities and skills inform a range of government activities, from the creation of digital interfaces to the design of government services to the development and testing of policy proposals to the implementation of interventions. The varied range of methods, skills, personnel, and teams involved in design and differences in their use across the policy cycle make the term confusing.

In this context, the purpose of this report is to progress thinking and stimulate productive conversations among senior public servants about the range of activities taking place across government associated with ‘design’ resulting in steps towards its potential being realised.

The primary audience of this report is public servants in central, devolved and local government involved in policymaking and service delivery and interested in the potential of design. The focus of the report is UK central and local government but with reference made to activities involving devolved government, design consultancies, universities and civil society organisations, and situated within a broader international landscape.

The authors bring an interdisciplinary approach combining their knowledge of studies of design, innovation, policy and public administration (see report section ‘Authors’ for more details). The authors reviewed and analysed materials (see Appendix 1) selected, commissioned and collated by the Civil Service as part of the Public Design Evidence Review (PDER). This work involved teams and individuals from across and beyond government. These materials include:

- A literature review in three parts that we co-authored, which synthesises the published academic and ‘grey’ literature about the use of design in the public sector, policy and government, comprising: one on design[footnote 7], one on public value[footnote 8] and one on design and public value.[footnote 9]

- A set of 13 case studies,[footnote 10] 12 relating to central government initiatives and one relating to local government, providing examples of how policies and services have used public design.

- Thematic analysis of interviews conducted by the Human-Centred Design Science team in the Department for Work and Pensions with 15 international and UK thought leaders who are expert in public design.[footnote 11] They include founders and leaders of public policy labs and public design consultancies, authors, social entrepreneurs, architects, and other vocal champions of design in public contexts.

- An independent report by the Design Council[footnote 12] funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council summarising discussions from two roundtables it organised with 32 public sector design leaders and a YouGov survey of 1018 public sector employees.

The objectives of this report are to:

- Synthesise findings from selected evidence and summarise these clearly and accessibly.

- Build on this evidence to provide commentary on the state and value of public design.

- Enable readers to understand and navigate the different ways that terms are used in different settings.

While the report draws widely on published sources and is informed by numerous discussions and workshops with participants from across and beyond central and local government since 2023, it is not exhaustive. Further, it does not seek to evaluate the current extent and maturity of public design in the UK, in central or local government or public services. However, concepts and frameworks proposed here may be useful as a starting point for further research, practice development and capability building.

At a moment when challenges facing government are numerous, and there is a need for new thinking and innovation, understanding the potential of public design is timely. The report demonstrates an important range of positive outcomes and impacts from using practices associated with public design. Policies and services are re-designed to better meet the needs of the people using them, resources are used more effectively, including money and people’s time, and implementation is more successful because opportunities are co-designed and buy-in is established through co-creation and exploring problems and solutions collectively. These findings suggest that design expertise – associated with public policy and government – has greater potential than is being used at present.

The report outlines a set of questions about how this potential can be realised, drawn from the evidence. This includes identifying the institutional barriers and enabling conditions that hamper or support this potential to be mobilised. Addressing such barriers and creating those conditions could benefit from leadership and advocacy, a robust evidence base and approaches that support collective learning (for example, communities of practice).

The result of exploiting this potential is innovative solutions, increased effectiveness, increased efficiencies and reduced gaps between government and citizens. Yet the potential of design to meet the significant challenges facing the UK goes further. Practices and skills associated with design – and specifically ‘public design’ as we focus upon here – have potential beyond today’s public service delivery issues. The literature suggests design’s broader potential to enable circular economies, regeneration and democratic deliberation. It can help prepare and shape government to be creative, engaged and responsive in the face of the mounting challenges of the 21st century.

2 Problems facing governments and why change is needed

What are the unaddressed challenges for governments, to which design might offer a contribution? In answering this question, we do not wish to repeat criticisms sometimes levelled by academics (and other external commentators) at governments, not just in the UK, but elsewhere. Instead, our starting point is to offer constructive solutions for more effective policy and delivery. Our sense of urgency is underpinned by an analysis of the acute and chronic challenges facing governments.

What we are not doing

A classical sport is to offer critiques of how governments approach the job of governing. Favoured tactics include raising the stakes rhetorically, for example through claims of disaster, crisis, and fiasco.[footnote 13] Adjectives and prefixes have been introduced to underscore such claims and grab attention in a crowded marketplace of ideas. So, there are now not mere crises, but permacrises, and not simply fragmentation but hyper-fragmentation, and so on. Those charged with the task of delivering government could be forgiven for trying to ignore such hyperbolic propositions and get on with the job in hand. It would be understandable if some in government even felt somewhat aggrieved at accusations levelled by people who lack first-hand experience.

Positive public policy (PoPP) as a growing movement

In contrast, the authors of this report are aligned with a growing move internationally towards a constructive orientation in studies of public administration and public policy. Leading scholars in the UK, the Netherlands, Australia and New Zealand, and elsewhere, have called for positive public policy (PoPP)[footnote 14] and positive public administration (PiPA),[footnote 15] where scientists focus more on feasible solutions for more effective government than on perceived failures of governments. Reform proposals under the positive banner include advocating for a “balanced, relational, and systemic approach to nurturing strategic capacity in government”.[footnote 16] Similarly, in economics there are parallel approaches that focus not only on market failures as justification for government to act reactively, but also on mission-orientated innovation approaches,[footnote 17] where the public sector proactively shapes markets for desirable outcomes (e.g. sustainable energy systems). In this approach to public policy, markets are understood to produce outcomes that are co-created by various societal actors. The ideas of public design outlined in this report are part of this wider move towards an evidence base for positive approaches as effective tools for government.

It is in this spirit that we offer a brief analysis of the acute and chronic challenges facing governments in general, and how these are driving the case for fundamentally different approaches to designing and delivering services and policies, and ultimately achieving outcomes. Our conclusion is that there is a need for major change in policymaking, service design and delivery by the UK Government.

Societal context

Government is operating within and shapes a wider societal context where there are ongoing challenges of social polarisation and widening inequalities. These challenges suggest the need for sophisticated and segmented understandings of different groups of citizens, service users and communities (of interest, of identity, of place). There are well-acknowledged challenges of ongoing fiscal constraints and possible uncertainties, against a backdrop of low productivity. However, out of this, there can be tensions between the need for targeted investment where ideas are proven to be efficient and effective, but investment is needed to discover which are the most effective ideas. Persistent (and in some areas declining) low levels of trust in some public institutions suggest the need for greater connection with citizens. Connection here might refer to direct engagement as well as more effective messaging, but also raises many dilemmas, including striking the right balance between transparency and expectations. Different administrations have identified priority areas where, despite several reform waves in governance and public administration, achieving the intended policy goals and effectively implementing policies has been an elusive target.

System complexities

There is growing recognition of interconnected dynamic change and high levels of uncertainty cutting across society, government, business and the economy.[footnote 18] Such complexities include the rapid emergence and spread of new technologies such as artificial intelligence; climate change and ecological breakdown; ageing populations; and anti-microbial resistance. Public attitudes, preferences, and behaviours are also part of this complexity; policymakers’ ability to anticipate and test how different groups of people will respond under different changing conditions demands new approaches. To address such complexities, there are new understandings of systems resulting in, for example, frameworks that offer distinctions between simple, complicated, complex and chaotic systems.[footnote 19] To varying extents public administrations have been experimenting with using systems-based approaches but there is potential to further adapt practices and processes of policymaking to respond to non-linear, emergent situations that cross levels of governance and sectors, that are hard to predict, ambiguous and turbulent.

Barriers to delivery

In the UK, there are ongoing calls and initiatives for reform of central government and how it delivers on its policies and strategies.[footnote 20] Many government departments have expressed a strong desire for much more extensive collaboration across departments and agencies, and even more so with external stakeholders and citizens. A recent reflection by an ex-civil servant drew the sobering conclusion that: “Whitehall’s remoteness from the public and frontline results in policymaking which is fundamentally inadequate to address the challenges we face”.[footnote 21] Frustration at siloed ways of working is a key source of proposals for structural reforms[footnote 22] and calls for whole-of-government approaches.[footnote 23] Policy churn – where new or amended policies are introduced in quick succession, sometimes concurrent with existing policies – has been identified as a cause of frustration for those on the front-line of delivery.[footnote 24] Clunky and cumbersome processes are frequently identified as obstacles to better outcomes. The challenges of unmet collaboration needs, silos, and inefficient processes, suggest a need for greater capacity for whole systems approaches.

Innovative approaches to how government approaches these challenges

What the overview of challenges suggests is a set of drivers for fundamental shifts in how governments go about their business. What might such a transformative shift look like in practice? Various approaches[footnote 25] have gained some traction as ways to address the challenges of delivery, silos, learning and innovation. These include efforts to secure more coherent and integrated policy, such as the ‘strategic state’,[footnote 26] systems-thinking,[footnote 27] mission-driven[footnote 28] and place-based approaches,[footnote 29] along with evidence-informed government,[footnote 30] better research-policy engagement,[footnote 31] public participation,[footnote 32] participatory public policy[footnote 33] and behavioural public policy.[footnote 34] Design is part of this rich landscape of policy innovation. What connects these approaches is “(i) an appreciation of the complexity and inter-connected nature of policy contexts, (ii) a belief in the capacity of collective action to address shared challenges, and (iii) a commitment to the collection, synthesis and application of different forms of knowledge”.[footnote 35] To different extents, accompanied by ongoing research and debate, such approaches have been tested resulting in varied evidence of efficacy including good practice, frameworks, case studies, and policy learning. They provide a fresh portfolio of ways of designing and delivering high-performing public policy.[footnote 36]

Furthering the potential for design – clarifying definitions

Approaches, methods, tools and expertise associated with design widely used in industry are already being used to address these challenges for governments, as the Public Design Evidence Review shows. However, like many other potentially valuable approaches, design has struggled to build traction, momentum and credibility outside of some institutional forms such as digital services and ‘policy lab’ teams. In part, this is because people outside of specialist design fields find it hard to pin down exactly what is being talked about and the extent of institutional support for its practices and skills is varied. For example, on the one hand co-design is seen as a useful but limited method for participatory democracy, whereas for others democracy, public policy and governance can be entirely re-worked through design.[footnote 37]

To summarise, governments face the challenges of operating in a changing social context, with significant system complexities, and barriers to delivery such as working in silos and cumbersome processes. Public design as a set of practices, underpinned by the right enabling conditions, may provide a way to overcome these challenges and enable innovation.

However, beyond basic understandings, and organisational implications of utilising design, there are many unresolved debates: How is service design different to policy design? What are the implications of understanding citizens as ‘users’ of designed services? Do only designers do designing? There is a lack of clarity that inhibits understanding, collaboration and effective use of resources.

Key to achieving clarity is to have a clearer definition of design in relation to public policy and its delivery and implementation. We acknowledge some risks in definitions.[footnote 38] For example, too prescriptive a definition can also have the downside of ossifying concepts and practices, unless this is carefully mitigated against. Design teams and expertise have grown in government despite the lack of a clear and universal definition. Practice-led routes to understanding or engagement are compatible ways of approaching policy for designers coming from a practice-led field.[footnote 39] A broad idea can help mobilise activity because it relates to values people hold dear, or to a vision people already have. One recent academic work[footnote 40] has shown how people find it helpful to use relatively loosely-defined terms to give a name to what they do, as they work collaboratively with others. If a clearly defined idea is applied in cynical ways, and not quality controlled, then it can become the latest buzzword. One scholar, Andrea Cornwall,[footnote 41] refers to these as ‘fuzzwords’, tainted by over- and mis-use. However, a strong business case for design approaches relies on a solid understanding of what design is, and how it can interact with policy for better outcomes. Therefore, we turn in the next section to definitions. Here, we offer new thinking by integrating across research and practice in design and the political sciences to propose new definitions and frameworks of public design.

3 Defining public design

There are many forms of designing carried out in, for, and by government. Design plays an important role in how citizens experience public services, public policies, and also public spaces, both physical and virtual within wider systems and infrastructures. Graphics specialists design posters displayed on hoardings on public streets that communicate government’s messages to citizens. Urban planners produce specifications that shape the built environment experienced by residents. Service designers help develop detailed blueprints for how public services should be delivered to ‘users’ or ‘customers’. Digital designers develop ‘touchpoints’ through which citizens interact with government’s digital platforms.

Alongside these activities by people who see their work as ‘design’ – and whose job titles include that word – there are many others in central and local government, alongside key partners, service users and communities, involved in (co-)designing. For example, policymakers design policies – not always thinking of this work as a form of design, although there is a long-standing academic literature exploring just that with growing connections to research in creative design.[footnote 42]

So, is there something distinctive cutting across all these forms of design in, for and by government – something we may call public design? We argue that there is and offer a definition of it.

Defining (public) design is surprisingly hard. Some definitions focus on the orientation of design towards change, innovation or transformation. Others emphasise characteristics or qualities, or activities, claiming that these are distinctive. Others focus on the objects produced by designers, such as services or products. Some focus on professionals who think of their work as ‘capital-D’ design, whereas other definitions seem more open to anyone designing anything – a workshop, a strategy, an organisation. Rather than take a theoretical approach, we focus here on learning from practice: how is design practised in the public sector and what does this tell us about the nature of public design? To work towards a definition of public design that will help government mobilise its potential, we combine three interconnected components, set out in this section:

- a list of practices associated with public design;

- a working definition of public design; and

- a framework showing how public design re-orients the policy cycle to people’s experiences of and relations to wider contexts, infrastructures and systems.

First, we identify a set of practices associated with design in public settings, shown in Table 1 below. We developed this list by combining insights from our Literature Reviews,[footnote 43],[footnote 44],[footnote 45] along with Design Thought Leader report,[footnote 46] the Case Study Bank[footnote 47] and the Design Council’s report.[footnote 48]

By practices we mean usual ways of working, with associated skills, methods and tools that make sense to people and are routinised in organisational environments. Our synthesis suggests these practices are generally recognised across academia and industry as closely associated with (professional or specialist) design; some are also used by non-specialists, associated with ‘design thinking’. Many such practices are already being used in public services and government, and those who work with them, sometimes associated with a particular team or government profession, sometimes associated with individuals. While some of these practices are not solely the domain of designers, combining this set of practices marks out a distinctive approach to working towards change or innovation in public policy settings.

Table 1. Practices of public design

| Practice | Detail | Example tools or methods |

|---|---|---|

| Understanding people’s experiences of and relations to people and things in communities, systems and places | Combining a focus on embodied lived experience of a target group within wider social, organisational and technological systems and infrastructures, and mediating between these | User journey or systems mapping based on interview or fieldwork data |

| Conceiving of and generating ideas | Coming up with, exploring and refining ideas individually or collectively | Workshops with citizens to generate ideas rooted in their lived experience |

| Visualising, materialising and giving more concrete form to ideas | Producing outputs that embody, explore and tangibly communicate insights and ideas or result in changes in visual, material and digital formats | Illustrations, maps and models |

| Integrating and synthesising perspectives, ideas and information | Combining varied sources of information to articulate, reframe and clarify problem definitions, options and solutions, taking different forms during a design process | Problem statements |

| Enabling and facilitating co-creation and citizen involvement | Prompting and supporting the inclusion and synthesis of varied positions, perspectives and sources of information from citizens to achieve co-creation and integration of lived experience in learning and design | Co-design workshops to explore problems and generate ideas |

| Enabling and facilitating multi-disciplinary and cross-organisational collaboration | Prompting and supporting the inclusion and synthesis of varied expertise, perspectives and sources of information in learning and design | Intensive ‘sprint’ workshops with experts, specialists and citizens to develop responses to a challenge |

| Practically exploring, iterating and experimenting | Creating and enabling engagement and iterative practical experimentation with potential options to test ideas and further reveal different understandings of an issue | Prototyping and testing a mock-up service |

Second, we propose a working[footnote 49] definition of public design addressing the question: what value does design practice bring? A ‘value proposition’ foregrounds the impacts that design practices are understood to have on public policy issues, public administrations, stakeholders and citizens. Our version builds on other definitions (see Appendix 2 and Literature Review Paper 1[footnote 50] for more detail) but is adapted for the specificities of government:

Public design is an iterative process of generating, legitimising, and achieving policy intent whilst de-risking operational delivery. It involves a range of practical, creative and collaborative approaches grounded in citizens’ day-to-day experiences of – and relations to – people, objects, organisations, communities and places.

This definition is in two parts. It first emphasises a process that results in outcomes: generating ideas for, legitimising (gaining buy-in and support for) and achieving policy intent through iterating, implementation and de-risking delivery. It also highlights practical, creative and collaborative practices, such as those listed in Table 1, which advance this policy process and result in proposals, plans and specifications and ultimately lead to the production and delivery of material and digital objects and the systems they are part of. It includes a focus, found across design disciplines, on being attentive to people’s experiences of and relations to policy systems and services as they interact with people, objects and organisations in their day-to-day lives, communities, ecologies and places.

Simply put, public design diversifies sources of information, knowledge, creativity, and learning across the policy cycle. For example, public design is not simply conceiving of policy intent but also is associated with its iterative operational delivery – which may lead to a policy changing. To carry out public design involves practical, creative and collaborative practices. However, we are not specifying methods or tools to be used. The teams carrying out policy development and operational delivery are best placed to determine which methods or tools are appropriate to use in a given context.

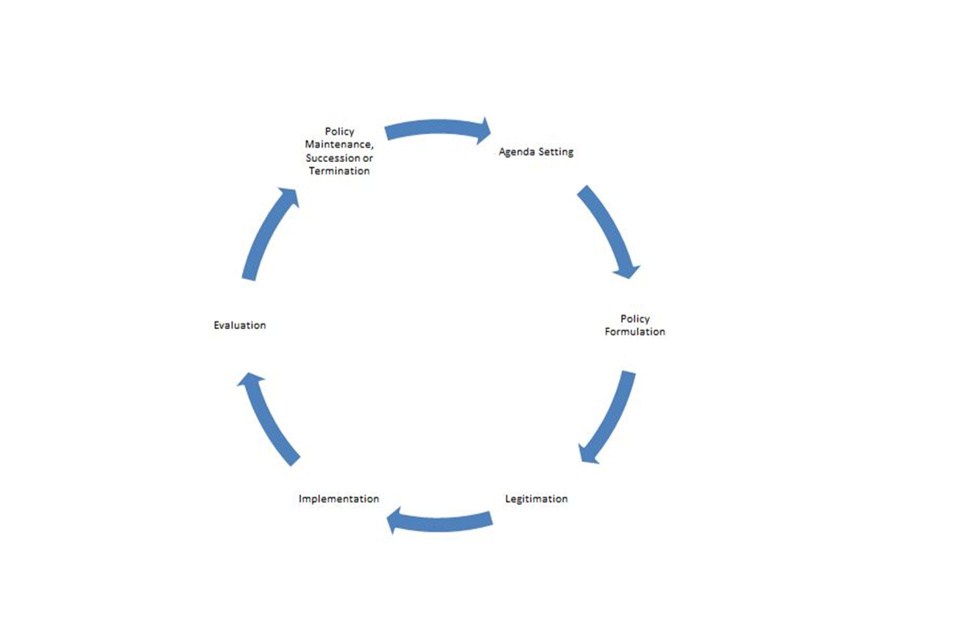

Our definition of public design is complemented by a third component. This is a framework suggesting what the policy cycle[footnote 51] might look like if public design approaches were built into it. The policy cycle is usually understood to be an abstraction that simplifies reality and which co-exists alongside other ways of understanding how policy is made.[footnote 52] The policy cycle is seen as having several distinct stages or phases – which have many overlaps in reality. While recognising that this is an ongoing area of debate, with further change likely to adapt to new approaches such as mission-oriented innovation in government, we draw on the well-established academic literature to summarise these phases as follows:

- Agenda setting: societal processes of identifying and defining those problems that require government attention

- Research and policy design: further problem definition, envisioning possibilities, specifying objectives, determining cost, identifying approaches and policy instruments, generating options and anticipating and estimating outcomes and impacts

- Programme and service design: detailed specification of how a policy should work in relation to people’s experiences, uses and relations to objects, in context

- Operational delivery: establishing or employing an organisation to take responsibility for implementation, ensuring that the organisation has the resources (e.g. staffing, money, legal authority) to do so, and ensuring that policy decisions are carried out as planned

- Monitoring and evaluation: assessing the extent to which the policy was implemented correctly and if it was effective in achieving the policy intent

- Policy maintenance, succession or termination: determining if a policy should be continued, improved upon or replaced.

Figure 1 below shows a revised version of the standard policy cycle. This is a hypothetical visualisation intended to be a tool for thinking, simplifying reality to enable further discussion. On the left-hand side of the diagram, the blue bands represent the main phases of policymaking, such as agenda setting and evaluation, familiar from other similar visualisations.

Our framework then situates these stages of the policy cycle within people’s day-to-day experiences and uses of objects and relations to the policies it produces in context. Our contribution is the addition, on the right-hand side, of an orange box which emphasises ‘experiences’, ‘use’ and ‘relations’ and highlights connections between phases of the policy cycle and the world outside government that people experience. Our framework shows how public design re-orients the policy cycle[footnote 53] to the world outside government.

Figure 1. Iterative policy cycle oriented to people’s experiences of systems

We see three significant contributions that public design makes across the policy cycle, supported by the evidence in this review. They are:

- Grounding the policy cycle in people’s day-to-day experiences of and relations to wider systems

- Integrating and synthesising perspectives, evidence and expertise across and beyond government

- Enabling practical, system-wide learning.

The first contribution of public design is to ground the stages of the policy cycle in people’s experiences and use of, and relations with, objects associated with public policy. This includes the associated administrations, services, systems, and infrastructures these objects are part of. This is possible because public designers pay acute attention to how policies and systems are experienced and the worlds of the people and objects citizens interact with in context. On the one hand, this may look very mundane and tactical. Public designers attend to the forms that people fill in, the queues they stand in when there are no chairs available, the doors they can’t open easily, the leaflets they can’t quite make sense of, the text reminders they receive. Such interactions with ordinary objects are often how people experience and relate to public policy, and its organisations, systems, digital infrastructures, and services. But on the other hand, each of these ordinary day-to-day experiences is part of a wider set of systems that, together, constitute public policy.

Public design has the potential to improve these experiences, and the systems they are part of, and in doing so, overcome some of the key challenges facing policymakers as they develop and deliver policy intent.

Our framework includes two-way arrows showing connections between all stages of the policy cycle and the world of experience and use, in context. In contrast, conventional policy cycle diagrams exclude systematic encounters with the ‘real world’ or ‘context’ other than for specific stages such as user research to inform service design, monitoring or evaluation. In so doing, other models of the policy cycle neglect significant sources of insight, inspiration, learning and legitimacy.

What does this look like in practice? As an example, user researchers, policymakers and designers trained to focus on ‘user needs’ and ‘systems thinking’ routinely research how, when and why a citizen or ‘service user’ experiences policy, the wider systems people’s experiences are related to, and, crucially, mobilise this analysis in the work of policymaking.

The second contribution that public design makes across the policy cycle is to integrate and synthesise perspectives, evidence, and expertise across and beyond government enabling and facilitating practical co-creation and collaboration. At the intersection of the blue circles (stages of the policy cycle) and the orange box (people’s experiences of systems), public design practices connect and mobilise understanding of experiences in ways that help to make policy, strategy and operations more tangible and more targeted. These are shown in Figure 1 as small circles with arrows at the end of each phase.

Here, public design is a ‘glue’[footnote 54] or ‘connective tissue’ that makes the link between people’s experiences and policy outcomes visible and legible for both citizens, policymakers, operations professionals, civil society organisations and other stakeholders. In practice, this might look like co-design events or multi-disciplinary ‘policy sprint’ workshops with diverse participants from across ‘the system’ with varied expertise including lived experience. This might include use of visual outputs based on ‘user’ or social research, such as system maps, personas, user journey maps or ethnographic films.

The third contribution public design makes to the policy cycle is practical, system-wide learning. Our framework includes two-way feedback loops between all stages of the policy development cycle in Figure 1. These emphasise how a crucial aspect of policy design is to iteratively adopt new insights or learning as a policy is developed and rolled out. Here, practices associated with public design provide tangible, rapid and often low-cost ways of actualising those feedback loops. Conceiving of policy cycle as a process for system-wide learning, rather than a single loop for delivery ‘downstream’ of what has been designed ‘upstream’, provides a way to future-proof policy interventions.

What this looks like in practice is very early testing of problem definitions, priorities, and options and surfacing of assumptions with people in their communities and places and with delivery and operations experts. For example, public designers routinely help people envision and create mock-ups of options showing what a future service encounter or building might be like, to share and discuss with operational partners and with people to whom the intervention is targeted. Such early-stage exploratory prototyping[footnote 55] enables early, rapid and diverse assessment of proposed interventions, that ‘fit’ with existing ways of doing things and (potentially) the need to transform systems and processes – whether associated with proposed policies, strategies, services or digital outputs.

Any such definition or framework is necessarily incomplete and is open to further discussion and iteration. Drawing on the authors’ expertise in policy studies and design, it is inclusive of specialist designers alongside policymakers, who may not (at present) consider what they do as designing policies. Such frameworks raise questions about which types of expertise in government are involved in the different phases of the policy cycle. The materials in the Public Design Evidence Review suggest that a range of skills and approaches are required for public design, which can be structured into public organisations in different ways, which are not always aligned with government professions.

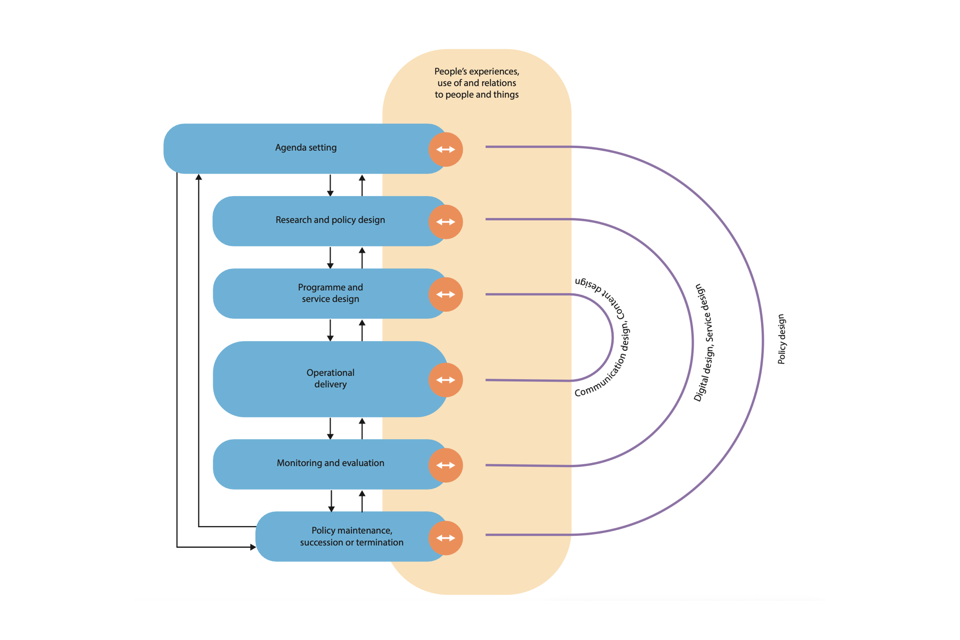

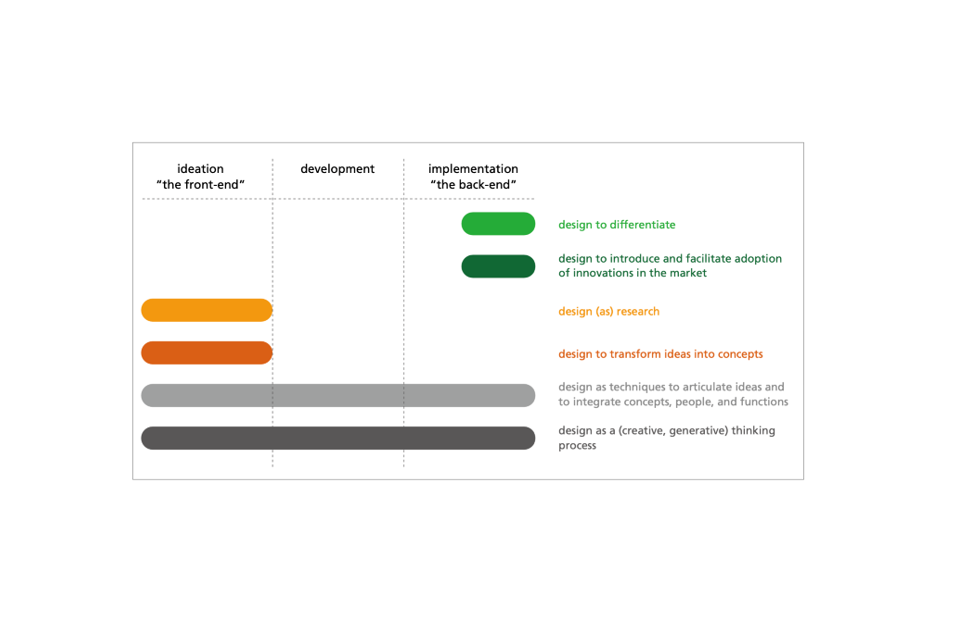

To respond to this, Figure 2 (below) illustrates how current types of expertise might map on to the policy design cycle in Figure 1 (shown for convenience to the right-hand side). It suggests that the scope of ‘policy design’ (rarely currently a formal job role or team in the UK government) is mapped across the whole cycle, whereas the expertise of service and digital designers, and communication and content designers, is more closely aligned with specific phases. This diagram should be understood as illustrative and intended to spark debate, rather than definitive.

Figure 2. Policy cycle oriented to people’s experience in context, showing alignment with specific design expertise

To summarise, the list of practices, the working definition, and the framework together offer important and necessary specificity about public design. Together, this set helps clarify what public design has to offer in a context in which there are other methodologies or approaches being used to address government’s challenges. Approaches such as participatory public policy or mission-oriented government share many resonances with public design, with their focus on learning, practice, systems thinking and co-creation. For example, Mariana Mazzucato[footnote 56] proposes that a new approach to policy design is needed, in order to deliver mission-oriented government, now part of how government is working. To achieve this, she argues, government should build capabilities around participation, design, digital and experimentation. The Public Design Evidence Review provides frameworks and evidence revealing existing capabilities in government and discussion about what is required to realise this potential.

Our definitions offer a starting point to clarify what creative, practical and collaborative approaches associated with iterative public design contribute to policy innovation, including to achieving government missions. In the next sections we look at the development of design in the UK Government and public services, and then turn to examining more closely examples from recent practice.

4 A brief overview of design in the UK government

This section offers a summary of significant moments in the development of design in the UK government and an associated ecology of organisations including the Design Council, think tanks, research funders and independent design networks. It shows growth and institutionalisation of design expertise oriented towards public policy over the past two decades. This overview also makes reference to the wider international context in which other organisations, including governments, have developed design capabilities or teams, including the Danish Government, the European Commission, the US Federal Government, and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). It then summarises some of the types (or disciplines) of design currently operating in parts of the UK government.

4.1 Major developments

There is growing evidence of the establishment and development of teams, expertise and processes associated with design in public administrations around the world over the past decade. A Design Council report[footnote 57] (synthesised as part of the evidence for this report) found that a significant majority of respondents (88 percent) to its 2022 survey of people working in the civil service, local government and public sector organisations such as the NHS and the police use design, with almost a third using it at a strategic level (Design Council, 2025, p.10). The literature review provides more detail on the academic and practitioner studies that illustrate and analyse these developments.[footnote 58]

Several institutional innovations are emerging across governments inspired by design approaches. First, the emergence of government digital units or agencies over a decade ago is largely based on ‘user-centred’ or ‘human-centred’ design approaches adapted from industry[footnote 59] such as the UK’s Government Digital Service (GDS)[footnote 60]. Second, during the same period many central governments and cities created ‘policy labs’ or other kinds of specialist team. For example, Policy Lab established in the UK Cabinet Office in 2014 is cited by at least one international government as an inspiration for its own institutional innovations.[footnote 61] Third, increasingly popular challenge-driven approaches, such as challenge prizes, hackathons or ‘jams’ tend to utilise design in ideation, iteration and experimentation phases of policy development. These developments show that design is perceived – at least by some – to offer a potentially valuable complement to policymakers’ existing repertoire of approaches to policymaking and operational delivery.

To summarise this history, Table 2 offers a timeline of significant examples over 20 years of UK public design from 2004 to now, while not being exhaustive and acknowledging that there are longer histories of design in relation to government and public policy. For example, the development of a distinctive form of design oriented to public policy was preceded by other activities, such as work by the Sorrell Foundation in collaboration with Demos experimenting with new approaches to learning,[footnote 62] alongside earlier work by design agencies and university-based design researchers. Our timeline focuses on central and local government, and the devolved administrations of the UK, alongside work by the Design Council and others, while also including references to related initiatives internationally. Intertwined with these developments are new consultancy offerings, teams, degree courses and training.

Table 2. Timeline of the development of public design in the UK Government

| Year | Design activities in central, devolved or local government and public services in the UK | Related activities in the UK and internationally |

|---|---|---|

| 2004 | The Design Council sets up RED Unit[footnote 63] to focus on transformation design | |

| 2005 | Government commissions a review of design in business by Sir George Cox[footnote 64] | British Standards Institute publishes standard on inclusive design[footnote 65] Hilary Cottam of the Design Council RED Unit wins Design Museum’s Designer of the Year[footnote 66] |

| 2006 | Demos publishes report on public service design[footnote 67] Arts and Humanities Research Council establishes Designing for the 21st Century design research programme[footnote 68] |

|

| 2007 | Kent County Council sets up Social Innovation Lab Kent[footnote 69] | Denmark sets up cross-government innovation lab MindLab[footnote 70] |

| 2009 | NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement publishes report on project using design to re-design healthcare in the NHS[footnote 71] | |

| 2010 | Digital champion Martha Lane Fox reviews digital services in government[footnote 72] | |

| 2011 | New team designs and delivers cross-government online service[footnote 73] which becomes Government Digital Service[footnote 74] Scottish Government organises #designforgov events[footnote 75] |

|

| 2012 | Government Digital Service publishes the Government Digital Strategy and launch of GOV.UK[footnote 76] Government Digital Service publishes Government Design Principles[footnote 77] |

|

| 2013 | Publication of Experience Based Co-Design toolkit for the NHS[footnote 78] Government Digital Service publishes ‘digital transformation exemplar services’ policy paper to showcase the effective new services being developed across government[footnote 79] GOV.UK website designed by Government Digital Service wins Design Museum’s Design of the Year[footnote 80] Civil Service sets up design in government blog focussing on digital design[footnote 81] |

Design Commission publishes Restarting Britain II: Design and Public Services[footnote 82] First global GovJam independently-organised international events[footnote 83] |

| 2014 | Policy Lab formed in Cabinet Office[footnote 84] Local authorities and public services work with the Design Council through its Design in the Public Sector programme[footnote 85] Northern Ireland Public Sector Innovation Lab set up[footnote 86] |

US Federal Government Office for Personnel Management Innovation Lab begins human-centred design project[footnote 87] First Service Design in Government conference[footnote 88] |

| 2015 | The Department for Work and Pensions’ Human-Centred Design Science team (originally known as the Behavioural Science team) is established[footnote 89] | Design Commission publishes report on Designing Democracy[footnote 90] OECD sets up Observatory for Public Sector Innovation[footnote 91] |

| 2016 | Government Digital Service publishes guidance and tools for digital service design[footnote 92] | |

| 2017 | Local authorities explore service design through the Local Government Association/Design Council’s Design in the Public Sector programme[footnote 93] Civil Service publishes Digital, Data and Technology Profession details including design roles[footnote 94] Cross-government community established including a focus on design – One Team Government[footnote 95] |

Nesta publishes Designing for Public Services guide[footnote 96] UNDP publishes guide to using design thinking to develop solutions to the sustainable development goals[footnote 97] EU Policy Lab in Joint Research Centre begins projects in ‘design for policy’[footnote 98] |

| 2018 | Nesta sets up States of Change programme for public innovators[footnote 99] | |

| 2019 | Scottish Government publishes Scottish Approach to Service Design[footnote 100] | |

| 2021 | Establishment of Policy Design Community and blog set up by Policy Profession Support Unit[footnote 101] | |

| 2022 | Government Office for Science publishes guidance on systems thinking for civil servants[footnote 102] | Arts and Humanities Research Council and Design Museum launch Future Observatory programme for design research[footnote 103] |

| 2023 | Initiation of cross-government Public Design Evidence Review by Policy Design Community[footnote 104] |

4.2 Forms of design in government

Design in industry is historically understood as closely tied to the objects or forms which are its outputs, existing within wider systems and infrastructures. A student choosing to study design at a UK university is likely to have to pick a specialism tied to a particular tradition and form, for example, graphic communication, architecture, textiles or products. These specialisms are associated with manufacturing and industrialisation and are very well-established. Alongside them, new types of design developed in the late 20th century in relation to increasing digitalisation, consumerisation and datafication of organisations and society. Democratic pressures to involve people in decision-making and for transparency also shaped design.

The report by the Design Council[footnote 105] reviewed for this commentary, which synthesised perspectives from design leaders working across public sector organisations, sees a blurring of distinctions between different specialisms in design, stating,

‘The values and practices of design identified in the workshop had remarkable consistency across diverse design types/disciplines. Interestingly, outside of central government, place and the physical design of urban spaces and infrastructure appears to play an integral role in policy and service design and delivery’ (Design Council, 2025, p.19)

This blurring is evident in the redefining of disciplines or forms of professional design and the emergence of new ones in industry and beyond. Some of these disciplines or types of design are already established in government and evident in the materials used for this review.[footnote 106] As the Literature Review[footnote 107] synthesised for this report shows, they include the following specialisms:

- Communication design

- Content design

- Interaction design

- Organisation design

- Policy design

- Service design

- Strategic design

- Urban design.

In some cases, these design specialisms have a clear relationship to existing roles, professions, teams, and processes in government such as the Central Digital and Data Office.[footnote 108] In others, they don’t. For example, search for job descriptions for ‘service designer’ and ‘policy designer’ on the Civil Service jobs portal[footnote 109] and you often find the former, rarely the latter.

Specialisms within design continue to develop. The emergence of public design co-exists within a changing landscape in the early 21st century. There are related developments in other areas of society, in which practices of design are at the forefront of innovation and transformation:

- Co-design emerged in the 2000s as an approach, methods and tools to involve citizens and users in design processes. Its roots are in ‘participatory design’ in the 1970s and 1980s, an area of research and practice in Nordic countries, based on the principle of involving workers likely to be impacted by the design of new technological systems in their design. For example, a recent report by Demos advocating participatory policymaking included co-design workshops as one method.[footnote 110]

- Social design is a term that foregrounds variants of design practice and research oriented to understanding design’s relationship with and impact on society and social issues. For example, a collection of articles by academics from several design fields at University of the Arts London reveals a strong orientation to applying design towards positive societal transformation across many spheres of life, from the justice system to textiles to health.[footnote 111]

- Civic design is a term used in the USA to focus on the design of democratic processes. For example, the Center for Civic Design[footnote 112] is an American non-profit organisation that works to re-imagine elections and improve the design of voting systems.

- In the field of law, the term legal design emphasises making legal services accessible and inclusive, with associated specialised practitioners, events and publications. For example, a short review by the Law Society of England and Wales[footnote 113] noted the importance of enabling the communication of legal concepts, as well as improving the design of artefacts associated with legal practice, such as contracts, so they are easier to use.

To conclude, over the past 20 years, expertise and approaches associated with industry have been adapted for and in relation to government and the public sector, alongside the further development of design for and in society. The next section delves more closely into public design in the UK government and the outcomes and impacts to which it contributes.

5 What does public design achieve in the UK government?

We now turn to reviewing public design in the UK government, with a particular focus on central government, reflecting the scope of the Public Design Evidence Review. To do this, we synthesised materials produced for this review (i.e. the Case Study Bank,[footnote 114] Design Thought Leader report,[footnote 115] Literature Reviews[footnote 116],[footnote 117],[footnote 118] and report on the Design Council roundtables and survey)[footnote 119]. This section discusses how public design results in tangible (and sometimes cashable) benefits to government which address the challenges they face outlined earlier.

Building on evidence for the Public Design Evidence Review, we propose a way of understanding how design practices lead to outcomes and impacts for government.[footnote 120] In particular, we draw on and synthesise published academic research, illustrated by the case studies included in the Case Study Bank,[footnote 121] Design Thought Leader report,[footnote 122] and the Design Council report.[footnote 123] The literature includes studies that focus on the relationship between design and innovation, as process and outcome, which reveal many, sometimes contradictory, perspectives.[footnote 124] In addition, we reviewed efforts to measure the value of design and return on investments in design[footnote 125] including in the public sector. In summary, these show positive outcomes and impacts from the use of design, which we adapt for the context of government.

Public design practices achieve five significant ‘outcomes’ or intermediate benefits and help drive longer-term benefits or ‘impacts’ for government. Our synthesis of the evidence suggests these outcomes are collaboration, insight, inspiration, de-risking of operational delivery, and increased legitimacy.

Through their combination, these outcomes lead to impacts for government, in the form of innovative solutions to policy challenges, increased effectiveness, increased efficiency, and a reduced gap between government and citizens. In the discussion that follows, we illustrate these with aspects of the case studies included in the PDER Case Study Bank[footnote 126], where several achieve more than one outcome or impact. Where the evidence about public design in the UK Government allows us, we show these benefits. Where it does not, we draw on the wider knowledge base.

5.1 Outcomes from using public design

Collaboration

The first outcome of applying public design is collaboration. This results from public design’s capacity to enable people to work together practically – for example through workshops and co-design exercises – to integrate, synthesise and facilitate perspectives, evidence and expertise into a purposeful iterative process. Collaboration practices rooted in public design have a shared emphasis on learning as a system alongside generating solutions.

Collaboration is present throughout all the case studies included in the Case Study Bank;[footnote 127] it forms the foundation from which all other impacts and outcomes arise. In essence, collaboration is the core theme that underpins any public design activity.

For example, Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) generated insight when overcoming the challenge of incorporating the UK government’s policy intent of reaching net zero carbon emissions into digital delivery. Designers at (Defra) found little detailed guidance on how to consider the carbon footprint of services they were designing, nor about how all the roles in multidisciplinary teams can support this goal. The team adopted a co-design approach, organising a series of collaborative sessions with people from across government departments, local authorities, and supplier partners. This enabled the collection of a diverse range of views and ideas from those working on digital projects and the rapid evolution of a set of principles shared on a government blog. Defra now intend to evolve these principles further, in order to publish them as an official set of standards. The project enabled closer alignment between public sector bodies about digital sustainability.

In another case study, the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) wanted to explore how to more effectively resettle prison leavers back into the community after a prison sentence in order to reduce re-offending, estimated to cost £22.7 billion a year, and to protect the public. Combining a systems thinking and service design approach, MoJ’s team of policymakers and service designers engaged with over 500 people across the criminal justice system including His Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service. This resulted in a comprehensive analysis of the complex causes impacting resettlement and how to target improvements over the longer term. Visual design and narratives were used to synthesise evidence into materials that could easily be understood and engaged with. The team identified ‘opportunity areas’, shared these with operational partners, and invited them to challenge the thinking, give feedback, and discuss how each opportunity area related to delivery priorities. As a result of this approach, work from MOJ and partners in coming years will be informed by a holistic, collective understanding of resettlement informed by insights from organisations across the justice system.

As the practices shown in Table 1 emphasise, collaboration can work through enabling citizens and others to engage in the policy cycle, as well as facilitating cross-government and multi-disciplinary working. Expertise in co-design is a practical and achievable way of bringing in varied and diverse voices and information to exploring issues and generating options collectively. One thought leader summarised it succinctly: “it has to be about designing with people, not designing for them” (Matt Edgar).[footnote 128]

Insight

The next outcome (achieved through collaboration, as explained above) is insight, reflecting the capacity of design practices to bring in and make sense of diverse perspectives from the ‘real world’ of organisations, communities and places within the design and development of policy interventions. Public design approaches are oriented around people’s experiences and journeys through ‘the system’ as they engage and interact with, or use (digital) objects and services associated with government in the places and communities where they live. Public design practices shift or zoom between inside/outside perspectives, combining a big picture ‘systems view’ as well as attending to what it’s like for people ‘on the ground’.

One case study[footnote 129] which exemplifies this outcome is Cabinet Office’s Disability Unit and Policy Lab’s efforts to understand the daily life of people with disabilities. The project team conducted in-depth interviews, journey mapping, storyboarding, and diary writing to gather information which was then used to set meaningful strategic direction. Significantly, the team also undertook ethnographic research over multiple years – the result of which not only brought people’s experiences to the fore and provided weighting to the evidence for policymakers, but also provided a unique opportunity to capture evolving experiences and expectations throughout the Covid-19 pandemic. This depth of insight may not have been achievable in a shortened time frame, also highlighting the value of sustained engagement. Since the work was completed, it has been used to inform public consultations and contextualise statistical data releases by grounding them in disabled people’s lived experience, and is used internally to shape discussions among staff about purpose.

A further case study which illustrates insight was the Department for Work and Pensions’ (DWP) project4 which sought to understand why unpaid carers leave employment, and how they might be better supported to combine working and caring, if this is in their best interests. Care Choices was undertaken in collaboration with the Departments of Health (as it was then), Business and the Government Equalities Office – showing that a systems view was adopted from the beginning. Detailed evidence-based ‘personas’ were used to consider the experiences and needs of carers from the point when they first start caring. The caring journeys that each persona would ideally take in terms of existing policies were mapped, and then reconsidered in light of likely challenges that those new to caring would face. Such challenges included limited time, energy and knowledge to navigate a complicated and fragmented system of support services. Highlighting the perspective of carers and mapping how they experienced systems of information and support enabled the cross-government team to recognise and better understand the needs of a previously un-named group, ‘potential carers’, working people facing decisions about work and care, and use their lived experience to focus interventions on their previously under-recognised needs.

In both examples, generating insights surfaced and helped manage uncertainties by identifying and mitigating risks and complexities. The insights helped to identify effective intervention points ensuring resulting services met the needs, behaviours and experiences of citizens.

Inspiration

A further benefit of looking at things from the perspective of people’s lived experience and using visualisations of systems and infrastructures, is that is offers inspiration (the third outcome) for the policy process. This, coupled with hidden assumptions being revealed, allows for policy challenges to be better understood and thus reframed to address a given problem in a more meaningful and effective way. Through hearing different voices, perspectives and experiences, researchers and policymakers, along with delivery/operations professionals and citizens, often envision new, creative solutions.

A case study[footnote 130] from the Department for Education (DfE), which aimed to address concerns around low take-up of teaching roles, demonstrates inspiration and creativity. DfE undertook a review to re-imagine how education would look if designed from the perspective of those at the front-line, including teachers. A multi-disciplinary team of policy professionals, researchers, analysts, designers, and delivery specialists worked with teachers to look at education services from their perspective. The team mapped out publicly funded services and reorganised them in a way that would make sense to a teacher at each stage of their career. These activities enabled the team to create a new, joined-up service designed to inspire, attract and support potential teachers. This new service also works as a method to collect real-time data, which then allows the service to be continually improved. Further, DfE teams began to restructure themselves to reflect the teacher service lines and let go of the idea that ‘policy’ and ‘delivery’ were separate things. By taking a systems-thinking, creative approach and bringing policy and delivery into single teams, DfE was able to see challenges from the perspective of service users and develop a systems map as a framework for future policy design innovation.

The Design Council also became inspired through their workshops with Northumberland County Council and residents in Amble (a fishing port in Northumbria), which aimed to explore how a recently closed industrial site could benefit the community. The original scope of the project was offsetting the significant local job losses, with suggestions including alternative businesses the site could be converted to. However, perspectives from the local community ultimately reframed the challenge from this, to reinventing the entire port as a tourist destination – thus benefitting the whole town. The project co-created a shared vision between local businesses, the local tourist board and the police for regenerating the area with an array of ideas for local self-employment. The new, co-created framing underpinned further initiatives and investment. It contributed to Amble winning the High Street of the Year award in 2015 and being listed in the Sunday Times as one of the top places to live by the sea in 2019.

Inspiration and creativity associated with design practices may be less familiar than other forms of knowledge and work in public administrations but is seen by some (and shown by these examples) as essential for transformation. As one of the thought leaders put it,[footnote 131] “today’s big challenges are fundamentally creative challenges. They require discovery and leveraging knowledge in new ways. They involve creating things that don’t exist yet” (Marco Steinberg). By accessing novel perspectives in both examples, hidden assumptions could be revealed, allowing for policy challenges to be better understood and thus reframed to address a given problem in a more creative and effective way.

Overall, each previous outcome reinforces the other, creating a strong foundation for developing, testing, legitimising and delivering creative and effective responses to the challenges facing governments. Collaboration brings diverse perspectives together, insight uncovers hidden assumptions and deeper understanding, and inspiration drives innovative thinking. Alone – the design practices and their outcomes add significant value, but they also enable further benefits within the design process.

De-risking operational delivery

Using public design practices also establishes and sustains feedback loops and collective learning between people, contexts, and proposed ‘solutions’ or interventions. Such learning and dialogue helps to de-risk operational delivery (the fourth outcome), which is widely perceived as a significant benefit of engaging in public design. Design practices such as iteratively prototyping solutions with stakeholders can surface assumptions and reveal the ‘fit’ between proposals and existing processes and infrastructures, activating stakeholders’ knowledge of operational context and citizens’ lived experience. One case study[footnote 132] which exemplifies this is as follows:

The Universal Credit team at DWP embedded approaches such as having a focus on the ‘service experience’ (of claimants, supported by DWP staff) alongside cycles of prototyping to test improvements at small scale before implementing more widely. To achieve this required multidisciplinary teams with expertise in digital, policy and operational delivery working in partnership to optimise the design and delivery of an effective multi-channel service considered in the round. As can be seen in this example, and as the Design Thought Leader report[footnote 133] argued, activating these feedback loops requires a mix of technical and relational skills that when applied together, cross boundaries and departmental silos to enable sense-making and learning in ways that allow people to experiment with new approaches and test, validate and refine proposals. The thought leaders interviewed described how design practices like testing and prototyping could help surface potential problems early on, which could further help mitigate risks of failure. As one reflected, “right through the scaling process for me, you want to continue to have that innovation approach where you’re learning, where you’re measuring, and learning and testing and tweaking…until you’re at full roll out and embedding something that makes sense” (Julia Ross).

Another case study[footnote 134] which showcases this, as well as early problem identification, is HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC’s) Policy Lab’s collaboration with policymakers to reduce plastic waste through the introduction of a new tax. A call for evidence gained a significant number of responses – underscoring not only the importance/urgency of this issue, but also the pressure to deliver an immediate solution. However, by undertaking in-depth research including observational field studies and interviews with different stakeholders, the team were able to achieve an understanding of processes and behaviours with key businesses in the plastic supply chain. Participatory workshops helped to map out and visualise different customer journeys assisting in anticipating how people might interact with the tax and account for it. By testing different scenarios and producing ‘personas’, policymakers were able to identify potential unintended consequences for taxpayers, minimise them, and work out what was viable. For example, highlighting potential inequalities between use of plastic in commercial settings, or administrative burdens due to transport packaging. Significantly, it also identified inequalities in medical settings, where plastic use cannot be avoided, enabling certain exemptions to be implemented. These personas enabled greater attunement of policy development to the particular needs of different citizens impacted by the policy change.

Using these elements of public design results in early and improved understanding of what the problem or situation is, from the perspective of people whose lives are directly connected to it as citizens or on the front line of public services, as well as how a proposed intervention is going to work and how it might ‘land’. In both examples, risks associated with significant policy changes, and unintended, downstream consequences for alternative parts of the system, were reduced.

Increased legitimacy

Public design practices also help build increased legitimacy (the fifth outcome) for the ways in which problems are defined during the early stage of policy or service design, while developing potential solutions, and during elaboration and assessment of options. Practices of design such as co-designing, testing and iterating proposals in context, work to engage and build trust with those involved in front-line delivery or advocacy, including citizens or service users. Two case studies bring this to life below.[footnote 135]