Public Design Evidence Review: Case Study Bank (HTML)

Updated 21 August 2025

Contributors

| Case Study | Author(s) |

|---|---|

| Addressing plastic tax in the UK to stimulate the reuse of plastic products (HM Revenue and Customs) | Faye Churchill |

| Advice strategy for farming (Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs) | Nev Cavendish, Will Hallows, Becky Miller, Phil Stevenson, Anne Thurston |

| Automatic Enrolment into Workplace Pension Schemes (Department for Work and Pensions) | Claire Ferguson, Hannah Langton, Ben Savage |

| Co-designing a set of principles for the design and delivery of greener digital services (Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs) | Ned Gartside |

| Improving the delivery of policy outcomes through user-centred grant decision-making (Ministry for Housing, Communities and Local Government) | Naomi Grayburn, Kate Harries |

| Re-designing the immigration and asylum appeals services (Transform and HM Courts and Tribunals Service) | David Singer |

| Reducing spiking offences and increasing prosecutions (Home Office) | Sally Halls |

| Regenerating a seaside community (The Design Council and Northumberland County Council) | Jessie Johnson |

| Reimagining education services from the perspective of frontline workers (Department for Education) | Rachel Hope, Andrew Knight |

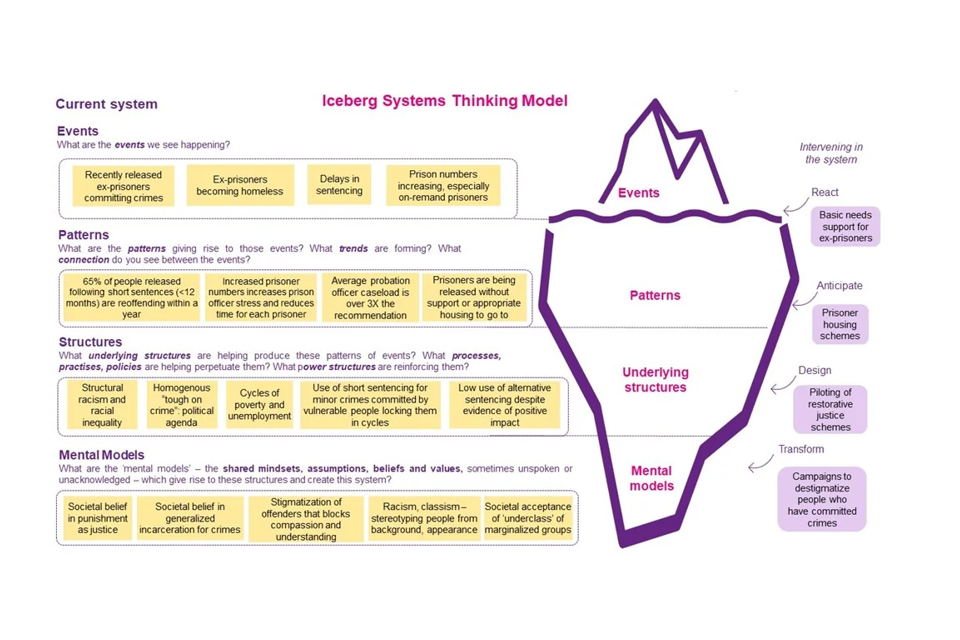

| Setting a 2030 vision for resettlement from prison into the community (Ministry of Justice) | Jeffry Allen, Kate Haseler-Young |

| Supporting unpaid carers to remain in work (Department for Work and Pensions) | Will Glinski |

| Understanding and communicating the lived experiences of disabled people (Policy Lab and Disability Unit) | Alex Mathers |

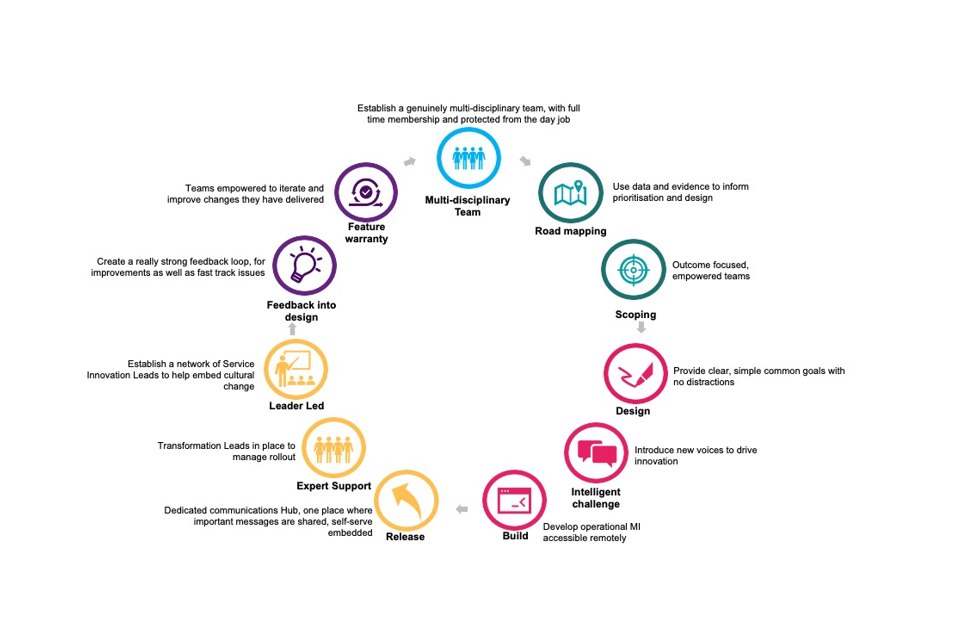

| Universal Credit service (Department for Work and Pensions) | Lewis Childs, Sam Elkington, Kat Gough, John Turnbull |

Coordinators

Cate Fisher, Russell Henshaw, Alice Holmes, Naomi Sheppard

Wider contributors and reviewers

Allie Armantrading, Heather Bramwell, Kate Bruckshaw, Charlotte Clark, Catherine Durose, Carla Groom, Penny Harrison, Solene Heinzl, Daniel Clegg-Hughes, Chris Dennis, Jemima Higgins, Lisa Jeffery, Lucy Kimbell, Sophie Lambert, Kate Langham, Latifa Mahdi, Neil Meldrum, Owain Nash, Rebecca Papanicolas, Laura Wood, Laura Yarrow.

Introduction

The Public Design Evidence Review Case Study Bank is one of the strands of evidence that makes up the Public Design Evidence Review.

Following a Civil Service Policy Design Community ‘call to action’ in early 2023, a broad range of case studies were submitted. These came from across and outside of government, providing diverse examples of where and how design practices were being applied in the public sector.

A subset of 13 of these case studies are published here. They have been chosen to include:

- examples from across central and local government

- the application of design across a range of policy, strategic, and service problem spaces

- different design practices

- different resourcing models within and beyond civil service.

These case studies are intended to provide real-life examples of how design practices are being used in the public sector. They are not intended to represent a comprehensive view of the full spectrum of public design practices that are, or could be, applied across government. Nor do they provide a comprehensive picture of how policy or operational design decisions are made across government.

Each case study tells a story of how and why design practices were used in the context of a specific problem space. Whilst acknowledging the challenges around evaluating the unique contribution of design practices, they also show the potential of design practices to improve outcomes and impact.

Addressing plastic tax in the UK to stimulate the reuse of plastic products (HM Revenue and Customs)

In early 2018, David Attenborough’s Blue Planet programme highlighted to the public the impact that plastic waste was having on the environment. Following this, the Government issued a call for evidence seeking views on how taxation could address the problem of plastic waste.[footnote 1] This call for evidence received an extraordinary number of responses, circa 162,000, which demonstrated the strength of public and industry feeling about plastic waste.

In the summer of 2018, HM Revenue and Customs’ (HMRC) newly formed Policy Lab team were approached to see if they could support the policy team in exploring ideas and options for how taxation could be used to stimulate behavioural change. Set up to embed user-centred design thinking into the policymaking space, the team works with policymakers by using evidence and insight to explore ideas and options, inform the policy consultation process, and de-risk delivery. Across government HMRC’s Policy Lab worked with HMRC Policy, HM Treasury, Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra), and Environment Agency colleagues over a period of 16 months.

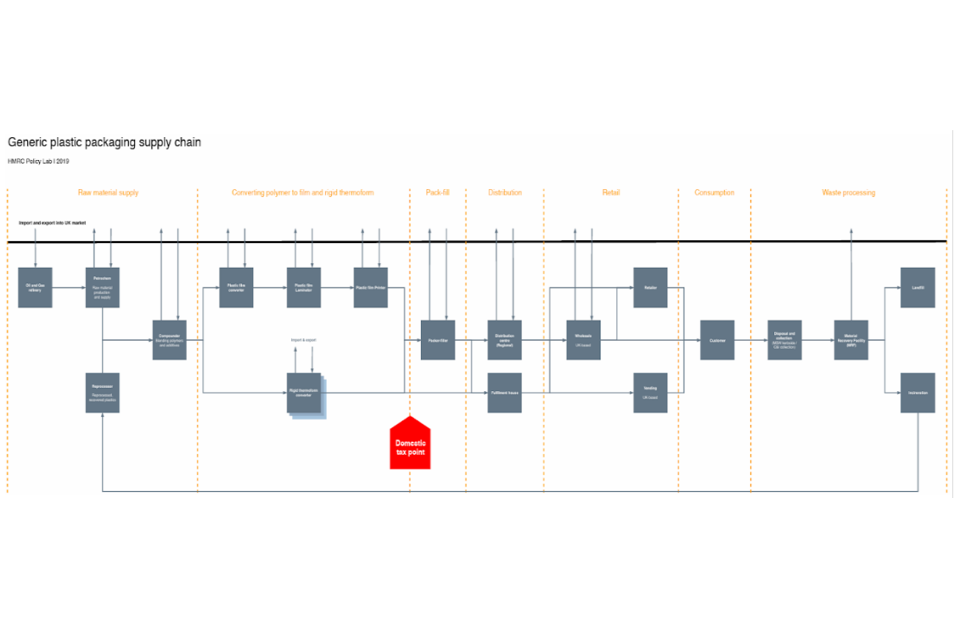

Several ideas for how taxation could be used were explored. What the Policy Lab team quickly realised was that a comprehensive understanding of plastic products, spanning from their creation to disposal, was needed. This meant the first big task was to create a supply chain map. The team conducted observational field studies – a way to help us understand what people and businesses do: through observing and asking questions in their own environment. The aim was to gain an understanding of processes and behaviours with key businesses in the plastic supply chain, including petrochemical plants, convertors (who shape and change plastic pellets into products), pack-filling businesses (who pack products for other companies), and import/export businesses.

Insight building created a rich view of the cycle of plastic production (Figure 1). As part of this process, the team also looked at other government policies/regimes that related to plastic waste. Engaging with Defra and Environment Agency colleagues to understand the Packaging Producer Responsibility System was particularly important in this respect.

Figure 1. Supply chain map showing different parts of the plastic packaging process.

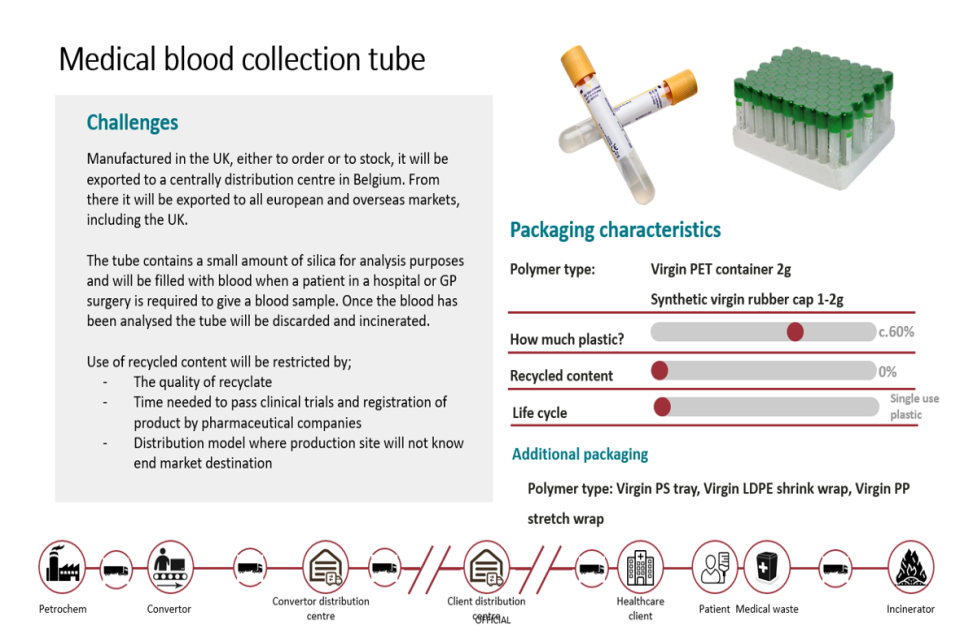

In the lead up to Autumn 2018, what might be taxed and how that might be achieved was still fluid. Exploring the properties of particularly wasteful products generated insight around whether it was possible to target specific products for certain uses. It was concluded that this would be very hard to administer but recognising constraints was valuable because it raised awareness of product types and regulations that were associated with the creation of plastic products. As a consequence, ‘product personas’ were developed and became used throughout the work that Policy Lab did (Figure 2). The ‘personas’ helped us understand the different properties of plastic products, how they might be used, transported, and manufactured.

Figure 2. An example product persona for a medical blood collection tube.

How does taxing something reduce waste?

In the 2018 Autumn Budget, the Government announced a world-leading new tax on produced or imported plastic packaging.[footnote 2] At the time the tax was subject to consultation but would apply to all plastic packaging that does not include at least 30 percent recycled composition content, thereby stimulating reuse by taxation. If you had products with more than 30 percent recycled content you didn’t pay the tax. As a concept this sounds relatively simple but there was still a lot of thinking to be done about how the tax would operate and who in the supply chain would account for it, and when – known as the tax point.

The supply chain map that was developed prior to the budget announcement helped crystalise where the tax point should be, but part of the work Policy Lab likes to do is think about unintended consequences. Using the product personas and what was known about industry regulations it was possible to highlight potential inequalities. For example, changing the composition of a plastic packaging product that is used to wrap a tie is probably vastly easier than changing a packaging product that keeps a medical device sterile. The team also prototyped understandings of the effort required by the taxpayer to account for the tax on transport packaging, something the taxpayer themselves may have limited to zero knowledge of, potentially creating significant administrative burdens. In both cases, exemptions were implemented, e.g. on the use of medical products intended for human use and for transport packaging used to import multiple goods.

Towards the end of HMRC’s Policy Lab work, all the insights that had been gathered were then used to support several workshops with subject-matter experts. The team used a design technique known as Event Storming, where people come together to map out and visualise possible customer journeys, enabling those involved to identify further policy impacts and decisions that needed to be made about overall user journeys.

The role of HMRC’s Policy Lab was to help provide Policy and HM Treasury colleagues with evidence to support their tax design decisions and recommendations. This work would not have been nearly as effective if it were not for their knowledge and openness to ideas. Collective work to generate ideas and options for plastic taxation was a really great example of cross-team working and collaboration made possible by colleagues’ willingness to engage with user-centred design approaches.

Plastic Packaging Tax went live in April 2022. Over 4000 businesses have signed up to pay the tax, and HMRC have collected approximately £476 million. The value of plastic content that is suitable for recycling has increased since 2018. Although this rise cannot be directly attributed to the tax itself, it does demonstrate that plastic waste is in demand and has a purpose beyond disposal. The team’s work concluded with an internal assessment against the Government Service Standards[footnote 3], proudly receiving feedback that their work was “bar raising”.

Advice strategy for farming (Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs)

Designing a farming advice strategy to increase uptake of new Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) funding and private finance.

When we left the European Union, its subsidies for UK farms came to an end: resulting in a potential deficit in farm incomes. The UK Treasury temporarily covered these subsidies; however, Defra had an opportunity to build new ways to support the farming sector and transition to balancing food security with the needs of the natural world.

Defra introduced new ‘environmental land management’ schemes to pay farmers to use sustainable farming practices, and to enhance and protect the environment. To meet government commitments, Defra would need to encourage more farmers than ever before to enter into an agreement to deliver new and more complex practices over time.

An analysis of user needs carried out by the Farming and Countryside Programme (FCP) found that consistent, good quality information would be critical. Challenging the ‘digital first’ approach our user research found that face-to-face advice was the most effective way for farmers to understand the changes to the sector - and predicted high demand for advice.

Advisers employed by the Government’s Arm’s Length Bodies (ALBs) like Natural England, the Environment Agency and the Forestry Commission have been working with farmers for decades. While excellent at their jobs, and often with well-developed relationships with farmers, they had insufficient capacity to meet the demand that would be driven by our aspirations for the new schemes.

The Strategic Advice and Information (SAI) team was charged with examining the ways farmers get advice and develop a strategy to meet their needs. The team was made up of policy professionals, business analysts, user researchers, a content designer, and a service designer.

In June 2021 the team started a ten-week ‘discovery’ stage where the goal was to understand problems or opportunities before developing solutions. Throughout the discovery, the team was able to respond to things they learned: modifying their research approach as they gathered more insights about farmers, land managers, and the farm advisers who support them. Interviews, farm visits, and workshops allowed them to better understand the needs, pressures, and differences in the sector. They found that farmers and land managers are a diverse group with varying needs and understood more about how factors influence them: such as their farm type and size, appetite for change, and succession planning.

For farmers and land managers, advice comes from many sources. The team conducted user research interviews and workshops with different kinds of advisers. They spent time observing advisers in the field to understand, in context, the challenges and opportunities for both government and non-government advisers in delivering ambitious environmental outcomes with farmers and land managers.[footnote 4] Face-to-face co-design workshops with advisers allowed the team to validate their findings and invite ideas on how Defra could support advisers in encouraging greater ambition. Most farmers seek advice when considering changes to their farm business. This might be from trusted colleagues, family members, an adviser they pay to help them, a charity representative (e.g. Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB)), or a local ALB advisor.

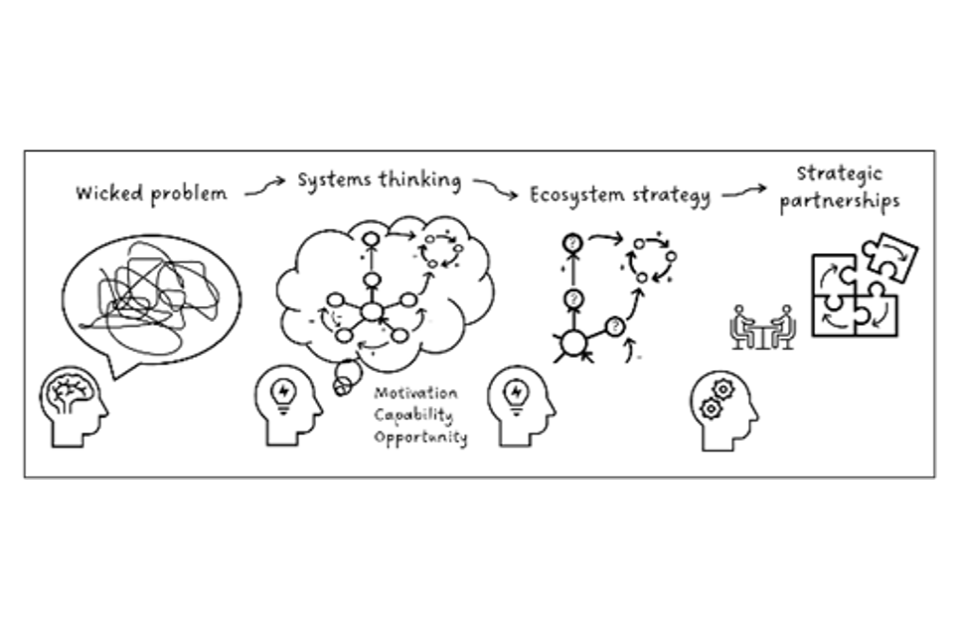

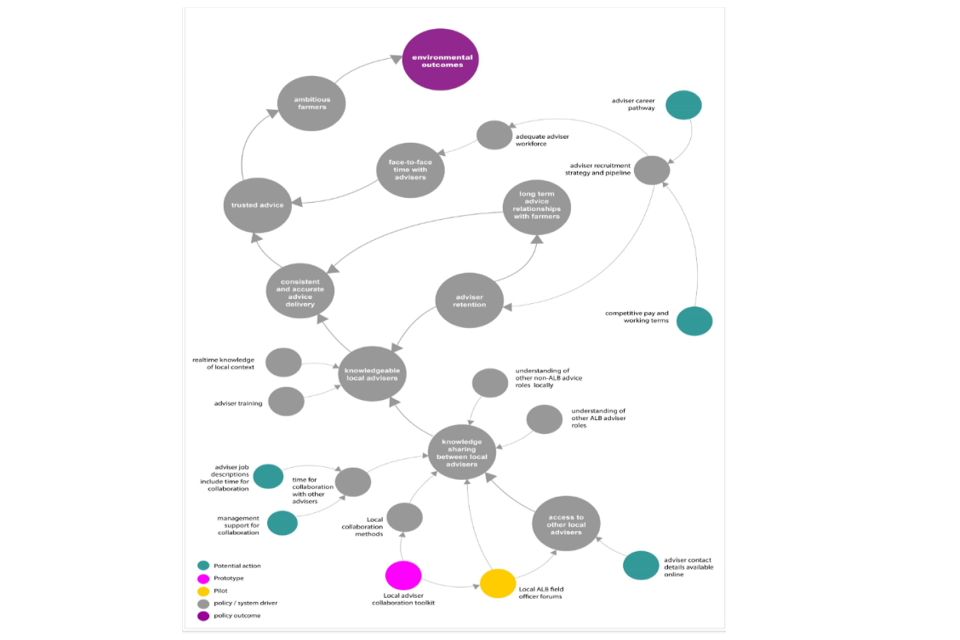

Systems thinking is a way of approaching problems by looking at them as part of a larger system, rather than just the immediate problem. The team used this approach to help them capture the complexity of farm advice (Figure 3). Business analysts in the team drew up an ‘as-is’ delivery model (mapping how advice is given at the present time) based on the team’s research. It included the organisations and roles that play a part in the system.

Figure 3. Illustration of systems thinking approach

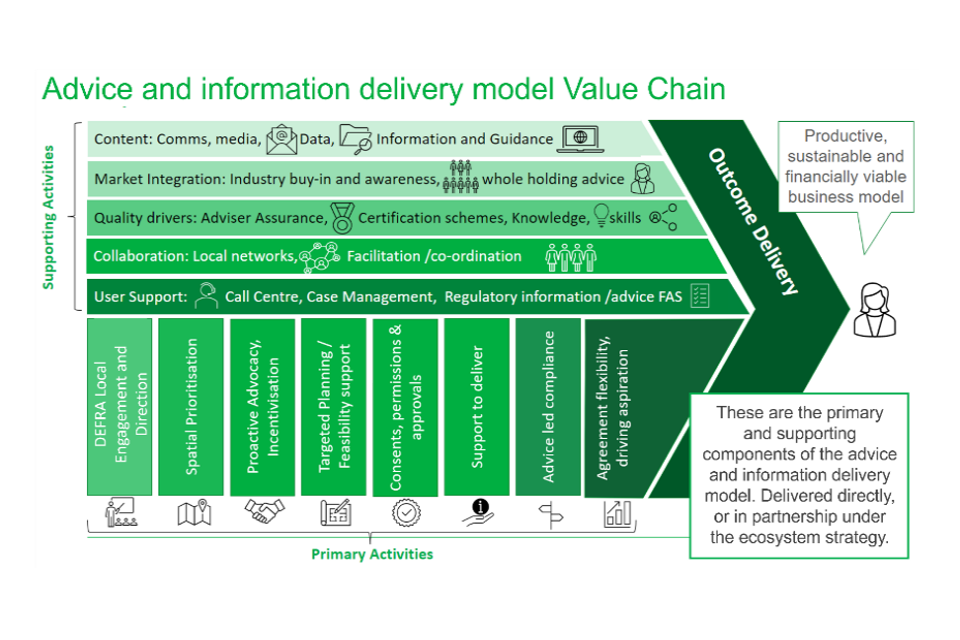

The business analysts also produced a value chain analysis of our user research – a value chain shows the various business activities and processes involved in creating a product or performing a service. Through this work, they visualised the activities in the advice and information system, which could lead to the delivery of productive, resilient and financially viable farms (Figure 4).

Figure 4. The team developed a value chain to show how different factors in the system contribute to outcome delivery.

By taking a systems thinking approach, the team found that leveraging existing local networks of commercial and charity sector advisers was the best strategic option to bolster the capacity in ALBs. They produced a “to-be” delivery model (mapping how advice could be delivered in the future) to illustrate how this might work.

Different types of advisers could each play a valued role and other aspects of the delivery model like peer learning, assurance, and formal training would all play an important part in the adoption of sustainable farming practice and maximising food productivity. The team developed a set of design principles to inform how ALB advisers’ time and expertise could be targeted, considering impartiality, risk, outcomes, intent, and social responsibility. The model supported engagement across Defra’s ALBs and with senior leaders. It also provided a focus for further co-design, prototyping, and user testing.

The insights from the research and workshops were also synthesised into a cause-and-effect system map (Figure 5). This helped visualise the factors driving trusted local advice delivery, and how this in turn drives farmer’s ambition, and ultimately delivery of environmental outcomes.

Figure 5. Designers developed a cause-and-effect system map to visualise the different interlinked factors driving local advice delivery, which in turn drive delivery of environmental outcomes

Graphic design and storytelling played a key role in communicating the strategy - using visual infographics and animated explainer videos. This visual design approach helped build understanding of the challenges and opportunities of advice delivery and its role in funding uptake. The approach won support from key stakeholders across the FCP and Defra’s delivery bodies, from senior leaders to field officers.

The Strategic Advice Team’s design-led work on the strategy is already impacting how the programme develops new policy and funding opportunities and how Defra’s delivery bodies evolve and coordinate their support to farmers and land managers. Other teams on the programme are starting to test prototypes and run pilots to understand which interventions are most effective in supporting trusted and consistent local advice delivery.

Automatic enrolment into workplace pension schemes (Department for Work and Pensions)

Background

In 2002, a Commission was set up to review the UK private pensions system. This was in response to projections showing that the public was not saving enough for retirement, especially with an ageing population. The Pensions Commission’s first report estimated that 9 million people were under-saving. They also found that 75% of Defined Contribution pensions would be insufficient by the time of retirement.[footnote 5]

Problem Definition and Early Stages of the Pensions Commission

The Pensions Commission was led by three individuals representing different perspectives: the private sector, trade unions, and academia. Along with a small support team, they aimed to understand the current pensions and savings landscape and develop future policy recommendations. From the start, the Commission sought to establish a substantial evidence base setting out the nature of ‘the problem’, its context and likely determinants. The Commission and Ministers also engaged heavily with various stakeholders, including opposition parties, civil servants, the pensions industry, employers, trade unions, academic experts, and the public. This consultation happened before any solutions were proposed. These extensive efforts to understand the problem laid the groundwork for designing a new and more effective system. Importantly, the evidence and consultation helped to build consensus, thereby creating the conditions needed over time for automatic enrolment to be designed and implemented effectively.

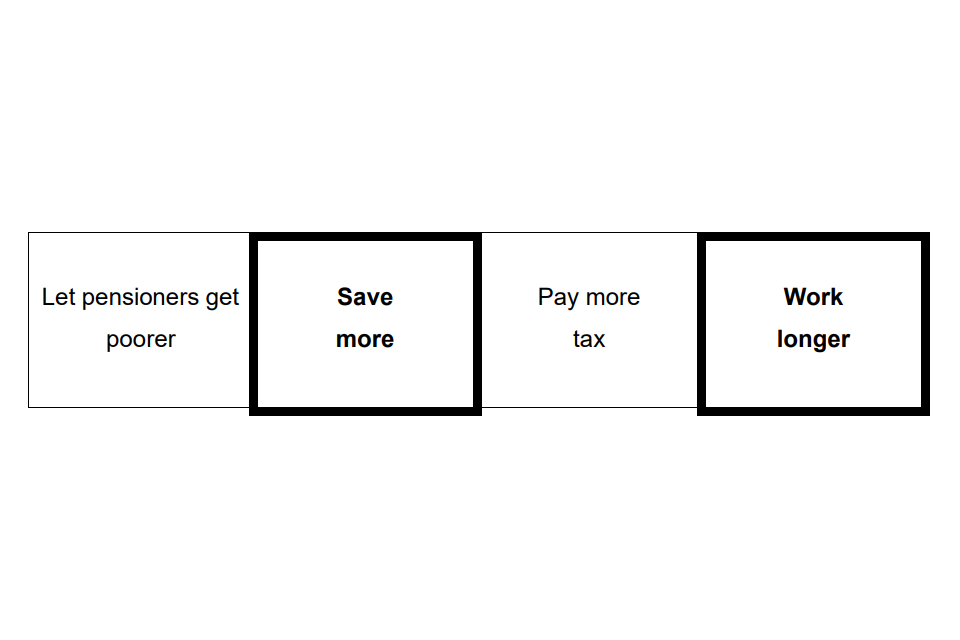

In their 2004 report, the Commission published a set of options based on the analysis and consultation they had undertaken (Figure 6). Special attention was given to the trade-offs. For instance, with the ‘pay more tax’ option, some argued it was fair since the UK had a lower tax ratio compared to similar countries. However, others felt it was unfair to place higher taxes on future generations to support the current one. It was also noted that higher taxes wouldn’t ensure the funds would only be used for pensions. Each option was carefully considered for its potential long-term impact on the broader system.

Figure 6. Options based on Pensions Commission analysis and consultation.

| Let pensioners get poorer | Save more | Pay more tax | Work longer |

The Commission organised national debates to discuss these options. It held regional events and created a Citizens Advisory panel that represented the wider population’s demographics to help refine ideas for a National Pensions Day. On that day, over 1,000 people attended six events across the country. Participants provided feedback and voted on their preferred options. Additionally, online debates were used to gather more views. These discussions educated people about the difficult trade-offs and allowed them to make informed decisions on the best choices. Ultimately, the options of working longer and saving more were chosen as the preferred solutions.

Learning from Successes and Failures

Once the broad direction was agreed, the Commission investigated existing measures to encourage saving. It used research funded by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP), which tested approaches mainly based on providing information: known as ‘informed choice’ methods. The results showed that these methods only slightly increased savings. For instance, ‘Pension Information Packs’ did not appeal to younger people, and most people of all ages said they would not read these packs on their own.[footnote 6] Reviews of the Pension Education Fund found similar results.[footnote 7] Additionally, relying on these methods risked increasing inequality, especially among young people.[footnote 8]

Understanding barriers to saving

The Commission looked into the barriers people might face when trying to save for retirement, especially within the UK. It found most people did not make decisions about saving for retirement in seemingly logical and well-informed ways. This was, in large part, due to the overwhelming variety and unpredictability of investment options. Such complexity made people delay important financial decisions unless someone else, like an employer or the government, encouraged them to act. Over time, this risked increasing inequality: those already saving continued to save, whilst those not saving continued to not save. However, even among those who did save, the complexity of investment options risked undermining retirement outcomes. Bewildered, many people simply chose to invest in things they were familiar with, such as their employer’s company. This was despite high-profile scandals having illustrated the risks of such a strategy.[footnote 9]

The Commission found that while such problems were common across many countries, there were also barriers to saving for retirement that were specific to the UK, including:

- Frequent changes to the state pension system by successive governments had made it nearly impossible for people to understand what state pension they could expect to receive in retirement. Different tax relief rates, varied administrative costs, tax credits, and differences in employer contributions to workplace pensions all added to this confusion.

- A lack of trust. This related both to advisors, following previous mis-selling scandals, and to government pensions policy, due to the frequency with which successive governments had changed state pension promises.

- A decreasing belief among employers that providing good pensions would help them to achieve recruitment and retention objectives. For example, the Commission quoted one employer as saying:

“…many employees don’t place the same value on pensions that they do on other benefits… Put bluntly, if employees don’t value pensions sufficiently, employers are less likely to provide them.”[footnote 10]

- Pension providers being unable to profitably serve the needs of some groups, including lower earners, those working for smaller firms, and self-employed people.

Due to all these barriers, the Commission concluded that the voluntary private funded system, combined with the current state system, was not fit for purpose. Instead, a different type of approach would be needed: one which could change the system surrounding people, rather than relying on people to start saving on their own.

Exploring alternative approaches

As one alternative, the Commission identified evidence from international pensions schemes that had successfully increased workplace pensions saving by automatically enrolling staff. There were risks in assuming that ‘what worked’ in another country would work in a U.K. context. However, by drawing on insights from multiple such schemes, the Pensions Commission built an understanding of what strategies were effective and why others failed. This facilitated risk assessments that considered which strategies were most likely to be successful, despite having not been previously attempted in the U.K. As a result, the Commission proposed the creation of a National Pension Savings Scheme (NPSS) in its Second Report[footnote 11], with features including automatic enrolment, an employer contribution, individual accounts, and low annual management charges.

Learning how to make automatic enrolment work in practice

The Pensions Commission had established clear goals. As a result, those involved in designing automatic enrolment shared a common view of the problem they were trying to solve, and what automatic enrolment was trying to achieve: more people saving more.

Despite this clarity of purpose, a key challenge remained: how to design and deliver automatic enrolment in practice. Achieving this included the following approaches:

- Creating a simple, one-page, evaluation strategy early on that everyone working on automatic enrolment could use to guide their thinking and decisions.

- Creating dedicated teams to focus on specific perspectives: one team for employers, one for employees/individuals, and one for the pensions industry. The idea was that if the policy met the needs of all these groups, it would be well-designed.

- In addition, creating other teams to work on broader issues such as compliance and governance. Ensuring employers would comply with their new legal duty to enrol eligible employees would be critical to automatic enrolment’s success. It would mean that employees benefited from automatic enrolment and that good employers did not lose out to any businesses willing to shirk their legal duties. Equally, designing good governance arrangements would be critical to ensuring effective collaboration between the multiple organisations (DWP, the Pensions Regulator and the National Employment Savings Trust (NEST)) tasked with implementing automatic enrolment.

- Holding regular discussions and workshops with employer and employee groups to figure out how to implement automatic enrolment. These looked at options, such as embedding it in employment contracts, and considered the real-world barriers to implementing them. The discussions focused on what would be acceptable to both employers and employees, considering risks such as potential employee opt-outs or whether employers might pressure employees to opt out.

- Undertaking qualitative and quantitative research with employees and employers to explore and test scenarios (“what would you do if we did this or that?”) and to quantify and predict risks such as the likely level of opt out.

- Establishing governance arrangements which supported effective collaboration between the different organisations involved in designing automatic enrolment. Crucially, this was not about avoiding or suppressing conflict, which could have risked ‘groupthink’ and poor-quality decision-making. Rather, leaders brought participating organisations around the table and created opportunity for them to disagree and surface their conflicting needs. Through sometimes difficult conversations, these conflicts could then be resolved. Participating organisations were given accountability for decisions and any trade-offs made, which motivated them to reach the best overall decision.

- Focusing on solving problems rather than becoming defensive or apportioning blame: with consultants sometimes brought in to help internal teams resolve conflicts when needed.

- Valuing openness: including not presuming to know everything, being keen to talk to and learn from others, and acknowledge and learn from mistakes.

- Adopting an ‘80-20’ strategy, with the focus being to ensure automatic enrolment worked for most people, rather than attempting to address every aspect and potentially getting sidetracked by atypical cases.

Implementation, adaptation, and success

The likely reasons for automatic enrolment’s success were discussed in both a 2015 National Audit Office (NAO) report[footnote 12] and a preceding report by the Institute for Government[footnote 13]. These included the Pension Commission’s role in establishing clear aims and consensus in support of automatic enrolment, as well ongoing leadership, governance, and management during implementation that prioritised collaboration and stability. There were few changes in key personnel, a clear understanding of the respective roles of DWP, the Pensions Regulator and NEST, and close, stable working relationships between them.

Together, these conditions also provided a key ingredient critical to automatic enrolment’s success: time. Implementation occurred from 2012 to 2019. Between 2012 and 2015, automatic enrolment became mandatory for large and medium sized employers. Between 2015 and 2017, this was extended to small and micro employers. The minimum amounts employees and employers were required to contribute were also phased-in. Reaching their full amount, 8% of earnings, in 2019. This phased roll-out facilitated learning and adaptation, including through testing assumptions and refining processes. For example, an initial three-year implementation period was extended due to the onset of adverse global economic conditions.

Furthermore, potential implementation problems were anticipated and addressed early on. For example, early discussions had surfaced the risk that employers might attempt to coerce employees into opting out.[footnote 14] Accordingly, wider regulatory and enforcement powers were granted to the Pensions Regulator, encouraging an approach that prioritised workplaces where participation was considered most at risk. By making examples out of any employers attempting coercion while also offering support to those genuinely struggling in the early stages, the Pensions Regulator was able to minimise the risk of adverse behaviour. Similarly, employee insight helped inform decisions, such as on how to design opt out forms. While designers’ initial instincts had been to mention the option to opt out at the end of the form, employees themselves suggested it should be mentioned at the start. This reflected a desire for openness similar to that held by the Automatic Enrolment programme teams themselves.

Over the roll-out period, the Pensions Regulator and DWP ensured employers and individuals received tailored communications. The Pensions Regulator website contained dedicated areas for employers, intermediaries, pensions professionals, trustees, and individual: recognising that different parts of the system would need different information.[footnote 15] Prompting letters were sent to employers, along with emails that directed them to the Pensions Regulator website. Adverts in the media aimed to minimise the risk of employees opting out: by reminding them that “a workplace pension is like having another you, at work, helping you earn money for when you retire”. [footnote 16] Whereas previous ‘informed choice’ interventions had unsuccessfully relied solely on communications and information provision, the success of automatic enrolment demonstrated how communications and information provision could help achieve policy goals. By acting alongside and in cooperation with – rather than instead of – regulation and enforcement activity.

Throughout the implementation of automatic enrolment, ongoing research and evaluation ensured the Automatic Enrolment programme could monitor and understand progress as well as respond as necessary to any unanticipated challenges. This included financial crises, as well as considerable political change, and multiple Prime Ministers. As the world changed, the policy and its implementation could adapt with it.

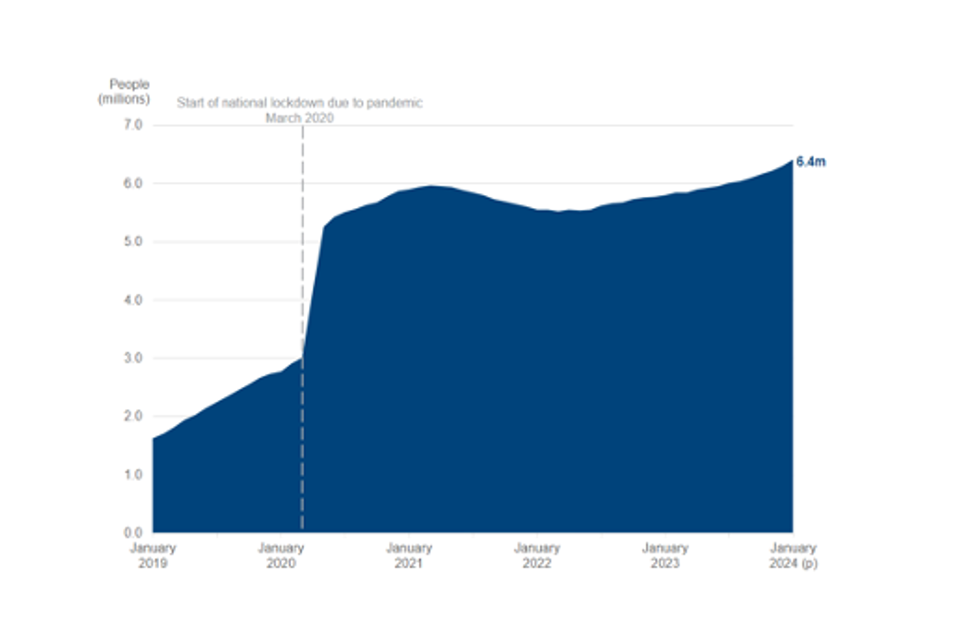

Since its introduction in 2012, automatic enrolment has transformed UK pension saving. The number of eligible employees participating in a workplace pension increased by 9.7 million to 20.8 million by 2023, with total annual savings for eligible savers reaching £131.8 billion by 2023.[footnote 17]

Co-designing a set of principles for the design and delivery of greener digital services (Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs)

In 2022, a group of designers in the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) self-organised to lead the development of a set of principles that deliver ‘greener’ digital government services across all the stages of project lifecycles. Utilising the methods of ‘co-design’, a series of collaborative workshops were arranged with participants from a wide range of disciplines to gather ideas on creating and then evolving a set of prototypes for these Greener Service Principles. This work has mapped nicely into Defra’s role as lead department on digital sustainability across Government, and the principles are intended to support digital teams across different departments and services once published.

In the early months of 2022, a number of designers in Defra, sharing concern for the environmental crises facing the planet, came together to discuss a particular problem: while various strategy papers made it clear that sustainable digital was key to helping government departments deliver on net zero carbon emission goals, many working on designing digital services didn’t know how we could contribute to the realisation of these ambitions.

As the group researched, it became clear that there was little in the way of detailed guidance or training materials available to up-skill the various roles involved on multidisciplinary teams on how to collaborate to deliver lower-carbon services. In turn, this meant that incorporating broad policy intent around net zero into ways of working at the level of digital delivery would likely remain a challenge. The group, therefore, decided to gather what information they could find about best practice with the intent to form what they had found into a set of principles for ‘Greener Services’.

Why a set of principles?

The power of principles is that they are not hard and fast rules, but ideas, guidelines, and shared reference points that can direct our thinking and behaviour on a particular topic. As many were new to this subject area, a set of principles for greener services could introduce the topic, help teams understand best practice and then (in time) signpost to specific training materials and other information when they are ready. When mature, a set of principles could also be treated as standards against which service projects were assessed.

Prototyping and co-design

By the time 2023 began, the first prototype set of principles had been sketched, and the team were ready to start socialising their efforts with colleagues across government. They chose to adopt this approach as sharing early prototypes, prompts engagement and dialogue. Gathering feedback in this way is generally the best and fastest route to evolving something that works well for its intended audience. As the Government Design Principles[footnote 18] put it, “Iterate. And then iterate again” - and do so ‘in the open’ so all can see and contribute if they wish.

Figure 7. Image of colleague involvement in prototype development.

The team’s first wider engagement came at Services Week in February 2023, when they ran a session to present principles and invite a discussion on their intent (Figure 7). This generated a deal of interest and resulted in people from a wide range of roles, across government and the supply chain, getting in touch to offer their support. When summer came, many of these newfound allies and collaborators were invited to join a series of online workshops organised with the support of innovation consultancy Transform UK. These sessions asked participants to think about projects they had recently worked on and to design principles that would be relevant to delivering more sustainable outcomes in those cases.

Developing a community around this work was a key priority for the team. In this context that meant giving those enthusiastic about the topic the opportunity to contribute to and shape the work over a period of time. The next major event in the co-design calendar came with the ‘Greener Services Hack Day’ that was organised in March 2024 in collaboration with TPXimpact, who hosted the gathering (Figure 8). This session brought together over 70 practitioners from a range of different disciplines. After presenting them with the latest iteration of the Greener Service Principles participants were challenged to think about how these could be applied to a particular service design challenge.

This method brought great benefit as it enabled the collection of a diverse range of views and ideas from those working on digital projects. It helped point to ways the principles needed to evolve to ensure they were most useful to their potential future ‘users’, whatever their angle and role. For example, the policy designers in the room were able to point to some of the nuances of policy formation and, in particular, highlight some of the existing frameworks and approaches that ‘Greener Service Principles’ would need to fit in with. These insights led to the reframing of the principle relating to policy design, and the same could be said for the principles relating to data architecture and software development.

Figure 8. Image taken from ‘Greener Services Hack Day’.

Finding official endorsement in Defra and moving towards a set of standards

In the summer of 2023, the Greener Service Principles gained recognition and support from Defra’s Digital Sustainability team, who are responsible for policy on digital sustainability across government and the UK public sector. From that point, the principles have been championed by the team and Defra’s Chief Digital & Information Officer and have found their place in a rapidly evolving landscape of cross-departmental collaboration on digital sustainability. This includes working with groups looking at ICT procurement, developing training materials and best practice approaches for measuring the environmental impacts of digital services.

There is now the intention to evolve the principles once more in order to ready them for publication as an official set of standards that public sector digital delivery teams would be required to consider. To that end, a formal review from communities of different disciplines across various government departments and the grouping of suppliers in the ‘Government Digital Sustainability Alliance’[footnote 19] directed by Defra is now being organised.

The Greener Service Principles will help Government to design and deliver services that will be more lightweight, efficient with data capture and storage, and will reuse software and extend the life of hardware where possible. The win will not just be for environmental sustainability but also will co-benefit in terms of financial cost, usability, inclusivity and reliability.

Find out more about the project here:

Latest iteration of the Greener Service Principles, September 2024

Short film about the Greener Services Hack Day, March 2024

Improving the delivery of policy outcomes through user-centred grant decision-making (Ministry for Housing, Communities and Local Government)

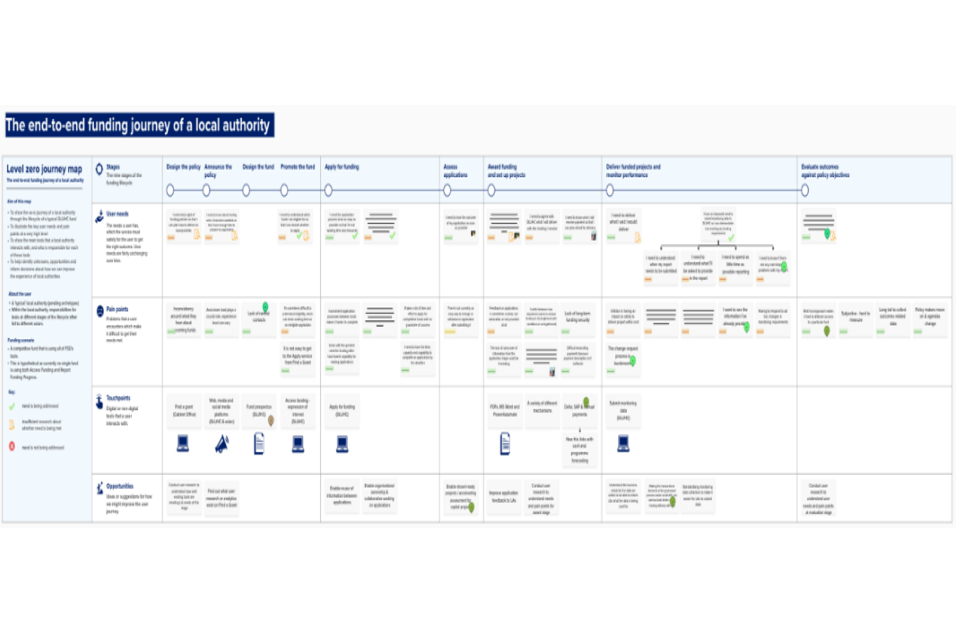

Previous approaches to designing and delivering grants had created a complex funding landscape

The Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG, previously known as the Department for Levelling Up, Communities and Housing) is responsible for delivering billions of pounds worth of funding to address affordable housing and empower communities and local government.[footnote 20] There are over 100 different grant schemes in MHCLG that support the department’s work.

The volume and variety of the different grant schemes, and inconsistent approaches to designing and delivering them, had led to a complex funding landscape. This was impacting a range of users (including Local Authority teams responsible for placing bids and MHCLG teams responsible for assessing applications and evaluating grant delivery) who had to navigate many different tools and processes to access and deliver grants. This created inefficiencies and a negative user experience.

Designing a single funding service to meet a range of user needs

In 2020, a team was set up to:

- Map how grants are designed and delivered in the department.

- Identify the different users involved at each stage of funding.

- Understand the users’ needs and pain points.

The team found that there are common steps in the design and delivery of grants, from announcing the policy, through to evaluating outcomes against policy objectives. Users wanted less complexity and more consistency in processes and tools across different grants. Following these findings, a service team was established to design and build a single, user-centred, funding service for the department.

In July 2023, the ‘Simplifying the funding landscape for local authorities’[footnote 21] paper announced that – amongst many other measures – MHCLG had built an improved digital funding service to reduce the administrative burden for organisations accessing departmental funding. The service did this by streamlining the process for submitting data and information to government. Associated aims were to support future onboarding of grants to the digital service and facilitate consistent, good quality, data to support decision making and policy objectives.

Early work on this new service focused on application forms: using question protocol workshops to establish essential user needs and standardise application questions for use across grants.[footnote 22] Additionally, content design was applied to MHCLG prospectuses: which provide detailed guidance about grants such as eligibility and assessment criteria. Taking a user-centred design approach made this information more accessible to users.

Design teams also conducted research with grant recipients to understand their experiences of applying, receiving and reporting on funding. Our researchers used various methods, including surveys, workshops, and video interviews.

Local authority user needs and pain points were mapped as an end-to-end journey to help bring together an understanding of service users and identify opportunities to improve how grants were delivered (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Detailed map showing the end-to-end funding journey of a local authority.

Through research with MHCLG grant teams, we also identified the need for a more consistent way of assessing grant applications and reporting on funding delivery. Initially we conducted a one-week data standards design sprint to define the problem and agree how to develop a clear set of consistent data standards. Following this, a team was set up to progress the development and implementation of the standards.

Outcomes from taking a user-centred approach to the design of the funding service

The service was initially rolled out to a small number of grants which has grown over time. The aim is for the service to work for all grants delivered by MHCLG, with the longer-term potential to expand to all government grants for local authorities.

Our research has found that the service has improved the experience of both internal and external users. This is evaluated in several ways, one of which is through a user experience feedback survey. The applicant survey measures include:

- Time taken to apply.

- Satisfaction.

- Understanding of questions and eligibility criteria.

The service has reduced the time taken to internally launch and deliver grants. The use of standardised terminology and questions has helped to speed up the launch process. The service has also led to quicker assessment decisions because of improved system usability and better access to structured data.

In addition, work to improve prospectuses has improved the experience of funding applicants and minimises the need for them to source additional support for their application. In one example, 2,000 words were cut from a prospectus that was 3,618 words long.

Many people responsible for designing and delivering grants in MHCLG have been involved in the co-design of this new service, which has given them an understanding of the process of user-centred design and its value. Early work on content design demonstrated the benefits of using design practises, which paved the way for these practises to be used to support policy development. This has led to more partnership-working in the early stages of grant policy design and strategy. It has also encouraged policy colleagues to view individual grants as operating together as part of an overall holistic service, and has created space to support thinking about the future of MHCLG’s approach to funding. For example, user research into allocative funding provided colleagues with a bottom-up, human-centred frame to surface questions about future policy objectives.

More than the design of individual products and solutions, the user centred approach to MHCLG grants has led to a culture shift that has contributed to longer-term thinking in the department. A holistic view of grants has prompted holistic ways of working.

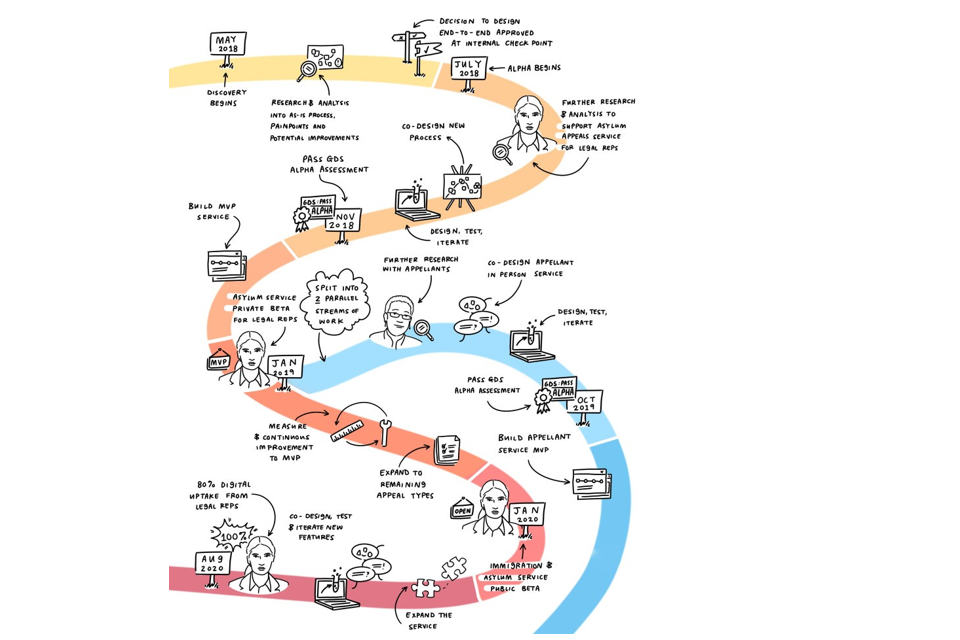

Re-designing the immigration and asylum appeals services (Transform and HM Courts and Tribunals Service)

People migrating to the UK can apply for a ‘right to enter’ or ‘right to remain’ based on their socio-economic circumstances, or their rights under the Refugee Convention or Human Right Act. In the financial year 2024/25 over 79,000 people raised an appeal to the Immigration and Asylum Tribunal when their applications were rejected. In 2018, His Majesty’s Courts and Tribunals Service (HMCTS) kicked off their reform of the Tribunal and appointed Transform,[footnote 23] a design, technology and data consultancy, to take on the work: from problem scoping and discovery phases through to the development of live services.

Asylum appellants often have lower social capital, low digital literacy, and little trust in government. Research showed appellants were struggling to promote their appeal argument and understand how their appeal was progressing. This meant that people often missed the 14-day deadline to appeal, did not provide enough information to support their appeal, or submitted such volumes of information that it could not be effectively used in the appeal process.

Research also demonstrated that the paper-based system was inefficient for administrators and judges involved in the process, who struggled to identify or easily access the most important information.

In 2018 almost 50 percent of all appeals at final hearing were decided in favour of the appellant. This meant that with the right information in place, 50 percent should never have had to go through the appeal process, which can be stressful and emotionally challenging for appellants.

Transformative service design: developing a joined-up service

The project aimed to improve the right to remain applications and appeals process by re-imagining access to justice from the perspectives of people seeking immigration and asylum. This involved developing replacements for legacy systems with one joined-up efficient digital service.

Discovery work involved assessing a complex backdrop of UK legislation, judicial rules, and legacy ways of working. Desk-based research helped us understand our service landscape, identify constraints and innovation boundaries.

Having mapped our stakeholders, we mapped the as-is, analysed performance metrics to zoom in on internal processes (e.g. appeal validation; appeal fee payment), and identified operational pinch points.

To examine these pinch points in more detail and fully understand our design challenges, we used one-to-one structured interviews and journey mapping with judges, operations officers, and caseworkers. Solicitors, charitable bodies, and appellants helped us build key insights. These fed into a holistic service blueprint and user summaries for our most sensitive and knotty journey – appeals for asylum seekers, putting the people who were most excluded at the centre of the work.

Figure 10. Visual timeline showing the different phases of work involved in the redesign of the immigration and asylum appeals service.

The team carried out a total re-design of a new end-to-end service, to avoid the limitations of only redesigning or digitising vertical slices of the user journey. The team used a range of participatory, human-centred design approaches. Ways of working included:

- Co-design sessions facilitating stakeholders (judges, operational staff, managers & policy makers, Home Office (HO) staff and stakeholders, and third sector organisations) playing the roles of researchers and designers - building empathy across the ecosystem, learning one another’s day-to-day responsibilities, insights, ideas and pain points, assumptions, concerns, and policy goals.

- Collaborative as-is service mapping – groups mapping their end-to-end service, policy interdependencies and pain points.

- Participatory research synthesis – using visually rich and comprehensive stories to examine user and system needs close up and make sense of findings together.

- Future-state co-design – stakeholders using their own ideas alongside prepared ideas synthesised from previous sessions, to map the future service including tasks, channels, future-metrics, technical requirements, and data transactions.

- Role and responsibility mapping with judges, local caseworkers, and service managers helped judges quickly spot administrative tasks they felt could be devolved to caseworkers, who in-the-moment acknowledged their confidence in taking on the tasks. Service managers approved of the operational changes, freeing up judges’ time to be applied to more complex, highly qualified tasks.

- Service simulations gathered all key service stakeholders to test the whole service in a single day. Participants completed forms and responded to task notifications end-to-end along the service cycle, moving from one actor to the next. These generated insights that would be missed if we had only tested slices of the service, journey by journey. These agile, design-thinking sessions often hosted key decisions between senior leaders, negating the need for additional meetings which would eat into tight timelines and further burden time-poor stakeholders.

“Next time we have a problem to solve I will reach for sticky notes, sharpies and stick our ideas where everyone can see them” – Resident Judge.

- Pair-writing between content designers and judges enabled content designers to: 1) guide and support judges to translate complex legal text into modern-day plain English; 2) support judges to understand and feel comfortable with the value of taking an iterative approach to design. As a result, appeal application forms have significantly reduced in size, from 128 to 36 data fields for legal representatives and from 128 to 10 for appellants without legal representation.

- User experience and interface prototyping. The project team were tasked to see if existing case management user interfaces designed for solicitors could be reused for appellants without legal representation. Usability testing demonstrated that appellants struggled to navigate the tabbed, interface design. Testing also showed existing experimental GOV.UK patterns, including timelines, didn’t offer the right level of detail when describing historic actions or next steps to be taken. Designers tested and iterated page layouts (e.g. use of colour, content/page architecture, in-line guidance) modifying GOV.UK patterns into a bespoke, vertical, chronological view of tasks completed and next steps. The interface was designed to support a reading age of 5-9, allowing appellants to complete their tasks unaided, enhancing their access to justice – our primary policy goal.

Reducing administrative burden through accessible design

Now live, the service experiences a digital uptake rate of over 95 per cent across appellant types and, most importantly, around a quarter[footnote 24] of all appeals are resolved well before a hearing is required. As a result, work can be devolved to administrators and case workers: judges have more time to attribute to the most complex cases, and costly judicial time is saved on cases that can be easily resolved.

The new digital service provides people with the ability to self-serve and have more ownership of the information they have provided. This means they can re-use this ordered, easy-to-read account of their asylum or immigration case, instead of having to tell their story over and over again. This also benefits administrators and judges who have easier access to information digitally. Using the single view of all required tasks, the appellant can also see where they are in the process, meaning it is less likely they will miss tasks, and reducing the stress caused by an unclear journey.

“…The benefits are clear. It’s a model for how you should do things – a really well run and executed project.” Director of Tribunals.

Find out more about the project here:

Modernising courts and tribunals: benefits of digital services

Reducing spiking offences and increasing prosecutions (Home Office)

The Home Office Policy and Innovation Lab is a team of designers and researchers who work with policy and operational colleagues to solve complex problems through design approaches.

In Spring 2022, the team was commissioned by the Public Protection Unit to help respond to emerging reports of a new form of spiking. This was related to the emergence of reports in Autumn 2021 of people being surreptitiously injected by needle with unknown substances whilst out in pubs and nightclubs. 1,382 cases were recorded from September 2021–January 2022, most of which occurred in October 2021. The sudden increase in this new form of spiking was alarming and attracted widespread media coverage, leading to calls for a new criminal offence for spiking.

Before determining which solutions might be appropriate, the team started by identifying what outcomes a government response might look to achieve. These were quickly identified as reducing spiking incidents (across both needle and drink spiking) and increasing prosecutions. With these established, work could then start into understanding the spiking landscape and finding out what might need to change to achieve these outcomes.

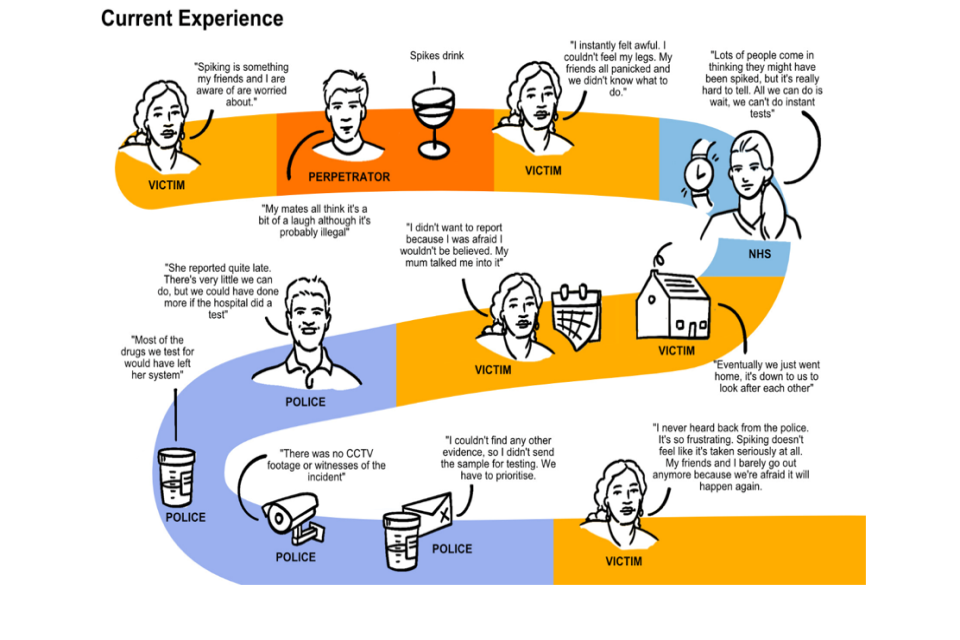

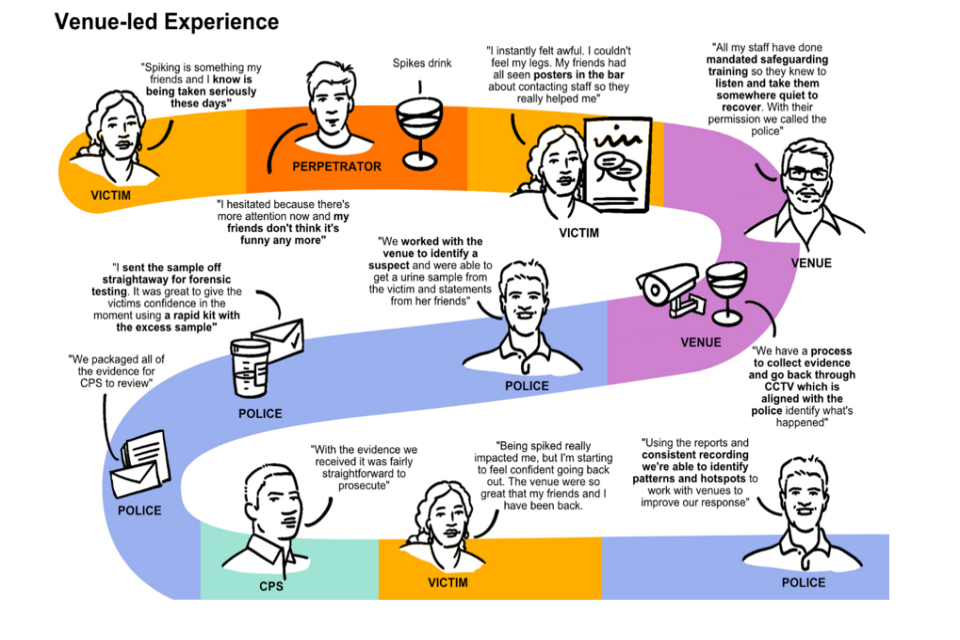

Using existing evidence, an initial journey map was created of a spiking victims end-to-end experience (Figure 11). This helped inform an initial ecosystem map, which was then further expanded with the policy team to capture the full breadth of sectors and stakeholders involved across the course of a spiking incident.

Figure 11. Journey map showing the current end-to-end experience of a spiking victim.

Over 12 weeks, 74 semi-structured interviews were held with professionals from across the ecosystem (covering 9 different sectors), as well as with spiking victims and members of the public. Each person provided a different perspective on what was working well and where things needed to be improved. Layering these together then identified the common pain points and opportunities for improvement.

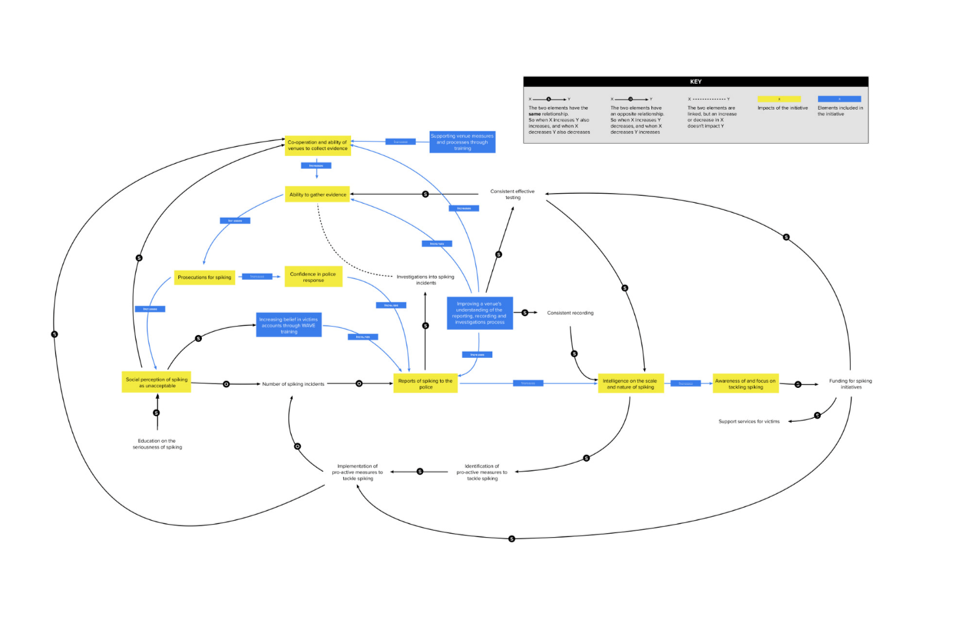

The research found that the primary barriers to prosecution were the lack of an identifiable suspect and the gathering of sufficient evidence to both charge and support a prosecution (Figure 12). Interventions therefore needed to focus on these areas to increase prosecutions. Team ideation sessions helped identify possible interventions. For example, venue staff could be trained to better recognise and quickly respond to spiking incidents, so that they could gather crucial evidence before it became contaminated or lost.

Figure 12. Challenges around suspect identification and gathering of sufficient evidence.

Figure 13. Ideal journey showing the how the victims experience could be improved at each stage.

An ideal journey was mapped out, which helped articulate how the victims experience could be improved at each stage (Figure 13). System mapping was also used to get a better understanding of the interconnectivity of factors (Figure 14). Ideas were then mapped onto this, to help identify which interventions might have more impact.

Figure 14. Systems map showing the impact of venue training.

Whilst there were clear opportunities for how victim support could be improved and numbers of prosecutions might be increased, preventing incidents from occurring was more challenging. It became clear that a cultural shift was needed to change perceptions of spiking. The research found that several offences already existed that covered incidents of spiking and there was no gap in the law. However, it also concluded that a new offence could increase public awareness of spiking, which could change cultural perceptions. This might also encourage more people to report spiking incidents and make it easier to get a true data picture of spiking.

Bringing a design approach to this problem has been highly valued by policy colleagues because it has provided them with a robust and holistic perspective from which to make policy recommendations.

“As someone new to this policy area and taking forward a new Government’s agenda on spiking, it has been absolutely invaluable to have such a comprehensive, well-rounded and objective piece of research to help inform evidence-based policymaking.”

“This report is a testament to the in-depth research undertaken by the team, combined with the clear, reasoned and compelling recommendations which continue to form a fundamental part of our approach; even after two years and a change in Government.”

Final recommendations were presented back to policy colleagues, and were subsequently shared with Number 10, the Home Affairs Select Committee, and broader parliament. As a result of this work, a number of system-wide measures were announced in December 2023. These included:

- Providing government funding for the development and delivery of spiking training for staff in the nighttime economy to encourage prevention and detection of spiking incidents, as well as more effective evidence-gathering. This training, provided by Red Snapper Learning, is now live and available for sign up by nighttime economy venues.

- Government funding for intensive operations run by the National Police Chiefs Council (NPCC) to tackle spiking during key weeks in England and Wales. Funding was provided to a select number of forces - though all forces were expected to carry out additional activity on spiking during the intensification weeks. The first happened in March 2024, the second in September 2024 to coincide with University ‘Freshers Weeks’.

- The rollout of a police spiking reporting and advice tool to encourage more and better reporting, including anonymously. This is available in England and Wales via police.uk.

- The regulator of the UK private security industry, the Security Industry Authority (SIA) developing mandatory spiking training for their Door Supervisor licence holders who work in licensed venues throughout the UK. The SIA plan to have all 354,000+ door supervisor licence holders trained on spiking by April 2028, with existing licence holders receiving this training on renewal (every 3 years) from April 2025.

- Updated statutory guidance (“Licensing Act 2003 (section 182)”) to ensure that licensed premises give due regard to preventing spiking in their venues.

- Providing funding for research into rapid spiking testing kits for urine, to help venues and police detect if someone has been spiked in real-time.

- Spiking information and support pages on GOV.UK containing a range of resources and signposting for anyone who is looking for information on spiking.

Following the 2024 General Election, the Government committed to introducing a new criminal offence for spiking to help police better respond to this crime. This was introduced as part of the Crime and Policing Bill in February 2025 and can be found on parliament.uk.

Regenerating a seaside community (The Design Council and Northumberland County Council)

Northumberland County Council used design coaching to help regenerate a landmark industrial site and create a new community asset.

The closure of a frozen food factory in the Northumberland town of Amble had a heavy impact on the local population. Northumberland Foods, Amble’s largest employer, closed its doors in 2010 triggering the loss of 250 jobs and leaving a gaping hole where a landmark industrial site once stood. Northumberland County Council, the owner of the factory site, wanted to ensure what replaced it continued to be of value and have a positive impact on the community as a whole. The question was how.

Northumberland Council began by approaching Amble Development Trust to help them put together a group of local stakeholders to work together to determine a future use for the site. Amble is a historic port with a population of 6,000, situated on the River Coquet estuary and the southern gateway to Northumberland’s Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Coastline. An immediate challenge was to understand how a service model, for the type of enterprises that could be based on the old factory site, might be designed and developed. Determined to ensure that all involved could equally contribute and co-create a model that would benefit the local community, the council asked the Design Council for support.

What We Did

Northumberland Council and Amble Development Trust started working with the Design Council Design Associate Nick Devitt, who began by bringing together representatives from key stakeholder groups. “At the start of this process, there was a 20-page development document outlining a vision to regenerate Amble but no methodology for achieving it,” says Devitt. “An essential first step was to get all of the key stakeholders together, around the same table and talking.”

“The challenge was having an open discussion - and that’s where working with an independent Design Associate really becomes very valuable.”

Julia Aston, Amble Development Trust

Nick then led a series of workshops designed to unite the diverse mix of representatives from organisations, including local businesses, the local tourist board and the police, using a design-led approach to generate and capture ideas around which the group could coalesce and begin to shape an approach. The aim was to gain “a vision for the future of Amble”, says Julia Aston, Director of the Amble Development Trust. “Some people came with a fixed approach, others not. The challenge was having an open discussion – and that’s where working with an independent Design Associate really becomes very valuable,” she adds.

Initially, the focus was on the challenges the town faced and different ways the industrial plot could be used. One idea was to turn the factory site into a Made In Northumberland Food Hub. However, it soon became apparent that a bigger issue was what more could be done to reinvigorate the fortunes of the entire town. Food emerged as a recurring theme – especially seafood. While Amble is a busy fishing port, almost none of its local catch was being sold locally. Tourism was identified as one of the most important sectors for the town’s economy for which locally caught food would be a big draw.

“What was clear was that the project needed not be tied to just one site – the old factory – but do something for elsewhere in the town in a more sustainable way”

Julia Aston, Amble Development Trust

Workshop participants identified redevelopment goals and also challenges and barriers that would need to be addressed. Thirteen project ideas were identified, including an opportunity to improve signage around the town to make it easier to access and navigate, a promotional strategy to boost visitors including the creation of a seafood festival, piloting local mussel production, and turning the old factory site into an ‘urban campsite’. A regeneration project which focused on the heart of the town around the harbour and sought to re-position Amble as a food-centred tourist destination was favoured. The tourist consultancy team[footnote 25], was then appointed to undertake a detailed scoping study. “What was clear was that the project needed not be tied to just one site – the old factory – but do something for elsewhere in the town in a more sustainable way,” says Aston. A key idea was to create small retail units – pods – for small, local producers and a local seafood centre. Nick also advised on the user benefits and potential business model of such a scheme and best locations for the proposed retail pods were assessed.

In 2012, local stakeholders co-published a report called ‘Amble 2020’, outlining ambitious plans to boost the economic fortunes of the town by revitalising the town’s harbour, waterfront and pier to attract new visitors, create jobs and help to sustain the wider economy of the local area. Proposals included developing an aqua-cultural growth sector and a new harbour village with 15 new small business pods, a seafood centre, a new waterside promenade, and the establishment of a seafood broker post to add value to the catch landed by the local fishing fleet.

Results

Design Council support at an early stage of the project to regenerate Amble was an important contributor to its success. Meanwhile, many of the development ideas it generated, co-created by community stakeholders under the guidance of Nick, have since been implemented. In March 2014, Amble secured £1.8 million funding from the Government’s Coast Community Fund. The first 12 retail pods opened the following March, and the final three pods and the seafood centre opened for business in July 2015. “The extent to which discussions evolved and how the project went off in [a] broader and more sustainable direction than initially suggested is a positive reflection of our Design Associate’s open-minded and flexible approach”, Aston explained.

In 2015 Amble won the High Street of the Year award (Coastal Community Category) and in 2019 it was listed in the Sunday Times as one of the top places to live by the sea. In 2020, more than £8 million has been invested in Amble’s regeneration with a further £10 million earmarked for future projects.

Find out more about the project here:

Northumberland County Council: Regenerating a community asset

What’s design got to do with the price of fish? Everything (YouTube video)

Design Council 2020-24 Strategy Report (page 15)

Northumberland Seafood, community hatchery in Amble - Power to Change

Reimagining education services from the perspective of frontline workers (Department for Education)

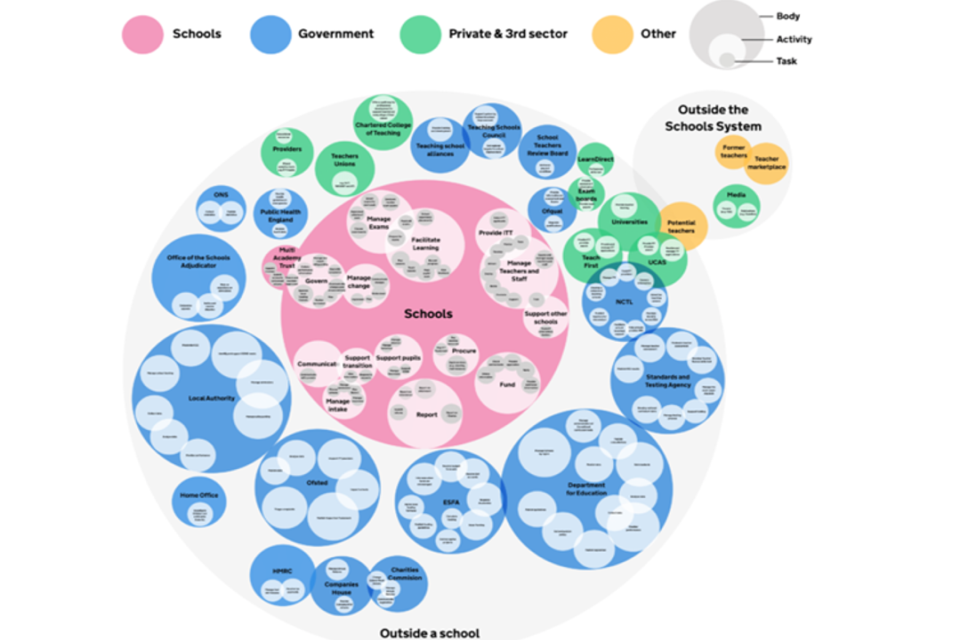

In 2017, the Department for Education (DfE) launched a fresh, systems-thinking based review and re-imagination of what education services might look like if they were designed using the perspective of frontline workers such as teachers. It was led by a multidisciplinary team of policy experts and technical experts like researchers, analysts, designers and delivery experts.

The policy design team found that policymakers were doing their very best to provide education services that focused on the delivery of government priorities and were generally good at making their services as efficient as possible. But policymakers were frustrated, surprised and disappointed when initiatives had poor take-up.

Understanding the problem

The policy design team worked with teachers to understand the system from their perspective. What this revealed was a knotty mess of publicly funded services, information and obligations from central government, local government, public bodies, charities and commercial organisations, all competing for teachers’ attention (Figure 15). Overlaying this challenge were unrelenting ‘waves’ of change that hit schools. One former teacher described it as “like being on a beach, being hit by a big wave and before you can get up to take a breath, another big wave hits”. Teachers are at the eye of a storm where they must prioritise who to listen and respond to because they have limited capacity.

Figure 15. Systems map showing the different bodies, activities and tasks within and outside the school system.

DfE decided to prioritise the re-design of services that support the recruitment and retention of teachers in the profession. This was a priority area for teachers, and public anxiety about the supply of teachers featured regularly in the press.

The workforce recruitment system, with its multiple entry points and different training initiatives, was extremely difficult to navigate for people who wanted to become a teacher. Many found the application process onerous and off-putting. Prior to 2017, over a quarter of a million people visited the information website for teaching careers every month, but 50 percent of people dropped out between registering their interest and applying for a course.

“I had to jump through lots of hoops to get into teacher training”

School Direct trainee.

The Government was spending £700 million annually with a view to training 35,000 teachers each year but had failed to meet its own target every year for five years.

The policy design team also found that moving qualified teachers around the education system had become a huge business for recruitment agencies. Without a reliable, recognised marketplace for teachers to move between jobs, schools were relying on recruitment agencies to navigate a complex market and were spending about £75 million annually to advertise teaching roles.

Mapping how different components of the service relate to each other

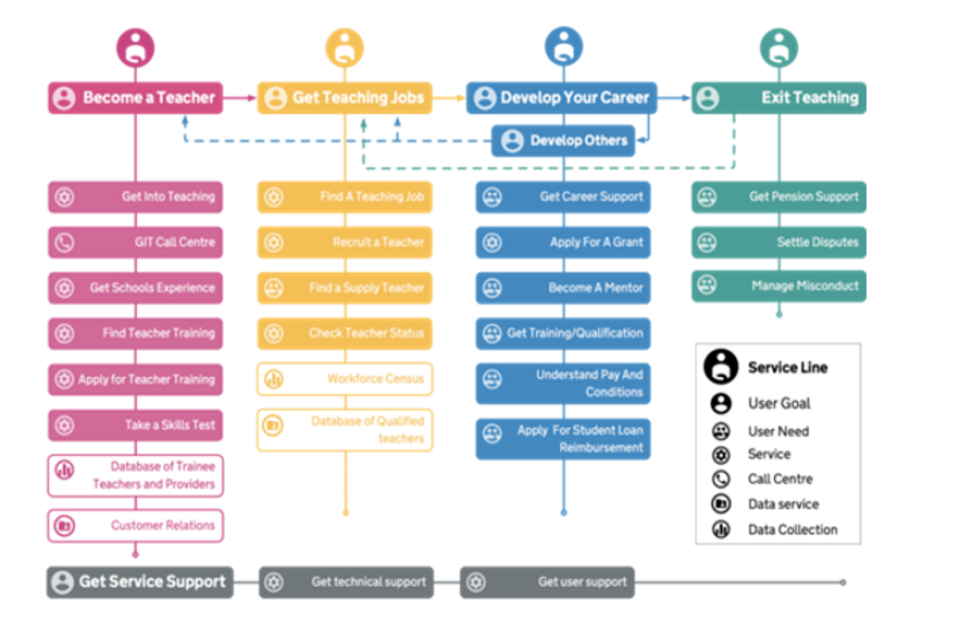

The policy design team conducted an exercise envisioning how services for teachers might look if they were designed by teachers. They mapped out all relevant publicly funded services and made an assessment of how valuable they were to teachers and government. They then reorganised the services in a way that would make sense to a teacher as they progress through their career.

Each headline service broke down into a number of service parts. Legacy activity, policy and services within the system was mapped and then re-designed into a streamlined order that the end user of the service (teachers) would recognise. Each of the policy or service parts (shown in Figure 16) were then prioritised for investment.

Figure 16. Map showing each service broken down into its component parts.

Overhauling teacher recruitment

One of the outputs of this exercise was a programme to radically improve the end-to-end journey for those seeking to become a teacher. The team replaced a complex journey split across three organisations and instead created a joined-up service, designed to inspire, attract and support potential teachers.

Previously, the journey into teaching was fractured across different organisations, and information didn’t flow freely between the different services that candidates and providers used. For example, candidates could register an interest in teaching on a DfE marketing website, before applying through the Universities and Colleges Admissions Service (UCAS), with information candidates and providers inputted at each stage not linking up. Equally, information submitted as part of the candidate registration process was regularly duplicated elsewhere in the journey, creating additional administrative burdens. Candidates were also not being signposted to the most relevant information to support them on their journey.

The new service has changed this. Now, information flows much more smoothly between stakeholders, and information provided in certain parts of the system is automatically used to populate other parts of the system. Candidates also get bespoke guidance at each stage of their journey, dependent on their experience and progress through the system.

During their pilot, the team saw a reduction in the number of people dropping out of the journey, with the potential for 600 extra trainees to successfully enter the teaching profession each year.

The new service is also providing rich data. Teams now have access to information on which candidates are being accepted onto teacher training courses by which providers. This allows them to continually analyse the service, identify problems and deliver improvements.

They can also be smarter about where they invest money and time. Previously, marketing teams were unaware of who had already applied for teacher training as this information sat with a third-party, UCAS. This meant that they would send marketing materials to candidates who had already applied for teaching, something that was both annoying for candidates and wasted money for the department. The new, real-time data now support more targeted and effective communications.

“It is so much more user-friendly than UCAS. The interface is clear and intuitive, the email notifications give us just the right amount of information and the applications are much clearer and more useful”

Provider feedback

A new model for scaling innovation

A milestone was marked in 2021 for teacher services because DfE -brought the final external part of the service in-house. Looking back, we really knew this innovative approach was working when DfE teams began to restructure themselves to reflect the teacher service lines. They let go of the idea that ‘policy’ and ‘delivery’ are separate things and created multidisciplinary teams with singular ownership of each problem and service: from concept, to implementation, to continuous improvement. This allowed the policy and delivery to iterate and evolve as the teams learnt more about the people that use their services and how the system worked for them.

DfE previously had a history of years of failed innovations in the teaching workforce space. Its ‘let a thousand flowers bloom’ model had produced a lot of failed public services, and in an already highly pressurised environment, this contributed to teachers feeling overwhelmed and undervalued. By taking a systems-thinking approach and bringing policy and delivery into single teams, DfE was able to see challenges from the perspective of service users and develop a systems map as a framework for future policy design innovation. Considering each innovation in the context of how it relates to other parts of the system allows innovations to become more than the sum of their parts.

This case study is also published on the Public Policy Design Blog[footnote 26].

Supporting unpaid carers to remain in work (Department for Work and Pensions)

Background

In 2017, DWP’s Human-Centred Design Science (or DWP Behavioural Science as it was then called) and carers employment policy teams sought to understand why unpaid carers leave employment and whether there was more government could do to prevent this.

Recognising this challenge cuts across the remit of multiple departments in central government, we invited colleagues from the Departments of Health (as it was then), Business, Government Equalities Office and Treasury to a workshop to map respective departmental objectives around unpaid carers to explore any tensions or trade-offs. We then used detailed, evidence-based personas to consider citizen experiences and support needs from the point that care needs first emerge onwards. Collectively, we mapped the journeys that each persona ‘should’ take in light of the then landscape of policies, services and entitlements (in other words – the ‘ideal’ journey at that time). We then considered the journey that each persona would be likely to take in reality, bearing in mind the range of barriers they faced, including a lack of time, a lack of energy, and limited knowledge of what can feel like a confusing and fragmented system of services and support.

This exercise highlighted that families might well have significant unmet needs during the earliest days and weeks after care needs emerge, when many highly consequential decisions are being made, often under great pressure and without much support. This led to a hypothesis: Under-informed decision-making early in people’s caring journeys contributes to people feeling forced to leave work to care later on.

Problem definition: exploring our hypothesis

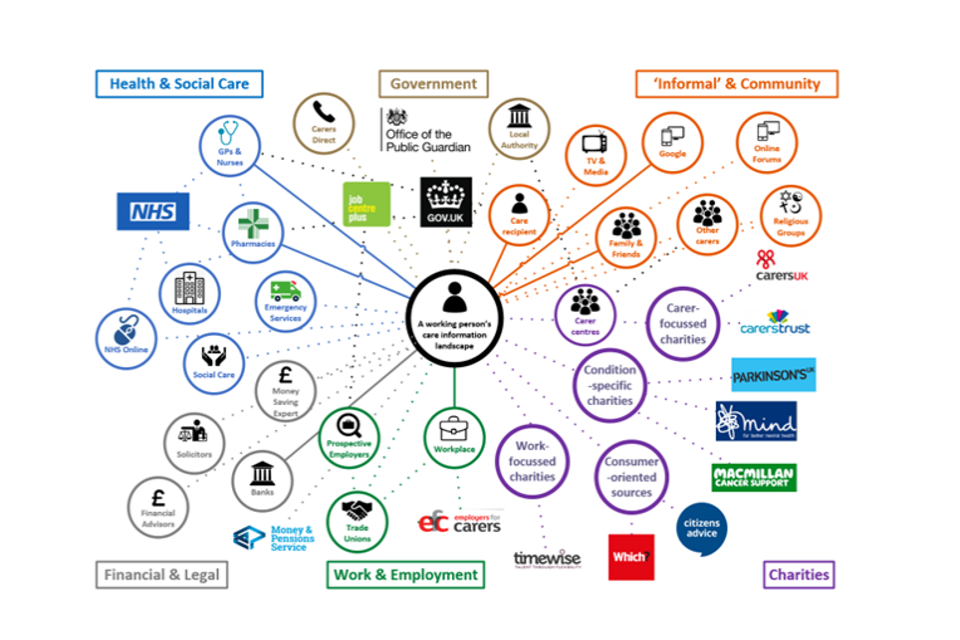

A cross-departmental, jointly funded ‘discovery project’ was established to test and explore our hypothesis. We built a community of around45 experts and organisations across government, charities, academia and the private sector, as well as unpaid carers themselves, and co-designed research with working people at different stages of caring. Not only was it vital to gain multiple perspectives on this complex and emotive challenge, but we also recognised the vast range of information touchpoints that influence care choices, and that many of these were not owned by Government.

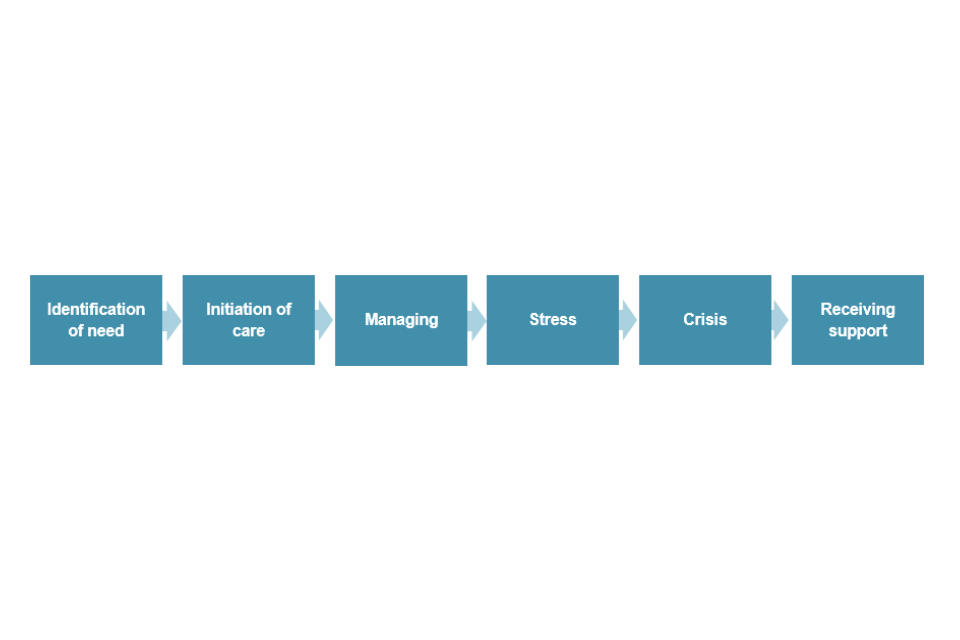

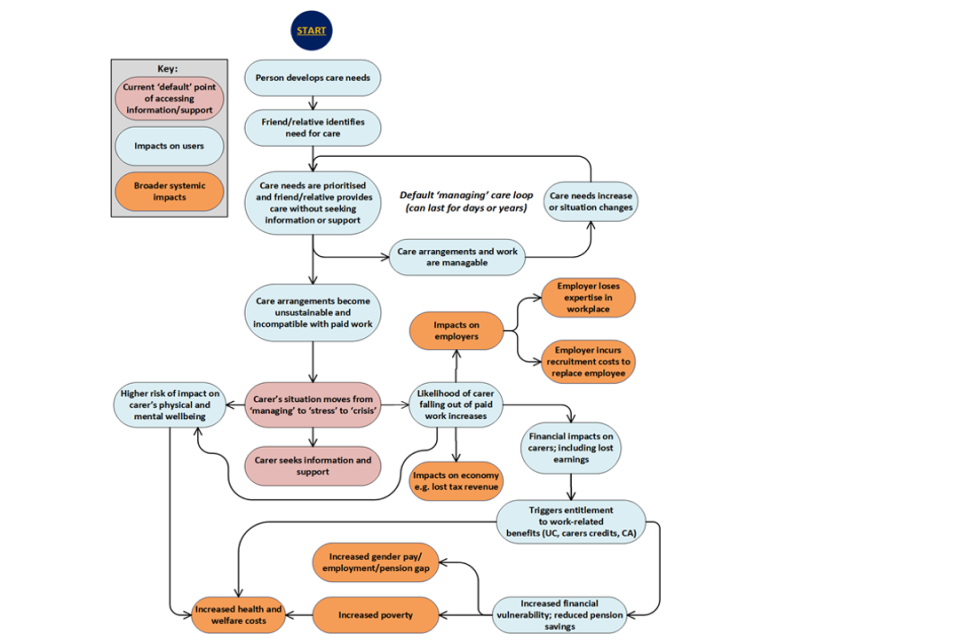

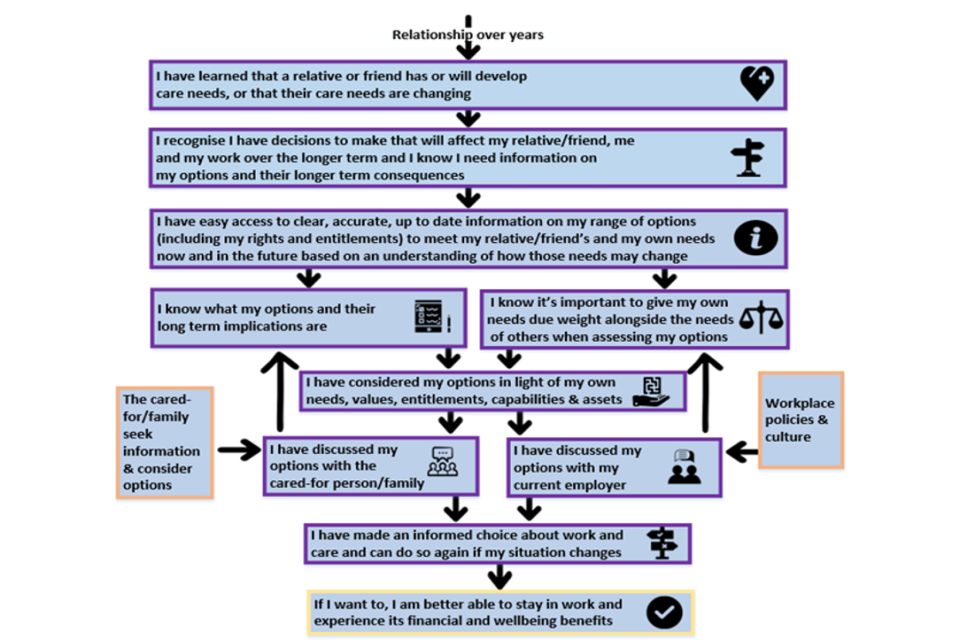

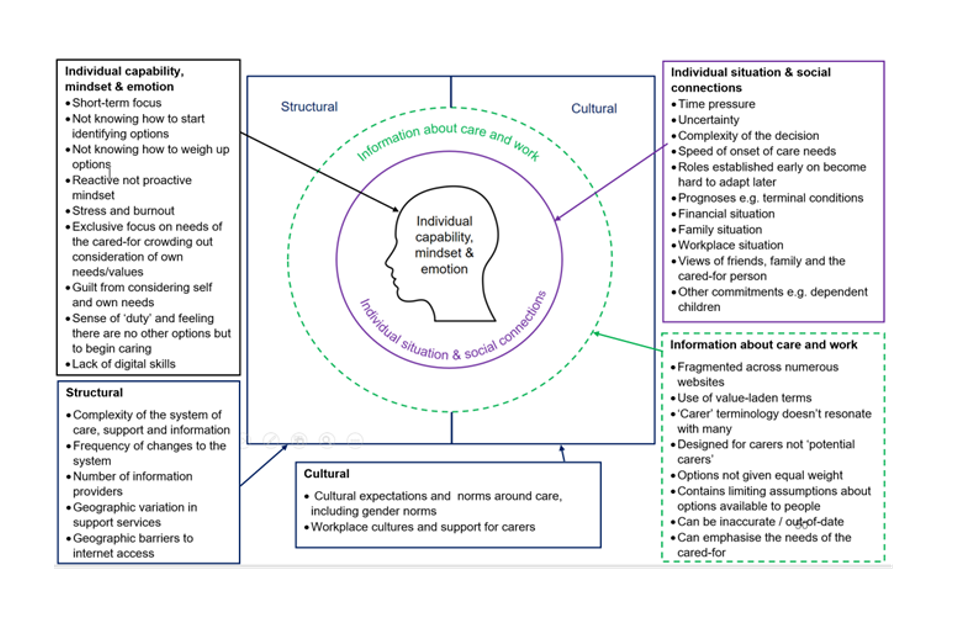

Throughout this collaboration we regularly shared, tested and iterated our developing understanding of caring experiences and the systems they navigate. We shared information verbally and in writing, but also – crucially – through diagrams and visuals. These visuals (Figures 17-21) helped to make complex concepts clear, overcome differences in the way people and organisations used language, and focused our conversations and thinking.

Research with carers

Qualitative research conducted for us by Ipsos MORI revealed a ‘default journey’ with carers reporting feeling that they had no option but to take on unpaid care. People experienced pressure to make early decisions hastily without understanding how care needs might evolve, or considering the possible long-term consequences for their wellbeing, relationships, finances or employment. Early on, people didn’t see themselves as ‘carers’ or seek information or support. When carers did access information and support, it was often only after a point of crisis when the opportunity to remain in work had already passed.

Figure 17. The ‘default’ caring journey.

- Identification of need

- Initiation of care

- Managing

- Stress

- Crisis

- Receiving support

Linking individual decisions to societal impacts

We produced a causal sequence and impact map (Figure 18) illustrating how the default journey connected to key societal-level impacts that organisations in our community valued, enabling collective scrutiny and challenge.

Figure 18. Default caring journey impact sequence map.

Defining informed decision-making for our target users

We collaboratively developed a detailed set of information needs for a previously under-recognised and un-named group: ‘potential carers’ (i.e. working people facing decisions about work and care). The distinction between ‘potential carers’ and ‘carers’ highlighted the gap in thinking across organisations in the system.