Public Design Evidence Review: Literature Review Paper 2 - Public Value (HTML)

Updated 21 August 2025

Commissioned by the Policy Design Community

Authors:

Rainer Kattel, Deputy Director and Professor of Innovation and Governance, Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose, University College London

Iacopo Gronchi, Doctoral Candidate, Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose, University College London

How to cite:

Cabinet Office (2025) Public Design Evidence Review: Literature Review Paper 2 – Public Value.

Background

This document is the second of three literature reviews commissioned by the cross-government Policy Design Community, written by an interdisciplinary team of academics. It discusses the concept of public value, its origins, measurement, and application in public administration, emphasising the need for professionalisation to enhance public value delivery.

The wider project was commissioned as a non-exhaustive exploration of the relationship between public design and public value. It was conducted within rapid timeframes and prioritised cross-disciplinary working. The authors began drafting in September 2023, finalised the drafts in March 2024, and published in July 2025.

‘Literature Review Paper 1 - Public Design’[footnote 1] and ‘Literature Review Paper 3 - Public Design and Public Value’[footnote 2] are published alongside ‘Literature Review Paper 2 - ‘Public Value’ as part of the Public Design Evidence Review.

Summary

At its core, public value can be defined both as an outcome and as a process. As an outcome, it can be defined as the achievement of broad and widely accepted societal goals – also, but not exclusively, through the delivery of public goods and services. As a process, it can be defined as the creation of an effective alignment between the ‘mission’ of a given public sector organisation (i.e. its priorities); its ‘authorising environment’ (i.e. its sources of legitimacy); and its ‘operational capacity’ (i.e. its available resources, skills, and capabilities). In this respect, it is important to differentiate between public value and public values. A public policy might create value for the public (e.g. better infrastructure or service) or aim to influence how the public values certain activities (e.g. ban on indoor smoking). Here we are interested in the former.

According to the above, public value can be measured by means of complementary tools: on the one hand, those focused on outcome (e.g. Cost-Benefit Analysis; Cost-Effectiveness Analysis; Risk-Opportunity Analysis); on the other, those focused on process (e.g. Public Value Mapping, Accounting, and Scoreboard; or HM Treasury’s Public Value Framework). Current research does not provide a definitive answer for the question of how to measure public value creation in the public sector. While Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA) firmly sits at the core of contemporary government practice, its ability to yield effective policy analysis is increasingly put under question. As a result, the pressure that is engendered by contemporary societal challenges is feeding into new efforts to conceptualise and operationalise the notion of public value in new ways.

Such efforts come from the realisation that there is a widening gap between increasing societal challenges and governments’ ability to address citizens’ needs. In this sense, the widespread scholarly criticism towards old paradigms of public administration (New Public Management) and the rise of new ones (e.g. Neo-Weberian State, New Public Governance, Digital Era Governance) calls for a review of how the skills and routines of civil servants are evolving in order to deliver public value creation in today’s operating context. There are many features common to emerging practices in the public sector – such as a focus on external or ecosystem value creation; citizen and stakeholder engagement; and quicker feedback and learning cycles. Partially enabled or driven by profound technological changes, public organisations have responded by creating new units (e.g. policy labs) and new professions (e.g. Digital, Data and Technology Profession). Underlying both new units and professions are new skill sets that originate from both digital and public design practices. However, it is by no means clear whether such units and practices are as effective as initially thought (e.g. many policy labs remain at the edges of policy creation and delivery).

Altogether, such shifts in the way the public sector operates can be distilled into a new ethos of civil service founded on four characteristics:

- Wisdom: i.e. the capability to anticipate future changes in the policy context and reform public institutions to cater for long-term phenomena.

- Imagination: i.e. the capability to design, inspire, and motivate change in the operational routines of a public sector organisation while ensuring stability in delivery.

- Collaboration: i.e. the capability to design and develop policy in partnership with multiple stakeholders within and beyond the public sector.

- Humility: i.e. the capability to revise existing assumptions about effective policy design and delivery – primarily, through experimentation.

While civil servants’ practice provides an early indication that a new paradigm is assuming form, it is still unclear how these characteristics can be embedded into the everyday practice of civil service: i.e. how to professionalise public value delivery. Based on a review of the potential and limitations of strategies based on policy innovation labs (PILs) and three additional pathways to professionalisation (i.e. leadership, competency frameworks, and communities of practice), we propose an approach labelled ‘practice-based leadership’. This approach provides an initial hypothesis for how public management can engage its civil servants into the development of new working routines – such as public design – and their consolidation into new policy professions capable of maximising public value delivery at scale.

1. How to define public value?

1.1. Origins of Public Value theory

During the last 25 years, the notion of public value (PV) has become extremely popular among researchers and practitioners alike. Still, its meaning is heavily contested. At its simplest, value is the “relative worth, utility, or importance” of something (Merriam-Webster Dictionary, 2023). In the context of the public sector, such a notion is usually identified with a range of principles that characterise what is deemed ‘good’ public administration, such as efficiency; accountability; equity; and many more (see, e.g. Jørgensen and Bozeman, 2007). Yet, the scholarly debate around the nature and usefulness of such a concept for public management, administration, and governance is alive and kicking. This section aims to make sense of such debate by synthesising its main theoretical developments.

PV theory was born in the mid-90s at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government, where Professor Mark Moore first developed it as a strategic approach to public management (Moore, 1995). His purpose was to help public managers “achieve publicly desired social outcomes” by becoming “more focused on achieving valued results; better able to measure those results; more experimental and innovative in seeking improved performance; more responsive to changing conditions; more capable of mobilizing capacities outside of government” (Moore, 2019, p. 355). His contribution can be interpreted from at least three perspectives: first, as a philosophy of public management; second, as a tool for decision-making; third, as a set of interventions.

- As a philosophy of public management, PV theory interprets the public manager as an independent actor that is capable of “restless, value-seeking imagination” (Benington and Moore, 2011, p. 3) whose “task […] is to create value” (Moore, 1994, p. 296) and whose autonomous judgement is critical to good governance.

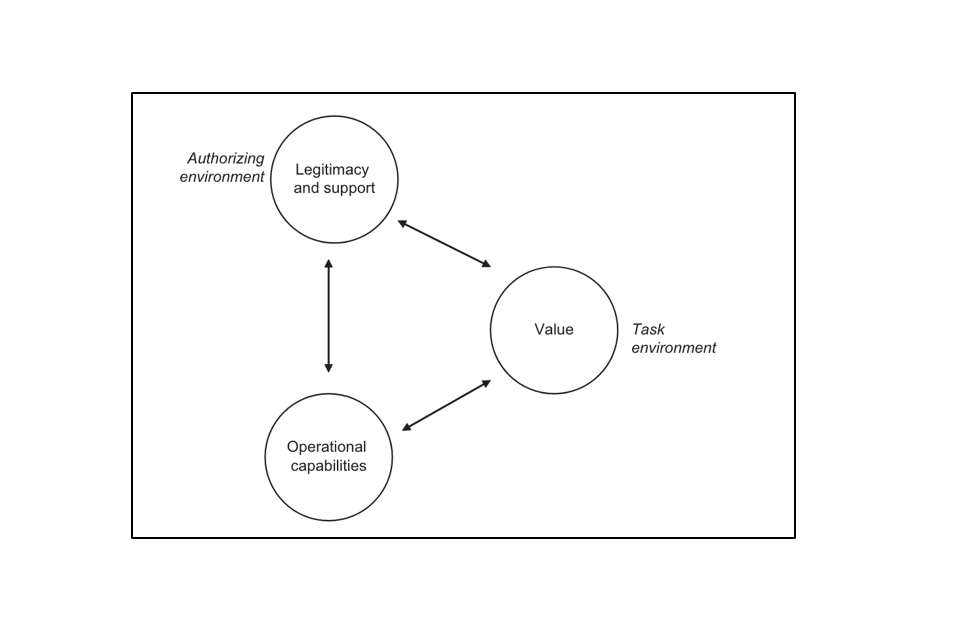

- As a tool for decision-making, PV theory is primarily crystallised into the ‘strategic triangle’ framework, which posits that any successful public management strategy is:

- aimed at creating something substantially valuable;

- legitimate and politically sustainable; and

- operationally and administratively feasible (Moore, 1995; see also Figure 1).

- As a set of interventions, PV theory is further reflected into an approach to executive education that adopts a practice- and problem-orientated pedagogy in order to help public sector managers reflect on their own working practice and nurture new approaches to organisational leadership (Moore, 2013; see also de Jong et al., 2017).

Figure 1. The strategic triangle[footnote 3]

In each of these respects, PV theory is at odds with consolidated schools of public administration – for which the autonomy of the Civil Service is seen either as a ‘value-free’ auxiliary of political decision-making (Traditional Public Administration) or as a ‘value-wasting’ source of government failure (New Public Management) (Stoker, 2006; O’Flynn, 2007). Conversely, PV theory posits that the key function of the public manager is twofold: on the one hand, to mediate among the many signals emerging from their internal (organisational) and external (societal) environment, captured by the strategic triangle framework; on the other, to develop ‘public value propositions’ that articulate “the public’s aspirations and concerns” and “the procedural norms and values associated with good public sector governance” (Alford et al., 2017, p. 590).

1.2. Developments of Public Value theory

Despite its relatively clearcut origins, the notion of PV has been interpreted in very different ways – thus opening up new debates concerning its theoretical, analytical, and practical relevance.

From a theoretical perspective, Alford and O’Flynn (2009) mapped out four meanings of PV:

- as a paradigm of public management for the ‘post-NPM[footnote 4] world’ (Stoker, 2006);

- as a rhetoric to legitimise the use of administrative discretion (Roberts, 1995);

- as a narrative to demonstrate managerial accomplishment (Smith, 2004); and

- as a framework for performance measurement in the Civil Service (Kelly, Mulgan and Muers, 2002).

The focus of these four meanings is squarely placed in Moore’s original framework – thus aiming to illuminate or orient the motives that guide public management. Still, the notion of public value has been used in other ways too.

From an analytical perspective, Bryson, Crosby and Bloomberg (2014) identified four levels at which the notion of PV can be applied:

- at the psychological level – i.e. in terms of the individuals’ subjective assessment of their relationships with society (Meynhardt, 2009);

- at the managerial level – i.e. in the meaning first proposed by Moore;

- at the policy level – i.e. in terms of policies’ ability to achieve the values enshrined into a society’s normative consensus (Bozeman, 2007); and

- at the societal level – i.e. in terms of the processes, within the ‘public sphere’, through which public values are held, created, or contrasted by a certain ‘public’ (Benington, 2009).

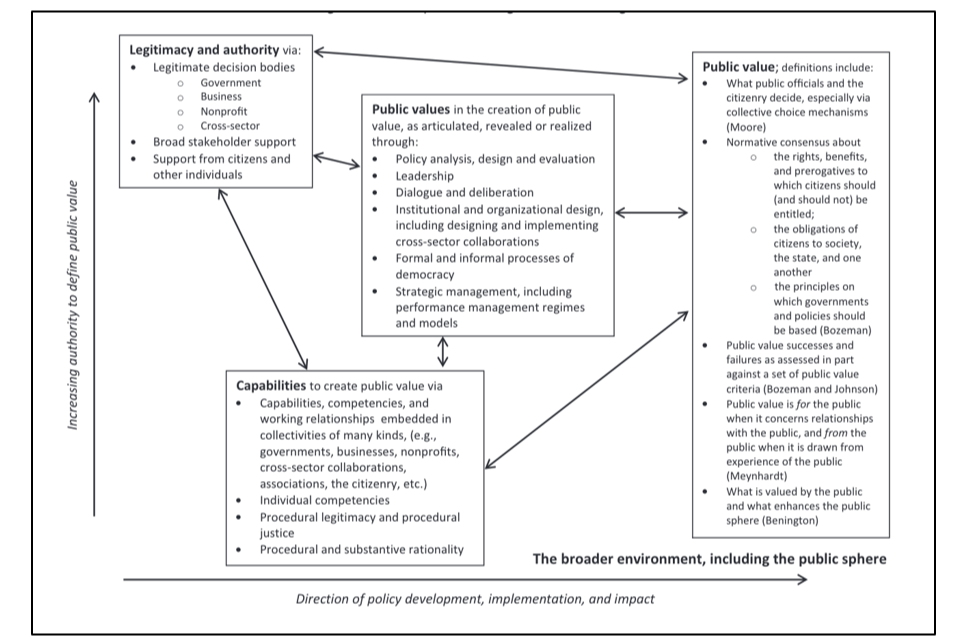

From a practical perspective, the indeterminacy of public value implicit in the four definitions listed above has opened up further dilemmas about how public managers formulate the ‘public value propositions’ at the core of PV theory. In this respect, a primary concern regards the tension between the notion of public value as a framework for strategic public management (cfr., Moore) and the notion of public values as a framework for democratic governance (cfr., Bozeman). To address this and other issues, the more recent literature integrated – or challenged – some of the key premises behind PV theory in order to preserve and increase its practical relevance. Bryson, Crosby and Bloomberg (2015) developed a new version of Moore’s strategic triangle: i.e. the ‘public value governance triangle’ (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. The public value governance triangle[footnote 5]

On the one hand, they expanded the content of each corner of the original triangle – thus showing the connections between the four key analytical levels previously illustrated (i.e. psychological, managerial, policy, societal). On the other hand, they further specified how public managers prompt the direct or indirect creation of public value by means of ‘six key practices’:

- Policy analysis, design, and evaluation

- Leadership

- Dialogue and deliberation

- Institutional and organisational design

- Formal and informal processes of democracy

- Strategic management.

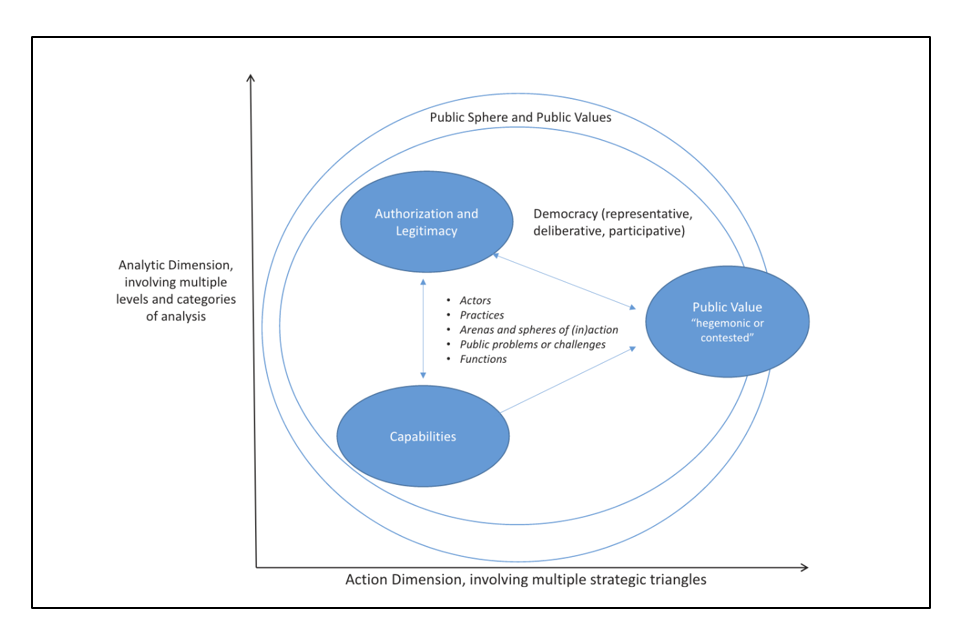

Later scholarship reappraised the role of public management in public value creation – notably, by focusing on the key importance of multi-stakeholder collaboration. Crosby, ‘t Hart and Torfing (2017) advocated “to shift away from asking how some public managers are able to create public value by displaying strategic entrepreneurship and towards how orchestrated collaborative work can foster and consolidate value-creating public innovation” (p. 659). Revising the role of public manager as an ‘orchestrator of collaboration’ rather than as an ‘innovation hero’, they identified four types of public value leadership (sponsors; champions; catalysts; implementers) and pushed for a greater focus on “designing and using forums, transitioning from forums to the more formal arenas of policymaking, and fostering constructive conflict and collective creativity” (p. 663). On similar lines, Bryson et al. (2017) called for the development of a ‘multi-actor’ approach to ‘public value co-creation’ in which managers cooperate with the public, private, voluntary, and informal sectors of society to cope with the growing relevance of ‘wicked problems’ (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Adapting the public value governance triangle to a multi-actor context[footnote 6]

Drawing from similar preoccupations, Mazzucato and Ryan-Collins (2022) have engaged with PV theory to apply its insights beyond the domain of public service delivery and into economic policy. By doing so, they challenge the view within economics that ‘value creation’ happens only in the private sector by highlighting how the markets in which firms operate – and ‘value’ materialise – are “the outcome of the interactions of individuals, firms, and the state” (p. 352). As such, they propose to enlarge the scope of PV theory from the micro-level analysis of public management practice to the macro-level analysis of governments’ role in ‘market-shaping’ through a “mission-based approach” where “direction setting is followed by cross-actor, cross-sector and cross-disciplinary interactions”; “new ways to engage with the public”; and “new evaluation indicators” that “capture the economy-wide benefits of such policies” (p.355). Bryson, Crosby and Barberg (2023) underline how such effort demands public managers embrace ‘strategy management at scale’ – i.e. to ‘expand’ their strategic management practices to a multi-actor context, and, accordingly, the development of new techniques.

1.3. Main criticisms of Public Value theory

Due to its particular features, PV theory has been subjected to different critiques, among which one of the most prominent is articulated in Rhodes and Wanna (2007):

- As a philosophy of public management, it has been accused of asking civil servants “to rebel against standard politics and usurp the democratic will of governments” (p. 415).

- As a tool for decision-making, it has been accused of prompting civil servants into the “impossible” task of defining “a priori the substantive content of public value” (p. 416).

- As a set of interventions, it has been accused of blending normative “criteria for evaluating aspirations” with empirical criteria “that seek to assess evidence” (p. 406).

An additional critique can be found in Dahl and Soss (2014) who draw on similar arguments to highlight how PV theory sidesteps foundational questions of power and conflict while advancing prescriptions that are at odds with important democratic values, such as political contestation and inclusivity within decision-making.

These critiques have been forcefully rebutted by key scholars of PV theory (Alford and O’Flynn, 2009, pp. 174–178; Moore, 2015, pp. 110–118). Indeed, PV theory acknowledges that public management’s authority is constrained by political decision-making; that the definition of public value is deemed relative to contingent circumstances (i.e. the ‘task environment’); and that its intent is at the same time both empirical and normative.

1.4. Public Value as outcome and process

Moore (2019) has recently argued that “starting as a narrow vocational project, [PV theory] has blossomed into a larger humanitarian project focused on building the capacities of democratic governance, and the pursuit of the good and the just” (p. 370). However, still considerable work needs to be done in order to advance our understanding of PV – both within the field of public management, and the broader field of democratic and economic governance (O’Flynn, 2021). From the standpoint of this literature review, we conclude this section by defining PV both as an outcome and as a process. As an outcome, we define it as the achievement of broad and widely accepted societal goals – primarily, but not exclusively, through the delivery of public goods and services (cfr., Mazzucato and Ryan-Collins, 2022). As a process, we define it as the purposeful alignment between the ‘mission’ of a given public sector organisation (i.e. its specific tasks), its ‘authorising environment’ (i.e. its sources of legitimacy), and its ‘operational capacity’ (i.e. its available resources, skills, and capabilities) (cfr., Moore, 1995).

2. How to measure public value?

2.1. Measuring Public Value as ‘Value for Money’

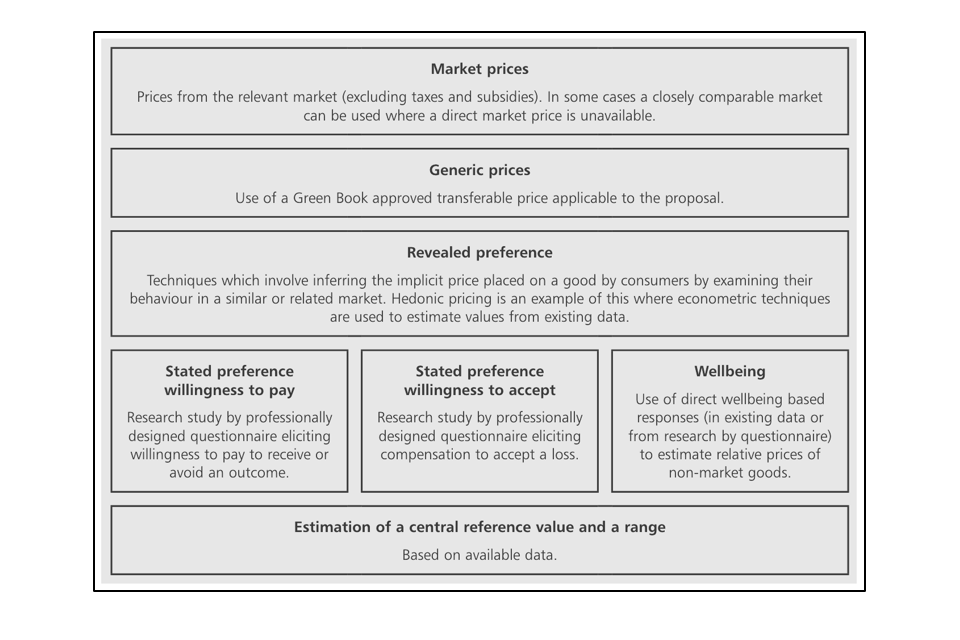

Despite the scholarly debate about the notion of PV synthesised in the previous section, the logic adopted by most governments for its measurement is still based on strictly economic premises. This state of play is captured by the concept of ‘Value for Money’ (VfM) – which captures the judgement performed by public organisations about the optimal use of public resources to achieve public objectives as based on the ‘four Es’ of Economy, Efficiency, Effectiveness, and Equity (Glendinning, 1988; Goddard, 1989; see also OECD, 2015). VfM is operationalised through a family of evaluation methods, among which the most common are ‘Cost-Effectiveness Analysis’ (CEA) and ‘Cost-Benefit Analysis’ (CBA). On the one hand, CEA relates the costs of alternative programme or policy interventions to specific measures of programme or policy effectiveness. On the other hand, CBA weighs the costs of the alternative programme or policy interventions against the monetary value of the expected benefits (Cellini and Kee, 2015). Today, the UK’s HM Treasury guidance on the use of public money relies on ‘social’ forms of CBA and CEA that estimate ‘shadow prices’ for those costs and benefits without a market price – e.g. those related to environmental, social, and health welfare (HM Treasury, 2020, 2022; see Figure 4).

Figure 4. HM Treasury Green Book: Valuation methods for non-market prices[footnote 7]

The dominance of CBA and its variants at the core of institutional policymaking has been long questioned, if not explicitly rejected as incompatible with PV theory due to its reductionist approach to the notion of value into monetary terms (Bozeman, 2002). A rich body of literature addressed this concern by developing calculation methods and discount techniques designed to help practitioners account for a more diverse range of ‘non-market’ values and ‘standing’ interests into programme and policy intervention (see, e.g. Boardman et al., 2022). While acknowledging the growing complexity of practicing CBA, its supporters retained the view that such technique helped make clear “what is known, what is not known, and what needs to be known” to and by policymakers (Belfield, 2015, p. 108). However, recent developments in the academic and policy debate are questioning once again the ability of CBA (and CEA) to support public value creation.

Sharpe et al. (2021) identify the major weakness of CBA in the lack of appreciation for situations of i) non-marginal change (i.e. when structural change is not expected); ii) heterogeneity of value metrics (i.e. when impact is also of a non-economic mature); and iii) fundamental uncertainty (i.e. when the number and probability of possible scenarios is not quantifiable). This consideration is especially relevant in today’s context – characterised as it is by dramatic shifts such as climate change, pandemics, and regional inequalities in the UK economy. Based on this reasoning, they propose to generalise CBA into ‘Risk-Opportunity Analysis’ (ROA): a tool designed to evaluate policy decisions under the three conditions highlighted above, of which CBA may constitute an application for situations of marginal change. In an earlier exploratory study for the UK’s Business Department, Mazzucato and Kattel (2020) echo this reasoning and identify alternative methods from the academic literature that can complement traditional VfM techniques – of which some are directly inspired by PV theory.

2.2. Measuring Public Value as a set of heuristics

In this respect, the three most prominent PV measurement tools derived from academia reflect the different levels of analysis adopted by leading scholars. Crucially, all of them propose a very different understanding of PV than those suggested by VfM approaches. Rather than methods of formal evaluation, PV measurement tools are ‘heuristic devices’: i.e. “artificial constructs to assist [managers] in the exploration of social phenomena” (Scott and Marshall, 2009). These are:

- at the psychological level, the Public Value Scorecard (PVSC) (Meynhardt, 2015);

- at the managerial level, the Public Value Accounting approach (Moore, 2013, 2015);

- at the policy level, the Public Value Mapping approach (Bozeman and Sarewitz, 2011).

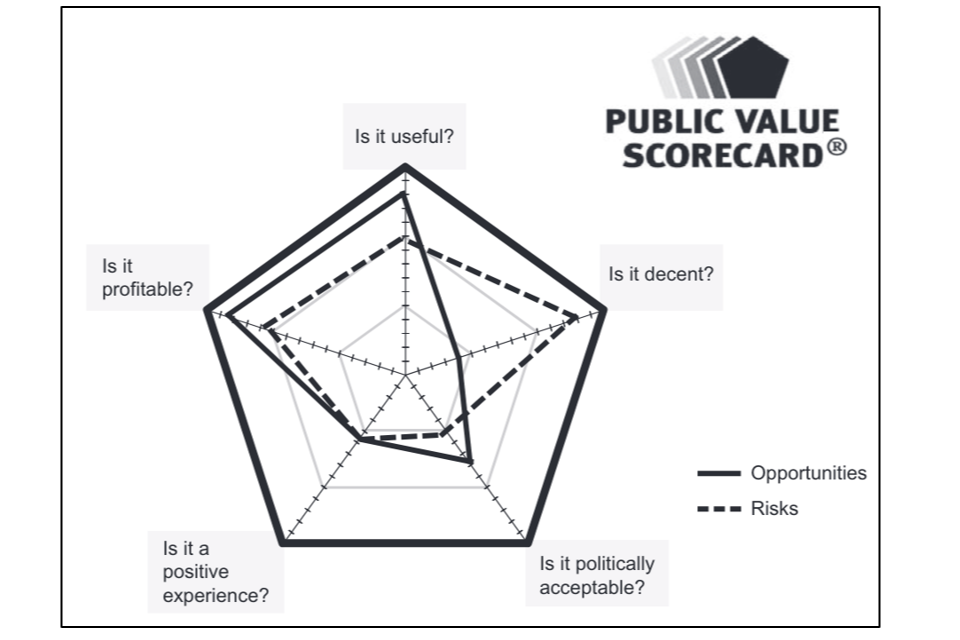

The Public Value Scorecard (PVSC) has been elaborated by Meynhardt (2015) under the main assumption that public value “starts and ends with the individual: it is not delivered, but perceived” (p. 157). Drawing on an understanding of individual basic needs and their relationship with PV, the scorecard is composed of five dimensions:

- moral-ethical (‘is it decent?’);

- hedonistic-aesthetic (‘is it a positive experience?’);

- utilitarian-instrumental (‘is it useful?’);

- political-social (‘is it politically acceptable?’); and

- financial (‘is it feasible?’).

The proposition of the PVSC is to support managerial decision-making by providing them with a tool to better identify societal needs and manage potential trade-offs among different priorities. The PVSC can be completed by means of different inquiry techniques – including through structured interviews, workshops, large-scale surveys, and web scraping (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. The Public Value Scorecard (general form)[footnote 8]

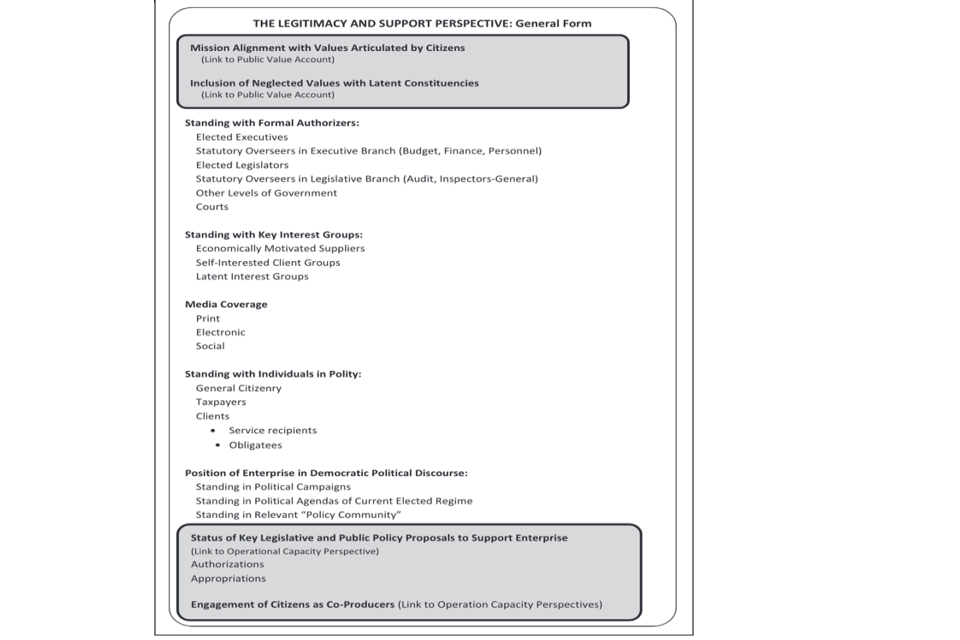

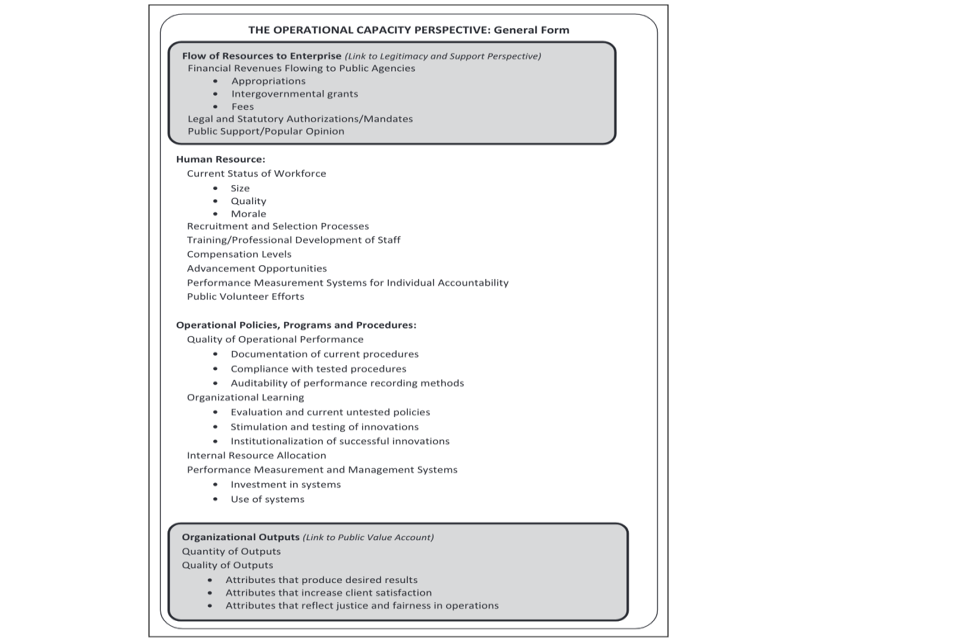

While the PVSC departs from the analysis of the individual perception of PV, the Public Value Accounting approach focuses on the level of public management. The approach builds on the ‘balanced scorecard’ first developed by Kaplan and Norton (1992) for the private sector in order to integrate the ‘strategic triangle’ (see Figure 1) with a framework that helps public managers develop performance measurement systems focused on public value creation. First articulated by Moore (2013), the approach is made of two components: i) a Public Value Account; ii) a Public Value Scorecard. In his words, the Public Value Account is “meant to do for [public] managers what the financial bottom line does for private managers: provide a way of accounting for the costs incurred and valuable results produced by a government organisation” (Moore, 2015, p. 123). The PV Account differs from a traditional ‘private’ account in terms of value-creating assets (money and authority); arbitrage mechanisms (individual clients and the community as a whole); and moral standards (utilitarian satisfaction and societal fairness) (see Table 1).

Table 1. The Public Value Account (general form)[footnote 9]

| Negative Public Value | Positive Public Value |

|---|---|

| Financial costs | Achievement of collectively defined mission/desired social outcomes |

| Client satisfaction: - Service recipients - Obligatees |

|

| Unintended negative consequences | Unintended positive consequences |

| Social cost of using state authority | Justice and fairness: - At individual level in operations - At aggregate level in results |

Framed within the ‘strategic triangle’, the Public Value Account articulates the perspective hinted at by the ‘public value’ circle and breaks it down into manageable units of analysis that the public manager can build upon in order to disentangle key dynamics of public value creation pertaining to their organisation. Expanding on this line of reasoning, the Public Value Scorecard proposed by Moore (2015) integrates the Public Value Account perspective with the extended illustration of the other two perspectives found in the ‘strategic triangle’: i.e. the ‘legitimacy and support’ perspective (see Figure 6) and the ‘operational capacity’ perspective (see Figure 7). Crucially, Moore (2015) proposes that the “abstract categories” of the Scorecard “have to be given richer content by developing both more specific concepts and measures attached to those concepts” (p. 129). In this sense, he invites public managers to experiment with his tools in order to support the development and institutionalisation of new accounting standards (Moore, 2014, p. 475).

Figure 6. The Public Value Scoreboard – Legitimacy and support (general form)[footnote 10]

Figure 7. The Public Value Scoreboard – Operational capacity (general form)[footnote 11]

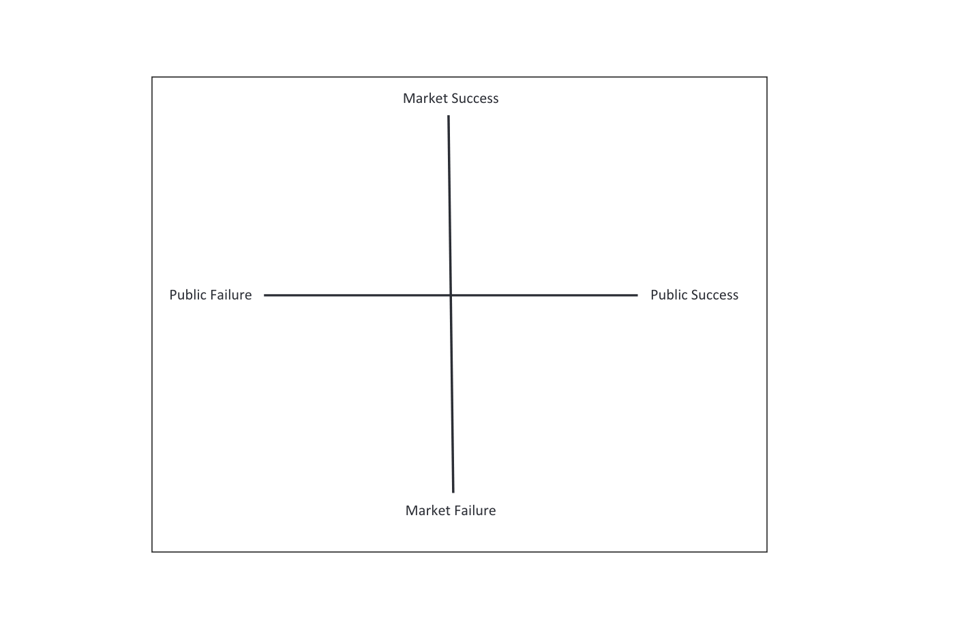

Finally, the Public Value Mapping approach integrates the former two PV measurement tools by focusing on the policy level. The approach is built on the notion of ‘public value failure’: i.e. the failure that occurs “when neither the market nor public sector provides goods and services required to achieve public values” (Bozeman and Sarewitz, 2011, p. 16). To address such failure, the Public Value Mapping approach provides an initial set of criteria aimed “to expand the discussion of public policy and management” by supporting the assessment of “possible failures in achieving [case-specific] public values” (pp. 17-18). Such criteria can include protection of the public sphere, creation of progressive opportunities, imperfect monopolies in service provision, and potentially others as seen fit by the analysts (Welch, Rimes and Bozeman, 2015). From a methodological perspective, the approach unfolds in four steps:

- identification of a core set of public values;

- criteria-based assessment of public value ‘failures and successes’;

- analysis of the ‘value analysis chain’ (i.e. interrelationships among values);

- analysis of the relationships between ‘market failures/successes and ‘public failures/successes’ by means of a simple Public Value Mapping grid (see Figure 8).

The overarching purpose is not to substitute existing tools, but to enable “a deeper and richer discussion around policy implications” and “drive the consideration of public values forward” (Welch, Rimes and Bozeman, 2015, p. 142).

Figure 8. The Public Value Mapping grid (general form)[footnote 12]

Overall, none of the PV measurement tools reviewed in this sub-section aims at a comprehensive overhaul of existing VfM approaches. As anticipated earlier, their primary purpose is heuristic – the main goal being that of helping public management explore and structure facets of their policy work that such VfM approaches do not account for. Drawing on the combined experience of more than 40 years of applying PV theory and tools with public executives, de Jong et al. (2017) suggest four ‘principles of application’ for their uptake in the public sector:

- Value ambition – i.e. tools should encourage processes of “restless value-seeking”.

- Strategic space – i.e. tools should help managers “reframe […] the challenge at hand”.

- Conflicts – i.e. tools should help managers “engage with” unavoidable “ambiguity”.

- Personal role – i.e. tools should “keep PV management personal” (pp. 614-615).

These principles reflect the intent of PV scholars to support public managers into the development of new tools at a time where traditional ones seem to be increasingly unfit for the scope of today’s societal challenges. Such intent is explicitly normative but rarely prescriptive. Rather, scholars acknowledge that such tools should be judged based on public managers’ ability to make use of them to cope with contemporary challenges.

2.3. Measuring Public Value in government practice

Notwithstanding the plethora of proposals developed by scholars, only few governments have adopted the notion of PV in their operations. Among those that did, the virtual totality pertains to Anglo-Saxon Countries – such as the UK, Australia, New Zealand, and the US.

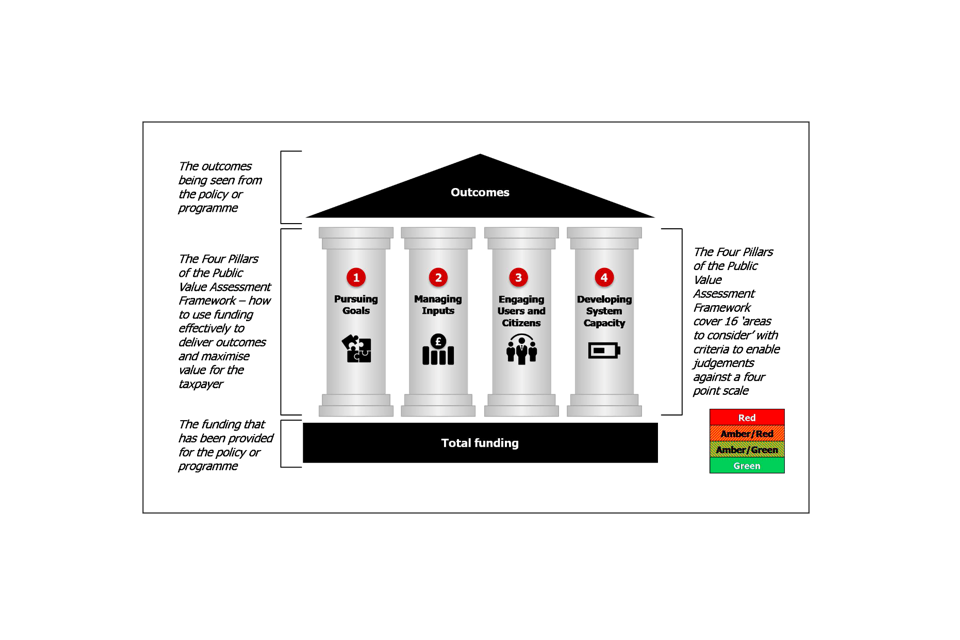

In this short list of governments, the UK is the one that has engaged the most with PV. The first use of this concept appears in a discussion paper released by the Strategy Unit of Prime Minister Tony Blair’s Cabinet Office (Kelly, Mulgan and Muers, 2002). In the paper, PV is presented as an analytical framework that can help guide civil service reform and serve as a “rough yardstick against which to gauge the performance of policies and public institutions” (p. 4). However, their framework narrowed down the scope of the original notion proposed by Moore – e.g. by translating ‘operational capability’ in services and focusing on the whole of public administration rather than Moore’s public manager. A report written by Michael Barber 15 years later for HM Treasury developed a PV framework to explore its contribution to public sector productivity (Barber, 2017, p. 5). Building on Moore’s (2013) extension of the strategic triangle, his framework operationalises PV into four pillars showing “how to use funding effectively to deliver outcomes and maximise value for the taxpayer” (p. 26) (see Figure 9). The four pillars are:

- Pursuing goals: i.e. the ability of a public sector organisation to formulate clearcut goals; to design ambitious, yet feasible strategies; and to monitor their progress throughout implementation.

- Managing inputs: i.e. the ability of a public sector organisation to ensure that money is being spent in the right quantities; in the right ways; at the right time; and in pursuit of the agreed goals.

- Engaging citizens: i.e. the ability of a public sector organisation to ensure legitimacy of the goods and services provided to citizens – including through optimal user experience and engagement.

- Developing system capacity: i.e. the ability of a public sector organisation to ensure its long-term institutional viability – for example, by nurturing its capacity to innovate; plan; engage with the delivery chain; work beyond silos; upskill its workforce; and review its performance.

Figure 9. Michael Barber’s Public Value framework[footnote 13]

Each of the four pillars is composed of different areas that can be assessed based on a four-point scale – ranging from ‘good’ (green) to ‘highly problematic’ (red). As a result, the framework aimed to provide a common language across the public sector about public value – as well as facilitate learning within and across different public sector organisations by means of regularly held ‘Public Value Reviews’. Barber’s PV framework was eventually adopted by HM Treasury as a revised version that simplified the original set-up and streamlined its language (HM Treasury, 2019). However, the framework was not streamlined within the UK government’s policy practice. Rather, it has been suggested by the Treasury as a discretionary, non-compulsory tool that public sector organisations can leverage to perform organisational diagnostics, take stock of or inform a given policy or programme, or develop a comprehensive evidence base on performance management.

Relative to the UK experience, Australia’s stands out for its direct engagement with Moore’s ideas. In particular, the Government of South Australia aimed at developing a whole-of-government reform around the notion of PV throughout the last years of Prime Minister Jay Weatherhill – i.e. from 2015 to 2018 (Ballintyne and Mintrom, 2018). The effort built upon the groundwork of previous initiatives – including the design of a dedicated teaching unit within the Executive Master of Public Administration (MPA) managed by the Australia and New Zealand School of Government (ANZSOG). It is through the MPA that the Government of South Australia engaged with Mark Moore himself by means of numerous meetings and seminars with public sector chief executives – one of which had Moore observing the Government’s attempt to be “the first example […] of a deliberate effort to scale up the application of the public value framework” (p. 187). The initiative was built around a dedicated governance structure that cut across the South Australian public sector and ensured clear accountability mechanisms for the implementation of the public value perspective throughout its policies and programmes. Among these, the following were also included:

- The development of a ‘Public Value Account’ for each proposal submitted by the Cabinet.

- The revision of the format used by public agencies in the write-up of their annual reports.

- The establishment of a ‘Public Value Network’ of professionals from various backgrounds and areas of operations acting as ‘change champions’ within their organisations.

In line with Moore (2015), the goal of the reform was not to impose on each public sector organisation a distinctive approach to PV, but rather to support the gradual transformation of their accounting practices in ways that were coherent with such an approach. In 2019, a similar approach was also adopted by the Government of New Zealand in the revision of their public procurement rules (Allen, 2021). The main actor was the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment, who adopted the definition of ‘broader outcomes’ to identify the social, environmental, cultural, or economic benefits that can deliver long-term public value for New Zealand. To streamline the adoption of the ‘broader outcomes’ approach, the Ministry identified four ‘priority outcomes’ to which ‘designated contracts’ operating across public sector organisations would need to contribute by pursuit of the new rules. While more loosely connected to the PV framework, the initiative reflects the process suggested by Moore (2015): i.e. empowering civil servants to test out new solutions to embed a broader range of values and possibilities in their daily policy work.

Relative to the three cases reviewed above, the United States and the European Union provide examples of a much less institutionalised approach to PV. In the case of the US, the prominent arena of emerging PV practice is at the city level – in particular, thanks to the Bloomberg Harvard City Leadership Initiative, which has seen multiple cohorts of mayors engage with the fundamental ideas of PV theory by a practice-based approach (see, e.g. Gilman et al., 2023). Conversely, the EU seems to lag behind – with only recent publications from the Commission’s Joint Research Centre engaging more proactively with such concepts? (Millard, 2023).

A final remark concerns the experience of the ‘What Works Centre’ initiative – first launched in the UK by key ministers from the Treasury and Cabinet Office at the innovation foundation Nesta in order to inquire into and marshal new ways of making smarter spending decisions by means of a broader range of metrics and evidence base. A comprehensive review of such experience – now institutionalised by the UK Government into the ‘What Works Network’ – highlights the context-specific nature of the process underpinning the redefinition and ensuing measurement of public value (Mulgan et al., 2019). In this respect, while illustrating an ever-growing array of technical possibilities for expanding and integrating conventional VfM approaches, the review calls for a view of public value “not [as] a static fact”, but as something that “arises from the interaction of changing options for supply and changing demands and public priorities” (p. 5).

2.4. Public Value as a strategic management tool

This section has highlighted how public value can be measured by means of complementary tools: on one hand, those focused on outcome (e.g. Cost-Benefit Analysis, Cost-Effectiveness Analysis, Risk-Opportunity Analysis); on the other, those focused on process (e.g. Public Value Mapping, Accounting, Scoreboard). Current research and practice do not provide a definitive answer for the question of how to measure public value creation within the public sector. While CBA firmly sits at the core of contemporary government operations, its ability to yield effective policy analysis is increasingly put under question and thus integrated with approaches that focus on i) the ability of public sector organisations to ‘maximise value for the taxpayer’ via better delivery (i.e. HM Treasury’s Framework); and ii) the development of new accountability mechanisms embedded within policy design and delivery (i.e. South Australia Government’s approach). These efforts reflect the growing pressure engendered by contemporary societal challenges and a relentless activity of reflection on how to ensure public sector organisations’ ability to cope with them (i.e. New Zealand’s ‘Broader Outcomes’ approach). In this respect, PV appears to highlight greater usefulness as a strategic management tool: i.e. as a tool to analyse, evaluate, and integrate existing performance management systems and ensure their alignment with an evolving array of goals and priorities. The case study described in Box 1 (see below) highlights the practical implications of this perspective.

Box 1. Case study: Measuring public value at the BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) first adopted the notion of PV in 2004 – when it published a manifesto outlining the intention to adopt it as a “hard-edged tool for decision-making about what the BBC should do – and, as importantly, what it should not do” (British Broadcasting Corporation, 2004, p. 46). First elaborated as a response to a media landscape brought into turmoil by the rapid diffusion of the digital economy, in the report the BBC committed itself to a “new system for assessing new services and monitoring the performance of existing ones, based on objectivity, rigour, and transparency (p. 15). On the one hand, the manifesto reflected the ambition to advance a comprehensive reform of the whole corporation based on the pursuit of i) individual; ii) citizen; and iii) net economic value. On the other hand, however, it was followed by scathing critique and dismissed by many as a ‘rhetorical strategy’ aimed to ensure its public subsidy (see Alford and O’Flynn, 2009 for a thorough reconstruction).

More than a decade later, the BBC partnered with the UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose (IIPP) to develop a new model of public value creation (Mazzucato et al., 2020). The new model was developed by means of an applied research process which integrated existing literature with in-depth interviews and workshops with key internal and external stakeholders. The new model was built based on several premises: first, that the BBC delivers individual, societal, and industry value; second, that the BBC is well placed to act as a ‘market shaper’ in multiple ways (i.e. as inventor, investor of first resort, innovator, and platform) and at multiple levels of analysis (i.e. content development, standards setting, talent, technology advances); third, and last, that its underlying public value creation process is therefore inherently dynamic (i.e. it generates spillover effects that can eventually lead to structural change). Based on these assumptions, the early-stage prototype framework developed by UCL IIPP was accompanied with a set of recommendations that prompted the BBC to reflect on their notion of (dynamic) public value; test new evaluation methods aligned with the Corporation’s long-term strategy; and develop new data analytic capabilities in the process of doing so.

Overall, this example shows how the notion of PV can become a strategic management tool: namely, by developing context-specific heuristics that can empower public leaders to reflect on their public sector organisation’s purpose and develop heuristics, metrics, and methods of accountability that can ensure the public sector organisation’s ability to progress towards the agreed direction.

3. How to deliver public value in the 21st Century?

3.1. Limitations of New Public Management

To appreciate the relevance of PV as a strategic management tool for today’s governments, it is useful to contextualise it within the broader landscape of contemporary developments in public administration theory and practice. From this standpoint, the rise of PV theory and practice can be interpreted as the response to a state of increasing and widespread dissatisfaction with the results of New Public Management (NPM) (O’Flynn, 2007). NPM is a public administration paradigm that was first adopted in the 1980s among Anglo-Saxon countries (the US, UK, Australia, New Zealand) and gradually spread across Europe (Pollitt and Bouckaert, 2017). Conceived in itself as a reaction to perceived weaknesses in traditional approaches to public administration, NPM reforms advocated for the development of performance management systems based on explicit standards and measures, the disaggregation of public sector into ‘at arms’ length’ units, and the outsourcing of public service provision as key to more efficient public spending (Hood, 1991, pp. 4–5). These principles were explicitly advocated with the stated purpose of ‘reinventing government’ by igniting the entrepreneurial spirit of its public servants and ensuring the ability of public sector organisations to be ‘competitive’, ‘results-orientated’ and ‘customer-driven’ (Osborne, 1993).

NPM reforms encompassed a set of distinctive assumptions about human behaviour – including that of the Civil Service. In particular, its assumption of individualism and economic rationality had a contradictory effect on the autonomy of public management: on the one hand, increasing its power on administration via performance management systems and incentives; on the other hand, diminishing its power on policy formation, and thus on the targets assigned to them. Stoker (2006) summarises this state of play by arguing that NPM “proclaims […] lean, flat, autonomous organizations […] steered by a tight central leadership corps” and yet rejects “the idea of a public sector ethos […] as simply a cover for inefficiency and empire building by bureaucrats” (p. 46; see Table 2). Due to this peculiar mix of elements, NPM has had a multi-layered impact on public administration. On a positive note, it opened up room for innovation in the public sector – e.g. by nurturing public sector organisations’ capacity to foster public-private collaboration, ensuring public accountability via evaluation, and incorporating citizens’ needs (Kattel et al., 2023). On a negative note, it imported assumptions from the private sector that are at odds with the logic of public – including the ‘siloification’ of interconnected policy domains in autonomous agencies, the reliance on ‘objective’ performance metrics in provision of incommensurable public goods, and the use of management ‘by numbers’ practices in contexts of high strategic ambiguity (Mintzberg, 1996).

Table 2. Dilemmas associated with different public management narratives[footnote 14]

| Dilemmas | Traditional Public Administration | New Public Management | Public Value Management |

|---|---|---|---|

| Usurping democracy | The domination of officialdom | ||

| A system that frustrated politics “Yes, minister” syndrome |

Management chases target, not political demands The extenuation of contract relationships makes political control even more problematic Citizens reduced to consumer |

Managers doing politics could push citizens and politicians to the margins There are severe limits to the extent that politics can be managed and remain open and legitimate |

|

| Undermining management | The politicisation of bureaucracy | The undermining of professional judgement | Encouraging a talking shop rather than action-orientated management |

| Key Safeguards | Conventions and constitutions | Alertness of political leadership | Good practice and stakeholder pluralist review to ensure that the system delivers effective stakeholder democracy and management |

These features of NPM ultimately hampered the success of its reforms. In terms of results, its promise of a ‘government that works better and costs less’ often translated into a story of a ‘government costed more and worked worse’ (Hood and Dixon, 2015). In terms of administrative practices, it was criticised for hardening whole-of-government coordination, severing the link between policy design and implementation, and inducing ‘gaming’ behaviour among managers – their focus being more on the target than the intended outcome (Pollitt and Bouckaert, 2017). In the words of Peters and Savoie (1994), NPM ‘misdiagnosed the patient’: on the one hand, by deliberately focusing and still having little impact on those public sector organisations engaged with policy delivery (‘fixing the boiler room’); on the other hand, by overlooking the evolving complexity of society and failing to nourish public sector organisations’ ability to cope with it by means of policy design and innovation. Recently, this side effect has been summarised by Pahlka (2023) with the notion of ‘policy vomit’: i.e. what happens when public services are not designed with citizens in mind, but rather reflect the policy requirements of those that commission their implementation.

3.2. Emerging trends in Public Administration

From the late 1990s, the increased recognition of the limitations of NPM led scholars as well as practitioners into the search for new public administration paradigms and tools. Far from having turned into a shared consensus, the ‘post-NPM’ movement is today reflected into the persisting relevance of three major strands of theory and practice: Digital Era Governance, New Public Governance, and the Neo-Weberian State (Torfing et al., 2020a).

The notion of Digital Era Governance (DEG) identifies the constellation of “information technology (IT)-based changes in public sector management systems and in methods of interacting with citizens and other service-users in civil society” (Dunleavy et al., 2006, p. 468). The literature on DEG is structured around three ‘waves’ of technological and administrative innovation – each contributing to three pillars of reform:

- reintegration (reversing the fragmentation of public sector processes fostered by NPM);

- needs-based holism (creating user-centred services through agile government structures); and

- digitalisation (adapting the public sector to embed electronic delivery at the heart of its model).

In this context, the first ‘wave’ has seen the emergence of the first e-government interfaces, web redesigns and gradual re-internalisation of IT services. Pushed by the need for cost-saving gains in a period of economic austerity, the second ‘wave’ has reflected an increased reliance on big data and a relatively more mature online offer (e.g. in terms of service integration) (Margetts and Dunleavy, 2013). Finally, the third ‘wave’ has more recently opened up new possibilities for public sector organisations to analyse service data and manage delivery – including through the development of data science and AI capabilities (Dunleavy and Margetts, 2023).

In contrast to DEG, the notion of New Public Governance (NPG) focuses instead on the evolution of public administration practice towards the establishment of a ‘plural’ state (i.e. “where multiple inter-dependent actors contribute to the delivery of public services”) and a ‘pluralist’ state (i.e. “where multiple processes inform policy making”) (Osborne, 2006, p. 384). Its intended purpose is to highlight the role of the design and evaluation of inter-organisational relationships – which include service users, their community, other key actors, and related technology – as critical to effective public service delivery. A main principle underpinning NPG is therefore the shift from the ‘product-dominant’ logic of NPM to a ‘service-dominant’ one. The latter differs from the former in that it is process-orientated; based on simultaneous production and consumption; and founded on co-production of the service itself (see also Osborne, Nasi and Powell, 2021). As such, the ‘service-dominant’ logic demands public sector organisations not simply ensure effective public service design, but that they are also “responding to the service expectations of users and training and motivating [their] workforce to interact positively with these users” (Osborne and Radnor, 2016, p. 59).

Last, the notion of a Neo-Weberian State (NWS) was first proposed by Pollitt and Bouckaert (2004) in order to highlight the emergence of a “distinctive [public administration] reform model […] in the continental European states” (Pollitt and Bouckaert, 2017, p. 121). On the one hand, such a model preserves essential features of the traditional Weberian model of public administration –notably, the role of bureaucracy as the organisational representation of the ‘rule of law’ principle. On the other hand, it integrates it with new features that reflect contemporary challenges and concerns. These include the integration of:

- internal orientation (i.e. bureaucratic rule-following) with external orientation (i.e. meeting citizens’ needs);

- professional culture (i.e. focused on quality service) with use of market mechanisms;

- traditional representative democracy with devices for consultation and direct citizens’ deliberation;

- procedural rules with greater results-orientation; and

- legal competencies with managerial skills (Bouckaert, 2023, pp. 49–50).

Overall, the public administration reflected by the notion of NWS is one that “keeps a significant share [of services within] the public sector and has ‘hierarchy’ as its main driver” both within the public sector and in partnerships with “private profit and not-for-profit sector” (p. 49).

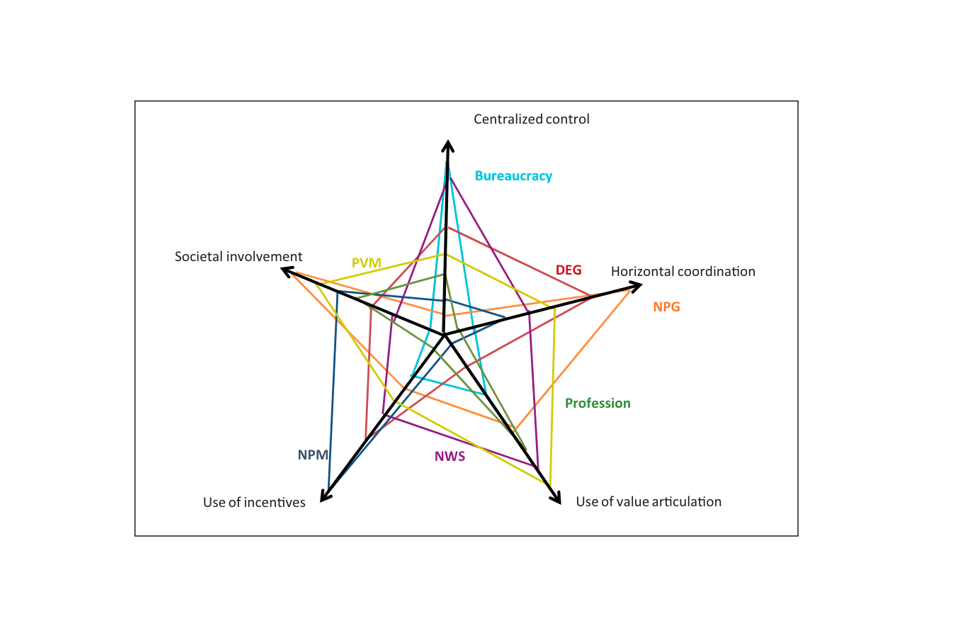

All considered, these emerging trends in public administration highlight a process of institutional ‘layering’ in which the limitations of NPM are addressed in various ways, but constitute “anything but a clearly marked shift from one to the other model” (Reiter and Klenk, 2019, p. 23). However, a structured comparison of the different paradigms highlights three shared characteristics:

- ‘re-politicisation’ of the Civil Service (i.e. role of public management in value articulation);

- greater focus on horizontal (decentralised) over vertical (centralised) coordination; and

- greater focus on societal involvement (e.g. co-production/collaboration in public service delivery/governance) over the use of economic incentives (Torfing et al., 2020a; see Figure 10).

In this landscape, the notion of PV (PVM in Figure 10) provides a set of logics, narratives and methods that reflect these trends coherently and contextualise them in the everyday activity of public management.

Figure 10. Comparing public governance and management paradigms[footnote 15]

3.3. Public Value as new ethos of civil service

Today, there is a growing consensus around the idea that the key challenges of the 21st century – including pandemics, climate change, rapid digital transformation, and economic inequality – call for a broader reappraisal of how the public sector operates (see, e.g. Termeer et al., 2015). In this context, both the role of the state and the assets that underpin its operations – how it designs, implements, and evaluates them – are increasingly brought under the limelight of the policy debate (Roberts, 2020). In terms of the state’s role, there is a renewed interest into the multiple facets of public action – including with respect to its potential to act as a ‘steward’ of societal transformation by enabling, facilitating, and leading new forms of engagement with both private and civic stakeholders (Borrás and Edler, 2020). In terms of the state’s assets, instead, new research focuses upon the routines of public administration practice, and thus distinguishes among the set of ‘capacity’ and ‘capabilities’ underpinning public sector organisations and determining their ability to perform such diversity of roles effectively (Kattel, 2022).

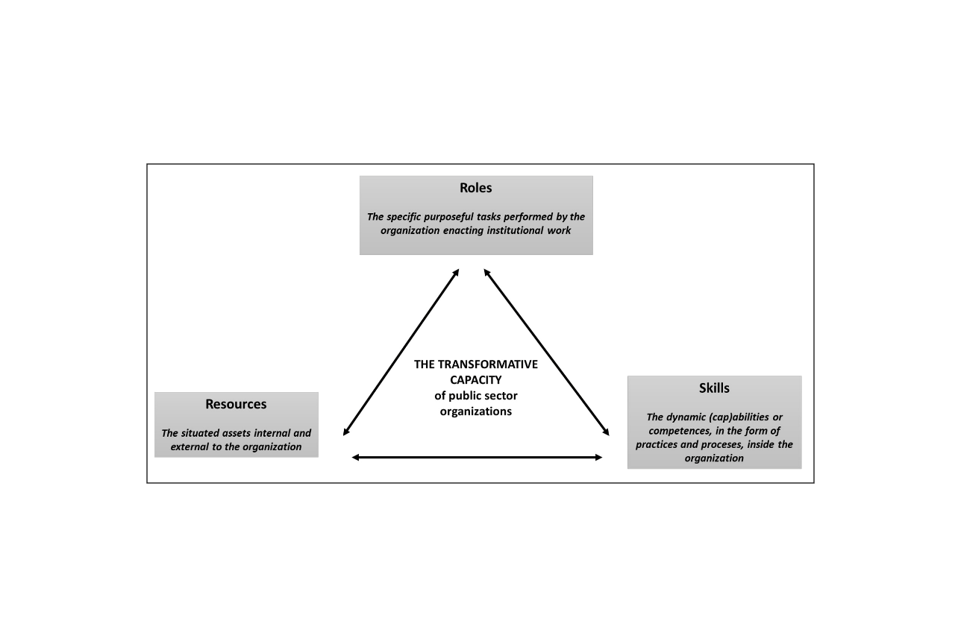

On the one hand, ‘capacity’ identifies the human, legal, financial, and administrative resources which in the long term define administrative routines. On the other hand, ‘capabilities’ shape long-term administrative routines – namely, by the short-term application of skills and competences that target existing processes within the public sector organisation and renew them in light of new challenges. Building on these two notions, Kattel, Drechsler and Karo (2022) posit that a critical task for today’s public management lies in achieving ‘agile stability’: combining “long-term policy and implementation capacities” and “dynamic exploration and learning capabilities” to enable their public sector organisation to ensure public value delivery while at the same time reflecting continuously on what ‘public value’ consists of in the first place (p. 53). Expanding on such thinking, Borrás et al. (2023) add on notion of ‘roles’ and define the interplay among the three components as the ‘transformative capacity’ of public sector organisations. By doing so, they provide a formative synthesis that highlights how ‘agile stability’ lies in the complex management of organisational roles, skills, and resources (see Figure 11).

This synthesis helps ground the micro-level view of ‘public value’ proposed by Moore (1995) as a rationale for public management and the meso-level view of ‘agile stability’ proposed by Kattel, Drechsler and Karo (2022) for organisational design. Moore’s (1995) ‘public value’ focuses on aligning the ‘mission’ of a public sector organisation, its ‘authorising environment’, and its ‘operational capacity’. Kattel, Drechsler and Karo’s (2022) ‘agile stability’ focuses on balancing out the need for change and continuity in a public sector organisation’s roles, capacity, and capabilities. In each respect, the two views reinforce each other in defining the task of today’s public management: i.e. to build a 21st century-fit civil service by championing purposeful organisational change within their public sector organisations.

Figure 11. Transformative capacity of Public Sector Organisations (PSOs) (general form)[footnote 16]

The emerging trends in public administration seen in the previous sub-section show that such effort is already taking place – albeit in a form which so far escaped a fully-fledged codification into a new paradigm – and evolving into a number of parallel directions. At the level of policy, the rise of the ‘mission-oriented’ approach proposes to challenge traditional approaches to welfare and economic governance by enabling public servants to prioritise the achievement of “concrete targets […] that act as frames and stimuli for innovation” over the maintenance of consolidated administrative practices (Kattel and Mazzucato, 2018; Mazzucato and Dibb, 2019, p. 2). At the level of administration, the rise of public sector innovation (PSI) – including the establishment of so-called policy innovation labs – reflected a growing curiosity towards experimentation within the public sector and a growing appetite for innovation within administrative practice (see, e.g. Tõnurist, Kattel and Lember, 2017; Bason and Austin, 2022; Blomkamp and Lewis, 2023).

The dynamics reflected in the paragraph above cannot be reduced to a unitary phenomenon. However, all contribute to an ongoing transformation within the ‘ethos’ of civil service. The word ‘ethos’, as defined by Merriam-Webster, identifies the ‘distinguishing character, sentiment, moral nature, or guiding beliefs of a person, group, or institution’. The ethos of a public sector organisation can be defined as the result of an interplay between two complementary systems of control that define what is ‘good’ or ‘bad’ public action:

- on one hand, the ‘outward facing’ system of codified commitments enshrined in administrative law;

- on the other, the ‘inward-facing’ system of (often) uncodified commitments enshrined in a public servant’s own deontological values and routines (Demmke and Moilanen, 2012).

In other words, the ethos of civil service identifies the explicit and implicit norms that regulate ‘how’ public value is defined, pursued, and potentially delivered.

In these terms, we argue that the debate illustrated in this section highlights the emergence of a new ‘ethos’ of civil service. Propelled by the distinctive challenges of the 21st century, such ethos posits PV at its own core: i.e. it proposes to embed the continuous reflection and examination of what public value consists of and how it can be pursued in an open-ended fashion, thus opening up to the iterative reassessment of how the public sector organisation can adapt accordingly through the revision of its own roles, capacities, and capabilities (cfr., ‘agile stability’). In this sense, the notion of PV as the ‘new ethos of civil service’ entails an appreciation of individual, organisational, and social learning – both within the whole-of-government and with the whole-of-society – at the centre of the public sector organisation’s engagements (Schön, 2010). Taking stock of the emerging trends highlighted so far, such ethos can be detailed into four characteristics of 21st-century governments (Demos Helsinki, 2023):

- Wisdom: i.e. the capability to anticipate future changes in the policy context and reform public institutions to cater for long-term phenomena. This feature challenges and integrates the subjection of administrative action to short-term political cycles and is often reflected into the greater adoption of foresight methodologies.

- Imagination: i.e. the capability to design, inspire, and motivate change in the operational routines of a public sector organisation while ensuring stability in delivery. This feature challenges and integrates the incremental nature of most public decision-making and is often reflected into the policy entrepreneurship of policy innovation labs.

- Collaboration: i.e. the capability to design and develop policy in partnership with multiple stakeholders within and beyond the public sector. This feature challenges and integrates the vertical responsibilities enshrined within policy silos and is often reflected into the establishment of new policy arenas and forums.

- Humility: i.e. the capability to revise existing assumptions about effective policy design and delivery to ensure continuous learning – primarily, through experimentation. This feature challenges and integrates application of the ‘rule of law’ and is often reflected into the use of methodologies inspired by or affine to design thinking.

4. How to professionalise public value delivery?

4.1. Bottlenecks against delivery

While the rise of ‘public value’ as a ‘new ethos of civil service’ provides an early indication of an emerging paradigm of public administration, it is still unclear how such ethos can be intentionally embedded into governments’ everyday practice: i.e. how to professionalise public value delivery. Professionalisation can be defined as the result of an institutionalisation process through which a certain group of individuals in possession of a body of expert knowledge, specialised education and usually a formal or informal ‘ethos’ gains recognition as a profession (Torfing et al., 2020b). On the one hand, the expertise of a profession entrusts those who possess it with large autonomy on how to deliver a complex service. On the other hand, its ethos ensures that the use made of such autonomy respects norms and standards that uphold the distinctiveness of the professional status (Roberts and Dietrich, 1999). To the extent that civil service and public management have the autonomy to make use of “restless, value-seeking imagination” (Benington and Moore, 2011, p. 3) – as suggested by PV theory – they can be deemed a ‘profession’. In this perspective, the shift to ‘public value’ as a ‘new ethos of civil service’ represents a change in the norms and standards that characterise the rationale of how public management works (see also Mintzberg, 1989 on ‘professional bureaucracy’). Still, research on how such a process of professionalisation has taken place is little to none. This adds on top of a landscape where solid empirical research on the application of PV altogether is also absent (Hartley et al., 2017).

As if this was not enough, the available evidence on public administration reform shows that the character of today’s public administration is often not amenable to the professionalisation of public value delivery as intended above. For example, Braams et al. (2021) shows a wide gap between the principles of emerging forms of innovation policy and the normative premises embedded within established public administration paradigms (such as traditional bureaucracy and NPM). Relatedly, Bouckaert (2022) observes that current changes in politico-administrative systems across OECD countries show contradictory trends. A growing understanding emerges that long-term challenges require: i) a ‘complementarity’ between the short electoral cycles of politics and the long-term view of administration; and ii) a shift from a view of bureaucracy as neutral, rule-following to one of bureaucracy as responsive to citizens’ needs and rule-interpreting. However, contemporary political changes suggest a hardening ‘dichotomy’ between the two: politics wants to exclude administrations, and administrators want to obstruct politics – thus resulting in weak public sector performance and, potentially, systems failures.

An additional challenge relates to the widespread lack of public sector dynamic capabilities: i.e. as previously defined, of the skills and competences that are needed to renew and strengthen the ability of public sector organisations to face contemporary challenges (Kattel, 2022). On the one hand, this challenge is a by-product of decades of underinvestment in or downsizing of public sector personnel – a trend which is ultimately epitomised in governments’ reliance on management consulting not just in auditing services, but increasingly also in terms of strategy design and implementation (see Mazzucato and Collington, 2023). On the other hand, however, the challenge also speaks of the difficulty of developing reliable indexes of public sector dynamic capabilities and incorporating them within the decision-making process. A recent review shows that among 50+ measurements, public sector organisations’ capacity is measured either as a precondition (e.g. meritocratic recruitment), outcome (e.g. corruption index) or proxy (e.g. presence of post offices in regions) (Cingolani, 2018). Initial attempts at overcoming such problems are based on the measurement of specific functions by means of self-assessment surveys administered to public servants (Meijer, 2019). However, these are not yet complemented by additional data-gathering tools – such as validation through interviews, site visits, and empirical data on outputs and outcome – nor form a part of public sector organisations’ toolbox. Capacity and capabilities are not assessed, and – consequently – there is little to no investment into developing these capacities and capabilities in the public sector.

Often, public sector organisations purport to overcome these challenges by establishing policy (or public) innovation labs (PILs): “design-for-policy entrepreneur[s]” endowed with the “capacity to develop creative policy options using design principles and methods” (Blomkamp and Lewis, 2023). However, such initiatives often fall short of their promises. The main reason lies in a strategic paradox: on the one hand, their relative autonomy from the ‘core’ public sector organisation enables them to experiment freely; on the other hand, it exposes them to all sorts of risks. These include being easy to shut down and thus exposed to the whim of political cycles (Tõnurist, Kattel and Lember, 2017); failing to shape policy implementation at scale (Cinar, Trott and Simms, 2019); finding considerable difficulties in developing and disseminating their methods beyond their institutional border (Lewis, 2021); and ultimately struggling to embed themselves in the policy process (Blomkamp and Lewis, 2023).

4.2. Pathways towards professionalisation

The previous sub-section identified three bottlenecks against professionalisation of public value delivery:

- the tension between the ‘new ethos of civil service’ and existing public administration paradigms;

- the lack or poor measurement of dynamic capabilities; and

- the siloing of PILs at the fringe of public sector organisations.

Now, we identify three (non-exhaustive) pathways towards professionalisation:

- leadership;

- competency and capability frameworks; and

- communities of practice.

The first pathway towards professionalisation of public value delivery is leadership. In sociology of organisations, leadership is interpreted as the spark behind the institutionalisation of new working practices – or, in other words, the infusion of the organisation with values that reflect a cohesive sense of mission (Selznick, 1957). Within the public sector, leadership can be exerted either or both at a political and administrative level. Either way, it plays a critical role in eliciting the trust of the general public and turning the public sector organisation into a ‘vessel of societal aspiration’ (see also Goodsell, 2001). By doing so, leadership can break the mould of existing routines in the organisation and establish new ways of working – if not streamline the adoption of new tools. Boin and Christensen (2008) model such process of institutionalisation in four ‘design principles’ that effective public leaders can adopt:

- facilitating trial-and-error learning in pursuit of new working practices;

- monitoring emerging practices as they gradually entrench;

- embedding accepted norms in the public sector organisation’s formal rules;

- balancing public sector organisation’s need for identity and adaptation against external disruptions.

Following this framework, Boin, Fahy and ’t Hart (2021) identify 12 global cases of successful leadership-driven institutionalisation – including the BBC, whose legitimacy is identified in the ability of leadership to adapt its traditional mission (“to open the ring of potential speakers wider”) while adapting nimbly to different socio-political eras (p. 103).

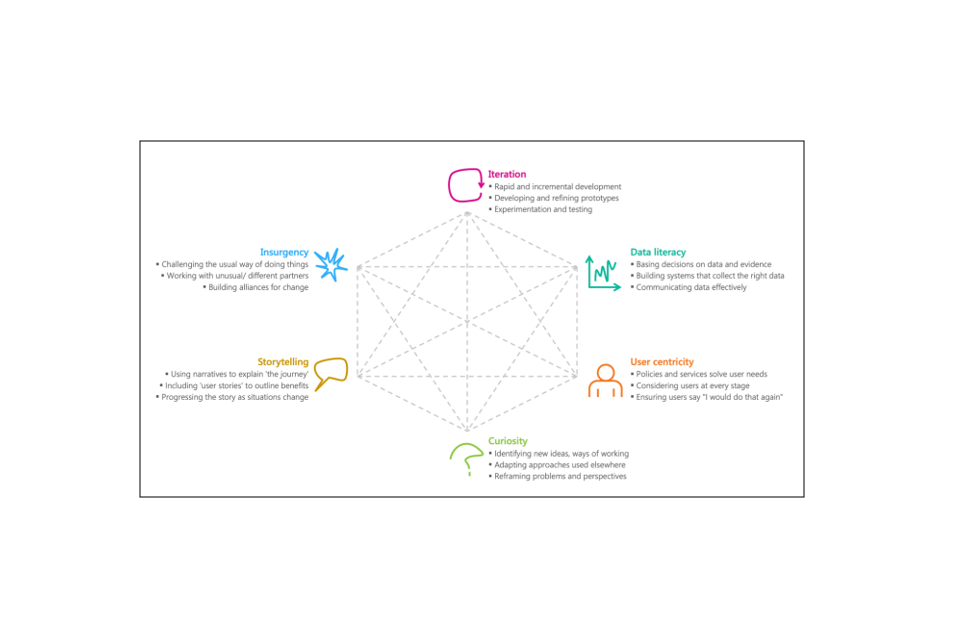

The second pathway towards professionalisation of public value delivery is the development and adoption of competency and capability frameworks within civil service systems. A large majority of OECD countries has established competency frameworks for at least a decade (OECD, 2017). The role of such frameworks is to translate broad ambitions for the tasks to be performed by the public sector into sets of skills, knowledge and behaviours that can be used to assess skills needs and gaps within a public sector organisation; attract and select new human resources; develop new skills among the existing ones; and ensure they are put to use in policy work. The content of such frameworks varies in each country. In the UK, the most recent example is the ‘Policy Profession Standards’ – which identify three pillars mirroring PV’s strategic triangle (strategy; democracy; delivery) and breaks each of them in four components and three levels of expertise (HM Cabinet Office, 2021). Interestingly, public design is not incorporated in any of them but at the higher level of expertise in one component of the ‘strategy’ pillar (i.e. participation and engagement). On the other hand, the latest skills review conducted by the OECD (2017) identifies design as the ‘core’ of one of six skills areas for public sector innovation (i.e. user centricity; see also Figure 12). In general terms, there is still little to no research on the impact of competency and capability frameworks and their renewal on professionalisation and the evolution administrative careers (Veit, 2020). Still, to the degree to which their directives are adopted and embedded within the governance of the Civil Service, they can serve as a useful tool for directing efforts at skills standardisation.

Figure 12. OECD core skills for public sector innovation[footnote 17]

Last, the third pathway we identify towards the greater professionalisation of public value delivery is the development of communities of practice (CoPs). CoPs can be defined as “self-organizing systems [that] share the capacity to create and use organizational knowledge through informal learning and mutual engagement” (Wenger, 2000, p. 3). There is a non-negligible amount of research on the role of CoPs within inter-organisational and cross-sectoral collaboration aimed at the development of public policy – e.g. within the fields of education, health care, international cooperation, industry standards, and environment (Koliba, 2021). This stream of research shows that civil servants are always embedded within implicit CoPs which can be leveraged and actively steered to develop a critical perspective on ongoing policy work; strengthen inter- and intra-organisational networks; forge new connections where needed; as well as foster continuous learning and professional development (pp. 81-82). In the UK, this approach was leveraged by the Government Digital Service (GDS) to streamline the adoption of a user-centred design approach throughout government. The CoP was highlighted as “the invisible bit that enabled the community [of user-centred design] to grow and mature” – pooling together plenty of resources (e.g. via online channels and community blogs) and streamlining collective learning via personal interactions (e.g. via meetups, weekly sessions, talks) (Gleo, Kane and Robertson, 2021). While the dynamics of CoP design and governance are still under-researched, the GDS case highlights their potential for propelling and standardising the adoption of methods and tools across the public sector – thus providing another pathway towards professionalisation.

4.3. Public value through practice-based leadership

Overall, the three pathways help provide a new perspective on the limitations and possibilities of PILs and similar institutions (for example, in-house consultancy services such as Germany’s PD[footnote 18]). On the one hand, PILs are important “creative platforms” in which the working practices of a public sector organisation can be scrutinised and re-designed in order to adapt them to new challenges (Bason, 2023). On the other hand, the pathways described in the previous subsection – i.e. leadership, competency frameworks, and CoPs – constitute strategic alternatives to streamline the adoption of new working practices throughout a public sector organisation – or even the public sector. Notoriously, PILs suffer from the paradox of autonomy: the greater the room for experimentation, the more difficult to distil and embed the learning behind the institutional borders of the lab itself. Against this context, the pathways can play a complementary role: illustrating how PILs can support the diffusion, iteration, and gradual institutionalisation of the methods and tools firstly prototyped by them. We synthesise this insight into an approach to the professionalisation of public value delivery that can be labelled ‘practice-based leadership’. The approach entails three components:

- Public leadership: i.e. the commitment of public management to nurture leadership in the sense previously explored: that is, the infusion of the organisation with values that reflect a cohesive sense of mission (Selznick, 1957). This requires a ‘strategizing’ approach to intra- and inter-organisational collaboration, where the aspirations and capabilities of the public sector organisation seeking to deliver public value are iteratively realigned (Ysa and Greve, 2023).

- Communities of Practice: i.e. the encouragement of self-organising networks where civil servants can create and use an evolving stock of organisational knowledge to develop new working routines and professional norms. This requires involving the ‘frontline’ of the public sector organisation into the adoption of public innovation (Pedersen, Scheller and Thøgersen, 2023).

- Suitable enabling conditions: i.e. the presence of institutional structures conducive to the professionalisation of public value delivery. Public administration research shows that the following conditions play a critical role in effective delivery (Gold, 2014, 2017):

- political backing

- financial resources

- a tightly defined remit.

Together, these components suggest an approach to how public management can foster the rise of new skills within a public sector organisation or across the public sector. On the one hand, public leadership provides direction for civil servants to test, develop, and consolidate new working routines. On the other hand, CoPs provide peer support for civil servants to share practical advice on how to navigate issues related to new working routines. Last, enabling conditions create a safe, resourceful, and focused environment for them to do so (see Box 2 for a successful case study).

Box 2. Case study: Delivering public value at GDS Founded in 2011, the UK’s Government Digital Service (GDS) has become an international gold standard for public digital agencies; it has won awards and praise among its peers, and its blueprint has been copied in many countries (Clarke, 2020). Following a series of high-profile IT failures, in 2011 a report from the UK Parliament highlighted a dearth of IT expertise; a lack of horizontal IT governance; and an excessive reliance on large-scale contracting with a small number of private providers (House of Commons Public Administration Committee, 2011). As a result, GDS was created as a new digital government unit in absolute control of the overall user experience across all digital channels of the public sector and headed by a CEO reporting directly to the Cabinet Secretary. The approach adopted by the new unit relied on the following features (Kattel and Takala, 2021):

- A narrow set of design principles: with the creation of ‘Government Design Principles’, GDS aimed at enabling the development of new working practices not by imposing a one-size-fits-all standard, but by championing a narrow set of key principles focused on a new philosophy of service design and agile software development – including, for example, fast prototyping and the incorporation of evidence from user research.

- A Communities of Practice approach: rather than implementing a complete overhaul of the UK’s digital service single-handedly, GDS ‘stewarded’ the bottom-up formation of self-organised networks that included designers and software engineers across both central government and local authorities. As a complement, GDS actively ‘worked in the open’ – i.e. sharing tools, practices, and open-source software with them.

- Suitable enabling conditions: the recognition of past failures and the urgency for new, radical action allowed GDS to perform its function in a favourable environment – i.e. in proximity of political power (CEO reporting to the Cabinet Secretary), considerable operative freedom in recruitment and strategy development, and a tight, well-defined mission: i.e. revamping UK’s digital presence.

In the last decade, GDS dramatically improved UK citizens’ user experience (e.g. through the unified gov.uk webpage); successfully reshaped existing digital procurement practices in the direction of a dramatically greater reliance on small and medium-sized enterprises; and helped the government develop a new career path around digital, data and technology (DDaT). As a result, the case of GDS illustrates a story of success not just in terms of public value delivery; but also, in terms of professionalisation of public value delivery.

To conclude, this section of the literature review aimed at making sense of the notion of public value; how it can be measured; what its distinctive features are in the current operating context of the public sector; and how its delivery can be professionalised. The purpose of addressing the above was to provide greater clarity on how public design (as discussed in Section 1) can contribute to the creation of public value. As Andrew Knight announced in launching the initiative to which this literature review is contributing, civil servants engaged with public design must develop “a deliberate focus on crystallising and responding to intent [i.e. the change that a government seeks]” and be “systems thinkers to respond to complex environments” (Knight, 2023). We hope that this section has contributed to help them advance this pursuit by:

- Highlighting the double-sided nature of public value as outcome and as process.

- Illustrating the complementarity between ‘VfM’ and heuristic measures of public value.

- Identifying wisdom, imagination, collaboration, and humility as the distinctive features of public value delivery in the 21st century – i.e. a ‘new ethos of civil service’.

- Showing how public value delivery can be professionalised by means of a ‘practice-based leadership’ approach based on a combination of ‘top-down’ public leadership, ‘bottom-up’ Communities of Practice, and suitable enabling conditions.

5. Bibliography

Alford, J., et al. (2017). Ventures in public value management: introduction to the symposium. Public Management Review, 19(5), pp. 589–604. Available at: Ventures in public value management: introduction to the symposium.

Alford, J. and O’Flynn, J. (2009). Making Sense of Public Value: Concepts, Critiques and Emergent Meanings. International Journal of Public Administration, 32(3–4), pp. 171–191. Available at: Making Sense of Public Value: Concepts, Critiques and Emergent Meanings.