Public Design Evidence Review: Literature Review Paper 1 - Public Design (HTML)

Updated 21 August 2025

Commissioned by the Policy Design Community

Authors:

Lucy Kimbell, Professor of Contemporary Design Practices, Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts London and Director, Fieldstudio Design Ltd

Charlie Mealings, Doctoral Candidate and Adjunct Lecturer, Department of Political Economy, Kings College London

Catherine Durose, Professor of Public Policy and Co-Director of the Heseltine Institute for Public Policy, Practice and Place at the University of Liverpool

Liz Richardson, Professor of Public Administration in the Department of Politics, University of Manchester

Rainer Kattel, Deputy Director and Professor of Innovation and Governance, Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose, University College London

Iacopo Gronchi, Doctoral Candidate, Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose, University College London

How to cite:

Cabinet Office (2025) Public Design Evidence Review: Literature Review Paper 1 – Public Design.

Background

This document is the first of three literature reviews commissioned by the cross-government Policy Design Community, written by an interdisciplinary team of academics. It provides an overview of design: its competencies, outcomes, integration into government, policymaking and public services, and distinctions from commercial design. It also discusses the conditions required for effective implementation.

The wider project was commissioned as a non-exhaustive exploration of the relationship between public design and public value. It was conducted within rapid timeframes and prioritised cross-disciplinary working. The authors began drafting in September 2023, finalised the drafts in March 2024, and published in July 2025.

‘Literature Review Paper 2 - Public Value’[footnote 1] and ‘Literature Review 3 - Public Design and Public Value’[footnote 2] are published alongside ‘Literature Review Paper 1 – Public Design’ as part of the Public Design Evidence Review.

Executive Summary

Context:

All governments face challenges of a changing social context, system complexities and barriers to delivery that requires innovation. There is growing evidence that practices, methods, skills and people associated with ‘design’ found across government, business and civil society have untapped potential to help address such challenges and contribute to the creation of public value. The term ‘design’ encompasses a range of activities and skills, including a human-centred focus, prototyping and co-creation. These inform diverse government activities: the creation of digital interfaces, the design of government services, the development and testing of policy proposals, and the implementation of interventions. However, the varied range of methods, skills and personnel involved in design, and differences in their use in government and public policy, make the term confusing. There is a need to distinguish design from other approaches, to understand when it adds value, to specify the outcomes it leads to in the public sector and government, and to clarify how public design differs from commercial design.

Method:

In response to questions set by the Civil Service, we reviewed and synthesised literature identified through a targeted, multi-vocal search including ‘grey’ and academic publications in studies of design, service design, design management, healthcare innovation, and public policy.

Results:

We noted long-standing debates about how design is defined. We identified seven characteristic ‘practices’ associated with design:

- Understanding people’s experiences of and relations to systems.

- Conceiving of and generating ideas.

- Visualising, materialising and giving form to ideas.

- Integrating and synthesising perspectives, ideas and information.

- Enabling and facilitating co-creation and citizen involvement in design processes.

- Enabling and facilitating multi-disciplinary and cross-organisational collaboration in design processes.

- Practically exploring, iterating and experimenting with potential options.

In terms of outcomes achieved through applying design practices, we noted that the evidence is positive but varied, and rooted in different research traditions, which makes it hard to identify specific pathways through which practices lead to particular outcomes. We found that claims of outcomes achieved through applying design practices are often situated in particular framings (e.g. organisational innovation) or specific contexts (e.g. healthcare), from which it is hard to generalise. We found a lack of clarity about how ‘public’ design might be distinguished from ‘commercial’ design. We suggested seeing the former as a type of democratic practice, with different purposes and accountabilities, and less attachment to novelty, with respect to the latter.

Noting the spread of design practices within and across the UK government in the past two decades, we reviewed selected sub-fields or ‘types’ of design in government, highlighting how the practices of design take particular forms in relation to contexts, media and devices, with distinct histories and research debates. All maintain a focus on people’s lived experience as they relate to or interact with designed things. For some areas of design, the ‘system’ or social context or relations to a place is an area of design inquiry that designers recognise may be changed (e.g. through introducing a new object or interaction into it), or indeed an area for transformative change (e.g. to design ‘for’ future sustainability). Further, all of these fields are impacted by technologies, both in terms of what is being designed (e.g. the design of a service journey might include in-person as well as digital touchpoints; packaging may include links to online media prompting or enabling action through embedded QR codes or hashtags) and how design is carried out, both individually and collaboratively (e.g. through the use of digital tools, data analytics and automation).

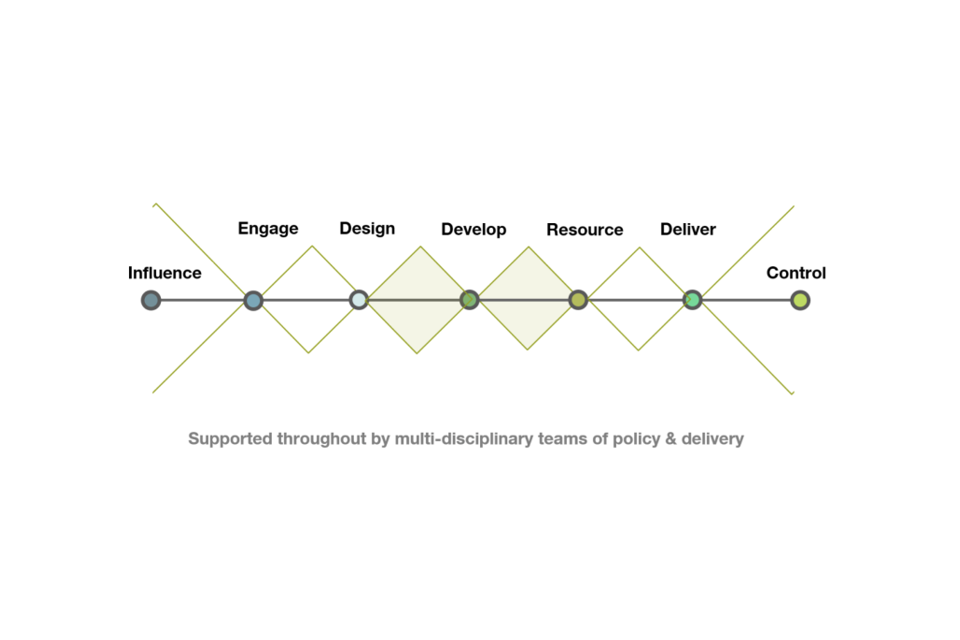

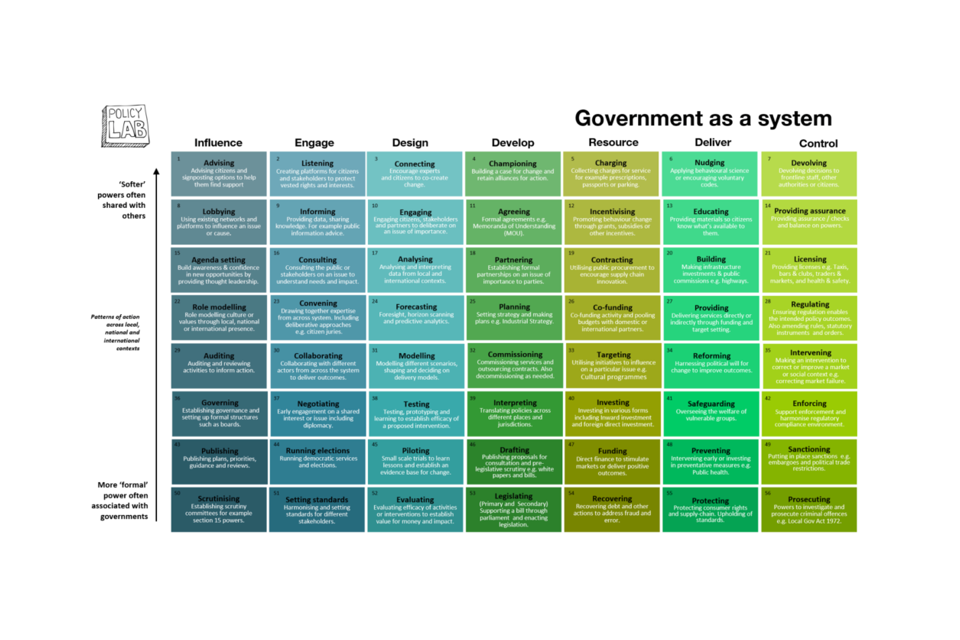

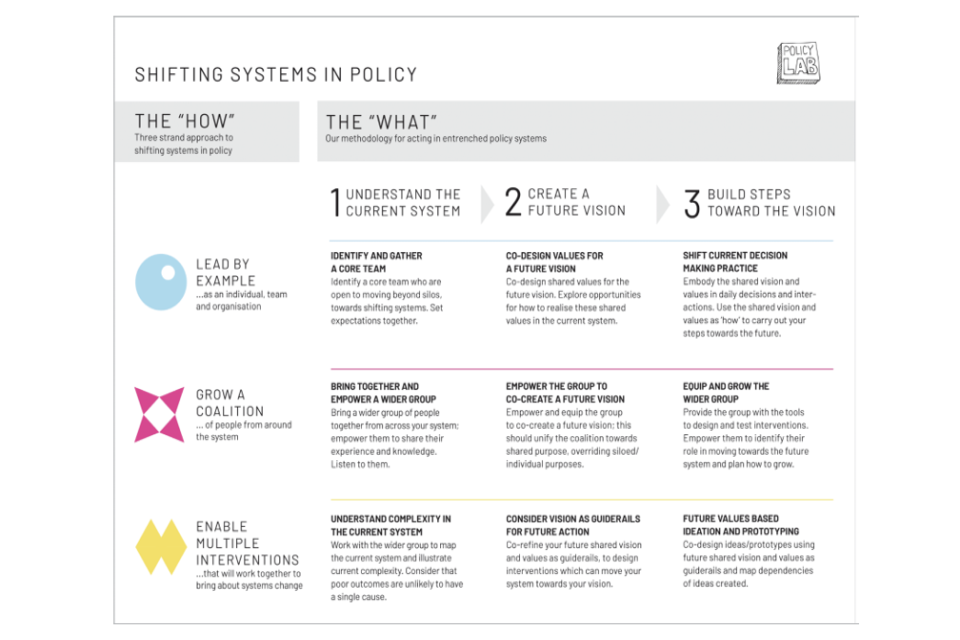

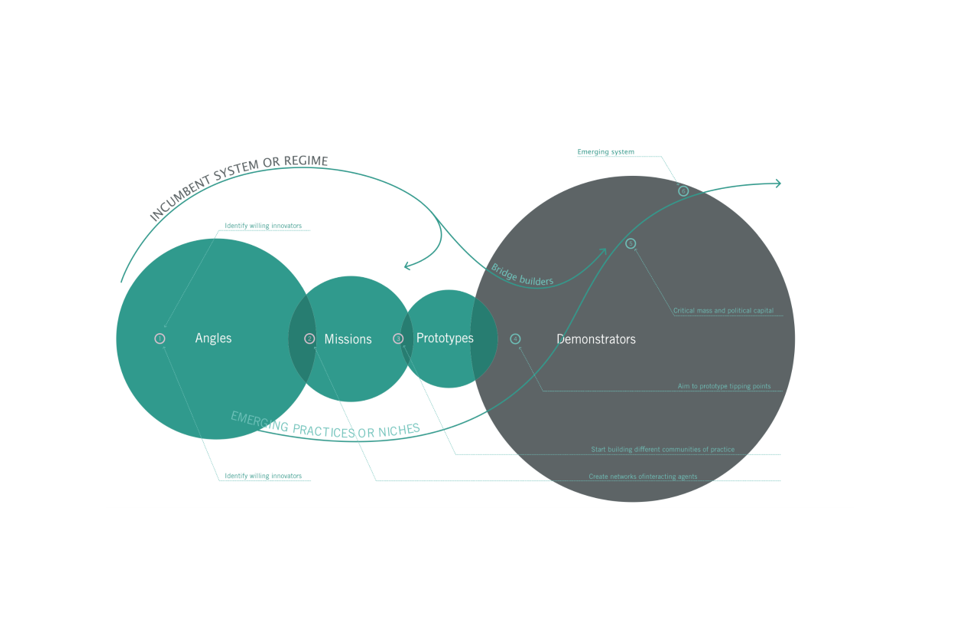

In terms of competences for design, we found frameworks which sometimes did not distinguish carefully between skills, competences and capabilities, and some which focused on specific types of design, such as user experience or service design. We examined the integration of design in government. We found that although there are academic studies that account for or critically assess how, and under what conditions, design is integrated into public service delivery, there are few examining design in policy development, and very few specific to the UK. Among frameworks and models developed by government policy labs, design teams and consultancies from the UK and internationally, there are examples of efforts to conceptualise purposes, activities and types of design in government, at different scales, and across different systems or areas of policy. Such frameworks have shifted away from linear processes towards recognising complexity and interdependencies of systems, with which design practices can play useful practical roles.

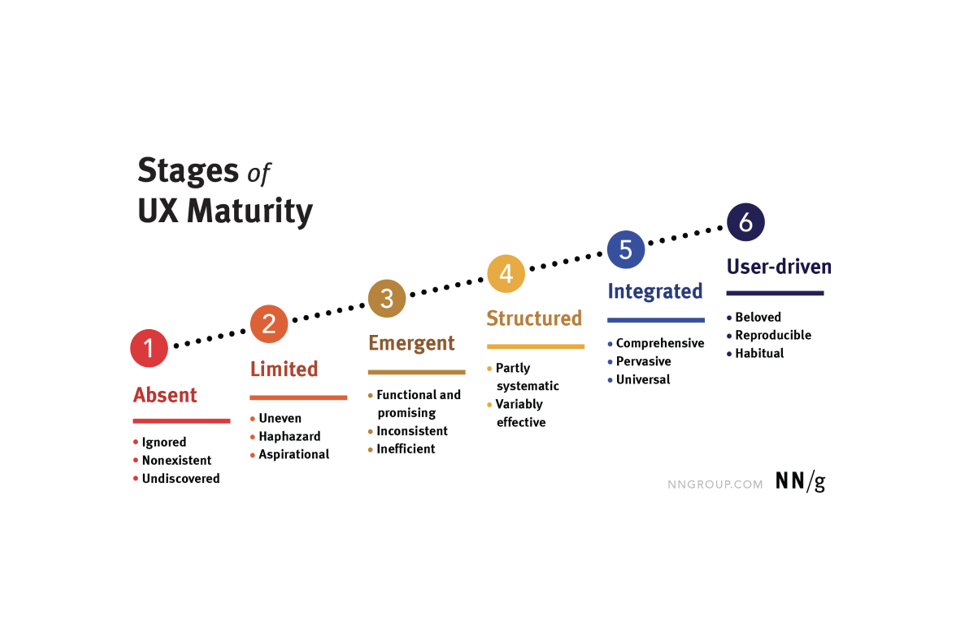

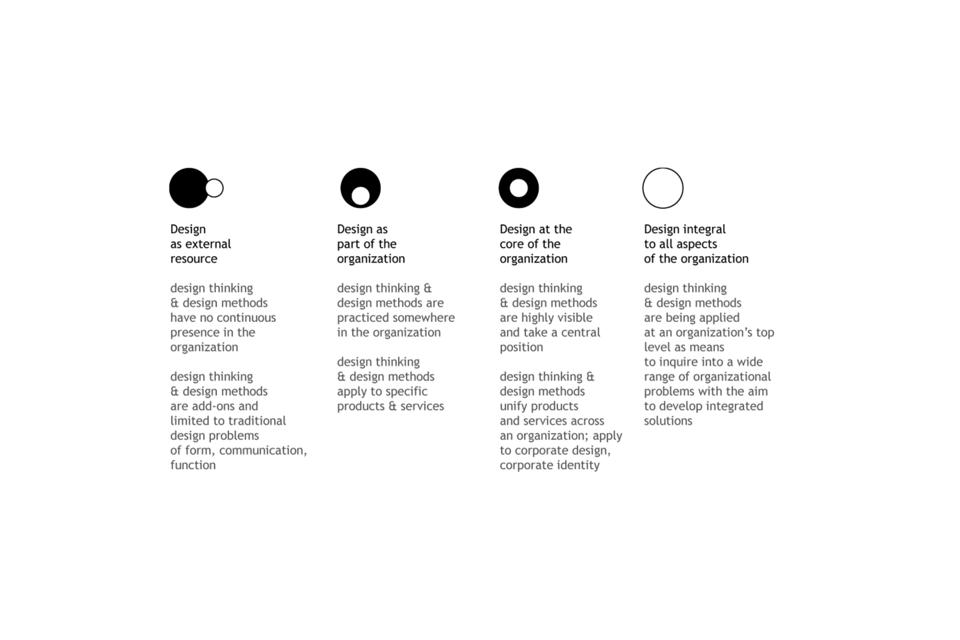

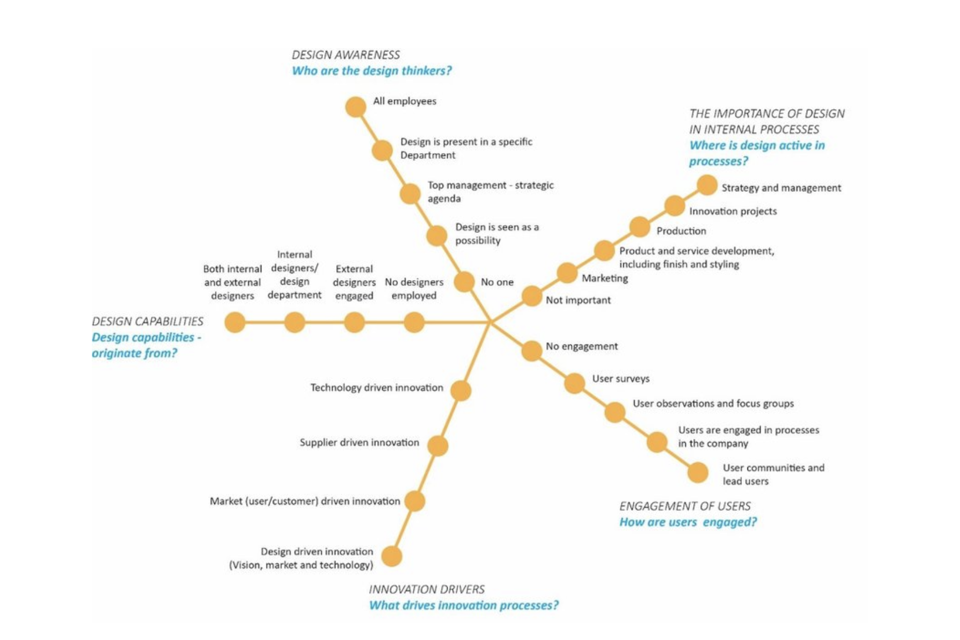

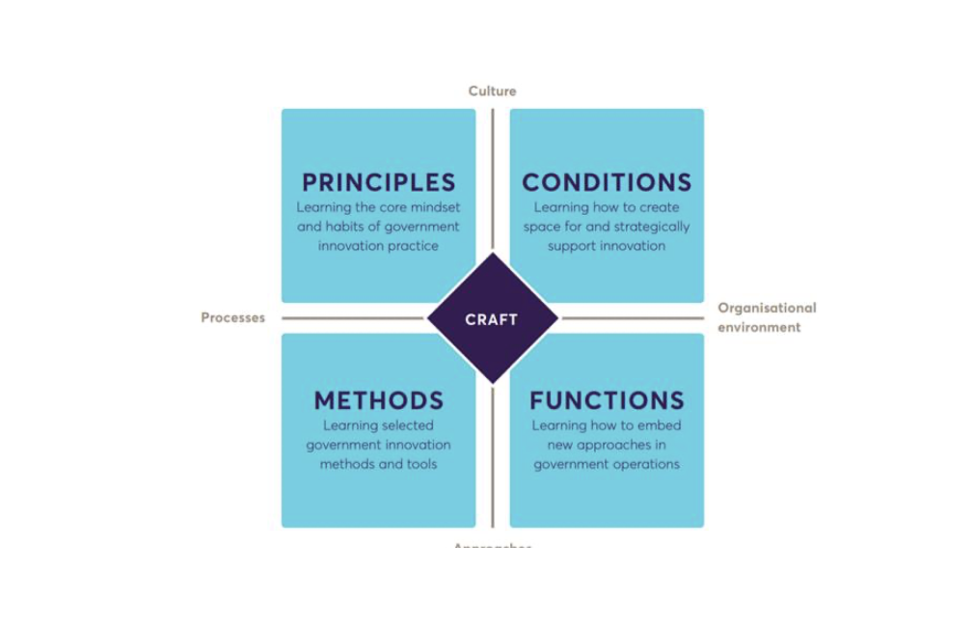

We found that maturity and enabling conditions for building and maturing design capabilities are understood as dependent on organisational ‘absorptive’ capacities or underlying taken-for-granted ‘logics’ or narratives about how things are done. Such conditions include: awareness, availability of resources and expertise, existence of narratives and leadership to provide legitimacy, and formal structures. Recent studies suggest that, rather than a simple ‘additive’ model in which design capabilities simply join existing teams, functions and skills, building up design capacity is aligned with wider narratives about innovation or agendas for doing things differently.

1. Defining public design

What are the differences in outcomes and practice between commercial design and public design?

1.1 Introduction: Defining design

To the extent that they are both interested in innovation, improvement and value creation, both commercial and public organisations have an imperative to design. Fundamentally and in general, design can be understood as concerned with the creation of new ‘forms’ of value, or new forms that have value. But defining design is surprisingly hard. Some definitions focus on the orientation of design towards change, innovation or transformation. Some emphasise characteristics, qualities or activities, claiming that these are distinctive. Others focus on the objects produced by designers, such as services or products. And some focus on professionals who think of their work as ‘capital-D’ design, whereas other definitions seem more open to anyone designing anything: a workshop, a strategy, an organisation. In this brief overview, we bring together some of the main perspectives summarising design, from which we aim to understand what ‘public’ design might mean.

As an initial working definition, it might be said that public design is a type of professional expertise, with accompanying skills, processes, methods and tools oriented to public matters and public contexts – in particular, activities undertaken on behalf of citizens by government and other actors. In contrast, commercial design might be seen as oriented to achieving business purposes, such as increasing shareholder value, market share or brand identification – or, increasingly, goals connected to corporate social responsibility (CSR), such as achieving net zero. Evidently, commercial organisations are also constrained by a different calculus of risks than public organisations, which are funded, structured, staffed and legitimised in an entirely different manner.

It therefore follows that the practices, logics, methods and cultures of commercial and public design also diverge, even if the techniques might appear largely the same. Consider, for example, the design of two services: one related to assessing benefits entitlement and another to ascertain a customer’s suitability for taking up a mortgage. Insofar as both services seek to assess financial status and eligibility, there are clear similarities between the tasks.

However, each service has a different purpose, set of actors involved, and surrounding narratives and organisational capabilities. In the former case, a policy team in a government department might develop the specification, with the service delivered by a contractor; in the latter, the service might be developed and run by a financial services business, which is regularly scrutinised by investors about its profitability or stability or growth as a firm. Both services might aim to be ‘human-centred’ in their design and delivery, and both may result from iterative development, including understanding user perspectives and the use of prototyping. But the possibilities, constraints and consequences of the service design are different.

Nevertheless, commercial and public design are connected because the public and private sectors shape each other. Government policy, and public institutions more broadly, are tied up with commercial design, for example through regulation. In the case of the mortgage service, government directly shapes commercial design through oversight and regulation of financial institutions offering mortgages, and indirectly as financial institutions set mortgage interest rates in response to government activity and public debates about the desirability and affordability of mortgages. In a polity that puts value on economic stability and opportunities for people to own their own homes, commercial design in the financial services sector is unavoidably implicated with the design of public policy, services and institutions. A well-designed, customer-centric service for a mortgage application makes good commercial sense in a competitive and highly regulated sector. Similarly, if we take other sectors in which we can find commercial design, such as retail, construction or hospitality (on the high street, or via social media apps or websites), even a brief inspection of each reveals that ‘commercial’ priorities informing design are also linked to and shaped by government activity and wider public policy debates such as ‘sustainability’, ‘levelling up’ or ‘open data’. In short, differences between public design and commercial design are not always clear cut.

The argument made here is that despite such difficulties there is value in making such a distinction. This review will argue that there are significant differences in purposes and enabling conditions shaping capabilities and practices in public design and commercial design, which have implications for the effectiveness, operationalisation and accountabilities of each, and hence for resulting outcomes.

In what follows, this literature review aims to provide clarity about the processes and outcomes associated with public design (this section); specify different types of design in government (Section 2); characterise how design is understood to fit into policy and public service delivery (Section 3); define design skills, competences and capabilities (Section 4); and summarise ways to assess maturity in design and the enabling conditions that sustain and mobilise the distinctive practices and outcomes associated with design (Section 5). This structure uses headings associated with questions from the commission from the UK Civil Service Policy Design Community that led to this piece of work.

To do this, we combine and synthesise literatures from a range of sources. Further details on our methodology are provided in the Appendix, but in summary the approach taken is a targeted, multivocal literature review. This includes peer-reviewed academic publications in studies of design, service design, design management, healthcare innovation, organisation and public policy, as well as important contributions from practice and discussions among several UK and international professionals and organisations.

The result is the clarification of concepts and working definitions that aim to be coherent enough to be operationally useful in the context of the UK government, while also acknowledging ongoing debates about developments in government and public policy (e.g. Mazzucato, 2014; Hood and Dixon, 2015; Durose and Richardson, 2016; Saward, 2021; Collier and Gruendel, 2022; Kattel et al, 2023) illuminating the structuring conditions shaping and sustaining design as a professional capability in government and the public sector. Characterising public design will aid understanding about when, where and under what conditions to invest in building capabilities in government and the public sector, and what likely consequences might result. To achieve this, we start with more general definitions of design, from which we will build distinctions between public and commercial design.

There are long-standing and ongoing debates in studies of design that seek to define and characterise the field, including discussion about the extent of differences between design in commercial contexts and design for public outcomes. Rather than reproducing those here, we seek to integrate a range of well-established sources as well as practitioner perspectives that articulate what makes design distinctive to underpin a working definition of public design (e.g. Buchanan, 1992; Michlewski, 2008; Lawson and Dorst, 2009; Bason, 2010; Cooper et al, 2011; Hill, 2012; Design Commission, 2013; Bason, 2017; Clark and Craft, 2018; Elsbach and Stigliani, 2018; Micheli et al, 2019; Resnick, 2019; Liedtka, 2020; Knight et al, 2020; Bason, 2021; Kimbell et al, 2023; Hill, 2022).

While keeping within the scope and purpose of this literature review, we briefly highlight discussion in research literatures about design that analyses the potential and consequences of the capacities of design. One way of reading this is to discern a debate between advocates of the view that design is ‘problem-solving’ versus those who see design as generative, going beyond existing understandings, framings and possibilities. A widely cited example of the former position is from Nobel laureate Herbert Simon (1996, p. 111), who argues: “Everyone designs who devises courses of action aimed at changing existing situations into preferred ones.” Similarly, the Design Council defines design as “what happens when you use creativity to solve problems” (Design Council, 2024a). This trajectory for design theory foregrounded design as a systematic procedure, in response to which Donald Schön (1983) and many others offered accounts of designing as situated, pragmatic and reflexive, a debate which has its own history and nuances (see for example Chua, 2009).

Other explanations highlight other aspects of design. For example, philosopher Glenn Parsons (2016, p11) offers a careful definition highlighting intentionality and originality: “Design is the intentional solution of a problem, by the creation of plans for a new sort of thing, where the plans would not be immediately seen, by a reasonable person, as an inadequate solution.” However, from the perspective of many people who understand their professional work as design, what is lost from these definitions is the form-giving materiality, aesthetics and visuality commonly associated with design practice – where the intentions and plans are manifest in the world in the form of products, digital interfaces or buildings. Other accounts or theories of design see it as generative, arguing that its practices serve to expand the space of possibilities (e.g. Hatchuel, 2001; LeMasson et al, 2010), go beyond existing framings (e.g. Dorst 2015), or envision and enable transformation (e.g. Fry, 2009; Escobar, 2018; Akama et al, 2020). Such distinctions play out in this paper.

This summary acknowledges both the extensive variety of ways of understanding design and points to the broader context in which design – as a type of professional expertise with routinised ‘practices’[footnote 3], including skills, methods, embodied knowledge and ways of working – has become increasingly visible and embedded into organisations across the public and private sectors, as well as in citizen-led initiatives. First, we identify seven distinctive practices associated with design, synthesised from grey and academic literatures, and then turn to discussing outcomes.

1.2 Design practice 1: Understanding people’s experiences of and relations to systems

Design practices highlight the relations between people, things, organisations, places and communities, people’s use of objects, and experiences of organisational and technological systems and infrastructures.

Because both commercial and public design are oriented to the production of forms that will be experienced by the people they are meant to serve – used, adapted, interacted with – design takes human experience as its primary analytical focus and source of evidence. Experience is a rich and heterogeneous source of data, and thus design often employs qualitative methods of research to generate rich depictions of subjects and their situated experiences (e.g. ethnographic interviews or fieldwork). But, unlike other traditions of qualitative social inquiry, design leans more strongly into making conjectural representations of future experiences (e.g. role-playing, storytelling, workshops) to construct useful propositions, solutions and framings that will generate meaning for the people using or interacting with them (Krippendorff, 2006; Verganti, 2007). In the literature and in practice this focus on experience is sometimes termed ‘human-centred’, ‘experience-based’ or ‘empathic’ design.

But don’t other forms of social inquiry take an interest in experiences? A few do, and this accounts for design’s close relationship with anthropology and use of ethnographic techniques. When design practices focus on people’s experiences, it is in relation to ‘systems’ or social phenomena, whether these are digital platforms, government services, public administrations, environments or local communities, a perspective increasingly evident in practice and research (e.g. Conway et al, 2017; Ceschin and Gaziulusoy, 2020: Hill, 2022; Design Council, 2022; Dixon, 2023). It is the connecting of these former or current experiences with potential or future arrangements that design foregrounds. A great deal of early scholarship on the relationship between experience and design comes from human-computer interaction (HCI) (see more on types of design below in Section 3), but in a contemporary world so dense with artificial and interconnected things it is hard to find practices of design that do not pay significant attention to human experience. The design of airports (Harrison et al., 2012), for example, is essentially concerned with people’s experiences of them, including attending to the built environment, operational processes, technological systems and data infrastructures which are embedded in them.

Public designers are concerned with how citizens experience public services (e.g. Trischler and Scott, 2016), public spaces (e.g. Butler and Bowlby, 1997) and public policies (e.g. Bason, 2014) and the infrastructures they rely on. Examples include road users’ experiences of A&E departments (Franzen et al. 2008) or newly certified refugees’ experiences of their host countries (Almohamed et al. 2018). Starting with the lens of experience, rather than analysing a public policy issue or service from the perspective of a government department, leads to a shift in emphasis towards life events as people go through and make sense of them and away from the processes prioritised by organisations.

While contemporary design in general foregrounds experiences, recent research and practice has begun to challenge, or de-centre, this emphasis on the subjectivity of humans qua ‘users’ or ‘citizens’ and propose a broader orientation to ‘relations’, as in people’s relations to other people, objects, places, organisations and ecologies. Rooted in calls for social justice and critical thinking, researchers and practitioners are raising questions about whose experience matters. For example, some researchers question the Eurocentric, extractive logics which obscure or marginalise some peoples and worlds during designing, instead proposing ‘pluriversal’ approaches to design (Escobar, 2018; Leitão, 2023). A second, related development is ‘more-than-human’ perspectives (Forlano, 2017; Akama et al, 2020), which open up understandings and transformation of ‘systems’ to a broad range of forms of life, including animals and plants, but also recognising the non-human agency of algorithms and robotic systems.

The operationalisation of this emphasis on experience and relations is often through two interrelated tasks within design. The design principles, methods and job families associated with the Government Digital Service are a good example of these. The first is researching ‘user’ experiences and people’s relations with other people, things, places and communities, to understand the situated or lived perspectives that people from the relevant target group have in relation to the current public policy issue or system. The second is mobilising insights about these experiences throughout the design process to result in experience-based designs, often resulting in changed relations between people, things, places and communities. Hence the pairing of two job roles common in digital design: ‘user experience researcher’ and ‘experience designer’. Social and ‘user experience’ researchers, including anthropologists and sociologists, have available a wide range of methods to research experience – alongside activist, community and advocacy organisations, which also foreground lived experience – through approaches that can be qualitative or quantitative. Within contemporary design practice, ethnographically inspired qualitative research approaches are commonly used to rapidly understand and articulate experience and make it available for designing services.

1.3 Design practice 2: Conceiving of and generating ideas

Design practices conceive of and generate proposals or visions for new products, interactions, services, environments and strategic changes.

Policymaking, problem-solving and decision-making practices in government and businesses rely on evidence in order to make proposals or take action. Policy aims to be justified with a strong basis in evidence. This is what it means to say policymaking is rationalistic: that decision-makers have good reasons for action, and this is normally taken to be a good thing. However, as situations increase in complexity – more actors, interests, constraints and types of expertise – it becomes less likely that good solutions will flow logically from the accrual and analysis of more and more evidence. Design abandons the hope that further analysis will render tricky problems logically soluble, and puts a stronger emphasis on generating and creating solutions, in order to continue exploring the situation or problem. Design practices are often described as ‘abductive’, that is, they rely more heavily on conjecture and more gently on inference to generate and assess actions, propositions and solutions. In practice, this is why the practices of design are so strongly oriented to producing novel framings and suggestions, challenging assumptions and orthodoxies, and opening up pluralist perspectives. This is where public design is often found in tension with its situated institution: governmental structures seek justification for policy action, whereas design practices are oriented to its discovery.

This emphasis on creativity and generation plays out through different methods and techniques during design processes. For example, in a comparative study of the use of design across 15 cases in a range of public institutions in five countries, Bason (2017, p.309) identified three core uses of design, the first of which was predominant: exploring the problem space; generating alternative scenarios; and enacting new practices. Creativity is a core competency and outcome in design, and one that has been the subject of extensive experimental research to demonstrate the efficacy of various design practices in improving creativity and quality of idea generation, including disciplinary diversity, divergent thinking, goal-setting, visualisation, sketching, prior group interaction, surprise, and non-functional design requirements (e.g. Flager et al, 2014; Lee and Ostwald, 2022; Ou et al, 2023). Here, a futures-orientation is often implicitly, and sometimes explicitly, part of design practice. When made explicit, a futures orientation, for example in an EU project on blockchain (Pólvora and Nascimento, 2021), enabled the building of collective visions and stimulated ‘anticipatory’ governance. Such generative and creative capacities can sometimes serve to challenge existing assumptions, worldviews and ways of doing things, which can be uncomfortable within public contexts (Kimbell et al, 2023).

1.4 Design practice 3: Visualising, materialising and giving form to ideas

Design practices place a strong emphasis on making ideas visible and tangible and giving form to potential changes to products, interactions, services or places.

Different ways of representing understandings of the world around us offer different opportunities for discovery, and different opportunities for individuals and teams to venture, modify and play with different conjectures. Numbers allow for precise specification and comparison of quantities and values – graphs even more so. Written text provides structure and permanent storage for human meaning in a (mostly) standardised format, which is easily transferable, reproducible and analysable, and can be verbalised on demand. In contexts where standard assumptions and meanings are helpful and uncontroversial, where the precision and predictability of statements is paramount, where ambiguity leads to error, and where everything is recorded for posterity (accountability) textual and numerary languages are best.

There are many reasons for this emphasis on visualisation and materialisation, but in general these practices are helpful in the production of novel and emergent meanings, and provide equitable terms for giving form to ideas and for communication between diverse participants. Especially in the social domain, sometimes relationships, systems and scenarios are easier sketched, mapped or performed than explained. Visual media that appear unfinished open up interpretation and allow for addition, expansion and synchronous collaboration in a way that a text in a report does not. Not everyone can read a regression table or use the conceptual vocabulary of urban planning, but pretty much everyone can tell stories, sketch (at least crudely), and discuss or organise photographs. Sketches are easily edited, revised and adapted. Not all feelings and perspectives are easily put into words, but storyboards and personas may serve to communicate important aspects of experience. Whilst they might involve symbols with standardised meanings, sketches, models, maps, diagrams, portraits and storyboards allow much greater scope for participants to generate their own meanings.

In this way, visualising and materialising are inclusive and equitable practices of communication in diverse settings, and are conducive to ambiguity, re-interpretation, rapid or simultaneous collaboration, and speculation or ideation. Objects such as sketches, mock-ups and prototypes play important roles in cross-disciplinary collaboration (Nicolini et al, 2011), enabling participants to work across different types of boundaries, and providing a way to engage across domains of expertise. Such practices can bring into view perspectives that are marginalised or ignored.

1.5 Design practice 4: Integrating and synthesising perspectives, ideas and information

Design practices facilitate the synthesising, integration and sense-making between varied forms of knowledge, positions and perspectives in relation to a situation.

One definition of design suggests it has no determinate subject matter of its own, such as the structure of human DNA (associated with the field of genomics) or the scarcity of resources and associated behaviour (as in the field of economics) (Buchanan, 1992). Instead, design might be introduced to either of these fields, for example, in the design of gene therapies or of government auctions for the commercial rights to a telecommunication bandwidth. Increasingly, public policy problems refuse to respect these disciplinary, as well as sectoral, jurisdictional, public-private, value-factual and domain- or issue-area boundaries. This is articulated imperfectly but frequently through the notion of ‘wicked problems’ (Rittel and Webber, 1973). When saying design is integrative, this suggests it has the capability to bring these considerations into coherence. The modern concept of a professional designer emerged concurrently with industrialisation and the need for a new kind of professional who could manage the complex calculus of economic, technological, stylistic and organisational requirements involved in successfully bringing a new product to market (Heskett, 2005). Though the work of a public designer is quite different from a 19th century ‘draughtsman’, a practice of integrating varied knowledges, considerations and constraints remains integral.

Because design involves the integration of these diverse inputs, which are often incommensurate, synthesising is a related competency. In carrying out sense-making, designers typically use visual, creative and material approaches rooted in practical forms of knowledge production to synthesise different information and perspectives, and they engage others in so doing (Rylander Eklund et al, 2022). Analysis can be backward looking, examining and identifying ‘problems’ in how things are at present from different perspectives, to be addressed through (re)design. It can also be anticipatory, by defining ‘opportunities’ for design and speculating about future possibilities in visual or material form (e.g. Buehring and Liedtka, 2018; Comi and Whyte, 2018; Candy and Kornet, 2019). Different kinds of research are routinely carried out during a design process, such as: reviewing evidence; examining existing designs; exploring new materials; analysing errors, waste or intended outcomes not being achieved; and seeking to access the lived experiences of intended users or beneficiaries of a proposed design and their broader relations to other people, things, places, organisations and ecologies. But at the end of analytical activities, especially in the case of complex public problems, where the subjects and inputs under analysis are diverse and incommensurate, one possible result is incoherence. This is one reason for the growing interest in ‘evidence synthesis’ in public policy, with a network of organisations, initiatives, training and toolkits advocating, developing and assessing methods to carry out evidence synthesis to translate research into policy while also enabling intervention and addressing system complexity (e.g. Fleming et al, 2019; Boaz et al, 2024).

In this context, the everyday design practice of synthesising varied evidence and sources to produce new frames, problem statements, opportunities, proposals or prototypes in the context of a specific situation or issue is of interest in public design. Studies of expert designers emphasise the active synthesising work designers carry out in generating and iterating ‘frames’, through which an issue or situation is understood, and solutions are generated and developed. Dorst (2015) argued for framing associated with design as being an important requirement for innovation. The term ‘re-framing’ is widely used across contemporary practice, recognising the conceptual and cognitive work inherent in design. For example, in an analysis of five case studies of public and social innovation, Van der Bijl-Brouwer (2019) articulated framing as an important expertise in the public and government sectors, in order to reveal evolving, non-linear, emergent patterns and drivers of societal or public problems.

1.6 Design practice 5: Enabling and facilitating co-creation and citizen involvement in design processes

Design practices engage, facilitate or are led by stakeholders to understand situations, explore possibilities, and develop, test and assess options.

Because of the central role played by experiences in design, it follows that another key characteristic of public design is engaging and including bearers of those experiences in design processes. It is common in other forms of social inquiry (e.g. social science), and in policymaking and governance, to include or engage with external stakeholders, so it is worth explaining how design handles this differently.

To the extent that participatory design practices ask participants to generate, create, and synthesise, rather than just offer insight into processes and outcomes, participants in public design are directly implicated in the co-creation of potential outcomes and hence of (future) public value. This is both an epistemic and ethical commitment common in design in the tradition of Participatory Design (often now called ‘co-design’), which takes the politics of design processes as its central focus (Simonsen and Robertson, 2012). Rooted in Scandinavian traditions of workplace democracy, researchers in Participatory Design made the political proposal that people who are the intended future users of a product, service or software tool are entitled to be meaningfully involved in designing it, and, concurrently, that for them to be so is conducive to better design.

The first wave of Participatory Design conceptualised a future designed thing as a discursive object, adopting the concept of ‘language games’ to account for the interactions involved in bringing a new software design into being (Ehn, 1988). More recent design-oriented research in this tradition borrowed terms from social studies of science and technology to recognise the politics of the social arrangements brought into being during design (Binder et al, 2011) and the use of design to enable the formation of publics for social ends (DiSalvo, 2022). However other researchers have critiqued such participatory designing as performative rather than actual (von Busch and Palmås, 2023). Other researchers have pointed to the lack of serious discussion of inequalities in design processes and outcomes (e.g. Sloane, 2017). Alongside participatory design, the field of inclusive design developed to make the case that designing, and the resulting designs, should include stakeholders whose needs and perspectives might be marginalised. While some researchers focus on abilities and ageing, others ask if ‘inclusive design’ is more appropriately tied to social justice than to models of disability (Kille-Spekter and Nickpour, 2022). A study of six examples of co-design in the public sector saw the benefit of using this approach as shifting public service design away from an expert-driven process towards enabling users as active and equal contributors of ideas (Trischler et al, 2019). This brief review of recent literature highlights the fact that, far from being a sticking plaster to address a perceived democratic deficit, co-design itself is a complex area of research and practice, requiring understanding and reflection in its application.

While there are many forms of commercial design that hold an authentic commitment to the epistemic claim that meaningful user participation leads to good design processes, it is less clear whether, or perhaps when, commercial designers accept the corresponding ethical claim that users ought to participate meaningfully in the design of forms that affect their own lives. In a democratic context, the ethical basis on which one might take citizen or stakeholder participation to be an integral part of public design is more obvious. Moreover, deliberative, participatory and citizen-centred approaches to democracy experienced a major renaissance in parallel to the development of Participatory Design and design theory more broadly (and as a consequence of similar intellectual currents) (Bächtiger et al. 2019; Bowman and Rehg, 1997; Dryzek, 2000; Guttman and Thompson, 1996; Pateman, 1970). Deliberative democracy is today the predominant school in contemporary democratic theory and under the label of ‘democratic innovation’ has become a self-standing industry and professional practice (Elstub and Escobar, 2019).

1.7 Design practice 6: Enabling and facilitating multi-disciplinary and cross-organisational collaboration in design processes

Design practices engage, facilitate or enable working across organisational and team boundaries to understand situations, explore possibilities, and develop, test and assess options.

Contemporary designers routinely play roles in facilitating and mediating discussions and collaboration across teams, disciplines or organisations (Napier and Wada, 2016). In contexts of multi-stakeholder collaboration, design expertise in facilitation can aid integration of expertise and perspectives and foster co-creative emergence among participants (Aguirre et al, 2017). Such facilitation work requires careful attunement to the politics of facilitation and integration. For example, in a study of design in relation to transitions to sustainable futures in Australia, Gaziulusoy and Ryan (2017) found that design expertise played a dialogical role, enabling the envisioning of desirable futures, as well as helping to articulate the diverse politics embedded in future societal visions. There is also experimental research that suggests disciplinary diversity and prior group interaction have a positive effect on peoples’ capacity for idea generation and creativity (Coelho and Vieira, 2018; Ou, Goldschmidt and Erez, 2023).

1.8 Design practice 7: Practically exploring, iterating and experimenting with potential options

Design practices proceed through iterative processes of exploring and assessing issues or problems, and generating and testing responses or solutions.

Building on the tradition of open-ended experimentation associated with contemporary Western design pedagogies, a design process will typically involve carrying out practical activities and exercises in workshops or studios to explore the ‘problem’ situation, and making moves that develop, test and review possible ‘solutions’ through prototyping (Schon, 1983; Dixon, 2023). Researchers have explained this by suggesting that, rather than a linear process of analysing a problem followed by synthesising results into a solution, ‘problems’ and ‘solutions’ co-evolve during designing (Crilly, 2021). In contrast to experimentation in the sciences, ‘design experiments’ often look small-scale, situated and participatory (Koskinen et al, 2012). In the sciences, experiments such as randomised control trials seek to increase the validity of results by isolating a small number of variables, underpinned by an epistemology (theory of knowledge) that sees the world as objectively assessed; whereas ‘experimentation’ in design takes a situation as evolving and rooted in an epistemology that emphasises the construction and interpretation of knowledge.

In design practices, exploration and experimentation imply, among other things, deliberately causing and exploring uncertain and unanticipated outcomes from which designers anticipate something novel and germane to understanding will be discovered. This approach is aligned with a broader shift in business practice and industrial organisation from a focus on efficiency, which requires predictable activities and outcomes, to a focus on innovation, which provokes and explores unexpected outcomes through experimentation (Martin, 2009). The emergence of the discourse of ‘public sector innovation’ (and New Public Management as a predecessor) represents a similar aspiration towards, and narrative of, transformation in policymaking and governance.

However, while policymaking and government more generally may benefit from greater experimentation, politics in general may not, and this tension must be managed. Tolerance of failure, tolerance of error, pursuing speculative propositions, putting resources into activities that are only weakly justified or provide uncertain returns are not normally ideas associated with good governance. Part of public design consists in challenging this orthodoxy, but only with a due recognition that experimenting on social and political problems can be both politically and morally risky. Rightly or wrongly, it can be difficult for officials to justify activities that do not provide predictable and safe returns, for fear of public objections or of failing to meet the demands or expectations of superiors (Bailey and Lloyd, 2016). Advocates of public design may think that such fears are often ill-advised incentives, but there is also a serious issue of public accountability (which is not incumbent on commercial design) that experimentation trades off against.

This section has identified seven practices associated with professional design that are evident in commercial and public contexts. While not claiming these practices are exclusive to designers, combining them in this way begins to mark out a distinctive capability that is generally understood to enable and support innovation processes.

1.9 Using design practices to achieve outcomes

As with any kind of professional expertise, there are varied ways of understanding how its application leads to outcomes and impacts over different timeframes, how to conceptualise and distinguish between these, and how to produce evidence and insight about the relations between them, including causality. In day-to-day life, people may use the phrase ‘theory of change’ to prompt articulation about how doing something results in outcomes or change (e.g. with public issues, applying design expertise and using approaches associated with design).

Academic research usually works differently. Rather than positing a unifying ‘theory of change’, academic researchers usually seek to understand, explain, analyse, account for, evaluate, contextualise or critically assess change, drawing on research traditions in their field. These traditions can look very different. Very briefly, doing academic research requires having a way of understanding the world (ontology), a theory of knowledge (epistemology), and a methodology for answering research questions, which together are expected to produce new knowledge that is rigorous, significant and original, all understood within a particular academic community. This means there is no single way to analyse when, how, to what extent and under what conditions applying design practices leads to (public) outcomes. There are many academic approaches, rooted in different ways of theorising how individuals, organisations and institutions operate, what design approaches, methods and skills are, and what consequences result from their use or application.

In this literature review, we take a middle way between the shorthand of ‘a theory of change’ and academic research rooted in design and the social sciences. Decades of research and reflection on practice have resulted in accounts of how the application of characteristics of design lead to outcomes in organisations and society. These can be grouped into three main types:

- Economic and financial analysis. Efforts to quantify the impacts of design, often in economic or financial terms, such as McKinsey’s Design Value Index (Sheppard et al, 2018) and the Design Council’s Design Value Framework, which includes economic, social and environmental outcomes (Design Council, 2022a, 2022b; Bailey et al, 2021; Kimbell et al, 2022).

- Practice-based analysis. Accounts of design relying on situated, local analysis often carried out by expert designers or design researchers (see examples cited in this paper).

- Sociological analysis. Accounts of design that mobilise research in studies of organisation and management, and the social sciences more broadly, to underpin analysis. Such studies include numerous sub-fields with different traditions of knowledge production and theorisation.

Two examples serve to show the potential, and limitations, associated with the third group using studies of organising and managing to pin down the ‘outcomes’ achieved by applying design practices. The first example comes from studies in management about design thinking. Design thinking came to prominence through the efforts of a global design consultancy, IDEO (Brown, 2009), and other design professionals making claims that the approaches, methods and mindsets associated with professional design led to innovation. Scholars then used different research approaches to examine the effects of using design thinking on organisational outcomes (see Section 2 for more on design thinking).

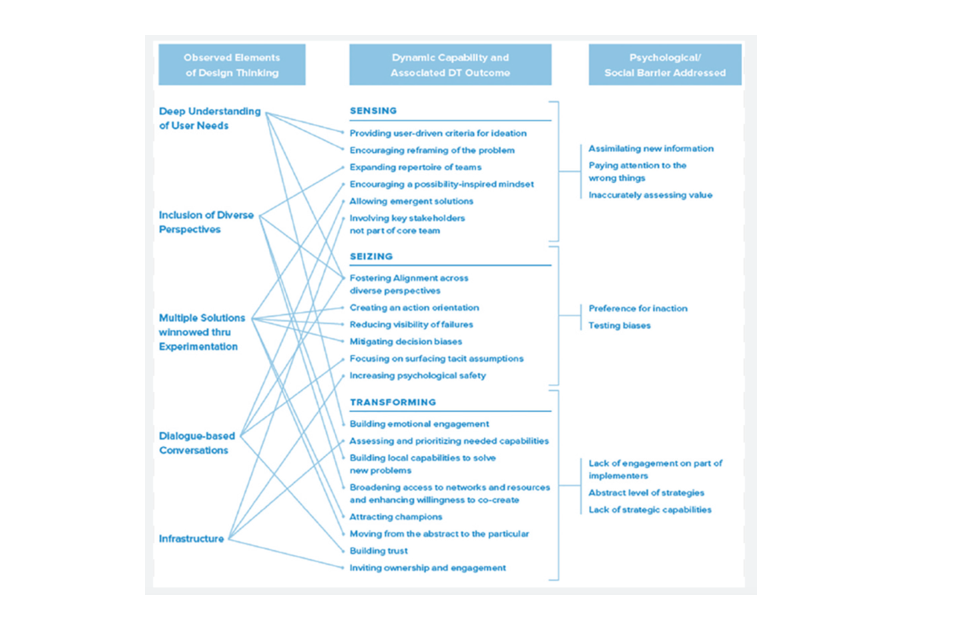

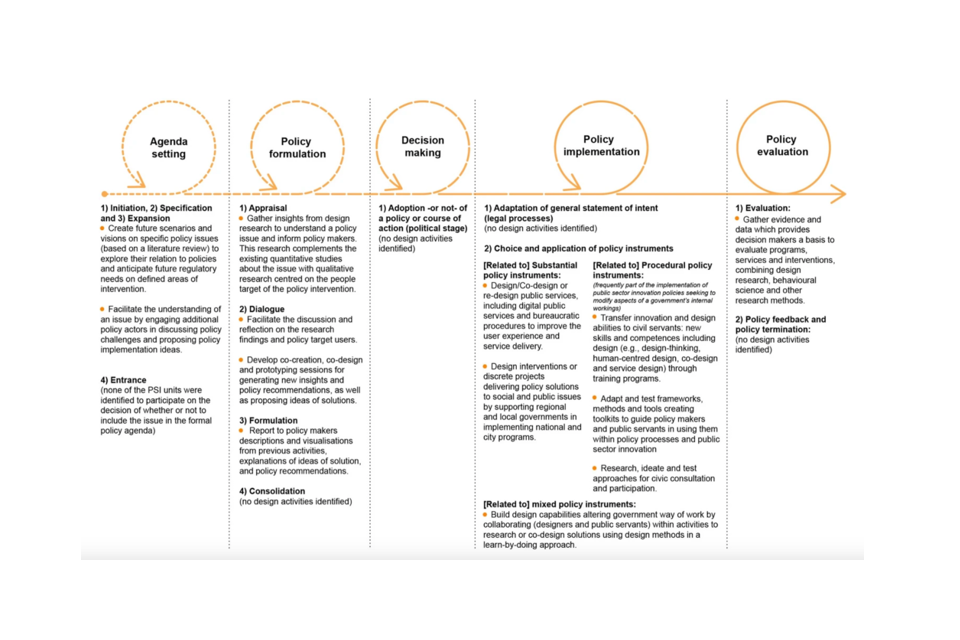

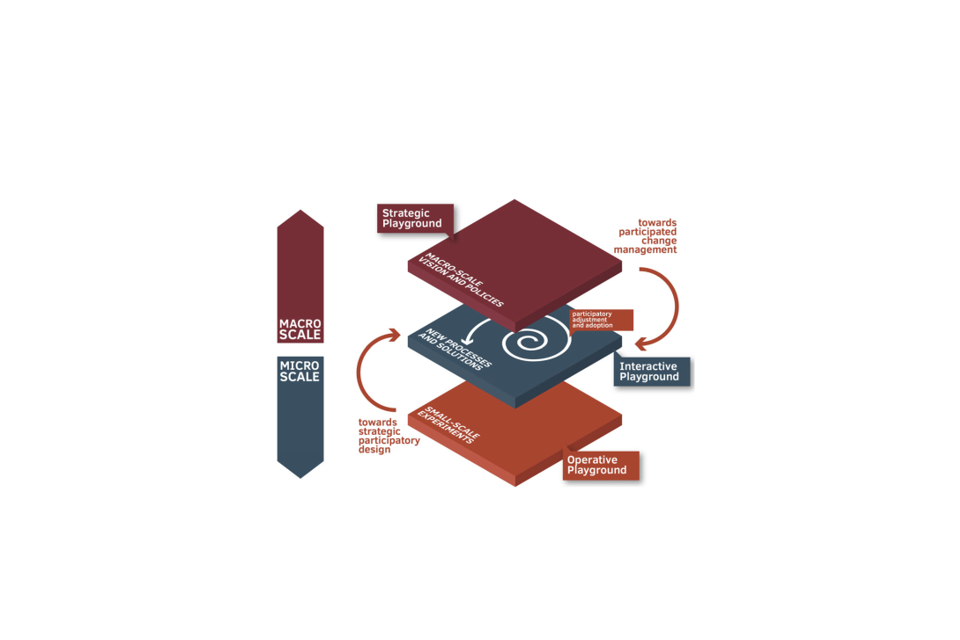

Figure 1: Design thinking characteristics as dynamic capabilities.

A flowchart illustrating the relationship between observed elements of design thinking, dynamic capability, associated outcomes, and psychological and social barriers addressed. Source: Liedtka, 2020.

One management researcher, Liedtka (2020), carried out a large-scale study into design thinking with over 70 case studies of the implementation of design thinking in business, social enterprises and local government. To do the analysis she used well-established ideas from Teece (2007) proposing that organisations can be analysed in terms of ‘dynamic capabilities’ – understood as stable patterns of organisational behaviour. Teece distinguishes between capabilities for sensing, seizing and transforming, as organisations identify and respond to changes in the external environment. Very briefly, sensing capabilities are those which sense, filter, shape and calibrate challenges and opportunities in the landscape; seizing capabilities are those involving structures, procedures, designs and incentives for responding to those opportunities; and transforming capabilities are those relating to organisational re-alignment of assets and resources to make change. Positioning design as a ‘social technology’, Liedtka showed how design thinking enables organisations to continuously build capabilities for ongoing strategic adaptation, summarised in Figure 1.

The contribution of Liedtka’s study is to show how characteristics or practices of design (seen in the left-hand column) result in dynamic capabilities in the organisation (middle column) which lead to addressing barriers to innovation (right-hand column). This is an example of a cross-cutting analysis of what the application of design thinking results in, using an existing way of conceptualising how organisations innovate. Here the outcomes associated with applying design (thinking) are structured through the three dynamic capabilities (sensing, seizing and transforming).

While this is useful for broadly understanding the application of design thinking, what this study does not help directly with is understanding the outcomes of applying design that are other than innovation, or other than ‘design thinking’. There are ongoing debates in research literatures about ways to understand and account for innovation and the relationship between design and innovation. For example, claims that ‘human centred’ design practices are particularly useful for either ‘incremental’ or ‘radical’ innovation are still being debated (Norman and Verganti, 2014; Biskjaer et al, 2019). Further, the term innovation has different narratives and histories when discussed in the public sector and government, compared to commercial settings. In contrast, if the core purpose of government or public service organisations is to deliver public value (see Section 2 for more on this), this emphasis on innovation may not be a fruitful lens to understand public design, if it downplays other important outcomes from applying design practices. A second limitation for the purposes of this literature review is understanding the differences between commercial and public design more precisely, once we recognise that such organisations have different narratives or ‘logics’ associated with how they operate, the ways things are done and what is taken for granted. Differences between commercial and public implementations of design thinking are downplayed in the methodology, as distinguishing between them is not the central purpose of Liedtka’s study.

Turning to a second body of research helps illuminate further the organisational conditions and narratives that can enable or hinder the extent to which applying design practices can lead to outcomes that are deemed as positive. An extensive international body of research that seeks to articulate the outcomes that result from applying design, underpinned by studies of organisations, appears in the multi-disciplinary field of healthcare improvement. Possibly linked to expectations of standards of evidence in clinical healthcare, this field has produced studies over 15 years examining the application of design expertise in healthcare organisations, at a time when other improvement methodologies are also being developed and tested.

Building on an initial study applying service design practices in a cancer service in the NHS in the UK, Bate and Robert (2007) and later researchers (e.g. Tsianakas et al, 2012; Locock et al, 2014; Donetto et al, 2015; Robert et al, 2022) developed, tested and evaluated what is now called ‘Experience-Based Co-Design’ (EBCD). This is now broadly understood as a collaborative way of improving healthcare services by establishing patients and healthcare staff as co-designers at the heart of initiatives and potential changes, with a strong emphasis on their experiences. Clarke et al.’s (2017) rapid evidence synthesis of outcomes associated predominantly with the use of co-production in acute healthcare settings identified three categories of reported outcomes, specifically: patient and staff involvement; the generation of ideas and suggestions for changes to processes, practices and clinical environments; and tangible changes in services and impact on patient or carer experiences – as well as (indirectly) the experiences of staff members. However, while there are now several such studies using mixed qualitative methods, an overview of EBCD (Robert et al, 2022) argued there was little quantitative data evidencing substantial improvements in patient or staff experience resulting from the use of this improvement methodology.

Much of this research focuses on the organisational conditions into which design expertise is being introduced. For example, in a study using EBCD as part of complex interventions in specialist stroke units in the NHS, Clarke et al (2021) found that the approach helped with the analysis and interpretation of the organisational barriers to change. Like other interventions that engage participants to improve services, there are issues related to organisational capacity to absorb and build on these new practices. For example, in a 10-year review of a study of a quality improvement methodology applied widely in the NHS, Sarre et al (2019) found that while there was limited robust evidence of impact, there were positive legacies from the intervention that had informed ongoing organisational practices and strategies.

This wide-ranging body of academic work on EBCD, closely linked to practice, taking place internationally in the NHS and other healthcare systems, demonstrates that design-based approaches can lead to positive outcomes at the level of service experiences, organisation of services, and can generate ideas for implementation that lead to improved patient outcomes. Given the status of the NHS as a public institution funded by government, there is a useful congruence for this paper’s attempt to understand how (public) design leads to (public) outcomes. However, as with any research, these findings tied to narratives of healthcare quality improvement are not immediately applicable outside of the specific conditions in which these outcomes were realised. The take up and implementation of EBCD in public health settings is not directly portable to other domains, even if they are public. This is because researchers recognise the specific contexts in which design is applied, such as organisational cultures, narratives, leadership, work practices, leadership, resources, and availability of design competences.

These necessarily brief summaries of two types of research demonstrate that claims of outcomes achieved through applying design practices are situated and based in particular framings (e.g. organisational innovation) or specific contexts (e.g. public healthcare). Further, such studies are rooted in and thus shaped by particular research traditions. At present there is no single overarching formula that offers justification to explain how design can lead to particular outcomes and the pathways or logics through which this happens. Different research traditions theorise the nature of the social or organisational world in different ways and pay attention to different things in their data collection and analysis. It is therefore worth being cautious about making claims that applying design practices that achieve an outcome in one setting are portable to another, or that the same linkages or relationality can account for changes observed. However, for the purposes of this study, we bring together some of the relevant understandings that can be built on and further developed to underpin how public design leads to public value.

The academic research suggests that practices of design can achieve specific outcomes, while recognising these are highly dependent on enabling conditions. Having reviewed and clustered this research, we distinguish between outcomes associated with the process of designing, and the implementation of designs, summarised in Table 1a and 1b. By no means exhaustive, this table shows a range of outcomes demonstrated by the application of design and suggests their relevance to governments and public services. However, further research is needed to more precisely analyse these outcomes.

Table 1(a): Outcomes from design practices and implementation of designs: related to the process of designing

| Outcomes | Examples from research literatures | Relevance to government and public issues |

|---|---|---|

| Generation of ways of framing situations or problems | Brun et al, 2016; Alipour et al, 2017; Coelho et al 2018, van der Bijl-Brouwer, 2019; Hvidstem and Amqvist, 2023 | Where dissensus and contestation over framings has deadlocked policy action or rendered it ineffective |

| Anticipation of futures in the present | Bali et al, 2019; Engeler, 2017; Jones, 2017; Buehring and Liedtka, 2018; Kera, 2020; Pólvora and Nascimento, 2021; Vesnic-Alujevic and Rosa, 2022 | Where there is a need to develop solutions that engage or create different ecosystems in a context of uncertainty |

| More effective cross-organisational or cross-disciplinary working | Nicolini et al, 2011; Ansell and Gash, 2018; Ou et al, 2023; Bowen et al, 2013 | Where collaboration across multiple departments, forms of knowledge, stakeholders, perspectives and resources is required |

| Deeper shared understanding that is inclusive of perspectives and positions | McDonnell, 2009; van Dijk and Ubels, 2016; Nguyen, M., & Mougenot, 2022; Cash et al, 2020; | Where there are gaps between strategic intent and operational delivery |

| Strengthened ability to negotiate complexity, uncertainty and urgency for participants including staff | Junginger, 2008; Mitchell et al, 2016; Aguirre et al, 2017; Bason, 2017; Robert et al, 2022; Erikson et al, 2023; | Where there is a need to develop new ways of working in public administrations and public services |

| Increased legitimacy of responses | Conradie et al, 2021; Seravalli et al, 2017; Dixon, 2020; Bebbington et al, 2022; | Where there is a need to engage diverse forms of knowledge of the current issue or a problem engaging people with varied stakes |

Table 1(b): Outcomes from design practices and implementation of designs: related to the implementation of designs

| Outcomes | Examples from research literatures | Relevance to government and public issues |

|---|---|---|

| Operational efficiencies and increased effectiveness in implementation | Cockbill et al, 2019; Liedtka, 2020; Liedtka et al, 2020; Allen et al, 2020; | n/a |

| Outcomes specific to the policy issue or domain | Dahl et al, 2001; Collado-Ruiz and Ostad-Ahmad-Ghorabi, 2010; Corcoran et al, 2018; Choi et al, 2019; | n/a |

1.10 Distinctions between commercial and public design

Thus far we have summarised practices associated with design in commercial and public settings, articulated outcomes and explained why how these are achieved is context specific. We turn now to aspects of design where the literature suggests that the characteristics of public design and commercial design are distinct. These are relations to democracy, purposes, accountabilities and novelty.

In making this assessment we draw on our cross-disciplinary knowledge of several academic literatures. We note ongoing and related debates that have emerged in the 21st century, resulting in terms and practices from design becoming more widespread, such as co-design, social design and legal design, including appearing outside industrial or commercial contexts, such as social and public innovation and legal services. For example, a recent publication from Demos on co-production with citizens (Levin et al, 2024) included ‘co-design’ as a method with specific relevance downstream in the policy cycle, not upstream or strategic, whereas literature on co-design suggests it can help achieve both. Similarly ‘social design’ is a term and a field with a variety of approaches and impacts, as illustrated in a collection of articles by academics in several fields at the University of the Arts London which reveals a strong orientation to applying design towards positive societal transformation across many spheres of life, from the justice system to textiles to health (University of the Arts London, 2020). Absent an established definition of ‘public’ design, we therefore suggest areas where public and commercial design might be distinguished.

Public design as democratic practice

Commercial and public design differ in the extent to which design practices seek to operate on a democratic basis.

Public designers who work in central or local government can be understood to be legitimised by and accountable to various sources of democratic authorisation. The most obvious and traditional of these is the representative system: civil servants derive their authority from ministers and government, via Parliament, and ultimately popular authorisation through general election. This account of public designers’ democratic legitimacy and accountability follows from a fairly traditional account of democratic authorisation. It remains important, but both political scholarship and UK politics in general have moved on from the belief that this is the sole mechanism through which policy and governance is authorised.

This is to do partly with how scholarly understanding of political representation has changed and partly with how representation itself has receded as the dominant mechanism of democratic practice. On the first count, it is no longer taken to be the case that representation is necessarily enacted through the election of representatives to act on citizens’ behalf. Nobody elected Oxfam, but it might justly be said that Oxfam ‘represents’ people in the Global South who do not have access to the halls of power via traditional electoral representation (Montanaro, 2017). Lots of people are uncomfortable with this framing and might dispute how well or how qualified Western NGOs are for such tasks, but insofar as they seek to act in the best interests of otherwise unrepresented people, the basic point stands. Additionally, there is some debate over whether it is more appropriate to try and increase the representation of marginalised persons (‘descriptive representation’) or increase the representation marginalised points of view (‘discursive representation’) (Mansbridge, 1999; Dryzek and Niemeyer, 2008). The majoritarian character of the UK constitution does not especially favour either, and so it is increasingly accepted that representation may occur through other means: interest groups, charities, NGOs, petitions, public consultations, committees, quangos and commissions. A basic and general way in which public design is democratic is the commitment to various kinds of non-electoral representation that are increasingly taken to be a vital democratic functioning. Design discourse has its own conceptual vocabulary, but under labels like ‘inclusive design’, ‘co-design’ and ‘social design’, public design practices enact the representation of a diverse range persons, discourses, expertise and interests in ways not served by electoral representation.

On the second count, since the 1970s, forms of democratic governance based not in representation and electoral competition but in citizen deliberation and participation have been slowly gaining traction. This is in part a consequence of the ‘crisis’ that engulfed public administration and the professions in the 1970s (Rittel and Webber, 1973; Ostrom, 1974; Schön, 1983; Bohman and Rehg, 1997), which had a major impact both on design studies and democratic theory. Concurrently, it should also be noted that the rise of participatory and ‘open’ governance practices coincides with the transition away from state-centric models and towards networked governance, which involve a larger number of actors and connections (Clarke and Craft, 2019; Wellstead et al., 2021). To a great extent, public design is the mature product of the rejection of technocratic and rationalistic approaches to governance in democratic settings, and decades of work to develop an alternative.

On the other side of the politics and policymaking coin is democratic theory, in which the traditions of deliberative and participatory democracy are now hegemonic. Broadly speaking, deliberative democracy is a school of thought that supposes the primary source of legitimacy for political action in a democracy is not vote-counting but reason-giving, less by representatives and more by affected citizens themselves (Dryzek 1990, 2000; Guttmann and Thompson, 1996; Parkinson and Mansbridge, 2012; Elstub, 2014; Warren et al. 2020). Citizens are not just sources of interests and preferences which must be ‘counted up’ in a majoritarian or pluralistic fashion, but sources of reason, knowledge and judgement which can be brought to bear on important political issues. Following this logic, policies, decisions and other political activities are legitimate to the extent to which they are the product of a process of free, respectful and reasonable exchange between affected persons oriented to the public good (Cohen, 1989; Benhabib, 1996; Chambers, 1996). This is the deliberative claim. Such ideas have long since outgrown political scholarship. Specialised forums for public deliberation and citizen participation (often called ‘mini-publics’) are now in widespread use in democratic (and some non-democratic) contexts the world over (see Elstub, 2014). In the UK especially, there is now a strong and self-sustaining industry dedicated to providing, promoting and building capacity for deliberative and participatory capacity, spearheaded in the third sector by organisations such as Involve, the Sortition Foundation and the Democratic Society. Aside from repeated calls for a citizens’ assembly to break the deadlock over Brexit, recent high-profile deliberative activities in the UK include the Citizens’ Assembly for Northern Ireland (2018), the CIimate Assembly UK (2019) and the Citizens’ Convention on UK Democracy (Citizens’ Convention on UK Democracy, n.d.).

These developments are important here because public design shares a parallel history and the same theoretical underpinnings, which helps explain why public design both promotes and is required by the prevailing conception of democratic legitimacy in UK politics. To illustrate this, it is necessary to explicate the important parallels and synergies between participatory and deliberative democracy and public design, which are both products of the same intellectual, political and organisational developments over the last fifty years (Bächtiger et al., 2020; Bohman and Rehg 1997; Chambers, 1996, 2003; Dryzek, 2000, Elstub et al., 2016).

First, deliberative and participatory democrats assume that citizens are experts in their own lives and interests, in the same way that designers take users and stakeholders to be so. Decisions are legitimised by citizen deliberation for the same reason that designs are legitimised by stakeholder and user inputs: because they are rooted in the real lives of persons affected by them, and because design and democratic practice typically permit those persons a degree of authorship in presenting those lives and experiences. Put another way, both public designers and participatory democrats view experiences as evidence of prime importance. Deliberation between actual citizens allows them to bring their experiences to bear on politics in a way that mass electoral politics does not, so in the same way as public design, participatory and deliberative democratic practices are about bringing rich, experiential evidence to the table – often in place of (but also assisted by) technical and specialised expertise.

Second, public design is often described as a ‘bridge-building’ discipline; in this paper we have called it ‘integrative’. Design is understood to have no special subject-domain of its own, but consists in a capability for bringing many others together: different actors, issues, expertise and knowledge domains, perspectives, interests, and, ultimately, meanings and understandings. What constitutes ‘wellness’ for a pensioner in assisted living might have a different meaning for health visitor, doctor or policymaker, and it is the task of public design to help them develop a shared understanding that can be the basis of a constructive solution. Deliberative democracy is likewise seen as powerful for its propensity to bring together persons of different backgrounds, interests and understandings – people who may profoundly disagree on sensitive matters – and have them develop shared understandings. Naturally, one advantage of this is that it can be a basis for consensus, and thus political action. But, like public design, a strong theme of deliberative scholarship and practice is about democratic capacity-building. Confronting the experiences of differently-situated individuals and making a sincere effort to understand them transforms participants, fostering interpersonal, cognitive and political skills taken to be essential to democratic citizenship.

Public design and participatory democracy were born of the same intellectual and professional crisis, and both adopt a constructivist epistemology rooted in the transformation of ordinary people and the primacy of their experiences. Such experiences and expertise are increasingly seen less as helpful and supplementary additions to policymaking and more as necessary and obligatory ones. Insofar as they are distinct, public design places a greater emphasis generating, creating and synthesizing solutions, which is inherent to design but not to democracy. Deliberative democracy is oriented towards opinion formation, will formation (decision making) and building democratic capacity and citizenship. In general, democratic theory has focused on how political actions, policies and solutions are selected, rather than how they are synthesised. Relatedly, and partly for historical reasons, participatory and deliberative democracy emphasises verbal (ideally face-to-face) discussion and places little emphasis on visualising and materialising, as public design does.

In summary, it is public design’s foundation in democratic thinking, institutions and practices that results in an important distinction between it and commercial design. Whether viewed through the lens of representative democracy (for example institutionalised in the Civil Service code), or through deliberative understandings of democracy, design practices associated with government and policy have a distinctive set of considerations and implications.

Purposes for design

Commercial and public design differ in the purposes towards which design expertise is mobilised and how outcomes are assessed.

Given this differing basis in democratic practice, it is not surprising to make a further claim that the purposes to which public and commercial design are put are distinct. In commercial organisations the use of design is generally tied to enabling or supporting innovation in order to improve the performance of the financial bottom line, although environmental and social impacts of business are increasingly visible as intentions and outcomes. Measuring success is often required to be quantifiable and relatively clear, with existing processes, expertise and infrastructures in place to assess outcomes.

In contrast, as a result of its democratic underpinnings, public design is tied to varied agendas and narratives, and it can be harder to discern the specific goals to which design can reasonably be expected to contribute. Public sector organisations innovate in order to improve their performance with respect to a much wider range of social, political and organisational needs, which may be rival, contestable or more difficult to define and operationalise. For example, Bason (2010: 44-49) suggests four alternative ‘bottom lines’ against which to measure the performance of innovation in the public sector: productivity, service experience, results and democracy. There is growing evidence that design practices can be understood as a means of ‘doing’ politics. Reviewing the emergence of design-based approaches in urban planning and place-making, Collier and Gruendel (2022) noted that the focus of these practices was on the ‘design of politics’ rather than the aesthetic or functional qualities of material or urban environment. Instead of downplaying politics, design practices can be mobilised in relation to policymaking in different ways, including challenging how things are done (Kimbell et al, 2023).

Moreover, the task of setting and prioritising design objectives becomes more complicated where they are connected to democratic legitimacy, political discourses and agendas with more elusive meanings (e.g. ‘sustainability’ or ‘levelling up’). For example, there is a burgeoning discourse of ‘design justice’ and ‘decolonising design’ that seeks to critique and find alternatives to assumptions, dominant worldviews and biases built into contemporary practice (e.g. Abdulla et al, 2018; Costanza-Chock, 2020.). In the public sector specifically, there is a line of critique that suggests public design could contribute to creeping and self-justifying forms of social control (Swyngedow, 2005). Furthermore, the basis on which citizens interact with the state is not always analogous to the basis on which consumers interact with firms. Langham and Paulson (2017) observe how the commercial notion of service design, and attendant concepts like ‘service quality’, are not easily ported to a public context, such as doing one’s tax return (which is, in an unintuitive way, a public service). Such services do not involve a voluntary relationship in which the customer is provided with some benefit, but are instead motivated by compliance and done out of duty or obligation.

Although such frameworks are important in framing and measuring the generalised value of public design, there is of course an extent to which ends and values in public design will be context or problem-specific and outcomes are realised contingently in institutional settings (Huybrechts et al, 2017). Moreover, a characteristic of all design is that ends and goals are often defined endogenously within the design project. But in commercial design, design objectives are always ultimately instrumental to that financial bottom line (or other financial imperatives like market share) and to social accountabilities, to the extent that a business organisation is aligned with them, whereas end goals in public design really are end goals. Financial sustainability is necessary but is ultimately subservient to debates about the production of public value.

Accountabilities

Commercial and public design differ in the societal accountabilities built into professional practice.

While commercial and public design practices may look similar at first glance – for example, using methods and tools that foreground people’s experiences of services and systems – there are important differences in the ways that designers understand the societal accountability of their professional expertise. Unlike other design-based professions such as architecture and engineering, people working in graphic, user experience and service design do not have a defined or regulated body of knowledge (Kimbell et al, 2021). Some designers choose to become a member of the Chartered Society of Designers, an independent body that defines design competences required for professional practice (see section 4). Any designer may apply and undertake the Pathway to Chartered Designer, a protected title and only awarded by the Register of Chartered Designers, which exists by Royal Charter. This is a voluntary arrangement. In contrast, to practise as an architect in the UK requires being registered by the Architects Registration Board, set up by Parliament in 1997 to regulate the profession. Hence, while many design fields are referred to as ‘professions’, they do not have the characteristics typically associated with ‘protected’ professions through which accountabilities are embedded in practice, such as statutory requirements and formal registration to demonstrate achieving levels of certified knowledge and ongoing professional development, in order to practice legally (Abbot, 2001).

While such formal accountabilities are lacking in both commercial and public design, the ad hoc or situated sets of relations and standards to which different types of designers are held to account are different. In unregulated commercial digital or multi-disciplinary design contexts reliant on consultancy income, learning and development are contingent on firm leadership and owners, while accountability to clients is paramount. Compared to the wider workforce, more designers work as freelancers (27.1% versus 14.7%) (Design Council, 2015), and this makes it less likely that resources and expertise are available to structure accountabilities outside immediate commercial priorities. In large consulting firms that sell expert professional knowledge, or in design teams in large organisations, such precarity may be reduced through the ongoing processes of talent management and professional development.

In contrast, in public design, as previously suggested, designers working in local government, the NHS or the Civil Service are guided, like other employees, by the ethical and epistemological norms and values of social inquiry, by accountability of ministers to Parliament and by institutionalised frameworks, such as the Civil Service Code; and they are supported and assessed by human resources capabilities typically found in such organisations. However, even in organisations such as the Civil Service, there are varied accountabilities built into different kinds of professional work. For example, policy makers might be accountable to ministers leading departments, as well as Senior Civil Servants, in addition to their line managers; whereas civil servants with design roles may not see themselves as directly accountable to ministers (who set overarching policies) for their professional work and its outcomes. Further, narratives about serving user needs (an informal professional accountability in design) may come into conflict with ministerial priorities, raising the question of how accountabilities for service or policy designers working in government are structured, negotiated and managed. In short, the accountabilities of public designers are different to those working in commercial contexts, requiring different forms of negotiation and navigation.

Novelty

Commercial and public design differ in the importance they attach to novelty.