Country policy and information note: religious minorities, Syria, July 2025 (accessible)

Updated 6 January 2026

Version 1.0

Executive summary

On 8 December 2024, the regime of Bashar Al-Assad fell, bringing an end to over 50 years of Al-Assad family rule. An Islamist rebel group called Hayat Tahrir Al-Sham (HTS) led by Ahmad Al-Sharaa, commenced the 11-day offensive which culminated in the toppling of Al-Assad. Ahmad Al-Sharaa is now the de facto leader of Syria, and figures affiliated with HTS occupy the major positions in the new government.

In general, Christians, Druze and Shia Muslims (Ismaili and Twelvers) are unlikely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm from the state. The onus is on the person to demonstrate otherwise.

There is reporting on the situation for minorities in Syria. Whilst it often focuses on the group collectively without detail on how or if the change in regime is specifically affecting those of differing faiths in practice, there are many reports which focus on the concerns, caution and fears within Christian communities due to the recent political upheaval. This includes specific reporting of concerns, caution and fears within Christian communities.

However, much appears speculation of what may or might happen. There are also significant amounts of mis- and dis-information, particularly affecting members of religious minority groups. A fear of persecution or serious harm must be objectively well-founded to the requisite standard of proof. The evidence to date does not support a conclusion that Christians or other religious minorities are being systematically targeted by the state.

Similarly, the events on Syria’s Mediterranean Coast over the weekend of 6–9 March 2025 may have also caused or added to a sense of concern amongst Syria’s other minority groups. There are reports that a very small number of Christians – reportedly seven out of 800-1,000 – were killed in those attacks. Some other religious minorities were also killed in the events. However, the overwhelming majority of those who were targeted and killed were members of the Alawite community.

There have also been attacks on Shia communities reported in February and March 2025. However, the number and frequency of these – relative to the sizes of the respective populations – means that, in general, there is not a real risk of persecution or serious harm to religious minorities.

Where the person has a well-founded fear of persecution or serious harm from the state, they are unlikely to obtain protection and unlikely to be able to internally relocate to escape that risk.

Where a claim is refused, it is unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

All cases must be considered on their individual facts, with the onus on the person to demonstrate they face persecution or serious harm.

Assessment

Section updated: 13 May 2025

About the assessment

This section considers the evidence relevant to this note – that is the country information, refugee/human rights laws and policies, and applicable caselaw – and provides an assessment of whether, in general:

- a person faces a real risk of persecution/serious harm by the Syrian government because the person belongs to a minority religious group.

- the state (or quasi state bodies) can provide effective protection

- internal relocation is possible to avoid persecution/serious harm

- a claim, if refused, is likely or not to be certified as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

Decision makers must, however, consider all claims on an individual basis, taking into account each case’s specific facts.

This note focuses primarily on the situation for Christians, Druze and Shia Muslims, (excluding Alawites, information on which can be found in the Country Policy and Information Note on Syria: Alawites and Actual or Perceived Assadists), following the fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime to Hayat Tahrir Al-Sham (HTS) on 8 December 2024. For further background on the regime’s collapse, see Country Policy and Information Note on Syria: Returnees after fall of Al-Assad regime.

Sources cited in the country information may refer interchangeably to Hayat Tahrir Al-Sham (HTS), or the interim or de facto government or authorities. Within this assessment, we use the (new) Syrian government and, since 8 December 2024 they are considered the controlling party of the state or a substantial part of the territory of the State (for the purposes of Article 1(A)(2) of the Refugee Convention).

1. Material facts, credibility and other checks/referrals

1.1. Credibility

1.1.1 For information on assessing credibility, see the instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

1.1.2 Decision makers must also check if there has been a previous application for a UK visa or another form of leave. Asylum applications matched to visas should be investigated prior to the asylum interview (see the Asylum Instruction on Visa Matches, Asylum Claims from UK Visa Applicants).

1.1.3 Decision makers must also consider making an international biometric data- sharing check, when such a check has not already been undertaken (see Biometric data-sharing process (Migration 5 biometric data-sharing process)).

1.1.4 In cases where there are doubts surrounding a person’s claimed place of origin, decision makers should also consider language analysis testing, where available (see the Asylum Instruction on Language Analysis).

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – Start of section

The information in this section has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – End of section

1.2 Exclusion

1.2.1 Under the Assad regime, human rights violations were systematic and widespread. Civilians also suffered human rights abuses at the hands of other parties to the conflict (see the Country Policy and Information Note on Syria: Security situation).

1.2.2 Decision makers must consider whether there are serious reasons to apply one (or more) of the exclusion clauses. Each case must be considered on its individual facts.

1.2.3 If the person is excluded from the Refugee Convention, they will also be excluded from a grant of humanitarian protection (which has a wider range of exclusions than refugee status).

1.2.4 For guidance on exclusion and restricted leave, see the Asylum Instruction on Exclusion under Articles 1F and 33(2) of the Refugee Convention, Humanitarian Protection and the instruction on Restricted Leave.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – Start of section

The information in this section has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – End of section

2. Convention reason(s)

2.1.1 Actual or imputed race or religion

2.1.2 Establishing a convention reason is not sufficient to be recognised as a refugee. The question is whether the person has a well-founded fear of persecution on account of an actual or imputed Refugee Convention reason.

2.1.3 In the absence of a link to one of the 5 Refugee Convention reasons necessary for the grant of asylum, the question is whether the person will face a real risk of serious harm to qualify for Humanitarian Protection (HP).

2.1.4 See the Country Policy and Information Notes, Syria: Security situation and Syria: Humanitarian situation.

2.1.5 For further guidance on the 5 Refugee Convention grounds, see the Asylum Instruction, Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

3. Risk

3.1.1 In general, Christians, Druze and Shia Muslims (Ismaili and Twelvers) are unlikely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm from the state. The onus is on the person to demonstrate otherwise.

3.1.2 There is reporting on the situation for minorities in Syria. Whilst it often focuses on the group collectively without detail on how or if the change in regime is specifically affecting those of differing faiths in practice, there are many reports which focus on the concerns, caution and fears within Christian communities due to the recent political upheaval. This includes specific reporting of concerns, caution and fears within Christian communities.

3.1.3 However, much appears speculation of what may or might happen. There are also significant amounts of mis- and dis-information, particularly affecting members of religious minority groups. A fear of persecution or serious harm must be objectively well-founded to the requisite standard of proof. The evidence to date does not support a conclusion that Christians or other religious minorities are being systematically targeted by the state.

3.1.4 Similarly, the events on Syria’s Mediterranean Coast over the weekend of 6 to 9 March 2025 may have also caused or added to a sense of concern amongst Syria’s other minority groups. There are reports that a very small number of Christians – reportedly seven out of 800 to 1,000 – were killed in those attacks. Some other religious minorities were also killed in the events. However, the overwhelming majority of those who were targeted and killed were members of the Alawite community.

3.1.5 There have also been attacks on Shia communities reported in February and March 2025. However, the number and frequency of these – relative to the sizes of the respective populations – means that, in general, there is not a real risk of persecution or serious harm to religious minorities.

3.1.6 Syria’s population was estimated at 23.865 million in 2024, though demographic data may be unreliable due to continued population displacement. The majority (approximately 74%) are Sunni Muslim. Alawites and other Shia sects like Ismailis and Twelvers account for 13%. Christians – mostly Orthodox and Catholic – have significantly decreased since 2011, from officially 10% to now roughly 5% (around 1.2 million) of the population, though some sources estimate under 600,000 remain (see Demography).

3.1.7 Christians are primarily concentrated in Damascus, Aleppo, Homs, Hama, and Latakia, with smaller communities in Hasakah and Qamishli. Ismailis are mainly located in Salamiyah, near Hama. Twelver Shia are found around Damascus, Aleppo, and Homs. Druze predominantly reside in the Suweida governorate (see Geographical locations).

3.1.8 The (new) Syrian government has publicly reassured Christian leaders of their commitment to religious freedom, including restoring properties and protecting religious symbols. Meetings between Syrian government officials and Christian leaders have focused on addressing grievances and fostering security, with some reports of relative stability, especially in Damascus and Aleppo. Christmas celebrations in these cities went largely unaffected. An incident involving a Christmas tree arson was quickly dealt with by the authorities, who have also provided visible security measures, such as guarding Christian neighbourhoods.

3.1.9 While some Christians have praised the Syrian government for their reassurances, others remain cautious due to HTS’ historic treatment of Christians, and wary of the imposition of Islamist rule (see Situation for minorities post-Assad regime – Christians).

3.1.10 The Syrian government has made efforts to reassure Druze leaders, meeting with representatives in both Suweida (Suwayda) and Jabal al-Summaq in Idlib to discuss safety and inclusion. The Druze in Suweida maintain a level of autonomy, with local militias controlling security in the region. The community’s leaders have emphasised their desire to preserve constitutional rights and protect their quasi-autonomous status held under Assad.

3.1.11 At the end of 2024, the Syrian government appointed a female member of the Druze community as governor for Suweida. In early January 2025, Druze militias prevented HTS-led military convoys from entering the province. However, the 2 largest Druze militias later offered their readiness to join a new national army, whilst security of the Suweida region has been delegated by the government to local forces.

3.1.12 In March 2025, the Syrian government reached an agreement with Suweida’s Druze community to integrate the province into state institutions, placing local security services under the authority of the Ministry of Interior. Also in March, a senior Druze cleric publicly rejected the interim constitution, with his statement emphasizing the need for a separation of powers, expanded local governance authority and checks on the power of the president.

3.1.13 Fighting broke out on 28 April 2025 between pro-government armed groups and Druze factions in the southern Damascus suburb of Jaramana. The clashes followed an alleged insult against the Prophet Mohammad by a Druze leader and reportedly led to the deaths of up to 100 people. On 30 April the government’s General Security and Druze representatives negotiated a truce, and calm was restored (see Situation for minorities post-Assad regime – Druze).

3.1.14 Some Shia communities, such as those in Nubl in northern Syria, have expressed relief at the transition of power under the new government, with reports indicating a safer return to their homes, while others report threats and violence. Amid fears of sectarian violence, thousands of Shias fled Damascus to neighbouring Lebanon, reporting social media harassment, and looting and arson by unknown armed men. However, there are reassurances from the government regarding the protection of Shia sacred sites and efforts to safeguard their communities, as seen with the guarding of the Zaynab shrine. For Ismailis, the transition has been notably smoother including the peaceful handover of Salamiyah to the government (see Situation for minorities post-Assad regime – Shia Muslims).

3.1.15 For further guidance on assessing risk, see the Asylum Instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

4. Protection

4.1.1 Where the person has a well-founded fear of persecution or serious harm from the state, they are unlikely to obtain protection.

4.1.2 For further guidance on assessing state protection, see the Asylum Instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

5. Internal relocation

5.1.1 Where the person has a well-founded fear of persecution or serious harm from the state, they are unlikely to be able to relocate to escape that risk.

5.1.2 For further guidance on internal relocation and factors to consider, see the Asylum Instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

6. Certification

6.1.1 Where a claim is refused, it is unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

6.1.2 For further guidance on certification, see Certification of Protection and Human Rights claims under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 (clearly unfounded claims).

Country information

About the country information

This section contains publicly available or disclosable country of origin information (COI) which has been gathered, collated and analysed in line with the research methodology. It provides the evidence base for the assessment which, as stated in About the assessment, is the guide to the current objective conditions.

The structure and content follow a terms of reference which sets out the general and specific topics relevant to the scope of this note.

This document is intended to be comprehensive but not exhaustive. If a particular event, person or organisation is not mentioned this does not mean that the event did or did not take place or that the person or organisation does or does not exist.

The COI included was published or made publicly available on or before 13 May 2025. Any event taking place or report published after this date will not be included.

Decision makers must use relevant COI as the evidential basis for decisions.

7. Fall of Assad regime

7.1.1 On 8 December 2024, Syrian Islamist rebels, led by Ahmad al-Sharaa of Hayat Tahrir Al-Sham (HTS), captured the capital city of Damascus and overthrew President Bashar al-Assad.[footnote 1] [footnote 2] For further background on the fall of the Assad regime and formation of a new government, which included a Druze and a Christian, see the Country Policy and Information Note on Syria: Returnees after fall of Al-Assad regime.

8. Legal context

8.1 Constitutional protections

8.1.1 Article 3 of the 2012 Constitution declared that the State ‘shall respect all religions, and shall ensure the freedom to perform all the rituals that do not disturb prejudice public order.’[footnote 3] There was no official state religion[footnote 4] but the constitution stated, ‘The religion of the President of the Republic is Islam’, and stipulated Islamic jurisprudence as the basis of legislation.[footnote 5] Article 33 provided for equal rights without discrimination on grounds of religion.[footnote 6]

8.1.2 Freedom House noted in its report, Freedom in the World 2024, covering 2023 events, that ‘Jehovah’s Witnesses are banned, proselytizing is restricted, and conversion of Muslims to other faiths is prohibited.’[footnote 7]

8.1.3 On 29 January 2025 the constitution was annulled by HTS-led interim authorities[footnote 8] and, according to HTS leader, Ahmad al-Sharaa, a new one could take ‘up to three years’ to draft.[footnote 9]

8.1.4 A briefing on 11 February 2025 by the European Parliament noted that the HTS had ‘… declared plans to establish a political transition inclusive of all minorities and segments of Syrian society…’[footnote 10]

8.1.5 On 14 March 2025, BBC News stated that:

‘Syria’s interim President Ahmed al-Sharaa has signed a constitutional declaration covering a five-year transitional period, three months after his Islamist group led the rebel offensive that overthrew Bashar al-Assad.

‘The document says Islam is the religion of the president, as the previous constitution did, and Islamic jurisprudence is “the main source of legislation”, rather than “a main source”, according to the drafting committee.

‘It also enshrines separation of powers and judicial independence, and guarantees women’s rights, freedom of expression and media freedom.

‘… Only 10 days ago, Sharaa announced the formation of the seven-member committee to draft the constitutional declaration, which he said would serve as “the legal framework regulating the transitional phase”.

‘A member of the committee, Abdul Hamid al-Awak, a constitutional law expert who teaches at a Turkish university, told a news conference on Thursday that the declaration aimed to “create a balance between a security society and rights and freedoms”.

‘He said it stipulated “absolute separation of powers”, pointing to Assad’s “encroachment” on other branches of government during his 24-year rule.

‘The president would have executive authority during the transitional period, he said, but would have only one “exceptional power” – the ability to declare a state of emergency.

‘A new People’s Assembly will have full responsibility for legislation. Two thirds of its members will be appointed by a committee selected by the president and one third chosen by the president himself.

‘A committee will also be formed to draft a new permanent constitution. Sharaa has promised an inclusive government that will run the country until the new constitution is finalised and free and fair elections are held.’[footnote 11]

8.1.6 An official translation of the March 2025 constitutional declaration was published on the ConstitutionNet website.

8.2 Personal status laws

8.2.1 A 2018 report on Syrian personal status laws, authored by Syrian lawyer, Daad Mousa and published in December 2018 by Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES), noted that:

‘According to the judicial authority in Syria, the Sharia courts handle all the personal status cases of Muslims, while correspondingly, the Druze courts are responsible for the personal status cases of the Druze and the Christian courts for those of Christians. It should be noted that all those presiding over these religious courts are men. In addition, those presiding over the Sharia and Druze courts are considered judges, while in the Christian courts they are in fact priests.’[footnote 12]

8.2.2 A report dated 21 March 2023 by independent human rights group, Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ), noted that ‘Syria has no unified law for personal status issues, but several sectarian laws:

- ‘Syrian Personal Status Law No. 59 of 1953 and its amendments, regulates personal status for Muslims of all sects

- Personal Status Law for the Druze Sect of 1948

- The Greek Orthodox Personal Status Law No. 23 of 2004

- The Syriac Orthodox Personal Status Law No. 10 of 2004

- The Armenian Orthodox Personal Status Law

- The Catholic Personal Status Law No. 31 of 2006

- Law No. 2 of 2017 regulates inheritance and wills for the followers of the Evangelical denomination in Syria

- Law No. 4 of 2012 regulates inheritance and wills among the Armenian Orthodox sect

- The Jewish Code of Personal status/Qanun al-ahwal al-shaksiah li al –Musawiyyin.’[footnote 13]

9. Demography

9.1 Ethnic and religious population

9.1.1 According to the CIA World Factbook, the estimated total population as of 2024 was 23.865 million.[footnote 14] The US Department of State International Religious Freedom report covering 2023 (USSD IRF Report 2023) cited ‘a degree of uncertainty to demographic analyses’ due to continued population displacement.[footnote 15]

9.1.2 International human rights organisation, Minority Rights Group (MRG), noted in their profile of Syria, dated January 2025, that some of the country’s minorities were defined by religion and others by ethnicity.[footnote 16] In their foreign travel advice, the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) noted that, ‘Syria is a multi-faith country. Alongside the majority Sunni population, there are large practising Shia, Christian, Druze and Alawite communities, as well as other smaller sects and religions.’[footnote 17]

9.1.3 Whilst noting that demographic data was unreliable, according to MRG the main religious groups were ‘Sunni Islam (74 per cent), Alawi Islam and other Muslim (including Isma’ili and Ithna’ashari or Twelver Shi’a) (13 per cent), Christianity (including Greek Orthodox, Syriac Orthodox, Maronite, Syrian Catholic, Roman Catholic and Greek Catholic) (10 per cent), Druze (3 per cent); other smaller communities, such as Yezidis.’[footnote 18]

9.1.4 Hayat Tahrir Al-Sham (HTS), the group which controls the ‘majority of Syria’[footnote 19] following the fall of the Bashar al-Assad regime on 8 December 2024[footnote 20][footnote 21], has been described as Sunni Islamist[footnote 22][footnote 23], once affiliated to al-Qaeda until it split from them in 2016.[footnote 24] [footnote 25] Sunni Muslims, the majority faith, lived throughout the country according to reports published in 2024.[footnote 26] [footnote 27]

9.1.5 The CIA World Factbook cited the ethnic groups as ‘Arab ~50%, Alawite ~15%, Kurd ~10%, Levantine ~10%, other ~15% (includes Druze, Ismaili, Imami, Nusairi, Assyrian, Turkoman, Armenian).’[footnote 28] In December 2024, German broadcaster Deutsche Welle (DW), noted the ‘many ethnic minorities in Syria’ included ‘Druze, Palestinian, Iraqi, Armenian, Greek, Assyrian, Circassian, Mandean and Turkoman groups. Most of them live in and around Damascus.’[footnote 29]

9.2 Christians

9.2.1 Whilst caution should be attached to International Christian Concern (ICC), who describe themselves as ‘giving hope to persecuted Christians’ (and their website title is persecution.org), and that their ‘advocacy’ and ‘awareness’ and ‘to build the Church in the most challenging parts of the world’ raise questions over the source’s impartiality. Nevertheless, it noted in January 2025 that ‘Syria’s Christian community is diverse, consisting of Orthodox, Catholic, and Protestant denominations, along with a small number of informal house groups of converts from Muslim backgrounds.’[footnote 30] According to the USSD IRF Report 2023, ‘Most Christians belong to autonomous Orthodox churches, such as the Syriac Orthodox Church, Eastern Catholic churches such as the Maronite Church, or the Assyrian Church of the East and other Nestorian churches.’[footnote 31] The 21 March 2023 report by STJ noted ‘The country’s largest Christian denomination is the Greek Orthodox Church and the smallest is the Chaldean Catholic Church.’[footnote 32]

9.2.2 MRG’s profile on Syria from March 2018 noted that ‘Christians of various denominations make up around 10 per cent of Syria’s population.’[footnote 33] The USSD IRF Report 2023 also noted the population of Christians was around 10% but acknowledged reports indicating that figure was ‘considerably lower.’[footnote 34] The CIA World Factbook stated the official number of Christians was 10% of the population but noted that it ‘… may be considerably smaller as a result of Christians fleeing the country during the ongoing civil war.’[footnote 35]

9.2.3 The New Arab, an English-language site covering the Middle East and North Africa, reported on 24 December 2024 that Christians ‘… once made up about 10% of Syria’s pre-war [2011] population, have seen their numbers dwindle dramatically from 1.5 million in 2011 to just 300,000 today.’[footnote 36] A 16 December 2024 article in La Croix International (a French-Catholic media outlet[footnote 37]), noted that ‘… the population has dropped from 8% to just 2% in this country of 23 million’[footnote 38] [therefore, from 1.84 million to around 460,000]. Christian rights group, Open Doors, estimated 579,000 Christians remained in the country[footnote 39], whereas a DW report of 23 December 2024 estimated the number to be around 5% of the total population[footnote 40] [therefore circa 1.2 million].

9.2.4 According to the 16 December 2024 article in La Croix International, ‘85% of Christians have left Syria since 2011’.[footnote 41]

9.2.5 ICC noted in January 2025 that ‘While exact numbers are difficult to estimate due to the instability of the last decade, it is believed that since the conflict began in 2011, Syria’s Christian population has declined by 70% to 80% from its pre-war levels. Conflict, displacement, terrorism, targeted persecution, and economic collapse contributed to this sharp decline.’[footnote 42]

9.2.6 An 8 January 2025 article in Lawfare Media, an American non-profit publication dedicated to national security issues, noted that the declining number of Christians in Syria ‘… was not due to massacres or systemic discrimination – Christians received favorable treatment under the Assad regime – but largely due to emigration. Many young Christians feel unappreciated and unwelcome in Syria.’[footnote 43]

9.3 Druze

9.3.1 The Druze (or al-Muwahhidun[footnote 44]) make up 3 to 4% of the population[footnote 45][footnote 46] [around 715,000], and are the third largest religious minority in Syria.[footnote 47] The European Union Agency for Asylum (EUAA), referencing a 2020 EUAA report, noted ‘They are described as an ethnicity that exists both as a tribe and a religious sect.’[footnote 48] MRG stated that ‘Druze are ethnically Arab and Arabic speaking. Their monotheistic religion incorporates many beliefs from Islam, Judaism and Christianity, and is also influenced by Greek philosophy and Hinduism. Druze have not proselytized since the 11th century, and the religion remains closed to outsiders.’[footnote 49]

9.4 Shia Muslims

9.4.1 Alawite (Alawi), Ismaili and Shia Muslims constitute 13% of the population.[footnote 50] [footnote 51]

9.4.2 The Alawites (Alawi), declared a branch of Shia Islam by Iranian Mullahs in the 1970’s[footnote 52], and the sect of deposed leader Bashar Assad and his family[footnote 53], made up around 10% of the population [around 2.4 million], according to DW.[footnote 54] The CIA World Factbook indicated that Alawites, as an ethnic group, comprised 15% of the population[footnote 55] [about 3.5 million]. Alawites were Syria’s largest religious minority.[footnote 56] (For further information on Alawites see the Country Policy and Information Note on Syria: Alawites and Actual or Perceived Assadists).

9.4.3 According to a DW article of 18 December 2024, Shia Muslims made up about 3% of the population [approximately 715,000].[footnote 57] Sources indicated the composition of Shias (Shiites), aside from Alawites, were Shia (Shiite) Twelvers and Ismailis.[footnote 58] [footnote 59]

9.4.4 According to MRG, Ismailis ‘generally follow the religious practice of the Shi’a Twelvers in prayers, fasts, and Quranic observations.’[footnote 60]

10. Geographical locations

10.1 Maps

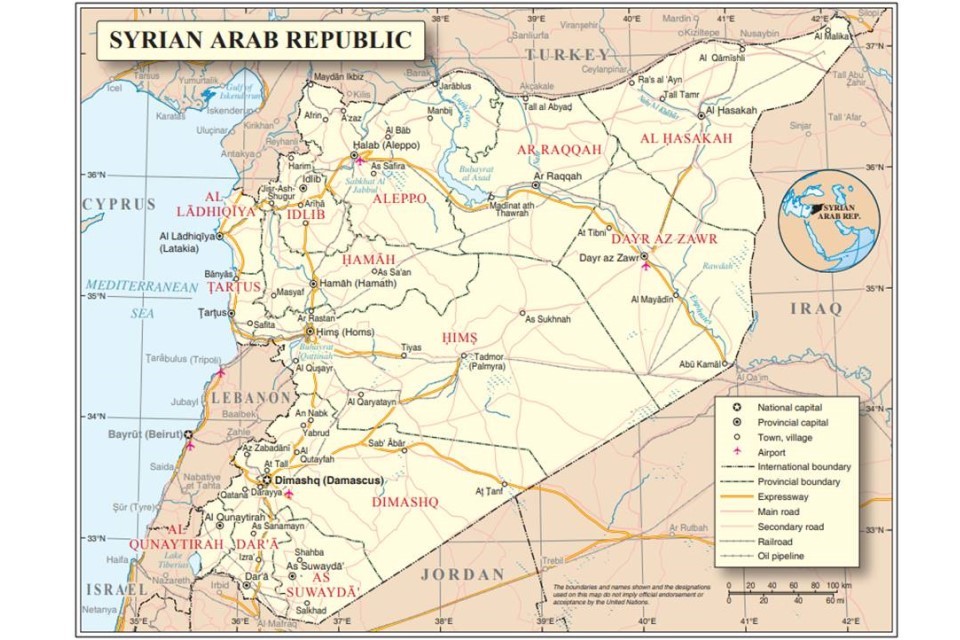

NOTE: The maps in this section are not intended to reflect the UK Government’s views of any boundaries.

10.1.1 Map of Syria by UN Geospatial.[footnote 61]

Map of Syria

10.1.2 In a report published by The Washington Institute in 2018, Fabrice Balanche, associate professor and research director at the University of Lyon 2, and adjunct fellow at The Washington Institute[footnote 62], created a map, based on his geographic information system (GIS) database and related work[footnote 63], showing Syria’s sectarian and ethnic distribution in 2011:

10.1.3 For maps of territorial control, see the Country Policy and Information Note on Syria: Security situation.

10.2 Geographical locations of Christians

10.2.1 MRG’s profile of Syria from January 2025 noted:

‘Prior to the disruption following the Arab Spring [in 2010], Greek Orthodox Christians and Greek Catholics were concentrated in and around Damascus, Latakia and the neighbouring coastal region. Syriac Orthodox Christians were located mainly in the Jazira region, Homs, Aleppo and Damascus, and Syrian Catholics in small communities mainly in Aleppo, Hasaka and Damascus. Historically, there was also a small community of Maronite Christians, mainly in the Aleppo region.’[footnote 65]

10.2.2 According to the USSD IRF Report 2023, ‘Most Christians continue to live in and around Damascus, Aleppo, Homs, Hama, and Latakia, or in Hasakah Governorate in the northeast of the country.’[footnote 66]

10.2.3 In an article of 24 December 2024, The New Arab quoted Basil Qas Nasrallah, a Christian and former advisor to Syria’s then [Grand] Mufti Badr al-Din Hassoun (the highest Islamic authority in Syria before the position was abolished in 2021[footnote 67]), saying ‘Aleppo alone is home to 20,000 Christians.’[footnote 68] Arab News reported on 13 December 2024 that, according to community leaders, 30,000 Christians remained in Aleppo compared to the 200,000 who lived their prior to 2011.[footnote 69]

10.2.4 ICC explained in January 2025 that, ‘Even with HTS forces taking control of Damascus, Syria remains divided into multiple zones, as it has been for several years. Christians, too, are not evenly distributed throughout the country. Most of Syria’s remaining Christians are concentrated in major cities like Damascus, Aleppo, and Homs, with smaller communities in villages west of Homs and Hama and northeastern cities such as Hasakeh and Qamishli.’[footnote 70]

10.3 Geographical locations of Druze

10.3.1 Lawfare Media reported in January 2025 that the Druze ‘… have traditionally enjoyed a form of de facto autonomy in the Suwayda [also spelt Suweida[footnote 71], or Sweida[footnote 72]] province in southern Syria.’[footnote 73] MRG stated ‘The Druze community is traditionally located primarily in Jabal Druze [in Suweida governorate[footnote 74]] on the southern border abutting Jordan.’[footnote 75] In 2018 MRG noted that the Druze were also located in ‘… seventeen villages in Jabal al-A’la, roughly midway between Aleppo and Antioch in the north-west, and four villages just south of Damascus.’[footnote 76]

10.3.2 Map, published by the Associated Press (AP) on 2 May 2025, showing areas inhabited by the Druze:

10.3.3 See also Situation for minorities post-Assad regime – Druze.

10.4 Geographical locations of Shia Muslims

10.4.1 A report on sects and ethnic minorities by Asma Alghoul, part of a series of research papers on life in Syria before 2011, published in 2019 by Sharq.Org, a pan-Arab non-profit organisation that aims to promote and strengthen peace and pluralism throughout the Arab region and beyond[footnote 78], noted regarding Shias (Shiite Twelvers) that ‘The most prominent Shiite areas in Syria are Damascus, Zine El Abidine, Joura and El Amin. The Al-Amin neighbourhood [of Damascus] is considered the most important centre for Shiites in Syria.’[footnote 79]

10.4.2 According to MRG, Twelver Shias ‘… live in a handful of communities near Homs and to the west and north of Aleppo.’[footnote 80] The USSD IRF Report 2023 stated that ‘Twelver Shia Muslims generally live in and around Damascus, Aleppo, and Homs.’[footnote 81]

10.4.3 Alghoul noted regarding Ismailis that ‘The city of Salamiyah, located thirty kilometres from Hama in the centre of Syria is the capital of the Ismaili community in Syria and the Middle East generally.’[footnote 82]

10.4.4 Simerg, an independent initiative dedicated to Ismaili Muslims, the Aga Khan – their Hereditary Imam – and the Ismaili Imamat, and Islam in general, noted in a 10 December 2024 article about the situation of Ismailis in Syria, that they lived ‘… primarily in Salamiyah city but also in other parts of the country…’[footnote 83] Simerg’s annotated a map of Syria (2007) showing Salamiyah marked with an arrow.[footnote 84]

11. Situation for minorities under the Assad regime

11.1 Christians under the Assad regime

11.1.1 A 2015 article by BBC News gave a brief overview of Christians prior to Syria’s civil war:

‘Despite their minority status, Christians have long been among Syria’s elite. They have been represented in many of the political groups which have vied for control of the country, including the secular Arab nationalist and socialist movements which eventually came to the fore.

‘The founder of the Baath Party, which has ruled Syria since 1963, was a Christian, and Christians rose to senior positions in the party, government and security forces, although they are generally not seen to have any real power compared with their Alawite and Sunni colleagues.

‘Although, like other Syrians, they had very limited civil and political freedoms, Christians are believed to have valued the rights and protection accorded to minorities by Hafez al-Assad, who was president between 1971 and 2000, and by his son Bashar …

‘When pro-democracy protests erupted in Syria in March 2011, many Christians were cautious and tried to avoid taking sides. However, as the government crackdown intensified and opposition supporters took up arms, they were gradually drawn into the conflict.’[footnote 85]

11.1.2 An 18 December 2024 article in The Conversation on Syria’s minorities, by Ramazan Kılınç, Professor of Political Science at Kennesaw State University, noted:

‘The Assad regime … developed mutually beneficial relationships with the Christian minority. Christians were provided access to government positions and economic opportunities, particularly in urban economic hubs such as Damascus and Aleppo. They were given preferential treatment in securing business licenses and trade opportunities. In return, most refrained from supporting opposition movements, contributed to the regime’s public image and cooperated with the government.’[footnote 86]

11.1.3 Middle East Eye reported on 14 March 2021, ‘While much of Syria’s Christian leadership has indeed opted to side with the Syrian government, untold numbers of Syrian Christians don’t support it, while others were active members of the opposition.’[footnote 87]

11.1.4 In their Country Guidance Syria, published April 2024, the EUAA’s COI summary on Christians, last updated February 2023, referenced earlier EUAA COI reports mostly from 2020 and 2022, which described the situation at that time.[footnote 88] The report noted that Christians were targeted by various actors:

‘More than 100 attacks by the GoS forces, opposition armed groups, ISIL, HTS and other parties on Christian churches were reported since the beginning of the conflict. In July 2019, ISIL claimed responsibility for suicide attacks in a church, killing 12 people in Qamishli and for the death of a pastor in Deir Ez-Zor governorate in November 2019 … Recent information on the targeting of Christians in GoS controlled areas could not be found. Individuals converted to Christianity reportedly faced threats in areas under control by Turkish forces and the SNA [Syrian National Army].

‘In Idlib HTS seized properties and churches of Christians and restrict their right to worship and prohibited Christians who fled their homes in Idlib from appointing someone to appeal against rulings handed by Sharia courts regarding their property. “Islamist factions” operating in Idlib governorate imposed so-called “jizya” taxes (a tax historically imposed on non-Muslims by Muslim rulers) on Christians, to pressure them to leave their homes …

‘Christians are allowed to operate some public schools. In Kurdish-controlled areas, ethno-religious minorities were generally able to openly express and exercise their religious beliefs, including converting to other religion. Closure of Christian schools after their refusal to teach courses according to the Kurdish curriculum was reported from 2020 … Concerns were expressed by Syriac Christians regarding the school curriculum. Students, teachers and members of the Syriac Christian Orthodox Creed Council were arrested by SDF [Syrian Democratic Forces] in September 2021 after having criticised the Kurdish curriculum and refused to adopt it …

‘Christians also faced threats in areas under Turkish control. Detention and charges with apostasy were reported in Afrin.’[footnote 89]

11.1.5 On 1 March 2025, Neil Hauer – a journalist who has spent time in Syria[footnote 90] – posted on X that he had ‘Met with an Armenian intellectual in Aleppo today. Even as a member of a (Christian) minority, he said to me, “I don’t understand why all these Western politicians are coming here and talking about ‘community rights.’ We are all just Syrians - I don’t need something special.”’[footnote 91]

On 2 March 2025 he posted that ‘Zarmik Boghikian is editor-in-chief at Kantsasar (Gandzasar), Aleppo’s only Armenian-language newspaper. She says that the 25,000-strong Armenian population of the city is under no threat from Syria’s new authorities. “All communities of Aleppo have always been one big family.”’[footnote 92] And that ‘A few days in Aleppo shows how true this statement is. Armenians are well-integrated, with shops and churches (signs in both Armenian and Arabic) across the neighbourhoods of Aziziyeh and Midan. Locals consider the mere question of interethnic/religious conflict almost ludicrous.’[footnote 93]

11.2 Druze under the Assad regime

11.2.1 The EUAA’s COI summary on the Druze in their Country Guidance Syria, referenced earlier EUAA COI reports mostly from 2020, which described the situation at that time.[footnote 94] The report noted:

‘The majority of the Druze remained neutral in the Syrian conflict although a source noted that there were groups of Druze who either supported the GoS [Government of Syria] or the opposition …

‘The Druze population in Sweida has been treated with “caution” by the GoS as a “politically sensitive minority”, and large-scale mass arrests and bombings have largely been avoided in Sweida. The neutrality of the Druze during the conflict contributed to the cessation of compulsory and reserve recruitment by the government forces. However, 50 000 individuals were reportedly wanted for the military service and a large number of them joined local militias instead. Since mid-2018, the GoS and its allies were increasingly pressuring Sweida to resolve the issue of the Druze youths absconding from their military service. Following the July 2018 ISIL [Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant] attacks in Sweida, the GoS temporarily stopped putting pressure on Sweida concerning this matter …

‘The Druze were targeted by the ISIL with an attack that resulted in the death of 300 people and the kidnapping of 20 women and 16 children, who were released later following negotiations, ransom and exchange of prisoners, while two died in captivity and 1 person was executed … The Druze were also persecuted by Jabhat al-Nusrah, forcing large groups of Druze to flee from Jabal Al-Summaq in the Idlib governorate. Another source reported that the Druze of Qalb Lawza in Idlib were forced to convert to Islam by HTS …

‘According to other sources, religious minorities such as Druze [were] treated fairly well by both the authorities and the opposition groups and were not subjected to any interrogation or checks at the checkpoints in Damascus …’[footnote 95]

11.2.2 Ramazan Kılınç’s 18 December 2024 article in The Conversation – which describes itself as ‘an independent source of news analysis and informed comment written by academic experts, working with professional journalists who help share their knowledge with the world’[footnote 96] – noted, ‘The Druze, historically marginalized in Syria due to their beliefs that combine elements of Islam with pre-Islamic beliefs, found a degree of protection under the Assad regime in return for Druze support.’[footnote 97]

11.2.3 On 22 December 2024 BBC News reporters travelled 70 miles south-east of Damascus to the city of Suweida, ‘… home to most of Syria’s Druze population.’[footnote 98] The report noted that many Druze were loyal to the Assad regime, believing it would protect minorities. However, opposition grew, leading to protests in Suweida’s central square since August 2023. Activist Wajiha al-Hajjar suggested the regime avoided violent crackdowns to maintain its image but restricted civil rights and movement of Druze instead.[footnote 99]

11.3 Shia Muslims under the Assad regime

11.3.1 Reuters reported on 13 December 2024 that ‘Shi’ite communities have often been on the frontline of Syria’s 13-year civil war, which took on sectarian dimensions as Assad, from the minority Alawite faith, mobilised regional Shi’ite allies, including Lebanon’s Hezbollah, to help fight Sunni rebels.’[footnote 100]

11.3.2 Describing the profile of Shias fleeing Syria for Lebanon after the fall of Assad, Reuters noted ‘Many of the Shi’ites at the border were from Sayyeda Zeinab, a Damascus district home to a Shi’ite shrine where fighters from Hezbollah and other Shi’ite militias were based. Supported by Iran’s Revolutionary Guards, the Shi’ite militias also came from Iraq and Afghanistan, and recruited some Syrian Shi’ites.’[footnote 101]

11.3.3 The EUAA’s COI summary on Sunni Arabs in their Country Guidance Syria, referenced earlier EUAA COI reports mostly from 2020 and 2022, which described the situation at that time.[footnote 102] The report noted that whilst Sunni Arabs in Damascus reportedly lacked essential services such as electricity and water, Shia-inhabited neighbourhoods did not face the same issues.[footnote 103]

12. Situation for minorities post-Assad regime

12.1 General or unspecific reporting on ‘minorities’

12.1.1 On 14 January 2025, independent research and analysis organisation, International Crisis Group (ICG), reported that:

‘Documented instances of overtly sectarian vigilantism and humiliating treatment are sharpening those fears and providing fertile ground for disinformation campaigns aimed at depicting the new Syrian order as an existential threat to minorities. Armed groups and individuals, by most accounts separate from HTS, have engaged in frequent killings, kidnappings and looting, targeting minority individuals. The overstretched HTS forces often have been unable to prevent these acts, leading to the risk that locals will take matters into their own hands.’[footnote 104] However, the report did not specify how they were documented, or by whom, or provide any numerical data to show what was meant by ‘frequent’.

12.1.2 On 30 January 2025, ICG’s summary of Syria provided updated analysis which indicated the situation was more nuanced than in their earlier report:

‘In areas with substantial minority populations, such as the Homs, Hama, Tartous and Latakia provinces, these incidents have a particularly destabilising impact, especially where Sunni and Alawite villages and neighbourhoods sit side by side. The Assad regime disproportionately recruited from the Alawite community to staff its security forces and military, especially at senior levels, and individuals have been targeted in retribution for alleged complicity in the deposed government’s crimes. Local armed groups outside HTS control have been implicated in several killings and kidnappings. Witnesses usually cannot say who committed these crimes, as distinguishing among the various factions is difficult. Compounding pre-existing sectarian tensions, these incidents have fuelled perceptions that entire communities are under attack.

‘While HTS has acted to improve security, its forces appear to be stretched thin. In many cases, the Damascus authorities have reined in violent factions, arresting perpetrators, but their efforts are often reactive.’[footnote 105]

12.1.3 On 29 January 2025, Syria Direct – which describes itself as ‘an independent, nonprofit media and training organization [based in Germany] … dedicated to telling Syrian stories and mentoring Syrian journalists in accordance with the highest editorial and ethical standards of journalism’[footnote 106] – reported that ‘Alongside concerns over the shape of the state, Syria has seen an increase in hate speech, particularly on social media.’[footnote 107] However, the source did not give examples or explain the groups the hate speech was directed at.

12.1.4 The same source added that ‘… there have been reprisals too, though limited and mainly targeting people accused of committing war crimes under the Assad regime rather than exclusively for their ethnic or religious backgrounds. Still, such attacks reinforce fears among minorities, particularly members of the Alawite sect to which the Assad family belongs.’[footnote 108]

12.1.5 On 30 January 2025, New Lines Magazine reported that:

‘Since the HTS-led takeover of most of the country, much concern has been voiced by the international community and Syrian civil society about possible acts of vengeance or the targeting of minorities, which were long seen as having enjoyed preferential treatment from the former regime.

‘Thus far, such incidents seem isolated. The current government seems to be quietly taking action against perpetrators, though a culture restrained by decades of heavy-handed media restrictions means it is difficult to ascertain facts on the ground in a timely manner.’[footnote 109]

12.1.6 The Economist’s article of 13 February 2025 noted ‘Ziad Kashu, a Christian activist, says he fears the rise of organised crime and gangs far more than a sectarian explosion. Kidnapping for ransom, he says, became a lucrative line of business during the final years of the Assad regime and has remained so. Creating better job opportunities might reduce young people’s propensity to turn to crime or revenge, he suggests: “The solution is economic.”.’[footnote 110]

12.1.7 Gregory Waters – who describes himself in his profile as ‘Writes about Syria, Researcher @syrian_archive, Analyst @FightExtremism, Non-Resident Scholar @MEI_Syria, Former consultant @CrisisGroup’[footnote 111] – gave a detailed summary of his experience of 3 weeks in Syria. His posts included a reflection (on 11 February 2025) that ‘“fear” remains the dominant feeling across every community visited so far. But unlike in December it’s not fear of executions or violence in this moment, but fear of the uncertainty of the future, of the violence & loss of rights that could come depending how the govt forms.’[footnote 112]

12.1.8 On 21 February 2025, a special correspondent for American daily news programme, PBS News Hour, interviewed various minorities in Damascus to gain their views on the emerging situation, a transcript of which was available.

12.2 Christian post-Assad

12.2.1 ICC’s January 2025 article opined an uncertain future for Christians under HTS, adding, ‘HTS, formerly known as Al-Nusra Front and once an offshoot of Al-Qaida until they split in 2016, had a history of persecuting Christians in areas they controlled. However, HTS now claims to aim for a peaceful transition that promises security, prosperity, and inclusion for all Syrians, including … Christians …’[footnote 113]

12.2.2 A Church Times article of 10 December 2024 cited the Apostolic Nuncio[footnote 114] to Syria, Cardinal Mario Zenari, as having said ‘“The rebels [HTS] met with the bishops in Aleppo immediately after their victory, assuring them that they would respect the various religious denominations and Christians. We hope they will keep this promise and move toward reconciliation”.’[footnote 115]

12.2.3 A 20 December 2024 article published by the American think tank, Atlantic Council, explained that:

‘In Aleppo, HTS contacted prominent Christian leaders and clergy across various denominations to repair strained relations and foster a sense of security. These meetings were not superficial; they included discussions on tangible grievances, such as the injustices faced by Christians in Jisr al-Shughur a year prior. Some of these grievances have since been addressed mainly through accountability and restoring properties to their rightful owners, an unprecedented move that underscores the leadership’s understanding of the need for inclusivity, albeit carefully managed.’[footnote 116]

12.2.4 The Church Times article of 10 December 2024 noted ‘A Christian who wished to remain anonymous told the news agency AFP: “To our great surprise, the behaviour of the new occupiers of Aleppo is completely different from what we expected. All the speeches they give are to say that they are not here to make us suffer. They are here to help us. They say, ‘All we want is to overthrow Assad’s regime”.’[footnote 117]

12.2.5 On 12 December 2024, ICG noted – without being specific to Christians – that ‘Early indications from the country’s majority-Alawite areas are encouraging, as people seem to be heeding HTS’s call not to … harm members of ethnic and religious minorities.’[footnote 118]

12.2.6 The New Arab article of 24 December 2024 cited ‘Syrian political analyst Muhammad Al-Mousawi’ who implied that HTS’ apparent tolerance toward Christians was an image to gain Western support and improve their international reputation.[footnote 119] The article also quoted Basil Qas Nasrallah, Christian and former advisor to Mufti Badr al-Din Hassoun for 15 years, who offered a more optimistic view:

‘While acknowledging that “words alone are not enough to erase years of fear, especially since the previous regime set itself up and convinced us that it was the protector of minorities,” he finds HTS’s reassurances credible.

‘Nasrallah, who recently received a supportive delegation from Aleppo’s Sharia Council promising protection of Christmas celebrations, rejects the framing of Christians as a vulnerable minority.

‘“The word minorities is facetious to me. We are not minorities. …” he asserts, emphasising that he sees no evidence of a systematic plot to displace Christians or other religious groups from Syria.’[footnote 120]

12.2.7 On 25 December 2024, NPR – ‘an independent, nonprofit media organization’[footnote 121] – interviewed one of their reporters, Hadeel Al-Shalchi, in Damascus, who explained that:

‘… even though this is a Muslim-majority country, Syrians are taking Christmas pretty seriously. Since I arrived in Damascus almost three weeks ago, after the regime fell, there’s been Christmas decorations in hotels and restaurants. Christmas trees popped up in squares in the city. There was a cardboard nativity scene being built when I visited Bab Tuma, the Christian neighborhood of Damascus. There was even this guy dressed in an ill-fitting Santa Claus outfit, selling balloons and taking pictures with kids. It’s also a public holiday.’[footnote 122]

12.2.8 However, she also explained ‘… churches were pretty empty [on Christmas Day],’ and that this may reflect the uncertainty Christians were feeling since HTS took power.[footnote 123] The report gave contrasting views of how others were feeling, including citing one person who told Al-Shalchi that they were ‘worried the new government may impose Islamist rule.’ And ‘Another woman was adamant to tell me on the record, you know, we aren’t afraid. Christians are an essential part of this country. But then she pushed my mic away and said, don’t record this, but the church is telling us to keep a low profile.’[footnote 124]

12.2.9 Al-Shalchi also explained that:

‘[Damascus governor, Maher Marwan] said that his message to Christians was that they were all on the same path, that he wanted equality for all, dignity for all. He said that he wouldn’t deprive Christians from those rights. He also told me that he had instructed some of his security forces to guard the Christian quarters. And … our NPR team witnessed this one night when we went to Bab Tuma. An armed man wearing fatigues tried to enter the market area, and he was actually stopped by another armed man who looked like he was from HTS. So, you know, there appears to be some attempt to provide some order. But, you know, like worried Christians told me, they want to keep seeing actions on the ground and not just words.’[footnote 125]

12.2.10 On 22 December 2024, BBC News reported that:

‘In the past week, the Archbishop of Homs, Jacques Murad, told the BBC there had already been three meetings with HTS, and they had been able to express their views and concerns honestly.

‘So far, the signs are re-assuring for many Christians.

‘Bars and restaurants serving alcohol are open in the Christian quarter of Old Damascus and in other parts of the city. Christmas decorations are also up in many places.’[footnote 126]

12.2.11 A 30 December 2024 article in Al Jazeera referenced comments from ‘an older couple’ and noted that ‘as Christians, they worry about their vulnerability as minorities.’ and that they did not wish to have their photographs taken. But Al Jazeera quoted them as saying ‘Until now, the new administration … [HTS] had made only positive moves …’[footnote 127] The same report cited ‘Father Hanna Jallouf, the Apostolic Vicar of Aleppo and the Roman Catholic Church’s leading religious figure in Syria’, who had ‘received assurances that Christian religious symbols would not be touched.’ Father Jallouf said of HTS leader, Ahmed al-Sharaa, whom he had met, that he was ‘… first of all honest and wants what is best for his country.’[footnote 128]

12.2.12 An article on BBC Monitoring (BBC-M) reported that, on 31 December 2024, ‘Syria’s de facto leader Ahmed al-Sharaa met senior clerics from the country’s various Christian denominations, domestic media reported.’[footnote 129] The report included an image from social media site X, remarking ‘A post on X by the state news agency Sana said that the “leader of the new Syrian administration” had met a delegation from the Christian community in the capital, Damascus.’[footnote 130]

12.2.13 According to BBC-M, ‘The post, which included pictures showing Sharaa with Catholic, Orthodox and Anglican clerics, provided no further details.’[footnote 131] The same article noted that ‘The Istanbul-based Syria TV reported that the meeting was attended by clerics from the country’s Roman Orthodox, Roman Catholic, Syriac Orthodox, Syriac Catholic, Armenian Catholic, Maronite, Anglican and Latin churches.’[footnote 132]

12.2.14 Though not referring to Christians specifically, DW reported on 3 January 2025 that ‘So far at least, even as security remains a significant concern for civilians, there seem to have been comparatively few verified cases of vigilante justice or religious persecution by those currently in power. And, in fact, that number is dwarfed by alleged and unverified instances of abuse seen online, the majority of which are misleading or fake, various fact-checking organizations suggest.’[footnote 133]

12.2.15 On 6 January 2025, in an interview on Christianity Today’s ‘The Bulletin Podcast’, covering the situation for Christians in Syria, Robert Nicholson – editor at large of Providence magazine and founder of the Philos Project and co-founder of Passages Israel – explained how he was ‘not optimistic’ and speculated that he ‘had been around too long to believe a kind of representative, quasi liberal government will emerge in Damascus’.[footnote 134] However, he did note that ‘… Christians have been at least allowed to continue all of the things that they’re doing’[footnote 135] and that he ‘[hadn’t] heard a whole lot of stories about Christians being oppressed. I know they’re scared, I know they’re very scared about what will happen when the shoe drops, but right now things are okay.’[footnote 136]

12.2.16 An 8 January 2025 article in Lawfare Media, noted ‘Since the fall of the Assad regime, Syria has witnessed numerous troubling incidents. Churches have been looted and their windows shattered, though HTS fighters were able to recover most of the stolen items and repair the damage. A Christmas tree in a Christian town was set on fire, but the rebels responsible were apprehended, and the tree was replaced. Still, Christian communities throughout the country remain understandably concerned.’[footnote 137]

12.2.17 Catholic journal, America Magazine, reported on 30 January 2025 that, ‘With the exception of the tree arson, Christmas in Damascus and Aleppo was celebrated normally this year [2024]. Residents said they did not perceive any pressure from the new government during the holiday to curtail public celebrations. The only notable difference was the presence of H.T.S. militia members guarding churches and the main entrances to Christian neighborhoods.’[footnote 138] The report added ‘Since the fall of Mr. al-Assad, Christians in the Bab Touma district of Damascus, named for Saint Thomas the Apostle, go about their daily lives as before. H.T.S. fighters are stationed at the boundaries of the mostly Christian neighborhood to protect it, joined by volunteers from the neighborhood itself.’[footnote 139]

12.2.18 On 13 January 2025, the Catholic News Agency (CNA) reported that ‘More than a month after Syria’s political shift, Christians there are vocalizing a sense of relief as initial assurances for their safety and security by the de facto government have reportedly been provided.’[footnote 140] And that ‘Over the past month, Christians have largely been spared from targeted incidents, with a few isolated exceptions. For example, in Aleppo’s predominantly Christian Sulaymaniyah neighborhood, a man used loudspeakers to urge women to wear hijabs and avoid mingling with men. Authorities have generally handled these incidents with wisdom.’[footnote 141]

12.2.19 On 29 January 2025, Syria Direct reported that:

‘In Aleppo city, although HTS has given assurances and made good on its promises so far, there is still “an obsession with the form of the state” among Armenians and Christians, Armenak Tokmajyan, a researcher at the Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center in Beirut, said.

‘“The Armenian community in Aleppo has not been targeted,” Tokmajyan, who is from the community, added. “From this, the concerns can be explained as not being security concerns, or concerns that whoever rules Syria will target Armenians as a community,” but rather about “the form of the state, ways of life and culture,” he explained. “Will hijab become mandatory? Will males and females be separated in Armenian schools?”

‘While the Assad regime was “unjust and cruel,” at the same time “it was a source of safety for most minorities,” Nader said. He fears the “Islamization of the state.”’[footnote 142]

12.3 Druze post-Assad

12.3.1 An article dated 20 December 2024 in Atlantic Council noted that HTS leadership met with Druze representatives in Idlib Governate’s Jabal al-Summaq area ‘… to rebuild trust and ensure that their communities were not targeted.’[footnote 143] In addition, the same report noted that on 17 December 2024, HTS leaders spoke with ‘… prominent figures from the Druze community in Suwayda and Jabal al-Arab, sending assurances of safety and future inclusion.’[footnote 144]

12.3.2 A 22 December 2024 BBC News article noted the daily rallies that took place at Suweida’s (Suwayda) central square[footnote 145], which began in August 2023 (with occasional protests between June 2020 and January 2023), demanding increased public services.[footnote 146] [footnote 147] Those calls continued, and also celebrated the regime’s fall.[footnote 148] [footnote 149] According to the BBC, the Druze community, who had quasi-autonomy under Assad, seeks to preserve this status and protect their rights under HTS.[footnote 150]

12.3.3 Rudaw, a media broadcaster in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq[footnote 151], reported on 2 January 2025 that ‘Suwayda is controlled by the the Druze Rijal al-Karama (Men of Dignity) militia which was established during the Syrian conflict to protect the minority group from the threat posed by Islamic State (ISIS) militants and the former Bashar al-Assad regime’s affiliated forces.’[footnote 152]

12.3.4 A journalist from New Lines Magazine, an American publication focussing on the Middle East[footnote 153], visited Suweida in mid-December 2024 and noted that there were no HTS fighters there, ‘… neither at the entrance of the city nor guarding any of the abandoned police stations and prisons, as they do in Damascus…’.[footnote 154]

12.3.5 The same report noted that, according to a Druze commander, on 1 January 2025, a military convoy of HTS-linked fighters was refused permission to enter Suweida province by local Druze militias, ‘“If we are subjected to any aggression or anything that is imposed on us as a province, we will demand federalism,” Sheikh Bahaa al-Jamal, commander of the Druze operations in Suwayda, told Rudaw…’[footnote 155]

12.3.6 Rudaw’s 1 January 2025 report noted:

‘… the Druze spiritual leader stressed that laying down their arms depends on guaranteeing their constitutional rights. “We will not hand over our weapons until the state, constitution, and government are formed and the decentralized system is most appropriate for Syria,” Hikmat Salman al-Hijri told Rudaw.

‘But the new Syrian Defense Minister Murhaf Abu Qasra, a top HTS commander, has expressed that they do not wish to have federalism in the country or to have any area outside the control of Damascus.’[footnote 156]

12.3.7 The New Arab reported that, according to state news agency Sana, on 31 December 2024, Syria’s interim government appointed Muhsina al-Mahithawi, a member of the Druze minority, as its first female governor for Suweida. An activist from the area said al-Mahithawi was a ‘prominent figure’ in the protests against Assad’s regime.[footnote 157]

12.3.8 Agence France-Presse (AFP), cited by Daily Sabah, reported that, in a joint statement of 6 January 2025, ‘Two Druze rebel groups in Syria declared … their willingness to join a national army after anti-regime fighters ousted Bashar Assad … “We, the Men of Dignity movement and the Mountain Brigade, the two largest military factions in Sweida, announce our full readiness to merge into a military body… under the umbrella of a new national army whose goal is to protect Syria,” the groups from south Syria’s Sweida province said …’ Adding they would reject ‘any factional or sectarian army’ and had ‘no designs or roles in administrative or political affairs …’[footnote 158]

12.3.9 ICG’s Watch List 2025, dated 30 January 2025, noted that, ‘In Druze-majority Suwayda province, where factions have mostly supported the HTS-led offensive, the caretaker government has delegated security provision to local forces; Suwayda residents told Crisis Group that security in the area has improved following Assad’s fall.’[footnote 159]

12.3.10 Clashes between security forces and locals in Jaramana, a suburb of Damascus with a majority Druze population, which resulted in the killing of at least one security officer at a checkpoint set up by Druze forces, were reported to have occurred on or around the beginning of March 2025.[footnote 160] [footnote 161] [footnote 162] Syrian security forces were deployed to the incident after local militias refused to hand over the suspects but calm was restored following negotiations between Ministry of Interior forces and local leaders.[footnote 163] [footnote 164] [footnote 165]

13.3.11 On 11 March 2024, the New Arab published an article, which stated:

‘The Syrian government has reached an agreement with the residents and elders of Suweida to fully integrate the predominantly Druze province into the institutions of the state, according to reports.

‘The agreement will see Suweida’s security services put under the authority of the Syrian ministry of interior with the police force manned with members of the local population, Al Jazeera reports, which follows an agreement with the Kurdish-dominated Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) on Monday evening.

‘The Syrian government will also appoint a governor and a police chief, who are not necessarily required to be from Suweida.

‘Hikmat al-Hijri, the spiritual leader of the Druze community in Syria, has previously affirmed their commitment to a unified Syrian state and has firmly rejected any plans to divide the country, stressing their project is a purely national Syrian one.

‘Al-Hijri said that the “unity of Syria, its land and people” is a priority and the Druze community is not seeking separation or divisions, only to preserve their roots.

‘… Talks between the interim Syrian President Ahmed al-Sharaa and dignitaries representing the people of Suweida had taken place in Damascus before the agreement.

‘… Al-Sharaa, who is the former leader of HTS, has sought to dispel the fears of the Druze in Suweida, saying his administration and any future Syrian government must represent and tolerate all minority faiths.’[footnote 166]

13.2.12 An update by Etana, an ‘independent organisation … [that] serves as a civil and diplomatic service for Syrians’[footnote 167], published on 21 March 2025 stated that ‘… senior Druze cleric Sheikh Hikmat al-Hijri … publicly rejected the [constitution declaration] document in its current form, calling for a complete revision to ensure a participatory democratic system that respects Syria’s historical and cultural identity. His statement emphasized the need for a clear separation of powers, expanded local governance authority and checks on the power of the president.’[footnote 168]

13.2.13 On 28 April 2025, fighting broke out in the southern majority-Druze Damascus suburb of Jaramana between pro-government Sunni gunmen and Druze factions, following an alleged insult of the Prophet Mohammad by a Druze leader.[footnote 169] [footnote 170]

13.2.14 The ICG reported that the suburb was:

‘… jointly controlled by a Druze faction and General Security, the security force that has operated across government-held Syria since the Assad regime’s fall late last year. Attackers launched mortars into the suburb, with subsequent clashes killing at least six Druze fighters and seven Sunni gunmen.

‘Although the clashes stopped after General Security created a buffer zone around the area, that did not end the violence. Late on 29 April, groups armed with machine guns and mortars launched an attack against Ashrafieh Sahnaya, another Druze-majority suburb that is also under the joint control of General Security and the same Druze faction.

‘The following day, as fighting persisted, Israel stepped in, launching drone strikes on government forces, reportedly as a “warning”; Israeli officials had said in February [2025] that they would act forcefully to protect the Druze, many of whom live in Syria and Israel. At some stage, the Syrian authorities also began to shift the finger of blame for the unrest, claiming that the Druze faction – not their Sunni attackers – was clashing with General Security. Amid claims and counter-claims, the unrest eventually appeared to die down in the evening of 30 April as Druze representatives and the government negotiated a truce.’[footnote 171]

12.3.15 The clashes reportedly resulted in the deaths of up to 100 people.[footnote 172] [footnote 173] [footnote 174]

12.4 Shia Muslims post-Assad

12.4.1 On 13 December 2024, Reuters reported that:

‘Tens of thousands of Syrians, mostly Shi’ite Muslims, have fled to Lebanon since Sunni Muslim Islamists toppled Bashar al-Assad, fearing persecution despite assurances from the new rulers in Damascus that they will be safe, a Lebanese official said.

‘At the border with Lebanon, where thousands of people were trying to leave Syria on Thursday, a dozen Shi’ite Muslims interviewed by Reuters described threats made against them, sometimes in person but mostly on social media.’[footnote 175] The source did not expand on or explain whom the threats originated from.

12.4.2 Reuters reporters spoke to Shia Muslims waiting at the Lebanese border. A 39-year-old soldier who served alongside his brother in Assad’s army, said the sudden regime collapse left them ‘… scrambling to decide whether to stay or go. They fled to Damascus where they received threats, he said, without elaborating. “We are afraid of sectarian killings …”, he told Reuters, adding that minorities had been left without protection.[footnote 176]

12.4.3 Reuters were told by a Shia nurse, who was waiting to cross the border with her niece and son, that when the regime fell she fled Damasus to rural areas, and ‘When she returned, she found her house looted and torched. She and others said that armed, masked men raided their homes and ordered them at gunpoint to leave, or be killed. “They took our car because they said it’s theirs. You daren’t say a word. We left everything and fled.” Reuters could not immediately reach HTS officials for comment on threats received by minorities.’[footnote 177]

12.4.4 In contrast, Reuters reported ‘In parts of Syria’s north, however, some residents who fled when HTS went on the offensive in late November said they now felt confident to return …, a Shi’ite father of three told Reuters, next to the main mosque in the Shi’ite town of Nubl, where Hezbollah once stationed fighters. He praised HTS leader Sharaa for his efforts to protect the community, saying he “enabled us to come to our houses”.’[footnote 178] Although another Shia, who declined to speak on camera, expressed concern at the new Sunni leadership, saying ‘“We don’t know what will happen”.’[footnote 179]

12.4.5 A 20 December 2024 article in Atlantic Council noted, regarding the fall of the Assad Regime and change of administration led by HTS, that, ‘For the Ismailis of Salamiyah, the transition of power was remarkably smooth, as the town surrendered without violence. This cooperative handover reflects longstanding tensions between the Ismaili community and the Assad regime, which had marginalized them over the years.’[footnote 180]

12.4.6 Reporting from Damascus on 22 December 2024, BBC News met with a Shia Muslim lawyer who said: ‘“There’s no doubt that there’s anticipation and anxiety. The signs that come from HTS are good, but we must wait and watch … It’s not possible to know the opinions of all Shia but there is a concern about a scenario similar to Libya or Iraq. I believe, though, that Syria is different. Syrian society has been diverse for a very long time”.’[footnote 181]

12.4.7 MRG noted in January 2025 that ‘According to media reports at the time of the final assault on the Assad regime’s defenses, HTS sought to assure Iran that Shi’a sacred sites would not be damaged or destroyed.’[footnote 182]

12.4.8 On 11 January 2025, Al Jazeera reported that, according to state news agency Sana, ‘Syrian authorities have foiled an attempt by ISIL (ISIS) fighters to blow up a revered Shia shrine in a Damascus suburb…’[footnote 183] Channel 4 News had previously reported on 11 December 2024 that the Zaynab (Sayyida Zeinab[footnote 184]) shrine was being guarded by HTS forces to ensure its safety.[footnote 185]

12.5 The national dialogue committee

12.5.1 A 7-member national dialogue committee, set up on 12 February 2025 by the interim government for a forthcoming National Dialogue Conference, included a Christian woman[footnote 186] [footnote 187], but no other religious minorities.[footnote 188] Attendees of the committee’s first session, held on 16 February 2025, included Christians, Shia and Alawites, as well as Sunni Muslims.[footnote 189]

13. Limits on reporting, disinformation and misinformation

For general commentary on the limits on reporting, as well as dis- and mis-information – and the effect it is having – see the Country Policy and Information Note Syria: Returnees After Fall of Al-Assad Regime.

13.1.1 Reporting, disinformation and misinformation in respect of religious minorities

13.1.1 Ahmad Askary’s 12 March 2025 report for the Levantine Press explained ‘On the ground in Syria, various individuals and minority communities have come out to try and make their voices heard against the tidal wave of disinformation.’[footnote 190] The report included the following examples:

- ‘The Shia communities of Nubl and Zahraa in north Aleppo came out in support of the government and operations against Assadist insurgents.

- ‘Spyridon Tanous, a prominent Syrian Orthodox priest has repeatedly emphasised that news on “Christian massacres” promoted by figures like Elon Musk is disinformation.

- ‘A gathering in Aleppo of Christian leaders from various denominations voicing their support for the government and ongoing security campaigns against Assadist insurgents.

- ‘Asaad Sam Hanna, A Syrian-American Christian, wrote an article on Twitter/X, clarifying that claims of oppression and/or massacres against Christians in Syria are disinformation.

- ‘A statement by Bishop Hanna Jallouf, head of Syria’s Catholic Church, affirming their support for the territorial integrity of the Syrian state, unity of its people, and support for the government in their fight against Assadist insurgents.

- ‘The Council for Christian Churches in Latakia published statements denying the rampant disinformation that Christians were being killed, and urged people to verify their information.

- ‘The Turkmen Syrian Council affirmed their support to the Syrian government and its efforts against Assadist insurgents.’[footnote 191]

13.1.2 The report added ‘Levant24 has conducted multiple interviews with Christian residents in Latakia, dismissing claims of oppression/massacres of Christians in Syria.’[footnote 192]

13.1.3 In a blog post updated on 5 January 2025, Misbar, a non-profit fact-checking platform[footnote 193], stated that: ‘In the current context of Syria, after Bashar al-Assad’s departure, conflicts between religious sects have surged, creating an atmosphere of heightened tension and division. As a result, falsehoods targeting religious minorities and communities have surfaced online, amplifying sectarian strife …’[footnote 194]

Research methodology

The country of origin information (COI) in this note has been carefully selected in accordance with the general principles of COI research as set out in the Common EU [European Union] Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI), April 2008, and the Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation’s (ACCORD), Researching Country Origin Information – Training Manual, 2024. Namely, taking into account the COI’s relevance, reliability, accuracy, balance, currency, transparency and traceability.

Sources and the information they provide are carefully considered before inclusion. Factors relevant to the assessment of the reliability of sources and information include:

- the motivation, purpose, knowledge and experience of the source

- how the information was obtained, including specific methodologies used

- the currency and detail of information

- whether the COI is consistent with and/or corroborated by other sources

Commentary may be provided on source(s) and information to help readers understand the meaning and limits of the COI.

Wherever possible, multiple sourcing is used and the COI compared to ensure that it is accurate and balanced, and provides a comprehensive and up-to-date picture of the issues relevant to this note at the time of publication.

The inclusion of a source is not, however, an endorsement of it or any view(s) expressed.

Each piece of information is referenced in a footnote.

Full details of all sources cited and consulted in compiling the note are listed alphabetically in the bibliography.

Terms of reference

The ‘Terms of Reference’ (ToR) provides a broad outline of the issues relevant to the scope of this note and forms the basis for the country information.

The following topics were identified prior to drafting as relevant and on which research was undertaken:

- Legal context

- Constitutional and legal protections for religious minorities

- Demography, population and geographic location for:

- Christians

- Shia

- Druze

- Situation for minority groups, distinguishing (wherever possible) between:

- pre- and post- fall of Assad

- non-state and HTS

- areas outside of HTS control

- Socio-economic situation, access to services

Bibliography

Sources cited

Agence France-Presse (AFP)

- Druze fighters announce decision to join Syria’s new army, 6 January 2025. Accessed: 14 February 2025

Alghoul A

- Sects and Ethnic Minorities in Syria, 2019. Accessed: 4 February 2025

Al Jazeera

-

The end of fear in Syria, 30 December 2024. Accessed: 9 January 2025

-

President al-Sharaa and no more Baath party: What else has Syria announced?, 29 January 2025. Accessed: 5 February 2025

-

Syrian forces deployed in Jaramana to end unrest, 3 March 2025. Accessed: 14 March 2025

-

Syrian intelligence says it thwarted ISIL attempt to blow up Shia shrine, 11 January 2025. Accessed: 10 February 2025

-