[Withdrawn] Sustainable warmth: protecting vulnerable households in England (accessible web version)

Published 11 February 2021

Applies to England

Ministerial foreword

In response to coronavirus (COVID-19), millions of households have stayed at home, sometimes away from loved ones, to protect the National Health Service (NHS) and save lives. A safe, warm home is clearly more important now than ever.

This strategy sets out our plan to ensure everyone can afford the energy required to keep their lights and heating on, especially during the winter. Coronavirus has resulted in many consumers seeing reduced income and therefore an increased number of households may now be struggling with their energy bills, especially as it gets colder. Some households may be new to this situation, and for others it may be that they find themselves in an even more difficult financial position than they already were.

This strategy reflects our commitment to helping the most vulnerable, and how action already taken is helping to make a real difference to fuel poverty. We already have schemes to increase the energy efficiency of homes, reducing the cost of bills whilst also contributing to Net Zero targets. The expanded Energy Company Obligation is one example of such a programme, resulting in warmer and greener homes for those most vulnerable. We are also protecting tenants against cold homes and high energy bill costs through increased energy efficiency standards.

More than ever, we need to invest in the health and wellbeing of people across England and reduce unnecessary strain on the NHS. This plan outlines schemes which aim to create warmer homes. In turn, this has potential to reduce the frequency and severity of health problems like flu, heart attacks and depression, which have all been linked to cold homes. Ensuring everyone has a warm home is one step toward reducing health inequalities and reducing the burden on the NHS over the winter.

Finally, this plan will contribute to reduced carbon emissions, through improved energy efficiency and supporting households in the move towards cleaner energy consumption, including heating. As we look ahead to the 26th United Nations Climate Change Conference, COP26 in Glasgow, we are leading the world in decarbonising homes while also protecting consumers. Instead of investing in fossil fuels, we are benefiting consumers with clean technologies which reduce demand and will enable our transition to Net Zero.

Rt Hon Kwasi Kwarteng MP

Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy

Executive summary

A household is in fuel poverty if they are on a lower income and unable to heat their home for a reasonable cost. This Government is committed to ensuring these households have access to sustainable, low-carbon warmth as we transition to Net Zero. This Fuel Poverty Strategy for England sets out our plan to:

- Invest a further £60 million to retrofit social housing and £150 million invested in the Home Upgrade Grant, contributing to the manifesto commitment to a £2.5 billion Home Upgrade Grant over this Parliament.

- Expand the Energy Company Obligation (ECO), a requirement for larger domestic energy suppliers to install heating, insulation or other energy efficiency measures in the homes of people who are low income and vulnerable or fuel poor.

- Invest in energy efficiency of households through the £2 billion Green Homes Grant, including up to £10,000 per low income household to install energy efficient and low-carbon heating measures in their homes.

- Extend the Warm Home Discount a requirement for energy companies to provide a £140 rebate on the energy bill of low income pensioners and other low income households with high energy bills, ensuring continuity for vulnerable or fuel poor consumers.

- Drive over £10 billion of investment in energy efficiency through regulatory obligations in the Private Rented Sector. Additionally, lead the way in improved energy efficiency standards through the Future Homes Standard, and the Decent Homes Standard.

Through these schemes and standards, we will drive sizeable energy bill savings. ECO3 was estimated to save low income households up to £300, the extended ECO scheme, ECO4, is expected to save households even more due to the focus on multiple measures. The proposed Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards are expected to result in £220 in average bill savings for private renters.

While we cannot design detailed schemes for the whole of the 10-year period to 2030, we are in a strong position to set out specific commitments, the fulfilment of which will underpin progress towards our vision. Where we can do this, we have done so. We expect these commitments to be refreshed over time through revisions to this strategy. In practice, exactly how fast progress is made against the milestones and the 2030 target, and in exactly what ways, will depend on a range of decisions taken over time. The existence of the interim milestones and a long-term target will be important factors in decision-making on spending and fiscal events, alongside others such as affordability and wider carbon targets.

In Chapter 1, “Who are we trying to help?”, we explain what fuel poverty means and how it is measured. Chapter 2, “The fuel poverty target for England”, explains our current, legally binding fuel poverty target and Chapter 3 sets out our interim milestones. Chapter 4, “Our strategic approach to meeting the fuel poverty target”, sets out our vision for tackling fuel poverty across England and the strategic principles which underpin our plans for tackling fuel poverty. This chapter also introduces the variety of outcomes we use to measure our progress.

Chapter 5, “How Government is meeting the challenge”, goes through the eight strategic challenges in detail, explaining how we plan to meet them. This chapter provides information on our key policies and commitments, such as the Green Homes Grant and the Energy Company Obligation.

Our final chapter, “Reviewing the strategy and scrutiny of progress”, sets out how we will remain open and transparent as we implement this strategy. Annex A sets out an easy-to-read overview of the 21 commitments made in this document.

1. Who are we trying to help?

Few people self-identify as living in fuel poverty. However, many households face challenges in heating their home, particularly over the winter months. Fuel poverty is the problem faced by households living on a low income in a home which cannot be kept warm at reasonable cost. Fuel poverty can mean making stark choices between energy and other essentials or falling into debt. For some, the result is living in a cold home, which has negative impacts on health and wellbeing.

This strategy sets out how we will tackle fuel poverty while also decarbonising buildings, ensuring that those in fuel poverty are not left behind on the move to Net Zero and, where possible, can be some of the earliest to benefit. In this chapter, we set out how fuel poverty is defined and how we will measure progress toward the fuel poverty target going forward.

A short history of fuel poverty

In 2000, the Warm Homes and Energy Conservation Act created duties for Government to tackle fuel poverty which, in its amended form, remains in force today. The Act characterises fuel poverty as the problem of someone on a “lower income [living] in a home which cannot be kept warm at reasonable cost.”

The first UK fuel poverty strategy, published in 2001, set out the way fuel poverty would be measured in practice – a household would be considered “fuel poor” if it needed to spend more than 10% of its income on energy in the home. The 10% indicator allowed fuel poverty to be measured at a national level. However, it became increasingly clear that the 10% indicator was very sensitive to energy prices. There was a danger of both underplaying the effectiveness of support schemes and undermining good scheme design. In 2011, determined to better understand the problem and to make more progress, Government commissioned Professor Sir John Hills of the London School of Economics to undertake a fully independent review of fuel poverty. The Hills Review, published in 2012, recommended the Government adopt the Low Income High Cost indicator of fuel poverty. This set out that for a household to be considered fuel poor it has:

- An income below the poverty line (including if meeting its required energy bill would push it below the poverty line), and

- Higher than typical energy costs.

Government adopted Low Income High Cost (LIHC) as the official measure of fuel poverty in the 2015 fuel poverty strategy. The LIHC indicator allowed us to measure not only the extent of the problem – how many fuel poor households there are – but also the depth of the problem – how badly affected each fuel poor household is. It achieved this by taking account of the fuel poverty gap, a measure of how much more fuel poor households need to spend to keep warm compared to typical households. The fuel poverty gap gave us a more sophisticated understanding of fuel poverty and it enabled us to focus our efforts on the nature and causes of the worst levels of fuel poverty.

As LIHC is a relative indicator, the total proportion of fuel poor households remains relatively static at 10-12%, or around 2.5 million homes. In 2018, Government undertook analysis[footnote 1] to better understand the degree of movement in and out of fuel poverty. We found that fluctuations in the average income and average energy bill can change who is considered to be fuel poor. Every year, hundreds of thousands of households can be measured as fuel poor, or stop being fuel poor, even if their circumstances have not changed.

The updated fuel poverty metric

Following consultation in 2019[footnote 2], Government is updating the way we measure fuel poverty. Our aim is to better track progress toward the statutory fuel poverty target whilst still reflecting the three key drivers of fuel poverty (low income, energy efficiency and prices). The updated measure, Low Income Low Energy Efficiency (LILEE), finds a household to be fuel poor if it:

- Has a residual income[footnote 3] below the poverty line[footnote 4] (after accounting for required fuel costs[footnote 5]) and

- Lives in a home that has an energy efficiency rating below Band C[footnote 6].

The new measure will continue to show both the extent and severity of fuel poverty through the fuel poverty gap. The key change is that LILEE considers whether a household has reached Band C or above (Bands A and B) in energy efficiency[footnote 7]. Where such households struggle with their energy bills, it is unlikely to be because their home needs more insulation.

Whilst we recognise that there are households living in energy efficiency Band A, B or C homes who are unable to afford sufficient energy to keep warm, due to a very low income, most will not significantly benefit from energy efficiency measures.

As such, households in homes that have been improved to Band C or above, will not be considered as being in our measure of fuel poverty.

We will, however, continue to consider the needs of low income vulnerable households living in Band A to C homes under our vulnerability principle, as well as the needs of fuel poor households living in Bands D to G.

Impact on statistics

The vast majority of households that are fuel poor under the LIHC measure are also considered fuel poor under LILEE (88% or 2.1 million households). Approximately 300,000 households living in Band C properties will no longer be considered fuel poor under the LILEE measure; however, this update will not affect eligibility for current policies.[footnote 8]

We note that these numbers are different to those included in the fuel poverty consultation in 2019, which referenced 2016 statistics. This is because between 2016 and 2018, an additional 1.2 million homes reached a Band C. Approximately 100,000 of these households are considered fuel poor under LIHC but are not measured as fuel poor under the new LILEE metric as they are rated Band A-C. The homes that have reached Band A-C have already been improved to our Band C target, either through Government schemes, or through private investment. Using provisional LILEE statistics, more than one million households, largely in Band D, would be newly measured as fuel poor. This would increase the aggregate, or total, fuel poverty gap because there would be more fuel poor households overall. However, it would reduce the average fuel poverty gap (defined as the reduction in fuel bill that the average fuel poor household needs in order to not be classed as fuel poor). The average fuel poverty gap would be reduced because most of the households newly measured as fuel poor would be in Band D and would tend to have lower fuel bills than the average household measured as fuel poor under the Low Income High Cost metric.

Additional methodology changes

In addition to adopting the LILEE metric, we have made some additional changes to the fuel poverty methodology. Following consultation in 2019, Government has decided to exclude Disability Living Allowance, Personal Independence Payment and Attendance Allowance from being considered as part of residual income[footnote 9]. These benefits are not means tested, and are intended to contribute to the costs of disability. By including them as residual income, the income of those receiving the benefits is artificially inflated and therefore not accurately portraying their likely income versus expenditure, including whether they are likely to be vulnerable to living in a cold home. The Department for Work and Pensions’ (DWP) Households Below Average Income publication[footnote 10] includes both data including and excluding these disability payments.

In response to the consultation, a number of stakeholders expressed that the heating regimes methodology used in the fuel poverty statistics should be updated. Government is currently updating the Standard Assessment Procedure (SAP) methodology with a modified standard heating regime. We are proposing to align the fuel poverty heating regimes with the standard set out in SAP10. We intend to implement this change in the statistics relating to the 2021 data to align with the methodology used in practice.

2. The fuel poverty target for England

The statutory fuel poverty target was set in December 2014, binding successive Governments to the following:

The fuel poverty target is to ensure that as many fuel poor homes as is reasonably practicable achieve a minimum energy efficiency rating[footnote 11] of Band C, by 2030.

This strategy sets out the approach that will be taken in order to meet the target. Government is required by law to implement the strategy, assess and report on the impact of its actions to implement the strategy and the progress made towards the target, and to revise the strategy if appropriate.

What the fuel poverty target for England means

The fuel poverty target has a clear focus on improving the energy efficiency of fuel poor homes.[footnote 12] While we know that other factors can affect how much it costs to keep warm, tackling the relatively low levels of energy efficiency found in England’s housing stock – especially in the homes of the fuel poor – remains a priority.

Our target seeks a high standard for 2030: Band C for as many fuel poor homes as is reasonably practicable. Achieving that outcome requires a range of actions, with a focus on the installation of energy efficiency measures. It means trying to ensure homes have sufficient insulation in walls and lofts. Some homes could see the installation of a central heating system for the first time, while others could receive heating system upgrades, or a new heat source including, for example, a heat pump being installed where appropriate.

This target is especially important in view of our commitment to Net Zero. Having a statutory target to improve fuel poor homes to this standard by 2030, and a strategy to meet this target, ensures fuel poor households will not get left behind as energy efficiency standards improve across the board.

What does ‘as many fuel poor homes as is reasonably practicable’ mean?

When considering which homes should be retrofitted based on the fuel poverty target, Government considers several factors, including the physical characteristics of the property and the preferences of the householders.

Property characteristics: It is not feasible to physically improve all homes to an energy efficiency Band C. For example, due to the building materials or style of the property, some homes are difficult to insulate fully without significantly changing their physical appearance or size. Listed buildings can face particular challenges in becoming more energy efficient in a way that is compliant with the historical character of the building. Another example is brick-faced terraced properties where external solid wall insulation significantly changes the appearance of the property unless a brick finish is applied which can be very costly. Internal solid wall insulation reduces the size of each room which is significant for smaller rooms. Internal solid wall insulation also presents bigger risks around air quality and mould.

Householder preferences: Some householders may not be interested in having their home retrofitted. It may be they are uncomfortable having strangers in their home doing works or are concerned the works will be stressful or are not right for their property. Where possible, we try to address these concerns through our policies to make it easier for householders to benefit from fuel poverty schemes.

Even though we do not anticipate being able to improve the homes of 100% of fuel poor households to Band C, many households can still achieve significant savings. For example, improving a Band G home to Band E can save the average household an estimated £1600 per year[footnote 13]. Our aim is to make energy affordable for households in fuel poverty while improving as many fuel poor homes as is reasonably practicable to Band C. Meeting the Band C target, based on the Fuel Poverty Energy Efficiency Rating (FPEER) system, is not solely based on the energy efficiency of homes, but also takes into account the impact of schemes that directly affect the cost of energy, such as the Warm Home Discount. These schemes are also important in tackling fuel poverty.

3. Interim milestones

In our 2015 fuel poverty strategy, we adopted two interim milestones:[footnote 14]

Interim Milestones:

- as many fuel poor homes as is reasonably practicable to Band E by 2020 and

- as many fuel poor homes as is reasonably practicable to Band D by 2025

This stepped approach reflects our principle of ensuring that we first support those facing the worst problems. F and G rated homes are more likely to be cold, expensive to heat and may be a health hazard. Introducing even the most well established measures to these homes for the first time – such as a central heating system – can cut fuel bills significantly and provide a major uplift in comfort. To illustrate, the average LIHC fuel poverty gap in a G rated home is £1,339, compared to £474 for an E rated home[footnote 15].

Together with partners, we have made progress towards the 2020 milestone. According to the latest statistics, by 2018 92.6% of fuel poor households were living in a property with a fuel poverty energy efficiency rating of Band E or above. This means that around 180,000 fuel poor homes remained rated F or G in 2018. We expect that the number of fuel poor homes rated F and G would be similar under both LIHC and LILEE. As we look towards the 2025 milestone, it is imperative Band F and G rated homes are not left behind, especially as future technological advances lower costs and increase technical potential. The ‘Worst First’ principle, which is discussed in Chapter 3, will need to ensure that the next generation of fuel poverty schemes contribute to improving the remaining Band F and G homes.

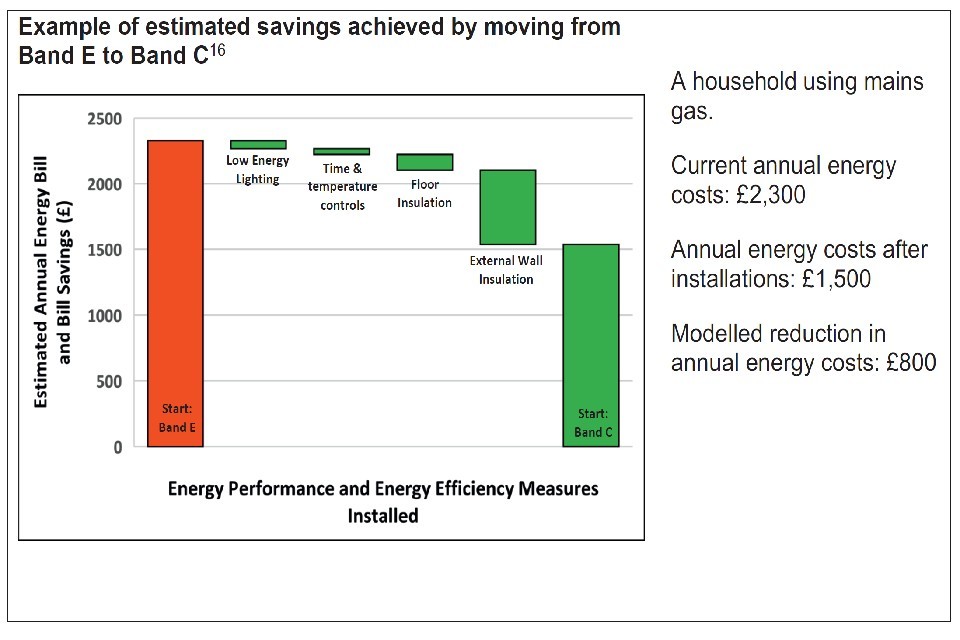

Understanding the impact of energy efficiency improvements on household energy bills

Each home is different and there is no way of stating definitively what the costs and benefits of installing energy efficiency measures will be in advance of works being undertaken. It is, however, possible to show how moving homes from lower to higher energy efficiency performance could help to cut bills.

The figure below shows an illustrative archetype of a fuel poor household, generated from the English Housing Survey. The figure shows that raising one home from Band E to Band C could lower modelled bills by as much as £800 each year.

Figure 1: Illustrative example of fuel poor homes in the English Housing Survey showing bill reduction potential

Example of estimated savings achieved by moving from Band E to Band C

This modelled example is provided for illustration only and will not necessarily reflect measures installed in future in any one home or type of home. It is important to note that the figure does not show the cost of measures or whether measures are cost effective – both of which are important factors to consider. The figure does, however, show the potential benefits to households by improving energy efficiency and lowering energy needs.

4. Our strategic approach to meeting the fuel poverty target

Vision

Our vision is to cut bills and increase comfort, health and well-being in the coldest low income homes, and to achieve the statutory fuel poverty target. This is a vision shared across Government Departments and at a local level. This vision is also shared by energy suppliers, charities, and community groups, who we are working alongside to tackle fuel poverty.

Tackling fuel poverty has a wide range of social benefits. Cold homes are recognised as a source of both physical and mental ill health. Transforming our housing stock so that homes are warm, healthy and fit for the future will help protect the health of those most vulnerable and reduce the strain on our NHS, whilst complementing the approach to more preventative healthcare[footnote 17]. This is particularly relevant given the impact coronavirus (COVID-19) can have on respiratory systems, where symptoms may make individuals more vulnerable to cold exacerbated ill-health. Further, coronavirus (COVID-19) may mean more households struggle to pay their energy bills. Retrofitting high carbon and polluting fuels with low carbon heating systems helps to improve air quality and the associated impact on health, whilst also contributing towards our climate change ambitions.

The UK was the first major economy in the world to legislate for Net Zero emissions by 2050. This will involve a radical shift in the way energy is used. Policies such as the £2 billion Green Homes Grant launched in September 2020 aim to improve the energy performance of homes and decarbonise the heating source, enabling warmer homes. Providing support for low income households to switch to low carbon heating is an important part of a just transition towards Net Zero – ensuring that the poorest in society not only are not left behind, but can be some of the earliest beneficiaries.

Principles

This strategy sets out four principles, which guide our decisions as we tackle fuel poverty in England. Although these principles can be in tension with each other, we believe that each is important to consider when making fuel poverty policy - to prioritise the least efficient homes, adopt a cost effective approach, consider how best to support vulnerable households and join up fuel poverty policies with wider Government priorities such as Net Zero.

Worst First

The way fuel poverty is measured allows us to distinguish between fuel poor households on the basis of the severity of the problem they face – known as the fuel poverty gap. Households living in severe fuel poverty, with the highest fuel poverty gaps, face the highest costs of maintaining an adequate level of warmth in the home. They also face some of the starkest trade-offs between heating the home and spending on other essentials.

There is a strong correlation between the size of the fuel poverty gap and the energy performance of the home. The ‘Worst First’ principle works as an approach to focus policies to upgrade the worst performing homes and in doing so supporting progress towards our interim milestones.

We plan to increase our focus on improving inefficient homes by multiple energy efficiency bands where appropriate. Although installing individual measures can be cost-effective, the scale of improvements to be delivered means there is real potential benefit in increasing homes directly from Bands E, F or G to Band C in one renovation. That approach, alongside the PAS2035 standard[footnote 18], also has a greater chance of maximising the benefits and minimising the risks of upgrading homes.

Cost effectiveness

Adopting a cost-effective approach means getting the best return for all investment made in tackling fuel poverty.

The cost effectiveness principle shows a long term approach to ensure policy decisions will reduce bills and improve lives over the long term. When we are designing policies which require entities other than Government to invest – for example, landlords – we should ensure the costs they face will be proportional to bill and carbon savings that could be achieved. However, both the fuel poverty and Net Zero targets mean that as a society we will need to make significant up-front investments in our housing stock.

Vulnerability

We know that some fuel poor households are more at risk from the impacts of living in a cold home than others, even if they are not necessarily the most severely fuel poor. It is right to consider the particular needs of the vulnerable – the oldest old and the youngest young, and those with a long-term health condition or disability – as we improve homes. This is on the basis of the additional negative impacts that vulnerable fuel poor households tend to face (e.g. the physical and mental health impact that can result from living in a cold home). Adopting this principle is one way in which the Government has satisfied its public sector equality duty under the Equality Act 2010.

Under the vulnerability principle, we specifically consider the needs of low income households most at risk from the impact of living in a cold home while designing fuel poverty policy. Based on the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) NG6 guidance on Excess Winter Deaths and Illness and the Health Risks Associated with Cold Homes[footnote 19], we consider low income households to be vulnerable if at least one member of the household is

- 65 or older;

- Younger than school age;

- Living with a long-term health condition which makes them more likely to spend most of their time at home, such as mobility conditions which further reduce ability to stay warm; or

- Living with a long-term health condition which puts them at higher risk of experiencing cold-related illness – for example, a health condition which affects their breathing, heart or mental health.

We will consider how to best support vulnerable households as we design fuel poverty policies. Some fuel poverty policies may specifically target or prioritise particular types of vulnerable households. We will reflect this updated view of vulnerability in the detailed tables of the annual fuel poverty statistics, so that we can track the level of vulnerable households in fuel poverty.

Commitment 1: We will continue to publish annual fuel poverty statistics, and ensure these statistics reflect our updated view of vulnerability.

Sustainability

It is important that fuel poverty policies align with other Government priorities, such as Net Zero, air quality and health inequalities. Ensuring fuel poverty policies are retrofitting homes in a way that also contributes to safety, decarbonisation and air quality goals, as well as the lowest running costs. Ensuring that homes are fit for purpose will contribute to tackling health inequalities. These can help ensure the sustainability of action.

As part of our commitment to delivering policies that deliver sustainable outcomes beyond 2030, Government will have a reduced role in supporting the installation of fossil fuel based heating. We want the next generation of fuel poverty policies to focus on upgrading homes with energy efficiency and to ramp up the deployment of low carbon heating solutions throughout the 2020s. We do not see a role for new, first time fossil fuel central heating, as a long term sustainable solution for tackling fuel poverty. We will however consider, as part of the implementation of our vulnerability principle, where supporting the repair or replacement of existing fossil fuel heating may be appropriate, particularly for those most at risk to the impact of living in a cold home over the winter months.

Commitment 2: We will ensure that future fuel poverty policies reflect the updated strategic principles for fuel poverty.

Policies and Commitments

In this strategy we have set out some of the policies which will build towards the fuel poverty target. Chapter 3 sets out a policy plan to tackle challenges and address fuel poverty over the next decade.

In order to prioritise the response to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, Government has decided to conduct a one-year Spending Review. We are facing a period of significant uncertainty. What is certain, however, is that Government remains committed to meeting the fuel poverty target. While we cannot at this point set out detailed schemes for the whole period to 2030, we have set out forward looking commitments. Commitments designed to guide future decision making and ensure we continue to make progress to overcome key challenges and address fuel poverty. We expect these to be refreshed over time through revisions to this strategy reflecting emerging priorities over the next decade.

Outcomes

The ultimate aim of Government’s fuel poverty policies is to improve the lives of any member of a low-income household who struggles to keep warm at a reasonable cost. The new Low Income Low Energy Efficiency metric will help to measure Government’s progress as we work toward the fuel poverty target. In addition to considering the impact of policies toward the fuel poverty target, Government is interested in a range of outcomes, not all of which will apply to all schemes. As with many other factors, these outcomes are likely to evolve over the period out to 2030 and the relative importance of different outcomes may also vary.

List of outcomes

- Progress against the target and interim milestones

- Lower bills

- Increased comfort

- Improved health and wellbeing

- Improved partnership

- Improved evidence base and understanding

- Improved targeting

- Lower carbon emissions

5. How Government is meeting the challenge

Improving energy efficiency standards in fuel poor homes

Improving energy efficiency is the best long term solution to tackling fuel poverty and is integral to achieving the fuel poverty target and interim milestones. We are making good progress. There are 1.2 million fewer low-income households living in the least energy efficient homes (Band E, F or G) today compared to 2010.

In this section we outline current schemes and standards designed to improve the energy efficiency of fuel poor households. We reference the Future Homes Standard, which will mean that the new homes this country needs will be fit for the future, better for the environment and affordable for consumers to heat, with low carbon heating and very high fabric standards. Whilst it is important to consider future homes, it is also crucial that we focus on existing properties with low energy efficiency bands. We outline how landlords and local authorities protect renters by ensuring that their home is not hazardously cold and meets the Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards. Finally, we summarise the schemes available to homeowners, providing funding to low income households to improve their home’s energy efficiency.

Future Homes Standard

We must ensure that the energy efficiency standards we set through the Building Regulations for new homes put us on track to meet the Government’s target of net zero emission by 2050. By improving energy efficiency and moving to cleaner sources of heat, we can reduce carbon emissions and keep energy costs for consumers down now and in the future.

From 2025, the Future Homes Standard will ensure that new homes produce at least 75% lower CO2 emissions compared to those built to current standards. In the short term this represents a considerable improvement in the energy efficiency standards for new homes. Homes built under the Future Homes Standard will be ‘zero carbon ready’, which means that in the longer term, no further retrofit work for energy efficiency will be necessary to enable them to become zero-carbon homes as the electricity grid continues to decarbonise.

We must ensure that all parts of industry are ready to meet the Future Homes Standard from 2025, which will be challenging to deliver in practice, by supporting industry to take a first step towards the new standard. In 2021 we will introduce an interim uplift in Part L standards that delivers a meaningful reduction in carbon emissions and provides a stepping stone to the Future Homes Standard. From 2021, new homes will be expected to produce 31% less CO2 emissions compared to current standards. This will deliver high-quality homes that are in line with our broader housing commitments and encourage homes that are future-proofed for the longer-term.

Housing Health and Safety Rating System

MHCLG are currently, as of 2020/21, reviewing the Housing Health and Safety Rating System (HHSRS). The HHSRS is the risk assessment tool used by local authorities to assess hazards in residential properties, including excess cold. If a hazard is identified at the most serious ‘Category 1’ level, then the local authority has a duty to take enforcement action under the Housing Act 2004. The overhaul of the system will:

- Review and update the current HHSRS Operating and Enforcement Guidance.

- Develop a comprehensive set of Worked Examples which encompass the range of hazards, illustrate the utilisation of standards and provide a spectrum of risks.

- Review the current HHSRS assessor training, the training needs of assessors and other stakeholders and establish a HHSRS competency framework.

- Identify a simpler means of banding the results of HHSRS assessments so that they are clearer to understand and better engage landlords and tenants.

- Extend current, and develop new, minimum standards that could be incorporated into the HHSRS assessment process.

- Explore the amalgamation and/or removal of some of the existing hazard profiles.

- Investigate the use of digital technology to support HHSRS assessments and improve understanding and consistency for all stakeholders.

- Review existing guidance for landlords and property-related professionals and consider the introduction of a separate guide for tenants.

BEIS and MHCLG will work together to ensure the HHSRS review takes account of the most up to date evidence on cold homes and aligns with wider Government aims on energy efficiency and fuel poverty.

Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards

The latest statistics show that 33.6% of fuel poor households in England are living in private rented accommodation. Of homes with the poorest energy efficiency standards, those rated E, F or G, 23% are in the private rented sector. It is not acceptable for landlords to let sub-standard properties that may have a negative impact on their tenants’ health and wellbeing, as well as contributing to fuel poverty. Government sees landlords as playing a significant role in investing in energy efficiency upgrades for their asset to ensure that their tenants are not living in fuel poverty.

The existing domestic Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards in the Energy Efficiency (Private Rented Property) (England and Wales) Regulations 2015 require private landlords who let out F or G rated properties to improve their properties to a minimum energy performance rating of EPC Band E, and, if they cannot source sufficient external funding, they are required to make a financial contribution of up to £3,500 including VAT. This initial focus on the poorest quality rental properties is consistent with the ‘worst first principle’ of this strategy. We are working with local authorities to share best practices for enforcement of these regulations and will be publishing a toolkit of best practices in 2021.

In autumn 2020, we launched a consultation on updates to the domestic Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards which reflect the fuel poverty target as well as Government’s ambition to improve private rented homes to EPC Band C by 2030 where affordable, practical and cost effective. Government sees that increased regulation of the private rented sector will play an important role in meeting the fuel poverty target and in making a major contribution towards wider energy efficiency and decarbonisation objectives.

Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards

Government is consulting on updating the domestic Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards for landlords in the Private Rented Sector. Our proposals include:

- Raising the minimum energy performance standard to Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) energy efficiency rating (EER) Band C;

- A phased trajectory for achieving the improvements for new tenancies from 2025 and all tenancies from 2028;

- Increasing the maximum investment amount, resulting in an average per-property spend of £4,700 under a £10,000 cap (inclusive of VAT); and

- Introducing a ‘fabric first’ approach to energy performance improvements.

Consultation concluded in January 2021.

Green Homes Grant - Voucher Scheme

In July 2020, the Chancellor announced £2 billion of support through the Green Homes Grant to save households money, cut carbon and create green jobs. He announced that the Green Homes Grant would be comprised of up to £1.5 billion of support through energy efficiency and low-carbon heating vouchers and up to £500 million of support allocated to English local authority delivery partners, through the Local Authority Delivery (LAD) scheme[footnote 20]. In November 2020, the Prime Minister’s Ten Point Plan allocated a further £320 million, extending the Voucher scheme to March 2022.

The Green Homes Grant voucher scheme has been introduced in order to support consumers in making their homes more energy efficient. This scheme, which opened in September 2020, provides low income homeowners in England up to £10,000 each to install energy efficiency and low-carbon heating measures in their homes. It will help cut carbon emissions and could see families save up to £600 a year on energy bills. The Green Homes Grant voucher scheme will additionally provide other property owners in England with up to £5,000 each, encompassing up to two thirds of the cost[footnote 21].

Green Homes Grant - Local Authority Delivery

The primary purpose of the Local Authority Delivery (LAD) scheme is to raise the energy efficiency rating of low income and low EPC rated homes (those with D, E, F or G), including those living in the worst quality off-gas grid homes - aiming to reduce fuel poverty whilst phasing out the installation of high carbon fossil fuel heating, in line with the UK’s commitment to Net Zero by 2050.

For the Green Homes Grant LAD scheme, funding is available to support the retrofit of existing domestic dwellings for all tenure types (including private landlords and social landlords). Eligible measures are any energy efficiency and heating measures compatible with the Standard Assessment Procedure (SAP) that will help improve D, E, F or G rated homes (excluding fossil fuel heating systems). Examples of measures include cavity wall insulation, loft insulation and the installation of a heat pump. Such changes will enable warmer homes and contribute to reduced energy bills for less able to pay consumers.

Local authorities may use up to 15% of grant funding to fund administrative, delivery and ancillary works to support activities such as the completion of EPC, essential repair, maintenance and preparation of properties to facilitate energy efficiency upgrades and other support as required for low income households.

Energy Company Obligation

The current Energy Company Obligation (ECO) is an obligation on larger energy suppliers to provide energy efficiency and heating measures for fuel poor households across Great Britain. Since the programme began in 2013, 2.8 million measures have been installed in over 2.1 million homes. Eligible households that benefit from measures, can save up to £300 on their energy bills, compared to an identical household[footnote 22]. Households are eligible if they either receive certain benefits, live in the least efficient social housing or if they are referred by their local authority participating under ECO Flexible Eligibility.

We intend to increase the ambition for energy efficiency and continue to prioritise low income and vulnerable households, and focus on those living in the least efficient homes to make them warmer and healthier. The next iteration of ECO will run from 2022 to 2026 with an increase in value from £640m to £1bn per year. It will be designed to align with other domestic energy efficiency policies in social housing and the private rented sector. In England, we intend for ECO to primarily focus on insulating the worst-quality homes and improving them as close to an EPC C as is cost effective and suitable for the property.

Commitment 3: We will monitor the delivery patterns of fuel poverty energy efficiency schemes, such as ECO and parts of the Green Homes Grant Voucher and LAD schemes, to identify where delivery is at lower than expected levels.

Home Upgrade Grant

In November 2020, the Prime Minister’s Ten Point Plan for a Green Industrial Revolution announced the introduction of the Home Upgrade Grant. We are committing £150 million through the Home Upgrade Grant to help some of the poorest homes become more energy efficient and cheaper to heat with low-carbon energy. The Home Upgrade Grant will support low-income households with upgrades to the worst-performing off-gas-grid homes in England. These upgrades will create warmer homes at lower cost, and will support low-income families with the switch to low-carbon heating, contributing to both fuel poverty and net zero targets. The Home Upgrade Grant is due to commence in early 2022.

Green Finance

Green finance is a key priority for the Government as set out in our Green Finance Strategy, published in July 2019, in which we launched our Green Home Finance Innovation Fund to support the development of innovative green finance products that enable homeowners to make energy efficiency improvements to their homes. Building on that strategy, government published a consultation in November 2020[footnote 23] on how mortgage lenders can help householders in England and Wales to improve the energy performance of their homes. The government is aware of the need to ensure that the proposals outlined in this consultation do not adversely affect those mortgagors who are defined as fuel poor, and to protect those who are just over the threshold of this definition from entering fuel poverty. We will be seeking views on what measures we could introduce to protect fuel poor mortgagors within the consultation.

Social Housing

15.1% of fuel poor households in England live in social housing. The majority of these fuel poor households have an energy efficiency rating of Band D, under EPC and FPEER, due in part to the positive impact of the introduction of the Decent Homes Standard. MHCLG has announced a review of the Decent Homes Standard, as part of the Social Housing White Paper 2020. The review will consider how the standard can work to better support energy efficiency and the decarbonisation of social homes.

The Summer Economic Update[footnote 24] announced a fund of £50m to demonstrate innovative approaches to retrofitting social housing at scale, accelerating delivery of the Social Housing Decarbonisation Fund. This will mean warmer and more energy efficient homes and could reduce annual energy bills by hundreds of pounds for some of the poorest households in society, as well as lowering carbon emissions. Grant recipients for the initial £50 million will be announced in February 2021. At the Spending Review 2020, The Chancellor committed to £60 million of further funding for the Social Housing Decarbonisation Fund, to continue upgrading the least efficient social housing. The Social Housing Decarbonisation Fund will upgrade a significant amount of the social housing stock that is currently below EPC C up to that standard, delivering warmer and more energy efficient homes, and reducing carbon emissions and bills, as well as creating/supporting green jobs. The Social Housing Decarbonisation Fund is intended to be open to all social housing landlords to directly access funding.

Across the schemes: Conclusion and interaction

The schemes outlined above are focused on improving the energy efficiency of consumers’ homes, with a particular focus on supporting fuel poor households. Many of these schemes and standards can work together to support individual fuel poor households in making their homes cheaper to heat and also to support local authorities in targeting and delivering support for those most in need, delivering the best quality service for their community. By focusing on energy efficiency of homes, we are seeking to deliver long lasting change and reduce fuel poverty in the long term.

To ensure vulnerable and fuel poor consumers can get the best out of the schemes, and the money can be used to install the most effective energy efficiency measures as practicable, we have considered interaction between the schemes.

It is possible for fuel poor consumers to utilise multiple schemes to increase their home’s energy efficiency. Subject to specific scheme requirements, they can be used alongside each other for the installation of distinct measures at the same property[footnote 25]. For example, a household may be funded through ECO for the installation of solid wall insulation then funded separately by LAD for the installation of a heat pump. This enables the delivery of a range of energy efficiency measures to fuel poor households.

Standards and schemes can also act together to address fuel poverty. For example, a landlord in the private rented sector[footnote 26], may use the Green Homes Grant voucher scheme to undertake energy efficiency improvements on their rental property ahead of the proposed future Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards, which aim to support fuel poor renters. For example, the landlord may use a Green Homes Grant voucher[footnote 27] to install roof insulation making the residence more energy efficient for future renters, who will have a warmer home and reduced energy bills. As well as reducing bill costs for consumers, improving the energy efficiency of fuel poor homes will contribute to reduced carbon emissions. Given the need to disincentivise high carbon output, supporting those in fuel poverty to reduce their carbon emissions will help protect them from relative increasing costs as we transition to Net Zero and ensure that they are among the first to benefit from funding in this area.

Working together to help the fuel poor through partnership and learning

Fuel poverty is a problem across society and Government cannot and should not attempt to tackle it alone. Helping those on low incomes who face the highest energy bills and live in the hardest to heat homes requires a concerted effort with contributions across Government and, very importantly, beyond Whitehall. While there are some things only Government can do, such as make law, there are other activities which can only come from our partners. These examples of effective partnerships illustrate the real progress that can be made when people and organisations work together towards a common objective.

Central Government

Across Government, Departments are working together to address the complex challenge of fuel poverty, working together so policies can complement and blend with each other and delivering better outcomes.

BEIS continues to take a leadership role on fuel poverty given responsibility for energy policy more broadly. BEIS is focused on ensuring an appropriate balance between keeping energy costs as low as possible for consumers, including the fuel poor, whilst ensuring a reliable and secure energy system which is fit for the future and in line with Net Zero commitments. Inevitably there will be costs associated with achieving this and we want to ensure that those in fuel poverty are not disproportionally impacted. We intend to ensure that impact assessments conducted by BEIS on policies affecting energy prices for domestic customers, as well as policies relating to energy use in the home, specifically consider their impact on fuel poverty.

Commitment 4: We will ensure that the design of new domestic energy schemes and policies, and reviews of existing schemes, have regard for fuel poverty.

The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) and BEIS have worked together on the use of the benefits system for targeting the Warm Home Discount and ECO schemes. More recently they have also worked together on delivering the low income element of the Green Homes Grant voucher scheme. BEIS and DWP also lead on policies that influence household income through changes to the National Minimum Wage, the benefits system and policies that support with winter energy costs such as Winter Fuel Payments and Cold Weather Payments.

The Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) and Public Health England (PHE) have responsibility for improving the nation’s health and wellbeing and to reduce health inequalities. Cold and damp homes are a significant cause of ill-health which places an additional strain on our National Health Service. We aim to embed tackling cold homes as a source of ill-health within health decision making processes to ‘Make Every Contact Count’ and ensure households living in an unhealthy home get the support they need.

MHCLG have responsibility for housing. This includes the standards for new build properties and also ensuring that housing is fit for purpose. It remains particularly important for MHCLG and BEIS to continue to work together to drive forward improved standards in the rental sector – where over half of the fuel poor population reside.

Defra’s responsibilities include improving air quality and rural issues. Around 500,000 fuel poor households live in rural areas, the specific challenges for which are discussed under ‘high cost homes’ later in this chapter. Defra and BEIS have successfully worked together on the implementation of the Rural Community Energy Fund, delivered by the Local Energy Hubs to support such communities. Defra have objectives that will seek to reduce pollutants such as particulate matter from domestic combustion whilst BEIS has objectives to phase out high carbon heating fuels. These goals can be seen as complementary, with low carbon heating a viable solution to contributing to both air quality and decarbonisation objectives.

Over time, differing priorities and shifts in emphasis may emerge. This will in turn change the nature of cross-Government working on fuel poverty, but it is inevitable that increased cross-Government collaboration is required now and will continue to be important over the next decade. These continuous changes are the reason why having a statutory fuel poverty target and a cross-Government strategy is so important: they will help ensure that Departments under successive Governments will continue to collaborate to support the fuel poor.

Local

It is often the case that strong partnerships in local government between local health, housing and energy teams can lead to bespoke partnerships which are difficult to replicate in central government.

Case Study: Plymouth Energy Community

Plymouth Energy Community (PEC) is an independent ‘not-for-profit’ Community Benefit Society established in July 2013 to help local people and organisations in Plymouth transform how they buy, use and generate power in the city. PEC was born out of a will to create a co-operative which enabled residents to access cheaper energy and generate their own energy. Its work focuses around three core energy goals: reducing energy bills and fuel poverty, improving energy efficiency and generating a green energy supply in the city.

PEC’s fuel debt service has built relationships with more than 30 organisations who now refer fuel poor customers to the scheme, including Citizens Advice and Age UK. PEC advisors have offered bespoke tariff advice to over 600 households, with average savings of £180 p.a., and cleared £35,000 of fuel bill debt in one year.

In 2018, BEIS established five Local Energy Hubs across England. The Local Energy Hubs support local authorities, community groups, businesses and residents to lead energy projects that will improve health and wellbeing while reducing costs and carbon emissions. The Local Energy Hubs are delivering against a pipeline of projects (valued at £1.3bn) identified in Local Energy Strategies and Local Industrial Strategies.

In March 2020 BEIS allocated each of the 5 Local Energy Hubs £75,000 for fuel poverty work in financial year 2020/2021. The Hubs are using this resource to employ an energy officer to support local authorities to develop their ECO Flexible Eligibility scheme and to develop bids for Local Area Delivery programmes of the Green Homes Grant.

The Green Homes Grant Local Authority Delivery (LAD) scheme, part of the wider Green Homes Grant, is intended to save households money, cut carbon, and create green jobs, levelling up communities across England. The first round of funding under the Phase 1 up to £200 million was available through a Local Authority competition which opened to applications in August 2020 (closed September 2020) for delivery by 31 March 2021. Proposals were assessed on the ‘Strategic Fit, ‘Delivery Assurance’ and ‘Value for Money’ to ensure proposals aligned to Government objectives to deliver progress towards the statutory fuel poverty target for England, phasing out of the installation of high-carbon fossil fuel heating and reducing air quality emissions, and the UK’s target for net zero by 2050. BEIS awarded funding to 55 bids totalling a value of £74 million, including consortia bids covering multiple geographically related Local Authorities, that will deliver energy efficiency upgrades to almost 11,000 low-income and low-EPC households in over 100 Local Authority regions. This funding will support a green recovery in response to the economic impacts of Covid-19 and help take low-income families out of fuel poverty. A further round of competition opened to applications, under Phase 1 of the Local Authority Delivery scheme, on 23 October 2020, with applications accepted until 4 December 2020. This phase is intended to enable projects that were successful under the first round to extend and upscale their projects over spring and summer 2021 and to enable those that did not bid, or were not successful, in the first competition to submit new proposals. Delivery will take place until 30 September 2021. A further £300 million is set aside for Phase 2 of the Local Authority Delivery scheme, which will be delivered through Local Energy Hubs in partnership with Local Authorities. More information will be available later this year and delivery is expected to begin in April 2021.

The ECO Flexible Eligibility scheme is designed to allow local authorities to identify low income households who are either living in harder to heat homes or have a vulnerable member of the household whose condition is worsened by the effects of living in a cold home. These households are some of those most in need of energy efficiency measures in the community. Local authorities have the responsibility to ensure that they have robust auditing processes in place to ensure as far as possible that only qualifying households benefit from measures under ECO Flexible Eligibility. We intend to consult on a reformed ECO Flexible Eligibility scheme under any future successor ECO schemes.

Government is working with a broad range of organisations to improve our understanding of how households are affected by fuel poverty and how we can better serve these households. It is a fundamental commitment of this updated strategy that central Government will co-operate with, listen to and support people and groups working on the frontline, tackling fuel poverty in communities across England. Government works closely with organisations like National Energy Action to develop open communication between policymakers and local practitioners working to help the fuel poor.

Government recognises that there can be no one size fits all solution to fuel poverty. We believe that truly effective and innovative approaches are most likely to emerge when partners join their efforts and expertise as highlighted throughout this strategy.

Commitment 5: We will continue to work with local partners where appropriate, giving justification for the approach during planning and design.

Commitment 6: Government will engage with, listen to and support people and groups working on the frontline, tackling fuel poverty in communities across England.

Devolution and fuel poverty

Fuel poverty is a devolved issue. Scotland and Wales have statutory targets for tackling fuel poverty and Northern Ireland is also committed to tackling the problem. Devolved administrations have their own fuel poverty strategies and policies and can direct spending at fuel poverty alleviation, subject to the existing devolution settlement.

Coordination between the four nations of the United Kingdom makes each more effective. Officials from Northern Ireland, Scotland, Wales and England have regular discussions about fuel poverty policy, learning from each other’s successes, asking for each other’s views and providing constructive challenge. We also coordinate on cross-cutting issues. For example, ECO operates across Great Britain, in the context of the single energy market. We are working closely with the Welsh and Scottish governments to monitor the impacts of coronavirus (COVID-19) on ECO and we will continue to communicate regularly and openly.

International

The UK has world-leading expertise in fuel poverty and UK academics, charities and policy officials will continue to share their experience internationally. For example, the Governments of Denmark and the UK held a joint workshop in the summer of 2020 for policymakers to better develop their understanding of energy efficiency policy.

Looking forward, we plan to not only maintain but strengthen international fuel poverty partnerships. We support the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 7: “Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all”. We are working to ensure that energy in Britain is affordable and sustainable and we provide regular updates to the United Nations on our progress. We also provide expert support to other nations as they work towards achieving affordable and sustainable energy.

Commitment 7: We will share our world class expertise on fuel poverty with international partners.

Increasing effective targeting of fuel poor households

Meeting the statutory fuel poverty target in a cost effective way requires support to be targeted at those living in fuel poverty. There is no single list of which households are fuel poor. Instead, it is essential that appropriate eligibility criteria, referral routes and targeting tools for fuel poverty schemes are developed.

Eligibility criteria

Ensuring the right eligibility criteria is important. It enables us to use our resources effectively to support those most in need. Setting of eligibility criteria can also be difficult, making decisions regarding prioritisation complicated, especially when there may be some tension between the guiding principles. This may include a tension between the vulnerability and worst first principles. For example, low income pensioners are automatically eligible for the Warm Home Discount, even if their energy bills are not particularly high, because they are recognised as a vulnerable group. We intend to consult on expanding the Warm Home Discount scheme and improving the use of data to identify low income households living with high energy costs. It is important that energy bill rebates are targeted as much as possible towards people in or at risk of fuel poverty. However, in reforming the scheme, consideration will need to be given to the impacts on low income pensioners, who may have come to rely on automatic rebates.

We would be able to achieve this improvement in targeting using data from several Government Departments, such as the Department of Work and Pensions and the Valuation Office Agency, using powers in the Digital Economy Act 2017. The automatic targeting of households with high energy costs is in line with recommendations from the Committee on Fuel Poverty and other stakeholder groups, who have called for us to use data to find the households most in need and eliminate the need for bureaucratic application processes. In the Energy White Paper, published December 2020, we reference our plan to consult on reforms to the Warm Home Discount scheme which would focus removing the first-come first-served application system for working-age households, by expanding the provision of automatic rebates through data matching.

ECO3 is fully focused on supporting low income and vulnerable households. Whilst acknowledging that many of these households are in receipt of benefits, we also recognise there are many low income households who are not in receipt of benefits. We introduced the ECO Flexible Eligibility scheme to support low income households, in particular those that may be vulnerable to the effects of living in a cold home and who are not in receipt of benefits.

For a successor scheme to ECO, we are considering how we could also target other low income households that may not be entitled to or may not be claiming benefits, but need energy efficiency improvements to their homes. We are continuing to monitor delivery of the ECO Flexible Eligibility scheme and will consider whether any changes need to be made to targeting fuel poor households under that route. Over 6.6 million households are currently eligible under the scheme. It has been designed to balance the cost of finding eligible homes with actual delivery of measures benefitting households.

We recognise that one-size-fits-all eligibility criteria may not capture everyone suffering from a cold home. That is part of the reason we established the ECO Flexible Eligibility scheme in 2017.

Case Study: Beat the Cold

The charity Beat the Cold and the Staffordshire Warmer Homes Scheme work with local authorities who volunteer to participate in the ECO Flexible Eligibility scheme.

A recipient of support from the scheme wrote:

At home it’s me now, as my husband passed away a few years ago. I have struggled for the last few years, trying to keep warm in the winter evenings with my current storage heaters, and gas fire. I usually end up going to bed early to keep warm.

I was told that there was an eligibility criteria, but that it was fair, and not just for those receiving benefits. I have my state pension, and a very small works pension, but with no savings, it would have been impossible for me to afford new gas central heating.

This has helped so much as before, my home was expensive to heat, and cold in the evenings, it is lovely to be able to sit in a warm living room watching my television. The support we have received has meant the world to me. I feel like I have got my home back.

In line with the Committee on Fuel Poverty’s recommendations, we intend to continue exploring how we could use machine learning to improve our eligibility criteria and targeting tools. However, machine learning may not be essential should we obtain and maintain more reliable datasets which accurately reflect variance across the population.

Whether we use machine learning, simpler algorithms, or data matching, we will continue to work towards better use of data in setting eligibility criteria and targeting schemes to improve outcomes for the fuel poor.

Commitment 8: We will seek to improve targeting in the next generation of national fuel poverty schemes, by building new proxies that reflect the Low Income Low Energy Efficiency indicator and looking for opportunities to extend the use of data matching wherever practical and appropriate.

Commitment 9: We will work to improve targeting by enabling and facilitating more data sharing. This includes working to remove barriers to data sharing in the health arena.

Targeting tools

Effective targeting will also mean providing supporting tools to enable more efficient and effective targeting of support to eligible households. This may be through referrals, data mapping and data matching services.

We are working with DWP to identify people with low incomes and with the Valuation Office Agency (VOA) to identify people with high energy costs, so that we can reach the people who need help the most.

We are considering the most appropriate referral routes, from mortgage lenders to healthcare professionals to charity partners, for the next generation of fuel poverty schemes. Consumers engaging with healthcare professionals, for example, might be more in need of urgent support and therefore referral routes through healthcare professionals could enable us to support more vulnerable consumers earlier, in line with the vulnerability principle. We see proactive, easy-to-access referral routes as especially important for reaching vulnerable households.

We are also considering how self-referral could play a role in fuel poverty schemes. Our aim is for self-referral to empower consumers, and therefore it is key that if self-referral is introduced, that it be as easy and inclusive as possible and not dependent on a single point of access – for example, self-referrals should not only be available online.

Optimising the data available remains key to our targeting work. By ensuring the accuracy and relevance of datasets we are better able to determine those most in need of support. We are continuing to improve the targeting tools available; for example, the Domestic Energy Map supports ECO-obligated suppliers to identify geographical clusters of homes who may be eligible for support.[footnote 28]

Case Study: Kent Energy Efficiency Partnership

In 2017, the Kent Energy Efficiency Partnership and Kent County Council worked together to build tools that more effectively target households in fuel poverty. After evaluating several datasets, the team chose to combine the Kent Integrated Dataset, which includes information from healthcare providers, with the Wellbeing Acorn dataset, which includes information about people and places.

Previously, the best maps available highlighted areas of 1600 residents. Using these datasets, the team was able to map population and health characteristics at postcode level. The postcodes highlighted as most at risk will be targeted for further fuel poverty intervention work by the Kent Energy Efficiency Partnership.

Improving the reach of support to certain high cost homes

This fuel poverty strategy covers low income households in all inefficient homes. However, certain types of homes with high running costs may face barriers to accessing support and require additional assistance. In this strategy, we aim to reduce barriers to accessing support for households living in certain home types including:

- Hard to treat homes;

- Park homes;

- Houses in Multiple Occupation (HMOs); and

- Homes off the mains gas grid.

Certain homes are technically or practically challenging to upgrade. This can mean higher upgrade costs but can also refer to the complexity of the upgrades, for example, homes with non-standard cavity walls, non-traditional construction methods or solid walls can be particularly difficult to insulate. We sometimes refer to these homes as ‘hard to treat’.

Government has been conducting research to ensure as many dwellings as possible are warm and comfortable for householders; for example, we recently concluded a research project on insulating non-standard lofts and cavity walls.[footnote 29] We are committed to pursuing innovative methods to improve the energy efficiency of hard to treat homes, including where we might reduce disruption to households during installation of energy efficiency measures.

We have awarded £7.7 million to three organisations through the Whole House Retrofit Challenge Fund[footnote 30] to explore innovative approaches to reducing the cost of whole house retrofit. This is an early step in achieving the Buildings Mission ambition to halve the cost of retrofitting existing buildings, and bring as many fuel poor homes as reasonably practicable to EPC band C by 2030. The Green Homes Grant, including the Local Authority Delivery component, can also contribute towards loft and wall insulation in technically hard to treat homes amongst other primary measures. We are also exploring how a successor scheme to ECO should support harder to treat homes. For example, by continuing to treat homes with solid walls; and considering whether support should be available for certain remedial work, such as structural repairs, which would make energy efficiency works possible. As we consult on the future of ECO, we welcome responses on how hard to treat homes should be considered.

Particular types of homes have been more challenging to upgrade for geographical, organisational, legal or social reasons.

Landlords of HMOs have not always clearly understood whether they are required to obtain Energy Performance Certificates (EPCs) for their properties and follow the Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards set out in the PRS Regulations 2015. We intend to publish new guidance for landlords of HMOs to clarify when an EPC is required and when the PRS Regulations 2015 apply to HMOs. This guidance will ensure landlords of HMOs understand their responsibility to provide a safe and energy efficient home.

Households living in a park home may not have a direct relationship with their energy supplier, making it challenging to receive rebates like the Warm Home Discount. Many suppliers now provide the rebate to otherwise eligible households living in park homes through Warm Home Discount Industry Initiatives. Such households may additionally benefit from the Green Homes Grant voucher scheme which can provide up to £10,000 for low income households in order to improve the energy efficiency of their home.

Case Study: Park Homes Warm Home Discount

The Warm Home Discount provides eligible households with a £140 rebate off their energy bills. As households living in park homes often do not hold a direct account with an electricity supplier, most households in park homes were not eligible for the Warm Home Discount.

This changed in 2015, when a new Industry Initiative made it possible for eligible households in park homes to receive the Warm Home Discount. This has provided many low income households in inefficient dwellings with the funds they need to keep warm over the winter. The majority of recipients have a household income of less than £10,000 and many are older people at risk of ill health from living in a cold home. 90% of recipients said they felt the Park Homes Warm Home Discount benefitted their health.

Since the scheme began, 17,000 rebates have been disbursed to eligible households in park homes.

Homes which are not connected to the mains gas grid often face particularly high fuel bills. The next 10 years will see a radical shift in the way homes off the gas grid are heated. Government has committed to phasing out the installation of high carbon fossil fuel heating, in new and existing homes currently off the gas grid during the 2020s, starting with new homes. In line with our new sustainability principle, we do not see a role for new fossil fuel based heating systems being installed as part of a long term sustainable solution to meeting the 2030 fuel poverty target and building towards the ultimate goal of Net Zero by 2050. We intend to limit our support for new gas heating systems, and remove support for new LPG and oil heating systems, from 2022, supporting households with new fossil fuel based heating systems under very limited circumstances.[footnote 31] This would be with a view to supporting fuel poor households to transition to low carbon heating.

In November 2020, the Prime Minister’s Ten Point Plan announced the introduction of the Home Upgrade Grant to support upgrades to the worst-performing off-gas-grid homes in England. The £150m Home Upgrade Grant scheme is due to follow the Green Homes Grant Scheme, beginning in early 2022.

Commitment 10: We will seek to ensure fuel poor households, especially those off the gas grid, are early beneficiaries of the transition to low carbon heating.

Improving the reach of support

We must consider the unique needs of different individuals and families living in fuel poverty – people who vary just as much as the buildings they live in.

Hard to reach households

Some households in fuel poverty find it particularly difficult to access existing Government support even though they are eligible. This may include households where the person or people most engaged with energy are not comfortable using a computer (or may be digitally excluded), have difficulty with reading and writing, are hearing or visually impaired or where English is not their first language. It may also be that the person or persons are facing physical or mental health conditions that affect their ability to engage with fuel poverty schemes. Others may feel stigmatised or that people would not understand their situation – for example, a household struggling with problem debt, addiction or hoarding.

It is important to consider different forms of communication and access points. Simple Energy Advice (SEA) has a website[footnote 32] which has been designed with accessibility in mind. You can navigate most of the website using speech recognition software and listen to most of the website using a screen reader. SEA further offers a freephone number which is available 7 days a week to consumers, which seeks to reduce digital exclusion.

Citizens Advice is the statutory consumer advice and advocacy organisation in the energy sector. It discharges its duties through the provision of a freephone consumer advice helpline in addition to online advice options. Citizens Advice also provides energy advice through its local offices across England and Wales to support energy consumers in vulnerable situations. The organisation helps people to resolve problems with their energy supplier and supports households in energy debt. It also helps them take actions to reduce their bills and better heat their homes, including: switching, accessing support like Warm Home Discount and the Priority Service Register, and taking measures to make their homes more energy efficient. Citizens Advice uses evidence from the people who use its services and original research to understand the problems facing energy consumers and propose solutions to industry and policymakers.

Local authorities and programmes funded by the Warm Home Discount Industry Initiatives provide high-quality support for households who may have otherwise struggled to access support. However, there is still room for us to make our schemes even more accessible for households facing barriers to support. For example, the Warm Home Discount rebate will become more accessible if it is automatically given to eligible households, rather than households needing to apply to receive it.

Commitment 11: We will consider how to make fuel poverty schemes easier to access for households facing barriers to support.

Commitment 12: We will explore how energy advice could be better provided to households facing particular barriers to support.

Low income and vulnerable to the cold

Certain low income households are particularly vulnerable to the effects of a cold home. These include households with a member who is very young, elderly or has a long-term health condition. Government is committed to considering vulnerability in fuel poverty policy design, as discussed under the Vulnerability principle.

Older people and people with certain health conditions, such as heart problems, asthma, depression or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, can see their symptoms improve or even have their life extended by living in a warmer home. BEIS, MHCLG, DHSC and PHE, will continue to work together alongside other Departments to ensure low income and vulnerable households have access to safe and warm housing.

Government remains committed to supporting healthcare professionals to follow NICE NG6 guidelines. We will learn from the implementation of Public Health England’s recently published e-learning training module for frontline healthcare workers[footnote 33] and guidance for home care workers[footnote 34]. We will consider producing additional training or guidance as needed. Some local areas are using the Better Care Fund or Disabled Facilities Grant to improve energy efficiency, to allow older or vulnerable people to live healthier lives at homes; Government will continue to share examples of good practice in promoting preventative healthcare and healthy ageing through energy efficiency.[footnote 35]

Case Study: Energy advice for patients receiving kidney dialysis

Auriga Services, E.ON and NHS Staffordshire are working together to support patients undergoing kidney dialysis with their energy bills as part of the Warm Home Discount Industry Initiatives programme.

The service is achieved through one-to-one support to renal patients on the hospital ward, in their home and over the telephone. A benefit of the scheme is that the service has been tailored to the needs of the individual. It is not a one size fits all scheme.