School Streets: how to set up and manage a scheme

Published 19 November 2024

Applies to England

Introduction

This guidance is aimed at local authorities in England, particularly authorities with limited experience of delivering School Streets. It may also be of interest to schools and elected local members. It has been developed by the Department for Transport and Active Travel England and is supported by the Department for Education and the Department of Health and Social Care.

The guidance provides an overview of what School Streets are, the key steps and factors to consider when developing and implementing schemes and how School Streets fit within the wider context of enabling walking, wheeling and cycling to school. It is not meant to be a comprehensive practical guide but provides authorities with links to sources of more detailed information and support.

Throughout the guidance references to ‘walking’ should also be read as references to kick (non-motorised) scooting and ‘wheeling’ – that is, to people making journeys by wheelchairs and mobility scooters.

Across England, around 40% of all primary school children and 25% of secondary school children are driven to school by car/van - figures that have increased dramatically since the mid 1970s. These figures vary significantly and can be influenced by factors such as school location and type of school.

Sources: National Travel Survey table NTS0615 and Travel to School factsheet.

Analysis by Transport for London found that during school term time 25% of all morning rush hour car trips in the capital relate to school drop offs, and outside London these figures may well be higher. The school run leads to congestion, noise and air pollution and road safety issues around schools and on the wider road network. Greater levels of active travel to and from school could help to address these issues, at the same time as improving the mental and physical health of pupils and their parents/carers.

By enabling the delivery of School Streets, this guidance will support progress toward the objectives set in the second Cycling and Walking Investment Strategy - in particular the objective to increase the percentage of children aged 5 to 10 that usually walk to school from 49% in 2014 to 55% in 2025.

School Streets - what and why

What is a School Street?

Throughout this guidance, we define a School Street as a road outside a school with a restriction on motorised traffic at the start and end of the school day. School Street schemes may cover part of a road, a whole road or even several roads near a school. Restrictions on motor vehicles can operate every weekday throughout the year - they are not one-off road closure events.

Motor vehicles are not permitted to enter the School Street during its hours of operation unless they have been granted an exemption within the traffic regulation order (TRO). Exemptions generally include, but are not limited to, vehicles belonging to residents, Blue Badge holders and the emergency services.

School Streets began in Bolzano, Italy in the late 1980s. They were first introduced in the UK by East Lothian Council in 2014 and by City of Edinburgh Council in 2015. In England, early examples of School Streets were delivered in Solihull and the London Borough of Camden. Many other English local authorities have now followed in their footsteps by implementing School Streets.

There are other approaches to creating School Streets, such as permanent point closures, however these fall outside the scope of this introductory guidance. Planning for new schools and school extensions should also consider from the start how the public realm around the school will enable safe active travel. This too is beyond the scope of this guidance, but further information can be found in National Model Design Code: part 2 - guidance notes (section U.3.i Schools).

Why School Streets?

School Streets can improve the experiences of a school’s pupils, staff, visitors, and neighbours alike at peak school arrival and departure times. Schemes can support the delivery of a range of benefits at the individual, school, neighbourhood and broader local authority level, including:

- removal of congestion and reduction in emissions outside schools

- reduced instances of dangerous driving, parking and turning outside schools at times of day when many children and families are present

- fewer road safety issues and improved perceptions of road safety

- increased levels of walking, wheeling and cycling to school

- enhanced opportunities for social interaction

- improved physical and mental health amongst pupils

- increased pupil independence

- developing early active travel habits which can be carried into later life

Implementing School Streets can also help local authorities to fulfil their statutory duty to promote the use of sustainable modes of travel to school as set out in the Education Act 1996 and associated statutory guidance.

A review of School Streets carried out by Edinburgh Napier University for the Road Safety Trust found that in nearly all cases where School Streets had been implemented:

- the total number of motor vehicles across School Streets and neighbouring streets reduced during the School Streets’ hours of operation

- active travel to school increased

- schemes were supported by most parents of school pupils as well as residents living on the School Street and neighbouring streets

- traffic displacement from the School Streets to neighbouring streets did not cause road safety issues of any significance

The results from Hackney’s initial trial of School Streets (as reported in its School Streets toolkit) included a 51% increase in cycling to school, a 30% increase in walking and a 74% reduction in motor vehicle tailpipe emissions.

Research for Mums for Lungs and Possible carried out by the University of Westminster’s Active Travel Academy and Transport for Quality of Life found that School Streets can reduce air pollution and traffic danger outside the school gate. The research also estimated that School Streets could be feasible at half of all schools in the cities of Bristol, Birmingham, Leeds and London.

Developing School Streets

School selection

Local authorities should develop a clear process for identifying potential sites for the introduction of a School Street and for assessing the feasibility of proposals before undertaking detailed design work.

The proposal to introduce a School Street may arise from several sources. An authority may wish to invite applications from schools, community groups or the wider public . Authorities may also identify potential sites based on their own evidence of issues with congestion, road safety and air quality around schools and with reference to their Sustainable Modes of Travel Strategy, as set out in the Department for Education’s Travel to school statutory guidance. It is important to gain support from the school’s headteacher and governing board at an early stage.

An initial feasibility assessment of proposed sites should be carried out before undertaking scheme development work to ensure that effort is not wasted on proposals that are unlikely to succeed. A simple assessment matrix can be used to score potential School Streets against key selection criteria. Where multiple proposals are under consideration, the results of these assessments can be used to help prioritise available resources and phase implementation of School Streets.

Individual authorities are best placed to determine the appropriate selection criteria for their area and any associated scoring and weighting mechanisms. However, some suggestions are given below that can be adapted to reflect local priorities. Where authorities invite applications for School Streets, it is helpful to make the criteria publicly available and to ask those proposing schemes to provide supporting information to help with the assessment.

Traffic and the highway environment

Is the school on a major road or a bus route?

Does the road have facilities that require constant essential motor vehicle access (such as a hospital)?

Are there alternative routes for through traffic?

A School Street is unlikely to be feasible where the answer is ‘yes’ to the first or second question or ‘no’ to the third. There may be exceptions to this rule of thumb where an authority implements a much broader area-wide restriction of traffic and/or is prepared to install camera-enforced bus gates to enable buses to operate on their normal route with minimal disruption.

Evidence of traffic-related problems near the school

What evidence exists to show that the site experiences problems caused by motorised traffic, how significant are these problems and could they be addressed (at least in part) by the introduction of traffic restrictions? Factors that an authority may wish to consider include the following.

Air quality

Are there high levels of pollution outside the school?

Is the school in an air quality management area?

Road safety

Does collision and casualty data indicate a problem that a School Street could help to address?

Is there any evidence to indicate a widespread perception that traffic poses a particular danger and acts as a deterrent to walking, wheeling and cycling to school?

Antisocial or nuisance parking by parents/guardians

Is this a particular problem at the site and does it have a significant impact on residents and other road users?

What other attempts have been made to address this?

Level of community support

Are the school headteacher and governing board supportive and are staff and parents able to support development and implementation?

Are local councillors/MP supportive?

Are residents and businesses willing (overall) to collaborate in the development of a workable scheme?

When assessing community support, authorities should refer to best practice advice about public opinion and consultation, such as the Local Government Association’s guide to engagement.

In general, only a small minority express strong opposition for a scheme and this tends to diminish following implementation. Authorities should not expect universal support for schemes and should not allow any one group to exercise a veto over them. Public consultation processes should be designed to gather a representative picture of views, including from the less vocal.

Active travel: commitment and potential

A School Street is more likely to deliver desired outcomes where a school demonstrates a clear commitment to encouraging active travel and where there are high levels of active travel or potential for existing car/van trips to shift to active modes. When assessing possible sites for a School Street, authorities may therefore wish to consider:

- whether the school has an up-to-date School Travel Plan

- what activities the school has undertaken to encourage and enable active travel to school and what impact these have had

- available data on the current mode share for travel to school by car/van, public transport and active modes and on the proportion of pupils living close enough to the school to walk, wheel or cycle

- school willingness to have a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with the council which sets out responsibilities for development and management of the School Street

Budget considerations

School Streets schemes can be relatively low cost, high impact interventions. However, the cost can vary significantly between schemes depending on factors such as the size and layout of the School Street, whether cameras will be used to enforce the traffic restrictions and whether complementary measures to support active travel are delivered alongside the restrictions.

The budget for any School Streets scheme will need to include provision for the following items and activities:

| Item | Description | Capital or revenue |

|---|---|---|

| Engineering/Design | Design and installation | Capital |

| Legal | Processing and advertising traffic regulation order (TRO) | Revenue |

| Consultation and publicity materials | Design, print and delivery | Revenue |

| Monitoring and evaluation | Before and after implementation | Revenue |

| Staff costs | Value of staff time spent on scheme development and implementation | Revenue |

| Enforcement | Provision and operation of CCTV cameras (if applicable) | Capital and revenue |

Hackney’s School Streets toolkit provides an example of these costs for an individual School Street with two entrances and restrictions enforced by cameras.

In addition to these generic School Street costs, the site-specific funding requirements of a particular scheme will become clearer during scheme design. For example, a particular School Street might also require investment in measures to improve accessibility such as wider footways, higher quality surfaces and the provision of dropped kerbs.

Stakeholder engagement

Engaging a diverse range of stakeholders is key to developing an effective and well-supported School Streets scheme. Efforts should be made to actively engage stakeholders throughout the development and implementation phases of a scheme. The local authority officer leading on a School Street scheme (or programme) will play an important role in this, acting as the bridge between internal local authority stakeholders and external stakeholders from a school and its wider local community.

Internal stakeholders

Within the local authority and its broader delivery chain, the officer leading on a School Street will need to establish effective working relationships with the following stakeholders (amongst others):

| Stakeholder | Role |

|---|---|

| Elected members | Provide a mandate for the programme, offer support and challenge |

| School Travel and Road Safety Officers | School engagement, promotion |

| Highways officers | Emergency and alternative route information To check for planned roadworks nearby To check for planned maintenance/resurfacing nearby |

| Traffic engineers | Design and installation |

| Traffic orders | Implement TRO |

| Public health team | Monitoring and evaluation of health outcomes, and provision of current health data |

| Environmental health team | Air quality management |

| Sustainability/climate change team | Strategic/policy support and integration |

| Urban design/landscape architect | Design and installation support |

| Tree officers | Design and installation support |

| Access and equalities officer | Advise on compliance with the authority’s Public Sector Equality Duty |

| School transport team / providers | Co-design workable arrangements for home to school transport |

| Communications Officers | Consultation and engagement support |

| Parking team including Civil Enforcement Officers | Permits, enforcement and Penalty Charge Notices |

| Gritting, refuse and cleansing teams | Agree workable arrangements, maintain and manage signs and routes |

| Local planning authority | Provide information on any pending or approved planning applications which may impact on the design and installation of the School Street |

External stakeholders

It is essential to develop a strong and ongoing relationship with schools that are selected for the delivery of a School Street and with their wider local communities including residents and businesses, local interest groups and the police. High quality external engagement can lead to more effective and well-supported School Streets schemes by:

- ensuring the scheme’s objectives and its practical implications are widely understood amongst those most impacted by it

- identifying potential problems with a scheme at an early stage and facilitating the co-development of solutions prior to implementation

- providing a clear understanding of school travel patterns and any specific barriers or challenges to increasing active travel as well as flagging up previous or ongoing initiatives that the School Street can build upon

To support external engagement, it may be helpful to establish a working group of school and local community stakeholders. Such a group should include the school headteacher, designated governor/trustee, school travel plan lead and representatives of the following stakeholder groups:

- school staff

- pupils

- parents/carers

- residents

- local businesses (if applicable)

Wider engagement with local residents can be undertaken through surveys and events. This will enable a broad range of feedback to be obtained on the scheme before and during delivery. Online platforms are a popular and efficient way to gather feedback, which can be complemented by alternative formats such as paper forms, email and telephone. Events provide an opportunity for constructive dialogue and co-design with local stakeholders and could include site visits and workshops. Face to face conversations with affected businesses may help to alleviate any concerns and gain understanding and support. Targeted and tailored communication approaches may be required to ensure that engagement is accessible to all. The Publicity section below provides further advice on communicating about the scheme with local stakeholders.

In addition to ongoing engagement, an authority will also need to conduct formal consultation on the scheme – see the section of this guidance on traffic regulation orders.

Scheme layout

Once a school has been selected for the introduction of a School Street, an authority can develop a preliminary design of the scheme layout. Schemes can cover a whole street, part of a street or even several streets immediately outside a school. There is no ‘one size fits all’ solution: the unique circumstances of each site need to be carefully considered. The aim should be to develop a scheme layout that maximises the effectiveness of a School Street in delivering its objectives whilst minimising undesirable impacts.

Key factors to consider when determining the appropriate layout for a School Street include:

- how many school entrances are in use and where they are located

- the impact of disrupting access to residential properties, businesses and other trip generators such as doctors’ surgeries

- how many residents will be exempted from the prohibition on entering the School Street during operational hours

- whether alternative routes are available for through traffic diverting around the School Street and the impact of such traffic displacement

- the displacement of school-related traffic and parking to streets on the periphery of the School Street

A small School Street zone, such as a short section of street immediately outside a school entrance, might appear to have fewer negative impacts but may also fail to increase active travel because traffic volumes remain high on most of the journey to and from school. This does not mean that more extensive School Street zones are always better. In a high-density area, if a School Street zone is too broad the number of vehicles qualifying for an exemption from restrictions may mean that traffic levels do not reduce sufficiently to give parents confidence in children walking, wheeling and cycling to school. In some cases, it may be helpful to organise an event involving a road closure to test an emerging approach, seeking feedback from the school and local community and collecting evidence to inform decisions on the preferred layout.

As it develops the scheme layout, an authority should consider the potential for introducing measures that mitigate the negative impacts of traffic restrictions. For example, some authorities have addressed the issue of parking displacement by establishing ‘park and stride’ sites within a walkable distance of the school gate.

Exemptions

Whilst traffic restrictions are the principal means by which School Streets deliver increased active travel and other objectives, all timed schemes will need to provide limited exemptions for residents’ vehicles and other essential traffic. Local authorities will need to determine what exemptions should apply to a particular School Street scheme, balancing the need for essential motor vehicle access against the reduction in a scheme’s effectiveness if levels of traffic remain high.

School Streets schemes typically provide exemptions for:

- vehicles registered to an address within the area covered by the School Street (both residents and businesses)

- emergency services vehicles and utility providers on emergency callouts

- Blue Badge holders who have reason to access the school site

- carers for vulnerable residents that require access and can provide suitable evidence

- school transport

- parents/carers of pupils with Special Educational Needs and/or Disabilities (SEND) that require a car to access school

In addition, vehicles already parked within the School Street should usually be allowed to exit. Authorities may also consider providing exemptions for other groups such as delivery drivers, tradespeople and local authority waste collection vehicles (where re-timing or re-routing has not been possible). However, exemptions are not normally provided for school staff and parents/carers (unless they are already covered by another exemption).

It is essential to give people sufficient notice of the introduction of a School Street to enable them to apply for an exemption and for applications to be processed by the authority. The application process itself will need to be clear and accessible.

Vehicles exempted from traffic restrictions will either need to display a physical permit or be granted a virtual permit (with details recorded on an authorised vehicle list). The proposed enforcement method for a School Street will influence what type of permit is used, with CCTV enforcement providing an opportunity to dispense with physical permits.

Public Sector Equality Duty

Throughout the development and implementation of School Streets, local authorities must comply with their obligations under the Public Sector Equality Duty (PSED) (Section 149 of the Equality Act 2010). The PSED requires public bodies to have due regard to the need to eliminate discrimination, advance equality of opportunity and foster good relations between different people when carrying out their activities.

Authorities should consider the impacts of a School Street scheme on the protected characteristics of age, disability, gender reassignment, marriage and civil partnership, pregnancy and maternity, race, religion or belief, sex, and sexual orientation. They should look for ways to support and reinforce positive impacts as well as mitigate any potential negatives, working with affected individuals and groups to formulate effective solutions. This should take place prior to implementing a scheme and be revisited once a scheme is operational.

Authorities should follow their own policies and processes to assess their PSED obligations. A common approach is to undertake an Equality Impact Assessment to provide documentary evidence that they have thoroughly considered the impacts of a School Street scheme and taken action to support positive impacts and avoid or mitigate any negative impacts.

Implementing School Streets

Traffic regulation orders

A School Street is created using standard vehicle access restrictions. Most School Street schemes impose restrictions on weekdays during term times and for short windows (commonly an hour) coinciding with school drop-off and pick-up times.

A traffic regulation order (TRO) will need to be made to give effect to the restriction and allow effective enforcement. There are various types of TRO.

When preparing the TRO, it may be helpful to consult the British Parking Association’s best practice guide on traffic regulation orders.

For School Streets, permanent or experimental TROs are likely to be the most appropriate. These must be made following the processes set out in the Local Authorities’ Traffic Orders (Procedure) (England and Wales) Regulations 1996.

Permanent (PTRO)

This process includes prior consultation on the proposed scheme design, a 21-day notice period for statutory consultees and others who can log objections. There can be a public inquiry in some circumstances

Experimental (ETRO)

These are used to trial schemes that may then be made permanent. Authorities must put in place monitoring arrangements and carry out ongoing consultation once the measure is built to help decide if the scheme should be made permanent. Although the initial implementation period can be quick, residents and businesses should still be given an opportunity to comment on proposed changes and the need for extra monitoring and consultation afterwards can add to costs.

Schemes installed using experimental orders are subject to a requirement for ongoing consultation for 6 months once in place, with statutory consultees including bus operators, emergency services and freight industry representatives. This consultation allows a trial scheme to be adjusted in the light of experience and feedback, which can lead to a more suitable scheme overall

Temporary (TTRO)

Temporary orders are used to put in place road closures for street works or events. They may be appropriate for short-term School Street schemes, for example to trial a design or to support events for ‘walk to school week’, but are unlikely to be suitable for a permanent, part-time restriction for School Streets.

There must be a valid, transport related reason for making a temporary order and putting the measures in place. Temporary TROs can be made for the reasons set out in section 14 of the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984:

- because works are being or are proposed to be executed on or near the road

- because of the likelihood of danger to the public, or of serious damage to the road, which is not attributable to such works

- for the purpose of enabling the duty imposed by section 89(1)(a) or (2) of the Environmental Protection Act 1990 (litter clearing and cleaning) to be discharged

Temporary TROs cannot be used to support installation of physical features such as bollards or planters, whether permanent or temporary. Temporary orders must be made following the procedures set out in the Road (Temporary Restrictions) Procedure Regulations 1992.

They can be in place for up to 18 months. There is a 7-day notice period prior to making the TRO and a 14-day notification requirement after it is made, plus publicity requirements. It is also recommended that authorities consult residents and businesses at the design stage to ensure schemes will not have unintended consequences.

Temporary orders must be made following the procedures set out in the Road Traffic (Temporary Restrictions) Procedure Regulations 1992.

Special event TROs

These are orders made under section 16A of the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984. They enable a road to be closed for a maximum of 3 days to enable a ‘sporting event, social event or entertainment’.

School Streets are unlikely to fall within a definition of ‘social event or entertainment’. In addition, the Secretary of State’s approval is needed for any special event orders for closures or restrictions lasting more than 3 days or if it will affect the same road on more than one occasion in a calendar year. For these reasons, special event orders are not suitable for permanent School Street schemes but may be useful to support one-off events outside schools.

Traffic signs

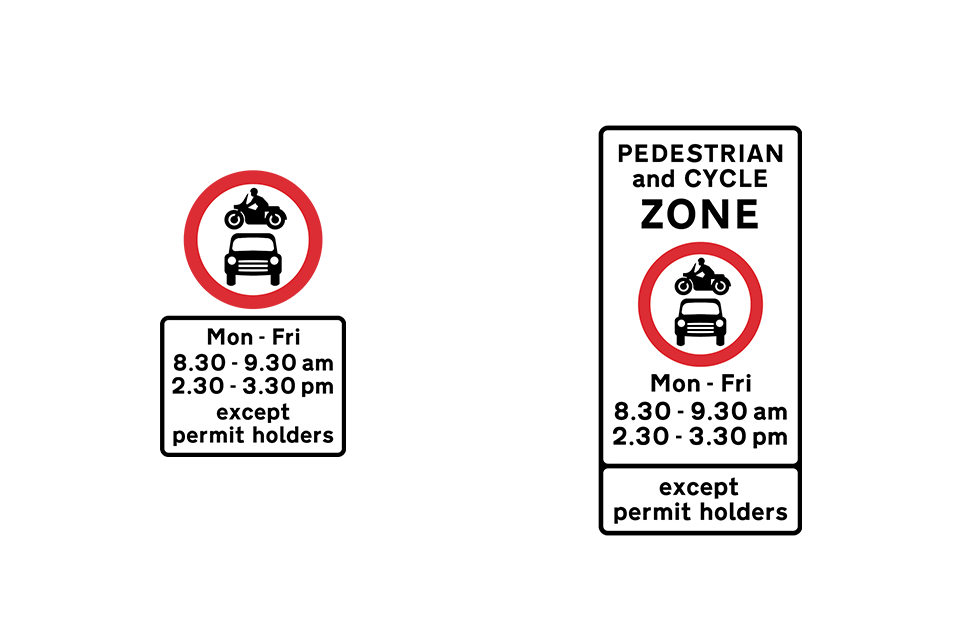

All traffic signs used in conjunction with School Streets must be as prescribed by the Traffic Signs Regulations and General Directions or as specially authorised by the Department for Transport. School Streets are signed using the prescribed ‘no motor vehicles’ (diagram 619) or ‘pedestrian and cycle zone’ (diagram 618.3C) traffic signs as shown in figure 1.

Figure 1: ‘No motor vehicles’ and ‘Pedestrian and cycle zone ends’ traffic signs

Where a ‘pedestrian and cycle zone’ sign is used at the entrance to the School Street, installing a ‘pedestrian and cycle zone ends’ sign (diagram 618.4B as shown in figure 2) at the end of the zone can be helpful to road users.

Figure 2: ‘Pedestrian and cycle zone ends’ traffic sign

As School Streets usually operate only in term-time, flap-type signs are recommended that can be folded to show a blank face during school holidays. Arrangements will need to be made for carrying this out, including access and keyholding.

General advice on sign design and placement is given in Chapter 3 of the Traffic Signs Manual. There are no specific requirements for pedestrian and cycle zone signs used for School Streets, but the general requirement to ensure drivers can see signs in time to be aware of an upcoming restriction and act on it should be borne in mind. Local publicity in advance of the scheme going live will help drivers familiarise themselves with the new restriction.

Enforcement

Enforcement of School Street restrictions can be carried out by local authorities where they have taken on the powers to do so. In London, this is through the London Local Authorities and Transport for London Act 2003. Outside London, this is through regulations made under Part 6 of the Traffic Management Act 2004. Information on applying for Part 6 powers is available in the statutory guidance for local authorities outside London on civil enforcement of bus lane and moving traffic contraventions.

Both regimes allow local authorities to issue penalty charge notices (PCNs) to any non-exempt motor vehicles entering the School Street during its hours of operation.

The police retain powers to issue fixed penalty notices for contraventions of School Street restrictions even if the local authority has taken on the Part 6 powers. If the police and the local authority initiate enforcement for the same contravention, police action would take precedence.

For the purposes of police enforcement, the underlying offence for a School Street restriction is ‘contravening a traffic regulation order’ which is an offence under section 5 of the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984. This is listed in Schedule 3 of the Road Traffic Offenders Act 1988 as an offence for which the police may issue a fixed penalty notice.

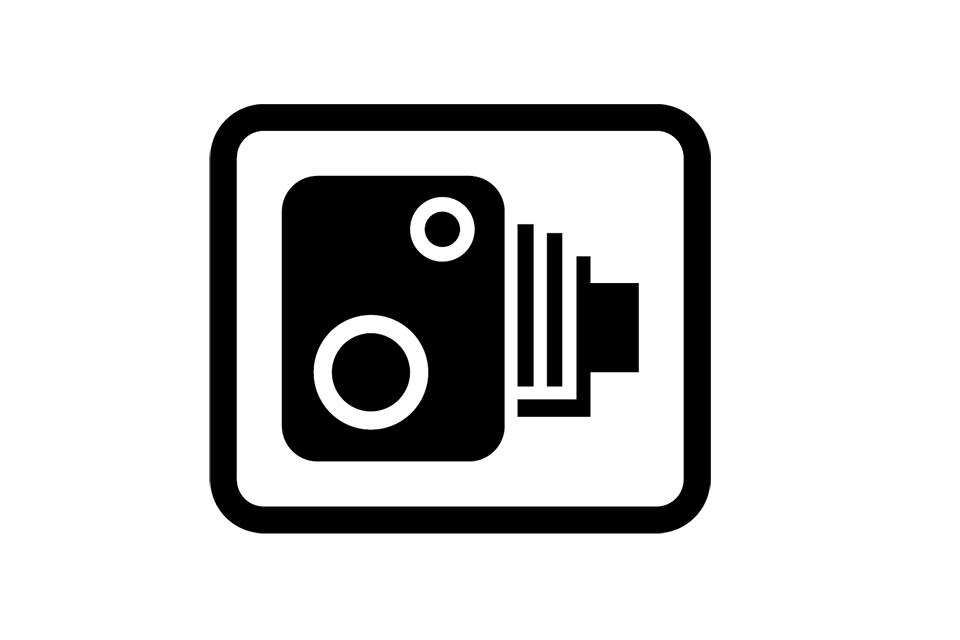

CCTV cameras can be used to enforce School Streets by issuing PCNs remotely to registered keepers of non-exempt motor vehicles. Cameras can be fixed or in a mobile unit. Mobile cameras can be a more cost-effective option, as they can be moved between sites, allowing spot checks across multiple School Streets and other locations. If CCTV enforcement is used, authorities should consider alerting drivers to this by installing the advisory sign prescribed by the Traffic Signs Regulations and General Directions for areas in which enforcement cameras are in use (diagram 878 as shown in figure 3).

Figure 3: ‘Enforcement camera’ traffic sign

In line with the statutory guidance on enforcing moving traffic offences, authorities should issue warning notices for first-time contraventions for a period of 6 months following implementation of enforcement of moving traffic contraventions.

Where the local authority has not taken on enforcement powers, the enforcement of School Street restrictions remains a police responsibility. Given the competing pressures on police resources, it is important to engage with the police at an early stage in the development of plans for a School Street to understand what support and enforcement they will be able to provide.

Use of barriers

Some School Streets have been implemented using portable barriers and volunteer stewards. This approach needs careful thought and is unlikely to be an appropriate solution for a permanent scheme.

Maintaining a stewarded and barriered School Street has significant resource implications, which may risk the long-term viability of a scheme. Some authorities are moving away from this approach as ‘volunteer fatigue’ results in fewer willing stewards coming forward over time. Volunteer harassment has unfortunately been a problem in some areas as well, which may also contribute to a reluctance to get involved. Volunteer stewards do not have the legal power to stop traffic but must rely on the signs and barriers.

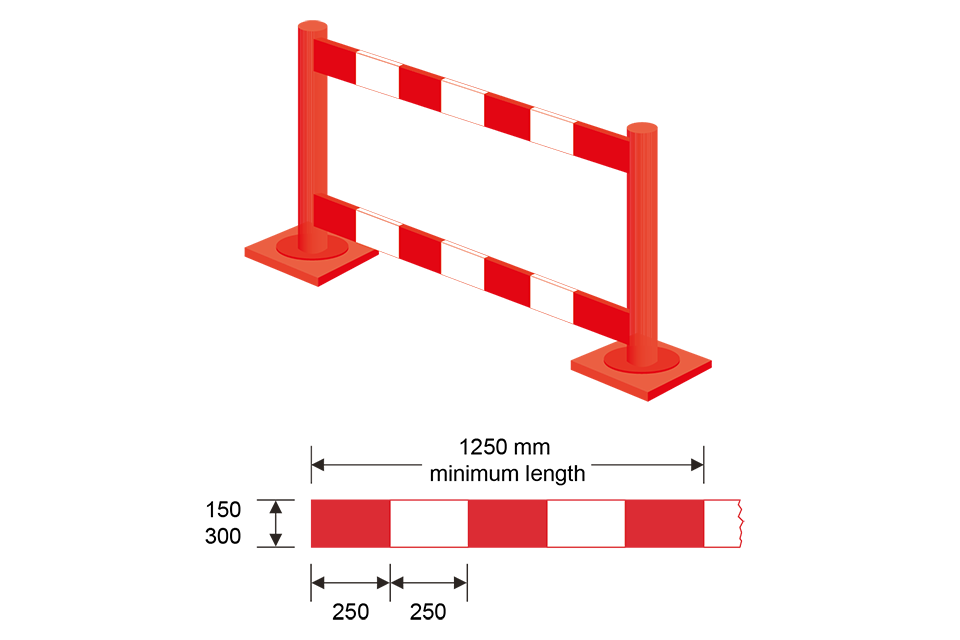

A physical barrier creates a road closure, which is different to an access restriction. Barriers cannot be used to give effect to a TRO for ‘no motor vehicle’ access restrictions, as these are different and must be signed as shown in figure 1.

‘No motor vehicle’ signing should not be used in conjunction with barriers instead of ‘road closed’ signs, as this creates a conflict between the vehicle access restriction and the road closure which will make enforcement difficult.

A road closure requires a TRO, in the same way an access restriction does. Closures are usually put in place for road works or special events with temporary TROs. A temporary TRO can only be made for specific reasons and is unlikely to be suitable for a permanent, part-time restriction for School Streets – see the section of this guidance on traffic regulation orders.

Exceptions from a closure cannot be provided as comprehensively as with an access restriction; as well as the physical barrier making it harder for permit holders to access the road, there is no equivalent of the plate showing ‘except permit holders’ or similar. Requiring volunteers to open the barrier to allow permit holders through is not appropriate as it puts an onus on them to determine if the driver is a genuine permit holder and opens them up to possible harassment and abuse, and potential road safety risks.

Road closure signs and barriers are not enforceable by local authorities as they are not included within Part 6 of the Traffic Management Act 2004, nor the London Local Authorities and Transport for London Act 2003, meaning engagement with the police will be needed at an early stage of scheme development.

If used, barriers must incorporate the sign shown below and prescribed in the Traffic Signs Regulations and General Directions.

Figure 4: Barrier to mark length of road closed to traffic or to guide traffic past an obstruction

Barrier designs used for roadworks and other temporary situations will incorporate this. White-on-red temporary signs should also be provided as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5: ‘Road closed except cycles’ sign

Barriers and stewards may be effective for a short-term trial or events such as Walk to School Week but signed access restrictions and camera enforcement are more likely to be successful for permanent schemes.

Safety and Training

Prior to implementing a School Street, authorities should conduct a site-specific assessment of the road safety risks to all users under the proposed arrangements and put in place appropriate mitigation measures. For example, lower levels of motorised traffic could lead some children and their parents/carers to become less vigilant when using a School Street and interventions (such as road safety education sessions to pupils, staff and parents and carers) should be put in place prior to commencement ensure users remain aware that exempt motor vehicles will still be allowed to use the road. Authorities should follow their own established risk policies and processes when developing risk management plans for School Streets. These plans are most likely to be effective when developed in close collaboration with the school’s leadership team.

You may decide to have stewards to help run your School Street, especially for a period immediately following implementation. These people do not have legal powers to stop traffic and should be well briefed and trained on how to safely undertake their role. There is no requirement for stewards to undertake specific training on delivering School Streets but authorities should consider providing such training opportunities.

Active travel organisations can provide useful information and advice.

Issues such as insurance, and appropriate PPE should be part of local authority risk policies and processes.

Security

The introduction of a School Street can alter the security risk profile of a location. This includes risks related to terrorism.

The reduction of motor vehicle traffic can create a perception of greater safety and security. It is therefore important that local authorities identify and adopt proportionate response procedures and protection measures.

We strongly recommend that authorities implementing a School Street scheme consider and implement simple response procedures and plans to help mitigate the impact of any incident. In the unlikely event that one should occur, such measures will help keep people safe within the confines of the scheme.

Guidance can be found on the ProtectUK and the NPSA websites including:

- ProtectUK Venues and Public Spaces guidance

- Recognising Terrorist Threats

- Hostile Vehicle Mitigation

- Working with Counter Terrorism Security Advisors (CTSAs)

Implementation of a School Street scheme could require some changes to road layout and street furniture. Speaking to a CTSA early in the design phase could help you include mitigation opportunities to prevent the possibility of someone using a vehicle as a weapon, with little or no extra expense.

In addition, developing and sharing easily understood response plans to ensure staff and parents can be quickly alerted, know what to do and where to go in the event of a security incident within the School Street scheme footprint will empower those in a position of responsibility to be prepared to respond and reduce any impact on the safety of the children. This could be included within the school’s overall security and response plan, which can be developed following the DfE Protective security and preparedness for education settings guidance.

Publicity

Direct, tailored, advance communication with all residents and businesses within and just outside the School Street is important so that they know what to expect and how the scheme will impact them. Authorities should consider providing materials in different formats and languages that reflect the make-up of the local community.

It is also important to communicate with people who may be driving through the area. This can be done using a range of materials such as school gate banners and lamp post wraps as well as making use of various communications channels including social media and local news outlets. Developing a School Streets logo and a distinctive brand will help to build recognition and understanding. Any promotional material placed on or near streets should not include or resemble traffic signing.

Hackney’s School Streets toolkit provides a range of publicity materials that can be freely adapted for other authorities’ School Street schemes.

Launch

Authorities and schools may wish to hold a street party or games morning in a School Street’s first week of operation to start it off in a positive and celebratory way. This will require closing the road to motor traffic so the appropriate TRO (such as a temporary TRO for special events), barriers and traffic signs will need to be in place. Marshals or stewards should be present as well. Access will need to be maintained for emergency services vehicles and Blue Badge holders.

It is also worth considering opportunities to co-ordinate the timing of a School Street launch with relevant community events or national observance weeks such as Cycle to School Week, Walk to School Week or Road Safety Week.

Post-launch responsibilities

It is essential for the authority and school to agree clear roles and responsibilities for the ongoing operation of a School Street scheme, which will vary depending on how the scheme is implemented. Several authorities have found it helpful to develop a Memorandum of Understanding with a school, setting out responsibilities for:

- promoting the School Street scheme

- delivering complementary interventions to support sustainable school travel

- managing the permit regime for exempted vehicles

- maintaining signs and providing marshals (where applicable)

- monitoring and evaluating the impacts of the scheme

- reviewing and amending the scheme

Monitoring and evaluation

It is essential to monitor and evaluate School Street schemes to determine whether they are working as intended. Arrangements for monitoring and evaluation need to be considered at an early stage of scheme development to inform the collection of baseline data prior to introducing the scheme.

To provide clear evidence of the impact of the School Street scheme, care should be taken to minimise variations in the pre- and post-implementation monitoring regime by controlling as many variables as possible. This includes, for example, using the same data collection methods and collecting data at similar times of day and seasons of the year.

The objectives of the scheme determine what monitoring data should be collected. For School Streets, monitoring is likely to focus on measuring changes to:

Levels of walking, wheeling and cycling to school. This data can be obtained through a simple mode of travel survey which a school may already collect. If not, a ‘hands up’ survey of pupils (and potentially staff too) can be carried out to ask about the usual mode of travel to school. If postcode data is obtained as well, it is possible to identify the degree to which pupils living within walking or cycling distance are still being driven to school and also to include other geolocated data in evaluation.

Traffic volume, type and speed within the area covered by the School Street and on surrounding streets. Automatic traffic counters and/or video surveys are both useful methods of capturing this data. Monitoring traffic on streets surrounding the School Street zone is important for understanding the impact of any traffic or parking displacement, especially where residents have raised concerns about such impacts.

Air quality in the vicinity of the school. The Local Air Quality Management process requires local authorities to regularly review and assess air quality in their areas. The time-limited and small-scale nature of School Streets schemes can make it difficult to identify the precise impact of a scheme on air quality but general trends can be discerned, particularly where data is collected over a period of time before and after introduction of a School Street.

Other sources of information to help evaluate the impact of a School Street (as well as to inform potential changes to the scheme) include:

- interviews and questionnaires with stakeholders, including pupils and teachers - these can provide insight into how a scheme has affected travel habits and parental perceptions of road safety as well as being used to find out whether people want the scheme to be made permanent

- analysis of driver compliance with traffic restrictions and whether any patterns emerge from this data

- analysis of comments received on the scheme

- analysis of other data to assess wider impacts, such as childhood obesity, physical activity and mental health

- photographs – before and after pictures can be incredibly powerful in showing the impact of a School Street

Once an authority has analysed the monitoring data, it should share the key findings with stakeholders, local networks and the media.

School Streets as part of a coordinated approach to school travel

Are School Streets right for this school?

Whilst this is a guide to implementing School Streets, it is important to emphasise that School Streets may not be suitable for every school. The section on School Selection provides advice on the factors to consider when deciding whether a School Street is a suitable intervention for a particular school.

School Streets are also not the only intervention - or even the first-line intervention - that local authorities and schools can deliver to enable safer and more sustainable school travel. Some examples of other interventions are provided below under three headings: education, training and awareness; encouraging participation; and engineering measures. Depending upon the circumstances, these interventions might be delivered prior to, alongside or as an alternative to a School Street scheme. It is important that any evaluation takes account of any additional interventions taking place alongside the School Street itself.

School travel plans

Prior to considering the introduction of a School Street at a school, local authorities should normally expect a school travel plan (STP) to be in place and for the school to have delivered various initiatives to support sustainable travel to school. This approach ensures that schools at the heart of a School Street scheme are clearly committed to sustainable school travel and opportunities have been taken to make alternatives to driving to school truly viable (thus increasing the likelihood of the School Street scheme being successful).

An STP is a written document that contains evidence about travel patterns at a school and identifies a series of actions to enable safer and more sustainable travel. The production of a STP is led by schools themselves and good plans will be developed with the involvement of the whole school community. STPs should be reviewed and updated on a regular basis, supported by evidence of changes in pupils’ travel habits and the impact of initiatives delivered to date.

The Modeshift STARS education platform supports schools with the development of STPs and provides them with the opportunity to gain accreditations and awards for their efforts. This is available free of charge for schools in England outside of London. Similar support is provided to schools in London through TfL Travel for Life.

Education, training and awareness

Initiatives that aim to provide pupils and their parents/carers with the information, skills and confidence they need travel actively include:

- identifying and mapping safe active travel routes to school

- producing walking, wheeling and cycling zone maps (these depict the area within a 5-10 minute walk, wheel or cycle of the school gate and address the common tendency to overestimate walking times and distances)

- teaching pupils about the health and environmental benefits of sustainable travel

- providing pedestrian skills training for younger pupils

- giving pupils with Special Educational Needs or disabilities access to Independent Travel Training

- providing Bikeability cycle training and embedding this within learning activities using Bikeability Tools for Schools

- introducing balancing, scooting and cycling games and activities as part of PE, breaktimes and other school activity

Encouraging participation

Ways to get the school community interested in and excited about active travel, and ultimately choosing to walk, wheel or cycle to school, include:

- taking part in organised challenge events such as Living Streets’ Walk to School Week and Sustrans’ Big Walk and Wheel

- establishing school clubs for scooting and cycling

- running a reward scheme for pupils that walk, wheel and cycle to school such as Living Streets’ WOW walk to school challenge

- setting up a walking bus and/or bike bus

Consideration should also be given to including pupils that live further away from school and are reliant on a car or public transport as the main mode for their journey. Pupils using public transport can be encouraged to get off at an earlier stop and to walk or wheel the remainder of their journey. Similarly, some pupils who are reliant on a car might be encouraged to ‘park and stride’, parking away from the school and walk or wheel the remainder of the journey. In some areas, it may be possible to set up an official Park and Stride point a walkable distance from school by gaining permission, for instance, from a local supermarket or village hall to use their car park for this purpose.

Engineering measures

Physical improvements can be made to routes to school to make them safer and to ensure that they are fully accessible. Interventions could include improving the surface quality and width of footways, installing dropped kerbs, providing additional safe crossing points and introducing various traffic calming measures including lower speed limits.

Mapping postcodes of pupils, mapping routes to school and conducting ‘street audits’ of common routes can help to identify barriers to active travel and prioritise improvements. It is important to involve pupils in these audits and local authorities and active travel organisations can often provide guidance and support to schools.

In addition to physical improvements to the surrounding highway, consideration should be given to improving facilities on the school site. Providing sufficient levels of cycle parking and secure storage for scooters and buggies will ensure that pupils and parents/carers are not deterred from walking, wheeling and cycling by a lack of facilities at their destination.

Further information and support

| Organisation | What they do |

|---|---|

| Active Travel England | Government’s executive agency responsible for active travel |

| Bikeability Trust | Manage national cycle training programme |

| Department for Transport | DfT has published a number of toolkits for local authorities, including active travel |

| Department for Education | Travel to school statutory guidance |

| Hackney Council | Detailed School Streets guidance and resources |

| Living Streets | Walking and active travel to school programmes, resources and School Streets advice and support |

| Modeshift | Modeshift STARS online school travel plan toolkit and rewards and active travel membership network |

| ROSPA | Guidance on School Site Road Safety |

| School Streets Initiative | An independent website with links to a range of information and advice |

| Sustrans | Sustrans make it easier for people to walk and cycle. They can organise, deliver and provide built environment design for a school street scheme. |

| TfL Travel for Life | Transport for London programme supporting schools to create travel plans and deliver activities to enable safe and healthy travel to school. |

Myths about School Streets

School Streets can become the subject of unfounded myths if efforts are not made to explain to stakeholders how a scheme will operate, particularly how undesirable impacts will be reduced or avoided entirely.

Some common myths about School Streets are set out below. Authorities should address these issues with stakeholders early on to prevent any misconceptions from gaining widespread credibility and affecting levels of support for a scheme.

Myth 1 - School Streets delay the response of emergency services

Reality

Emergency service vehicles should be exempt from School Street restrictions, so they can access locations within a School Street zone and use roads in the zone to travel to emergencies at other locations.

Myth 2 - School Streets disadvantage Blue Badge holders

Reality

Blue Badge holders who require access to a School Street zone during operational hours can be exempted from the restrictions. Local authorities can put in place permit schemes that exempt vehicles, including those used by Blue Badge holders, from traffic restrictions.

Myth 3 - School Streets prevent teachers and other school staff from getting to their place of work

Reality

Traffic restrictions are in force for short periods that coincide with pupil drop off and pick up times. In many cases, teachers/other school staff who rely on a car will arrive before the restrictions come into force and will not be negatively affected by the scheme. Vehicles already parked within a School Street before the restrictions apply can remain parked (subject to any parking restrictions) and usually are able to leave at any time.

Myth 4 - It is impossible to make deliveries to addresses inside a School Street zone

Reality

School Street schemes restrict motorised traffic for limited periods of time: most operate for 2 hours (or less) in a 24-hour period and during term-time only (just over 50% of days in a calendar year). As a result, only a proportion of all deliveries will be affected and it may be possible to retime some of these so that they are made outside a scheme’s hours of operation. For deliveries that cannot be retimed, authorities can minimise the impact of a School Street by keeping the zone small so that delivery drivers can park nearby and walk goods a short distance to their destination. If this is not feasible, authorities can also consider applications for a permit exempting a delivery vehicle from the restrictions.

Myth 5 - School Streets are only suitable for high density areas where pupils live within walking distance of the school

Reality

School Street schemes can also work for lower density areas and schools with larger catchment areas, if complementary measures are delivered to support cycling and multi-modal journeys that combine public transport or car/van trips with walking, for example, by introducing measures such as Park and Stride sites.

Myth 6 - School Streets force people to stop driving which is discriminatory to parents who need to drive

Reality

Authorities can minimise the impact of a School Street by keeping the zone small so that the impact on parents that must drive is likely to be a slightly longer walk to the school gates. Authorities may wish to introduce complimentary measures such as park and stride sites, or operate an exemption policy for parents that must drive due to, for example, a disability.