Intra-company Transfer report: October 2021 (accessible version)

Updated 20 April 2022

Executive Summary

Background to the commission

On 28 September 2020 the Home Secretary commissioned[footnote 1] the Migration Advisory Committee (MAC) “…to undertake a study of the Intra-Company Transfer (ICT) immigration route …”

The MAC was “…asked to have regard to the commitments that the UK has taken in respect of intra-company transferees in the Mode 4 provisions of free trade agreements, and the need to ensure that those commitments are fully implemented under our domestic rules.”

In addition the MAC was also asked to help the Home Office in the design of “…its mobility offer to enable overseas businesses to send teams of workers to establish a branch/subsidiary (currently we can only admit a single worker for this purpose) or to undertake a secondment in relation to a high-value contract for goods or services.” and to provide “…advice on where we should set any criteria on the eligibility of workers (e.g. skill and salary thresholds) and the sending organisations (e.g. size of company, value of investment or contract, potential job creation etc.).”

The MAC was asked to report by October 2021.

The ICT immigration route

The UK is a member of the World Trade Organisation’s (WTO) General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS): Chapter 1 has more details. As part of the GATS, the UK allows entry, and temporary stay, of people for business purposes. This includes Intra Company Transfers (ICT), an immigration route which enables international businesses to deploy key employees, where they are senior managers or specialists, to their UK branch or head office. Deployment is permitted on a temporary basis when there is a specific business need to do so. The ICT route is open to established employees who have worked for their overseas branch for at least 12 months (with some exceptions).

The UK has committed to not apply an economic needs test, such as the Resident Labour Market Test (RLMT), to the ICT route and it would be in breach of its international obligations if it were to introduce one, or to place a limit on the length of stay of ICTs below 3 years (GATS), or below commitments made in specific Free Trade Agreements (FTAs). In addition to the GATS, the UK has also made commitments on Graduate ICTs in some of its FTAs and will need to uphold these.

Although the ICT route was designed for intra-corporate mobility of key personnel, in practice there is some overlap between the ICT route and the main Skilled Worker (SW) route, and in certain circumstances employers with overseas offices may consider both as ways of filling vacancies in the UK.

Some of the key advantages that the ICT route offered in comparison to the old Tier 2 (General) (T2(G)) route that existed before December 2020 are no longer present under the SW route which began in December 2020 and included EU nationals from January 2021. The main remaining advantages of using the ICT route are:

- The lack of English language test requirement;

- The inclusion of some allowances, particularly housing costs, when assessing whether a worker meets the salary threshold;

- The multiple-entry aspect of the visa allows more flexibility for time spent in the UK over the duration of the visa; and

- The requirement for workers to only meet the salary threshold for the route when working in the UK (rather than throughout the validity period of the visa).

The costs of a visa under the SW route and ICT are commensurate. Whilst not applying the Immigration Skills Charge (ISC) to the ICT route was previously considered by the MAC, it was ultimately decided that ICT workers could displace UK workers and as such the ISC should apply, with the exception of the Graduate Trainee route. As part of the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement (the UK’s free trade agreement with the EU), the UK has committed to exempt EU ICT workers from the ISC from no later than 1 January 2023.

Given the current relatively limited advantages of the ICT route over and above the SW route we would, therefore, expect to see displacement from the ICT route into the SW route, which has both lower skills and salary requirements than ICTs.

Evidence gathering and research to support this ICT review

As with other commissions, we carried out a programme of stakeholder engagement and launched a Call for Evidence (CfE) to inform our response. In addition, we commissioned qualitative research to provide further information on how the ICT route works for both employers and employees who use the route (further details are in Chapter 2) and undertook data analysis using a range of sources.

The CfE asked employers, representative organisations, government departments and others structured questions about the ICT route. This was done using online questionnaires, where the primary focus was on obtaining deeper information through using open questions; the full questions are listed in the Annex document.

The CfE was launched on 23 March 2021 and was open (including a 1-week extension) for a total period of 13 weeks, closing on 22 June 2021. We received a smaller number of responses to this consultation than to some others, owing to the relatively niche nature of the ICT route (a small number of large users of the route), and the continuing disruption to businesses caused by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. In the 13 weeks the CfE was open 68 respondents submitted answers to the questionnaires, and 11 organisations submitted further evidence: either as part of their CfE response, or directly to the MAC secretariat.

In addition, we engaged directly with a wide range of stakeholders from throughout the United Kingdom, at a series of virtual events. These events included engagement with employers who use the immigration system (including the 4 largest users of the ICT route by numbers of Certificates of Sponsorship (CoS) used), embassies and consulates (to learn from international experience) and Devolved Administrations and their key stakeholders. We are grateful to everyone who participated in these events, who hosted events for us, and who completed the CfE.

We also commissioned qualitative research with users of the ICT route. This was carried out by an independent research contractor, Revealing Reality, on behalf of the MAC. Interviews were carried out with 15 employees and 15 employers who had used the ICT route. Fieldwork took place between 25 June and 10 September 2021. The full report will be published separately by the MAC shortly, and we have used the findings[footnote 2] from this work to help inform our decision making.

We also undertook analysis of relevant datasets to examine a range of issues such as numbers and types of migrants using ICTs and salary distributions. These have been a combination of Home Office administrative data, such as the CoS data, and large-scale national surveys primarily collected by the Office for National Statistics (ONS), such as the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE). These findings, coupled with relevant economic literature, and the other sources detailed above, have enabled us to set out a series of recommendations.

As part of the analytical work we undertook (quantitative analysis of available CoS data, and qualitative analysis of CfE responses and written submissions), we looked at whether there were any differences by any of the protected characteristics as defined by the Equality Act 2010[footnote 3]. It was not possible to collect data on all protected characteristics, and we have recommended that the Home Office collects further data as part of visa applications.

Key findings and recommendations for ICTs

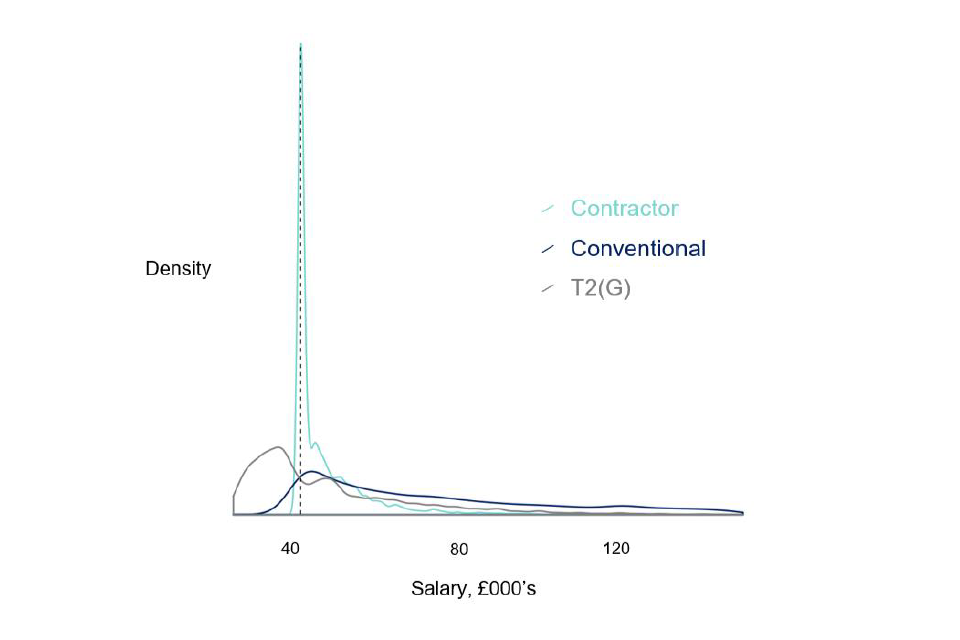

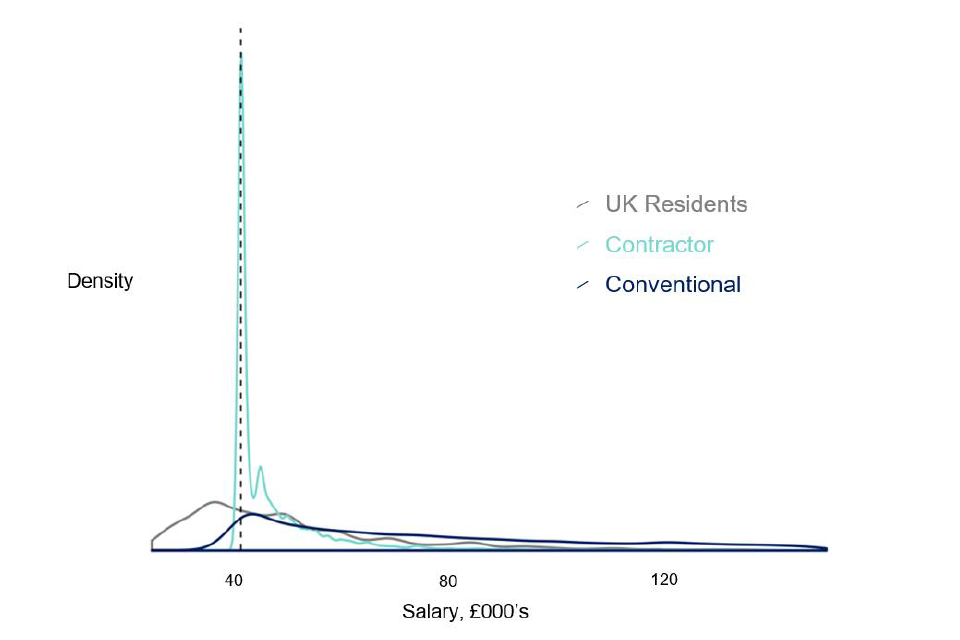

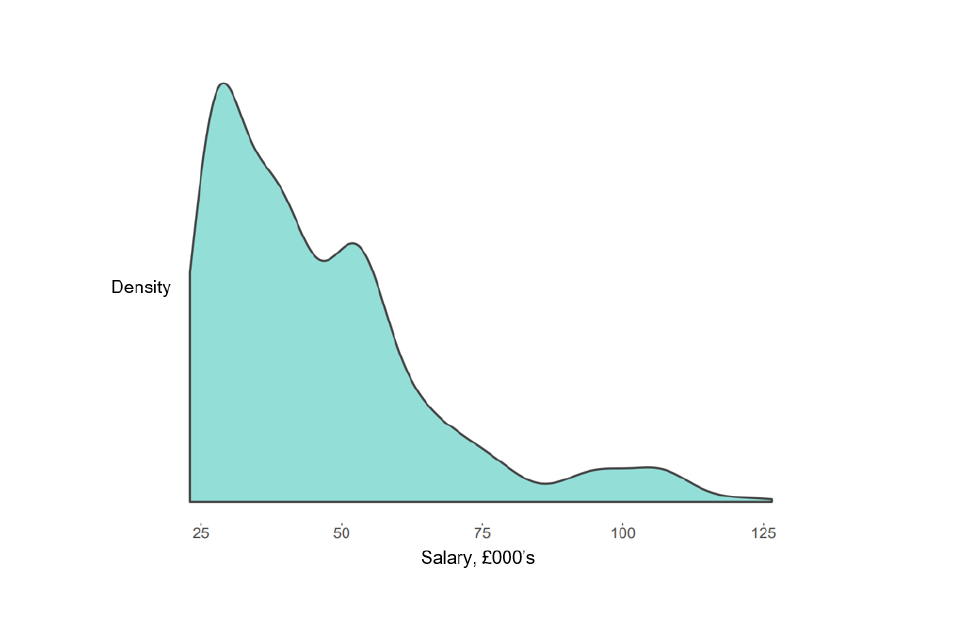

There are 2 distinct uses of the ICT route, which we will refer to as the conventional route and contractor route. The conventional route allows employees to work for the sponsor organisation within the UK, whilst the contractor route allows employees to carry out work for a third-party organisation whilst still being employed by the sponsor.

The contractor route is the larger of these (63% of ICT visas in 2019). Although it is not a distinct route for the Information Technology (IT) sector, the route is dominated by IT firms, with the sector making up 81% of overall ICT contractor usage in 2019.

Indian nationals account for 97% of ICT contractor visas (Chapter 3 has more details), this is much larger than their equivalent share for the conventional route (35%).

Use of the contractor route is dominated by a relatively small number of large sponsors, with the top 4 firms accounting for 53% of contractor visas, and the top 10 for 78%, compared to the conventional route where the equivalent figure is just 20% for the top 10 firms.

The ICT route is skewed towards males, who make up a much larger percentage of overall ICT usage for both contractor (84%) and conventional (68%) routes, in comparison to the T2 (G) route (56%).

The MAC’s analysis, as set out in detail in Chapter 3, does not suggest ICT migrants are having an adverse impact on wages or employment amongst domestic workers, even in those occupations where use of ICTs is more prominent.

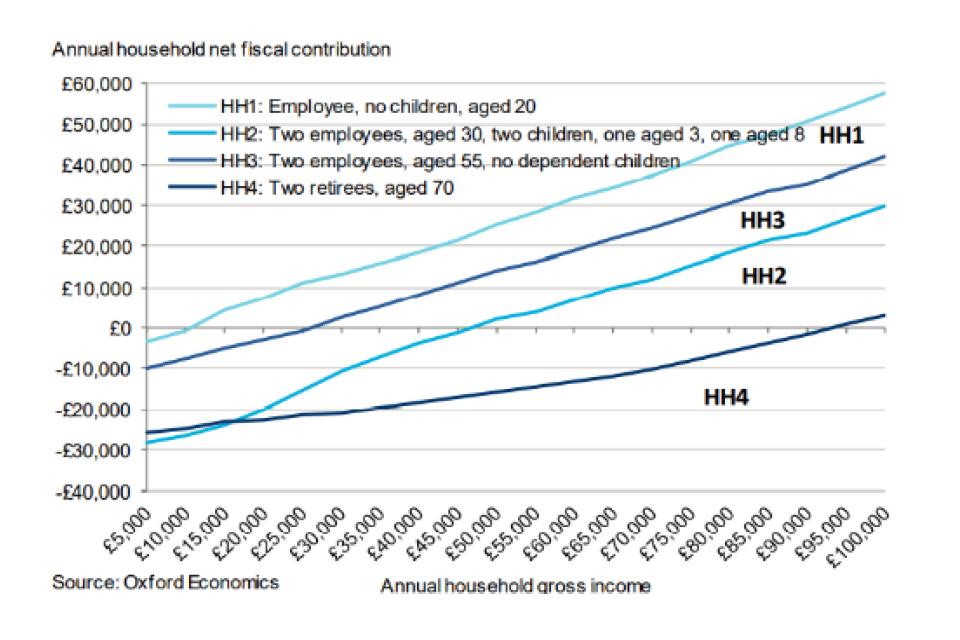

Given the relatively high salary thresholds for ICT migrants, combined with their average age and family structure, we expect most will be net contributors to the public finances. However, there will be some exceptions to this; for example, those with large families.

Chapter 4 of the report sets out in detail the consideration of the skills threshold, which we have recommended remains at Regulated Qualifications Framework (RQF) level 6+ (broadly equivalent to first degree level) and salary thresholds, which we think should reflect the current median annual gross wage of occupations which are RQF6+ (currently £43,200), with the going rate thresholds continuing to be set as now (25th percentile of occupation specific earnings). We consider that the historic inertia that the Home Office have displayed towards nominal salary thresholds, which no longer reflect prevailing labour market conditions when left in place for several years, is concerning and have, therefore, recommended that all thresholds for the ICT and other work routes are updated annually.

We have also recommended that the graduate trainee thresholds are aligned with the SW route. Whilst the graduate trainee ICT is only a small route it is required under GATS. However, as the graduate trainee element is aimed at new entrants to the labour market, rather than senior managers or specialists, firms could easily use the SW route as an alternative.

As outlined in Chapter 1, those meeting the high earners threshold, of £73,900, have slightly different rules to those meeting the general threshold. ICT migrants that earn above this amount do not have to have worked for their employer overseas for any length of time before obtaining a visa. Furthermore, ICT migrants that earn above this threshold can stay for 9 years out of a 10-year visa. For simplicity, and to avoid unnecessary changes, we recommend that the high earner threshold remains at £73,900, but that it should be updated annually in line with all other thresholds.

One of the key differences between the ICT and SW routes is treatment of allowances. Currently, allowances that are paid to ICT workers can be included when assessing whether a worker meets the salary threshold. There is limited data on allowances and there appears to be no mechanism to ensure that the values stated are paid in practice. Several stakeholders told us they value the flexibility to pay allowances and without this they may make less use of ICT, though others were less positive for various reasons, including administrative complexity. When allowances are paid as additional guaranteed salary, and the migrant is free to spend it as they please, we see no cause for concern. However, we have more concern when employers provide the migrants with physical accommodation on the condition that the migrant pays a certain amount for it. We do not have sufficient data to understand the extent to which this happens, but there is a potential risk of migrants paying above market rent for accommodation that they cannot choose, or employers overstating the value of accommodation. Also, some of these allowances for housing are tax-exempt depending on the specific arrangements between individual firms and HMRC. We have asked for more transparency on this as this is important in estimating the economic impacts of this route, which is discussed later in the report. We suggest the Home Office considers increasing both the collection and monitoring of data, (particularly accommodation allowances and reported salaries) to check compliance with the current rules. We believe there may be some non-compliance (both deliberate and accidental due to ambiguity around the core rules) and some abuse of the route.

Unlike SW migrants, ICT migrants do not need to meet an English Language Requirement, the main benefit of which appears to be a saving in time and administrative effort. We do not recommend any changes to the current policy: the exemption provides employers with flexibility, reduces time and admin for employers and employees, and is consistent with the ICT route being primarily used for temporary stays.

Switching to another migration route has only been allowed since January 2021, with ICT users now allowed to switch in-country to the SW route. Therefore, whilst the ICT route currently remains a short-term proposition with no direct route to settlement, it has an indirect route to settlement through switching. Not all stakeholders are supportive of this change, with employers raising concerns that an employee could enter the UK and immediately switch to a different sponsor on a SW visa, which could disadvantage the original sponsor and lead to issues of job retention and delays in fulfilling client contracts. Historically the MAC have supported allowing workers to switch, as for the employee this provides greater mobility, bargaining power, and hence more competitive labour markets. It is our view that the immigration system should not create artificial incentives for workers, but this must be balanced against providing certainty for businesses who may have incurred significant cost in moving the migrant to the UK. On balance, we recommend no changes to the current rules on switching.

As the ICT route is intended for temporary workers it does not offer a path (without switching) to permanent settlement in the UK and time accrued under it does not currently count towards permanent settlement. In practice, it is difficult to distinguish whether a migrant staying in the UK for 5 years, potentially bringing dependants, including children who attend school etc., is ‘temporary’. Migrants may not know their settlement intentions when they first arrive, or these may change over time, but migrants working in the UK on an ICT visa make meaningful contributions to the UK economy through taxes, skills and services from the day they arrive. We think it is only right that they should be afforded the same access to long-term settlement as those on the SW route. Such a change should also reduce the incentive for migrants to quickly switch into the SW route and therefore help to tackle some of the issues employers raised in the CfE about the costs and disruption of migrants switching. We therefore recommend that the ICT route should be a route to settlement, without the need to switch to other routes to obtain settlement. Time spent on the ICT visa should also count towards settlement if the worker does switch into another route.

Key findings and recommendations for other business mobility issues

Further to the main ICT commission, the MAC were asked to consider other business mobility issues namely: subsidiaries and secondments. Because of frequent stakeholder feedback we have also examined how short-term assignments under ICTs, or another route, could be better facilitated.

The commission raised the issue of subsidiaries and what the rules should be for employers sending teams to establish a branch or subsidiary in the UK. Existing rules (the Representative of an Overseas Business Route (RoBR) restrict the route to a single representative per sending business (Chapter 5 has more details). We found it difficult to get data on the current route as Home Office do not appear to collect much information on it; as usual, we would prefer that better data was routinely collected. Most stakeholders responding to the CfE did not express a view on this matter, but amongst those who did the general feeling was the current arrangements are too restrictive and teams should be allowed to come to the UK, as setting up a new branch or subsidiary requires different skills and knowledge and having a team in the UK would allow individuals to draw on each other’s expertise and make the process of setting up a branch easier and quicker, particularly when dealing with complex legal and regulatory requirements.

The relative lack of information on subsidiaries has made it hard to suggest detailed criteria for future arrangements, though we have found that just over three-quarters of subsidiaries established in the UK since 2018 have one, or fewer, employees. Therefore, we suggest that the default option for this visa remains a single individual and that most of the current set of rules of the RoBR should remain. However, we do not think it is sensible to allow this visa to be for the current 3 years with a possible 2-year extension. The aim of the route is to allow for the legal establishment of a business in the UK and we expect this should not generally take longer than 1 year; therefore, we suggest any individual subsidiary visa should be limited to a 2-year period, with subsequent entry to the UK using alternative routes for visas (and allowing in-country switching to such routes).

For overseas firms that wish to send a team of workers to establish a subsidiary, we suggest an alternative approach. We recommend that a new Team Subsidiary route be trialled over a 2-year period and that data be collected to allow for subsequent evaluation of the impacts of the route and refinement of the criteria. Chapter 5 sets out some suggested criteria for the trial.

We also considered the issue of secondments. The UK’s visit policy allows a client of a UK export company to be seconded to the UK company in order to oversee the requirements for goods and services that are being provided under contract by the UK company or its subsidiary company, provided the 2 companies are not part of the same group. In addition, employees may exceptionally make multiple visits to cover the duration of the contract. The policy does not permit a worker for the overseas business to reside in the UK for a continuous period exceeding 6 months, nor does it allow for dependants.

Any workers who have undertaken such a secondment outside of the remit of visit policy have, in the past, required Leave Outside the Rules (LOTR), which is only used on an exceptional, infrequent, and completely discretionary basis. We start from the basic principle that if an immigration route to the UK exists, it should be a publicised, defined route for all eligible businesses to use.

Stakeholder input on the issue of secondments was limited, with some responses to the CfE suggesting a lack of awareness of the current route. We are generally supportive of the creation of a route through which staff of an unconnected overseas business could enter the UK as part of a large contract with a UK firm, to be upskilled in the use of the product being produced by that UK firm, given the benefits to the UK economy. However, we consider that due to the relatively exceptional nature of these requests, it would be sensible for a model to be created where each case can be considered on its individual merit, from a minimum baseline. Chapter 5 gives details of the parameters of the route we recommend the Home Office create for these contracts.

The final issue we considered is that of short-term assignments. This issue was frequently raised during stakeholder engagement, so we felt it was appropriate to consider it alongside other business mobility issues. Stakeholders concerns were about the lack of an agile, time-limited, route that would allow a migrant to come to the UK to carry out specialist technical work which only requires a few days or weeks to complete, therefore making the ICT route too burdensome and slow, whilst such work is also not currently allowed under visit policy. In a lot of these examples, stakeholders are reliant on teams of workers who operate in the larger EU market (where it is viable), but the removal of free movement has made this particularly challenging, especially when time sensitive repairs are needed. It is worth noting that not all examples of issues raised were for migrants who would meet the skill and/or salary threshold of the ICT route, and it is therefore clear that this is a much wider issue than specifically for ICTs, but given the nature of this report we have focussed on short-term workers who meet the skill and salary requirements of an ICT visa.

Chapter 5 considers the pros and cons of 2 potential solutions to this issue, whether through a relaxation of the visit policy rules, or through the creation of a bespoke short-term ICT route. Upon careful consideration, we recommend that initially the Home Office explore how the visit rules could be adapted to facilitate time-limited, essential work travel to the UK and secondly consider the creation of a new short-term ICT route, should this be required, to fill the gap identified by stakeholders. This would match the salary threshold and skill level of the current ICT route, to avoid the perverse incentives of the previous short-term ICT route. Whilst this solution would work for some of the stakeholders who raised this issue, we are mindful that whether a short-term ICT route will be necessary will depend on decisions around the expansion of work allowed under the visit visa policy.

Chapter 1: Policy Context

Introduction

This chapter sets out the provisions which currently govern the Intra-Company Transfer (ICT) route. This includes:

- Eligibility for the current route;

- The use of allowances as part of the salary threshold calculation;

- How the route may be used in the future;

- Whether there is likely be any displacement into the Skilled Worker route (SW route);

- International comparisons; and

- How UK employers use the ICT route within the EU.

The policy intention for the ICT route is to enable international businesses to deploy key employees to their UK branches or head office, on a temporary basis, when there is a specific business need to do so. It underpins the UK’s international trade commitments on the intra-corporate mobility of specialist workers, senior executives, and graduate trainees.

The current ICT route

The route allows multinational companies to transfer key personnel from their overseas branches to the UK for temporary periods. It is open to established employees who have worked for their overseas branch for at least 12 months. Graduate Trainees have a reduced required period of work of 3 months, and high earners with a salary over £73,900 are exempt from this requirement.

Although the ICT route was designed for intra-corporate mobility of key personnel, in practice there is some overlap between the ICT route and the main SW route, and in certain circumstances employers with overseas offices may consider both as ways to fill vacancies in the UK. Prior to December 2020, the main SW route was T2(G) and the ICT route had several advantages over that route:

- T2(G) was subject to an annual cap which restricted the ability of businesses to hire workers from overseas. Businesses that had overseas offices could avoid this cap by hiring internally and using the ICT route which had no cap;

- ICT had no Resident Labour Market Test (RLMT) so workers could be brought in without the need to attempt recruitment of domestic workers first;

- ICT had no English language test requirement; and

- ICT permitted the payment of some allowances to be considered as part of the applicant’s salary for the purposes of meeting the salary threshold.

It is notable that prior to the removal of doctors and nurses from the T2(G) cap in 2018, these two professions accounted for 40% of visas issued under the cap, significantly reducing the number of T2(G) visas available for other occupations.

Given the reduction to the salary and skills thresholds, the suspension of the cap and the removal of the RLMT requirement from the SW route (the successor to T2[G]) we would expect to see some displacement away from ICTs under the new system.

The main remaining advantages of the ICT route over the SW route are therefore:

- The lack of English language test requirement;

- The inclusion of some allowances when assessing whether a worker meets the salary threshold;

- The multiple-entry aspect of the visa allows more flexibility for time spent in the UK over the duration of the visa; and

- The requirement for workers to only meet the salary threshold for the route when working in the UK (rather than throughout the validity period of the visa).

Table 1 in the Annex document shows a detailed side by side comparison between the ICT route, T2(G), which ended in December 2020, and the SW route, which began in December 2020 and included EU nationals from January 2021.

The ICT route was also renamed in December 2020 where it was split into two Intra-Company routes: Intra-Company Transfer and Intra-Company Graduate Trainee.

Intra-Company Transfer (ICT)

This visa is for use by employees of overseas businesses who are sent to work in a linked part of that business in the UK. Eligible workers must have worked for their employer overseas for at least 12 months and can stay in the UK for a cumulative total of 5 years in any 6-year period. Workers must be undertaking an eligible job (defined as a job in an occupation at a skill level of at least RQF6+) and be paid the higher of either the going-rate for that job (defined as the 25th percentile of the annual full-time wage of the relevant occupation) or £41,500. Workers who are paid at least £73,900 are considered to be ‘high earners’ and can stay in the UK for a cumulative total of 9 years in any 10-year period, as well as being exempt from the requirement to have worked for their employer overseas for at least 12 months.

In addition to the job the employee is sponsored to do, they are able to do a second job (up to 20 hours a week) at the same level in the same occupation, or a different occupation if that occupation is on the Shortage Occupation List (SOL).

The high earners threshold was substantially reduced from £120,000 to £73,900 in December 2020. As outlined in Chapter 4, those meeting the high earners threshold have slightly different rules to those meeting the general salary threshold: exemption from the requirement to have worked for the employer overseas for a period (compared to other ICT employees on the main route, who must have worked for their employer for a year, or 3 months if on the graduate route), and a maximum stay of 9 years in 10 (rather than 5 years in 6 for other ICT employees on the main route, and 1 year for graduate trainees).

Intra-Company Graduate Trainee

This visa is used as part of a graduate training programme for a managerial or specialist role[footnote 4]. The role must be part of a structured graduate training programme, with clearly defined progression towards the managerial or specialist role within the sponsor organisation. Graduate trainees can stay in the UK for a maximum of 1 year and this must be consistent with the structure of the training programme they are on.

The trainee must have worked outside the UK for the sponsor group for a continuous period of at least 3 months immediately before the date of their application. Sponsors have a limit of 20 trainees they can transfer per financial year.

Contractors

Workers on the ICT routes are permitted to work for third parties where the UK employer has a service contract with another UK business. In such cases, the sponsor must be whoever has full responsibility for the duties and outcomes of the job and the service must be deliverable within a defined period and cannot be routine or ongoing. Under no circumstances can the service amount to supply of staff to the third-party, as would be the case for an employment or temping agency.

Our 2015 report Review of Tier 2 (PDF, 246 KB) identified that this use of the route was widespread, and that use of migrants to service third-party contracts (mainly in the IT sector) gave a substantial cost advantage over domestic firms. The MAC considered that this would disadvantage firms in the UK who do not have access to this source of labour and also stated a concern that this would not help with the stock of IT skills within the UK - where there is access to highly skilled labour abroad there is little incentive to develop the UK workforce. The analysis indicated that there is a far greater potential for displacement and undercutting of UK workers with the use of the contractor route than in the conventional use of the ICT route.

We suggested that action should be taken to ensure that it is only used by those highly specialised migrants that partners in industry claim to need. We therefore recommended[footnote 5] that a new route be created alongside the conventional ICT route which was designed specifically for third-party contracting, and that a higher threshold be applied to this. Subsequently, however, rather than creating a separate route for third-party contracting, the Home Office instead closed the short-term ICT route and raised the salary for all workers (whether on a third-party contract or not) to £41,500.

Allowances

Allowances that are paid to ICT workers can be included when assessing whether a worker meets the salary threshold, provided they are guaranteed for the duration of the applicant’s assignment. This could, for example, include mobility premium, cost of living premia, or London weighting. A particularly important allowance that can be counted towards the salary threshold is accommodation (up to 30% of the total salary package for applicants in the ICT category, or 40% of the total salary package for applicants in the ICT Graduate Trainee category). One-off bonuses cannot be included and cannot be pro-rated.

The salary stated on the CoS must be the total including gross basic pay and all permitted allowances. The CoS must also provide a separate total of all allowances and an explanation of what they are for.

The permitted tax exemptions on expenses and allowances are the same for resident workers, SW migrants, and ICT migrants. However, ICT workers are more likely to be eligible for tax-free accommodation allowance due to the temporary nature of the work many of them do. The only allowances that count towards the salary threshold and are eligible for tax exemptions are accommodation allowances. HMRC’s general rule is that an employee who attends a temporary workplace for a period of up to 24 months can obtain relief for accommodation allowance.

Firms that use ICTs extensively have pre-existing agreements with HMRC that define which allowances are tax-exempt, but these may vary by firm. As we do not have access to these agreements, we are not able to analyse the scale of tax exemptions from the use of allowances. Home Office Management Information is also limited and not all employers that pay allowances provide a disaggregated figure in applications.

Immigration Skills Charge (ISC)

Whilst not applying the ISC to the ICT route was previously considered by the MAC, it was ultimately decided that ICT workers could displace UK workers and as such the ISC should apply, with the exception of the Graduate Trainee route. As part of the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement (the UK’s free trade agreement with the EU), the UK has committed to exempt EU ICT workers from the ISC from no later than 01 January 2023.

Future use of the ICT route

With the introduction of the SW route, which is uncapped and does not include an RLMT requirement, there is the potential to see displacement from the ICT route. The costs of a visa under the SW route and ICT are commensurate, though there is a reduction for SW roles on the SOL. The ICT visa costs between £610 and £1,408 per person depending on the length of stay (Graduate Trainee is £482), plus an additional charge for the Immigration Healthcare Surcharge of £624 per year. Both ICT and SW applicants also need to show they can support themselves in the UK during the first month of their stay and must therefore have £1,270 in funds available to them, unless their employer guarantees to cover these costs (which most ICT employers do).

The current ICT route does not lead to settlement, although switching into the SW route is now permitted. Stakeholders raised two main concerns about this; some felt that the ability to immediately switch was unwelcome, for reasons including business continuity and cost of bringing a worker to the UK; others raised concerns that it was unfair that time spent on the ICT route could not be counted towards settlement after switching.

Some stakeholders have stated that in the short-term they are either considering or already using the SW route in place of ICT, but there was a lack of confidence that the suspension of the cap on the SW route would remain in the long term. There were also certain roles that some stakeholders still felt worked better under the ICT route, which was seen as more agile. Therefore, stakeholders were strongly in support of retaining an ICT route to work alongside the SW route.

Stakeholders also advised that for staff in the UK on short-term postings, or those that required multiple entry visas due to their type of business, the ICT route with its lack of an English test requirement is a better fit. However, there was a consistent theme in stakeholder engagement that businesses would like to see an even more agile route for ICT short-term workers, with a time limit of 3-6 months. Many stakeholders who expressed a view in either stakeholder meetings or the CfE felt that allowances are an integral part of the ICT route and a necessary element for those workers. Views on both allowances and the lack of an English language test requirement are discussed in further detail in the Chapter 4 on Technical Rules.

International obligations (GATS)

The UK is a member of the World Trade Organisation’s (WTO) General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS), which is an Annex to the Agreement Establishing the WTO (or the WTO Agreement). The GATS was created to extend to the service sectors the system for merchandise trade set out in the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, but with some differences to reflect the different nature of services trade. The GATS was created at the Uruguay Round, and entered into force in January 1995.

The GATS defines services trade by four modes of supply: Cross Border supply (Mode 1), consumption of a service abroad (Mode 2), supplying a service through commercial presence (Mode 3) and providing services through the presence of a natural person (an individual) (Mode 4). There is no single ‘Mode 4 visa’, instead, in order to support Mode 4, the UK has pledged to allow the entry into and temporary stay of natural persons for business purposes in various categories in the UK’s GATS schedule of commitments. These include Intra-Company Transferees where: they are senior managers or specialists; are transferred to the UK by a company established in the territory of another WTO member; and are transferred here in the context of the provision of a service through a commercial presence (of the same group) in the UK.

Under the GATS the UK has committed to allow this without applying an economic needs test, such as the RLMT. The UK would be in breach of its international obligations were it to either introduce an economic needs test or place a limit on the length of stay of ICTs below 3 years (GATS) or below what it has committed to in specific Free Trade Agreements (FTAs). In addition to the GATS, the UK has also made commitments on Graduate ICTs in some of its FTAs and will need to uphold these international commitments as well.

International usage

We have used stakeholder feedback to review a small set of other countries’ approaches to intra-company transfers. We have spoken to officials from the United States, South Korea, South Africa, and Germany regarding their respective equivalents of the ICT route.

United States

The US uses its L-1 visa for intra-company migration. On the whole, stakeholders did not consider the US system to be easy to use and felt that due to the interview process there was uncertainty in the process.

The L-1 visa has the following characteristics:

- There are no caps on the L-1 visa route.

- The L-1 route has no minimum salary requirements but must meet the federal minimum wage requirements. The wage may also be paid in the home country.

- Foreign nationals using an L-1 must be coming to work in the US as a manager, executive or specialised knowledge employee. To be recognised as a manager, the US would expect the applicant to be managing people who manage others, rather than being a direct manager.

- ‘Specialised knowledge’ is not a defined term within the route, so is open to interpretation, which has led to litigation.

- The L-1 Visa Reform Act 2004 prohibits the outsourcing of L-1B employees to unrelated third parties. The petitioning company (sponsor) must have a qualifying legal relationship with an overseas entity who wants to send workers to the US e.g. Honda Japan can incorporate Honda US which would be a subsidiary.

- Newly establishing companies, who are establishing in the US- L-1 ‘New Office’ petitions, can be granted a maximum of 1 year to open a new office. There is no limit on the number of people that can be brought in under this route but there is a high level of scrutiny depending on the circumstances of the company etc.

- To qualify as newly establishing company, the applicant must demonstrate at time of application that they have acquired sufficient physical premises in the US, that they have the financial ability to commence doing business and that they will support the beneficiary in a managerial or executive position within 1 year.

South Korea

South Korea uses its D-7 (Intracompany Transfer Visa) to allow entry of managerial or executive-level employees with specialized knowledge and skills that are not readily available in South Korea’s domestic labour market.

On the whole, stakeholders highlighted South Korea as a good system, especially highlighting the flexibility and the option to extend for a longer period in-country.

The D-7 visa has the following characteristics:

- There are no caps on the D-7 visa route;

- The D-7 route has no minimum salary requirement but must meet salary requirements associated with industry standards, the position and applicant’s experience. There is no requirement for the wage to be paid in the home country; they can be paid either by the overseas sending company or the sponsoring entity; and

- Foreign nationals using the D-7 route must be coming to work in South Korea as a manager, executive or specialised knowledge employee. These are defined as follows:

- Executive: Executive is defined as someone who primarily directs the management of the organization; exercises wide latitude in decision making; and receives only general supervision or direction from the board of directors or shareholders of the organization (an executive does not directly perform tasks related to the actual provision of the service of the organization);

- Senior Manager: Senior Manager is defined as someone who is in charge of establishing and implementing goals and policies of the company or the department; has the authority to plan, direct and supervise; has the authority to recruit and dismiss or recommend recruiting, dismissing; and exercises supervisory and control function over other supervisory, managerial professional service suppliers, and employees who directly engages in supply of service) or exercises discretionary powers over their daily tasks; and

- Specialist: Specialist is defined as someone who possesses proprietary experience and knowledge at an advanced level of expertise essential to the research, design, techniques, or management of the organization’s service.

South Africa

South Africa uses the Intra-Company Transfer (ICT) work visa for highly skilled foreign nationals who will transfer to a South African branch or subsidiary of their current employer.

Stakeholders highlighted South Africa as a good system, especially highlighting the short-term route for intra-company transfers.

The ICT work visa has the following characteristics:

- There are no caps on the route;

- The route has no minimum salary requirement;

- The migrant can be on local terms and conditions including payment of salary, but they must not be directly paid or employed by the South African sponsoring entity;

- South Africa’s ICT work visa route is focused on upskilling the workforce in South Africa and these skills must not already be present in the South African branch; and

- The migrant may be required to be employed in a specific occupation, referred to as ‘mission specific’.

Germany

Germany uses the EU Intracompany Transferee (ICT) Permit, locally called the ICT Card, which is in place across most of the EU.

This route is suitable for intracompany transfers of highly skilled managers, specialists, or trainees. The EU ICT Permit enables mobility within the EU, within the company group. ICT Permit holders from another EU country can work at a group entity in Germany for under 90 days after filing a notification, or for longer after filing a Mobile ICT Card application. ICT Card holders from Germany can similarly work at group entities in other EU countries after filing a notification or mobile permit application.

The EU Intracompany Transferee (ICT) Permit, locally called the ICT Card has the following characteristics:

- There are no caps on the ICT card route;

- The ICT card route is a residence title and so is not a visa;

- The route is time limited so the migrant would be initially granted entry for 3 years and settlement is not automatic, however if the migrant meets the resident requirements than they may qualify for settlement; and

- ICT card route is not often used - in 2020, 3000 ICT visas were granted. The German immigration system has a much larger number of routes for migrants to enter than the UK which may partly explain different levels of use.

Summary

We have undertaken a review of the ICT routes in a small sample of other countries and set out the details of these routes. None of the countries we looked at have a language requirement to enable use of the ICT (or equivalent) route. It appears that most countries view the ICT route as a way of getting highly skilled and knowledgeable overseas employees to share their skills and experience with local workers. To achieve this aim, there is a requirement in most countries to illustrate these skills as part of the visa route.

During stakeholder meetings and in responses to the Call for Evidence and stakeholder submissions, some stakeholders also mentioned various practices relating to ICT policy in other countries, chiefly those they thought particularly helpful or unhelpful. These points, where made, are discussed during the relevant thematic chapters.

Chapter 2: Primary research and engagement

Introduction

This chapter details the primary research and engagement with stakeholders that was carried out to support this commission. Although findings from the primary research and stakeholder engagement are found elsewhere throughout this report, within the relevant chapters, this chapter also details who responded to the Call for Evidence (CfE) questionnaires and participated in the stakeholder engagement events that took place.

Primary research and stakeholder engagement carried out to support this commission

As with other commissions, we carried out a programme of stakeholder engagement and launched a CfE to inform our response. In addition, we commissioned qualitative research to provide further information on how the ICT route works for both employers and employees who use the route.

The stakeholder engagement consisted of:

- Four meetings with stakeholders that were convened on our behalf by Professional services companies working with employers who use the immigration system;

- Two meetings with stakeholders convened on our behalf by the Scottish Government and NI Executive;

- Four meetings with embassies and consulates (Germany, USA, South Korea, and South Africa); and

- Four meetings with the top four users of the ICT route (in terms of number of Certificates of Sponsorship (CoS) issued).

In addition, several respondents who submitted both CfE and stakeholder submissions conducted their own stakeholder consultations, the results of which are reported passim along with the responses themselves.

There were two parts to the primary research carried out to support this commission:

- An online CfE, comprising two questionnaires and an invitation to submit further evidence either as an addendum to the questionnaire response, or separately to the MAC inbox; and

- A programme of qualitative research interviews, which was carried out on our behalf by an external research contractor, Revealing Reality.

Findings from the stakeholder meetings, CfE questionnaire responses and additional evidence submitted, and from the qualitative research, have been analysed and written up throughout the report to support and illustrate the relevant sections. We also present quotes (generally anonymised to protect participant confidentiality) and an anonymised case study from these sources. The remainder of this chapter provides more detail on the characteristics of those who responded to the CfE, and of those who participated in the qualitative research that was commissioned.

We have analysed the outputs of the CfE and qualitative research for any specific impacts or potential impacts on the nine protected characteristics under the Equality Act (2010). There were very few of these, but we have indicated where they were raised by participants.

The Call for Evidence

The CfE for this commission comprised 2 questionnaires. One was aimed at employers that had questions relating to the organisation’s direct experiences of using the ICT route. The other was primarily aimed at those representing the views of other organisations: representative organisations (such as trade and membership bodies), Professional services companies (such as law firms) dealing with immigration on behalf of others, and individuals, see the Annex document. Respondents were initially directed to a landing questionnaire which forwarded them to the most appropriate of these questionnaires for their circumstances. As part of the online CfE, individuals and organisations were also able to submit other evidence directly to the MAC – either as an attachment to a completed questionnaire, or by email.

The CfE questionnaires were initially open for 12 weeks, from March 23rd to June 15th, and the questionnaire deadline was extended by 1 week, closing on June 22nd. Sixty-eight responses were received across both questionnaires, and in addition to this, a further 11 respondents provided other evidence, either by emailing documents, or by attaching documents to their CfE response.

The main CfE questionnaires asked respondents about 3 key themes:

- Usage of ICT: including the main, contractor, and graduate routes;

- Views on ICT and the various rules around the route, including: skills and salary thresholds for all routes; length of experience in current role; the ability to work for third-party clients; the inclusion of allowances as part of the salary package; length of stay; English language requirement; and experiences of using the representative overseas business route to set up subsidiaries; and

- Future use and views on ICT policy: including the effects of the Skilled Worker (SW) route on future ICT usage, views on potential changes to rules around subsidiaries and secondments, and any changes that should be made to ICTs in the future.

As expected, given the comparatively niche nature of the subject matter compared to other subjects such as the Shortage Occupation List (SOL) on which the MAC consults, and the continuing disruption to businesses caused by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, we received a smaller number (68) of responses to the ICT CfE than to previous commissions carried out by the MAC[footnote 6]. As well as causing disruption to businesses, the COVID-19 pandemic may also have reduced engagement with the route: a number of organisations reported lower ICT usage in the last year during the period of national restrictions (ICT usage is discussed further in Chapter 3 on economic impacts), and it is possible that because of this, some organisations felt disinclined to participate.

However, the decision to extend the CfE questionnaire deadline for a further week did result in a small increase in the number of responses from both representative organisations and employers.

Given that we expected to receive a smaller number of responses to the ICT CfE at the outset, we chose to use the questionnaires as a framework for asking deeper open questions. Because of the small numbers of responses received, and the self-selecting nature of the sample, the CfE does not constitute a formal statistical survey, and we have therefore avoided the use of percentages. Due to the large number of unrestricted free-text questions, the CfE responses contain lots of rich qualitative information. We have used evidence from the CfE, written submissions and the stakeholder engagement meetings we held to inform our assessment.

In this chapter, we give a brief overview of the responses to the CfE. We report the characteristics of the respondents for both questionnaires (including size, sector, and location for employers and representative organisations) and how their organisations use ICTs. Views on various aspects of ICT rules and policy, and on future use and policy, are reported in conjunction with other analysis throughout the report.

Who responded to the Call for Evidence?

A total of 68 responses were received across the two questionnaires: 28 respondents submitted replies to the employer questionnaire, and 40 respondents submitted their replies to the representative organisations’ questionnaire. Across both questionnaires, a further 172 responses were started but not submitted.

When analysing the CfE responses, it is always necessary to acknowledge that those who respond do so from a specific perspective, whether as an employer using the ICT or similar routes, as a representative organisation representing other users or potential users, as a Professional services company working with employers who use the immigration system, a think tank or charity, or an individual. We are grateful for the contribution of all those who have participated and for the time they have taken to respond.

Respondent characteristics – employers

- Looking at the sample of 28 responses to the employer questionnaire, information and technology (8) was the most represented industry, followed by professional, scientific and technical activities (7): this is not surprising given we know these sectors are heavy users of the route.

- 20 respondents reported that they represented large businesses (250 or more employees), this is as we would expect as users of the ICT visa route are often large businesses. Although responses came from all over the UK, London (8) was the region named by the most respondents. Nine organisations were based UK-wide. No organisations were based in Wales and Northern Ireland, whilst 3 were based in Scotland.

- 21 respondents reported that their organisation was based at more than one site (within and outside of the UK). Four respondents answered that they were based at multiple sites within the UK, whilst 3 reported that they were based at a single site within the UK.

- 21 respondents said they had one or more sites based in other European Economic Area (EEA) countries, 19 reported that they were based in non-EEA countries and 11 reported that they had sites in the Republic of Ireland (respondents were able to pick more than one option).

Respondent characteristics – representative organisations

- Of the 40 individuals who responded to this questionnaire, 14 respondents answered as a representative or membership organisation, with a further 7 responding as an immigration lawyer or similar immigration representative or advisor. 4 respondents selected “other” – including a think tank, global mobility consultant and a charity. 15 respondents provided evidence to the questionnaire as an individual in a personal capacity: this is a higher number of these responses than we had anticipated, and they are therefore discussed separately later in the chapter.

- 6 respondents represented between 500 and 4,999 organisations, whilst 3 represented more than 5000. Most of those representing other organisations said that they did so UK-wide.

- The most represented industry was manufacturing (8)[footnote 7], followed by professional, scientific, technical (6) and information technology (4). Again, this is unsurprising, as manufacturing is also well represented in ICT usage compared to most other sectors.

- 13 respondents represented organisations that employed between 50 and 249 employees, 13 organisations that employed between 250 and 499, and 14 organisations that employed more than 500.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, almost all (25 out of 28) of the employers responding to the CfE questionnaire had used the ICT route within the last 5 years, and 13 respondents from representative organisations reported that the organisations they represented had used the ICT route within the past 5 years. Table 2.1 summarises the numbers who responded to the questionnaire and said that they/those they represented had used each ICT type.

Table 2.1: Usage of ICT visas in the last 5 years as reported by CfE respondents

| Type of ICTs used in the last five years | Employer responses | Representative organisation responses |

|---|---|---|

| ICT route (including Tier 2 (ICT) in the long-term staff subcategory) – paid between £41,500 and £73,899, conventional | 24 | 11 |

| ICT route (including Tier 2 (ICT) in the long-term staff subcategory) – paid between £41,500 and £73,899, contract | 6 | 5 |

| ICT route (including Tier 2 (ICT) in the long-term staff subcategory) – paid £73,900 or over, conventional | 19 | 10 |

| ICT route (including Tier 2 (ICT) in the long-term staff subcategory) contract | 5 | 4 |

| Graduate trainee route (including Tier 2 (Intra-company Transfer) in the graduate trainee subcategory) | 5 | 3 |

| Tier 2 (Intra-company Transfer) in the short-term staff subcategory – paid between £24,800 and £41,499, conventional | 11 | 5 |

| Tier 2 (Intra-company Transfer) in the short-term staff subcategory – paid between £24,800 and £41,499, contract | 5 | 4 |

Base: All employers and representative organisations were asked this question. Individuals responding in a personal capacity and Professional services companies working with employers who use the immigration system were not asked this question. Employer responses refer to their own organisation’s usage of the different ICT routes and Representative organisation responses refer to the ICT usage of the organisations they represent. This was a multi-code question; respondents had the option of choosing more than one ICT visa type.

When asked how many ICTs their organisation had used in total last year, employer responses ranged from 0 to 1,674. Some respondents reported that they had used lower numbers of ICTs than usual due to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, 1 information technology company reported using 240 ICTs in 2018, 189 in 2019, and 42 in 2020, illustrating the effect of the pandemic on their usage of the route. This was substantiated by similar evidence from representative organisations relating to the usage of those they represented.

Employers and representative organisations gave several reasons for their organisation’s usage of the ICT route (or the reasons that those they represented did so). These included:

- Fill skills shortages for short-term assignments – these employers said that the ICT route was the right visa choice for short-term projects and assignments. The ICT route enables them to send employees with the necessary skills to where they are needed most within the organisation;

- No English language requirement – employers said they viewed the fact that the ICT visa route does not have an English language requirement as an important advantage as they are able to avoid additional costs and delays in deployment of staff;

- Provide international experience to employees – respondents felt that international experience was important for employees as it contributes towards their career development. This helps to develop and promote talent within the organisation as those coming from overseas can share their knowledge and skills with their colleagues in the UK, and vice versa;

- Straightforward and efficient system – employers told us that they felt the ICT route was easy to use compared to other visa routes. An ICT visa is quicker to procure than other alternatives and allows for staff to be deployed responsively when a need arises;

- The ICT route does not require a Resident Labour Market Test (RLMT) – this means that employers do not have to prove that they have advertised for a job within the UK to fill a vacancy. The RLMT was previously applicable to T2(G) and may be a reason why some employers preferred the ICT visa over the T2(G) visa route. The RLMT does not apply to the SW route; and

- Knowledge transfers, where this is required between different areas of a business on a short-term assignment or project basis. This might include sending a specialist to the UK to share their knowledge and expertise with other members of the team. One respondent referred to such people as “culture carriers”, i.e. people that have worked for the organisation for years who act as ambassadors to increase the performance of other sites.

We use ICT visas to bring colleagues from other branches and entities […] to fill short term and long term assignment needs due to skill shortages in business functions like Technology and Finance, as well as bringing in colleagues to help with times of high volume, i.e. holiday period, maternity cover, etc. We endeavour to fill these roles with local colleagues; however, these niche skills are not always plentiful in the UK market and we need to recruit from our global network to fill these shortages.

CfE, Employer, Wholesale and retail trade

Roles for which the ICT route was used

Employers and representative organisations reported that they supported a variety of different roles under the ICT route within their organisation or the organisations they represented. The roles described were at several different levels, from graduate trainee, to business partner, and executive vice president.

- In the IT sector roles included software designer and engineer, system analyst, software development engineer, cloud and data management, cyber security, project management, and service delivery.

- Other senior and specialist roles reported were senior scientist; architect; technical director; finance director; compliance consultant; marketing manager; HR service lead; operations leader; and general manager.

- Respondents reported that they or the organisations they represented had used ICT visas for roles throughout the different areas of their organisations, including management, communications, HR, finance, facilities management, logistics, and sales. As expected, most roles reported were management roles or technical and specialist roles.

Reasons for not using the ICT route

Two employers told us that they had not used the ICT route within the last 5 years because of the uncertainty caused by the UK’s exit from the European Union (EU) and because there had been no requirement for it.

- Respondents on the representative organisation questionnaire gave a variety of reasons for the organisations they represented not currently using the ICT route. These included: the administrative burdens of the route; the responsibility of sponsorship; that the ICT route does not lead to settlement; some organisations not having sites outside of the UK; COVID-19 travel restrictions; high salary threshold for ICT routes; ability to meet needs through free movement from EU (which has now ended); or that the application process was complicated.

Individual responses received from the representative organisation questionnaire

As part of the representative organisation questionnaire we invited responses from individuals who wanted to give evidence in a personal capacity. We did this to attract participation either from those who had first-hand experience of using the ICT route themselves, or from other individuals who wanted to share their views on ICTs. Interestingly, almost a quarter of the responses to the representative questionnaire came from individuals completing the questionnaire in a personal capacity. Data captured from the online questionnaire allowed us to see which countries individuals were responding from. Of the 15 individual responses we received, 6 were completed by respondents in India, with the remainder being completed by respondents in the UK. The information we have does not allow us to be certain about whether these respondents were (or had been) on the ICT route, however, as outlined below, from the information given it appeared that at least some were. A further email submission was also received from an individual who also said they were in the UK on an ICT visa.

Some of the themes raised in the responses from those completing the questionnaire from India included an alleged “corruption” of Indian IT companies, and the apparent exploitation of “loopholes” in the UK immigration system (it is worth mentioning here that there had been recent coverage of this in the Indian press)[footnote 8]. Five of the respondents in India had strong views regarding the UK being “taken advantage of”, with some remarking that priority for work should be given to British citizens. Within these responses, concerns were also raised about whether ICT applicants from India were properly qualified, with respondents criticising the academic rigour of certain computing degrees. Chapter 4 discusses these issues in greater depth.

When asked about whether allowances should be included in the salary thresholds for ICTs, 1 respondent answered “no”, commenting that the accommodation provided for employees on the ICT route was, in their opinion, “unhygienic and overcrowded”. The issue of accommodation is discussed further in Chapter 4.

Although we also cannot be sure of the exact situation of the other 9 individuals (all of whom responded from the UK), it appears that at least some of these were people currently in the UK on the ICT route, as to a large extent these responses were about the rules on settlement (this was also the content of the email response we received from an individual who said they were currently in the UK on an ICT) including the impact on families of not having settled status (an issue that Chapter 4 discusses in greater depth). The others filled in the questionnaire in order to convey various perspectives, for example:

- A respondent from the UK shared their view that the ICT salary threshold was too low. In their opinion, the salary thresholds should be calculated by considering the salary paid to employees in the same company who are carrying out similar work. This person raised concerns over UK based workers being paid more than ICT employees; and

- Another individual respondent from the UK who completed the questionnaire in an individual capacity appeared to be knowledgeable on the usage of the ICT route, and the relative merits of the ICT route over the SW route, although it was not clear in what capacity (whether professional or personal) this knowledge had been obtained. They stated that the ICT route is “very streamlined” to use once the CoS is received, suggesting that they have had first-hand experience of using the ICT application system. It is unclear whether they were speaking from an employer or employee perspective, as they referred to “employees”, “clients”, and “service providers”. This respondent felt strongly that there should be a path from the ICT visa to settlement.

Further details on the content of responses from those responding to the CfE in a personal capacity are given alongside information from other respondents, individuals and employers interviewed as part of the qualitative research, and from stakeholder submissions and engagement, throughout the remainder of this report.

Qualitative research

Qualitative research provides additional understanding and depth of insight into a subject and allows links to be made between themes and sub themes. Although it cannot provide a measure of the extent to which an issue applies, it can indicate depth of feeling and illustrate the diversity of experience. In this commission, the qualitative research also enabled us to gain insight directly from individuals who were using the route, in a confidential and anonymised way. The qualitative research interviews were carried out by Revealing Reality, an independent research contractor, on behalf of the MAC. Interviews were carried out with 15 employees and 15 employers who had used the ICT route. After a full Data Protection Impact Assessment process, research respondents were recruited through:

- UK Visas and Immigration (UKVI) Customer Satisfaction Survey respondents who had agreed that the Home Office could contact them to carry out further research; and

- User contact details from the Home Office’s Certificate of Sponsorship records (both employees and employers).

The interviews took place over Microsoft Teams or telephone and were between 45 minutes to 1 hour in duration. Fieldwork took place between 25 June and 10 September 2021. The interviews followed a semi-structured discussion guide (see the Annex document), which was jointly developed by Revealing Reality and the MAC. We have referred to research findings where relevant in this report; however, we will also be publishing a full report from Revealing Reality separately. Table 2.2 shows the sample criteria and characteristics of interviewees. We aimed to interview respondents with a spread of characteristics, reflecting the prevailing characteristics of the route but also capturing some of the diversity within the sample of ICT users.

Table 2.2: Sampling characteristics of research interviews carried out by Revealing Reality

| Sampling criteria | Employers (15 respondents) | Employees (15 respondents) |

|---|---|---|

| Type of ICT visa | 5x contractor 10x conventional |

5 x contractor 10 x conventional |

| ‘Grade’ of ICT visa | 1x focus specifically on graduate trainee 14x used ICT visa for specialist and managers |

A mixture of: senior managers; specialists; and graduate trainees |

| Sector | 8x IT workers 7x non-IT workers (often finance, travel or energy industries) |

10 x IT sector 5 x non-IT role (often finance or travel sectors) |

| Number of employees | 2 x under 1000 employees 1 x 1001-5000 employees 0 x 5001 – 20,000 employees 5 x 20,001-50,000 employees 1 x 50,001 - 100,000 employees 6 x 100,0000 + employees |

N/A |

| Organisation location | 5 x offices across UK 1 x England-wide 7 x London based 2 x outside of London |

N/A |

| Nationality | N/A | 8 x Indian workers 7 x non-Indian workers (from 6 different countries) |

| Gender | N/A | 8 x men 7 x women |

| Age | N/A | 2 x 20-30 8 x 31-40 5 x 41-50 |

| Dependants | N/A | 8 x brought dependants 7 x no dependants |

Source: Revealing Reality.

Note: Indian and IT workers were listed separately in the sample criteria because they represent the largest users of the ICT route.

Chapter 3: Economic impacts chapter

Introduction

This chapter examines the economic impact of Intra-Company Transfer (ICT) migrants on the UK economy focusing on:

- Labour market impact;

- Productivity;

- Trade and investment;

- Impact on UK firms;

- Fiscal impacts; and

- Regional impacts

Within each, we will examine the conventional and third-party contracting use of the route.

Background

The ICT route is intended to provide a temporary route for sponsors to transfer senior managers and specialists from overseas where a UK presence is required. Employees must be established workers of multinational companies who are being transferred by their overseas company to do a skilled role for a linked entity in the UK. The route can help to introduce new skills and innovation into the UK if ICT migrants complement the UK labour force, bringing in expertise and knowledge that can be transferred to UK workers. In this chapter we also explore the impact of ICT migrants on the domestic population.

Within the ICT route two distinct uses have emerged, which we will refer to as the conventional route and contractor route throughout this chapter. The conventional route allows employees to work for the sponsor organisation within the UK, whilst the contractor route allows employees to carry out work for a third-party organisation whilst still being employed by the sponsor. We will examine the contractor route in greater detail as it operates quite differently. Stakeholders provided examples of ways in which the route has been used which we examine later in this chapter.

Current use of the route

Figure 3.1 shows the number of visa applications for the ICT route compared to Tier 2 General (T2(G)). T2(G) has been replaced by the new Skilled Worker (SW) route as part of the new Points Based System (PBS). Use of both ICT and T2(G) have steadily grown over time, and T2(G) overtook the ICT route in terms of the number of applications in 2016. T2(G) accounted for 61% of total T2 visas issued in 2019.

Figure 3.1: Total visa applications for T2(G) and ICT route, 2010-2020

| Year | ICT | T2 Gen |

|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 36,443 | 23,989 |

| 2011 | 36,321 | 21,374 |

| 2012 | 37,884 | 30,746 |

| 2013 | 41,043 | 39,364 |

| 2014 | 44,090 | 42,661 |

| 2015 | 44,147 | 42,911 |

| 2016 | 43,653 | 45,291 |

| 2017 | 39,162 | 46,859 |

| 2018 | 41,714 | 53,412 |

| 2019 | 42,294 | 66,788 |

| 2020 | 22,895 | 51,297 |

Source: Home Office Management Information.

Certificate of Sponsorship (CoS) data 01 Jan 2010 – 31 Dec 2020.

Note: Used CoS. CoS is assigned to a migrant by their sponsoring employer and the migrant can then use the certificate number to make a visa application.

ICT includes all categories including contractor and conventional and long-term and short-term migrants.

Figure 3.2: Total ICT visa applications by usage, 2010-2021

| Year | Contractor | Conventional |

|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 19,607 | 16,836 |

| 2011 | 19,728 | 16,593 |

| 2012 | 21,064 | 16,820 |

| 2013 | 22,926 | 18,117 |

| 2014 | 25,905 | 18,185 |

| 2015 | 26,277 | 17,870 |

| 2016 | 26,701 | 16,952 |

| 2017 | 23,510 | 15,652 |

| 2018 | 25,776 | 15,938 |

| 2019 | 26,745 | 15,549 |

| 2020 | 15,408 | 7,487 |

| 2021* | 6,126 | 3,074 |

Source: Home Office Management Information.

Certificate of Sponsorship (CoS) data 01 Jan 2010 - 30 Jun 2021.

Notes: Used CoS. CoS is assigned to a migrant by their sponsoring employer and the migrant can then use the certificate number to make a visa application.

*2021 is not full year data and is only up to 30 Jun 2021.

Figure 3.2 shows the split between contractor and conventional ICT usage over time. The contracting route makes up the larger percentage of ICT visas[footnote 9] (63% in 2019). As the contractor route is used fundamentally differently to the conventional route, there are implications for policy which we will examine later in this chapter.

Although not a distinct route for the Information Technology (IT) sector, the route is dominated by IT firms, with the sector making up 81% of overall ICT contractor usage in 2019. Indian nationals account for 97% of ICT contractor visas (Table 3.3). This is much larger than their equivalent share for the conventional (35%) and T2(G) route (24%).

Table 3.3: Nationality of ICT migrants, 2019

| Nationality | Contractor | Nationality | Conventional | Nationality | T2(G) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| India | 96% | India | 32% | India | 27% |

| US | 1% | US | 22% | Philippines | 10% |

| Japan | 11% | China | 7% | ||

| China | 6% | US | 7% | ||

| Australia | 4% | Nigeria | 6% | ||

| Canada | 3% | Australia | 4% | ||

| South Africa | 3% | Pakistan | 4% | ||

| Brazil | 1% | Egypt | 3% | ||

| South Korea (Republic Of Korea) | 1% | Canada | 3% | ||

| Russian Federation | 1% | Malaysia | 3% |

Source: Home Office Management Information.

Certificate of Sponsorship (CoS) data 01 Jan 2019 – 31 Dec 2019.

Notes: Only countries with 1% or more have been reported.

Used CoS. CoS is assigned to a migrant by their sponsoring employer and the migrant can then use the certificate number to make a visa application.

Table 3.4 shows the top 10 firms using the route split by contractor and conventional use of the route. The top 4 firms sponsored 34% of all ICT visas in 2019. The contractor route is dominated by a relatively small number of large users, with the top 4 firms accounting for 53% of contractor visas. The top 10 users for the contractor route account for 78% of overall visas in comparison to the conventional route where the equivalent figure is just 20%.

Table 3.4: Top 10 firms using the ICT contractor route, 2019

| Organisation | Contractor count | Total share | Conventional | Nationality | T2(G) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tata Consultancy Services | 6,200 | 23% | 32% | India | 27% |

| Cognizant Worldwide Limited | 3,000 | 11% | 22% | Philippines | 10% |

| Wipro Limited | 2,500 | 9% | 11% | China | 7% |

| Infosys Limited | 2,500 | 9% | 6% | US | 7% |

| Tech Mahindra Limited | 1,300 | 5% | 4% | Nigeria | 6% |

| Capgemini UK PLC | 1,300 | 5% | 3% | Australia | 4% |

| Accenture (UK) Limited | 1,200 | 5% | 3% | Pakistan | 4% |

| IBM UK Ltd | 1,000 | 4% | 1% | Egypt | 3% |

| HCL GREAT BRITAIN LIMITED | 1,000 | 4% | 1% | Canada | 3% |

| Syntel Europe Limited | 500 | 2% | 1% | Malaysia | 3% |

| Contractor total | 26,700 |

Table 3.4: Top 10 firms using the ICT conventional route, 2019

| Organisation | Conventional count | Total share | Conventional | Nationality | T2(G) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP | 500 | 4% | 32% | India | 27% |

| Ernst & Young | 400 | 3% | 22% | Philippines | 10% |

| KPMG LLP | 400 | 3% | 11% | China | 7% |

| Deloitte LLP | 400 | 2% | 6% | US | 7% |

| Huawei Technologies (UK) Co., Ltd | 300 | 2% | 4% | Nigeria | 6% |

| Shell International Ltd | 200 | 2% | 3% | Australia | 4% |

| Sopra Steria Limited | 200 | 2% | 3% | Pakistan | 4% |

| HSBC Holdings plc | 200 | 1% | 1% | Egypt | 3% |

| BP plc | 200 | 1% | 1% | Canada | 3% |

| Cyient Europe Limited | 200 | 1% | 1% | Malaysia | 3% |

| Conventional Total | 15,500 |

Source: Home Office Management Information.

Certificate of Sponsorship (CoS) data 01 Jan 2019 – 31 Dec 2019.

Notes: Excludes graduates. Used CoS. CoS is assigned to a migrant by their sponsoring employer and the migrant can then use the certificate number to make a visa application. MAC analysis of HO MI may not match other statistics due to filtering.

Table 3.5 shows that males make up a much larger percentage of overall ICT usage for both contractor and conventional usage in comparison to the T2(G) route where there is a more balanced representation. The ICT gender split is similar to that of the IT sector, which is to be expected given that the IT sector is a large user of the ICT route.

Table 3.5: Gender split, by usage

| ICT Contractor | ICT Conventional | T2(G) | IT Sector | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 84% | 70% | 51% | 76% | |

| Female | 16% | 30% | 49% | 24% |

Source: Home Office Management Information, ONS.

Certificate of Sponsorship (CoS) data 01 Jan 2019 – 31 Dec 2019, Annual Population Survey 2019.

Notes: Used CoS. CoS is assigned to a migrant by their sponsoring employer and the migrant can then use the certificate number to make a visa application.

We looked at whether it was possible to assess whether the ICT route had a differential impact according to protected characteristics[footnote 10]. From the above analysis, it is clear the ICT route is dominated by males, with a heavy preponderance of Indian nationals. In 2019, the average median salary for females on the ICT route was £50,000, and for males was £47,000. Further analysis shows the median salary of females on the ICT route was higher than males in ages groups below 45, as seen in Table 3.6 below. After this age group, males receive a higher median salary than females. Further work would be required to understand what is driving the wages paid to males and females.