Part 3: supporting service users to get the most out of opioid substitution treatment (OST)

Published 21 July 2021

Applies to England

1. Monitoring, support and review

1.1 The importance of ongoing monitoring

Part 1 of this guidance outlines your role in helping service users who are considering opioid substitution treatment (OST) to make informed choices. It also looked at what information you need to gather to offer service users the most appropriate personalised treatment.

However, service users’ social circumstances, health, and goals are unlikely to stay the same, particularly for those who are in treatment for a long time. It’s important that you talk to service users about their OST throughout treatment, monitoring and reviewing their goals, to adjust the type and intensity of support offered.

You should regularly make service users on long-term prescribing aware of all their treatment options and give them the opportunity to consider alternatives to maintenance treatment (such as detoxification). However, you should not do this in a way that suggests any positive or negative value judgment about any treatment option.

Service users and their families may think that achieving abstinence from all drugs including prescribed opioids is what’s required for treatment to be a ‘success’. But this might not be a realistic short-term goal for many people. Some people will need OST on a long-term basis and possibly even for life. So, it’s important to emphasise that this is not a failure. Many service users on long-term OST fulfil their social and family responsibilities while successfully reducing drug-related risk and progressing their recovery.

Seeing peers who have achieved full abstinence, as well as peers who have made progress in their recovery while maintained on OST medication, can help service users make more informed choices for themselves.

The rest of this section takes a look at the different types of monitoring, support and review that you and your multidisciplinary team (MDT) can offer service users to ensure their treatment is personalised and optimised.

You should consider the service user’s circumstances and progress when deciding how frequent their reviews should be. During each treatment and recovery care plan and strategic review, you should schedule the date of the next review with the service user. However, you should not wait for the next scheduled review if you think there is a reason to have one sooner. Reviews should be done at any point where there is a significant change in the service user’s needs or strengths, and at transition points.

You should consider bringing forward any review of a service user if:

- there are short-term goals to monitor

- the service user has complex or co-occurring health conditions

- the treatment and recovery care plan is not working

- there is a significant change in life circumstances or their treatment and recovery care plan

- the service user requests a review

1.2 Unplanned contact

Drug treatment and recovery workers can provide vital support to service users by phone, in between keywork sessions. This is particularly important if there is cause for concern or an achievement or milestone to affirm.

1.3 Keywork

Keywork involves regular meetings with service users to support their care. The frequency of keywork will depend on the service user’s needs and could range from weekly in early treatment to monthly for those who are stable in treatment. You should continuously monitor care and progress at every one-to-one, structured appointment with the service user. In line with the agreed treatment and recovery care plan, keywork should routinely include:

- providing motivational support and care

- reflecting on and monitoring progress, goals, achievements and challenges

- reviewing any continued drug or alcohol use

- reviewing medicines, dose and collection arrangements

- identifying risks and managing them offering harm reduction and relapse prevention advice and information

- exploring social needs and strengthening the service user’s peer and family support networks

Treatment Outcomes Profile (TOP) reviews prompt you to ask about:

- any ongoing illicit drug or alcohol use and injecting use

- physical health

- psychological health

- quality of life

This review is often done before a strategic review. TOP reviews are an opportunity to reflect on changes since the last TOP. You can ask questions that explore their reasons for the score they gave and what needs to happen to change to improve their score in each section. For example:

I see that you’ve scored 11 on quality of life. Tell me more. Why did you give it 11 and not a 0? What would need to happen for your score to move to a 12?”.

What you learn from one-to-one discussions can inform the next scheduled treatment and recovery care plan review. Based on your discussions about and observations of the service user, it may be necessary to speak to other team members (especially the prescriber) sooner than planned. This will be especially important if you think the treatment and recovery care plan might need to be updated immediately or early. You must also review your caseload through clinical supervision and seek management support as needed.

Issues must be raised in MDT meetings, where decision-making is documented and responsibility is shared among the team, including the prescriber. It is good practice for services to have MDT meetings once a week. If issues are more pressing, it may be necessary to raise them with your manager or the prescriber immediately.

1.4 MDT meetings

MDT meetings allow different professionals to work together to review service users’ treatment and recovery care plans. The MDT takes shared responsibility for making and monitoring documented decisions, such as offering interventions and referring to other agencies. The professionals involved in your MDT meeting will depend on your service staffing model. MDT meetings should ideally be attended by drug treatment and recovery workers, prescribers, nurses and psychologists. MDT meetings are often held weekly with monthly complex case reviews. Service users are discussed based on their assessed level of need.

1.5 Treatment and recovery care plan review

An effective therapeutic relationship between the keyworker and service user is supported by collaborative, person-centred treatment and recovery care planning. You should agree on treatment and recovery goals with the service user (and the actions to address them) and write them in a treatment and recovery care plan. You should monitor the care plan and use it as the basis for ongoing discussion with the service user including during planned reviews.

These reviews can include a TOP review and are typically scheduled every 3 to 6 months. You could use a treatment and recovery care plan review to explore:

- the service user’s previous experiences of OST, drawing on learning from what happened last time they made changes

- what a heroin-free future could be like

- whether the OST medication is still right for the service user and how it fits with their recovery goals

1.6 Strategic review

As well as treatment and recovery care plan reviews, all service users should have more thorough reviews of overall behaviour change, called strategic reviews. These involve the prescriber or a suitably experienced colleague, as well as the drug treatment and recovery worker. Other types of reviews, such as prescriber and MDT reviews, tend to focus on changing a service user’s treatment and recovery care plan in response to emerging risks and issues. Strategic reviews should happen for all service users routinely regardless of risk levels and involve measuring improvements. Strategic reviews should consider:

- whether the current balance of pharmacological, psychosocial and social interventions needs to be adjusted

- what has been achieved and proposing any new direction or treatment and recovery goals identified from this process

- recovery goals and pathways to support service users to move towards a drug-free life

Service users on OST will normally have a strategic review within 3 months (and no later than 6 months) of starting treatment. It will then usually be repeated every 6 to 12 months depending on the service user’s needs and strengths. This frequency can be reduced or increased based on individual needs and strengths. You should still conduct ongoing reviews if the service user is achieving their goals and you do not see any need to change treatment. This is to see whether adjusting the treatment and recovery care plan could increase the benefit even further.

Whether the service user is present at the discussion between the drug treatment and recovery worker and senior colleagues will depend on the circumstances. However, the service user must be involved in updating their progress and in any potential changes to their plan before the review is complete.

1.7 Prescriber review

The prescriber should review service users’ medication (both OST and any other medicines prescribed) regularly. This may happen as part of routine strategic reviews, or it may be a separate review with your MDT is needed. A separate unplanned review is especially necessary if someone is experiencing side effects, breakthrough withdrawal or cravings, or if there are concerns about drug interactions or effects on existing health problems. The prescriber should be involved in all medication reviews. The prescriber may also want to talk to the dispensing pharmacist about whether the service user is adhering to supervised consumption or seek advice from a service lead pharmacist about medicine issues like interactions.

A prescriber review should look at the medicines being prescribed and whether they are achieving the intended effect without side effects. It should aim to tailor what is prescribed, what dose to take and how often to achieve greater benefit if needed.

As these issues are so closely tied into other aspects of a person’s life and recovery, a prescriber review may just be a component of a broader strategic review.

1.8 Drug testing using urine samples

Alongside self-reported drug use and tools such as the TOP, testing for drugs in biological samples is a useful way to monitor illicit drug use and to confirm that service users are sticking to their treatment or are abstinent. However, it does not confirm dependence or tolerance so you should interpret results with care.

Drug testing provides an opportunity to reflect on and explore the service user’s current drug use and their treatment adherence and progress. It is also an opportunity to find out what service users already know about, and enhance their knowledge of, the risks of using drugs or alcohol on top of the prescribed medicine. You can combine this with regularly examining injecting sites, observing the service user for intoxication and assessing their wellbeing and progress.

You can include drug testing once or twice a week as part of an individualised plan, or if you think you need to check whether the service user is adhering to treatment.

You can also use drug testing to support positive changes to treatment. For example, reducing or removing supervised consumption if tests results are positive for the prescribed medicine and negative for other drugs.

1.9 Clinical supervision

Clinical supervision is a structured discussion of a worker’s caseload and other professional issues with an appropriately qualified clinical supervisor. Clinical supervision is typically held monthly and helps workers to learn from their experience, as well as improving their skills and service user care.

2. What to do when a treatment and recovery care plan is not working

Service users might not stop using illicit drugs immediately when they start OST. This can take a long time. It is often more helpful to focus on the improvements service users are making in other parts of their lives, than to focus on their continued drug use. However, drug services are often faced with deciding what to do when a service user is not benefiting from OST. The MDT, including the prescriber, need to make any decisions that involve changes to treatment. The service user’s and drug treatment and recovery worker’s input are key to establishing the best course of action.

2.1 Understanding why a treatment and recovery plan is not working

If a service user appears not to be achieving their goals, it is important that you try to understand why. All people are unique and if you do not re-assess the individual’s goals and circumstances, you may overlook the main barrier to their progress. You should actively engage the service user in this process of re-assessment. You should also discuss with them and your MDT whether you could change their treatment to better meet their current needs and build on their current strengths.

2.2 Introduction to treatment optimisation

When a treatment and recovery care plan is not working, you and the MDT should always consider optimising treatment by increasing the intensity rather than reducing it.

To optimise treatment, you can do the following;

- Ensure medication has been offered or tried at evidence-based optimal dose levels.

- Increase the frequency of pick-ups to prevent the service user from having multiple doses in their possession. This will also increase service user contact with pharmacy staff who may be able to assess or influence their drug use or risk behaviours.

- Reintroduce or increase supervised consumption to ensure the service user is taking the medication. This will also increase service user contact with pharmacy staff.

- Change to another evidence-based substitute medication.

- Increase the intensity of keyworking and support or introduce additional psychosocial interventions. This might include motivational work, more intensive relapse prevention, contingency management or social network approaches (where the necessary training, protocols and supervision are in place to deliver these interventions).

It is vital that you and the MDT risk assess any proposed changes to a service user’s treatment such as changes to dose, collection frequency and supervised dispensing. This risk assessment should consider:

- compliance with prescribed OST medication

- whether the dose is optimised or moving toward it

- abstinence from or significant change in heroin or other illicit drug use (including drug-free urine test results)

- changes in drug-taking behaviours such as injecting

- engagement with other elements of treatment such as attending keyworking and other physical health appointments

- use of alcohol (at low levels or abstinent)

- external factors influencing decision making such as pharmacy location, availability and opening hours, and service user’s support networks

- protective or mitigating factors

- associated risks to children and mitigating measures such as safe storage

The risks to consider when reviewing treatment and recovery care plan changes include:

- illicit drug use

- overdose

- self-harm

- leaving treatment

- safeguarding issues

- relapse in mental illness

2.3 Information and feedback on risks

You must actively engage service users who may be struggling in treatment in a process to identify and address their difficulties and risks. You must inform the service user of the risks and consequences of continuing to use drugs while on OST. Risk management plans and the treatment and recovery care plan (as appropriate) should reflect the risk assessment and any actions to address risks identified.

2.4 Informed drug testing regimens

Below is a scenario and some recommended actions to take if a service user tests positive for illicit opioids while on OST.

You do a drug test with a service user on OST and the sample is positive for illicit opioids. They have not tested positive for illicit opioids in 3 months. In responding to scenarios like this, you should always explore what caused them to use and consider how to optimise both their pharmacological and psychosocial treatment. Depending on previous results, behaviours displayed by the service user, and any risks, you may also decide to:

- talk to them about the result and what might have caused it, exploring the circumstances and how these may be better managed or avoided

- consider changing the frequency of OST instalments so that they are collecting more often from the pharmacy with fewer take-home doses

- consider changing frequency of drug testing

- express concern for their welfare and assure them that any changes made to their treatment, including medication collection arrangements, are to ensure they are receiving the best and safest treatment

- if the result is disputed by the service user, consider taking another sample or sending the existing sample for confirmation testing

- ask to see them again within 1 to 2 weeks and take another urine sample at that appointment

- consider whether reintroducing supervised consumption might be helpful

- consider what else in their treatment might need to be reviewed and optimised

3. How to respond if OST is not working

Common signs that a service user is ambivalent about treatment and changing their behaviour include:

- continuing to use alcohol and illicit drugs on top beyond the induction phase of OST

- missing appointments

- missing medication pick-ups

3.1 How to respond to illicit opioid use on top

It is common for service users to continue to use illicit opioids while on OST. It may be regular and frequent or occasional and infrequent. It may signal that the OST dose is not high enough, or that the social and emotional links with the drug and its users have not been broken. It could also be triggered by external pressures such as peers who use drugs or financial and relationship issues. This section explores the risks associated with and possible responses to continued illicit opioid use on top of OST.

Risks

The risks of illicit opioid use on top of OST include:

- overdose

- blood-borne viruses (BBVs) and other infections (if injecting)

- injection site wounds and deeper damage to veins (if injecting)

- lung damage (if smoking heroin)

- continued offending and being involved in drug using lifestyle

- not engaging with treatment and recovery support

Possible responses

The guiding principle here is that you should aim to optimise treatment interventions for service users who are not benefiting from OST by increasing support rather than reducing it. You should arrange for the service user to have a prescriber review and explore the following pharmacological aspects of their treatment:

- Could a dose increase help to optimise their treatment?

- Are they on the right medication for their current situation? What would the benefits be of switching to a formulation of buprenorphine (or methadone)?

- Are their medication collection arrangements suitable?

You could also review with the service user how to optimise the following psychosocial and harm reduction aspects of their treatment:

- Are they getting the right type and intensity of psychosocial and peer support? Are they being encouraged to explore how continuing to use fits with their goals and values?

- Do they have access to safer injecting advice and injecting equipment supplies?

- Could they benefit from more overdose prevention advice, support or training?

- Are any health problems, including those linked with their continuing drug use, being assessed and treated?

Overdose prevention

Certain drugs depress the central nervous system (CNS), which can slow or stop a person’s breathing. CNS depressants include:

- heroin and other opioids

- alcohol

- benzodiazepines

- gabapentinoids including pregabalin and gabapentin

- z-drugs such as zopiclone and zolpidem

This means that using any combination of these drugs with or without alcohol increases the risk of overdose and death. The effects of these drugs add up, leading people to feel sleepy, slowing their breathing, lowering their blood pressure and potentially causing an overdose.

Dispensing and supervision arrangements

Supervising a service user’s consumption of OST medicines enables the pharmacist to make sure they are taking the dose properly. This has 2 main functions:

- It protects the service user, ensuring that they get the full intended effect.

- It stops diversion to others who may be more at risk of overdose.

It also gives the pharmacist an opportunity to informally assess the service user and to communicate any concerns to the treatment service. Supervision is important in the initial stages of treatment and for service users who are finding it difficult to stick to the treatment programme. However, it can be disruptive to other parts of the service user’s life such as work, education, looking after children and other recovery activities. It’s important that service users’ supervision arrangements are reviewed and that they are able to switch to take-home doses when it is safe to do so.

Psychosocial and recovery support

If a service user is continuing to use illicit drugs or are engaging with treatment less, you should:

- consider more intensive or frequent keyworking sessions

- explore whether there are any physical or mental health issues

- consider contingency management to encourage and motivate the service user not to use (if there is a formal programme running in the service)

- explore with the service user whether they would benefit from additional peer support, mutual aid and opportunities to develop life skills

Prescriber review including dose optimisation

You should regularly discuss the possibility of a dose increase with OST service users who continue to use on top. You can explore the need for this by finding out whether they experience withdrawals before their next dose is due. As we’ve explored already, the aim is to optimise treatment interventions for service users who are not benefiting from them, by increasing support rather than reducing it. This should include a prescribing review to consider whether their dose is optimised.

3.2 How to respond to other illicit drug and alcohol use on top

It is also common for service users to continue to use non-opioid drugs and alcohol on top of OST. People who use opioids (prescribed and illicit) are increasingly using crack cocaine, gabapentinoids and illicit benzodiazepines.

You should continue to ask service users about their drug and alcohol use, not only during TOP reviews but in one-to-one sessions. This is particularly important where changes in behaviour or mood suggest new patterns of use might be emerging. This could include less frequent attendance and signs of intoxication on attendance.

Risks

The main risks associated with using non-opioid drugs and alcohol on top of OST are outlined below.

Risks associated with using alcohol, benzodiazepines, gabapentinoids and z-drugs on top of OST include:

- increased risk of overdose from drug interactions

- liver function deteriorating (especially in people with hepatitis C)

- blackouts, memory loss and assaults

Risks associated with using cocaine (crack and powder) include:

- BBVs and other infections, and injection site wounds (if injecting)

- irregular or risky patterns of drug use (which can increase risk of overdose)

- financial pressures and risk of acquisitive crime

- psychological distress

Possible responses

The possible responses to continued use of non-opioid drugs and alcohol on top of OST that you should consider with service users and your MDT are outlined below.

If a service user continues to use non-opioid drugs or alcohol on top of OST, you should consider the following with your MDT:

- Are they getting the right type and intensity of psychosocial and peer support? You could consider increasing the frequency of their keyworking.

- Has their level of dependence on these drugs or alcohol been assessed?

- Could they benefit from a prescriber review to assess evidence of opioid tolerance and opioid intoxication?

- Have they reached adequate stability on their current dose of OST?

- Is there a need for daily supervised consumption of OST and what changes would trigger a review of these dispensing arrangements?

- Could they benefit from substance focused keyworking support such as contingency management for stimulants?

- Could they benefit from information and advice on overdose risk and reducing it?

- Have you offered access to safer injecting advice and supplies?

- Could they benefit from a review for any co-occurring mental health conditions?

To monitor and treat alcohol dependence and use specifically, you should consider the following with your MDT:

- Have you screened the service user using a validated alcohol screening test such as the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT)? The AUDIT will help you to identify health risk from alcohol consumption.

- Would breathalyser testing be useful in monitoring progress? This could be used to confirm that there is no evidence of recent alcohol use.

- Could they benefit from alcohol detoxification?

3.3 How to respond to missed appointments and medication pick-ups

Where service users are frequently missing appointments or medication pick-ups, this can show that their treatment is not optimised. Missing medication pick-ups can increase the risk of overdose. In both situations, you should work with your MDT to review and optimise the service user’s treatment.

Missing appointments

The scenarios that might cause service users to frequently miss appointments and how you can respond are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1: possible causes of and responses to missed appointments

| Cause | Responses |

|---|---|

| Service user prefers a different appointment time or commitments such as work or family mean that appointment times are not suitable. | Arrange appointments at alternative times (such as in the evening), locations or a mix of face-to-face and digital support. |

| Difficulty remembering the appointments. | Send text reminders or call on the morning of the appointment. |

| Not able to cover travel expenses. | Subject to availability, offer bus passes, tickets, or other travel reimbursement. Offer a mix of face-to-face and digital support. |

| Feeling ambivalent about treatment or has other priorities. | Where the appropriate protocols are in place, you can offer incentives to encourage attendance (contingency management). Peer mentors can offer practical and motivational support (such as accompanying service users to appointments) to encourage attendance. Explore why they are ambivalent. |

| They are stable on their medication and do not need or want the level of support currently being offered. | In some instances, it may be appropriate to agree to less frequent face-to-face contact for a period of time. |

| Continued illicit drug or alcohol use, lapse or relapse. | Review and optimise their treatment, including medication dose, psychosocial support, harm reduction and healthcare. |

| Changing life circumstances such as bereavement, mental health struggles, job loss, physical illness, and domestic abuse. | Phone contact can sometimes quickly reveal a current problem that you can offer practical and emotional support with. |

| Service user does not find the keyworker or keywork sessions helpful. | Treatment and recovery care plan review by keyworker and MDT. Try agenda setting (see below for how). Consider changing the keyworker. |

Where a service user is frequently not attending, services and workers should reflect on what they are offering in sessions and treatment generally.

It is common practice to check in with service users about whether there is anything new or particularly important to them that they’d like to cover in a session. It can be easy for you to forget to review goals in the next or future sessions. This can mean that issues may remain unresolved and progress made can go unacknowledged. Setting an agenda and reviewing goals is associated with good outcomes.

When reviewing the treatment you offer, you could consider the following with your manager:

- What are service users turning up to (or not)?

- How inviting was the appointment?

- How is the agenda set for sessions and who sets it?

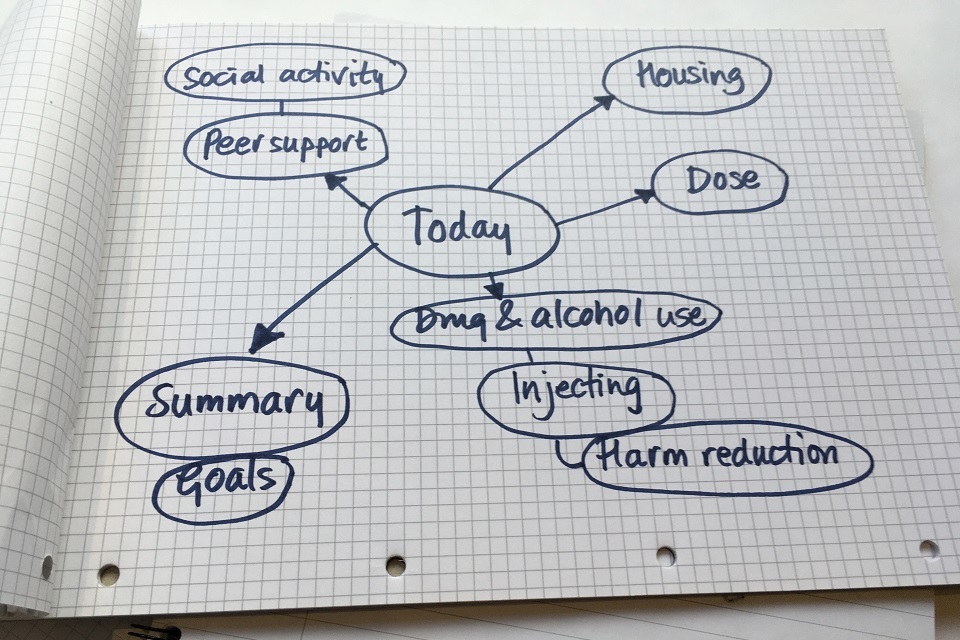

It is good practice to agree on an agenda for each session with the service user. You can create an agenda using free mapping. Mapping is a simple way to present verbal information in the form of a diagram, which has been shown to have positive benefits for keyworking specifically with OST service users. Free maps are jointly produced and spontaneously drawn freehand. Using a free map agenda means that service users can include any presenting concerns and you can be sure to review more routine subjects like dose and illicit use on top.

Figure 1 shows an example free map agenda drawn by a key worker for an OST keywork session. In the centre, it says ‘Today’ inside a circle. From this circle, arrows lead to:

- peer support and social activity

- housing

- dose

- drug and alcohol use, injecting and harm reduction

- summary and goals

Figure 1: example of a free map agenda for an OST keywork session

Whatever the reason for a service user on OST missing appointments, it is your role to immediately try to re-engage them. You should also arrange a review of their current situation and medication involving you, the service user and the prescriber. Through this review, a new treatment and recovery care plan should be agreed. Where available as part of your local service offer, peer workers or volunteers can also proactively re-engage service users, offering practical and emotional support and advocacy, where necessary.

Missing medication pick-ups

If a service user has not taken their regular prescribed dose of opioids, their tolerance to the drug could have reduced. This increases their risk of overdose if they then take their usual dose of medication. This is less of a risk with buprenorphine than with methadone. Pharmacists should tell drug services whenever they have concerns, for example, concerns relating to missed pick-ups or the service user’s presentation (such as intoxication or a clear deterioration in their health and wellbeing). Below we have outlined how you could respond to any missed medication pick-ups, missed pick-ups of 1 or 2 days and those of 3 days or more.

If a service user has missed any pick-ups you should:

- ask them whether pick-up arrangements align with their needs and consider making adjustments, balancing the service user’s needs with risks to them and others

- assess their engagement with their treatment and recovery care plan and whether it would be useful to develop a new plan

If a service user has missed pick-ups for up to 2 days in a row you should:

- try to contact the service user to find out what the problem is

- arrange an urgent assessment for service users if there is a particular concern

If a service user has missed pick-ups for 3 days or more, you should follow the process below:

- The pharmacist should ask the prescribing service what action to take.

- A pharmacist should not dispense the OST medication unless the prescribing service has confirmed that it is appropriate to do so. The service should base this on what they know about the service user’s circumstances (including any new information from the pharmacist), and on their clinical judgement.

- The prescribing service may advise the pharmacist to ask the service user to contact the prescribing service for urgent clinical review.

- Following clinical assessment, it may be appropriate to reduce the dose and then titrate back up to an appropriate maintenance dose.

You must make every effort to limit the potentially harmful impact of being without OST medication until a review can happen and a new prescription is established.

4. When to consider switching OST medication

This section outlines some common scenarios that might prompt you, a service user or prescriber to consider switching the service user’s OST medication.

4.1 Common scenarios for switching OST medications

There are many reasons a service user, drug treatment and recovery worker or prescriber might consider changing a service user’s OST medication. Below are some common scenarios.

Medication causing unpleasant side effects

The OST medication might cause unpleasant side effects, for example, some service users find methadone too sedating or experience nausea.

Medication does not appear to be working

The medication might not be working for the service user’s recovery if they are still using illicit drugs or drinking excessively.

Poor physical health

A physical health condition might develop, be identified or worsen that can make using the OST medication too risky or clinically inadvisable. These issues may be more pronounced as people get older. Specifically, you should be aware if any service user has respiratory or cardiac problems.

Respiratory issues or disease

Lung disease is a major issue for people who use opioids as both affect breathing ability and make overdose death more likely. Older people and people who smoke tobacco or other drugs (currently or previously) are at increased risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), which is a risk factor for pneumonia. Other lung health issues may include emphysema, lung cancer and asthma. Symptoms to look for include:

- persistent or continuous cough or sputum production

- coughing up blood

- breathlessness on minor exertion

Methadone has a respiratory depressant effect that increases as the dose increases, so, if a service user has significant respiratory disease then you or the prescriber may decide to switch to buprenorphine. Buprenorphine also depresses respiration, but the effect stops increasing past a certain dose. This means that buprenorphine has a much smaller effect on respiration than methadone.

Cardiac issues

Opioids including methadone can affect electrical signals in the heart. This can result in a cardiac condition known as prolonged QTc interval, which increases the risk of sudden cardiac death. It is thought to be dose-related (higher methadone doses increase risk, particularly over 100mg) but several factors, including age and other medicines, may also increase the risk. The service user’s risk can be assessed by having an electrocardiogram (a trace of the heart’s electrical activity). If prolonged QTc interval is identified it can usually be addressed by reducing the methadone dose. The other option is switching to buprenorphine which does not cause prolonged QTc interval.

A co-occurring mental health condition

A mental health condition has developed, been identified or worsened, and might make adhering to treatment difficult, or there is a possible interaction with medication such as antidepressants. Research shows that 75% of people being treated for drug use in the community experience mental health problems. Most of these are common mental health problems such as anxiety and depression. A much smaller proportion have a severe and long-term illness such as psychosis, but this proportion is higher than in the general population.

Evidence tells us that people with co-occurring conditions are more likely to be admitted to hospital and have a higher risk of other health problems and early death. People with co-occurring conditions experience barriers to engaging in both mental health and drug and alcohol services. Public Health England has published guidance on meeting the needs of people with co-occurring drug and alcohol, and mental health conditions. This guidance states that health, social care and other frontline services should respond collaboratively, effectively and flexibly to prevent people being excluded. It sets out tangible principles for how services should work, notably that it’s ‘everyone’s job’ and there should be ‘no wrong door’.

Depression, anxiety and other mental health conditions can make it more difficult for people to get into and stay in drug treatment generally and OST specifically. For OST, these conditions might mean that service users do not turn up to appointments or pick up medication.

The signs of depression you might notice are:

- low mood

- poor concentration

- loss of energy

- lack of enjoyment

The signs of anxiety you might notice are:

- worry

- irritability

- poor sleep

- uneasiness

- changes in behaviour

Interaction with other medications

A service user is taking another medicine that may interact with the OST medication. These include, but are not limited to:

- analgesics

- antidepressants

- anxiolytics

- hypnotics

- antibiotics

- alcohol

- smoking dependence treatment medicines

You can find more information on drug interactions in Annex 5 of the drug misuse and dependence clinical guidelines.

4.2 Responses

Where one of the above scenarios leads you to think that switching medication might be necessary or advisable, it is your responsibility to discuss this with the service user and your MDT including the prescriber. Below are some scenarios where you might consider switching a service user’s OST medication, and tips on how to respond to these scenarios.

Co-existing physical health problems such as respiratory and cardiac ill health

- Identify signs of co-existing physical health problems.

- Write down what the service user can tell you about how the problem has developed to better understand it.

- If it could be a significant physical health problem, discuss with MDT.

- Advocate for the service user and support them to access physical healthcare.

- Arrange a review with the prescriber.

See section 5 below for more information on responding to tobacco smoking and respiratory issues in drug treatment.

Side effects

- Identify signs, and listen carefully for mentions, of potential side effects such as difficulty breathing.

- Write down what the service user can tell you about the side effects to understand the problem.

- Arrange a review with the prescriber.

Illicit drug and alcohol use on top

- Review and optimise the treatment including medication dose, psychosocial support, harm reduction and healthcare.

- Assess whether use of other substances is harmful or dependent.

- Discuss with MDT.

Co-occurring mental health conditions

- Identify signs of co-occurring mental health conditions. The Generalised Anxiety Disorder Assessment (GAD-7) will help you to screen for the presence and severity of anxiety. The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) will help you to screen for the presence and severity of depression. The results of these assessment tools need to be carefully considered as sometimes symptoms of drug use such as intoxication or withdrawal can mimic the effects of depression and anxiety.

- Write down what the service user can tell you about how the problem has developed to better understand it.

- If a significant mental health condition seems possible, discuss with MDT.

- Bring your findings to the MDT, including the service prescriber and your service user’s GP, and discuss what mental health interventions are available. This might include the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) programme or mental health team.

Interaction with other medications

- Ask the prescriber to review the OST prescription if there have been any changes in other medication reports.

- Check the GP or another prescriber is aware that the person is on OST and that this can have interactions with what they are prescribing.

4.3 What service users need to know

You play a vital role in reassuring service users that the service is experienced in switching people between medications, managing the risks and keeping them as comfortable as possible throughout.

Service users also need information and advice on what they can expect before and during switching from one OST medication to another.

Methadone to buprenorphine switch

When buprenorphine is first given to an opioid dependent person using opioid full-agonist drugs such as heroin or methadone, they can experience withdrawal signs and symptoms (see part 1 of this guidance for more information about withdrawal symptoms).

This process is known as ‘precipitated withdrawal’. It happens when an opioid dependent person is first given buprenorphine because the buprenorphine (a partial agonist) ‘bumps’ the full agonist (heroin or methadone) off the brain’s opioid receptors causing withdrawals. It can be very unpleasant and may deter service users from continuing to participate in treatment.

To prevent precipitated withdrawal, the methadone dose should usually be below 30mg a day and the person should not take any methadone for a day or so before buprenorphine is given at a very small test dose. If the service user tolerates this dose, then the buprenorphine can be gradually increased. Although these decisions will be made by the prescriber, it is very important that you explain the process to the service user so they are aware of what is happening and why.

Buprenorphine to methadone switch

This is a less common switch but generally an easier one. There is no risk of precipitated withdrawal as the service user is being moved from a partial agonist (buprenorphine) to a full agonist (methadone). This switch still needs to be done with care and the methadone dose titrated with caution.

5. Tobacco smoking and respiratory function

In 2019 to 2020, 70% of people who entered drug treatment using opioids were tobacco smokers. Figure 2 shows the smoking rates among men and women starting drug and alcohol treatment in the same period, split into the 4 drug categories. These are opiate, non-opiate only, non-opiate and alcohol and alcohol only. Figure 2 also shows the smoking rate in the general population of England for comparison. The highest smoking rates were among people who use opiates (70.3% for men and 69.9% for women). The lowest smoking rates were in the alcohol group (44.5% for men and 42.9% for women) but overall, rates were much higher than the general population (17.3% for men and 13.8% for women).

Figure 2: smoking rates at the start of treatment in 2019 to 2020

Despite the high levels of smoking, around 3% of smokers starting treatment were offered stop smoking support. Tobacco smoking causes lots of different diseases and 1 in 2 long term smokers will die as a result of their tobacco use. This is mainly through developing cardiovascular diseases and lung diseases (COPD, lung cancer and poorly controlled asthma). Some people in drug treatment will have been smoking drugs that can also damage their lungs (such as crack cocaine, heroin and cannabis). Lung disease can reduce lung function, which may contribute to some deaths from opioid overdose. This will be even more likely if the person uses CNS depressant drugs such as benzodiazepines, gabapentinoids and excess alcohol.

Most people in treatment say they want to quit smoking. However, not enough people are offered adequate support to do so. Many drug treatment and recovery workers wrongly think that smoking is of secondary importance to drug use and that quitting will cause unnecessary discomfort particularly for those with poor mental health. In fact, quitting smoking improves both physical and mental health, even in the short term. Working on a service user’s drug use and smoking together improves outcomes as both use the same kinds of psychosocial interventions such as support for coping with cravings and preventing relapse. Stop smoking support provided during drug and alcohol treatment has been associated with a 25% increased likelihood of long-term abstinence from alcohol and drugs.

You can support service users to stop smoking by providing very brief advice (VBA). VBA consists of 3 main principles: ask, advise and act.

- Ask if they currently smoke tobacco and record their smoking status.

- Advise on the most effective methods of quitting, which are a combination of behavioural support along with stop smoking medicines or regulated nicotine replacement products including e-cigarettes. It’s important that service users know to use regulated e-liquids and never risk vaping homemade or illicit e-liquids or adding substances.

- Act on the service user’s response and provide access to these interventions. Swift and easy access to behavioural support at a place and time that is convenient, alongside free (prescriptions or vouchers) or relatively inexpensive products to support quitting will increase the likelihood of success.

You can provide VBA in as little as 30 seconds. For example, you can ask something like:

Did you know that the best way of stopping smoking for good is with a combination of medication and specialist support?

You can follow up concerns about respiratory health by:

- identifying any indication of cardiovascular or respiratory disease (this may be through the history of symptoms, observation or physical examination, or lung function testing)

- supporting attendance for more detailed physical assessment and investigation by the service user’s GP (or subsequently by a suitable specialist) if indicated

- supporting continued engagement with treatment services for respiratory problems from a GP or specialist respiratory health services