Misuse of illicit drugs and medicines: applying All Our Health

Updated 23 February 2022

The Public Health England team leading this policy transitioned into the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (OHID) on 1 October 2021.

Introduction

This ‘All Our Health’ misuse of illicit drugs and medicines guidance will help health and care professionals to:

- identify, prevent or reduce drug-related harm

- identify resources and services available in your area that can help people with drug misuse

This guidance also recommends important actions that managers and staff holding strategic roles can take.

Access the misuse of illicit drugs and medicines e-learning session

An interactive e-learning version of this topic is now available to use.

The Office of Health Improvement and Disparities (OHID) and Health Education England’s e-Learning for Healthcare have developed this content to increase the confidence and skills of health and care professionals, to embed prevention in their day-to-day practice.

Completing this session will count towards your continued professional development.

Ask about illicit drug and medicine misuse in your professional practice

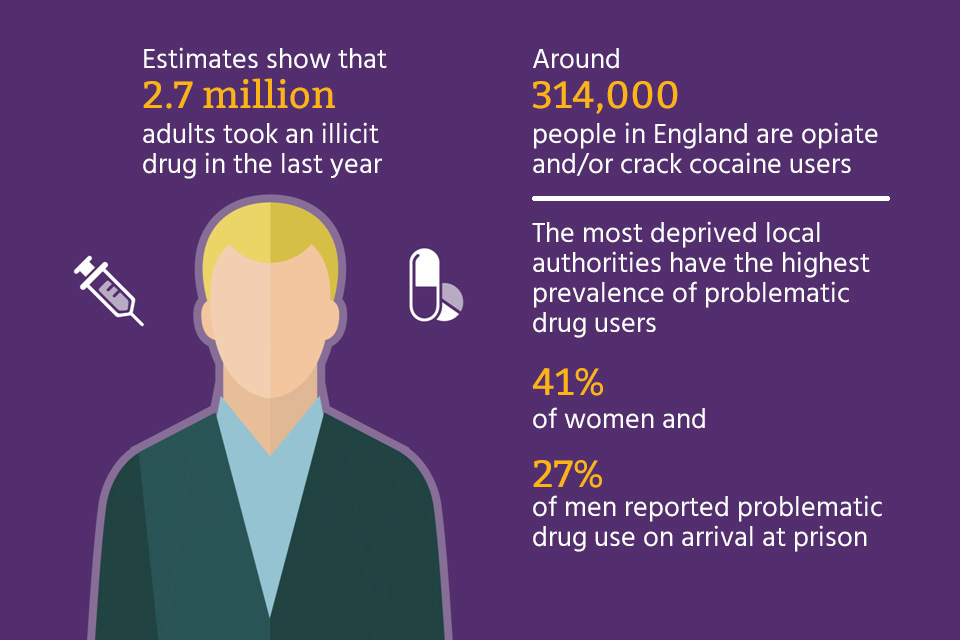

A 2017 NHS Digital report on statistics around drugs misuse showed that, in England and Wales, 1 in 12 adults (16 to 59 years old) used an illicit drug in the previous year. This is approximately 2.7 million individuals. Around 1 in 3 adults reported using an illicit drug at some point during their lifetime.

Fortunately, the number of people with serious drug problems is small, although these problems can have a big impact on individuals, their families and the wider community.

The drugs causing most problems include heroin and crack cocaine, and estimates of prevalence suggest there are approximately 314,000 people using these drugs in England (based on 2016 to 2017 data). The Marmot Review of health inequalities (2010) states that the most deprived local authorities have the highest prevalence of problematic drug use. A report published by HM Inspectorate of Prisons in 2015 on patterns of substance misuse in adult prisons showed that among those arriving at prison, 41% of women and 27% of men reported problematic drug use.

New patterns of drug misuse have emerged over the last decade and new psychoactive substances, image and performance enhancing drugs and misuse of medication are particular areas of concern.

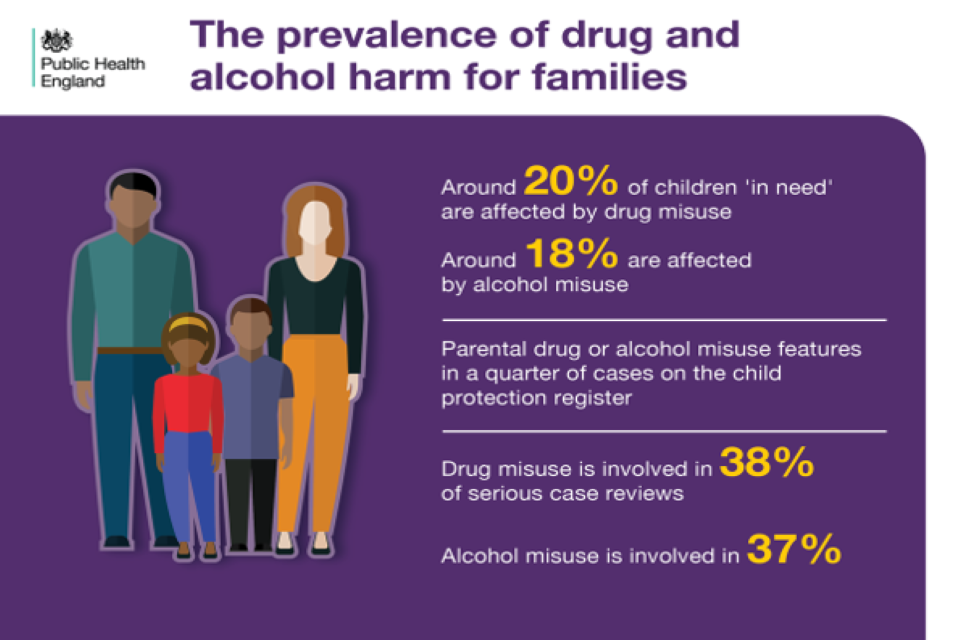

Drug misuse can also affect children and families. Statistics on children ‘in need’ in 2016 to 2017 showed that around 20% of these children are affected by drug misuse while around 18% are affected by alcohol misuse. An inquiry into hidden harm carried out by the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs in 2011 found that parental drug or alcohol misuse featured in a quarter of cases on the child protection register.

A study analysing serious case reviews between 2011 and 2014 showed that drug misuse was involved in 38% of serious case reviews, while alcohol was involved in 37%.

Core principles for healthcare professionals

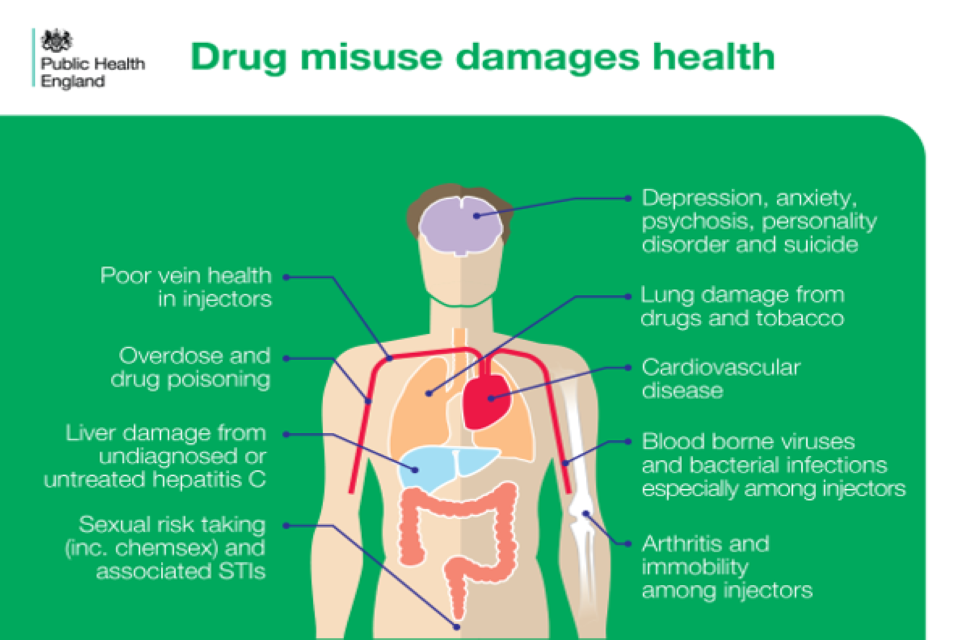

Drug use can cause a range of health-related problems, including:

- mental health problems such as anxiety, depression, psychosis, personality disorder and suicide

- lung damage

- cardiovascular disease

- blood-borne viruses

- arthritis and immobility among injectors

- poor vein health in injectors

- liver damage from undiagnosed and untreated hepatitis C virus (HCV)

- sexual risk taking and associated sexually transmitted infections (STIs)

- overdose and drug poisoning

Because of this, people experiencing drug-related harms might seek help from a wide range of health and care professionals, including acute medical, primary care and psychiatric services.

Drug use might not be the main problem that a person is seeking help for, or even immediately obvious as a potential contributing factor to their ill health.

Making every contact count (MECC) is an approach to behaviour change that uses the millions of day-to-day interactions that front-line services have with people, to support them in making positive changes to their physical and mental health and wellbeing.

MECC recommends using every appropriate opportunity to ask people about their lifestyle choices and the impact these may have. It’s important that you are able to ask individuals sensitively whether they use drugs, and offer assistance to help them make any changes they want to make, either directly or by referring them to specialist services.

It is important to remember that specialist drug treatment works. It might be hard for people to give up long-term dependent drug use, but it’s not impossible. Last year, specialist services discharged 58,718 service users from drug treatment free from the drugs they were previously dependent on. This represents almost half (48%) of all services users leaving treatment.

We also know that every £1 spent on drug treatment is associated with a social and economic return of £4. This includes reductions in health and social care and offending costs, and improvements in quality-adjusted life years (QALYs). This increases to a £21 benefit for each person over a 10 year period.

Taking action

If you’re a front-line health and care professional

Asking a patient about their drug use

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) clinical guideline 64 recommends that health and social care professionals routinely assess whether people in groups at risk are vulnerable to drug misuse.

Routine drug screening is recommended in settings where drug misuse is common such as mental health and criminal justice services. Health and care professionals could include this in their standard assessment protocols.

In more general healthcare settings, NICE recommends asking about drugs if the patient has problems that suggest they are using drugs, such as chest pain in a young person, acute psychosis, and mood and sleep disorders.

NICE also advises that health and care professionals are open to the possibility that drug use may be a factor in their patient’s health or linked to other social issues, such as debt or housing problems.

You can use the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Tool – Lite (ASSIST-Lite) to identify alcohol, drug and tobacco smoking-related risk and to deliver appropriate interventions to help the service user reduce these risks. There is one version of the ASSIST-Lite tool for use in mental health services and one for use in other health and social care services. If your patient is using drugs, make sure you also ask:

- how they’re taken (orally, smoked or inhaled, by injection)

- how often

- in what quantity

This information and their screening score will help you to deliver appropriate interventions.

Drug use is a sensitive issue and asking about it can raise anxieties for both patients and health and care professionals. Common concerns expressed by health and care professionals include a fear that raising the topic might interfere in building a trusting relationship with their patient, that it might expose their lack of in-depth knowledge about drugs or that they are raising an issue that is just not relevant.

You may also have your own attitudes and beliefs about drugs and the people who use them and this can sometimes influence clinical management. People with drug problems can be unfairly excluded from services. However, the NHS website is clear that people who receive treatment for drug addiction are entitled to NHS care in the same way as anyone else who has a health problem.

Asking patients about their drug use can produce a variety of responses and so health and care professionals need to approach this sensitively. Many drugs are illegal and people might be understandably reluctant to talk about using them. They may also be unwilling to consider whether their drug use has any impact on their current health problems or conditions. This might be because they genuinely believe it does not (which could be true) or because they have become practised at defending themselves against criticism.

However, patients might expect health and care professionals to ask about their drug use in particular settings or when drug use is the likely cause of a particular condition, for example admission to A&E from a nightclub.

Asking about drug use can occasionally provoke a hostile response and in these circumstances it is probably better to move the conversation on and not pursue the issue.

The best way to get an honest answer is to ask a simple, straightforward question. How best to ask the question will ultimately depend on your role and relationship with the patient, the setting in which the conversation is taking place, or the patient’s symptoms.

For example, in a GP consultation, after asking about smoking and drinking, a doctor might ask the patient if they use any other drugs, or whether they smoke anything other than tobacco. In a sexual health clinic, a health professional could routinely ask patients about when they last had sober sex, and questions about what drugs they have used could flow naturally from their answer.

Good practice suggests that you develop a form of asking that is neutral in tone (courteous, concerned, professional, and non-judgemental) while also relevant to the patient’s current health problem or condition.

Offering help to a patient for their drug use

If asking them about drugs leads to your patient telling you that they do use drugs, then it follows that you should offer an appropriate response. What is appropriate will again depend on:

- your role and area of specialty

- the patient’s presenting issue or condition

- the need to respond to an acute crisis or to manage risk (to the patient or others)

- your knowledge and the availability of resources (such as information or local services)

The ASSIST-Lite screening tool advises professionals on the appropriate interventions to help the service user reduce their risk. In mental health settings, mental health professionals can deliver some treatment interventions in-house. This is reflected in the pathways laid out in the version of the ASSIST-Lite tool for use in mental health settings. For people identified as ‘increasing risk’, and some identified as ‘higher risk’, the tool indicates that brief advice should be given by the health and social care professional who completed the screening tool.

Help can take a variety of forms. Choose an approach that is consistent with your role. Ideally, this would be part of an agreed service protocol or standard and subject to an appropriate level of governance and review. At a minimum, it’s good practice to offer some type of help in the form of information, brief advice, follow-up review or onward referral.

You can give help relatively briefly without the need for specialist knowledge.

As with asking, any offer of help should be neutral in tone and you can present it as a routine response to a common set of occurring issues.

Offering information and advice to a patient about their drug use

Sometimes, help could simply be suggesting that your patient seeks more information about the drugs they are using. This can help them make a more informed decision about their drug use as well as help them take action to reduce any harms they are suffering.

What information you direct the patient to will depend on their circumstances and the resources available. Examples of resources include information leaflets, helplines, online screening tools or other web-based resources or apps.

Guidance on using the ASSIST-Lite includes an overview of how to deliver brief advice on drugs using the FRAMES approach. Brief advice is typically a short, informal but structured conversation supported by written information such as leaflets. Suitable sources of information include:

- the cannabis health check-up tool, which can help you to structure cannabis brief advice

- the FRANK website and helpline, which offer information and confidential advice about drugs and drug use and where to find help locally

- the NHS drug addiction: getting help website, which provides useful material on what drug treatment involves and what to expect from your first appointment

Referring a patient to a specialist service

If you feel the patient’s drug use is causing them harm, and requires specialist intervention, try to make a connection between their drug use and their health problems and suggest a referral. This could be a direct referral (for example “we have a drugs counsellor here once a week – how would you feel about booking an appointment to see them?”) or it could involve finding your patient’s local specialist service and referring them.

You can find details of your patient’s nearest service by going to the FRANK website and searching for their postcode. You could do this together, as a way of showing them the website, which could encourage your patient to visit the site again later. Most drug services accept self-referrals and offer drop-in assessment sessions, where you do not need an appointment. Waiting times to access drug treatment are usually short.

Mutual aid services such as Narcotics Anonymous, Cocaine Anonymous and Self-management and recovery training (SMART) can also offer support to people who want to address their drug use. Even when someone is in a drug treatment programme, mutual aid can help them connect with a community of people in recovery.

Advice on reducing or stopping a patient’s drug use

In some circumstances it may be appropriate to advise a patient to reduce, stop or minimise the harm from their drug use.

The nature of this advice will depend on:

- your level of knowledge about the drugs used

- the risks associated with stopping use

- the extent and frequency of your patient’s drug use

- the impact of drug use on the presenting condition

Clinical guidelines do not recommend advising a patient to stop using drugs altogether if there are concerns that they are highly dependent. In these circumstances, you should seek specialist advice from a drug service.

Examples of how you might advise a patient include:

- advising a weekend user of club drugs like ecstasy that this can impact on mental wellbeing during the week and recommend they take a break

- using the cannabis health check-up tool to advise a daily cannabis user on the negative effect of cannabis on memory and that they should avoid it when studying for an exam

During routine contacts with patients and when the opportunity arises, you should provide information and advice about reducing exposure to blood-borne viruses (BBVs) to any patient who reports injecting drug use. This should include advice on reducing sexual and injection risk behaviours. You should also consider offering to arrange testing for BBVs.

If a patient is actively asking for advice or is receptive to talking further then you should encourage it. This is a solid basis for setting up more focused counselling or making a referral to a specialist agency. You might also tell them to talk to someone they feel they could trust, to support them.

Review a patient’s drug use at each session

If you remain in contact with a patient who has reported using drugs, then it will be important to review this each time you see them. Ask again about their drug use, what they are doing about it, and whether they would like any further or different help. Re-emphasise possible connections between their current condition and their drug use, as this might help motivate them to reflect on the impact of their drug use.

If a patient declines help, then unless there are other issues such as mental health problems (perhaps requiring a mental health act assessment) or if there are children involved, then that is their choice. However, you can offer the option of returning for further help in the future or letting them know where they can get help if they change their mind. You could say something like:

I understand you don’t want to talk about your drug use today but how would you feel if I ask you about how things are next time we meet?

The offer of help should be proportionate and in line with your role and expertise. Follow local guidelines where they exist.

If you’re a team leader or manager

Team leaders and managers can take various actions to help staff engage with patients who have drug problems, such as:

- promoting the principles of making every contact count – discuss with your team whether it would be useful to ask the patients you work with whether they use drugs

- training staff in using the ASSIST-Lite screening tool and delivering drug brief advice

- developing service protocols on drug screening, information and brief advice

- making sure there are appropriate supervision arrangements in place to allow staff to discuss difficult cases and reflect on best practice

- identifying local substance misuse services and mutual aid groups – have a handy list available

If you’re a senior or strategic leader

Senior and strategic leaders can also take action to encourage all their staff to engage with drug misuse, such as:

- making contact with your regional UK Health Security agency (UKHSA) local health protection office for tailored support and advice

- promoting making every contact count across your organisation

- making sure education and training matches the expertise required in a particular setting

Understanding local needs

The main measures of the impact of drug misuse on a population are Public Health Outcomes Framework indicators 2.5i (successful completion of drug treatment – opiate users) and 2.5ii (successful completion of drug treatment – non-opiate users).

The public health dashboard provides local information on:

- rates of opiate users not in treatment (known as ‘unmet need’)

- waiting times to start drug treatment

- successful completion of drug treatment

- deaths during treatment

Opiate and crack cocaine use estimates show the prevalence of opiate and crack misuse issues among national and local populations.

The numbers of people in drug treatment are provided by the National Drug Treatment Monitoring System.

Annual commissioning support guidance outlines important principles that local areas can consider when developing their plans for drugs prevention, treatment and recovery.

Further reading, resources and good practice examples

Advice for patients and the public

You can find out everything you want to know about drugs, and where to get help on the FRANK website.

The cannabis health check-up tool outlines the benefits of cutting down or quitting cannabis, tips for reducing cannabis use, and signposts to sources of advice, support and treatment. It also provides space for people to set their own goals to reduce cannabis use and risk. The tool is designed to be used by health and social care professionals with people whose cannabis use is identified as ‘increasing’ or ‘higher risk’ by the ASSIST-Lite screening tool.

The NHS website also provides useful information on where to get support for drug-related problems and what treatments are available.

Professional resources and tools

Alcohol and drug prevention, treatment and recovery: why invest? provides information for commissioners and substance misuse service providers to help make the case for investing in drug and alcohol treatment and interventions.

Making every contact count: an implementation guide and toolkit.

NICE’s psychosocial interventions guideline CG51 is about using psychosocial interventions to treat adults and young people over 16 who have a problem with or are dependent on drugs.

NICE’s drug misuse prevention guideline NG64 includes targeted interventions to prevent or delay harmful use of drugs (illegal drugs, new psychoactive substances and prescription-only medicines) among those who are already experimenting or using drugs occasionally.

The cannabis health check-up tool can help to structure cannabis brief advice.

Drug misuse and dependence: UK guidelines on clinical management provides guidance on how clinicians should treat people with drug misuse and drug dependence problems.

NEPTUNE provides guidance to improve clinical practice in the management of harms resulting from the use of club drugs and new psychoactive substances.

Opioids Aware is a resource developed by the Faculty of Pain Medicine to support the prescribing of opioid medicines for pain.

Good practice examples

Emergency department

At St Thomas’ Hospital in London, clinical toxicologists on their ward rounds have conversations about drugs, alcohol and smoking with patients, exploring how these can relate to their condition. Clinicians take the time to discuss a patient’s current thinking about their drug use and whether they think it has become problematic.

Where a patient is not keen to talk about their drug use at the time, clinicians offer outpatient appointments with one of the clinical toxicologists at a later date. Clinicians on the ward, in the emergency and the outpatient departments can offer harm reduction advice, including information about local needle and syringe exchange programmes and where relevant signposting to specialist drug treatment services.

In addition, all patients attending the emergency department who have a blood test done also have HIV testing unless they specifically opt out.

Approved premises

Haworth House in Blackburn offers up to 12 weeks of accommodation and support to men leaving prison who are high risk and so remain under the supervision of the National Probation Service. Hostel staff provide supervision and rehabilitative support.

Support for people moving into the hostel begins well before release, through ‘pre-engagement’ appointments by phone or on Skype. In these sessions, hostel staff work to build a relationship with incoming residents, taking an ‘asset-based approach’, which means focusing on what people are interested in and good at (their assets). These early conversations are also an opportunity to talk about people’s current and former drug use, including any substitute medication they might be on, and begin to explore how they feel about any current drug use and what changes they would like to make to it.

Following pre-engagement work and induction into the hostel, staff offer appropriate harm reduction advice and work with residents to link them into various in-house groups, including peer-led, mutual aid and wellbeing sessions. They can also be referred to primary care, specialist drug treatment services, and a range of partner services offering recovery-focused support.

An infographic outlining the Haworth House service model is available as part of a Probation Healthcare Commissioning Toolkit developed by the University of Lincoln and Royal Holloway University.

Sexual health clinic

The John Hunter NHS sexual health clinic in London offers services for all aspects of sexual health, including testing and treatment for all sexually transmitted infections, contraception, pregnancy testing, vaccinations, partner notification, health promotion and advice on safer sex, harm reduction and risk reduction interventions.

Doctors and nurses running clinics routinely ask people about their drug use, focusing on particular high-risk groups, including young people, students, men who have sex with men (MSM), people who inject drugs and clubbers.

Clinicians ask patients if they use drugs, how they use them and in what context and whether they or someone they know has concerns that they might be at risk of harm due to their drug use. Depending on what the patient says, clinicians will ask further questions to identify any drug-related risk-taking. For example, asking an opioid user if they are injecting drugs or asking MSM about the relationship between their drug use and sex.

Where a person’s drug use is risky, the sexual health clinician starts a discussion about the risks and provides harm reduction information. Where someone could benefit from further support, clinicians offer follow-up appointments with a health advisor who is trained in motivational interviewing, for motivational sessions aiming to reduce drug use and related risks. And where appropriate, clinicians refer patients to an in-house specialist club drug clinic or local drug treatment services.