Country policy and information note: opposition to the government in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI), Iraq, July 2023 (accessible)

Updated 5 November 2025

Version 3.0, July 2023

Executive summary

Updated on 29 June 2023

The Kurds are an ethnic group indigenous to the mountainous region straddling the borders of Turkey, Iraq, Syria, Iran and Armenia. In Iraq, the Kurds make up the majority group in the autonomous Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI). The KRI has its own distinct government, known as the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG). The 111-seat Kurdish parliament is elected through closed party-list proportional representation in a single district, with members serving four-year terms. Since the 2018 elections, the governing Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) has maintained a plurality of seats, followed by the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) and the Gorran movement. At the time of writing, the current president of the KRG is Nechirvan Barzani and the current prime minister is Masrour Barzani, both of whom are from the KDP.

In October 2020 widespread protests took place across the KRI in response to pension reform, unpaid teacher and civil servant wages, government corruption, and a lack of improvements to public services and job opportunities. Protests took place in most cities across the KRI and the towns of Sulaimani, Halabja, Said Sadiq, Ranya, Qaladze, Kalar, Chamchamal, Darbandikhan, Shiladze, Kifri; as well as smaller rural less reported protests.

Higher profile activists and those with a previous history of organising protests and demonstrations as well as journalists, particularly those with no links to the KRG parties, would be more likely to be at risk of mistreatment and arrest.

Those arrested are often charged under broad and imprecise terms often relating to espionage, miss use of electronic devices or risk to the state. The judicial process lacks the safeguards necessary to guarantee fair judicial proceedings and there are continued reports of torture or ill treatment in detention facilities.

The evidence is not such that a person will be at real risk of serious harm or persecution simply by being an opponent of or having played a low level part in protests against the KRG that took place in August and December 2020 or any subsequent political activity.

In general, a person will not be at risk of serious harm or persecution on the basis of political activity within the KRI. Any risk of mistreatment and possible persecution regarding political activity in the KRI is centred around protesting against the KRG more generally, rather than as a result of being a supporter, member or carrying out activities on behalf of a specific political party.

Assessment

Updated: 29 June 2023

About the assessment

This section considers the evidence relevant to this note – that is information in the country information, refugee/human rights laws and policies, and applicable caselaw – and provides an assessment of whether, in general:

-

a person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution/serious harm by the Kurdish Regional Government (KRG) because of the person’s actual or perceived political opinion or activities

-

a person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies)

-

a person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory

-

a claim is likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and

-

if a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

Decision makers must, however, still consider all claims on an individual basis, taking into account each case’s specific facts.

1. Material facts, credibility and other checks/referrals

1.1 Credibility

1.1.1 For information on assessing credibility, see the instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

1.1.2 Decision makers must also check if there has been a previous application for a UK visa or another form of leave. Asylum applications matched to visas should be investigated prior to the asylum interview (see the Asylum Instruction on Visa Matches, Asylum Claims from UK Visa Applicants).

1.1.3 In cases where there are doubts surrounding a person’s claimed place of origin, decision makers should also consider language analysis testing, where available (see the Asylum Instruction on Language Analysis).

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – Start of section

The information in this section has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – End of section

1.2 Exclusion

1.2.1 Decision makers must consider whether there are serious reasons for considering whether one (or more) of the exclusion clauses is applicable. Each case must be considered on its individual facts and merits.

1.2.2 If the person is excluded from the Refugee Convention, they will also be excluded from a grant of humanitarian protection (which has a wider range of exclusions than refugee status).

1.2.3 For guidance on exclusion and restricted leave, see the Asylum Instruction on Exclusion under Articles 1F and 33(2) of the Refugee Convention, Humanitarian Protection and the instruction on Restricted Leave.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – Start of section

The information in this section has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – End of section

2. Convention reason(s)

2.1.1 Actual or imputed political opinion.

2.1.2 Establishing a convention reason is not sufficient to be recognised as a refugee. The question is whether the person has a well-founded fear of persecution on account of an actual or imputed Refugee Convention reason.

2.1.3 For further guidance on Convention reasons see the instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

3. Risk

3.1.1 CPIT was unable to find any evidence that substantiates a generalised real risk of mistreatment or risk relating to the support, membership or any activity on behalf of an individual political party in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) in the sources consulted. If there was such a risk, it is reasonable to consider it would be reported on and there would be information available. Based on the available evidence, it is concluded that any risk regarding political activity in the KRI is centred around protesting against the KRG more generally, rather than as a result of being a supporter, member or carrying out activities on behalf of a specific political party.

3.1.2 The evidence is not such that a person will be at real risk of serious harm or persecution simply by being an opponent of, or having played a low level part in protests against the KRG. Despite evidence that opponents of the KRG have been arrested, detained, assaulted and even killed by the Kurdistan authorities, there is no evidence to suggest that such mistreatment is systematic. The instances of mistreatment are small in relation to the vast numbers who attended the protests. Additionally, there is no evidence to suggest that the KRG have the capability, nor the inclination, to target individuals who were involved in the protests at a low level. As such, in general, a person will not be at risk of serious harm or persecution on the basis of political activity within the KRI. The onus is on the person to demonstrate otherwise. Decision makers must consider each case on its merits.

3.1.3 However, available evidence does indicate that the following groups of people may be at higher risk of arrest, detention, assault, excessive use of force and extrajudicial killing by the KRG authorities:

-

Individuals with higher profiles: Those who have a prominent public presence, who are actively involved in or have previous history of organising or participating in protests and demonstrations.

-

Journalists: Those who are seen to be criticising government officials or engage in critical reporting on controversial political or other sensitive issues, for example protests and demonstrations, corruption, abuse of authority etc.

3.1.4 Available evidence indicates that journalists who were covering protests were targeted with excessive force, had equipment seized, damaged or destroyed and were frequently arrested. In February 2021 2 journalists covering protests over unpaid wages were sentenced to 6 years in prison after being found guilty of ‘gathering classified information and passing it covertly to foreign actors in exchange for substantial sums of money’ and possessing ‘illegal weapons’. After receiving their guilty verdict and prison sentence the journalists’ lawyer claimed that their trial was unfair as a week before their court date, Masrour Barzani, the head of the KDP and Prime Minister of the KRG claimed they were spies in a press conference. The targeting, arrest and detention of journalists is in breach of Law No.35 of 2007, known as the Press Law in the Kurdistan Region and Law No.11 of 2013, known as the Right to Access Information Law in the Region of Kurdistan (see Journalists and restrictions on media freedom and Legal context).

3.1.5 The democratically-elected Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) is broad-based, with representatives from all major parties (see Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) and Kurdish parties). Following elections that took place in September 2018 a new Kurdish Government was eventually formed in July 2019 after months of negotiating between the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) and the Gorran (Change) Movement. The current KRG president and prime minister, Nechirvan Barzani and Masrour Barzani respectively, are both members of the KDP. While tensions still exist between the parties, relationships are more stable than they have been in the past (see Relationships between Kurdish parties).

3.1.6 Protests and demonstrations took place throughout 2020 across the KRI for a variety of reasons, including the unpaid salaries of civil servants such as teachers and health care workers, the demand for better public services and job opportunities, regular electricity outages, political and financial corruption and lockdown measures imposed due to the Covid-19 pandemic (see 2020 protests).

3.1.7 In response to the protests and planned protests security forces launched widespread campaigns of arrests across the KRI, often acting pre-emptively by arresting activists at home and setting up checkpoints and barriers at proposed protest locations to try and prevent demonstrations from taking place. Sources also stated that dozens of young men were arrested after calling for protests via their social media accounts. Available evidence indicates that in general most of those arrested were released after short periods in detention. However those with higher profiles who have previous history of organising and taking part in demonstrations were detained for longer periods with some being charged and put on trial (see Arrests and detentions).

3.1.8 In addition to the arrest and detention of demonstrators, available evidence indicates that the KRG security apparatus at times used excessive force and deployed tear gas, rubber bullets and live bullets during the demonstrations resulting in the deaths of 8, mostly young, people and the wounding of more than 50 (see Extrajudicial killings and excessive use of force).

3.1.9 In August and December 2020 KRG authorities raided and closed offices and suspended the broadcasting licence of the media outlet Nalia Radio and Television (NRT) for covering anti-government protests, in breach of the Press Law in the Kurdistan Region and the Right to Access Information Law in the Region of Kurdistan (see Journalists and restrictions on media freedom and Legal context).

3.1.10 For further guidance on assessing risk, see the instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

4. Protection

4.1.1 Where the person has a well-founded fear of persecution from the state they will not, in general, be able to avail themselves of the protection of the authorities.

4.1.2 For further guidance on assessing the availability of state protection, see the instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

5. Internal relocation

5.1.1 Where the person has a well-founded fear of persecution from the state and there is no safe part of the country where they would not be at risk from the state, they are unlikely to be able to relocate to escape that risk.

5.1.2 For more information regarding caselaw and internal relocation within the KRI and Iraq see the CPIN Iraq: Internal relocation, civil documentation and returns.

5.1.3 For further guidance on considering internal relocation and factors to be taken into account see the Asylum Instruction, Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

6. Certification

6.1.1 Where a claim is refused, it is unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

6.1.2 For further guidance on certification, see Certification of Protection and Human Rights claims under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 (clearly unfounded claims).

Country information

About the country information

This contains publicly available or disclosable country of origin information (COI) which has been gathered, collated and analysed in line with the research methodology. It provides the evidence base for the assessment.

The structure and content of this section follow a terms of reference which sets out the general and specific topics relevant to the scope of this note.

Decision makers must use relevant country information as the evidential basis for decisions.

Section updated: 24 March 2023

7. Legal context

7.1 Laws

7.1.1 Article 38 of the Iraqi Constitution (which covers the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI)) states:

‘The State shall guarantee in a way that does not violate public order and morality:

‘First. Freedom of expression using all means.

‘Second. Freedom of press, printing, advertisement, media and publication.

‘Third. Freedom of assembly and peaceful demonstration, and this shall be regulated by law.’[footnote 1]

7.1.2 Article 45 (1) of the Iraqi Constitution states: ‘The State shall seek to strengthen the role of civil society institutions, and to support, develop and preserve their independence in a way that is consistent with peaceful means to achieve their legitimate goals, and this shall be regulated by law.’[footnote 2]

7.1.3 Article 2 of Law No.35 of 2007, also known as the ‘Press Law in the Kurdistan Region’, states:

‘Article (2):

‘First. The press is free and no censorship shall be imposed on it. Freedom of expression and publication shall be guaranteed to every citizen within the framework of respect for personal rights, liberties and the privacy of individuals in accordance with the law…

‘Second. A journalist may obtain from diverse sources, in accordance with the law, information of importance to citizens and with relevance to the public interest.

‘Third. In case of a legal suit, a journalist may keep secret the sources of information and news relevant to the suits brought before the courts unless the courts decide otherwise.

‘Fourth. Every natural or legal person shall have the right to possess and issue journals in accordance with the provisions of this Law.

‘Fifth. No journal shall be closed down or confiscated.’[footnote 3]

7.1.4 For more chapters and articles of Law No.35 of 2007 see the full version of Press Law in the Kurdistan Region published by the Global Justice Project: Iraq (GJPI).

7.1.5 Article 2 of Law No.11 of 2013, also known as the ‘Right to Access Information Law in the Region of Kurdistan, Iraq’ states:

‘Article (2):

‘The present law aims to do the following:

‘First. Enabling the citizens of the region to exercise their right in accessing information with public and private institutions, according to the provisions of the present law.

‘Second. Supporting the transparency and effective participation principles for ensuring democracy.

‘Third. Ensuring a better environment for freedom of expression and publication.’[footnote 4]

7.1.6 For more chapters and articles of Law No.11 of 2013 see the full version of the Right to Access Information Law in the Region of Kurdistan, Iraq published by the Kurdish Media Watchdog Organization (KMWO).

7.1.7 Article 2, 3 and 4 of Law No.6 of 2008, also known as the ‘Law on Prevention of Misuse of Communications Devices in Kurdistan Region, Iraq’ states:

‘Article (2):

‘Any person who misuses a cell phone, any telecommunications device, the Internet or e-mail by threatening, slandering, insulting or spreading fabricated news that provokes terror and causes conversations, fixtures or motion pictures, or (Jury) Contrary to public morals and morals, taking photographs without a licence or permission, assigning honour or incitement to commit crimes or acts of immorality or publishing information relating to private or family life secrets of individuals obtained in any way, even if true, if their dissemination, diversion and distribution would offend or harm them.

‘Article (3):

‘Anyone who intentionally uses and exploits a cell phone, any telecommunications device, the Internet or electronic mail to disturb others in cases other than those mentioned in article 2 of this Law shall be liable to imprisonment for a term of not less than three months and not more than one year and a fine of not less than seven hundred and fifty thousand dinars and not more than three million dinars.

‘Article (4):

‘If the act committed in accordance with articles II and III of this Act results in the commission of an offence, the perpetrator shall be considered an accomplice and shall be punished with the penalty prescribed for the offence committed.’[footnote 5]

7.1.8 N.B. CPIT was unable to find an English translation of the above law in the sources consulted. An Arabic version of the law was found on the Internet Legislation Atlas (ILA) website which was then translated using a free online translation tool. As such 100% accuracy cannot be guaranteed. The original and translated versions of the document can be viewed in Annex A and Annex B.

7.1.9 See Enforcement of laws for more information.

Section updated: 24 March 2023

8. Kurdish people

8.1 Who are the Kurds?

8.1.1 In October 2019 BBC News published an article on Kurdish people which stated:

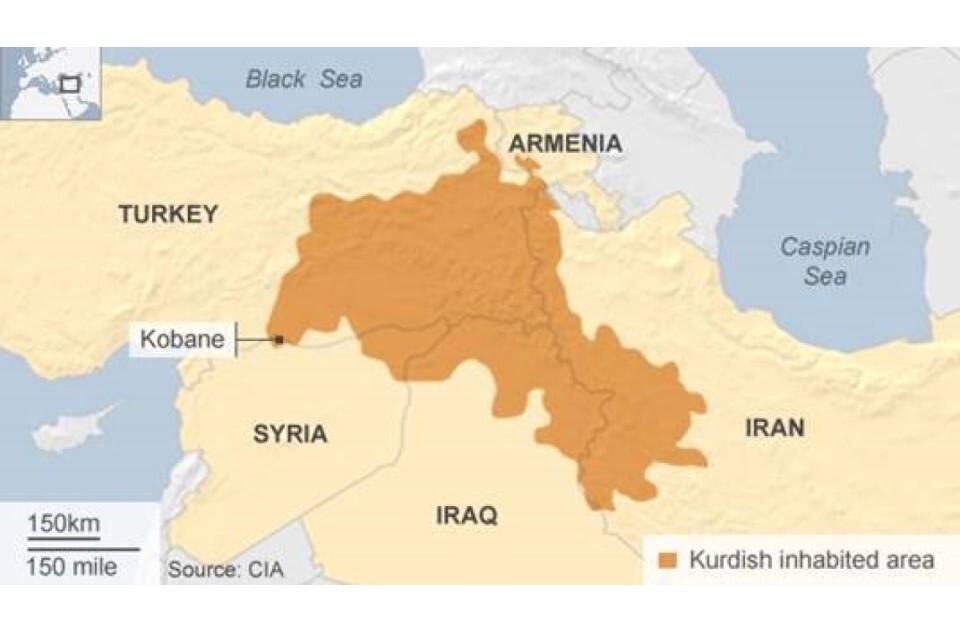

‘Between 25 and 35 million Kurds inhabit a mountainous region straddling the borders of Turkey, Iraq, Syria, Iran and Armenia. They make up the fourth-largest ethnic group in the Middle East, but they have never obtained a permanent nation state.

‘The Kurds are one of the indigenous peoples of the Mesopotamian plains and the highlands in what are now south-eastern Turkey, north-eastern Syria, northern Iraq, north-western Iran and south-western Armenia.

‘Today, they form a distinctive community, united through race, culture and language, even though they have no standard dialect. They also adhere to a number of different religions and creeds, although the majority are Sunni Muslims.’[footnote 6]

8.1.2 The same source also published the below map:

[Map showing a region straddling the borders of Turkey, Iraq, Syria, Iran and Armenia.]

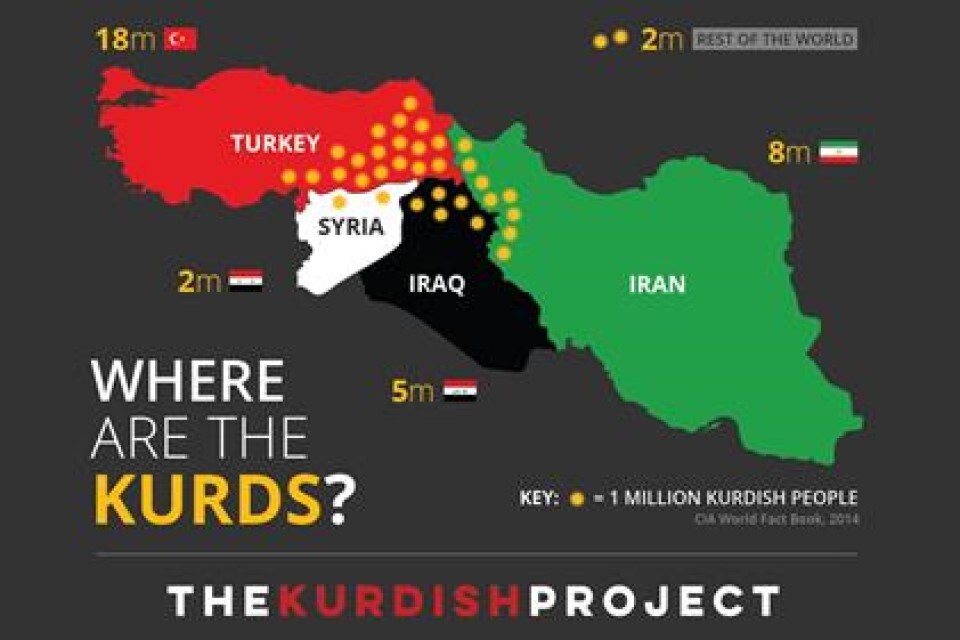

8.1.3 The Kurdish Project, ‘a cultural-education initiative to raise awareness in Western culture of Kurdish people’[footnote 8], published the following map which indicates where Kurdish people are found across Turkey, Syria, Iraq, Iran and the rest of the world:

| Location | Number (millions) |

|---|---|

| Turkey | 18 |

| Iran | 8 |

| Iraq | 5 |

| Syria | 2 |

| Rest of the world | 2 |

8.1.4 The same source also produced an interactive map which highlights cities that have historically been inhabited by large Kurdish populations.

8.1.5 The Kurdish Project also provides information on Kurdish history, Kurdish culture, Kurdish religions, Kurdish politics and women in Kurdistan.

Section updated: 24 March 2023

9. Kurds in Iraq

9.1 Demography

9.1.1 In a January 2021 article entitled ‘Iraq’s population now over 40 million: planning ministry’ Rudaw, a Kurdish media network[footnote 10], reported:

‘“Iraq’s population reached 40,150,000 people in 2020” the [country’s planning] ministry said in a statement released on Tuesday…The ministry’s figures are based on its “central statistical system, as per international standards”, according to its statement.

‘The Kurdistan Region’s population can be estimated to be 5.45 million, according to figures given to Rudaw by planning ministry spokesperson Abdulzahra Hindawi – about 13.7 percent of Iraq’s population.

‘“Sulaimani has the largest population [of Kurdistan Region provinces], which is more than 2.25 million, followed by Erbil province which has 1.9 million people, and Duhok has nearly 1.3 million people,” Hindawi told Rudaw’s Shahyan Tahseen on Tuesday.

‘“Every year [since 2010], the population has increased by 2.6 percent – meaning the population [of the Kurdistan Region] has increased by 850,000 to one million people,” the spokesperson said.’[footnote 11]

9.1.2 A BBC profile of Iraqi Kurdistan published in April 2018 stated that Kurdish people make up between 17% and 20% of the population of Iraq[footnote 12]. Based on the latest population figure provided by Iraq’s planning ministry and the estimated percentage range from the BBC, there are estimated to be between 6.82 and 8.03 million Kurds across Iraq and the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI). An article published by Rudaw in April 2016 stated that official data from the provincial council in Baghdad shows that 300,000 Kurds lived in Baghdad, a fall of 200,000 since 2003[footnote 13].

9.1.3 Precise figures of the numbers of Kurds in Iraq are not available due to lack of recent censuses. The last census to take place in Iraq was in 1997 and did not include the KRI[footnote 14]. A census due to take place in 2020 was postponed in August 2020 due to the Covid-19 pandemic[footnote 15].

9.1.4 Below is a map produced by Geo-Ref.net which shows the population density of the KRI using data from 2018:

| Province | ISO 3166-2 | Capital | Area (km²) | Population | Density (pers/km²) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duhok | IQ-DA | Duhok | 10,956 | 1,292,535 | 118,0 |

| Erbil | IQ-AR | Erbil | 14,872 | 1,854,778 | 124,7 |

| Sulaymaniya | IQ-SU | Sulaymaniya | 20,144 | 2,053,000 | 101,9 |

| Halabja | IQ-HL | Halabja | 889 | 109,000 | 122,6 |

| Total | 46,861 | 5,309,313 | 113,3 |

9.2 Religion

9.2.1 In an undated article on Kurdish religions, the Kurdish Project stated:

‘The most widely practiced Kurdish religion is Islam. According to a 2011 study conducted by the Pew Research Center, nearly all (98%) Kurds in Iraq identified as Sunni Muslim, while the other 2% identified as Shiite Muslims. The study noted that a small minority identified as neither Sunni nor Shiite. These Kurds prescribe to a number of religions, including a small percent who practice Christianity and Judaism, and speak Aramaic, the language that many scholars believe to have been spoken by Jesus Christ. Other religions in Kurdistan include Judaism, Babaism, Yezidism, and Yazdanism, which includes sects such as Yarsanism, and Alevism.’[footnote 17]

9.2.2 An article entitled ‘Who are the Iraqi Kurds?’ published in August 2014 by the Pew Research Center stated the following and produced the following chart:

‘Nearly all Iraqi Kurds consider themselves Sunni Muslims. In our survey, 98% of Kurds in Iraq identified themselves as Sunnis and only 2% identified as Shias. (A small minority of Iraqi Kurds, including Yazidis, are not Muslims.) But being a Kurd does not necessarily mean alignment with a particular religious sect. In neighboring Iran, according to our data, Kurds were split about evenly between Sunnis and Shias.

Iraqi Arabs are more diverse: 30% Sunni Muslim, 62% Shia Muslim, 8% Other. They make up 78% of Iraq’s population.

9.3 Language

9.3.1 Kurdish and Arabic are the major languages in Iraq[footnote 19].

9.3.2 The General Board of Tourism of Kurdistan – Iraq (GBTKI) stated the following in an undated article entitled ‘About Kurdistan – Language’:

‘The Kurdistan Region’s official languages for government purposes are Kurdish and Arabic. Kurdish is in the Indo-European family of languages. The two most widely spoken dialect of Kurdish are Sorani and Kurmanji. Other dialects spoken by smaller numbers are Hawrami (also known as Gorani) and Zaza.

‘The Sorani dialect uses Arabic script while the Kurmanji dialect is written in Latin script. Sorani is spoken in Erbil and Slemani governorates, while Kurmanji is spoken in Duhok governorate and some parts of Erbil governorate. As the Region’s Kurdish-language media has developed and the population has moved, today nearly all people in the Kurdistan Region can speak or understand both of the major dialects. The Kurdistan Regional Government’s policy is to promote the two main dialects in the education system and the media.’[footnote 20]

Section updated: 24 March 2023

10. Kurdistan Region of Iraq

10.1 Map and background

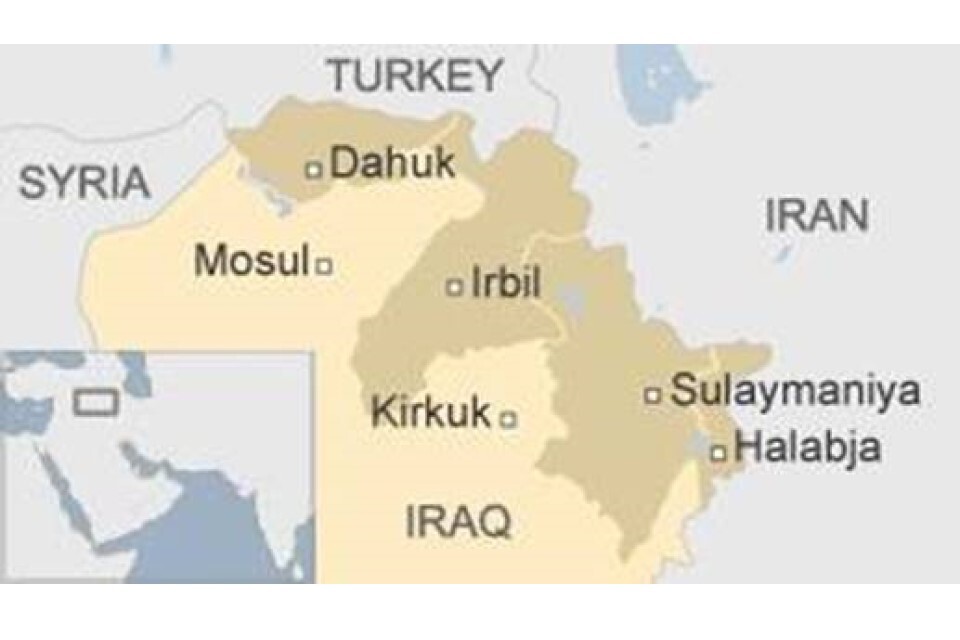

10.1.1 Below is a map of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) showing the four governorates, Dahuk, Irbil (Erbil), Sulaymaniyah and Halabja:

[The map shows the four areas listed above, they cover the area from the northernmost part of Iraq to the easternmost part, along the north-eastern border with Turkey and Iran.]

10.1.2 The GBTKI stated the following in an undated article entitled ‘About Kurdistan - General information’ ‘The name Kurdistan literally means Land of the Kurds. In the Iraqi Constitution, it is referred to as the Kurdistan Region…Iraqi Kurdistan or the Kurdistan Region is an autonomous region of Iraq. It borders Iran to the east, Turkey to the north, Syria to the west and the rest of Iraq to the south. The regional capital is Erbil, also known as Hawler. The region is officially governed by the Kurdistan Regional Government.’[footnote 22]

10.1.3 The website of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) stated the following in an undated article entitled ‘Facts & Figures’:

‘The establishment of the Kurdistan region dates back to 1970. In March 1970 an autonomy agreement was signed with Baghdad that declared autonomy for the region, after years of heavy fighting. The Iran-Iraq war during the 1980s and the Anfal genocide campaign of the Iraqi army devastated the population and nature of Iraqi Kurdistan.

‘Following the 1991 uprising of the Kurdish people against Saddam Hussein, many Kurds were forced to flee the country to become refugees in bordering regions of Iran and Turkey A northern no-fly zone following the First Gulf War in 1991 to facilitate the return of Kurdish refugees was established. As Kurds continued to fight government troops, Iraqi forces finally left Kurdistan in October 1991 leaving the region to function de facto independently; however, neither of the two major Kurdish parties had at any time declared independence and Iraqi Kurdistan continues to view itself as an integral part of a united Iraq but one in which it administers its own affairs. The 2003 invasion of Iraq by joint coalition and Kurdish forces and the subsequent political changes in post-Saddam Iraq led to the ratification of the new Iraqi constitution in 2005.

‘The new Iraqi constitution stipulates that Iraqi Kurdistan is a federal entity recognized by Iraq, and gives Kurdish joint official language status in all of Iraq, and sole official language status in Iraqi Kurdistan.’[footnote 23]

10.1.4 The BBC profile of Iraqi Kurdistan published in April 2018 stated that: ‘Iraq’s 2005 Constitution recognises an autonomous Kurdistan region in the north of the country, run by the Kurdistan Regional Government. This was the outcome of decades of political and military efforts to secure self-rule by the Kurdish minority… Only in Iraq have they managed to set up a stable government of their own in recent times, albeit within a federal state.’[footnote 24]

10.1.5 The BBC also produced a Iraqi Kurdistan timeline, last updated in October 2017.

10.2 Disputed areas and 2017 Kurdish independence referendum

10.2.1 In June 2022, the European Union Agency for Asylum (EUAA) formally known as the European Union Agency for Asylum (EASO), published a report entitled, ‘Country Guidance: Iraq’, which stated:

‘The disputed territories of Iraq are located in parts of Erbil, within [the] KRI, and across parts of Kirkuk, Diyala, Salah al-Din, and Ninewa governorates. These areas have been the subject of contested control between the KRG and the Iraqi central government when Kurds took control of these areas lying outside the KRI border, after the fall of Saddam Hussein. The question of their control was addressed in Article 140 of the 2005 Constitution, but this has never been resolved.

‘In 2014, in the context of the war with ISIL [Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant – also known as Daesh], the Peshmerga [the armed forces of the KRG] moved into some areas of the disputed territories and took over control there, including Kirkuk and parts of Ninewa, populated by ethnic and religious minorities.’[footnote 25]

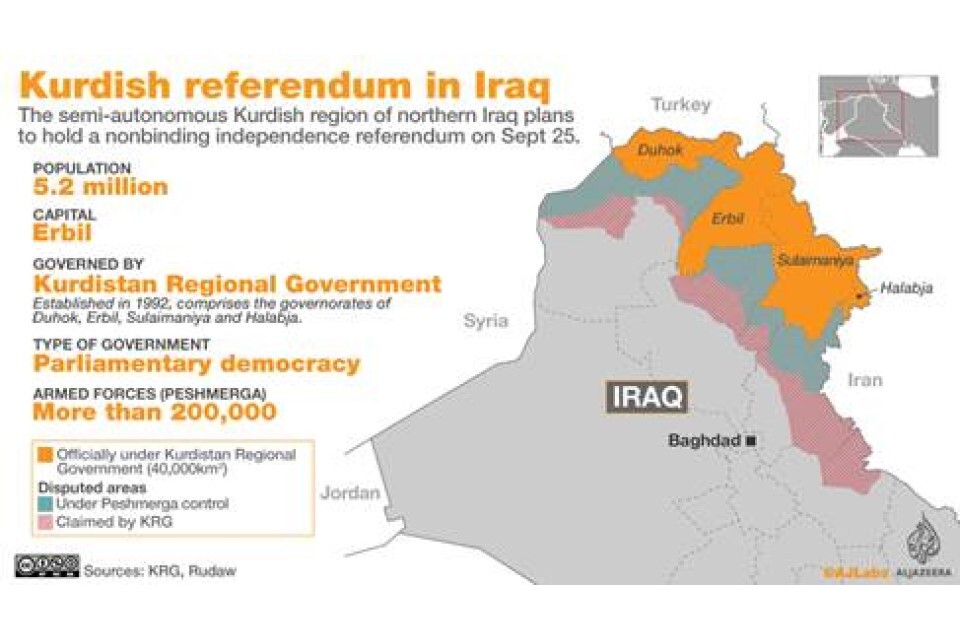

10.2.2 On 25 September 2017 a referendum on whether to support the KRI’s separation from Baghdad and the Iraqi state took place. In an article entitled ‘Iraqi Kurds vote in controversial referendum’, Al Jazeera stated:

‘People in the semi-autonomous Kurdish region of northern Iraq are voting in a controversial referendum, amid rising tensions and international opposition.

‘Polls opened at 05:00 GMT with balloting also taking place in the disputed areas between the northern city of Erbil and the capital Baghdad, as well as the oil-rich province of Kirkuk, which is ethnically mixed.

‘The central government in Baghdad, which strongly opposes the referendum, sought control of the region’s international border posts and airports on Sunday [24 September 2017], in anticipation of Monday’s vote.

‘…About 2,065 polling stations are open for 10 hours. A total of 5.6 million people are eligible to vote in the Kurdistan Regional Government area and other Kurdish-controlled areas in northern Iraq, according to the election commission.

‘Voters will be asked: “Do you want the Kurdistan region and Kurdish areas outside the region to become an independent state?”’[footnote 26]

10.2.3 The same source also published the below map showing the areas which were officially under the KRG control, the areas that were under Peshmerga control and the areas which are claimed by the KRG:

Kurdish referendum in Iraq

The semi-autonomous Kurdish region of northern Iraq plans to hold a nonbinding independence referendum on Sept 25.

Population

5.2 million

Capital

Erbil

Governed by

Kurdistan Regional Government. Established in 1992, comprises the governorates of Duhok, Erbil, Sulaimaniya and Halabja.

Type of government

Parliamentary democracy

Armed forces (Peshmerga)

More than 200,000

Areas

From north-east going south-westwards:

Officially under Kurdistan Regional Government (40,000 square kilometres)

Under Peshmerga control (disputed)

Claimed by KRG (disputed)

10.2.4 On 27 September 2017 the BBC published an article entitled ‘Iraqi Kurds decisively back independence in referendum’ which stated:

‘People living in northern Iraq voted overwhelmingly in favour of independence for the Kurdistan Region in Monday’s controversial referendum.

‘The electoral commission said 92% of the 3.3 million Kurds and non-Kurds who cast their ballots supported secession.

‘The announcement came despite a last-minute appeal for the result to be “cancelled” from Iraq’s prime minister.

‘Haider al-Abadi [Iraq’s then prime minister] urged Kurds to instead engage in dialogue with Baghdad “in the framework of the constitution”.

‘Kurdish leaders say the “Yes” vote will give them a mandate to start negotiations on secession with the central government in Baghdad and neighbouring countries.

‘…In a speech to parliament before the result was announced, Mr Abadi insisted that he would “never have a dialogue” about the referendum’s outcome with the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG).

‘The vote was vehemently opposed by Baghdad and much of the international community, which expressed concern about its potentially destabilising effects, particularly on the battle against IS [Islamic State].

‘Mr Abadi said his priority now was to “preserve citizens’ security” and promised to “defend Kurdish citizens inside or outside” the Kurdistan Region.

‘”We will impose Iraq’s rule in all districts of the region with the force of the constitution,” he added.’[footnote 28]

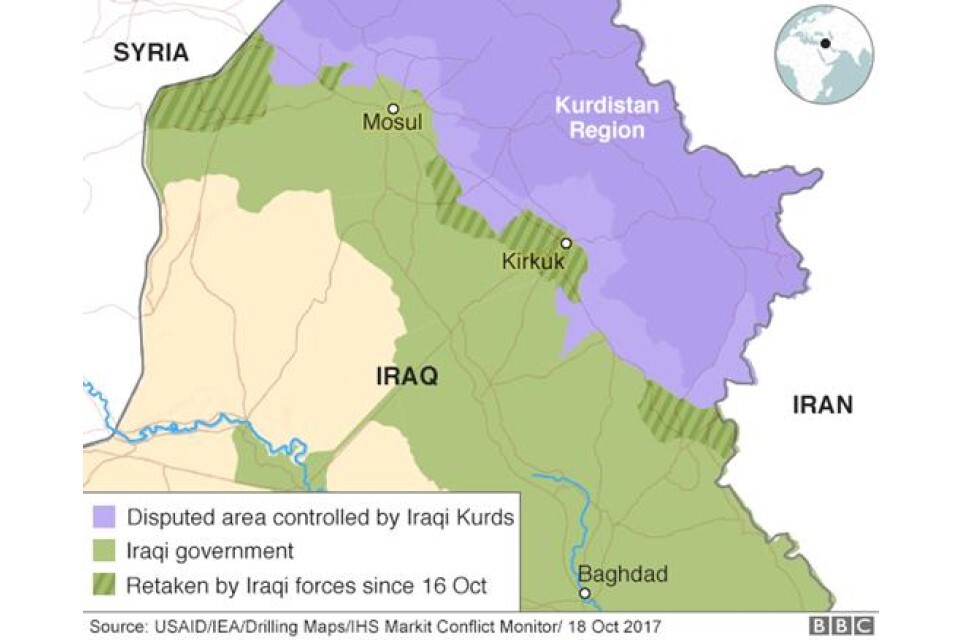

10.2.5 On 18 October 2017 the BBC published an article entitled ‘Iraq takes disputed areas as Kurds “withdraw to 2014 lines”’ which stated:

‘Iraq’s military says it has completed an operation to retake disputed areas held by Kurdish forces since 2014. On Monday and Tuesday [16 and 17 October 2017] troops retook the multi-ethnic city of Kirkuk and its oilfields, as well as parts of Nineveh and Diyala provinces.

‘…The military operation came three weeks after the Kurds held an independence referendum, which Iraq’s prime minister said was now a “thing of the past”. Mr Abadi called for dialogue with the Kurdistan Regional Government on Tuesday night, saying he wanted a “national partnership” based on Iraq’s constitution.

‘…A statement issued by the Iraqi military on Wednesday announced that security had been “restored” in previously Kurdish-held sectors of Kirkuk province, including Dibis, Multaqa, and the Khabbaz and Bai Hassan North and South oil fields.

‘“Forces have been redeployed and have retaken control of Khanaqin and Jalawla in Diyala province, as well as Makhmur, Bashiqa, Mosul dam, Sinjar and other areas in the Nineveh plains,” it added.

‘Peshmerga fighters moved into the areas after IS swept across northern and western Iraq in June 2014 and the army collapsed. A senior Iraqi military commander also told Reuters news agency: “As of today we reversed the clock back to 2014.”’[footnote 29]

10.2.6 The same source additionally published the below map[footnote 30] produced using a number of different sources following the Iraqi military’s operations to retake disputed areas:

[Map shows disputed area controlled by Iraqi Kurds in north east. There are 4 areas retaken by Iraqi forces since 16 Oct along the border with the area under control of the Iraqi government]

Section 7 updated: 24 March 2023

11. Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG)

11.1 Executive branch

11.1.1 In March 2023 Freedom House published its annual report on political rights and civil liberties in 2022. It stated:

‘The Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), composed of Iraq’s northernmost provinces, is ostensibly led by a president with extensive executive powers, but former long-term KRG president, Masoud Barzani, maintains significant political influence. In 2019, Nechirvan Barzani, Masoud’s brother, was elected president by the Iraqi Kurdish parliament after the position had been vacant for nearly two years. Masrour Barzani, Masoud’s son, was appointed and sworn in as prime minister the same month. Both Barzanis, the current president and prime minister, are members of the KDP.’

‘… In the Kurdistan region, although elected KRG representatives have jurisdiction, in practice, the region is split between the Erbil and Dohuk governorates, under KDP control, and Sulaymaniyah, controlled by the PUK. Each region has its own politically affiliated internal security (Asayish) and military forces (Peshmerga).’[footnote 31]

11.2 Legislative branch

11.2.1 The Freedom House report published in March 2023 stated:

‘…In Iraqi Kurdistan, the 111-seat Kurdish parliament is elected through closed party-list proportional representation in a single district, with members serving four-year terms. Since the 2018 elections, the governing KDP has maintained a plurality of seats, followed by the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) and the Gorran movement. The elections were plagued by fraud allegations and other irregularities, and Gorran and other smaller parties rejected the results. Political disputes between the KDP and PUK concerning the formation of the electoral committee led to the cancelation of the October 2022 Kurdish parliamentary elections; no subsequent date had been set as of year-end.’[footnote 32]

11.2.2 The Kurdistan Parliament website lays out the areas that the KRG has power over as per the Iraqi constitution ‘As provided in the federal constitution of Iraq, Parliament has considerable power to debate and legislate on policy in a wide range of areas: health services, education and training, policing and security, the environment, natural resources, agriculture, housing, trade, industry and investment, social services and social affairs, transport and roads, culture and tourism, sport and leisure, and ancient monuments and historic buildings.’[footnote 33]

11.2.3 The same source additionally stated:

‘The Kurdistan Parliament has 19 standing committees that work on a wide range of subject areas. Much of Parliament’s work takes place in these committees. Their mandate is to study bills (draft laws), propose bills and give opinions, study suggested amendments, and to submit them to Parliament’s leadership. Committees provide important input during the stages of passing a bill through Parliament into law. Committees also scrutinize the performance of government institutions in their area of work, and take evidence and opinions from experts and civil society. These mandates are in Article 38 of parliament’s procedural rules.

‘According to Article 37 of Parliament’s procedural rules, committees are formed at the first session following a parliamentary election.’[footnote 34]

11.2.4 For information about current parties, MPs and the Presidency see the members and parties webpage of the Kurdistan Parliament website.

11.3 Formation of current government

11.3.1 In May 2019 Rudaw published an article entitled ‘KDP strikes new government deals with Gorran and PUK’ which stated:

‘The Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) has reached a final understanding regarding the next Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) in separate deals signed with the Change Movement (Gorran) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) in Sulaimani on Sunday [5 May 2019].

‘Nechirvan Barzani, leading a delegation from the KDP, arrived in Sulaimani on Sunday morning to meet with the PUK and Gorran, hoping to end months of discussions over the formation of the next government.

‘“We have reached an understanding and we hope that in the next few days we will start the process of forming the next cabinet by initially reviving the Kurdistan presidency law,” KDP spokesperson Mahmoud Mohammed told reporters Sunday afternoon after the meeting between his party and Gorran.

‘…The KDP first reached a deal with Gorran in February with Gorran agreeing to enter the government and pushing a package of institutional reforms…The government-formation process has dragged on for more than seven months. Parliamentary elections were held on September 30, 2018, with the KDP coming out on top, winning 45 seats in the 111-seat legislature, but not securing an outright majority. It has spent more than half a year trying to build a governing coalition with the PUK, which won 21 seats, and Gorran, which has 12 seats.

‘After signing its agreement with Gorran, KDP then arrived at a similar pact with the PUK in March [2019]…’[footnote 35]

11.3.2 On 11 July 2019 the Washington Institute published an article entitled ‘Iraqi Kurdistan’s New Government’ which stated:

‘On July 10, the Kurdistan Regional Government’s parliament voted in a new cabinet led by Prime Minister Masrour Barzani, eldest son of former president Masoud Barzani. Masrour succeeds his cousin Nechirvan Barzani, the long-serving KRG premier who was sworn in last month as president. The cabinet now comprises twenty-one ministers, including three without portfolio. Two seats were earmarked for Christian and Turkmen representatives; three women won seats as well, the largest number to date.

‘It took nine months to form the new cabinet following last September’s parliamentary elections. The delay was caused by deep divisions between and within the KRG’s main political parties.’[footnote 36]

11.3.3 The Arab Weekly’s (an ‘independent publishing house based in London[footnote 37]) June 2019 article ‘Barzani family members seal rule over Iraqi Kurds’ noted:

‘The succession of two powerful cousins to the top government posts in Iraqi Kurdistan has sealed the Barzani family’s “monarchic” rule over the autonomous region…With his son and nephew at the helm, veteran leader Masoud Barzani is expected to remain the region’s “real boss,” despite no longer holding a formal government position.

‘…With the cousins in command, analysts expect the KRG’s decision-making process — and the policies themselves — will be increasingly influenced by family politics.’[footnote 38]

11.3.4 For more information see Relationships between Kurdish parties.

11.4 Electoral process

11.4.1 The Kurdish Parliament undated webpage details the electoral process in the KRI:

‘The last election for the 111-seat legislature was held on 30 September 2018. Anyone aged 18 or over who is a citizen of the Kurdistan Region and is on the electoral register is eligible to vote in a direct, universal and secret ballot.’

‘…The electoral system is a partially open-list form of proportional representation: Choosing from many parties and lists, voters can vote either for one party as a whole, or can vote for an individual candidate from a party. This system incentivises parties to select attractive candidates, and MPs are more accountable to the electorate than in a closed list system.’

‘..Parliamentary elections are held at least every four calendar years, (as stipulated in Article 8 of the Kurdistan Electoral Law).’

‘…A minimum quota of 30% of seats are reserved for women MPs, and 11 seats are reserved for parties representing minorities: five for Turkmen parties, five for Christian parties, and one for Armenian parties. Please click here to see the parties and current MPs elected to parliament.’[footnote 39]

11.5 Electoral fraud in 2018

11.5.1 In June 2018, Al Monitor published an article entitled ‘Disputes over election results threaten conflict in Iraq’s Kirkuk’ which stated:

‘On May 30 [2018], the Independent High Electoral Commission of Iraq annulled votes cast at more than 1,000 of the country’s polling stations, including 186 stations in Kirkuk, a city that has faced political unrest among its three social components — Arabs, Kurds and Turkmen — since the elections on May 12 [2018].

‘On the same day, Jan Kubis, the head of the United Nations Assistance Mission for Iraq, talked during a meeting of the United Nations Security Council in New York, where he noted reports of electoral fraud and said that Kirkuk was “one of several hotspots” of tension over the election results, adding that the situation there continues to be “volatile.”…

‘Al-Monitor secured a copy of a May 30 [2018] press statement by head of the electoral commission Riad Badran. The statement said, “The Kirkuk Election Office was unable to reach the ballot boxes because of the gathering of some groups affiliated with certain political parties.”…

‘Toran, who is a member of the current Iraqi parliament, accuses the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) — which is led by the two sons of the PUK’s late leader Jalal Talabani, Qubad and Bafel — of “vote-rigging” in Kirkuk…

‘Kurds indirectly accuse members of the Turkmen Front in Kirkuk, who are protesting against the election results, of “conspiring” against the peaceful coexistence in the governorate…

‘Arabs in Kirkuk also joined the protests against the election results. Arab political figures there believe the PUK has rigged the vote in the governorate because it seeks the return of peshmerga forces to Kirkuk.

‘Kirkuk Gov. Rakan al-Jabouri, who belongs to the Arab Coalition that came in second in the governorate after securing three seats in the future parliament, accused the electoral commission of covering up the fraud and vote-rigging in Kirkuk elections.

‘The Arab group in the Kirkuk Governorate Council warned of a conflict that may elevate the crisis in the governorate to an “unknown” state because of the results of the current elections. All of these serious repercussions indicate that there is a crisis looming in Kirkuk as long as the integrity of the elections remains in question.’[footnote 40]

11.5.2 On 6 June 2018 the BBC published an article entitled ‘Iraqi parliament orders manual election recount’ which stated:

‘Iraq’s parliament has voted to carry out a manual recount of votes cast in last month’s legislative elections, amid allegations of widespread fraud.

‘MPs also replaced the leadership of the election commission and annulled the votes of overseas and displaced Iraqis. On Tuesday [5 June 2018], Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi warned that security agencies had evidence of “unprecedented” violations.He said the main issue was with the electronic vote-counting machines that were used for the first time on 12 May [2018].’[footnote 41]

11.6 Kurdish participation in national politics

11.6.1 The Freedom House report published in March 2023 stated:

‘After national elections, the Council of Representatives (CoR) chooses the largely ceremonial president, traditionally Kurdish, who in turn appoints a prime minister, traditionally Shia, nominated by the largest bloc in the parliament. The prime minister, who holds most executive power and forms the government, serves up to two four-year terms. In October 2022, after a year-long political paralysis, Prime Minister Muhammad Shia al-Sudani and his government, supported by the pro-Iran Coordination Framework, were approved by the parliament. Earlier that month, the KDP–aligned candidate, Abdul Latif Rashid, was elected as president.

‘…The 329 members of the CoR are elected every four years from multimember open lists in each province. The October 2021 parliamentary elections were generally viewed as credible by international observers, despite documented cases of voter and candidate intimidation, bribing of voters, journalists being prevented from covering the voting, arrests of activists calling for an election boycott, and the lowest voter turnout since the end of the Saddam Hussein regime.’[footnote 42]

11.6.2 On 20 March 2023, The New Arab, a ‘non-partisan news outlet that focuses on issues of democracy, social justice and human rights’[footnote 43], published an article entitled ‘Iraq to hold powerful provincial council elections on 6 November’ which stated: ‘Iraq’s parliament has set 6 November [2023] as the date for elections for provincial councils, powerful bodies that were dissolved amid anti-government protests in 2019. The elections for the councils, the first in a decade, will take place in 15 of 18 Iraqi provinces, excluding the three provinces in the autonomous Kurdistan region of northern Iraq.’[footnote 44]

Section 8 updated: 24 March 2023

12. Kurdish parties

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – Start of section

The information in this section has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – End of section

Section 9 updated: 26 April 2023

13. Relationships between Kurdish parties

13.1 KDP and PUK

13.1.1 An article entitled ‘The Iraqi Kurds’ Destructive Infighting: Causes and Consequences’ written by Bekir Aydogan and published by the London School of Economics Middle East Centre (LSEMEC) in April 2020 provided information on the background of the relationship between the KDP and the PUK and stated:

‘The Barzani family-led Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), based in Erbil, and the Talabani family-led Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), based in Sulaimaniya, have long dominated the politics of Iraq’s Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG). Historical, ideological and sociological differences between the two parties are said to lie at the root of their disagreements. The long-held mutual mistrust and conflict further stems from each accusing the other of collaborating with the enemy and betraying the Kurdish cause. With the near-total political dominance of these two strongest Iraqi Kurdish actors, any conflict between the KDP and the PUK hugely damages the KRG as a whole, whereas their collaboration is crucial for the region’s development. The disunity between the Barzani and Talabani factions within the KDP during the 1960s, the bloody infighting from 1994 to 1998 and lastly, following the 2017 independence referendum, the loss of oil-rich Kirkuk, betrayal allegations and more brewing conflicts between the KDP and PUK have shown how this rivalry is wont to imperil the significant gains the Iraqi Kurds have made.

‘…The emergence of disagreements between the KDP and PUK is said to have been due to the quest for hegemony, as well as the ideological and sociological differences related to their leaders, followers and geographies. While the group led by the KDP’s first leader Mustafa Barzani was described as more tribal, internally well-disciplined, traditional and conservative, the rival group, mostly comprised of KDP politburo members led by Ibrahim Ahmed and Jalal Talabani, was distinguished as being more reformist, urban, revolutionary and left-leaning. Talabani had greater influence on the young and urban populations in Sulaimaniya with his reformist ideas, but Barzani’s traditional and nationalist discourse impressed people in the Barzan district and its surroundings.

‘These ideological and sociological divisions combined with a lust for absolute power sparked off violent intra-KDP disagreements and conflicts. Particularly during the 1960s and later, the two conflicting groups’ unilateral relations with the Baghdad government gave it the chance to play each faction off against the other, with the result that the Iraqi Kurds’ aspirations for autonomy were easily stifled. Following the dissolution of the 1970 Autonomy Agreements between Saddam Hussein and Mustafa Barzani due to the Algiers Agreement between Iraq and Iran in 1975, which ended Iran’s support for the Kurds against Iraq, the KDP faced a crisis and subsequently, the Ahmed-Talabani group formed the PUK. The establishment of the PUK formalised the rivalry and dichotomy between the two groups.’[footnote 45]

13.1.2 The same source further stated:

‘The US-imposed no-fly zone in 1991 in northern Iraq both protected Iraqi Kurds from Saddam’s forces and resulted in an equal power-sharing arrangement between the KDP and PUK after the 1992 election. The bloody infighting the two groups engaged in between 1994–8 derived from disputes over energy revenues and power sharing, leading to the KDP seeking support from the same Ba’athist forces who had previously used chemical weapons against the Kurds, and the PUK being supported by Iran, who had used the Kurds to provoke Saddam. The result was once again seriously damaging for the Iraqi Kurds, leaving them close to losing their de facto autonomy in northern Iraq. The US-brokered Washington Peace Agreement between the KDP and PUK in 1998 made the duopoly permanent, institutionalising the separate administrations in Erbil and Sulaimaniya.

‘Due to their help in ousting Saddam Hussein in 2003, the US rewarded the Iraqi Kurds by ensuring official autonomy was written into the 2005 Iraqi Constitution. KDP leader Masoud Barzani was given the KRG presidency and the PUK leader Jalal Talabani was granted the Iraqi Presidency, forming an accommodation between the rival parties. The KDP and PUK’s decision to form a single list for the elections in 2004, and to arrange a fifty-fifty power sharing alliance in 2007, brought about stability, safety and development in the KRG, also culminating in economic and political achievements through joint relations with the Baghdad government. However, the power-sharing alliance – as it had in the 1990s – made the dual administration permanent and prevented the parties from institutionalising their divided structures under a single roof.

‘…Coming under intense criticism because of budget cuts, failure to pay civil servants’ salaries, accusations of holding an ‘illegal’ presidency and mass protests, KRG president Masoud Barzani held an independence referendum for the region on 25 September 2017, which was regarded by the opposition as an effort to bolster Barzani’s sinking popularity. The PUK nevertheless did not publicly oppose the referendum, as they could not be seen as opposing efforts towards achieving independence. However, the Talabani clan’s 16 October [2017] withdrawal of Peshmerga forces from Kirkuk in the face of the Iraqi army triggered major tension and accusations of betrayal, leaving the Kirkuk oil fields in the hands of Baghdad and the Iraqi Kurds in an economic and political crisis. KDP accusations against Bafel, Lahur and Aras Talabani, alleging that they collaborated with Iranian General Qasem Soleimani and the Baghdad government to retreat from Kirkuk, have once again resurfaced. Conflicting allegations and infighting cost the KRG oil-rich Kirkuk, which produced nearly half of its energy revenues, and almost all the disputed areas are now under the control of Baghdad. Furthermore, any chance of institutionalising the dual administrations has been put on ice for the foreseeable future.

‘Although the KRG has had de facto autonomy since 1991, made official in 2005, as well as the support of Western countries in order to institutionalise its divided administrations, critics point out that it still maintain almost the same dual administrative structure as it had in the 1990s. The two parties have been criticised for putting the interests of their family, tribes and party allegiance above the interests of the Iraqi Kurds. Though there are opposition parties, elections and a joint parliament, the KDP and PUK have their own intelligence agencies and Peshmerga units that further disunity. Such conflicts and divided administrations are, perhaps, the biggest obstacles facing Iraqi Kurds.’[footnote 46]

13.1.3 In March 2019 Al Jazeera published an article, citing various sources, entitled ‘Government formation in Iraq Kurdish region closer after KDP-PUK deal’ which stated:

‘The two main political parties in Iraq’s semi-autonomous Kurdish region have struck a four-year deal paving the way for the formation of a new Kurdish Regional Government (KRG), according to local media.

‘The political agreement signed on Monday [4 March 2019] between the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) comes months after September’s [2018] parliamentary elections.

‘“We both are winners. Our people are the winners,” Sadi Pira, a PUK member, was quoted as saying by Kurdish news outlet Rudaw.

‘“The security of our people is the priority … I hope everyone thinks of the people’s interests, not partisan interests,” Fazil Mirani, secretary of the KDP’s executive committee, said.

‘According to Rudaw, the new deal is expected to replace the KDP’s and PUK’s “redundant” so-called “Strategic Agreement”, which united the region under a KRG administration in 2005, and included measures to accelerate the formation of a new government.

‘At a joint press conference following the signing of the deal in Erbil, PUK spokesperson Latif Sheikh Omar said a commission would be established to follow up on the implementation of the agreement.

‘The deal would also result in the formation of parliamentary committees, local media outlet Kurdistan 24 reported.

‘The two major parties, which have ruled the Kurdish region under a power-sharing agreement, have been at odds since the region’s failed bid for independence from Iraq in a controversial 2017 referendum.’[footnote 47]

13.1.4 In July 2020 NRT TV published an article entitled ‘Tensions Persist Between PUK, KDP, Issues Need To Be Resolved: PUK Official’ which stated:

‘The secretary of the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan’s (PUK) General Leadership Council said on Sunday (July 19) that a number of outstanding issues have emerged between the PUK and the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) since the former’s Fourth Congress in December.

“The iceberg of relations between the [PUK] and the [KDP] no longer exists compared with the past,” Secretary of the General Leadership Council Farid Asasard told his party’s affiliated media outlets, referring to the historically chilly relations between the parties, but added that a number of problems persist and that they need to be settled.

‘He did not identify any specific issues, but recent controversies include a military stand off in Zini Warte, accusations of spying, and procedural fights in the Kurdistan Parliament, all playing out in front of a backdrop of deteriorating economic conditions and personal rivalries between leading figures of the KDP and PUK.

‘…During his remarks, Asasard said that the PUK has put in place a mechanism to meet with the KDP regarding their relations in a near future, but did not provide details.

‘He also said that the PUK has developed strong relationships with all the political parties in Sulaimani and Halabja governorates, but has not been successful at doing so in Erbil and Duhok, which are dominated by the KDP.’[footnote 48]

13.1.5 In December 2020 the Institute of Regional & International Studies (IRIS) at the American University of Iraq, Sulaimani, published a report entitled ‘Why Did Protests Erupt in Iraqi Kurdistan?’ which stated:

‘Since the ill-fated Kurdish referendum for independence in September 2017, the two parties have been at odds with one another in increasingly public ways. The KDP has accused the PUK of betraying Kurdistan by handing Kirkuk over to the federal government in October 2017, and the KDP subsequently placed obstacles in the way of PUK obtaining key appointments (i.e. the governorship of Kirkuk and the federal presidency). The PUK in turn has responded in a number of ways, including through the strategic deployment of public protests to undermine the leadership of Masrour Barzani over the KRG administration. It is generally understood that PUK factions quietly supported a series of contained, organized protests in Sulaimani over the past months – all of which cited the failure of the KRG to deliver on salaries and infrastructure.’[footnote 49]

13.1.6 An article published in April 2021 by Rudaw entitled ‘Kurdistan Region parties meet to promote unity’ stated:

‘The President of the Kurdistan Region chaired a meeting on Thursday with the leaders of Kurdistan Region political parties to promote unity and end party rivalries, a presidential advisor has told Rudaw.

‘“The main purpose of the meeting was to get the parties closer together so that there’s a unified Kurdish dialogue to deal with the current sensitive political situation in Iraq and the region as a whole,” Dilshad Shahab told Rudaw’s Sangar Abdulrahman.

‘“There has been a sense of separation between the political parties lately, and this separation has had a negative impact on Kurdistan’s position,” he added.

‘“The meeting focused on the current situation in the Kurdistan Region and exercising constitutional rights, protecting the achievements and steps for a better future, realism and a sense of responsibility for all,” read a statement from the presidency.

‘Relations between the ruling Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) deteriorate occasionally, and tensions arise from time to time between the two political parties.

‘The KDP and PUK have shared power in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq since the 90s, with their own separate but coexisting zones of influence.

‘…Alongside the Change Movement (Gorran), the KDP and the PUK formed a new KRG cabinet in 2019. The stability of the KRG depends heavily on good relations between the parties, as well as the shares of Kurds in Iraqi governmental positions.

‘During his Newroz message last month [March 2021], President Barzani invited political parties to come together and hold a meeting in an attempt to “put an end to harmful rivalries and disagreements.”

‘In February [2021], Kurdistan Region Prime Minister Masrour Barzani said he hoped “all the forces and parties in Kurdistan will unite in supporting and advocating for the constitutional framework of the Kurdistan Region and in providing the legitimate rights and demands of the people of Kurdistan.”

‘Shahab also added that “the world” is encouraging Kurdish unity. “On the other hand, our rivals and opponents have high hopes for conflict between the political parties in Kurdistan.”

‘“That’s why I think these steps will have a positive impact and will be a way forward of a better relationship in the future.”

‘PUK politburo member Mustafa Chawrash encouraged unity between the two parties and said success and shortcomings are present on both sides.

‘“The problems between PUK and PDK, or other parties, are that sometimes no one listens to the other. Look at parliament: parliament is for lawmaking, not disputes. All of us have to try” he told Rudaw’s Shahyan Tahsin on Thursday.’[footnote 50]

13.1.7 In May 2023 Rudaw published an article entitled ‘Diplomatic missions commend KDP, PUK rapprochement’ which stated:

‘Diplomatic missions in the Kurdistan Region welcomed Tuesday the recent intra-Kurdish rapprochement between the Region’s top political parties, while stressing the need to cooperate to hold “fair and free” elections on time.

‘…A joint statement by the diplomatic representations of the United Kingdom, United States, Germany, the Netherlands, Canada, the European Union, France, Czech Republic, Greece, Italy, Bulgaria, Poland, and Romania commended recent strides by the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) to resolve tensions after the PUK’s ministerial team began attending cabinet meetings following a five-month hiatus.

‘…On Sunday [14 May 2023], the first KRG Council of Ministers meeting involving the PUK ministers, including Deputy Prime Minister Qubad Talabani, took place, where the cabinet unanimously approved a project aimed at centralizing revenues, expenditures, and salaries across the Kurdistan Region. The PUK’s return comes as the Kurdistan Region approaches its long-anticipated parliamentary elections.

‘…The Kurdistan Region’s parliamentary elections are set to be held on November 18, over a year after the originally scheduled date, as the vote was postponed due to continued disagreements between the blocs over the current electoral law and the electoral commission.’[footnote 51]

13.2 Gorran and the KDP

13.2.1 In November 2019 an article entitled ‘Protests and Power: Lessons from Iraqi Kurdistan’s Opposition movement’ written by Zmkan Ali Saleem and Mac Skelton was published by the LSEMNC. The article stated:

‘After the 2013 elections, the party [Gorran] decided to join the government in alliance with the KDP, which granted them several key positions both in parliament and the executive branch, including the Speaker of the Parliament as well as the ministries of Finance, the Peshmerga, Industry, and Religious Endowments. Gorran’s stated objective in joining the government was to implement a reformist agenda from within, focusing on ending corruption, disassociating party politics from government institutions, and reforming the peshmerga units loyal to the KDP and PUK into a united state force.

‘This strategy failed dramatically from the beginning. Over two decades of rule, the two dominant parties had consolidated power and loyalty across the four ministries now under Gorran’s control, particularly the finance and peshmerga portfolios. Decisions made at the top level by Gorran-backed ministers would simply not be implemented whenever they contradicted KDP and PUK priorities. The Ministry of Finance – an institution almost entirely controlled by the KDP – provided no space for the Gorran minister to function, ultimately forcing him into such a weak position that he decided to align with his masters. In 2015, the KDP essentially sacked all the Gorran-affiliated ministers. Later in 2017 the KDP re-employed the finance minister, who was now entirely disavowed by Gorran.’[footnote 52]

13.2.2 The August 2016 article published by the Washington Institute provided further information on the breakdown in relations between the KDP and the Gorran movement:

‘The main trigger for this fallout came when Gorran led an effort in June 2015 to introduce a number of bills amending the presidency law of Iraqi Kurdistan when Barzani’s term was nearing its end. The KDP saw this as an attempt to undermine Barzani, and consequently its relations with Gorran went sour. The law was never amended. A governmental body later extended Barzani’s term despite strong protest from Gorran and some smaller parties. When in October of the same year KDP’s offices in Sulaymaniyah province came under attack by protesters causing at least five fatalities among KDP supporters and protesters, Barzani’s party blamed Gorran for the assault on its offices. In an unexpected twist, the KDP then blocked Gorran’s speaker of Kurdish parliament and five of the group’s ministers from entering Erbil in October 2015 ending Gorran’s participation in the Kurdish government institutions. That led to a divorce between the two sides and brought an end to an uneasy partnership that had started in 2014 when the KDP, as the largest bloc in the newly-elected Kurdish parliament, picked Gorran over the PUK as its major partner in the new coalition government.’[footnote 53]

13.2.3 The LSEMNC article published in November 2019 further stated:

‘The most important long-term result of Gorran’s decision to join the government [in 2013] was the shift in the party’s relationship with existing forms of power and patronage. With the rhetorical and institutional firewall between the reformists and the duopoly removed, Gorran soon fell prey to various forms of co-optation by the PUK and KDP. This process started to generate fault lines between various factions of the party. The illness and ultimate death of Gorran’s leader in 2017 intensified the struggle to breaking point.

‘One faction rallied around Mustafa’s two sons, who had inherited the party’s properties, offices, and media outlets. This faction was soon regarded as anti-reformist and conservative, seeking to push the party towards a more traditional establishment role – and the material and economic benefits that come with it. According to former members of Gorran and independent observers in the KRI, the party has been granted access to lucrative businesses and public projects by the PUK and KDP, all the while maintaining the rhetoric of reform and combating corruption. The other faction strongly rejected the party’s adoption of succession, family rule and nepotism. These members wanted to preserve the ideological purity and reformist objectives of the movement. Ultimately they failed to do so – Mustafa’s sons and their allies won the political battle to control the centre of decision making in the party.

‘For many of the Gorran faithful, this shift in the structure of power essentially transformed the party from a reformist movement to what a former Gorran leader called “a traditional/conservative party similar to the KDP and the PUK.” By any measure Gorran’s current leadership has moved away from its original anti-establishment stance. After suffering a dramatic defeat in the 2018 elections and only gaining 12 seats in the regional parliament, the party nevertheless decided against forming an opposition, joining the KDP-dominated power sharing government while giving lip service to holding the system accountable. Given previous failures to effect change from within, this decision has intensified questions around the aims of the party.’[footnote 54]

13.2.4 In February 2019 Kurdistan24 published an article entitled ‘KDP, Gorran ink deal on government formation as PUK boycotts return to Parliament’ which stated:

‘The Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Change (Gorran) Movement on Monday officially signed their agreement over the formation of government, hours ahead of a parliamentary session that is expected to vote in the body’s leadership.

‘…Following the [September 2018] election, the KDP, in first place with 45 seats, entered into negotiations with both the PUK, the runner-up with 21 seats, and Gorran to form a new government. The stated goal is for a representative government that will address the needs of the people of the region, who have lived through a trying number of years with no financial security.

‘At the end of multiple rounds of negotiations that began late last year, the KDP and Gorran recently drafted an agreement that encompasses the political agenda of the two parties for the next four years. The negotiation committees of the two parties then passed the draft deal to their leadership, and late Sunday [17 February 2019], Gorran finally approved it.

‘On Monday [18 February 2019], the two parties officially signed the strategic agreement, which is likely to end the disputes between the two parties as they form a new government.’[footnote 55]

13.2.5 In January 2020 Kurdistan24 published an article entitled ‘Kurdistan’s Gorran party to meet KDP on government performance, reform efforts’ which stated:

‘…Tensions decreased between the KDP and Gorran ahead of the 2018 elections and the two arrived at multiple government formation deals following the vote.

‘The party [Gorran] is currently part of the new Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) cabinet, holding five ministerial posts: Minister of Peshmerga, Finance and Economy, Housing and Reconstruction, Labor and Social Affairs, and Trade and Industry.’[footnote 56]

13.2.6 On 15 May 2023, NRT English, a translated Iraqi/Kurdish news site[footnote 57], published a report entitled ‘Gorran’s Response To KDP-PUK Rapprochement’, which stated:

‘Gorran, the former opposition party, used to be a vocal critic of the KRG’s ruling parties, particularly the KDP, which they accused the PUK, their parent party, of cozying up to. Now, Gorran is walking a tightrope as a junior KRG partner and as part of a coalition with the PUK formed during Iraq’s last election in 2021.

‘…Despite their smaller stature and potential loss in the next regional elections, rumors of Gorran dissolving and rejoining the PUK ranks are unlikely to come to fruition under PUK leader Bafel Talabani’s leadership due to Gorran’s historical criticism of family rule. Without forming alliances, Gorran is expected to lose seats to other opposition parties.’[footnote 58]

13.3 Gorran and the PUK

13.3.1 The August 2016 article published by the Washington Institute stated:

‘The PUK and Gorran signed a deal on May 17 [2016] whereby they agreed on a joint action platform that will bring the two parties together in the Kurdish and Iraqi political arenas. While the PUK, led by former Iraqi president Jalal Talabani, has been part of the Kurdish establishment, Gorran has often presented itself as an anti-establishment party. The agreement between the two parties is not only important because it ends nearly seven years of hostile relationships between the two sides, but is likely to present a counterweight to the KDP, which is led by Iraqi Kurdistan’s acting President Masoud Barzani. It will also mean the effective termination of a so-called “strategic agreement” that turned the former foes, KDP and PUK, into allies for a number of years.

‘…Having grown fearful of the perceived domination of the KDP over Iraqi Kurdistan’s affairs, the PUK’s primary motive behind allying with Gorran serves to counterbalance the KDP. As two senior PUK officials put it, their party’s aim is to restore the balance of power in Kurdistan – not to undermine the KDP.

‘As for Gorran, having been forced out of government institutions in a humiliating and illegal manner by the KDP, the decision to join forces with the PUK was the party’s only way of remaining a relevant actor in the treacherous waters of Kurdish politics. As Mohammed Tofiq Rahim, a high-ranking Gorran official, put it, the deal was their best shot at “stopping KDP’s unilateralism and re-establishing a balance” in Kurdistan’s political system. Gorran’s populist politics and constant efforts to harness popular disgruntlement to its advantage have brought it into confrontation with the KDP and PUK time and again over the past several years. The deal with the PUK is a sign that Gorran leaders, in particular General Coordinator Nawshirwan Mustafa, have realized they cannot achieve much in the long run if they are not part of a larger political structure. As the second most popular party in Kurdistan’s 2013 elections, Gorran brings a large popular voting base while the PUK provides military support given its sizable Peshmerga and security forces.

‘…The mere fact that Gorran chose such a strategic alliance with the PUK is an admission of failure in bringing about change through conventionally democratic means in Kurdistan. As senior PUK official Farid Asasard said, “If Gorran could have been successful on their own, they would not have entered into this agreement.”’[footnote 59]

13.3.2 For more information and details about the deal between Gorran and the PUK see the full Washington Institute article.

13.3.3 In December 2017 an article entitled ‘Iraqi Kurdistan’s Gorran party withdraws from government after protests’ was published by Middle East Eye and stated that following demonstrations over the KRG’s handling of the fallout from the September 2017 independence referendum and the announcement of budget cuts:

‘The second largest party in the Iraqi Kurdish parliament has withdrawn from the government as protests continue to rock the statelet.

‘The Gorran movement, along with the smaller Kurdistan Islamic Group, both withdrew their ministers from the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) coalition, while Yousif Mohammed Sadiq - speaker of the parliament and Gorran member - also resigned from his position.

‘Gorran also announced it would be ending its “strategic” pact with the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), which they accused of using force in the two parties’ stronghold of Suleimaniyah.’[footnote 60]

Section 10 updated: 29 June 2023

14. Treatment of opponents to the KRI authorities

14.1 Arrests and detentions

14.1.1 In May 2020 HRW published an article entitled ‘Kurdish Authorities Clamp Down Ahead of Protests’ which stated:

‘According to a journalist and two teachers from the city of Duhok in Iraq’s Kurdistan Region, KRI government employees, including teachers, have not received salaries since February, reportedly because of crashing oil prices and the economic fallout from Covid-19. Delayed salaries have been a persistent issue since 2015, triggering protests that Kurdistan authorities regularly meet with arbitrary arrests.

‘On May 13, a group of mostly teachers submitted a request to the Dohuk governor’s office to hold a protest on May 16 calling for salaries to be paid. The requirement to request permission to protest – which conflicts with international law’s protection of the right to peaceful assembly – stipulates that if authorities do not respond to the request within 48 hours, permission is automatically granted.

‘On May 15, the governorate posted a statement on its Facebook page saying it had seen “propaganda and calls for a protest” but that there was no permission for the protest and threatened “legal consequences” if it proceeded. But it did not actually respond to the formal request, a protest organizer said, nor invoke Covid-19-related restrictions as a reason for not granting permission.

‘On May 16, security forces set up checkpoints and barriers to close off the park designated as the protest location. On May 15 and 16, security forces arrested dozens of protesters – at least two from their homes and many more who turned out on May 16. They also arrested at least eight journalists. Authorities released most of those arrested within five hours, but only after preventing this most recent attempt to peacefully protest.

‘On May 19, Dr. Dindar Zebari, the regional government’s coordinator for international advocacy, acknowledged that the arrests were for “organizing unauthorized demonstrations” and justified the arrests by stating that the protests had violated Covid-19 prevention measures, even though local authorities had lifted almost all movement restrictions and did not mention any gathering restrictions at the time.’[footnote 61]

14.1.2 In May 2020 Amnesty International (AI) published an article entitled ‘Police arrests teacher and protest organizer’ which stated:

‘Badal Abdulbaqi Aba Bakr Barwari has been working as a teacher in Duhok for over 27 years and is an activist defending teachers’ rights, most recently in relation to the delayed payment of wages of teachers in the KRI.

‘On 16 May 2020, teachers and civil servants attempted to gather in Azadi Park in Duhok to protest the delayed payment of salaries by the KRG authorities. Protesters told Amnesty International that security forces as well as armed men in civilian clothing blocked the protesters from reaching the park and immediately began to push and drag some of them away. At least 167 protesters, among them teachers, civil servants, and media workers were arrested. Most were released on the same day, but Badal and at least 12 others remained in detention. Of those 12, five remain detained after local authorities brought forward charges under the Article 2 of KRI Law No. 6 of 2008 for the “the misuse of electronic devices” for their role in organizing the protest.’[footnote 62]

14.1.3 In July 2020 AI provided an update on Barwari’s case and stated: