Investigation into bus fires reported to DVSA from 2020 to 2022

Published 20 July 2023

Applies to England, Scotland and Wales

Executive summary

In recent years, the number of bus fires the Driver and Vehicle Standards Agency (DVSA) has dealt with has increased. There has been a number of high-profile bus fires which have led to media and stakeholder attention.

While not resulting in injuries, the fires have naturally raised people’s fears over the possibilities of what could happen if such fires happened while carrying passengers.

Buses have an arduous life cycle with short stop and start journeys, variations in loading and are often subjected to traffic congestion. While buses have a rigorous maintenance programme taking into account their use, there is still the possibility some components may fail prematurely which lead to breakdown or even result in a vehicle fire.

To comply with air quality rules, in recent years buses have been fitted with exhaust after treatment systems that generate significant heat. Concerns have been raised whether the heat generated by these systems could cause premature degradation to components such as wiring, fuel systems and other combustible components within the engine bay.

Bus operation falls mainly into 2 categories, those which are:

- operated commercially under an operator licence

- used for private or non-commercial use

DVSA monitors the operator licence scheme, which requires operators to manage and maintain vehicles to a set standard.

Licenced public service vehicle operators must report vehicle fires to DVSA. DVSA analyses the information available from these operators to understand causes of fires and see if any trends can be identified.

DVSA’s vehicle safety branch has looked at the reported vehicle fires and conducted an engine bay temperature assessment on a number of vehicles. This is to understand if there are any trends or concerns which could be addressed and help reduce bus fires.

Summary of findings

The study broadly found 3 main outcomes:

- DVSA could find no evidence that engine bay temperatures lead to premature degradation or engine fires when maintained correctly.

- DVSA found evidence that showed repairs carried out to address an initial fault were often focused on the fault, and not the effect the fault may have had on other systems.

- DVSA found evidence of drivers continuing to drive the vehicle when warning systems advise the vehicle should be stopped, and of drivers being given incorrect advice by depots to continue driving.

In concluding these findings, DVSA has worked with bus industry representatives and the Confederation of Passenger Transport (CPT) to agree a way in which DVSA and industry can work together to learn and spread best practice to the wider industry to help reduce avoidable future fires.

1. Scope of study

This study intended to help DVSA work with bus operators and understand if there are trends in the causes of bus fires that can be identified. It looked at the reports which were submitted to DVSA either through incident reports or safety concerns raised with DVSA’s vehicle safety branch.

The study considered reports submitted from January 2020 to September 2022.

The study also surveyed a number of buses using temperature logging equipment to assess engine bay temperatures while in operational use, to understand if the engine bay temperatures were higher than expected and a possible cause of vehicle fires.

The engine bay temperature assessment commenced in December 2021 and continued until September 2022. Conducting this assessment over this period allowed for the effect different ambient conditions may have on the engine bay temperature.

The study considered the following areas:

- study of reported fires to DVSA and the findings from these

- the procedure to report fires to DVSA

- maintenance requirements of the vehicles and manufacturers’ schedules

- concerns of engine bay temperatures raised within the industry on the possible cause of the fires

- drivers training and awareness

- casualties and injuries resulting from bus fires

The purpose of the study is to:

- identify any trends which lead to or cause bus fires

- validate the findings from the study with the bus industry

- agree with the industry how best to learn any lessons which may be identified to reduce avoidable bus fires in future

In this report, bus fires are defined as any fire or thermal incident of a service bus in operation. Those bus fires may or may not have been whilst carrying passengers. The risk to safety is dependent on the situation and environment in which a fire occurs.

Fires or thermal incidents caused in workshop or similar repair situations, for example caused during welding, are not included as part of this study.

A ‘normal maintenance type’ breakdown of the bus would not be considered within the scope of this study. However, if the breakdown leads to a vehicle fire then it has been included.

2. Reported bus fires

2.1 Reported bus fires

DVSA reviewed reports received since January 2020 about fires and thermal incidents. The review included more than 240 fires and thermal incidents. Not all these incidents will have occurred when in passenger service. A proportion will not have presented any danger to members of the public.

Reports of bus fires sent to DVSA

There is only data for part of the years 2019 to 2020 and 2022 to 2023. If the 2022 to 2023 year continues the current trend, the final number of reports is likely to be similar to the previous year.

| Financial year | 2019 to 2020 | 2020 to 2021 | 2021 to 2022 | 2022 to 2023 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 25 | 63 | 101 | 53 | 242 |

Reports of bus fires sent to DVSA, categorised by cause of fire

| Cause of fire | Description | Number of reports |

|---|---|---|

| Engine failure | Fires that have happened due to engine failure, such as internal engine failure leading to oil escaping. | 29 |

| Maintenance or repair issues | Fires caused by corrective maintenance taking place without considering other affected components. For example, a coolant leak rectified without considering the effect overheating may have had on other components. | 29 |

| Electrical faults | Where the cause of fire was due to cables which may have chafed, cables overloaded or associated fitment errors. | 38 |

| Vehicle component | Fires that have started in ancillary components like alternators or additional aftermarket components fitted to the vehicle. | 46 |

| Arson or external cause | Fires caused by external factors such as ticket bin catching fire due to discarded cigarettes. Numbers are low, so DVSA cannot determine trends in this area | 6 |

| Fuel | Fires caused by fuel leaking. | 6 |

| Cause unknown | The bus operator was unable to determine the cause of the fire. | 88 |

| Total | 242 |

The number of cases categorised as “arson or external cause” or “fuel” has been low. So it is not possible to identify trends or draw meaningful conclusions from this.

However, the number of reports received where the cause has been identified as unknown is concerning.

2.2 Overview of cases reported to DVSA

Engine failure

A number of reported engine failures have occurred with the connecting rods separating from the crankshafts and breaking through the engine block. This has then caused engine oil to spill onto the hot exhaust triggering a fire.

There have also been reports of drivers over-revving engines, particularly on downhill stretches where the vehicle has reached a fast enough speed that the driver does not need to press the accelerator.

Maintenance or repair issues

In addition to engine failure, incidents that have been categorised as maintenance related include situations where drivers have been:

- aware of temperature warning lamps but have continued to drive

- advised by the depot to return to base instead of having the inconvenience of going through a vehicle breakdown and recovery

Operators and their staff need to understand that running public service vehicles at extreme high temperatures without engine coolant can:

- lead to engine failure

- damage to electrical or fuel components which can cause a fire

Electrical faults

The information provided to DVSA about electrical related fires points to a large number being attributed to cables chafing or rubbing through and causing a short circuit.

None of these rubbing or chafing incidents have been identified as a manufacturing issue. They have been due to maintenance and repair.

Vehicle component

Vehicle component related fires include causes such as failure of the:

- alternator

- starter motor

- turbo charger

- oil pipe

There were also 8 thermal incidents caused by vehicle brakes with seized calipers.

While there have been concerns around aftermarket aftertreatment emissions systems, only 2 incidents have been attributed to these components.

Cause unknown

The fact that the cause was not established in over a third of reported incidents is concerning.

In a sample of 30 fires reported through the online form over a 6-month period with causes unknown, 24 of them have not had a fully completed investigation report submitted to DVSA.

While a vehicle may be totally destroyed with little evidence, operators should still look into possible causes and reasons for the fire.

2.3 Vehicle fires by age

While it is hard to draw specific conclusions why age could be a causal reason for vehicle fires, it is interesting to note that the older the vehicle, the number of reported fires increase.

| Vehicle age | Number of vehicle fires |

|---|---|

| 1 to 4 years | 20 |

| 5 to 9 years | 62 |

| 10 years or older | 155 |

| Unknown | 5 |

| Total | 242 |

Vehicles recorded as over 10 years or older

Many bus fires that fall into the scope of this bus study are fires on vehicles listed as 10 years of age or older. However, there are many contributing factors to these incidents.

Of the 155 listed in this category the reported reasons for failure are shown in this table.

| Cause of fire | Number of vehicles |

|---|---|

| Electrical fires | 23 |

| Engine failure | 22 |

| Component failure | 32 |

| Maintenance | 13 |

| Fuel | 6 |

| Arson | 4 |

| Cause unknown | 55 |

| Total | 155 |

2.4 Other bus fires

The Home Office reports bus fires that have been attended by fire services in England. These numbers are higher than those reported to DVSA. The data provided by the Home Office does not differentiate between vehicle types or use.

These figures will include minibuses and those used for private use as well as those operated commercially under the operator licence system. This will partially explain the disparity between the fires reported by the Home Office and those reported to DVSA. The disparity may partly be because of underreporting to DVSA.

Data is available about fires in other parts of the UK:

2.5 Reporting accidents including fires

Licenced public service vehicle operators must report accidents and vehicle fires which take place on their vehicles to DVSA.

They can report them using an online form.

Operators can either:

- report an incident involving your organisation’s bus or coach

- report an incident if you’re a DVSA earned recognition operator

The form is designed to check that information has been provided and does not allow submission unless fully completed. This helps ensure that the correct information is gathered, so DVSA can make an informed decision on the next action.

2.6 Timeliness and content of report submissions

It’s important that reports are submitted as soon as practically possible following an incident so that the best quality evidence is gathered as close to the incident as possible.

Sending reports quickly enables DVSA to analyse the available information. It also allows DVSA to request further information while the vehicle is available and the incident remains fresh in the minds of those involved.

To help gather as much information as possible when the report was received, during the study further questions were sent to the operator to better understand the events of the incident.

DVSA will explore improving reporting processes and will consider the requirements and needs for operators and DVSA.

3. Regulation and bus design

Since October 2011, new buses and coaches have been subject to harmonised international standards developed through the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe.

These standards continuously evolve in recognition of technical developments to improve safety. The latest versions include provisions for fire protection with regards to:

- the engine compartment, including an automated fire suppression system

- electrical equipment and wiring

- batteries

- fire extinguishers

- fire detection systems

- material flammability

Some of these systems may only be active whilst the vehicle is in operation and use materials that are inherently resistant to burning or which have been treated to enhance their fire-resistant properties.

The regulations contain detailed requirements for the number, position, size, and functionality of emergency doors and exits to address the ease and speed of vehicle evacuation in the event of an accident or fire.

The Individual Vehicle Approval (IVA) inspection manual lists how these standards and regulations must be applied when putting a bus into service.

The Vehicle Certification Agency is responsible for type approval of large-scale production vehicles. DVSA carry out individual vehicle approval for vehicles that do not fall into this category.

3.1 Examples of IVA requirements which consider risk against fire

The vehicle must have no flammable material, and/or material likely to become impregnated with fuel, lubricant or other combustible material within the engine compartment, unless the material is covered by an impermeable sheet.

The accumulation of fuel, lubricating oil or any other combustible material in any part of the engine compartment, must be prevented.

A heat resisting partition must be fitted between the engine and rest of vehicle.

Parts of the vehicle that are used in conjunction with the partition, such as fixing clips or gaskets must be fire resistant.

A heat resisting partition must be fitted between a heat source other than the engine and the rest of the vehicle.

Any heating device (operating other than by hot water) inside the passenger compartment must be encased in material, designed to resist the temperatures generated by the device.

Flammable material within 100mm of the exhaust system, any high voltage electrical equipment, or other significant source of heat, must be adequately shielded.

Exhaust system or other significant heat sources must have adequate shielding to prevent grease or other flammable materials contacting them.

4. Maintenance of vehicles and manufacturers’ schedules

It’s important that manufacturers’ maintenance schedules are followed correctly, and any necessary work identified is completed as this will ensure the correct and continued operation of the vehicle.

It is also important that any service bulletins, service campaigns and recalls are completed. This is in addition to the safety checks required by DVSA.

4.1 Guide to maintaining roadworthiness

Regular safety inspections are essential for effective roadworthiness.

DVSA produces the guide to maintaining roadworthiness to help heavy goods vehicle and public service vehicle operators keep vehicles safe to drive. This guidance includes how to:

- carry out daily checks

- carry out safety inspections

- keep vehicle maintenance records

Section 4.1 of this guidance explains the inspection scope and content. Annex 4B provides an example of a typical PSV maintenance inspection sheet.

Items for fire prevention and protection include:

- interior of body, including fire extinguishers

- passenger doors, driver’s doors and emergency exits

- accessibility features

- electrical wiring and equipment

- oil and waste leaks

- fuel tanks and systems

- exhaust and waste systems

4.2 Daily walkaround check

As well as regular maintenance schedules, the daily walkaround check is an essential part of a licenced public service vehicle operator’s maintenance regime.

Section 3 of DVSA’s guide to maintaining roadworthiness details what a driver is expected to do in a walkaround check.

Annex 9 of the guide shows a diagram and lists items a driver should be checking. This includes checking items that relate to fire prevention and protection.

Items for fire prevention and protection covered in the walkaround check include:

- warning lamps

- wheelchair access

- doors and exits

- fuel, oil and waste leaks

- excessive engine exhaust smoke

- fire extinguisher

- emergency exit device

- first aid kit

- driver communication

The guide to maintaining roadworthiness is shared by DVSA during engagement with:

- partner agencies

- industry stakeholders

- maintenance contractors

- operators during new operator seminars and enforcement action

4.3 Additional features

Fire suppression

Many modern public service vehicles use a fire suppression system. While these systems do not prevent fires, they can limit the amount of damage caused. They can also reduce the risk of passenger injury, due to the increased time available to evacuate a vehicle.

Public service vehicle fire suppression systems are generally fitted in the engine bay area of the vehicle. Temperature sensors are fitted, and when a given threshold is exceeded the suppression system is activated.

Most fire suppression systems are fitted after the vehicle has been built and it is important that the manufacturer’s maintenance instructions are adhered to, to ensure reliable operation.

CCTV systems

CCTV systems in themselves do not monitor fires. However, these systems can be used as a good source of information to understand the spread of the fire and events before the fire started.

5. Casualties and injuries resulting from bus fires

When a bus is pictured or filmed on fire, the impression given might be one of grave danger to passengers due to the intensity. It’s more likely that passengers and people have been safely evacuated long before the extreme intensity of a fire has been reached.

From the reports to DVSA during this study, there have not been any reported fire incidents that have resulted in injuries to passengers or others.

It’s reasonable to conclude that the design of a bus allows for a safe evacuation in the event of an accident or fire.

6. Drivers’ influences

Driver or conductor must take all reasonable precautions to ensure the safety of passengers who are on, entering or leaving the vehicle.

Drivers must have received proper training and maintain their Certificate of Professional Competence (CPC). The syllabus includes an element on the assessment of emergency situations including summoning assistance, reaction in the event of fire and evacuation of passengers.

6.1 Typical public service vehicle licenced operator training for drivers

Licenced operators should provide training about evacuation procedures as part of their driving training programme.

Drivers are generally taught that in the event of a fire on their vehicle they should pull over, open the entrance or exit doors and then turn all systems off.

The driver should then evacuate all passengers. They should make sure everyone has been evacuated from the vehicle before they contact the emergency services.

The driver’s priority should always be to turn all systems off and evacuate passengers before any attempt is made to extinguish the fire.

7. Engine bay temperature assessment

Operators have raised concerns that engine bay temperatures may be too high and can have an adverse effect on electrical wiring and components.

The engine runs hot with fuels, oils, and other flammable materials within the engine bay.

Modern buses have rear mounted engines and have emission aftertreatment systems fitted, which generate significant heat. It’s important to make sure all these systems are protected and functioning correctly so that they’re not exposed to excessive heat.

To understand if there is a risk posed by excessive engine bay temperatures, DVSA has carried out a study assessing a number of ‘in service’ vehicles to assess the operating temperature in the engine bay.

7.1 The engine bay temperature assessment programme

The programme of assessment was carried out in 2 phases:

- winter months with low ambient temperatures

- summer months where temperatures are much higher

The study looked at areas of the country:

- where buses had high load capacities

- with rural routes

A separate study also looked at buses operated in London which have high load capacity and are often restricted to slower speeds due to stop-start traffic congestion.

DVSA has carried out 87 data logging exercises in:

- Manchester

- Sheffield

- Wakefield

- Newcastle

- Leicester

- North Wales

- London

The exercise started in December 2021 and was completed in September 2022.

The buses assessed were mainly Alexander Dennis models, but also included Volvo and Wrightbus vehicles.

| Make | Model | Winter phase | Summer phase | Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alexander Dennis | E400 | 17 | 28 | 45 |

| Alexander Dennis | E200 | 6 | 1 | 7 |

| Alexander Dennis | E300 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Volvo | B9 TL | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Volvo | B7 RLE | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Wrightbus | New Bus for London | 6 | 5 | 11 |

| Wrightbus | StreetDeck | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Wrightbus | StreetLite | 3 | 4 | 7 |

| Wrightbus | Gemini | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Wrightbus | SB 120 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 40 | 47 | 87 |

7.2 Approach for the study

The method for assessing the engine bay temperature was to fit data loggers that measure temperature over a period of time. These were then fitted to the bus for a period of 7 days and left in place while the bus was on its normal operational routes. As these were independent of the vehicle they would continue to operate when the bus was inactive.

7.3 Data loggers

All the data loggers were synced with a computer before being fitted to buses. This ensured the time stamp on the data is consistent. They were then installed independently of each other at set locations in each vehicle.

Each logger records the time and the temperature at that point. The elapsed period for which the temperatures are recorded can be varied for this exercise. The temperature readings were taken every 20 seconds. While fitted to the vehicle, the data loggers store information, which is downloaded later.

Data logger used in the exercise

The logger has a removable cap for plugging into a PC via a USB connection. It also has a cable which connects the probe to the data logger. This allows the probe to be fitted close to the temperature source while allowing the logger itself to be placed in a more suitable area.

7.4 Location of the data loggers

Four loggers were fitted to each vehicle. The loggers were fitted:

- at the front of the vehicle to monitor the ambient temperature

- close to the cooling system to establish engine temperature

- at the top of the engine bay

- above the emission after treatment system

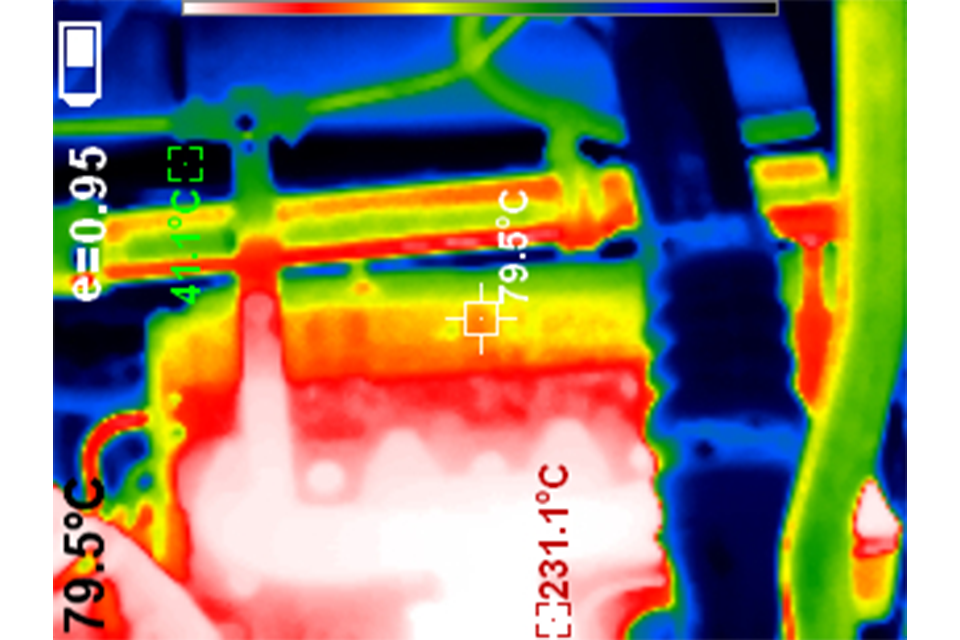

To optimise the location of the temperature probes a heat-seeking camera was used to establish the hot spots. Images from a heat-seeking camera use different colours to show temperatures.

Zoomed-in heat seeking image directed at the after treatment on the engine.

7.5 Example of data provided by the loggers

The charts below show examples of how the data is presented over the 7-day period from a single and combined loggers.

You can clearly see:

- when the vehicle is in use the temperature rises

- when the vehicle is back in the depot overnight the temperature drops

On the combined chart, you can see the ambient temperature has little effect on the engine bay temperature.

These graphs are typical of the findings from all vehicles checked.

Example of data provided by the loggers that shows when the vehicle is in use the temperature rises.

Example of data provided by the loggers that shows the ambient temperature has little effect on the engine bay temperature.

7.6 Regional difference

It has been suggested that regional difference such as ambient temperature, increased loading or usage, speed and congestion may influence engine bay temperature.

The graphs below take a snapshot of the data from a single day from Newcastle and London.

You can see when the vehicle is being used and then when parked up overnight.

Bus in Newcastle

This chart shows a bus from the Newcastle area. It shows the temperatures within the engine bay show similar readings. This suggests that the engine runs continually with fewer rest periods.

Bus in London

This chart shows a bus in London. You can see when the vehicle is taken out of service overnight. However, you can see that when the bus is introduced into service the temperature fluctuates greatly over the day.

8. Findings and recommendations from this study

Based on the study of reports sent to DVSA and the evidence found in the engine bay temperature assessment study, DVSA has found that:

- there is evidence that repairs have not been carried out correctly, which have led to vehicle fires

- drivers have continued driving vehicles when warning systems have advised of high temperatures

- there is no evidence that the engine bay temperatures are excessive or exceed manufacturer’s limits when a bus is running correctly

The conclusions from this study have been shared with the industry, the Confederation of Passenger Transport (CPT) and DVSA operational teams.

8.1 Vehicle maintenance and repairs

This included:

- normal maintenance

- servicing

- additional repairs identified while in service

Vehicle maintenance and repairs: findings

DVSA found that:

- there was no evidence to suggest that vehicles are not undergoing safety inspections at the prescribed times

- some reports have identified incorrect repair procedures which have not taken into account the effect on other components

- often when a fault is fixed, for example, overheating, no consideration is given to what else may have been affected by the fault

- incorrect repairs can be completed, such as heat shields left off or incorrect routing of cables and fuel lines

Vehicle maintenance and repairs: conclusion and recommendations

It is clear when a vehicle has overheated, in addition to fixing the fault, consideration needs to be given to the degradation effect the overheating may have caused. Often the damage caused is irreversible and this can lead to future or premature failures or even fires.

DVSA recommends that:

- full access is available to technical information from the manufacturer on the maintenance and repair of vehicles

- all service instructions and bulletins which apply to vehicles should be completed

- any outstanding recalls must be completed

- repairs and servicing should be signed off as complete by a trained and competent person

8.2 Drivers’ influences

The driver is the person who is in control of the vehicle at the time of the incident. It’s important that the driver fully understands all aspects and features of the vehicle they’re driving.

When a fault has been identified while the bus is in service and the depot are providing advice, they should not assume that the driver has the technical knowledge to interpret the instruction correctly.

Drivers’ influences: findings

DVSA found that:

- drivers have driven vehicles with warning systems telling them not to

- drivers have driven vehicles under instruction from the depot with warning systems telling them not to

- drivers have not always been clear on the evacuation procedures for the particular vehicle they are driving

- drivers may not take the correct action at the start of a thermal incident

- very rarely is the driver interviewed to understand the events leading to a thermal incident

Drivers’ influences: conclusion and recommendations

Drivers are often with the vehicle when a thermal event takes place and are the main source of information to understand events leading up to the fault and event.

It’s extremely important that the driver is fully aware of the procedure for the bus being driven, so that:

- they can evacuate passengers safely

- they know what to do if there is a thermal event or a fire

DVSA recommends that:

- drivers must understand the warning systems on the bus before they start any journey

- drivers must know how to use emergency equipment in the event of a thermal incident

- drivers must be trained and know the procedures for safe evacuation of passengers on the bus they are driving

- operator staff should not assume the driver has sufficient technical knowledge to ignore warning systems which advise to stop the vehicle

8.3 Engine bay temperature

Engine bay temperature: findings

The data downloaded from the vehicles during the exercise showed engine bay temperatures were not excessive, and recorded temperatures are well within manufacturers design tolerances.

While the variance in ambient temperatures at different times of the year could be seen on the combined reports, this had little effect on the overall engine bay temperature.

Engine bay temperature: conclusion and recommendations

DVSA is unable to conclude the design of the vehicle allows engine bay temperatures to be excessive and the normal operating temperature is well within the safety margins provided by the manufacturer.

8.4 Reporting procedure

Reporting procedure: findings

DVSA found that:

- a number of reports are submitted a long time after the incident has taken place

- some reports are submitted with little or poor information

- often there is no investigation into the root cause of the fire

- the reports do not include evidence of events leading up to the fire

- the reports do not contain witness statements from drivers or those involved while the incident took place

- a significant number of reports are submitted as cause unknown

Reporting procedure: conclusion and recommendations

When reports are submitted as soon as possible after the incident and fresh in the minds of those involved, it helps with understanding the sequence of events and often provides valuable information in the diagnosis of the events leading to the thermal event.

DVSA recommends that:

- all reports should be submitted as soon as practically possible after the incident

- operators should investigate the cause of the fire and produce a report providing the supporting evidence available

- DVSA review submitted reports and where necessary request extra information when an operator reports a thermal incident

9. Next steps

The study has identified a number of areas where a number of bus fires could have been prevented if corrective action, further investigation of faults or correct procedures were followed.

It’s important that the lessons learnt from this study are understood and the recommendations are communicated throughout the industry.

DVSA has worked with industry and the Confederation of Passenger Transport (CPT) and agreed an approach where all parties can work together in a collaborative forum. This will not only apply the recommendations from this study but create a forum that will allow a continual improvement process to be adopted.

The next steps DVSA will take are:

- setting up a forum

- communicating the findings of this report

How the forum will work

The forum will consist of:

- a cross sectional representation of the bus industry

- DVSA operational staff from either the Remote Enforcement Office or DVSA earned recognition teams

- the Confederation of Passenger Transport (CPT).

The purpose of the forum is to look at the recommendation from this report and review ongoing submitted reports which have been provided to DVSA. Any reports shared with the forum will be redacted so not to identify the author of the report.

CPT are the recognised industry body that represents both bus operators and manufacturers. As they are independent, they have agreed to chair and facilitate such a forum.

The forum should meet twice a year. There will be extra meetings if needed.

Standard agenda items should:

- consider issues raised by members of the group and CPT

- consider what should be the best practice to address any issues

- develop and implement a communication strategy for any issue which needs taking forward

- consider communications to the whole industry, not just those with operator licences

Communication about bus fires

DVSA will communicate the findings from the study to the industry to include:

- the need to report all bus fires to DVSA in a timely manner

- the importance of correct maintenance and repairs

- the need to ensure drivers are fully trained and aware of all safety aspect of the bus they are driving

- development of a continual improvement forum where lessons can be learnt, and best practice shared

The communication should also include those who are not within the operator licencing scheme.

Annex A: extra questions for operators that report a thermal incident to DVSA

For this study when an operator submitted a report to DVSA, we asked them for further information on the incident.

Information about the incident

The operator must send DVSA:

- a completed form

- an overview of the events leading up to the thermal event

Information about the vehicle

DVSA asked the operator to provide:

- the location of the vehicle where the fire or thermal event took place

- a report into the cause of the fire

- the current location of the vehicle

- copies of maintenance history of the vehicle for the last 12 months, including repair and servicing

DVSA also asked the operator to provide:

- any obvious, early indications of a root cause

- whether recent and latest driver reports indicate any issues

- the extent of the damage, for example whether the vehicle can be driven or if the engine runs

Information about the driver

DVSA asked the operator to provide:

- an interview of the driver explaining the events as they have happened

- an interview of witnesses if available

- information about whether the driver was given any advice from the depot control room or engineering

Information about occupants

DVSA asked the operator to provide information on whether:

- there were any injuries

- the occupants were evacuated safely