Incentivising SME uptake of health and wellbeing support schemes

Published 15 March 2023

DWP research report no. 1024

A report of research carried out by RAND Europe on behalf of the joint Work and Health Unit (Department for Work and Pensions and Department for Health and Social Care).

Crown copyright 2022.

You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/ or write to:

Information Policy Team

The National Archives

Kew

London TW9 4DU,

Email: psi@nationalarchives.gov.uk

This document/publication is also available on the Research at DWP page on the GOV.UK website

If you would like to know more about DWP research, email: socialresearch@dwp.gov.uk

First published March 2023.

ISBN 978-1-78659-506-5

Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and Pensions or any other government department.

Statement of Compliance

This research complies with the three pillars of the Code of Practice for Statistics: trustworthiness, quality and value.

The following explains how we have applied the pillars of the Code in a proportionate way.

Trustworthiness

This research was conducted, delivered and analysed by RAND Europe, a not-for-profit, nonpartisan policy research organisation with a long and proven commitment to high-quality research, underpinned by rigorous analysis.

RAND Europe worked closely with the joint Work and Health Unit (Department for Work and Pensions and Department for Health and Social Care) to understand the aims of the research, but led on the design, delivery and analysis of the research approach.

The work was undertaken in line with the Government Social Research code of practice, and the large scale survey of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) was undertaken by Accent, a market research agency who sub-contracted to RAND Europe, and are members of the Market Research Society and work to their code of conduct

The authors of this report were all within the employment of RAND Europe at the time of their contributions to the research.

Quality

The mixed-methods approach to this research was carried out using well-established quantitative and qualitative research methods.

The research has been quality assured using RAND Europe’s internal quality checking processes, which have been shared with the Work and Health Unit. The report has been checked thoroughly by Work and Health Unit analysts to ensure it meets the highest standards of analysis and drafting.

Value

This research provides fresh insights into SMEs current activity, their desire to do more, and the current barriers to this. In addition, it provides a quantification of the relative influence that policy leavers could have on what employers say they would do. Findings from this report have informed the ongoing development of policy decisions relating to health and wellbeing support among SMEs.

Executive summary

This research aimed to provide new insight into how incentives might be used to encourage and support SME employers to invest in more health and wellbeing schemes for employees.

The report considers:

- What support are SMEs already providing in this space?

- What do SMEs say prevents them from doing more?

- What kind of interventions would SMEs like to invest in, should greater support to do so be available?

- What impact could a government intervention have in improving uptake?

The mixed-methods approach centred around a discrete choice experiment (DCE) undertaken within a survey of 500 SMEs (with at least 10 employees) in Great Britain. This was supplemented with a series of 30 qualitative interviews to provide more detailed insight into some of the issues identified through the survey.

The research finds that 70% of SMEs surveyed reported they currently provide at least one type of proactive health promotion scheme for all employees, but smaller SMEs generally provide lower levels of support. Provision is often employee led and comes about as a result of requests from staff.

SMEs have an appetite to do more but lack of resources – both money and/or time – are the top barriers to implementation, along with a lack of knowledge about what support to invest in. Support to address issues surrounding musculoskeletal conditions, common mental health problems and the way work is organised or managed were the top three areas in which employers wanted to do more.

The discrete choice experiment, supported by qualitative evidence, suggests that both financial support and the provision of advice and support have a role to play in improving SME uptake of health and wellbeing schemes. With regards to financial support, a greater impact could be achieved by funding a larger group of SMEs at 50% reimbursement than half as many SMEs at 100%.

Navigating the market for these services can be challenging for SMEs and many stated they would not know what health and wellbeing programmes to invest in even if there was financial support. Access to supplementary advice, in the form of a needs assessment and signposting to appropriate health and wellbeing schemes, was observed to have a significant impact on stated uptake in the experiment. Such assistance could help SMEs to deliver on their often-stated desire to help improve the health and wellbeing of their staff.

The risk of “deadweight loss” from SMEs using any financial support to simply subsidise actions that they are currently taking appears low. Both the survey and interviews identified that employers had a desire to do more and intended to use any funding provided to either extend their current provision or move into new areas.

The report concludes with some suggestions for further research to better inform future policy design.

Acknowledgements

The authors at RAND Europe would like to thank the team at the Work and Health Unit (Lisa Schulze, Michael Oldridge, Paige Portal and Karen Taylor) for their guidance and support throughout this project.

Thanks are also due to colleagues at Accent who helped with survey recruitment and fieldwork. We would also like to acknowledge the important contributions of Rob Prideaux who helped lead aspects of the study whilst on secondment to RAND Europe, and Dr Chris van Stolk and Bhanu Patruni who acted as quality assurance reviewers throughout the study.

Last, but by no means least, the authors would also like thank all the employers who took part in the research.

The Authors

This report was authored by researchers at RAND Europe:

- Peter Burge (Operations Director)

- Hui Lu (Senior Analyst)

- Pamina Smith (Analyst)

- Nadja Koch (Research Assistant)

Glossary and abbreviations

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Deadweight loss | A measure of lost economic efficiency when the socially optimal quantity of a good or a service is not produced. In the case of this study this would include the use of public funding to pay for activities that are already being paid for in other ways |

| Discrete Choice Experiment (DCE) | A quantitative research method for valuing different factors that influence the choices that individuals or organisations may make. DCEs enable choice alternatives to be broken down into a range of component parts, which are taken into account through the inclusion of a range of different attributes |

| Employee Assistance Programme (EAP) | Helpline and/or other services offered to all employees to provide confidential expert advice when needed; may cover wider health and wider wellbeing issues, such as financial |

| Incentivised action plan | A health and wellbeing financial incentive scheme entailing an action plan aimed at improving the health and wellbeing of employees. An incentive would be paid to the participating company, based on the number of employees involved, in return for an ongoing time commitment from the company over a one-year period |

| Long-term health conditions and/or disabilities (LTCD) | A condition that cannot at present be cured but can be controlled by medication and therapies |

| Musculoskeletal conditions | Conditions that affect the joints, bones and muscles |

| Occupational Health (OH) | Advisory and support services which help to maintain and promote employee health and wellbeing. OH services support organisations to achieve these goals by providing direct support and advice to employees and managers, as well as support at the organisational level e.g. to improve work environments and cultures |

| Reimbursement rate | The proportion of costs of services that might be reimbursed to employers providing health and wellbeing interventions within the scope of a given scheme |

| Small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) | Employers with up to 249 employees. For the purpose of this study we excluded micro employers with less than 10 employees |

Summary

Background

The Health is Everyone’s Business consultation outlined the crucial role employers play in supporting the health of employees. Improved employee health and wellbeing can benefit employees, employers, and the wider economy by reducing ill-health related job loss, sickness absence, presenteeism, and improving productivity.

However, previous research shows that whilst most employers recognise their role, many face multiple barriers to investing in health and wellbeing support, such as lack of expertise, time constraints and cost. There is also wide variation in the support provided by employer size, with small and medium-sized employers significantly less likely to invest in formal health and wellbeing initiatives than large employers.[footnote 1]

The joint Work and Health Unit (Department for Work and Pensions and Department for Health and Social Care) commissioned RAND to research what incentives could be used to encourage and support small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) employers to invest in more health and wellbeing schemes for employees.

Methodology

The research included a quantitative telephone survey with 500 SME employers (with at least 10 employees) in Great Britain, 30 in-depth qualitative interviews, and a discrete choice modelling experiment embedded within the survey.

The survey and interviews explored the main health concerns of SME employers, their current provision of health and wellbeing support, and the barriers to providing it. The survey uses a sampling frame but is not weighted to be representative nationally.

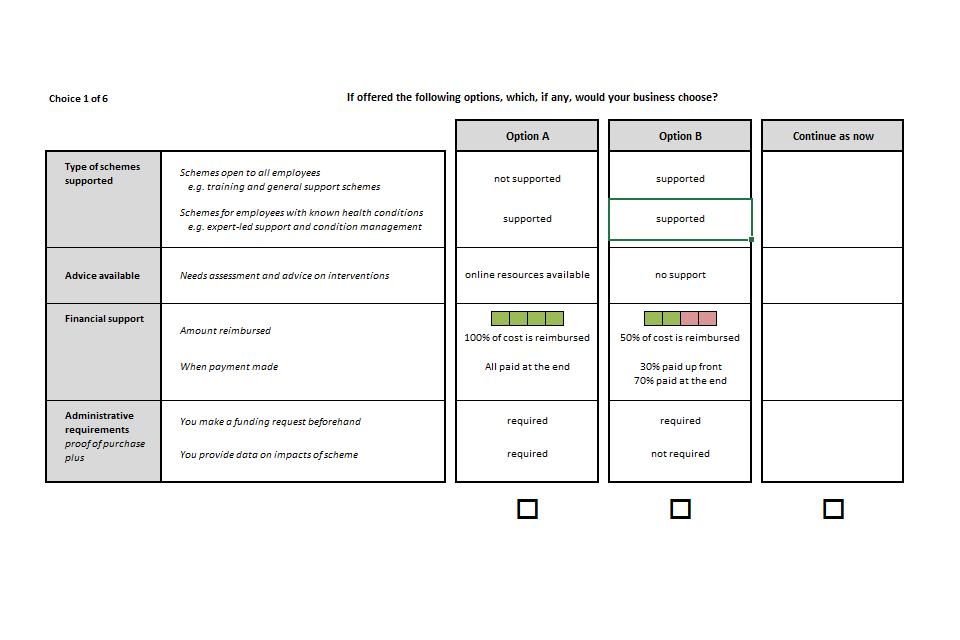

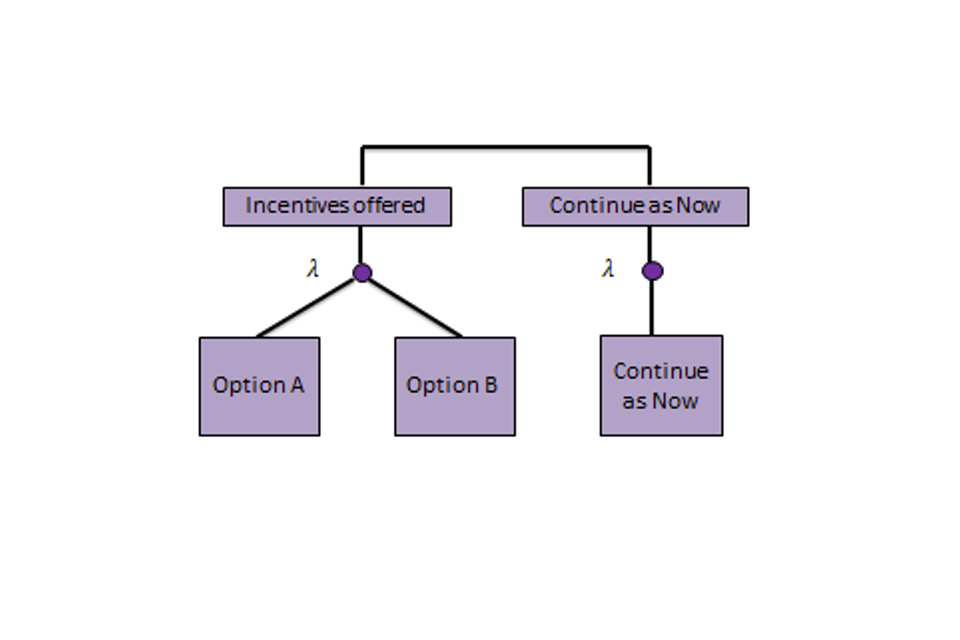

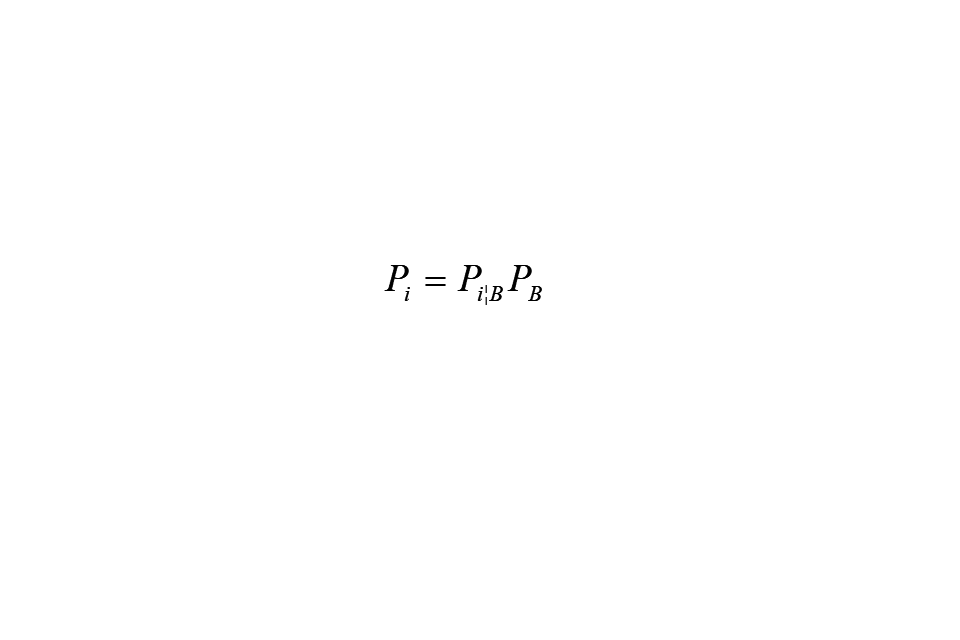

The discrete choice experiment explored the potential uptake amongst SMEs of government-provided financial incentives and signposting advice for health and wellbeing schemes, including the importance of attributes relating to how that support is delivered. Each SME was given a range of hypothetical ‘choice scenarios’. Within each scenario, SMEs were asked to choose between three options; two involving participation in a new health and wellbeing scheme and one ‘continue as now’ option. The health and wellbeing schemes offered were varied in carefully controlled ways by five groups of attributes:

| Attribute | Levels |

|---|---|

| Types of health and wellbeing services in scope for purchase | - Proactive health-promotion schemes open to all employees, i.e. schemes to encourage healthy eating, or stress management - Schemes targeted for employees with health conditions, i.e. occupational health assessments - Both in scope |

| Needs assessment and advice on interventions | - No support available – baseline - Online resources available - Personal advisor available |

| Financial support (% of cost is reimbursed) | - No financial support – baseline - 25% of cost is reimbursed - 50% of cost is reimbursed - 75% of cost is reimbursed - 100% of cost is reimbursed |

| When support payment is made | - All paid at the end – baseline - 30% paid up front and 70% paid at the end |

| Administrative requirements | - Only proof of purchase required – baseline - Proof of purchase plus funding request submitted beforehand - Proof of purchase plus requirement to provide data on impacts of scheme - Proof of purchase plus both |

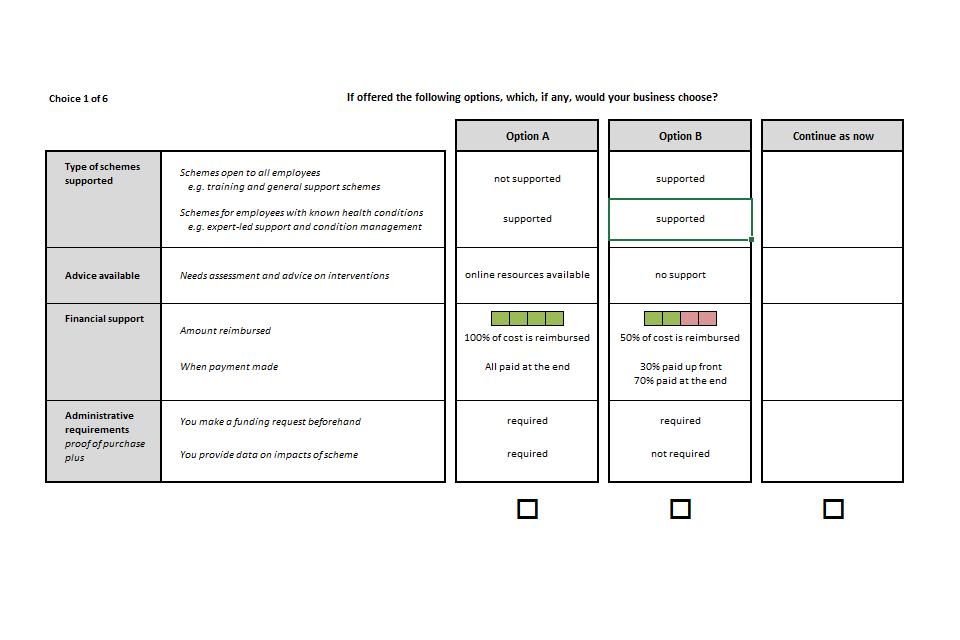

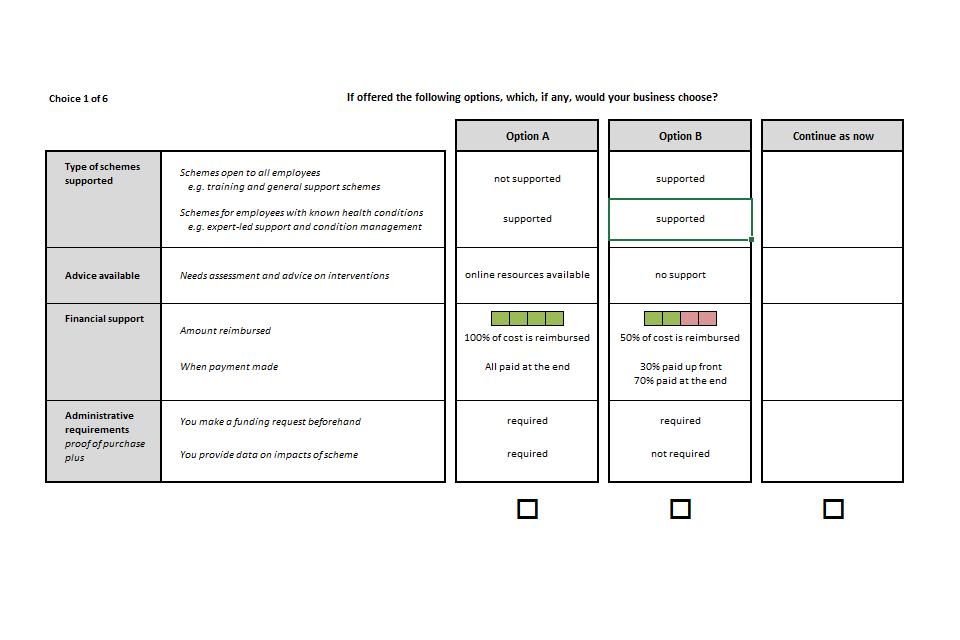

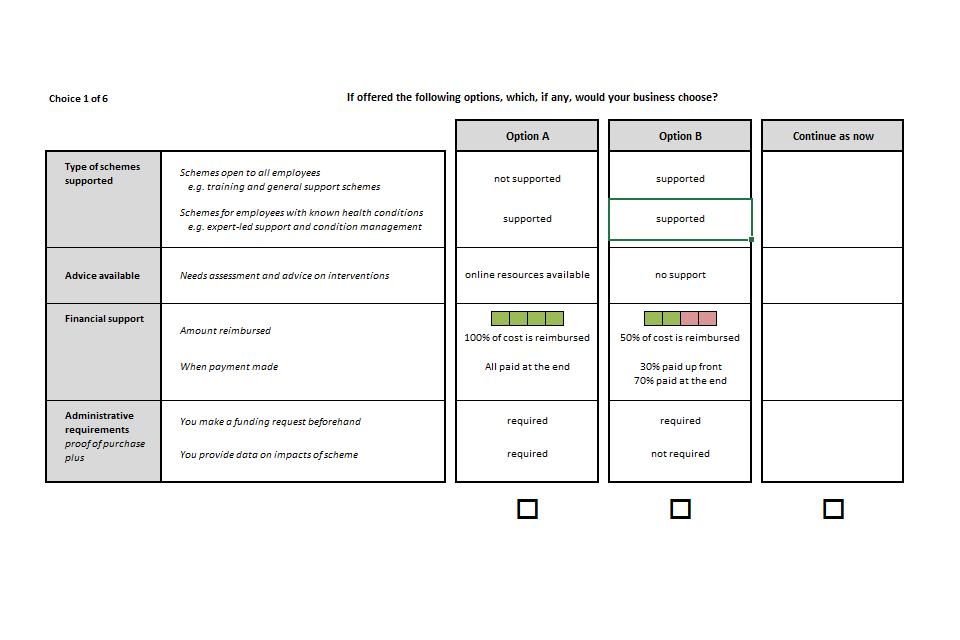

An example of a choice scenario put forward to respondents is below:

Responses were used to model the relative contribution of each attribute level to the likelihood that SMEs would choose a scheme. These were used to illustrate potential SME uptake for schemes with different configurations of attributes. However, it is advised that specific uptake estimates should be interpreted with extreme caution for the following reasons:

- They assume 100% of SME employers are aware of any scheme. In reality, raising awareness of such provision amongst SMEs can be challenging.

- Hypothetical scenarios can only include a limited amount of detail and so may exclude details that in reality might affect the employer’s decision. For instance, two potentially important details not included in these scenarios include:

- Gross costs of health and wellbeing schemes – in reality, cost is likely to influence employer decisions, and it may also influence the relative importance of other factors, such as financial reimbursement rate.

- Time required to fulfil administrative requirements – whilst the DCE explored the impact of different forms of administrative requirement, it did not specifically test the sensitivity of uptake to different time commitments.

- Responses may be subject to social desirability bias, meaning respondents may choose the more socially acceptable answer (i.e. they would provide support) even if it’s not the choice they would make in reality.

- The sample of respondents excluded micro employers (with fewer than 10 employees), who may be less likely to uptake formal health and wellbeing support.

This research was carried out in 2018, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Survey and qualitative interview findings

Key health concerns for employers

When asked about the most important health and wellbeing concerns affecting their organisation, over 80% of respondents reported each of musculoskeletal conditions or mental health problems. This supports previous research which found these to be the two most common health concerns of employers.[footnote 2] They are also the two single most common reasons for sickness absence in the UK after minor illnesses.[footnote 3]

The qualitative research highlighted that concerns about musculoskeletal conditions clustered into two different groups: those that were concerned about low levels of activity at desk-based work along with repetitive movements, and those that were concerned about heavy lifting and physical strain.

Concerns regarding mental health could also be clustered into two groups: those that were aware of the stresses and strains of the workplace, and those that recognised that their staff could have complications outside of work that could also impact on their working life.

Current provision of health and wellbeing support

Employers were asked about two categories of health and wellbeing scheme:

- proactive health promotion for all employees in the workplace, for example schemes to encourage healthy eating, physical activity, or stress management

- support targeted for employees with health conditions, beyond legal obligations, for example Occupational Health assessments, or access to psychological therapy

70% of SMEs reported they currently provide at least one type of proactive health promotion scheme for all employees. This varied significantly by employer size, with only 58% of employers with 10-19 employees providing at least one type of proactive support, compared to 82% of employers with 50-249 employees. The most common types provided were mental health support or training (39%) and help with managing stress (39%).

Similarly, when asked about provision targeted for employees with health conditions, medium employers reported much higher levels of current provision. However, this is to be expected since smaller employers are less likely to have employees with health conditions. For example, previous research found that the most common reason small employers do not provide Occupational Health services for their employees was a lack of employee need.[footnote 4]

Therefore, to explore willingness to provide support, employers were asked both whether they currently provide support specifically for employees with health conditions, and whether they would provide it if an employee need arose. Taking into account this stated willingness to provide support should it be required, the difference by employer size reduces significantly, but a difference does remain.

Qualitative interviews highlighted that smaller employers did appear to have a strong interest in the health and wellbeing of their staff, but they tended to have more of a ‘family’ culture than larger employers and therefore tended to use more informal approaches to handling health problems in the workplace.

Barriers to investing in health and wellbeing

The most common reported barriers to providing health and wellbeing support were lack of expertise to know what support to invest in (49% of respondents), lack of time or resources to implement policies (49%), and lack of capital (52%). This supports previous research which found that lack of time and capital are the main barriers for SMEs in supporting employees to return to work after a spell of sickness absence.[footnote 5]

A theme highlighted in the interviews was that knowing what to invest in is complicated and navigating the market can be difficult and requires a time investment. Some SMEs explained that whilst cost was a key barrier to SMEs, many would not know what health and wellbeing programmes to invest in even if there was financial support.

Discrete Choice Experiment findings

Importance of type of health and wellbeing scheme on SME uptake of support

SMEs were equally as likely to choose a preventative health and wellbeing scheme as they were to choose a scheme targeted for employees with health conditions, but they were more likely to choose a scheme including both types of support than just one.

SMEs with experience of employees with long-term health conditions or disabilities were more likely to choose either type of scheme than SMEs without that experience but they were particularly more likely to choose preventative schemes.

Importance of financial incentives on SME uptake of support, including payment timing

The experiment found that as the rate of financial reimbursement increases, the likelihood of choosing an option increases. However, there are diminishing marginal returns as reimbursement rates increase.

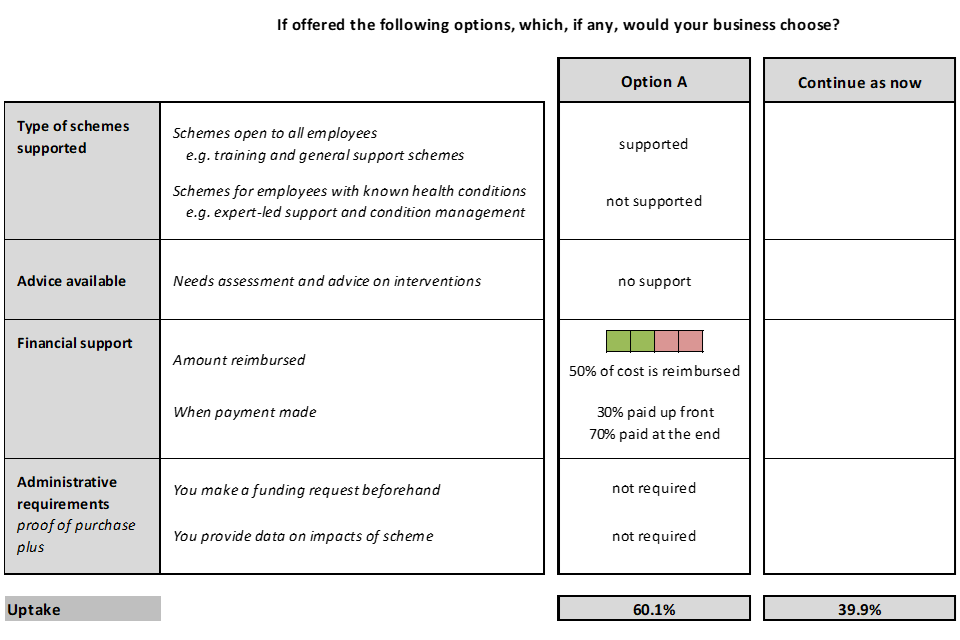

Taking the example of an option that covered both categories of health and wellbeing schemes, where 30% of any financial reimbursement is paid up front and 70% is paid at the end, which includes an online needs assessment and signposting to appropriate schemes, and for which there are no administrative requirements for participating, the experiment estimated that 53% of SMEs who know of the scheme would participate even if there was no reimbursement. If the government offered a 25% financial reimbursement, uptake would increase by 13 percentage-points to 66%, but for each additional 25% reimbursement, the amount by which take up would increase gets smaller. Increasing the subsidy to 50%, then to 75%, then to 100%, would increase uptake by a further 11 percentage-points (to 77%), 5 percentage-points (to 82%), and then 4 percentage-points (to 86%), respectively.

In practice, this means that for a given pool of funding, greater impact could be achieved by funding a larger group of SMEs at 50% reimbursement than half as many SMEs at 100% reimbursement.

To test whether capital, or more specifically cash-flow constraints, were the barrier for SMEs, the experiment varied the timing of the reimbursement payment between having a payment made on delivery, or having 30% paid up front and the remaining 70% on delivery. This had no statistically significant impact on uptake. This finding was generally supported through qualitative interviews, though some SMEs reported that a quick reimbursement following delivery was important.

It is worth noting, however, that information which was not provided in the hypothetical scenarios, such as gross scheme cost to providers, could change the relative importance of the financial reimbursement rate or timing of payment in reality.

This is particularly important given a common theme in the qualitative interviews was that many SMEs appeared to have limited understanding of the costs of health and wellbeing schemes, and many had not seriously considered how much they might be willing to spend. This means that many SMEs made decisions in the experiment without a clear and consistent understanding of the costs to the business.

Importance of supplementary advice and guidance on SME uptake of support

The choice experiment tested whether supplementary advice and guidance would increase uptake of the support package. This was described as an upfront needs assessment to help SMEs better understand staff health needs or on how to source or implement best-practice schemes to address those needs. The experiment varied whether this advice was delivered through access to online resources or access to a personal advisor.

The provision of supplementary advice had a statistically significant positive impact on uptake of the support package. However, on average there was no statistically significant difference between whether this support was delivered online or by a personal advisor. Model forecasts show that by taking the same option as expressed in the previous section but holding the rate of financial reimbursement fixed at 50%, the availability of online resources or a personal adviser would increase SME uptake by 7 to 8 percentage-points compared to if no advice was available.

The qualitative interviews showed a mix of preferences, with some employers strongly preferring online advice and others preferring a personal adviser.

Importance of administrative requirements on SME uptake of support

Including additional administrative requirements for employers to participate in a scheme had no statistically significant impact on the likelihood of employers choosing that scheme. However, in the qualitative interviews, many SMEs emphasised that any administrative requirements needed to be proportionate to the funding and support being provided. This indicates that whilst the experiment did not detect an impact, excessive and disproportionate administrative requirements could still have an impact on uptake.

Conclusions

Findings from the survey and qualitative interviews were consistent with other research. Medium-sized employers are more likely than small employers to invest in formal health and wellbeing initiatives for their employees. For support specifically to manage existing health conditions in the workplace, this difference by employer size reduces significantly when taking into account whether SMEs would be willing to provide the support should an employee need arise, yet a difference does remain. The most common barriers to SMEs providing health and wellbeing support were lack of expertise to identify initiatives, lack of time to implement, and lack of capital to invest in them.

The experiment, supported by qualitative evidence, suggests that the following could be effective at improving SME uptake of health and wellbeing schemes:

- Financial support. However, a greater impact could be achieved by funding a larger group of SMEs at 50% reimbursement than half as many SMEs at 100%.

- Supplementary advice, in the form of a needs assessment and signposting to appropriate health and wellbeing schemes.

1. Introduction

1.1. Policy background

Improved employee health and wellbeing is in everyone’s interests. It can benefit employees, employers, and the wider economy by reducing ill-health related job loss, sickness absence, presenteeism, and improving productivity. In 2017, ‘Improving Lives: The Future of Work, Health, and Disability’[footnote 6] set out an ambitious agenda to transform employment outcomes among people with long-term health conditions or disabilities. The 2019 ‘Health is Everyone’s Business’ consultation[footnote 7] built on this with proposals to minimise the risk of ill-health related job loss, outlining the crucial role employers play in supporting the health of employees.

Existing evidence points towards best practice employer-led interventions that can prevent ill-health, maintain wellbeing, and support the recruitment, retention and reintegration of disabled people or people with health conditions. There is a growing market for workplace health and wellbeing initiatives, from Occupational Health (OH) services, Employee Assistance Programmes (EAPs), access to psychological or physiological therapy, through to workplace cycling schemes and suppliers providing of health and wellbeing training. Workplace health and wellbeing initiatives have the potential to improve both business and health outcomes[footnote 8], hence can contribute to overall public health, productivity and work retention.

However, there is limited empirical evidence on what would encourage employers to implement these interventions or invest in health and wellbeing programmes. The current system to support people with health problems and the responsibilities of different actors (e.g. sick pay) creates a unique system of incentives and disincentives for them to act. Developing the evidence-base on levers that could encourage employer action, particularly for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), is critical in developing policy that will deliver on the overall agenda.

1.2. Wider context

Evidence suggests employers generally recognise their role in supporting employee health and wellbeing, but investment in health and wellbeing is often not considered a priority.[footnote 9] There is also wide variation in the support provided by employer size, with small and medium-sized employers less likely than large employers to state they proactively seek to address these areas and are less likely to provide health and wellbeing services like OH and EAPs[footnote 10]. Many report facing multiple barriers, such as lack of expertise, time constraints and cost[footnote 11]. In addition, they may not consider the positive externalities of improved health and wellbeing support on employees, their businesses, and the wider economy when choosing whether or not to invest in it.

The provision of financial incentives to employers or improved advice about what to invest in have been suggested as possible solutions to improve provision of support for employees. However, internationally, very few studies have looked specifically at the impact of offering financial support for employers to invest in employee health and wellbeing.[footnote 12] Moreover, whilst economic theory suggests that financial incentives or improved advice about what works could help increase health and wellbeing provision, there is still large uncertainty around the optimal level and structure of such policies to encourage action.

1.3. Research aims

This research contributes to the overall understanding of employer decision-making in the work and health space, with a focus on workplace and employer-led prevention of ill-health and health-related job loss, and how and what policy levers should be utilised for encouraging action.

In particular, this research aims to answer the following research questions:

- What support are SMEs already providing in this space?

- What do SMEs say prevents them from doing more?

- What kind of interventions would SMEs like to invest in, should greater support to do so be available?

- What impact could financial reimbursement or signposting advice have on uptake of health and wellbeing schemes, and what is the optimal structure of this intervention?

1.4. Method

The mixed-method approach developed for this research centred around a discrete choice experiment (DCE) undertaken within a survey of SMEs. This was supplemented with a series of qualitative interviews to provide more detailed insight into some of the issues identified through the survey. For more detail on the research design mentioned below, please refer to the appendix. This research was carried out in 2018, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

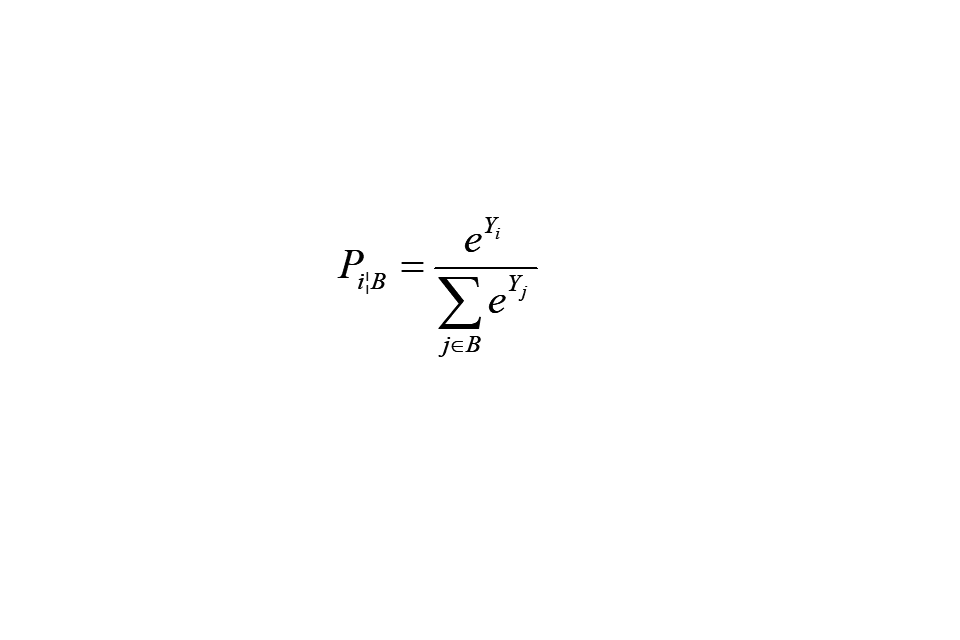

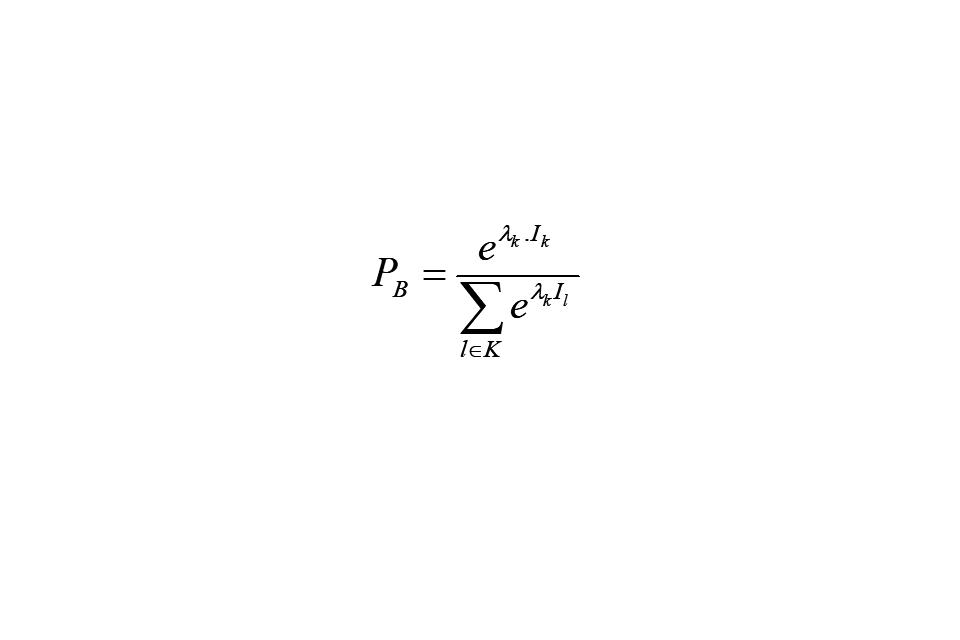

1.4.1. Use of a discrete choice experiment

Fundamentally the core policy questions regarding the possible structure of a policy intervention relate to how SMEs would make choices if faced with different options, and how these choices would vary depending on the alternatives available. Discrete choice experiments provide a research approach that is well suited to such situations. They provide an approach to unpick how different factors influence the choices made by decision-makers. Respondents in a survey are asked to consider a range of different hypothetical choice situations, which differ in carefully controlled ways. The experimental design behind these scenarios means that it is possible to understand the influence of different factors on the choices that they state they would make.

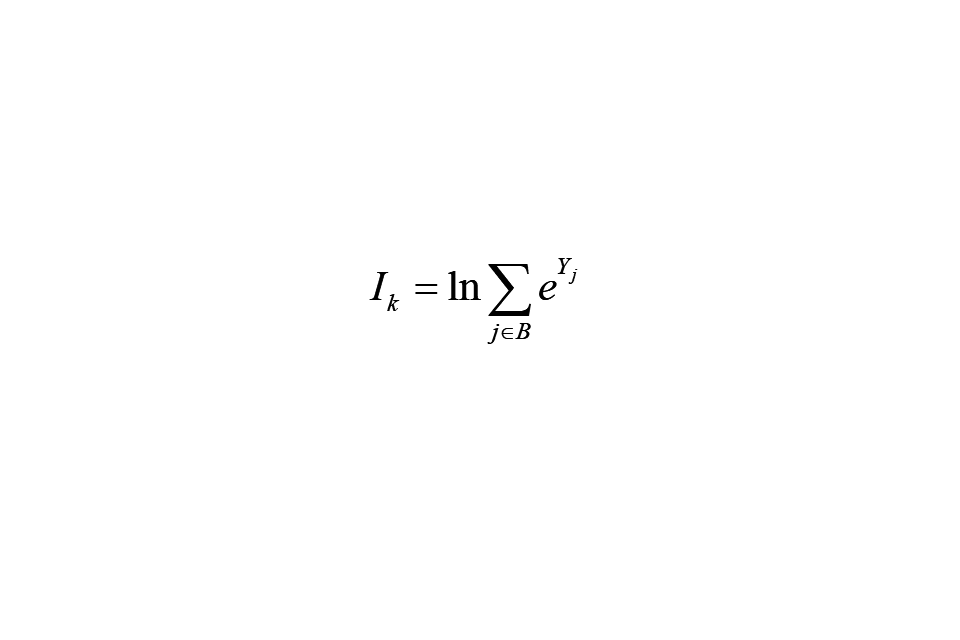

This approach to understanding, and quantifying, how different factors can influence decisions is strongly grounded in economic theory. Prof Daniel McFadden was awarded the Nobel Prize for Economics in 2000 for his work in developing the theoretical basis that underpins the modelling of discrete choice data.

In the context of this study, a choice experiment was developed to give insight into the decision making of SMEs, and how uptake of health and wellbeing schemes might be improved through a government support package including financial reimbursement and/or signposting advice for the SME, with careful consideration of how different configurations of this scheme are designed and the support that might be provided to SMEs to help them access these. The experiment specifically tested how different levels of support might affect uptake of the whole package of government support for SMEs to purchase health and wellbeing schemes. However, it is assumed that anything which increases SME uptake of the government support package would increase SME uptake of the health and wellbeing scheme in scope for that package.

By observing the choices made between different SME support packages, including the option not to take up any support package, the research could measure the strength of preference and trade-offs of SMEs towards different characteristics that can influence their decision to take up the support, including but not exclusive to the level of the financial incentive.

This approach provides an indirect way to establish the importance of different factors and is less prone to bias and gaming by respondents than asking directly about what is important. It provides a mechanism under which it is not possible to say that everything is important and forces respondents to consider the sorts of trade-offs that they have to make in real life. It therefore provides a better measure of how much weight is placed upon different factors when choosing between alternatives.

This choice experiment was embedded in a wider telephone survey which allowed us to ask additional questions to ascertain both current levels of provision and the extent of aspirations to do more, alongside questions to assist in profiling the nature of the SME responding so that differences between sub groups could be explored.

1.4.2. Development of survey and discrete choice experiment

The design of the survey was informed by some initial qualitative interviews with SMEs to understand how they conceptually understood the issues of interest and to explore the language used by SMEs when discussing these. A workshop was also held with key stakeholders to identify the policy dimensions to explore within the choice experiments and how to translate these to attributes and their associated levels. The draft survey and choice experiment was then iterated within the wider project team before being formally piloted with a group of 45 SMEs, and then refined.

The final choice experiment asked SMEs to consider choices with three alternatives: they could choose one of two available support packages, or indicate that they would continue as they were. Each support package was described by four groups of attributes:

- the type of scheme supported,

- the advice available to SMEs

- the financial support offered, including payment terms

- and the administrative requirements if participating.

An example choice is shown in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Example of the choice scenario

The dimensions and different options for each attribute are described in Chapter 4, along with the findings from the experiment.

Each SME was asked to consider six different scenarios, with the levels presented on each attribute describing the offer being varied according to a statistical experimental design. In total 90 different sets of scenarios were considered across the sample, providing the data required to model the influence that each attribute has on the likelihood that a support package is chosen.

1.4.3. Telephone survey

The survey containing the DCE was rolled out to 500 SMEs across Great Britain, providing a rich dataset for the analysis of SMEs current practices and interest in engaging in future schemes to support employees.

The survey comprised 500 telephone interviews with SME employers in Great Britain (GB) with at least 10 employees. The sampling frame for the survey was sourced from DBS Data Solutions. A decision was taken to deliberately stratify the sample by SME size, as shown in Table 1.1, to obtain sufficient data from larger SMEs and support meaningful comparisons between groups. Survey fieldwork took place between November 2018 and January 2019. The descriptive statistics presented in this report relate to the survey sample and are unweighted. However, the forecasts from the model are weighted to provide insight into the potential uptake of support packages across the SME population.

Table 1.1 Distribution of SMEs (between 10-249 employees) by size

| SME Size | Survey sample | UK population (2018) |

|---|---|---|

| 10-19 employees | 36% | 55% |

| 20-49 employees | 37% | 29% |

| 50-99 employees | 15% | 10% |

| 100-199 employees | 10% | 5% |

| 200-249 employees | 2% | 1% |

Note: The survey sample was drawn from GB, but the BEIS Business Population Estimates are based on all UK

Further details regarding the design of the discrete choice experiment and data collection and the survey questionnaire are provided in the appendix.

1.4.4. In-depth interviews

To supplement the information collected through the online survey, a set of 30 follow-up telephone interviews with a subset of the SMEs that had participated in the survey were undertaken to gain richer insight into some of the issues emerging in the survey analysis.

Organisations were selected to provide coverage of SMEs that differed in size, differed in their experience of employing staff with long term health conditions or disabilities, and differed in their indicated interest in engaging with new initiatives to support the health and wellbeing of their staff. Responses provided in the main survey were used to identify potential participants on these criteria. The sampling frame for these interviews is shown in Table 1.2. The criteria for whether the respondent had previously stated that they would be likely to opt into an incentivised action plan provided insights from those with differing interest in engaging with an intervention. Whether the SME employed disabled staff was emerging as a distinguishing factor in the analysis of the value that SMEs placed on some dimensions of the interventions on offer so there was interest in further exploring the factors behind this.

Table 1.2 Sampling frame for qualitative interviews

| SME Size (number of employees) | Stated likelihood to opt for incentivised action plan | Employ staff with disabilities or long term conditions | Sample requirements | Interviews completed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10-19 | Likely | Yes | minimum 7 respondents | 4 |

| 10-19 | Likely | No | minimum 7 respondents | 5 |

| 10-19 | Unlikely or don’t know | Yes | minimum 7 respondents | 3 |

| 10-19 | Unlikely or don’t know | No | minimum 7 respondents | 4 |

| 20-249 | Likely | Yes | minimum 7 respondents | 6 |

| 20-249 | Likely | No | minimum 7 respondents | 1 |

| 20-249 | Unlikely or don’t know | Yes | minimum 7 respondents | 3 |

| 20-249 | Unlikely or don’t know | No | minimum 7 respondents | 4 |

The purpose of these interviews was to help provide a better understanding of SMEs’ underlying rationales when choosing between support packages and survey responses, as well as to explore research questions not suitable to be covered within a survey. The timing of the interviews post-survey allowed emerging findings to be further explored.

The full protocol used for these follow-up interviews is included in the appendix.

Information on the sector within which the business operates was also collected when undertaking these interviews. This is provided alongside company size to provide some context to the quotes that are used to illustrate the attitudes and behaviours identified.

2. What SMEs currently provide

This chapter includes findings from the quantitative survey and qualitative interviews. It explores:

- what health and wellbeing services small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) already invest in, or are willing to invest in should they identify a need (section 2.1)

- barriers to providing health and wellbeing schemes (section 2.2)

2.1. Current provision of health and wellbeing support

The survey explored two broad categories of health and wellbeing schemes for employees:

- Interventions aimed at proactively promoting health and wellbeing for all employees, ranging from programmes to encourage individual behaviour change, (e.g. cycling schemes) to programmes reducing (the impact of) stressors in and outside the workplace (e.g. stress management schemes or Employee Assistance Programmes (EAPs)).

- Interventions specifically supporting employees with existing health conditions, ranging from independent expert advice on how to manage a condition in the workplace (e.g. Occupational Health services), to employer-funded therapeutic interventions (e.g. physiotherapy).

Within the survey, SMEs were asked about their current provision of schemes across both of these categories. For both, the interest was to identify what, if anything, they were providing above and beyond legal obligations like Health and Safety regulations or the provision of accommodations for disabled people under the Equalities Act (2010).

When discussing the support available to all staff, respondents were asked to report their current provision across eight possible sub-categories, with examples provided to help illustrate the types of support that might be considered within each category. The breakdown by category is shown in Table 2.1.

The survey found that the three most common programmes offered in the past 12 months were mental health support or training (39%), help with managing stress (39%), and employee assistance programmes (34%).

Whilst the data in Table 2.1 shows the provision of different forms of health and wellbeing scheme, it is also informative to look at how many of these different types of scheme are provided by any individual employer. The counts are therefore presented along with the cumulative totals that reveal the proportion of SMEs with different levels of provision.

Table 2.1 Health and wellbeing schemes currently provided to all employees

| Type of health and wellbeing scheme | Examples | Provided in the last 12 months |

|---|---|---|

| Mental health support or training | Mental health awareness training; training for line managers on how to recognise and address mental health issues; confidential helpline for employees with mental health concerns. | 39% |

| Help with managing stress | Workshops or training to raise awareness about work-related stress; briefings about stress at work; employee stress survey; staff training to prevent bullying or harassment; line manager training on dealing with stress. | 39% |

| Employee assistance programme | Helpline and/or other services offered to all employees to provide confidential expert advice when needed; may cover wider health and wider wellbeing issues, such as financial. | 34% |

| Schemes to encourage physical activity | Loans/discounts on bicycle purchases; free or subsidised gym membership; fitness classes at work; any measures to encourage running, cycling and walking. | 33% |

| Free or subsidised health services offered to all employees | Health screening, health checks, or free vaccination; health insurance | 32% |

| Other activities, such as campaigns to raise awareness about healthy lifestyles | General advice, bulletins or posters on how to live healthily; workshops or seminars on healthy lifestyles; training for line managers on improving employee health and wellbeing | 27% |

| Schemes to encourage healthy eating | Healthy food offered in the workplace /canteen; training or advice on how to eat well; weight loss advice or programmes. | 25% |

| Advice or support for employees to give up smoking | Promotional advice or material in the workplace; smoking cessation classes; help with accessing external smoking cessation programmes | 19% |

| Base | 500 |

Base: All respondents (unweighted)

Employers could select more than one response, therefore column percentages do not add to 100%.

As can be seen from Table 2.2, in total, 70% of SMEs surveyed provided at least one form of support to all staff, with 43% providing three or more forms of support. 30% do not provide anything.

Table 2.2 Number of different types of health and wellbeing scheme currently provided by SMEs to all employees

| Types of scheme provided | Count |

|---|---|

| 8 | 7% |

| 7 | 3% |

| 6 | 4% |

| 5 | 5% |

| 4 | 11% |

| 3 | 14% |

| 2 | 13% |

| 1 | 13% |

| None | 30% |

| Base | 500 |

Base: All respondents (unweighted)

| Types of scheme provided | Cumulative |

|---|---|

| 8 | 7% |

| 7 or more | 10% |

| 6 or more | 14% |

| 5 or more | 19% |

| 4 or more | 29% |

| 3 or more | 43% |

| 2 or more | 56% |

| 1 or more | 70% |

The survey also asked about provision of schemes specifically for people with existing conditions, either to help them get better or to manage their condition more effectively. Ill-health and the need to manage long-term health conditions in the workplace can be infrequent occurrences for small employers. Hence, the survey asked what employers were currently providing, and also what they would provide if faced with an employee need. This allowed us to identify the proportion of SMEs that were open to providing such schemes, and those that would not provide it should a need materialise. The descriptions of the different types of schemes that employers were asked to consider are shown in Table 2.3 along with summary data on the proportions of SMEs that would be willing to provide these to their staff.

For those that have experienced a need to which they have responded, the provision of independent expert advice such as occupational health is the most common response, stated by 36% of employers. Only 22% of employers stated that they would not provide this should the need arise. Employers stated that they were less likely to provide other forms of (potentially more costly) support should the need arise.

However, it is important to note that the data on “what employers would provide should the need arise” is self-reported, so it may be subject to social desirability bias. In addition, ‘employee need’ is subjective, and therefore could be impacted not only by incidence of the relevant health issues, but also by the employer’s awareness of employee health issues and the bar they set for employee need. Despite this, the high proportions indicating a willingness to do so suggests that any low provision of health-related support services for staff with health conditions could be at least partly due to lack of perceived need and not low willingness to pay.

Examining the responses across all categories of targeted scheme reveals that whilst 53% of the sample do not currently provide any of these types of scheme, only 17% say they would not provide any of these if the need arose.

Table 2.3 Targeted health and wellbeing programmes currently provided or would be provided by SMEs to employees

| Type of scheme | Examples | We currently provide this or have in the last 12 months | We would certainly provide this if the need arose | Would not provide this |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent expert advice for employees and line managers on how to manage a condition in the workplace | Such as by occupational therapists or via an Occupational Health service | 36% | 42% | 22% |

| Free or subsidised access to psychological therapy | Cognitive behavioural therapy, counselling | 19% | 41% | 40% |

| Free or subsidised access to rehabilitative services for physical health conditions | Physiotherapy | 16% | 37% | 46% |

| Access to programs to address specific problems | Programmes or services to tackle: mental health issues; eating disorders, weight management; addiction issues | 14% | 46% | 40% |

| Other forms of non-medical advice | Mentoring programmes; independent expert advice on health and wellbeing issues | 18% | 41% | 41% |

Base: All respondents (unweighted), row total = all respondents (500)

2.1.1. Smaller SMEs are observed to provide fewer health and wellbeing schemes

The analysis examined whether there were significant differences in level of provision between different groupings of SMEs.

Larger SMEs (with 50 or more staff) showed a higher percentage of current provision than smaller SMEs. The differences are relatively consistent between types of support, and show a progression in provision from the smallest SMEs through to the mid and large SMEs.

With regards to proactive preventative support for all staff, Figure 2.1 shows a marked difference in the provision of mental health and wellbeing provision between different size SMEs – with approximately 30% of SMEs with 10-19 employees providing mental health support or training or help with managing stress, compared to over 50% for SMEs with more than 50 employees. There is also a large difference by employer size on services that require an ongoing financial commitment, such as subsidised health services and EAPs, although for EAPs this may in part be due to the wider insurance products targeted at the larger SME market that sometimes include EAP provision.

Figure 2.1 Proportion of SMEs currently providing general health and wellbeing programmes to all employees, by company size (multiple choice)

| Company size | 10-19 (179) | 20-49 (186) | 50+ (135) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mental health support or training | 30% | 37% | 55% |

| Help with managing stress | 31% | 39% | 49% |

| Schemes to encourage physical activity | 27% | 33% | 40% |

| Schemes to encourage healthy eating | 21% | 22% | 35% |

| Advice or support for employees to give up smoking | 17% | 19% | 20% |

| Free or subsidised health services offered to all employees | 23% | 31% | 47% |

| Employee assistance programme | 22% | 34% | 49% |

| Other activities, such as campaigns to raise awareness about healthy lifestyles | 20% | 25% | 39% |

| None of these | 42% | 28% | 18% |

Base (unweighted): All respondents (500)

More than 40% of employers with less than 10 employees have not provided any of the listed forms of general health support to their staff in the past 12 months.

Differences can also be observed in the current provision of, and intent to provide, targeted health and wellbeing support for those that have known long term conditions.

Figure 2.2 Proportion of SMEs currently providing targeted health and wellbeing schemes, or would provide, to employees with health conditions, by employer size (multiple choice)

Independent expert advice for employees and line managers on how to manage a condition in the workplace:

| Employer size | Current/last 12 months | Would provide | Would not provide | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10-19 (179) | 21.23% | 50.28% | 28.49% | 100% |

| 20-49 (186) | 27.96% | 48.39% | 23.66% | 100% |

| 50+ (135) | 65.19% | 22.96% | 11.85% | 100% |

Free or subsidised access to psychological therapy:

| Employer size | Current/last 12 months | Would provide | Would not provide | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10-19 (179) | 8.38% | 46.93% | 44.69% | 100% |

| 20-49 (186) | 13.98% | 41.40% | 44.62% | 100% |

| 50+ (135) | 40.00% | 31.85% | 28.15% | 100% |

Free or subsidised access to rehabilitative services for physical health conditions:

| Employer size | Current/last 12 months | Would provide | Would not provide | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10-19 (179) | 11.17% | 43.02% | 45.81% | 100% |

| 20-49 (186) | 11.83% | 34.95% | 53.23% | 100% |

| 50+ (135) | 29.63% | 33.33% | 37.04% | 100% |

Access to programs to address specific problems:

| Employer size | Current/last 12 months | Would provide | Would not provide | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10-19 (179) | 9.50% | 51.96% | 38.55% | 100% |

| 20-49 (186) | 10.22% | 43.55% | 46.24% | 100% |

| 50+ (135) | 25.19% | 42.22% | 32.59% | 100% |

Other forms of non-medical advice:

| Employer size | Current/last 12 months | Would provide | Would not provide | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10-19 (179) | 13.41% | 42.46% | 44.13% | 100% |

| 20-49 (186) | 15.05% | 37.63% | 47.31% | 100% |

| 50+ (135) | 28.15% | 42.22% | 29.63% | 100% |

Base (unweighted): All respondents (500)

Larger SMEs (with 50 or more staff) showed a much higher level of current provision, as would be expected given the higher likelihood of employing staff requiring support. Once the stated intent to provide support should it be required is taken into account, there is only a small gap in overall willingness to pay for support for employees with health conditions between larger and smaller SMEs.

2.1.2. Provision is often employee led, and comes about as a result of requests

The follow-up qualitative interviews were used to get more insight into how SMEs approach providing health and wellbeing schemes for their staff. SMEs were asked the types of scheme they provided and how they identified the need for this support. This revealed a tendency amongst SMEs to use informal approaches to identify where their staff may benefit from support, and typically in a reactive manner once they see indications that something may not be right. This can be characterised as “detect and talk”; they will see that something does not seem right and then try to ascertain what is wrong and how the business might help. In the words of one interviewee:

It is reliant upon people reporting it to us or other colleagues or managers reporting it to us, we don’t have a monitoring system.

(Arts, entertainment, and recreation, 20-49 employees)

Within smaller companies there is often an ethos of operating as an extension of the family:

Basically I look after long-standing employees, we’re a family business. I keep an eye on my staff. If I can see something is wrong, I’ll ask them and basically I will see if I can help.

(Information and communication, 10-19 employees)

It’s really a case of understanding the team itself. There’s only twelve of us, rather than having a formal situation whereby, you know, you fill in some tick boxes or meet on a Monday and, you know, discuss your issues, it’s very much a case of managing bottom up and top down so that if people have any issues it’s discussed and then brought to the attention of myself as MD as necessary. I think a lot of help and support comes out of the culture of the organisation as much as from pre-arranged schemes.

(Other service activities, 10-19 employees)

And those that do not currently provide a framework for support often feel that the size of their business does not justify it and they would deal with issues should they arise:

It’s not that we don’t see a need, it’s the extent to which we need to formalise stuff, in a much larger organisation, things need to be more formalised because there may be an absence of communication on a subject. We have management group meetings once a week and any issues of this would be discussed there and communicated to make sure line managers are aware of any concerns that we might have.

(Professional, scientific and technical activities, 50-99 employees)

We know our employees quite well, a lot of our employees are older people. They have been here for a long time. We like to think that we know something about them, we know them personally. We know their moods, we know when they’re down and we talk to them. If somebody has a specific need, we would absolutely find them some help if we could. So, we are not anti it, it’s just we haven’t had to do it.

(Manufacturing, 50-99 employees)

There are however some SMEs that do not see providing support to their staff in this area as necessary, or something that they could easily accommodate:

I don’t really have a need for it, because generally the staff are young and fit at the end of the day

(Accommodation and food service activities, 20-49 employees)

We don’t have that sort of budget to do a lot of in-worktime activities

(Human health and social work activities, 20-49 employees)

I think now we have fourteen members of staff. So it would be quite difficult to see us setting up a very elaborate sort of… although I guess there’s stuff that you could buy off the shelf. Another thing is that, because we’re small, because we work as well as we can in a consensual way, you hope that those sort of issues can in some sense, be dealt with internally.

(Information and communication, 10-19 employees)

Without exception, all of the SMEs interviewed spoke in a way that suggested that they took an interest in their staff and would support them in times of difficulty. What was clear, however, was that whilst some had taken steps to raise issues of mental health in the workplace or put in place schemes to help encourage physical activity, very few had thought in any structured way about how they might take this further. Most would wait until a member of staff brought forward an idea or issue before taking any additional steps.

This research therefore suggests that SMEs are often more reactive than proactive in their approach to health and wellbeing, and are frequently led by their staff and their emerging needs.

2.1.3. More SMEs provide preventative general support than targeted support for employees with existing conditions

Across the sample, 40% of SMEs employ staff with long-term health conditions and/or disabilities; ranging from 29% of SMEs with 10-19 employees to 51% of SMEs with more than 50 employees. The survey showed that these SMEs were more likely to have preventative support in place for all of their workers than those that do not employ such staff.

These SMEs also provided more health promotion schemes for all staff than schemes targeted for employees with health conditions. This might suggest that employers that experience health issues in the workplace (or are more open to employing such staff) are more likely to invest in health promotion schemes for the benefit of all staff. As such, there could be a level of latent willingness within the wider SME population to do more if they better understood the potential benefits.

Figure 2.3 Proportion of SMEs currently providing preventative health and wellbeing programmes to all employees, by whether staff have LTCD (multiple choice)

| Types of health and wellbeing programmes | Do not have staff with disabilities or long term conditions (301) | Have staff with disabilities or long term conditions (199) |

|---|---|---|

| Mental health support or training | 36% | 44% |

| Help with managing stress | 35% | 44% |

| Schemes to encourage physical activity | 28% | 40% |

| Schemes to encourage healthy eating | 22% | 29% |

| Advice or support for employees to give up smoking | 16% | 23% |

| Free or subsidised health services offered to all employees | 27% | 41% |

| Employee assistance programme | 28% | 43% |

| Other activities, such as campaigns to raise awareness about healthy lifestyles | 22% | 35% |

| None of these | 37% | 21% |

Base (unweighted): All respondents (500)

Nearly 30% of SME employers who reported they did not employ staff with long-term health conditions and/or disabilities have invested in advice on how to manage a condition in the workplace. These could have been provided to manage injuries, sicknesses, and conditions considered to be short-term, or to support staff that have since left the business.

Figure 2.4 Proportion of SMEs currently providing targeted health and wellbeing programmes, or would provide, to employees with LTCD, by whether staff have LTCD (multiple choice)

Independent expert advice for employees and line managers on how to manage a condition in the workplace:

| Employer size | Current/last 12 months | Would provide | Would not provide | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (301) | 29.24% | 44.85% | 25.91% | 100% |

| Yes (199) | 45.23% | 38.19% | 16.58% | 100% |

Free or subsidised access to psychological therapy:

| Employer size | Current/last 12 months | Would provide | Would not provide | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (301) | 16.61% | 38.87% | 44.52% | 100% |

| Yes (199) | 22.61% | 43.72% | 33.67% | 100% |

Free or subsidised access to rehabilitative services for physical health conditions:

| Employer size | Current/last 12 months | Would provide | Would not provide | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (301) | 13.29% | 38.21% | 48.50% | 100% |

| Yes (199) | 21.11% | 36.18% | 42.71% | 100% |

Access to programs to address specific problems:

| Employer size | Current/last 12 months | Would provide | Would not provide | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (301) | 10.30% | 45.85% | 43.85% | 100% |

| Yes (199) | 19.60% | 46.73% | 33.67% | 100% |

Other forms of non-medical advice:

| Employer size | Current/last 12 months | Would provide | Would not provide | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (301) | 15.95% | 42.19% | 41.86% | 100% |

| Yes (199) | 21.11% | 38.19% | 40.70% | 100% |

Base (unweighted): All respondents (500)

2.2. Barriers to providing health and wellbeing support

Respondents were asked what barriers they experience to providing health and wellbeing in the workplace. The top three barriers selected were lack of capital (52%), not having the time or resources (49%), and lack of knowledge about which areas to invest in (49%). Added to which, nearly a third of SMEs stated that not knowing where to purchase high quality health and wellbeing support was a barrier to investing. This suggests that, in addition to financial support, SMEs may benefit from advice services to understand what they need and how to procure it.[footnote 13]

Table 2.4 Barriers to supporting health and wellbeing intervention

| Barrier | % of SMEs |

|---|---|

| We don’t have the capital to invest in health and wellbeing initiatives | 52% |

| We don’t have the time or resources to develop and implement health and wellbeing policies | 49% |

| We don’t have the expertise or specialist support to know what health and wellbeing measures to invest in | 49% |

| We wouldn’t know where to purchase high quality health and wellbeing support | 31% |

| The way in which our work is organised does not allow flexibility to accommodate extra activities such as health and wellbeing training | 27% |

| Our employees would not be interested in health and wellbeing initiatives | 19% |

| It doesn’t fit with the priorities of our senior managers | 11% |

| The benefits of investing in health and wellbeing interventions don’t warrant the investment | 7% |

| None of these | 12% |

| Base | 500 |

Base (unweighted): All respondents (500)

Employers could select more than one response, therefore column percentages do not add to 100%

Given that there are observable differences in the propensity to offer support by size of the SME, barriers were also compared by SME size.

Figure 2.5 shows that the relative importance of each listed barrier is similar across companies of different sizes. In general, fewer larger companies report barriers, and they appear to have a better understanding of where to purchase support than smaller SMEs. However, the issues of capital and time to invest in these activities are consistently an issue across all sizes of SMEs, as is the issue of identifying what to invest in.

Figure 2.5 Proportion of SMEs identifying different barriers in supporting workplace health and wellbeing programmes, by company size (n = 500) (multiple choice)

| Company size | 10-19 (179) | 20-49 (186) | 50+ (135) |

|---|---|---|---|

| We don`t have the expertise or specialist support to know what health and wellbeing support to invest in | 50% | 52% | 42% |

| We wouldn`t know where to purchase high quality health and wellbeing support | 33% | 37% | 22% |

| We don`t have the time or resources to develop and implement health and wellbeing policies and interventions | 53% | 49% | 44% |

| The way in which our work is organised does not allow flexibility to accommodate extra activities such as health and wellbeing training | 27% | 24% | 30% |

| Our employees would not be interested in health and wellbeing initiatives | 25% | 16% | 16% |

| We don`t have the capital to invest in health and wellbeing support | 51% | 56% | 47% |

| It doesn`t fit with the priorities of our senior managers or organisational priorities | 8% | 11% | 16% |

| The benefits of investing in health and wellbeing interventions don`t warrant the investment | 7% | 8% | 7% |

| None of these | 11% | 8% | 18% |

Base (unweighted): All respondents (500)

Other evidence suggests that lack of funding is one of the biggest barriers to implementing schemes[footnote 14]. However, the interviews undertaken suggest there are also opportunities to assist SMEs with identifying what type of support is effective to invest in, and with helping them to identify support providers.

The follow-up qualitative interviews were also used to explore the obstacles that SMEs believed they might encounter in implementing health and wellbeing programmes. Again, cost and time came through as key factors:

Obviously there is potentially the cost. Also I guess the other obstacle is the potential amount of time that it takes to do. Those would be them and, I am talking about resources both in financial terms and peoples’ time.

(Information and communication, 10-19 employees)

It would have to be financial and the opinions of the directors, whether they would want to go ahead with something like that, I am not sure.

(Construction, 20-49 employees)

However, when it was suggested that there could be financial support made available, there was also some concern that funding doesn’t come without expectations and administrative burdens:

The problem I’ve always found with any funding that’s available is you end up spending so much time jumping through hoops that at the end you think, wonder whether it was worth it.

(Other service activities, 10-19 employees)

The need for advice and support also came through strongly:

I need the money but with all due respect, most HR people don’t. You need advice and guidance before the money I think.

(Education, 200-249 employees)

If you just get offered money up front you’re thinking ‘now I don’t quite know what to do with it, what am I supposed to do with it?’

(Construction, 20-49 employees)

There are a lot of brokers out there trying to sell you something that’s not always appropriate and they’ll often tell you what you want to hear and then find that it’s probably no good. So it pays to do a lot of research, probably get a referral from other people that are using an effective service.

(Accommodation and food service activities, 10-19 employees)

However, the issue of staff buy-in also came up in these conversations:

So it is more of a generation thing. They are proud, older and male - would not want to talk about mental health – it is already difficult to engage them in staff health questionnaire every year which is just ticking boxes. I think I would have stumbling blocks that I would walk into an empty room, the provider would be there and none of my employees would turn up.

(Manufacturing, 50-99 employees)

We can’t force people to take up the service. The obstacles would be reticence on the part of staff to take it up, they might see it as a weakness.

(Arts, entertainment, and recreation, 10-19 employees)

This research therefore confirms that lack of advice, lack of funding, and administrative requirements all play a role in SMEs offering health and wellbeing interventions to staff. These factors are explored further in the discrete choice experiment which provides insight into how these factors combine to influence that choices that SMEs may make. These findings are reported in Chapter 4.

On the whole, SMEs showed good levels of engagement with the issues of staff health and wellbeing, but current levels of provision are mixed. Currently, some SMEs appear to be doing a lot, whereas others are doing relatively little. Whilst intentions often appear to be good, companies of this size seem to largely be reactive to staff requests and needs rather than proactively promoting health and wellbeing for all staff. As such, there be may an opportunity to enhance provision by bringing information on the types of provision that is available, along with information on its benefits and where to buy it, to the attention of employers. However, financial constraints, as well as time, can be a barrier to adoption. This suggests that both advice and funding may help in supporting employers to take a more proactive approach to investing in employee health and wellbeing.

3. Employers have an appetite to do more

This chapter includes findings from the quantitative survey and qualitative interviews. It explores:

- key areas of health concern for SME employers (section 3.1)

- what outcomes would SME employers aim to improve if given support to provide health and wellbeing schemes? (section 3.2)

- what health and wellbeing schemes would SME employers use additional funding for? (section 3.3)

- would SME employers use funding to purchase new health and wellbeing support or to fund support they already provide? (section 3.4)

3.1. Key areas of concern for employers

When asked in the survey “which of the following do you regard as important health and wellbeing concerns that affect your business/organisation?”, musculoskeletal conditions, common mental health problems and the way work is organised or managed were the top three main concerns raised (all above 70%).

This supports previous research which found these to be the two most common health concerns of employers[footnote 15]. They are the two single most common reasons for sickness absence in the UK after minor illnesses[footnote 16] and the most common health conditions for disabled employees[footnote 17]. The gap between these three areas of concern and the others identified is significant, and suggests that any programme looking to engage SMEs would do well to focus in on these areas.

Figure 3.1 Proportion of SMEs reporting different health and wellbeing concerns (n= 500) (multiple choice)

| Musculoskeletal conditions | 83% |

| Common mental health problem | 81% |

| The way work is organised or managed | 70% |

| Addiction | 29% |

| Low levels of physical activity | 12% |

| Weight | 7% |

| Other | 3% |

Base (unweighted): All respondents (500)

Follow-up interviews found that the concerns around musculoskeletal conditions were driven by two quite different clusters: those that were concerned about low levels of activity doing desk based work along with repetitive movements, and those that were concerned about heavy lifting and physical strain.

One respondent gave an example of where they had provided additional support in the form of physiotherapy:

One of our chefs had a little bit of, we thought it was sciatica, so we knew the doctor would be fairly useless when he made an appointment to go to the doctor’s. They’re not specialists in musculoskeletal, so we use a physio chiro and wellbeing. So we sent him along to the physio for a session and they recommended a few tweaks and exercises and he’s feeling a lot better.

(Accommodation and food service activities, 10-19 employees)

Concerns regarding mental health could be clustered into two groups: those that were aware of the stresses and strains of the workplace, and those that recognised that their staff could have complications outside of work that could also impact on their working life.

The structure, and areas of specialisation, of SMEs can create environments that are stressful and the interview revealed examples of employers that are aware that mental health issues can occur within the workplaces.

Mental health issues, because we operate flexible work shift patterns, the staff can be working on a nightshift one day and they can be on a back shift the next day. They could be working early mornings all week; they could be away from home. That puts a lot of pressure on, or can put a lot of pressure on, people. But then their health needs to be regarded.

(Mining and quarrying, utilities, 10-19 employees)

You would think, looking at the type of work we do, I mean a lot of it is around stress control because of the nature of the work we do. So, I think trying to sort of manage your workloads and keep colleagues’ stress levels down is probably one of the main major key things for us as an organisation to look after their wellbeing.

(Other service activities, 10-19 employees)

Well, I think, realistically, stress is probably the most of concern because of the way our business is run, we do ad-hoc work, so it’s either not enough work and then you’re stressed because you’ve got to try and bring work in, or there’s far too much work and you’re stressed because you’ve got to deliver it all

(Information and communication, 10-19 employees)

Employers recognised that poor mental health can also be exacerbated by issues outside of the workplace, although there are a range of attitudes, with some seeing it as something that work can contribute to, whereas others see it as something that they just need to deal with as an employer:

… and the mental health issues we bring in with us as well to work, you know, we don’t work in a vacuum.

(Professional, scientific and technical activities, 10-19 employees)

The key issue on the health side would be stress and that can be work-based stress or non-work-based stress.

(Arts, entertainment, and recreation, 20-49 employees)

I think that the people have things happening in their lives, sometimes to do with work but also outside of work that cause them to have difficulties. To be anxious or depressed, so I think that that is an issue that most employers have to deal with.

(Information and communication. 10-19 employees)

With regard to emotional care, I think it’s very important that as an employer you holistically understand your team in order to help the company because by empathising and understanding and looking after your team you’re going to get the best from your people in the work environment.

(Other service activities, 10-19 employees)

Anxiety, depression? Yes, there are some examples that I am aware of. I would like to think that those are not caused by work, necessarily. I think some people are just predisposed to that, aren’t they? Again it is something that we are aware of that we try to be supportive of.

(Professional, scientific and technical activities, 100-199 employees)

Some employers felt that some aspects of staff health or wellbeing had impacts on their businesses, but did not seem to see it as their place to do anything about these:

Physical health, as a company, we don’t have much policy in this area. Again, I know you can do quite a bit in this area, but traditionally, my view, and the other directors’ view is, this is starting to cross a privacy boundary.

(Arts, entertainment, and recreation, 20-49 employees)

We lose staff who have issues with alcohol or drugs occasionally and because we employ lots of part-time staff who have to constantly juggle work/life issues.

(Accommodation and food service activities, 20-49 employees)

One SME felt that the way for them to address the issues that they had identified was through how they went about recruitment in the future, rather than an intervention to support those staff already working for them:

Structure of work, yes. I mean there are definitely some managers who perhaps need to work on work/life balance. Again, it is something we’re trying to deal with in ongoing recruitment, among all things we’re striving for.

(Professional, scientific and technical activities, 100-199 employees)

SMEs generally recognise the biggest challenges facing their business regarding health and wellbeing and can articulate why these are a challenge. In most cases they seem to accept the challenges as the nature of their business, and this suggests that there is an opportunity to better support and guide them in identifying proactive steps they could take to address these.

3.2. What outcomes would employers aim to improve with additional support

The follow-up qualitative interviews also explored what kind of outcomes employers would aim to improve by the provision of additional health and wellbeing services. Overall, proactive health and wellbeing promotion was more prominent in employers’ thinking when prompted to think about desirable outcomes.

It was generally appreciated that any intervention would be intended to achieve a change:

The point of running these courses is that the person participating improves whether it be financial, or health, or wellbeing, or, you know, whatever it is. I mean the course would dictate as to what you would expect the outcome to be.

(Other service activities, 10-19 employees)

If we put people in counselling, it keeps them at work. We have paid for things like Weight Watchers for other people in the past

(Education, 200-249 employees)

Key outcomes that SMEs identified that would be both desirable and measurable within their business were reductions in sickness absence and staff turnover:

If it was translated into less sickness days, that would certainly be a positive. And also increased happiness is very important to us. But I don’t quite know how to measure

(Construction, 20-49 employees)

There would certainly need to be a benefit to the practice. But, again, retention is a benefit, and so is them attending work on a regular basis.

(Manufacturing. 10-19 employees)

We would like to limit our staff turnover

(Arts, entertainment, and recreation, 10-19 employees)

That they feel happier and healthier and hopefully I suppose also leading on from that, you would hope that people were encouraged to want to stay longer I think it would be an incentive like ‘I enjoy working here’”.

(Construction, 20-49 employees)

I would hope the staff were happier, more relaxed, felt we were taking their wellbeing seriously and I suppose gluing them a bit more to the business, thinking we are a business worth working for.

(Information and communication, 10-19 employees)

We do monitor attendance and sickness and there are a lot of different factors that could influence that, but how we would monitor it is because it’s on an individual basis, we would be looking to see whether or not we are improving the health and welfare of that individual, just by talking to them, just by consultation.

(Arts, entertainment, and recreation, 20-49 employees)

However, there was also a significant cohort of SMEs within the group interviewed that did not really think about outcomes and measurement, especially employee subjective wellbeing; largely as a result of the size of their workforce and the ability (and desire, as mentioned earlier) to manage things at an individual level.

We don’t have any [outcome measures], it may sound stupid, but because we are so flexible, people like working here, we never really have a problem with that

(Administrative and support service activities, 10-19 employees)

No, I don’t measure specifically, as I say, we’re a small team of twelve so I am able to make judgement calls on a daily basis of how people interact, inter-relate, of if you like happiness within the workplace. I think they’re very difficult to measure, I think you really need your management to be sort of trained and understanding. You probably do need to have some sort of measurement tool if you have a relatively high turnover but then that’s probably going to be part of the problem if we have a high turnover of your managers and your staff. We I don’t think have lost anybody for years, probably ten years or so.

(Other service activities, 10-19 employees)