HPR volume 10 issue 42: news (2 December)

Updated 16 December 2016

1. HIV in the UK: 2016 report

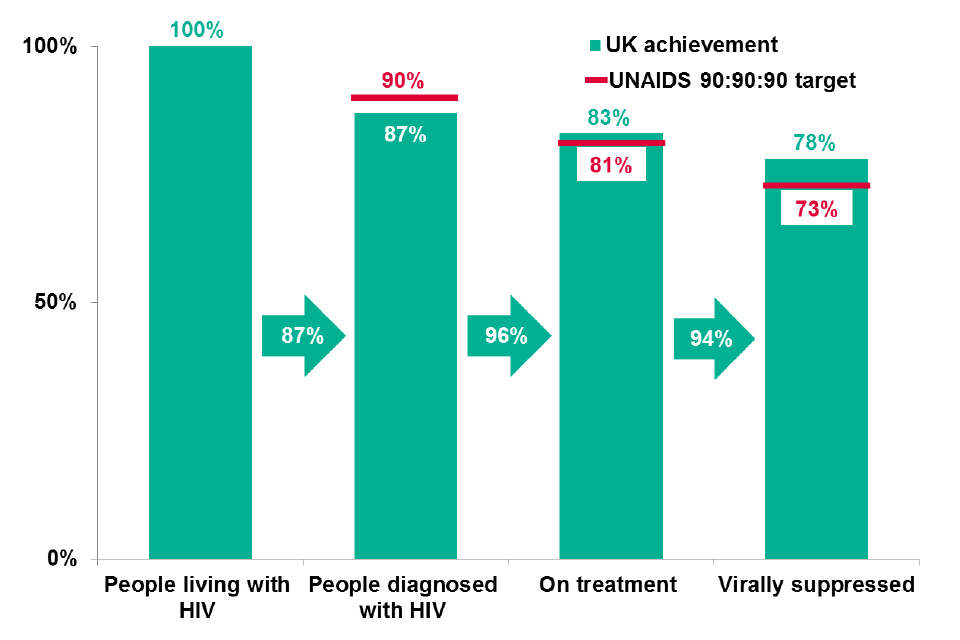

In October 2014, the joint United Nations programme on HIV/AIDS set its ambitious “90-90-90” target, which aims – by 2020 – to:

- diagnose 90% of all HIV-positive people

- provide antiretroviral therapy (ART) for 90% of those diagnosed and

- achieve viral suppression for 90% of those on treatment (equivalent to a viral suppression rate of 73% among all people living with HIV) [1].

In the UK, the second and third of these targets have now been met (see figure 1), according PHE’s latest annual report on the progress of the HIV epidemic in the UK [2]. Eighty-seven per cent of the 101,200 (95% credible interval 97,500-105,700) estimated number of people living with HIV in 2015 had been diagnosed. Of those diagnosed, 96% were receiving ART; and of those receiving treatment, 94% had an undetectable viral load. Collectively, this means 78% of all HIV positive people in the UK had an undetectable viral load in 2015.

Treatment and care remain areas in which the UK continues to excel and several factors have contributed to achieving these targets. This includes changes to the UK treatment guidelines in 2014, which now recommend starting ART at diagnosis, irrespective of CD4 count [3]. In 2015, 88,769 people diagnosed with HIV were seen for care and 97% of the 6,095 people newly diagnosed with HIV were linked to specialist care within three months of diagnosis.

Figure 1. UK HIV continuum of care against UNAIDS target

People living with diagnosed HIV in the UK represent a diverse group. Over half of those newly diagnosed with HIV in 2015 were born in the UK – the first time that the proportion born in the UK has exceeded those born abroad since the 1990s. This change has been driven by a decrease in the number of new diagnoses among heterosexuals born abroad – the number of black African heterosexuals having fallen from 3,170, in 2006, to 1,110 in 2015.

In contrast, the number of gay/bisexual men estimated to have acquired their infection abroad has risen. The median age at diagnosis for gay/bisexual men was 33 years in 2015, a slight decrease from 35 years in 2006. This change is due to an increasing proportion of men aged under 35 years diagnosed with HIV each year (from 47% in 2006 to 56% in 2015).

Among gay and bisexual men, the number of new diagnoses remains high (3,320 in 2015) reflecting both testing efforts and ongoing transmission of the virus. In England, an estimated 2,800 (95% credible interval 1,700-4,400) gay/bisexual men acquired HIV in 2015.

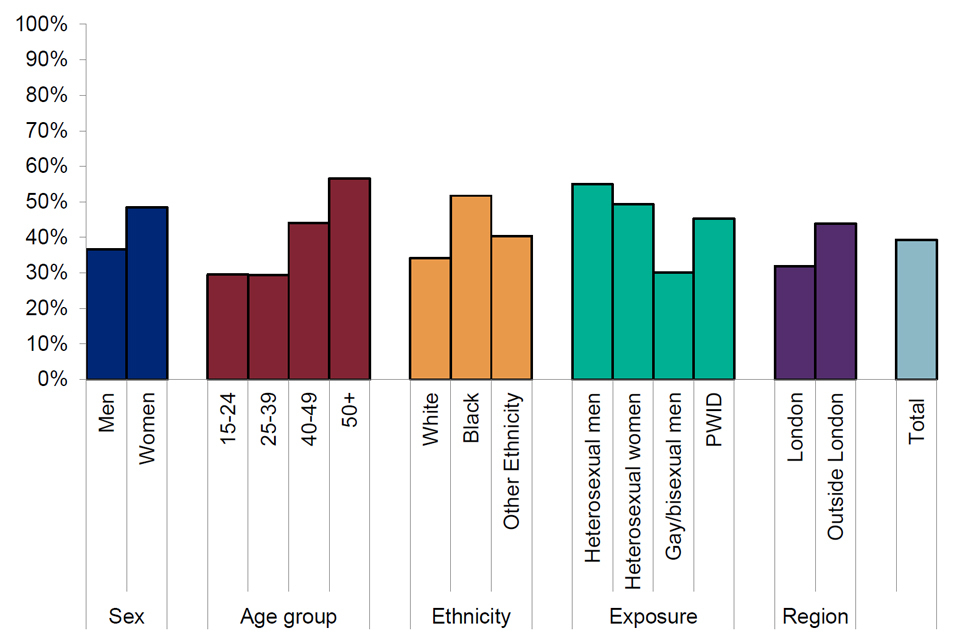

Despite this, the proportion of gay/bisexual men diagnosed late (with a CD4 count less than 350 cells/cubic millimetre) remains low, at 30% in 2015 (see figure 2). This compares to 39% of all people diagnosed late in 2015, and 22% severely immunocompromised (CD4 count <200 cells/cubic millimetre) at the time of their diagnosis.

Certain groups are disproportionally affected by late HIV diagnosis, including heterosexuals, black Africans and older adults (figure 2). In 2015, the proportion diagnosed late was highest in heterosexual men (55%) and women (49%), and particularly among black African heterosexual men and women (60% and 52%, respectively).

Figure 2. Proportion of adults diagnosed with a CD4 cell count <350 cells/cubic millimetre by demographic: UK, 2015

Late diagnosis of HIV has significant public health implications; people diagnosed late are likely to have been living with an undiagnosed HIV infection for at least three years and are at risk of passing the virus onto others. In addition, those diagnosed late continue to have a ten-fold increased risk of death in the first year of diagnosis, compared to people diagnosed early

These data highlight the fact that, despite significant advancements made towards achieving the 90:90:90 treatment target, further efforts are required to curtail HIV transmission in the UK.

1.1 References

- WHO (2014). 90-90-90: an ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic.

- PHE (1 December 2015). HIV in the UK: 2016 report

- BHIVA (2016). Guidelines for the treatment of HIV-1-positive adults with antiretroviral therapy 2015 (2016 interim update).

2. English Surveillance Programme for Antimicrobial Utilisation and Resistance third annual report

The third annual report of the English Surveillance Programme for Antimicrobial Utilisation and Resistance (ESPAUR) has been published by PHE [1]. ESPAUR – established in 2013 in response to the cross-government UK five-year antimicrobial resistance (AMR) strategy [2] – achieved several key programme objectives during its third year of activity:

- improved access to and use of data through the Fingertips initiative, a publically accessible web tool

- improved AMR and AMU surveillance by continual improvements in both the quality and quantity of surveillance data, and the ability to track each healthcare sector

- improvements to public and professional engagement activities through the Antibiotic Guardian campaign, as well as engagement with Health Education England and the PHE primary care unit

- improved antibiotic stewardship practice through the provision of toolkits to support stewardship audits in acute trusts, and in dental antibiotic stewardship.

Outputs have also been extended to cover development and implementation of antifungal resistance surveillance and stewardship.

The report indicates that, for the first time, annual total antibiotic consumption rates have declined. Reductions in antibiotic use occurred across all healthcare settings, including in primary care, dental and secondary care. The use of broad-spectrum antibiotics has decreased in primary care for the second year.

However, use of antibiotics of last resort – including Piperacillin/tazobactam, carbapenems and colistin – continues to increase in hospitals. The number of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae bloodstream infections have increased further, and also the number of individuals with drug resistant infections.

2.1 References

- PHE (November 2016). ESPAUR: report 2016.

- PHE (December 2015). UK five year antimicrobial resistance strategy 2013 to 2018.

3. HAIRS group report for 2013 to 2015

The Human Animal Infections and Risk Surveillance (HAIRS) group is a multi-agency and cross-disciplinary United Kingdom horizon scanning group, chaired by PHE’s Emerging Infections and Zoonoses section. The group has met every month since February 2004 and acts as a forum to identify and discuss infections with potential for interspecies transfer (particularly zoonotic infections).

A summary of activities undertaken by the group between 2012 and 2015 has been published by PHE [1]. During this period, topics and incidents considered by the group have ranged from high profile outbreaks (eg Mycobacterium bovis infection in cats [2]) to rare disorders affecting restricted populations (eg a novel Brucella species in a White’s Tree Frog). The increasing recognition of the importance of vectors and vector-borne disease to human and animal health within the UK has become apparent over this period. From the first detections of Borrelia miyamotoi-infected ticks in the UK [3] to the continued expansion of Culex modestus mosquitoes, discussions on vector distribution and their associated pathogens are a regular feature of HAIRS meetings. Incidents of undiagnosed morbidity and mortality and novel pathogens remain a priority for assessment.

Following reports of canine mortality in the New Forest region of England in 2012, the group regularly reviewed emerging evidence for this disorder which remains of unknown aetiology. Squirrels have been the source of several discussions by the group in the last few years with the detection of a Mycobacterium lepromatosis-like pathogen in red squirrels in the UK and the report of human fatalities associated with infection with a novel bornavirus from non-native variegated squirrels in Germany [4].

Further information on HAIRS group activities can be found on the HAIRS webpage [5].

3.1 References

- PHE (November 2016). The Human Animal Infections and Risk Surveillance (HAIRS) Group: 2013-2015 report.

- HAIRS Group (March 2013). Mycobacterium bovis in cats: public health risk assessment.

- HAIRS Group (November 2016). HAIRS risk assessment: emerging tick-borne bacteria in the UK.

- HAIRS Group (September 2016). HAIRS risk assessment: novel squirrel Bornavirus.

- PHE website. Human animal infections and risk surveillance group (HAIRS).