Health-led Trials: Evaluation Synthesis Report

Published 20 April 2023

12-month outcomes evidence synthesis

August 2022

DWP research report no.1025

A report of research carried out by the Institute for Employment Studies on behalf of the Department for Work and Pensions.

Crown copyright 2023.

You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit The National Archives or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email psi@nationalarchives.gov.uk

This document/publication is also available on GOV.UK.

If you would like to know more about DWP research, email socialresearch@dwp.gov.uk

First published April 2023.

ISBN 978-1-78659-516-4

Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and Pensions or any other government department.

Executive summary

This report presents findings from the evaluation of the Health-led Employment Trials (HLTs). These tested the provision of Individual Placement and Support (IPS) – a well-evidenced voluntary employment support programme for people living with severe and enduring mental illness in secondary care – with a group experiencing mild/moderate mental and/or physical health conditions in primary and community care settings. Estimates of impact on employment, earnings, health and wellbeing used a randomised controlled trial (RCT) design, with outcomes taken from linked survey and administrative data sets. An economic evaluation estimated the value of the impacts set against the costs of delivering the IPS services. A process evaluation using surveys and qualitative research explored implementation.

The trials recruited 9,785 people across 2 sites between May 2018 and October 2019. In Sheffield City Region (SCR), 6,110 people were recruited including an out-of-work group (SCR OOW) and a group in employment but struggling (SCR IW). The West Midlands Combined Authority (WMCA) trial recruited 3,675 people, all of whom were OOW. The IPS service offered support for a total of 12 months, with 9 months of support to find employment and 4 further months of in-work support. The evaluation found:

- Trial participants had many barriers to work: Many recruits had not worked for 2 years, and some had never worked. It was common for recruits to have 6 or more interacting health conditions.

- Improving health condition management and achieving health referrals alongside employment support, built people’s capability and self-belief. The treatment group appreciated being able to focus on job roles that were matched to their goals and capabilities.

- Impacts on employment, health and wellbeing varied by site and trial group:

- In WMCA, where all recruits were OOW, there was a substantial and strongly significant impact on the probability of being employed for 13+ weeks over the year following randomisation.

- The SCR IW group saw less substantial and weaker impact on employment using the same measure. No impact on employment was observed for the SCR OOW group.

- Across SCR groups, strongly significant impacts were seen for health and wellbeing outcomes. These did not emerge in WMCA.

- Health outcomes produced a stronger return to society and the exchequer than employment outcomes. This led to a return-on-investment for every £1 invested in the IPS services of £0.01 in WMCA, and in SCR, of £2.02 (SCR OOW) and £2.32 (SCR IW) and £1.22 for the pooled out of work group.

- Progress amongst the treatment group on key “movement to work” measures: Trial designers anticipated that impacts would be preceded by improvements to: jobsearch capability, use of health services, and self-confidence. The evaluation showed progress amongst the treatment group on all these dimensions.

- High levels of satisfaction with IPS support, for example

- 68% of participants said that their employment specialist “understands my needs a lot”.

- 69% of participants reported that their employment specialist “has the right skills and expertise”.

- Different leadership structures and different delivery models were the factors most likely to explain the differences in impact between the sites.

- specialised employment advisers (IW or OOW but not both) and smaller caseloads enabled more employer engagement activity.

- A mix of short and longer meetings was likely to provide momentum for employment outcomes. Less frequent, longer meetings were likely to enable focus on making best use of health support, as well as wellbeing.

- At a strategic level, building integration between health and employment systems, and increasing understanding of the value of work to health and wellbeing outcomes are important factors for future delivery.

Acknowledgements

The evaluation of the Health-led Employment Trials was commissioned by the joint Work and Health Unit (WHU) which is sponsored by the Department for Work and Pensions and the Department of Health and Social Care. Throughout the design of the trials and evaluation methodology several colleagues within this directorate have made significant contributions. The authors are especially grateful to David Johnson, Huw Meredith, Chris Gunning, Anna Silk, Laura Mitzel, Tracey Gent, Nisha Patel and Karen Ruby. We are indebted to Hayley Moore-Purvis who had a critical role in the design and set-up of the information governance of the trials, ensuring its data management practices were effective, and robust.

The Office for National Statistics was the data safe haven for the evaluation, and the authors would like to thank the team involved for their work, especially Lynne Liddell.

The authors would like to thank colleagues within the Sheffield City Region (SCR) for their support with the evaluation, for taking the time to host and participate in workshops, in particular Andrea Fitzgerald, Katy Pugh, and Adam Whitworth. Within South Yorkshire Housing Association (SYHA), Niall O’Reilly and Megan Staley were hugely supportive in enabling the evaluation consortium to interview employment specialists, health partners and employers. Finally, our thanks go to everyone in these roles who participated in an interview for the evaluation.

Within the West Midlands Combined Authority (WMCA), we would like to thank the central team for their support for the evaluation, especially Anita Hallbrook and Ethan Williams. Our thanks also go to staff at the delivery partners in the region, including Remploy, Dudley and Walsall Mental Health Trust, and Prospects for their support and engagement in the evaluation activities.

We would also like to thank staff at NHS England, who part-funded the trials, and particularly to Elizabeth Wade, Elizabeth Dyer, Shabana Janjua, Kevin McKenna, Belinda McIntosh and Johanna Ejbye, for their contributions to trial development and delivery.

Our special thanks and gratitude go to all the trial recruits who took the time to participate in the quantitative and qualitative evaluation research. Some took part at several points over the course of a year, and all shared their views and experiences about their health and work so candidly. Without their participation the evaluation would not have been possible.

Lastly, the authors would like to thank colleagues within the wider research teams in the evaluation consortium. Stephen Bevan is the Chief Investigator has provided invaluable subject matter expertise to the evaluation. Emma Disley from RAND Europe made a substantial contribution in guiding the ethics processes and supporting the trials through Health Research Authority (HRA) approval. Within the Institute for Employment Studies (IES) we are especially grateful to Sara Butcher and Jade Talbot for their administrative support, and Rebecca Duffy for proofreading and formatting the reports. From the research team we are sincerely grateful to Jonathan Buzzeo, Ceri Williams, Georgie Akehurst, Kate Alexander, Rachel Cetera, Sally Wilson, Zofia Bajorak, Billy Campbell, and Rahul Shakala for their help with interviews and analysis. We are indebted to the team at Qa Research, and particularly Helen Hardcastle and Patrick Gower who supported us to recruit non-trial employers to understand their recruitment practices in the pandemic.

Any errors or omissions in this report are the responsibilities of the authors.

Authors’ credits

Becci Newton is Director of Public Policy and Research at the Institute for Employment Studies (IES) and specialises in research on unemployment, inactivity, health, skills and labour market transitions. Becci has managed the evaluation since its design and contributed to the process evaluation. She has led multiple evaluations for DWP including of the 2015 ESA Reform Trials and the Work Programme.

Rosie Gloster is a Principal Research Fellow at IES. She supported the management of the evaluation consortium and contributed to the process evaluation. She is a mixed-methods researcher specialising in employment, and careers. She has authored several reports for the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP), including the Evaluation of Fit for Work.

Joanna Hofman is a Research Leader at RAND Europe focusing on research and evaluation in the fields of employment and social policy. She has led several evaluations of the Individual Placement and Support (IPS) including of IPS for Alcohol and Drug Dependence for Public Health England (PHE). She contributed to evidence reviews that informed the trial design and this synthesis report and advised throughout the evaluation.

This report draws on all evaluation strands that were produced and authored by:

Richard Dorsett is Professor of Economic Evaluation at the University of Westminster. He has worked on numerous impact evaluations, mostly in the fields of employment, welfare and education/training. He led on the statistical design of the trials and the impact analysis.

James Cockett is a Research Fellow (Economist) at the Institute for Employment Studies. He has supported the 4-month impact analysis of the Health-led Trials. He is a Labour Economist with a particular interest in labour market transitions of disadvantaged groups. James has authored reports for both the Low Pay Commission and the Social Mobility Commission in his early career.

Charlotte Edney is a Research Fellow at IES. She completed her PhD in Economics at Lancaster University where she gained experience in using a wide range of quantitative methods. In her work she has used various UK household surveys, cohort studies and administrative data.

Helen Gray was a Principal Research Economist at IES. She has particular expertise in the causal identification of impact using quantitative methods and linked administrative data sets. As well as leading the economic evaluation of the HLTs, she was responsible for the manipulation of DWP and HMRC data for the impact evaluation.

Dan Muir is a Research Officer at IES. He has supported the evaluation’s 12-month impact analysis as well as the economic evaluation. Dan joined IES in September 2021 after completing his MSc Economics studies at the University of Bristol. He has experience working with a range of large data sets and quantitative analysis in various policy-related projects.

Matthew Gould is a Lecturer in Economics at Brunel University London. His research specialises in applying theory and computation to a range of economic problems. He has worked on several projects focused on education, employment and taxation. He led on the development and maintenance of the randomisation tool.

Joe Crowley is a Senior Researcher in the Health and Social Care team at NatCen Social Research, whose main methodological expertise lies in survey data collection and analysis. He has worked across a variety of large-scale cross-sectional surveys, including NatCen’s flagship British Social Attitudes survey and the Family Resources Survey. He has also worked on a range of mixed-methods projects, combining qualitative and quantitative methods.

Imogen Martin is a Researcher in the Health and Social Care team at NatCen Social Research. She has worked on areas across the policy spectrum including healthcare, disabilities and welfare. As part of the Health-led Employment Trials, Imogen has assisted with the delivery and analysis of the interim and final surveys.

Phoebe Weston-Stanley is a Research Assistant in the Health and Social Care team at NatCen Social Research. She has worked on projects using both qualitative and quantitative methodologies across the policy spectrum. As part of the Health-led Employment Trials, Phoebe has assisted with the analysis of the final surveys.

Dr Rosa Lau is a Research Director in the Health and Social Care team at NatCen Social Research. She has extensive experience of delivering complex applied research and service evaluations using mixed methods on areas including healthcare, public health, employment, housing and welfare.

Dr Priya Khambhaita is Co-Director of Health and Social Care at NatCen Social Research. She has 12 years of experience in conducting policy and academic research on health, social care, work, and income.

Jess Elmore is a Researcher at Learning and Work Institute. She contributed to the process evaluation. She is a qualitative researcher who has worked across a range of projects with a focus on disadvantaged or hard-to-reach groups and their access to education and employment.

Rebecca Duffy, IES Project Support Officer, proofread and formatted the report.

Glossary of terms

| Area | A defined, geographic area within a trial site |

| Base | The number of observations or cases in a sample. For example, a survey may have a base=2,300 respondents. During analysis the base may become smaller, for example if not all respondents answer a particular question, or when analysing responses from a subset of the full sample |

| Baseline data collection | Data from the baseline assessment completed by provider staff who recruited people to the trial |

| Binary variable | A variable measured with only 2 possible values, for example hot and cold, 0 and 1, or happy and unhappy. More complex variables (such as a happiness scale from 1-7) are sometimes re-coded as binary values during analysis |

| Bivariate analysis | The analysis of 2 variables for the purpose of determining the statistical relationship between them |

| Causal link | The connection between a cause and an effect |

| Clinical Commissioning Groups | Clinically-led statutory NHS bodies responsible for the planning and commissioning of healthcare services for their local area |

| Controlling for | In statistical modelling with multiple variables and factors, keeping 1 variable constant in order to examine and test the relationship and effect between other variables of interest in the model |

| Correlation | In statistics, the association or relationship between 2 variables, not necessarily causal. For example, the rings in a tree trunk increasing with the age of the tree is an example of positive correlation |

| Data set | A collection of data or information such as all the responses to a survey or all the recordings from a set of research interviews |

| Deep dive | Thematic case studies used in the process and theory of change evaluation with methods varying depending on the selected themes for investigation |

| Demographic | A particular section of the population. Also refers to characteristics of an individual of interest for research, such as age, gender, and ethnicity |

| Derived variable | A variable that was not directly asked in a survey, but created at analysis stage, for example by merging 2 or more variables |

| Descriptive analysis | Producing statistics that summarise and describe features of a data set such as the mean, range and distribution of values for variables |

| EuroQol-5D-5L (EQ5D5L) | Descriptive system for health-related quality of life states in adults, consisting of 5 dimensions (Mobility, Self-care, Usual activities, Pain & discomfort, Anxiety & depression), each of which has 5 severity levels described by statements appropriate to that dimension |

| Employment specialists | Staff employed by the trials to undertake randomisation appointments, provide IPS support to the treatment group, and undertake employer engagement |

| Final survey | The survey completed by participants 12 months after randomisation |

| Job search self-efficacy | 9 item scale to measure self-efficacy relating to finding employment |

| 4-month survey | The survey completed by trial recruits 4 months after starting the trial |

| Intervention | The work and health support provided in Sheffield City Region and the West Midlands Combined Authority as part of the trial |

| In employment/working | Those in employment full-time, part-time, or less than 16 hours a week; those who are self-employed |

| In paid work | Those in those in employment full-time, part-time, or less than 16 hours a week, not those who are self-employed |

| Individual Placement and Support (IPS) | IPS is a voluntary employment programme that is well evidenced for supporting people with severe and enduring mental health needs in secondary care settings to find paid employment |

| IPS fidelity scale | A scale developed to measure the degree to which IPS interventions follow IPS principles and implement evidence-based practice |

| Longitudinal surveys | Repeated surveys that study the same people over time |

| Multi-morbidity | The occurrence of multiple chronic conditions within the same individual with no single condition holds priority over any of the co-occurring conditions. This term has been selected as the evaluation consortium does not hold information about the main condition affecting individuals |

| Participants | Trial recruits allocated to treatment, who went on to receive support, as indicated by having 1+ meetings with an employment specialist. This is used to differentiate between those who experienced limited support beyond randomisation as opposed to those whose support was more extensive. Other terms are used to describe people taking part in the trial (recruits) and people taking part in the surveys (respondents) – see below |

| Prevalence | The extent to which something occurs in a population or group, often expressed as a percentage |

| Provider staff | Those working in provider organisations including employment specialists delivering IPS support, as well as managers and administrators |

| p-value | Used as a measure of statistical significance. Low p-values indicate results are very unlikely to have occurred by random chance. p<0.05 is a commonly cited value, indicating a less than 5% chance that results obtained were by chance. Research findings can be accepted with greater confidence when even lower p-values are cited, for example p<0.01 or p<0.001 |

| Randomised controlled trial | A study to test the efficacy of a new intervention, in which participants are randomly assigned to 2 groups: the intervention group receives the treatment, while the control group receives either nothing or the standard current treatment |

| Recruits | People who agreed to take part in the trials and who were randomised to either the treatment or control group |

| Refer / referral | A recommendation that an individual should be considered for the trial, facilitated by a means to directly connect them to a trial provider |

| Respondents | Trial recruits from the treatment or control group who were invited to take part in the evaluation and took part in the surveys. As such the descriptive analysis of the survey identifies treatment group respondents and control group respondents |

| Self-refer / self-referral | Individual applies for more information about the trial via the trial website or helpline and uses information there (phone number, web form, email) to make contact with the trial provider and request support |

| Signpost | Recommendation to an individual from a support organisation that they consider joining the trial, by providing them with information (leaflets, reference to website or helpline) leading potentially to the individual self-referring into the trial |

| Site | The trials were delivered in 2 combined authorities, which are termed sites |

| Statistical significance | Statistical significance indicates that the result or difference obtained following analysis is unlikely to be obtained by chance (to a specified degree of confidence) and that the finding can be accepted as valid. A study’s defined significance level is the probability of the study rejecting the null hypothesis (that there is no relationship between 2 variables), demonstrated by the p-value of the result |

| Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale | The SWEMWBS is a short version of the Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS). The WEMWBS was developed to enable the monitoring of mental wellbeing in the general population and the evaluation of projects, programmes and policies which aim to improve mental wellbeing |

| Survey | A research instrument used to collect data by asking scripted questions or using lists or other items to prompt responses. Can be conducted in person face-to-face, by telephone, or by postal or web-based questionnaire |

| Sustainability and Transformation Partnership | A partnership of local NHS organisations and Councils which develops proposals for improved healthcare |

| Tenure | Housing arrangement or status of an individual, for example owner-occupier, private renter, or local authority or housing association renter |

| Theory of Change (ToC) | A description and illustration of how and why a desired change is expected to happen in a particular context. It sets out the planned major and intermediate outcomes and how these relate to each other causally |

| Thrive into Work | The name given to the trial in WMCA |

| Trial arm | This is used to denote the allocation of individuals to either the treatment or control group, with these groups known as the trial arms |

| Trial group(s) | 3 trial groups are referred to in the report: 2 out-of-work (OOW) groups (one in each combined authority), and an in-work (IW) group in Sheffield City Region (SCR). These groups are pooled as All OOW and All SCR in different elements of the analysis |

| Variable | A variable is defined as any individual or thing that can be measured |

| Weighting | During analysis of survey data, adjusting for over- or under-representation of particular groups, to ensure that the results are representative of the wider population |

| Working Win | The name given to the trial in SCR |

1. Summary

1.1. Rationale for Health-led Employment Trials

In their landmark report Waddell and Burton (2006) posed the question: “Is work good for your health and wellbeing?”. The evidence reviewed clearly highlighted a link: that “work is generally good for physical and mental health and wellbeing…work can be therapeutic and can reverse the adverse health effects of unemployment”. The review also found that the quality of work is important: “The provisos are that account must be taken for the nature and quality of the work and its social context; jobs should be safe and accommodating.”

More recently, Marmot et al. (2020) provided compelling evidence of the links between quality of work and health and wellbeing. This review showed that employees in lower-status work had poorer health and lower life expectancy than those in higher-status roles, and experienced more stressors, which had health implications. Marmot’s concept of the so-called “social gradient” in health applies in organisations as well as in wider society.

People with long-term health conditions and disabilities have lower rates of labour market participation than those without. In January to March 2015, just before the health-led employment trials (HLTs) received funding for development, the difference between employment rates of non-disabled (79%) and disabled people (46.3%) – known as the disability employment gap - was 32.7 percentage points (ppts). In January to March 2022 there were an estimated 9 million working-age disabled people, of which 4.8 million were in employment (53.8%). The equivalent employment rate for non-disabled people was 82%. This means that, while the disability employment gap has decreased over the last 7 years it still stands at 28.2 ppts (ONS, 17 May 2022).

The origins of the HLTs lie in 2015, when the Work and Health Unit (WHU) – a joint unit between the Department for Health and Social Care (DHSC) and Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) working with NHS England – was established and secured funding to develop, deliver and test new ways of working across health and work to improve individual economic, social and clinical outcomes within the objective of increasing employment amongst disabled people. This funding supported the design and implementation of the HLTs which tested Individual Placement and Support (IPS) as the means to integrate employment and health support.

1.2. About IPS

IPS is a well-evidenced voluntary employment programme for supporting people with severe mental health needs in secondary care settings to find paid employment (see for example, Wallstroem et al. (2021), Bond et al. (2020), Frederick & VanderWeele (2019), Metcalfe et al. (2018), Modini et al. (2016). It is based on 8 principles:

- It aims to get people into competitive employment

- It is open to all those who want to work

- It tries to find jobs consistent with people’s preferences

- It works quickly

- It brings employment specialists into clinical teams

- Employment specialists develop relationships with employers based upon a person’s work preferences

- It provides time unlimited, individualised support for the person and their employer

- Access to specialist benefits counselling is included

(IPS Employment Centre, undated)

IPS defines competitive employment as a job that any person can apply for regardless of disability status. Jobs may be full- or part-time and self-employment is included. They should offer at least minimum wage and those entering them should receive similar wages and benefits to their co‐workers.

The HLTs tested IPS-LITE which is a time-limited service (Burns et al. 2015). They investigated whether IPS-LITE was effective in primary and community healthcare settings for people experiencing self-defined low to moderate mental and physical health conditions. The trials tested support for people who were out of work (OOW) as well as people who were in work (IW) but struggling with their health conditions at the time of entering support. They were an early attempt to expand IPS to new populations (see also, Reme et al. (2015), Otomanelli et al. (2014), Coole et al. (2012), Li-Tsang et al. (2008), Magura et al. (2007)).

A Fidelity Scale is used to measure the degree to which IPS interventions implement evidence-based practice (Becker et al, 2019). Examples of the measures include a focus on the size of caseload with highest scores available where the average caseload is less than 15 per employment specialist (score of 5), and lowest (score of 1) where employment specialists have caseloads of 41 or more. The literature shows in practice the maximum caseload varies between 20 and 25 clients per employment specialist (Burns et al., 2015; Swanson et al., 2008 cited in: Fergusson et al., 2012; Burns & Catty, 2008). When the HLTs were commissioned, it was expected that the maximum caseload for a full-time employment specialist would be 25-30 in the first year of operation, but that this could rise to 30-35 as the service matured.

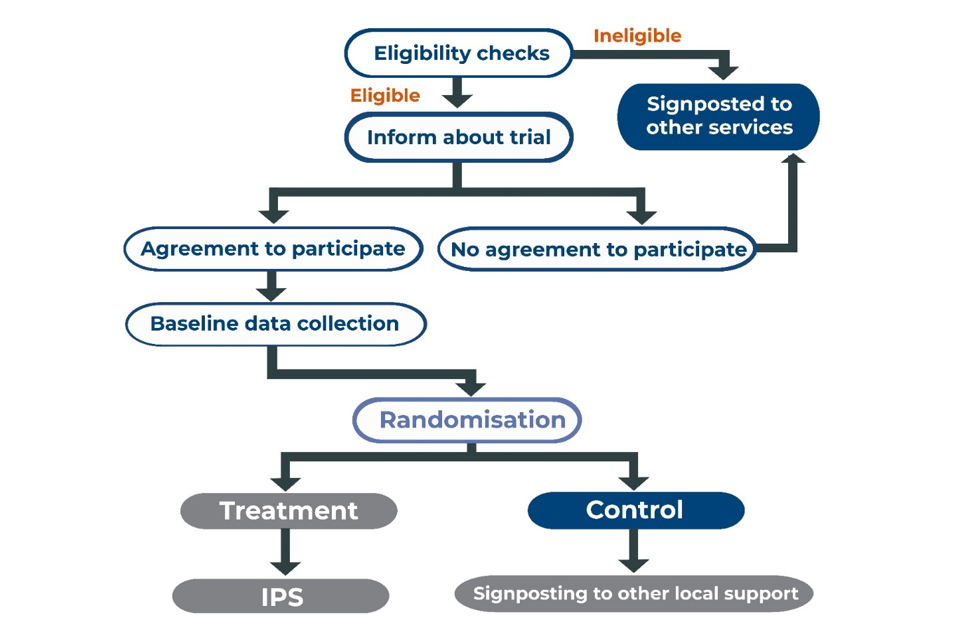

1.3. Trial design and eligibility

Two local sites – Sheffield City Region (SCR) and West Midlands Combined Authority (WMCA) – were selected in a competitive bidding process by the Work and Health Unit (WHU) to design and lead trials of new IPS-LITE services to improve health and work outcomes. Alongside, the evaluation consortium were commissioned to design and undertake a robust, national evaluation that could examine the effectiveness of the service, and detect overarching themes across the trial site, as well as local nuances.

Eligibility for the trials covered: being able to give informed agreement to take part and being aged over 18; and motivation to take part in voluntary employment support while not receiving any employment support beyond standard Jobcentre Plus services. Recruits with severe health conditions could not be included. Local eligibility in SCR covered individuals who were out of work (OOW) with a self-defined low/moderate mental health and/or physical health condition which was an obstacle to being in employment and individuals in employment (in work; IW) but who were either off sick or struggling in the workplace due to a self-defined low/moderate mental health and/or physical health condition. In WMCA the trial was open to people who had been OOW for more than 4 weeks, who wanted to find work, and who were disabled or had a health condition which presented an obstacle to them gaining work.

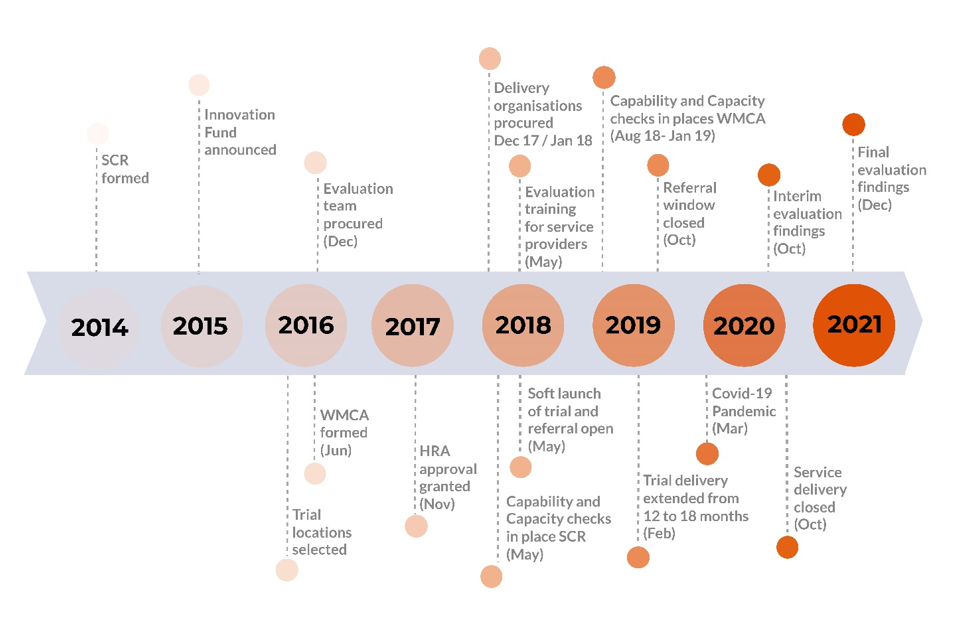

Figure 1.1 details the sequencing of the key time points during the design and implementation of the trial. The referral window for the trials was initially planned to be 12 months, but this was extended in November 2018 to cover an 18-month period (see section 1.7). The figure also illustrates the differences in the maturity of the regional organisations leading the trials, with SCR formed in 2013, and WMCA in mid-2016, and highlights the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, that is, during the support period for the final cohorts entering the trial. The first national lockdown commenced on 23 March 2020.

Figure 1.1: Key time points during the design and implementation

Key time points during the design and implementation

1.4. Evaluation purpose and approach

The national evaluation aimed to answer the following questions:

- What impact, if any, does the provision of IPS services to the client groups have upon them attaining and sustaining employment and benefit receipt?

- What impact, if any, does the provision of IPS services to the client groups, have upon self-reported health, self-management of health and wider wellbeing, and upon health service usage?

- What costs are incurred and what benefits arise from the provision of IPS services to the client groups?

- How are any impacts upon sustained employment, benefits receipt, health and wellbeing achieved? What is the causal pathway to these impacts? How might poor or negative outcomes for some in the treatment group be explained? What system-level characteristics (for example, stakeholder cooperation, relationships with employers, awareness among GPs) need to be in place if similar interventions are to be successful and adopted in other locations or settings?

These questions form the focus for this synthesis report which covers all evaluation evidence. Additionally, the synthesis is an opportunity to consider:

- What lessons can be learned from trial delivery for: disabled people’s employment, for IPS delivery and for best implementation?

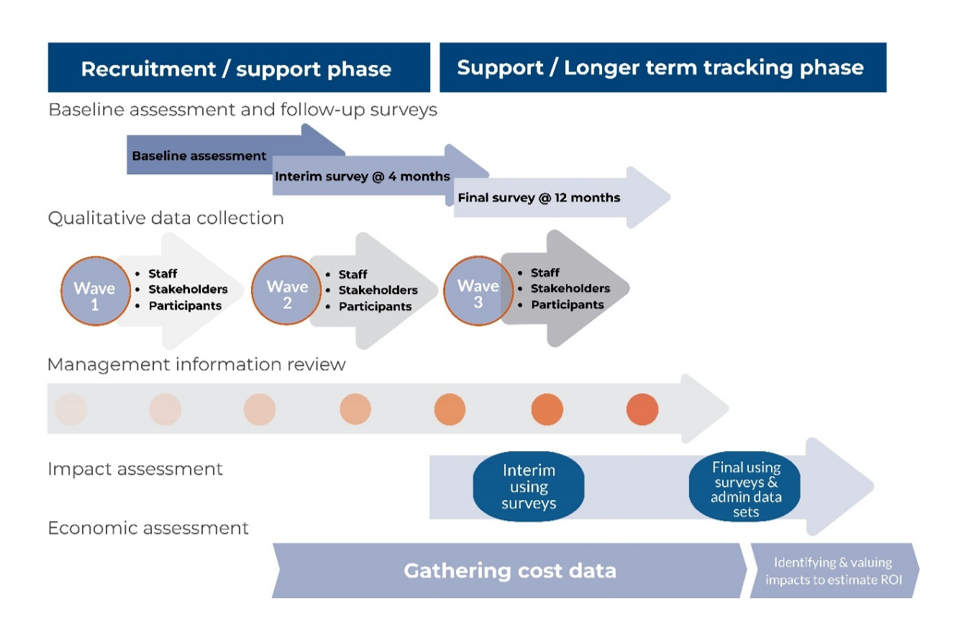

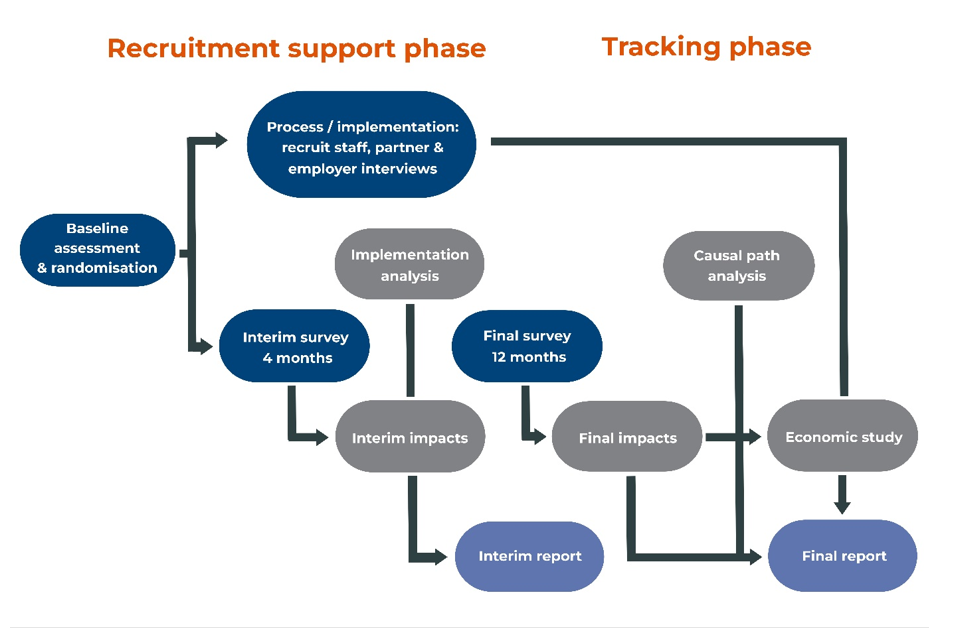

The evaluation methodology is summarised in Figure 1.2. Full details are supplied in Appendices – Chapter 6.

Figure 1.2: Overview of evaluation approach

Overview of evaluation approach

1.5. Ethics and information governance

It was crucial to ensure the trials were conducted ethically, ensured the safety and wellbeing of recruits and researchers, and obtained the necessary permissions from research governance and ethics boards. Because the trials took place in the health system, it was necessary to apply for approval from the Health Research Authority (HRA). The evaluation consortium led on identifying potential ethical issues and proposed mitigation measures. It designed key documents and materials to be used in the trial which included: Participant Information Sheets (in accessible and plain English versions); trial agreement forms (in accessible and plain English versions); trial opt-out forms; consent and opt-out materials for the research (including surveys, interviews and observations). Given the importance of these materials, multiple stakeholders were engaged in development including from the trial sites, WHU, the consortium members, wider stakeholders and patient groups.

The trial agreement materials sought permission from recruits for their personal information to be collected during the trials and retained for up to 3 years after they ended, with personal information used for service delivery, to be shared and linked to other information held by government departments and NHS Digital for research purposes. Recruits also agreed that after 3 years, an anonymised version of their information could be stored in the UK Data Archive to support future research.

The materials made clear that recruits had the right to withdraw from the trials and/or the IPS service prior to the planned end. Where they requested to withdraw, the information they had already provided up to that point would continue to be used for research and analysis and could be linked to administrative data, but these recruits were not asked to participate in any further research, such as surveys or interviews.

The trials were considered by the HRA Research Ethics Committee (REC) on 19 September 2017 and HRA approval was issued on 1 November 2017. After this, the evaluation consortium requested the necessary local Capability and Capacity (C&C) checks in each of the 16 trusts and the CCGs across SCR and WMCA. The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) requires HRA-approved research studies to provide information on the number of recruits via its Central Portfolio Management System (CPMS). These were provided monthly and enabled payments (according to agreements in the sites) to healthcare partners who referred people to the trial.

In accordance with best practice on transparency, the trials were registered on 28 October 2019. A Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP) setting out in advance how trial data would be analysed to understand impact was uploaded to the registration sites on 20 December 2019. The trials’ registrations can be found at the following links:

-

Title: Sheffield City Region Health-led Trial Trial ID: ISRCTN68347173 Date registered: 28 October 2019

-

Title: West Midlands Combined Authority Health-led Trial

Trial ID: ISRCTN17267942 Date registered: 28 October 2019

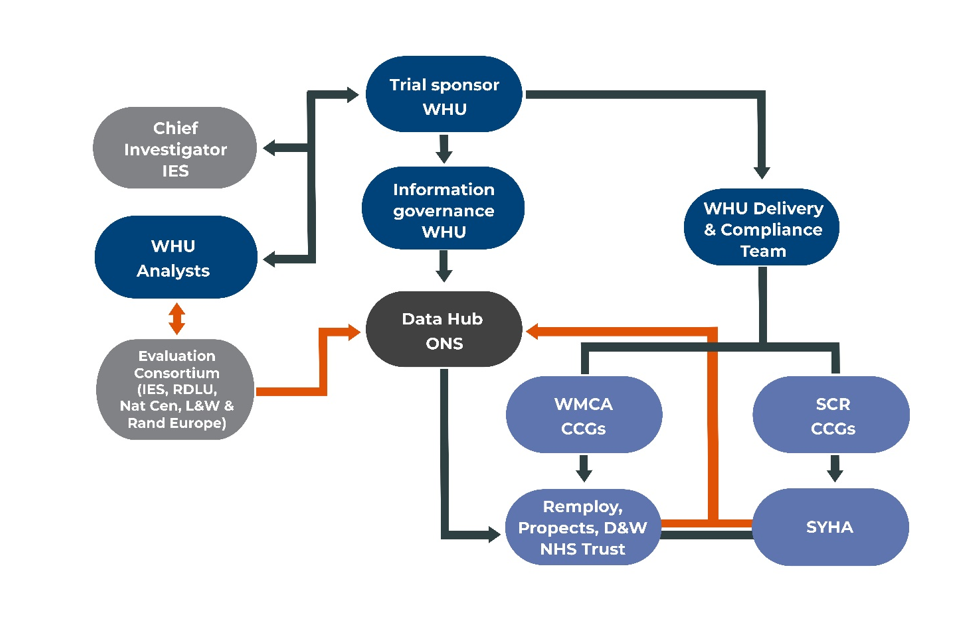

WHU was the data controller for the trials and led the design of the data architecture and data flows. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) was appointed by WHU to be the data safe haven.

1.6. Randomisation preparation and delivery

Randomisation was carried out by employment specialists during an initial meeting, using a bespoke randomisation and data collection tool provided by the evaluation consortium which was accessed via a secure website. The tool took employment specialists through the process of screening individuals for eligibility; requested and recorded agreement to take part in the trial; collected personal data, national identifiers, background information and pre-trial responses to questions covering health and wellbeing and job search self-efficacy using a baseline data collection survey. The final stage involved the tool randomising recruits either to the IPS service (the treatment group) or the control group. The randomisation used a pre-specified algorithm, specifically a permuted-block design, which assigns participants in determined blocks to achieve proportions while at the same time randomly assigning.

The evaluation consortium ran training sessions for trial staff in winter 2017 and provided written guidance and videos. It was crucial that trial staff followed these to ensure ethical engagement of recruits, to protect integrity of the trials and the reliability of the results. Training and guidance covered: an overview of the evaluation and trial; accessing and operating the randomisation tool; assessing eligibility; giving information; gaining informed agreement to take part; baseline data collection; giving the randomisation result neutrally; and, providing information on next steps.

1.7. Referrals and the trial population

The initial intention was to generate referrals into the trials across 12 months, leading to around 14,100 people being recruited and randomised.

- In WMCA, this led to a target of c.6,600 with 50% (3,300) allocated to treatment (the IPS service) and 50% to the control group

- In SCR, the target was c.7,500 recruits, with 50% (3,750) allocated to the IPS service and 50% to the control group

- Of these it was anticipated that 70% would be either unemployed and seeking work (SCR OOW, N=5,250) and 30% would be in employment but struggling/off-sick (SCR IW, N=2,250)

In each site, referral routes covered: primary care, community care (such as pain clinics and IAPT)[footnote 1]: and self-referrals. Gaining referrals proved challenging (see sections 3.1 and 3.2) and so an extension of 6 months to the referral window was granted and the expectation for recruitment was reduced to c.4,500 overall in WMCA and c.6,600 across the SCR trial groups.

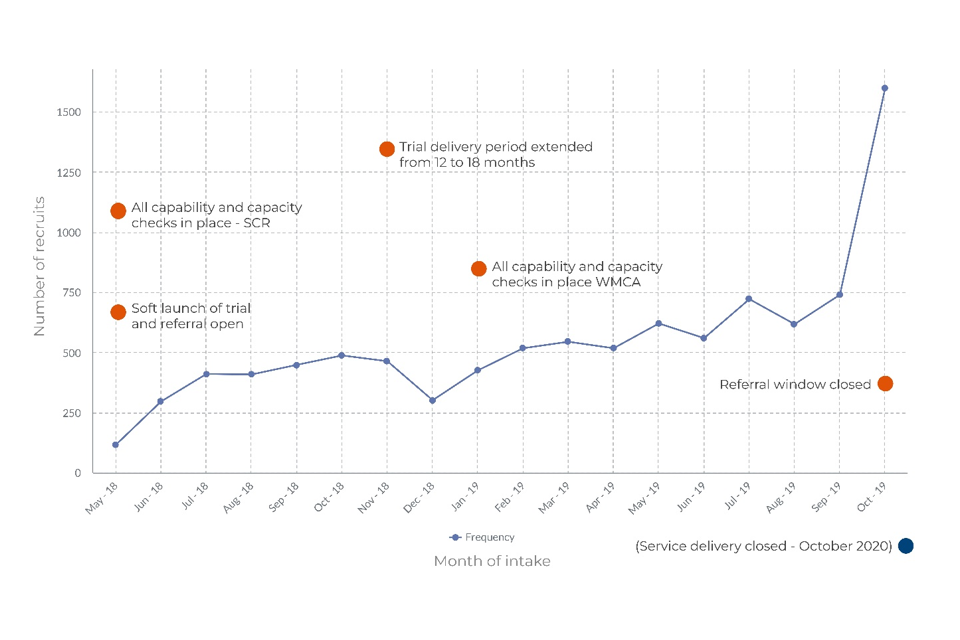

Figure 1.3 illustrates the inflow of recruits to the trial over its 18-month recruitment window. There was a notable increase in recruits in the final months of the recruitment window, with over 1,500 recruits randomised in October 2019. In total, 9,785 people were randomised, with recruits to each trial group shown in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: Number of recruits randomised, by site and trial arm

| SCR | SCR | SCR | SCR | WMCA | WMCA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IW | IW | OOW | OOW | OOW | OOW | ||

| T | C | T | C | T | C | Total | |

| Total recruits randomised | 1,260 | 1,259 | 1,799 | 1,792 | 1,837 | 1,838 | 9,785 |

Source: Baseline data collection

1.3 Trial referral over time, with key dates

Trial referral over time, with key dates

All recruits completed the baseline survey prior to randomisation. This showed a quarter (26%) were aged under 30, with 20% aged 30-39, 21% aged 40-49, and 33% aged over 50. This was broadly similar across the 3 trial groups (Table 1.2).

Table 1.2: Age of recruits, by trial group

| Age | SCR IW % | SCR OOW % | WMCA OOW % | Total % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 30 | 23 | 29 | 26 | 26 |

| 30 – 39 | 22 | 19 | 19 | 20 |

| 40 – 49 | 23 | 20 | 21 | 21 |

| 50+ | 32 | 32 | 34 | 33 |

| Base | 2,519 | 3,571 | 3,675 | 9,785 |

Source: Baseline data collection, all recruits answering this question

Over half (52%) of the recruits were male and 48% were female (Table 1.3). Recruits to the SCR IW group were more likely to be female (57%) than trial recruits overall.

Table 1.3: Gender of recruits, by trial group

| Gender | SCR IW % | SCR OOW % | WMCA OOW % | Total % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 43 | 56 | 54 | 52 |

| Female | 57 | 44 | 46 | 48 |

| Other | - | - | - | 0 |

| Base | 2,517 | 3,585 | 3,671 | 9,773 |

Source: Baseline data collection, all recruits answering this question

Nearly 4 in 5 (79%) were from white ethnic backgrounds, with 10% from an Asian or Asian British background, 7% Black or Black British, 3% Mixed, and 2% from Other ethnic groups. Recruits in WMCA were more likely to be from minority ethnic groups (36%), than in SCR (10%), reflecting the ethnic profiles of the sites (Table 1.4).

Table 1.4: Ethnic group of recruits, by trial group

| Ethnic group | SCR IW % | SCR OOW % | WMCA OOW % | Total % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 90 | 86 | 64 | 79 |

| Asian/Asian British | 4 | 5 | 18 | 10 |

| Black/African/Caribbean/Black British | 3 | 4 | 12 | 7 |

| Mixed/multiple ethnic groups | 2 | 2 | 4 | 3 |

| Other ethnic group | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Base | 2,510 | 3,578 | 3,652 | 9,740 |

Source: Baseline data collection, all recruits answering this question

All trial recruits were asked about their health conditions, illnesses, or impairments lasting 12 months or more and could list multiple conditions. Multi-morbidity (the simultaneous presence of 2 or more diseases or medical conditions) was prevalent. The most frequently cited health conditions were stress or anxiety (81%), depression (66%), fatigue or problems with concentration or memory (63%), and pain or discomfort (57%) (Table 1.5).

Table 1.5: Health conditions, illnesses or impairments lasting 12 months or more, by trial group

| Health condition | SCR IW % | SCR OOW % | WMCA OOW % | Total % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stress or anxiety | 86 | 81 | 76 | 81 |

| Depression | 68 | 68 | 64 | 66 |

| Fatigue or problems with concentration or memory | 72 | 61 | 60 | 63 |

| Pain or discomfort | 57 | 55 | 59 | 57 |

| Problems with neck or back | 40 | 37 | 41 | 39 |

| Problems with legs or feet | 36 | 37 | 40 | 38 |

| Dizziness or balance problems | 33 | 32 | 34 | 33 |

| Problems with arms or hands | 26 | 25 | 28 | 26 |

| Problems with bowels, stomach, liver, kidneys or digestion | 27 | 24 | 24 | 25 |

| Chest or breathing problems | 24 | 24 | 25 | 24 |

| Arthritis | 20 | 20 | 23 | 22 |

| Skin conditions or allergies | 23 | 21 | 20 | 21 |

| Heart or blood pressure problems | 19 | 20 | 24 | 21 |

| Learning difficulties | 11 | 20 | 21 | 18 |

| Mental health condition (other than depression/stress) | 12 | 15 | 15 | 14 |

| Other health or disability issue | 12 | 13 | 15 | 14 |

| Difficulty with seeing | 11 | 12 | 17 | 13 |

| Difficulty with hearing | 11 | 10 | 11 | 11 |

| Problems due to alcohol or drug addiction | 4 | 9 | 6 | 7 |

| Speech problems | 6 | 7 | 8 | 7 |

| Progressive illness not covered above | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Don’t know/Prefer not to say | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Base | 2,519 | 3,591 | 3,674 | 9,784 |

Source: Baseline data collection, all recruits answering this question

Recruits were also asked the extent to which their health condition(s) or disability(ies) limited their ability to carry out everyday activities. A third (33%) said a great deal, 44% said to some extent, 18% a little and 4% not at all. There were no marked differences between trial groups (Table 1.6).

Table 1.6: Extent that health condition or disability limits ability to carry out everyday activities, by trial group

| Extent | SCR IW % | SCR OOW % | WMCA OOW % | Total % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A great deal | 39 | 33 | 29 | 33 |

| To some extent | 42 | 45 | 44 | 44 |

| A little | 16 | 18 | 21 | 18 |

| Not at all | 3 | 4 | 6 | 4 |

| I do not have a health condition or disability | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Base | 2,504 | 3,547 | 3,653 | 9,704 |

Source: Baseline data collection, all recruits answering this question

On recent employment history, a majority of the SCR IW group (76%) had been in employment throughout the 2 years pre-randomisation. In the OOW groups, 50% in SCR and 59% in WMCA had not worked throughout the 2 years prior to randomisation (Table 1.7).

Table 1.7: Employment history in the last 2 years, by trial group

| Employment history | SCR IW % | SCR OOW % | WMCA OOW % | Total % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Always been in paid employment | 76 | 5 | 3 | 22 |

| Been in paid employment for more than half the time | 14 | 20 | 16 | 17 |

| Been in paid employment for less than half the time | 10 | 25 | 22 | 20 |

| Not been in paid employment in last 2 years | 0 | 50 | 59 | 40 |

| Base | 2,500 | 3,549 | 3,655 | 9,704 |

Source: Baseline data collection, all recruits answering this question

Where recruits had not been in employment continuously over the last 2 years, the most frequently cited reasons were mental health (54%), being unable to find a suitable job (which could reflect issues such as lack of local opportunities, lack of skills and experience, lack of flexible working or accommodation of health conditions) (52%), and physical health issues (43%) (Table 1.8).

Table 1.8: Reasons not in paid employment in the last 2 years, by trial group

| Reason | SCR IW % | SCR OOW % | WMCA OOW % | Total % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental health issues | 56 | 57 | 52 | 54 |

| Unable to find a suitable job | 43 | 51 | 55 | 52 |

| Physical health issues | 31 | 42 | 45 | 43 |

| Caring responsibilities | 15 | 20 | 21 | 20 |

| Education/training | 17 | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| Other | 13 | 11 | 12 | 12 |

| Don’t know/Prefer not to say | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Base | 614 | 3,378 | 3,527 | 7,519 |

Source: Baseline data collection, all recruits answering this question

All recruits were asked what had made it difficult for them to find work. Difficulty finding a suitable job was most commonly cited (77%); followed by mental health conditions (62%); lack of confidence in skills or abilities (57%); lack of qualifications or experience (52%); and a physical health condition (49%) (Table 1.9).

Table 1.9: Barriers to employment at initial appointment, by trial group

| Barrier | SCR IW % | SCR OOW % | WMCA OOW % | Total % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difficulty finding a suitable job | 59 | 82 | 83 | 77 |

| Mental health condition | 64 | 65 | 58 | 62 |

| Lack of confidence in abilities or skills | 53 | 58 | 58 | 57 |

| Lack of qualifications or experience | 41 | 55 | 57 | 52 |

| Physical health condition | 44 | 49 | 53 | 49 |

| Availability or cost of transport to work | 26 | 38 | 38 | 35 |

| Being financially being worse off | 34 | 27 | 27 | 29 |

| Caring for a child, or an elderly or disabled family member | 16 | 18 | 17 | 17 |

| Another reason | 12 | 11 | 12 | 11 |

| Availability or cost of childcare | 9 | 9 | 10 | 9 |

| Nothing | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Not applicable | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Don’t know/Prefer not to say | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Base | 2,519 | 3,591 | 3,675 | 9,785 |

Source: Baseline data collection, all recruits answering this question

Nearly 3 in 10 recruits (29%) had no or low-level formal qualifications, around half were qualified at Level 2 or 3 (48%), and 23% had higher level qualifications (Table 1.10). 76% of recruits had dependent children under the age of 16, while 24% did not (Table 1.11).

Table 1.10: Highest level of qualification, by trial group

| Qualification | SCR IW % | SCR OOW % | WMCA OOW % | Total % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Degree/higher degree/equivalent; NVQ or SVQ levels 4 or 5 | 26 | 15 | 13 | 17 |

| Higher educational qualification below degree level | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6 |

| A levels or Highers; NVQ or SVQ level 3 | 25 | 17 | 17 | 19 |

| GCSE grades A-C or equivalent | 24 | 29 | 32 | 29 |

| GCSE grades D-G or equivalent | 9 | 14 | 13 | 12 |

| Other quals inc. vocational and foreign quals below degree level | 3 | 6 | 5 | 5 |

| No formal qualifications | 6 | 14 | 15 | 12 |

| Base | 2,481 | 3,505 | 3,609 | 9,595 |

Source: Baseline data collection, all recruits answering this question

Table 1.11: Whether recruits had dependent children, by trial group

| SCR IW % | SCR OOW % | WMCA OOW % | Total % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent children | 73 | 77 | 76 | 76 |

| No dependent children | 27 | 23 | 24 | 24 |

| Base | 2,511 | 3,579 | 3,666 | 9,756 |

Source: Baseline data collection, all recruits answering this question

1.8. IPS fidelity in the trials

The IPS-25 scale (Becker et al, 2019) measures fidelity and has been shown to have good psychometric properties, including predictive validity – which means the extent to which a score on a scale or test predicts scores on agreed measure(s) (see Bond et al., 2012). The rationale for using fidelity scales to guide implementation is that interventions successfully replicating core principles of IPS will achieve similar outcomes to those found in the evidence base that establish IPS effectiveness (that is, interventions with higher IPS fidelity have better outcomes) (see Becker et al, 2019, Kim et al, 2015). The HLT design created 2 exceptions to these principles:

- trial inclusion/exclusion criteria and randomisation meant that not everyone who wanted to work was eligible for IPS support

- the IPS-LITE service model meant support was time-limited; recruits could access 9 months of support before starting/recommencing a job, and 4 months of in-work support after starting a job

The sites were responsible for assessing the fidelity of their IPS services. Fidelity reviews were undertaken by Social Finance in WMCA towards the start of delivery in August 2018 and a year later in July/August 2019. Social Finance then undertook fidelity reviews of all trial providers across WMCA and SCR in autumn 2019. The scores ranged from a ‘fair’ degree of IPS fidelity (in the range of 74-99 points scored) to ‘good’ IPS fidelity (in the range of 100-114 points scored).[footnote 2]

The 2019 reviews noted common items amongst all trial providers where IPS fidelity was scored lower:

- employer engagement and job development, where there was a reliance on applying to online opportunities rather than relationship development and accessing the hidden jobs market

- integration and links with health professionals

- lack of regular discussion with the treatment group about the impact of disclosure to employers about health conditions

1.9. Headline findings

1.9.1. Impact and economic evaluation findings

The 12-month impact analysis showed that receipt of the IPS services made a significant difference to the experience of the treatment group in both trial sites. However, the nature of impact differed by site and by trial group.

- In SCR, the results differed by trial group:

- For the SCR IW trial group, being assigned to the treatment group increased the probability of having been in work for 13 or more weeks in the year following randomisation by 3 percentage points (ppts) at the 90% significance level, that is, below the conventional 95% level. There was a small positive impact on health (0.10 standard deviations (sd)[footnote 3] significant at the 90% confidence level. Impact on wellbeing was substantial (0.18 sd) and strongly significant (99% confidence level).

- Assignment to the SCR OOW treatment group had no statistically significant effect on employment but positive small impacts on health and wellbeing (0.10 and 0.12 sd respectively) significant at 90% level.

- When considered as a whole (All SCR) no employment impact was detected but impacts on health and wellbeing were significant at the 99% level, despite being small (0.10 and 0.14 sd, respectively).

- In WMCA, where all recruits were OOW, 18% of the control group and 22% of the treatment group saw employment outcomes. This difference at 4 ppt was significant at the 99% statistical confidence level. However, in WMCA there was no discernible impact on either health or wellbeing.

- The employment impact in WMCA was substantial – meaning that recruits in the treatment group were 20% more likely to find work than those receiving business-as-usual (BAU) support. Additionally, the economic evaluation showed this employment impact was sustained at the point 21 months following randomisation and statistically significant at the 95% confidence level.

- When combined, no impact was detected on employment for the 2 OOW trial groups (All OOW) but small impacts on health and wellbeing were statistically significant (0.08 and 0.10 sd, respectively) at the 95% significance level.

- No impact was found on earnings for any group or in either site.

- The economic evaluation found that the costs of delivering the IPS services varied considerably between trial groups and the 2 sites.

- The spend per member of the SCR IW treatment group was £2,116.00.

- For the SCR OOW treatment group, it was £2,416.00 per person.

- The spend per member of the All SCR treatment group was £2,292.00.

- The spend per recruit to the treatment group in WMCA was £3,893.00. This resulted from the lower number of recruits in WMCA (1,837) compared to SCR (3,059 All SCR).

- This meant that total costs for those in the All OOW treatment group were also higher at £3,162.00 per person.

- The economic evaluation also estimated the economic benefits derived from improvements in health and the financial benefits deriving from improvements in employment. This showed that:

- The financial benefits from employment impacts (given the lack of effect on earnings), were not much greater than the costs of delivering the IPS services. For every £1 spent on the IPS services, a financial return of 2p resulted for the SCR IW trial group, and of 1p for WMCA.

- Due to the health impacts, economic returns were greater. Every £1 spent on the IPS services delivered returns of £2.32 for the SCR IW trial group, £2.02 for SCR OOW, and £1.22 for All OOW.

- Sensitivity analysis was used to quantify the statistical uncertainty around the impact estimates and therefore the benefit-to-cost ratios. This showed these were subject to significant variation and meant it was not possible to state definitively that the same results would emerge if the trial were to be re-run.

- Overall, the economic findings indicated that to generate better returns on investment, achieving health-related outcomes alongside employment outcomes from the IPS services was necessary.

- When longer-term employment outcomes (21 months post-randomisation) in the linked evaluation data set were examined, an impact on earnings was seen in WMCA shortly following the 12-month outcome measure documented by the statistical analysis plan. This may suggest financial returns are underestimated.

1.10. Accounting for differences in outcomes

The evaluation evidence was examined for factors that might be driving the differences in impact. This included searching for any effect from the COVID-19 pandemic. Some additional analyses using labour market information (LMI) showed the labour markets in WMCA and SCR were very different and recovered in different ways from the pandemic. There was a possibility that the IPS service made a greater difference on employment outcomes in a weaker labour market with low rates of employment (WMCA) than it did in a more buoyant labour market (SCR). However, this could not be stated definitively as the LMI could not be linked to the evaluation data set in any meaningful way.

Potentially supporting the emergence of health outcomes, qualitative evaluation evidence showed a greater connection between the health system and trial in SCR than in WMCA. This stemmed from local Clinical Commissioning Groups and Local Authorities collaborating on design, whereas in WMCA this was contracted out. The survey showed that recruits generally (that is, treatment and control) in SCR made greater use of health support organisations than those in WMCA. MI showed that the SCR IPS service offered longer duration but less frequent meetings than in WMCA which may have been conducive to discussing health and wellbeing and agreeing follow-up actions and referrals. In contrast, the MI showed that the IPS service in WMCA offered more frequent meetings and enrolled the treatment group into the IPS service more rapidly which meant jobsearch could also commence more quickly. The MI also showed a mix of face-to-face and telephone check-in interactions in WMCA which may have increased momentum on jobsearch.

Economic data suggested that caseloads in WMCA were smaller than in SCR. The qualitative data showed that the mixed IW and OOW caseload in SCR brought greater complexity and different practical needs that were challenging for employment specialists to manage. The qualitative and economic evidence suggested more focus on employer engagement in WMCA than in SCR, potentially due to a smaller and less complex caseload.

1.11. Lessons for the disability employment gap

The gap in employment rates between disabled and non-disabled people has been a longstanding policy challenge and the reason the trials were introduced. The tight labour market that has emerged since the pandemic suggests employers need to access a wider talent pool to fill vacancies, which may improve conditions for the employment of people with LTHC. A number of lessons can be drawn from the trials.

The evidence shows that improving health condition management and achieving health referrals alongside employment support built people’s capability and self-belief. The strengths-based approach brought by the IPS services was an important facilitator of confidence in job search capability and in feeling that work is possible. The treatment group appreciated being able to focus on job roles that were matched to their goals and capabilities.

Employment specialists’ engagement with employers, and taking a holistic view to obstacles to the labour market, helped to increase employment outcomes. Overall, the evidence suggested a need for greater differentiation, and exploration of intersectionality in the design of employment support programmes, to ensure that people from all backgrounds find the support suitable to their needs.

Identifying hidden vacancies and supporting job development was productive. There was evidence of employer and organisational confidence in employing people with LTHC increasing as a result of the IPS support received.

1.12. Lessons learned for delivery

A number of the factors that appeared explanatory for the differences in outcomes also appear in the IPS Fidelity Scale, where a higher overall score typically correlates strongly with impact on employment. Caseload is an important, determining factor in respect of time that can be spent on other activities. Higher caseloads in SCR may have meant employment specialists had less time to spend on members of the treatment group, compared with WMCA, which may have impacted on the nature and extent of employment support. Higher caseloads may have constrained the amount of employer engagement, which was less in SCR. Mixed OOW and IW caseloads in SCR added complexity as the 2 groups had different preferences and differing needs. Future implementation might benefit from smaller, specialised caseloads.

Ensuring time for employer engagement is crucial in future delivery. In both sites, employment specialists said this task was difficult, and those with less prior experience wanted more training and support on this. It was also noted that a key barrier for the recruitment of people with health conditions was employers’ limited understanding of the cost of reasonable adjustments and how the government could support these. Information sharing and time spent in discussion with employers could overcome these concerns. In SCR, employer workshops on supporting staff with mental health conditions were helpful in creating impetus on this agenda.

More generally, as it is an employment service, rather than an intervention focused on health, it is possible that a focus on health outcomes in the SCR IPS service took priority over employment outcomes, shifting the service from a ‘place then train’ to a ‘train then place’ approach for some in the treatment group. However, there was also evidence suggesting the SCR IPS service aimed for better quality work than business as usual, which if achieved should lead to better health outcomes given the social gradient within employment identified by Marmot (2020). The 12-month survey showed that the SCR OOW control group felt their employment was more precarious than the SCR OOW treatment group, feeling, for example, that work makes it harder to manage their health (44% compared with 27% in the treatment group). This focus should not be lost for future delivery if the therapeutic value of work is to be tested.

2. Main findings

2.1. The impact of the HLTs on recruits

The primary outcomes selected for the HLTs to measure effects in the 12 months following randomisation covered:

- employment – whether employed for 13 or more weeks in the 12 months following randomisation (based on HMRC PAYE RTI data) – a measure aligned with public policy measures to help individuals enter the labour market

- earnings – total earnings in the 12 months following randomisation (based on HMRC PAYE RTI data)

- health – as measured by the EQ5D5L instrument administered as part of the 12-month survey

- wellbeing – as measured by the SWEMWBS instrument as part of the 12-month survey

The results of the impact analysis are summarised in Table 2.1 below.

Table 2.1: Summary of the impacts obtained for the trials

| Employment | Earnings | Health | Wellbeing | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCR IW | 3ppt * | £442 | 0.10 sd * | 0.18 sd *** |

| SCR OOW | -2ppt | -£233 | 0.10 sd * | 0.12 sd * |

| All SCR | 1ppt | £102 | 0.10 sd *** | 0.14 sd *** |

| WMCA | 4ppt *** | £150 | 0.05 sd | 0.9sd |

| All OOW | 1ppt | -£51 | 0.08 sd ** | 0.10 sd ** |

Bold indicates impact observed; asterisks indicate level of confidence/significance associated with observed impacts as follows: * 90%; ** 95%; *** 99%. n/c – not calculated

Source: Final evaluation data set

The 12-month impact analysis showed that receipt of the IPS services made a significant difference to the experience of the treatment group in both trial sites. However, the nature of this impact differed by site, with WMCA showing strongly significant employment impact but no effect on health and wellbeing. In contrast, in SCR the results were more weighted, overall, towards health and wellbeing outcomes. A small employment impact was seen for the SCR IW group but this was below the conventional level of confidence. No significant effect was found in either site on earnings at the 12-month outcome point although the trend was positive for the SCR IW and WMCA trial groups.

- In SCR, the results differed by trial group:

- For the SCR IW trial group, being assigned to the treatment group increased the probability of having been in work for 13 or more weeks in the year following randomisation by 3 ppts at the 90% significance level, that is, below the conventional 95% level. There was a small positive impact on health (0.10 sd)[footnote 3] significant at the 90% confidence level. Impact on wellbeing was substantial (0.18 sd) and strongly significant (99% confidence level).

- In the SCR OOW group, 27% of the control group and 25% of the treatment group were in work at the 12-month point; a 2 ppt difference with business-as-usual achieving more of these outcomes – that is, being assigned to the treatment group had no statistically significant effect on employment. However, positive but small impacts were seen for health and wellbeing (0.10 and 0.12 sd respectively), which were significant at the 90% level.

- When considered as a whole (All SCR) no employment impact was detected but impacts on health and wellbeing were significant at the 99% level, despite being small (0.10 and 0.14 sd, respectively).

- In WMCA, where all recruits were OOW on joining the trial, 18% of the control group and 22% of the treatment group saw employment outcomes. The difference in these outcomes of 4 ppt was significant at the 99% statistical confidence level. However, in WMCA, while a positive trend was seen, there was no discernible impact on either health or wellbeing.

- The employment impact in WMCA was substantial at 4 ppt – meaning that recruits in the treatment group were 20% more likely to find work than those receiving business-as-usual (BAU) support.

- Additionally, analysis for the economic evaluation showed this impact to be sustained at a point 21 months following randomisation. This was statistically significant at the 95% confidence level.

- When the 2 OOW trial groups were combined (that is, All OOW which combines all WMCA recruits, and the SCR OOW recruits) the analysis showed no impact on employment. However, impacts on health and wellbeing were statistically significant (0.08 and 0.10 sd, respectively) at the 95% significance level.

The results of the economic analysis are summarised in Table 2.2 below.

Table 2.2: Summary of the costs and returns obtained for the trials

| Costs per recruit to treatment group | Financial return for every £1 spent | Economic return for every £1 spent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCR IW | £2,116 | £0.02 | £2.32 |

| SCR OOW | £2,416 | £0 | £2.02 |

| All SCR | £2,292 | n/c | n/c |

| WMCA | £3,893 | £0.01 | £0 |

| All OOW | £3,162 | £0 | £1.22 |

Bold indicates impact observed; asterisks indicate level of confidence/significance associated with observed impacts as follows: * 90%; ** 95%; *** 99%. n/c – not calculated

Source: Final evaluation data set

- The economic evaluation found that the costs of delivering the IPS services varied considerably between trial groups and the 2 sites.

- the spend per recruit to the SCR IW treatment group was £2,116.00

- per recruit to the SCR OOW treatment group the spend was £2,416.00

- this led to a per person spend of £2,292.00 for the treatment group across SCR; that is, All SCR

- the spend per recruit to the treatment group was substantially higher in WMCA at £3,893.00 per person

- the reason for these higher costs was the lower number of recruits in WMCA (1,837) compared to SCR (3,059; covering All SCR)

- this meant that total costs for those in the All OOW treatment group were also higher at £3,162.00 per person

The economic evaluation estimated that the economic benefits derived from improvements in health were worth more to society and the exchequer than the financial benefits deriving from the improvements in employment, which additionally were constrained by the limited earnings effect in either trial.[footnote 4]

The estimates showed that the financial benefits from the employment impacts were not much greater than the financial costs of delivering the IPS services. The IPS service was also more expensive to deliver in WMCA than it was in SCR, which is material as in WMCA a strong and substantial impact on employment was observed. For these reasons, the economic analysis found a very small net financial return to the IPS service, as follows: for every £1 spent on the IPS services, a financial return of 2p resulted for the SCR IW trial group, and a return of 1p resulted for WMCA. No financial return was observed for either the SCR OOW, or All OOW trial groups because no employment impact was observed at the time of measurement which was 12 months following randomisation or found in the administrative data where outcomes could be tracked up to 22 months after randomisation.

In contrast, due to health outcomes being achieved, initial analysis of the economic benefits from the IPS services suggested that every £1 spent on the IPS service delivered £2.32 of benefits for the SCR IW trial group, £2.02 for the SCR OOW trial group, and £1.22 of benefits for the All OOW trial group. The latter return was observed because when the OOW groups were pooled, a significant effect on health outcomes was detected. This was due to the combination of the impact seen in the SCR OOW trial group with the positive trend in health in WMCA.

However, while initially the economic analysis appeared to make the case that a positive net benefit resulted from the investment in the IPS service in SCR, due to the health impacts, a sensitivity analysis (in line with other analysis using Monte Carlo simulation) found statistical uncertainty around the benefit-to-cost ratios which meant it was not possible to state definitively that the same results would emerge if the trial were to be re-run. The Monte Carlo simulation randomly selects values from the probability distributions of each impact estimate, based on their standard errors 10,000 times. These distributions then simulate the distribution of benefit-cost ratios. Overall, the economic findings suggested that to generate economic benefits to society, achieving health-related outcomes alongside employment outcomes from the IPS services was necessary.

Finally, when the longer-term outcomes recorded by administrative data (at 22 months following randomisation) in the linked evaluation data set were reviewed for evidence of sustained employment, an impact on earnings was observed for WMCA shortly following the 12-month measure identified within the statistical analysis plan (SAP). This may suggest that financial returns are underestimated for WMCA in the economic evaluation.

2.1.1. Putting the impacts into context

The existing evidence base demonstrates the employment outcome used within IPS studies varies. The most common measure internationally is of competitive employment in the open jobs market of at least 1 day in the follow-up (post-placement) period (Burns et al., 2015). Given the more ambitious definition of a sustained employment outcome (13 weeks in employment), the results from HLTs are lower than the mean competitive employment rate of 55% for IPS and 25% for controls across 28 trials for people with severe mental illness (IPS Employment Centre, 2021).

It is also worth noting that as IPS is primarily an employment intervention integrated with health services, most other sources focus on employment as the primary outcome and may only explore mental health, including mental health and wellbeing, as secondary outcomes. Again, this differentiates the HLTs as employment, health and wellbeing were equal as primary outcome measures.

3. Explaining the impacts

A key question is why these differences in impact across outcome measures between trial sites emerged. The impact evaluation explored a number of theories, but not all could be investigated empirically. This analysis showed:

- The difference in health and wellbeing outcomes for the OOW groups might be explained by differences in the content of support. Service provider MI included information on the configuration of support (frequency and duration of IPS meetings) with indications of some differences between the sites. However, it was not possible to correlate these to the differential health and wellbeing impacts. Differences in the observable characteristics of the trial populations in each site were explored but did not account for the different health impacts.

- A couple of theories were likely to explain the difference in employment impacts, with compositional differences again discounted. First, the employment rate was generally higher in SCR than in WMCA across the trial period, suggesting labour market differences were important to IPS outcomes. The second centred on whether support received by the SCR OOW control group was instrumental.

- When the evaluation evidence was considered in the round, a third theory emerged that differences related to elements of IPS Fidelity may have been important to the employment impacts.

As such, a few lines of enquiry were developed for the synthesis analysis. Much of this focuses on the 2 OOW trial groups since it is the difference in their outcomes that is most puzzling. However, this does not mean the impacts and returns seen for the SCR IW group are discounted; the health and employment outcomes seen for this group alongside the tentative, net economic returns suggests that taking forward a further IPS service targeted this group could be valuable.

In the following sections, a boxed summary of key information precedes more detailed analysis.

3.1. Site level factors that might account for differences in observed health impacts

Throughout the trial surveys, health was the most commonly cited barrier to work and the descriptive analysis of the survey suggested that reducing recruits’ health barriers led to an increased capability and capacity to work. Despite this, health impacts were observed in SCR but not in WMCA.

- At baseline and at 12 months following randomisation, the SCR trial groups indicated that their mental health formed the greatest barrier to working, whereas the WMCA trial group more commonly cited physical health.

- The process evaluation and Context-Mechanism-Outcome (CMO) analysis found some evidence that the health system and IPS service were better linked in SCR than in WMCA stemming from strategic-level collaboration to design the trial.

- As IPS is a voluntary employment support provision, improvements in health would result from engagement with health services. The closer linkage to the health system in SCR – demonstrated by referral routes and greater likelihood of recruits to be engaging with health support – might lead to this.

- This was supported by 12-month survey evidence showing the SCR treatment groups made better use of health services than SCR control groups. This was not seen in WMCA. The IPS service may have enabled this capability in SCR.

For all recruits (treatment and control groups), the surveys found that health was commonly cited as the most important barrier to work. This suggests the importance of addressing health problems and improving condition management in parallel to providing employment support to secure work.

The nature of the health condition that posed the greatest barrier to work in the 12-month survey differed between sites with mental health predominating in SCR IW (23%) and SCR OOW (24%) compared with WMCA at 19% (see Table 6.8) 12-month survey report, Appendix A: Table 56). This reflected differences when recruits joined the trials: in SCR, recruits were 6-8 ppt more likely than those in WMCA to report mental health conditions.

The 12-month survey found that reducing recruits’ health barriers led to an increased capability and capacity to work. Alongside this, there was evidence that recruits (treatment and control) in SCR were better connected with the health system and made more use of health support than recruits in WMCA. This may have stemmed from the referral routes in operation in each site:

- SCR recorded more direct referrals from health settings: 42% in total (with 18% from a GP, and 24% from specialist care service)

- in WMCA, 20% of referrals came directly from health service providers (16% from a GP, and 4% from a specialist care service respectively)

These may have resulted from the early strategic collaboration between health partners in the design of the SCR trial, whereas this process was outsourced in WMCA. On this basis, it could be said that recruits in SCR were more likely than those in WMCA to be actively engaging with health services at the point of referral.

The 12-month survey also found variation in recruits’ usage of wider support between the 2 sites 12 months after randomisation. It captured use of employment and health-related support services (see Table 6.4 in the Appendix to this report).

- SCR OOW recruits were more likely to have accessed support from a GP or other primary care service than those in WMCA (47% vs 40%, respectively)

- Recruits in WMCA were more likely to have accessed support from Jobcentre Plus than the SCR OOW recruits (49% compared to 39%)

These links between the health system and IPS service may have been an important factor in health impacts being achieved in SCR, not least as IPS is an employment service. It would be expected that health improvements would stem from engaging with health sources.

Exploring this further, in SCR both IW and OOW treatment groups were more likely than the control groups to report that accessing wider health support helped them to manage their health condition or disability.

- The SCR IW treatment group was more likely than the control group to say that the wider support helped them to manage their health condition (76% vs 63%)

- The SCR OOW treatment group accessing wider support services was more likely than those accessing wider support in the control group to say that this had positively affected health condition management (71% vs 60%)

- There was no significant difference between the treatment and control group respondents in WMCA who accessed health support saying that it positively helped condition management (64% vs 63%)

This suggests that the IPS service in SCR enabled recruits to make best use of wider services to manage their health conditions. This was supported to a degree in the survey analysis. The proportion of respondents (treatment and control) saying that wider support had positively affected health condition management was greatest for the SCR IW group (70%) with a more marginal difference between SCR OOW (65%) and WMCA (63%). It could be argued that greater connectivity between the IPS service and health support in SCR may have led to better health condition management and the health impacts that were observed.

3.2. Site level factors that might account for employment impact differences

Employment impact was observed in WMCA but not for the SCR OOW group, where the best contrast exists between the populations of the 2 trials.

- As the trials’ designs did not intend referrals to be made from Jobcentres and employment support organisations, these categories were not included specifically in the MI but in an ‘other’ category. The rate of referral from other sources was substantially higher in WMCA compared to SCR.

- However, recruits’ receipt of support from Jobcentre and other employment services was captured in the surveys, with the 12-month survey showing a substantially higher proportion of recruits in receipt of this in WMCA compared to SCR.

- However, as motivation levels to find work did not vary by the type of wider support received, the differences in employment impact could not be linked to this. In sum, there was limited evidence of site level factors affecting employment impacts.

While there were differences between the sites in referral routes for the OOW trial groups, these do not make a strong case for the difference in employment impacts. In parallel to comparatively high levels of referral from healthcare services in SCR, there were lower levels from ‘other’ sources including employment services (56%). In contrast, in WMCA, 80% of referrals were made by these other sources.