Running a vehicle recovery business: driver and vehicle safety rules

Updated 12 August 2025

1. Introduction

This guide addresses some basic questions to help recovery vehicle operators and drivers.

It’s intended only to offer general help and is not a legal document. For full details of the law in respect of each aspect covered by the guide, you need to refer to the relevant legislation or get legal advice.

For many years, there’s been a great deal of uncertainty about the legal requirements in relation to operating recovery vehicles.

One of the reasons for this confusion is the various classifications of vehicles used by the recovery industry. Several definitions in the current legislation include:

- breakdown vehicles

- recovery vehicles

- specialised recovery vehicles

- road recovery vehicles

The variations in the definition are further complicated because one might refer to the construction of a vehicle and another to how a vehicle is being used.

Because of this, noncompliance has been identified both within the industry and in enforcement. For these reasons, this guide tries to introduce greater clarity on rules which, at times, can be fairly complex.

It’s also the case that some of the rules which have been in place for many years need to be interpreted in a common-sense way. So efforts to help do this have been included where appropriate.

2. Vehicle excise

2.1 What is a recovery vehicle?

The various acts and regulations which are applicable to the use of recovery vehicles are not always consistent in their definitions, or even the terminology used to describe such vehicles. In order to apply the correct rules, there are 3 main terms which need to be considered:

- recovery vehicle as defined by the Vehicle Excise and Registration Act 1994

- specialised breakdown vehicle as referred to by assimilated drivers’ hours rules

- breakdown vehicle as defined by the Goods Vehicles (Plating and Testing) Regulations 1988

According to the Vehicle Excise and Registration Act 1994, a recovery vehicle is “a vehicle which is constructed or permanently adapted primarily for any one or more of the purposes of lifting, towing and transporting a disabled vehicle”.

In physical construction, this means that a recovery vehicle could be anything from a heavy recovery vehicle, to a flatbed with ramps and winch, to a transit van and tow dolly.

Other acts and regulations mention recovery vehicles, but they all refer back to the only legal definition contained in the 1994 act.

In addition to its physical construction, a recovery vehicle must also be used for one of the following purposes:

- recovery of a broken-down (otherwise known as ‘disabled’) vehicle

- the removal of a broken-down vehicle from the place where it became disabled to premises at which it is to be repaired or scrapped

- the removal of a broken-down vehicle from premises to which it was taken for repair to other premises at which it is to be repaired or scrapped

- carrying fuel and other liquids required for its propulsion, and tools and other articles required for the operation of, or in connection with, apparatus designed to lift, tow, or transport a disabled vehicle

- at the request of a constable or a local authority empowered by, or under a statute, to remove a vehicle from a road, removing such a vehicle, which need not be a broken-down vehicle, to a place nominated by the constable or local authority

When a vehicle is being used for either of the purposes specified above, it may also carry a person who, immediately before the vehicle broke down, was the driver of or a passenger in the vehicle. That person may also be taken from where the vehicle is to be repaired or scrapped, with their personal effects, to their original destination.

It may also carry any goods which, immediately before the vehicle broke down, were being carried in the vehicle. Unlike the provision for passengers, however, there’s nothing which permits the onward transportation of goods to their original destination under the recovery definition.

The number of vehicles authorised to be carried is dictated by the Department for Transport (DfT) and is currently set at 2 including any being carried on a spectacle lift.

To clarify: a broken-down vehicle is one which cannot reasonably be driven due to mechanical failure or dangerous components, or even incapable of use in the reasoned opinion of the recovery operator.

It is not sufficient to deliberately disable a vehicle - for example, disconnect the battery - to call it disabled for the purposes of defining a recovery vehicle. However, recovery of a broken-down vehicle applies to roadside scenarios or vehicles situated within private premises.

Also, because of the time or geographical location, it may be impossible or impractical to immediately take a broken-down vehicle to a place of repair or scrappage.

In such circumstances, it would be sufficient to take a broken-down vehicle to a holding premises on the basis that onward transportation to a place for repair or scrappage was imminent.

Not only is the above definition important in classifying a vehicle in order to assess the applicable vehicle excise rate, but it is also referred to by the act pertaining to goods vehicle operator licensing to give a definition of recovery vehicle in relation to operator licensing.

Similarly, the definition is also used for defining the recovery vehicles under the Special Types General Order (STGO).

2.2 Reduced rate of vehicle excise

Vehicles qualifying as recovery vehicles, according to the definition detailed above, which have a gross weight of between 3,500kg (or 3.5 tonnes) and 25,000kg (or 25 tonnes), benefit from an annual rate of excise which is equivalent to the basic goods vehicle rate. Vehicles in excess of 25,000kg goods-vehicle weight attract an annual rate of duty equivalent to two and a half times the basic goods vehicle rate.

If the vehicle being carried is not broken down or the recovery vehicle is used for a purpose other than one of those listed, it will cease to enjoy the reduced rate of duty. The full rate of duty applicable to a goods vehicle of that weight will then probably apply.

You can find more information on vehicle tax on GOV.UK.

3. Operator licensing

Operator licensing exists to improve road safety, maintain a level playing field, and protect the environment in relation to commercially operated goods vehicles.

Some recovery vehicle operators may be in the scope of operator licensing if their operation, or part of their operation, falls outside the specific definition of recovery.

Operator licensing is not intended to cover those recovery operations which are entirely concerned with vehicle recovery as prescribed in the legal definition.

An operator’s licence is required by anyone who uses a vehicle of more than 3,500kg gross vehicle weight (GVW) (the maximum combined weight of vehicle and load) for carrying any kind of goods or burden in connection with a business.

The scheme is designed to ensure that operators of such vehicles:

- maintain them to a specified minimum standard

- operate within the constraints laid down by the relevant transport legislation

- abide by environmental rules

3.1 Recovery vehicles exemption

Recovery vehicles are exempt from operator licensing. But the starting point of the Goods Vehicles (Licensing of Operators) Act 1995 is that all vehicles over 3500kg used for the carriage of goods are in scope of operator licensing, and vehicles which are used to transport other vehicles (‘recovery’ or ‘breakdown’) fall within that definition.

It’s also the case though that the Goods Vehicles (Licensing of Operators) Regulations 1995 provides numerous exemptions from operator licensing, and one of these is ‘a recovery vehicle’.

The aforementioned act then refers to the Vehicle Excise and Registration Act for the definition of recovery.

If a vehicle’s physical construction and use are not consistent with the definition of recovery as stipulated by the Vehicle Excise and Registration Act, and it is used for transporting vehicles, the vehicle is in the scope of operator licensing.

It is not enough for a vehicle to have all the physical attributes of a recovery vehicle: it must be used for the specific purposes detailed in the definition.

Example A ‘breakdown’ or ‘recovery’ vehicle transporting a non-disabled car from one garage forecourt to another would be classed as a haulage operation, despite what the towing vehicle might look like.

Such a journey would fall within the scope of ‘carriage of goods for hire or reward’.

3.2 Exemption for police use

There’s also an exemption from operator licensing for vehicles being used by the police. For example, a vehicle seized by the police for no insurance could be recovered without the authority of an operator’s licence.

Although, if that same vehicle was subsequently moved on behalf of the owner, then the recovery operation would be back in scope.

You need an operator’s licence if you transport vehicles outside the definition of recovery, even if this is only for a short period such as a few weeks or even just one day.

3.3 Dual-purpose vehicle and trailer combinations

A dual-purpose vehicle and any trailer drawn by it is identified as being exempt from operator licensing under existing legislation. Therefore, where you use a 4x4 and trailer, an operator’s licence will not be required.

Examples of dual-purpose vehicles can include 4x4 all-terrain vehicles or even estate cars: vehicles which are constructed or adapted for the carriage of both goods and passengers. The unladen weight is 2,040kg.

3.4 Operator licensing system

The licensing system is run in the following way:

- Great Britain is divided into eight traffic areas. Northern Ireland is covered by a separate licensing system

- the person who issues licences in each area is called the ‘Traffic Commissioner’: an independent person appointed by the Secretary of State for Transport.

Find out more about operator licensing

4. Drivers’ hours and tachographs

The assimilated rules on drivers’ hours and tachographs exist to govern the driving hours, breaks and rest periods of drivers who drive commercial goods vehicles, which can include some recovery vehicles

In general, vehicles with a maximum permitted GVW exceeding 3,500kg, or vehicle and trailer combinations with a maximum permitted gross train weight of more than 3,500kg when used in connection with the carriage of goods or burden, are required to have tachographs fitted, and the drivers need to comply with assimilated drivers’ hours rules.

But there are several exemptions which apply to specific types of operation:

-

you do not have to follow these rules if you mostly use your vehicle for specialised breakdown work and drive it within 100km of your base

-

drivers of specialised breakdown vehicles who are not in scope of assimilated drivers’ hours rules are subject to GB domestic rules

-

most drivers of recovery vehicles (as defined) do not need to keep records of their domestic hours

4.1 Specialised breakdown vehicle

The assimilated drivers’ hours rules (Regulation (EC) 561/2006 as it has effect in the UK) take a slightly different perspective on recovery operations.

Rather than give an exemption to ‘recovery vehicles’, the assimilated drivers’ hours rules refer to ‘specialised breakdown vehicles’ with a further condition of ‘operating within 100km of their base’.

Whereas the definition of recovery considers the vehicle’s physical construction as well as use, the drivers’ hours exemption extends only as far as the type of vehicle.

So, as long as a vehicle’s construction, fitments or other permanent characteristics were such that it would be used mainly for removing vehicles that had recently been involved in an accident or had broken down, it could be exempt, regardless of its use. Subject to it being used within 100km of the base.

In exceptional circumstances, drivers are exempt from drivers’ hours rules where there is a ‘danger to the life or health of people or animals’ as described in The Drivers’ Hours (Goods Vehicles) (Exemptions) Regulations 1986. The exemption suspends the rules during an emergency and ends once there’s no longer a danger.

So, for example, people stranded due to severe weather would be a situation that would qualify for this exemption. Drivers should make a record clearly explaining the reason for its use.

4.2 Implications of 100km radius

With regard to the definition of ‘base’ in relation to the 100km radius threshold, the distance must be measured from the place where the vehicle is normally kept.

The 100km radius is often the cause of some difficulty where a journey exceeds that threshold.

For example, a driver who is out of scope by virtue of operating within the maximum radius for most of the day, but is required to travel outside the threshold, is then deemed to be in scope.

In situations like this, the driver is required to keep a tachograph record as soon as they know the maximum radius will be exceeded. The driver is also required to manually record all work for that day, up until the point of keeping a tachograph record.

Where a person drives a vehicle which is in scope of assimilated drivers’ hours rules, not only do the rules apply for the whole of that day, they must also abide by the rules on weekly rest for that week.

From a very basic perspective, assimilated rules require a driver to take a weekly rest period of at least 45 hours – that is an uninterrupted period which is legally referred to as a ‘regular weekly rest period’.

There are, however, various other rules which mean that a weekly rest period need not always be at least 45 hours, and these are explained later.

4.3 Record keeping and production

On any day where driving under assimilated rules is undertaken, drivers must keep a record using tachograph recording equipment. There may also be activities that must be recorded manually, for example, the situation highlighted in the section above.

Drivers are also required to keep records of all other days, including rest days, for the preceding 28 days working back from any point at which driving under assimilated rules has taken place. Such records must be made manually and must be either:

- written manually on a chart

- written manually on a printout from a digital tachograph

- made by using the manual input facility of a digital tachograph

- recorded in a domestic log book for days where a driver has been subject to the domestic drivers’ hours rules, and a record is legally required

For longer periods, for example, when a driver is on several day or weeks annual leave, an attestation form can be completed as an alternative to making a daily manual record.

The rules for using an attestation form and the EU approved version can be downloaded from the European Commission website.

Under assimilated rules drivers are required to carry with them and produce on request, the current record and the preceding 28 days’ records.

4.4 Weekly rest

The rules on weekly rest are summarised as follows:

- a driver must start a weekly rest period no later than at the end of 6 consecutive 24-hour periods from the end of the last weekly rest period

- in any 2 consecutive ‘fixed’ weeks a driver must take at least 2 regular weekly rest periods, or one regular and one reduced rest period

- a regular weekly rest period is a period of at least 45 consecutive hours (which cannot be taken in the vehicle)

- a reduced weekly rest period is a period of at least 24 consecutive hours, but less than 45 hours

- if a reduced rest is taken, the reduction must be compensated by an equivalent period taken in one block before the end of the third week following the week in question: it must be attached to another rest period of at least 9 hours duration

- a fixed week is the period 00:00 hours on Monday until 24:00 hours on Sunday

- the working week does not have to be aligned with the fixed week – midweek weekly rest periods are perfectly acceptable

- a weekly rest period which falls over 2 fixed weeks may be counted in either but not both

See an example of a weekly rest pattern

You can also find out more about drivers’ hours rules.

4.5 Relay operations

Many recovery vehicle operators transport broken-down vehicles by relay, which is a legitimate method of removing the 100km restriction in relation to the application of assimilated drivers’ hours and tachograph rules.

Example If a broken-down vehicle is required to be transported 150km, 2 vehicles could be used to complete the whole journey, and as long as both vehicles operate within 100km from their base, both drivers are out of scope.

The same rule also applies where A-frames are used, and the total weight of the towing vehicle plus broken-down vehicle are in excess of 3,500kg.

4.6 Domestic drivers’ hours rules

Generally, any vehicle or vehicle operation which is exempt from the requirements of assimilated drivers’ hours, is governed by the GB domestic drivers’ hours rules.

The domestic rules regarding goods vehicles are very straightforward and consist of a 10-hour daily driving limit and an 11-hour daily duty limit.

Furthermore, the daily duty limit is based on accumulated time, and not 11 hours from ‘clocking on’. There is, however, a requirement to have ‘adequate rest’ under working time rules.

So, for example, the following shift pattern would be acceptable: 4 hours’ work – one hour’s rest – 4 hours’ work – one hour’s rest – 3 hours’ work

Again, as recovery vehicles are deemed to be, first and foremost, goods vehicles, there’s a legal requirement for all recovery vehicle drivers to be driving in scope of the domestic drivers’ hours rules at the very least.

A recovery vehicle which merely tows, and does not carry any goods (such as tools and spare parts), would normally be classed as a locomotive, and therefore not a ‘goods vehicle’ as such.

All other recovery industry vehicles generally remain classified as goods vehicles.

The recovery industry does not enjoy any specific blanket exemption to these rules, although for drivers who do not carry out more than 4 hours of domestic driving on each day of a week (Monday to Sunday) are exempt from the daily duty limit.

Additionally, for drivers who do not drive any more than 4 hours a day and remain within a 50 km radius from the vehicle’s normal base, there’s no need to keep records on that day.

It’s also the case that drivers of vehicles which are exempt from operator licensing are not required to keep records in relation to the drivers’ hour rules.

As is the position for assimilated drivers’ hours rules, in exceptional circumstances, drivers are exempt from the domestic rules where there’s a “danger to the life or health of people or animals” as described by the Transport Act 1968. The exemption suspends the rules during an emergency and ends once there’s no longer a danger.

So, for example, people being stranded due to severe weather would be a situation which would qualify for this exemption. Any time the exemption applies, drivers should make a record with reasons for the use clearly explained.

4.7 Tow dollies and A Frames

Many breakdown companies now use light vans for private car recovery. As well as tools and spares, the vans also carry vehicle recovery systems (VRS) or tow dollies.

When the VRS is merely being carried in the vehicle and is not in use, there’s no requirement to comply with assimilated drivers’ hours and tachograph rules.

But, when the tow dolly is being used to carry a broken-down vehicle, and the vehicle is being used outside a radius of 100km from base, a tachograph needs to be installed and used. The vehicle combination will be in excess of 3,500kg, so bringing it into scope with regulation 561/2006 as it has effect in the UK.

4.8 Working time rules

In addition to the requirement to comply with either assimilated or domestic drivers’ hours rules, drivers must also comply with working time rules.

Drivers subject to assimilated drivers’ hours rules

Such drivers are subject to the Road Transport (Working Time) Regulations 2005 unless considered to be an occasional mobile worker.

The main provisions of the 2005 regulations are as follows:

- weekly working time must not exceed an average of 48 hours per week over the reference period - a maximum working time of 60 hours can be performed in any single week providing the average 48-hour limit is not exceeded

- if night work is performed, working time must not exceed 10 hours in any 24-hour period - night time is the period between midnight and 4 am for goods vehicles and between 1 am and 5 am for passenger vehicles: the 10-hour limit may be exceeded if this is permitted under a collective or workforce agreement

- mobile workers must not work more than 6 consecutive hours without taking a break

- if your working hours total between 6 and 9 hours, working time should be interrupted by a break or breaks totalling at least 30 minutes

- if your working hours total more than 9, working time should be interrupted by a break or breaks totalling at least 45 minutes

- breaks should last at least 15 minutes

- regulations on rest are the same as assimilated or AETR drivers’ hours rules

- records need to be kept for 2 years after the period in question

The reference period for calculating the 48-hour week is normally 17 weeks, but it can be extended to 26 weeks under a collective or workforce agreement.

There’s no ‘opt-out’ for individuals wishing to work longer than an average 48-hour week, but breaks and ‘periods of availability’ do not count as working time.

Generally speaking, a period of availability (POA) is waiting time, the duration of which is known about in advance.

Examples of what might count as a POA are:

- accompanying a vehicle on a ferry crossing

- waiting while other workers load/unload your vehicle

For mobile workers driving in a team, a POA would also include time spent sitting next to the driver while the vehicle is in motion (unless the mobile worker is taking a break or performing other work - for example, navigation).

In addition, mobile workers are affected by 2 provisions under the Working Time Regulations 1998. These are:

- an entitlement to 5.6 weeks’ paid annual leave

- health checks for night workers

Drivers who only occasionally drive vehicles subject to assimilated drivers’ hours rules may be able to take advantage of the exemption from the 2005 regulations for occasional mobile workers.

A mobile worker is defined as being occasional if they:

- work 10 days or less within scope of assimilated drivers’ hours rules in a reference period that is shorter than 26 weeks

- they work 15 days or less within scope of assimilated drivers’ hours rules in a reference period that is 26 weeks or longer

Drivers subject to GB domestic drivers’ hours rules

Such drivers are subject to 4 provisions of the Working Time Regulations 1998, which are:

- weekly working time, which must not exceed an average of 48 hours per week over the reference period (although individuals can ‘opt out’ of this requirement if they want to)

- an entitlement to 5.6 weeks’ paid annual leave

- health checks for night workers

- an entitlement to adequate rest

Adequate rest means that workers should have regular rest periods. These rest periods should be sufficiently long and continuous to ensure that workers:

- do not harm themselves, fellow workers or others

- do not damage their health in the short or long-term

The reference period for calculating the 48-hour average week is normally a rolling 17-week period. However, this reference period can be extended up to 52 weeks under a collective or workforce agreement.

The 1998 Regulations do not apply to self-employed drivers. You’re self-employed if you’re running your own business and are free to work for different clients and customers.

5. Roadworthiness

Many recovery vehicles enjoy several exemptions from aspects of the legislation which apply to conventional goods vehicles, but users still need to be vigilant to good vehicle maintenance.

It’s good practice to form the habit of frequent basic checks, as detailed below, before using your recovery vehicle

Good vehicle maintenance will ensure conformance to legal requirements and a reduced burden imposed by enforcement authorities.

5.1 Annual testing

Breakdown recovery vehicles are no longer exempt from the requirements of plating and testing.

There will be a phased approach up to 20 May 2019 for some vehicle types, to make sure that industry has more flexibility to balance out the testing of their fleet over a longer period.

However, the vehicle must have passed an annual test by the time its tax needs to be renewed for the first time after 20 May 2018.

Example If the vehicle’s tax expires on 31 January 2019, the vehicle must have passed its annual test by then.

All previously exempt vehicles must have a current test certificate before 20 May 2019.

Vehicles in this category are:

- mobile cranes (those fitted on a truck-derived chassis)

- breakdown vehicles

- engineering plant

- tower wagons

- road construction vehicles

- electrically propelled vehicles (registered since 1 March 2015)

- motor tractors and heavy and light locomotives - exempted under sections 185 and 186(3) of the Road Traffic Act (RTA) 1988

- heavy goods vehicles on some previously exempted Scottish Islands

5.2 Walkaround checks

To help make sure their vehicles remain legal, drivers should carry out a ‘first use’ (walkaround check) before the vehicle is used on the road at the start of their duty.

As drivers and vehicles can be swapped around during a shift, best practice would be for the driver to carry out a walkaround check before he uses any vehicle for the first time.

In busy periods, or when weather conditions are poor, more frequent checks may be needed to make sure the vehicle is roadworthy at all times.

These checks should include as a minimum the condition of lights, tyres, checks for air and fluid leaks, mirrors and windscreen washers/wipers. A check of any recovery equipment on the vehicle and its security should also be checked.

As most recovery vehicles will not be operated under the authority of an operator’s licence, and therefore not required to have a formal maintenance regime, routine maintenance and safety inspections should remain a priority.

As recovery vehicles can be used in arduous conditions operators should employ a system of routine vehicle safety and maintenance checks. The system will ensure that the vehicles are in a fit state to be used on the road and will be able to perform their intended duties without problems.

There can be nothing worse for a recovery operator than having to have their recovery vehicle recovered by another! If the vehicle is checked at the roadside by a DVSA examiner and found not to comply with the relevant C&U regulations, the vehicle could be prohibited.

The driver could also be issued with a fixed penalty, which may result in penalty points attached to their driver licence. Additionally, the vehicle could be immobilised, which would involve paying a release fee before the vehicle could be moved.

Guidance on maintenance standards is available in the guide to maintaining roadworthiness, and for guidance on prohibition, standards see the categorisation of vehicle defects.

5.3 What to check during a walkaround check

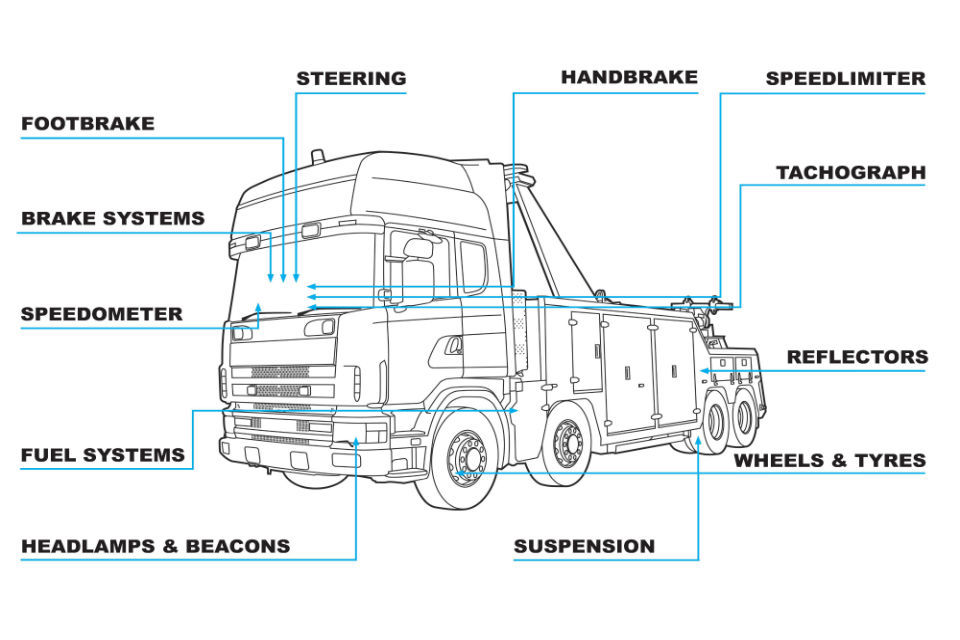

A diagram of the drivers’ daily walkaround check for recovery vehicles.

Brake systems

Check for air and fluid leaks and drain air tanks if required.

Fuel systems

Check that the fuel cap has a seal fitted and has no obvious fuel leaks. Check that no black smoke is coming from the exhaust pipe as well as the security and condition of the exhaust system.

Headlamps, lamps and beacons

Check that they work and are the right colour. Look for faded and broken lenses.

Parking brake (handbrake)

Regular use of your vehicle can help keep the handbrake efficient. Check the condition of the parking brake (handbrake) brake application.

Reflectors

Check for obvious missing reflectors at the rear and sides of your vehicle.

Service and secondary brakes (footbrake)

Regular use of your vehicle can help maintain the braking efficiency by preventing the moving parts of the braking system from seizing.

Speed limiter

If the vehicle has a speed limiter installed, check it has the appropriate calibration plaque and seal.

Speedometer

Make sure the speedometer illuminates.

Steering mechanism

Check for obvious oil leaks and any unusual knocking noises when driving.

Suspension

Check to see if the vehicle is sitting square or lopsided. Listen for knocking sounds when the vehicle is in motion.

Tachograph

If there is a tachograph installed, check to see that your use of the vehicle makes it exempt. If your vehicle is fitted with a tachograph but you only use the instrument as a speedometer, you must ensure that all the seals are intact and that it has been calibrated and fitted with both the calibration and K factor plaques.

Wheels and tyres

Check the wheel nuts for security and ensure the tyre pressures are correct. Use your vehicle regularly and park with the wheels in alternating resting positions. Parking your vehicle out of direct sunlight can also help your tyre sidewalls from perishing. Check tyre tread depth is at least over 1mm.

5.4 Braking requirements

A broken-down vehicle towed behind a recovery vehicle is viewed as a trailer in legal terms. Ordinarily, a trailer would need to comply with the braking requirements as stipulated by the Road Vehicles (Construction and Use) Regulations 1986.

Broken-down vehicles, however, are exempt from the Construction & Use (C&U) braking requirements. Therefore, broken-down vehicles can be towed legally by recovery vehicles using spectacle lifts, A-frames, or tow dollies without the need for overrun braking systems.

Where recovery vehicles are used to transport non-broken-down vehicles, there’s no legislative provision which permits recovery vehicles using spectacle lifts, A-frames or tow dollies to operate without overrun brakes. This effectively means that all towed vehicles above 750kg need to comply with the C&U braking requirements for trailers, which is not in practice feasible in the majority of cases.

6. Vehicle weights

Recovery vehicle operators and drivers need to be vigilant to maximum vehicle weights, as many could be overloaded on a regular basis.

The maximum permitted gross and individual axle weights must be complied with.

The combined actual weight of towing vehicle and trailer (or broken-down car) should never exceed the maximum train weight of the towing vehicle.

It’s the actual weight of the vehicle and load which is important in determining a vehicle’s compliance with legal weight thresholds, not the potential carrying capacity.

For example, a towing vehicle with a maximum gross weight of 3,000kg and a maximum train weight of 5,000kg could tow an unladen or partially loaded trailer with a maximum gross weight of 3,500kg.

But if both the vehicle and trailer in the combination were loaded to their respective maximum gross weights, then the combination’s actual train weight would be 6.5 tonnes, exceeding its maximum permitted train weight by 1,500kg.

Heavy recovery vehicles are governed by the Special Types General Order (STGO) when the total train weight of towing vehicle and casualty vehicle exceeds 44,000kg.

The law states that goods vehicles should never be loaded in excess of their maximum permitted ministry plated weights, or manufacturers plated design weights.

Weight limits exist to:

- reduce damage to roads and bridges

- protect the environment

- improve road safety

- help ensure fair competition

Manufacturers or ministry plates specify the weights which should be adhered to on every vehicle. For example, a vehicle manufacturer’s plate will give you the information about the appropriate weights relating to your vehicle.

Trailers may also have plates showing similar information with regard to the maximum weight they can carry, together with the maximum capacity of each axle.

These weights must not be exceeded on public roads. It’s important to remember that they include:

- the driver

- any passengers

- loads and fuel

You can find out more from the quick guide to towing trailers: non-articulated.

7. Other requirements

7.1 Load security

The principles of load security apply not only to conventional goods vehicles but also to recovery and broken-down vehicles. For example, scrap cars are particularly notorious for parts falling from them, or whole vehicles parting from the spectacle lifts, so measures to reduce this risk should always be an important consideration.

A load is deemed to be insecure if, in legislation terms, it can be said to be “likely to cause danger or nuisance to any person”, or more seriously “is such that it involves a danger of injury to any person”.

Load securing is achieved by using the load securing system. This consists of one or more of the following:

- the vehicle structure

- intermediate bulkheads, chocks, wells, blocking or dunnage

- lashings or similar systems

The weight of the load alone is not enough to prevent movement. Heavy loads can and do move under normal driving conditions.

When trying to determine whether or not a load is sufficiently restrained drivers should ask themselves the following questions:

- can the load slide or topple off the side

- can the load slide or topple forward or back

- is the load unstable

- is load securing equipment in poor condition

- is there anything loose that might fall off

If the answer to any of these questions is yes, then immediate steps should be taken to rectify the problem.

The load does not necessarily have to have already moved for it to present a likely risk of harm or nuisance as defined under the regulations. If it has already moved, however, then the securing system is obviously inadequate.

You can find more information on safe loading in load securing: vehicle operator guidance.

8. Heavy recovery vehicles

Heavy recovery vehicles can be used when the total train weight of the towing vehicle and the casualty vehicle are more than 44,000kg.

Heavy recovery vehicles must meet the requirements set out in Schedule 4 of the Special Types General Order (STGO).

A heavy recovery vehicle must be either:

- a locomotive vehicle with an unladen weight over 7,370kg, not built to carry a load

- a motor vehicle of category N3 (heavy goods vehicle exceeding 12 tonnes)

- a vehicle-combination comprising a motor vehicle of category N3 and a trailer of category O4 (trailer exceeding 10 tonnes)

The vehicle should also:

- be specially designed and constructed for recovering broken-down road vehicles or is permanently adapted for that purpose

- be fitted with a crane, winch or other lifting systems specially designed to be used for recovering another vehicle

- meet the requirements for registered use as a recovery vehicle under Part 5 of Schedule 1 to the Vehicle Excise and Registration Act 1994(1)

A heavy recovery vehicle must not carry or tow any load or transport any goods or burden other than:

- its own necessary gear and equipment

- a broken-down vehicle or vehicle combination when taking it to a place agreed with the owner or driver of the vehicle, or when taking it to be repaired

8.1 Notify road and bridge authorities when using a heavy recovery vehicle

When the combined weight of the recovery vehicle and the vehicle that has broken down is over 44,000kg, you must:

-

Notify the authority responsible for the roads as detailed in Schedule 9 of the STGO.

-

Call the authority responsible for the roads to get permission to use the roads immediately to tow the vehicle to the nearest safe place.

When you do not need to notify road and bridge authorities

You can use a recovery vehicle without notifying authorities if the police ask you to clear the area if all of the following apply:

- a civil emergency or road traffic accident has happened

- there is a danger to the public due to the emergency or accident

- the vehicle is used on roads within 24 hours of the request being received

- it is not reasonable for the vehicle to meet the authorisation requirements within this time

8.2 Recover and repair the broken down vehicle

When recovering a vehicle using a drawbar or lift-and-tow method, you must not carry or tow the vehicle any further than is necessary to clear any road obstructed by it. For example, it could be taken to the nearest services or layby.

The vehicle must then be repaired or the vehicle combination separated and transported onwards while following the Road Vehicles (Construction and Use) Regulations 1986, as amended.

9. Construction

A road-recovery vehicle must be:

- a wheeled vehicle fitted with pneumatic tyres (tyres inflated with air)

- fitted with a warning beacon emitting an amber light

- equipped with a plate that specifies the maximum weight that may be lifted by any crane, winch or other lifting systems it’s fitted with

At any time when a broken-down vehicle or vehicle combination is being towed by a road-recovery vehicle, it’s braking system must not be operated by any device other than an approved brake connection point that is fitted to both it and the recovery vehicle.

An approved brake connection point means a device which:

- is approved by the manufacturer of the vehicle

- fitted to the vehicle in the course of its construction or adaptation

It’s specially designed for use in the course of recovering broken-down vehicles. It allows the braking system of the broken-down vehicle to be safely and effectively controlled from the road-recovery vehicle.

A road-recovery vehicle must not tow a broken-down vehicle if its weight, combined with the weight of the vehicle or vehicles being towed, would exceed the maximum train weight shown on the plate fitted to it in compliance with the C&U regulations.

9.1 Beacons

When a recovery vehicle is used on roads, the beacon fitted to it must be kept lit if:

- it’s stationary at the scene of the breakdown

- it cannot maintain speeds appropriate to the road it’s on

The beacon can be switched off if:

- the vehicle does not present a hazard to other road users

- it’s likely to confuse or mislead them.

Misuse of beacons diminishes their effectiveness. Do not illuminate them if there’s no hazard.

9.2 Maximum width

The overall width of a road-recovery vehicle must not exceed the limits imposed by the C&U regulations.

9.3 Maximum length

The overall length of a road-recovery vehicle must not exceed 18.75 metres. This does not apply to the combined length of the vehicle together with any broken-down vehicle or vehicle-combination carried or towed by it in the course of a recovery.

9.4 Maximum vehicle weight

The gross weight of a road recovery vehicle must not exceed:

- 36,000kg in the case of a locomotive, the weight of which is transmitted to the road surface through 3 axles

- 50,000kg in the case of a locomotive, the weight of which is transmitted to the road surface through 4 or more axles

- 80,000kg in the case of a vehicle combination comprising a category N3 motor vehicle and a category O4 trailer of, where the weight of the combination is transmitted to the road surface through 6 or more axles

- in any other case, the maximum authorised weight for the description of the vehicle in question

9.5 Maximum axle and wheel weights

The distance between any 2 adjacent axles of a road-recovery vehicle must not be less than 1.3 metres.

The axle weight must not exceed 12,500kg, and the wheel weight must not exceed 6,250kg

Where a road-recovery vehicle has axles in 2 or more groups the:

- distance between the adjacent axles in any group must not be less than 1.3 metres

- the sum of the weights transmitted to the road surface by all the wheels in any group must not exceed 25,000kg

If a road-recovery vehicle has only one front steer axle, that axle must carry at least 40% of the maximum plated axle weight.

If the vehicle has 2 or more front steer axles, all those axles taken together must carry at least 40% of the plated weight.

9.6 Speed restrictions

Speed limits in built-up areas

| Type of vehicle | Built-up areas mph in England and Scotland (km/h) | Built-up areas mph(km/h) in Wales |

|---|---|---|

| Recovery vehicle without a trailer not more than 7.5 tonnes train weight | 30 (48) | 20 (32) |

| Recovery vehicle with a trailer or towing a broken-down vehicle not more than 7.5 tonnes train weight | 30 (48) | 20 (32) |

| Recovery vehicle with or without a trailer more than 7.5 tonnes train weight | 30 (48) | 20 (32) |

| Road recovery vehicles being used under STGO regulations | 30 (48) | 20 (32) |

Speed limits on single and dual carriageways and motorways

| Type of vehicle | Single carriageways mph (km/h) | Dual carriageways mph (km/h) | Motorways mph (km/h) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recovery vehicle without a trailer not more than 7.5 tonnes train weight | 50 (80) | 60 (96) | 70 (112) |

| Recovery vehicle with a trailer or towing a broken-down vehicle not more than 7.5 tonnes train weight | 50 (80) | 60 (96) | 60 (96) |

| Recovery vehicle with or without a trailer more than 7.5 tonnes train weight | 50 (80) in England and Wales 40 (64) in Scotland |

60 (96) in England and Wales 50 (80) in Scotland |

60 (96) |

| Road recovery vehicles being used under STGO regulations | 30 (48) | 30 (48) | 40 (64) |

All other speed limits should be observed where appropriate.

Find out more about speed limits

9.7 Speed limiters

Since 1 January 2008, all goods vehicles with a gross weight in excess of 3,500kg have needed a speed limiter installed and working.

The set speed of a limiter depends on the age of the vehicle, and the exact requirements are detailed in the table below.

Road-recovery vehicles are exempt by STGO.

| Gross vehicle weight | First registered | Set speed |

|---|---|---|

| All vehicles over 3,500kg | From 1 Jan 2005 | 90km/h |

| Vehicles between 3,501kg and 7,500kg | From 1 Oct 2001 and 31 Dec 2004 | 90km/h |

| Vehicles between 7,501kg and 12,000kg (with Euro 3 diesel or gas engine) | Between 1 Aug 1992 and 30 Sept 2001 | 90km/h |

| All vehicles between 7,501kg and 12,000 kg | Between 1 Oct 2001 and 31 Dec 2004 | 90km/h |

| All vehicles over 12,000kg | From 1 Jan 1998 | 90km/h |

9.8 Seat belts

Drivers and passengers of recovery vehicles need to follow the legal guidance on seatbelt use.

You can be fined up to £500 if you do not wear a seat belt when you’re supposed to.

9.9 Carrying passengers in towed vehicles

Passengers can be carried in a broken-down vehicle if the speed does not exceed 30mph.

9.10 Driver licensing

You need to make sure that you have the correct licence for the size and type of vehicle you’re using, and how it’s being used.

The driver of a vehicle with a gross vehicle weight of up to 3,500kg only needs a category B licence (ordinary private car licence).

Vehicles between 3,500kg and 7,500kg can be driven by holders of C1 category licences. Drivers covered by this category are permitted to tow trailers of up to a maximum gross weight of 750kg.

Drivers who passed their driving test for a category B licence after 1 January 1997 stopped receiving automatic entitlement to drive category C1 and C1+E vehicles.

With the exception of those drivers with category C1 entitlement, all drivers of goods vehicles with a maximum gross weight of more than 3,500kg need a category C licence.

LGV vocational licences are not required by drivers of vehicles which conform to all of the following criteria:

- designed for raising a broken-down vehicle partly from the ground and drawing it when raised (whether by partial suspension or otherwise)

- used solely for dealing with broken-down vehicles

- an unladen weight not in excess of 3,050kg

- not used to carry any load other than a broken-down vehicle

In cases where these criteria are not met, normal rules for the application of vocational licensing apply. For example, a recovery vehicle with a GVW of 17,000kg towing any broken-down vehicle over 750kg GVW would need to be driven by a driver with full C+E entitlement.

Find out more about driving licences

9.11 Driver CPC

The rules on Driver CPC for recovery vehicles reflect those on driver licensing. So Driver CPC is applicable to those drivers who are in scope of LGV licensing, and that includes drivers involved in vehicle recovery.

Drivers of recovery vehicles who gained their vocational LGV licence before 10 September 2009 have ‘acquired rights’ that last for 5 years. Since September 2014 however, those drivers have needed a Driver CPC which can be achieved by completing 35-hours of periodic training.

After completing the required training, drivers will be sent a Driver CPC card to prove they are the holder of the Driver CPC.

This Driver CPC card needs to be carried at all times whilst driving professionally.

Find out more about Driver CPC

9.12 Trailer boards

The Road Vehicle Lighting Regulations state that every light and reflector fitted to a motor vehicle must be kept in a good working order and clean whilst in use on a road. However, the regulations give a specific exemption to broken-down vehicles being towed:

- between sunrise and sunset, no obligatory lights need to be kept working

- between sunset and sunrise the regulations only state that the rear position lights and reflectors are in good working order

However, best practice would suggest that a fully-functioning trailer board is used at the rear of the recovered vehicle to prevent a danger to other road users.

Trailer boards are designed to replicate a vehicle’s lights. Place one in a prominent position at the back of the vehicle being towed if any of its lights are obscured.

Failure to do so could lead to prosecution for using a vehicle in a dangerous condition.

10. Enforcement

DVSA has the power to prohibit vehicles from further use where serious mechanical defects, overloading and drivers’ hours offences are detected.

As a last resort, DVSA may even consider impounding a vehicle where it’s being used without an operator’s licence.

This is only likely to occur where an operator has failed to apply for a licence even after being prosecuted for the offence.

On 1 April 2009, the graduated fixed penalty, deposits and immobilisation scheme (GFP/DS) was launched. The Road Safety Act 2006 introduced powers to enable both police constables and DVSA examiners to:

-

issue fixed penalties for both non-endorsable and endorsable offences

-

request immediate financial deposits from non-UK resident offenders (equivalent to an on-the-spot fine), either in respect of a fixed penalty or as a form of security for an offence which is to be prosecuted in court

They can also immobilise vehicles in any case where a:

- driver or vehicle has been prohibited from continuing a journey

- driver declines to pay the requested deposit

There are various offences covered by the scheme which are all driver related - the scheme includes offences such as failing to have a tachograph installed, failing to produce a driver CPC and failure to comply with the C&U regulations.

You can be fined up to £5,000 and be sent to prison for 2 years if DVSA prosecutes you for some offences.