Country policy and information note: actors of protection, Ethiopia, February 2024 (accessible)

Updated 25 September 2025

Version 2.0

February 2024

Executive summary

Ethiopia has a set of laws that criminalise behaviour and acts that might be persecutory or cause serious harm. The constitution recognises secular, religious and traditional courts. The law provides for the right to a fair public trial, the presumption of innocence, and an independent judiciary. However due process rights are not always respected while judicial independence is impaired by political interference, corruption and bribery. A weak and overburdened judicial system contributes to slow prosecutions and sometimes lengthy detentions without charge or trial, undermining the courts’ effectiveness. Access to formal judicial systems is limited in rural areas and for women.

The government has taken various measures to improve prison conditions and passed a law to protect the rights of detainees. Prison conditions, however, remain dire and life threatening.

The security sector consists of the Ethiopian National Defence Forces (ENDF), Ethiopian Federal Police (EFP), State (regional) police forces, local militias and National Intelligence and Security Service. The EFP is responsible for maintaining law and order at federal level and in any region when there is a deteriorating security situation beyond the control of the regional government. It also investigates crimes under the jurisdiction of federal courts. The State police maintain law and order in the regions. They vary in size, structure, training and how they fulfil their role. Local militias operate across the regions in co-ordination with regional police forces or act on behalf of the ethno-linguistic communities they represent. The ENDF sometimes provides internal security to support the police. There are internal and external oversight mechanisms over security forces. The Ethiopian Human Rights Commission receives and investigates complaints and state and federal institutions have implemented some of its recommendations regarding human rights protections and prison conditions.

The government generally retains control over federal security forces but in some areas central government control is limited over regional forces due to ethnic and regional loyalties. The effectiveness of the security forces is undermined by a lack of resources, training and corruption. The army and police have been responsible for harassment, excessive use of force, torture and extra-judicial killings especially in areas of internal conflict such as Tigray and Amhara. Oversight is limited and impunity is a significant problem.

In general, the state is willing and able to provide protection, which is accessible, from non-state actors. The onus is on the person to demonstrate otherwise. However, the state’s ability to provide protection is likely to be limited in areas affected by conflict.

Updated on 12 January 2024

Assessment

About the assessment

This section considers the evidence relevant to this note – that is information in the country information, refugee/human rights laws and policies, and applicable caselaw – and provides an assessment of whether, in general:

- a person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies)

Decision makers must, however, still consider all claims on an individual basis, taking into account each case’s specific facts.

1. Material facts, credibility and other checks/referrals

1.1 Credibility

1.1.1 For information on assessing credibility, see the instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

1.1.2 Decision makers must also check if there has been a previous application for a UK visa or another form of leave. Asylum applications matched to visas should be investigated prior to the asylum interview (see the Asylum Instruction on Visa Matches, Asylum Claims from UK Visa Applicants).

1.1.3 In cases where there are doubts surrounding a person’s claimed place of origin, decision makers should also consider language analysis testing, where available (see the Asylum Instruction on Language Analysis.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – Start of section

The information in this section has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – End of section

1.2 Exclusion

1.2.1 Decision makers must consider whether there are serious reasons for considering whether one (or more) of the exclusion clauses is applicable. Each case must be considered on its individual facts and merits.

1.2.2 If the person is excluded from the Refugee Convention, they will also be excluded from a grant of humanitarian protection (which has a wider range of exclusions than refugee status).

1.2.3 For guidance on exclusion and restricted leave, see the Asylum Instruction on Exclusion under Articles 1F and 33(2) of the Refugee Convention, Humanitarian Protection and the instruction on Restricted Leave.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – Start of section

The information in this section has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – End of section

2. Protection

2.1.1 Where the person has a well-founded fear of persecution from non-state actors, including ‘rogue’ state actors, decision makers must assess whether the state can provide effective protection.

2.1.2 In general, the state is willing and able to do this. The onus is on the person to demonstrate otherwise. Each case needs to be considered on its facts.

2.1.3 The Ethiopian Federal Police is responsible for maintaining law and order at federal level and for investigating crimes that fall under the jurisdiction of federal courts. The EFP also maintains law and order in any region when there is a deteriorating security situation beyond the control of the regional government, as do the military (see Ethiopian Federal Police (EFP)). The Criminal Justice Reform Working Group noted there are reports of excessive caseload among investigators that are triggered by lack of capability and capacity, namely shortage of competent investigators, poor management of caseload and lack of technology (see Capacity and effectiveness of security forces). However, in general, the police are effective in maintaining law and order and protecting the population from major crimes, including terrorism.

2.1.4 Each of the region has a special (para military) force (see Special forces (paramilitary forces). Local militias also operate across the regions in co-ordination with regional police forces or act on behalf of the ethno-linguistic communities they represent (see Local militias). State (regional) police are responsible for law and order in the regional states. However, they vary in size, structure, training and how they fulfil their role within the region they are operating in. According to Freedom House petty bribery and corruption among the police are widespread. In a national survey by the Federal Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission (FEACC) more than 60% participants thought that local police were highly corrupt.

2.1.5 Ethiopia has an extensive intelligence and security services. Although there is no reliable data on the size of the national intelligence security services, it is broadly considered to have a strong capacity and is highly effective (see National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS) and Information Network Security Agency (INSA). The Ethiopian National Defence Forces (ENDF) play a role in internal security when community security is insufficient to maintain law and order. It’s comprised of a ground force, air force, republic guard (established in 2018 to protect senior officials) and navy. The RNDF has an estimated 150,000 active personnel. The CIA World Factbook noted that the ENDF has traditionally been one of sub-Saharan Africa’s largest, most experienced, and best equipped militaries although it suffered heavy casualties and equipment losses during the 2020-2022 Tigray conflict. The government generally retains control over federal and defence security forces and their actions (see Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF)). However, the proliferation of ethnic-based militias and other armed groups has challenged state authority and eroded the rule of law in some parts of the country. Decision makers need to consider each case on its facts, with the onus on the person to demonstrate why they would not be able to obtain protection.

2.1.6 Oversight mechanisms are generally limited and rely on internal accountability systems and disciplinary policies within security forces, rather than oversight through an independent external body (see Regulation). The Ministry of Peace oversees the Federal Police and the government-funded Ethiopia Human Rights Commission (EHRC) investigated human rights abuses across the country. EHRC did not face adverse action from the government despite criticizing it for disregarding the rule of law and abusing human rights, and in some instances, federal and regional government bodies appeared to follow EHRC reports and recommendations in taking corrective measures to address human rights violations and abuses (Ethiopia Human Rights Commission (EHRC)).

2.1.7 A national survey by The Hague Institute for Innovation of Law found that approximately 80% of the people take some form of action to resolve their most serious legal problems and that around 45% of all these problems are resolved with 40% of the most serious problems are completely resolved. 43% of the people who have legal problems seek the support of village elders and 18% of the most serious problems reach a formal court which is higher than the usual 5% to 10% seen in some other countries (see Access to justice).

2.1.8 The constitution provides the legal framework for establishing a criminal justice system, providing for a national defence service, federal and state (regional) police forces, federal and regional prisons, the recognition of religious and traditional courts and an independent judiciary. The criminal code establishes a series of laws criminalising behaviour and acts that might be persecutory or cause serious harm, and outlines the available sentencing options (see Legal Context).

2.1.9 The constitution and penal code prohibit and criminalise torture and other cruel and inhuman treatment, prohibit arbitrary arrest and/or detention, and provide for detainee rights. However, the security forces sometimes engage in harassment, use of excessive force, torture, arbitrary arrest and detention, enforced disappearances, sexual and gender-based violence against women and girls, and extra-judicial killings. Many of these abuses occur particularly in areas of internal conflict, such as Tigray (during the civil conflict between November 2020 and November 2022) (see Human rights abuses).

2.1.10 The constitution provides for an independent judiciary but the government maintains significant influence over the judicial process, which is subject to political interference and reportedly affected by arbitrary decisions made by the Prime Ministers Offices especially in cases involving political opponents. However, the government took some steps to improve and bolster the independence of the judiciary such as appointing judges based on merit and experience rather than party loyalty and transferring the budgetary decisions for the judiciary from the executive to parliament (see Judicial independence).

2.1.11 The constitution provides for the right to a fair public trial and the presumption of innocence. This is however not respected in practice. Criminal courts remain weak and overburdened. Corruption within the justice system remains a significant challenge and judges caught accepting bribes are rarely punished. A weak and overburdened judicial system contributes to slow prosecutions and sometimes lengthy detentions without charge or trial, undermining the courts’ effectiveness. However, as reported by the US State Department, the courts pushed authorities to present evidence or provide clear justifications within 14 days or release the detainee and also demanded to see police investigative files to assess police requests for additional time (see Judicial independence, Arbitrary arrest).

2.1.12 Many rural citizens had little access to formal judicial systems and relied on traditional mechanisms for resolving conflict. By law, all parties to a dispute must agree to use a traditional or religious court. Sharia (Islamic law) courts heard religious and family cases involving Muslims if both parties agree and received some funding from the government. Other traditional systems of justice, such as councils of elders, functioned predominantly in rural areas. Women often believed they lacked access to fair hearings in the traditional court system because local custom excluded them from participation in councils of elders and due to persistent gender discrimination (see Religious and traditional courts).

2.1.13 There is a functioning prison system, with estimates of over 100,000 detainees. Despite some reported improvements, conditions in prisons are reportedly harsh and life-threatening in some cases, with unreliable medical care, unhygienic conditions and overcrowding. Some sources reported that there are ongoing and consisted allegations and complaints of torture and ill treatment in places of detention (see Detention conditions).

2.1.14 Various laws, including the Constitution, include the right to legal aid, which is provided by Public Defenders under the Federal and Regional Supreme Courts, the attorney general, Ministry of Women and Children Affairs, lawyers in private practice, professional law associations, non-governmental organisations and university-based law clinics. However, legal aid legislation is fragmented and provision is uncoordinated.

2.1.15 For further guidance on assessing state protection, see the Asylum Instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

Country information

About the country information

This contains publicly available or disclosable country of origin information (COI) which has been gathered, collated and analysed in line with the research methodology. It provides the evidence base for the assessment.

The structure and content of this section follow a terms of reference which sets out the general and specific topics relevant to the scope of this note.

This document is intended to be comprehensive but not exhaustive. If a particular event, person or organisation is not mentioned this does not mean that the event did or did not take place or that the person or organisation does or does not exist.

Decision makers must use relevant country information as the evidential basis for decisions.

section updated: 12 January 2024

3. Brief overview of political institutions

3.1.1 The US Central Intelligence Agency World Factbook last updated 13 December 2023 (CIA Factbook 15 August 2023) noted that Ethiopia is a federal parliamentary republic with a bicameral Parliament consisting of the House of Federation (HoF) and the House of People’s Representatives (HopR). Members of the HoF (153 seats maximum; 144 seats current) are indirectly elected by state assemblies to serve 5-year terms and members of the HoPR (547 seats maximum; 470 seats current) are directly elected in single-seat constituencies by simple majority vote. 22 seats are reserved for minorities and all members serve 5-year terms[footnote 1]. The same source further noted that the head of state is President Sahle-Work Zewde (since October 2018) and the head of government is Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed Ali (since April 2018)[footnote 2].

3.1.2 The Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation (ACCORD) report ‘Ethiopian COI Compilation November 2019, which is based on various sources, (ACCORD Report November 2019) stated:

‘According to the constitution, the highest executive powers of the federal government are vested in the prime minister and in the Council of Ministers. The powerful prime minister is head of government and is designated by the ruling party in the lower chamber, which is also responsible to nominate a candidate for the presidency… The prime minister is also Commander-in-Chief of Ethiopia’s armed forces…In April 2018, Abiy Ahmed took office as prime minister of … Ethiopia.

‘… According to the regime typology used in the Democracy Index of the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), the research and analysis division of The Economist Group, Ethiopia is governed by an “authoritarian regime”… Freedom House, a US-based NGO which conducts research and advocacy on democracy, political freedom and human rights, designates the Federal Republic of Ethiopia in 2018 as “not free”.[footnote 3]

3.1.3 The 2023 Freedom House report on political rights and civil liberties, based on events in 2022 (FH Report 2023), designated Ethiopia as ‘not free.’[footnote 4]

3.1.4 The US CIA Factbook last updated 13 December 2023 noted:

‘Ethiopia has over fifty national-level and regional-level political parties. The ruling party, the Prosperity Party, was created by Prime Minister ABIY in November 2019 from member parties of the former Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), which included the Amhara Democratic Party (ADP), Oromo Democratic Party (ODP), Southern Ethiopian People’s Democratic Movement (SEPDM), plus other EPRDF-allied parties such as the Afar National Democratic Party (ANDP), Benishangul Gumuz People’s Democratic Party (BGPDP), Gambella People’s Democratic Movement (GPDM), Somali People’s Democratic Party (SPDP), and the Harari National League (HNL).

‘Once the Prosperity Party was created, the various ethnically-based parties that comprised or were affiliated with the EPRDF were subsequently disbanded; in January 2021, the Ethiopian electoral board de-registered the Tigray People’s Liberation Front or TPLF; national level parties are qualified to register candidates in multiple regions across Ethiopia; regional parties can register candidates for both national and regional parliaments, but only in one region of Ethiopia.’[footnote 5]

3.1.5 The ACCORD Report November 2019 observed:

‘The foundation of Ethiopian federalism was established in 1995, when a new constitution became effective…

‘Articles 1 and 2 of the 1995 constitution establish the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia [FDRE], which comprises the territories of the members of the federation … Article 47 lists the nine member states of the federation, often referred to as regions or Killil (Plural: Killiloch) … Additionally there are two self-governing administrations: the Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa and the city of Dire Dawa, located in east-central of the country.’[footnote 6]

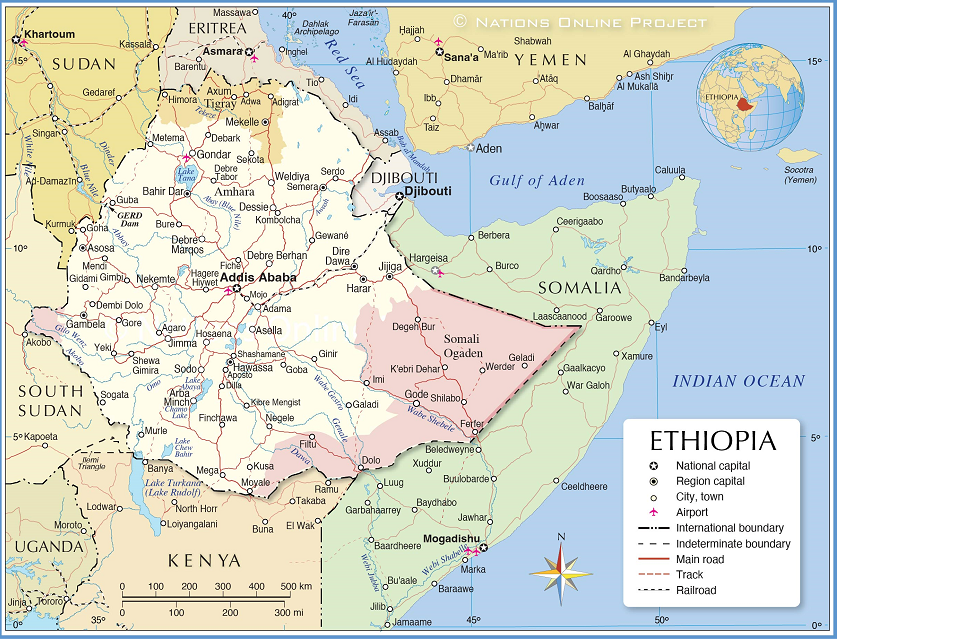

3.1.6 A detailed map A detailed map of Ethiopia’s regions (states) and zones (sub-divisions within regions) is available from the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA).

3.1.7 Nationsonline.org has provided below map of Ethiopia showing neighbouring countries, major cities and transport links[footnote 7]

section updated: 3 January 2024

4. Legal framework

4.1 The constitution and criminal code

4.1.1 The Constitution of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia was adopted on 8 December 1994 and promulgated by the Constitution of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Proclamation No. 1/1995 which entered into force on 21 August 1995. The Constitution includes the protection fundamental rights and freedoms including to life, security of person and liberty, to equality, and access to justice (chapter 3 - Fundamental rights and freedoms) and provisions on the judicial system (chapter 9 – Structure and powers of the courts)[footnote 8].

4.1.2 The Criminal Code of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia 2004 came into force on 9 May 2005 and repealed the 1957 Penal Code and the 1982 Revised Special Penal Code of the Provisional Military. Article 1 – Object and Purpose of the Code explains:

‘The purpose of the Criminal Code of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia is to ensure order, peace and the security of the State, its peoples, and inhabitants for the public good.

‘It aims at the prevention of crimes by giving due notice of the crimes and penalties prescribed by law and should this be ineffective by providing for the punishment of criminals in order to deter them from committing another crime and make them a lesson to others, or by providing for their reform and measures to prevent the commission of further crimes.’[footnote 9]

4.2 Arrest and detention

4.2.1 The US State Department report on human rights practices in Ethiopia covering events in 2022 and published on 20 March 2023 (USSD HR Report 2022) stated: ‘The constitution and federal law prohibit arbitrary arrest and detention and provide for the right of any person to challenge the lawfulness of his or her arrest or detention in court. The government often did not observe these requirements, especially regarding the mass detentions made under the state of emergency.’[footnote 10]

4.2.2 With respect to arrest procedures the second periodic report submitted by Ethiopia to the UN Committee Against Torture on 6 May 2020 (UNCAT Ethiopia Report May 2020) noted:

‘Article 19 of the FDRE Constitution entitles that every individual has a right to be informed of the reason why he/she is arrested…

‘… Article 27 of the Code obliges an arresting or investigating officer to expressly inform a detainee that he/she has the right to remain silent and that any statement he/she voluntarily gives can be brought before a court of law as evidence against him/her. Similarly, Article 31 of the same Code prohibits the police from inducing or threatening or applying any other improper method in the process of examination of witnesses …

‘Pursuant to Article 19 … arrested persons have a right to be released on bail.’[footnote 11]

4.2.3 USSD HR Report 2022 stated:

‘Under the constitution, accused persons have the right to a fair, public trial without undue delay, a presumption of innocence, legal counsel of their choice, appeal, the right not to self-incriminate, the right to present witnesses and evidence in their defense, and the right to cross-examine prosecution witnesses. The law requires officials to inform detainees of the nature of their arrest within a specific period, according to the severity of the allegation. The law requires that, if necessary, translation services be provided in a language defendants understand. The federal courts are required to hire interpreters for defendants that speak other languages and had staff working as interpreters for major local languages.’[footnote 12]

4.2.4 The same source added:

‘The constitution and law require detainees to appear in court and face charges within 48 hours of arrest or as soon thereafter as local circumstances and communications permit … With a warrant, authorities may detain persons suspected of serious offenses for 14 days without charge. The courts increasingly pushed authorities to present evidence or provide clear justifications within 14 days or release the detainee. Courts also demanded to see police investigative files to assess police requests for additional time.

‘A functioning bail system was in place. Bail was not available, however, for persons charged with murder, treason, or corruption. In other cases, the courts set bail between 500 birr ($11.60) and 100,000 birr ($1,900), [£7.01 to 1,402.34[footnote 13]] amounts that few citizens could afford. Often police failed to release detainees after a court decided to release them on bail; sometimes, police would file another charge immediately after the court’s decision.’[footnote 14]

4.2.5 The FH report 2023 noted: ‘Due process rights are generally not respected. The right to a fair trial is often not respected, particularly for government critics. In civil matters, due process is hampered by the limited capacity of the Ethiopian courts system, especially in the peripheral regions where access to government services is weak. As a result, routine matters regularly take years to be resolved.’[footnote 15]

4.2.6 A September 2023 HRW report stated: ‘Federal and regional investigative authorities have violated the due process rights of high-profile detainees, such as critical journalists or political opposition figures, by forcibly disappearing them or holding them incommunicado, denying them access to their lawyers and family members for weeks or months, or moving them between makeshift and official detention sites.’[footnote 16]

4.3 Federal Attorney General

4.3.1 A 2020 article by Dr. Girmachew Alemu Aneme, an assistant Professor and Head of the Research and Publications Unit, School of Law, Addis Ababa University, published by the Hauser Global Law School Program, New York University School of Law (Aneme 2020) stated:

‘The Federal Attorney General is part of the executive branch of the Federal Government. The Federal Attorney General has the primary authority of prosecution of cases falling under the jurisdiction of federal courts. Article 6 of Federal Attorney General Establishment Proclamation No. 943/2016 enumerates the powers and duties of the Attorney General …

‘Article 10 of the Council of Ministers Regulation 44/98 deals with the accountability of the Federal Prosecutors and according to Article 17 (2) of Federal Attorney General Establishment Proclamation No. 943/2016 stipulate that prosecutors shall be accountable to the Attorney General as well as to their immediate superior and division head. As the ultimate superior of all prosecutors, the Attorney General may thus initiate a specific criminal investigation or stop another. The Attorney General also has the authority to reverse a decision of a prosecutor or to dismiss a pending case.’[footnote 17]

4.3.2 The UNCAT Ethiopia Report May 2020 stated:

‘Prosecutors are assigned to each police station and investigation center and oversee the entire investigation process. They visit persons under custody and take legal measures if there is any violation of human rights. Further strengthening this scheme, OAG has now been legally mandated to lead, supervise, follow up and coordinate the criminal investigation function of the federal police pursuant to Definition of Powers and Duties of the Executive Organs of the FDRE Proclamation No. 1097/2018. Equivalent offices of regional states are also entrusted with similar duties and responsibilities’[footnote 18]

4.3.3 The March 2021 report which explored different aspects of Ethiopia’s criminal Justice system by March 2021 report by Criminal Justice Reform Working Group (WG), which was established by the Federal Attorney General to advise the government on the design and implementation of legal and justice sector reform[footnote 19] (CJWG Report March 2021) noted:

‘Attorney General Establishment Proclamation 943 Article 6 mandates OAG to cause a criminal investigation to be started, follow up report to be submitted on an ongoing criminal investigation, the investigation to be completed appropriately, orders discontinuation or restart of discontinued investigation based on public interest or when it is known that there could be no criminal liability, ensures that investigation is conducted in accordance with the law, and gives the necessary instruction. The essential questions to ask are whether the OAG is capable and willing to lead investigations. Whether there is an actual practice of leading investigation.’[footnote 20]

4.3.4 The same source noted several concerns about OAG’s ability and willingness to lead investigations, including power overlap between the Attorney General and the police that causes misunderstandings and conflict between the two sides, a lack of standardisation in the investigation process, a lack of coordination between the police and prosecutors that results in ineffective investigation and poor prosecution, the prosecutors’ reluctance to visit crime scenes, and a lack of specialised investigative skills.[footnote 21]

4.4 Legal aid

4.4.1 A June 2015 article on access to justice and legal Aid in Ethiopia by Abyssinia Law, an online free-access resource for Ethiopian legal information (Abyssinia Law Report June 2015) stated that ‘Access to justice is also recognized as a right in the FDRE Constitution.’[footnote 22] However, according to the same source, there are four main barriers to accessing justice: ‘lack of legal identity, ignorance of legal rights, unavailability of legal services, and unjust and unaccountable legal institutions.’ [footnote 23] The source also noted that unavailability, or expense, of obtaining legal representation or other forms of legal assistance presented a serious barrier to accessing to justice for the poor. Hence, various laws, including the constitution, include the right to legal aid[footnote 24].

4.4.2 The same source noted that lawyers licensed to practice law in the federal courts are required by law to render a minimum of fifty hours legal service a year free of charge or upon minimal payment to persons who cannot afford to pay and to persons for whom a court requests legal service. The Ethiopian Bar Association (EBA) and Alumni Association of Law Faculty of Addis Ababa University provided legal aid services in the premises of the Federal High Court/Federal First Instance Court and the EBA legal aid centre in Addis Ababa while regional associations such as Biruh (Diredawa), Tesfa (Hwassa), and Selam (Harrar) provided legal aid services in their respective towns. Additionally, NGOs including the Children’s Legal Protection Center (CLPC), the Ethiopian Women Lawyers Association (EWLA), Action of Professionals Association for the People (APAP) and Association for Nation-wide Action and Protection against Child Abuse and Neglect (ANPPCAN) provided legal services through voluntary or paid staff and paralegals[footnote 25].

4.4.3 An undated entry on the Federal Supreme Court website stated: ‘Those accused of a crime have the right to a representation during their trial to ensure a fair trial. The Public Defenders’ Office …organized under the Federal Supreme Court is mandated to provide free legal representation & services to indigent persons, who can’t afford to have representation as per the order of the bench/court.’[footnote 26]

4.4.4 The Foreign, Commonwealth & Development office information pack for British nationals arrested or imprisoned in Ethiopia, last updated 30 August 2022, stated:

‘Article 20 (5) of the Ethiopian Constitution recognises the rights of an accused person to be represented by a “legal counsel of their choice, and, if they do not have sufficient means to pay and a miscarriage of justice would result, to be provided with legal representation at state expense”. However, in reality the government will assign defense counsel only for serious cases which entail capital punishment. The Charities and Societies Proclamation prevents Civil Society Organisations from providing free legal aid services.’[footnote 27]

4.4.5 An August 2023 UNHCR legal aid factsheet on Ethiopia noted: ‘UNHCR Ethiopia, in collaboration with the Universities of Bule Hora, Dilla, Wollega, Dembi Dollo, Assosa, Arba-Minch, and Wollo, and Danish Refugee Council (DRC) provide free legal aid and legal awareness services to forcibly displaced persons and members of the host community to promote the rule of law through fairer, more consistent, and transparent delivery of legal justice to women, the poor, and vulnerable populations.’[footnote 28]

4.4.6 The USSD HR Report 2022 noted:

‘… The government provided public defenders for detainees unable to afford private legal counsel, but defendants received these services only when their cases went to trial and not during the pretrial phases. In some cases, a single defense counsel represented multiple defendants in a single case …

‘The federal Public Defender’s Office provided legal counsel to indigent defendants, but the scope and quality of service reportedly were inadequate due to attorney shortages. A public defender often handled more than 100 cases and might represent multiple defendants in the same criminal case. Numerous free legal-aid clinics, primarily based at universities, also provided legal services. In certain areas of the country, the law allows volunteers such as law students and professors to represent clients in court on a pro bono basis. There reportedly was a lack of a strong and inclusive local bar association or other standardized criminal defense representation.’[footnote 29]

section updated: 12 January 2024

5. Prison and detention system

5.1 Overview

5.1.1 A June 2021 report of the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC report June 2021) noted: ‘The prison system in Ethiopia is organized in one federal prison system and 10 regional prisons systems. The Aleltu Training Centre trains prison officers for both federal and regional prisons.[footnote 30]

5.1.2 Aneme 2020 stated:

‘The Federal Prisons Commission is established by Proclamation No.365/2003 as an institution and according to “Federal Prisons Commission Establishment (Amendment) Proclamation No. 945/2016 accountable to the Attorney General. The objectives of the Commission are to admit and ward prisoners, provide them with reformative and rehabilitative services in order to enable them to make attitudinal and behavioral changes, and to help them become law abiding, peaceful and productive citizens. The Federal Prisons Commission has powers and functions akin to most prison facilities.’[footnote 31]

5.1.3 The same source added: ‘States are allowed to establish their own Police and Prison Commissions. The Police and Prison Commissions of the states are accountable to the State Justice Bureaus. Even though the State Police and Prison Commissions are functionally independent, they are obliged to cooperate with their federal counterparts in order to maintain improved conditions of prisons across the nation.’[footnote 32]

5.1.4 The World Prison Brief, hosted at the Institute for Crime & Justice Policy Research (ICPR) at Birkbeck, University of London, is a database that provides free access to information about prison systems throughout the world using data largely derived from governmental or other official sources.[footnote 33] According to the source, the Ministry of federal affairs is responsible for prisons and the prison administration consist of the federal prison Commission and 9 State prison Administrations. The source noted that as of 2015, there were 126 prisons - 6 federal and 120 regional – in Ethiopia and as of March 2020 the prison population including pre-trial and remand prisoners was 110,000.[footnote 34] UNODC report 2021) stated that: ‘There are approximately between 100,000 and 120,000 inmates in Ethiopia, with approximately 4,800 (4%) female inmates.’ According to the same source ‘Approximately 40,000 inmates were released as part of the government’s large-scale pardons in 2020 to prevent the transmission of COVID-19 in places of detention.’[footnote 35]

5.1.5 The same source indicated a consistent reduction in the proportion of pre-trial /remand prison population from 56.6% in 1999/200 to 14.0% in the year 2009/2010 before rising slightly to 14.9% in the year 2011/2012[footnote 36].. The source, noted that the pretrial/remand prisons ‘consists of the number of pre-trial/remand prisoners in the prison population on a single date in the year (or the annual average) and the percentage of the total prison population that pre-trial/remand prisoners constituted on that day[footnote 37]. CPIT could not find current prison figures from the sources consulted (see Bibliography)

5.2 Training

5.2.1 UNODC report June 2021 noted that in December 2020 ‘30 prison personnel from the Prison Training Centre trained to deliver trainings to prison staff on international standards in prison management, including on Nelson Mandela Rules and Bangkok Rules.’[footnote 38] The Nelson Mandela Rules refer to the United nations Standard Minimum Treatment of prisoners (for further information see Nelson Mandela Rules).

5.2.2 UNODC’s semi-annual progress report 1 January-30 June 2021 noted:

‘The Ethiopian Federal Prison Commission launched a national prison-training curriculum at the annual consultation forum of Federal and Regional Prison Commissions organized by the Federal Prison Commission. The curriculum, developed with UNODC support, targets all prison wardens and prison officials in Ethiopia. The curriculum has included certification in the online training on the Nelson Mandela Rules, part of the education process thereby institutionalizing human rights, rehabilitation and security related best practices, setting an example for other countries in the region.

‘… The curriculum focuses on human rights, security and rehabilitations and is informed by lessons learned from the targeted trainings conducted for Ethiopian.’[footnote 39]

5.3 Detention conditions

5.3.1 The UNCAT Ethiopia Report May 2020 noted:

‘Ethiopia recognizes that the conditions of detention centers and prison facilities lag behind and require significant improvements to meet international standards. Accordingly, challenges such as overcrowding, inadequate or obsolete infrastructure, lack of sanitary conditions, disease, malnutrition and violence between prisoners remain to be addressed and require relentless effort towards their significant improvement. The Government is committed to resolve these shortcomings and is working assiduously through the allocation of additional resources and capacity building.’ [footnote 40]

5.3.2 However, the same source noted government efforts to improve prison conditions. It stated:

‘Extensive measures have been taken in Ethiopia to improve the conditions of detention centres and prisons. Among the measures taken include improvement of basic services with in police custody centres and prisons. Accordingly, the daily budget for food and drink for a single prisoner at the federal prison administration has doubled. A decision has been reached in May 2019 to further increase the daily budget allotment. The OAG is also working with development partners to improve conditions of detention in all police stations in Addis Ababa including reduction of congestion, improved water supply, better sleeping facilities and other basic amenities.

‘The Federal Prison Commission and regional state prison administrations are building new prison facilities and upgrading existing ones to enhance compliance with international human rights standards. For instance, the Federal Government is building 4 new prison facilities to ensure prisoners are kept in conditions that respect their human dignity. The facilities under construction, inter alia, include modern cells, administrative blocks, academic and vocational schools and are also fitted with ramps and disability friendly latrines. [footnote 41]

5.3.3 The UNODC report June 2021 noted that: ‘Despite progress, further improvements are needed in the treatment of prisoners in prisons including in the provision of basic services (rehabilitation support, health, education, food).’[footnote 42]

5.3.4 The Committee Against Torture Concluding observations on the second periodic report of Ethiopia adopted on 10 May 2023 (UNCAT Report May 2023):

‘While acknowledging the steps taken by the State party to improve conditions in places of detention … the Committee remains concerned at reports indicating overcrowding in some prisons … and poor material conditions of detention … in particular insalubrity and inadequate hygiene, lack of ventilation, the poor quality and insufficient quantity of the food and water provided and limited recreational or educational activities to foster rehabilitation. Furthermore, the limited access to quality health care rehabilitation. Furthermore, the limited access to quality health care, including mental health care, in particular for pregnant women and women held in detention with their children and the lack of trained and qualified prison staff, including medical staff, remain serious problems in the prison system. The Committee is also concerned at reports indicating the prevalence of violence in prisons, including violence perpetrated by prison staff against detainees and inter-prisoner violence and sexual abuse, and the practice of detaining pretrial detainees with convicted prisoners and children with adults.’[footnote 43]

5.3.5 The same source added:

‘In view of the numerous, ongoing and consistent allegations and complaints of torture and ill-treatment by police officers, prison guards and other members of the security forces, as well as the military, in police stations, detention centres, federal prisons, military bases and in unofficial or secret places of detention, particularly during the investigation stage of proceedings, the Committee remains deeply concerned at the lack of accountability, which contributes to an environment of impunity …’[footnote 44]

5.3.6 The Ethiopian Human Rights Commission (EHRC) report covering June 2022 to June 2023 which is based on a review of 126 police stations and 49 detention facilities (EHCR Report August 2023) noted:

‘The Commission has visited 49 detention/correction facilities and 346 police stations during the reporting period.

‘There are marked improvements in acknowledging and implementing the Commission’s recommendations. Some of the positive developments include most prisons having slightly increased the budget for food supply taking into account current market prices; improvement in prison health facilities; increase in the number of detention cells and in some cases construction of new facilities to reduce overcrowding; and notable improvements in terms of visitation rights - access to family and friends, and legal and religion counsel.

‘There are, however, several issues of concern that are yet to be addressed by the relevant authorities in some of the detention facilities. For instance, lack of appropriate or digitized register of detainees in some prisons, absence of special care and support for prisoners with communicable diseases, insufficient or absence of adequate support for infants and children … inadequate supply of sanitary products … and failure to keep juvenile detainees separate from adult prisoners.

‘Lack of a standardized pardoning system, and lack of special care for the vulnerable including persons with disabilities, older persons, pregnant women, and nursing mothers are also among issues that need to be improved. The inadequacy of water supply and healthcare compared to the size of the prison population, and over-crowdedness of sleeping areas in many of these facilities also need to be addressed.’[footnote 45]

5.3.7 The same source added:

‘Notable improvements and changes have also been recorded in police stations monitored in the last year. In Addis Ababa for instance, some police stations installed CCTV cameras to monitor the treatment of persons in their custody. Other positive steps include: police departments have set up/established onsite healthcare facilities; separate detention quarters for child detainees; efforts to transfer children in conflict with the law who are between the ages of 9 and 15 to rehabilitation centers for juveniles; improved hygiene in some police stations; taking administrative and legal measures against police officers who have committed human rights violations; and improvements such as at Kolfe Keraniyo, Arat Kilo and Lideta police detention centers after relocating to newly constructed buildings.

However, problems such as inadequate provision of food, water and health services; beatings and torture to compel confession; lack of a standardized procedure to execute arrests including informing the suspect of the charges and the reason for the arrest; and lack of formal internal complaints procedures persist in most of the police stations monitored.

‘Other issues requiring urgent attention include prolonged pre-trial detention in police stations; failure to execute bail order by courts; failure to provide separate quarters/compounds for women detainees, overcrowding; and in some cases, serious unsanitary conditions.’[footnote 46]

section updated: 12 January 2024

6. The judiciary

6.1 Structure

6.1.1 The entry by Assefa Fiseha in the Oxford Constitutional law on relations between the legislature and the Judiciary in Ethiopia noted that 79(1) of the constitution stipulates that ‘Judicial powers are vested in the courts.’[footnote 47] The same source added:

‘[A]ccording to articles 62 and 83 of the constitution, the HoF is mandated to interpret the constitution and resolve constitutional disputes … [T]he HoF has no law-making functions. The HoF is a quasi-political body composed of, to use the words of the constitution, ‘nations, nationalities and people’. Each group has at least one representative but each ‘nation or nationality shall be represented by one additional representative for each one million of its population. As for the selection/election process article 61(3) of the constitution envisages two possibilities. Members of the HoF may be elected indirectly by the state legislature or the state legislature may decide the members to be elected directly by the people. So far experience indicates that all members are indirectly elected by the states.’ [footnote 48]

6.1.2 Aneme 2020 noted:

‘Ethiopia has a dual judicial system with two parallel court structures. In addition to these courts, the FDRE Constitution allows the establishment of Religious and Customary courts. The federal courts and the state courts with their own independent structures and administrations. Judicial powers, both at Federal and State levels, are vested in the courts. The FDRE Constitution states that supreme federal judicial authority is vested in the Federal Supreme Court and empowers the [House of Peoples’ Representatives] HPR … to establish subordinate federal courts, as it deems necessary, nationwide or in some parts of the country. There is a Federal Supreme Court that sits in Addis Ababa with national jurisdiction and until recently, the Federal High Court and First Instance Courts were confined to the federal cities of Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa. In recent years, Federal High Courts have been established in five States. Federal courts at any level may hold circuit hearings at any place within the State or “area designated for its jurisdiction” if deemed “necessary for the efficient rendering of justice.” Each court has a civil, criminal, and labor division with a presiding judge and two other judges in each division.’[footnote 49]

6.1.3 The CJWG Report March 2021 observed:

‘… [T]he… Constitutions established a dual court structure: federal and State Courts. At the federal level, the constitution creates a federal supreme court vested with a supreme federal judicial authority and mandates the … HPR by two thirds majority vote, to establish the Federal High Court and First Instance Court it deems necessary, either national [sic] wide or in some parts of the country. Absent such establishment, the constitution further states, the jurisdictions of the Federal High Court and First-Instance Court are delegated to states’ supreme courts and high courts respectively …

‘The House of peoples representatives… has established Federal High court and First –Instance courts in Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa … Federal High Courts in the regional states of Afar, Benshangul, Gambella, Somalia and Southern Nations Nationalities and Peoples …. The regional states also created their own Supreme, High (Zonal) and Wereda Courts by means of their respective states constitutions …

‘The FDRE constitution entitles regional states to establish Supreme Court, High courts and First Instance Courts in their respective regions. The Supreme Courts of regional states are seated in the capital city of the regions, the High Court’s (Zonal courts) in cities of the Zones and Wereda (first instance courts) in each Wereda of the region …’[footnote 50]

6.1.4 With respect to the administration of the judiciary, Aneme 2020 stated:

‘The FDRE Constitution provides that the President and Vice-President of the Federal Supreme Court shall be appointed by the House of Peoples’ Representatives upon the recommendation of the Prime Minister; other federal judges are appointed by the HPR from a list of candidates selected by the Federal Judicial Administration Commission.

‘The FDRE Constitution prohibits the removal of judges before retirement age except for violation of disciplinary rules, gross incompetence or inefficiency, or illness that prevents the judge from carrying out his responsibilities. Such determinations are made by the Federal Judicial Administration Commission, which likewise decide issues of appointment, promotions, disciplinary complaints, and other conditions of employment.

‘… The day-to-day operations of the Federal Courts in Ethiopia are supervised and managed by court presidents, who therefore act both as judges and administrators with responsibilities and obligations towards the President of the Supreme Court.’[footnote 51]

6.2 Judicial independence

6.2.1 The 2022 report by Bertelsmann Stiftung Transformation Index (BTI) project, a collaboration of nearly 300 country and regional experts from leading universities and think tanks that analyses and compares transformation processes towards democracy and inclusive market economy worldwide,[footnote 52] covering the period 2019 to 2021 (BTI Report February 2022) commented:

‘…[T]he judiciary is far from independent and heavily affected by arbitrary decisions made by the Prime Minister’s Office. The legal system is to some extent institutionally differentiated, but severely restricted by functional deficits, insufficient territorial operability, scarce resources and nowadays by political interferences. Judicial appointments have been made on the basis of loyalty to the government to ensure that judicial decisions are consistent with government policy, even when that means contravening the rule of law and the constitution. Judges not loyal to the government run the risk of being replaced by a “more suitable” candidate.’[footnote 53]

6.2.2 FH Report 2022 noted:

‘The judiciary is officially independent, but in practice it is subject to political interference, and judgments rarely deviate from government policy. Ethiopia’s security forces have maintained significant influence over the judicial process, especially in cases against opposition leaders and other political adversaries. Judges who attempt to exercise independence have faced arrests by authorities. Courts remain complicit in ensuring impunity for security forces, especially in relation to the political prisoners.’[footnote 54]

6.2.3 The 2023 Africa Integrity Indicators, a research project initiated by Global Integrity, whose aim is to support locally-led efforts to solve governance-related challenges in collaboration with the Mo Ibrahim Foundation focusing on African governance in practice[footnote 55] (Global Integrity 2022) noted:

‘In the Ethiopian Constitution of 1995, Article 78 states the separation of government branches and the independence of the judiciary. Judges can interpret laws, although legislation is still a power vested in parliament. Regardless of the separation of powers, the judiciary in Ethiopia still has to deal with interference by politicians trying to influence judges.

‘Several reform attempts over the years have failed to tackle the issue of the politicization of the judiciary and weak legislation. However, this is not a problem specific to the judiciary but rather a widespread issue in public institutions in the country.

‘Under the new government, the Ethiopian judiciary, led by Supreme Court president Meaza Ashenafi, has tried to bring about change. An important step was an amendment to the Federal Judges Code of Conduct and Disciplinary Procedure Regulation, with the aim of improving transparency in the system and requiring accountability from federal judges.

‘During the research period, the judiciary also has worked on securing financial independence (by dealing with parliament directly for funds), a key step in ensuring the branch is not dependent on other bodies of government.

‘Although these promising steps do not signify total independence for the judiciary they indicate a strong willingness to reform the sector and detach judicial institutions from their usual image of nondependent and unreliable institutions.’[footnote 56]

6.2.4 The February 2023 report ‘Ethiopia: Overview of corruption and anti-corruption efforts’ by Matthew Jenkins, a Research and Knowledge Manager at Transparency International and S M Elsayed published by the Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI) U4 Helpdesk, which works to reduce the harmful impact of corruption on society[footnote 57], February 2023 report on corruption in Ethiopia (Jenkins and Elsayed 2023) noted:

‘Since coming to power, Abiy’s administration has taken some steps to improve the system of judicial appointments by nominating judges based on merit and experience rather than party loyalty. In 2020, two proclamations were approved by parliament that were intended to bolster the independence and accountability of the judiciary, and a code of conduct for judges and new performance standards have been developed to operationalise these proclamations … In his recent speech to parliament, Abiy also noted that budgetary decisions related to the judiciary have recently been transferred from the executive to the legislative branch.

‘However, the continued lack of security of tenure for judges renders it difficult for them to rule against the government; analysts argue that in recent years the judiciary has been used by the state to prevent opposition figures from contesting elections. Moreover, while there have been some signs of progress at the federal level, the picture is less encouraging at the regional level where judges have apparently been beaten and detained by the police and local officials for not making favourable decisions.’[footnote 58]

6.2.5 The Committee against Torture Concluding observations on the second periodic report of Ethiopia adopted on 10 May 2023 (UNCAT Report May 2023) stated:

‘While noting the measures taken to strengthen the independence of the judiciary, such as the adoption of Proclamation No. 1233/2021 on the federal judicial administration and Proclamation No. 1234/2021 on federal courts, the Committee remains concerned about reports regarding the lack of independence of the judiciary vis-à-vis the executive branch and its susceptibility to political pressure, which may contribute to impunity, including for cases of torture. That concern is compounded by shortcomings in the justice system, such as a shortage of resources, including a dearth of judges and lawyers and a lack of basic training for them, delays in processing cases and a failure to enforce some court decisions.’[footnote 59]

6.2.6 The International Commission of Human Rights Experts on Ethiopia (ICHREE) report on the situation of human rights in Ethiopia (UNGA Report September 2023) stated:

‘…The independence of the judiciary is guaranteed by the Federal Constitution, but constitutional interpretation favors political decision makers over courts, both regional and federal. Courts are widely believed to lack independence and to be subject to regular political interference.

‘In 2021 legislation placed the Office of the Attorney-General under the Ministry of Justice, including the power to initiate and discontinue investigations, and appoint, administer and dismiss public prosecutors, undermining prosecutorial independence and impartiality. Prosecutors could face increased pressure from political actors in their choices of investigations, prosecutions and trials. There is the risk for further centralization of power in the federal Ministry of Justice in proposals in the draft Justice Sector Reform Policy Document (September 2023), seen by the Commission.’[footnote 60]

6.2.7 A September 2023 HRW report observed:

‘… Concerns also remain over the influence that Ethiopia’s federal and regional authorities have over judicial processes, where investigative authorities have routinely appealed or ignored court decisions in cases involving critics of the government or opposition figures.

‘There have also been cases where investigations and judicial decisions have been subject to political interference, compromising the ability of domestic bodies to act with impartiality and independence. For example, in October 2022 police detained three Supreme Court judges in the Oromia region after they granted bail to six security personnel of the opposition political party leader.’[footnote 61]

6.3 Corruption in the judicial system

6.3.1 Jenkins and Elsayed 2023 stated:

‘Corruption is certainly a topic that is recognised by the country’s political leadership as being endemic. ‘Judicial corruption has been explicitly targeted by Prime Minister Abiy…

‘While the interference of the Prime Minister’s Office in the judiciary is viewed by some analysts as part of the problem this has not prevented Abiy from strongly criticising corruption in the judiciary in a speech to parliament in November 2022. Abiy listed a lengthy set of corruption problems in the judicial system, including prosecutors accepting bribes in exchange for intentionally losing or dropping cases, abuse of power on the part of court clerks overseeing case management resulting in evidence “disappearing” and a general lack of transparency and ethical standards. In a recent interview with The Reporter, Mesfin Erkabe, a member of the parliamentary legal, justice, and democracy affairs standing committee from Abiy’s ruling Prosperity Party also pointed to the reportedly widespread practice of “trading justice for money” …[footnote 62]

6.3.2 According to the same source, a Federal Ethics and Ant-Corruption Commission [FEACC] corruption perceptions survey found that ‘57% of the 4,018 citizens questioned expressed the view that the judicial system was not fair, although 89% of those that came into contact with the judiciary indicated that they had not been asked to pay a bribe to a judge, prosecutor or other court official.’[footnote 63]

6.3.3 The FH Report March 2023 also noted that ‘…Corruption within the justice system remains a significant challenge, and judges caught accepting bribes are rarely punished.’[footnote 64]

6.3.4 The BTI Report 2022 noted that although Abiy pledged to fight corruption, so far, it is fair to assume that the political core of the federal executive maintains control over the judiciary when it comes to cases of political importance[footnote 65].

section updated: 3 January 2024

7. Security forces

7.1 Law and structures

7.1.1 The Constitution of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia under Articles 51 and 52, provides for the powers and functions of government: ‘It shall establish and administer national defence and public security forces as well as a federal police force’ and ‘[t]o establish and administer a state police force, and to maintain public order and peace within the State.’[footnote 66]

The Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s (DFAT) Country Information Report Ethiopia, ‘informed by DFAT’s on-the-ground knowledge and discussions with a range of sources in Ethiopia [and]… takes into account relevant and credible open source reports’, dated 17 August 2020 (DFAT report 2020), based on information prior to the conflicts in Tigray and Amhara in 2020 to 2023[footnote 67],noted:

‘Ethiopia has an extensive security and intelligence apparatus, a legacy of its previous political systems. The state exercises control over most of the country, and it has largely been effective in maintaining law and order and protecting the population from major crimes, including terrorism. The security and intelligence apparatus was used in the past to monitor and suppress dissent, and had a history of using force to quell instances of unrest, including large-scale anti-government protests.’[footnote 68]

7.1.2 USSD HR Report 2022 noted:

‘National and regional police forces are responsible for law enforcement and maintenance of order, with the Ethiopian National Defense Force sometimes providing internal security support. The Ethiopian Federal Police report to the Prime Minister’s Office. The Ethiopian National Defense Force reports to the Ministry of Defense. The regional governments control regional security forces, which generally operate independently from the federal government and in some cases operate as regional defense forces maintaining national borders. Civilian authorities maintained effective control over the security forces. There were reports that members of the security forces committed numerous serious abuses.’[footnote 69]

7.1.3 The US CIA Factbook updated on 13 December 2023 observed:

‘… national and regional police forces are responsible for law enforcement and maintenance of order, with the [Ethiopian National Defence Force] ENDF sometimes providing internal security support; the Ethiopian Federal Police (EFP) report to the Prime Minister’s Office… the regional governments control regional security forces, including “special” paramilitary forces, which generally operate independently from the federal government and in some cases operate as regional defense forces maintaining national borders; local militias also operate across the country in loose and varying coordination with these regional security and police forces, the ENDF, and the EFP; in April 2023, the federal government ordered the integration of these regional special forces into the EFP or ENDF… in 2018 Ethiopia established a Republican Guard military unit responsible to the Prime Minister for protecting senior officials’.[footnote 70]

7.1.4 An April 2022 report by the Netherlands Institute of International Relations (Clingendael), an independent think tank and academy on international affairs (Clingedael Report April 2022) observed:

‘… the [Abiy]… administration has seemingly sought to centralise previously dispersed powers into a single institution. In the early stage of the transition, the internal security portfolio was placed under the powerful Ministry of Peace, the successor of the Ministry of Federal Affairs… the new ministry was granted supervising powers over Ethiopia’s main intelligence agencies, the [National Intelligence and Security Service] NISS and the [Information Network Security Agency] INSA, which had previously been directly supervised by the PM’s office. The Ministry also took the lead in the sensitive efforts to regulate the functioning of the various special forces and militias operating in Ethiopia’s regions. In the wake of the 2021 general elections, however, the new administration has moved both intelligence agencies back under the PM’s direct oversight, together with the Federal Police Commission …’[footnote 71]

7.2 Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF)

7.2.1 According to the US CIA Factbook last updated 13 December 2023, ENDF is comprised of ground forces, Ethiopian Air Force, a Republican Guard (established in 2018 to protect senior officials) and a navy (re-established in 2020). The same source while noting that information about Ethiopia’s military personnel varies it stated that prior to the 2020-2022 Tigray conflict it had approximately 150,000 active-duty troops which included about 3,000 Air Force personnel with no figures available for the re-established Navy. The source also estimated Ethiopia’s military expenditure in 2023 at 1.7% of GDP compared to 0.8% in 2018.[footnote 72]

7.2.2 Similarly the 2024 US based Global Firepower Index (GFP), which measures and ranks military power based on each nation’s potential war-making capability fought by conventional means[footnote 73], estimated that Ethiopia had 162,000 active military personnel comprising of 5,000 air force, 75,000 army and 10,000 navy[footnote 74].

7.2.3 The ENDF played a role in internal security. The March 2020 USSD human rights report covering events in 2019 (USSD HR Report 2019) stated: ‘When community security was insufficient to maintain law and order, the military played an expanded role with respect to internal security; in particular, setting up military command posts in parts of the country like West and South Oromia, as well as Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples’ (SNNP) Region.’[footnote 75] According to multiple sources ENDF was, at the time of writing, active in Tigray, Benshangul/Gumuz, Oromia, the Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples’ Region (SNNPR), and Amhara regions[footnote 76] [footnote 77] [footnote 78].

7.3 National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS)

7.3.1 The September 2016 report by Clingendael (Netherlands Institute of International Relations), a think tank and diplomatic academy on international affairs[footnote 79] noted that: ‘The Ethiopian National Intelligence and Security Service was established in 1995 and currently enjoys ministerial status, reporting directly to the Prime Minister. It is tasked with gathering information necessary to protect national security. Its surveillance capacities have been used both to prevent terrorist attacks, such as those by Al-Shabaab, and to suppress domestic dissent.’[footnote 80]

7.3.2 A January 2020 report by the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA), a UK Department for International Development (DfID) funded centre that focuses on decision-making that facilitates the use of ICT in support of good governance, human rights and livelihoods[footnote 81] (CIPESA Report January 2020) noted with respect to NISS:

‘In 2013, the government re-established the National Intelligence and Security Services (NISS) with a ministerial status and as an autonomous body of the federal government. This institution has broad intelligence and security mandate and power to investigate threats “against the national economic growth and development activities” and to gather intelligence on serious crimes and terrorist activities. It is responsible for many of the human rights violations that happened in the country before 2017 including mass and illegal surveillance of citizens both online and offline, censorship of dissenting voices, torture, and intimidation of dissenting voices online and offline.’[footnote 82]

7.3.3 ACCORD Report November 2019 observed: ‘According to Proclamation No. 1097/2018 the “Ministry of Peace shall have powers and duties to […] oversee and follow up national intelligence and security, as well as information network and financial security functions”. The National Information Security Service (NISS) is accountable to the Ministry of Peace.’[footnote 83]

7.3.4 The USSD terrorism report covering events in 2017 stated that: ‘… The National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS), which has broad authority for intelligence, border security, and criminal investigation, is responsible for overall counterterrorism management in coordination with the ENDF and EFP.’[footnote 84] The USSD terrorism report covering 2019 noted: ‘… The National Intelligence and Security Service continued to reorganize and reform to focus on collecting intelligence to detect and disrupt terrorism in support of EFP and attorney general efforts to conduct law enforcement investigations and prosecutions.’[footnote 85] According to the USSD terrorism report covering events in 2021 ‘Al-Shabaab and ISIS terrorist threats emanating from Somalia remain a high priority for the National Intelligence and Security Service.’[footnote 86]

7.4 Information Network Security Agency (INSA)

7.4.1 Citing sources, the Accord Report 2019 noted that the Information Network Security Agency (INSA), was established to safeguard the country’s information and to defend the country from cyber-attacks, that it is accountable to the Ministry of Peace and PM Abiy Ahmed is its founder [footnote 87].

7.4.2 The CIPESA Report January 2020 noted:

‘In 2006, the Ethiopian government established the Information Network Security Agency (INSA) and set up the country’s first cyber intelligence unit. The Agency was re-established in 2013 … with the objective of ensuring “that information and computer based key infrastructures are secured, so as to be enablers of national peace, democratization and development programs.” Under Article 12 of the Proclamation, every concerned body has an obligation to cooperate with the Agency in exercising its powers and duties pursuant to the Proclamation.’[footnote 88]

7.4.3 The FH Freedom of the Internet Report November 2019 stated:

‘The Information Network Security Agency (INSA), a government agency that has de facto authority over the internet with a mandate to protect the communications infrastructure and prevent cybercrime, has been placed under a new Ministry of Peace created by Abiy’s administration.

‘… In a positive step, Prime Minister Abiy—who is regarded as one of the founders of INSA—forced the resignations of agency officials who were accused of monitoring and hacking activists, leading to some optimism that INSA may become less abusive regarding its surveillance powers.’[footnote 89]

7.4.4 DFAT Report 2020 noted that ‘The federal government operates a separate cyber-intelligence and security organisation, the Information Network Security Agency (INSA). INSA’s role includes investigating threats to national security, combatting cyber-crime and preventing cyber-attacks on critical infrastructure.’[footnote 90]

7.5 Ethiopian Federal Police (EFP)

7.5.1 Aneme 2020 stated: ‘The Federal Police Commission is established by the Federal Police Commission Proclamation No.720/2011. The Commission is accountable to the Ministry of Federal Affairs (now the Ministry of Federal & Pastoralist Development Affairs).’[footnote 91] The same source noted that Article 6 of Proclamation No.720/2011 defines powers and functions which include the prevention and detection of crime, combatting and investigating crime, the maintenance of public order, enforcement of the law, and providing protection to citizens[footnote 92].

7.5.2 The US Department of State’s Overseas Security Advisory Council (OSAC), a public-private partnership between the U.S. Department of State’s Diplomatic Security Service (DSS) and security professionals from U.S. organizations operating abroad, which share timely security information and maintain strong bonds for the protection of U.S. interests overseas[footnote 93], noted in its October 2022 report:

‘The Ethiopian Federal Police (EFP) are responsible for investigating crimes that fall under the jurisdiction of federal courts, including any activities in violation of the Constitution that may endanger the Constitutional order, public order, hooliganism, terrorism, trafficking in persons, or transferring of drugs. The EFP also maintains law and order in any region when there is a deteriorating security situation beyond the control of the regional government and a request for intervention is made, or when disputes arise between two or more regional governments and the situation becomes dangerous for the security of the federal government. The EFP safeguards the security of borders, airports, railway lines/terminals, mining areas, and other vital institutions of the federal government. The EFP delegates powers, when necessary, to regional police commissions…’[footnote 94]

7.5.3 The DFAT report 2020 noted:

‘The Ethiopian Federal Police Force reports to the Ministry of Peace and is subject to parliamentary oversight. It is responsible for preventing and investigating crimes that fall under the jurisdiction of the Federal Court, including terrorism, drug trafficking and human trafficking …

‘The Federal Police Force is responsible for coordinating regional police commissions and setting national policing standards, and it provides training and operational support to regional police forces.’[footnote 95]

7.5.4 The October 2021 report by the European Institute of Peace, an independent body that partners with European states and the European Union to develop strategic and practical approaches to conflict prevention, resolution, dialogue, and mediation,[footnote 96] (EIP Report 2021) stated: ‘Since 1991, the Ethiopian police have, in principle, been subject to civilian control … At present, the police at the federal level are accountable to the Ministry of Peace (MoP), established in 2018 … The Ministers, in turn, are accountable to the House of Peoples’ Representatives and the Prime Minister.’[footnote 97]

7.6 Regional police forces

7.6.1 The DFAT report 2020 noted: ‘… all regional states have their own regional police forces. These are responsible for law and order at the state level and report to their respective state governments. Regional police forces are dominated by the ethnic group that is the majority in the state for which the force is responsible. One local source told DFAT that regional police forces often show favouritism to the ethnic community from which they are predominantly drawn.’[footnote 98]

7.6.2 OSAC Report October 2022 noted: ‘Regional police forces handle local crime under their jurisdiction and provide officers for traffic control and immediate response to criminal incidents.’[footnote 99]

7.6.3 The EIP report 2021 noted:

‘The proclamations establishing the federal police (720/2011) define the relationship between the Federal Police Commission and the Regional Police Commissions. In principle, the relevant laws reinforce the dual structure of the police, in which the federal police administer and discharge federal mandates and regional states enforce regional state laws. The respective laws also allow the delegation of federal mandates to regional state police, such as investigating federal criminal cases. Otherwise, the regional special police operate autonomously when it discharges its regional state mandate.’[footnote 100]

7.6.4 The USSD HR Report 2021 stated: ‘The regional governments control regional security forces, which generally operate independently from the federal government.’[footnote 101]

7.7 Regional ‘special’ forces

7.7.1 A July 2019 article by Professor Ann M. Fitz-Gerald, an Associate Fellow at the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), a UK independent think tank engaged in defence and security research[footnote 102] (Fitz-Gerald July 2019) stated:

‘The Liyu Haile (Amharic for “special force”) is a force of well-trained professional soldiers, many of whom, according to author interviews with regional and federal officials, have defected from the national defence force and are attracted by a number of incentives including, certainly for some regions, higher pay …

‘Little is known outside Ethiopia about the exact numbers, structure, funding, command arrangements and roles of these special forces. Yet they are certainly extensive and media sources confirm that all regions have them. Numbers range from thousands to tens of thousands, depending on the region. Whereas some have existed for longer than others, and access to weapon stockpiles and equipment differs between regions, the development of others has only unfolded in recent years.’[footnote 103]

7.7.2 The EIP Report 2021 noted with respect to the special police force:

‘… In the last fifteen years … Ethiopia’s regional states have established regional special police forces, in addition to the regular regional state police. Established first in Ethiopia’s Somali region in 2007 to conduct counter-insurgency operations and riot control, special police quickly spread to all other regions of Ethiopia.

‘The role and status of special police forces in Ethiopia remain contested. Resembling paramilitary forces, the regional special police units are well armed and receive military training. They are rapidly growing in size and have successfully recruited senior (former) army officers into their ranks. Special police forces have become deeply involved in Ethiopia’s interregional conflicts and border disputes, most notably in the current conflict in Tigray. They have … been involved in…coup attempts. They have also been linked to severe human rights abuses.’[footnote 104]

7.7.3 On 12 April 2023 The Guardian reported that ‘some states have…built powerful security services resembling small armies that sometimes clash.’[footnote 105]

7.7.4 With respect to the organisation of the special force, the EIP report 2021 stated:

‘The organisational structure of the special police varies from state to state. In the Somali regional state, especially under the administration of Abdi Iley, the Liyu police were directly accountable to the regional president. In other regional states such as Amhara, Oromia, and the South, the Liyu police are organised under the police commissions but with special links established directly with the regional state president. The police commissioner has several deputies: one of them is directly in charge of the special police. In turn, the police commissioners are accountable to the “Administrative and security affairs bureau,” which is accountable to the regional state president. In theory, the regional state executive body is accountable to the regional state’s elected legislative councils. Nevertheless … The special police remain in most cases directly accountable to the regional state president. The legislature has little knowledge and control over the special police.’[footnote 106]

7.7.5 For further information on special forces including origin, size, training and recruitment see EIP, ‘The special police in Ethiopia’, 2021.

7.8 Local militias

7.8.1 The USSD HR Report 2018 listed local militias as one of the several actors of law enforcement in Ethiopia. It noted:

‘Local militias operated across the country in loose and varying coordination with these regional police, the Federal Police, and the military. In some cases militias functioned as extensions of the ruling party. Local militias are members of a community who handle standard security matters within their communities, primarily in rural areas. Local government authorities provided select militia members with very basic training. Militia members serve as a bridge between the community and local police by providing information and enforcing rules.’[footnote 107]