DLUHC appraisal guide

Published 31 March 2023

Applies to England

Foreword

In 2016 the Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG) published the first edition of its Appraisal Guide. The aim was to ensure that Ministers and other decision makers have robust evidence on value for money when making policy and investment decisions.

That Guide has been widely used within the Department, which is now the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC), other government departments and at local level, to inform spending decisions on housing, commercial property and land use and funding decisions by local authorities.

However, two changes have occurred recently which mean it is necessary to update and develop the Appraisal Guide so that it continues to provide relevant, robust and trusted advice:

- In November 2020 HMT published a revised Green Book. This emphasised the importance of considering all objectives and impacts (including non-monetised impacts) and making fuller use of place based analysis in VfM assessments;

- The Levelling Up White Paper published in February 2022 places much greater focus on reducing geographical disparities, identifying six key capitals as fundamental to determining area performance, and twelve key missions which will support development of those capitals in left behind areas to deliver levelling up.

This updated Appraisal Guide responds to both these developments, providing additional advice on how to rigorously assess VfM and a greater focus on spatial and distributional impacts including wider regeneration of areas.

I am therefore very pleased to recommend the use of this Guide as a means of helping to deliver better evidenced-based policy making. The Guide is a living document and I look forward to future improvements that should make it even more helpful.

I would like to thank every analyst and economist in the Department (including those from Homes England) who have contributed to it, with a particular thanks to Andrew Charlesworth-May who has led the delivery of this important update. I would also like to thank Michael Spackman, Professor Peter Tyler and Professor Henry Overman who have provided invaluable comments to support its improvement.

Stephen Aldridge

Director for Analysis and Data

Department for Levelling Up Housing and Communities

List of abbreviations

AH: Affordable Housing

AONB: Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty

AST: Appraisal Summary Table

BAU: Business as Usual

BCR: Benefit Cost Ratio

BRE: Building Research Establishment

CORE: Continuous Recording of Lettings and Sales in England (DLUHC survey)

GCMA: Greater Manchester Combined Authority

GHG: Greenhouse Gas

GVA: Gross Value Added

HE: Homes England

LVU: Land Value Uplift

MV: Market value

NAO: National Audit Office

NPSV: Net present social value

OB: Optimism bias

PDL: Previously Developed Land

PRP: Private Registered Providers

PRS: Private Rented Sector

PVB: Present Value of Benefits

PVC: Present Value of Costs

PWF: Preferred Way Forward

SR: Spending Review

SRS: Social Rented Sector

TA: Temporary Accommodation

VfM: Value for Money

VOA: Valuation Office Agency

DLUHC appraisal group

The DLUHC appraisal group is responsible for overseeing the development of appraisal guidance in DLUHC and ensuring it is communicated and applied effectively within DLUHC and across partner organisations. The group covers all areas of appraisal relevant to DLUHC and Homes England.

- Stephen Aldridge, Chief Analyst at DLUHC

- Stephen Meredith, Deputy Director, Housing and Planning Analysis and Chair of Appraisal Group

- Andrew Charlesworth-May, Lead Co-ordinator and Analyst for Appraisal Guide

- Andrew Wallis, Chief Economist, Homes England

- Jo Brotherhood, Head of Economics, Homes England

- Ben Toogood, Deputy Director, Local Policy Analysis

- Zebedee Nartey, Deputy Director, Local Growth Analysis

- Catherine Barham, Deputy Director, Vulnerable People, Data and Evaluation

- Paul Vickers, Deputy Director, Safer and Greener Buildings Analysis

- Emily McGovern, Head of Homelessness and Rough Sleeping Data and Statistics

- Amy Sippitt, Head of Elections Research and Analysis

- Frank Brocek, Senior Economist, Union Devolution Research and Analysis

- Thomas Annable, Senior Economist, Safer and Greener Buildings Analysis

- David Craine, Senior Economist, Safer and Greener Buildings Analysis

- Chloe Maycock, Senior Economist, Local Growth Analysis

- Stephen Smith, Senior Economist, Local Policy Analysis

- Gemma Weston, Senior Economist, Housing and Planning Analysis

- Robert Mills, Senior Economist, Housing and Planning Analysis

- Lan-Ho Man, Principal Research Officer, Vulnerable People, Data and Evaluation

1. Introduction

The role of economic appraisal

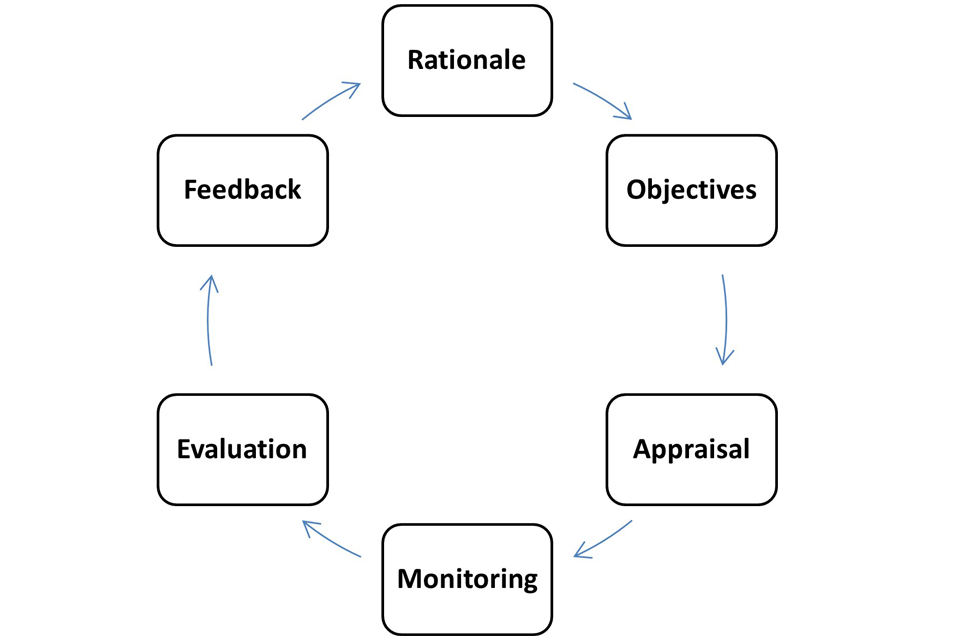

1.1 Appraisal is an essential part of the policy making process, represented by HM Treasury’s Green Book ROAMEF framework in the figure below. It is about finding the best way to meet policy objectives.

Figure 1: ROAMEF model

The six components are Rationale, Objectives, Appraisal, Monitoring, Evaluation and Feedback.

1.2 Appraisal is a two step process, conducted through longlisting then shortlisting analysis, following HM Treasury’s Five Case Business Case model[footnote 1].

1.3 DLUHC uses the Green Book for its appraisal. This guide sets out specific appraisal issues that arise in DLUHC policy areas and is focused on the economic dimension of the business case, providing specific guidance on the quantification of impacts in the economic dimension. The appraisal approaches set out are also applicable to the assessment of options in Impact Assessments.

1.4 Effective economic appraisal involves estimating costs and benefits in a consistent manner so they can be compared, particularly at the shortlist stage. Good appraisal will take account of uncertainties and risks and build them into the assessment. It will also assess which demographic groups and places are likely to be impacted by options and support the development of the Equalities Impact Assessment.

1.5 Once a policy has been chosen and implemented its impact is monitored and its performance evaluated. This provides feedback which can be used to improve the policy further or to make decisions about whether the policy should be expanded or discontinued. Note that Monitoring and Evaluation are not the subject of this guidance; further details on Monitoring and Evaluation can be found in DLUHC’s recently published Evaluation Strategy and in the Magenta Book.

Objectives of this guidance

1.6 This Appraisal Guide is intended to be read in conjunction with the Green Book and aims to:

- Help ensure consistency in DLUHC appraisals; and

- Update and develop the methods and assumptions employed in DLUHC appraisals.

The content and use of this guidance

1.7 The Guide sets out default assumptions, the theoretical framework and the metrics to be adopted by analysts in DLUHC, its agencies and local authorities when carrying out or scrutinising an appraisal.

1.8 The Guide is a technical document designed for analysts at DLUHC, its agencies and local authorities but may in some contexts be of use to analysts in other departments or sectors. The focus is on all policy areas covered by DLUHC. These include policies to level up across the country, support housing and commercial development, reduce rough sleeping and homelessness and support the work of local authorities.

1.9 It builds on the key principles and application of appraisal methodology set out in HM Treasury’s Green Book, providing in depth appraisal tools for the policy areas covered by DLUHC and its partners, for example, commercial and residential development or levelling up policies. As such it can be seen as a bolt on to the Green Book. The guidance is consistent with other departmental guidance, in particular it should be noted that it is consistent with the Department for Transport’s (DfT) recommended approach to appraising dependent development which is set out in unit A2.2 of its Transport Analysis Guidance (TAG).

1.10 The assumptions set out in the Appraisal Guide are provided as defaults when carrying out appraisal for policy development and advice, business cases and impact assessments. Users are free to adopt different assumptions and metrics where they have better evidence to hand. However, the rationale for doing so must be evidence based and clearly documented in the relevant business case (or impact assessment if a regulatory change is being considered).

Development of this guidance

1.11 The Appraisal Guide is overseen by an Appraisal Group (members of which are listed at the beginning of this Guide). The following version of the Guide is the second edition and it updates the first edition published in 2016 in a number of ways, including in response to changes following the Green Book Review and the publication of the Levelling Up White Paper in February 2022. The key changes include:

- Bringing out the importance of concentrating not just on Benefit Cost Ratios (BCRs) but on all impacts (monetised and non-monetised) when assessing Value for Money (VfM);

- Providing improved guidance on assessing the additionality of interventions so that their net impacts can be better measured;

- Supporting levelling up by making better use of place based analysis where the focus of interventions is local or regional or some other level of sub-national impacts;

- Supporting levelling up by introducing assessment of the wider impacts of housing interventions on regenerating areas; and

- Supporting levelling up by emphasising the importance of assessing distributional impacts so that it is clearer who is gaining and losing from different interventions.

1.12 This Guide is a ‘living’ document and will be updated from time to time, as new evidence and methodologies develop. We would welcome feedback or suggestions for improvement on any aspect of this guidance so we can enhance the quality of our appraisals. Please send these to AppraisalGuidance@levellingup.gov.uk.

Structure

1.13 The Appraisal Guide is structured as follows:

Chapter 2 outlines the business case model and the role that appraisal plays within it.

Chapter 3 sets out what appraisal information is needed and how it should be presented for all policies.

Chapter 4 sets out the methodology and theoretical basis for appraising and valuing development, both residential and non-residential.

Chapter 5 discusses place based appraisal within the context of the Levelling Up White Paper and includes an illustrative example of how to report place based results.

Chapter 6 documents the key assumptions that should be the default in DLUHC appraisals.

Chapter 7 sets out useful sources of information.

Annexes A to I contain further information on important topics covered in the main document.

2. The business case model

Introduction

2.1 The Five Case Business Case Model is the required framework for considering the use of public resources. This chapter:

- Introduces the Five Case Business Case Model and the role that appraisal plays within it;

- Sets out some key issues that appraisals of DLUHC interventions need to be aware of including: ensuring there is a clear rationale for intervention; that options selection follows the Green Book long-listing and short-listing approach; that options are assessed against a clearly defined counterfactual and that additionality is allowed for when appraising the impact of options.

2.2 If you are producing or reviewing a business case, in addition to reading the Green Book, you must read and familiarise yourself with the relevant programme or project business case guidance. All those involved in appraisal, and in development of business cases, and in their review and approval must be trained and accredited. Details of the appropriate HM Treasury approved training and accreditation scheme are given on the Green Book Training page.

2.3 The five “cases” or dimensions are different ways of viewing the same proposal. In brief the:

a. Strategic Dimension – sets out the case for change, including the rationale for intervention and SMART objectives;

b. Economic Dimension – sets out the net value to society of the intervention compared to continuing with Business As Usual (defined as the continuation of current arrangements, as if the proposal under consideration were not to be implemented);

c. Financial Dimension – looks at the impact of the proposal on the public sector budget;

d. Commercial Dimension – assesses whether a realistic and credible commercial deal can be struck and who will manage which risks; and

e. Management Dimension – sets out the approach to delivery, assesses key risks and presents the benefits realisation plan.

The role of appraisal in the strategic and economic dimensions

2.4 Appraisal plays a particularly important role in the strategic and economic dimensions. This is discussed fully in the HMT Green Book, however in summary:

- The strategic dimension sets out the case for change and the rationale for intervention. It asks the questions: What is the current situation? What is to be done? What outcomes are expected? How do these fit with wider government policies and objectives? These require a strategic assessment supported by sound appraisal based on robust but proportionate analysis. The elements of the strategic assessment which are supported by appraisal activity are set out in Box 6 below taken from the Green Book.[footnote 2], [footnote 3]

Box 6 of HMT Green Book, Page 20: Logical Change Process

The Strategic dimension of the Business Case requires a Strategic Assessment key steps in which are:

- A quantitative understanding of the current situation known as Business As Usual (BAU)

- Identification of SMART objectives that embody the objective of the proposal

- Identification of the changes that need to be made to the organisation’s business to bridge the gap from BAU to attainment of the SMART objectives. These are known as the business needs.

- An explanation of the logical change process i.e. the chain of cause and effect whereby meeting the business needs will bring about the SMART objectives.

- This all needs to be supported by reference to appropriate objective evidence in support of the data and assumptions used including the change mechanisms involved. It should include:

- the source of the evidence;

- explanation of the robustness of the evidence; and

- of the relevance of the evidence to the context in which it is being used.

- This provides a clear testable proposal that can be the subject of constructive challenge and review. Single point estimates at this stage would be misleading and inaccurate and objectively based confidence ranges should be used.

The economic dimension is the analytical heart of a business case where detailed option development and selection through use of appraisal takes place. It is driven by the SMART objectives and delivery of the business needs that are identified in the strategic dimension. It estimates the social value of different options at both the UK level and, where necessary on different parts of the UK or on groups of people within the UK. Longlist appraisal and selection of the shortlist is a crucial function of the economic dimension. The selection of the preferred option from the shortlist uses social cost benefit analysis or where appropriate social cost effectiveness analysis[footnote 4]. When assessing options, those which do not meet key strategic objectives cannot represent Value for Money.

2.5 It is important to ensure that there are clear links between the strategic and economic dimensions and other dimensions too.

-

The commercial dimension concerns the commercial strategy and arrangements relating to services and assets that are required by the proposal and to the design of the procurement tender where one is required. The procurement specification comes from the strategic and economic dimensions. The commercial dimension feeds information on costs, risk management and timing back into the economic and financial dimensions as a procurement process proceeds.

-

The financial dimension is concerned with the net cost to the public sector of the adoption of a proposal, taking into account all financial costs and benefits that result. It covers affordability, whereas the economic dimension assesses whether the proposal delivers the best social value. It is exclusively concerned with the financial impact on the public sector. It is calculated according to National Accounts rules.

-

The management dimension is concerned with planning the practical arrangements for implementation. It demonstrates that a preferred option can be delivered successfully. It is important in supporting the development of metrics and targets.

These links mean that analysts will need to work across dimensions - and with other professions - if appraisal is to be done effectively and decisions made using robust information.

The rationale for intervention

2.6 As noted above, the strategic dimension sets out the rationale for intervention. This defines the purpose of the intervention. The Green Book defines a number of potential purposes including:

- Maintaining service continuity, arising from the need to replace some factor in the existing delivery process;

- Improving the efficiency of service provision;

- Increasing the quantity or improving the quality of a service;

- Providing a new service;

- Complying with regulatory changes; or

- A mix of all the above.

2.7 The Green Book highlights that a key rationale for government intervention may be to improve the welfare efficiency of existing private sector markets. For example, intervening to ensure provision of a service or investment which would not occur because wider social benefits are ignored by firms. This represents an example of market failure.

2.8 In economic theory, when economic efficiency is achieved nobody can be made better off without someone else being made worse off. Economic efficiency enhances social welfare by ensuring resources are allocated and used in the most productive manner possible.

2.9 Improving equity may also be another reason for intervention as social welfare might be increased if resources are redistributed from those with a lower marginal utility of income to those with a higher marginal utility. An example of this is given in Annex H of this document.

2.10 If there is no market failure or equity justification, government intervention compared to market provision may be welfare reducing. Although this would not be the case if the intervention is correcting an existing ‘government failure’ that itself has resulted in an inefficient allocation of resources.[footnote 5]

2.11 Based on the rationale, specific intervention objectives will be defined. These will be used to assess options alongside the four other business case lenses – value for money, commercial viability, affordability and deliverability – to arrive at a preferred option.

Appraisal of options

2.12 Appraisal is about finding the best way to meet policy objectives. This is a key theme of the Green Book.

2.13 Policy objectives are set out in the strategic dimension. They must be SMART. The economic dimension then uses the longlist approach in the Green Book to create an initial shortlist for comparison through cost benefit analysis, or social cost effectiveness analysis.

Longlist appraisal

2.14 Longlist appraisal allows a wide range of alternatives for meeting SMART Objectives to be considered so that a short list can be identified for more detailed Cost Benefit Analysis.

2.15 Options are generated using the Options Framework Filter which identifies options across five separate aspects set out in the Green Book (see table below). These are then assessed against critical success factors using SWOT analysis.

Option choices – broad description

- Scope - coverage of the service to be delivered

- Solution - how this may be done

- Delivery - who is best placed to do this

- Implementation - when and in what form can it be implemented

- Funding - what this will cost and how it shall be paid for

2.16 “Critical Success Factors” are the attributes that any successful proposal must have, if it is to achieve successful delivery of its objectives. These include Strategic Fit, meeting SMART objectives, potential value for money, supplier capacity and capability, potential affordability and achievability. More detail on the five basic critical success factors that apply to all proposals is given in Box 9 of the HMT Green Book.

2.17 When identifying and considering options, constraints, dependencies, collateral or unintended effects and equality, distributional and placemaking effects should be examined.

2.18 The result of the longlisting will be a short list of five or six options. The short-listed options should include a:

- Quantified BAU for use as a benchmark counterfactual;

- Do minimum option (that just meets the business needs required by the SMART objectives);

- Preferred Way Forward (that may or may not be the Do Minimum);

- A more ambitious preferred way forward (this may be more expensive, deliver more value, but at higher costs with increased risks); and

- A less ambitious preferred way forward, unless the preferred option is a do minimum (this option may take longer, deliver less value but cost less and / or carry less risk).

2.19 The process of identifying and assessing options is a complex task and must be carried out by an expert.

2.20 Chapter 4 of the Green Book and its links provides comprehensive guidance on long listing and choosing the short list together with examples. It should be consulted for further detail on how to go about long listing before starting the process.

Shortlist options appraisal

2.21 At short list stage a much narrower range of options are being considered. This allows more detailed analysis to be carried out and in particular the application of Cost Benefit Analysis. This compares the social benefits that options yield to the costs of the option (both are measured relative to the counterfactual).

2.22 The specific methods used to appraise costs and benefits for DLUHC policies are set out in Chapter 3 and following chapters. More context on shortlist options appraisal is provided in Chapter 5 of the Green Book.

Options and the counterfactual

2.23 Individual options will need to be assessed against an appropriate baseline or counterfactual. This should be the business as usual and be a clear articulation of how things will evolve in the absence of the alternative option being considered. The costs and benefits of that alternative option should always be compared relative to the counterfactual. Clearly defining the counterfactual allows analysts to understand how far individual policy options change impacts and desired objectives rather than being deadweight – that is, what would have happened anyway. It is important because there is no additional economic benefit from government providing support for an outcome which would have happened anyway (though, there may be if the outcome happens quicker, is of a better quality than it otherwise would be or it redistributes outcomes to different places, e.g. in need of levelling up).

2.24 Once a credible counterfactual has been established, this should be compared against each of the other options. For each option this involves understanding what outcomes can be expected with the policy in place over the lifetime of the intervention.

2.25 The degree to which a market failure is present can provide some insight into the expected additionality of an intervention. A common example is the existence of externalities which impose costs (or benefits) on third parties. For example, the existence of a brownfield site which cannot be developed due to the presence of contaminated land, but which once developed could provide an amenity benefit to society and improved environmental outcomes. In this case, one might expect the deadweight of an intervention to unlock the site’s development to be zero, as the land would not have been developed in the absence of the intervention. Information failures, such as consumers not knowing the standard to which buildings are built, represent another type of market failure.

Assessing the impact of an option against the counterfactual

Example 1

A policy is expected to result in the provision of 1,000 housing units. Only 400 of these units are expected to be delivered in the business as usual. Then:

Net impact of the policy = 1,000 units – 400 units = 600 units

The 600 units are additional, whilst the 400 units are referred to as deadweight.

Example 2

A policy is expected to result in the provision of 1,000 housing units. However 1,000 of these units will also be delivered in the business as usual.

If 1,000 units are expected to be delivered in the business as usual, there are no additional benefits, unless the units are delivered faster or are of a higher quality with government intervention.

Net impact of the policy = 1,000 units – 1,000 units = 0 units

In this example there is zero additionality and 100% deadweight.

2.26 Given the importance of market failure in determining the level of additionality, analysts should ensure that the rationale for public sector intervention is clear and is supported by solid evidence. A more detailed discussion of additionality is set out in Annex D whilst the full list of market failures is set out in Annex F.

3. Assessing the Value for Money (VfM) of DLUHC interventions

Introduction

3.1 This chapter outlines what measures of Value of Money (VfM) should be calculated in a DLUHC appraisal and how this appraisal information should be presented. The chapter begins with different measures and how they are constructed and presented before looking in more detail at components of the underlying calculations and discussing some important economic issues.

3.2 An important point to make at the outset is that as the 2020 Green Book Review says ‘the appraisal process is not a decision making algorithm and its objective is to support decision-making…’. The assessment should move beyond a narrow focus on Benefit Cost Ratios (BCRs) which, though important, do not reflect all the impacts interventions may have on the strategic objectives that decision makers are trying to achieve. There are likely to be a number of impacts which cannot be monetised and so cannot be included in a BCR. The use of VfM categories (discussed below), which allow decisions to incorporate non-monetised impacts alongside the BCR, enables a fuller assessment of interventions to be made.

3.3 All impacts included in the VfM assessment (monetised and non-monetised) should be grounded in solid evidence and based on a robust theory of change, linking inputs and activities to outcomes. It is important that all relevant impacts identified by the theory of change are considered in the VfM assessment and adequate allowance is made for additionality when making the assessment. Failure to do this will result in incorrect conclusions being drawn.

DLUHC appraisal summary table (AST)

3.4 An appraisal should provide clear and transparent advice to decision makers on different policy options, taking account of costs, benefits, risks, uncertainties and significant non-monetised impacts. The objective of appraisal should be to provide a consistent comparison of benefits and costs. Presenting such information in summary form is crucial if complex technical information is to be communicated effectively (see below).

3.5 The table below is a recommended Appraisal Summary Table (AST) which should be used for all spending proposals. It should feature in business cases and in all documents where appraisal information is contained. The AST aims to capture all the important appraisal information including on benefits and costs, risks and an overall VfM assessment for each of the options. It presents information on the Benefit Cost Ratio (BCR) and Net Present Social Value (NPSV)[footnote 6] alongside other impacts that cannot be monetised although they are part of the overall VfM judgement.

3.6 Table 1 sets out the main elements in an AST and these are discussed below. This is based on the summary AST set out in Chapter 7 of the HMT Green Book. The AST includes five short-list policy options which are the minimum recommended at Short Listing Stage (see paragraph 4.40 of the Green Book). An example of how to complete an AST for a hypothetical scenario is given in Annex A.

Benefits

3.7 The DLUHC AST includes two lines for benefits, each of which are converted into present value measures. The first row reports those benefits which have been assessed using “tried and trusted” methods. The second row reports benefits estimated using “evolving” methods:

-

’Tried and trusted’ refers to benefits which are estimated using methods judged by relevant departmental supplementary guidance as being robust. See a list of this supplementary guidance.[footnote 7] Examples include estimates of land value uplift using the method in this guidance, transport user benefits using the DfT TAG approach, air quality, greenhouse gases, the values of life and reducing crime;

-

’Evolving’ methods refer to approaches which are judged by relevant departmental supplementary guidance as being relatively less established and potentially subject to higher levels of uncertainty.

- Examples include wider area benefits in regeneration areas (see Annex Gi), economic productivity impacts from increased density and output changes under imperfect competition (see DfT TAG Unit A2.1), amenity impacts (see Annex Giii), and labour supply impacts (see chapter 5)

- Evolving evidence may include additional estimates of impacts based on users’ own evidence (i.e. evidence not currently incorporated in Green Book Supplementary and Departmental guidance). These estimates may be based on more tentative assumptions where the evidence base is not so well established. However, where such estimates are used assumptions will need to be set out and justification provided for their use and acceptance.

- Distributional impacts relating to income (see Annex H) are also included in this category.

Table 1: Recommended DLUHC appraisal summary table

| Option 1 Business As Usual (baseline) | Option 2 Do Minimum | Option 3 Preferred Way Forward | Option 4 More Ambitious PWF | Option 5 Less Ambitious PWF | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Present Value Benefits[footnote 8] [tried and trusted methods] (£m)][footnote 9] | |||||

| B | Present Value of Other Monetised Benefits [evolving methods] (£m) | |||||

| C | Present Value Public Sector Costs (£m) | |||||

| D | Net present social value (£m) [A-C] or [A+B-C] | |||||

| E | ‘Initial’ Benefit-Cost Ratio [A / C] | |||||

| F | ‘Adjusted’ Benefit Cost Ratio [(A + B) / C] | |||||

| G | Significant non-monetised (quantifiable impacts) | |||||

| H | Significant non-monetised (non-quantifiable impacts) | |||||

| I | Value for Money (VfM) Category | |||||

| J | Switching values & rationale for VfM category[footnote 10] | |||||

| K | DLUHC Financial Cost, £m | |||||

| L | Residual risk & optimism bias allowances | |||||

| M | Life span of project | |||||

| N | Other Issues |

3.8 All monetised benefits based on evolving methods should feature in row B of the AST (‘Present Value of other monetised impacts’) and not in row A. These impacts - because they are still evolving - should be treated more cautiously than those which go into row A. These impacts will be part of the ‘adjusted’ BCR calculation but along with non-monetised impacts inform the overall value for money category (see below).

3.9 In some cases, for example increases in carbon emissions or blight, benefits may be negative, in which case they are called disbenefits and are netted off other benefits.

3.10 Some interventions will have significant non-monetised benefits or disbenefits. To prevent these impacts being overlooked it is important they are documented and their likely significance assessed using the evidence available. The final VfM assessment should take these impacts into account (see non-monetised impacts section).[footnote 11] Impacts are less likely to be monetised early on in business case development where a wider range of options are being assessed at a higher level. However non-monetised impacts can still be significant at full business case stage.

Costs

3.11 For DLUHC spending proposals, the relevant measure is net costs to the public sector. This means all exchequer costs – for example, changes in Universal Credit (including Housing Benefit) as well as any local authority costs and revenues – should be accounted for when estimating net public sector costs. If costs are related to a transfer – like Universal Credit or a government grant – an identical and offsetting value should feature in the benefits figure unless it is already reflected in a different variable such as land value uplift. For appraisal purposes net public sector costs are converted into present value terms and labelled the present value of costs (PVC).

Net present social value (NPSV) and the benefit cost ratio (BCR)

3.12 Two summary welfare measures are presented in the Appraisal Summary Table:

a) Net Present Social Value

The NPSV of a project is defined as the present value of benefits (PVB) less the present value of costs (PVC).[footnote 12],[footnote 13] This measures the overall level of public welfare generated by a policy and so is an important measure of impact:

NPSV = PVB – PVC

b) Benefit Cost Ratio

The BCR of a project is represented as:

BCR = PVB / PVC

3.13 The BCR can be interpreted as the estimated level of benefit per £1 of cost. It is used as the core element in the measure of VfM when interventions involve a net cost to the public sector. The reason for its use is that public sector budgets are fixed through the Spending Review process and so not all interventions with a potentially positive NPSV can be chosen.[footnote 14] The BCR allows different proposals to be ranked alongside each other on the basis of benefit per £1 of public sector spend to maximise the social impact of the budget. (Non-monetised impacts also need to be taken into account using switching values – see section on Estimating VfM)

3.14 Where the PVC is negative then the NPSV represents a better measure of impact.[footnote 15] In the case where PVC is negative the VfM of the intervention is often very high, although this might not be the case where reductions in costs come with reductions in benefits. The approach to measuring VfM for the special case of negative spend is set out in Annex I.

3.15 The BCR is used in the vast majority of projects covering DLUHC and local government as in most cases PVC>0.

3.16 When estimating the BCR, it is important that there is transparency in what is included in the benefits and costs. This means being clear about the robustness of the underlying evidence base and the appraisal values being used. It also means being clear when more subjective values are included in the appraisal (this is discussed further below).

3.17 To account for the evolving nature of the methods used for estimating impacts, it is recommended the BCR is separated into two components which are each reported: an ‘initial’ BCR and an ‘adjusted’ BCR.

-

The ‘initial’ BCR takes into account all appraisal values where there is a strong underlying evidence base and which are based on Green Book and Green Book Supplementary and Departmental guidance. That is, it is based on ‘tried and trusted’ methods;

-

The ‘adjusted’ BCR includes estimates based on ‘evolving’ techniques or where there is a high degree of uncertainty in the results produced by those techniques.

-

The types of impacts which are classed as ‘tried and tested’ or ‘evolving’ are set out in the section on Benefits.

3.18 The ‘adjusted‘ BCR - along with non-monetised impacts - should inform the overall Value for Money category of the policy.

3.19 In calculating a BCR it is important to account properly for different types of funding streams including income receipts. The table below shows which are counted as benefits and which as costs. A square bracket means the value is subtracted.

| Consumer and business impacts | External impacts and public sector finance impacts | |

|---|---|---|

| Present Value Benefits (numerator) | Private benefits for example land value uplift [Private sector costs if not captured in land value][footnote 16] Public sector grant or loan if not captured in land value[footnote 17] [Public sector loan repayments if not captured in land value] Distributional benefits |

External benefits [External costs] |

| Present Value of Costs (denominator) | Public sector grant or loan [Public sector loan repayments] Other public sector costs [Other public sector revenues] |

3.20 Once a BCR is calculated, it is important users assess its plausibility. For example, if the estimated BCR is high and consists mainly of private impacts, then it is important to consider why such a project would not have happened in the absence of the intervention. This will mean ensuring there is a sound market failure underpinning the rationale for intervention as set out in the strategic dimension. Where there is no market failure, this may mean there is significant deadweight (see Additionality section) and therefore users should re-visit the underlying additionality assumptions.

3.21 It should be noted that all the impacts in this calculation should be risk adjusted. In the early stages of policy development this will primarily be through Optimism Bias (OB) adjustments to both costs and benefits. Further guidance on OB is given in the Optimism bias section and in the Green Book. A specific example of how OB might be assessed in housing is set out in Annex E.

Hypothetical examples of how to calculate the NPSV, initial and adjusted BCR

3.22 The examples below set out the calculations for three hypothetical policies to illustrate how the NPSVs and BCRs of DLUHC policies would be calculated. For simplicity, assume all figures have been discounted to the appropriate year, are all in real prices and OB has already been applied to both costs and benefits.

Example 1: A DLUHC grant to support a development

One policy option being considered is a £5m grant to support a development on a brownfield site. The rationale for intervention is the external benefits that may be generated by intervening e.g. improved amenity benefits for existing residents of the area.* These external benefits are estimated to be around £5m.

However, the development is unlikely to take place in the absence of the intervention because of the high upfront costs of ‘cleaning up’ the land. These high upfront costs are estimated to be £5m and their existence makes the development commercially unviable. As such the Gross Development Value does not cover the development costs and provide a minimum level of profit. Assume that once the land is ‘cleaned up’ the value of the land in its new use is £5m. Also assume for simplicity that the value of land in its current use is zero and there are no wider external impacts or monetised impacts associated with the intervention other than the improved amenity impacts for existing residents of the area. Also assume for simplicity that there is no displacement of other economic activity.

In this example the ‘initial’ BCR of intervening would be calculated as follows: The present value of benefits is the land value in its new use (£5m) minus the value of the land in its previous use (£0m). The estimated cost is the £5m grant to clean up and develop the land. The NPSV would be PVB-PVC = £5m-£5m= £0m and the ‘initial’ BCR = PVB/PVC = £5m/£5m = 1. However, the other quantified impacts from improved amenity and health are estimated to be around £5m. By including these impacts in the appraisal, the estimated benefits become £10m and the estimated costs are £5m. This means the NPSV becomes £10m-£5m = £5m and the ‘adjusted’ BCR is £10m/£5m=2.0.

*Note that changes in amenity values for new residents following the development will be reflected in the price they pay for property and so will be reflected in the Land Value Uplift. Annex G discusses the difference between private impacts – which are reflected in the Land Value Uplift – and external impacts.

Example 2: A DLUHC loan to support brownfield land clean-up and development

DLUHC is approached for a loan to support the redevelopment of a brownfield site. The rationale for intervention is that there is evidence of market failure in the lending market which is restricting firms access to finance. The development is expected to provide an external amenity and health benefit.

The site is suitable for 1,000 houses but the high upfront ‘clean-up’ costs and difficulties in accessing financing make the development commercially unviable. The land value in its new use is £85m based on a financing arrangement which enables the firm to borrow £100m and repay £50m over the appraisal period from sale of the developed site. Once developed, there are potential net external benefits of £10m. Assume for simplicity the value of the site in its current use is £10m.

For the purposes of this example, assume there is no deadweight or displacement from intervening. In this case, by DLUHC providing a loan of £100m and receiving £50m back over the appraisal period from the firm, the present value benefits would be equal to the land value in its new use (£85m) less the value of the land its current use (£10m). The present value costs would be the initial loan of £100m less expected repayments of £50m from the firm (that is £50m net exchequer costs). In this example, the NPSV would therefore be £25m (£75m economic benefits less £50m economic costs to the exchequer). The ‘initial’ BCR would therefore be 1.5 (£75m economic benefits divided by £50m economic costs to the exchequer).

When including the potential external benefits of £10m, the present value benefits increase to £85m while the economic costs remain at £50m. The NPSV would therefore be £35m and the ‘adjusted’ BCR would be equal to 1.7.

Example 3: DLUHC will invest £20m to increase the number of polling stations to make voting more accessible to the public

This will help reduce the barriers to voting by making it more accessible for people to vote, especially for those who do not have access to cars, or those who may find it challenging to access public transport. This is expected to increase the turnout of people coming to vote at UK elections and improve the democracy of UK elections. Some novel analysis has been conducted to look at the potential monetised benefit of an increase in elector turnout, and this is expected to yield an economic benefit of £5m (based on time-to-vote analysis).

In this example, the initial Net Present Social Value will be -£20m as there are no monetisable benefits associated with this policy. However, if we include the estimated impact of the additional increase in elector turnout in the ‘adjusted’ NPSV, would reduce to -£15m.

The ‘initial’ BCR will be 0 as the approach taken to estimating benefits is novel, however the ‘adjusted’ BCR will be 0.25 (£5m in economic benefits divided by £20m of costs). Furthermore, this case will need to consider the non-monetisable benefits when assessing value for money.

Non-monetised impacts

3.23 BCR and NPSV measures only capture monetised impacts. When performing options analysis there are likely to be a number of impacts which are difficult to quantify and monetise. This might reflect the nature of the impact as some environmental impacts are more difficult to monetise. Alternatively it might be because the analysis is at an early stage, before modelling can be developed and applied.

3.24 It is essential that where monetisation is not possible, a qualitative assessment of the potential impacts is carried out and considered alongside BCR or NPSV measures when arriving at an assessment of overall VfM.

3.25 Users will need to form an assessment of the likely magnitude and direction of impact of non-monetisable impacts. The following seven-point scale could be used to make an assessment:

Table 2: Qualitative assessment scale for non-monetised impacts

| Impact | Commentary |

|---|---|

| Large Adverse | Large disbenefit likely to materially impact on VfM |

| Moderate Adverse | Important disbenefit but will not on its own significantly impact on VfM |

| Slight Adverse | Small disbenefit unlikely to have material impact on VfM |

| Neutral | No impact |

| Slight beneficial | Small benefit unlikely to have material impact on VfM |

| Moderate Beneficial | Important benefit but will not on its own significantly impact on VfM |

| Large Beneficial | Large benefit likely to materially impact on VfM |

3.26 The advantage of using the seven-point scale is that it allows a set of criteria to be applied to assess size and direction of an impact, providing increased transparency when reaching conclusions.

3.27 Large beneficial or large adverse impacts should be given special attention when assessing the VfM of a project. Similarly, if there are several moderate beneficial or moderate adverse impacts these should also be considered in the VfM assessment. This is discussed in more detail in the Estimating VfM section.

3.28 Looking at non-monetised metrics such as output data - for example, number of trees ‘lost’ as a result of a development or the number of people who visit a particular attraction - could help inform decisions on whether such impacts are large or not and the direction of impact.

3.29 It is essential that where monetisation is not possible, a full qualitative assessment of the potential impacts is carried out and this is considered alongside monetised impacts when arriving at an assessment of VfM. In the context of DLUHC appraisals this could include a discussion on the potential environmental and other amenity impacts of changes in land use. For example, if one option appraisal largely consists of non-monetisable impacts due to the lack of data or the underlying nature of the policy, this will be assessed fairly against other options (which have monetised impacts) by judging into which VfM category it falls and providing a robust justification for it.

Value for money categories

3.30 VfM categories are recommended as the main way of summarising the VfM of an option as they combine all of the monetised and non-monetised impacts into an overarching summary measure. When deciding on VfM categories the impact of risks and uncertainties should also be taken into account before coming to an overall assessment of VfM.[footnote 18] They are a core feature of the Appraisal Summary Table.

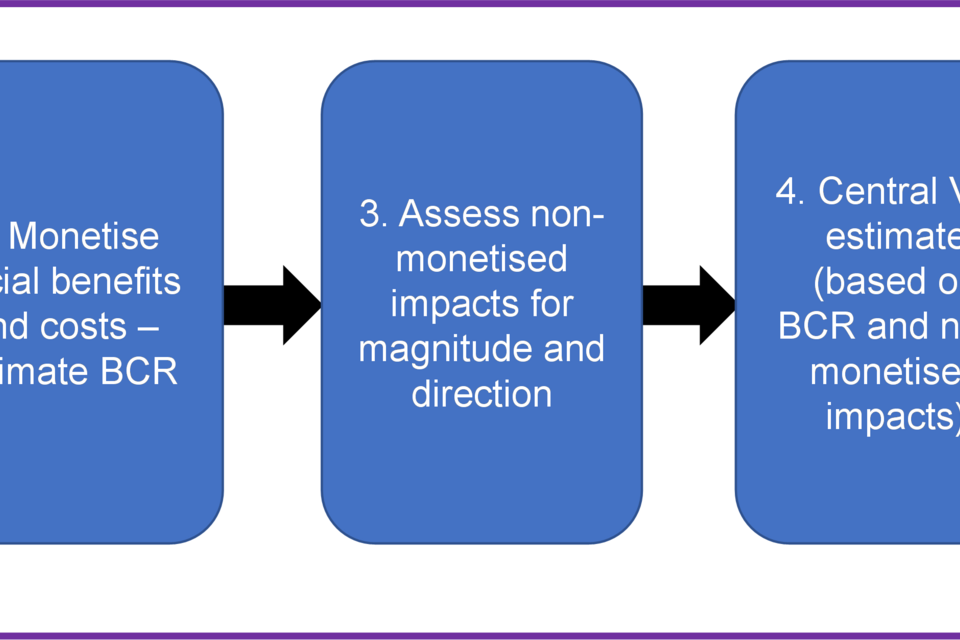

3.31 To produce a VfM category appraisers should:

-

Where possible monetise the expected impacts of the intervention – this allows estimation of the BCR;

-

Assess non-monetisable impacts for both direction and scale using the seven-point scale in Table 2 – when taken with the BCR these allow a central estimate of VfM to be created;

-

Assess the impact of varying key assumptions and uncertainties in the analysis through sensitivity analysis on the BCR and VfM rating;

-

Analysts should use switching values as part of their analysis to understand the scale of change needed for the scheme’s BCR to move to another VfM category and whether non-monetised impacts or changes in key assumptions will likely result in such a change. (See the next section on Estimating VfM for a discussion of switching values.)

Figure 2: Steps for deciding on a VfM category

- Develop evidence, options and narrative for a project.

- Monetise social benefits and costs – estimate BCR.

- Assess non-monetised impacts for magnitude and direction.

- Central VfM estimate (based on BCR and non-monetised impacts).

- VfM Category (based on sensitivity analysis and testing of assumptions.

3.32 The following VfM categories can be defined where public sector costs are positive[footnote 19]:

| VfM Category | Implied by…. |

|---|---|

| Very High | BCR greater than or equal to 4 |

| High | BCR greater than or equal to 2 and less than 4 |

| Medium | BCR greater than or equal to 1.5 and less than 2 |

| Acceptable | BCR greater than or equal to 1 and less than 1.5 |

| Poor | BCR greater than or equal to 0 and less than 1 |

| Very Poor[footnote 20] | BCR below 0 |

3.33 In the special case where the present value of costs is negative then the NPSV should be used alongside the categories in Annex I to define VfM.

3.34 As noted in the introduction to this section whilst the above bandings can be used to communicate the analysis, nothing should ever be described as VfM if it does not meet the policy objectives. Appraisal is a two-step process and all options that do not meet policy objectives must be filtered out at the longlist stage using the Options Framework, as per Green Book guidance.

Estimating VfM

3.35 To estimate VfM, monetised and non-monetised impacts need to be combined. The simplest approach to obtaining a central VfM estimate is to start with the BCR given by the monetised impacts and then ask the question:

How large do the non-monetised impacts have to be to shift the value for money of the policy to a different category, for example, from High to Medium (where the BCR is less than 2) or in the opposite direction from Medium to High?

3.36 The next stage is to assess all of the non-monetised impacts using the seven-point qualitative scale in Table 2 and ask the question:

Are any of the non-monetised impacts on their own or in combination large enough to shift the VfM category?

3.37 This requires:

- The calculation of a switching value which shows how much benefits or disbenefits would have to change to shift the option to the next VfM category;

- Comparison of the non-monetised impacts with the switching value to see if that size of change was likely.

A description of switching values is given in the Green Book (pages 52-54).

3.38 For example, suppose the BCR for a £10m investment is 0.9. It would require a £1m extra benefit to shift the BCR to 1 and for the investment to be categorised in a higher VfM category. Suppose there was a single non-monetised benefit and that it was assessed as being likely large so that it was likely greater than £1m. In this case the correct VfM category to use is Acceptable rather than Poor (which is what it would have been had only monetised impacts been considered).[footnote 21]

Examining the impact of uncertainty on VfM

Types of uncertainty

3.39 In reality there is likely to be significant uncertainty associated with costs and benefits which may mean that a range of VfM categories rather than a single VfM category is the best assessment. For this reason, key uncertainties in the analysis should be explored and their impact on VfM assessed.

3.40 For monetised impacts uncertainty may arise from several different factors:

- The degree to which an option has been fully defined, for example, the design of an investment is likely to be more uncertain at earlier business case stages;

- The methods used to monetise impacts, in particular, the:

- Robustness of the measure used – for example, emerging measures used in the adjusted BCR are likely to have higher levels of uncertainty than those used for the Initial BCR;

- Models used to estimate impacts for a particular option can often take considerable time to fully develop or may be based on key assumptions which are subject to uncertainty. At early stages of analysis (for example the Strategic Outline Case) results may be subject to more uncertainty because the models are less developed;

- Some issues are inherently complex – perhaps involving multiple economic actors - so are more difficult to model;

- The evidence base underlying the theory of change may be less developed resulting in a lack of clear economic model to assess impacts;

- The quality of data on which the modelling of options is based;

- Uncertainty about the future and how it will impact on key variables (including input, output and outcome variables) and economic behaviour.

3.41 For non-monetised impacts there is inherent uncertainty caused by the inability to monetise the impacts.

3.42 There is a range of literature dealing with these issues. In particular, the Aqua Book sets out the importance of understanding uncertainty, developing robust models and ensuring that results are properly quality assured. The National Audit Office (NAO) reviewed how uncertainty is modelled, assessed and communicated across government and ways in which that can be improved (see Financial modelling in government and Why quality assurance is important in modelling). Both these documents should be read by the user to support the assessment of uncertainty.

Assessing uncertainty

3.43 Uncertainty in each of the elements set out in the previous section should be examined when drawing conclusions about the VfM of an option. This includes:

- Identifying key uncertainties and risks in data, assumptions, models and the design of the options being developed;

- Assessing whether they are likely to be significant; and

- For significant areas of uncertainty, testing to understand the impact on VfM.

3.44 At a minimum, the impact of changes in key assumptions and inputs should be tested through sensitivity analysis. In particular:

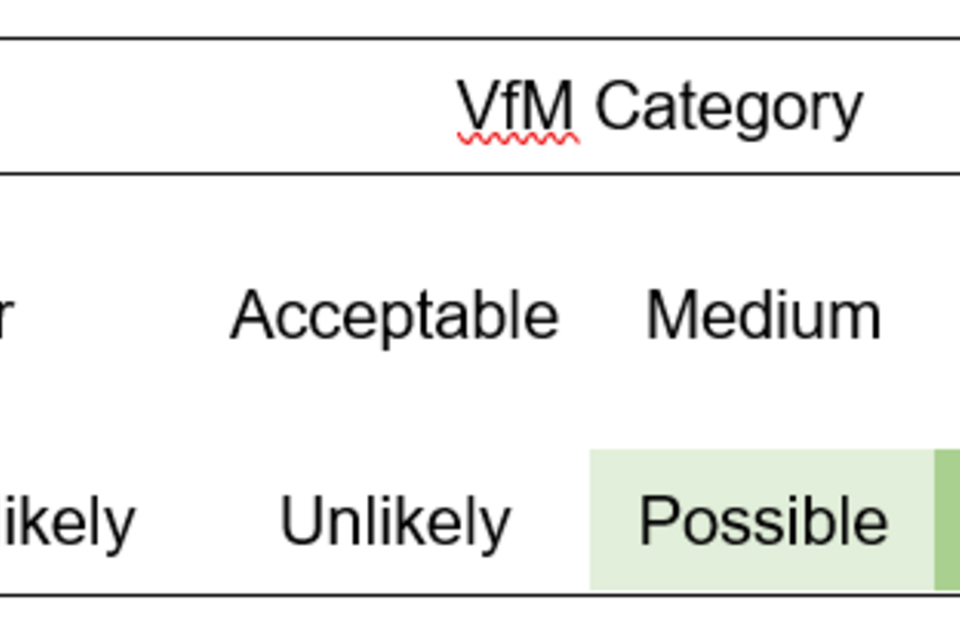

- Switching analysis should be used to assess how sensitive the VfM rating is to changes in costs and benefits.

- For large schemes, where uncertainty may have a larger impact on the costs and/or benefits of a scheme, other techniques such as scenario or Monte Carlo analysis could be considered.[footnote 22]

- For more detailed guidance on how to handle uncertainty in appraisal including Monte Carlo and scenario modelling see the Uncertainty Toolkit for Analysts in Government.

Communicating VfM

3.45 It is essential that any approach and subsequent judgement is transparent and clear to decision makers when non-monetised impacts are considered to imply a different VfM category compared to the BCR alone. To make the judgement transparent, VfM categories and BCRs should be communicated in a Value for Money statement (which should be included with the relevant AST). A Value for Money statement will lay out what the estimated VfM category is and why this has been decided.

3.46 If the VfM rating is different from the BCR because of the existence of significant non-monetised impacts or a VfM range is adopted because of significant risk and uncertainty, the Value for Money statement will need to explain this.

3.47 As noted above a VfM rating may represent a range of VfM categories rather than a single category. The full range should be reported (for example Acceptable to Medium or Poor to Acceptable).

3.48 Where it is possible to allocate likelihoods to different VfM categories this should done. An example of how that might be presented is shown below.

3.49 Alongside an assessment of VfM it is important to be clear about the quality of the analysis. This should highlight any issues with the approach taken, whether there was enough time to do the analysis, fitness for purpose of the modelling, gaps in data or other significant risks to the conclusions of the analysis.

3.50 Three examples of how judgement has been used to inform a VfM category are set out in the Value for Money statements below.

Box 1: Examples of a value for money statement

Value for money statement example 1

The estimated value for money of this policy is Acceptable to Medium.

The costs of the policy are £100m. While the estimated ‘Adjusted’ BCR of this policy is 1.15 (implying Acceptable VFM) there is a potential for wider area impacts from the intervention which would have significant benefits. The switching value to move the VfM rating from Acceptable to Medium is £35m. The non-monetised impacts from wider area impacts are judged to have a reasonable probability of being greater than this.

The modelling that has been carried out quickly using high level modelling. Whilst it has been undertaken by experienced analysts there are concerns about the robustness of the approach. Consequently, the results need to be treated with some caution.

Value for money statement example 2

The estimated value for money of this policy is Medium to High.

The benefits of this policy are reduced CO2 emissions (central estimate equal to £10m) and increased land value (central estimate equal to £190m). The cost of the policy is the grant of £100m. There are no significant non-monetised impacts estimated for this policy.

The ‘initial’ and ‘adjusted’ BCR of 2 indicate there is £2 worth of benefits per £1 of net public expenditure.

There are some uncertainties around increased land value which could be less than £190 m if the local housing market slows. This would result in a fall in BCR below 2 and Medium VfM.

The modelling is robust using appropriate techniques and local data. It has been carried out and assured by analysts and reflects key uncertainties.

Value for money statement example 3

The estimated value for money of this option is Poor to Acceptable.

The costs of this option are £100m compared to benefits of £130m giving an adjusted BCR of 1.3 which would equate to a VfM category of Acceptable.

However, there are significant non-monetised biodiversity and landscape disbenefits. In addition, there is some uncertainty over costs which might rise to £120m.

- For costs of £100m, biodiversity and landscape disbenefits of above £30m would change the VfM category to Poor. This is judged to be unlikely.

- However, if costs rise to £120m then disbenefits need only rise by just over £10m for the BCR to fall below 1 and VfM to become Poor. This is judged possible.

The options being developed are at an early stage which is why some impacts have not been monetised. The analysis has been carried out quickly – although by experienced analysts – and there are likely to be large changes in results as options and modelling develop.

Externalities

3.51 An economic appraisal should seek to capture all the benefits and costs associated with an intervention. This will include both private and external impacts. In some cases, external impacts can be fundamental to the case for intervention.

3.52 Examples of externalities include: landscape and biodiversity impacts from reclaiming land or building on it; air quality and greenhouse gas emissions; transport impacts from new developments which might increase local road congestion; crime impacts because of changes in the environment (such as from better lighting); health impacts; and better educational outcomes from reduced overcrowding (see Annex G for more examples).

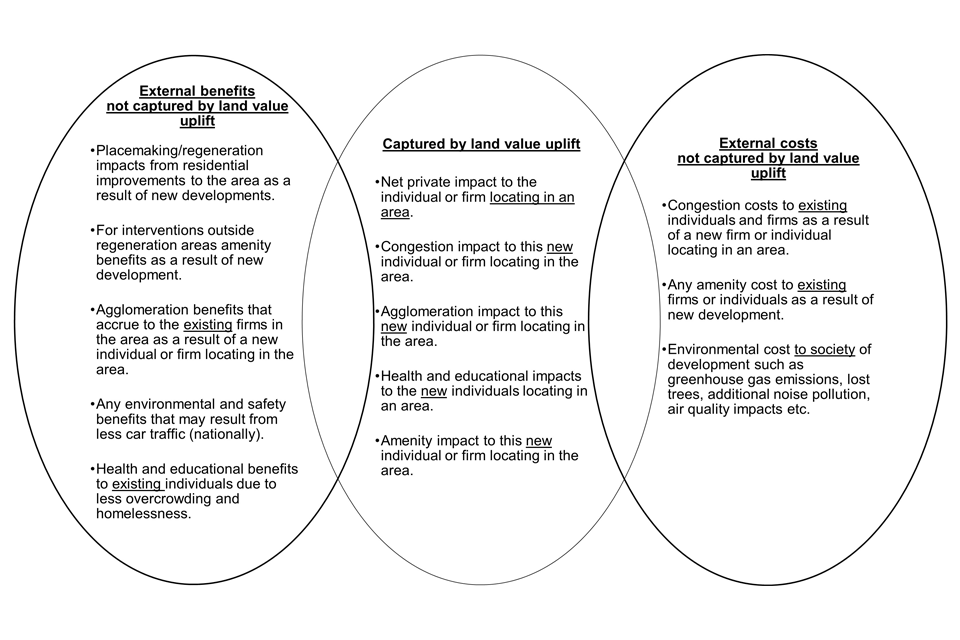

3.53 For the first time, estimates of wider area impacts in regeneration areas have been included in this Appraisal Guide and, where relevant, should be incorporated as part of the assessment of external impacts. Box 2 below provides a summary of wider area impacts and the work underlying them. Annex G provides a full overview of what is meant by wider area impacts and the methodology for calculating these.

Box 2: Wider area impacts

Wider area impacts refer to positive spill-over or external impacts from supply-side housing interventions with explicit placemaking and regeneration objectives resulting in the surrounding area becoming more desirable.

The guidance for the assessment draws on research commissioned by Homes England, based on a HM Treasury Green Book consistent hedonic pricing methodology, that examined the relationship between past Homes England interventions with placemaking objectives and post-intervention trends in house prices (over and above localised house price growth). The study found that, on average, regeneration supply-side housing projects are likely to have a positive wider ‘placemaking’ impact on the surrounding area, which can be measured based on net house price effects. Further analysis and spatial profiling enabled a methodology to be developed for assessing and monetising the wider area impacts of future projects.

The wider area impacts are applicable to supply-side housing interventions located within urban areas that have clear placemaking and regeneration objectives, which are likely to result in the surrounding area becoming more desirable. This should be clearly evidenced to the underlying rationale for intervention, the socio-economic and wider regeneration context and the objectives of the project as set out in the strategic dimension.

Wider area impacts are calculated based on estimating the uplift in the capital value of the surrounding housing stock, within a defined impact area, allowing for baseline trends and controlled variables to avoid double counting of other positive externalities. The modelled net rise in capital values implies a utility gain to local residents and reflects the increased willingness to pay of individuals for properties within the impact area, in the light of the improvements resulting from the scheme.

Given that this is a new methodology it should be included in the ‘adjusted’ BCR calculations.

3.54 The current version of the DLUHC Appraisal Guide provides estimates for the external amenity cost of development and the health benefits of additional affordable housing. Both the amenity cost of development and the health benefits of additional affordable housing should feature in the ‘adjusted’ BCR as these measures are evolving and there is some uncertainty around them. Some examples of how to deal with externalities are given below.

Box 3: Examples of externalities

Example 1: externalities are of second order importance

Assume there is a market failure which constrains the demand for housing (such as access to finance). Government intervention seeks to address this which leads to an increase in demand for new housing. As a result, additional houses are built and the monetised net private benefit associated with these additional houses - the additional land value uplift created - exceeds the public sector cost involved. While there are likely to be external impacts from such an intervention - such as reduced demands on health services because of better accommodation - these impacts are expected to be small in relation to the net private benefits and therefore they have little impact on the overall value for money assessment.

Example 2: externalities are important but not fundamental to the case

This could be similar to Example 1 with a similar market failure but instead the intervention ‘unlocks’ lower value development relative to the costs which results in a positive NPSV but a lower BCR. In this scenario, the economic case rests more strongly on the importance of wider impacts (externalities).

Example 3: externalities are fundamental to the economic case

In this example, assume that there is a potential development which generates an external benefit to society - perhaps there is an amenity and health benefit from developing a previously derelict site - but this development will not proceed without government intervention as there is insufficient private value. This is reflected in a Poor (less than one) ‘initial’ BCR. In this example, the value for money of the intervention relies on the significance of the externalities.

Natural capital

3.55 Where investments are likely to impact on natural capital including land, forests, biodiversity, fisheries, rivers or minerals then HMT green book supplementary guidance developed by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) – Enabling a Natural Capital Approach (ENCA) – should be used to assess impacts.

3.56 Stocks of natural capital provide flows of environmental or ‘ecosystem’ services over time. These services, often in combination with other forms of capital (human, produced and social) produce a wide range of benefits.

3.57 These include use values that involve interaction with the resource and which can have a market value (minerals, timber, freshwater) or non-market value (such as outdoor recreation, landscape amenity).

3.58 They also include non-use values, such as the value people place on the existence of particular habitats or species.

3.59 To consider the impact of an intervention on natural capital the following questions should be asked. Is the option likely to affect, directly or indirectly:

- The use or management of land, or landscape?

- The atmosphere, including air quality, greenhouse gas emissions, noise levels or tranquillity?

- An inland, coastal or marine water body?

- Wildlife and/or wild vegetation, which are indicators of biodiversity?

- The supply of natural raw materials, renewable and non-renewable, or the natural environment from which they are extracted?

- Opportunities for recreation in the natural environment, including in urban areas?

3.60 If the answer to one or more of these questions is “yes” or “maybe”, further assessment is recommended using the following four steps:

- Step 1: understand the environmental context to the proposal

- Step 2: consider how natural assets might be affected

- Step 3: consider the welfare implications, that is, how changes to the assets identified in Step 2 affect benefits provided to society by natural capital?

- Step 4: consider uncertainties and optimise outcomes

3.61 DEFRA supplies templates for assessing each of these four steps.

3.62 Annex Giii of this document sets out estimates of the external amenity benefits associated with different land types. These estimates include values associated with recreation, landscape, ecology and tranquillity. These values can be used to estimate the loss of amenity benefits from development on different types of land.

3.63 Given the importance of Greenhouse Gases the next section discusses their estimation and valuation.

Greenhouse gases and climate change

3.64 Analysts should where possible quantify and appraise the impact of options on carbon emissions. Carbon emissions may arise for a number of reasons including:

- Materials used in the development of sites and refurbishment of structures;

- Transport of materials or changes in trip patterns from new residential or commercial sites;

- Consumption of fossil fuels for heating, lighting or powering electrical appliances.

3.65 Some policies – such as better insulation or home generation of renewal energy – may reduce carbon. Newer buildings will generally be built to higher energy efficiency standards than older ones and it is important to factor in renewal of the building stock when assessing impacts.

3.66 Policy appraisal on climate change mitigation in DLUHC should use the Supplementary Green Book guidance on Valuation of energy use and greenhouse gas emissions for appraisal.

3.67 The guidance provides details on how to quantify and value energy use and emissions of greenhouse gases. It is intended to aid the assessment of proposals that have a direct impact on energy use and supply and those with an indirect impact through planning, land use change, construction or the introduction of new products that use energy.

3.68 It contains sections on:

- Identifying the energy and emissions counterfactual and then policy interactions;

- Quantifying and valuing changes in energy use and in emissions;

- Identifying and quantifying other impacts, such as air quality; and

- How to present findings and report for Carbon Budgets.

3.69 The guidance is accompanied by 19 data tables containing detailed estimates out to the year 2100 for carbon values and sensitivities, retail and long run energy prices, variable energy supply costs, and a GDP deflator. While the central estimates should be used in core analysis, care should be taken to reflect uncertainty in these estimates, for instance through sensitivity testing.

3.70 The guidance is updated regularly and so analysts should check that the latest version of the guidance is used in analysis.

3.71 For assessing how a policy / programme could be impacted by a changing climate, Supplementary Green Book Guidance on Accounting for the effects of climate change should be used. This supports the appraisal of policy options in the face of climate risks and uncertainty, and how adaptation of policies, programmes and projects can build resilience and enable flexibility in decision making.

3.72 The uncertainty over the future impacts of climate change and the importance of interconnections mean that climate resilience can prove important in unexpected areas of policy. Defra’s supplementary guidance supports analysts in identifying whether and how their appraisal should include climate risks.

3.73 There are other analytical challenges which help make appraising climate risk unique: thresholds and tipping points, long time horizons, the importance of early intervention, and lock-in. The guidance also supports analysts to address these challenges correctly.

Public service transformation, constitutional and social policies, and fiscal benefits

3.74 In addition to levelling up and housing DLUHC leads on a number of the government’s major social programmes. These include the Supporting Families programme; policies to deal with homelessness, rough sleeping and domestic abuse; policies to encourage public service improvement, social cohesion and integration; and policies to improve the voting process and wider devolution issues.

3.75 Appraisal of social policies and public service improvement is based on the same principles contained in the Green Book but can present additional challenges, in particular estimating and monetising the net impact of redesigning services on the use of public services and wider economic and social outcomes. Detailed guidance on appraising public service improvement and social policies is set out in Supporting Public Service Transformation: cost benefit analysis for local partnerships.

3.76 Alongside this guidance, the Greater Manchester Combined Authority (GMCA) Research Team has developed a Unit Cost Database, to help with the appraisal of service transformation and social policies. Using the best available research from various government and academic sources, the database provides fiscal, economic, and social cost estimates for over 600 outcome measures covering a range of issues from crime, education, employment, fire, health, housing and social services. The database provides costs which can be used to monetise outcomes relevant to social policies in terms of costs to public services (fiscal costs) and the wider economy and society. The database is widely recognised across government as the best available source for information on the costs of a number of issues and is being extensively used for various appraisal projects across government departments and local authorities.

3.77 In addition to the guidance and the Unit Cost Database, the GMCA Research Team has also produced a model which acts as a template for carrying out cost benefit analysis.

3.78 Appraisal of Union, devolution and constitutional policies must incorporate place-based analysis where possible, as outlined in the updated Green Book and discussed in Chapter 5. This is essential in highlighting which areas and local authorities will be disproportionately impacted by the policies.

4. Land value uplift approach to appraising development

Introduction

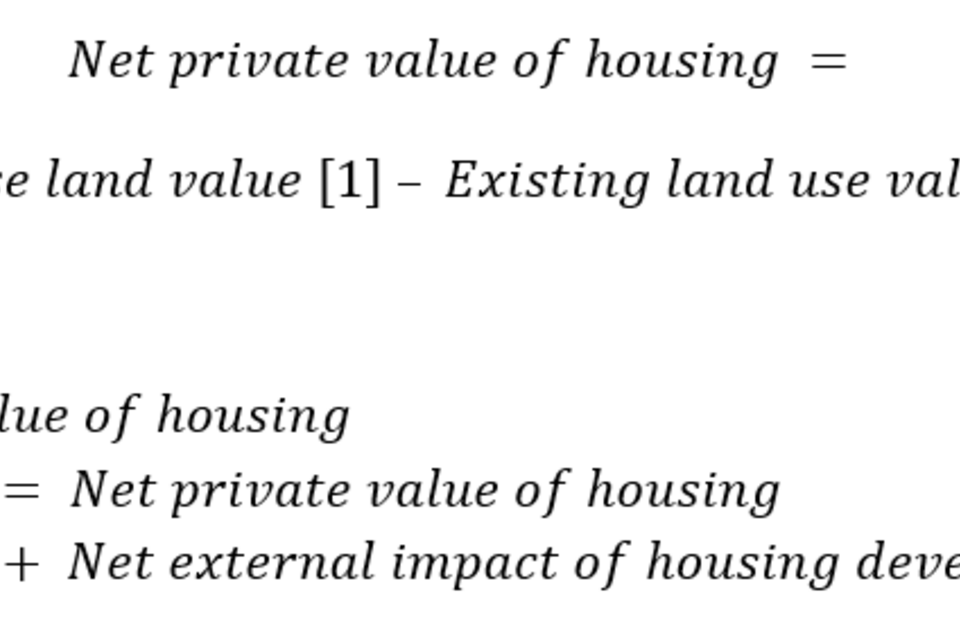

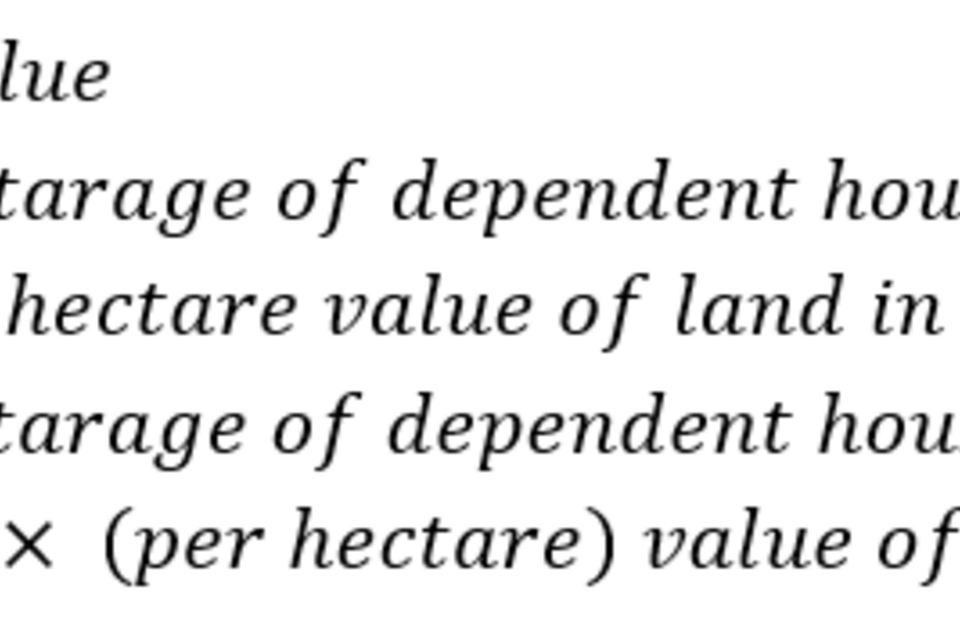

4.1 The primary benefits of new residential and non-residential investments occur through land value uplift, where development increases the value of the land above its previous use, allowing for production costs.

4.2 This chapter introduces the concept of land value uplift, outlines how it might be calculated and used in cost benefit analysis, and how externalities and additionality are taken into account. The approach is also set out in DfT’s Transport Analysis Guidance (TAG).

4.3 A step-by-step guide for how to appraise residential development is given in Annex B and for non-residential development in Annex C. Annex D presents more detail on measuring additionality.

Land value uplift explained

4.4 Land value uplift, when used in appraisals, represents the private benefit, or change in economic efficiency, of one form of development on a particular site compared to its previous use. In a housing context, land value uplift is the value of land when used for housing minus the value of land in its current use. Generally, land value uplift will be higher where housing is of higher benefit to society, for example, in locations where housing supply is constrained relative to demand and/or where a site is near to local amenities or well-developed transport infrastructure. In short, the value of land is determined by a number of factors, but most significantly by its use and location.

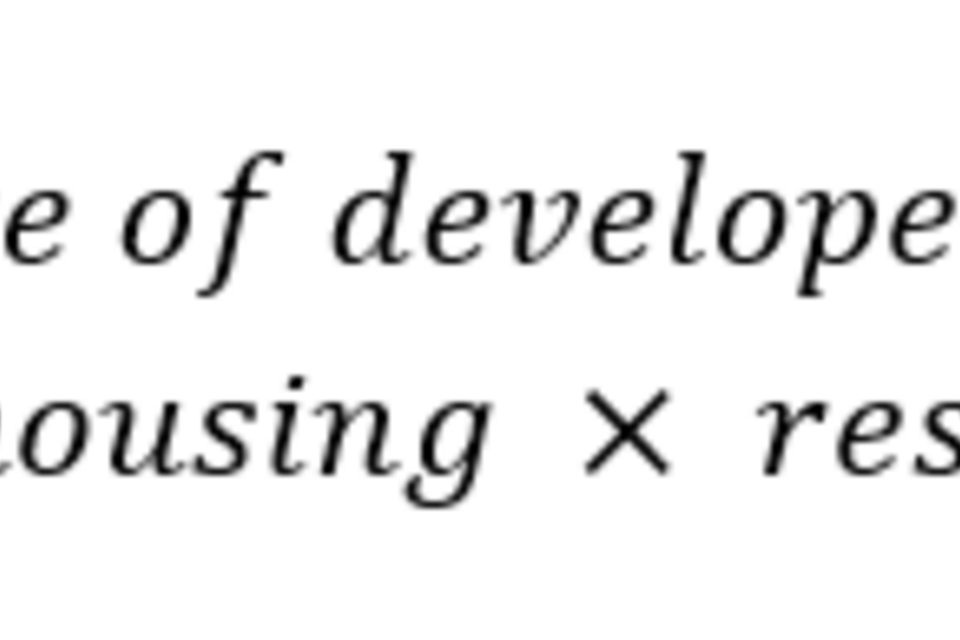

4.5 The Gross Development Value (GDV) of a site is used in determining land values and therefore land value uplift. GDV is the estimated total revenue a developer could obtain from the land. In the context of housing, it would effectively be:

4.6 A developer will also incur costs and would expect a minimum level of profit from developing a site. The residual method of land valuation gives the maximum price a firm is willing to pay for the land. In a competitive market, the firm will pay a price that gives a normal level of profit. The land price is therefore equal to:[footnote 23]

4.7 The uplift when land changes use is an estimate of the change, often increase, in economic efficiency arising from that change of use. In turn as discussed above this reflects the relative demand for and supply of land in its previous and new uses.

4.8 In an economic appraisal, analysts should seek to capture all costs and benefits of a policy. Costs should be economic costs and therefore capture the opportunity cost of the investment. For the developer investing money in the site results in foregone profits from investing the money elsewhere.[footnote 24] This foregone profit is a cost and should be subtracted off the land price. Similarly wage costs reflect the opportunity cost of using labour in the development and should be subtracted off land price.

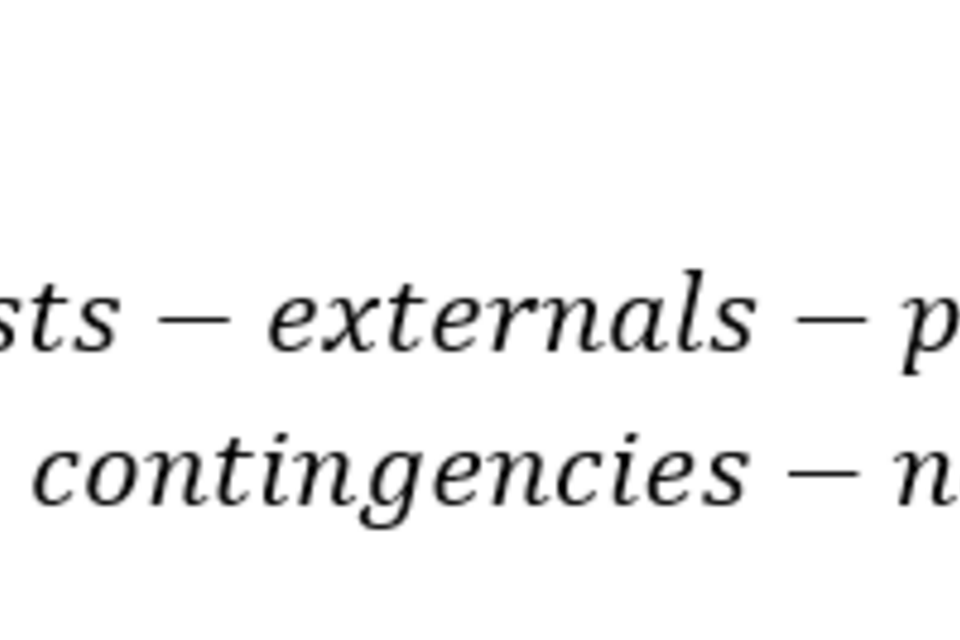

4.9 A simple example illustrates how land value uplift is calculated. Assume the economic value of land in its current use is low, for example, 50 owing to being an ex-industrial use brownfield site. Planning permission is then granted on that same site for a number of new homes. In its new use, assume the total obtainable revenue from the site is 300 (the GDV or sales revenue from the homes accruing to the developer), development costs to build the homes are 130 and the fees the developer occurs (such as legal fees, professional fees such as hiring quantity surveyors) are 30. Assume also that the market is competitive and that the level of normal profit is 40 – without this level of developer profit, the developer may instead choose not to develop this site and put their resources elsewhere. The new land value would then be:

4.10 The developer is therefore willing to pay 100 for the land in order to earn a normal level of profit of 40. In an appraisal, the net private benefits from this development is therefore 50 (the land value in its new use, 100, less the land value in its previous use, 50).

4.11 The key point is that the land value is derived demand and means the land value includes the returns to all factors of production less economic costs, that is, returns to capital, land and labour (300) less construction costs (130) less fees (30) less expected profit (40). Therefore, changes in land values as a result of a change in land-use for a development reflect the economic efficiency benefits of converting land into a more productive use.[footnote 25]

4.12 In practice some of the land value uplift is captured for the benefit of wider society through taxation and affordable housing requirements. If such obligations are included in developer costs or reflected in reduced income, they should be added to the land value as although they are a cost to the developer, they are a benefit to the recipient, such as for affordable housing.

4.13 Other planning obligations (Section 106, Section 278, CIL) can relate to both on-site and off-site infrastructure.

-

On-site infrastructure is often designed to benefit new residents and in such cases the benefit of this is likely to be captured already in the GDV of the proposals and so the land value uplift.

-

The purpose of off-site obligations is typically to mitigate for negative externalities caused by the development. In these circumstances, because the off-site obligation just removes the negative externality caused by the development, there would be no need to adjust the land value calculation.

-

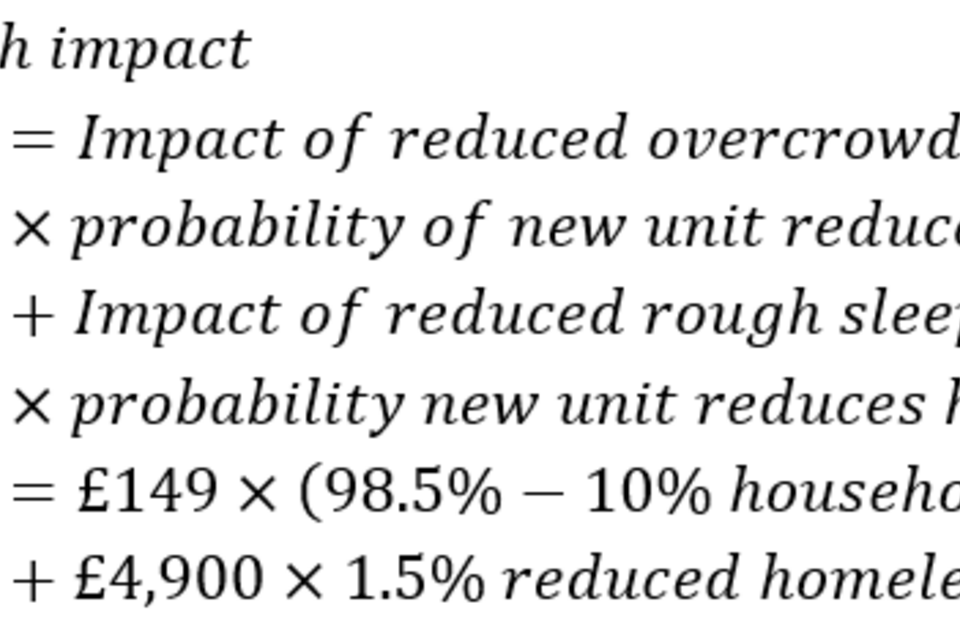

However, on-site infrastructure may also benefit existing residents and off-site infrastructure could potentially provide wider societal benefits beyond mitigating for the negative externalities of development. Where this is the case and planning obligations have been included in developer costs, it may be appropriate to treat all or a proportion of these costs as additional transferred land value. The assumptions adopted in calculating this additional benefit must be clearly set out and justified.