Disabled Facilities Grant (DFG) delivery: Guidance for local authorities in England

Published 28 March 2022

Applies to England

Chapter 1: Introduction

1.1 Home adaptations are changes made to the fabric and fixtures of a home to make it safer and easier to get around and to use for everyday tasks like cooking and bathing. Adapting a home environment can help restore or enable independent living, privacy, confidence and dignity for individuals and their families. Adaptations can include the installation of stair-lifts, level access showers and wet-rooms, wash and dry toilets, ramps, wider doors, and, in some instances, bespoke home extensions to existing dwellings as well as improvements to access to and from gardens. Heating systems, insulation and telecare and assistive technology (where it is capital) can be other forms of adaptations.

1.2 Disabled Facilities Grants are capital grants that are available to people of all ages and in all housing tenures (i.e. whether renting privately, from a social landlord or council, or owner-occupiers) to contribute to the cost of adaptations. They are administered by local housing authorities in England and enable eligible disabled people to continue living safely and independently at home. This includes autistic people, those with a mental health condition, physical disabilities, learning disabilities, cognitive impairments such as dementia, and progressive conditions such as Motor Neurone Disease. It includes those suffering from age-related disabilities and can also include those with terminal illness. The DFG is one of a range of housing support measures that a local authority can use to help enable people to live independently and safely at home and in their communities.

1.3 This guidance is to advise local authorities in England how they can effectively and efficiently deliver DFG funded adaptations to best serve the needs of local older and disabled people. The guidance will help local authorities to meet their responsibilities, including legal duties, and tailor local delivery to support their communities and the individual needs of disabled people, their family and carers. It does not make changes in policy, but instead brings together and sets out in one place existing policy frameworks, legislative duties and powers, together with recommended best practice, to help local authorities provide a best practice adaptation service to disabled tenants and residents in their area.

1.4 This publication follows calls from the home adaptations sector and local authorities for clearer guidance around local DFG delivery. It also follows the findings of the 2018 independent review of the DFG that recommended new guidance should set out expectations for local authorities in administering the DFG and the rights of a disabled person making an application for the grant.

1.5 The Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) (previously Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities) and Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) have worked closely with Foundations (the national body for home improvement agencies) and engaged with key home adaptations sector partners, local government representative organisations, and organisations which represent older and disabled people, to help ensure this guidance builds on the needs of older and disabled people, the local authorities who deliver the grant, and the wider home adaptations sector. We would like to take this opportunity to thank Foundations for their work in supporting us to help formulate this guidance.

Who is this guidance for?

1.6 This guidance is aimed at local authority staff at both local housing authorities (district councils, London boroughs and other unitary councils) and authorities responsible for the provision of social care services (county councils, London boroughs and other unitary councils). This includes those responsible for:

- strategic planning to ensure home adaptations are considered in an integrated approach to person-centred housing, health and social care services locally. This includes the local Health and Wellbeing Board, as well as those responsible for developing Better Care Fund plans

- organising and managing the home adaptations service

- identifying and assessing the needs of applicants, and making recommendations on how to meet those needs, including Occupational Therapists and Trusted Assessors;

- preparing specifications for adaptations and making other practical arrangements to put those recommendations into practice; and

- administering the systems for providing financial support for adaptations, including the Disabled Facilities Grant (DFG).

This guidance is applicable to those managing council house adaptations and may also be helpful for home improvement agencies and other related service organisations in England responsible for organising the home adaptations service.

1.7 Members of the public who would like to find out more about the DFG and application process, including disabled people, their family and carers, can find more information about the grant and how to apply or on their local housing authority website.

1.8 As the DFG is a devolved policy and grant, this guidance is aimed at English local authorities only. The National Assembly for Wales has issued separate Disabled Facilities Grant advice for Welsh local authorities. Scotland and Northern Ireland have separate schemes and grants available to eligible disabled people to adapt their homes. Links to how DFGs are delivered in all 3 devolved nations can be found below.

1.9 In so far as this guidance comments on the law, this guidance can only reflect government departments’ understanding of it. Local authorities are advised to seek their own legal advice.

1.10 Additional guidance and information on best practice from the wider home adaptations sector is highlighted where relevant throughout this document and at Appendix D: Resources.

Using this guidance

1.11 This guidance is divided into 7 chapters, each offering advice for local authorities in areas important to local DFG delivery, underpinned by the legislation at Appendix B: The legislation.

- Chapter 2: sets out the wider strategic context of the DFG, including the funding landscape for the DFG in England. It also outlines what good local strategic and operational collaboration looks like, and how local health, social care and housing authorities can work well together and with Private Registered Providers and housing associations to provide seamless person-centred support.

- Chapter 3: explains how, under the powers of the Regulatory Reform Order (2002), local areas can work together to develop and publish a local Housing Assistance Policy which aligns with wider social care, health, planning, disabled and older people’s strategies to best benefit local people who need adaptations. It outlines how local areas can set policy priorities, what policy content might include, and how local authorities can adopt, publish, monitor and revise policies. It also sets out policy tools and broader procedural considerations for all local authorities.

- Chapter 4: outlines key considerations for local authorities on how they commission home adaptation services, so that the right integrated teams are in place, enquiries and referrals are well-managed, and effective triage and needs assessment processes support applicants.

- Chapter 5: looks into the application process including what authorities should consider when designing and providing application forms, confirming the eligibility of the applicant and the required works. This includes the specification of the works, tendering procedures and service contracts. This chapter also sets out application approval requirements.

- Chapter 6: sets out how local authorities can best work with contractors and oversee the delivery of home adaptation works, including developing a list of accredited builders, managing contracts, supervising, providing payment and signing-off the works.

- Chapter 7: explains how assistive technology can be included as part of a home adaptations package to help people live safely and independently.

Chapter 2: Strategic context of the Disabled Facilities Grant

Wider strategic context

2.1 A suitable home can help disabled people of all ages to build and sustain their independence and maintain connections in their community. There are currently too many older and disabled people living in homes that make it difficult for them to do everyday tasks like washing and using the bathroom, cooking or getting out and about easily. Many homes are poorly designed for older age or changes in care and support needs. In fact, in 2019-20, around 1.9 million households in England had one or more people with a health condition that required adaptations to their home.

2.2 Government’s ambition is to give more people the choice to live independently and healthily in their own homes for longer, with fewer people staying in hospital unnecessarily or moving to residential care prematurely when that is not where they want to live. Adaptations can reduce the amount of formal care and support an individual may require, as well as often making the difference between being able to continue living in their current home or not.

2.3 Government wants more people to benefit from home adaptations to meet their needs, and will continue to support local areas to meet their statutory duty.

Disabled Facilities Grant funding

2.4 Since 2015, government has provided funding for the DFG through the Better Care Fund (BCF) in recognition of the importance of ensuring adaptations are part of an integrated approach to housing, health and social care locally, and to help promote joined up local person-centred approaches to supporting communities.

2.5 Government provides ringfenced DFG funding to Better Care Fund budget holders (usually authorities responsible for the provision of social services, including county councils, London boroughs and other unitary councils). Funding must be spent in accordance with Better Care Fund plans which are agreed between local government and local health commissioners, and owned by the Health and Wellbeing Board. It is important that those responsible for housing and home adaptations locally are involved in developing those plans.

2.6 In two tier areas, district councils are responsible for home adaptations and provision of DFGs to eligible recipients. In these areas, county councils must work with district councils to agree the use of this funding, and ensure that sufficient funding is passed to districts to meet these duties. A portion of DFG funding can be retained to pay for social care and housing capital elements of joined up health, social care and housing projects at county level, where this is agreed with Districts (see para 2.12). Local authorities and local health and care commissioners can also choose to add to government funding for home adaptations from their own budgets.

2.7 Authorities may decide to spend government funding for the DFG in 3 ways:

- Approving DFGs in accordance with the Housing Grants, Construction and Regeneration Act 1996 (the 1996 Act) (see Appendix B: The legislation)

- Providing housing assistance in accordance with a locally published Housing Assistance Policy under RRO powers (see Chapter 3).

- Using a portion of the DFG funding for other social care capital funding purposes (as locally agreed with district councils in two-tier areas).

2.8 Authorities can apply a mix of these options to meet local priorities but should consider that:

- the local housing authority has a statutory duty under the 1996 Act to provide adaptations for those who qualify for a DFG.

- the primary role of government funding is for the provision of home adaptations to help eligible people safely access their home and key facilities within it. Government funding is via a capital grant so must not be used for any revenue purposes. Local authorities are responsible for correctly classifying expenditure in their statutory accounts. Further guidance on capital/revenue and services that can be funded are covered in Appendix A.

- Government funding for the Disabled Facilities Grant is intended to fund adaptations for owner occupiers, private tenants, or tenants of private registered providers (housing associations). Eligible council tenants can apply for a DFG in the same way as any other applicant. However local housing authorities with a Housing Revenue Account (HRA) should self-fund home adaptations for council tenants through this account. A provision was made for expenditure in the HRA as a ‘Disabled Facilities Allowance’ in the 2012-13 self-financing settlement, alongside information on how to calculate it in subsequent years. The same applies to applications from tenants living in dwellings managed by an Arms-Length Management Organisation (ALMO) but owned by the local authority.

2.9 Chief Executives of Local Housing Authorities must send MHCLG an annual declaration of grant usage which states they have spent the funding in accordance with the grant conditions. (Authorities are also requested to provide DFG delivery data to MHCLG through their annual DELTA questionnaire return.)

2.10 Local housing authorities can provide financial assistance from their own budgets to those who do not qualify for home adaptations funding under the statutory duty or to top up government funding (see local flexibilities in Chapter 3).

2.11 Where a portion of the DFG funding is used for other social care capital projects this must be agreed as part of, and spent in accordance with, the approved local BCF spending plan that was developed in keeping with the BCF Policy Framework and Planning Requirements.

2.12 Local authorities are encouraged to consider the level of demand for adaptations locally, and use this freedom only to fund wider projects which are likely to reduce overall demand for DFGs, so that more people can receive the adaptations that they need. Good examples of wider social care capital projects include improving toilet/showering facilities in temporary accommodation to help support disabled people including those sleeping rough, or contributing to the cost of building accessible housing for disabled people in circumstances where this would be more cost effective than adapting a current property. Further case study examples of innovative use of DFG funding are available on the Better Care Exchange and National Body for Home Improvement Agencies web sites.

Local strategic collaboration

2.13 While the administration of DFGs is the responsibility of the local housing authority, it is important that other bodies and especially social services authorities and health commissioners, play a full and active part in strategic planning of home adaptations and related services.

2.14 Local housing authorities in England have strategic responsibilities to consider housing conditions in their area including the need for new housing under section 8 of the Housing Act 1985. As they assess housing needs and develop housing strategies, section 3 of the Chronically Sick and Disabled Persons Act 1970 means they must consider the special needs of chronically sick and disabled persons.

2.15 Creating a home environment that supports people to live safely and independently can make a significant contribution to health and wellbeing. It is therefore vital that in planning for the housing needs of disabled people, local housing authorities work closely with local health and care commissioners, and ensure strategic join up, including in use of the DFG, to align housing, health and social care aims.

2.16 This should be achieved through the process of developing BCF plans that are signed off by Health and Wellbeing Boards. For more information on the BCF process, please refer to the BCF Policy Framework and the DFG section of the BCF Planning Requirements.

2.17 Examples of good practice joint working between local health, care and housing authorities include:

- Inclusion of local housing leads (council or district level) on health and care focussed integration boards (including health and wellbeing boards) to support a joined-up and strategic focus on prevention and wider determinants of health.

- Health, adult social care and housing authorities jointly commissioning schemes that support people as they navigate between the health and care system. This could include home adaptation schemes that support people discharged from hospital and a home first approach.

- Health Commissioners working with housing authorities to target DFG support to ensure resources reach the most vulnerable residents in a community through sharing health data and analysis.

- Pooling revenue funding to provide a wraparound support to recipients of home adaptations (for example, commissioning handyperson services) to provide joined-up person centred care.

2.18 Please refer to the Better Care Exchange and National Body for Home Improvement Agencies websites for more best practice case studies.

2.19 Government wants to make joint working easier between the health service, social care, and local government. Subject to passage of the Health and Care Bill, Integrated Care Boards (ICBs) will take on the commissioning functions of the Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) as well as some of NHS England’s commissioning functions. Integrated Care Partnerships will bring together health, social care, public health (and potentially wider representatives where appropriate). This will put more power and autonomy in the hands of local systems, to plan and deliver seamless health and social care services. See further details on the Health and Care Bill: Integrated Care Boards and local health and care systems.

2.20 The next sections outline the legal responsibilities of different bodies and how they can best work together to ensure a seamless DFG service for local people.

Collaboration in DFG service provision

Role of local housing authorities

2.21 Local housing authorities have a statutory duty under the 1996 Act to provide adaptations for eligible disabled people, as well as wider powers to provide discretionary housing assistance through the Regulatory Reform Order (see Chapter 3). The administration of DFGs is the responsibility of the local housing authority, through all stages from initial enquiry (or referral) to post-completion.

2.22 District councils in two tier areas have a duty to consult their social services authority (county council) on the home adaptation needs of each disabled person seeking a DFG. While it is always the district council who must decide an application, if district and county councils collaborate effectively it would be rare for a district to decide not to approve an adaptation recommended by the county.

2.23 A local housing authority may also provide a range of other housing assistance services, for example, information and advice around housing options, or handyperson’s services, which can provide minor repairs, and safety, security and efficiency checks and fittings, as well as signpost relevant people to additional support, such as adaptations.

Role of social care authorities

2.24 Social care authorities have wide-ranging powers and duties to meet the needs of disabled people living in their area who require care and support. The responsibilities of authorities who provide social services are set out:

- for adults in the Care Act 2014; and

- for children in Part 3 of the Children Act 1989, as well as section 2 of the Chronically Sick and Disabled Person’s Act 1970.

Powers and duties under the Care Act relate to provision of assistive technology in the home, aids, equipment and adaptations. These include a duty to provide minor adaptations up to the value of £1,000 as well as other equipment to any value.

2.25 Where an application for DFG has been made, social service authorities should work closely with the housing authority to assess the needs of the individual. The social care authority should consider the wider social care needs of the applicant, including and beyond any adaptation required.

2.26 Where the social care authority determines that a need has been established it is their duty to assist, even where the housing authority is unable to approve or to fully fund an application. So for example, where an applicant for DFG has difficulty in meeting their assessed contribution from the DFG means test or the work will cost more than the upper limit, the social care authority can step in to provide financial assistance. Or if a disabled person is assessed as needing an adaptation which is outside the scope of the statutory DFG duty, then the social care authority can provide it.

2.27 Social care authorities may also consider using their powers under the Care Act 2014 to charge for their services where appropriate.

Working together

2.28 To ensure delivery of seamless, person-centred support including for eligible people requiring adaptations, it is essential that housing, health and social services authorities work well together given the overlap in their duties and responsibilities. This includes in circumstances where timely adaptations delivery can help facilitate people being safely discharged from hospital.

2.29 It is good practice that respective authorities should hold regular meetings between senior officers and publish on each authority’s website a clear, unambiguous formal agreement on key issues and joint working to benefit the person requiring adaptations, including:

- streamlining processes, including systems for joint assessments, cross-referrals and signposting between housing, health and social care services;

- acceptable timescales for adaptations delivery; and

- funding arrangements.

2.30 The formal agreement should include reference to:

- local agreement surrounding the integration of services. Integration of services locally can bring together policies and options to provide person-centred support such as DFG, Integrated Community Equipment Service (ICES), and social care. Delivering person centred support in this manner means that individuals are often able to get the best support for their situation. Alongside this, revenue costs can be shared between health, social care and housing.

- the use of budgets for minor adaptations and equipment and how that links with DFG funding. For instance, equipment which can be installed and removed easily with little or no structural modification of the dwelling is the responsibility of the social services authority. For larger items such as stairlifts and through-floor lifts which may require structural works to the property, help is normally provided through the DFG.

2.31 To ensure adaptations are progressed as quickly as possible respective authorities should agree a joint approach to the funding of different types of adaptations, unless there are exceptional circumstances. In some cases both equipment and adaptations are required. For example, where authorities agree to fund hoists through the DFG it would not be appropriate to order a sling separately unless the delivery and installation of both can be suitably arranged. The disabled person and their carers or family should experience a joined-up service.

2.32 Authorities may also choose to pool some of their funding to support person-centred services. For example, given the overlap in duties to provide minor adaptations up to £1,000 housing and social services authorities could choose to pool funding for adaptions up to £1,000 to avoid arguments over funding delaying the adaptations that local disabled people need.

2.33 Neighbouring housing authorities may also agree to pool funding across a wider area to provide greater flexibility in using DFG funding to meet local demand, where some authorities have underspends while others have waiting lists. Doing this can also smooth the risk that a few exceptionally large applications take up a significant proportion of the overall budget for an individual area. The operation of pooled funds should form part of Better Care Fund plans and be overseen by regular meetings between senior officers.

Collaborative working between housing and social services

An increasing number of authorities are recognising the benefits of establishing person centred services that appear seamless from the perspective of the disabled person and their family. For example, some authorities have seconded housing and social services staff into integrated teams that provide minor adaptations and equipment as part of a package of support including access to DFGs.

By joining up delivery it becomes easier to track outcomes and to monitor the effect that home adaptations have on the ongoing need for domiciliary care and preventing avoidable moves into residential or nursing care.

Some authorities are also starting to use predictive analytics to identify cases where preventative interventions can support carers, prevent falls and reduce loneliness involving the provision of adaptations and assistive technology. With the total annual cost of fragility fractures to the UK at an estimated £4.4 billion which includes £1.1 billion for social care; joint initiatives that can pre-empt a fall are likely to provide good value for money.

Working well with Private Registered Providers and housing associations

2.34 DFG is available to tenants of Private Registered Providers and housing associations. However, there are some different requirements compared to applications from owners which means that an authority could operate different processes so long as tenants receive a comparable level of support and experience similar timescales for the completion of works. This adds a further dynamic to the process.

2.35 Housing association tenants now account for around 22% of all grants approved. Therefore, good partnership working between local authorities and housing associations is essential to making the adaptation process run smoothly.

2.36 It is essential that local authorities are clear and have agreed with housing associations and Private Registered Providers operating in their area the expectations around any contribution to funding, timeframes for approvals and for works to be undertaken.

2.37 As with delivery between the housing and social services authorities it is vital that all work together operationally to ensure the best outcome for the tenant.

2.38 It is recommended that local authorities hold regular meetings with Private Registered Providers and housing associations so that where issues arise there is an effective communication pathway which allows clear and open engagement between all parties and for tenants to be kept informed of decisions and progress on any agreed work.

2.39 There may be instances where additional work is required to a tenant’s property in addition to the DFG application (such as other repair work). Again to minimise disruption to the tenant the local authority and Private Registered Provider or housing association should engage to agree the best times to schedule works.

Working with housing association landlords

Foundations Independent Living Trust, Habinteg and Anchor Hanover have published new guidance that makes recommendations for improving the situation in social housing, including:

- Promoting the use of landlord applications (instead of tenant applications) for the majority of cases – removing the requirement for means testing and ensuring the landlord is giving permission.

- Landlords to manage the delivery of adaptations in their own stock, with investment over and above DFG to improve the long term accessibility of their stock – reducing the number of adaptations that get ripped out upon change of tenancy.

- Greater use of adapted housing registers to make the best use of already adapted stock by enabling tenants to be matched effectively.

Chapter 3: Developing a local Housing Assistance Policy

The Regulatory Reform Order

3.1 The Regulatory Reform (Housing Assistance) (England and Wales) Order 2002 (RRO) provides general powers for local housing authorities to provide assistance for housing renewal, including home adaptations. The powers, detailed in Article 3, can only be used in accordance with a published Housing Assistance Policy. This section of the guidance can help authorities to develop or review their policy.

3.2 The wide-ranging powers enable authorities to give assistance to people directly, or to provide assistance through a third party such as a Home Improvement Agency, providing the assistance will improve living conditions in their area. This can include supporting people to:

- purchase a new home (whether within or outside their area) where the authority either purchases their existing home, or is satisfied that purchasing a new home would provide a similar benefit to adapting their current home;

- adapt or improve their home (including by alteration, conversion, enlargement, or installation of equipment or insulation);

- repair their home;

- demolish their home and build a replacement.

3.3 This can include funding adaptations to be added to the design of a new build home where the prospective owner has applied for assistance.

3.4 Assistance can also be given to pay for any associated fees and charges, including in cases where the work does not in the end proceed, as long as the authority is satisfied those fees fall within the terms of their local Housing Assistance Policy.

3.5 By publishing a Housing Assistance Policy under the RRO, housing authorities can use government funding for the DFG more flexibly. This funding is primarily for the provision of home adaptations to help people to live independently, so it is important for any local Housing Assistance Policy to clearly set out what additional adaptations assistance is to be provided. However, the wide powers enable local authorities to offer other forms assistance such as repairs, or assistance to move, if an applicant’s home is unsuitable for adaptation.

3.6 Policies can also include measures to speed up DFG delivery. For example, a local authority could develop a simplified system to deliver small-scale adaptations more quickly, for example, to deal with access issues, to enable rapid discharge of people from hospital, or to prevent admission to hospital or residential care.

3.7 While the RRO gives discretion to local authorities, it is important to note that authorities still have a statutory duty to approve DFG applications which meet the statutory requirements.

Improving delivery through a local Housing Assistance Policy

Housing Assistance Policies can be used to streamline the application process for home adaptations, particularly for the most common types of work such as those to modify a bathroom, create a ramped access or install a lift. This may include a brief application form, limiting the situations when the means test applies and varying the requirements around contractors.

Providing a Home Improvement Agency to help and support with making a valid application is also likely to improve take up of the grant and ensure that adaptations are fit for purpose. Authorities may consider making it a condition that any discretionary grants or loans are managed by an approved agency service.

For counties, it is good practice for district councils to collaborate in aligning their policies to provide a consistent approach. There may be specific issues that apply to individual districts but the main provisions should apply across the county, including the role of the county council and situations where social care funding will apply.

Aligning with social care, health and older people strategies

3.8 Housing, social services departments and the National Health Service (NHS) are delivering increasingly integrated services for vulnerable households that recognise the benefits of enabling people to stay in their own homes wherever possible. Poor housing can be a barrier for older and disabled people, contributing to immobility, social exclusion, ill health and depression. Housing assistance policies can contribute by enabling people to live with greater independence in secure, safe, well-maintained, warm and suitable housing.

3.9 Through local Better Care Fund plans, health, and social care authorities are required to agree a joined-up approach to health, social care and housing support to improve outcomes for residents. Housing authorities should also be involved in the discussion on the use of DFG funding. A Housing Assistance Policy that considers the more strategic, flexible use of DFG funding alongside other sources of funding to provide home adaptations including minor adaptations can support this aim. In developing a Housing Assistance Policy, housing authorities should work with health and social care partners and look to align objectives with existing local social care, health and older people related strategies.

Working with local partners

3.10 Partnership working lies at the heart of any successful Housing Assistance Policy. Strategic partnerships enable a common vision backed by commitment of resources from the principal delivery agencies.

3.11 When considering how best to deliver the key outcomes, authorities may wish to consider the following types of partnerships:

- Local authority partnerships: In developing new housing assistance policies, local authorities may benefit from working together. For example, a group of local authorities could share the costs of developing new policy tools.

- Partnerships to address housing need: Planning to meet housing needs within an authority’s area could involve close liaison with housing associations, private landlords, developers, providers of support and advice services, social services, the NHS and planning colleagues.

- Health alliances: there is a clear linkage between poor housing and ill health, especially with an ageing population and more people choosing to live independently within the community. This generates a need for partnership working between housing authorities, health authorities, health commissioners, local GPs and social services.

- Home improvement agencies (HIAs) can play a major part in helping an authority achieve its client-focused objectives.

- Working with the voluntary sector: within any strategy LAs should think about the provision for the supply of a range of complementary formal and informal advice and advocacy services.

- Fuel poverty and energy efficiency partnerships: fuel poverty and energy inefficient homes can only be tackled effectively through partnerships at the local level with housing authorities working closely with HIAs, NEA (National Energy Action), the Energy Saving Trust and energy suppliers.

Identifying local issues, needs and expectations

Evidence-based policies

3.12 Identifying local issues, needs and expectations of local residents is the first step in establishing a robust Housing Assistance Policy. This depends on accurate and up-to-date information. The following list sets out the minimum requirement:

- details of the prevailing social and economic conditions, including fuel poverty;

- profiles of the age, health, health inequalities and disabilities of the local population;

- data indicating demographic changes and trends;

- knowledge and understanding of the local housing market;

- stock condition data, including energy efficiency;

- complaints data, and customer satisfaction surveys among existing home adaptation clients; and

- issues of concern raised by partner organisations and other stakeholders.

Setting policy priorities

3.13 Authorities will want to consider policy options, establish priorities for action, and subsequently review the policy on a regular basis. The priorities selected will be influenced by the strategic context for housing assistance and by the issues, needs and expectations identified. The local challenges facing individual local authorities will vary widely, and to ensure that resources are well used a careful appraisal of priorities is essential, involving residents and other partners before a final policy is adopted. The following provide some example priorities:

Client-based

3.14 Depending on local need, provision of assistance may target additional help for specific groups:

- Older people; by seeking to assist with maintenance, repairs, improvements or the provision of basic amenities. Older people are more likely to live in substandard and poorly heated homes and are also vulnerable in terms of home accidents or crime.

- Specific conditions; by providing a package of additional assistance outside the mandatory disabled facilities grant system, e.g. for those needing palliative care.

- Housing needs of black and minority ethnic communities or others with protected characteristics; in line with public sector equality duties, authorities should consider whether particular groups are facing disadvantage in accessing home adaptations and recognise the cultural needs of particular groups.

Motor neurone disease

Housing assistance polices can be used to respond to rapidly progressing and highly debilitating conditions such as Motor Neurone Disease (MND). Often people with MND want to continue to work during the early stages of the disease, which can make them ineligible for a DFG through means testing. But by the time they can no longer work an un-adapted home can make day to day activities very difficult to manage.

Some local authorities include provisions within their policy, such as:

- a fast-track process with no means testing for works up to £5,000.

- ignoring the earnings of the person with MND in the means test where larger scale works are assessed as being necessary and appropriate.

These provisions apply to a relatively small number of people but can have a significant impact upon their lives at a time of major upheaval.

Sector-based: Assistance to landlords

3.15 Homelessness, and housing need should be an important consideration for a local authority. The private rented sector often plays a key role in providing accommodation including for homeless families, and supported lodgings for young care leavers. Assistance may therefore support landlords or other partners to increase the supply of adapted accommodation.

3.16 Authorities may want to consider a policy to retain nomination rights to a rented property for a specified period of time where a landlord applies for assistance. This could mirror the option to secure nomination rights where a landlord applies for a mandatory DFG.

Working with private landlords

Research undertaken by the National Residential Landlords Association (NRLA) shows that only 8% of landlords let properties to people with accessibility needs and the biggest barrier to installing adaptations is the cost. However, 79% of landlords did not know that funding is available through the DFG.

The NRLA is working with a number of local authorities to provide more information to private landlords with the aim of encouraging more DFG applications and supporting landlords to make their portfolios more accessible for disabled tenants. It is good practice to include awareness raising a part of private landlord forums and other engagement regularly undertaken by local housing authorities.

Provision can be made within a Housing Assistance Policy to streamline the grant application process where the landlord makes the application and takes the lead in managing the works. As with the mandatory DFG, the means test would not apply but nomination rights could be applied to ensure that the property could be available for let to another disabled person in the future.

Theme-based

3.17 A policy may target assistance against themes. Examples could include:

- hospital discharge schemes; and

- home accident prevention or health and safety initiatives.

Policy content

3.18 The policy should set out the nature and extent of housing assistance that will be available, based on the evidence of needs identified. It should set out how the strategic aims and objectives of an authority will be met by appropriate and effective actions.

3.19 Authorities must also avoid fettering their discretion to provide assistance. This means that they must include a mechanism in place to consider applications for assistance which fall outside their policy. They may legitimately turn down an application for assistance that falls outside their policy, but only after individual consideration on a sound and informed basis. Such applications should be approved where appropriate.

3.20 It would be best practice for the full policy document detailing the assistance to be made available under the RRO to include the following:

- how the policy will contribute towards the fulfilment of the local authority’s strategic aims, objectives and priorities;

- a statement of the key priorities which the policy will address and the reasons for selecting them;

- the amount of capital resources that will be committed to implementing the policy, including resources provided by partner organisations;

- a description of the types of assistance available, what the assistance will be used for, and what key outcomes will be achieved by each form of assistance;

- the circumstances in which persons will be eligible for assistance;

- the amounts of assistance that will be available to eligible persons, and how these amounts will be determined;

- the types and amounts of preliminary or ancillary fees and charges associated with the provision of assistance that will be payable and in what circumstances;

- the process to be used to apply for assistance, including any preliminary enquiry system;

- how persons can obtain access to the process of applying for assistance;

- details of conditions that will apply to the provision of assistance, how conditions will be enforced and in what circumstances they may be waived;

- advice that is available, including financial advice, to assist persons wishing to enquire about, and apply for, assistance;

- the arrangements for complaints about the policy and its implementation;

- the arrangements for applications for assistance to be considered where these fall outside policy;

- key service standards that will apply to the provision of assistance e.g. how long it will take to approve an application for assistance once submitted, how long it will take for assistance to be completed once approved;

- local performance indicators and targets that will be used to measure the progress made by policy implementation towards meeting the authority’s strategic aims, objectives and priorities and the fulfilment of corporate strategies; and

- a policy implementation plan that will, amongst other things: state the policy commencement date; the planned date when a successor policy document will be issued; the frequency with which policy implementation (including performance against indicators and targets) will be reported and publicised; and the circumstances that might necessitate an earlier review of the policy document.

3.21 The forms of assistance should adhere to the powers set out in article 3 of the order (see para 3.1). The following are examples from existing policies across England:

- Relocation assistance: financial and practical support to move where that is more cost effective or delivers better outcomes compared to adapting the existing home.

- Hospital discharge grant: funding for urgent adaptations, repairs or modifications that will allow someone to be discharged from hospital sooner.

- Waiving the means test: for example, not requiring means testing for stairlifts to prevent falls or where the cost of the adaptations is below a certain amount.

- Home safety grant: funding to repair hazards in the home that can reduce risks leading to fewer falls and other accidents around the home.

- Pooled funding: For example to fund ramps where otherwise there would be delay while deciding if it is to be funded by DFG or social services.

- Fast-track adaptations: where an urgent need has been identified, bureaucracy is minimised to speed up assessment and delivery

- Palliative care: Assistance with fast-track works for terminally ill people being discharged from hospital or hospice.

- Dementia grants: small grants to fund modifications that would allow someone with a diagnosis of dementia to remain living safely in their home for longer.

- Smart Home Kits: such as a smart thermostat to control heating and hot water, video doorbell, smart switches, smart lightbulbs and an Alexa or Google Home for voice or other assistive technology grants (see The Disabled Facilities Grant and assistive technology)

- Funding more than the Maximum Amount: funding towards adaptation schemes where the cost exceeds the maximum amount for a DFG.

Fees and charges

3.22 Within their policies, local authorities should state what associated preliminary or ancillary fees and charges will be paid. This might include fees charged by agency services, private architects and surveyors, and could include either in-house or outsourced loan administration costs.

3.23 Clearly only reasonable and necessary fees and charges should be eligible for assistance. Authorities should actively compare these costs with other local authorities and service providers, and carry out market testing where appropriate. Authorities should seek to keep the cost of eligible fees and charges to a minimum but without compromising the quality of service provided to the customer.

Dementia grants

Many local authorities already include dementia grants within their housing assistance policies. They are typically preventative in nature and allow for adaptations to be provided with a diagnosis of dementia and before the condition escalates to the point where a DFG would otherwise become necessary.

The extent and cost of the works are usually relatively small (often less than £1,000) and involve a streamlined application process. The most common types of modification are:

- Labels and signs on doors and cupboards

- Task focussed lighting in bathrooms and kitchens

- Items of assistive technology, e.g. to provide reminders and to monitor activity

- Safer flooring

- Decoration to improve contrast between walls and floors

- Installing coloured fixtures to create a contrast for items like toilet seats and grabrails

These simple changes can help to keep someone living safely at home for longer, delaying the need for more costly care services or a move into residential care.

Local land charges for DFGs

3.24 As part of their Housing Assistance Policy authorities should set out when it will use discretion to place local land charges for an owner-occupier’s application and the cases when it would not demand repayment if the recipient of the grant disposes of the property (see Appendix B, B123 to B125).

3.25 Authorities should particularly consider whether it would be right to demand repayment in cases where:

- repayment of the grant would cause financial hardship;

- they have to move for their job;

- the move is related to their physical or mental health or well-being; or

- they need to move to provide or receive care from others.

3.26 Authorities are encouraged not to place local land charges where the application is being made for a child in a long-term foster placement.

Adopting and publishing the policy

3.27 Before providing alternative forms of assistance, a local authority should consider the expected life of the policy and plan capital resource allocations accordingly. The authority must then:

- adopt the Housing Assistance Policy according to its normal procedures for such matters;

- give public notice of the adoption of the policy; and

- ensure that the full policy is available on their website, preferably with a summary in plain English (and other languages as necessary).

Monitoring and revising the policy

3.28 Regular monitoring of the policy’s aims and objectives against performance targets, and customer feedback is essential to check whether policy implementation is satisfactory. Customers’ views and experiences of the services provided, and their needs and expectations for future services, will also be useful in considering whether revisions are needed.

Dealing with complaints and redress procedures

3.29 How clients initiate complaints and the appeals procedure when assistance is turned down should be written down and freely available.

Changes to policy

3.30 Where any significant changes are made to the published policy, these must also be formally adopted and published. Significant changes include those to eligibility and scope as well as any new forms of assistance introduced. Minor changes which do not affect the broad thrust of policy direction, can be accommodated without a formal re-adoption process.

Policy tools

3.31 The provisions of the RRO give local authorities wide discretion to provide assistance for housing renewal. Authorities should decide the most appropriate forms of assistance to best address the policy priorities they have identified. This section reviews the main policy tools which should be considered. Assistance may be unconditional or subject to conditions such as the requirement to repay a grant if the property is sold within 5 years.

3.32 The RRO contains important protections relating to the giving of assistance, whether it is given as a grant, loan or another form of help. It requires that:

- authorities set out in writing the terms and conditions under which assistance is being given; and

- before giving any assistance the authority must be satisfied that the person has received appropriate advice or information about the extent and nature of any obligation (financial or otherwise) that they will be taking on; and

- before making a loan, or requiring repayment of a loan or grant, the authority must have regard to the person’s ability to afford to make a contribution or repayment.

Grant assistance

3.33 Local authorities can make grant funding available for home adaptations and associated works. This might be for minor items of work, works outside the scope of the mandatory DFG, or to reduce the bureaucracy involved.

3.34 Where a local authority offers grant assistance it will need to consider whether to apply a means test. The specific form of means test will be for the authority to decide. Means tests are inherently complex and are not always appropriate. A simpler ‘passporting’ method linked to entitlement for other state benefits may be an alternative. In addition, for owner-occupiers the amount of unmortgaged equity in the property might be an important consideration in whether to make assistance available.

Loan assistance

3.35 The RRO also enables local authorities to offer financial assistance in the form of a loan. For example, an authority may wish to offer loans to help those required to make a financial contribution under the means test for mandatory DFG.

Types of loan assistance

3.36 There is a wide range of options available for local authorities to consider and it is important that they should seek proper, comprehensive legal and financial advice before offering loan assistance. The principal categories are:

- Interest bearing repayment loans: conventional loans either secured or unsecured with interest charged either at the current market rate or at a preferential rate and repayable in regular instalments over a period of time. Such loans are likely to be best suited to those with a regular income which would enable them to make the required repayments.

- Interest-only loans: conventional loans, usually secured, where the borrower only pays the interest charge on the amount borrowed in regular instalments. Repayments may vary as interest rates go up or down. The capital is repaid usually on the sale of the property. Again, this sort of loan is likely to be best suited to those able to meet regular interest repayments, and, where the loan is secured against the property where there is adequate remaining equity in it.

- Zero-interest loans: a conventional loan registered as a charge against the value of the property on which no interest is levied. The capital is repaid usually on the sale of the property. This type of loan may be best suited to those unable to make regular loan repayments, but who have substantial remaining equity in their home.

3.37 In deciding which is the right financial product for any circumstance, local authorities will need to make a careful assessment of the financial position of the applicant. In the case of equity release products they will also need to assess the current and possible future value of the property and other actual and potential charges on it. Where homes are already mortgaged the lender will insist on taking the first charge.

Loan administration

3.38 Local authorities must be aware of all aspects of consumer credit regulation and guidance. The principal regulators for financial services are the Financial Conduct Authority.

3.39 Any financial service providers including local authorities and housing associations may give advice about their own financial products. However, local authorities and housing associations must not offer financial advice on other financial products. They can only offer information on the availability of other products. Where loans are being offered, especially if the local authority is working jointly with another agency to promote any loan or equity release scheme, the person should be strongly advised to consult an independent financial advisor. Where appropriate, they should advise those considering equity release products to consult their family.

3.40 Local authorities and housing associations (but not their wholly owned subsidiaries) are exempt from the Financial Conduct Authority’s authorisation for mortgage lending and administration, arranging and advising. However, they must still adhere to the underlying key principles of mortgage regulation which will be taken into account in any case referred to the Local Government and Social Care Ombudsman. These are that:

- authorities must ensure that their procedures are open and readily accessible to members and clients; and that

- loans are administered in a manner which is both reasonable and fair.

3.41 The RRO is also clear that local authorities must satisfy themselves that recipients have received appropriate advice or information on any obligations arising from the assistance. This applies whether the local authority is providing the assistance directly or through third parties.

Broader procedural considerations

3.42 Local authorities are free to decide their own policies and procedures through the general power to provide assistance. However, authorities should consider:

- duties under the Local Government Act 1999 to provide best value through the operation of customer-focused, cost-effective, and efficient procedures;

- obligations enshrined in administrative law such as the duty to act reasonably and fairly;

- ensuring that policies and procedures are robust enough to safeguard and secure value for money from public funds and to minimise the risk of fraud; and

- developing procedures that are transparent, fair, and efficient. This will help mitigate against legal challenges or allegations of maladministration.

3.43 Authorities are also subject to requirements of the Equality Act 2010 because they are discharging a public function and providing a service to the public. This means that they are required to make reasonable adjustments for service users who meet the Act’s definition of having a disability (see Appendix B, B5), including those who are applying for a grant. This means, for example, that DFG services must be accessible to those with a visual or mobility disability.

3.44 The reasonable adjustment duty is anticipatory, meaning that local housing authorities should not wait for a reasonable adjustment request, but should plan on the basis that, in a DFG application context, a substantial proportion of their clients will be disabled and therefore arrangements should be put in place to anticipate this.

3.45 Authorities must also not discriminate against or harass a person applying for a grant on grounds of or for reasons related to their disability or any other protected characteristic under the 2010 Act. Failure by an authority to make a reasonable adjustment to assist disabled service users make their application is unlawful under the 2010 Act, as well as other forms of unlawful discrimination and harassment, and can ultimately result in civil proceedings at County Court.

3.46 Local authorities are subject to the Public Sector Equality Duty (PSED), and when carrying out their functions must give due regard to the need to eliminate discrimination, harassment, victimisation and any other conduct prohibited by or under the Equality Act, advance equality of opportunity between persons who share a relevant protected characteristic and others and foster good relations between persons who share a relevant protected characteristic and others. It is for local authorities to decide what is required to fulfil their duty and the government does not have a role in overseeing this.

3.47 A local authority that is failing to comply with the PSED may be challenged via Judicial Review. See guidance on the PSED for public authorities in England, Scotland and Wales.

3.48 Under section 343AA of the Armed Forces Act 2006 (inserted by section 8 of the Armed Forces Act 2021), local authorities are required to have due regard to the 3 principles of the Armed Forces Covenant when exercising certain housing functions, including allocating disabled facilities grants. Under this provision, special considerations for veterans may be justified in some circumstances. More information will be provided in the Armed Forces Covenant Duty statutory guidance to be published in 2022.

Chapter 4: Managing a home adaptations service

4.1 Once the local authority has set out their Housing Assistance Policy, and determined the key outcomes they wish to see from a home adaptations service, in line with the local Better Care Fund Plan, the next step is to understand the right way to commission the service.

4.2 Different authorities will take a different approach. For example, Housing Revenue Account funded adaptations for council properties may be managed by DFG housing officers or directly by council housing teams. However, it is considered good practice to offer a Home Improvement Agency service to support a disabled person and their family through the often complicated process of carrying out major building works. It is also good practice to consult disabled people in service design and delivery. This chapter uses the term “client” to collectively refer to the older or disabled person, the applicant and their family and carers.

4.3 Whichever route is chosen, it is good practice to undertake reviews of the service set up at regular intervals to consider whether the service is still delivering the best outcomes possible and whether service improvements can be made.

4.4 The aim of managing a home adaptations service should always be a seamless service for the client whose needs should be the primary focus. As a matter of good practice, the client should be involved in decision making throughout the process and the outcome of all discussions and agreements must be well documented.

Integrated teams

4.5 Local authorities should consider using a single, integrated team to handle the whole adaptation journey from first contact to completion of the works. A joint team, including both housing and social care professionals, overcomes the frustrations faced by clients when their case is passed between different organisations. There is emerging evidence that this more person-centred way of working reduces timescales and drop-out rates.

Managing initial enquiries and referrals

4.6 To ensure the quality and consistency of response, local authorities should consider establishing a one-stop shop to channel the majority of initial enquiries or referrals to a preferred point of access, for example, a social services contact centre, or an agency service.

4.7 Where authorities are working in partnership, the branding should clearly feature the titles and corporate logos of all the partner organisations to demonstrate their ownership of the common process.

4.8 Common training on an ongoing basis should be provided for those dealing with enquiries and referrals to ensure a consistent and appropriate service is provided. This will include disability equality training for all public-facing staff.

The right assessment team

4.9 Authorities should also ensure they have the right team of professionals to assess and recommend adaptations. For example, trusted assessors (in simple cases), paediatric occupational therapists, educational setting assessments and other occupational therapists and technical officers, particularly where major adaptations are required.

4.10 Trusted assessors are staff who are trained to assess people and their home environment for home adaptations in simple cases. They also know when to refer on to an occupational therapist for further assessment. It is good practice for trusted assessors to be supervised by an occupational therapist.

4.11 The most successful assessment systems involve occupational therapists and trusted assessors working together within multidisciplinary teams.

4.12 Some applicants will be assessed by a private occupational therapist. A district council must still consult the social services authority in these cases.

4.13 Whichever team makes the initial assessment, the final decision on awarding grant remains with the local housing authority. Decision making panel meetings that do not include the housing authority are strongly discouraged.

Foundations

Foundations are the government appointed National Body for Home Improvement Agencies in England. They offer a range of services to improve the local delivery of Disabled Facilities Grants. This includes:

- An accessible website with an extensive library and how-to guides

- A network of Regional Advisors providing information, support, and guidance

- Accreditation and quality standards for Home Improvement Agencies

- Bespoke training courses, including regular free online classes on understanding DFG

- Regular free events including monthly webinars and live regional DFG Champions Roadshows to share best practice

- Housing the National Healthy Housing Awards

- Consultancy support with service improvement reviews, including process mapping and drafting of Housing Assistance Policies

Support for local authorities

4.14 Further information on good practice in the delivery of home adaptations can be obtained from Foundations, a body funded by the government to support local authorities and home improvement agencies around local DFG delivery.

The key stages

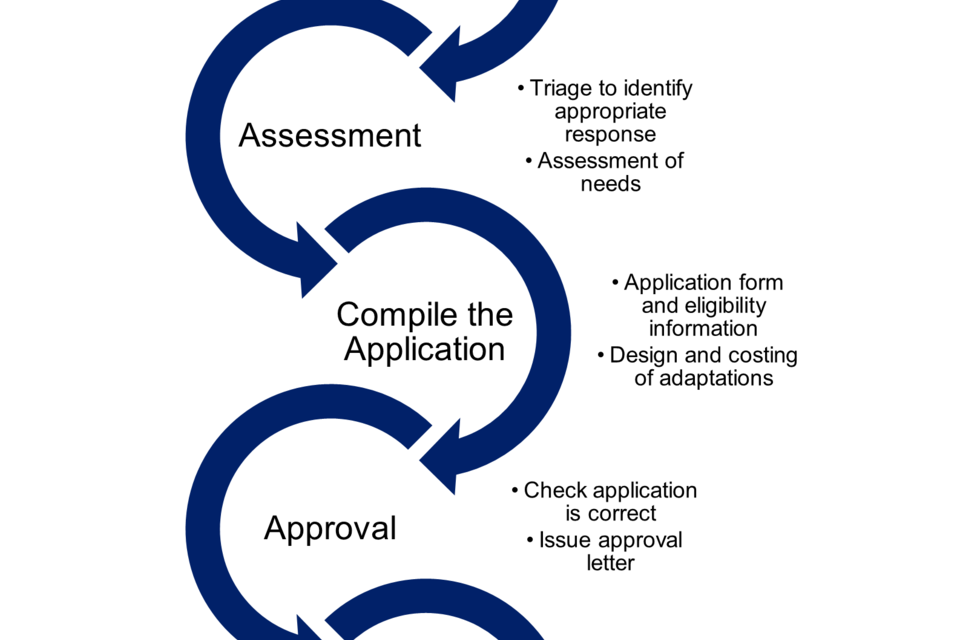

4.15 There are 5 key stages of delivering a home adaptation:

- Stage 0: first contact with services

- Stage 1: first contact to assessment and identification of the relevant works;

- Stage 2: identification of the relevant works to submission of the formal grant application

- Stage 3: grant application to grant approval

- Stage 4: approval of grant to completion of works.

A flow chart showing a best practice example of how the DFG process should work from first contact by a DFG applicant to the works being carried out.

4.16 The timescales for moving through these stages will depend upon the urgency and complexity of the adaptations required. More urgent cases should be prioritised for action, but larger and more complex schemes will take longer to complete. The following table sets out best practice targets, which should be met in 95% of cases. (see 4.36 to 4.39 for definitions.

Target timescales (working days)

| Type | Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 3 | Stage 4 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urgent & Simple | 5 | 25 | 5 | 20 | 55 |

| Non-urgent & Simple | 20 | 50 | 20 | 40 | 130 |

| Urgent & Complex | 20 | 45 | 5 | 60 | 130 |

| Non-urgent & Complex | 35 | 55 | 20 | 80 | 180 |

4.17 It is important to keep the client updated on progress (and any potential delays) at all stages. People told about the causes of delay are more likely to accept it and may offer ways to mitigate any problems.

First contact

4.18 Authorities should put in place pre-application processes to efficiently channel enquiries into the most appropriate type of assistance at an early stage or signpost them to more appropriate agencies to help resolve their problems.

The provision of good information, advice, and publicity

4.19 The provision of clear, concise, easy to understand and readily accessible information is a vital aspect of providing a good service. It is important that anyone who needs it has appropriate access to information about DFGs, local policies for providing assistance, and how to apply. Authorities, working with partner agencies, should produce information in a range of formats, including on the authority website. This should include:

- the types of grant, loan or other assistance available;

- whether their personal circumstances make them eligible to apply, with a reasonable expectation of receiving some form of assistance;

- how to make an enquiry and application for assistance, including any application forms;

- any help or advice available with making an application through home improvement agencies or partners in any loan scheme operating locally;

- approval and payment processes;

- what happens if they start work before approval;

- any conditions that apply;

- how their contribution (if any) or loan repayments will be calculated and when the loan repayment would be required;

- how to resolve problems during and after completion of works;

- target timescales for operating different parts of the process, such as times taken for assessment, survey, approval and construction stages;

- assistance that may be available instead of or in addition to a grant or loan;

- advice, assistance and advocacy services that may be available where support is required;

- provisions for dealing with requests for assistance that fall outside the policy and the complaints procedure.

Authorities should ensure the information provided is up-to-date, accessible and easily understood for example, by people with learning and communication difficulties, or by those whose first language is not English.

Public information and self-assessment

Foundations (the National Body for Home Improvement Agencies in England) host the AdaptMyHome.org.uk website which includes general information about DFG and home adaptations.

It also includes a guided self-assessment that help people to consider:

- whether they would benefit from making adaptations to their home;

- if they might be eligible to apply for a DFG;

- whether they might be better to consider moving to somewhere more suitable; and

- their estimated contribution towards the costs through means testing.

By entering their postcode they can also find the contact details of their local authority or forward the details of their self-assessment.

Local authorities are able to register and update their details.

Dealing with complaints

4.20 The right to complain about adaptations services should be clearly set out on each authority’s website and other media and made available to enquirers when they first make contact. This information should detail who they should complain to and the processes and timescales involved. For cases that cannot be resolved through the normal complaints procedure, contact details for the Local Government and Social Care Ombudsman should also be provided.

4.21 Authorities should also have a contingency fund to pay for remedies to be swiftly carried out when adaptations have gone wrong. People in these circumstances should not be put in a queue to wait for a reassessment.

Providing an effective response to enquiries and referrals

4.22 To ensure clients receive a seamless service, on initial enquiry there should be an initial screening process, with agreed criteria, to determine whether an assessment is required for other forms of social care assistance.

4.23 Where the enquiry is received by a social services contact centre, housing needs should be an integral part of any needs assessment. People who do not qualify for social care services may nevertheless be entitled to a DFG.

4.24 Agreed criteria for assessing adaptation needs should be used. This should include criteria to enable an initial level of priority of the case - this can be revised later in the light of additional information or changes of personal circumstances.

4.25 The essential requirements include:

- a means of identifying and prioritising urgent cases;

- other criteria that may assist in setting a priority based on the needs of the client. An example of arbitrary criteria would be a decision to give low priority to people seeking help with bathing problems; and

- a system for checking that a correct decision has been made, for example by feeding back to the client or the referral agency the information which has been logged to ensure that it is correct.

4.26 A written response, or response in another format as appropriate, should be made to every enquiry providing an explanation of the action which is to be taken and the expected time scale. It should make clear who is responsible for each action (including the client if more information is required) and should give a clear point of contact.

4.27 The client should be informed of the next steps, including when they should expect a response and contact details to follow up in the event of delay. The date on the initial enquiry should be regarded as the starting point for a request for assistance for measuring against the target timescales as set out in paragraph 4.16.

4.28 Authorities should also consider introducing a secure online portal where clients can check the progress of their case.

Single point of contact

4.29 The response to referrals or enquiries should identify a single point of contact, who the client can contact for information about their case. Ideally, this contact point should remain the same throughout the process, rather than being transferred, for example, from social services to housing if a DFG has been identified as the appropriate solution.

Preliminary means test for DFG

4.30 The DFG means test is in place to ensure that DFG funding reaches those people who are on the lowest incomes and least able to afford to pay for the adaptations themselves.

4.31 Authorities should consider a preliminary means test for DFG at an early stage. It can be frustrating for both applicants and staff to discover at a late stage that the DFG means test indicates they will receive little or no financial assistance. A preliminary enquiry about resources (e.g. through a self-service online portal such as adaptmyhome.org.uk) can short-circuit these delays and may encourage the disabled person to pursue other solutions.

4.32 More information on the means test can be found in Appendix B at paragraph B98.

Triage and assessment

4.33 Everyone is an individual and one size does not fit all. Assessments should be person centred, and consider the individual views, values and cultural needs of the client. Practitioners in housing, health and social care should work together to help ensure clients feel confident and empowered to manage daily risks, drawing upon clients’ strengths and assets to achieve positive outcomes.

4.34 For disabled children and young people, assessments should take account of their views and those of their parents. Assessments of disabled children should consider the developmental needs of the child and their progress towards maximum independence, the needs of their parents as carers and the needs of other children in the family.

Autism and behaviours that challenge

Where home adaptations are being considered to deal with behaviours that challenge, the family and carers of the disabled person should be highly involved in the assessment discussions and decision making process. It is also good practice to consult with specialist colleagues to fully explore the correct balance between therapeutic interventions and adaptations.

Where behaviours threaten the safety of others living within the household, the grant can be used to reduce the risks to their safety. For instance, where siblings share a bedroom and there is the threat of harm during the night, then creating a separate bedroom can meet this purpose.

Grant could also be used to create a safe space for a person who is likely to injure themselves. This could, for example, include items such as upholstered and washable walls, soft flooring, radiator covers or a television enclosure. See Appendix A for further details on use of capital funding.

Triage

4.35 It is recommended that authorities use a triage system to make an initial assessment of the complexity and urgency of a case. A good triage system will help everyone gain a shared understanding of the likely timescales for delivery. It will also enable the right team with the right skills to properly assess the case. Occupational therapists can be a limited resource, so it makes sense for qualified Trusted Assessors to assess simpler cases, enabling occupational therapists to focus on the most complex cases.

Deciding what is complex and needs occupational therapy input

4.36 To effectively route clients down different pathways, it is important to understand the potential complexity of the case at the outset. A complexity framework for home modification services has been developed in Australia which considers two aspects of complexity:

- Firstly, whether the adaptation is likely to be minor or major, defined by the structural changes required to adapt the home environment rather than cost.

- Secondly, whether the person’s situation is straightforward or complicated – using a range of factors including the nature of the person’s condition, the type of activity the person is wanting to do, and how ready the person is to have their home adapted.

Complexity model with Major/Minor on one axis and Straightforward/Complicated on the other axis. Complex is Major and Complicated Simple is Major and Straightforward or Minor and Complicated

4.37 This model can be adapted to identify the cases where occupational therapy input will be most beneficial. More detail on adopting this approach can be found in the Adaptations without Delay framework published by the Royal College of Occupational Therapists.

Deciding the urgency

4.38 Authorities are recommended to treat cases as urgent in the following circumstances:

- Coming out of hospital and at risk

- Living alone and at risk

- Severe cognitive dysfunction and at risk

- Living with a carer who is elderly or disabled

- Living without heating or hot water and at risk

- Limited life expectancy

4.39 Categorising complexity and urgency at this early stage will set the target timescales for the rest of the process. However, this should be kept under review as circumstances change or if further information is uncovered during the assessment.

Assessment of need

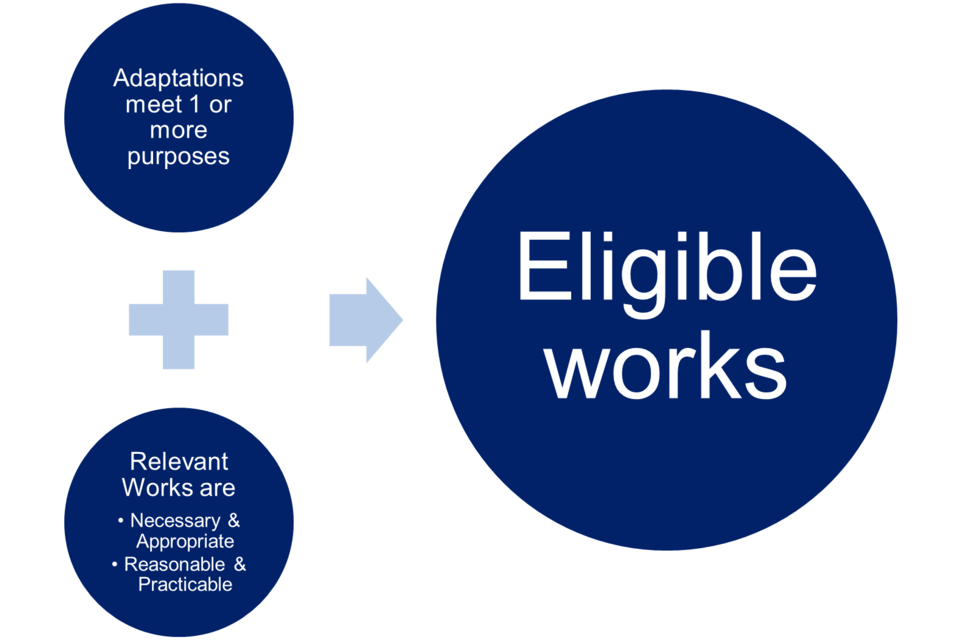

4.40 In the DFG assessment, the authority must identify the client’s needs and what ‘relevant works’ are necessary and appropriate to meet their needs. Further information on legislation around the relevant works and what is necessary and appropriate can be found at Appendix B, paragraph B61. Below are some key principles to consider when identifying the adaptations needed.

- The primary purpose should be to modify a home environment to help restore or enable independent living, privacy, confidence and dignity for individuals and their families.

- The DFG can be used for a wide range of capital works to a home provided it meets the purposes set out in the Housing Grants, Construction and Regeneration Act 1996 (see Appendix B, para B45).

- Authorities should judge each request for adaptations on its merits in accordance with the legislation (see Appendix B) and not seek out reasons to refuse or delay approval.

- The starting point and continuing focus should be the needs experienced and identified by the client and their carers. The process should be one of partnership in which the older or disabled person and carers are the key partners.

- All partners should work to ensure that each adaptation is delivered sensitively, is fit for the purpose identified by the client, their family, or their carers, and within a timeframe that is made explicit at the outset.

- Authorities should consider how best to achieve value for money, taking into account: - how to design adaptations that will meet current and anticipated future needs; and - projected costs of health and social care in the longer term.

- Value for money will not always be achieved by choosing the cheapest option. An adaptation should satisfy the present and anticipated needs of the disabled person even in large and complex adaptations costing above the grant maximum of currently £30,000.

Recycling adaptations and value for money

When considering value for money local authorities should take into account their investment into the long term accessibility of the housing stock in their area.

For example, carrying out the minimum works necessary to adapt a bathroom to meet the functional needs of a disabled person is unlikely to see those adaptations retained at the next change of occupier.

For specialist equipment such as stairlifts, homelifts, hoists and so on, authorities should consider how these items can be reclaimed, refurbished and recycled for use by others who may need them. There are different approaches to consider, including: