Developing pathways for referring patients from secondary care to specialist alcohol treatment

Published 1 June 2018

1. Introduction

Alcohol is a causal factor in more than 60 medical conditions, including circulatory and digestive diseases, liver disease, a number of cancers and depression. In 2016 to 2017, there were 337,113 hospital admissions in England, where an alcohol-related condition was a primary diagnosis. Dependent drinkers are at particularly high risk of alcohol-related ill health.

The Preventing ill health by risky behaviours from alcohol and tobacco: commissioning for quality and innovation (CQUIN) indicator promotes alcohol identification and brief advice (IBA) for people who are not alcohol dependent, but whose drinking increases the risk to their health. IBA is not aimed at dependent drinkers, but the screening process will inevitably identify people in that group.

It is estimated from current CQUIN activity data that up to 5% of inpatients in secondary care might be alcohol dependent. So effective local care pathways will need to be in place to meet the needs of these patients.

Care pathways are about planned journeys through components of treatment and between providers of those components. They are a methodology for mutual decision-making and organising care for a defined group of patients during a particular period. Pathway diagrams, such as the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) alcohol misuse disorders flowchart, are helpful, but pathways should be more than a travel itinerary. Each patient should experience a seamless journey through the treatment pathway.

An alcohol treatment pathway might begin with identifying a patient’s potential dependence from a routine alcohol-use screen. At each step on the journey, the caregiver has to know what treatment is needed and where it can be accessed. Caregivers at each stage of the referral pathway need to be expecting the patient and have all relevant information about them in advance. There needs to be a mutual understanding of what each component of the pathway can do and the capacity there is to provide it.

This guidance focuses on pathways within secondary care and between secondary care and community alcohol treatment services. In particular, it deals with the points where patients’ treatment transfers between service providers and the links with everyone who has a supporting role in the pathway. This includes forecasting need, planning and recorded agreement on actions across the local agencies involved, which is regularly reviewed by everyone. Each organisation involved in the pathway needs to buy into the process and be accountable for the service they provide while working in partnership to create an effective pathway.

2. Important components of the pathway

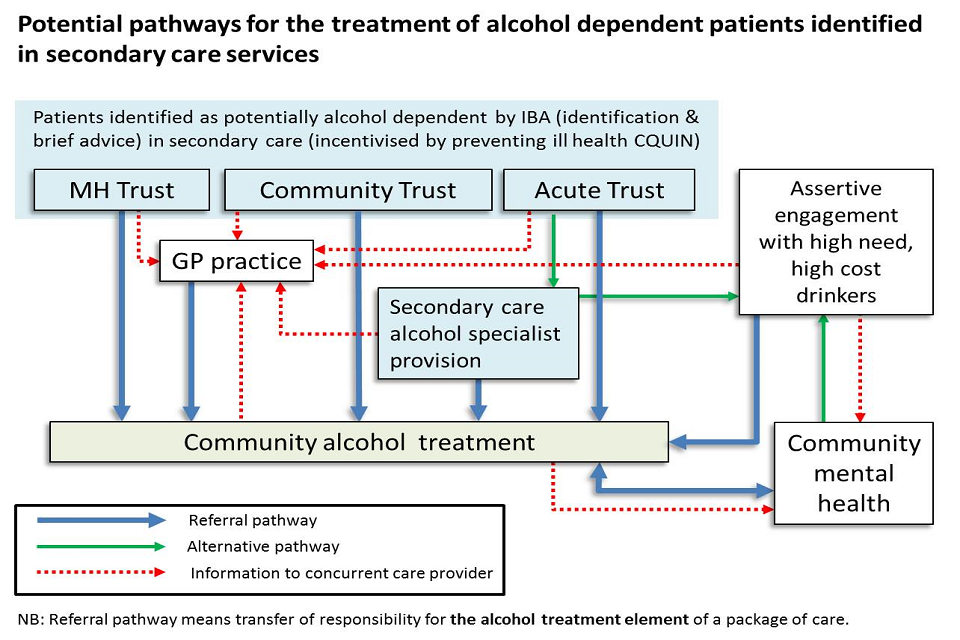

Potential pathways for the treatment of alcohol dependent patients identified in secondary care services

2.1 Identifying potential alcohol dependence in secondary care

Alcohol dependence is a clinical diagnosis characterised by craving, tolerance, and a preoccupation with alcohol, withdrawal and continued drinking despite harmful consequences.

NICE has published guidance that can be used to help identify alcohol dependence, including:

- NICE guidelines and quality standards on preventing alcohol-related harm recommend that all healthcare staff should routinely deliver IBA to patients

- NICE guidelines and Public Health England (PHE) guidance on co-occurring mental health and alcohol and drug misuse recommend that mental health services should screen and assess for alcohol misuse problems

- NICE guidance on alcohol treatment and on co-occurring mental illness and substance misuse promotes proactive engagement with people who have mental ill health and problematic alcohol misuse

Opportunities for identifying alcohol misuse among NHS patients

The national preventing ill health CQUIN incentivises alcohol screening of all adult inpatients and taking the appropriate response, in the community, mental health and acute trusts. For patients whose screening suggests they may be alcohol-dependent, the appropriate response is to refer them for specialist assessment.

Most district general hospitals have specialist alcohol staff that support and train others to give alcohol identification and brief advice.

In some areas, secondary care and community-based services have been developed to manage harm associated with high need high cost (HNHC) drinkers. These are vulnerable, dependent drinkers with complex needs and chaotic lifestyles, and who regularly use emergency services. These services are likely to have dependent drinkers in need of specialist alcohol treatment in their caseload.

Screening tools

For routine alcohol risk assessment with patients, there are effective, easy to use tools to assess their level of health risk from alcohol and possible alcohol dependence. These tools include the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT), or the shortened version, AUDIT-C. Patients scoring 20 or above on the full AUDIT questionnaire, or 11 to 12 on AUDIT-C, should have a specialist alcohol assessment.

The setting for the alcohol assessment depends on the local availability of alcohol specialists, who might be:

- an alcohol specialist nurse or health worker in a hospital alcohol care team or rapid assessment interface and discharge (RAID) service

- a psychiatrist or nurse in the mental health service with suitable competence

- a member of the community alcohol or substance misuse treatment team

- a GP with suitable specialist expertise (not widely available, so not included in detail here)

2.2 Comprehensive alcohol assessment

Secondary care alcohol services provide specialist alcohol care in hospital and liaison into community treatment for dependent drinkers. This care may be based in any of a number of service configurations such as:

- alcohol care teams (ACTs), alcohol specialist nurse (ASN) or alcohol liaison nurses (ALN) services, based in the acute hospital

- community in-reach services delivered by the community alcohol service

- an element of mental health liaison services such as RAID

There is some type of alcohol specialist care provision in around three quarters of district general hospitals, although these teams vary in size, days of operation and the treatment they offer.

In acute trusts where there is secondary care alcohol specialist provision, the most pragmatic referral route for potentially alcohol dependent patients would be to that specialist team. The alcohol specialist can expand on the initial screening and assess the patient’s level of dependence and risk of withdrawal. This may include a comprehensive assessment. The alcohol specialist team can agree on a care plan and start alcohol treatment alongside treatment for the patient’s presenting condition. If the patient is in acute withdrawal then the ACT will be able to support medically assisted withdrawal (MAW).

One of the aims of alcohol specialist teams is to support appropriate discharge and transfer of patients from secondary care to continue their treatment in the community. For clinical safety reasons, some patients should remain in hospital to complete MAW before transferring to community treatment. However it might be possible for others to continue and complete MAW in the community.

Assessing a patient’s suitability to complete MAW in the community should only be done by an alcohol specialist, according to written clinical guidelines based on NICE clinical guidelines CG115 and transfer of care agreements will need to be in place.

2.3 Discharge planning

Where there is no alcohol specialist provision in the hospital, patients whose screening shows they are potentially dependent and those who have been actually diagnosed as a dependent should be referred to the community alcohol treatment service before they are discharged from a hospital. This should happen whether or not they are supported with MAW so that their care is continuous. In some areas, a community service can provide in-reach to the hospital to assess and agree on a care plan for discharge.

Community alcohol treatment

Structured alcohol treatment in the community is appropriate for people with alcohol dependence and for harmful drinkers who need additional help managing their drinking. These services are vital in addressing alcohol dependence and the resulting health harm and emergency service use.

Treatment programmes for harmful drinking and alcohol dependence provided by these services may include:

- medications to achieve safe withdrawal from alcohol or maintain abstinence

- talking therapies for the same goals

- support for continued recovery, such as mutual aid

- help with employment and housing

Local authorities are responsible for providing community alcohol treatment which is usually commissioned from NHS provider trusts or third sector organisations. Community services work with other providers involved in the care and support of their clients, such as GPs, mental health services, assertive engagement teams, housing and Job Centre Plus (JCP).

3. Planning and developing alcohol pathways

NHS and local authority commissioners need to ensure that there is a clear understanding of the processes, capacity to respond and responsibilities involved in all the relevant stages of the above pathway.

3.1 Developing alcohol care pathways

Effective care pathways have clear and comprehensive communication. Dysfunctional care pathways result in bottlenecks, unnecessary attrition and can put patients at risk. It is important that all teams involved in the pathway agree their respective roles and responsibilities. Bringing people together to create this understanding and agreement will require strategic leadership. Local authority public health is probably best placed to provide this.

63% of hospital alcohol services that responded to PHE’s 2018 survey of alcohol care teams say that their role includes the development of alcohol care pathways, so these teams will expect to be involved.

3.2 Anticipating need

Local authorities should provide community alcohol treatment, based on the estimated local need. PHE has produced local estimates of unmet need for alcohol treatment which can be found on the public health dashboard.

Commissioners will also be able to draw on local intelligence to provide a more nuanced assessment of need. For example, they may be aware of particular communities or geographical areas where there are high levels of unmet need.

Increased alcohol screening in healthcare settings results in increased identification of dependent drinkers. National estimates of national alcohol use prevalence in the general adult population indicate that around 75% of adults are drinking at low risk levels that do not pose significant risk to health. 25% drink at levels that present a lifetime risk of ill health and, of these, about 600,000 adults are dependent on alcohol (1.4% of the adult population). Since alcohol misuse increases the likelihood of ill health, this prevalence is probably between 2% and 5% of people admitted to hospital.

PHE is developing a modelling tool to estimate referral traffic to community treatment from alcohol screening initiatives.

When planning and developing local alcohol pathways, commissioners should:

- use the PHE commissioning support pack, social return on investment tool and commissioning tool to help plan effective and cost-effective services

- use data from local hospitals on numbers of dependent drinkers identified via screening to inform planning of local services

- use local hospital admissions data on alcohol-related disorders to inform planning of local services

- be aware that any increase or reduction in screening activity in hospitals is likely to affect referral numbers

- introduce recording measures to keep track of the proportion of dependent drinkers identified at screening, who are lost in transition between specialist assessment; commencing community treatment; and treatment completion

- observe trends in the above proportions

3.3 Referral mechanisms - protocols

Effective referral needs to be active and requires communication between caregivers and the people who need care. Protocols (the agreed processes) for proactive referral between service providers need to be mutually agreed, widely understood and kept up to date. Protocols are vital to avoid unsafe discharges and patients falling through the net between services.

When a patient starts a treatment programme that will need to be completed by another provider, clear protocols are needed to ensure that all parties can manage risk, contribute to the care plan, are clear on the treatment being offered and are able to deliver the required interventions in a timely way.

At each stage of the pathway, every agency involved will need to:

- understand the extent and limitations of the care that other contributing teams can provide, including any exclusion criteria

- understand the time pressures for all concerned and agree on response times (these may differ depending on patient circumstances and need to manage risk)

- agree how to make referrals (for example, letter, email, form, phone call, bleep, integrated care management system), and clarify up-to-date contact details and minimum information requirements

- agree how the patient should be notified of arrangements (for example, letter, email, phone call, text, app), by whom and minimum information the patient should receive

- agree how to share essential patient information (see information sharing section)

- agree how patients who present to mental health services can access timely assessment from an alcohol specialist

NHS commissioners and NHS service providers should work with local authority commissioners and local authority community service providers to draw up joint protocols which clearly describe pathways and joint working agreements. They then should:

- review referral protocols regularly

- ensure that protocols are revised and agreed with all parties and re-issued to primary and secondary care during re-contracting of community treatment providers

- consider a single point of contact for entry into community alcohol treatment

3.4 Overcoming potential barriers - patient information and care coordination

To support patients receiving the right treatment and care in a timely way, it is vital that all parties contributing to treatment are completely aware of any relevant details about assessments and treatment patients have had or are receiving.

Lack of information or late information sharing causes friction in referral pathways, slows down the process and risks losing recovery momentum and increasing treatment failure. Lack of clinical information, particularly when transferring responsibility for the alcohol treatment element of a care package between providers, can reduce patient safety and creates barriers to effective treatment. A number of serious case reviews have identified poor communication between agencies as a significant factor.

If the patient’s referral is accompanied by assessment and treatment information, the receiving team can update their care plan appropriately, taking into account any changes in risk factors. To help this process it might be helpful to have a common comprehensive alcohol assessment framework used by all local agencies. This can help alcohol specialists to have confidence in each-others’ assessments. A shared case management IT system could also help local care coordination.

The Health and Social Care (Safety and Quality) Act 2015, section 251B Duty to share information, indicates that health or adult social care providers must ensure that relevant information about an individual is disclosed to any other relevant health or adult social care commissioner or provider with whom they communicate about the individual. This is so they consider if the disclosure is (a) likely to facilitate the provision of health services or adult social care to the individual and (b) in the individual’s best interests.

It is important to share relevant clinical information between NHS and community treatment services, where it is in the patient’s best interests and with their consent. However, constraints apply and safeguards must be in place. How this can be achieved and the constraints that apply are covered in To share or not to share? The Information Governance Review and the NICE clinical guideline Patient experience in adult NHS services: improving the experience of care for people using adult NHS services.

Local authority commissioners should:

- agree protocols for information sharing and patient consent in a data-sharing agreement

- agree and implement a common framework for comprehensive alcohol assessment to be used by all local partners

3.5 Overcoming potential barriers - timing

Embarking on an alcohol treatment journey is usually a major undertaking for the drinker. People choose to do so for many reasons, but often drinkers cite a particular event as the trigger. Losing momentum in a treatment journey once it has begun, through a temporary shortfall in support, poses a major relapse risk and also risks losing a lot of the benefit from the work already done.

Most community alcohol treatment is only open on weekdays. So weekends limit when referred patients can be assessed. There are some services which offer extended opening hours and open access, so it is important that these services’ opening times are clearly documented.

Public health commissioners can use service specifications to minimise constraints on patient referral from secondary care to community alcohol services. They should also ensure that there are minimal gaps in support for drinkers who have started a treatment journey and who may also have long term conditions due to their alcohol dependence. Public health commissioners are also probably well-placed to ensure that primary and secondary care providers understand any limitations on receiving patients into community treatment from the NHS and to agree how best to minimise gaps in support.

NHS and local authority commissioners should work with providers to:

- ensure pathways form an integral part of joint NHS and local authority service planning so that care across hospital and community services is properly integrated

- plan local systems together, so that the local system includes referral options to enable clinical providers to exercise their duty of care to provide safe and appropriate discharge and continuity of care (for example, options for continuation of MAW in the community)

3.6 Overcoming potential barriers - attrition

There is a disparity between the number of patients who are referred to community alcohol treatment and the number who end up receiving treatment. There are many reasons why this can be the case. For instance:

- some alcohol dependent people choose not to attend community treatment

- referral is not sufficiently active (for example the patient is only provided with contact details and is expected to self-refer) or information is out of date

- periods with no treatment support are too long, so patients lose momentum, relapse and lose resolve

- substance misuse services with a strong drug treatment culture may not feel accessible to people who are alcohol dependent

- services may not be geographically accessible

- services may not be culturally accessible for particular groups of alcohol dependent patients

- some vulnerable drinkers with complex needs and chaotic lifestyles find it difficult to comply with criteria set by some services for commencing treatment or may need proactive engagement to stay in treatment

- there may be no access or restricted access to evidence based interventions, such as planned, residential or in-patient MAW (NICE clinical guidance describes the interventions that should be available to alcohol dependent adults)

Attrition between services is expected but is often avoidable, and it is important that plans are put in place to prevent the probability of patients dropping out of the pathway.

NHS commissioners and NHS service providers should work with local authority commissioners and local authority community service providers to:

- work with partners to ensure active referral in line with clearly defined and agreed pathways

- engage assertively with the neediest clients

- ensure proactive follow-up of those who drop out of treatment

- engage with family members and carers to provide advice on how to best support their loved one

- make use of peer support to encourage engagement and demonstrate visible recovery

- use technology (such as texts or apps) to ensure that patients have the right information at the right time

- provide routes into community services, which consider the specific needs of alcohol users which may differ from those of drug users

- ensure commissioning of services provides access and capacity for each treatment component to meet assessed levels of treatment need

3.7 Information for supporting services

For most patients referred to alcohol treatment from secondary care, the alcohol treatment will only be one element of their care package. Many will be receiving ongoing treatment for mental or chronic physical ill health that originally brought them into contact with the NHS. Some will be in contact with other support services. For these services, information about their clients’ alcohol treatment engagement may be relevant. So it will be important to ensure that other supporting services are provided, subject to consent, with appropriate feedback about their patients’ alcohol misuse issues.

These services may include:

- community mental health

- IAPT (improving access to psychological therapies)

- assertive engagement services

- primary care

- other frontline agencies will also find it useful to be aware that patients are receiving treatment (for example, JCP, housing, homelessness support, criminal justice and adult and children’s social care)

Primary care is central to a patient’s healthcare in the community and information about a behaviour that poses risks as wide-ranging as alcohol misuse is relevant to those caring for patient’s general health and wellbeing. It would, therefore, be valid to include information about non-dependent risky alcohol use (increasing and higher risk) as well as referral for dependence in any feedback mechanisms between secondary and primary care. Community treatment services should feedback information to primary care and, if appropriate, assertive engagement services.

Where hospitals do not have alcohol specialist staff, clinical leads should make contact with the local authority public health teams servicing their area to find out about alcohol treatment providers.

4. Patients with co-existing mental health and alcohol problems

Because of the strong correlation between mental ill health and alcohol misuse, many people fall into this patient group. Patients in mental health services need timely access to specialist alcohol assessment and care, provided in the most appropriate setting, in a mental health service or a community alcohol service.

If patients fall between services, there can be a significant risk. For example, The National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide found that for patients who died by suicide, 68% had a history of self-harm and 45% had a history of alcohol misuse. Some areas recommend directing patients who self-harm to open access services. However, if the patient is also alcohol dependent and fails to attend community alcohol treatment, it is important that the referral is chased up and they are proactively followed up by the alcohol service. Rather than requiring drinkers to be self-motivated prior to entering treatment, patients should be engaged based on clinical risk and need.

This guidance does not cover the detail of dealing with patients with co-existing mental health and alcohol dependence, for fuller guidance see PHE’s guidance on commissioning and providing better care for people with co-occurring mental health, and alcohol and drug use conditions.

5. Further guidance

The following guidance documents that will be helpful in developing alcohol care pathways.

Alcohol-use disorders: diagnosis and management quality standard

Alcohol-use disorders: diagnosis and management of physical complications - clinical guideline

The National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide - Manchester 2017

Better care for people with co-occurring mental health and alcohol/drug use conditions

Multi-morbidity: clinical assessment and management - NICE guideline

Multi-morbidity - NICE Quality Standard

Models of delivery for stop smoking services: options and evidence