Definition of trees and woodland

Updated 11 July 2025

Applies to England

1. Purpose

This page outlines the Forestry Commission’s interpretation of “tree” and “woodland”. These are important words to understand to help explain our approach to:

-

what tree felling activities engage the felling licence regime under the Forestry Act 1967 (“the Act”) and are therefore subject to the requirement for a felling licence issued by us

-

what constitutes afforestation, deforestation and other forestry related works for the purposes of the Environmental Impact Assessment (Forestry) (England and Wales) Regulations 1999 (“the forestry EIA regulations”), under which we are the appropriate forestry body in England for making decisions

We have considered a range of definitions and interpretations from different sources in this page, including other UK legislation, European regulation, case law in the English courts, and authoritative forestry publications.

The interpretation we adopt does not undermine any of the definitions adopted elsewhere and we refer to many of these sources on this page. Our interpretation of “tree” and “woodland” is intended to apply only to the forestry EIA regulations and the Act.

This content is not intended to apply to any other regimes, schemes or regulations. This includes other Forestry Commission administered regulations and grant schemes, planning and development regimes and legislation, or anything else.

We use the terms “woodland” and “forest” interchangeably in this page.

2. Background

Case law exists on the definition of a tree outside of the Act[footnote 1].

There is not a statutory definition of “trees” or “woodland” (or “forest”) in either the Act or the Forestry Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) regulations. However, both legal regimes rely on an understanding of what trees and woodland are.

Trees

It is important to understand the term “tree” in relation to the Act, and when a felling licence is required. The word determines the overall scope of the felling licence regime, which applies to all “growing trees” unless an exemption applies.

Woodlands

It is important to understand the terms “woodland” and “forest” in relation to the meaning of “afforestation” and “deforestation” under the forestry EIA regulations, and the associated Forestry Commission guidance documents.

The forestry EIA regulations provide the following explanation of afforestation and deforestation:

-

afforestation means the conversion of a non-woodland land use, for example agriculture, into woodland or forest by means of planting, or facilitating natural colonisation (self-sowing) of trees to form woodland cover

-

deforestation means the removal of woodland cover for conversion to another land use. This can include proposals for the removal of short rotation forestry, short rotation coppice, Christmas tree plantations and energy crops[footnote 2]

The terms “woodland” and “forest” are therefore important when we assess forestry EIA proposals.

We acknowledge we have applied, and continue to apply different interpretations of the terms to other areas of our work, for example within the eligibility criteria for various grant schemes.

You can find a selection of the existing definitions in the tables in section 6.

We know that no single interpretation of “tree” or “woodland” (or “forest”) will be able to cover all tree species or all examples of woodland habitats. We must consider the context and make decisions on a case-by-case basis. However, we have brought together existing definitions to allow us to be consistent in our decision making.

This page is therefore a guide to interpreting the terms, rather than an exhaustive and exclusive definition.

3. What is a tree?

3.1 Interpretation

In England, growing trees are subject to felling controls under the Act. It is an offence to fell growing trees without a felling licence where one is needed.

We consider the term “growing” to be synonymous with the word “living”. Ancient and veteran trees, for example, while not technically in the “growth” phase of their life cycles, are still living organisms providing distinct ecological and cultural functions.

At its most basic biological function, “growth” can simply imply cell division. So long as new cell division is taking place, new leaves may flush in spring, new shoots may develop, new cuts may heal and new flowers and/or seeds may grow. We take these as a non-exhaustive list of indicators of a “growing” tree.

A tree does not need to be healthy to be growing. The word “growing” does not imply the creation of additional usable timber to the main stem of the tree.

Under the Tree Preservation Order legislation, the courts have considered the definition of a “tree” (see Section 6.1). But the Act does not define what a tree is in relation to felling licences.

Other legislation defines “hedgerow trees” and “trees outside woodland”. But these are not directly applicable to the term “tree” used in the Act[footnote 3].

We have considered this statute and case law (see Section 6.1), and will typically apply the following interpretation:

To be considered a tree, the plant must have at least one woody stem and be expected to achieve a height of at least 5 metres.

If an individual specimen has not reached 5m in its present location, but the plant species typically meets this definition, we will still consider it a tree.

Reasons for not reaching 5m might include:

- young age

- site management

- suppression due to difficult growing conditions

Difficult growing conditions might include:

- wind-swept or exposed locations (cliff tops, dunes, or uplands)

- sites with an elevated water table (for example, with waterlogging issues)

- sites under significant grazing pressure

If a plant species meets this definition and is not an “exempt” species (see Section 3.2), we will likely consider it a tree. So, unless an exemption applies, you will need a felling licence to fell (cut down, coppice, or destroy) it.

Our interpretation of a “tree” applies to all trees, including woodland trees, hedgerow trees and trees outside woodland.

For further information on the current tree felling controls, see Tree felling: getting permission.

3.2 Non-tree species exemption

There are some plant species that may exhibit tree like qualities in certain growing conditions, but which we do not consider to be trees, even if they meet the interpretation above.

You do not need a felling licence to cut down the following species:

- gorse (Ulex europeaus)

- rhododendron (Rhododendron spp.)

- sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides)

- laurel (all members of the Lauraceae family)

- cherry laurel (Prunus laurocerasus)

- miscanthus (Miscanthus spp.)

- osier (Salix viminalis)

- palm trees (various)

- bamboo (all members of the Bambusoideae subfamily)

4. What is woodland?

4.1 Interpretation

Many definitions of the term “woodland” exist (see Section 6.3). Broadly, these definitions discuss:

- minimum area

- minimum or average width

- (potential) canopy cover

- tree height

- minimum tree stocking density

- proportion and composition of open space

We will typically apply the following interpretation. To be considered “woodland”, the site must meet all the following:

- a minimum area of 0.5ha

- a minimum width of 20m

- a potential tree canopy cover of at least 20%

- a canopy consisting of specimens that meet the definition of trees (see Section 3)

We will consider all land types and/or uses, including for example wood pasture and parkland, as “woodland” where it meets this definition and is considered permanent.

However, we recognise that the management required in these habitats is likely to be significantly different.

4.2 Canopy cover

“Canopy cover” is the area covered by the branches and leaves of a tree when viewed from above. A typical woodland provides anywhere between 20% and 100% canopy cover.

To meet our interpretation of “woodland”, trees must provide, or have the potential to provide (for example, in the scenario of a newly planted woodland) at least 20% canopy cover.

To achieve a minimum of 20% canopy cover, there will normally need to be a stocking density of 100 stems per hectare, evenly spaced. This figure may change depending on species composition, but we take 100 stems per hectare as a starting presumption.

Cricket bat willow, for example, can be expected to achieve 20% canopy cover when planted at 100 stems per hectare (for example, in a grid pattern 10m by 10m apart). Other species, however, will achieve 20% canopy cover at a lower, or higher, planting density.

See Section 5: Woodland management scenarios and our advice on canopy cover in relation to tree density in woodland settings.

If you are unsure whether the trees on your land will achieve 20% canopy cover, contact your local Forestry Commission Woodland Officer. They will be able to advise you if we consider the site woodland or not.

You can find a full list of the Forestry Commission’s Woodland Officers and Area teams at Office access and opening times.

4.3 Forest and woodland inventories

Woodland inventories help confirm the presence and extent of woodland and the long-term presence of woodland cover. We use them as a guide, in conjunction with other evidence such as the Priority Habitats inventory, to help decide if a site should be considered woodland for regulatory purposes[footnote 4].

These include:

1). The National Forest Inventory (NFI) records size, distribution, composition and condition of our current forest and woodland cover. It contains several sub-divisions. These include the woodland category and the “assumed woodland” category, which can be used to identify newly planted woodland with the potential to achieve 20% canopy cover. It is maintained by Forest Research.

2). The Ancient Woodland Inventory records the presence of ancient woodland, ancient wood pasture and parkland. It is maintained by Natural England.

Both inventories have established methodologies for reviewing and determining if land is best described as woodland[footnote 5]. However, these inventories do not provide definitive proof of the presence of woodland, or an absence of woodland, on the site at any given time. Because of the natural cycles and/or management cycles that occur in woodland, an area might appear as woodland on an inventory where it is not currently covered by trees.

Some areas will not have trees on them for short periods of time. Felling and/or restocking activity may have recently taken place. There may be ‘scrubby vegetation’, where low woody growth dominates a likely woodland site (for example, a young broadleaf woodland). Tree cover may have historically been at a higher level than it is today.

Similarly, land which was not previously woodland may have developed into woodland through natural or human processes.

Additionally, there is a delay between changes on the ground due to natural or human-initiated processes, and what is reflected in the latest iteration of an inventory.

There may also be exceptions. An inventory might show a site as woodland where we would not consider it as such. So, we use inventories as a guide. They offer a useful starting presumption that woodland exists (or does not exist) on a given site. We will presume land listed as woodland on an inventory is woodland unless there is sufficient evidence to the contrary.

The interpretations we adopt are not intended to undermine or erode the definitions adopted in inventories in any way.

We also use satellite and aerial imagery to help decide whether the land is woodland. This imagery is particularly helpful as it offers both a recent view of the landscape from above and a series of historic views over time for comparison.

4.4 Open spaces in woodland

Open spaces are a vital part of the internal structure of a well-managed woodland. Breaks in canopy cover can include:

- rides, glades, tracks and roads, utility wayleaves, and rights of way

- riparian zones and small water bodies

- buffers around historic environment features

- boundary features (fences and walls)

- open space around ancient and/or veteran trees

- areas important for non-woodland habitats or organic rich soils (peat)

Open spaces allow light to filter through, which supports ground flora, woodland fauna, and helps the understory of the woodland develop. In turn, this will:

- improve the internal structural diversity of the woodland

- create additional internal woodland habitats

- improve the overall woodland condition

We will consider appropriately scaled open space as part of the woodland area.

The Environmental Targets regulations define open space as “areas of integral open space within the boundary of such an area of trees, each of which is less than 0.5 hectares”[footnote 6].

The NFI defines open space as “any open area that is [up to] 20m wide and 0.5ha in extent and is completely surrounded by woodland”[footnote 7].

For woodland to be in favourable condition, the NFI allows for between 10% to 25% open space in woodland areas over 10ha, and up to 10% open space in woodland areas up to 10ha.

Building on the above definitions, our interpretation is that in larger woodland areas (over 10ha), individual areas of open space over 0.5ha can be acceptable where there is a specific purpose, for example as a deer management lawn. Areas of open space contribute significantly to the management needs and ecological function of the woodland and will be accepted as such, provided they are clearly used and managed in a way that supports the woodland management objectives and broader functions of the woodland. However, the cumulative area of open spaces within a large woodland should remain proportionate (10% to 25%) to the overall woodland area.

In smaller woodlands (less than 10ha), individual areas of open space should not generally exceed 0.5ha in size. We will presume that areas of open space in woodland that meet the criteria above are part of the woodland unless there is sufficient evidence to the contrary.

Open space should sit within the boundaries (inside) of the woodland area. Certain types of open space, such as glades, rides, and trackways may provide an access route into the woodland from its boundary. However, other than these access points, open space features should normally be enclosed by woodland.

Open space should support the function of its parent woodland habitat. The open space must function to complement and enhance the woodland habitat, for example, by providing woodland edge habitat, linear access, or buffers to important features.

As a guide, you should maintain a margin of at least 20m of open ground around significant historic environment features. But you should consider the setting as well as the individual feature[footnote 8].

4.5 Functional and non-functional open space

Functional open space

Some intervening features create open space where natural regeneration and/or planting of trees may be possible. As these areas support the function and management of the woodland, we consider the following features part of the woodland area:

- unsurfaced tracks and paths

- temporary features such as unsurfaced lay-bys, and timber stacking areas,

- managed rides and glades

- areas of clear fell

Other kinds of intervening features create areas of open space where regeneration and/or planting of trees is not likely. However, because they interact with the function of the woodland, and/or are a natural component of the landscape, we can consider these features part of the woodland area, subject to their scale and proportion in relation to the woodland area:

- rocky outcrops

- small water bodies

- open habitat managed for the conservation and enhancement of biodiversity

- historic environment features

- boundary features

Non-functional open space

Some intervening features that create open space do not contribute to the function or management of the woodland, and we do not consider these features part of the woodland area. For example:

- public highways

- railways

- rivers (where the gap in the woodland is 20m or more) and lakes

- buildings

- utility wayleaves (where the gap in the woodland is 20m or more)

4.6 Woodland and the forestry EIA regulations

In England, afforestation and deforestation are governed by the forestry EIA regulations.

If a project (either afforestation or deforestation) is likely to have a significant effect on the environment, you must seek the Forestry Commission’s ‘stage 2’ EIA consent before carrying out any works.

If you are unsure if you need EIA consent, you can apply for a ‘stage 1’ EIA decision. We will then tell you if you need to apply for EIA consent. In the following sections, we discuss some notable settings that we consider woodland. This will give you a better understanding of when the forestry EIA regulations apply.

4.7 Short rotation forestry

Short rotation forestry (SRF) uses a variety of fast-growing tree species to produce biomass or timber.

These can include birch or cricket bat willow. If left to reach maturity, many of these species will achieve 20% canopy cover. Cricket bat willow, for example, will achieve 20% canopy cover in a grid pattern at 10m by 10m spacing.

For forestry EIA regulations, we view SRF plantations as woodland. This position is also taken within The UK Forestry Standard (UKFS)[footnote 9].

You will need a felling licence to harvest SRF trees once they reach 8cm in diameter when measured at 1.3m off the ground (unless an exemption applies).

4.8 Short rotation coppice and energy crops

Short rotation coppice (SRC) consists of woody, perennial crops, the rootstock or stools of which remain in the ground after harvesting, with new shoots emerging in the following season[footnote 10].

These, alongside energy crop plantations, tend to include species like alder, birch, hazel, ash, lime, sweet chestnut, sycamore, willow, hybrid poplars and hornbeam[footnote 11]. These species will typically achieve 5m in height and 20% canopy cover if left to reach maturity.

For forestry EIA regulations, we view SRC and energy crops as woodland[footnote 12].

You are unlikely to need a felling licence for most well managed SRC and energy crops. This is because they will be harvested before they reach a significant size. However, you may need one to fell an over mature crop.

4.9 Christmas trees

Christmas tree plantations produce a small range of recognised conifer species. These trees would typically reach 5m in height (and 20% canopy cover) if left to reach maturity.

For forestry EIA regulations, we view Christmas tree plantations as woodland. This position is also taken in UKFS[footnote 13].

A felling licence is normally not required for well managed Christmas trees. This is because most Christmas trees are harvested before they reach 8cm in diameter when measured at 1.3m off the ground. However, a felling licence will be required if some Christmas trees, or entire plantations, are left to grow as large specimens.

4.10 Agroforestry

There are 2 main categories of agroforestry: ‘silvo-arable’ and ‘silvo-pastoral’ (see Section 5.1 for further explanation).

From a regulatory perspective, agroforestry is not widely recognised. So, depending on the project, it may be governed by forestry regulations, other regulations, or none.

You need to know when an agroforestry project counts as “woodland”. In addition to the above criteria for a woodland, we set out some examples in Section 5.1.

Even if we do not view an agroforestry project as woodland, you may still need a licence to fell the growing trees. For further information on the current tree felling controls, see Tree felling: getting permission.

4.11 Native woodland on heathland

Heathland, as well as deciduous woodland, is a priority habitat in England[footnote 14].

The government’s open habitat policy allows for the removal of trees and woodland, where appropriate, to restore priority open habitats[footnote 15]. See Section 5.6 for further explanation.

It is possible for trees and woodland to co-exist with heathland on a heathland site. Likewise, woodland can have heathland elements. However, we will only consider the site woodland if it meets our interpretation above.

It is not unusual for trees to be naturally re-seeding on the site, even if the site is well grazed. If the self-seeded plants are small enough that either manual pulling or grazing can control them, we will not normally consider it (immature) woodland.

4.12 Orchards

Orchards contain fruit-producing and nut-producing trees. Because it is an agricultural activity, different sets of rules can govern their management.

Planting

If you are planting an orchard with species likely to reach 5m in height and 20% canopy cover, we will view the plants as trees.

If the site is larger than 0.5ha in size, we will view it as woodland. You need to consider if you need consent from the Forestry Commission under the forestry EIA regulations relating to afforestation.

If the plants are unlikely to reach 5m in height (for example dwarf stock), we will not view them as trees, and accordingly we will not view the site as woodland. But, as an agricultural activity, you may still need to consult Natural England on The Environmental Impact Assessment (Agriculture) (England) (No. 2) Regulations 2006 (“the agriculture EIA regulations”)[footnote 16].

Removal

Under the Act, fruit trees or trees standing in an orchard, are exempt from the need for a felling licence.

Orchards larger than 0.5ha in size (with trees that have the potential to reach 5m and 20% canopy cover) are interpreted to be woodland for the purposes of the forestry EIA regulations. If you plan to remove an orchard of this size, you may need to consult the Forestry Commission on the forestry EIA regulations relating to deforestation.

If the orchard you plan to remove is not defined as woodland, you may need to contact Natural England regarding the agriculture EIA regulations.

If in doubt, the Forestry Commission and Natural England will be able to help you determine which set of rules govern your orchard project.

5. Woodland management scenarios and our advice

5.1 Agroforestry and woodland cover

Agroforestry is becoming a popular option for landowners. Here are some examples of agroforestry projects and whether we consider them woodland or not.

A stand of mixed conifer and broadleaf trees.

Here we see groups of trees totalling at least 0.5ha in area, with a width greater than 20m. The trees have reached 5m in height. The stand has achieved more than 20% canopy cover.

This is woodland, even if it is grazed or used for food production.

5.2 Silvo-arable

Two rows of trees running parallel across an arable field with a tractor driving between them.

In silvo-arable systems, trees are planted across the site in rows. This creates cropping alleys.

While high numbers of trees may be planted, it is unlikely that they will achieve 20% canopy cover on the site. The rows of trees are narrow, spaced widely apart, and thus unlikely to reach a minimum width of 20m.

This is not considered woodland.

5.3 Shelterbelts: pastoral and arable

A field containing livestock with several rows of trees on one side.

An arable field with several rows of trees on one side.

Shelterbelts on arable or pastoral land that are at least 20m in width are likely to meet our interpretation of woodland. This is because they are typically sufficient in size, width (at the narrowest point) and planting density to meet our criteria. However, “belts” made up of a single row of trees are unlikely to be interpreted as woodland.

5.4 Silvo-pastoral: low density

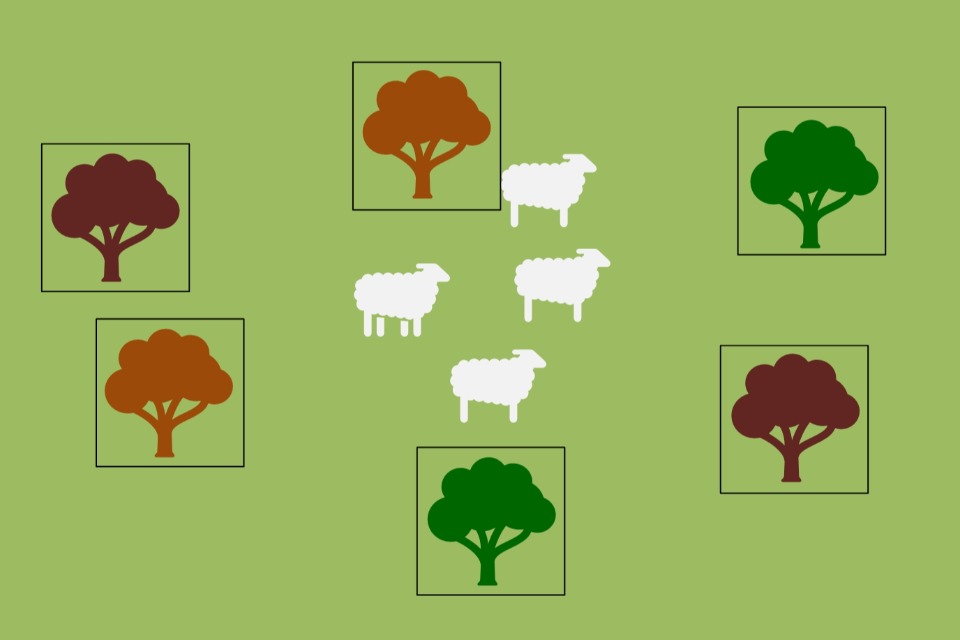

A field containing livestock and scattered individual trees.

Low density wood pasture and/or parkland tree cover is a typical silvo-pastoral agroforestry setting. If the trees grow at low density, they are unlikely to achieve 20% canopy cover.

We typically do not consider this woodland.

5.5 Silvo-pastoral: higher density

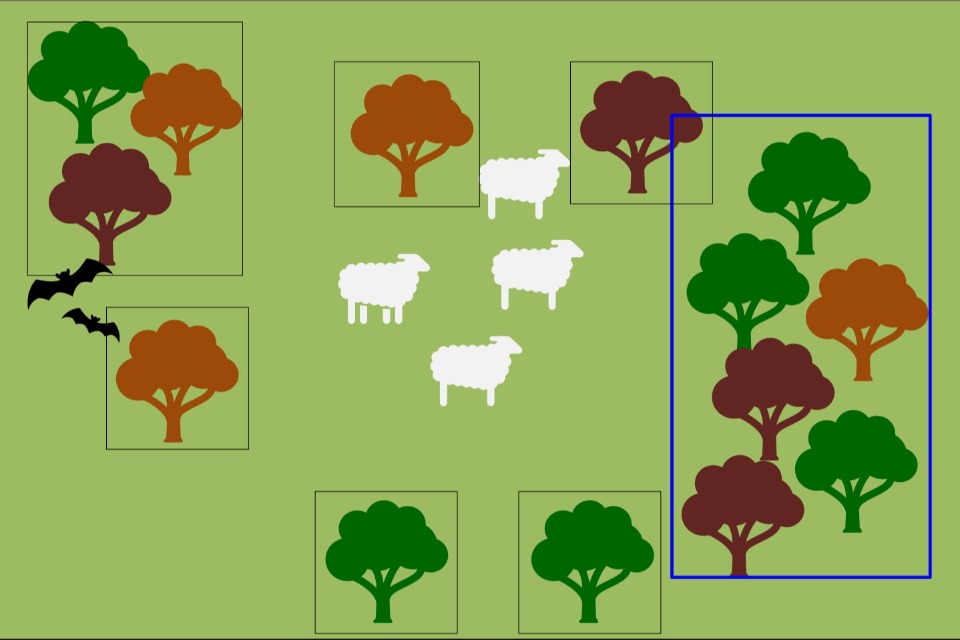

A field containing livestock, individual trees, and groups of trees. A blue box is drawn around a larger group of trees.

Medium density wood pasture is a typical silvo-pastoral agroforestry setting. The trees grow at variable spacing and may be dense enough to achieve 20% canopy cover, either across the site, or in specific areas (as shown by the blue box).

If the dense patch is more than 0.5ha in size and 20m in width, we will consider it woodland.

5.6 Reducing tree cover for habitat restoration

If you have a woodland site and want to reduce tree cover for priority habitat restoration, the remaining trees could still be considered woodland.

The following scenarios set out what would (and what would not) be considered woodland after felling.

Initial site (before felling):

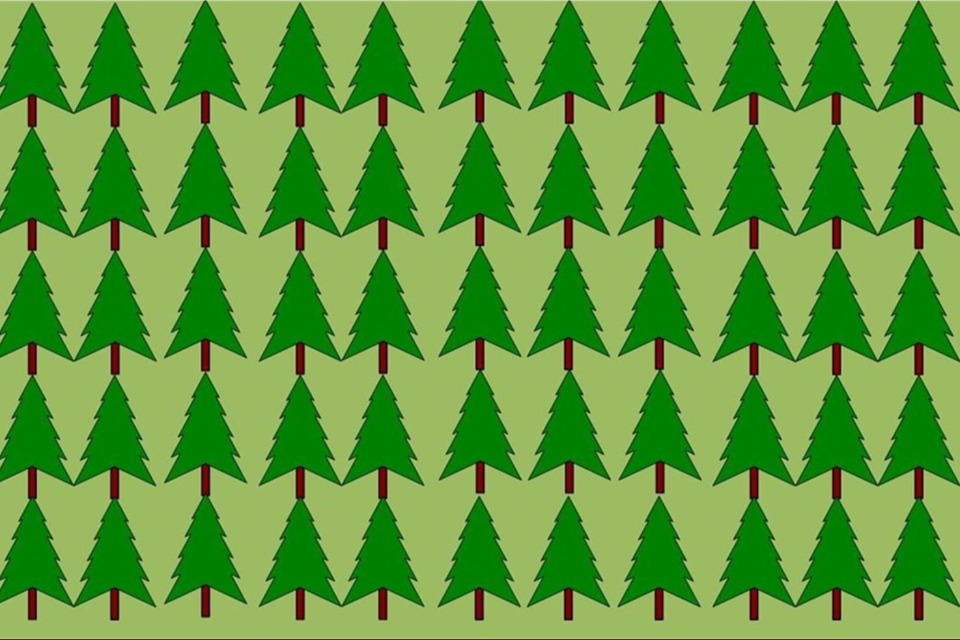

A dense stand of trees with only little space between them.

Woodland covers the whole site. The proposal will remove trees to restore ‘open’ habitat in the following scenarios.

Scenario 1: Restoration (or creation) of wood pasture or open habitat but with retention of scattered trees

A stand of trees with space between them.

After felling, enough trees have been kept across the site to maintain 20% canopy cover.

This is woodland.

No forestry EIA is required, as the project does not amount to deforestation.

A felling licence will likely be required.

Scenario 2: Creation of open habitat and retained area(s) of trees

A dense stand of trees contained within one corner of a field.

After felling, most trees have been cleared. But enough trees are retained in an area of the site over 0.5ha. The retained area has a stocking density to achieve 20% canopy cover.

The retained area will count as woodland. The cleared area, however, will not.

A ‘stage 2’ EIA consent may be required if the project is likely to have a significant effect on the environment, or be subject to enforcement proceedings if no consent was in place where it was needed.

A felling licence will likely be required.

Scenario 3: Creation of open habitat with occasional tree retention

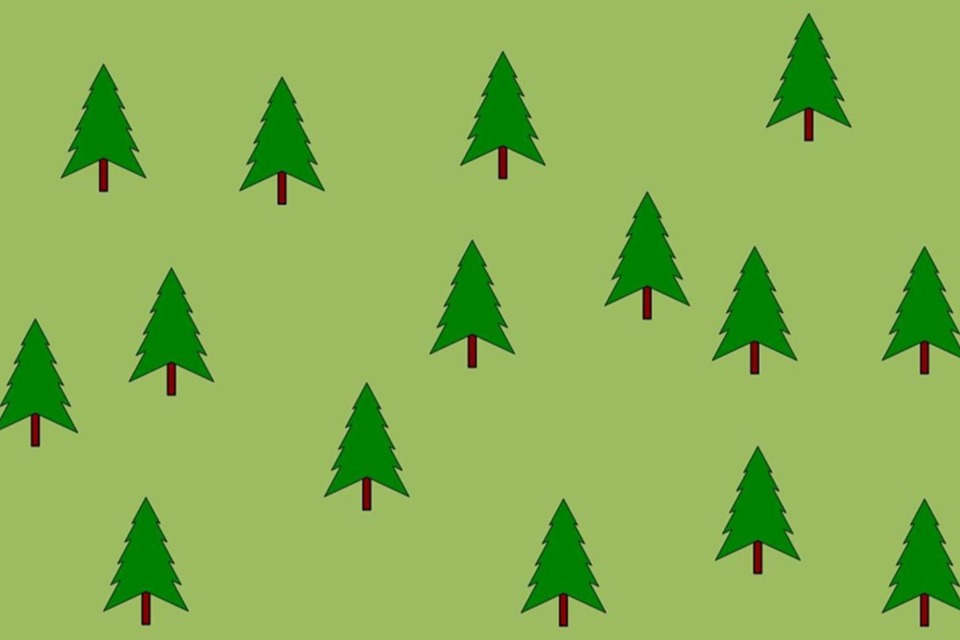

A field containing scattered individual trees.

After felling, some scattered trees have been kept. But not enough to achieve 20% canopy cover across the site.

The whole site is no longer woodland.

A ‘stage 2’ EIA consent may be required if the project is likely to have a significant effect on the environment, or subject to enforcement proceedings if no consent was in place.

A felling licence will likely be required.

6. Source definitions

6.1 Case law: trees

Under the Tree Preservation Order legislation, the courts have considered the definition of a “tree”.

In Bullock v Secretary of State for the Environment and another [1980] 1 EGLR 140 at 142 the High Court ruled that:

Bushes and scrub nobody I suppose would call “trees,” nor indeed shrubs, but it seems to me that anything which ordinarily one would call a tree is a “tree

and that

what grows in a coppice generally speaking would be trees[footnote 17]

More recently, in Distinctive Properties (Ascot) Limited v Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government and another [2015] EWCA Civ 1250 at paragraph 42, the Court of Appeal held that:

…I am not at all sure that this court is required to make a definitive pronouncement as to whether a seedling is a tree. It is not in dispute that a seed is not but that a sapling is…

…I would accept the approach adopted by Cranston J in Palm Developments, namely that a tree is to be so regarded at all stages of its life, subject to the exclusion of a mere seed. A seedling would therefore fall within the statutory term, certainly once it was capable of being identified as of a species which normally takes the form of a tree…

…If the “plant” is of a tree species, I can see no reason why it should be excluded from the meaning of the word “tree”…[footnote 18]

While the Forestry Commission acknowledges that this case law does not set legal precedent in relation to the Act or the forestry EIA regulations, it has been considered alongside other sources in forming the interpretations set out in this document.

The Oxford English Dictionary definition of a tree is:

A woody perennial plant consisting of a trunk and branches, that can grow to a considerable height.[footnote 19]

We have considered these sources of authority and sought to apply them in a practical manner in our own interpretation set out in Section 3.1.

6.2 National Forest Inventory: A starting point

The National Forest Inventory programme monitors woodland and trees in Great Britain.

It includes the most in-depth survey carried out on Britain’s woodland and trees to date. It is a key tool for developing our policies and guidance around sustainable woodland management.

The NFI meets international standards, which means we can use it for international comparisons of tree cover[footnote 20].

Furthermore, the NFI measures the status of the Forestry Commission’s statutory tree canopy cover targets[footnote 21].

The NFI describes a minimum area of 0.5 hectares and a minimum width of 20 metres in its definition. This is consistent with other definitions used in the UK (see Section 6.3). However, it does not consider tree height. Other definitions agree that tree stems should have the potential to reach 5m in normal growing conditions.

As mentioned, we use the NFI as a guide. While it is a good starting point for understanding where woodland exists, it might not accurately reflect current land use.

For further information on the NFI, see National Forest Inventory - Forest Research

6.3 Other definitions

There are many existing definitions of woodland in the UK. We consider each of these sources of authority in our own commonly applied interpretation.

Our interpretation is not intended to undermine or erode any of the definitions adopted elsewhere, which serve different purposes to those within this page.

| Source | Minimum area | Minimum width | Average width | % Open space | Canopy cover | (Potential) Tree height | Minimum stocking density |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National Forest Inventory | 0.5ha[footnote 22] | 20m | Not specified | Do not include power lines, rivers etc. in total woodland area when the break in the woodland is greater than 20m | At least 20% | Not specified | Not specified |

| UK Forestry Standard | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | At least 20% | Not specified | Not specified |

| Rural Development Regulation | 0.5ha | 20m | Not specified | Include forest roads, firebreaks and other small open areas, and temporarily unstocked areas | At least 10% | 5m | Not specified |

| The Countryside Stewardship (England) Regulations 2020 | 0.5ha | Not specified | ≥ 20m | Not specified | At least 20% | 5m | Not specified |

| Woodland Carbon Code Standard (2021) | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | This definition includes integral open space and felled areas that are awaiting restocking (replanting) | At least 20%[footnote 23] | Not specified | 400 stems/ha |

| Regulation (EU) 2018/841 | 0.1ha | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | At least 20% | 2m | Not specified |

| Food and Agriculture Organisation | 0.5ha | 20m | Not specified | Not specified | Over 10% | 5m | Not specified |

| The Environmental Targets (Woodland and Trees Outside Woodland) (England) Regulations 2023 | 0.5ha | 20m | Not specified | Not specified | At least 20% | Not specified | Not specified |

7. Who should I contact?

Sources of further advice

If you have any questions or would like to clarify whether we view your site as woodland, please get in touch.

Find your local Forestry Commission Area team visit Office access and opening times.

For more information on the rules around tree felling, visit Tree felling: getting permission.

For more information on the forestry EIA regulations, visit Environmental Impact Assessments for woodland.

For more information on the UK Forestry Standard, visit The UK Forestry Standard.

For more information on the National Forest Inventory, visit National Forest Inventory - Forest Research.

For more information on the Ancient Woodland Inventory, visit Ancient Woodland (England).

For more information on the Priority Habitats Inventory, visit Priority Habitats Inventory (England).

For the Defra MAGIC map application, visit MAGIC map application.

For more information on the Open Habitats Policy, visit When to convert woods and forests to open habitat in England (March 2010).

-

Bullock v Secretary of State for the Environment and another [1980] 1 EGLR 140; Distinctive Properties (Ascot) Limited v Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government and another [2015] EWCA Civ 1250. See Section 6 for further information on the case. ↩

-

These explanations are based on the legal definition of those terms in the forestry EIA regulations and Council Directive 85/337. ↩

-

As referred to in the Environmental Targets (Woodland and Trees Outside Woodland) (England) Regulations 2023. ↩

-

Ancient Woodland Inventory handbook - NECR248 (naturalengland.org.uk). National Forest Inventory - Forest Research. ↩

-

Regulation 2, The Environmental Targets (Woodland Trees Outside Woodland) (England) Regulations 2023. ↩

-

NATIONAL FOREST INVENTORY WOODLAND ENGLAND 2015 - data.gov.uk. ↩

-

See the UK Forestry Standard, 5th ed., p. 57. The UK Forestry Standard. ↩

-

See the UK Forestry Standard, 5th ed., p. 10. The UK Forestry Standard. ↩

-

The Common Agricultural Policy Single Payment and Support Schemes Regulations 2010 (legislation.gov.uk). ↩

-

The Environmental Targets (Woodland and Trees Outside Woodland) (England) Regulations 2023 mark a distinction between ‘energy forestry’ and ‘woodland’. However, the forestry EIA regulations will still apply in energy crop and energy forestry contexts. This is because the forestry EIA regulations are designed to protect against environmental harm, as well as govern the creation or removal of woodland. The growth (and removal) of root systems from energy crops will have just as much an environmental impact as other kinds of forestry activity. ↩

-

See the UK Forestry Standard, 5th ed., p. 10. The UK Forestry Standard. ↩

-

Section 41, Natural Environment and Rural Communities Act 2006. ↩

-

When to convert woods and forests to open habitat in England (March 2010). ↩

-

The Environmental Impact Assessment (Agriculture) (England) (No.2) Regulations 2006 (legislation.gov.uk). ↩

-

Bullock v Secretary of State for the Environment and another [1980] 1 EGLR 140 at 142. ↩

-

Distinctive Properties (Ascot) Limited v Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government and another [2015] EWCA Civ 1250. ↩

-

Paperback Oxford English Dictionary, Edited by Maurice Waite, Seventh Edition published 2012, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-964094-2. ↩

-

England Trees Action Plan, p. 6. England Trees Action Plan 2021 to 2024. ↩

-

Minimum area mapped for dataset. ↩

-

At least 25% in Northern Ireland. ↩