Initial National Cyber Security Skills Strategy: increasing the UK’s cyber security capability - a call for views

Updated 3 May 2019

Ministerial foreword

Margot James MP, Minister for Digital and the Creative Industries

The UK is a global leader in cyber security. We have a vibrant and growing cyber security sector with huge expertise and some of the most creative and innovative companies in the world. This is central not only to our national security, but also in realising the government’s ambition to make the UK the safest place in the world to be online and the best place in the world to start and grow a digital business.

At the heart of the UK cyber security sector’s success is people. The UK already has some of the best cyber security professionals in the world and a core part of the five year National Cyber Security Strategy is about further developing that talent. We have set in motion a series of major interventions to boost the number and diversity of cyber security professionals in the UK. This includes investing £20m in the flagship Cyber Discovery programme, which aims to capture the imagination of young people and inspire them to consider a career in cyber security, while identifying and nurturing promising talent from a young age. We also continue to develop the CyberFirst initiatives right across the skills pipeline and have launched the Cyber Skills Immediate Impact Fund (CSIIF).

However, as our digitally connected world has expanded at an extraordinary rate, so too has the scale of vulnerabilities and the frequency of attacks that we face. The threat has developed significantly even since the publication of the National Cyber Security Strategy in 2016. Public and private sector organisations worldwide are falling victim to ransomware attacks, supply chains are being compromised and our critical national infrastructure continues to be a target for attack. We are also seeing threats to our democracies from attempted outside interference.

This brings in to even sharper focus the need to develop our people and have the right blend and level of skills. That is why I am so pleased to be publishing this Initial National Cyber Security Skills Strategy that builds on what we have already achieved and sets out a bold and ambitious approach to developing the right cyber security capability in the UK now and in the long term. This goes further than simply increasing the number of cyber security professionals in the UK. It recognises that cyber security is the responsibility of all of us, and of every organisation.

The approach proposed in this document is based on research and extensive engagement with the cyber security community over the last two years. But government does not have all of the answers - this is a complex challenge that requires us to further harness the expertise, creativity and innovation so evident in the UK cyber security community. That is why we are publishing this initial strategy with a call for views to give you the opportunity to engage in a meaningful way and help refine and iterate the approach set out.

This document defines a series of questions to respond to and in parallel we will run a series of events around the UK to explore the themes in this initial strategy further. We will then use the evidence to publish a finalised strategy. I hope as many of you as possible will engage and I look forward to hearing your views.

Margot James, MP Minister For Digital And The Creative Industries

1. Introduction

The five year National Cyber Security Strategy (NCSS), published in 2016, set out the government’s plans to make the UK secure and resilient in cyberspace, prosperous and confident in a digital world. It is backed with £1.9 billion of investment to help in defending our systems and infrastructure, deterring our adversaries, and developing a whole society capability.

There has been significant progress in delivering the NCSS, including the establishment of the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) to help protect our critical infrastructure and services from cyber attacks, manage major incidents, and improve the underlying security of the UK Internet. But since the publication of the NCSS, there has also been a significant increase in malicious cyber activity globally, from hostile nation states and from cyber criminals. As our reliance on technology grows, the opportunities for those who would seek to attack and compromise our systems and data will continue to increase, along with their potential impact.

That is why cyber security remains a top priority for the government - it is central not only to our national security but also fundamental to becoming the world’s best digital economy. A core part of our response is ensuring the UK has the right blend and level of cyber security capability across our economy.

This Initial National Cyber Security Skills Strategy sets out a bold and ambitious approach to deliver that. It comes mid way through the implementation of the National Cyber Security Programme (NCSP) and has at its foundation the range of policies and initiatives which have already been delivered or are in progress to boost the UK’s cyber security capability and deliver on the outcomes set out in the NCSS. It also sets out, based on research and extensive engagement over the last two years, the government’s understanding of the strategic context on cyber security capability and our vision and plan to develop the UK’s cyber security capability now and in the longer term.

The challenge on cyber security capability is complex. Global and domestic market insight reports regularly refer to an unmet demand for cyber security capability. This initial strategy explores how this is felt across different parts of the economy in the context of the wider cyber threats we face as a country, as well as our understanding of the range of factors contributing to the cyber security capability gap. The challenge is much more complex than simply a shortage of cyber security professionals - there is a broader cyber security capability gap in the UK[footnote 1]. This is about the level and blend of expertise and skills needed across the general workforce to help the UK become the world’s best secure digital economy.

The successes so far in delivering against the NCSS have been driven by close working between government and partners across the cyber security community. Continuing that collaborative approach is crucial and there is clear passion, enthusiasm, and a depth of expertise across all parts of the cyber security community which we need to harness.

We believe that making things open makes things better, and we want anyone with an interest to engage and meaningfully contribute to the strategy to develop the UK’s cyber security skills and capability. The publication of this initial strategy introduces a ten week call for views. We have defined a series of questions to formally respond to and we intend to run a series of engagement events in early 2019 to explore these questions further.

Through the questions we seek to validate our assessment of the cyber security capability landscape and identify where there may be additional or further challenges in specific parts of the economy. We also seek to understand whether or not the level of ambition articulated through the mission and objectives is sufficiently ambitious to meet the challenge. To build on our recent consultation on developing the cyber security profession and CyBOK consultations, we ask whether the definition of cyber security skills set out in this initial strategy reflects the consensus view in the UK cyber security community. We also set a series of questions about the proposals on interventions in the education and training ecosystem and how government and industry can work together to develop creative and innovative ideas to increase cyber security capability in the UK.

We are keen for as broad a range of responses as possible - there will be engagement events across England and in each of the devolved administrations. Responses to the questions should be made using the online survey and details of how to sign up for the events will be available through GOV.UK.

2. Strategic context

Overview

This chapter sets out the government’s understanding of the challenge on cyber security skills. This is a complex challenge. Cyber security capability is more than simply the number of cyber security professionals - it is about the level and blend of skills required across the economy. This chapter sets out the threat landscape and why the pace of technological change and the importance of security in new technologies makes this challenge even more pronounced.

Since the government published the National Cyber Security Strategy in 2016, the cyber threat has continued to diversify and grow. In the two years since the NCSC was created it has dealt with well over 1,000 cyber security incidents. In 2017, over 70% of large businesses, 64% of medium businesses and 42% of micro/small businesses in the UK suffered a cyber breach[footnote 2].

The nature of the threat is evolving too; the NCSC believes the majority of the incidents they dealt with in 2017 were perpetrated from within nation states in some way hostile to the UK, meaning they were undertaken by groups of computer hackers directed, sponsored or tolerated by the governments of those countries[footnote 2]. The commoditisation of small scale and less sophisticated attacks also means that even actors with low capability can have an impact.

Focus on: cyber security risks - understanding the threats

The cyber threat to the UK is significant and growing. Cyber threats are becoming increasingly varied and adaptive – ranging from high volume, commoditised and opportunistic attacks to highly sophisticated and persistent threats involving bespoke malicious software designed to compromise specific targets.

The increasing digitalisation of our economy and society compounds this challenge, as our dependency on connected devices and services further increases the potential vulnerabilities that can be exploited.

The make-up of attackers is also varied – from state sponsored actors to cyber criminals, ‘hacktivists’, or the actions of employees, whether deliberate or accidental. Most common of all is from cyber criminals seeking to exploit UK organisations for financial gain – whether that be the sophisticated theft of intellectual property or a simple theft of cash from an account. The rise of ransomware is particularly notable and is having a significant impact both to private businesses and public bodies.

Cyber threats pose a risk to organisations of all sizes and across all sectors, as well as public bodies and critical services.

As we increasingly move more of our daily lives and business online, and as we face an increasingly sophisticated level of threat from our adversaries, cyber attacks are unfortunately inevitable. It is critical that there is the cyber security capability across the economy to ensure that organisations take an informed and proportionate approach to cyber risk management which focuses on resilience, minimising the impact of attacks as and when they do occur.

Given that the threat itself is constantly and rapidly evolving, policy on cyber security skills must be similarly agile and dynamic. This means it is essential that training and skills development - across all sectors - is grounded in an accurate and up-to-date understanding of the threat.

These breaches come with a cost - both financial and/or reputational. We know that only 27% of UK businesses and 21% of charities have a formal policy or policies covering cyber security risks[footnote 4] and many organisations lack the knowledge, understanding and confidence around cyber security to implement appropriate measures[footnote 5]. Risks are regularly downplayed and businesses too often only take protective action after their systems have been breached or they have suffered an attack[footnote 6].

This is a challenge for individuals, the public and private sectors alike. The government, public sector, charities and private businesses are all having to rapidly adapt their behaviours and practices to protect themselves and their customers against this changing cyber threat. New legislation, such as the Data Protection Act 2018 and the Network and Information Systems (NIS) Regulations 2018, make it even more crucial that organisations have a firm grasp of their cyber risk management and can effectively protect themselves and their customers.

Beyond that, new and emerging technologies make this need even more pronounced. The proliferation of the Internet of Things (IoT) means consumers are bringing more and more internet connected devices into their homes, such as smart TVs, smart music speakers, smart washing machines, and even internet connected toys. Furthermore, tools for processing and making sense of large quantities of data have developed exponentially, with artificial intelligence (AI) representing the latest leap. The AI Sector Deal, published in April 2018, sets out the huge benefits and potential of AI and how this technology can transform how we diagnose diseases, manufacture goods and build our homes.

However, with these benefits come associated risks. If internet connected devices sold to consumers lack even basic cyber security provisions, people’s privacy and safety is at risk of being undermined. Additionally, the wider economy faces an increasing threat of large scale cyber attacks - for example a coordinated attack on IoT devices that are part of a smart city could affect electricity supplies far beyond individual homes. Part of how we harness AI and other technological advancements to get the maximum benefit from them is about ensuring they develop securely by design. Having the right capabilities, capacity and professionalism in our cyber security workforce now and in the future is fundamental to that.

Since the publication of the NCSS we have engaged extensively with industry, professional organisations, students, employers, existing cyber security professionals and academia to better understand the nature and nuances of the cyber security skills challenge. We consistently hear that employers struggle to recruit individuals with the skills they need, or that there is a premium for appropriately skilled staff which some organisations struggle to afford.

This is a complex challenge, with a range of issues and causes amplifying one another and combining to make the overall challenge more acute and pronounced. This includes definitions of what we mean when we speak about cyber security, unclear pathways into a career in cyber security, diversity and inclusion, and the changing nature of the general workforce. Underlying all of this is a need for cyber security capability which better meets the demand in an effective, secure digital economy.

A capability gap

There has been a range of research conducted globally which has sought to quantify the shortage of cyber security professionals. The most recent (ISC) global study, for example, sets out that there is a shortage of 2.93 million cyber security professionals internationally. While this gives some sense of the global nature of the challenge on cyber security skills, cyber security capability is more complex than simply the number of cyber security professionals.

Capability is about the level and blend of expertise and skills needed to help the UK become the world’s best and most secure digital economy. Indeed, cyber security is a fast moving and ever-evolving area with a shortage of wholly accepted and adopted definitions - we therefore believe it would be inherently challenging to accurately define the size of the shortage of cyber security professionals in the UK. Nor would producing a headline number recognise the multidisciplinary nature of cyber security as a domain with a number of specialisms, or the fact that for many, cyber security is a small part in a wider role rather than a distinct role in itself.

Indeed, there are many widely recognised cyber security roles, from technical roles like penetration testing and cryptography through to the more strategic positions of Chief Information Security Officers. For many, cyber security is a technical domain and for others it is more strategic or policy focused. We have heard from a range of stakeholders about challenges in recruiting for all of these roles and the fact that organisations in different parts of the economy experience the capability gap differently and have different ways and means of addressing it.

Rather, we have sought to better understand the nature and nuances of the demand and supply to give us a more comprehensive picture of where the capability gap is felt. This demand for more cyber security capability spans both public and private sectors. Traditionally, careers in government have been one of the main pathways for cyber security talent, with strong demand for a range of technical and non-technical cyber security professionals to work in national security in the intelligence and military community and more broadly across the public sector, such as in the NHS, to protect citizens’ data. Increasingly, however, sectors like finance, retail and charities have demands for cyber security professionals which we expect will continue to grow.

The demand is not simply for cyber security professionals either. Responsibility for cyber security goes far beyond that - almost every individual and every part of an organisation has a role to play. The general workforce’s digital literacy and understanding of cyber security will continue to grow in importance, as will the requirement for other professions and sectors to have a more well defined focus on cyber security. We believe cyber security will become a more structured facet of a wider range of roles, in the same way as basic financial or commercial literacy is a part of most jobs in most sectors. This will address the root cause and potentially change the nature of specialist cyber security.

To explore this demand for capability further, government has commissioned research to define the basic technical cyber security skills gap. It identified skills areas based on the five technical controls within the Cyber Essentials scheme (for example securing devices and software, and controlling who has access to the organisation’s data and devices) and two other basic aspects of cyber security beyond this: storing or transferring personal data securely, which is a requirement of all organisations under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), and backing up files and data.

More than half (54%) of all businesses and the same proportion (54%) of charities have a basic technical cyber security skills gap. For public sector organisations, 18% have a basic technical skills gap[footnote 7]. Consequently this means that of the c.1.32 million businesses in the UK, approximately 710,000 have a basic technical cyber security skills gap, of the c.199,000 registered charities approximately 107,000 have this gap, and for the c.12,400 public sector organisations approximately 2,200 have this skills gap[footnote 8].

In the private sector, basic technical skills gaps tend to be more prevalent in sectors such as food or hospitality, whereas, perhaps unsurprisingly, there is less of a gap in the information or communications, and finance or insurance sectors[footnote 9]. For more high-level technical cyber security skills[footnote 10] the skills gaps are higher in the private sector than in the public sector (31% of businesses have a high-level technical skills gap, 22% of charities and 27% of public sector organisations)[footnote 11]. It is estimated that 407,000 businesses have a high-level technical skills gap and 43,700 charities and 3,300 public sector organisations have a high-level technical skills gap[footnote 12]. Technical skills gaps tend to be higher outside the finance or insurance sectors and the information and communications sectors, as well as outside of London[footnote 13].

The vast majority of those with cyber security responsibilities across businesses, charities and the public sector have absorbed them into their existing non-cyber security jobs. Consequently, outside of the external cyber security providers[footnote 14], they are often not labelled as working in ‘cyber’ roles - ust 11% of businesses and 14% of charities on average have cyber security written formally into the job descriptions of one or more staff[footnote 15].

Many organisations choose to outsource their requirement for cyber security capability. Three in ten businesses (30%) and a similar proportion of charities (27%) outsource one or more aspects of their cyber security, while public sector organisations are more likely to outsource, with two thirds (65%) doing so[footnote 16]. Among organisations that do outsource cyber security, most still handle at least some aspects in-house, and while public sector organisations are more likely to outsource some cyber security activities, their level of outsourcing is more likely to be light touch, with more aspects typically handled in-house than in businesses and charities[footnote 17].

While outsourcing is not in itself problematic, there still needs to be some capability in-house to set the requirements, make informed choices and ensure the contracted resource is effective. Anecdotally we have heard that many, particularly small and medium businesses, rely on informal networks and word of mouth to find a provider.

Definitions and a new profession

There are a number of underlying reasons for the capability gap. Part of this is a lack of clear definitions and parameters of cyber security, which mean it can be difficult for organisations to articulate in a consistent way their demands or shortages. Cyber security is still a relatively new area which has developed rapidly and organically over recent years. The understanding of what constitutes a cyber security professional varies - those working in cyber security are found across multiple disciplines with a wide range of different competencies.

We know that cyber security roles within organisations are often not badged as ‘cyber’ roles. Indeed, cyber security is most often managed on an informal basis across organisations - the vast majority of individuals who have some responsibility for cyber security within their organisation do not have formal qualifications and are not working towards them either. Overall, 4% of businesses, 6% of charities and 19% of public sector organisations have individuals with or working towards relevant qualifications (this does not include cyber security external providers)[footnote 17].

This has led to a fragmented narrative around cyber security skills and a lack of coherence between the different specialisms. The lack of clarity means that for those considering a career in cyber security (either those new to the labour market or those retraining), it can often be a hard and confusing landscape to navigate with an absence of clearly established career and training pathways into and through the profession.

Beyond that, like in all sectors of the economy, the labour market is changing faster now than at any time in recent memory. Young people may, in the coming years, be doing jobs that those in the current labour market cannot yet conceive. Those working in cyber security are already having to deal with rapidly changing ways of working and further technological advances on the horizon will inevitably have an impact on the nature of the roles.

We know artificial intelligence and machine learning are already helping keep systems safer and more secure, but with the further development of that technology and the potential of quantum computing bringing even greater power to bear, the nature and way cyber security professionals work is likely to change at an even greater pace. For example, recent research has identified the area of automation, data analytics and threat hunting as key cyber security technical skills that will be required in the future alongside greater mathematical knowledge[footnote 19].

Building blocks in our education system

Currently cyber security is taught in both the higher and further education sectors within the UK, and as a discrete subject in schools in Scotland, either as a unique course or as a module within another course. However, it is often not widely available and the numbers of students participating in these courses or apprenticeships is often low[footnote 20]. Entry into both higher and further educational courses also often requires a STEM qualification or background, thus cyber security courses are having to compete with other subjects and sectors to attract people with STEM skills[footnote 21].

In the further education (FE) space in 2016-17, there were over 47,000 students studying in ICT related fields with 670 students studying cyber security[footnote 22]. Currently (2017/18) there are 230 students who have started the level 4 Cyber Security Technologists apprenticeship and up to 10 students have started the Cyber Intrusion Analysts level 4 apprenticeship[footnote 23].

In the higher education (HE) space there are a total of 105 full-time courses in cyber security available at undergraduate and postgraduate levels in England, and a further 16 elsewhere in the UK[footnote 24]. The number of students undertaking cyber security related courses has steadily increased both at an undergraduate and postgraduate level (in the period 2014/15-2016/17 there was a 22% increase in the number of postgraduates and a 31% increase in the number of undergraduates)[^25]. However, in 2016-17 there were fewer than 6,000 HE students with a cyber security related degree[footnote 26]. In Scotland, there are 13 universities delivering at least 20 graduate level qualifications in cyber security. Scottish further education colleges are also delivering Higher National Certificates in Cyber Security with onboarding for the Higher National Diploma starting from summer 2019[footnote 27], accompanied by shorter Professional Development Awards aimed at upskilling.

We know that computer science is a key enabler for entry level roles in security. Employers have highlighted, however, that they often have to look wider when recruiting entry level roles. They consider those with STEM backgrounds, with a particular focus on computer science, mathematics or engineering, as they often struggle to get students with the complex technical cyber security background required, and further upskilling is needed[footnote 28].

Consequently, this initial strategy lays out plans to ensure that the UK has an education and training system that provides the right building blocks to help identify, train and place new and untapped cyber security talent.

Cyber security in the workforce

As set out above, having an effective, secure digital economy is not the sole domain or responsibility of cyber security professionals. They have, and will continue to have, a key role to play, but embedding cyber security responsibilities in a broader range of roles is crucial if we are to meet the challenge and opportunities that technological change presents.

This starts with wider digital skills; ensuring that all citizens have the digital skills they need to be part of a digital economy and society. The younger generation are often more comfortable with digital technology, and alongside the strong foundation provided by the national curriculum and the fruition of some of the interventions outlined in this initial strategy, they will have a stronger understanding of cyber security. However, we know that there are many in the current workforce who do not have a strong enough grasp of the basics of cyber security hygiene practices.

We also know demand for cyber security capability is not always sufficiently well informed. Some organisations struggle to articulate their requirements. Senior leaders and boards have a significant role to play in resolving this issue. In many cases, they ultimately have responsibility for the organisation’s approach to cyber security and therefore should have an understanding of the threats that their organisation could face and how to counter them. Ultimately, organisations can only attract the talent they require by understanding what they need in the first place.

Continued collaboration between government and all parts of the cyber security community is critical to increasing the UK’s cyber security capability. The public sector needs to be an exemplar of best practice while being open to creative and innovative ideas and initiatives developed elsewhere. There are some excellent examples to build on, such as the NCSC’s advice to organisations and individuals and the partnerships between academia, employers and government that are so critical to developing a world class higher education sector in the UK. Government also needs to use its convening power to bring different parts of the cyber security community in the UK together to collaborate and share best practice. We can also use our reach and networks to ensure the UK is well placed internationally to draw on best practice from around the globe.

Call for views

In this chapter we set out the government’s understanding of the challenge on cyber security skills. We believe the challenge is a complex one which represents a cyber skills capability gap in the UK. Yet we know this is felt differently across different sectors and parts of the economy. We want to validate our assessment of the cyber security capability landscape and identify where there may be additional or further challenges in specific parts of the economy.

● to what extent do you agree with government’s assessment of the strategic context?

● do you think there are any other challenges or issues that are not covered in the government’s assessment of the strategic context?

3. The national response: our mission

Overview

This chapter takes the NCSS strategic outcome as a starting point and sets out government’s proposed longer term mission on cyber security capability as well as our proposed objectives for delivering that mission

The NCSS’s strategic outcome 9 sets out the aspiration to ensure that “the UK has a sustainable supply of home-grown cyber skilled professionals to meet the growing demands of an increasingly digital economy, in both the public and private sectors, and defence.”

The government has already made significant progress on cyber security skills and capability, delivering a range of initiatives designed to boost the number and diversity of those going in to cyber security careers. However, we recognise that, in view of technological advances and the changing and evolving threat landscape, we need to do more and go further. Our ambition is therefore to not only address the supply of cyber security professionals, but also to address the broader capability gap that is so fundamental to maintaining the resilience of our digital economy.

Our mission is to increase cyber security capability across all sectors to ensure that the UK has the right level and blend of skills required to maintain our resilience to cyber threat and be the world’s leading digital economy

The NCSS set out a range of success measures around the profession and education system. Based on our close engagement with industry and partners across the cyber security community, and our ambition to address the broader capability gap, we have built on those to develop four new, clear cyber security skills objectives.

We believe these fully capture our intent and activity to deliver the strategic outcomes set out in the NCSS on cyber security professionals, while recognising that we need to do more to further embed cyber security capability within the UK’s digital economy to ensure its continued security and resilience. The four objectives are:

-

To ensure the UK has a well structured and easy to navigate profession which represents, supports and drives excellence in the different cyber security specialisms, and is sustainable and responsive to change.

-

To ensure the UK has education and training systems that provide the right building blocks to help identify, train and place new and untapped cyber security talent.

-

To ensure the UK’s general workforce has the right blend and level of skills needed to achieve a secure digital economy, with UK-based organisations across all sectors equipped to make informed decisions about their cyber security risk management.

-

To ensure the UK remains a global leader in cyber security with access to the best talent, with a public sector that leads by example in developing cyber security capability.

Call for views

This chapter sets out government’s longer term mission on cyber security skills to increase cyber security capability across all sectors. It also defines four proposed objectives to deliver that mission. We want to understand whether or not the level of ambition articulated through the mission and objectives is sufficiently ambitious to meet the challenge.

● to what extent do you agree that the mission and objectives set out are sufficiently ambitious to address the challenges identified?

● why do you agree/disagree that the mission and objectives are sufficiently ambitious?

4. A structured and trusted profession

Overview

While there has been significant progress to develop the cyber security profession in the UK, more needs to be done. The taxonomy around cyber security can be confusing and routes into and through cyber security careers can be hard to navigate. Addressing this to ensure there is a structured and sustainable cyber security profession in the UK is critical to our cyber security capability. This section sets out the decisive action being taken to develop a clear definition of cyber security skills, an agreed body of knowledge, and to create a new, independent UK Cyber Security Council as the focal point for the cyber security profession in the UK

Objective 1: To ensure the UK has a well structured and easy to navigate profession which represents, supports and drives excellence in the different cyber security specialisms, and is sustainable and responsive to change

Cyber security is a broad and varied discipline that has grown organically and quickly in recent years. While progress has been made to ensure cyber security is a well structured and easy to navigate profession that drives excellence across the different specialisms, there remain challenges.

The definitions around what constitutes a cyber security role or skill are still developing and the concept of cyber security as a coherent profession is a relatively new one. For those working in cyber security and employers of cyber security professionals, the current qualification and certification landscape can be hard to navigate, making it difficult to assess the options available and to make appropriate, informed choices about career paths or the skills that an organisation requires. The technical language and acronyms which are often used can make this challenge particularly pronounced for those new to or unfamiliar with cyber security. The current professional landscape is also complex for existing professional organisations and vendors of cyber security qualifications and certifications, who are often unable to articulate the equivalence of their offerings in the absence of a common technical framework.

We believe the approach to tackling these remaining challenges and delivering the objective set out in this initial strategy has three main components. First an agreed definition of what constitutes cyber security skills, second an agreed body of knowledge for cyber security, and third a well structured professional sector that works to effectively serve the interests of the cyber security community. Government has already taken decisive action to set in motion this activity. The sections below summarise that effort and set out what more government, working hand in hand with the cyber security community, intends to do.

A clear definition of cyber security skills

We are commonly asked about the definitions and parameters of cyber security when talking about developing skills and capability. The NCSS describes cyber security as “the protection of internet connected systems (to include hardware, software and associated infrastructure), the data on them, and the services they provide, from unauthorised access, harm or misuse. This includes harm caused intentionally by the operator of the system, or accidentally, as a result of failing to follow security procedures or being manipulated into doing so[footnote 29].

Whilst this is an accurate definition of cyber security, it does not clarify the skills that will be required by individuals working in the different specialisms of cyber security. To address this, the government commissioned Ipsos Mori to conduct research[footnote 30] into the range of technical and non-technical cyber security skills in the workplace and to develop a clear definition of cyber security skills. They concluded:

“We define cyber security skills as the combination of essential and advanced technical expertise and skills, strategic management skills, planning and organisation skills, and complementary soft skills that allow organisations to:

● understand the current and potential future cyber risks they face

● create and effectively spread awareness of cyber risks, good practice, and the rules or policies to be followed, upwards and downwards across the organisation

● implement the technical controls and carry out the technical tasks required to protect the organisation, based on an accurate understanding of the level of threat they face

● meet the organisation’s obligations with regards to cyber security, such as legal obligations around data protection

● investigate and respond effectively to current and potential future cyber attacks, in line with the requirements of the organisation

This defines the core set of knowledge and skills that organisations need to either have within their workforce, or seek externally (for example, if they outsource their cyber security or take on external consultants). Those working in the wider cyber security industry – developing cyber security products or services, or carrying out fundamental research – may require additional skills, such as the technical expertise and skills needed to research and develop new technologies, products or services.”

An agreed body of knowledge for cyber security

To explore the parameters and breadth of cyber security in more depth, government has commissioned a project to define the foundational knowledge upon which the field is built. The development of the Cyber Security Body of Knowledge (CyBOK) is being undertaken by a team of UK academics, led by Professor Awais Rashid of Bristol University, in consultation with the national and international cyber security sector.

Phase One, completed in October 2017, focused on defining the scope of cyber security. In Phase Two, descriptions of the resultant 19 Knowledge Areas are being developed by experts from across the international cyber security community[footnote 31].

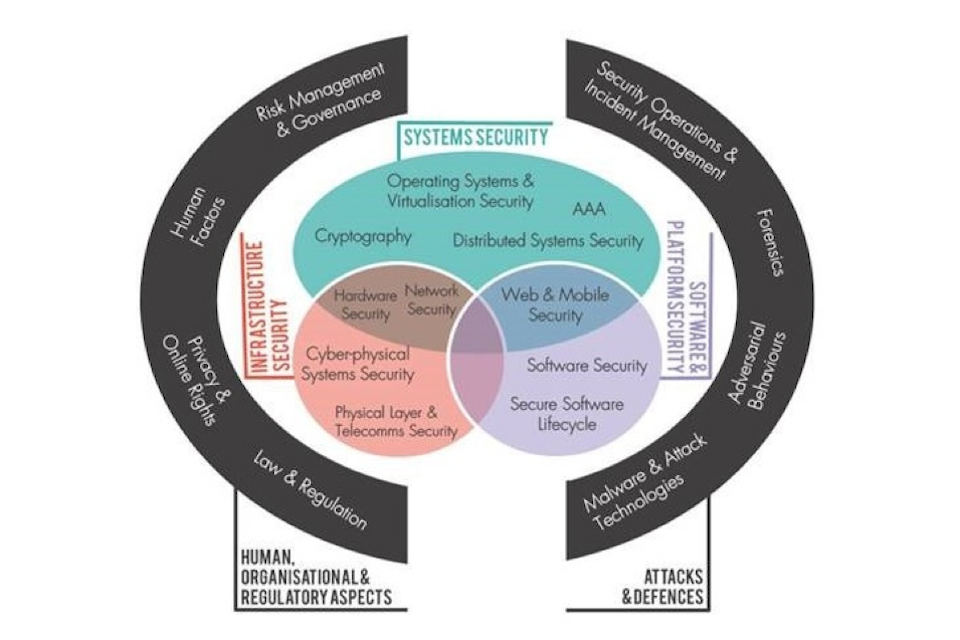

Figure 1: CyBOK Knowledge Areas

It is also worth noting there are already many and varied global initiatives to further describe and develop the domain. For example, in the US the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is leading the National Initiative for Cyber Security Education (NICE) which is focused on cyber security education, training and workforce development. Part of the work to deliver on this strategy will be to explore further how the outputs of the various initiatives align with the UK led CyBOK work.

Proposal 1: We will publish a complete Cyber Security Body of Knowledge, including all 19 Knowledge Areas, in 2019 to ensure there is an excellent foundation for professional standards in cyber security

UK Cyber Security Council

The NCSS sets out a commitment to develop the cyber security profession in the UK and help it achieve Royal Chartered status. The intent behind this was to help ensure those working in cyber security can have their skills and expertise recognised more easily and in a clear and consistent way, as well as helping employers and consumers be more confident in the professionalism, capability and integrity of those they employ or those who provide cyber security services. It also sought to ensure the profession more coherently encourages a broader range of people with the right capabilities to enter the profession.

In summer 2018, government published a consultation which set out bold and ambitious proposals to implement the NCSS commitment to develop the profession. The headline proposal was for there to be a new, independent, UK Cyber Security Council to act as an umbrella body for existing professional organisations and drive progress against the key challenges the profession faces. The consultation set firm deliverables for the Council, such as the creation and promotion of a new code of ethics for cyber security professionals.

We have now analysed the responses to the consultation. The government response, which is published in parallel with this initial strategy, sets out the strong support for the main thrust of the proposals. Government therefore now intends to proceed to identify a delivery lead to design, set up and implement the Council.

One of the key early requirements for the Council will be to develop a framework, agreed across the different specialisms, setting out the comprehensive alignment of career pathways through the profession, leading towards a nationally recognised career structure adopted by the whole cyber security sector across the UK. It will set out how certifications and qualifications relate to one another and link together. As part of that framework, we expect the Council to develop routes to Chartered Status for a new, commonly adopted ‘cyber security professional’ across all specialisms in cyber security. We believe this will help individuals and organisations make informed choices about the certifications and qualifications they require or should look for within certain levels.

In response to the public consultation we have further refined and prioritised other objectives for the Council to deliver. There was strong support for creating an agreed code of ethics across the different parts of the cyber security profession, for example. This is an important early deliverable that will help drive up trust and expectations of professional conduct in cyber security and more broadly enable employers and consumers to be more confident in the professionalism, capability and integrity of those they employ or those who provide cyber security services.

Proposal 2: We will invest between £1m - £2.5m to establish a new, independent UK Cyber Security Council

The newly formed UK Cyber Security Council will be charged with delivering an ambitious programme of work:

● create a defined list of certifications and an easy to understand framework of how they all link together and what capabilities they convey, building on the career pathways work undertaken already

● create a new code of ethics for cyber security professionals across all specialisms

● develop and administer a Royal Chartered Status for cyber security professionals to aspire to

● develop a robust roadmap for the Council becoming self-sustaining and fully independent of government

This process will begin with a competition to identify the delivery lead for the Council.

Call for views

This chapter sets out the decisive action being taken to develop a clear definition of cyber security skills, an agreed body of knowledge, and to create a new, independent UK Cyber Security Council as the focal point for the cyber security profession in the UK. We have recently consulted on developing the cyber security profession and CyBOK knowledge areas continue to be consulted on. We acknowledge, however, that there are still challenges around taxonomy and defining cyber security skills. We are therefore seeking to understand whether the definition of cyber security skills set out above reflects the consensus view in the UK cyber security community.

● Do you think there is anything missing from the definition of cyber security skills?

5. A vibrant education and training ecosystem

Overview

The cyber security capability gap is both an immediate issue and a future concern. This chapter sets out the steps we will take to attract diverse talent into the profession by supporting opportunities to inspire the current workforce to retrain as cyber security professionals, as well as putting in place the building blocks for future careers in cyber security through formal educational and extra-curricular activities that will inspire future cyber security professionals. A key component of this is providing greater coherence and coordination to the range of initiatives that are offered

Objective 2: To ensure the UK has education and training systems that provide the right building blocks to help identify, train and place new and untapped cyber security talent

The cyber security capability gap is both an immediate issue and a future concern. This means taking decisive action at all parts of the education and training ecosystem. To deliver a sustainable and lasting boost to capability, it is crucial that we take steps now to develop the building blocks for future careers in cyber security, ensuring that the talent and skill-sets are available to tackle the security challenges of the future.

This means ensuring that our education system provides genuine opportunities to learn and apply the foundational skills as well as supporting extra-curricular activities to inspire young people to pursue cyber careers.

In parallel, we also need to encourage and support adults who have the right aptitude, including those from non-traditional backgrounds, into cyber security careers. This requires a sufficiently vibrant cyber security training ecosystem that promotes routes of entry into cyber security jobs for a broader and more diverse range of individuals.

Inspiring the current workforce to retrain or upskill

While some specialist cyber security roles require a longer lead time and deeper technical expertise, retraining and career transition is a way to quickly fill many cyber security vacancies and bring a broader range of skills and experiences into an organisation. This might be in the form of retraining or upskilling existing staff in organisations, identifying individuals in other sectors who have the right aptitude and skills, or routing students coming out of university who are looking for a varied and fulfilling career into cyber security.

This is a well established model of entry in some other fields; there is a vibrant market of software developer retraining bootcamps in the UK, for example. There are a number of similar and excellent initiatives in cyber security. This includes an online platform to help further and higher education students get hands-on experience of cyber security and connect with prospective employers. There are also a range of initiatives to help veterans from the military develop the skills needed to become cyber security professionals and a range of employer led in-house cyber training programmes to take new recruits from a range of backgrounds to quickly meet their cyber security capability needs.

These interventions are only possible through the partnership and collaboration of training providers, charities, academic institutions and industry. While this range of activity is positive, there is a need to further develop the training and retraining provision in the UK. Government wants to ensure that there are accessible and attractive opportunities for a much broader range of individuals to train and retrain.

In recognition of that need, the government has sought to support industry to help accelerate the development of the cyber retraining ecosystem. Our key intervention in England is the Cyber Skills Immediate Impact Fund (CSIIF) which is designed to provide funding and support to training providers and charities to run initiatives to quickly boost the number and diversity of those entering the profession.

The CSIIF pilot launched in February 2018 and identified seven initiatives across England which would receive support to stand-up and scale-up. These initiatives are delivered through various methods, from face-to-face teaching to online platforms. Notable examples of sponsored projects include a 10 week retraining bootcamp for women and a neurodiverse community cyber security centre initiative.

Case study: Cyber Skills Immediate Impact Fund (CSIIF) - Community Cyber Security Centre Pilot

A community based initiative proposed establishing a local cyber security training centre to identify, train and place unemployed neurodiverse individuals into cyber security roles. This centre was designed to provide a safe environment, focused on the needs of the trainees, where these individuals could relax, learn and discover their potential in the field of cyber security alongside designated mentors.

While there was interest from industry partners, initial investment from industry was difficult to obtain given this was an entirely new proposal. Through the CSIIF, the proposal secured initial seed-funding that helped to establish the initiative - identifying a location and helping to purchase the infrastructure required to build an operational centre. This initial funding was provided on the basis that it would help to secure match funding from industry, to ensure that the project could become self-sustainable without long-term government funding.

The centre was set up rapidly over summer 2018 and has already helped 24 neurodiverse candidates get ready for a career in cyber security. There has been significant in-kind industry support to provide training platforms (including from other organisations sponsored by the CSIIF) and career advice for participants. Crucially, the initiative has now received further funding from industry to establish a work experience programme for the neurodiverse candidates trained at the centre.

As CSIIF continues to expand and sponsor new initiatives we will undertake a comprehensive evaluation of the Fund to ensure that the projects being funded are delivering the results that our industry partners expect. The outputs will directly inform future industry-led interventions that will seek to continue to develop a cyber security retraining ecosystem and support a sustainable supply of cyber security professionals.

Proposal 3: We will continue to support the development of the cyber security training ecosystem through additional and more targeted government funding. This will include the continuation of CSIIF in 2019/20, as well as exploring other ways of government helping to boost the cyber security retraining provision in the UK.

We will undertake a comprehensive evaluation in early 2019 of government interventions in cyber security retraining to inform our future approach. We will also work with devolved administrations to share best practice and consider wider roll-out

As well as supporting training providers, we are also investing in a Cyber Security Postgraduate Bursaries Scheme to encourage adults to retrain by taking an NCSC certified Masters degrees. Over three academic years, this scheme will support over 150 adults to retrain for a career in cyber security. There is activity across the whole of the UK - the Government of Northern Ireland and the Welsh Assembly, for example, are collaborating with industry to up-skill people in cyber security in preparation for employment by companies in the sector (see the ‘Interventions being progressed by the devolved administrations’ case study).

Case study: interventions being progressed by the devolved administrations

Future Skills Cyber Security Fundamentals Academy (Government of Northern Ireland)

In preparing for the devolution of further fiscal powers to Northern Ireland, the Department for the Economy developed a Future Skills Cyber Security Fundamentals Academy in 2017, to support the recruitment of staff for Foreign Direct Investment or when a collaborative network of employers identify a particular skills need. The Academy is delivered by Belfast Metropolitan College for PWC and Black Duck Software.

Entry requirements promote applications by those that don’t meet the academic criteria but are able to demonstrate technical skills and aptitude. 24 students successfully completed the 19 week Academy training and, to date, 13 have been offered employment with the participating companies.

The National Cyber Security Academy (Welsh Government)

The University of South Wales (USW) and the Welsh Government have joined forces to launch the National Cyber Security Academy (NCSA) to develop the next generation of cyber security experts. The NCSA, the first of its kind in Wales and a major UK initiative, is located in USW’s Newport City Campus and offers the BSc (Hons) Applied Cyber Security.

With funding support from the Welsh Government, the NCSA is involving major industry players including Airbus, Alert Logic, QinetiQ, Wolfberry and the South Wales Cyber Security Cluster. Undergraduates work on real-world projects set by the NCSA partners who help to ensure the course meets the latest cyber security challenges.

It is our ambition to promote and progress the excellent work that is happening across the UK to attract and develop new talent and to support industry in taking on and sustaining these activities following the NCSP. These interventions are providing genuine routes to entry for many and are helping boost cyber security capability. However, we recognise that we need to continue this work, identifying new and creative ways to get a broader and more diverse range of people into cyber security, supporting efforts led by industry to retrain and upskill cyber security professionals across the UK.

Inspiring future cyber security professionals

Formal education provides the universal building blocks that will equip young people in pursuing careers in cyber security. Having access to high quality teaching of computer science in schools will lay the foundations that can be developed and practically applied in further and higher education, empowering people to take up more technical roles that are in such high demand. However, formal education is not the only vehicle for capturing and harnessing the imagination and talent of young people. Extra-curricular activities are a key way of identifying talent and feeding and developing interests at a young age, helping to develop skills and signpost future career paths.

We recognise that in order to successfully capture future talent we need to make sure that future cyber security professionals are informed about the different types of cyber security roles available and the career pathways that they need to take to get there - from taking particular subjects at school or in further and higher education, or gaining relevant experience outside of the classroom. The Scottish Government, for example, has worked with their partners to develop a qualifications pathway from school through to university. In schools, students can study for National Progression Awards in Cyber Security, in colleges there are Higher National Certificates and Higher National Diplomas in Cyber Security, and within higher education institutions students can undertake a range of Cyber Security undergraduate and postgraduate qualifications.

In time, the UK Cyber Security Council will take on responsibility for the development of an agreed framework of career pathways, including qualifications and certifications. However, we acknowledge that the Council will take some time to establish itself and there is work to be done in the interim to address this need.

Proposal 4: We will take decisive action to ‘demystify’ cyber security careers by beginning a programme of work in January 2019 to fully map the different career options and pathways and ensure there is clear and accessible advice for anyone who has the aptitude for a career in cyber security. The outputs of this work will be taken on and owned by the new UK Cyber Security Council.

Proposal 5: We will appoint one or more independent Cyber Security Skills Industry Ambassadors to help promote the profile, attractiveness and viability of a career in cyber security to a broader and more diverse range of individuals. We will work closely with industry partners to define the role(s) but one of the key functions would be to help distil and represent views of the cyber security community to government and vice versa

Formal education - schools

A strong national curriculum is crucial, not only in providing young people with the initial building blocks required for more technical careers, but in developing broader digital skills which are increasingly vital to engaging and working in a digital economy.

Since 2014, computer science has been a statutory subject for 5-14 years in schools in England and provides a valuable foundation for computational thinking, creative problem solving and many other digital competencies. It is encouraging to see a growth in the number of students taking computer science GCSE[footnote 32] and A level[footnote 33] qualifications in England over recent years, but take-up and availability still lags significantly behind other STEM subjects.

High quality teaching is critical to achieving an increase in the number of pupils in schools and colleges who study towards computer science qualifications, particularly amongst girls and in disadvantaged areas. The Department for Education is making significant investment in order to continue to improve the expertise of all teachers of computer science in order to ensure all pupils have the digital skills they need for the future and that teachers are empowered to deliver excellence (see the ‘Investment to improve the teaching of, and participation in, computer science’ case study). Industry led programmes such as STEM Ambassadors are also doing excellent outreach work into schools to try and encourage STEM uptake.

The NCSC Cyber Schools Hubs programme aims to identify methods of building capacity and capability of cyber security educational resources to support teachers in the local community in England. Local schools and their teachers, supported by the NCSC, have formed three pilot hubs using cyber security as a way to encourage a diverse range of students into taking up computer science, supporting students throughout the course and developing new content and resources to be made widely available for teachers. The hubs provide a potential blueprint for a scheme that could be implemented on a national scale to provide a local focus for cyber security resources as well as facilitate industry engagement.

Proposal 6: We will explore how to expand the NCSC Cyber Schools Hubs pilot across England

A similar approach is being taken in the devolved administrations. In Scotland, for example, schools introduce the fundamentals of computer science, coding and digital skills from the early years onwards. Schools are supported to develop digital skills and learning across the Scottish curriculum by the Scottish education agency, Education Scotland, through its Digital Schools Programme, working in partnership with the British Computing Society and digital employers. Scottish schools have delivered National Progression Award qualifications in cyber security since 2015, with increasing numbers year-on-year.

Case study: investment to improve the teaching of, and participation in, computer science

Backed by the £84m funding announced in November 2017, the Department for Education has launched a comprehensive programme to improve the teaching of computing and drive up participation in computer science, particularly amongst girls in England. This includes:

● a new National Centre for Computing Education, including a national network of at least 40 hubs to support schools to provide training and resources to primary and secondary schools

● an intensive Continuing Professional Development (CPD) programme of at least 40 hours for secondary school teachers. This will be designed for computing teachers without a post-A level qualification in computer science and aims to reach up to 8,000 secondary teachers – enough for there to be one in every secondary school

● an A level programme supporting the delivery of A level computing to improve the quality of teaching, and increase students’ knowledge, skills and understanding, to better prepare them for further study and employment in digital roles

A pilot of targeted activities to improve the gender balance in computing qualifications will be launched at a later date.

Formal education - further and higher education

Further and higher education provides opportunities to practically apply the building blocks taught at school and to develop skills that will be applicable in a work environment. This is the threshold into the profession and therefore a crucial stage in converting talent into cyber security jobs.

We have taken forward a number of interventions during the NCSP to support these opportunities. These include apprenticeships, which provide the opportunity to gain real and practical skills while working towards a qualification. Not only are they beneficial for the apprentice, but they offer organisations the opportunity to shape and teach technical skills that have real world application, directly addressing issues of real priority and significance.

Through the pilot Cyber Security Critical National Infrastructure Apprenticeship and the Government Security Profession’s Cyber Security Technologist Apprenticeship schemes, hundreds of apprentices and employers are being supported as they progress through an 18 month to 2 year Cyber Security Technologist level 4 apprenticeships programme[footnote 34]. Launched in September 2018, the NCSC is also supporting 61 students through a three year Cyber Security Technical Professional Degree Programme, culminating in the award of Degree (level 6) apprenticeships.

In Scotland, there is a Modern Apprenticeship available in Information Security aimed principally at school leavers but also available to people of all ages. There is also a Graduate Apprenticeship in Cyber Security, currently provided at Bachelor and Masters levels.

Proposal 7: We will complete the evaluation of the current Cyber Security Critical National Infrastructure Apprenticeship scheme to inform how to best support the particular critical national infrastructure need in future. We will ensure industry is closely engaged in the evaluation process.

Studying for a university degree is a traditional route of entry into professional life. The NCSC delivers the CyberFirst Bursary Scheme which aims to support and prepare undergraduates for a career in cyber security. The NCSC partners with other government departments and selected industry to offer students £4,000 per year and paid cyber skills training to help them kick start a career in cyber security, either in government or industry. The scheme has supported over 500 bursaries since it was established and has a target of supporting 1,000 students by 2021.

More broadly, the NCSC has certified a number of degree programmes to signpost high quality degrees for those who are interested in pursuing a career in cyber security. Currently the NCSC has certified 23 postgraduate Master’s degrees, three Integrated Master’s degrees and three Bachelor’s degrees. NCSC-certified degrees are key to enabling universities to attract high quality students from around the world, as well as enabling prospective students to make better informed choices when looking for a highly valued qualification. They also assist employers in recruiting skilled staff and developing the cyber security skills of existing employees.

In addition, we want to explore creating a scheme to recognise Academic Centres of Excellence in Cyber Security Education (ACEs-CSE). We envisage these would build on the existing NCSC-certified degree programme and help to drive excellence by linking together a number of initiatives around outreach, diversity and cyber security education for all university students. We believe ACEs-CSE would help further develop a strong UK cyber security education community and provide a scalable approach for outreach, engagement and teaching of cyber security across universities and communities.

Proposal 8: We will explore options for setting up Academic Centres of Excellence in Cyber Security Education across the UK.

To make the most of the highest levels of academia, in 2013 we established two dedicated Centres for Doctoral Training in Cyber Security Research which have supported 20-30 students a year to undertake a four year doctoral programme, including a taught first year in cyber security. The Centres foster an interdisciplinary environment, welcoming students from a wide range of academic disciplines. Students gain a grounding in core cyber security knowledge and tackle collaborative projects with industry, as well as building doctoral level research skills. Graduates from the early intakes have gone on to roles in academia, government, tech firms and startups.

Proposal 9: We will continue to support the next generation of Centres for Doctoral Training that include a cyber security focus. Government will also continue to work with universities across the UK to directly support doctoral study in areas of strategic interest related to cyber security.

Further and higher education are traditional gateways to employment and will remain a fundamental route to entry. However, it is important that relevant courses stay abreast of technological developments and cyber threats and are teaching students the fundamentals and principles of cyber security, as well as the transferable skills that can be developed further in a professional environment.

It is important to acknowledge that not all cyber security roles are technical in nature. We must therefore ensure that proper consideration is given as to how we can capture those with the aptitude and skills that can be applied to other cyber security roles that are in high demand. In Scotland, for example, the University of Highlands Islands will soon begin delivery of a Masters-level module in ‘Managing Cyber Risk’ aimed at senior managers in organisations who have a remit for resilience and essential services. While the work being done to demystify cyber security careers - setting out the different roles within the sector and mapping career pathways to achieving them - will promote these different options, there is more we can do to directly tap in to this talent pool.

Proposal 10: We will explore how government and industry can attract new and untapped talent to careers in cyber security, to boost numbers and diversity of those entering the workforce.

This will include how to support individuals with the aptitude and skills for non-technical cyber security roles, such as cyber security policy or strategy positions, and how to better capture and support new and recent graduates in pursuing a career in cyber security, for both technical and non-technical roles. For example, we will explore increased provision of placements and incentives for cyber security graduate schemes.

Focus on: diverting individuals at risk of breaking the law

The UK Serious and Organised Crime Strategy, published in November 2018, recognises the need to divert individuals from reoffending or getting involved in cyber crime in the first place. The limited evidence suggests that those at risk of offending regularly lack an understanding of the legal and ethical issues that present themselves when using certain skills associated with cyber security.

At the same time, the advanced skills that some of the Prevent target audiences possess are in high demand, and if diverted to more meaningful activity before engaging in crime their skills could present an opportunity for a more positive future. An effective response against the threat from cyber crime requires a joined up approach with the UK’s Cyber Crime Prevent strategy led by the Home Office.

Proposal 11: Using the convening power of government, and developing a stronger connection between law agencies and the range of CyberFirst programmes, cyber security employers will link up with law enforcement agencies to explore what interventions they both may be able to offer those people identified as at risk

Extra curricular activities

While formal education plays a significant role in providing young people with the building blocks of digital skills that they need to build a career in cyber security, the importance of activities outside of the classroom in inspiring and promoting cyber security as a profession cannot be underestimated. It is particularly important for those who do not naturally thrive in a formal education environment. During the first two years of the NCSP, we have developed and delivered a number of interventions designed to identify and harness future talent, paying particular attention to the diversity of the talent pool.

Our flagship £20 million Cyber Discovery programme is aimed at 14-18 year olds and brings together real-world cyber expertise and educational experience to find and nurture the next generation of cyber security technical leaders. Over 23,000 students have registered for Cyber Discovery since it launched in late 2017, of which more than 50% completed six or more of the online challenges, with 170 high achieving students winning a place at an industry-led bootcamp. Now in its second year, we expect to see many more young people engage and reach high levels of technical competence, as well as a genuine interest in pursuing a cyber security career.

Focus on: Cyber Discovery - tapping into the cyber security leaders of tomorrow

The government launched Cyber Discovery in 2017, with the aim of supporting the UK’s cyber security skills capability by identifying and engaging young people and nurturing their interest in cyber security as a future career path.

The programme is an important component of CyberFirst, the government’s cyber security education and skills programme, and is designed to ensure that many more people enter the cyber security profession in the coming years.

Delivered for the government by SANS Institute, Cyber Discovery is a free, extra-curricular programme that is open to young people aged 14-18 years old across the UK. The programme takes participants through a comprehensive, online, cyber security curriculum which uses gamified learning created by cyber security industry experts. It covers everything from digital forensics, defending against web attacks and cryptography, to Linux, programming and ethics, and seeks to provide a clear entry path to future cyber security roles. The course content is fun and challenging, delivered through a role-playing game and mixing online teaching, with face-to-face learning opportunities and real-world technical challenges.

The programme is designed to challenge students through progressively harder material. Students who qualify through the first digital phase - Assess - are then invited to continue to two further online phases - Game and Essentials - where they take on the role of a security agent; gathering information, cracking codes, finding security flaws and dissecting a cyber criminal’s digital trail using in-tool resources and research techniques.

Students are supported by online tutorials and by mentor-led after school clubs, often run by computer science teachers, as they find that the curriculum and resources support and extend the current GCSE computer science content.

The top performing students are invited to the final, face-to-face phase of the Challenge - CyberStart Elite Bootcamps. Here they work together in teams, taking on complex, real-world technical challenges, meet industry leaders to find out what it is like to work in the sector, and receive practical help in how they can progress to further cyber security study or jobs.

The first year of the programme has already identified highly talented students who have the skills to become the cyber security professionals of the future:

● over 23,000 played CyberStart Assess, with 12,500 achieving high enough scores to go through to the main part of the programme CyberStart Game and Essential.

● over 800 students reached the highest level Cyber Start Elite and 170 students were selected to attend two-day bootcamps in the summer of 2018

● 60% of students who, having played Game, would now consider a career in cyber security

● 75% of students who played in year 1 considered returning to Cyber Discovery in year 2

● 91% of club leaders said they would like to carry on with Cyber Discovery in year 2

“One of the problems that I always found looking at the cyber security industry from the outside was the lack of any entry-level programmes. Looking forward in the short term, I am extremely excited about the CyberStart Elite Camps (‘hack the robot arm’ and Capture The Flag competitions), but in the long term, I’m actually most excited for the doors that Cyber Discovery has opened for me.”

Daniel, 17 year old Cyber Discovery Student

The CyberFirst Girls Competition is another example of an extra-curricular activity that is specifically aimed at inspiring girls to consider studying a GCSE in computer science and pursue a career in cyber security. The 2018 competition saw 4,500 young women from 400 schools participate. In 2019, we will extend the competition to include a week long event to encourage competitors to continue to pursue cyber security as an interest, and as a potential future career.

Case study: wider impact of the CyberFirst Girls’ Competition

Kye Academy in Ayr has used the opportunity of the CyberFirst Girls’ Competition to achieve a gender balance in its delivery of Scotland’s national cyber security qualifications. Scott Hunter, a teacher at the school, entered several teams in the 2017/18 round of the Competition and the experience so inspired girls at the school that 13 girls are now studying for a National Progression Award in Cyber Security at the school, with one clase split 50-50 boys and girls.

Mr Hunter says, “We’ve had great success in inspiring boys to take the qualification in the past, but the Girls’ Competition has really helped us show girls that they too can learn cyber security skills and work towards a well-paid and rewarding career”.

It is not just government that is investing in this area. Wider industry also recognises the impact that providing extra-curricular events and challenges can have on capturing the imagination of those less engaged, or not in formal education. There are many excellent industry and wider cyber security community led extra-curricular activities on offer. For example University Technical Colleges run cyber security curricula for 14-18 year olds, working directly with cyber security employers, and the Cyber Security Challenge UK has worked with industry partners to design challenges and run a series of competitions aimed at testing cyber security skills from those beginning secondary school to those seeking a career change.

While these interventions are capturing and fostering the talent of many cyber security specialists, we acknowledge that they are presently disproportionately focused on developing the more technical cyber security skills. However, we know that addressing the capability gap requires a much broader range of skills and more must be done to account for those other aptitudes and skills that are directly relevant to cyber security.

Proposal 12: We will continue to invest in extra-curricular activities, such as Cyber Discovery and the relevant aspects of CyberFirst, to inspire young people of school age across the UK to understand and consider a career in cyber security. This will include exploring additional extra-curricular activity to develop non-technical cyber security skills for 14-18 year olds.

Proposal 13: We will explore an extra-curricular cyber security learning platform for young people aged 5-14.

Focus on: a more coherent offering

There has been significant progress to increase the number of entry points into a career in cyber security, but we recognise that the range of government and industry led initiatives can sometimes be confusing and overwhelming, or hard to find.

We need to bring greater coherence and coordination to the range of initiatives that are offered in a way that is consistent and accessible. There is a range of activity underway to address this, however we recognise that we need to do more. We recently completed a review of the CyberFirst brand to enable us to unify all existing and potential initiatives under one single brand and ensure that the new brand appeals to all ages and experience. This will help to simplify the offering to the public and industry partners, promoting and driving up participation.

It will also help government and industry work more effectively together. CyberFirst, in its current form, is supported by over 50 companies and 19 government departments. By bringing more government cyber security skills activity under the CyberFirst brand, we believe industry will be able to take a much more informed view of where to target their support and efforts. We also want to encourage industry to take on and deliver CyberFirst content to give it a much broader reach.

Proposal 14: We will launch the refreshed CyberFirst brand in 2019 which will bring greater coherence to the government’s offering on cyber security skills for all age groups.

Proposal 15: We will continue to encourage industry to use CyberFirst content to deliver additional events and further boost the provision of extra-curricular initiatives.

Focus on: diversifying the workforce

Ensuring the UK has the capability, diversity and professionalism within the cyber security workforce to meet our needs across all parts of the economy is a critical part of the Develop strand of the NCSS and has been a dominant theme throughout this initial strategy.