A UK cyber growth action plan - final report

Updated 19 September 2025

Presented to Parliament by the Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Science, Innovation and Technology by Command of His Majesty

September 2025

CP 1406

© Bristol University and Imperial College London 2025

ISBN 978-1-5286-5971-0

This report is the output from an independent, rapid analysis to provide key insights on the interventions needed to further develop the UK’s cyber security sector. Carried out by a team from the University of Bristol and Imperial College London, it builds on the Cyber Security Sectoral Analysis 2025[footnote 1] and the UK government’s Modern Industrial Strategy. It was produced in time to feed into the refresh of the National Cyber Strategy.

The authors of this work were supported by and would like to thank the Centre for Sectoral Economic Performance at Imperial College London.

The authors are also very appreciative of the insights of the many individuals who have generously given their time to provide both challenge and support. Whether they took part in roundtables, were interviewed, or sent comments, the report refers to them all as participants.

The report focuses on growth of the UK cyber security sector, whilst paying attention to resiliency and value for money. The aim is to grow a thriving cyber security sector that enables the UK to be the safest country online, whilst recognising a persistent challenge: that those who make purchasing decisions often do not see why they should be investing in cyber security.

There are many audiences and stakeholders that take an interest in how cyber security is shaped, and the UK’s cyber security community across government, the private sector and academia, is well connected, collaborative and innovative. This community is a real asset to help cyber security companies grow and attention has been paid throughout the report as to how we can build on this strength.

Executive summary

This report, which is based on input from the supply and demand side of the UK cyber sector, is focused on the growth pillar of the refreshed national cyber strategy.

Cyber security has been identified as a frontier technology in the Digital and Technologies sector plan of the Industrial Strategy and the UK cyber sector is growing, but so is the cyber threat. With all organisations depending more on digital infrastructures, cyber resilience is critical to enabling all sectors of the economy to grow. This wider economic growth, in turn, should help to fuel innovation and growth in the cyber sector. There is huge need and opportunity for the UK to find ways to reinforce this virtuous cycle of cyber growth and resilience.

The report highlights that to achieve this, the stakeholders in industry and government need to:

-

push this virtuous cycle of resilience and growth by stimulating informed demand and supporting businesses at all stages of their growth journeys in meeting that demand;

-

make strategic choices about where to focus on technologies and sectors; and

-

simplify and clarify the roles of government (including the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC)) in relation to cyber resilience and growth.

The growth plan described here includes nine recommendations and 24 associated suggestions which outline actions for all parts of the UK cyber ecosystem including government and industry. In summary they call for:

-

Curating the UK’s cyber culture to drive growth and public participation in cyber skills and innovation.

-

Putting leadership in the right places with industry-led national and place-based cyber growth roles.

-

Building on the UK’s places of cyber strength to collaborate on sensitive topics, chosen technology areas and make time to create and anticipate cyber futures.

There are important roles in this growth plan for industry, government, academia, investors, and civil society. The good news is that throughout the consultation the authors found that all parts of the community were already capable, willing, and engaged on the challenges and opportunities for the UK. The plan emphasises the need for shared principles to act as one team and to both recognise and act upon the connections between cyber growth, resilience and value for money.

1. Introduction

The UK’s cyber security sector continues to grow strongly, with jobs (up 11%), revenue (up 12%) and Gross Value Added (GVA) (up 21%) all increasing over the past year. The sector employed an estimated 67,300 in over 2,100 companies in 2024, offering a range of products and services.[footnote 1] There are also a large, but unquantified, number of individuals in cyber, risk, data and IT roles within organisations in every sector who perform cyber security tasks such as managing access controls, responding to incidents, and ensuring compliance with security and data protection policies. These individuals have different levels of knowledge and experience, ranging from a basic understanding to deep cyber expertise.

Organisations and individuals collect and use ever more data; our physical world is increasingly instrumented and controlled by digital systems; our systems are becoming more integrated and the technology stack more complex. The pace of these changes, not least in AI is astonishing, with much of this happening without adequate attention to cyber security. This makes keeping the UK safe both a challenge and an opportunity for cyber companies.

The challenge is considerable, with damaging cyber-attacks continuing to be in the news underlining that more needs to be done to ensure the country’s economic security and resilience. From state actors to organised crime, to hacktivists and opportunists, motivations are varied. There is specialisation amongst, and marketplaces for, the various threat actors, creating an innovative economy of attack capability and services.

As organisations standardise their digital infrastructure to streamline operations, they build extensive networks of homogenous systems with shared configurations and vulnerabilities. Therefore, even without threat actors, our reliance on such systems creates opportunities for misconfigurations and poorly tested patches, meaning that a single “mistake” can lead to global consequences.

AI is already becoming a key part of the toolkit for both attackers and defenders, with implications that are still poorly understood[footnote 2]. There is the potential scale and sophistication of AI-driven attacks, the question of where accountability will lie should we need to rely on autonomous AI systems in defence and the possibilities of all kinds of collateral damage.

For a growing cyber security company, even with a clear market opportunity, there is a lot to navigate. In addition to the challenges common to other frontier technologies, such as raising capital, there are cyber sector-specific challenges that can slow down progress.

Early-stage product companies often face difficulties deploying solutions in representative environments to test whether proposed solutions scale effectively. Securing ‘lighthouse’ customers – especially government departments – can be critical for many companies but difficult to achieve. Many face strategic trade-offs, perhaps having to choose between developing sovereign solutions for national security customers or focusing on the export market. On top of this, companies must learn how to talk with business leaders about risk and the role of cyber security in fostering consumer trust, protecting reputation and supporting the reliable operation of IT systems. Many business leaders may see cyber security as a net cost rather than an opportunity and struggle to understand how a technology or service could enhance the resilience of their organisation.

There is a lot to celebrate nationally, with growing attention and momentum behind efforts to develop the skills and places from which innovative new companies can emerge. The ecosystem is rich with activity. It includes the CyberFirst programme and vibrant local cyber communities coordinated through the UK Cyber Cluster Collaboration (UKC3). The UK Cyber Security Council is leading efforts to professionalise the sector, while CyberUK plays a role in convening stakeholders across the landscape. Meanwhile, the NCSC’s Research Institutes and Academic Centres of Excellence are strengthening the evidence base and training the next generation of inventors, scientists and engineers. Across the country, there is a generous, energetic, and nurturing cyber community helping individuals and companies to grow.

Yet there is more that can be done.

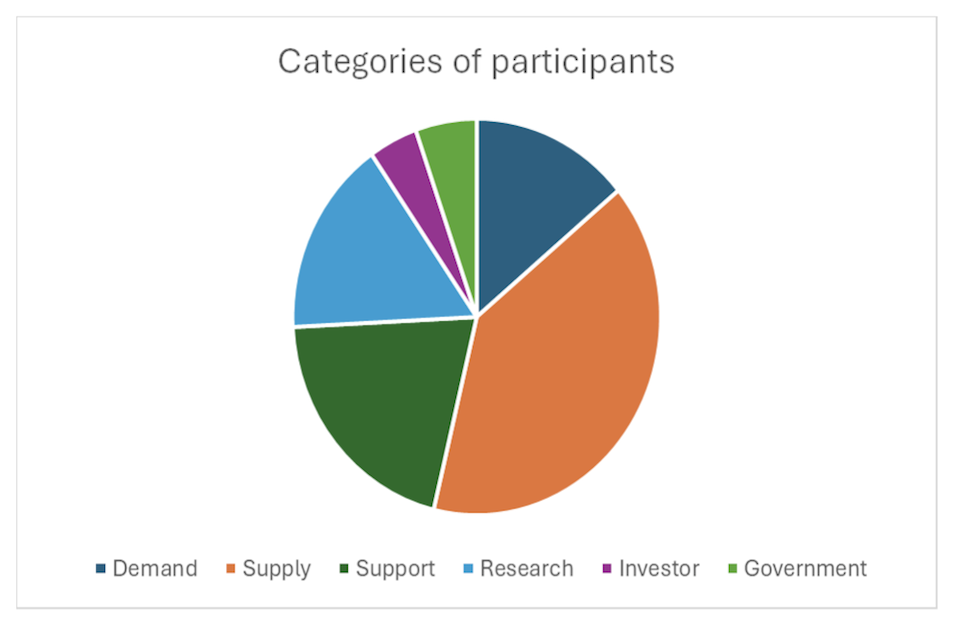

This report sets out a targeted action plan, developed from the insights of diverse experts in the cyber community. It is grounded in interviews and roundtables with 93 participants conducted between May and July 2025. It is based on perspectives from startup founders, security technologists, security service providers, security product vendors, Chief Information Security Officers (CISOs) from multiple sectors, large technology vendors, cyber research scientists and engineers, public interest technologists, trade, accreditation and membership associations, investors, regional leaders, and various parts of government.

Section 2 of the report looks at how cyber security companies can be better supported in their growth journeys and what additional roles the NCSC and the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT) might play. It also considers the part played by the underlying culture of cyber and the language we use.

There are still many organisations that are not paying attention to the fundamentals or following the Government’s baseline standard, Cyber Essentials. Section 3 looks at the interplay between supply and demand, and in particular the role that regulation plays in stimulating demand.

Companies grow faster when they are surrounded by others from whom they can learn. Section 4 looks at the role of places and leadership in growing the UK’s cyber innovation ecosystems.

Much of the attention within government and the cyber security sector is focused on today’s challenges. We also need to prepare for tomorrow. Section 5 looks at where opportunities for growth lie, focusing on AI, cyber physical systems and tools that lower the burden for organisations to have a fundamental level of security and resilience.

Policy is a lever that can help to stimulate growth, Section 6 looks at possible strategy alignment across the many policy documents that refer to cyber security.

Recommendations are brought together in Section 7, Conclusions. A technical annex outlines the methodology used in collecting evidence and suggest how growth might be measured

1.1 Recommendations

This report makes nine recommendations organised around three pillars: culture, leadership, and places.

Assessing growth can be complicated. Revenue, GVA, jobs and investment are all indicators, but they don’t always move in synch. Some of the recommendations focus on growth of the cyber sector, while others aim to help with the growth of the wider economy through the emphasis on incident prevention, resilience, and creating cyber confidence. Each recommendation may have different initial impacts on job creation and productivity.

Throughout the report are suggestions for the implementation of the recommendations and areas for further research. While not exhaustive, they represent insights and options for next steps. Given the rapid nature of this review it is expected that further work will be needed to create more granular recommendations such as to target product or services growth, or how to proceed with specific places.

Each recommendation sets a direction for creating growth in the UK cyber sector. While each can be pursued individually, they are designed to be implemented in combination to maximise impact and drive systemic change.

A culture for growth

Growing cyber businesses depends on the interaction between the vendors and the CISOs and managers who procure products and services. This relationship between supply and demand is shaped by the UK cyber culture and mindset. To strengthen this, we can focus on supporting the growth journeys of cyber businesses, setting clearer expectations for how cyber risk should be managed and reported to increase informed demand, and engaging civil society on the role cyber growth plays in the UK’s safety and prosperity.

Recommendation 1 – Support growth journeys

Government and industry stakeholders should review the incentives and validation routes available to cyber businesses.

The goal is to make it easier for cyber businesses to navigate the complexity of meeting cyber demand and to shift the culture to one that selects and helps winners to grow.

Recommendation 2 – Stimulate informed demand

Government should use guidance and regulations to stimulate growth by setting expectations for high quality reporting of cyber risks, consulting on mandating the use of Cyber Essentials, and encouraging usage of cyber insurance and principles-based assurance.

The goal is to encourage organisations across sectors to prioritise cyber security in alignment with their organisational risks, thereby reducing incidents, increasing resilience, supporting broader economic growth, and driving demand for more UK cyber services.

Recommendation 3 – Foster public participation in cyber skills and growth

UK cyber professionals should engage with UK civil society on the sector’s role in national resilience and prosperity. This means emphasising the role cyber teams play in ‘keeping the lights on’ and the importance of skills initiatives from schools to professional development for cyber founders and leaders.

The goal is to build broader UK support for the role of cyber, making it easier for businesses to prioritise cyber, for people to learn cyber skills, and for the industry to attract, grow and maintain talent.

The need for leadership

The UK cyber community has many leaders but not many are focused on connecting supply and demand for sector growth. We recommend creating and elevating cyber leadership roles in government and places where there is research and development activity and commercial strength to drive and support growth outcomes.

Recommendation 4 – Appoint a UK cyber growth leader

Government should appoint a leader to provide expertise and drive coordinated action across the cyber security industry and within Whitehall. This role would encompass some of the previous Cyber Ambassador’s responsibilities in advancing export growth and supporting national security objectives. It would also include responsibility for driving this growth plan forward.

The goal is to ensure cyber growth is prioritised and integrated across several policy areas.

Recommendation 5 – Appoint growth leaders in places of cyber strength

Appoint place-based leaders to be responsible for convening and driving cyber growth initiatives and outcomes. These leaders should have industry experience, support the UK cyber growth leader and be independent from central and regional government.

The goal is to ensure places use their strengths to grow, create, and attract more cyber businesses.

Recommendation 6 – Expand the NCSC role

The Government should expand and appropriately resource the NCSC to help drive cyber growth. The NCSC is a ‘crown jewel’ for cyber resilience, which is their primary mission. They also have the capability to guide and steer for growth outcomes. Given the importance of resilience, growth should be added without diverting attention from their existing priorities.

The goal is to use the deep expertise of NCSC in support of cyber growth, guiding and validating cyber businesses, research, futures, and technologies.

The role of places

Places play a vital role in innovation and growth – attracting investors, shaping Research and Development (R&D), and building the relationships needed for cyber businesses to start and grow.

Recommendation 7 – Develop futures-oriented communities

Place-based leaders should use their convening role to look forward and shape future markets. To do this, they should bring together CISOs, academia, small and large industry, government, and other stakeholders to share perspectives on, and pursue solutions to emerging cyber challenges.

The goal is to drive initiation, co-creation and delivery of innovative projects into the market, and to build a culture of anticipation.

Recommendation 8 – Places to nurture distinct tech areas

Places should be strategic in prioritising technologies and application areas based on their cyber strengths and sector connections in alignment with the Industrial Strategy and the UK Government Resilience Action Plan. Cyber innovation in AI, cyber-physical systems, and tooling for fundamentals should be considered as initial priority areas. The goal is for the UK to have place-based cyber strengths that are more than the sum of their parts, each contributing to UK cyber growth.

Recommendation 9 – Places to provide safe environments

Create safe havens with infrastructure and data for multiple groups of stakeholders (not just those with security clearances) to explore, ‘role-play’, co-create and share how to assemble and test solutions to current and emerging challenges.

The goal is to build broader cyber resilience capability, which will both serve in moments of crisis and be a pool of talent for cyber growth.

Underpinning principles

To realise the opportunity for cyber growth, these recommendations should be underpinned by a set of principles that should be held in mind by all stakeholders.

Underpinning principle 1 – The UK cyber sector should act as one team

Many stakeholder groups have overlapping but distinct interests, and there are plenty of examples where they have built trust and supported each other. Collecting from the above recommendations, the community should start to operate as a single team growing cyber in the UK. This starts with celebrating, building on and catalysing the social capital in the UK cyber community.

Underpinning principle 2 – Growth + resilience + value for money

The broader benefits of cyber resilience and growth should be recognised as part of ‘value for money’. Too often, purchasing and investment decisions are driven by a cost-based view of ‘value’ missing, the wider importance of UK cyber innovation for future resilience, sovereignty, and growth.

2. A culture for cyber growth

The UK cyber sector is a strong and willing community. However, it needs to broaden and expand if the UK is to achieve cyber resilience. This section examines the current UK cyber culture in three parts.

The first subsection considers the environment businesses currently need to navigate to grow. It reports on participants’ experiences with seed funding, accelerator programmes, venture capital and exports. Recognising the views of starts ups and mature businesses alike, it unpacks how to address the recommendation on ‘supporting growth journeys’.

The second subsection looks at the programmes in place from schools and professional development through to the entrepreneurial skills needed to grow companies. It discusses the role of culture and language in cyber skills training and development, while bringing attention to recent successful initiatives like Cyber First (now Tech First), Board Toolkits and Exercise in a Box.

The third subsection discusses the role of communication and engagement of civil society beyond the circle of cyber experts. It discusses the wider challenges of conveying the value of cyber and building public trust in technologies and institutions. The subsection concludes with linking the importance of maintaining a healthy public dialogue on the roles of technology in society. It discusses public engagement as an enabler of skills development and growth for all businesses.

2.1 Supporting cyber growth journeys

Participants shared a range of perspectives on the strengths and challenges facing the UK’s cyber innovation and scale-up landscape. Many acknowledged that cyber remains a national success story, highlighting security products and services as one of the UK’s leading export sectors. This achievement is underpinned by the country’s reputation for rule of law and high-value service provision. Relationships and brand association, especially the NCSC and the role of the Cyber Security Ambassador, were seen as some of the most valuable enablers of commercial success. However, participants expressed disappointment about the lack of renewal of the Cyber Security Ambassador role.

The UK has technical talent in universities, government agencies and industry. Across critical national infrastructure, financial services, and other sectors there are people and networks with significant experience and knowledge maintaining cyber resilience. Some cyber businesses do start and scale, but most participants felt that the UK could do better, and that culture is essential to this ambition.

Matching other views on the UK startup culture[footnote 3], many participants highlighted that there are too many startups taking too long to fail or pivot. The public R&D funding was described as too small, fragmented, overly focused on early-stage R&D and limited in supporting commercialisation. Being incentivised to go for grants can ‘leave startups in campaign mode’ and prevent them from focusing on priorities such as validating markets or growing sales. Some participants described how this incentive can move businesses away from product innovation towards providing specialised services, which has consequences for the kind of growth (scale, GVA or jobs) they create.

Other participants, particularly those with experience of investment and risk capital, pointed out that the UK has a way to go to match the ambitions, involvement of CISOs, and the risk appetite of other parts of the world. This starts with encouraging and supporting potential cyber founders. Participants talked of still seeing the cliché of technology solutions looking for funding without the entrepreneurial mindset to focus on customers. Programmes like Cyber Runway and Cyber ASAP have been good for training cohorts in addressing this but, given the challenges, more support is needed[footnote 4]

Growing cyber businesses does have specific challenges. Several CISOs shared that budget constraints limit their ability to invest in innovative products. In a risk-averse climate, most security buyers will rely on sector incumbents and well recognised brands. CISOs are dealing with complex people, process, and technology problems. They have seen many cyber solutions dressed as silver bullets, which are usually not as novel as the vendor claims and underestimate the deployment or integration effort. It takes time and deep understanding of buyers’ problems for founders to gain credibility with their solution.

Although there are venture capitalists and angel investors with cyber expertise and a growing cohort of successful founders, some participants highlighted issues with accessing investors who are aware and interested in cyber security. This could reflect that the culture of hype in the startup ecosystem still needs to be navigated. This is echoed in the industry literature, which points out a gap in venture capital investment between ‘trendy’ areas like Generative AI and more operational ones, like cyber security.[footnote 5]

Previous research that explored commercialisation of cyber in Academic Centres of Excellence in Cyber Security Research universities, highlighted the need for strong personal and community bonds and that only those academics who seek to come through some institutional barriers are likely to succeed. This exemplifies the need for universities and R&D centres to build teams of domain-specific commercialisation practitioners who can work together to attract venture capital and position products[footnote 6]

Participants, including successful cyber founders, highlighted that more could be done to connect startups with CISOs. The idea is expanded in the blog on ‘The UK fly wheel: time to win’[footnote 7]. Having ‘UK flag carrying brands’ supporting startups can help businesses grow and gain credibility and participants pointed to financial services and the large mid-market as areas of strength.

Many highlighted that the UK Government has huge demand for cyber security, enough to sustain many startups, but that government can be difficult to work with. There have been many attempts to fix this, but the problems run deep with cyber being treated as ‘one more item on the procurement checklist’. Participants highlighted the potential for DSIT and the NCSC to work together with government departments and procurement leads to stimulate the UK cyber market.

Many pointed out the capability in the NCSC both for spinning out technologists and IP, and for working with Small and Medium Size Enterprises (SMEs). The NCSC for Startups[footnote 8] was a selective programme that gave great networking and visibility opportunities for over 70 UK cyber startups. This example of picking and helping ‘winners’ was clearly beneficial, but has so far stopped short of government procurement.

The NCSC does publish a research problem book[footnote 9] where they describe what they see as the most significant problems that should be the focus of R&D. Some participants suggested using the NCSC more in pre-commercial problem co-creation, modelled on programmes such as His Majesty’s Government Communications Centre (HMGCC) co-creation model [footnote 10] and with funding investment from the British Business Bank much like the National Security Strategic Investment Fund (NSSIF)[footnote 11].

From the NSSIF website: ‘NSSIF invests commercially, alongside other investors, in innovative startups, whose advanced dual-use technologies have potential applications both in the private sector and in the National Security and Defence community. This is done through direct investments where there is a strong strategic case, and investment into aligned venture capital funds.’

Participants liked this combination of government investment and convening, and they expressed enthusiasm for the idea of CISOs or other leaders with budgets from large organisations bringing cyber problems to similar programmes not restricted to national security. These kinds of convening models have been attempted before, but it remains a challenge to bring in the demand side in ways that lead to opportunities to validate problems and solutions.

Case study: The Jericho Forum

The Jericho Forum was a group of largely UK based CISOs that formed in 2002 to highlight that securing business and working practices by enforcing network boundaries was becoming increasingly difficult and less effective. They successfully argued for a ‘de-perimeterised security model’ to secure data and systems regardless of network location. This laid the groundwork for ‘Zero Trust’ architecture, which assumes no implicit trust based on network location and instead focuses on verification of assets and users [footnote 12] [footnote 13].

The Jericho Forum is an example of anticipatory demand-led thinking and acting as ‘one team’. It brought together UK customers and security leaders to collaborate, validate, and advocate for new approaches – demonstrating how user-led communities can shape global standards. It is a reminder that to compete globally the UK security community needs the strong input of UK customers to collaborate, validate and promote UK solutions.

Participants highlighted that for deeper impact on cyber security innovation, there is benefit in regular ‘upstream’ meetings, between potential future suppliers and those managing cyber teams and functions, taking place before any procurement is undertaken. Participants told us that it can be difficult for CISOs that don’t hold innovation budgets to prioritise time and investment in innovation. It was suggested that giving this group the opportunity to use funds to support innovation in their environment could be attractive.

While departments may struggle to find money for cyber growth and the HMGCC and NSSIF models offer some cyber opportunities, it was suggested that UKRI and the British Business Bank should identify funding to support pre-procurement work. This would help cyber businesses navigate government and commercial opportunities to address genuine demand-side needs without running out of cash on the way.

Growth challenges exist at all stages. Scaleups need help setting up processes and acquiring talent, medium sized businesses can get caught with the levels of bureaucracy of large businesses, many highlighted the value of the Department for Business and Trade (DBT) in supporting business development and exports. There are challenges with sovereignty and there is always the challenge of competing with or integrating into the wider cyber ecosystem[footnote 14]. This is an end-to-end problem with significant further attention warranted to create a larger funnel of ‘picked winners’.

Recommendation 1 – Support growth journeys

Government and industry stakeholders should review the incentives and validation routes available to cyber businesses.

The goal is to make it easier for cyber businesses to navigate the complexity of meeting cyber demand and to shift the culture to one that selects and helps winners to grow.

The following suggestions[footnote 15] are aligned with to support growth journeys.

Suggestion 1. Pilot programmes that allow NCSC and DSIT to qualify and connect cyber startups with government departments

NCSC and DSIT should be allowed to explore ambitious and experimental ways of reforming procurement, linking early-stage R&D opportunities to commercial tenders in more mature settings. This could be a joined-up government effort to use NCSC to qualify the technical credentials of cyber businesses, DSIT to connect them to departments, and to work with procurement and departments on the value for money and incentives to make this work.

Suggestion 2. Expand the co-creation and government investment models for wider commercial participation

The NSSIF funding model and HMGCC co-creation model should serve as examples for convening and funding cyber ideas. Place-based leadership should seek to use this to incentivise startup and CISO involvement in pre-procurement workshops on problem co-creation with the NCSC.

2.2. Developing the UK cyber workforce

Most participants highlighted skills as a major challenge. As one participant put it ‘there is no point mandating higher standards of security if most organisations do not have the knowledge or capacity to meet them’.

2.2.1. Cyber in schools

Many participants highlighted that cyber skills education needs to start early, in schools. Cyber First[footnote 16],[footnote 17] has been effective in enhancing cyber security awareness and providing learning experiences for students [footnote 18]. Building on its success the government has recently announced Tech First, expanding the scope of the programme to include digital skills more broadly[footnote 19]. Going forward, challenges for this programme include ensuring cyber is well integrated into emerging technology programmes (such as AI), on preserving the distinctive parts of the Cyber First programme, and building the capacity to deliver training more consistently. Tech First is a good step, but we also need to move beyond ‘bolt-on’ solutions to education if the UK is to keep pace with other countries that are building informatics programmes[footnote 20] or otherwise prioritising technical education [footnote 21].

Beyond technical skills, it is also important to engage young people in understanding what cyber is. This should align with and support initiatives to help children with online safety such as the refresh of the Online Safety Act and programmes like Digital Compass [footnote 22].

2.2.2 Entry points to cyber security jobs

Participants said that although many people would like to move into cyber roles, there are not many openings, especially for entry level roles. This is supported by data from the DSIT cyber skills 2025 survey [footnote 23]. On the one hand, the survey reports a 20% increase in cyber graduates in the most recent available data (2021/22 to 2022/23 academic years) and a finding that 49% of businesses have cyber skills gaps in a basic technical area in 2024. On the other, it shows core cyber job postings decreasing by 33% between 2023 and 2024.

This discrepancy between the skills gap and apparently decreasing demand for cyber could be explained in several ways. First, the ONS data shows a steady fall in vacancies across the UK since 2022[footnote 24]. Alternatively, it could also relate to whether the UK culture as represented by state, industry, and civil society, is sufficiently engaged in how cyber contributes to people’s lives and how sectors prioritise cyber resilience as a core part of their operations. Regardless of the explanation for a decrease in cyber security job openings, the data highlights that if more organisations were to prioritise cyber resilience, there is a talent pool ready and willing to step into roles. This is consistent with the positive impact seen when Cyber Essentials was mandated in defence procurement, which has built capability and created jobs in small businesses[footnote 25].

2.2.3 Cyber security as a profession

The Cyber Security Council and numerous membership organisations continue to develop cyber security as a profession, with pathways, specialisms, and accredited qualifications. Maintaining a register of security professionals will become even more important, but also challenging to keep current as cyber grows in complexity, both with emerging technology and its relationship to business risk and resilience.

Many participants highlighted the critical and challenging role played by CISOs. Whether they sit in the IT department or on an organisation’s board, the challenge is often how to ensure shared understanding and appropriate accountability for cyber risks. Participants said both that ‘we need more business leaders with better understanding of cyber’, and conversely ‘we need more cyber leaders with better understanding of the operational risks for business’, reflecting that in some cases not being able to talk about business risk means that cyber expertise is not ‘in the room’.

Participants noted that the NCSC Board Toolkit[footnote 26] is a valuable resource for facilitating strategic discussions between boards and CISOs. However, they also highlighted that the role of the CISO varies significantly depending on the organisation’s size and sector.

2.2.4 Equipping cyber entrepreneurs

From category creation and enterprise sales to building teams to validate, pivot and fail fast, starting businesses takes a lot of entrepreneurial drive and skill. Building cyber products requires knowledge of the priorities of customers and the threats they face

Programmes like Cyber Runway[footnote 27] and CyberASAP[footnote 28] play an important role in broadening skills for would be founders. The valuable secondary effects of connecting people through programmes like Cyber Accelerators[footnote 29] LORCA[footnote 30] and CyLon[footnote 31] were highlighted positively by participants.

Participants said that the UK has strong technical talent with many innovative ideas for cyber. However, there are only a small number of UK founders and investors who have experience of scaling businesses, and where they do, that experience is typically gained in the US. Several participants pointed out the value of events that allow more focussed convening between founders and customers looking to innovate in cyber[footnote 32]but also with the few UK people experienced in cyber security product management.

2.2.5 Supporting cyber growth leaders

UK cyber culture impacts business and investment choices too. Although some sectors and organisations do it well, it can be difficult to discuss how cyber impacts organisational risk. The danger is that cyber is siloed into IT, rather than being linked with operational, legal and financial risks that carry executive level accountability.

Similarly, cyber founders steeped in technology can struggle to communicate commercial value to investors. This was primarily expressed as the need to develop customer validation and enterprise sales skills and framings but also that UK funding is more steeped in traditional business cases as opposed to a ‘tech first’ category creation mindset more prevalent in US.

There were mixed views on recommendations here as the UK can’t simply adopt the culture and mindset of another country, but it was suggested that the UK needs to encourage more ambition and tolerance of failing fast and pivoting.

2.2.6 Shifting from a blame culture to a supportive culture

Participants reported that some cyber language can set the wrong tone. This included using phrases like ‘doing the basics’, which may downplay the complexity of maintaining best practices and fundamentals. There were also references to cyber having a ‘blame culture’ whereby employees and even victims face reprimand rather than support. This problem was related to the difficulties of sharing sensitive cyber information and was contrasted with safety industries (such as air travel) where sharing mistakes is culturally embedded and legally mandated.

2.3 Developing a UK cyber resilience mindset

2.3.1 Communicating the value of cyber for the UK’s prosperity

The UK cyber sector is shaped by the people, culture and values of the wider UK population. Beyond technical skills, there is the need to foster inclusive, society-wide conversations about the role of the cyber sector in UK prosperity – in schools, organisations, and civil society.

Unlike healthcare, education and policing, the role of cyber professionals is much less visible and often poorly understood by the public. This highlights the need to bring civil society into the cyber security conversations[footnote 33], and to ensure that engagement leaves people informed and invested in the role the sector plays in national resilience and prosperity[footnote 34].

Participants highlighted that while cyber incidents are analysed and discussed in the cyber community, less effort goes into sharing with the wider public how incident teams across sectors and government have responded to contain and recover from these events. This misses an opportunity with cyber leaders to bring to life in schools and the media the positive and critical role being played by cyber professionals and so develop wider interest and understanding.

Recent research flags the risk of ‘mystifying’ cyber security. This pertains primarily to the buyers of cyber in organisations but also, to some extent, to members of the public. Romanticising and mystifying the expertise of cyber professionals and attackers contributes to the separation of cyber from other domains, for example., making it less relatable to board members[footnote 35] Marketing strategies (such as duplicating naming systems for adversaries and malware used by cyber security companies) are commonly playing to the tropes of deviance and edginess, inducing fear and helplessness. This can happen at the expense of coordinating information on cyber crime[footnote 36].

2.3.2 The importance of actively engaged civil society

There were diverse inputs amongst the participants on how privacy, harms and resilience should be balanced, reflecting the very different views of the state, industry sectors and various parts of civil society. AI is currently challenging the norms for copyright and privacy in the digital realm[footnote 37] and cyber-physical systems bring more of the digital to the physical world, creating the need to harmonise cyber and physical safety best practice [footnote 38]. As technology advances, stakeholders will continually have to re-frame and re-negotiate their perspectives in a digitally integrated society.

Participants asserted that involving civil society is a matter of both cyber growth and cyber resilience. Cyber security products should reflect the diverse needs of their users not only as a matter of ethical responsibility, but because these users are also consumers of technology. The evidence base highlights recent progress on inclusive security design, e.g. for the survivors of domestic abuse seeking protection from spyware [footnote 39] or for visually impaired individuals relying on voice-controlled devices[footnote 40]. On a larger scale, public trust in institutions is essential for successful mass adoption of digital technologies, especially in publicly funded programmes[footnote 41]. If users feel excluded, targeted or inadequately protected, adoption stalls risking that intended public benefits of technologies will fail to materialise[footnote 42].

Recent research suggests that cyber security should be framed as a quest, ‘involving fundamentally optimistic, future-focused, and heroic plot centring around strong and collaborative leadership, individual and collective heroism, teamwork, and innovation (acknowledging that quests can also involve leadership contests, and internal rivalries)’[footnote 43]. It is important the people of the UK have an opportunity to express their needs in technology development, while gaining wider understanding of the contribution cyber makes to UK resilience. From business, state and civil society leaders to children and pensioners, the UK needs an informed and engaged community to give the sector skills and the mandate to navigate the changing risk landscape.

Case study: Cyber exercise in a box

Exercise in a Box[footnote 44] is a free, scenario-based tool developed by the NCSC to help organisations rehearse their response to common cyber threats in a safe environment.

Originally designed for small and medium-sized enterprises, local authorities, and public sector bodies, Exercise in a Box has been adopted to run tabletop exercises focused on threats such as ransomware, phishing, and videoconferencing attacks (e.g. ‘zoom bombing’). Participants are guided through realistic scenarios and prompted to discuss their preparedness, response strategies and gaps in policy or practice.

The accessible format of Exercise in a Box is particularly valuable for organisations with limited in-house cyber expertise and resources. Looking ahead, Exercise in a Box could be extended to the wider public by adapting content for community organisations and schools, offering tailored scenarios around personal data breaches, social media use, or smart home security. Tailored versions could also be distributed through public libraries, or digital inclusion programmes to build everyday cyber resilience across society[footnote 45]

- Language and mindsets

Many conversations highlighted how the cyber security sector is held back by misconceptions and stereotypes. Cyber often conjures up images of binary code flashing across screens in otherwise darkened rooms. Whereas cyber is actually a modern profession, requiring broad understanding of organisations, supply chains, people, technology and risks. Misunderstandings of the role of cyber in building strong and resilient businesses may put some people off the profession.

It has been suggested that we should start again with a complete rebrand. but the cyber community doesn’t control the use of the term ‘cyber’, it is already embedded in public discourse. Rather than arguing for new terms, the cyber community should focus on shifting how cyber is understood, emphasising its relevance to enabling the UK’s modern digital society.

The Cyber Security Sectoral Analysis 2025[footnote 46] identified that women make up just 17% of the cyber workforce. Participants connected this underrepresentation to misogynistic behaviour in workplaces and at large conferences, which often goes unchallenged. Others highlighted that the cyber industry often uses jargon laced with quasi-military language and glamourised names for adversaries, which creates fear, uncertainty, and doubt rather than the shared understanding and ‘buy-in’ needed for trusting relationships.

A tension here is that much of cyber is about contesting adversaries using offensive approaches. Training people to defend without ever trying to attack is a bit like learning to fight without an opponent. You can develop skills, but you are likely to be exposed when you face a real opponent. The UK needs to be comfortable developing offensive skills within regulatory frameworks defining legal and ethical uses of tactics like deception or breaking into systems. Ultimately, both offensive and defensive cyber security have a role to play in resilience and sectoral growth. As an example of the problem, one participant highlighted challenges businesses have selling ‘cyber deception’ even though it is considered an effective approach, since many customers are uncomfortable with the language.

Finding the balance is challenging, some participants highlighted the debates on the Computer Misuse Act (CMA)[footnote 47], which criminalises unauthorised use of computers. The Cyber Up campaign[footnote 48] highlighted the impact of uncertainty on crossing legal lines, meaning many are put off learning the skills needed, leaving the UK at a competitive disadvantage internationally.

For those dealing with cyber security issues regularly, the language is perhaps well suited to discussing the contested nature of digitalisation. It is important to be clear about organised criminals stealing and racketeering, about nations states (and pseudo state actors) spying and disrupting critical infrastructure, and how all this impacts economic prosperity and national security.

The participants were primarily members of the cyber community, which may be a biased sample. For the wider non-cyber community to have a say and stake in cyber growth and resilience, the sector needs language and framings that create an informed and unbiased debate.

Recommendation 3 – Foster public participation in cyber skills and growth

UK cyber professionals should engage with UK civil society on the sector’s role in national resilience and prosperity. This means emphasising the role cyber teams play in ‘keeping the lights on’ and the importance of skills initiatives from schools to professional development for cyber founders and leaders.

The goal is to build broader UK support for the role of cyber, making it easier for businesses to prioritise cyber, for people to learn cyber skills, and for the industry to attract, grow and maintain talent.

The implementation of Recommendation 3 requires inclusive language and engagement approaches to enable consultation beyond the cyber sector. As outlined in 2.2 there is also a need to focus on pathways to cyber careers and embed cyber skills and expertise in organisations– Include marginalised demographics in product development

Suggestion 3- Include marginalised demographics in product development

Cyber technologists developing products and services to engage with marginalised demographics e.g. via representative organisations such as Age UK for elderly people. This will enable better understanding of user’s product needs, whether as a business imperative or commitment to responsible innovation.

Suggestion 4- Convene ‘cyber in the public interest’ events

DSIT, cyber businesses and civil society organisations to convene a forum on developing cyber technologies in the public interest[footnote 49]. These could be modelled on similar efforts by the Finnish authorities[footnote 50]. The goal here is to co-create technologies developed in the public interest and prevent wasted public spending caused by low adoption rates or delays in technology rollout.

Suggestion 5- Use immersive methods to engage civil society

Leading third sector organisations and small business associations to adapt and use immersive methods (similar but not exclusive to the ‘Exercise in a box’) to engage civil society in the challenges and roles of cyber professionals.

Suggestion 6- Focus on the way cyber language is used with the public

From marketing departments advertising cyber conferences, Human Resources leads recruiting for new roles to journalists reporting on emerging incidents, everyone has a role in shaping the language we use. The cyber community should adopt language reflecting the positive role cyber security plays in wider society. This could be achieved in conjunction with commissioning studies on the role of language in engaging diverse communities.

Suggestion 7- Incentivise organisations to create cyber career entry roles

DSIT should consider introducing incentives to help organisations hire and train less experienced people in cyber roles. This could be through developing components of Tech First, apprenticeship schemes and graduate programmes. These incentives could be linked to policies for stimulating informed demand for cyber.

Suggestion 8- Double down on skills

Developing cyber skills needs to be embedded more deeply in more places. Building on the NCSC materials, cyber leaders (across DSIT, DBT, Department for Education, and regionally) need to keep supporting and communicating the value of all of the initiatives, from schools programmes and professional development to mentoring cyber founders.

Suggestion 9- Review the Computer Misuse Act

Recognising there is an enforcement challenge, the Government should review whether amendments to the Computer Misuse Act can be made to address the negative impact it has on skills development and broadening UK cyber growth and resilience.

3. Supply and demand

In an increasingly volatile geopolitical climate, market failures, cyber threats, and shifting alliances pose growing risks to national security and economic stability. In this context, organisations are facing resilience risks that may not be directly related to the priorities of their business. Identifying and addressing these risks and strengthening the demand for UK-based cyber security services and products is essential to ensure resilient digital infrastructures across all sectors, enhancing the nation’s sovereign capabilities, and enabling stable conditions for business and investment.

It is already well recognised that the cyber security supply sector contributes to the UK’s economic growth. It also serves a wider socio-economic purpose, producing ‘multiplier effects’[footnote 51] Namely, investment in the cyber sector drives job creation, innovation, improvements in the quality of products, and, ultimately, greater public trust in technology and institutions, helping to future-proof the UK economy in uncertain times.

This section reviews the characteristics of supply and demand for the cyber security industry in the UK, based on a brief market overview, a rapid review of published evidence and participant insights.

The ‘demand’ subsection focuses on two crucial challenges. First, mandating greater cyber security uptake among organisations often seen as ‘lagging behind’, such as supply chains to critical infrastructure, SMEs, and local authorities. In particular, Cyber Essentials has been identified as an important tool for improving resilience, and is an example of stimulating demand to create cyber growth[footnote 52]. Second, supporting UK-based cyber security SMEs, which frequently face barriers in selling products and services to government departments. Here, the report highlights the need for interventions in public procurement systems to stimulate demand for the domestic cyber security sector.

The ‘supply’ subsection addresses the pressing challenge of enhancing the availability of high-quality cyber security products and services, recognising that insufficient understanding among buyers contributes to lower market standards[footnote 53]. The report highlights recent initiatives calling for improvements to the assurance process to address this issue.

3.1 State of the sector supply and demand: facts and figures

-

In 2024 the UK cyber security products and services sector grew by 12% to £13.2 billion and the sector employed ~67,300 Full Time Equivalents (FTEs), up by 11% from the previous year[footnote 54]

-

The UK is home to 2165 active cyber businesses, just over half being micro-businesses56.

-

During 2024, £206 million investment was raised by dedicated cyber security businesses. This is less than recent years, but it is seen as a return to ‘pre-pandemic’ 2018-19 levels, rather than loss of investor confidence or engagement56.

-

The Cyber Essentials scheme has been in operation for over a decade, with a steady increase in uptake, and emerging evidence on its effectiveness. According to the NCSC report, 89% of Cyber Essentials-certified organisations would recommend the scheme and 69% believe it made them more competitive. The uptake of the scheme has seen an upward trajectory over the past several years, with over 33,000 certificates awarded in the past year, representing a 20% increase from the previous year. However, this still represents a fraction of businesses, as the UK is home to 5.5 million private businesses. Only 11% of organisations review cyber security risk in their supply chains[footnote 55].

-

Despite the rise in supply and demand for cyber, incidents are also more frequent. In 2024, the NCSC responded to 50% more nationally significant incidents compared to the previous year and reported a threefold increase in severe incidents[footnote 56].

-

The UK is the third largest exporter of security services and expertise worldwide with total value of exports approaching £11.0 billion in 2023. Security services include a range of technologies, e.g. fire equipment, managed services, personal protective equipment and others. Within that, cyber security was valued at £7.2 billion, an increase of 18% from 2022[footnote 57].

3.2. Stimulating demand and reducing burden

3.2.1 Mandating the fundamentals of cyber security

The majority of participants stated a clear need for UK organisations to strengthen their cyber security fundamentals, the core practices with the strongest evidence base for improving resilience. These include measures such as timely patching, implementing multi-factor authentication, and managing the attack surface effectively[footnote 58]. This need is particularly acute among SMEs, charities, and local authorities, which are often under-resourced and face significant challenges in maintaining robust cyber security.

Many participants spoke about Cyber Essentials and the role and future of this programme. Cyber Essentials has been described as a valuable, low-cost intervention that has helped to reduce vulnerabilities and lower incident rates, particularly benefiting smaller businesses when trying to gain access to some procurement frameworks. The evidence base suggests that Cyber Essentials controls could effectively mitigate most attacks during the initial phases but many organisations will require additional measures such as back-ups, security awareness training, logging and monitoring[footnote 59]. A major concern raised was the low uptake of Cyber Essentials among SMEs embedded in the supply chains of large organisations and critical infrastructures, thereby posing systemic risks to the nation’s cyber resilience.

Cyber risks are recognised as complex and distributed, with supply chain security identified as one of the most significant challenges. Addressing this requires a stronger mandate for cyber security improvements. Recent research highlights varied interpretations of ‘supply chains’, which has led to inconsistencies in the quantity and quality of guidance provided by national authorities and across sectors. This is further complicated by the absence of a shared taxonomy to support procurement and risk management[footnote 60].

Participants generally supported the idea of a Cyber Essentials refresh while highlighting the need for a precise intervention, rather than a major overhaul. They cautioned that mandating cyber requirements to all organisations could create barriers for smaller domestic businesses or discourage international companies from operating in the UK. In addition, the insufficiency of ‘checklist-based’ approaches could stagnate progress for more cyber-mature organisations.

Case study: Cyber Essentials stimulates resilience and growth

This report argues that stimulating demand will support the virtuous cycle of improving resilience of businesses, which will create confidence and growth for those businesses and in turn create growth for the cyber sector.

Based on the Cyber Essentials Impact Evaluation[footnote 61], there is evidence that Cyber Essentials improves the security posture and resilience of the businesses that adopt the scheme. There is also evidence that Cyber Essentials users encourage other businesses to adopt Cyber Essentials, thus broadening the impact on resilience. Quoting from the report:

‘There is evidence that Cyber Essentials is overcoming the information asymmetry around cyber security; furthermore, that the scheme is now making organisations able to consider cyber security as part of their purchasing decisions. For example, the majority of Cyber Essentials users (61%) say they are more likely to choose suppliers that are Cyber Essentials certified than those without certification, while three quarters (75%) say they have greater confidence working with certified suppliers.’

The scheme has a direct impact on growth of the cyber sector, which in turn feeds the virtuous cycle of wider capability and resilience.

‘The Cyber Essentials scheme is encouraging strong growth in the cyber security sector, with increasing numbers of Certification Bodies and assessors. This means a stronger external support network for cyber security should organisations need it for information or advice.’

And there is belief amongst those using Cyber Essentials that it helped with market competitiveness.

‘Finally, more than two thirds of Cyber Essentials users (69%) believe that Cyber Essentials has increased their market competitiveness. This includes certification being perceived as “achievable” which makes the cost-benefits clearer to see, gaining additional credibility since their organisation is taken more seriously, and experiencing increased commercial activity since becoming certified.’

And

‘Cyber Essentials evidently yields further commercial benefits considering that a third (33%) of contracts that Cyber Essentials users entered into over the preceding 12 months required them to be certified through the scheme and more than two thirds (69%) believe the scheme has increased their market competitiveness.’

Thus there are good grounds for believing that expanding Cyber Essentials and other changes that improve cyber risk management and engagement will stimulate demand and the virtuous cycle in the same way.

Participants were in a broad agreement that more emphasis should be placed on offering support in the face of the continuous nature of cyber security maintenance such as multi-factor authentication (MFA)[footnote 62] or patching. They also identified the need to help under resourced organisations with digital transformation more broadly, rather than solely focusing on cyber security. This comes from the appreciation that organisations are receptive to guidance when seeking to configure or update their digital infrastructures. However, it is important to bear in mind that these changes are usually prompted by a business need e.g. for communications, transactions, accounting, or client management and implemented via system integrators, rather than bespoke cyber security solutions.

Embedding security into products from the outset reflects the idea of ‘secure by design’, that is shifting the responsibility to software vendors to develop secure products[footnote 63]. According to the NCSC[footnote 64], security by design should be achieved through the combination of regulated standards (see the UK Product Security regime introduced in 2024[footnote 65]) and market incentives such as liability frameworks, financial reward, transparency, and consensus on security baselines.

Several participants talked about the complexity of complying to different regulations. Some pointed out the value of mapping standards or having fewer interfaces to have to deal with. While the NCSC and DSIT have already developed valuable mappings: across Internet of Things (IoT) product security[footnote 66]; and the Cyber Governance Code to the Cyber Assessment Framework[footnote 67]; several gaps remain. In particular, the alignment of the UK standards with the upcoming EU regulations and sector-specific mappings stand out as areas for improvement. Further to that, some participants pointed out that mapping could act as an intermediate step towards the wider international harmonisation of standards to reduce the burdens on organisations operating in both domestic and export markets.

Case study: Energy sector partnerships in supply chain cyber security

The adoption of The Security of Network and Information Systems Regulations (NIS Regulations)[footnote 68] was an early example of mandating cyber security improvements in the UK. For many critical infrastructure operators, it presented opportunity to build security teams, argue for investment in infrastructure upgrades and start a dialogue with regulatory bodies through the practitioner-led Communities of Interest[footnote 69]. Partnership work was deemed particularly helpful for supply chain security, which did explicitly not fall under NIS (2018).

One of the responses worth highlighting comes from the UK energy sector community who convened to develop the common cyber security procurement guidance and establish industry-wide dialogue with the supply chain[footnote 70]. This collaboration has improved standardisation in cyber security to the benefit of suppliers and operators alike.

Initially involving only operators and policymakers, the work expanded to include ‘validation’ discussions with key suppliers. These open conversations helped both sides understand procurement tensions and how cyber security requirements could be better delivered. Suppliers highlighted that some procurement processes inhibited honest cyber security discussions and stressed the need for shared responsibility. Operators emphasised that cyber security should be integral to proposals, not an optional extra.

The case study above shows the value of communities working together on adoption and best practices. Some participants highlighted other areas where guidance has been in development but not available and suggested it would help if ‘work in progress’ regulations and standards could be shared as early as possible to help communities to input and align with them.

Participants widely praised the introduction of the NCSC Boards Toolkit and ‘My Cyber’ SMEs Toolkit. However, the conversation about adopting ‘baseline’ cyber security improvement is still not sufficiently linked to businesses’ understanding of risks of cyber-attacks (e.g., financial, reputational and trust-related impacts). This gap is made worse by a wider accountability crisis at the board level, where IT failures (e.g., the Post Office scandal) are often poorly understood, downplayed, or blamed on technical teams rather than recognised as governance responsibilities. Some participants highlighted the problem of identifying where accountability should lie when regulation fails, although there were no simple solutions here. Despite the fact that material cyber risks are already subject to disclosure obligations, participants questioned whether stronger expectations or guidance are needed, given the growing threat landscape. This is not about reporting cyber incidents, but about highlighting for investors or other stakeholders, where cyber may impact the business and the steps being taken to manage and mitigate those risks. The evidence[footnote 71] suggests many are highlighting cyber risk, but there is a prevalence of low-quality reporting that lacks detail. Clearer guidance and expectations are needed to raise the quality of corporate cyber reporting. Overall, recent research argues that the cyber security market can be characterised as a failure of a ‘merit-good’, that is a public good that is not consumed optimally if left solely in the hands of the market[footnote 72]. This analysis leads to the following recommendation to stimulate informed demand through guidance, regulation and assurance.

Recommendation 2 – Stimulate informed demand

Government should use guidance and regulations to stimulate growth by setting expectations for high quality reporting of cyber risks, consulting on mandating the use of Cyber Essentials, and encouraging usage of cyber insurance and principle-based assurance.

The goal is to encourage organisations across sectors to prioritise cyber security in alignment with their organisational risks, thereby reducing incidents, increasing resilience, supporting broader economic growth, and driving demand for more UK cyber services.

Implementing this recommendation will require understanding of the implications for stakeholders and a phased approach to change as outlined in the following suggestions.

Suggestion 10- Mandate Cyber Essentials in selected supply chains

DSIT and CISOs representative of critical or otherwise relevant sectors should agree on key controls to mandate across supply chains, starting with Cyber Essentials. A phased approach should embed these requirements into procurement frameworks for government departments, critical infrastructure, and large businesses. Over time, alignment with standards like NIST SP 800-161 should be considered. As the scheme evolves, NCSC should lead on building the evidence base for its effectiveness, working with academic and insurance sector experts.

Suggestion 11- Map standards and regulations to help navigate compliance

NCSC, DSIT and DBT to continue their mapping and harmonisation efforts, prioritising international alignment and communication to organisations with significant export markets.

Suggestion 12- Share guidance early to reduce burden

NCSC to share emerging cyber guidance early to help communities anticipate and share best practices and deal with overlaps and gaps. This could be particularly valuable for critical infrastructure operators whose budgets are regulated through long-term funding cycles and currently lack alignment with the updates of the Cyber Assessment Framework.

Suggestion 13- Improve guidance on the reporting of cyber risk

Government should seek evidence and develop proposals on the quality of corporate reporting on what cyber risks exist for a business and how they are managed. The evolving proposals should help businesses tighten the connections between cyber risks and the material risks they are obliged to report on.

3.2.2. Facilitating SMEs access to government procurement

Participants characterised difficulties in accessing government procurement frameworks as a long-standing barrier to UK-based cyber security SMEs with potential innovations and solutions. In particular, the following challenges persist:

-

the procurement process is too slow to work with the ‘time to market’ pressures faced by SMEs;

-

procurement teams are mainly motivated by price and compliance at the expense of product fit. If ‘product fit’ is ever considered, it is usually limited to short-term requirements;

-

buyers in government can lack domain expertise to select the best quality products;

-

buyers rarely ask for product roadmaps or look at longer term solution fit;

-

among buyers, there is insufficient knowledge sharing with regards to the solution efficacy.

A widely shared view among participants is that the UK Government, as a cyber security buyer, could do more to engage and support the domestic cyber security sector. Current procurement practices often favour large systems integrators, creating structural barriers that disadvantage smaller specialist cyber security businesses. A few examples of good practice in pre-procurement activities should be highlighted, e.g. the industry days[footnote 73] held by the Ministry of Defence. However, the existing procurement environment diminishes incentives for entrepreneurial innovation and risks entrenching incumbents, potentially undermining both market dynamism and national cyber resilience.

While policy efforts exist to broaden SMEs participation[footnote 74], practical challenges in procurement processes and risk management continue to limit meaningful access for newer entrants. Likewise, recent research argues that government buyers, especially in under resourced organisations, such as local authorities, should receive structured support to be able to confidently buy digital technologies in the public interest[footnote 75].

One opportunity for improvement highlighted by participants was adding meaningful weight to factors related to cyber security in the procurement decision frameworks, a suggestion inspired by the recent Industrial Strategy which states the intent of ‘using government’s procurement power to create good quality local jobs and boost skills by streamlining and strengthening criteria for suppliers to contribute to these objectives in their bids’[footnote 76]. While the reform introduced in the Procurement Act (2023) is a step in the right direction, some participants expressed an appetite for more radical and experimental solutions. For example, the government of Canada runs ‘Innovative Solutions’ programme providing both early-stage funding and linked-up procurement opportunities[footnote 77].

Suggestion 14- Support pre-procurement engagement for SMEs

The UK Government (Crown Commercial Services) and innovation incubators (for example but not limited to programmes such as Cyber Runway) should implement formal pre-engagement mechanisms to help SMEs showcase their cyber security solutions and educate procurement teams ahead of tender processes. This could include regular market engagement days, innovation showcases, and technical briefings specifically aimed at introducing SME capabilities to public sector buyers.

3.3 Assuring supply with transparency and quality

A review of evidence as well as participant input identifies regulations (e.g. NIS Regulations[footnote 78]) and perceptions of crisis, for example attacks on retailers in early 2025[footnote 79], as two main factors stimulating demand[footnote 80].[footnote 81] However, the rise in demand for cyber security solutions doesn’t automatically translate into a boost in cyber resilience. This is because both cases can create a poor information environment for adequate judgement of product quality and relevant risks. Buyers of cyber security are rarely driven by independent analysis, instead, the cyber security market is primarily based on interpersonal relationships as well as ‘Fear, Uncertainty and Doubts’ sales tactics[footnote 82]. Put simply, growing the cyber security industry without ensuring product quality would be a risky strategy for the country.

Researchers and participants characterise the problem as a market failure of information asymmetry between vendors and buyers[footnote 83]. This ‘market failure’ is characterised by poor information availability among the potential buyers of cyber, driving down the overall product quality on the market. As a result, cyber security products may lack efficacy, including the capability to deliver the security mission (fit-for-purpose), practicality in operations (fit-for-use), quality of security build and architecture, and provenance of the vendor and supply chain[footnote 84].

Case study: Principles Based Assurance

A growing consensus among the cyber practitioners is the need improve demand side literacy: ‘We require informed demand’. Product assurance is an emerging solution for this problem and is receiving growing adoption within the cyber security sector.

One development worth highlighting is the NCSC’s Principles Based Assurance (PBA)[footnote 85]. This emerging approach assesses security against high level, outcome focused principles rather than rigid technical checklists. To deliver this methodology the NCSC is setting up Cyber Resilience Test Facilities (CRTFs)[footnote 86] aligned with the Software Security Code of Practice[footnote 87], ensuring products are secure by design.

PBA encourages organisations to adopt proportionate, flexible and context driven security measures aligned with their specific risks and operational environments. Instead of prescribing exact solutions, the model supports innovation, scalability and adaptability.

This approach is a tool for risk owners to gain confidence in the products they are deploying. It could give a vendor a badge of ‘cyber quality’ which could help them sell. But there needs to be demand from the buyers.

Recent exploratory research recommended that the NCSC develop sociotechnical expertise in assurance communication to better align the perspectives of buyers and vendors[footnote 88]. If implemented effectively, PBA could help overcome checklist and audit fatigue by encouraging security buyers to continuously improve and reflect on the state of their digital infrastructures.

This analysis and input led to the following implementation suggestion for.

Suggestion 15- Accelerate the development of Principles Based Assurance

Accelerate adoption of the Principles Based Assurance in codes of practice and development of appropriate assessment facilities. This action will need pre-engagement activities and incentives between vendors and buyers, to make it real, and so should involve DSIT and the NCSC, and be supported by evidence from the academic leaders (e.g. Research Institute for Sociotechnical Cyber Security).

4. Places

Many participants suggested that organising the sector around places would facilitate cyber growth and, as explained below, foster teams that may be able to respond to future crises in a more agile way. The UK already has 18 cyber clusters who collaborate through the UK Cyber Cluster Collaboration (UKC3)[footnote 89]. The cyber clusters are regionally based and focus mainly on the supply side. A different approach is required and should be based on a smaller number of places that combine multiple regions and unite the supply and demand sides. Strong leadership is a prerequisite for such places to succeed and is addressed below.

In this section, the evidence collected from participants supports the argument for a small number of strategic places that support futures thinking, nurture chosen technical areas and provide safe environments for experimentation and the development of novel solutions. The NCSC has a role to play in supporting this activity.

Many participants supported the selection of a small number of places to focus on developing a new generation of innovative cyber technologies, whilst recognising that this might exclude a large part of the cyber security talent. To mitigate this risk, it is important that such places work in a super-regional way: if a place is selected in the South West of England, it must also incorporate South Wales and, similarly, a place in the North West of England must incorporate the North East too. Moreover, participants highlighted the need for national coordination between places. Such coordination could be provided by the UK Cyber Growth Leader role (suggested by several participants) or possibly through an organisation such as the Digital Catapult. This input is behind Recommendation 5 – Appoint growth leaders in places of cyber strength.

Whilst non-UK investors may see the UK as a single entity, local groups of angel investors tend to concentrate on a place. Places are also essential for shaping research and development, and building the relationships that a people-centric business like cyber depends upon.

Participants confirmed that the UK is widely recognised as having world-leading strengths in areas such as secure-by-design, high-grade cryptography and software assurance and verification. The UK also has diverse strengths spanning capability in government and university research, to regional clusters and ecosystems around research centres, major tech companies and industries.

Different regions in the UK have different mixes of skills, infrastructure, university, government and commercially-driven innovation. Analysis of participants’ input suggests that the assets and organisations in a region are important, and that connectivity is essential for ‘getting innovations out there and used’. Many startups and spinouts, which can be good vehicles for rapid technology scaling, find their first customers within their local region. At the same time, the investment ecosystems in different regions are at very different levels of maturity.

Where regional markets are underdeveloped or fragmented, or where international markets offer greater scale, profitability, or access to specialised customer bases, businesses may choose to adopt an ‘export-first’ strategy, prioritising national or international markets early in their growth cycle, rather than relying solely on local demand.

Participants told us that this approach is already being taken by businesses in Northern Ireland, where a significant proportion of external sales were directed to Great Britain (GB), the Republic of Ireland (ROI), and the United States (US) due to limited local opportunities to support scaling. This highlighted the importance of external markets in sustaining growth for businesses operating in specialised niches that are too small to scale effectively within the region alone. In this context, participants noted that regional and devolved administrations infrastructure and expertise is still essential, in supporting export ambitions. Access to commercial skills, especially the ability to sell into international markets was also a key factor in their success.