National Security Strategy 2025: Security for the British People in a Dangerous World (HTML)

Updated 29 August 2025

CP 1338

PM Foreword

National Security is the first responsibility of any government, that never changes. But as the world changes, the way we discharge that responsibility must change with it. And the world has changed. Russian aggression menaces our continent. Strategic competition is intensifying. Extremist ideologies are on the rise. Technology is transforming the nature of both war and domestic security. Hostile state activity takes place on British soil. It is an era of radical uncertainty, and we must navigate it with agility, speed and a clear-eyed sense of the national interest. That is what keeping the British people safe demands. This document sets out our strategy.

We are guided by our values and our history. The United Kingdom is a founding member of NATO and I am immensely proud that it was a Labour government that played a role in its creation. We are a champion of collective security on our continent and beyond. Together with our allies, we have shown that strength remains the only effective response towards tyrants like Putin. And we stand unashamedly for freedom, democracy and internationalism.

In a world where these values come under attack, our resolve is even more important. Co-operation is in the national interest; our alliances must be deepened. This is why I have been so determined to repair the United Kingdom’s international standing. Our reputation as a stable partner was damaged by the previous government’s chaos. We have restored it because it is essential for our national security.

Yet from that great post-war period, we should also now recall three lessons that are fundamental to our national security today.

First, that foreign policy should answer directly to the concerns of working people. After all, the challenges we face already impact their lives. Wars drive up their bills. Cyber-attacks undermine their public services. Criminals smuggle illegal migrants across our borders. The lesson is clear: delivering my Plan for Change requires us to bring foreign and domestic policy together.

Second, that collective security, led by NATO, remains the cornerstone of our strategy. Our alliances remain robust, but for both their ongoing health and our own national interest we must now increase the sovereign strengths that underpin our national security.

Third, that nations are strongest when they are bound together by a shared purpose. One look at the world today shows the security challenges we face demand nothing less than national unity. Therefore, it is no longer enough merely to manage risks or react to new circumstances. We must also now mobilise every element of society towards a collective national effort.

That is the animating idea of this entire strategy – a hardening and sharpening of our approach. It means viewing higher living standards as an essential national security goal. It means restoring security to our borders as a crucial test of fairness and social cohesion. It means marshalling our comparative advantage in science and technology to create new opportunities for working people, as well as putting ourselves at the cutting edge of cyber defence. And it means we must strengthen our approach to domestic security, where threats continue to grow in their scale and complexity. Not just in terms of terrorism as traditionally understood, though that threat endures. Also, by strengthening our approach to the growing challenge of violence-fixated individuals and self-initiated terrorists.

However, perhaps the biggest implications of this strategic shift are for our national defence. Since coming to office, this government has responded to the generationally high threats to our security with the biggest sustained investment in our defence since the Cold War. Yet it is also clear that to keep up with our adversaries and strengthen the NATO alliance, we must go further still. That is why, as part of this strategy, we make a historic commitment to spend 5% of our GDP on national security by 2035.

We should view this as an opportunity. I have long argued that issues like energy security are vital for our national security. Meanwhile, investment in our wider economic resilience is clearly a crucial component of our defence, as well as our mission to deliver growth that improves the living standards of the British people. That is an argument made in our manifesto, in the recent Strategic Defence Review and which increasingly shapes the thinking of our NATO allies. So the United Kingdom, as it always has, will step up to meet its obligations to NATO. But just as important, we will use this pledge to renew our social contract.

I am convinced this can be done. We can unleash a ‘defence dividend’ that will renew industrial communities the length and breadth of our country. We can generate the jobs, growth and wages we need to bring the country together, guided by my Plan for Change. And we can unite society behind a simple argument that economic security is national security.

Strength on the international stage has always been vital for our national security. Now, we can use national security to strengthen our country.

Introduction

1. National security is the first responsibility of government and the foundation for our prosperity and way of life, along with secure borders and a stable economy. It means protecting the British people, promoting British interests and making the country stronger, more sovereign and more competitive in the long-term.

2. Protecting the UK and promoting British interests is becoming increasingly hard, however. Threats are proliferating. We are entering a period in which we are likely to face indirect and potentially direct confrontation with adversaries, the intensification of strategic competition – including the increasing salience of nuclear weapons in the policies, doctrines and approaches of our adversaries – and a radical renegotiation of the terms on which we cooperate with allies and other partners, with major implications for how and where we invest our resources.

3. The UK must therefore adapt its approach to national security in response to dramatic changes in the world around us, and to growing threats at home and in cyberspace. Decisions taken in the next few years – on illegal migration, the future of Ukraine, Euro-Atlantic security, the Middle East, the Indo-Pacific and in the fields of science and technology – have the potential to reverberate through the rest of this decade and beyond. Our ability to ensure public safety on our streets and online, defend our democracy and generate economic growth will be tested. So it is vital that we approach the coming years with a hard-headed understanding of the strategic context and clarity about what we are trying to achieve, and what we can achieve.

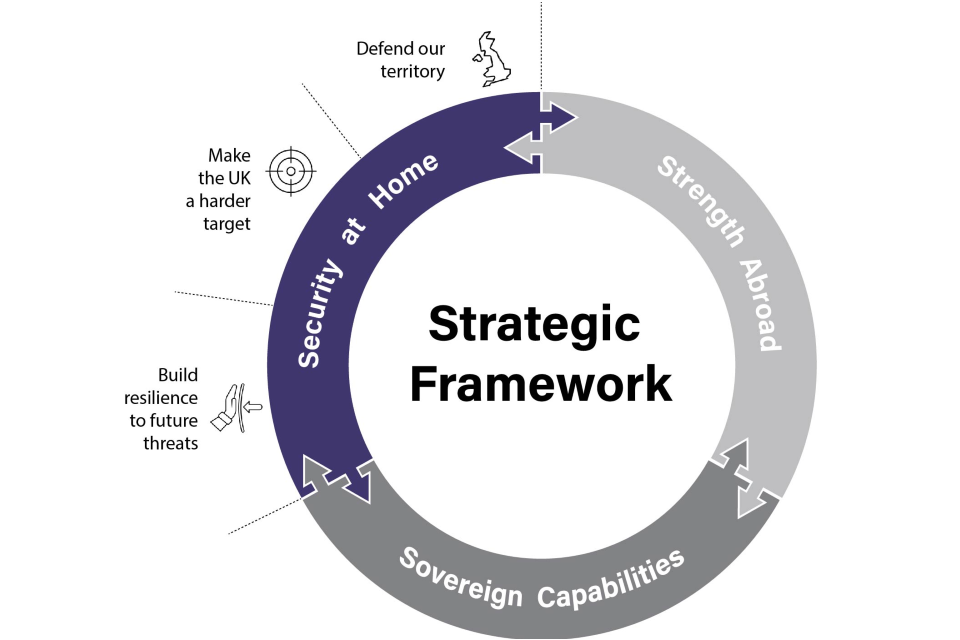

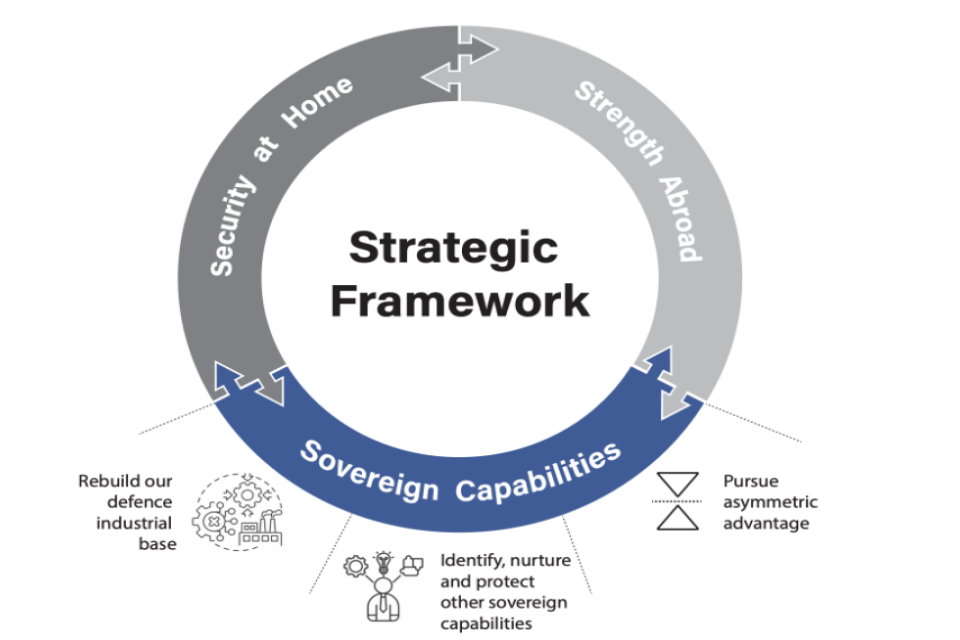

4. The purpose of National Security Strategy 2025: Security for the British People in a Dangerous World (NSS 2025) is: to identify the main challenges we face as a nation in an era of radical uncertainty; and to set out a new Strategic Framework in response, covering all aspects of national security and international policy. This includes three mutually reinforcing components: (i) security at home; (ii) strength abroad; and (iii) increased sovereign and asymmetric capabilities.

5. NSS 2025 brings together the various strands of work relating to national security that have been underway since the 2024 general election. This includes the Strategic Defence Review (SDR), Strategic Security Review, AUKUS Review, Resilience Strategy, China Audit, the Industrial and Trade Strategies and work on supply chains, intelligence assessment, development assistance, soft power, artificial intelligence (AI) and technological advantage. While recognising the uncertainty of the present moment and the need for continued adaptation, NSS 2025 is designed to last the duration of this Parliament.

6. This work takes on new significance because of our 2025 NATO Summit pledge - a historic commitment to spend 5% of GDP on national security. This is a generational increase in defence and security spending, underlining the UK’s commitment to national security and honouring our commitment to be a leader in NATO. As the second largest economy in Europe and the third largest in NATO, this will have a considerable impact on the strength of our alliance. The UK has long argued that NATO needs to focus more on national resilience as well as conventional military threats. We have set the foundations for a new era for defence in the SDR. But unless we do more to increase our competitiveness and sovereign strengths – in crucial areas like science and frontier technology – we will lose our ability to generate wealth and risk falling behind our adversaries. National security today means so much more than it used to – from the health of our economy, to food prices, to supply chains, from safety on the streets to the online world. And as we move to 5%, we need a plan for how we will maximise this opportunity to make our nation stronger. That is the purpose of NSS 2025.

7. Taken as a whole, NSS 2025 represents a hardening and a sharpening of our approach to national security across all areas of policy, already seen in a shift towards more investment in hard power and an emphasis on increasing the lethality of our armed forces. This needs to be accompanied by realism and frankness about the world in which we operate. The months and years ahead will see difficult compromises and trade-offs on resource allocation and prioritisation, short-term and long-term goals and, potentially, values and interests. We have already taken the difficult decision to cut spending on overseas development to allow us to increase investment in our armed forces. More tough choices can be expected as we head towards higher spending on defence and national security.

8. Against this backdrop, NSS 2025 therefore signals the need for a major cultural shift in government to help us navigate the new era in which we find ourselves. We will need to be more unapologetic and systematic in pursuit of our national interests. These interests will be defined as the long-term security and social and economic wellbeing of the British people.

9. It remains the case – as it has been for many decades – that British interests are best served by the preservation of international security and effective multilateral cooperation on issues from economic stability to energy policy. However, we must equally recognise that many people in the UK feel exposed to the negative effects of globalisation – such as de-industrialisation and mass migration – and see the rules being ignored, undermined or flouted by others, to their disadvantage. Answering such concerns will be at the forefront of our agenda. Meanwhile, we are entering a period in which we may have to act outside our comfort zone and take extraordinary steps if we are to strengthen our borders, deter and defend ourselves against threats, and achieve both technological advantage and our higher objectives of growth and renewal. In other words, multilateralism and institution building will not be enough. Our statecraft needs to adapt to a world in which there will be fiercer competition and a more transactional approach on migration, defence, trade, energy, technology and raw materials.

10. It follows that the starting point of the government’s approach to national security is to identify, anticipate, address and tackle risks to the British people and homeland (including the Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies). This threat-focused paradigm places particular importance on the role of our armed forces, intelligence, security and law enforcement agencies. The SDR has identified the most acute threat as that posed by Russia and prescribed a “NATO first” but not NATO-only plan for the modernisation of our military – with a more integrated, digitally-enabled and lethal force. The Strategic Security Review has identified the need to address a wide range of threats to domestic security – from terrorism, serious organised crime, and extremism to state threats – to which our responses are outlined in this document.

11. However, NSS 2025 is also clear that taking a defensive crouch – in which the primary activity is to manage risk – will not be sufficient to deliver on the government’s agenda, including the Plan for Change. Instead, as NSS 2025 lays out, we will adopt a campaigning approach to: minimise the ability of others to coerce us or undermine the foundations of our national strength; and maximise opportunities to enhance our security and prosperity, sometimes acting alone but mostly acting in concert with others. This will require ingenuity, creativity and calculated risk, as well as consistency, perseverance and effective implementation. It will be built around a long-term goal to build the necessary sovereign capabilities and competitive edge that ensures we take control of our own future in an uncertain world. As such, when we come out of this period of turbulence, the net assessment of our position should be that we are in a stronger position – economically, militarily, diplomatically and in terms of overall resilience and national well-being – with respect to adversaries and competitors than we were before.

12. There are important areas of continuity in NSS 2025 to stress at the outset. We will build on strong foundations in our armed forces, diplomatic service and intelligence, security and law enforcement agencies. Despite the persistent threat from terrorists and extremism, we have one of the best-regarded domestic security and counter-terrorism systems in the world, disrupting 43 late-stage terrorist attack plots between 2017 and 2024. We have a lattice-work of international partnerships and a seat at the table of global decision making, such as at the IMF and World Bank and through our permanent membership of the UN Security Council. Our highly skilled and admired diplomatic presence across the globe, with deep expertise in multilateralism, development and conflict resolution, helps us tackle challenges such as emerging security crises or mass migration. We remain committed to addressing the threats to our national security and economic prosperity from the climate and nature crisis. Alongside our international partners, we are taking action to deliver secure energy, financial security and green growth at home, restoring the UK’s position as a climate leader on the world stage. Our relationships with the US and Europe will be our priority focus, as they have been historically. We will continue to abide by the important principle – shared by NATO and its key partners – that the security of the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific regions are inextricably linked. We will maintain our major capability programmes such as AUKUS and Global Combat Air Programme (GCAP) and our partnerships in economically vibrant and geopolitically important regions like the Gulf and Asia. We will cultivate existing national strengths across the Union, such as our soft power and cultural reach and our financial, services, science and technology, energy and higher education sectors.

13. However, there are a number of distinguishing characteristics to NSS 2025 that show how we are hardening and sharpening our methods, while breaking new ground from previous national security reviews. A shift to 5% of GDP on national security requires us to align our national security objectives and plans for economic growth in a way not seen since 1945. Therefore, the essence of our approach will be: to harness the nation’s productive, industrial, technological and scientific strengths more closely to our national security objectives to an extent not seen since wartime; and to do more to answer the concerns of everyday British working people through a more systematic approach to pursuing national interests. That will start at home with new measures to make the UK a harder target for adversaries and criminals, accepting that we cannot stop every hostile actor. From that basis, our foremost mission beyond our shores will be to revise and reforge our collective security arrangements – starting with the Euro-Atlantic, strengthening NATO with new burden-sharing arrangements and fortifying Ukraine – to achieve long-term deterrence against adversaries. As part of this, and to spur more economic growth, we will: pursue greater strategic depth in our key alliances, from security to trade to deepening technological and nuclear cooperation; build resilience into our defence industrial base; and introduce a new emphasis on developing sovereign capabilities and asymmetric advantage as a nation, from innovation in frontier technologies to nuclear-powered submarines.

14. In support of this new approach, we will:

- Expand our legal and law enforcement toolkit, to ensure the UK becomes a harder target for hostile state and non-state actors including criminal gangs engaged in illegal migration.

- Roll out a series of new measures to strengthen our borders, defend our territory and enhance the resilience of our critical national infrastructure, ranging from enhanced defence of our island territory to stronger upstream measures and cyber capabilities.

- Deliver the largest sustained investment in our armed forces since the Cold War, with an emphasis on greater lethality, warfighting readiness, deeper stockpiles of munitions and innovation in, and adoption of, new technologies.

- Introduce an explicit prioritisation of NATO in our defence planning as part of our efforts to bolster collective security, alongside the delivery of major capabilities like AUKUS and GCAP that complement but are not tied to NATO alone.

- Place a new premium on the “defence dividend” for the UK – translating increased investment into more British jobs, skills and a stronger and more resilient defence industrial base, supported by major procurement reforms.

- Pursue both a deeper trade, technology and security deal with the United States and a closer economic and strategic partnership with the European Union, going further than the agreements we have already struck and supporting our objective of achieving greater strategic depth with key allies.

- Sharpen our diplomatic focus on countries that are geographically dispersed but economically vibrant and technologically advanced – particularly those (from Canada through the Gulf States, to India, Indonesia, Singapore, Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand) who are interested in cooperation on trade and security, sit outside large regulatory blocs and share a similar interest in shaping international norms to mitigate and manage the effects of great power competition.

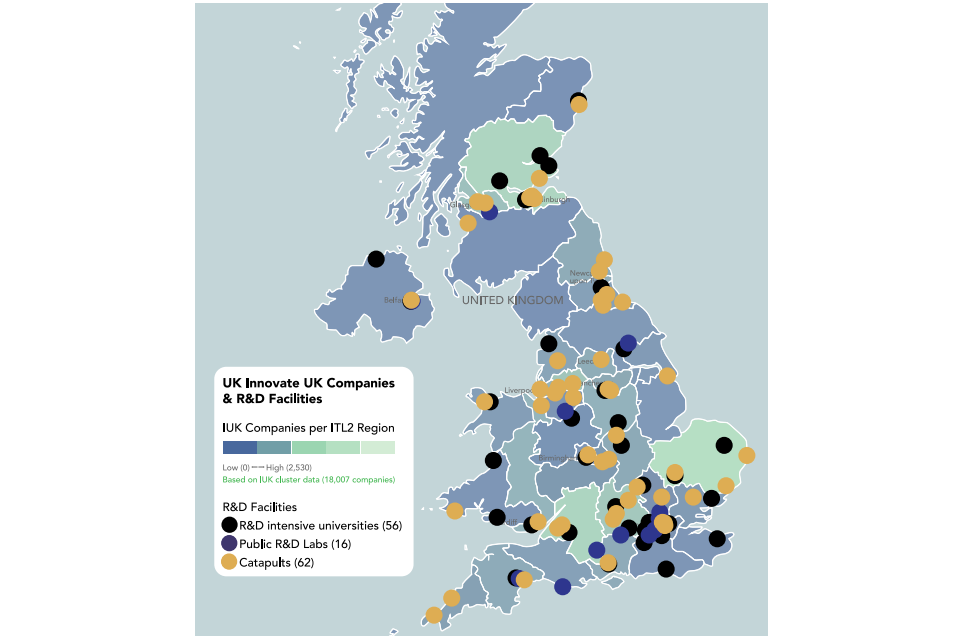

- Identify, nurture and protect sovereign areas of strength in the UK’s industrial, scientific and technological base with the explicit goals of improving our knowledge and research base, enhancing economic security, achieving breakthroughs or leads in key sectors, boosting our economy and enhancing our leverage within a broader international ecosystem.

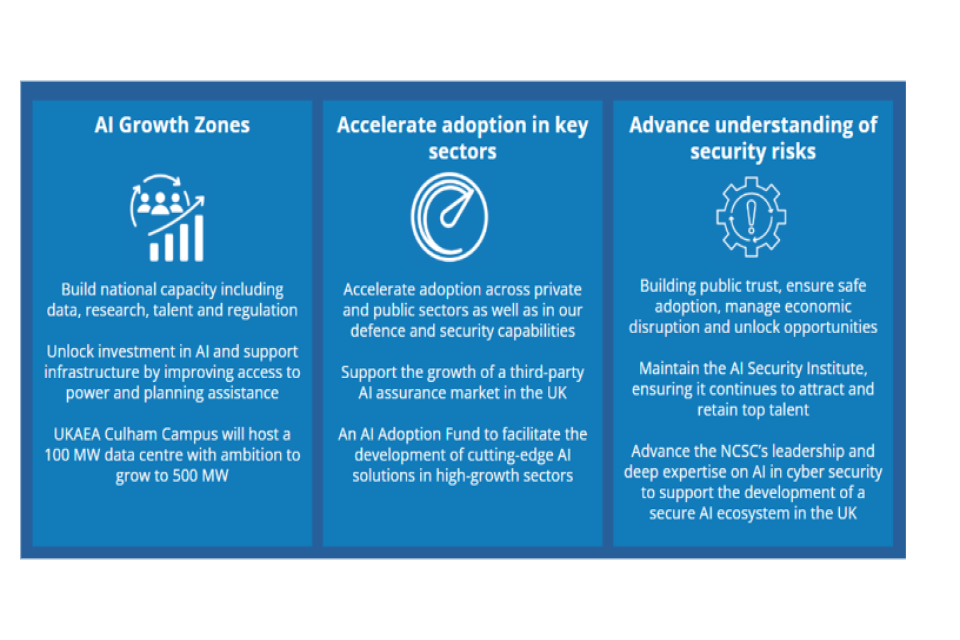

- Build the UK national security agenda for AI and other frontier technologies around three pillars: creating more national capacity (including data, research, investment, talent and regulation); accelerating adoption in key sectors; and advancing understanding of the national security risks.

15. Bringing this together, we will seek to partner with all parts of society, business, academia, and devolved and local governments in a new national resilience effort on the journey to 5%. This process starts with building greater public awareness of the threats we face, outlined in the Strategic Context that follows, and builds towards a new social contract between government and the British people, spanning every corner of England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

The Strategic Context: Navigating an era of radical uncertainty

1. We are entering a new era that will be characterised by radical uncertainty. The international order is being reshaped by an intensification of great power competition, authoritarian aggression and extremist ideologies. It is unclear when a more stable equilibrium will emerge and on what terms it will be governed. There is the very real prospect of even greater geopolitical volatility and exposure to economic shocks, exacerbated by technological changes and other persistent transnational threats.

2. In the years ahead, countries will become more assertive in pursuing their own goals and more willing to generate and exercise state power in pursuit of their vital interests. This will manifest itself in fiercer competition for resources, military modernisation, technological competition, economic coercion, increased hybrid threats and the more frequent testing of international norms and boundaries by major powers – as we have seen in Europe, the Middle East, Africa, Asia and the Pacific region in recent years.

3. Many of the rules which have governed the international system in the past are eroding. Global commons are being contested by major powers like China and Russia, seeking to establish control and secure resources in outer space, cyberspace, the deep sea, and at the Arctic and Antarctic poles. There will be less scope for agreement on mechanisms which protect fair trade, set controls on science and technological developments and mitigate the effects of climate change, as multilateral institutions decline in influence.

4. The foundations of strategic stability are being challenged. The threat to the UK and our allies from nuclear weapons is once again growing. Tackling this challenge is likely to be more complex than it was even in the Cold War, with more states with more nuclear weapons, the further proliferation of nuclear and disruptive technology, and the failure of international arms control arrangements to keep pace.

5. The UK’s national security and growth objectives will be profoundly affected by tensions between the major powers and regulatory blocs on trade, technology and defence. The way we have traded in the past will have to be adapted as open economies outside these major blocs will face increasing protectionism, restrictions on free trade and limitations on access to resources. Economic coercion will become more common as other states weaponise trade or use export controls and supply chain dependencies to gain advantage.

6. Large global companies and small start-ups will play a significant role in this competition, particularly in the development of the scientific and technological capabilities that underpin states’ military and economic strength. For this reason the most successful of these companies are likely to exert increasing economic, political and societal influence. The relationship between the private sector and the state will become more important. Innovation will be fuelled by flows of venture capital, private equity and institutional investments (over which democratic states have less control than authoritarian regimes).

7. Transnational challenges may become more acute and are likely to exacerbate other national security challenges. We will have to contend with the effects of climate change and potential ecosystem collapse, biological threats, demographic shifts, continued urbanisation, threats to human health, slow economic growth, inequality, and competition for basic resources, including food and water. Increased migration and population displacement will continue to place pressure on borders, infrastructure and public services, and potentially increase distrust and disinformation.

8. Science and technology are becoming ever more important domains of strategic competition. Technological advancements, particularly in quantum computing, engineering biology and AI, will accelerate innovation and bring benefits to our prosperity, health, education and security. But it will also mean greater competition for sources of energy and critical minerals. The frontrunners in this competition could achieve technological predominance, especially if they can secure a first-adopter advantage in the most promising fields (such as transformative AI). The speed of innovation will mean international regulations, safety standards and law enforcement responses will struggle to keep pace. Countries will use many different levers to encourage the emergence of national champions at the frontier of AI and other critical technologies, building public-private partnerships with global players to ensure they can secure access to the best capabilities and seeking to gain advantage by influencing the development of digital technical standards.

9. Technology will also create new vulnerabilities and change the character of conflict. New chemical and biological weapons may be developed and proliferate. Hypersonic missiles and AI-enhanced systems will be supplemented by mass-produced, low sophistication capabilities like drones. Some of these technologies will be available to a wider range of threat actors, posing new challenges to traditional concepts of deterrence and escalation.

10. Threats to the homeland from state actors are increasing. The UK is directly threatened by hostile activities including assassination, intimidation, espionage, sabotage, cyber attacks and other forms of democratic interference. These have targeted our citizens, institutions, journalists, universities and businesses. Adversaries threaten societal cohesion and seek to erode public trust through the spread of disinformation, malign use of social media and stoking tensions between generations, genders and ethnic groups. Meanwhile, critical national infrastructure – including undersea cables, energy pipelines, transportation and logistics hubs – will continue to be a target. It may become more difficult to identify hostile state activity as they make use of terrorist and criminal groups as their proxies. Our reliance on data centres and other forms of digital infrastructure will also increase vulnerabilities to cyber attack.

11. The combined threat from terrorists, criminals and lone actors will evolve as instability overseas feeds radicalisation and extremism in the UK. Ungoverned spaces in the Middle East and North Africa will accentuate these challenges, along with illegal migration. Terrorism - from Islamist and Extreme Right Wing ideologies - will remain a persistent, and diversifying threat. Hybrid and tech-enabled methods are increasingly being used as part of the terrorist toolkit. The number of vulnerable young people who are desensitised, exploited and radicalised online is likely to increase, alongside more individuals who are fixated by extreme violence. This will be compounded by the proliferation of illegal activity and harmful content online and the use of end-to-end encryption which frustrates law enforcement efforts. Alongside this, organised crime will remain the most corrosive, day-to-day threat to most UK citizens, with new technologies lowering the barrier for entry and exacerbating illicit finance, cyber attacks and online fraud, cross-border drugs, child sexual abuse and human trafficking.

12. These trends in the national security context are likely to force difficult choices and dilemmas upon us within a very short time frame. They are also likely to manifest themselves as strategic challenges which are more pressing and severe than at any time in decades. These include: confrontation with adversaries (indirect and potentially direct); competition with other states (which will be both systematic and strategic in nature); and cooperation (which will become harder but arguably even more important than ever before).

Confrontation

13. We are in an era in which we face confrontation with those who are threatening our security. The most obvious and pressing example of this is Russia in its illegal war against a European neighbour. Ukrainians are paying the ultimate price as they find themselves at the frontline of this confrontation. This war has been accompanied with a campaign of indirect and sub-threshold activity – including cyber attacks and sabotage – by Russia against the UK and other NATO allies and the use of increased nuclear rhetoric in an attempt to constrain our decision making. Iranian hostile activity on British soil is also increasing, as part of the Iranian regime’s efforts to silence its critics abroad as well as directly threatening the UK. Meanwhile, some adversaries are laying the foundations for future conflict, positioning themselves to move quickly to cause major disruption to our energy and or supply chains, to deter us from standing up to their aggression. For the first time in many years, we have to actively prepare for the possibility of the UK homeland coming under direct threat, potentially in a wartime scenario.

14. The likelihood of contingencies in which we may be asked, or choose, to confront threats by the use of military force is growing. We have seen groups like the Houthis threaten the essential principle of freedom of navigation with attacks on civilian shipping in the Red Sea, as well as on the allied navies there to protect them (leading to UK military action). Elements of the UK’s armed forces have been shifted into a state of heightened readiness on a number of occasions in different theatres. Therefore, greater vigilance in all domains will be essential to continue to deter those who seek to undermine our territorial security, such as in monitoring and countering the activities of Russian surveillance vessels in British waters.

15. Warfare between major powers, an international security crisis, or a situation with multiple-contingencies across different regions, is an active possibility. Tensions between India and Pakistan have reached their highest levels for decades. The possibility of major confrontation in the Indo-Pacific continues to grow, with dangerous and destabilising Chinese activity threatening international security. We have seen direct military conflict between Israel and Iran. This follows years of aggressive and destabilising activity by the Iranian regime which has included activity specifically targeted against UK interests at home and overseas. Significant escalation in any of these theatres would have a profoundly negative impact on our energy security, the cost of living and our ability to grow our economy.

Competition

16. Alongside this period of confrontation, we and our allies are engaged in medium- to long-term systemic and strategic competition with those who do not share our values, have divergent interests, or have the capability to undermine our security and prosperity. This applies to every aspect of our domestic and foreign policy and not just traditional defence and security concerns. Just like in the era of the First and Second World Wars, in the next decade those nations that are able to harness productive power – and mobilise all their assets towards strategic objectives – will end up in a position of comparative advantage.

17. Authoritarian states are putting in place multi-year plans to out-compete liberal democracies in every domain, from military modernisation to science and technology development, from their economic models to the information space. Since 2022, for example, Russia has massively increased defence spending, not just to prosecute war against Ukraine but also to replenish its defence industrial base and threaten others in its neighbourhood. As the second largest economy in the world, with strong central government control, the challenge of competition from China – which ranges from military modernisation to an assertion of state power that encompasses economic, industrial, science and technology policy – has potentially huge consequences for the lives of British citizens.

18. A major feature of this competition is the willingness of adversaries and competitors to work more closely together. This is both strategic and opportunistic. North Korea not only threatens its neighbours in Asia through ballistic missile testing; it has sent thousands of troops to support Russia’s illegal war in Ukraine, directly confronting those seeking to preserve European security. Iran has delivered missiles and drones to Russia while China has helped Putin maintain his defence industrial base. As our adversaries and competitors engage in further military modernisation, issues like technology transfer and sanctions enforcement are going to become increasingly important.

Cooperation

19. In this period of rapid change and uncertainty, it will be more important than ever before that the UK has strong alliances. This remains a major source of our competitive strategic advantage. Traditionally our adversaries have been less effective at working within a coalition, with the trust and stability ensured by the types of decades-long alliances and partnerships we have built in groups like NATO, the G7, or Five Eyes.

20. Yet the assumptions underlying our alliances are undergoing a fundamental change – perhaps the most significant in 70 years. Alongside this, there is major re-balancing underway in the international system. The United States, in particular, has consistently made clear to European allies that they need to spend more on defence. Related to this, allies will need to further improve interoperability and the compatibility of their collective defence industrial base.

21. Transactionalism will increase in the years ahead, with states relying more on pragmatic bilateral deals and minilateral groupings to achieve their objectives. But working towards internationally-agreed regulation and norms, stewarded by institutions – will also remain vital. There will be opportunities to deepen strategic ties with traditional allies. At the same time, it may become more common to work more closely with those with different values where mutual interests are identified. Agility and flexibility will be crucial.

Strength Abroad

- Bolster collective security

- Renew and deepen our alliances

- Develop new relationships in new domains

Sovereign Capabilities

- Rebuild our defence industrial base

- Identify, nurture and protect other sovereign capabilities

- Pursue asymmetric advantage

Security at Home

- Build resilience to future threats

- Make the UK a harder target

- Defend our territory

Strategic Framework

This Framework sets out the overarching principles that will guide the UK’s response to the context set out in the previous section. The three pillars are mutually reinforcing. Security at home provides the essential foundation from which to project strength abroad and to nurture our unique national strengths. Working with others overseas is essential to our ability to protect people and grow our economy. Developing sovereign capabilities keeps us safe at home, boosts our economic productivity and increases our international influence.

(i) SECURITY AT HOME

- Defend our territory

- Make the UK a harder target

- Build resilience to future threats

(ii) STRENGTH ABROAD

- Bolster collective security

- Renew and refresh key alliances

- Develop new partnerships in new domains

(iii) INCREASE SOVEREIGN AND ASYMMETRIC CAPABILITIES

- Rebuild our defence industrial base

- Identify, nurture and protect other sovereign capabilities

- Pursue asymmetric advantage

Pillar (i) - Security at Home

- Security at Home

- Build resilience to future threats

- Make the UK a harder target

- Defend our territory

1. The first pillar of our Strategic Framework is to protect our people, bolster the security of our homeland and strengthen our borders against all types of threats, both in the physical and online space. Without security and resilience at home, we cannot deliver economic growth or any of the other government missions to improve the lives of the British people.

2. The vital work of the police and the security and intelligence agencies – often in the shadows, often in secret, and often at great personal danger – is indispensable in keeping our communities safe. But today’s hybrid, technology-enabled threat is testing their ability to operate safely, securely and covertly more than ever before. Hostile activity on British soil from countries like Russia and Iran is increasing, threatening our people, critical national infrastructure and prosperity. Illegal migration, enabled by criminal gangs, continues to cause strains on our public services and social fabric, including people’s perception of justice and fairness. Global terrorist groups pose a persistent and enduring threat - directing, projecting and enabling plots in the UK - while we also see increasing numbers of individuals with no fixed ideology who are violence-fixated, driven and enabled by the online environment. The combined and overlapping threats from state actors, terrorists and extremists, and organised criminals - magnified by technology – pose new and evolving risks to our economy, our democracy and our way of life.

3. These multiple and interconnected threats require us to make ourselves a harder target to our adversaries. As a first step, the defence of our borders and territorial waters must be strengthened. This will begin with an upstream approach, working with our international partners as part of a collective response to challenges like illegal migration. Second, we are taking new measures to frustrate and deny hostile actors who seek to take advantage of our openness as a democracy. As part of this, we must increase the cyber and economic security defences which are vital to our ability to achieve innovation and growth. Finally, we need to increase our preparations for potential threats on the horizon, from future pandemics to energy and supply chain disruption and climate-change induced threats to our food security.

Section (1) – Defend our territory

4. An island nation needs to be able to control its borders and maritime environment. Security at home requires monitoring and managing who and what enters our waters and airspace. The UK depends on subsea fibre optic cables for 99% of its digital communications and approximately three quarters of the UK’s total gas supply comes from subsea pipelines. Our territorial security therefore begins at sea – from our ability to stop criminal gangs and deter hostile states to the import of food and energy supplies.

Graphic Title: Fibre-optic subsea cables carry 99% of UK digital data

- 99% of UK international data traffic transmitted via subsea cables

- £65 bn of UK economic activity relies on the subsea cable industry including fibre optic cables

- Subsea cables provides 66 million Britons with access to the global internet

- The cost to repair a single damaged fibre optic cable is up to £1 m and £100 m for power cables per incident.

Map Telegeography; Joint Committee on the National Security Strategy (JCNSS); Huddersfield University: An Economic and Social Evaluation of the UK Subsea Cables Industry 2016; Data Reportal Digital 2025: The United Kingdom; International Cable Protection Committee: Damage to Submarine Cables from Damaged Anchors 2025

5. The Royal Navy will take a leading and coordinating role in securing undersea infrastructure and maritime traffic carrying the information, energy and goods upon which we depend. Under Operation Atlantic Bastion, we will counter the persistent and growing underwater threats from Russian submarines and the shadow fleet. Changes to our Rules of Engagement means our warships can now do more to track vessels we suspect of spying or conducting sabotage. Under UK leadership, the ten-nation Joint Expeditionary Force (JEF) is increasing efforts to track potential threats to subsea infrastructure and the Russian shadow fleet at its Operational headquarters in Northwood. Our NATO allies are also helping us defend our waters through the UK-hosted NATO Maritime Command, as well as Operation Baltic Sentry, which ensures Russian ships cannot operate in secrecy near UK or NATO territory.

6. Sovereignty over the Overseas Territories must be protected against all challenges so that, for those who live in the Territories as British nationals, their right of self-determination is upheld. The Overseas Territories provide the UK and our allies with strategically-located bases which support a wide range of security capabilities. We will maintain our military presence in Gibraltar, the Sovereign Base Areas of Akrotiri & Dhekelia, Ascension Island, the Falkland Islands and South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands to deliver UK defence objectives, and support the UK’s scientific presence in the British Antarctic Territory, whilst upholding the Antarctic Treaty system. The joint UK/US base on Diego Garcia will continue to play a key role in countering a wide range of threats from terrorism, piracy and hostile state activity. The government’s deal with Mauritius, supported by the US, will maintain full UK control over this vital base with robust security provisions, ensuring it can continue to operate as it has done, with legal certainty, well into the next century.

7. The UK border is a vital pillar of our security as a nation – protecting us from international threats, helping us uphold and enforce our domestic laws and allowing our citizens to go about their lives freely and confidently. Through the new Border Security Command, we have already invested over £150 million over two years into technology and specialist officers, including applying lessons from counter-terrorism and making full use of law enforcement and intelligence agency capabilities.

8. We are also investing in new technology to enable front line personnel to carry out more targeted interventions, and increase detections and seizures at the border. The introduction of Electronic Travel Authorisations allows us to prevent the travel of people known to pose a risk to the UK. We will leverage the UK visa system to drive cooperation with other countries on returns. This includes using powers to suspend the granting of visas to countries that are not cooperating on the return of their citizens. We will also make it easier to refuse entry or asylum to those who break our laws, by simplifying the rules and processes for deporting foreign national offenders.

9. Tackling organised immigration crime and cracking down on people smuggling requires partnerships with both source and transit countries, which is why we convened more than 50 countries and international organisations for the first major international summit to tackle organised immigration crime. Through the 2025 Calais Group Priority Plan – agreed with Germany, France, Belgium and the Netherlands – we have committed to enhancing law enforcement cooperation through Europol to tackle irregular migration and increase our border security. We have expanded our Joint Migration Taskforce with Albania and Kosovo to include North Macedonia, with plans to extend to Montenegro, and agreed a Joint Action plan to tackle human trafficking with Vietnam and a Border Security Pact with Iraq to target smuggling gangs.

Graphic title: Stopping criminal activity at UK borders

- 27, 026 kgs of class A drugs seized in 2023/24 at UK borders

- 2,593 firearms seized in 2023/24 at UK borders

- 16,770 referrals to support victims of modern slavery and human trafficking in 2023/24

Source: Border Force: Transparency Data Q1 2025; Home Office Modern Slavery: NRM and DtN Statistics, end of year summary 2024

Section (2) - Make the UK a harder target

10. The openness of our democracy and economy are national strengths. Therefore, it is vital to keep ahead of those who seek to exploit them with robust defences. While we will not be able to stop all threats to the UK, we are taking steps to make our country a harder operating environment for hostile actors.

11. The Foreign Influence Registration Scheme, introduced under the National Security Act 2023, is a critical tool. This will strengthen the resilience of the UK political system against covert foreign influence and provide greater assurance around the activities of designated foreign powers or entities where there is a national security risk. We have already placed both Russia and Iran on the enhanced tier of the scheme, meaning anyone working for those states in the UK – including criminal proxies – will need to declare their activities or risk prosecution and imprisonment. We have also used sanctions to dismantle the criminal networks and enablers that Iran uses to carry out its work.

12. We are committed to taking forward the recommendations of the Independent Reviewer of State Threat Legislation, and will draw up new powers - modelled on counter-terrorism - to tackle state threats. Counter Terrorism Policing will continue to investigate terrorist and state threat offences. We have also renewed the mandate of the Defending Democracy Taskforce, which will strengthen safeguards against individuals and companies acting as proxies for foreign donations.

13. It is vital that we keep adapting our national security systems in keeping with the persistent but changing threat from terrorism. The Counter Terrorism Operations Centre will continue to provide a single locus for the police, MI5, probation, other operational partners and Five Eyes allies to coordinate efforts to disrupt terrorist groups and prevent attacks. The new Terrorism (Protection of Premises) Act 2025, also commonly referred to as Martyn’s Law, will improve public safety and ensure we embed the lessons from the terrible Manchester Arena attack.

14. The awful attack in Southport exemplifies the growing threat from individuals who are fixated by extreme violence, seemingly for its own sake. Our response requires closer working across law enforcement, education, health and justice. We will review our legislative framework to consider a new offence for “acts preparatory” to “extreme violence”, for individuals who are identified as violence fixated.

15. Tackling tech-enabled harms in the online space is also central to managing threats including from terrorists and extremist violence. Through the Online Safety Act 2023 (OSA), providers of internet services are now required to take proportionate steps to make their services safe and protect users from illegal content. While the OSA provides us with tools to make services safer, particularly around terrorist content, there are significant challenges around tackling other violent and extremist content online. Government, law enforcement and service providers must find ways to tackle this kind of content, including working with and supporting Ofcom to maximise the levers within the OSA.

16. Coming into the UK – and taking part in our society – means living by the same rules as everyone else. We will not accept a situation in which conflicts or divisions that have their origins overseas are brought into our streets. The state will remove the platforms and privileges granted to anyone who abuses this fundamental principle. We will deny visas to those who seek to travel to the UK to spread discord in our communities, and harden our response to those abusing charitable status to peddle extremist viewpoints.

17. Cyber and economic security are becoming increasingly important to our ability to grow our businesses and go about our everyday life. But the essential services, infrastructure and digital services on which we rely are exposed to increasingly intense, frequent and sophisticated hostile cyber activity, such as ransomware. The National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) will continue to help empower businesses, the public sector and the public to protect themselves from cyber attacks, and to support response and recovery when incidents do occur.

18. More broadly, we are constantly adapting our methods to ensure we are a harder target to adversaries in the digital realm. This includes publishing a refreshed National Cyber Strategy and introducing a Cyber Security and Resilience Bill, setting out new legal powers and protections. The NCSC is working to support the public and private sector in the transition to post-quantum cryptography by 2035 and in responding to the challenge of quantum-enabled cyber threats.

19. The National Security and Investment Act 2021 and Investment Security Unit remain central to our approach to economic security. This brings together expertise from across government to review acquisitions and put in place mitigations to prevent investments harming our national security. We will also use the measures set out in the Telecommunications (Security) Act 2021 to protect public telecoms networks and services, and to mitigate the security threat posed by high-risk vendors.

20. All elements of our security are supported by our ability to tackle illicit finance – the flows of funds from criminal activity that underpin threats to the UK including terrorist networks, serious and organised crime groups, and hostile state actors. Our new Anti-Corruption Strategy will include measures to counter illicit finance, kleptocracy and corruption, domestically and internationally.

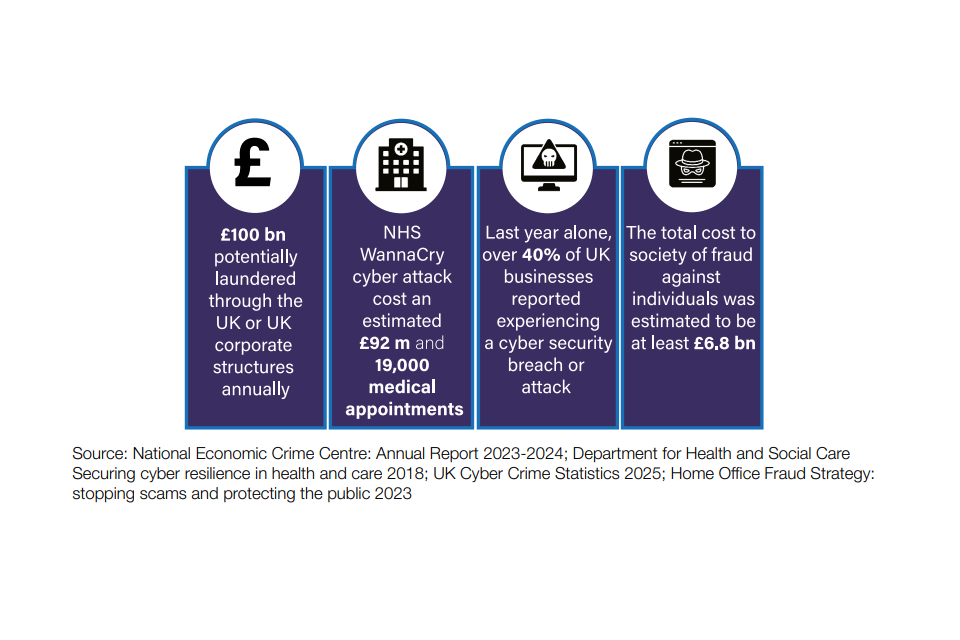

Graphic title: The cost of serious organised crime

- £100 bn potentially laundered through the UK or UK corporate structures annually

- NHS Wannacry Cyber Attack cost an estimated £92 m and 19,000 medical appointments

- Last year alone, over 40% of UK businesses reported experiencing a cyber security breach or attack

- The total cost to society of fraud against individuals was estimated to be at least £6.8 bn

Section (3) - Build resilience to future threats

21. NSS 2025 recognises the vital importance of long-term actions to build national resilience against external shocks or threats that could cause massive disruption to our way of life, including from the natural world. This requires us to reduce reliance on others – ensuring our supply chains, energy security and access to critical goods can be maintained even in times of crisis. It also means we must develop new measures to anticipate and prepare for risks that emerge from scientific or technological developments, such as in the fields of AI or biology, and which could interact with other threats to the UK.

22. The new Resilience Strategy will deepen our understanding of the UK’s current resilience levels, supporting civil society and the public sector to better address risks and vulnerabilities. This follows our commitment at the NATO Vilnius Summit to develop National Resilience Goals, NATO’s seven Baseline Requirements for resilience and Alliance-wide Resilience Objectives. The strategy will also launch public communications to inform citizens about preparedness for risks. This will be supported by the UK Resilience Academy’s training offer to all those across our society who play a vital role in our national resilience. As part of this, our plans for Home Defence will focus on the protection of critical national infrastructure and countering sabotage during a crisis (potentially modelled on the Reserves). We will also run annual National Exercises in order to test our whole-of-society preparedness.

23. We are establishing a new network of National Biosecurity Centres with investment of over £1 billion to bolster the UK’s defences against biological incidents, accidents and attacks. The forthcoming report on the Biological Security Strategy will set out the progress made in creating a new Biothreats Radar, a UK-wide Microbial Forensics Consortium and a National Action Plan on confronting Antimicrobial Resistance. We are also investing up to £520m in UK-based Diagnostic, Therapeutic and Vaccine manufacturing facilities, along with funding for High Containment Laboratory facilities.

24. The new Industrial, Trade and Critical Minerals Strategies will strengthen international collaboration to drive investment, increase access to finance, and improve government support and guidance for businesses to help them understand and mitigate risks. Our new Supply Chain Centre will review inputs, consider the impact of future trends on demand, and determine what action may be required - such as domestic capability building, diversification or strategic international partnerships to build resilience. Our Trade Strategy will set out further action to support businesses to strengthen their economic security.

25. Our energy security is vital to our national security, economic stability, the delivery of essential services and our ability to fuel new technological developments in fields such as AI. We are moving away from imported fossil fuels and towards electricity produced at home and by our allies. We have banned the import of oil or gas from Russia and are building a global uranium nuclear supply chain that is entirely free from Russian influence. We have also lifted the ban on onshore wind, consented to record amounts of solar power projects and continue to innovate and invest in other sources of renewable energy. Reducing energy prices remains a vital part of ensuring our nation’s ability to innovate and grow our economy. Alongside action to shore up our domestic energy security, we will work internationally to address the climate and nature crisis and the risks it poses to our national security, financial stability and green growth at home. Our Global Clean Power Alliance will maintain international momentum behind the transition to clean power, drive investment in emerging markets and developing economies, and enhance the resilience of clean energy supply chains, including for the UK. With partners, we are working to reform the global financial system so that it delivers the finance needed to tackle such global challenges.

Pillar (ii) - Strength Abroad

- Strength Abroad

- Bolster collective security

- Renew and deepen our alliances

- Develop new relationships in new domains

1. The second pillar of NSS 2025 is to achieve strength abroad by using (and combining) all the levers of state and national power including defence, diplomacy, trade, intelligence, law enforcement, science, technology, education and our cultural reach.

2. Our ability to achieve influence abroad will be more challenging in the next few years, with adversaries taking aggressive and concerted action against our interests. Our approach also needs to reflect the fact that some of our traditional allies are making changes to their international priorities in ways that will have major implications for us. Effective cooperation is going to increase in importance for our ability to deliver our objectives but will simultaneously be more challenging than it has been in the past. Our diplomacy and statecraft therefore needs to adapt to a more fluid and transactional world, in which economic and military measures will be more commonly used as means of leverage and bargaining.

3. In response, we will reinforce those parts of our approach to national security which have traditionally served us well, such as NATO, the G7 and Five Eyes. First, building on our historic approach, collective security will remain the foundation stone of our strategy to deter and defend against aggression. But this will require a major effort to restore stability and security to the Euro-Atlantic area as an overriding priority, beginning with our support of Ukraine. Second, we will seek to renew and then achieve greater strategic depth in our key alliances, starting with the US and EU, not only to bolster our security but also our prosperity and long-term competitiveness. Third, we will bring new creativity to our international partnerships, particularly in new domains of policy like technology. This involves a sharp focus and prioritisation of effort on those relationships that best allow us to deliver for our national interests at home. Finally, we will establish greater robustness and consistency in how we approach major strategic challenges such as the impact of China as a global actor.

Section (1) - Bolster collective security

“Meanwhile, we must face the facts as they are. Our task is not to make spectacular declarations, nor to use threats or intimidation, but to proceed swiftly and resolutely with the steps we consider necessary to meet the situation which now confronts the world” Ernest Bevin, Foreign Secretary (1945 – 1951)

4. Collective security, underpinned by formal alliances and partnerships, is the bedrock of our whole approach to national security and a force multiplier for the UK’s deterrence and defence. At the forefront of this is the NATO alliance, which has played an essential part in preserving peace for 75 years. Nearly a billion people in the Euro-Atlantic are protected by the mutual defence clause (Article V), and the self-help and mutual aid clause (Article III) of the North Atlantic Treaty.

5. As a founding member of NATO, the UK has always placed immense importance on the alliance. We have been and remain the only European country to offer our nuclear deterrent to the defence of our NATO allies, and contribute to every aspect of its planning. But equally NATO’s success has always depended on its ability to adapt and the willingness of allies to meet their pledges and share the burden of security. Following the conclusion of the SDR, therefore, we will pursue a “NATO First” approach to how we organise UK defence. Specifically, this means that NATO will be foremost in how the armed forces plan, invest, train and equip themselves.

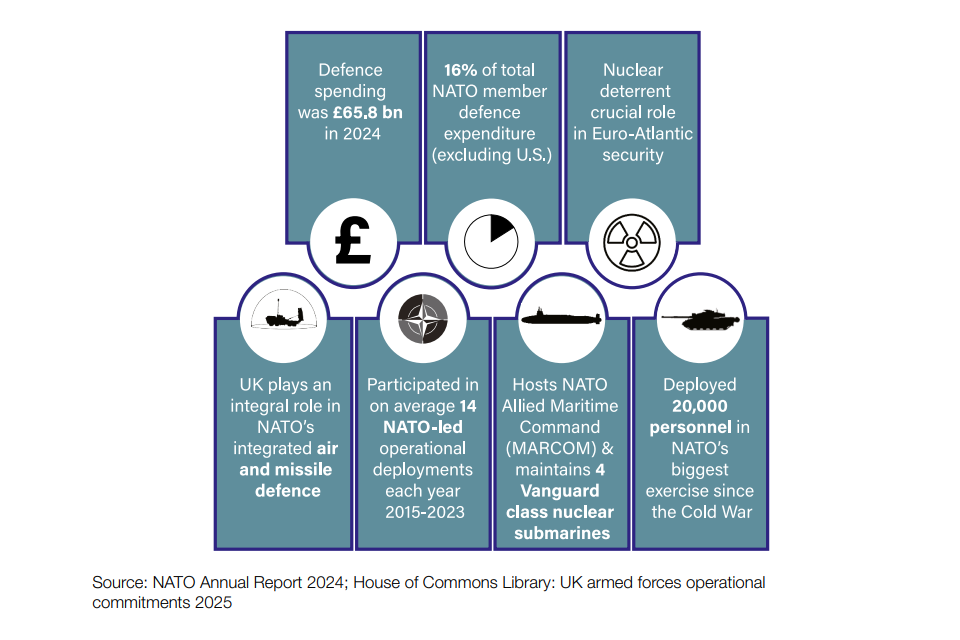

Graphic Title: The UK has a strategic role in NATO

- Defence spending was £65.8 bn in 2024

- 16% of total NATO member defence expenditure (excluding U.S.)

- Nuclear Deterrent crucial role in Euro-Atlantic security

- UK plays an integral role in NATO’s integrated air and missile defence

- Participated in on average 14 NATO-led operational deployments each year 2015-2023

- Hosts NATO allied maritime command (MARCOM) and maintains 4 Vanguard class nuclear submarines

- Deployed 20,000 personnel in NATO’s biggest exercise since the Cold War

6. There are other means by which we can enhance our collective security across the Euro-Atlantic. Through our leadership role in the Joint Expeditionary Force we will deliver renewed deterrence in the increasingly contested High North and Northern Europe, track potential threats to undersea infrastructure and monitor Russia’s shadow fleets. Likewise, we will seek to enhance the Combined Joint Expeditionary Force with France through the 2025 France/UK Summit.

7. The future of Ukraine is a vital part of collective security in the Euro-Atlantic area. Russia continues to inflict devastating attacks on the Ukrainian people and make unacceptable demands for a veto over Ukraine’s self-defence. That is why the UK continues to stand with Ukraine in its self-defence – now and in the future. In supporting Ukraine, our essential goal is to prevent further Russian aggression.

8. A durable settlement in Ukraine is one that defends Ukraine’s sovereignty and security and lets the people of Ukraine decide their own future, without the threat of violence or coercion. Just as we have championed Ukraine during the war, so we will provide the same commitment as it seeks to make peace. Through the UK-Ukraine 100-year partnership we are building the framework for a better future for the Ukrainian people. As part of our renewed efforts, we were the first European country to convene the Ukraine Defence Contact Group. Working closely with France, we have also established the 31-country Coalition of the Willing to step up European support for Ukraine.

- In total, £18 bn committed in support of Ukraine

This support includes but is not limited to:

- Military assistance

- £3 bn per year, plus £2.26 bn funded by profits from immobilised Russian assets

- Over 54,000 Ukrainian personnel trained

- Military equipment including 30,000 new attack and surveillance drones, with further investment to take this to 100,000

- Non-military support

- £400 m for energy security and resilience

- £477 m urgent humanitarian support

- £4.1 bn fiscal support through World Bank guarantees

- UK Sanctions on Russia

- Over 2,500 Russian targets sanctioned

- UK oil sanctions in Q1 2025 cost Russian tankers £1.6 bn

- Over 250 shadow fleet vessels sanctioned

- Achieving justice

- £2.3 m to the International Criminal Court

- Founding member of International Register of Damage

- £11.3 m to investigate war crimes

Graphic title: The UK is playing a leading role in supporting Ukraine to defend itself against Russia’s invasion and grow its economy, whilst increasing pressure on Russia and helping Ukraine achieve justice.

9. One of the vital lessons from the war in Ukraine is the importance of measures like sanctions and export controls. Effective deterrence in the future will require more incorporation of economic measures into our defence and security toolkit. Our sanctions against Russia are designed to deny them the means to continue its war, limiting access to key revenue sources and to critical goods and technology.

10. Sanctions and other measures are most effective when implemented in coordination with our international partners, particularly with G7 and Five Eyes members. As part of our Economic Deterrence Initiative, we are working to strengthen our sanctions implementation and enforcement, including through the establishment of the Office for Trade Sanctions Implementation which has powers to issue civil monetary penalties for breaches of trade sanctions.

Section (2) – Renew and deepen our alliances

Allied and NATO flags lining the Mall to Buckingham Palace to mark the Alliance’s 75th anniversary in April 2024.

11. Our alliances and partnerships are even more critical to our safety in the context of growing risk and uncertainty. By deepening alliances and initiating new partnerships, we can combine our strength, pool financial and technological resources, increase resilience and economic benefits for our people, and mitigate risks. As we renew our relationship with the EU and re-invigorate our relationship with the United States, we will set ourselves the goal of making sure these alliances are defined by greater strategic depth, alongside reciprocity and mutual benefit.

12. The US remains the UK’s most important defence and security ally. There are deep structural foundations to this relationship such as our commitment to NATO, intelligence and nuclear sharing and the interoperability of our armed forces. There are also considerable new opportunities opening up for deeper cooperation on matters like AUKUS and defence technology. The UK was the first country to agree a new economic deal with the US administration. But there is much more we can do to strengthen our alliance in a way that reflects the changing nature of power in the world. That is why we seek an ambitious new science and technology partnership with the US, to cement this closest of partnerships.

13. The UK is also building a new strategic partnership with the EU based on closer cooperation in order to grow the economy, boost living standards, protect our borders and keep the UK safe. The new UK-EU Security and Defence Partnership will support this, enabling closer cooperation across a wide range of areas, from maritime security, space security, tackling hybrid threats, and enhancing the resilience of our critical infrastructure, to irregular migration, global health and illicit finance. New six-monthly foreign and security policy dialogues will enable strategic consultation in themes and geographic areas of joint interest such as Russia/Ukraine, Western Balkans, Indo-Pacific and hybrid threats. The partnership will also mean we can explore closer co-operation and joint investment in our defence industrial base, in a way that can support economic growth and jobs on both sides and help to prevent fragmentation. In doing so, we will work towards the most effective cooperation between NATO and the EU, recognising the primacy of NATO in the defence of Europe but also the growing importance of the EU as a geopolitical actor. Our science collaboration adds another level to the strategic depth of our relationship. The UK’s association to the Horizon Europe and Copernicus programmes means the UK’s scientific community has access to the world’s largest research collaboration programme and this now includes joint research on quantum and space technologies.

14. Bilateral relationships with European neighbours also remain crucial to our national security. Our security and defence relationship with France is unparalleled in Europe. As Europe’s only nuclear weapon states, the UK and France have long recognised that a threat to the vital interests of one would constitute a threat to the vital interests of the other. Work is ongoing to deepen and broaden our cooperation, building on the Lancaster House Treaties and ahead of the 2025 UK-France Summit. We are also enhancing our relationship with Germany, building on the Trinity House Agreement with a new bilateral treaty, and working together on developing a precision long-range strike capability. As the E3, we are working more closely with France and Germany on Ukraine and other issues.

15. We will continue to seek new opportunities to cooperate across the Euro-Atlantic. We are deepening our defence and security partnership with Canada and enhancing collaboration in areas from AI to biomanufacturing and nuclear fusion. Our new agreement with Poland will bolster NATO’s eastern flank, tackling hybrid threats and collaborating on air and missile defence, with significant economic benefits for both countries. On NATO’s northern flank, our strategic defence partnership with Norway is delivering on our shared security priorities in the North Atlantic and High North. Italy is a vital partner on NATO’s southern flank – we are working together on the Global Combat Air Programme and strengthening the interoperability of our carrier strike groups. At the crossroads between the Black Sea, the Caucasus, the Middle East and Africa, Turkey is imperative to UK security interests across Europe and on NATO’s flanks and remains a key NATO and bilateral partner for the UK, with strong military integration and defence industrial collaboration.

Section (3) - Develop new relationships in new domains

The UK Carrier Strike Group on a multinational deployment to the Indo-Pacific.

16. The hard realities of our geography, security and trade necessitate a prioritisation of the Euro-Atlantic area as part of our “NATO first” approach. But evidence of countries like Russia, China, Iran and North Korea cooperating across theatres – sometimes opportunistically and sometimes by deepening strategic ties – demonstrates the interconnectedness of the Euro-Atlantic with different theatres like the Middle East and Indo-Pacific, where we already have strong partnerships. As the SDR notes, after the Euro-Atlantic, these are the two additional priority regions for UK defence.

17. Furthermore, the dispersed and diffuse nature of international power in today’s world means that it is a matter of hard national interest that we look beyond our immediate neighbourhood. That is why we seek to create modern partnerships with vibrant and innovative economies in other parts of the world. In particular, there is a geographically dispersed group of countries, many of which are Commonwealth countries, with which we share a strong community of interest. They stretch from Canada in the North Atlantic to New Zealand in Oceania and include the Gulf States, India, Singapore, South Korea, Indonesia, Japan and Australia. These fast growing and advanced economies depend on the free trade of goods and resources, with financial market confidence built on political stability, maritime security and the predictable application of international maritime law. We have a common interest in working with them against economic coercion and the potential fragmentation of the international economic order into spheres of influence for great powers.

18. Beyond our immediate region, we are committed to contributing to the security and stability in the Middle East, through our diplomatic, humanitarian, military and prosperity footprint, including total trade of £60 billion. As the region is so important to a wide range of UK priorities - including trade, investment, energy and humanitarian - as well as home to hundreds of thousands of British nationals, threats to international security in the Middle East and North Africa have a direct impact on UK interests. The UK contribution to the region spans support to the Global Coalition to defeat Daesh, the Combined Maritime Forces and efforts to secure freedom of navigation in the Red Sea. We have deep and enduring bilateral ties with the Gulf, including wide-ranging strategic partnerships across the region and we are working to secure a Free Trade Agreement with the Gulf Cooperation Council. We are committed to a safe and secure Israel and advancing Palestinian statehood as part of a two-state solution. Both Israelis and Palestinians deserve to live in peace, prosperity and security. We are working to contain Iran’s destabilising influence and to prevent it developing nuclear weapons.

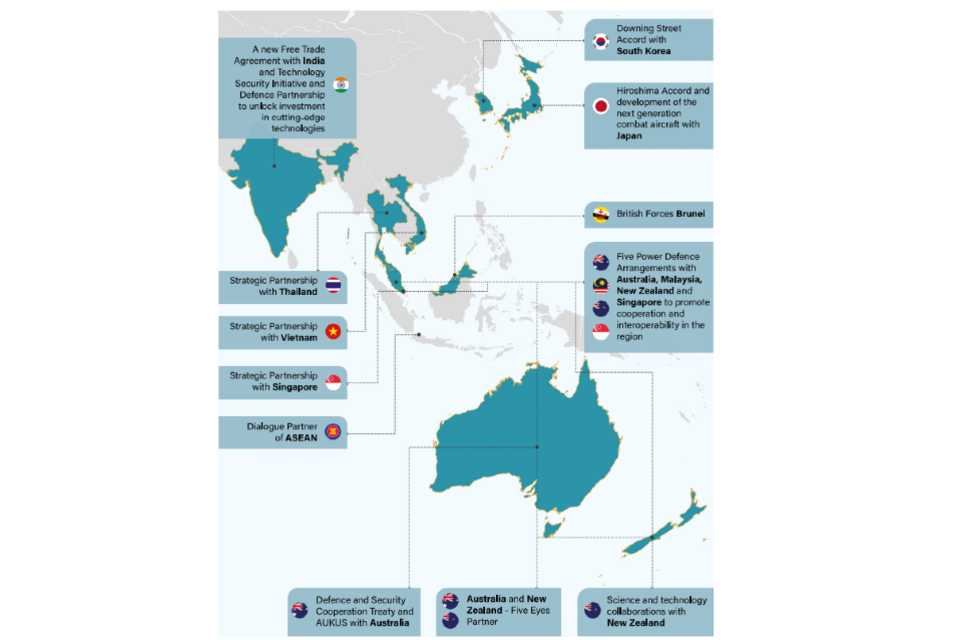

19. India is a country with which we seek a genuine strategic partnership, reflecting its growing importance in the international system. Our new free trade agreement is a landmark deal with one of the fastest growing economies in the world, increasing interaction between our markets and reducing trade barriers. Through our Technology Security Initiative, we are unlocking investment across a range of cutting-edge technologies and through our Defence Partnership we are collaborating on capability development.

20. The UK’s bilateral relationships and partnerships in the Indo-Pacific are designed to enhance the international security on which our shared prosperity depends. Among others, these include our Global Strategic Partnership with the Republic of Korea, Defence and Security Cooperation Treaty and AUKUS agreement with the US and Australia, our Global Strategic Partnership and joint development of the next generation combat aircraft with Japan alongside Italy, and science and technology collaborations with New Zealand. We will underscore our investment in the stability of the region with the sailing of the UK Carrier Strike Group to Australia, reaffirming the UK’s commitment to a free and open Indo-Pacific. We will also continue to invest in the Five Power Defence Arrangements with Australia, Malaysia, New Zealand and Singapore to promote cooperation and interoperability in the region, demonstrated by the UK’s participation in BERSAMA LIMA 24 last year.

21. The centrality of the South China Sea and Taiwan Strait to global trade and supply chains underscores the importance to the UK of regional stability. There is a particular risk of escalation around Taiwan. It is the UK’s position that the Taiwan issue should be resolved peacefully by the people on both sides of the Strait through constructive dialogue, without the threat or use of force or coercion. We do not support any unilateral attempts to change the status quo. As part of our strong unofficial relationship with Taiwan we will continue to strengthen and grow ties in a wide range of areas, underpinned by shared democratic values.

22. The AUKUS programme remains a priority project for UK defence and collective security, as part of a NATO-first, but not NATO-only, approach. The US, Australia and the UK will co-develop an advanced fleet of interoperable nuclear-powered attack submarines, which will be operated by both the Royal Navy and Royal Australian Navy, and other advanced capabilities that will strengthen deterrence. The joint nature of this venture will create a more resilient industrial base in all three countries, vastly increase interoperability between AUKUS partners and allow us to develop a critical edge in the maritime domain to maintain peace and stability.

23. Our membership of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) exemplifies the benefits of wider ties and partnership. It has strengthened trading ties with a number of the fastest growing and emerging economies in the region. We will advocate for a deeper CPTPP, with wider membership and increased links to other major blocs such as the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the EU.

Graphic title:The UK’s relationships in the Indo-Pacific support regional security

- A new Free Trade Agreement with India and Technology Security Initiative and Defence Partnership to unlock investment in cutting-edge technologies

- Strategic Partnership with Thailand

- Strategic Partnership with Vietnam

- Strategic Partnership with Singapore

- Dialogue Partner of ASEAN

- Downing Street Accord with South Korea

- Hiroshima Accord and development of the next generation combat aircraft with Japan

- British Forces Brunei

- Five Power Defence Arrangements with Australia, Malaysia, New Zealand and Singapore to promote cooperation and interoperability in the region

- Defence and Security Cooperation Treaty and AUKUS with Australia

- Australia and New Zealand - Five Eyes Partner

- Science and technology collaborations with New Zealand

24. Creativity and agility will be particularly important where there is the opportunity to move beyond traditional partnerships. Our foreign policy will do more to adapt to the importance of rising powers such as Nigeria and Brazil which are growing in international importance and for which there are new opportunities to deepen investment ties and work together on areas like climate change, science and technology.

25. We will also need to forge closer partnerships with countries in Africa, given its rapidly growing and young population, and opportunities for growth and trade. In particular, we will need to help mitigate threats from instability on NATO’s southern flank in what is an increasingly geopolitically competitive continent. Our Strategic Security and Defence Partnerships with Nigeria, Kenya and Ghana, for example, help to deliver on UK interests at home while building African capability – allowing for cooperation across a broad spectrum of threats, including terrorism, serious and organised crime, hybrid threats and maritime issues.

26. Consistency is essential in approaching the geostrategic challenge posed by China in a way that is aligned with partners across the G7 and beyond. China is a global power undergoing rapid economic, military and technological modernisation on a scale that is unprecedented in world history. The actions taken by China, on issues from international security to the global economy, technological development or climate change, have the potential to have a significant effect on the lives of British people. Each pillar of the Strategic Framework contains measures that are designed to bolster our overall security with respect to China and other state actors that have the ability to undermine our security.

27. We recognise the vital importance of diplomacy in approaching this challenge. The process of auditing our interests with respect to China, in line with the government’s manifesto commitment, is now complete. This work underscores the need for direct and high-level engagement and pragmatic cooperation where it is in our national interest – similar to all other members of the G7. In a more volatile world, we need to reduce the risks of misunderstanding and poor communication that have characterised the relationship in recent years. China’s global role makes it increasingly consequential in tackling the biggest global challenges, from climate change to global health to financial stability. We will seek a trade and investment relationship that supports secure and resilient growth and boosts the UK economy. Yet there are several major areas, such as human rights and cyber security, where there are stark differences and where continued tension is likely. Instances of China’s espionage, interference in our democracy and the undermining of our economic security have increased in recent years. Our national security response will therefore continue to be threat-driven, bolstering our defences and responding with strong counter-measures. We will continue to protect the Hong Kong community in the UK and others from transnational repression.

28. The China Audit therefore recommends an increase in China capabilities across the national security system to strengthen our ability to engage, as well as our resilience and readiness on the basis of deeper knowledge and training. That includes creating the basis for a reciprocal and balanced economic relationship, by providing guidance to those in the private or higher education sectors for which China is an important partner. To ensure that the public, businesses, academia and partners understand our approach, and have the right guidance to help them make safe decisions, we will bring together existing guidance on China in a new gov.uk hub and continue to develop comprehensive guidance relevant to engagement with China.

29. Diplomacy is an essential part of our ability to achieve strength abroad and requires a variety of methods. The UK is clear that multilateral institutions and intergovernmental organisations like the UN, World Health Organisation and the Commonwealth remain critical to making progress on global issues from climate change and biosecurity to the sustainable development goals and conflict prevention. Equally, the UK has a strong economic interest in maintaining a functioning and effective International Monetary Fund and World Trade Organisation. In many cases, these institutions need reform, investment and modernisation. Using our strong expertise across these areas, therefore, we will make it a strategic goal to reshape the international development and humanitarian systems, support the UN80 reform initiative and strengthen international financial institutions.

30. While prioritising poverty reduction and sustainable development, our development spending also needs to support our security, and focus on impact and a narrower set of countries and issues. It must address threats upstream and aligned to what will achieve comparative advantage for the UK. We remain committed to returning to spending 0.7% of GNI on development when fiscal circumstances allow, but we will also explore innovative options for providing new sources of financing, including the use of guarantees, and options that mobilise greater volumes of private finance.

Pillar (iii) - Increase sovereign and asymmetric capabilities

- Sovereign Capabilities

- Rebuild our defence industrial base