Statutory review of the Coronavirus Test Device Approvals (CTDA) process

Published 29 December 2022

Executive summary

The requirements of the Coronavirus Test Device Approvals (CTDA) process are set out in the Medical Devices Regulations (MDR) 2002 and govern the validation of antigen and molecular coronavirus (COVID-19) detection tests. The process was introduced in July 2021 in response to an influx of poor quality tests coming onto the UK testing market at a time when availability of accurate diagnostic test results had the potential to be an important part of the COVID-19 response.

The CTDA requires antigen and molecular COVID-19 tests to undergo mandatory desktop review by the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) to assess their performance before being put into service or placed on the market. The Secretary of State committed to publishing a review of the CTDA.

This review evaluates the impact of the legislation, identifies any lessons learnt and discerns whether the policy has met its key objectives, as defined in the initial impact assessment. It forms the basis for subsequent work on the future of the legislation. It should also consider how the experience of introducing legislation during a pandemic to respond to a specific market failure has played out in practice. This will inform longer decisions about the future of the policy and the potential systems that may be required for other pathogens as part of infection risk management in future significant outbreaks or pandemics.

The government has conducted a review of the policy, making use of existing management information, internal data, and evidence from stakeholders. This was completed in line with the HM Treasury’s Magenta Book on best practice in designing an evaluation. This was to ensure good analytical practice was followed and created alongside the main report to inform and support the resulting conclusions and decisions.

This review sets out the context in which the legislation was introduced, including the course of the pandemic at the time and the availability of testing. It assesses the operational performance of the CTDA and uses that assessment to inform whether and to what extent the CTDA has met its original objectives. It also briefly considers the alternative models for diagnostic device validation.

Overall, it is clear that the CTDA has met its principal and overall objective of improving the quality of tests on the UK market and has successfully addressed the market failure that saw poor quality, inaccurate tests made available for sale. A large number of tests have now successfully passed through the process, indicating a robust market that gives consumers genuine choices.

Whilst the process for approving tests was initially slower than planned, the speed has increased significantly, and the quality of applications has improved as the CTDA regime has matured. The approved register is publicly available on GOV.UK and allows consumers to verify that the test they are purchasing has been validated. However, it does not allow for meaningful comparison of test performance between those devices that meet the minimum standards, so its utility as a comparative tool is limited.

The conclusions in the review will be taken into account when considering CTDA’s future and the future of diagnostic policy more generally.

Background

Before the introduction of CTDA on 28 July 2021, entry to the UK market for COVID-19 diagnostic tests was achieved through Conformitè Europëenne (CE) marking or UK Conformity Assessed (UKCA) marking, a self-declaration by manufacturers on the performance and functionality of their test kit or equipment. Normally, this process of self-declaration is adequate to regulate the UK market and protect the public.

The stated performance and function of these COVID-19 products were not independently verified. Enforcement action would only be taken if a problem arises after the product has come to market. Consequently, an influx of new COVID-19 tests during the pandemic exposed weaknesses in this process and made it clear that more regulation was needed for these products.

Customers were only able to determine a test kit’s use and performance based upon manufacturer-claimed data, which could not be verified. The absence of clear consumer information resulted in a market failure and a potential risk to public health.

Introduction of legislation

To combat this issue, the government introduced legislation to make it mandatory for antigen and molecular tests supplied in the UK to undergo a validation process before being placed on the market or supplied.

An initial public consultation ran for 4 weeks from 8 April 2021 until 5 May 2021. The consultation received 43 written responses that included manufacturers, chemists, retailers, trade associations, professional bodies, local authorities, universities and individual experts.

Overall, there was broad support for the policy aims outlined with a majority (83%) of respondents agreeing there was a need to set minimum performance standards for COVID-19 tests and provide clarity on their quality and performance.

Following a consultation with the public and industry stakeholders, amendments to the MDR 2002 came into force from 28 July 2021 under the Medicines and Medical Devices (MMD) Act.

Enforcement of this legislation remains with the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), as set out in Chapter 3 of part 4 of the MMD. This includes the ability to issue compliance notices, suspension notices, safety notices and information notices in respect of breaches of the legislation.

Under section 10 of The Medical Devices (Coronavirus Test Device Approvals) (Amendment) Regulations 2021, the Secretary of State has a statutory duty to publish a review of the CTDA provisions by 31 December 2022. This review must:

- set out the objectives intended to be achieved by the provision made by these regulations

- assess the extent to which those objectives are achieved

- assess whether those objectives remain appropriate

- if those objectives remain appropriate, assess the extent to which they could be achieved in another way which involves less onerous provision

The aim of the policy was to ensure that all mature antigen and molecular detection COVID-19 devices adhered to minimum standards of performance as set out in regulation 38B of the MDR 2002. This was not the case before the implementation of this policy, which directly led to an influx of poor performing tests into the UK market and a resultant market failure at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In line with the initial impact assessment for this policy, the review will also evaluate whether the policy successfully:

- reduced false negative and false positive test rates, helping to manage the spread of the disease, reduce incidences of unnecessary self-isolation and contact tracing

- corrected the information asymmetry between consumers and sellers

- established a well-regulated minimum bar in COVID-19 in vitro diagnostic devices

- increased reliability of test products and easier comparability of their performance, driving increased take up of testing by employers and institutions

- increased consumer confidence in tests and subsequently, increase volumes of test being reported

The CTDA customer journey comprises two main steps; application submission and the desktop review.

All applications for approval are made through a dedicated online portal. After an application is submitted, the UKHSA CTDA team conducts a basic check to confirm it includes the following required information:

- all required fields on the application are complete

- appropriate responses and attachments are included

- applicants have paid the fee

The main areas of a basic check are:

- manufacturer and product information

- regulatory status

- product performance

- biosafety

- supplementary documents (for example, current version of the instructions for use, biosafety documents, evidence, or performance characteristics)

Payment is required for all applications and this must be completed prior to assessment or validation of applications can commence. Costs depend on the size of the company applying for validation. The full price for a desktop review is £14,000. Small to medium sized enterprises (SMEs) can apply for a discounted rate at £6,200.

Current market

Testing has been an important tool in the response to COVID-19. However, the public now has stronger protection against the virus through vaccinations, natural immunity, antivirals, and increased knowledge. As a result, COVID-19 testing is likely to play a less important role moving forward, be it testing provided from the government or tests purchased privately.

Data on the number of reported COVID-19 virus tests suggests a decline in testing in the UK. This is also reflected in the government’s commercial exercises, including the current dynamic purchasing system (DPS) for lateral flow device (LFD) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) kits. DPS has some aspects similar to an electronic framework agreement, but where new suppliers can join at any time. It has been established to invite applications from potential providers of LFD and PCR test kits to maintain an ongoing supply for targeted testing after the end of universal free testing.

There has been a reduction in the number of CTDA applications, which suggests reduced demand and interest in the market. While this only shows the situation for government procured tests, it is likely indicative of the wider COVID-19 testing market. It has been difficult to accurately assess the number of SARS-CoV-2 diagnostic products on the UK market as there is no requirement for pre-market registration. However, trends in the number of applications to CTDA give some insight into the state of the market.

As of 28 November 2022, there have been a total of 286 applications, 99 (34%) of which were made since 1 January 2022:

- 107 applications have been successful

- 101 applications have been unsuccessful

- 22 applications have been withdrawn by the applicant

The remaining 56 applications are currently in progress.

This highlights CTDA’s balance between allowing quality tests onto the market while removing a significant number of poor quality ones.

The number of applications per month has been on a general downward trend from a peak of 88 in August 2021 to a low of 4 in September 2022. This trend aligns with perceptions that there is limited long term growth in the COVID-19 diagnostics market, and that manufacturers are pivoting into other markets within the In Vitro Diagnostic Device (IVD) sector or leaving the sector altogether.

Changes to the public health situation

The public health situation has changed significantly since the development and launch of the policy. During the early stages of CTDA, testing was a key component of the COVID-19 response and cases were beginning to rise, peaking during the winter. Vaccination rates were increasing (as of 29 July 2021, for people aged 12 years and over, 81.1% of people had received a first dose and 65.5% of people had received a second dose) but high coverage had not yet been achieved.

The MHRA was and continues to be the body responsible for monitoring and regulating UK medical devices, including in vitro diagnostic devices that may be sold on the private market. The MHRA conducts market surveillance of devices and, in their capacity as regulator, has the power to investigate and enforce legislation where non-compliance occurs. Devices are regulated under the MDR 2002.

The division of labour between MHRA, the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) and UKHSA played to their strengths during the pandemic. MHRA continues to ensure the function of wider medicines and medical devices market, whilst Test and Trace (now UKHSA) had the capacity and technical capability to quickly stand up CTDA to address the market failure, specifically in COVID-19 diagnostics, and move at pace to bring in legislative powers and a delivery team. The unique circumstances that existed at the height of the pandemic no longer apply. Going forward, the location of the assessment team for approving CTDA applications will be considered with a view to transferring functions to MHRA when appropriate.

As the situation has stabilised due to high vaccination rates, natural immunity, antivirals and increased knowledge, testing plays a more limited role in the COVID-19 response. However, capabilities are required for possible future waves and variants of concern.

Preparing for a rise in cases during winter

Between January and June 2021, there were on average 19.39 COVID-19 cases and 0.46 deaths per day, per 100,000 population. It was during this period that the government become concerned about the availability of new tests on the markets.

The absence of clear and reliable information related to testing products was causing consumer confusion and risked damaging confidence in testing. It also risked benefitting unscrupulous manufacturers looking to sell poor tests. This prompted the government to address the issue by implementing a more stringent approvals process for tests in preparation for a new winter peak in cases.

The expectation was that, with a rise in cases, testing through LFD and PCR would increase and the number of manufacturers seeking entry to the market, and therefore the number of tests requiring approval, would also increase. The large number of applications to CTDA in its initial stages would support this, as well as the number of COVID-19 cases seen from July 2021 to December 2021 where the average number of positive COVID-19 cases per 100,000 population rose to 41.77 per day.

The emergence of new variants and the behaviour of the virus will be vital in determining the future impact of the disease and our response to it. The Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE) has been clear that new variants are likely to emerge and some of these may result in more severe disease or higher infection rates.

Alongside the front line defences set out in the government’s Living with COVID-19 strategy, such as vaccines and therapeutics, maintaining and increasing our diagnostic testing capability and capacity will be vital in tackling future waves. This will include ensuring the capacity we have consists of high quality, high performance tests for both professional and home use.

Evolution of the testing environment and public availability of testing

At the time of the initial impact assessment, COVID-19 tests were being provided for a range of symptomatic and asymptomatic use cases across the UK by government, at no cost to users. The use of universal free testing was under review and it was uncertain to what extent and when the offer would be scaled back.

SAGE considered plausible outcomes of the pandemic, all of which assumed that the pandemic would reduce in severity and its impact would lessen as vaccination rates increased and the disease progressed towards endemicity. Levels of testing were expected to reduce over time as a result. The growth seen in the COVID-19 diagnostics sector would allow companies to pivot into other diagnostics for other pathogens, but ultimately, this was an area of significant uncertainty.

The government’s provision of free symptomatic and asymptomatic testing to the general public ended in England on 1 April 2022. The latest COVID-19 surveillance data suggests that, at a national level, there is a continued decline in cases and hospitalisations, linked to high vaccination rates. This confirms initial assumptions about the trajectory of the pandemic.

Review of CTDA operational performance

Method

The review has considered existing operational management information and qualitative stakeholder evidence from regular engagement and a call for evidence launched in September 2022. UKHSA has routinely collected data for several aspects of the process which were vital in reviewing its effectiveness. This was also necessary to see where the process could be improved in future and gave an insight into the challenges the process presented, both for the operational team and manufacturers.

The CTDA call for evidence was published on GOV.UK and designed to gather data on the market, stakeholder views and the financial impacts on industry from external stakeholders. It also sought views on the CTDA’s success in meeting its 5 key policy objectives, as set out in the initial impact assessment.

The call for evidence ran for 6 weeks, from 6 September to 18 October 2022. The call for evidence was public, but particularly interested parties were notified of the planned launch dates in advance. This was to ensure we achieved representation from industry and other stakeholders in this space. Parties included:

- industry bodies

- consumer bodies

- notified bodies

- healthcare professionals

- officials from the Devolved Administrations (DAs)

- regulators

UKHSA officials targeted these specific stakeholders as a result of our engagement since the policy’s inception.

Almost 270 individual contacts were contacted via email to highlight the launch of the call for evidence exercise and periodic reminders were sent to encourage responses. Further still, working groups were held with trade bodies, notified bodies, regulators and healthcare professionals to outline the rationale of this evidence collection exercise and how it would contribute to the statutory review.

The structure of the call for evidence was informed primarily by the objectives CTDA has a statutory obligation to be evaluated against. As such, the exercise covered 5 key areas:

- impacts of CTDA on business

- analysis of the wider market

- international regulation and trade flows

- CTDA application and administration

- CTDA objectives

The data was collected through written responses to the call for evidence’s questions via a centralised government mailbox, maintained by UKHSA policy officials.

Publication of protocols for tests temporarily exempt from CTDA

Some manufacturers struggled to provide the necessary evidence to be validated through CTDA in time. Failure to meet the requirements would have meant temporary removal from the market whilst they completed validation, potentially leading to a contraction in supply at a time when testing was expected to ramp up.

In order to safeguard supply, the Secretary of State exercised powers under regulation 39A of the MDR 2002 to publish a protocol list. This would list certain tests that have both passed public sector validation and have lodged an application for validation through CTDA. Tests on this list would be able to remain on the market until 28 February 2022 or until the outcome of their validation application had been determined.

Two further protocols were published by the Secretary of State from 1 March 2022:

- 3 months for professional use devices

- 6 months for self-test devices

These were created to extend the time devices could remain on the market while manufacturers gathered the necessary data to satisfy the approval process.

The protocols were designed to be temporary measures to strike a balance between supply and ensuring devices on the market were properly evaluated against the more stringent requirements of CTDA.

CTDA application process

The government has aimed to provide a high level of transparency and communication with applicants throughout the CDTA process. These steps include dedicated communication, review and complaint channels, which are live with acknowledgments within 48 hours and responses issued within 20 days across a 3-stage process. Applicants receive a report following the desktop review that details where they have or have not met the application guidance and if they have or have not met the threshold performance for their type of technology.

The time taken between submitting an application and receiving a result was highlighted as an issue by respondents to the call for evidence and through regular dialogue with industry groups. Approximately 71% of respondents who answered questions relating to their experience of the CTDA application process in the call for evidence exercise referenced how CTDA has been unable to deliver on the timescales specified within the legislation, including an outcome decision within 20 days.

There are certain trends that can be observed in decision outcomes from the period between August 2021 and November 2022:

- approximately 30% of all decision outcomes took 5 months or less

- the most common value calculated within the dataset was an outcome decision at 5 months (12%)

- of applications received since January 2022, most outcome decisions have been made at 4 months

- of the 286 applications received, only 58 (20%) are still awaiting an outcome

- approximately 20% of all approvals have been made in the last 3 months (between August and November 2022)

The government acknowledges the challenges and long wait times for approval in the earlier stages of CTDA and accepts that the time taken on applications exceeded the anticipated timelines. This was linked to a number of factors, including an initial influx of applications in the first month coupled with challenges in recruiting qualified staff, which created a backlog. This is reflected in collected data which shows that in the first month of CTDA (August 2021), CTDA received 88 applications. This was the highest number of applications in a single month since CTDA began (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Received applications each month (August 2021 to October 2022)

In addition, a large number of the applications received in August 2021 were poor quality and UKHSA’s commitment to ensure each applicant was fully supported during their application would have slowed the process overall. The expected turnaround time was later changed on GOV.UK to reflect that an initial review of the application, rather than outcome, would be made within 20 days.

Respondents have noted that the CTDA process has evolved and improved in its handling of applications and engagement with applicants over time. Timelines have improved without compromising the focus on safety and quality products, and expertise and knowledge of the process has improved over time. We can also observe from Figure 1 that the number of monthly applications has reduced significantly to a consistent but more manageable amount.

Once the backlog of applications has been cleared, we expect that far less resource will need to be allocated to the process. Processing times will remain the same or improve with further streamlining of the validation process and governance, and fewer staff would be required to carry out the work.

Unsuccessful applications

Unsuccessful applications were due to unmet guidance or minimum performance thresholds, with a majority being the former. As failure points varied from application to application, data on exact reasons for failure has not been collected.

Officials worked with applicants and supported them through the application. They provided applicants clarification on why applications risked failure and gave applicants the opportunity to ensure their application met guidance and minimum standards where appropriate. This commitment to supporting applications has undoubtedly affected the timeliness of approvals overall but ensured that good quality tests were not unduly rejected.

Some of the factors cited in poor quality applications included:

- comparator assay (which is used to calculate device performance) does not meet guidance

- incomplete datasets for each sample type

- clinical data has a high proportion of high viral sample or a lack of evidence that test has been evaluated across a full range of viral loads

- no new data generated since test inception

- clarification questions required

In addition, many manufacturers of self-test LFDs have provided only professional-use data to support their applications, and no self-test data. Professional-use data does not sufficiently demonstrate the performance of a test in a self-test setting, and manufacturers using LFDs in self-test scenarios will typically observe a reduction in performance in comparison. It is therefore vital that manufacturers are able to prove the performance of their devices in self-test settings. In many cases, such data is repeatedly requested from applicants as the assessing team is unable to progress an application until this has been provided. This is supported by data that shows a majority of unsuccessful applications have been antigen LFDs (67% of all applications) as of 28 November 2022.

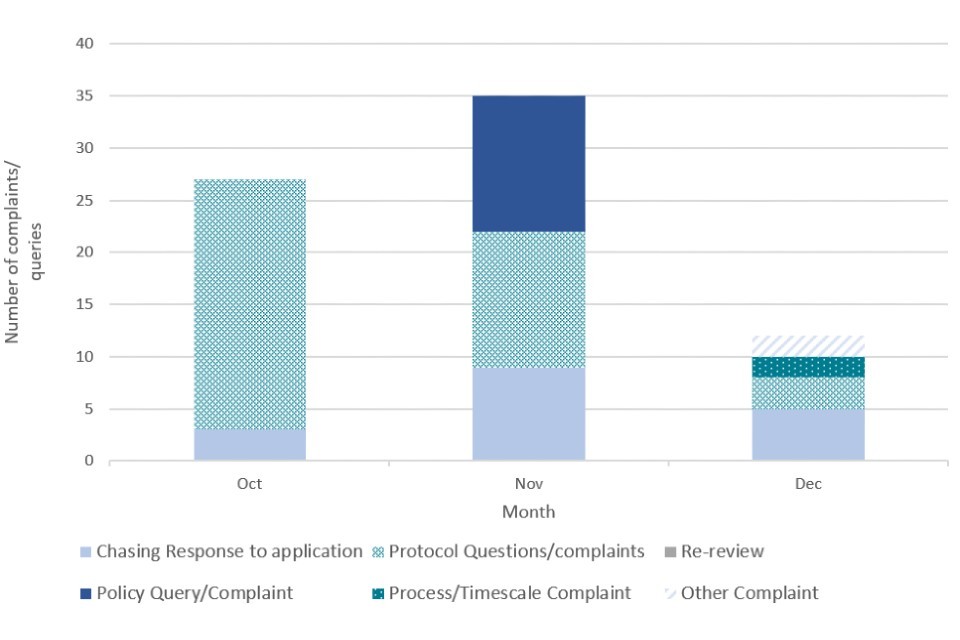

Complaints and queries data

Complaints and queries data was collected by the CTDA team to track the number and nature of complaints received by applicants. To note, complaints data also encompassed general queries and did not exclusively represent only negative engagement or complaints related to the CTDA process, policy or operation. The data was collected from October 2021 to November 2022 (Figure 2, Figure 3).

Figure 2. CTDA complaints and queries data by month (2021)

Figure 3. CTDA complaints and queries data by month (2022)

The number of complaints and queries was highest during the initial transition period after the launch of CTDA in July 2021, with a high of 35 in November 2021. Considering the speed at which CTDA was set up and the anticipated influx of applications given the coming winter peak, a large number of complaints and queries at the beginning of the process could be expected.

The number and nature of complaints changed as the process matured into the new year. Initial queries during the transition period were focused on the protocol and policy surrounding CTDA, whereas a greater proportion of queries in the new year were concerned with chasing applications, which aligns with stakeholder feedback on longer than expected waiting times.

To address feedback on a lack of communication and long wait times, CTDA officials introduced face-to-face engagement with applicants leading to more timely, comprehensive responses to questions. These engagements began in July 2022.

We acknowledge the long timescales it has taken for some approvals to be concluded, especially in the early stages of CTDA. However, applicants have become more content with the level of engagement, complaints handling and feedback provided by the CTDA team as time has progressed, and resourcing and experience has begun to match demand. This is reflected in the complaints data above where a sharp decrease in complaints can be observed from May 2022 onwards (Figure 3), as part of a general downward trend in monthly complaints.

There are a number of reasons behind the complaints and queries the government received. Some were due to poor applications submitted, including examples where CTDA officials have chased applicants for missing or better quality data. Also, while some applicants were content with CTDA guidance and were able to follow the process to successfully submit their application, some applicants were less able to do this and asked a number of questions related to the application process. The quantity of queries represents the ongoing engagement needed to support some manufacturers through the process.

CTDA register data

Diagnostic tests that have successfully passed validation through the CTDA process are placed on a public register on GOV.UK in order to provide transparency and allow consumers to make informed decisions about the tests they purchase and use.

The register is only updated with tests that have passed approval. There are no plans to publish a register of tests that have failed validation. The register also includes information on:

- name of the test

- name of the manufacturer and business address

- date and version of the instructions for use for the device

- type of test

- date of approval

- CE certification

- country of manufacture

- sample type the device uses

As of 1 December 2022, the register had been viewed around 3,100 times in 2022. This was up from around 1,800 views in 2021, comprising a total of around 4,900 unique views. This demonstrates that the register is in use and use has increased as the CTDA process has matured over time.

Consensus was that the register was not well publicised, potentially limiting the impact it could have in informing the public and businesses when making purchasing decisions. The format of the register could also be improved to make it more accessible for users.

In future, wider promotion of such registers, both to industry and the public, would better inform consumer knowledge of tests, and simplification of the format would allow a wider audience to fully take advantage of the information available.

Section 38C(4) of the MDR 2002 allows the Secretary of State to publish additional information relating to the test device and its intended use which he considers appropriate. Further improvements could potentially be made to the content and data held within the register to allow better comparison between tests and to indicate the frequency of register updates.

Call for evidence: demographics

The government launched the call for evidence in September 2022 to evaluate the impact of the CTDA on the diagnostics market and on manufacturers seeking to bring new test devices to market.

In total, UKHSA received 24 written responses to the exercise. 95% of responses were from organisations and a majority of these (62%) were manufacturers. 16 respondents (66%) have or are currently applying to have their test device approved through CTDA. To note, most respondents did not provide answers to all questions.

Call for evidence: impact on business

This set of questions in the call for evidence looked to gather views on the direct impacts CTDA had on businesses. Approximately 66% of respondents who answered the call for evidence section relating to CTDA costs stated that the overall costs of applying to CTDA have been significant.

Some multinational manufacturers and distributors provided a number of comments on perceived CTDA related factors impacting profitability within the UK COVID-19 test market. In particular, they cited exemptions from CTDA afforded to government procured tests as being responsible for distorting normal market dynamics and adversely affecting the relative cost and profit. They also highlighted the temporary protocol as a confounding factor that impacted profit across the sector, with respondents stating it was unclear which tests were included in the protocol and that they were uncertain on the rationale for inclusion.

There were 3 main types of costs incurred due to CTDA:

- costs leading up to submission

- costs between submission and before outcome

- costs incurred to generate additional data

While these respondents commented on ostensibly high costs related to CTDA, most did not provide further detail or evidence on gross profit margins or average unit of production costs, citing confidentiality concerns. Using the costs that were provided shows that costs varied greatly between manufacturers, although most were aligned in stating it has been significant.

From the range of estimated total costs received, on the lower-end, one distributor estimated their total costs to be around £47,000, although they acknowledged that for manufacturers, it is likely to be more. At the higher-end, numerous manufacturers stated their costs had been in excess of £100,000 and another had estimated total costs of £260,000 across seven products.

Respondents were also asked for their views on their future investment plans for COVID-19 diagnostic devices. Consensus among respondents was that manufacturers were pivoting their focus and technology away from COVID-19 for use in other endeavours. Similarly, alongside written responses to the call for evidence, some manufacturers, distributors and trading associations have now indicated they are moving away from COVID-19 diagnostics as demand has decreased, with some manufacturers leaving the sector altogether.

Some respondents expected the demand for COVID-19 related devices to be tied to routine winter respiratory testing. 45% of respondents were looking at creating multiplex tests and consolidating their existing medical devices portfolio to take advantage of this.

Call for evidence: analysis of the wider market

This section of the call for evidence looked at the impact of the provision of free testing and CTDA on the wider market.

The majority (71%) of respondents who answered this question considered the provision of free public testing to have a broadly negative impact on the private market. One manufacturer stated they had decided not to apply through CTDA as LFDs were already being universally offered by the government. In a similar vein, other respondents claimed that the presence of the government provided free testing in parallel to the strict criteria of CTDA created a two-tiered approach to regulatory approval and a resulting market imbalance. A trade association cited this as giving a small number of suppliers a significant competitive advantage in this space. It should be noted that the use of emergency use authorisation to approve tests early in the pandemic was vital as part of the government’s asymptomatic testing programme, and the MHRA only grant such exemptions in exceptional circumstances to ensure the health system has access to critical products.

The call for evidence and operational data also provided insight into the nature and motivations of businesses entering the COVID-19 diagnostics market. Anecdotal evidence provided by CTDA officials and industry stakeholders suggested that, during the early stages of the pandemic, a number of manufacturers pivoted to the diagnostics industry to capitalise on the sudden peak in demand for COVID-19 testing devices. Based on the number and quality of initial applications, there was a view that a lot of applicants were new to the sector and struggled with submitting either the correct evidence to support applications, or devices of suitable quality.

Of those respondents who submitted written responses in the call for evidence relating to levels of growth they expect to see in COVID-19 testing, almost 60% envisaged limited growth in the future COVID-19 testing market, tied to a decrease in demand as the pandemic progressed, public attitude changes and increased vaccination rates. This may also explain why some manufacturers were less inclined to put in revised applications, considering the diminishing returns of securing a successful application. Respondents also felt the end to free testing had a profound impact on the COVID-19 testing market by reducing public demand for tests overall.

Early and ongoing criticisms of CTDA suggested it would stifle innovation and potentially hamper the supply of COVID-19 testing products on the market. Operational data shows that only 2.7% of total registered applications were identified as duplicate products, providing strong evidence that a consistent stream of unique products was being put forward for approval and a diverse private market was being cultivated.

All respondents who answered questions related to trends in consumer confidence and consumer behaviour asserted that there has been increased confidence and acceptability of private testing as the pandemic progressed.

Call for evidence: international regulation and trade flows

This section of the call for evidence considered views on international regulation compared to CTDA, trade flows and the origin countries of applications. Respondents to the call for evidence were broadly aligned in comparing CTDA unfavourably with international equivalents. Principal themes included the perception that CTDA was an unnecessary additional step on top of existing regulatory requirements.

As of 7 November 2022, manufacturers of 284 test devices had applied for CTDA approval. These 284 applications break down by country of manufacture as follows:

- UK – 162

- China – 65

- Korea – 17

- USA – 9

Countries with 3 applications or fewer (total of 31 combined) included:

- Australia

- Belgium

- Canada

- Denmark

- France

- Germany

- Italy

- Luxembourg

- Netherlands

- Singapore

- Spain

- Turkey

- UAE

The data above shows that 43% of applications put forward were from non-UK based companies. This suggests that CTDA did not make the UK unattractive to the global market. It was evident that, based on some of the applications and interactions with applicants in different countries, there may have been difficulty interpreting the regulations; language barriers may have been a factor in this. This is something to consider in future when rapidly stepping up a regulatory initiative and working seamlessly across borders will be necessary.

Alignment with other regulatory approaches on diagnostic device validation would likely make the validation process easier and cheaper for industry, and allow a greater number of products to enter the market.

Some frameworks, such as the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) (the medicine and therapeutic regulatory agency of the Australian government), use third-party conformity assessment as part of the pre-market assessment of COVID-19 devices. Some respondents highlighted this as a possible alternative to CTDA.

The conformity assessment process is carried out by a manufacturer, UK Approved Body (UKAB) and European Union Notified Body (EUNB). It is viewed as a robust process that can demonstrate specific requirements relating to a product have been met, without the additional regulatory steps CTDA established. While this approach was considered, it was discounted as CTDA was able to quickly and more effectively address the urgent issues presented by poor quality tests, and the lack of minimum performance standards in this approach could have kept the UK open to influxes of poor quality tests.

Finance

Financing for CTDA was by way of manufacturer application fees. As set out elsewhere, the application fee was relatively cheap in comparison to other costs involved in bringing a test to market, and therefore pricing is somewhat elastic. From industry feedback, applicants would prefer to pay more and receive a faster response, rather than pay less and have to wait longer for approval outcomes.

The delivery costs are broadly cost-neutral, with a projected small (less than 10%) surplus at year end. This has been affected by difficulties recruiting civil servants, forcing a reliance on contractors, the slow on-boarding of staff into UKHSA, and the front-loaded nature of demand.

Depending on the ultimate outcome of CTDA, there may be a requirement for some UKHSA funding, particularly if the regulatory ownership transitions to the MHRA.

Review of CTDA objectives

As outlined in the initial impact assessment, the desired outcome of CTDA is that all mature (antigen and molecular detection) COVID-19 testing technologies sold on the UK market and used in testing activities meet a minimum standard of performance, achieved through independent validation of those devices.

The objectives were:

- reduce false negative and false positive test rates will help to manage the spread of the disease, reduce incidences of unnecessary self-isolation and contact tracing

- correct the information asymmetry between consumers and sellers

- establish a well-regulated minimum bar in coronavirus in vitro diagnostic devices

- increase reliability of test products and easier comparability of their performance should drive increased take up of testing by employers and institutions

- increase consumer confidence in tests and subsequently, increase volumes of private tests being reported; greater numbers of employers and bodies providing or requiring testing; and their general awareness of the validation programme will be key indicators of success

Analysis of the CTDA in meeting its initial objectives and whether they remain appropriate

Operational data and input from respondents through engagement sessions and the call for evidence were used to determine how effective CTDA has been at meeting its initial objectives, as well as whether they remain appropriate at present.

Objective 1

‘Reduce false negative and false positive test rates to help manage the spread of the disease, reduce incidences of unnecessary self-isolation and contact tracing.’

Respondents to the call for evidence were largely positive about the impact CTDA had on reducing false negative and positive test rates. While overall reduction in false test results could be linked to a number of factors, a point highlighted by respondents, the introduction of minimum standards, which filtered out poor quality products, would by its very nature raise the average performance of tests on the market. The validation process and rigorous governance involved in approvals ensured that any claimed performance and usage of devices by manufacturers is accurate and a true representation of real-world performance.

CTDA has removed 101 tests deemed to either be below the performance threshold or with insufficient data to prove that it meets the performance threshold. Removal of such a large number of likely substandard tests from the market would raise the overall quality of available products and, in doing so, reduce the rate of inaccurate results. While a link between CTDA and improvements to average available test performance can be established, there is insufficient data to demonstrate CTDA’s impact on self-isolation and contact tracing. It should also be noted that contact tracing and self-isolation ended in the early part of 2022, so these are no longer a core part of the CTDA’s live objectives.

Objective 2

‘Correct the market failure, particularly the information asymmetry that prevented consumers from understanding or being able to compare test devices.’

Respondents were split as to whether this objective had been met. Some cited how the CTDA’s uniformed performance requirements had been effective in correcting the information asymmetry, since all tests are ultimately approved based on the same minimum performance criteria. This allowed users to be confident that tests were of a prescribed quality set in legislation. Other respondents disagreed and could not describe how the policy had provided greater understanding to consumers. While the register of approved tests is publicly available and shows which tests have successfully passed validation, some thought the information could be confusing for some as no specific performance data was published. Additionally, the format of the register could be too technical for a lay user to interpret.

While data has demonstrated some usage of the register, we cannot determine how many of these are repeat users or what the experience of the register has been. The register was set up at pace to allow the results of validation to be viewed publicly. However, in line with the views of respondents to the call for evidence and stakeholders who attended the working group, the government acknowledges that the format of the register could be improved and promoted to a wider audience. This would allow a wider range of users to make informed decisions on the devices they were purchasing. Changes to the content of the register may also improve a user’s ability to compare tests based on use or performance.

Objective 3

‘Ensure all tests on the UK market were of the same standards as those used in the NHS, so that they can contribute to empowering people to manage their own health and combat the pandemic.’

Most respondents to the call for evidence who answered questions on this topic (71%) felt that CTDA had not met this objective. It was principally cited that the exemptions in place within the legislation for tests procured directly by DHSC produced a fundamentally flawed system for ensuring equitable standards in quality.

It should be noted again that the use of emergency use authorisation to approve tests early in the pandemic was vital as part of the government’s asymptomatic testing programme, and the MHRA only granted such exemptions under exceptional circumstances to ensure the health system had access to critical products.

Tests procured and used by the government have already undergone rigorous clinical evaluation to ensure performance is accurate. Tests supplied to health service bodies, including NHS trusts, could continue to receive tests until the supply contract ended, provided that the relevant contract was entered into before CTDA was launched on 28 July 2021. Any new contracts entered into after 28 July 2021 would not benefit from this exemption and would be subject to validation through CTDA. While this may have resulted in parallel requirements, a transitionary period was required to ensure vulnerable settings were able to continue to supply users with tests during the pandemic.

Objective 4

‘Increased reliability of test products and easier comparability of their performance should drive increased take-up of testing by employers and institutions.’

A majority of respondents (57%) to the call for evidence disagreed that CTDA had made it easier to compare the performance of test products. The salient point raised was that the lack of published performance data for approved tests and testing services made it difficult for users to compare between devices. While comparisons between approved devices would not be possible using the current register, indicating that the objective of easier comparability has not been met, it does provide an assurance these devices have met defined performance levels. This would provide greater clarity on the quality of available tests compared to available tests before CTDA was implemented. Comparisons between products can also be made on other criteria, such as technology type or sampling method.

In terms of increasing the reliability of COVID-19 test products, CTDA mandates that every COVID-19 detection test (unless otherwise covered by an exemption) must have satisfactory evidence of performance to access the market. The figures for successful and unsuccessful outcomes suggests that the CTDA regulatory process is delivering on this objective.

For the benefit of improving patient safety through greater reliability of tests, it is just as important to remove or prevent unsuccessful tests from entering the market, as it is to ensure high quality tests can continue to be supplied to patients and consumers.

Objective 5

‘Increased consumer confidence in tests and subsequently, increased volumes of private tests being reported.’

Although respondents generally agreed that consumers have increased confidence in tests, they were unconvinced this resulted from the CTDA policy. Some cited how consumers are unlikely to refer to the CTDA approved list in deciding what test to use, which is also complicated by the ongoing exemption for tests procured by DHSC.

Consumer confidence is inherently subjective, and we have limited data on which to base further analysis. Anecdotal engagement with manufacturers reports improved consumer confidence in testing. Additionally, a healthcare professional body issued positive feedback with regards to how CTDA has offered assurance to consumers in respect to a test’s performance quality by legislating minimum thresholds.

As there is currently no requirement or provision to report private tests, we do not have any data to produce an analysis of the effect CTDA may have had on reporting rates. However, the government is planning to introduce the ability for individuals taking private tests to voluntarily report their results into the NHS COVID-19 app. This will remind those using the app (still currently roughly 8 million to 9 million people in England and Wales) of the latest guidance and will provide a light-touch contact tracing alert offer. The NHS COVID-19 app service is anonymous and is not connected to the GOV.UK system. However, if cases rise over winter, this will help maximise the impact of any private testing done in reducing transmission.

Relevance of objectives in the current public health landscape

Despite mixed views on CTDA’s ability to meet the above objectives, stakeholders mostly agreed that the objectives and rationale remained appropriate, especially when considering the protection of public health. UKHSA agrees that most of the objectives remain appropriate, except aspects of Objective 1 and Objective 5.

The main aspect of Objective 1 (to reduce false positive and negative results) has been achieved and remains appropriate as the virus is still in circulation. However, contact tracing and self-isolation are both policies that were retired after the initial objectives were devised and resultantly are no longer current objectives of the policy.

The first aspect of Objective 5 has been met and also remains relevant as increasing consumer confidence is still an important feature of the overall response to COVID-19 and testing. However, the reporting of private tests is not currently possible making this aspect of the objective unachievable. Alongside this, this aspect of testing will also become less relevant as testing take-up declines. The remaining objectives are still considered to be appropriate considering the stage of the pandemic we are in and the possibility of future variants of concern.

The ultimate purpose of CTDA was to improve the quality of tests available on the market, by both approving quality tests and removing those that were poor from being available on the market. This has demonstrably been achieved.

Could these objectives be achieved through a different approach?

CTDA and its objectives were developed and implemented in response to a risk to public health caused by an influx of poor quality tests. While other, potentially less onerous options were considered during policy development, such as third-party conformity assessments by approved bodies, these would not have achieved the required level of stringency to effectively remove sub-standard products. The increased standards in a pre-market environment could have also increased the time to market.

CTDA’s approach to diagnostic regulation stipulates minimum performance thresholds for devices, set in legislation. By setting a minimum threshold, manufacturers are required to only submit products that are high quality and, in doing so, reduce the incidence of false positive and negative results (Objective 1). While conformity assessments would undoubtedly provide a greater level of stringency over the previous self-declaration regime while potentially being less challenging for businesses to apply to, it would nevertheless drop the average standard of products available on the market by removing minimum thresholds. As a result, it is unlikely this approach would meet Objective 1 as effectively as CTDA currently does.

The remaining objectives could be met by a regime such as third-party conformity assessment to varying degrees. Devices that have passed assessment can be found on the European commission’s database, providing consumers with better information on and confidence in available tests (Objective 4 and Objective 5) and go some way to correcting information asymmetry (Objective 2). Objective 3 is less likely to be achieved as effectively by conformity assessment when compared to CTDA, again because no minimum thresholds are stipulated.

Conclusion

There is strong evidence that the principal objective of CTDA (Objective 1) has been met, namely to improve the quality of tests available on the private market by setting minimum performance thresholds and reducing the incidence of false positive and negative results.

The number of applications and successful and unsuccessful outcomes demonstrate a consistent supply of tests coming through the approval process and would indicate that, despite some difficulties, companies with suitably robust procedures and evidence are able to successfully satisfy the requirements of CTDA and get their tests onto the UK market.

While the approved register does not allow consumers to compare tests (Objective 4) based on performance, it allows users to confidently select products that had met CTDA requirements and were able to meet defined minimum performance thresholds, improving consumer information and filtering out poor products (Objective 2).

Improvements to the promotion, design and content of the approved devices register would likely make it easier for CTDA to achieve its objective of increasing comparability, allowing purchasers to make informed decisions and possibly increase CTDA’s utility as a marketing tool as more users become cognisant of test device performance and product quality. Publishing confirmed test performance may also lead to competition and further innovation to increase test accuracy, but such changes to the register’s content would require the consideration of the Secretary of State.

While UKHSA acknowledges a period during which some tests were temporarily exempt from CTDA, these tests were still required to eventually undergo and pass CTDA to continue to be procured and used (Objective 3). This approach allowed us to eventually apply the same stringency provided by CTDA to all available tests, while ensuring security of supply.

We also know that consumer confidence and understanding of testing has improved as the pandemic has progressed (Objective 5). However, we acknowledge it is difficult to gauge the direct impact CTDA had on this factor, and are conscious improvement to the approved register could have a greater positive impact.

Analysis of both internal and externally sourced data has demonstrated mixed stakeholder views on CTDA. The government acknowledges that there are areas of the policy and operation of the regime that could be improved to reduce barriers for industry and provide a more useful service to users who may wish to compare testing devices. Comparisons to other regimes, such as third-party conformity assessment, demonstrate the utility of such regimes and suggest that a move to such a regime under non-emergency situations may be a proportional approach to regulation. However, there are still questions as to whether such regimes are stringent or prescriptive enough to prevent the type of market failure seen in the UK in 2021, especially without enforceable minimum performance standards.

Lessons have been learned regarding the operation of CTDA, and iterative improvements have been made to the support provided to applicants and the approval process itself. With increased experience, a mature process and a relaxation of the market following high demand last year, it has been conveyed that, in future, far less resource would be required to run the process, and approval times should improve.

CTDA was established to correct a market failure and, by successfully addressing the root causes of the issue, has demonstrated that such failures can be prevented through robust legislation. The lessons from this review and the longer-term development, implementation, and operation of CTDA will be taken into account when considering CTDA’s future and the future of diagnostic policy more generally.

Annex A: international examples of COVID-19 test validation

The government has reviewed and summarised examples of other models for diagnostic device validation, particularly from international comparators with significant testing programmes.

It has been clear that different countries have mounted different responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, based upon their existing diagnostics market, current and prospective regulatory regimes, and previous experience of dealing with infectious diseases.

EU’s response to COVID-19 test validation

Feedback from stakeholders involved in the CTDA application process have commented that many other international markets had already confirmed their routes to getting diagnostic devices on their respective markets. In the EU, tests enter the market through a process of manufacturer self-certification which was the regulatory regime in place in the UK during the market failure. The limits of such a system are that there is no independent pre-market evaluation.

Regulation (EU) 2017/746 on in vitro diagnostic medical devices (IVDR) introduces a major update of the regulatory framework in the European Union and replaces the EU Directive 98/79/EC, the In Vitro Diagnostics Directive (IVDD). This modernisation of the European regulatory system brings about several changes to the information provided with in vitro diagnostic devices (IVDs) and their regulatory documentation. The EU IVDR took effect from 26 May 2022 and implements stronger requirements than the preceding EU Directives.

Currently, under the IVDD, it was estimated that only 10% to 20% of IVDs required notified body involvement in the conformity assessment process, while the rest were allowed to self-declare that products met the required regulatory standard. The IVDR regulation flips these numbers so that below 80% will require notified body involvement.

The IVDR fundamentally changes the classification system that has been adopted under the IVDD, from a list-based classification to a rule-based one. COVID-19 detection devices are classed as Class D devices.

In October 2021, the EU Commission published an amendment to the IVDR to give manufacturers more time to go through the conformity assessment procedure due to capacity issues in the notified body community and delays in establishing other essential infrastructure.

The Commission primarily justified its proposal based on the impact of the coronavirus pandemic; the pandemic tied up a lot of resources and made it almost impossible to implement the necessary measures quickly.

At the time, only six notified bodies in the whole of Europe could work with the IVDR (there were 18 under the IVDD) and these were all already at capacity. Also, notified bodies now have to be involved with a considerably higher number of in vitro diagnostic medical devices. Previously, their involvement was needed for about 8% of IVDs on the market. Under the IVDR, just under 78% (approx. 24,000 IVDs in total) would require the involvement of a notified body.

According to a survey by MedTech Europe, if the deadlines were not extended, from 2022, around 22% of in vitro diagnostic medical devices would disappear from the market (there are currently approximately 40,000).

Although notified bodies are actively building capacity, it can take up to two years to qualify a new technical reviewer, and the pool of professionals with IVD experience is limited.

Any existing Class D devices that did not previously require the involvement of a notified body in the conformity assessment process under the IVDD can take advantage of an additional transition period until May 2025. This longer transition period applies to COVID-19 detection devices, though they will nonetheless be required to comply with post-market surveillance and vigilance activities under the IVDR during the transition period.

However, manufacturers cannot benefit from the extension if they are making significant changes. If significant changes are necessary, the IVD must be in compliance with IVDR, even in consideration of the extended transition period. New devices must also be in full compliance with the IVDR before they are placed on the market.

The new EU regulation will rely on an approach that’s different from CTDA to ensure product safety and will elevate COVID-19 tests to the category of devices (Class D) requiring the highest level of pre-market conformity assessment. This will require a designated third-party company, known as a notified body, to assess that the device meets regulatory requirements, including verifying claims made by the manufacturer in relation to performance through a process of third-party conformity assessment. As part of their conformity assessment, performance claims will also be verified by EU reference laboratory testing.

Furthermore, Class D devices will be subject to batch verifications of each batch that is manufactured, meaning the notified bodies will review quality control (QC) data and documentation before each batch can be released.

Under the IVDR, clinical performance can be demonstrated through studies, peer-reviewed published literature, and experience gained through routine testing. For performance evaluation reports (PERs) that must be updated on an ongoing basis and support the clinical benefit and clinical utility of the IVD test, regulators will be looking at analytical and clinical performance and scientific validity with a high level of scrutiny. For Class D devices, the PER must be updated at least annually.

IVDR also requires every IVD manufacturer to implement a quality management system (QMS). Manufacturers of all COVID-19 detection devices will need to have their QMS and their Technical File or Design Dossier audited every year by a notified body to ensure their compliance with IVDR classification and other applicable requirements.

In the EU, ISO 13485 is the recognized standard for a QMS, and an audit must be performed to make sure that the manufacturer’s QMS conforms to the standard’s requirements. If the IVD manufacturer passes the audits, they will be issued a CE certificate and an ISO 13485 certificate.

After receiving the certificates, the manufacturer must declare conformity, as directed by Annex IV of IVDR. The Declaration of Conformity is the manufacturer’s assent that their device is compliant with all applicable regulations within the EU. At this point, the CE marking may be affixed to the product.

The main difference between CTDA and the EU IVDR is that, unlike CTDA, the IVDR does not stipulate any minimum requirements for testing device specificity or sensitivity. While the IVDR provides more rigour than previous regimes, the lack of enforceable performance standards means the UK could once again be subject to influxes of poor quality diagnostic tests if we reverted to a similar regime.

The IVDR also makes provision for Class D devices to be assessed by EU reference laboratories as part of the conformity assessment process. This applies to all new devices post May 2022 and will apply to all legacy devices after May 2025. The network of laboratories is yet to be set up, but should be in the future. This is beyond the existing CTDA regulatory regime that has not implemented further assurance through laboratory testing as legislative limitations in the UK would make this challenging.

UKHSA considered and discounted the option to introduce third-party conformity assessment. We recognise that third-party conformity would be an alternative approach to give assurance on the quality of testing and would ensure robust post market surveillance and quality control.

However, due to the urgency presented by the COVID-19 pandemic, we believe that a rapid intervention over and above what conformity assessments typical provide is required to address the quality issues in tests urgently in response to the market failure.

US’ response to COVID-19 test validation

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has established a validation process predicated on transparency and achieving a greater assurance of diagnostics test performance. Separate processes were established for both antigen and molecular test devices.

In autumn 2021, the FDA established a fully independent test programme for antigen tests, with the aim of improving confidence in test performance and functionality. The process involved validation through an independent lab and a resultant data package was returned to the FDA who was then able to authorise a test for use within 24 hours. This process is rigorous but requires large expenditure per validated test, at around $1 million.

For molecular and serology-based testing, the FDA has collaborated with the National Cancer Institute (NCI) to establish expected performance. Before tests go to NCI, a desktop exercise is conducted by the FDA, in a similar fashion to the current CTDA process. This initial triage rejects tests that are likely to have poor performance. Even after this initial filter, tests vetted by NCI at the next stage have a 66% failure rate. This data is then collected and submitted to the FDA for review.

The FDA has received well over 5,000 submissions for review and authorised almost 500 tests. As of June 2022, around 80% of all submission were not authorised demonstrating the increased requirements of tests as a result of the new processes. They have also noted that, similar to the situation in the UK, the vast majority of tests put forward for submission were sub-par upon validation of performance or relied upon poor submissions and data. The FDA also noted issues with potentially fraudulent submissions, another issue seen in the UK’s regulation of COVID-19 tests.

New Zealand’s response to COVID-19 test validation

The New Zealand government, similar to other international health administrations, had early concerns around the quality of COVID-19 diagnostic tests entering their market. To prevent poor quality tests from entering New Zealand, an order was issued that prohibited a person from importing, manufacturing, supplying selling, packing, or using a point-of-care test for SARS-CoV-2 or COVID-19 unless authorised or exempted from prohibition by the Director General of Health. In addition, New Zealand has since implemented a pre-market approval process that ensures only high quality COVID-19 point of care testing products are approved for use in the country.

To assure high standards are maintained while retaining security of demand, the Director General must be satisfied that the activity, point of care test, or class of point of care test will not pose a material risk to the public health response to COVID-19. This was achieved by Health New Zealand establishing a set of criteria in the assessment of such devices.

Under the Medicines Act 1981, medical devices in New Zealand are regulated by Medsafe, which does not conduct any pre-market assessment or issue any approvals for devices. To manage the influx of tests as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, Section 37 was introduced for COVID-19 tests, allowing the minister to prohibit the import, manufacturer, packing, sale, possession, supply, administration, or other use of medicines of any description or medical devices for any specified period not exceeding 1 year. While the government is able to invoke Section 37 whenever they deem an infectious pathogen to be a serious risk, this is not viewed as a viable long-term solution. As a result, New Zealand is in the process of reviewing is regulatory regime.

Australia’s response to COVID-19 test validation

The Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) is the medicine and therapeutic regulatory agency of the Australian government. The TGA regulates the quality, supply and advertising of medicines, pathology devices, medical devices, blood products and most other therapeutics. The TGA has responsibility for the regulation of tests provided to the healthcare market and for public self-testing, as well as supplier engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The TGA treats COVID-19 tests differently from their regular approach to other medical devices. They do not have an emergency use pathway for the expedited approval of COVID-19 diagnostic tests, but instead undergo a full pre-market regulatory review of these specific IVDs. Any tests that are successfully approved are published online in the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG), like the UK’s public register of approved tests on GOV.UK. Only COVID-19 tests included on the ARTG can legally be supplied in Australia.

Like CTDA, Australia’s regulatory framework for COVID-19 diagnostic test approvals includes a desktop review. However, a third-party conformity assessment for a QMS is required before an application can be made to the TGA.

The TGA is conducting a post-market review of available COVID-19 tests on the ARTG to determine their effectiveness at detecting variants of concern. In cases of safety, performance, or non-compliance concerns, the TGA may take further regulatory action, including the suspension or complete removal of devices from being supplied in Australia.

Glossary of terms

- antigen – a substance (protein) that causes the immune system to produce antibodies and trigger an immune response. In the case of COVID-19, spike proteins are found on the surface of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. An antigen test detects these proteins of the SARS-CoV-2 virus

- ARTG – the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG) is the reference database of the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). It provides information on therapeutic goods that can be supplied in Australia

- assay – a laboratory test to find and measure the amount of a specific substance. Sometimes used to describe the COVID-19 tests carried out in a laboratory

- CE marking – the Conformitè Europëenne (CE) mark is defined as the EU’s mandatory conformity marking for regulating the goods sold within the European Economic Area (EEA). In Vitro Diagnostic Devices (IVDs) that are approved under the In Vitro Diagnostic Device Regulation (IVDR) as suitable for operation in the European market will be granted a CE mark by their EU Notified Body (EUNB) to demonstrate conformity. Depending on the classification of the medical device, manufacturers can also assess the conformity of their test kit or equipment themselves, with regards to their performance and functionality, through a self-certification process

- COVID-19 – a contagious disease caused by a virus, the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)

- CTDA – Coronavirus Test Device Approvals (CTDA) refers to a mandatory requirement for in-scope antigen and molecular diagnostic tests for COVID-19 to undergo validation to assess their performance against requirements set out in the Medical Devices Regulations 2002 before being placed on the market or put into service in the UK

- desktop review – a process in which UKHSA scientific advisers review supplier evidence against a set of performance criteria as part of the overall CTDA regulatory pathway

- DHSC – the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) is the UK government department responsible for health and adult social care policy in England. It is also responsible for elements of policy that are not otherwise devolved to the Scottish Parliament, Welsh Parliament or Northern Ireland Assembly

- direct molecular test – an in vitro diagnostic medical device for the detection of the presence of viral ribonucleic acid (RNA) specific to SARS-CoV-2. It does not use a preliminary step of purification and concentration

- DPS – the Dynamic Purchasing System (DPS) is a procedure available for contracts for works, services and goods commonly available on the market. As a procurement tool, it has some aspects that are similar to an electronic framework agreement, but where new suppliers can join at any time

- IVD – an In Vitro Diagnostic Device (IVD) examines and analyses bodily specimens for the purpose of providing information. Classic IVD examples include pregnancy tests, blood tests and COVID-19 tests

- EU IVDR – the Regulation (EU) 2017/746 on in vitro diagnostic medical devices laying down rules for the placing and making available on the market, and putting into service, in vitro diagnostic devices for human use and accessories for such devices in the European Union

- EU MDR – a Regulation (EU) 2017/745 on medical devices laying down rules for the placing and making available on the market, and putting into service medical devices for human use and accessories for such devices in the European Union. The EU MDR replaces the Council Directives 90/385/EEC and 93/42/EEC

- EUNB – EU Notified Body (EUNB) are independent organisations designated by EU competent authorities, for the purpose of assessing the conformity of products before being placed on the market

- FDA – the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is a federal agency of the United States Department of Health and Human Services. The FDA is responsible for protecting and promoting public health.

- LFD test – a Lateral Flow Device (LFD) test, detects COVID-19 viral proteins called ‘antigens’, produced by the virus. They give rapid results within 30 minutes after taking the test

- MDR 2002 – the UK Medical Devices Regulations (MDR) 2002 implements the EU directives concerning medical devices, active implantable medical devices, and in vitro diagnostic medical devices and includes the essential requirements and conformity assessment procedure for IVDs to be put into service or placed on the market. The MHRA is responsible for ensuring the quality and safety of medical devices by ensuring compliance with the MDR 2002

- MHRA – the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) is an executive agency of the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) in the UK. It is responsible for ensuring that medicines, medical devices and blood components meet applicable standards. MHRA also ensures a safe and secure supply chain, promotes international standardisation and influences the international regulatory frameworks, educates on the risks and benefits of medicines, medical devices and blood components, and supports innovation and research

- MMD Act – the Medicines and Medical Devices Act 2021 is a legislation in relation to human medicines and medical devices; veterinary medicines and medical devices; and the protection of health and safety, in relation to medical devices

- PCR test – the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test for COVID-19 is a molecular test that analyses a specimen, looking for genetic material (ribonucleic acid, or RNA) of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19

- QMS – a Quality Management System (QMS) is a structured system of procedures and processes covering all aspects of design, manufacturing, supplier management, risk management, complaint handling, clinical data, storage, distribution, product labelling, and more. Most medical devices will require some form of a QMS; the complexity of the QMS will vary based on the classification of the device

- SAGE – the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE) provides scientific and technical advice to support government decision makers during emergencies

- TGA – the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) is Australia’s government authority responsible for evaluating, assessing and monitoring products that are defined as therapeutic goods

- UKAB – a UK Approved Body (UKAB) is an organisation that has been designated by the MHRA to assess whether manufacturers and their medical devices meet the requirements set out in the MDR 2002

- UKAS – the United Kingdom Accreditation Service (UKAS) is the national accreditation body recognised by the British government to assess the competence of organisations that provide conformity assessment certification, testing, inspection and calibration services

- UKHSA – the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) is the UK government agency responsible since October 2021 for England-wide public health protection and infectious disease capability, replacing Public Health England and NHS Test and Trace. It is an executive agency of the Department of Health and Social Care

- variant – viruses, like SARS-CoV-2, change over time and will continue to change the more they circulate. A variant is where the virus contains at least one new change to the original virus. Some variants of SARS-CoV-2, include Delta and Omicron

- viral loads – the amount of measurable virus in a standard volume of material, such as blood or plasma.