Code of Good Agricultural Practice (COGAP) for Reducing Ammonia Emissions

Updated 1 January 2024

Executive summary

This Code of Good Agricultural Practice (COGAP) for reducing ammonia emissions is a guidance document produced by Defra in collaboration with the farming industry. It explains the practical steps farmers, growers, land managers, advisors and contractors in England can take to minimise ammonia emissions from the storage and application of organic manures, the application of manufactured fertiliser, and through modifications to livestock diet and housing.

Ammonia (NH3) is a key air pollutant that can have significant effects on both human health and the environment. The government has agreed to reduce ammonia emissions by 8% in 2020 and 16% in 2030, compared to 2005 levels. Around 88% of ammonia emissions in the UK come from agriculture. These targets can be achieved through widespread adoption of the measures in this Code.

Nitrogen, in the form of ammonia, is lost from organic manures (such as slurry, solid manure and litter, digestate, sludge and compost) when they come into contact with air, particularly on warm or windy days. Nitrogen is also lost from manufactured fertilisers during spreading. The more that this occurs, the more nitrogen is lost as ammonia, meaning the material is a less effective fertiliser and loses value. Therefore, measures to reduce ammonia emissions and improve overall nutrient management practices could reduce the amount of manufactured fertiliser that farmers need.

A summary of key points is provided below. Further information, rationale and sources of support are provided in each chapter.

Storing organic manures

- ensure your farm has enough well-maintained storage to be able to spread slurry only when your crops will use the nutrients

- cover slurry and digestate stores or allow your slurry to develop a natural crust

- use slurry or digestate storage bags

- cover field heaps of manure with plastic sheeting

- keep poultry manure and litter dry

Spreading organic manures

- use a nutrient management plan and regularly test manure and soil to calculate suitable application rates and plan timing

- spread only the right amount, in the right place, at the right time

- spread in cool, windless and damp conditions

- spread slurry and digestate using low emission spreading equipment (trailing hose, trailing shoe or injection) rather than surface broadcast (splash plate)

- incorporate solid manure, separated fibre, cake or compost into the soil by plough, disc or tine as soon as possible and at least within 12 hours

- consider processing slurry or digestate, such as by acidification (with professional equipment and advice) or separation

Spreading manufactured fertilisers

- use a nutrient management plan to calculate suitable times and rates of application

- switch from urea-based fertilisers to ammonium nitrate

- use urease inhibitors with urea-based fertilisers

- if applying urea-based fertilisers, spread when rainfall is due, apply by injection to soil or incorporate into soil as soon as possible

- apply ammonium nitrate in cool and moist conditions but avoid applying when rainfall is expected

Livestock diets

- consider using a professionally formulated diet to match the nutrient content of the feed to the requirements of the animal at different production stages

Livestock housing

- regularly clean housing and yards and remove manure. For example, use a belt system to remove layer manure twice a week and regularly wash and scrape cattle yards.

- minimise the amount of mixing between urine and faeces (as ammonia forms when these two mix). For example, use grooved floors in cattle housing to channel urine.

- minimise the surface area of exposed slurry pits. For example, use V-shaped gutters and reduce the surface area of the slatted area in pig housing.

- keep poultry litter and manure dry. For example, ventilate colony deep pit or channelled systems.

About this Code

This Code of Good Agricultural Practice for reducing ammonia emissions (we refer to it as “this Code”) is a guidance document which explains how farmers, growers, land managers, advisors and contractors can minimise ammonia emissions from agriculture by making changes to:

- organic manure storage

- organic manure application

- manufactured nitrogen fertiliser application

- livestock feeding (sector specific)

- livestock housing (sector specific)

This Code has been written by Defra in collaboration with the Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board, the Agricultural Industries Confederation and the National Farmers Union. Contributions have also been made by other organisations including ADAS, the British Egg Council, the Central Association of Agricultural Valuers, the Environment Agency, Linking Environment and Farming (LEAF), the National Association of Agricultural Contractors, Natural England, Plantlife and the Tenant Farmers Association.

Advice in this Code is appropriate for all farming systems except for grazed, perennially-outdoor-reared livestock, which tend to have lower ammonia emissions compared to other systems and for which there are few ammonia mitigation methods.

This Code sets out voluntary measures and does not override or change any current or future statutory requirements.

The Code applies to England. The Code is not intended to replace any existing Codes; it supplements ‘Protecting our Water, Soil and Air: A Code of Good Agricultural Practice’ published by Defra in 2009.

The Code is not a manual on how to manage your farm or holding. It is to help you identify appropriate actions for your individual situation. Many farms and holdings are already delivering a good standard of environmental protection, but there are often ways to make improvements.

The measures outlined in this Code are not exhaustive and are not intended to be taken in isolation. If you carry out any practices that are not covered in the Code you should protect the environment by following the general principles that are outlined in it. You are recommended to seek professional advice before investing in equipment, making any changes to livestock numbers or diets, or to help with fertiliser choices; examples of sources of advice are included at the end of each relevant section.

The ammonia emission reductions associated with each mitigation method are UNECE recommended estimates .

For further guidance on the measures set out in this document we suggest reading the UNECE Framework Code for Good Agricultural Practice for Reducing Ammonia Emissions. You can download this from the UNECE website.[footnote 1]

Where to get support to reduce your ammonia emissions

Financial support

You may be eligible to apply for a grant towards equipment that will help you to carry out some of the actions set out in this Code. For further information on grants which may be available, see www.gov.uk/topic/farming-food-grants-payments/rural-grants-payments.

Technical support

Seek professional advice before making investments such as purchasing equipment or updating livestock buildings, changing the diet of your livestock or if you need help to improve the efficiency of your fertiliser use. Consider what is suitable for your farm, the welfare of your livestock, the need to comply with existing regulations and the needs of any assurance or certification schemes.

Sources of specific support are signposted in each of the following sections.

General sources of advice regarding the concepts in this Code include:

- farming organisations, trade associations and levy bodies

- Tried & Tested (Tel: 02476 858 896) provide free nutrient management information and guidance and can help you to find suitable farm advisers or a laboratory for soil analysis

- the Campaign for the Farmed Environment (Tel: 02476 858 897) provide free advice on soil management and crop nutrition and has produced a short guide on how to reduce your farm’s ammonia emissions which you can download

- if you are in a high priority area for water quality, you may be able to receive free training and advice regarding nutrient management, manure management and farm infrastructure through Catchment Sensitive Farming (Tel: 020 80 262 018)

- the Farming Advice Service (Tel: 03000 200 301) can provide free technical and business advice to help you meet regulatory requirements

- a wide range of information about statutory requirements, guidance documents and sources of advice via www.gov.uk/government/organisations/department-for-environment-food-rural-affairs/services-information.

1. Introduction

1.1 What is ammonia?

Ammonia (NH3) is a key air pollutant that can have significant effects on both human health and the environment. Agriculture is the dominant source of ammonia emissions in the UK, with the sector accounting for around 88% of total UK emissions. Most ammonia comes from livestock manures in animal housing and stores, and when manures and nitrogen fertilisers are applied to land.

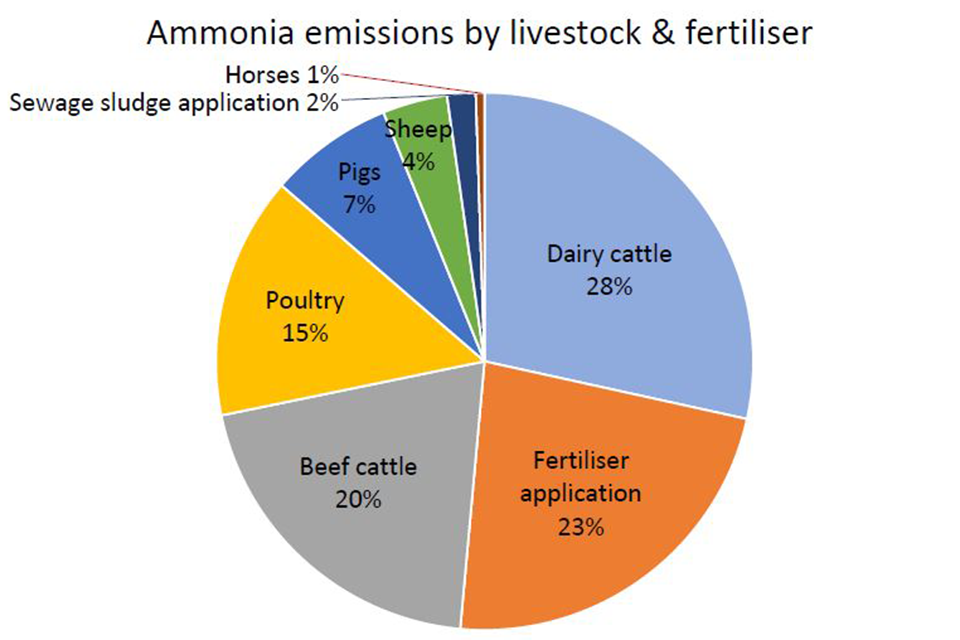

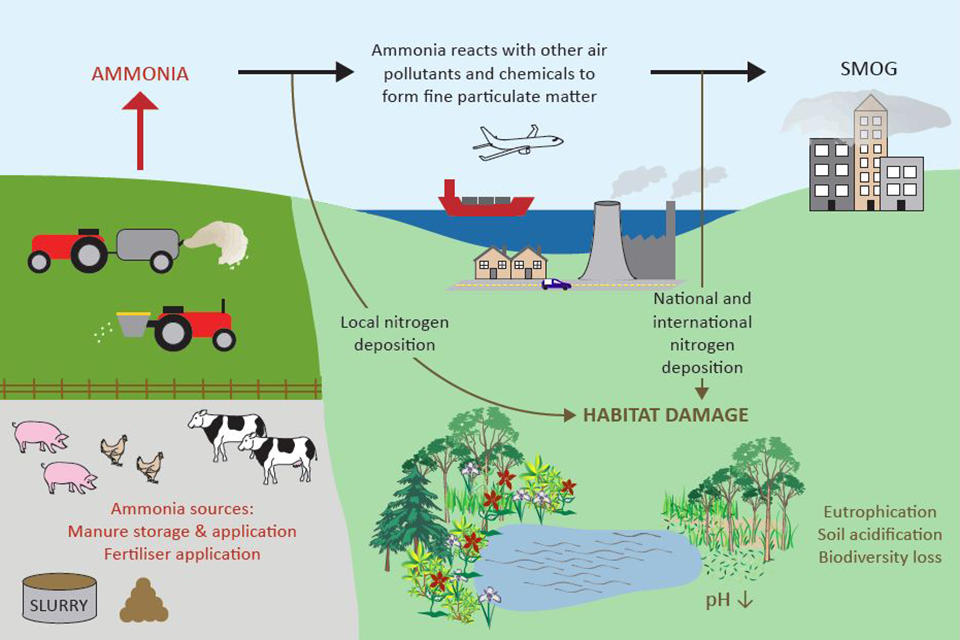

Figure 1a: The breakdown of agricultural ammonia emissions in the UK in 2016 by livestock and fertiliser category.

Figure 1b: The breakdown of agricultural ammonia emissions in the UK in 2016 by management category.

Data source: National Atmospheric Emissions Inventory 2018[footnote 2]

1.2 Using nitrogen efficiently

Organic manures (such as slurry, solid manure and litter, digestate, sludge and compost) are natural sources of nitrogen and are used to build soil fertility and support plant growth, commonly supplemented with manufactured fertilisers. However, nitrogen, in the form of ammonia, is lost from organic manures when they come into contact with air, particularly on warm or windy days. The more that this occurs, the more nitrogen is lost as ammonia, meaning the material is a less effective fertiliser and loses value. Therefore, measures to reduce ammonia emissions and improve your overall nutrient management practices could reduce the amount of manufactured fertiliser that you need.

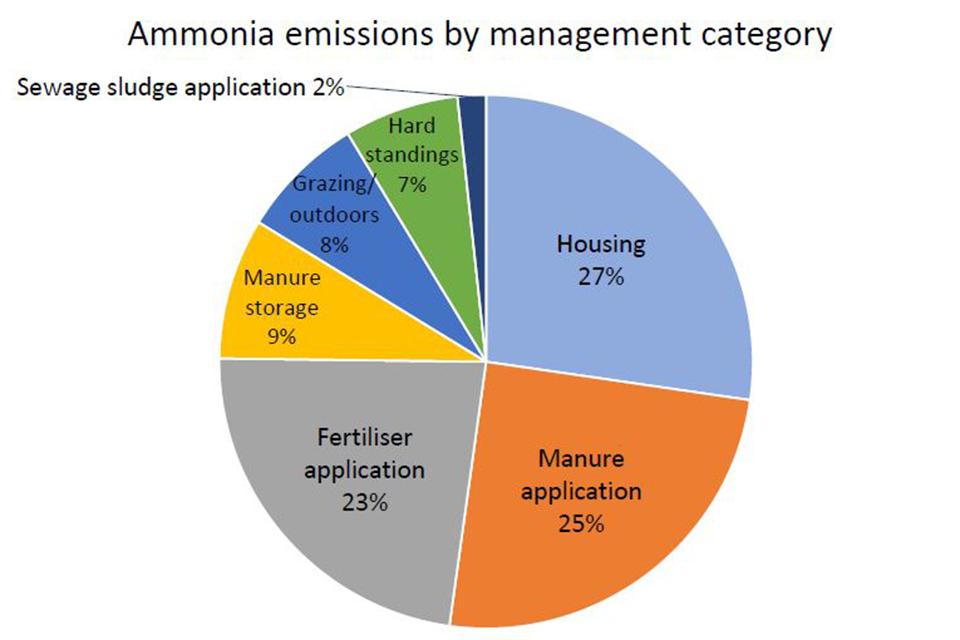

Ideally, measures to reduce ammonia emissions should be applied to all stages of the farming process, from livestock diet and housing to manure storage and spreading. Otherwise, nitrogen retained at one stage could be lost at the next stage as ammonia.

Your aim should be to integrate and balance all nutrient sources to improve crop nitrogen use efficiency. Fertiliser should be applied in the right amount, at the right time and in the right place. If too much fertiliser, either organic or manufactured, is applied to land, or it is applied in inappropriate weather conditions, the soil and crops can’t use the nitrogen quickly enough and a percentage is lost from the farming system as ammonia or nitrous oxide to air and nitrate to water. This pollution could be substantially reduced and savings made through consistent use of good nitrogen management practices.

Figure 2: The nutrient loop. Nitrogen needs to be preserved at each stage of the farming process. Nitrogen Use Efficiency (NUE) is a unit of efficiency used in livestock or crop production. NUE is increased by increasing farm output per unit of nitrogen input. Image credit: © Agricultural Industries Confederation

1.3 Effects of ammonia emissions

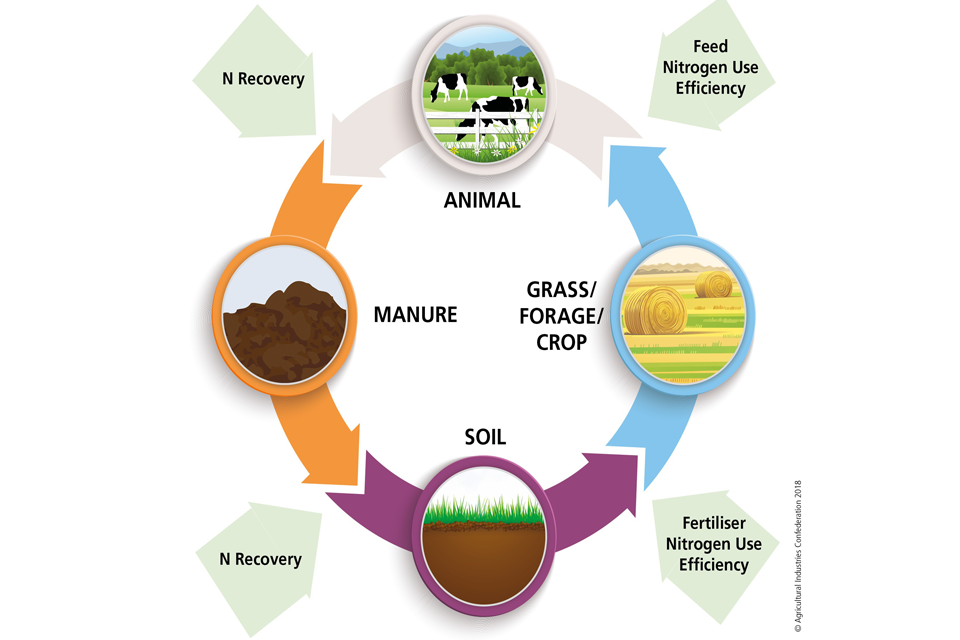

In low concentrations, ammonia is not harmful to human health. However, when ammonia emissions combine with pollution from industry and transport (like diesel fumes) they form very fine particulate matter (PM2.5), which can be transported significant distances, adding to the overall background levels to which people are exposed. When inhaled, particulate matter can penetrate deeply into body organs and contribute to causing cardiovascular and respiratory disease. It is estimated that particulate matter emissions as a whole result in 29,000 early deaths every year in the UK[footnote 3].

When deposited on land, ammonia can acidify soils and freshwaters, ‘over-fertilising’ natural plant communities. The extra nitrogen can increase the growth of some species (such as rough grasses and nettles), which out-complete other species (such as sensitive lichens, mosses, and herb species) that have lower nitrogen requirements. In 2014, 96% of the area of nitrogen-sensitive habitat in England received more nitrogen than it could cope with effectively[footnote 4]. Once the soil quality has changed, together with the balance of species on the land, it takes a long time, and can be costly, to restore it.

The location of ammonia sources can be very important for reducing the risk of effects on plants and people. Where possible, ammonia sources should be positioned as far as possible from sensitive receptors like people and protected habitats. Protected habitats within proximity of your farm can be identified through the Defra MAGIC Geographic Tool.

Figure 3: The environmental impacts of ammonia pollution. Image credit: Defra

1.4 Why do we need to reduce ammonia emissions?

The UK has international obligations under the UNECE Gothenburg Protocol and the National Emissions Ceilings Directive to meet targets for limiting ammonia emissions to protect human health and the environment. The UK also has requirements to protect sites designated for wildlife and conservation such as Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs) and Natura 2000 sites, many of which currently experience high levels of ammonia and more nitrogen deposition than they can tolerate.

We are therefore committed (and legally obliged) to reduce ammonia emissions by 8% by 2020 and by 16% in 2030, compared to 2005 levels. These targets can be achieved through widespread adoption of the measures in this Code. By following the good practice set out in this guide you will be contributing to improving air quality and protecting wildlife habitats.

2. Store and cover your organic manures

Slurry stores must comply with The Control of Pollution (Silage, Slurry and Agricultural Fuel Oil) Regulations (SSAFO), introduced in 1991, last amended in 2010. If your farm is in a nitrate vulnerable zone (NVZ) there are extra rules for storing organic manures.

Nitrogen, in the form of ammonia, is lost from organic manures when they come into contact with air. Covering the manures or reducing the surface area of exposed material reduces the amount of contact with air. This reduces the amount of ammonia that forms, meaning more nitrogen is retained in the fertiliser.

2.1 Solid manures

It is important to minimise the movement of wind over solid manure in order to reduce ammonia emissions. Where practical, you should cover manure heaps with plastic sheeting, which must be well secured to avoid being blown away. This could also help to retain the nutrients within it and reduce odour.

It is particularly important that you keep poultry manure and litter dry. When it becomes wet it can lead to higher emissions of ammonia. Keeping litter from layers dry could also help to make it a more desirable fertiliser for sale. In nitrate vulnerable zones, you must cover temporary heaps of poultry manure without bedding or litter with waterproof material.

Making the surface area of the manure stack as small as possible can also help to reduce emissions, for example by storing in ‘A’ shaped heaps or by constructing walls to increase the height, taking into account health and safety considerations.

2.2 Slurries and other liquid organic manures

Having enough storage capacity for your needs means you can just spread slurry and other liquid organic manures onto land when your crops really need it and when weather and soil conditions are right (see section 3.1). Slurry store capacity ideally should be calculated around the availability of land and windows for spreading so that maximum benefit can be obtained from the nutrients available. This will help to minimise the loss of nitrogen to air and water. It is also important to ensure your slurry store is well maintained and replaced when necessary to prevent pollution incidents.

If the slurry does not develop a natural crust, putting a cover on your store will reduce the amount of ammonia emitted into the air and help retain valuable nutrients within the slurry. This can reduce the amount of any additional manufactured fertiliser required. The slurry surface will be shielded from wind, allowing ammonia concentrations to build up beneath the cover, suppressing further emissions from the slurry. Impermeable slurry store covers may also reduce your slurry application and storage costs, particularly in areas of high rainfall where rain can dilute slurry.

Where the fibre content of the cattle or pig slurry is high and it is not necessary to regularly mix and spread the slurry, allowing the slurry to develop a natural crust can reduce ammonia emissions during storage by up to 40%. Similar effects can be achieved by adding chopped straw or LECA (light expanded clay aggregate) pellets to non-crusting slurry, as long as it won’t cause management problems. These fibres rise to the surface and act as a barrier, reducing the interaction between the movement of air and the nitrogen in the slurry. However, a natural crust will not reduce the amount of rainfall which can get into the store.

Storage systems that have a large surface area per unit volume (such as a lagoon) have a greater potential for ammonia emissions as more slurry is exposed to the movement of air. It is more difficult to reduce ammonia emissions from lagoons than from tanks. Before constructing a lagoon, you should plan effective mitigation measures for reducing emissions, such as installing a cover.

Slurry gases can kill. Ensure all slurry stores and working practices comply with the necessary regulations. If adding a cover to an existing store, seek advice before starting construction to ensure the structure can support the extra weight. You can get general guidance from the Health and Safety Executive.

There are currently three main styles of covers available for slurry storage:

Tight lid, roof or tent structures can be built on concrete or steel tanks or silos. They are highly effective, reducing ammonia emissions during storage by around 80%, and prevent rainfall entering the store. You must ensure the store has enough structural integrity to support the weight of a lid or roof.

Figure 4: A fixed cover on a slurry tank. Image credit: Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board

Floating sheeting can be used on concrete or steel slurry tanks but is best suited to small earth-banked lagoons. The sheeting may be made of plastic, canvas or other suitable materials. They are moderately effective, reducing ammonia emissions during storage by around 60%, and some types will also prevent rainfall entering the store.

Figure 5: A floating plastic cover on an earth-banked slurry lagoon. Image credit: Defra

Floating LECA (light expanded clay aggregate) balls or hexa-covers are suitable for non-crusting pig manures or digestate. They are moderately effective, reducing ammonia emissions during storage by around 60%, and are easy to apply but do not prevent rainfall from diluting the organic manure.

Slurry or digestate storage bags can offer a good alternative to building an above-ground covered store and reduce ammonia emissions during storage by up to 100% compared to an uncovered equivalent-sized store. They can be installed within existing storage tanks or lagoons as an alternative to installing covers. However, they may not be suitable for all locations and require some form of secondary containment (such as a bund) to ensure leaks or spills are captured and do not cause pollution.

Figure 6: A slurry bag. Image credit: Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board.

In addition to applying some of the mitigation methods described in this document, farms close to nitrogen-sensitive habitats may be encouraged to plant trees near slurry stores or livestock housing, known as ‘shelter belts’. This is because trees can disrupt air flow, reducing wind speeds and dispersion of ammonia, as well as directly recapturing some of the ammonia. This can therefore help to lower the local impacts of ammonia emissions from your farm, such as damage to nitrogen-sensitive soils, habitats or water nearby. It is important to seek advice before planting to ensure the trees are placed in an appropriate location to maximise their impact.

2.3 Where to get more advice

The Construction Industry Research and Information Association (CIRIA) have produced free guidance on the selection, design and maintenance of farm waste storage: “Livestock manure and silage storage infrastructure for agriculture, Part I and II (CIRIA Reports C759a &b)”.

You can get further information on the types of storage systems and covers available in the UNECE Framework Code for Good Agricultural Practice for Reducing Ammonia Emissions (p15-18).

The Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board (AHDB) has published various tools which can help you calculate slurry and manure volumes.

3. Apply organic manures effectively and efficiently

You must ensure you apply organic manures in accordance with all relevant regulations, including the ‘Farming Rules for Water’ (introduced in England in April 2018). The spreading of waste to land requires a permit from the Environment Agency. If your farm is in a nitrate vulnerable zone (NVZ) there are extra rules for spreading organic manures.

Ammonia emitted during the application of organic manures to land accounts for a large proportion of total emissions. You should minimise losses at this stage of organic manure management, otherwise the benefits of reducing ammonia emissions from storage or livestock housing will be lost.

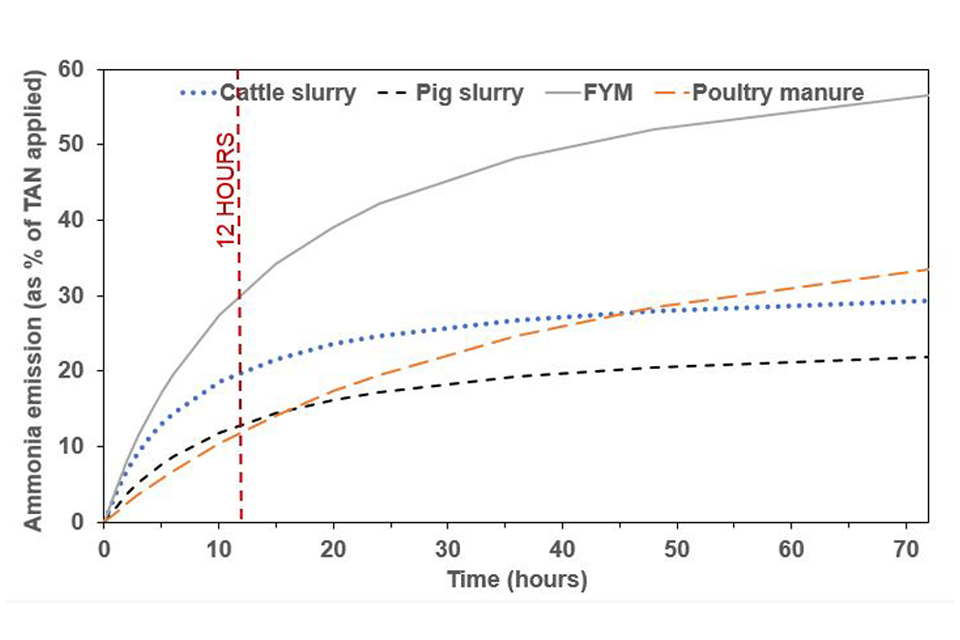

Ammonia emissions and therefore nitrogen losses occur during spreading when the organic manures are in contact with the air. Therefore, you should adopt methods which place slurry and digestate straight on or into the soil, rather than broadcasting it, to make the most of your fertiliser and reduce emissions. Similarly, you should incorporate solid organic manures into the soil as soon as possible and at least within 12 hours to minimise nitrogen losses.

To gain the maximum agronomic and financial benefit from your organic manures, and to avoid increasing the risk of ammonia emissions and nitrate leaching into water, you should plan how you apply them according to soil type, nutrient status and crop needs. Testing of the organic manures should be used alongside both your manure and nutrient management plans to work out an appropriate application rate, together with appropriate times and methods of application. If you do not have these plans and would like to develop them, please see the references in section 3.3.

3.1 Slurries, digestate and other liquid manures

Low emission spreading techniques

You can reduce the amount of ammonia emitted during application of liquid organic manures (such as slurry and digestate) by decreasing the surface area exposed to the air. This can be achieved by applying the material to the soil surface using a bandspreader (trailing hose or trailing shoe) or placing the material beneath the soil surface using an injector.

We don’t recommend spreading liquid organic manures using surface broadcasting (splash plate) as it can result in high ammonia emissions and can also increase the risk of surface run-off into water. Broadcasting involves the liquid being forced at high pressure onto an inclined plate, spraying the liquid into the air. The act of this spraying, together with the placement of the liquid on the soil or crop surface, means much of the nitrogen in the fertiliser is then able to react with the air, forming ammonia, and less nitrogen remains in the material to fertilise the crops. If you can’t avoid using a splash plate and you are spreading on bare soil, you should incorporate the slurry or digestate into the soil immediately after application and at the latest within 12 hours. This can be done with a disc or a tine cultivator, as, unlike for solid manures, they are just as effective at reducing emissions from slurry as using a plough.

Trailing shoe, trailing hose and injection systems are collectively known as “low emission spreading equipment”, as the way they place fertiliser onto and into the soil means more nitrogen is retained in the soil and less is able to react with the air to form ammonia. In some cases, this may mean it is cost efficient to spread liquid organic manures with low emission spreading equipment rather than using surface broadcasting, as you are getting more value from the fertiliser. Low emission spreading equipment can also result in a more even distribution of fertiliser and reduced odours, compared to broadcast application.

| Surface broadcast | Trailing hose (low emission) | Trailing shoe (low emission) | Shallow injector (low emission) | Deep injector (low emission) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical range of dry matter | Up to 12% | Up to 9% | Up to 6% | Up to 6% | Up to 6% |

| Requires separation or chopping | No | Yes (if over 6% DM) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Relative work rate | → → → → | → → → | → → → | → → | → |

| Uniformity across spread width | ✓ | ✓ ✓ ✓ | ✓ ✓ ✓ | ✓ ✓ ✓ | ✓ ✓ ✓ |

| Ease of bout matching | ✓ | ✓✓✓ | ✓✓✓ | ✓✓✓ | ✓✓✓ |

| Crop damage | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate | High |

| Relative odour | High | Moderate | Low | Low | Very low |

| Relative ammonia reduction | 0% | 30-35% | 30-60% | 70-80% | 90% |

| Capital cost | £ | ££ | £££ | £££ | ££££ |

Table 1: Comparison of slurry distribution systems. Levels of odour and ammonia emissions are given relative to surface broadcast application and assume that the slurry is not incorporated after spreading.

Trailing hose (also known as a bandspreader or dribble bar) can achieve a 30-35% reduction in ammonia emissions compared to broadcast slurry. Suitable for grassland and arable land (where the slope is less than 15%), it can be used on solid seeded crops and wide units may be compatible with tramlines. Hoses connected to the boom of the spreader distribute the liquid organic manure close to the ground.

Figure 7: A trailing hose system. Image credit: John Williams, ADAS

Trailing shoe (also known as a bandspreader) can achieve a 30-60% reduction in ammonia emissions compared to broadcast slurry. Suitable for grassland, arable land (pre-seeding) and row crops. Metal ‘shoes’ ride along the soil surface, parting any crop present to ensure the liquid organic manure is placed on the soil.

Figure 8: Application of slurry with a trailing shoe. Image credit: Defra

Injectors can achieve a 70-90% reduction in ammonia emissions compared to broadcast slurry. There are various types of injectors, which are each classed as either a shallow or deep injector based on how deep the liquid organic manure is placed in the soil.

Injectors are not suitable for use on slopes >15%, shallow soils, stony soils, highly compacted soils, high clay soils (>35% clay) in very dry conditions, peat soils (>25% organic matter content) or perforated-tile drained soils that are susceptible to leaching.

Shallow injectors are suitable for arable land or grassland. Shallow injectors place the organic manure typically 4-6 cm deep in narrow slots cut into the soil, typically 25-30 cm apart.

Deep injectors are best suited to arable land (due to the damage that can occur to grass or crops). Deep injectors should only be used when the soil is sufficiently dry and not on land with a drainage system in order to prevent water pollution. Deep injectors cut slots 10-30 cm deep, spaced about 50 cm apart.

Figure 9: Shallow injection equipment. Image credit: Defra

The most effective application type may not be appropriate for your land. For example, small irregular shaped fields may present difficulties for large machines and hilly terrain or stony, dry soils may prevent certain application methods. Use of an injector in unfavourable soil or weather conditions, and/or at too high an application rate, could lead to surface water and/or groundwater pollution. You may wish to seek advice before purchasing new equipment to ensure it is appropriate for your land and to see if any financial support is available. In some cases, it may be more cost-effective to use a contractor.

Time your application appropriately

Ammonia emissions almost double for every 5°C increase in temperature[footnote 5] and also increase with wind speed due to the increased movement of air over the organic manures.

To reduce ammonia emissions and retain nitrogen for crop use, you should therefore apply slurry, digestate and other liquid organic manures:

- under cool, windless and damp conditions

- when wind speed and air temperature are decreasing

To avoid odour nuisance when spreading near to residential areas you should consider wind direction and time of day and use low emission spreading equipment wherever possible.

Slurries and other liquid organic manures should only be applied to soils that support infiltration (such as not saturated or very compacted) to minimise both air and water pollution.

Acidification and separation

There are several actions you could take before spreading to help reduce ammonia emissions during storage and following application:

Acidify the slurry or digestate: Lowering the pH of slurry or digestate to below pH 6.0 will reduce the amount of ammonia released to the atmosphere, helping to retain nitrogen so it can be used by crops. This method involves either nitric or sulphuric acid, is applicable to pig slurry, cattle slurry and digestate, and is widely used in the Danish pig sector.

Specialist commercial equipment must be used to acidify slurry and you must ensure your building or store will not be damaged. Only commercial nitric or sulphuric acid should be used. You must comply with all relevant health and safety regulation regarding the storage and use of acids.

Acidification can be carried out either in the housing period, in the slurry store or at the time of application:

- housing period acidification involves flushing slurry from the pits and adding acid until the desired pH is reached. Some of the acidified slurry is then pumped back up to the pits, mixing with the fresh slurry and improving the air quality within the building.

- store acidification involves adding acid to slurry or digestate in a store and using a specially designed mechanical arm, attached to a tractor, to stir the mix. Treatment takes approximately one hour, depending on the size of the store. Typically the lower the pH, the longer the slurry or digestate can be stored whilst retaining the benefits of acidification.

- application acidification involves using specialist equipment (which can be retrofitted to some tankers) to apply acid to the slurry or digestate immediately prior to application. A computer system controls the dosage and pH levels.

Separate your slurry or digestate: Mechanical separation of slurry and digestate removes some solids (such as proteins and fatty acids) which restricts ammonia forming in the liquid fraction. Emissions from the solid portion should be reduced during storage (by covering the heap) and during spreading (by rapid incorporation into soil). As with whole slurry and digestate, the liquid fraction should only be applied to soils that support infiltration (such as not saturated or very compacted). Lowering the pH before separation, as outlined above, can result in further reductions in ammonia and greenhouse gas emissions.

3.2 Solid manures

Poultry and farmyard manures (>12% dry matter), sewage sludge cake, separated digestate fibre and compost made from green waste should be incorporated into bare soil as soon as possible and within 12 hours of application. Ploughing is generally more effective than disc or tine at reducing ammonia emissions from solid manures, despite the longer timeframe involved. Manure being used as mulch or to control wind erosion of susceptible soils does not require incorporation.

Figure 10: Ammonia loss as a percentage of Total Ammoniacal Nitrogen applied (%TAN) (nitrogen in the form of ammonia) with time following application if the manures are not incorporated. The 12 hour recommended target for incorporating the material is shown as the red dashed line.

Data courtesy of Rothamsted Research[footnote 6].

3.3 Where to get more advice

Defra has issued guidance on the use of organic manures and manufactured fertilisers on farmland.

The Nutrient Management Guide (RB209) provides guidelines for crop nutrient requirements and the nutrient content of organic manures and is maintained by the Agriculture & Horticulture Development Board (AHDB).

Tried & Tested is a hub for free nutrient management information and guidance provided by a partnership of industry bodies. Useful tools include ‘Think manures: A guide to manure management’, guidance on producing a nutrient management plan and check sheets to keep in your tractor cab.

MANNER-NPK is a free tool which can help you to quickly calculate the amount of crop-available nitrogen, phosphate and potash following application of organic manures, producing a one page summary report.

4. Use manufactured nitrogen fertilisers effectively and efficiently

You must ensure you apply fertilisers in accordance with all relevant regulations, including the ‘Farming Rules for Water’ (introduced in England in April 2018). If your farm is in a nitrate vulnerable zone (NVZ) there are extra rules for using nitrogen fertilisers.

All applications of manufactured nitrogen fertilisers should be based on a nutrient management plan, integrating fertiliser and manure supply and taking into account your soil management plan. As with organic manures, you should only apply manufactured nitrogen fertiliser according to crop requirement and when weather and soil conditions are right. Regularly maintain, calibrate and test all application equipment, as appropriate, to ensure efficient distribution and utilisation of nutrient supplied.

4.1 Urea and ammonium nitrate

Typically up to 2% of total nitrogen applied in the form of solid ammonium nitrate (AN) fertilisers is lost as ammonia in the UK. In comparison, up to 45% of nitrogen can be lost from urea-based fertilisers as ammonia, depending on conditions such as weather and soil type. Losses from liquid nitrogen fertiliser (containing AN and urea N (UAN)) will fall between these values depending on application technique. Switching from urea-based fertiliser to ammonium nitrate fertiliser could therefore reduce your ammonia emissions.

4.2 Time your application appropriately

To reduce emissions of ammonia, you should apply manufactured fertilisers to the soil during favourable conditions, maximising the adsorption of ammonium ions onto the clay component of the soil and organic matter, and at a time when crops can make maximum use of the nitrogen.

- ammonium nitrate: you should plan applications in cool but moist conditions and avoid application when rainfall is expected to minimise the risk of nitrogen loss (to both air and water)

- urea: you should plan applications when soils are moist (not wet), or when rainfall is expected, and the weather is cold. If feasible, you should incorporate it into the soil immediately after application.

4.3 Low emission application techniques

Use the following measures to help minimise ammonia emissions from the application of manufactured nitrogen fertiliser:

- rapidly incorporating (>50% ammonia emission reduction) or injecting (>80% ammonia emission reduction) urea fertilisers into the soil when possible

- use of urea with urease inhibitors (70% mean ammonia emission reduction for solid urea, 40% mean ammonia emission reduction for liquid UAN). Urease inhibitors can delay the breakdown of urea to allow subsequent rainfall to wash it deep into the soil.

- switching from urea to ammonium nitrate. While AN can be more expensive, the net cost difference may be negligible due to lower nitrogen losses.

- in irrigated systems, irrigate to at least 5mm immediately after urea application to encourage adsorption into the soil

Avoid:

- use of foliar sprays of urea, unless specifically recommended

- urea application on light sandy soils. The low clay content results in limited capacity to adsorb ammonium

- urea application to grassland and arable crops in dry periods

- top-dressing of ammonium sulphate (where incorporation is not possible) on calcareous soils (pH >7.5)

- use of ammonium phosphate on calcareous soils (pH>7.5) where the following are not possible:

- rapid incorporation

- injection or placement into the soil

- application just prior to rainfall

- immediate irrigation

4.4 Where to get more advice

FACTS Qualified Advisers deliver up-to-date nutrient management advice for crops and grassland. Make sure they have an up-to-date ‘FACTS Qualified Adviser’ (FQA) card.

Tried & Tested is a hub for free nutrient management information and guidance provided by a partnership of industry bodies.

You may want to consider using specialists to check your fertiliser spreader is working efficiently, such as those available through the National Spreader Testing Scheme.

5. Dairy and beef sector-specific measures

5.1 Cattle diet

Before making adjustments to the diets of your livestock, you may wish to seek advice from a registered feed adviser to ensure that the appropriate dietary requirements of the animals are being met. Make sure they are up-to-date, for example ask for their Feed Adviser Register (FAR) card. Guidance on legislation regarding diets is available from the Food Standards Agency.

You can reduce the amount of nitrogen excreted by your cattle by matching (as closely as possible) the nitrogen content of diets to the expected level of production and the particular growth stage of the stock. The aim should be to achieve general good health and welfare and feed optimisation to improve nitrogen use efficiency.

Consider the following techniques for reducing ammonia emissions through diet selection and management and improved feed efficiency:

- use a qualified nutritionist to formulate rations for cattle, taking account of breed type, gender, stage of production and the quality of feeds available on the farm

- know the dietary crude protein (CP) content of home grown forage. Where possible, this should involve regular, representative sampling of Total Mixed Rations (TMR) and/or feeds with variable CP content (such as fresh grass and silage).

- consider the farm-specific situation: higher and successful CP reductions (2-3 percentage units) can be achieved more easily in TMR-based feeding systems. For example, CP content can be decreased from 18 to 15% (dry matter basis) in housed early lactation dairy cows fed a maize-silage based TMR with no negative effect on production[footnote 7].

- establish the protein requirements of your animals and adjust or balance feed accordingly

- consider phase feeding where possible

5.2 Cattle housing

You can reduce ammonia emissions by reducing the exposed surface area of the waste and reducing the movement of air over the waste. Consider these techniques for reducing ammonia emissions from your cattle housing, particularly when refurbishing or constructing new buildings:

- regularly wash and scrape floors

- design floors to drain effectively so urine and slurry are not allowed to pool

- frequently transfer slurry to a suitable store. Ensure grit and sediment are regularly removed from slurry channels and collection systems.

- grooved floors with perforations can channel urine and improve drainage. Scrapings should occur at least twice daily.

- reduce the surface area of the slatted area. Maximise the transfer of excreted material to channels, preferably with a 50% covering. Solid floor areas should have provisions such as a slight slope to allow urine to drain to the channels. Channels should be emptied frequently by the use of scrapers (unless designed to drain by gravity), a vacuum system or by flushing with water, untreated liquid manure (under 5% dry matter) or separated slurry.

- avoid ventilation directly above the surface of the slurry in the channels. Minimise the velocity of the air over the surface of the manure. Where this is unavoidable, the gap between the slats and the manure surface should be sufficiently large to minimise drafts across the surface.

- reduce the pH of the slurry (acidification). See Section 3.1.

- increase the amount of straw used per animal for bedded systems. Straw can soak up urine and help to keep floors dry, preventing pooling of urine. The appropriate amount of straw depends on the breed, feeding system, housing system and climate conditions.

5.3 Where to get more advice

The Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board (AHDB) have produced a range of relevant guidance including ‘Dairy housing: A best practice guide’ and ‘Feeding growing and finishing cattle for better returns’, available as free PDF downloads.

Tried & Tested have produced guidance on feed planning for sheep and cattle: you can download this.

Further information on the ways to reduce ammonia emissions through ruminant feed (p20-23) and from cattle housing (p27-32) can be found in the UNECE Framework Code for Good Agricultural Practice for Reducing Ammonia Emissions.

6. Pig sector-specific measures

6.1 Pig diet

Before making adjustments to the diets of your livestock, you may wish to seek advice from a registered feed adviser to ensure that the appropriate dietary requirements of the animals are being met. Make sure they are up-to-date, for example ask for their Feed Adviser Register (FAR) card. Guidance on legislation regarding diets is available from the Food Standards Agency.

You can reduce the amount of nitrogen excreted by your pigs by matching (as closely as possible) the nitrogen content of diets to the expected level of production and the particular growth stage of the stock. The aim should be to achieve general good health and welfare and feed optimisation to improve nitrogen use efficiency. Consider the following techniques for reducing ammonia emissions through diet selection and management and improved feed efficiency:

- improve feed conversion to weight gain and reduce feed surplus by adopting high standards of management and welfare and monitoring feed and water intake and growth rate

- match the nutrient requirements at all stages of production to improve the precision of nutrient supply. Consider options such as multi-phase and single-sex feeding as ways of improving the precision of nutrient supply, thus reducing waste and emissions.

- pig nutritionists can help to regularly review diets and adjust least-cost formulations to meet nutrient requirements. Consider professionally formulated diets, containing synthetic amino acids, enzymes and other feed additives to help reduce nutrient excreted. For example, evidence suggests that a decrease of 1% in dietary crude protein in the diet of finishing pigs results in a 10% reduction in total ammoniacal nitrogen (TAN) content of the pig slurry and 10% lower ammonia emissions[footnote 8].

6.2 Pig housing

You can reduce ammonia emissions by reducing the exposed surface area of the waste and reducing the movement of air over the waste. Consider these techniques for reducing ammonia emissions from your pig housing, particularly when refurbishing or constructing new buildings (ensuring that any changes are compatible with the housing system and allow for adequate ventilation):

- reduce the surface area of the slatted area. Maximise the transfer of excreted material to channels, preferably with a 50% covering. Solid floor areas should have provisions such as a slight slope to allow urine to drain to the channels. Channels should be emptied frequently by the use of scrapers, a vacuum system or by flushing with water, untreated liquid manure (under 5% dry matter) or separated slurry. Using metal or plastic-coated slats (which are less sticky for manure) will ensure the emission reductions are achieved.

- avoid ventilation directly above the surface of the slurry in the channels. Minimise the velocity of the air over the surface of the manure. Where this is unavoidable, the gap between the slats and the manure surface should be sufficiently large to minimise air velocity. This should be at least 30 cm.

- reduce the exposed surface of the slurry beneath the slats. V-shaped gutters (maximum 60 cm wide, 20 cm deep) reduce the surface emitting areas. Gutters and walls should be smooth to prevent manure build up.

- reduce the pH of the slurry (acidification). See Section 3.1.

- improve animal behaviour and design of pens. Offer pigs functional areas for different activities with the aim to keep the solid part of the floor as clean as possible. For example, pens with partially slatted floors should be designed so that pigs can distinguish separate areas for lying, eating, dunging and exercising.

- systems using bedding material such as straw should have sufficient bedding material to allow complete absorption of urine and be changed frequently

- slatted and solid floor systems should use sloped floors, gutters, trays or scrapers where possible to allow for rapid drainage so that urine and faeces are kept separate as ammonia emissions form when they mix

- leakages of drinking systems should be avoided to prevent additional moistening of the bedding. Drinking systems need to be designed so that the drinkers are at the correct height for the size of animals and may need to be adjustable. Nipple drinkers need to be adjusted for the desired flow rate for the water pressure present. Pipe work and drinkers need to be maintained to prevent leakage. All of these actions are necessary to prevent water wastage and prevent floors and bedding from getting wet.

- use of acid scrubbers or bio trickling filters to remove ammonia from the air. These devices are fitted to the outlets of mechanically ventilated pig housing and some systems can reduce ammonia emissions in exhaust air by up to 90%.

6.3 Where to get more advice

Pig units with over 2,000 places for production pigs (over 30kg) and/or over 750 places for sows must comply with permit conditions set by the Environment Agency under the Environmental Permitting Regulations. In order to meet these conditions, farms must use the techniques in The Best Available Techniques Reference Document for the Intensive Rearing of Poultry or Pigs (BREF) for avoiding or minimising all types of emissions. The BREF can also be used as voluntary guidance for the rest of the sector and you can download it from the European Commission website.

7. Poultry sector-specific measures

7.1 Poultry diet

Before making adjustments to the diets of your livestock, you may wish to seek advice from a registered feed adviser to ensure that the appropriate dietary requirements of the animals are being met. Make sure they are up-to-date, for example ask for their Feed Adviser Register (FAR) card. Guidance on legislation regarding diets is available from the Food Standards Agency.

You can reduce the amount of nitrogen excreted by your poultry by matching (as closely as possible) the nitrogen content of diets to the expected level of production and the particular growth stage of the stock. The aim should be to achieve general good health and welfare and feed optimisation to improve nitrogen use efficiency.

Consider the following techniques for reducing ammonia emissions through diet selection and management:

- improve feed conversion to weight gain and reduce feed surplus by adopting high standards of management and welfare and monitoring feed and water intake and growth rate

- match the nutrient requirements at all stages of production to improve the precision of nutrient supply

- nutritionists can help to regularly review diets and adjust least-cost formulations to meet nutrient requirements

7.2 Poultry housing

Poultry housing should be kept as dry as possible as poultry manure and litter emit more ammonia when wet.

Consider these techniques for reducing ammonia emissions from your poultry housing, particularly when refurbishing or constructing new buildings:

Applicable to both layer and broiler housing:

- ventilate colony deep pit or channelled systems. This reduces the moisture content of the manure and litter.

- regularly check building structure and water drinkers to reduce any leaks and keep litter dry. More ammonia will be emitted if the litter becomes wet and then dried.

- use acid scrubbers or bio trickling filters to remove ammonia from exhaust air. A multistage scrubber is recommended because of the co-benefits in reducing ammonia and other particulate emissions. These can include substantial amounts of phosphorus and other elements which can be recycled as plant nutrients.

Applicable only to layer housing:

- use a belt system to collect and remove manure. Collect and remove manure frequently with manure belt system to covered storage outside the building. Intensively ventilated drying tunnels, inside or outside the building, can increase the dry matter content to 60%-80% in less than 48 hours. Ammonia emissions become significant when the manure is one to two days old and increase rapidly at five days old, therefore the removal frequency should be two or three times per week.

7.3 Where to get more advice

Poultry units with over 40,000 bird places must comply with permit conditions set by the Environment Agency under the Environmental Permitting Regulations. In order to meet these conditions, farms must use the techniques in The Best Available Techniques Reference Document for the Intensive Rearing of Poultry or Pigs (BREF) for avoiding or minimising all types of emissions. The BREF can also be used as voluntary guidance for the rest of the sector and you can download it from the European Commission website.

8. References

-

Bittman, S., Dedina, M., Howard, C.M., Oenema, O. and Sutton, M.A., 2014. Options for ammonia mitigation: Guidance from the UNECE Task Force on Reactive Nitrogen. NERC/Centre for Ecology & Hydrology. You can download this for free from the CLRTAP website. ↩

-

UK National Atmospheric Emissions Inventory (NAEI) 2018. ↩

-

Committee on the Medical Effects on Air Pollutants (COMEAP) 2009. ‘Long-term exposure to air pollution: effect on mortality’. ↩

-

Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC) 2017. UK Biodiversity Indicators 2017: Air Pollution. ↩

-

Sutton, M.A., Reis, S., Riddick, S.N., Dragosits, U., Nemitz, E., Theobald, M.R., Tang, Y.S., Braban, C.F., Vieno, M., Dore, A.J. and Mitchell, R.F., 2013. Towards a climate-dependent paradigm of ammonia emission and deposition. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 368(1621) 20130166. ↩

-

Rothamsted Research after Nicholson, F.A., Bhogal, A., Chadwick, D., Gill, E., Gooday, R.D., Lord, E., Misselbrook, T., Rollett, A.J., Sagoo, E., Smith, K.A. and Thorman, R.E., 2013. An enhanced software tool to support better use of manure nutrients: MANNER‐NPK. Soil Use and Management, 29(4), pp.473-484. ↩

-

AHDB Dairy, 2016. Effect of dietary crude protein and starch concentration on milk production, heal and reproduction in early lactation dairy cows. Report prepared for Agriculture and Development Board Dairy by Sinclair, K.D., Homer, E.M., Wilson, S., Mann, G.E., Garnsworthy, P.C. and Sinclair, L.A. University of Nottingham and Harper Adams University. ↩

-

Canh, T.T., Aarnink, A.J.A., Schutte, J.B., Sutton, A., Langhout, D.J. and Verstegen, M.W.A., 1998. Dietary protein affects nitrogen excretion and ammonia emission from slurry of growing–finishing pigs. Livestock Science, 56(3), pp.181-191. ↩