Work, health and disability green paper: improving lives

Updated 30 November 2017

Ministerial foreword

From Damian Green, Secretary of State for Work and Pensions and Jeremy Hunt, Secretary of State for Health

This government is determined to build a country that works for everyone. A disability or health condition should not dictate the path a person is able to take in life – or in the workplace. What should count is a person’s talents and their determination and aspiration to succeed.

However, at the moment, for many people, a period of ill health, or a condition that gets worse, can cause huge difficulties. For those in work, but who are just managing, it can lead to them losing their job and then struggling to get back into work. Unable to support themselves and their family, and without the positive psychological and social support that comes from being in work, their wellbeing can decline and their health can worsen. The impact of this downward spiral is felt not just by each person affected and their families, but also by employers who lose valuable skills and health services that bear additional costs. There is a lack of practical support to help people stay connected to work and get back to work. This has to change.

We know that the right type of work is good for our physical and mental health and good health and support helps us in the workplace. We know that we must protect those with the most needs in society. We need a health and welfare system that recognises that – one that offers work for all those who can, help for those who could and care for those who can’t.

The UK has a strong track record on disability rights and the NHS provides unparalleled support to people with poor health. We have put mental and physical health on the same footing. We have seen hundreds of thousands more disabled people in work in recent years. However, despite that progress, we are not yet a country where all disabled people and people with health conditions are given the opportunity to reach their potential. That’s why we are committed to halving the disability employment gap and share this commitment with many others in society.

We are bold in our ambition and we must also be bold in action. We must highlight, confront and challenge the attitudes, prejudices and misunderstandings that, after many years, have become engrained in many of the policies and minds of employers, within the welfare state, across the health service and in wider society. Change will come, not by tinkering at the margins, but through real, innovative action. This Green Paper marks the start of that action and a far-reaching national debate, asking: ‘What will it take to transform the employment prospects of disabled people and people with long-term health conditions?’

This government is committed to acting but we can’t do it alone. Please get involved. Let’s ensure everyone has the opportunity to go as far as their talents will take them – for a healthier, working nation.

Work, health and disability: facts and figures

Evidence shows that appropriate work is good for our health. Good work leads to good health, and good health allows for good work. Also, worklessness leads to poor health, and poor health often leads to worklessness.

Reducing long term sickness absence is a priority 1.8 million employees on average have a long-term sickness absence of 4 weeks or more in a year.

Access to timely treatment varies across areas. Average waiting times for mental health treatment can differ by as much as 12 weeks across England and some evidence suggests treatment for musculoskeletal conditions can differ by as much as 23 weeks.

Ill-health among working age people costs the economy £100 billion and sickness absence costs employers £9 billion a year

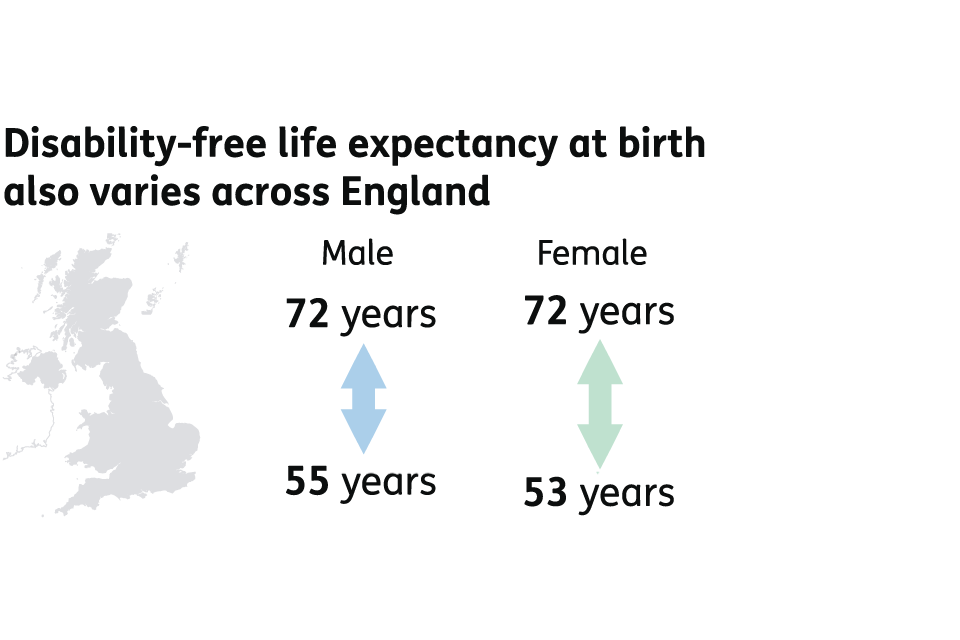

Disability-free life expectancy at birth also varies across England. For men, disability-free life expectancy can range from 55 to 72 years. For women, disability-free life expectancy can range from 53 to 72 years.

Only around 3 in 100 of all Employment and Support Allowance claimants leave the benefit each month.

Disability has been rising over 400,000 increase in the number of working age disabled people in the UK since 2013 taking the total to more than 7 million.

Compared to non-disabled people, disabled people are less likely to enter employment, so preventing them from leaving work is important. Between two quarters of a year, as many as 150,000 disabled people leave employment.

8% of employers report they have recruited a person with a disability or long term health condition over a year.

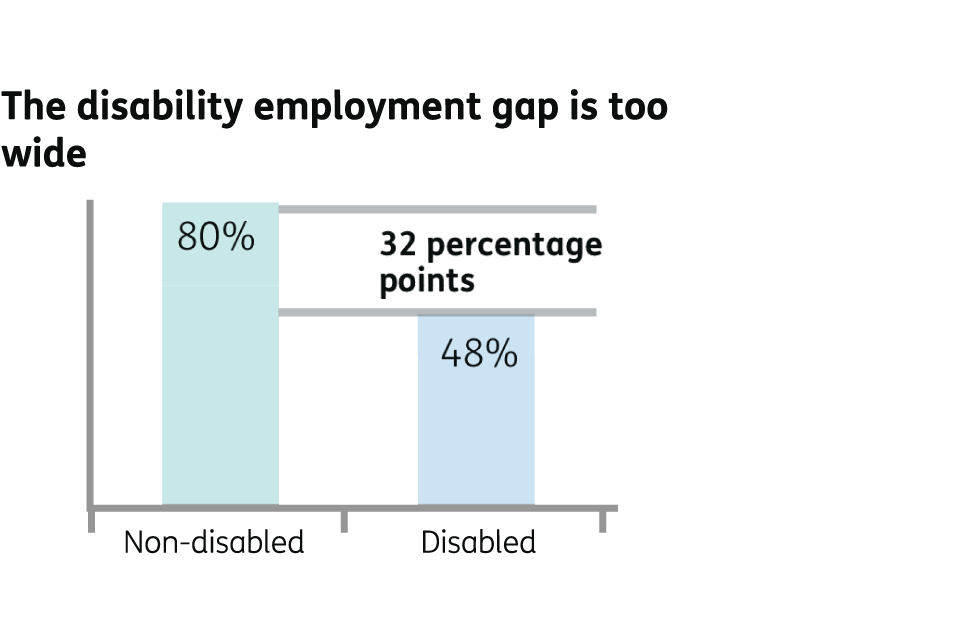

The disability employment gap is too wide. 80 per cent of non-disabled people are in employment, compared to 48 per cent of disabled people. That is a difference of 32 percentage points.

Executive summary

1) Employment rates amongst disabled people reveal one of the most significant inequalities in the UK today: less than half (48%) of disabled people are in employment compared to 80% of the non disabled population. [footnote 1] [footnote 2] Despite a record-breaking labour market, 4.6 million disabled people and people with long-term health conditions are out of work [footnote 3] leaving individuals, and some large parts of communities, disconnected from the benefits that work brings. People who are unemployed have higher rates of mortality [footnote 4] and a lower quality of life. [footnote 5] This is an injustice that we must address.

2) This green paper sets out the nature of the problem and why change is needed by employers, the welfare system, health and care providers, and all of us. We consider the relationship between health, work and disability. We recognise that health is important for all of us, that it can be a subjective issue and not everyone with a long-term health condition will see themselves as disabled. [footnote 6] We set out some proposed solutions and ask for your views on whether we are doing the right things to ensure that we are allowing everyone the opportunity to fulfil their potential.

The nature of the problem

3) Making progress on the government’s manifesto ambition to halve the disability employment gap is central to our social reform agenda by building a country and economy that works for everyone, whether or not they have a long-term health condition or disability. It is fundamental to creating a society based on fairness: people living in more disadvantaged areas have poorer health and a higher risk of disability. It will also support our health and economic policy objectives by contributing to the government’s full employment ambitions, enabling employers to access a wider pool of talent and skills, and improving health.

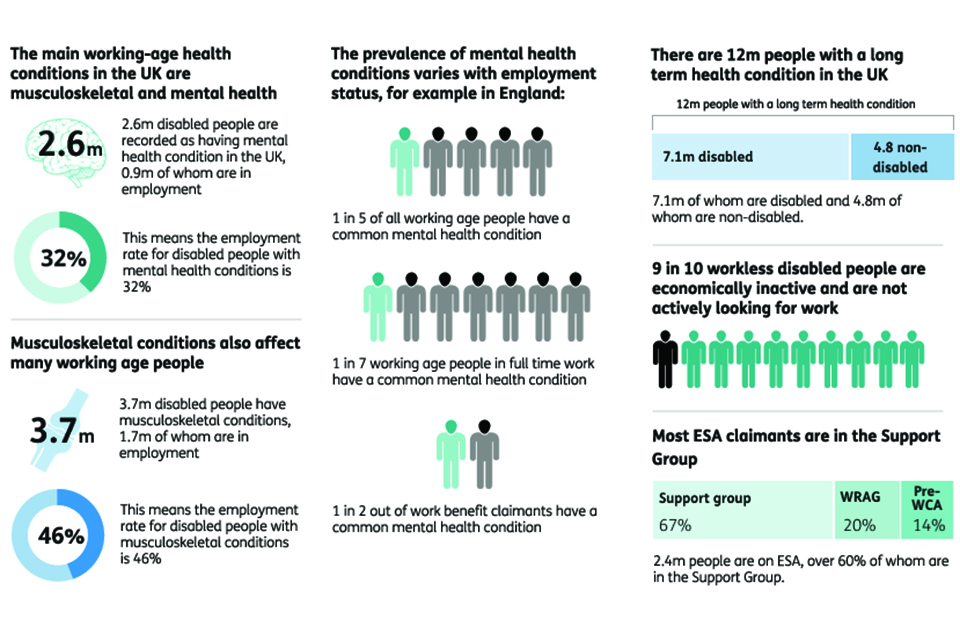

4) Almost 1 in 3 working-age people in the UK have a long-term health condition which puts their participation in work at risk. [footnote 7] Around 1 in 5 of the working-age population has a mental health condition. [footnote 8] As many as 150,000 disabled people who are in work one quarter are out of work the next. [footnote 9] Over half (54%) of all disabled people who are out of work experience mental health and/or musculoskeletal conditions as their main health condition. [footnote 10] It is evident that our health and welfare systems are struggling to provide meaningful support, and, put simply, the system provides too little too late. Too many people are falling into a downward spiral of declining health and being out of work, denying them the benefits that employment can bring, creating pressures on the NHS and sustaining a major injustice in our society.

5) Over 3.3 million disabled people are now in work. [footnote 11] Yet many disabled people experience expectations that are too low, employers who can be reluctant to give them a chance, limited access to services and a welfare system that does not provide enough personalised and tailored support to help people into work and to stay in work. Too many people experience a fragmented and disjointed system which does little to support their ambitions of employment, and indeed can erode those ambitions.

6) The evidence that appropriate work can bring health and wellbeing benefits is widely recognised. [footnote 12] Employment can help our physical and mental health and promote recovery. But the importance of employment for health is not fully reflected in commissioning decisions and clinical practice within health services, and opportunities to support people in their employment aspirations are regularly lost. Once people are on benefits, their chances of returning to work steadily worsen. There are systemic issues with the original design of Employment and Support Allowance with 1.5 million people now in the Support Group [footnote 13] who are treated in a one-size-fits-all way and get little by way of practical support from Jobcentres to help them into work. This consultation seeks to address these issues, exploring new ways to help people, but does not seek any further welfare savings beyond those already legislated for.

Areas for action

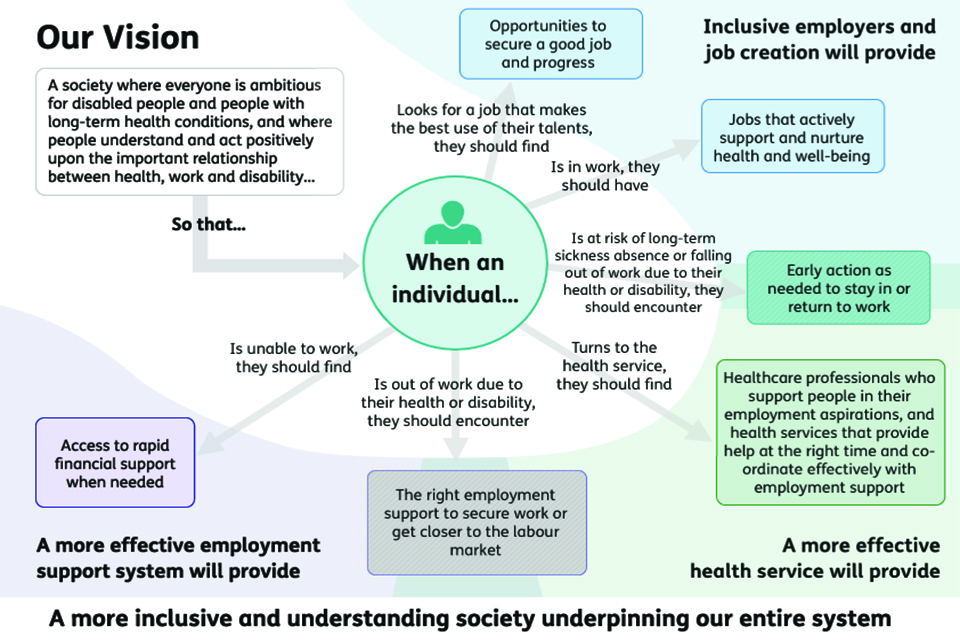

7) These challenges are complex and pressing. Our vision is to create a society in which everyone has a chance to fulfil their potential, where all that matters is the talent someone has and how hard they are prepared to work. We are determined to remove the long-standing injustices and barriers that stop disabled people and people with health conditions from getting into work and getting on, preventing them from being whatever they want to be. We are also determined to bring a new focus to efforts to prevent health conditions from developing and worsening, helping more people to remain in work for longer.

We want to:

- ensure that disabled people and people with long-term health conditions have equal access to labour market opportunities and are given the support they need to prevent them from falling out of work and to progress in workplaces which embed effective health and wellbeing practices

- help employers take action to create a workforce that reflects society as a whole and where employers are equipped to take a long-term view on the skills and capability of their workforce, managing an ageing workforce and increased chronic conditions to keep people in work, rather than reacting only when they lose employees

- ensure people are able to access the right employment and health services, at the right time and in a way which is personalised to their circumstances and integrated around their needs

- more effectively integrate the health and social care and welfare systems to help disabled people and people with long-term health conditions move into and remain in sustainable employment

- put mental and physical health on an equal footing, to ensure people get the right care and prevent mental illness in the first place

- invest in innovation to gain a better understanding of what works, for whom, why and at what cost so we can scale promising approaches quickly

- change cultures and mind-sets across all of society: employers, health services, the welfare system and among individuals themselves, so that we focus on the strengths of disabled people and what they can do

8) Taken together, this will mean the ambitions of disabled people and people with health conditions, their aspirations and their needs, are supported by more active, integrated and individualised support that wraps around them. This will help improve health and wellbeing, benefit our economy and enable more people to reach their potential.

9) To make early progress we are:

- working jointly across the whole of government: this green paper is jointly prepared by the Department of Health and the Department for Work and Pensions, working closely with the Department for Communities and Local Government, the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, NHS England, Public Health England, local government, and other partners

- significantly improving our employment support: for example, expanding the number of employment advisers in talking therapies and introducing a new Personal Support Package offering tailored employment support which Jobcentre Plus work coaches will help disabled people or people with health conditions to access

- working with health partners such as NHS England, Public Health England, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Health Education England, the Royal Colleges and regulators to embed evidence into clinical practice and support training and education across the NHS workforce

- investing £115 million of funding to develop new models of support to help people into work when they are managing a long-term health condition or disability. We will identify and rapidly scale those which can make a difference, while weeding out less promising approaches

10) We will not be satisfied with this, and further action needs to be sustained across all sectors. In this green paper we ask:

- how big a role can we expect employers to play in ensuring access to opportunities for disabled people, and how can the ‘business case’ for inclusive practices be strengthened? What is the best way to influence employers to support health and wellbeing in the workplace, both to ensure the effectiveness of their workforce and avoid employment practices which can negatively impact health? How can we prevent sickness absence resulting in detachment from the labour market?

- how can work coaches play a more active role for disabled people and people with health conditions? How can we build their skills and capabilities to support a diverse group with complex needs, build their mental health awareness, and develop a role in personalising support and helping individuals navigate a complex system?

- how can we improve a welfare system that leaves 1.5 million people – over 60% of people claiming Employment and Support Allowance [footnote 14] – with the impression they cannot work and without any regular access to employment support, even when many others with the same conditions are flourishing in the labour market? How can we build a system where the financial support received does not negatively impact access to support to find a job? How can we offer a better user experience, improve system efficiency in sharing data, and achieve closer alignment of assessments?

- how can we promote mental and physical health and ensure that people have timely access to the health and employment support that they need rather than struggling to access services (particularly musculoskeletal and mental health services)? How do we make sure that health and employment service providers provide a tailored and integrated service, and that the important role of employment is recognised?

- how can we develop better occupational health support right across the health and work journey?

- what will it take to reinforce work as a health outcome in commissioning decisions and clinical practice? How can we ensure good quality conversations about health and work, and improve how fit notes work?

- how can we best encourage, harness and spread innovation to ensure that commissioners know what works best in enabling disabled people and people with health conditions to work?

- perhaps most crucially, how can we build a culture of high hopes and expectations for what disabled people and people with long-term health conditions can achieve, and mobilise support across society?

11) This challenge is not one that will be solved quickly, but we know that to build a country that works for everyone, we must address issues with a long-term return. This is why we have a 10-year vision for reform, the foundations of which we have set out at the end of this consultation. Where we are certain of our ground we will act quickly, making the changes we know are needed. But we will also look to the long term, investing in innovation to understand what is most effective and reshaping services where they are needed.

Your views

12) The consultation on the proposals in this green paper is an important part of building a shared vision and achieving a real change in culture. We want to launch a discussion around how we can best support disabled people and people with long-term health conditions to get into, and to stay in, work. We want to bring together wide-ranging expertise, opinions and experiences. Over the coming months we will talk to disabled people and people with long-term conditions, their families and carers, health and social care professionals, their representative bodies, local and national organisations, employers, charities and anyone who, like us, wants change.

13) We recognise that the devolution administrations are important partners, particularly because of their responsibilities for health as a devolved matter and other related areas. The government is committed to working with the devolved administrations to improve the support accessible to disabled people and people with health conditions across the country at a national, local and community level.

14) Please let us know what we need to improve so that we can build a plan that will bring real and lasting change. You can:

Respond to this consultation online

Email us at workandhealth@dwp.gsi.gov.uk

Write to us at:

The Work, Health and Disability consultation,

Ground Floor,

Caxton House,

6-12 Tothill Street,

London,

SW1H 9NA

The consultation will run until Friday 17 February 2017.

15) We are committed to tackling the injustice of disability employment, so that all can share in the opportunities for health, wealth and wellbeing that the UK has to offer and where everyone has the chance to go as far as their talents will take them.

Definition of disability and long-term health conditions used in this paper:

- The Equality Act 2010 [footnote 15] defines a disabled person as someone who has a physical or mental impairment which has a substantial and long-term adverse effect on their ability to carry out normal day-to-day activities. ‘Long-term’ is defined as lasting or expecting to last for at least 12 months

- health can be a subjective issue – we know that the way people think about their health is diverse and that not everyone that meets the Equality Act definition would consider themselves to be disabled. But we follow the Equality Act definitions in this paper, so:

- an individual is considered in this paper as having a long-term health condition if they have a physical or mental health condition(s) or illness(es) that lasts, or is expected to last, 12 months or more.

- if a person with these condition(s) or illness(es) also reports it reduces their ability to carry out day-to-day activities as well, then they are also considered to be disabled

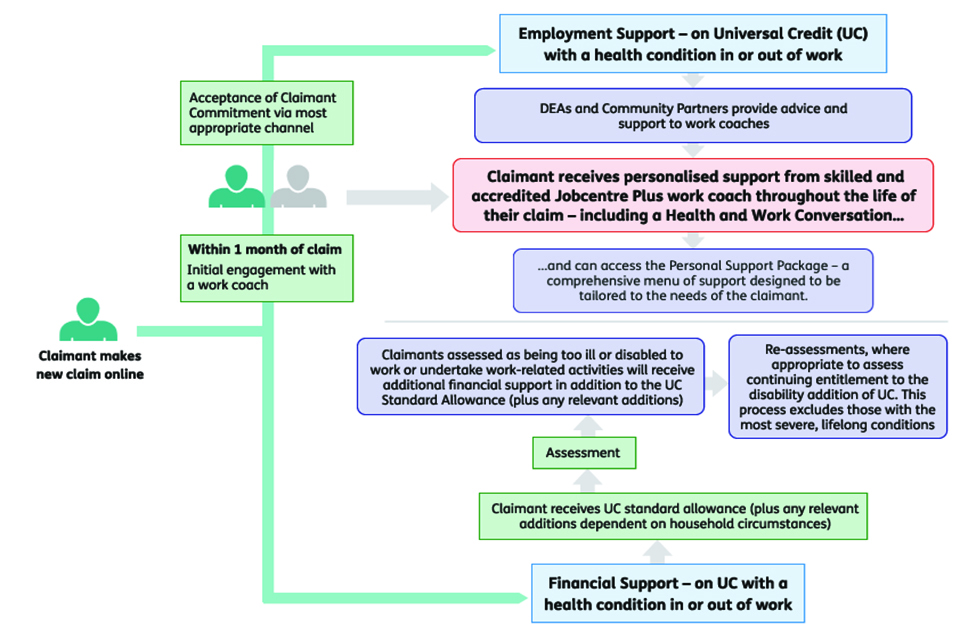

- this means some people who may have a long-term health condition will be grouped together with those people who do not have any long-term health condition and be considered as non disabled. We recognise that long-term health conditions can fluctuate and the effects of a condition on an individual’s day-to-day activities may change over time

- incapacity Benefits refers to Employment and Support Allowance and its predecessors Incapacity Benefit, Income Support on grounds of disability and Severe Disablement Allowance

1: Tackling a significant inequality – the case for action

Chapter summary

In this chapter we set out the injustice of the disability employment gap. We explore how:

- being in work can help an individual’s health and wellbeing

- systemic issues hold back too many disabled people and people with health conditions

- we need to learn from what works and develop innovative approaches

- we need to work beyond artificial boundaries and work with everyone to achieve our shared vision

Being in work can help an individual’s health and their overall wellbeing

16) This government is committed to helping everyone, whoever they are, enjoy the independence, security and good health that being in work can bring, giving them the chance to be all they want to be.

17) The evidence is clear that work and health are linked. Appropriate work is good for an individual’s physical and mental health. Being out of work is associated with a range of poor health outcomes. [footnote 16] Academics and organisations such as the WHO, [footnote 17] the ILO, [footnote 18] the OECD, [footnote 19] RAND Europe, [footnote 20] the Royal College of Psychiatrists [footnote 21] and NICE [footnote 22] all recognise that work influences health and health influences work. The workplace can either support health and wellbeing and the health system can actively support people into work in a virtuous circle or the workplace can be unsupportive and health and work systems can work against each other.

18) We know that the longer a person is out of work the more their health and wellbeing is likely to deteriorate. [footnote 23] So, every day matters. For every week, every month, every year someone remains outside the world of work, it is increasingly more difficult for them to return and their health and wellbeing may worsen as a result. We must address this downward spiral.

19) Of course, work can also bring a range of other benefits which support mental and physical health and wellbeing. [footnote 24] It is the best route to raising the living standards of disabled people and people with a long-term health condition and moving them out of poverty. [footnote 25] But a good standard of living is about more than just income. [footnote 26] Work can help someone to be independent in the widest sense: having purpose, self-esteem, and the opportunity to build relationships. Being in the right job can be positively life changing.

20) But, whilst work is good for health in most circumstances, the type of work matters. Many factors such as autonomy, an appropriate workload and supportive management are important for promoting health at work. [footnote 27] These factors can be very personal.

21) As many stakeholder organisations like Scope have highlighted, many disabled people and people with long-term health conditions already work and many more want to access all the benefits that work can bring. [footnote 28] We want to understand how to improve the current system of support to make this aspiration a reality. We also recognise that some disabled people and people with health conditions might not be able to work due to their condition, whether in the short or long term. This government is committed to ensuring that they are fully supported by the financial safety net that the welfare system provides and so this consultation does not seek any further welfare savings beyond those in current legislation.

…and there’s quite significant benefits associated with work over and above the financial benefit of working, the social aspects of it, things to do with people’s self-esteem, so trying to keep people plugged into that is very important for their overall health.” [footnote 29] - General Practitioner

I don’t have to work financially, but I want to… self-confidence, self-worth….” [footnote 30] - Individual

Closing the disability employment gap to tackle injustice and build our economy

See appendix for full description of this image: Population characteristics

22) This government is committed to building a country and an economy that work for everyone. The UK employment rate is the highest it has been since records began. Over 31 million people (nearly 75% of the working age population) are in employment. [footnote 31] However, while there has been an increase of almost half a million disabled people in employment over the last 3 years, there are still fewer than 5 in 10 disabled people in employment compared with 8 in 10 non-disabled people. [footnote 32] This disability employment rate gap, the difference between the employment rates of disabled and non-disabled people, has not changed significantly in recent years and now stands at 32 percentage points. [footnote 33] [footnote 34]

23) So 3.8 million disabled people are out of work despite a record breaking labour market. [footnote 35] People with particular health conditions can be disadvantaged, for example only 32% of people with mental health conditions are in employment. This leaves people, and in some places entire communities, disconnected from the benefits that work can bring. This is one of the most significant inequalities in the UK today and the government cannot stand aside when it sees social injustice and unfairness. That is why we have set ourselves the ambition to halve the disability employment gap.

24) This ambition is not only about tackling an unacceptable injustice for individuals. The disability employment gap also represents a waste of talent and potential which we cannot afford as a country: poor health and unemployment results in substantial costs to the economy.

25) The cost of working age ill health among working age people is around £100 billion a year. [footnote 36] The majority of this cost arises from lost output among working age people with health conditions not being in paid work. Economic inactivity costs government around £50 billion a year, including £19 billion of welfare benefit payments and lower tax revenues and national insurance contributions. The NHS also bears £7 billion of additional costs for treating people with conditions that keep them out of work. [footnote 37] And there is also a cost to employers: sickness absence is estimated to cost £9 billion per year. [footnote 38] And, of course, there is a cost to people and their families.

Action is needed now to prevent this situation getting worse

26) We have seen that the costs, to the individual and the economy, of the disability employment gap are already unacceptably high. Trends in demography and population health mean that we need to take action now to prevent these costs rising further.

27) Older people will make up a greater proportion of the workforce in the future. Between 2014 and 2024 the UK will have 200,000 fewer people aged 16 to 49 but 3.2 million more people aged 50 to State Pension age. [footnote 39] Older workers can bring great benefit to businesses and drawing on their knowledge, skills and experience may help businesses to remain competitive and to avoid skills and labour shortages.

28) We also know that while life expectancy at birth has been increasing year on year, changes in healthy life expectancy have not consistently been keeping pace: we are living longer lives but some more years in ill health. [footnote 40] There is a known correlation between an ageing population and an increasing prevalence of long-term chronic conditions and multiple health issues.

29) We know that the world of work is changing. For example, new information and communication technologies have changed the nature of work tasks. This change may bring benefits, for example enabling more flexible working to help people with health conditions stay in work, but can also have less positive effects like work intensification that may affect people’s ability to cope or adapt in work with a health condition. [footnote 41]

30) The impact of poor health on work is not inevitable for people at any age. For example, advances in technology can assist people to remain in work where they might have been previously unable to do so. Lifelong learning can also offer the opportunity for people to gain new skills to change roles if they develop a health condition or disability, or an existing one worsens. [footnote 42] And while many conditions are not preventable, the evidence is clear that the way we live our lives can influence health outcomes. Currently, 6 out of 10 adults are overweight or obese, [footnote 43] nearly 1 in 5 adults still smoke, [footnote 44] and more than 10 million adults drink alcohol at levels that pose a risk to their health. [footnote 45] Public health interventions form a vital part of the health and work agenda to help reduce the prevalence of conditions that can lead to people leaving the labour market due to ill health.

Case study – Susannah

Susannah was diagnosed with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis in 2010, she had lived with symptoms for more than 6 months before getting a formal diagnosis. She has lived a very active life and was working on a farm in France at the time of diagnosis. Following diagnosis, Susannah returned to the UK and now works as the personal assistant at a country house and estate.

Upon receiving her diagnosis, her employer was quite understanding of the impact rheumatoid arthritis was having on her. Her manager spoke with the HR team who provided her with reasonable adjustments to her workplace. Fatigue is also major issue for Susannah, as with many others with rheumatoid arthritis, she feels very tired after a day at work and this limits her from socialising in the evenings or at weekends. Nevertheless, she admits she does have some difficulties with her workload but she does not feel comfortable asking her employer for further adjustments to it.

In light of her current difficulties she is planning to retire early, having originally planned to retire at 66. She says she has accumulated enough earnings to have a reasonable retirement. When asked if anything could accommodate her to remain in work and thus not retire, she says working 3 days rather than 4 would probably be sufficient, however, she says this would amount to a job share which would be impractical for her employer and something she is not prepared to ask for.

Retiring early isn’t ideal and I would like to keep on working but I just can’t perform all of the roles of the job anymore and my work-life balance has suffered due to my tiredness and pain at the end of each day. I don’t see my friends much anymore and it’s something I really miss. If I could work a 3-day week I could probably carry on, but I don’t feel that is something which could be accommodated. Before my diagnosis I never contemplated having to retire early but now I see it as almost inevitable.

– Provided by National Rheumatoid Arthritis Society

Underlying factors play an important role

31) To reduce the disability employment gap, we need to understand the reasons why disabled people might be unable to enter or stay in work, and to recognise the wide variety of conditions and circumstances they face. The disability employment gap is affected by a number of factors, for example people frequently move in or out of disability and employment over time. It is therefore important to look at a wider group of work and health indicators to allow us to better understand the wider picture. The Work, Health and Disability Green Paper Data Pack accompanying this publication includes more statistics about the disability employment gap.

32) Almost 12 million working age people in the UK have a long-term health condition, and of these 7 million are disabled. [footnote 46] A health condition does not, in itself, necessarily prevent someone from working. Indeed people with a long-term health condition who are not reported as being disabled have a very similar employment rate to people without any type of health condition – around 80%. [footnote 47] However, employment rates are much lower among disabled people with only 48% in work. [footnote 48]

33) This suggests that it is important to try to prevent long-term health conditions developing or worsening to the extent that they are disabling. We know that a person’s health is affected by the conditions and environments in which they live. Fair Society, Healthy Lives [footnote 49] provided evidence that the conditions in which people are born, live, work and age, are the fundamental drivers of health and health inequalities. Where people live can have a big impact on both health and employment outcomes. In England, men born in the most deprived areas can expect 9.2 fewer years of life, and 19.0 fewer years of life lived in good health than people in the least deprived areas. For women the equivalent figures are 7.0 and 20.2 years. [footnote 50]

34) We also know that disabled people from more disadvantaged backgrounds are more likely to be out of work. For example, while employment rates can be as low as 16% for people with mental health conditions who live in social housing, for disabled people who live in a mortgaged house and who have 1 or 2 health conditions, the employment rate is as high as 80%. [footnote 51] This is similar to the overall employment rate for non-disabled people. [footnote 52]

35) In addition to the strong links between socio-economic disadvantage and poorer work and health outcomes, other factors can also be significant. Attitudes in society can have a significant impact: for example, people may have lower expectations of disabled people and people with health conditions, which may impact on whether an individual feels able to work. There may also be physical barriers to employment for some disabled people and people with long-term health conditions, such as difficulties accessing transport and buildings.

36) We also need to recognise that some disabled people or people with long-term health conditions may face other disadvantages associated with worklessness. They may need a wide range of support, through different agencies working in partnership, to address all of the connected and overlapping problems they face. These might include drug or alcohol addiction, a criminal record, homelessness or caring responsibilities for young children. We recognise that these are complex problems, requiring a focused look at the factors that stand in the way of employment for these groups, which is why the government has asked Dame Carol Black to conduct an independent review into the impact on employment outcomes of alcohol or drug addiction, and obesity.

37) Although factors unrelated to an individual’s health condition or disability have a significant impact on their ability to work, there do appear to be some patterns in employment rates for people with certain conditions, or for those who have multiple conditions. For example, disabled people with mental health conditions have an employment rate of just 32%, which is significantly below the overall employment rate for disabled people at 48%. [footnote 53] People who have more than one condition are also more likely to be out of work – disabled people with one long-term health condition have an employment rate of 61%, but the 1.2 million disabled people who have 5 or more long-term health conditions have an employment rate of just 23%. [footnote 54]

38) Of course not all health conditions are static. Many, such as some mental health conditions, fluctuate over time, and affect people differently at different times. What is clear, though, is that once someone is out of work due to a health condition and claims Employment and Support Allowance their chance of finding work is slim. Only around 3 in 100 of all people receiving Employment and Support Allowance stop receiving the benefit each month, and not all of these people return to work. [footnote 55] While the government recognises that some people will not be able to work and rightly need to receive financial support, for others this starts a journey away from work which can make their health problems worse and, in turn, negatively impact upon their employment prospects.

39) It is impossible to address this complex picture with a simple, one-size-fits-all solution. We need to change our attitudes and behaviours towards disabled people and people with health conditions, working with everyone from employers to schools, health professionals to community groups. We need to develop a more personalised and integrated system that puts individuals at the centre, and gives all individuals the chance to prosper and play their part in a country and an economy that works for everyone.

Tackling the systemic issues

40) The disability employment gap has persisted over many years and its causes are long-term, systemic and cultural. Efforts to help disabled people and those with long-term health conditions have been hindered by a lack of vision and by systems which fail to join up and take people’s needs properly into account.

41) A number of systemic issues hold back too many disabled people and people with health conditions:

- employees are not being supported to stay healthy when in work, and to manage their health condition to stop them falling out of work: in one report, mental ill health at work was estimated to cost businesses £26 billion annually through lost productivity and sickness absence [footnote 57]

- too many disabled people and people with long-term health conditions are being parked on financial support alone: over 60% of people on Employment and Support Allowance do not have access to integrated and personalised employment and health support which focuses on what they can and want to do

- individuals are not getting access to the right support and treatment: for example, some evidence suggests that waiting times for musculoskeletal services can vary from between 4 to 27 weeks [footnote 58]

- the health and welfare systems do not always work well together to join up around an individual’s needs and offer personalised and integrated support to help them manage their condition.

42) Our strategy is to provide support centred on the disabled person or person with a health condition. Disabled people and people with health conditions are the best judges of what integrated support they need to secure work or stay and flourish in work. To do this, we want to align systems better so that we can make a real difference to people’s health and work prospects. In this green paper we explore how we can encourage employers, the welfare system and health services to take a more joined-up approach to health and work:

- how we can encourage employers to be confident and willing to recruit disabled people, to put in place approaches to prevent people from falling out of work, and to support effectively those employees on a period of sickness absence to encourage their return to work

- how we can create a welfare system that provides employment support in a more personalised and tailored way, with a simpler and more streamlined process for those with the most severe health conditions

- how we can create a health system where work is seen as a health outcome and where all health professionals are sufficiently trained and confident to have work-related conversations with individuals to increase their chances of maintaining or returning to employment

- how we can better integrate occupational health type support with other services to ensure more holistic patient care

43) We also need to look beyond ‘systems’ to look at the important role played by individuals, carers and the voluntary and community sectors.

The role of individuals

44) Disabled people, people with long-term health conditions and those who may develop them are at the heart of our strategy. We want to deliver services which enable people to have more information about their care and support, be better able to manage any health conditions, and have more say in the health and employment support they may need. The patients’ organisation National Voices puts it clearly: personalised care will only happen when services recognise that patients’ own life goals are what count; that services need to support families, carers and communities; that promoting wellbeing and independence need to be the key outcomes of care; and that patients, their families and carers are often ‘experts by experience’. [footnote 59]

45) Individuals can also support employers to make workplaces more inclusive by working in partnership with them to deliver changes in recruitment and retention practices and promoting a healthy work culture.

The role of carers

46) This government recognises that carers can play a fundamental role in enabling disabled people and people with long-term health conditions to be all they want to be. The support of carers can be crucial in supporting disabled people and people with a long-term health condition to return to or remain in work. According to a report from 2009, [footnote 60] as many as 3 million people combine paid work with providing informal care to family and friends who might have a range of physical or learning disabilities, or who may have long-term health conditions related to ageing.

47) Carers UK recently found that carers in England are ‘struggling to get the support they need to care well, maintain their own health, balance work and care, and have a life of their own outside of caring.’ The challenges of balancing paid work with a caring role can mean that carers have to reduce their working hours, pass up career opportunities, or leave employment altogether: an estimated 2 million people have given up paid work to care. [footnote 62] Of these, there are currently 315,000 working age adults who, having left work to care, remain unemployed after their caring role has ended. These impacts are felt disproportionately by older workers, with around 1 in every 6 economically inactive people aged between 50 and State Pension age citing caring responsibilities as the reason for inactivity. [footnote 63]

48) Many of the challenges faced by carers in balancing their work and caring roles stem from the same issues faced by workers who are themselves disabled or have a long-term health condition, for example a risk-averse attitude among employers to recruiting disabled people and caring responsibilities, and a lack of flexible working arrangements in many organisations. Changing attitudes and behaviours towards disabled people and people with long-term health conditions should also have a positive impact on carers, but there is more to be done.

49) The government is committed to supporting carers. A key objective of our future work will be to support carers of all ages to enter, remain in and re-enter work. The government’s Fuller Working Lives programme focuses on the challenges for older workers to remaining in or returning to work due to caring responsibilities, ill health or disability. As part of the programme a series of Carers in Employment pilots was launched in April 2015, to help support carers to stay in work or return to paid work alongside their caring responsibilities. Early next year the government will publish a new, cross-government and employer-led national strategy, which will set out the future direction of this Fuller Working Lives agenda.

The role of the voluntary and community sectors, local authorities and other local partners

50) We recognise that the voluntary and community sectors play a crucial role in helping more people to lead healthy and fulfilling lives, and that there are many organisations from these sectors, with broad reach and diversity, working to support and involve disabled people and people with long term health conditions. These voluntary and community organisations embody a spirit of citizenship upon which our country is built, and we want to better harness their expertise and capacity in order to achieve the best outcomes for disabled people and people with long-term health conditions.

51) As a government, we are already working to invest in, and partner with, the voluntary and community sectors, including:

- the Department of Health, NHS England and Public Health England, working closely with the sectors, have published a co-produced review of investment and partnerships in the sector. The review contains a range of recommendations for the department, the wider health and care system and the sectors. From this review, work is underway to progress recommendations and to promote more integrated working between the statutory and voluntary sectors to improve health and wellbeing outcomes

- the Office for Civil Society is providing £20 million of funding through its Local Sustainability Fund, to help voluntary, community and social enterprise organisations review and transform their operating models to develop more sustainable ways of working

- the National Citizen’s Service is a programme open to all 16 and 17-year-olds in England, giving them the opportunity to develop the skills and attitudes needed to engage with their local communities and become active and responsible citizens

52) When it comes to unlocking the potential of disabled people and people with long-term health conditions, we want to build on these strong foundations, as well as on the many successful programmes and initiatives led by the voluntary and community sectors themselves, to deliver real change.

53) By being close to their users, charities have ‘a unique perspective on their needs and how to improve services’. [footnote 64] As advocates and providers of services, the voluntary and community sectors form an essential part of achieving lasting change and bringing about a new approach to work and health support. The voluntary and community sectors can help drive change by speaking out for people and their needs, both to the public sector and wider society. The sectors also have an important role in service delivery and have already demonstrated successful programmes such as peer support programmes and mentoring networks, which help people understand and manage their disabilities and health conditions, and explore ways to get into and remain in work. We want to build on these strong foundations to deliver real change.

54) Part of the reason the voluntary and community sectors are so important is because of their links with and reach within their local communities. Evidence shows that employment outcomes for disabled people and people with long-term health conditions vary across different regions in the country. [footnote 65] There are significant opportunities to advance this agenda through a ‘place-based’ approach, unlocking the political capital and resources needed to drive innovation and deliver the system-wide response needed to improve outcomes and local growth. It is also important that employment support for those furthest from the labour market plays an active role in helping people get back to work and unlocking productivity in places. Approaches to integrating work and health provision should draw on the strategic intelligence of Local Enterprise Partnerships and building on the existing strengths of local employers. Better outcomes for disabled people and people with long-term health conditions will require a concerted partnership between communities, central government departments, local authorities, Local Enterprise Partnerships, local providers, and devolution partners.

55) Ultimately, stronger engagement, partnership and co-production with the voluntary and community sectors forms a central part of our work if we are to reach disabled people and people with long term health conditions within their local communities, better understand their experiences with services, listen fully to what they as individuals want to achieve, and offer them support that is rounded, tailored and easily accessible.

The role of the devolved administrations

56) We recognise that services and support for disabled people and people with long-term health conditions needs to join up more effectively and holistically around the needs of the individual. Devolution, with the ability it brings to make decisions and formulate policy at a localised level, plays a key part in this ambition. The devolved administrations are important partners in developing appropriate local solutions, particularly because of their responsibilities for health as a devolved matter. The government is committed to working with the devolved administrations and devolution deal areas to improve the support accessible to disabled people and people with health conditions across the country at a regional, local and community level.

Case study: Working with deaf children

I lost my hearing progressively from early childhood and as it deteriorated it became harder to participate and I felt increasingly isolated and dependent. I became acutely aware that people had different expectations of me because I was deaf. However, I didn’t see myself, or my capabilities, as any different from my hearing friends. “I struggled in the workplace as I was increasingly unable to use the phone and found meetings challenging. I was fortunate to have excellent support from colleagues that I worked with in the civil service and from speech to text reporters, made possible by the government’s Access to Work scheme. In 2006, I had cochlear implant surgery and thanks to the technology and the habilitation support that I received afterwards, I was able to ‘re-enter’ the hearing world, grow my confidence at work and in social situations. This enabled me to have a successful career in the senior civil service.

The speech and language therapists at St Thomas’ Hospital in London provided me with the support to make sense of the new sounds that I was able to access through my hearing technology. Without such support, I would not benefit from the investment that the NHS makes in these wonderful devices. Habilitation is key.

I am now Chief Executive of a charity that works with deaf children and their families to provide critical support in the early years of their lives. This includes enabling them to develop the listening and spoken language skills that gives them an equal start at school and enables them to access the same opportunities in life as their hearing peers. Auditory verbal therapy is a parent coaching programme delivered by highly specialist speech and language therapists who have undergone an additional 3 years of training in auditory verbal practice. Our oldest graduates of the programme are now entering the world of university and work – equipped with the skills to succeed.

– Anita Grover, Chief Executive, Auditory Verbal UK. Provided by the Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists

Achieving lasting change: investing in innovation

57) Change on this scale will take time to achieve and not everything we try will work. Success demands we take an innovative, experimental approach to test a wide range of approaches in different environments and learn quickly, shifting focus early from any failures and moving rapidly to scale up successful approaches. It means working with a wide range of people to identify where we should focus our efforts. And we should look to capture the impacts across the whole of government, where possible, to build the case for future investment and help us influence a wider range of actors. Having a clear idea of what works in what context will enable us to:

- focus our resources on services and commissioning models which have the most impact

- influence commissioners of services to make the right decisions to invest in different support to meet local population needs

- provide employers with information about successful approaches and spread best practice

58) We want to take early action to build our evidence base on what works in the areas that we already know are important. We start with a solid understanding of some of key principles based on evidence from past delivery. For instance, evidence suggests that when a person faces both health and employment barriers, both should be addressed simultaneously, since there is no evidence that treating either problem in isolation is effective. [footnote 66] As an example, Individual Placement and Support, an integrated health and employment model, has demonstrated improved employment outcomes for those with severe and enduring mental health condition. A UK evaluation found that chances of finding employment doubles for those who received this service. [footnote 67]

59) We also know that evidence gaps exist, in particular:

- how best to support those in work and at risk of falling out of work, including the part employers can play

- understanding how best to help those people in the Employment and Support Allowance Support Group who could and want to work (discussed further in chapter 2)

- the settings that are most effective to engage people in employment and health support

- how musculoskeletal treatment and occupational health interventions improve employment outcomes

60) We have a range of activity underway that is focused on the evidence gaps we have identified, including access to services and levels of support we should offer. This will help us to develop new models of support to help people into work when they are managing a long-term health condition or disability.

61) As part of this our £70 million Work and Health Innovation Fund, jointly managed by the Work and Health Unit and NHS England, will support promising local initiatives to drive integration across the health, care and employment systems. The first areas we will work with are West Midlands Combined Authority and Sheffield City Region. Seed funding will be provided to support the design trials to test new approaches at scale and understand if they can improve employment and health outcomes. Following this design phase, we plan to review these proposals and decide if they are viable for implementation, with access to further funding and national support available to enable full implementation from spring 2017.

62) By bringing local Clinical Commissioning Groups, Jobcentre Plus and local authorities into new partnerships these trials will create new support pathways for people with common physical and mental health conditions to help them stay in or return to work.

63) Alongside this, we are testing a range of approaches to improve outcomes for people with common mental health conditions, who make up 49% of those on Employment and Support Allowance. [footnote 68] We want to rapidly scale up those which show they can make a real impact. Trials include testing interventions that offer faster access to treatment and support services, co-locating employment support in a health setting and building on the evidence for Individual Placement and Support to understand if this is a model which can work successfully for people with common mental health conditions.

64) Examples of this approach include the Mental Health Trailblazers. These combine a specific type of employment support, Individual Placement and Support, with psychological support provided through the NHS talking therapy services in 3 areas: Blackpool, West London and the North East.

65) As set out in the 2015 Spending Review, there are opportunities to make use of Social Impact Bonds to help people with mental health problems. Social investment offers an exciting new opportunity to draw on both private capital and voluntary and community sector innovation to test and scale new forms of support. We are reviewing how Social Impact Bonds can be best used across our range of innovation activity and will invest up to £20 million on work and health outcomes. The Government Inclusive Economy Unit will explore the possible role of existing or new public service mutuals, which already operate to good effect in the health and care sectors

66) We recently launched our Small Business Challenge Fund to encourage small businesses in developing small-scale innovative models for supporting small and medium-sized enterprises with sickness absence. This approach will allow us to use a small amount of funding to identify promising interventions and prototypes to take forward to more robust testing.

67) We aim to build on this Challenge Fund approach to develop small-scale innovative approaches to quickly understand which may work and fail fast on those which do not. Such an approach is likely to be most useful where there is limited evidence, such as supporting small and medium-sized employers with sickness absence, or where there is already a market of innovators, such on digital health technologies. We are particularly interested to use the consultation process to identify key areas where such an approach may be appropriate.

68) Finally, it is important we share information on what works widely to support local delivery. To do this, we will work with Public Health England to develop a set of work and health indicators and identify how we can best bring together and share the existing evidence for local commissioners and delivery partners. We will continue to draw on a range of internal and external evidence, including trials and research, the academic literature and relevant third sector organisations to improve policy making and delivery nationally and locally.

Your views

69) We are committed to building a pipeline of innovation to rapidly improve support for individuals. As part of this we will be developing a structured evidence base so that we know what works, and we recognise that there will be rich sources that have already been developed or are being drawn together by others. We want to hear from you about areas you are already exploring or have learnt from:

- what innovative and evidence-based support are you already delivering to improve health and employment outcomes for people in your community which you think could be replicated at scale? What evidence sources did you draw on when making your investment decision?

- what evidence gaps have you identified in your local area in relation to supporting disabled people or people with long-term health conditions? Are there particular gaps that a Challenge Fund approach could most successfully respond to?

- how should we develop, structure and communicate the evidence base to influence commissioning decisions?

Respond to this consultation online

Building a shared vision

70) This green paper sets out the pressing case for action, and the systemic challenges we face. Achieving our vision will require us to work beyond artificial system boundaries and work with those in our local communities. We will also need to be innovative and test new ways of doing things.

See appendix for full description of this image: Our vision

71) This green paper discusses a number of areas where we want to see change to make systems work better for people. It considers:

- supporting more people into work (chapter 2)

- assessments for benefits for people with health conditions (chapter 3)

- supporting employers to recruit with confidence and embed a healthy working culture in the workplace (chapter 4)

- supporting employment through health and high quality care for all (chapter 5)

72) Chapter 6 discusses the vital role all of us can play in delivering the changes we want to see, and sets out how you can respond to this consultation. The involvement of employers, local government, practitioners, providers, advocacy groups, carers, disabled people, and people with long-term health conditions is vital. Please let us know what we need to improve so that we can build a plan that will bring real and lasting change.

Summary of consultation questions

We are committed to building a structured evidence base so that we know what works and recognise that there will be rich sources that have already been developed or are being drawn together by others. We want to hear from you about areas you are already exploring or have learnt from:

- what innovative and evidence-based support are you already delivering to improve health and employment outcomes for people in your community which you think could be replicated at scale? What evidence sources did you draw on when making your investment decision?

- what evidence gaps have you identified in your local area in relation to supporting disabled people or people with long-term health conditions? Are there particular gaps that a Challenge Fund approach could most successfully respond to?

- how should we develop, structure and communicate the evidence base to influence commissioning decisions?

Respond to this consultation online

2: Supporting people into work

Chapter summary

In this chapter we focus on how we can best provide employment support to disabled people and people with health conditions. It explores:

- our vision for how people can access an integrated network of health and employment support delivered from a range of sectors, supported by a dedicated Jobcentre Plus work coach who can work closely with someone to build a relationship and offer personalised support that is tailored to their needs

- how we are investing in the skills and capabilities of Jobcentre Plus work coaches to enable them to better support people with a wide range of health conditions, including mental health conditions, bringing in external expertise

- our new Personal Support Package, including an enhanced menu of employment support for work coaches to draw on

- how we can better engage with people placed in the Employment and Support Allowance Support Group or the Universal Credit Limited Capability for Work and Work-Related Activity Group (LCWRA). We will undertake research and a trial to better understand how we can support individuals to move closer to the labour market and into employment, where appropriate

Introduction

73) We want everyone to have the opportunity to benefit from the positive impacts that work can have, including on their health and wellbeing. Where people want to work, and have the potential to do so immediately or in the future, we should do everything we can to support them towards their goal. We want people to be able to access appropriate, personalised and integrated support at the earliest opportunity, which focuses on what they can do, builds on their talents and addresses their individual needs.

74) Where someone is out of work as a result of a health condition or a disability, the employment and health support they receive should be tailored to their personal needs and circumstances. This support might be delivered by a range of partners in their local area, such as by Jobcentre Plus, contracted provision, local authorities or third sector providers. Increasingly, our work coaches across Jobcentre Plus will assess an individual’s needs and ensure that they access the right help. Work coaches will be supported by new Community Partners and Disability Employment Advisers, who will be able to use their networks and expertise to work with local organisations, to support disabled people and people with health conditions to achieve their potential.

75) Universal Credit is already making improvements which put people at the heart of the welfare system, giving more personalised and integrated support from a dedicated work coach in Jobcentre Plus to help claimants with a health condition move closer to the labour market and get into work. It will also, for the first time, help those claimants with health conditions who are already in work to progress in the labour market supporting them to earn more. Evaluation has found people receiving Universal Credit are more likely to move into employment and move into work quicker than similar individuals receiving Jobseeker’s Allowance. [footnote 69] To ensure that disabled people and people with health conditions receive the best possible support, we will introduce a new Personal Support Package for people with health conditions in Jobcentre Plus, with a range of new interventions and initiatives designed to provide more tailored support.

76) However, further action is needed to build on the principles Universal Credit has introduced. We cannot make significant progress towards halving the disability employment gap with a system that treats 1.5 million people [footnote 70] – the current size of the Support Group in Employment and Support Allowance – in a one-size-fits-all way. The current approach does not do enough to treat people as individuals: more must be done to ensure that people do not miss out on accessing the wealth of local, integrated support available through Jobcentre Plus. We will achieve this by identifying evidence gaps, building on insights from trials and drawing on the knowledge of both service users and providers.

77) In this chapter we will discuss 2 key themes:

- Universal Credit is moving in the right direction, but there is still more to do to improve how work coaches systematically engage with disabled people and people with health conditions. We want to identify the most effective support based on a person’s circumstances and the capabilities required in Jobcentre Plus to deliver these interventions. Work coaches will also be able to offer an array of targeted support as part of the Personal Support Package summarised below

- the current one-size-fits-all approach to employment support is not appropriate. This is because people in the Employment and Support Allowance Support Group, and those with ‘Limited Capability for Work and Work Related Activity’ (LCWRA) in Universal Credit, do not routinely have any contact with a Jobcentre Plus work coach. We are committed to protecting those with the most needs, but want to test how we might offer a more personalised approach to employment support, which reflects the wide variety of conditions and needs within this group and is in keeping with Universal Credit principles.

We are introducing the new Personal Support Package for people with health conditions. This is a range of new measures and interventions designed to offer a package of support which can be tailored to people’s individual needs.

The offer, set out in more detail in this chapter, includes the following new forms of support for all Employment and Support Allowance claimants (and Universal Credit equivalents):

- personal support from disability trained, accredited work coaches. A particular focus of training will be mental health. Work coaches will also be better supported by an extra 300 Disability Employment Advisers and around 200 new Community Partners, with disability expertise and local knowledge. This will lead to better signposting to other local voluntary and public sector services

- a Health and Work Conversation for everyone claiming Employment and Support Allowance, as appropriate

For new claimants in the Employment and Support Allowance Work-Related Activity Group (ESA WRAG), and the equivalent Universal Credit Limited Capability for Work Group (UC LCW), an enhanced offer of support will also include:

- a place on either the new Work and Health Programme or Work Choice, for all eligible and suitable claimants who wish to volunteer

- additional places on the Specialist Employability Support programme

- Job Clubs delivered via peer support networks

- work experience places, with wrap-around support, for young people

- increased funding for the Access to Work Mental Health Support Service

- Jobcentres reaching out to employers, particularly small employers, to identify opportunities and help match people to jobs in a new Small Employer Offer

We will continue to develop the offer by:

- trialling the use of specialist medical advice to further support work coaches

- working with local authorities to pilot an approach to invest in Local Supported Employment for disabled people known to social care, notably those with learning disabilities and autism, and secondary mental health service users

- testing a Jobcentre-led alternative to Specialist Employability Support

- trialling additional work coach interventions

Action already taken

78) There is a significant amount of work already underway to strengthen and improve the employment support offer available to disabled people and people with health conditions. These activities are explored in more detail within the chapter, and include:

- Universal Credit – replacing 6 benefits with 1, the introduction of Universal Credit will make a significant difference in improving the level and quality of support offered to individuals with health conditions

- expansion of the Disability Employment Adviser role – we are recruiting an additional 300 Disability Employment Advisers, taking the total to 500

- permitted work – from April 2017, we will remove the 52-week limit on how long Employment and Support Allowance claimants placed in the Work-Related Activity Group (WRAG) are able to work for. This will improve work incentives for this group

- the Work and Health Programme – following the end of the Work Programme, this provision will be available to disabled people receiving Employment and Support Allowance or Universal Credit on a voluntary basis from October 2017

Universal Credit and the financial benefits of work

79) It is essential to ensure that people are better off in work. Under Universal Credit, people can more clearly see the financial benefits of moving into work, allowing them to take small steps into the labour market and to work flexibly in line with their needs.

80) In Universal Credit, for people who have ‘limited capability for work’ (LCW) or ‘limited capability for work and work related activity’ (LCWRA), there is a work allowance for earned income. This means that someone assessed as having LCW or LCWRA, with housing costs, can earn up to £192 a month, and a similar person, without housing costs, can earn up to £397 a month, in both cases without affecting their Universal Credit payment. For any earnings above these allowances, the Universal Credit 65% taper applies, which means that only 65% of the extra earnings above those allowances are deducted from the claimant’s Universal Credit entitlement - a steady and predictable rate as people gradually increase their hours and earn more, rather than the cliff-edge approach of Employment and Support Allowance. This is particularly well suited for people whose disability or health condition means they can only work some of the time.

81) Individuals on Employment and Support Allowance are allowed to work up to 16 hours and earn up to £115.50 a week and keep all of their benefit. If earnings exceed this amount, Employment and Support Allowance stops altogether. The permitted work rules allow people claiming Employment and Support Allowance to undertake some part-time work without it impacting on their benefit, to encourage them to gradually build their employment skills and return to work. However for those in the Work-Related Activity Group this is limited to 52 weeks. We will remove this limit from April 2017 to bring the Employment and Support Allowance rules more into line with Universal Credit and improve the incentive to work.

Early engagement

82) Being better off in work is not enough on its own if disabled people and people with health conditions are not being enabled to find work in the first place. Universal Credit ensures that people with health conditions still have an opportunity to engage with a work coach prior to their Work Capability Assessment, where appropriate. This approach builds on evidence that early intervention can play an important role in improving the chances of disabled people and people with a health condition returning to work. [footnote 71]

83) This is a significant improvement on the current process in Employment and Support Allowance, where people are not routinely having a face-to-face conversation with a work coach about practical support to help them back to work until after their Work Capability Assessment is complete – and this can be many months after their initial claim. Over 60% of the 2.4 million people receiving Employment and Support Allowance – those currently in the Support Group [footnote 72] – do not get this opportunity and often have no contact at all with a work coach and therefore do not access tailored support when they need it. We are missing a significant opportunity to provide help to people when they could benefit most.

84) This earlier engagement between an individual and a work coach in Universal Credit will also serve as a gateway to a wider, integrated system of support offered by the Department for Work and Pensions and other agencies, such as the NHS and local authorities. If a work coach identifies that someone has particularly complex barriers to work or complex health conditions, they will be able to advise individuals about other types of support in their local area – whether health services, skills courses or support with budgeting.

85) This builds on the approach of Universal Support, which helps people make and maintain their Universal Credit claim, and will assist people with their financial and digital capability throughout the life of their claim. This is delivered in partnership between the Department for Work and Pensions and local authorities, and with other local partners such as Citizens Advice and Credit Unions. Through Universal Support we are transforming the way Jobcentres work as part of their local communities to ensure they more effectively tackle the complex needs some people have and support them into sustainable employment. The Troubled Families programme offers another example of an integrated approach, with local authorities coordinating wider support services for complex families, including those with health conditions, and in doing so, driving public service reform around the needs of families. The Department for Work and Pensions provides work coaches acting as Troubled Family Employment Advisers, based within local authorities, where they play an important role in integrating employment support with the wider services.

###Building work coach capability

86) The relationship between a person and their work coach should be at the heart of each individual’s journey in the welfare system. To ensure that people with complex and fluctuating health conditions receive the most appropriate support, we will continue to build and develop the capability of our work coaches. We have introduced an accredited learning journey for work coaches, which includes additional mandatory training in supporting those with physical and mental health conditions. From 2017, we will introduce an enhanced training offer which better enables work coaches to support people with mental health conditions and more confidently engage with employers on the issue of mental health.

87) Work coaches will be supported by specialist Disability Employment Advisers. We are currently recruiting up to 300 more Disability Employment Advisers, taking the total to over 500. These advisers will work alongside work coaches to provide additional professional expertise and local knowledge on health issues, particularly around mental health conditions. The role will have a much stronger focus on coaching work coaches to help build their confidence and expertise in supporting individuals with a health condition or disability.

88) We also recognise the value of bringing external expertise into Jobcentres and of working more effectively with the voluntary sector in our design and delivery of support. We know that voluntary organisations have unique insight and expertise about the people they work with and their conditions, and we want to harness this. So, we will recruit around 200 Community Partners across Jobcentre Plus. These will be people with personal and professional experience of disability and many will be seconded from a Disabled People’s User-Led Organisation or disability charity. From next year, Community Partners will be working with Jobcentre Plus staff, to build their capability and provide valuable first-hand insight into the issues individuals with a health condition or disability face in securing and sustaining employment. Drawing on their local knowledge, they will identify more tailored local provision to ensure individuals with health conditions can benefit from the full range of support and expertise available. Community Partners will also engage with local employers to help improve the recruitment and retention of disabled people and people with health conditions.

89) Our Community Partners will map local services available in each of our Jobcentre Plus districts. This will include understanding where there are peer support and patient groups which engage with disabled people and people with long-term health conditions who might otherwise find it hard to re engage with employment, helping develop confidence and motivation. Where there are gaps in provision our districts may be able to make local decisions to fund any priority areas, using the Flexible Support Fund. We will be providing an extra £15 million a year in 2017/18 and 2018/19 for our Flexible Support Fund so that local managers can buy services including mentoring and better engage the third sector in their community. We will introduce a new Dynamic Purchasing System across the country by December 2016 which will allow third sector and other organisations to develop employment-related service proposals that Jobcentres can quickly contract for. Our goal is to extend the reach of Jobcentre Plus into third sector support groups which are already well established.

90) Often, the best advocates of the positive impact of being in work are people who themselves have had the experience of managing a serious health condition, or overcoming an employer’s prejudice about disability. We have already tested Journey to Employment peer support job clubs on a small scale, offering personalised support in a group environment delivered by people who have personal experience of disability, drawing on research by Disability Rights UK and the Work Foundation. These clubs often take place outside a Jobcentre as this provides an alternative setting which may be more effective for some individuals with health conditions. We are extending our Journey to Employment job clubs to 71 Jobcentre Plus areas with the highest number of people receiving Employment and Support Allowance, to further test the effectiveness of peer support job clubs at supporting those with health conditions.

Case study – Journey to Employment (J2E) Job Club

Jayne was employed, but life events affected her health and changed everything. Jayne joined the J2E Project in 2015 and she started her journey to recovery.

Describing her time before the Job Club, she said:

I shut down to protect myself and drew inward trying to block things in work. I didn’t feel I was functioning on ‘all cylinders’, my confidence was shot, I was checking up on what I was doing constantly and this spiralled out of control.

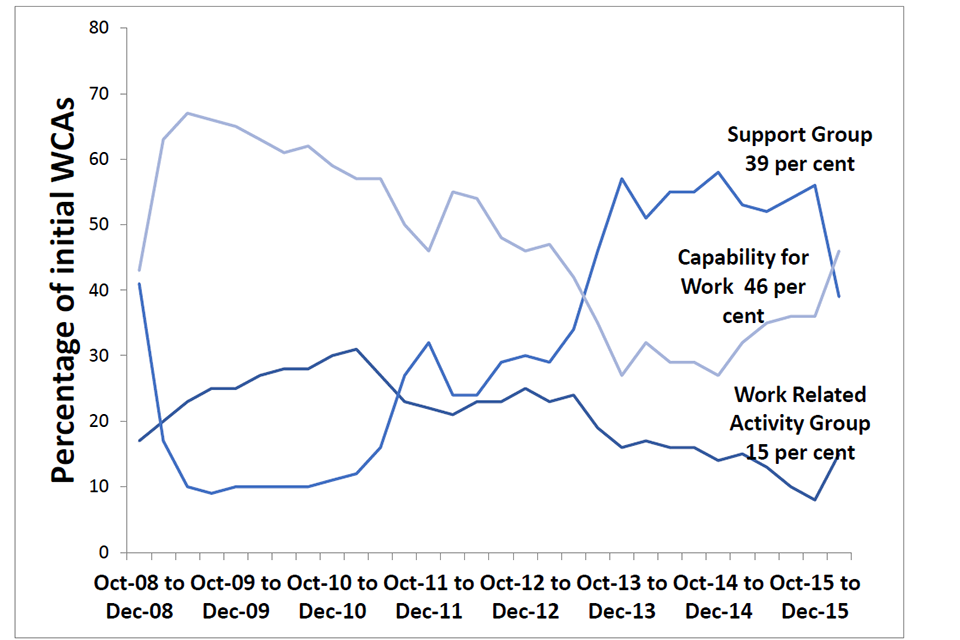

I felt I was in limbo I didn’t really know what I wanted to do, I could not afford not to work so felt confused about where go and who to seek help from. I was suffering with anxiety and terrible panic attacks, I was also depressed and can recognise now through help I have received and my own research that it was all due to the environment I was in.