Levelling-up and Regeneration Bill: reforms to national planning policy

Updated 19 December 2023

Applies to England

Scope of consultation

Topic of this consultation:

This consultation seeks views on our proposed approach to updating to the National Planning Policy Framework. We are also seeking views on our proposed approach to preparing National Development Management Policies, how we might develop policy to support levelling up, and how national planning policy is currently accessed by users.

A fuller review of the Framework will be required in due course, and its content will depend on the implementation of the government’s proposals for wider changes to the planning system, including the Levelling-up and Regeneration Bill.

Scope of this consultation:

The Department for Levelling Up, Housing, and Communities is seeking views on how we might develop new and revise current national planning policy to support our wider objectives. Full details on the scope of consultation are found within chapter 2. Chapter 14 contains a table of all questions within this document and signposts their relevant scope. In responding to this consultation, we would appreciate comments on any potential impacts on protected groups under the Public Sector Equality Duty. A consultation question on this is found in chapter 13.

Geographical scope:

These proposals relate to England only.

Basic information

Body/bodies responsible for the consultation:

The Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities

Duration:

This consultation will begin on 22 December 2022 and close at 11.45pm on 2 March 2023.

Enquiries:

For any enquiries about the consultation please contact: PlanningPolicyConsultation@levellingup.gov.uk.

How to respond

Please respond via Citizen Space which is the department’s online consultation portal and our preferred route for receiving consultation responses. We strongly encourage that responses are made via Citizen Space, particularly from organisations with access to online facilities such as local authorities, representative bodies and businesses. Consultations receive a high-level of interest across many sectors. Using the online survey greatly assists our analysis of the responses, enabling more efficient and effective consideration of the issues raised.

The online survey can be accessed on Citizen Space.

If you cannot respond via Citizen Space, you may send your response by email to: PlanningPolicyConsultation@levellingup.gov.uk.

Written responses should be sent to:

Planning Policy Consultation Team

Planning Directorate – Planning Policy Division

Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities

Floor 3, Fry Building

2 Marsham Street

London

SW1P 4DF

When you reply, it would be very useful if you please confirm whether you are replying as an individual or submitting an official response on behalf of an organisation and include:

- your name

- your position (if applicable)

- the name of organisation (if applicable)

Please make it clear which question or paragraph number each comment relates to, and also ensure that the text of your response is in a format that allows copying of individual sentences or paragraphs (please use paragraph numbers from the draft track change version of the National Planning Policy Framework published alongside this consultation which can be found here and not the existing paragraph numbers in the current Framework), to help us when considering your view on particular issues.

Thank you for taking time to submit responses to this consultation. Your views will help improve and shape our national planning policies.

Chapter 1 - Introduction

1. The government is committed to levelling up across the country, building more homes to increase home ownership, empowering communities to make better places, restoring local pride and regenerating towns and cities. The February 2022 Levelling Up White Paper reiterated the government’s commitment to making improvements to the planning system to achieve this, by giving communities a stronger say over where homes are built and what they look like. The Levelling-up and Regeneration Bill (the Bill) which is before Parliament will put the foundations in place for delivering this by creating a genuinely plan-led system with a stronger voice for communities. It will ensure greater provision of community infrastructure by developers, mandate that beautiful new development meets clear design standards that reflect community views, and enhance protections for our precious environmental and heritage assets.

2. The Bill begins to put communities at the heart of the planning system, offering communities beautiful homes and new neighbourhoods that they will welcome and a greater say in what is built and where. But the Bill is not the whole story: if we are to truly remake the planning system, we also need changes to national policy and guidance, regulations and wider support for local authorities, communities and applicants. This document sets out the improvements we propose to make to national planning policy to deliver this wider change.

3. The National Planning Policy Framework (the Framework) was introduced in 2012 to consolidate the government’s planning policies for England. It guides local decision makers on our national policy objectives, providing a framework within which locally prepared plans are produced, and clear national policies to be taken into account when dealing with planning applications and some other planning decisions. When a local planning authority brings forward a plan, they have a statutory duty to have regard to these national policies, and the Framework is therefore drafted with the expectation that plans will be consistent with the policies contained within it. The Framework is also a ‘material consideration’[footnote 1] in decision-taking. It is therefore vital that it reflects this government’s objectives for remaking the planning system as soon as possible.

4. We have therefore set out in this document specific changes that we propose to immediately make to the Framework (subject to and following consultation). These will allow us to swiftly deliver the government’s commitments to building enough of the right homes in the right places with the right infrastructure, ensuring the environment is protected and giving local people a greater say on where and where not to place new, beautiful development. They will also allow us to deliver cheaper, cleaner, more secure power in the places that communities want to see onshore wind. Specifically, this includes changes to:

- make clear how housing figures should be derived and applied so that communities can respond to local circumstances;

- address issues in the operation of the housing delivery and land supply tests;

- tackle problems of slow build out;

- encourage local planning authorities to support the role of community-led groups in delivering affordable housing on exception sites;

- set clearer expectations around planning for older peoples’ housing;

- promote more beautiful homes, including through gentle density;

- make sure that food security considerations are factored into planning decisions that affect farm land;

- and enable new methods for demonstrating local support for onshore wind development.

5. The proposed immediate changes are explained in this document. We are also publishing a tracked changes Framework document which this Prospectus should be read alongside. This sets out the detailed proposed policy wording that is indicative of what would be implemented immediately, subject to the results of this consultation. The government will respond to this consultation by spring 2023, publishing the Framework revisions as part of this, so that policy changes can take effect as soon as possible.

6. The government remains committed to delivering 300,000 homes a year by the mid-2020s and many of the immediate changes focus on how we plan to deliver the homes our communities need. We know that the best way to secure more high-quality homes in the right places is through the adoption of local plans. At present, fewer than half of local authorities have up-to-date plans (adopted in the past 5 years). Our proposed reforms create clear incentives for more local authorities to adopt plans. And our analysis shows that having a sound plan in place means housing delivery increases compared to those local authorities with an out-of-date plan, or no plan at all[footnote 2]. If communities know they can protect valuable green space and natural habitats as well as requiring new developments to be high quality and beautiful, plans are more likely to be both durable and robust.

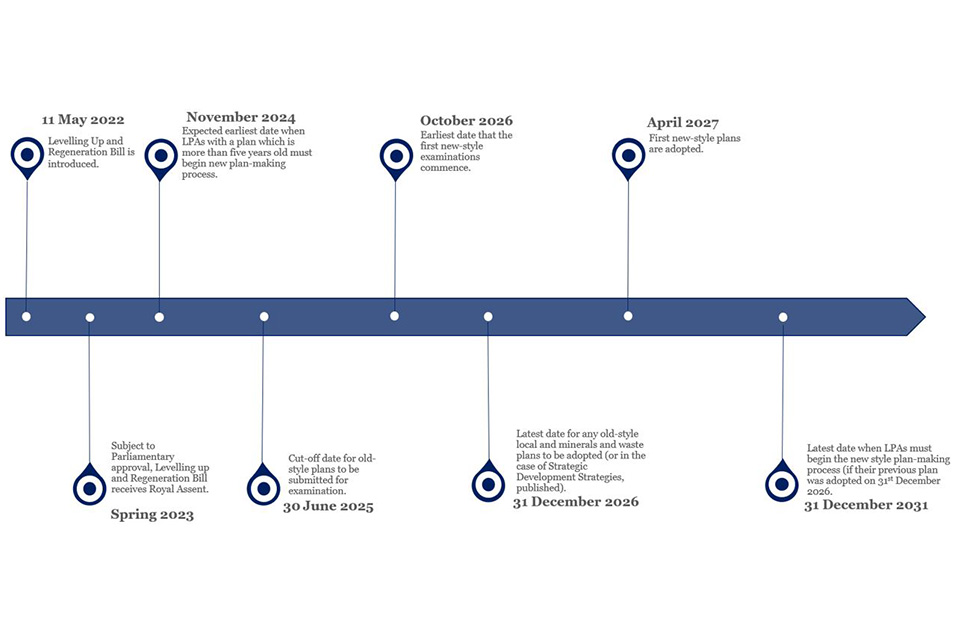

7. These changes are being proposed now to realise the housing supply benefits as soon as possible. In line with this, the government is clear that plan production should continue to progress and believes the changes will assist with this. In line with this, those authorities with up-to-date local plans will benefit from additional time to prepare new style plans that will be introduced through the Bill, as set out in our proposed timetable for transitioning to new-style plans set out in chapter 9 of this document.

8. Alongside these specific changes, this document calls for views on a wider range of proposals, particularly focused on making sure the planning system capitalises on opportunities to support the natural environment, respond to climate change and deliver on levelling up of economic opportunity, and signals areas that we expect to consider in the context of a wider review of the Framework to follow Royal Assent of the Bill. The government will consult on the detail of these wider changes next year, reflecting responses to this consultation.

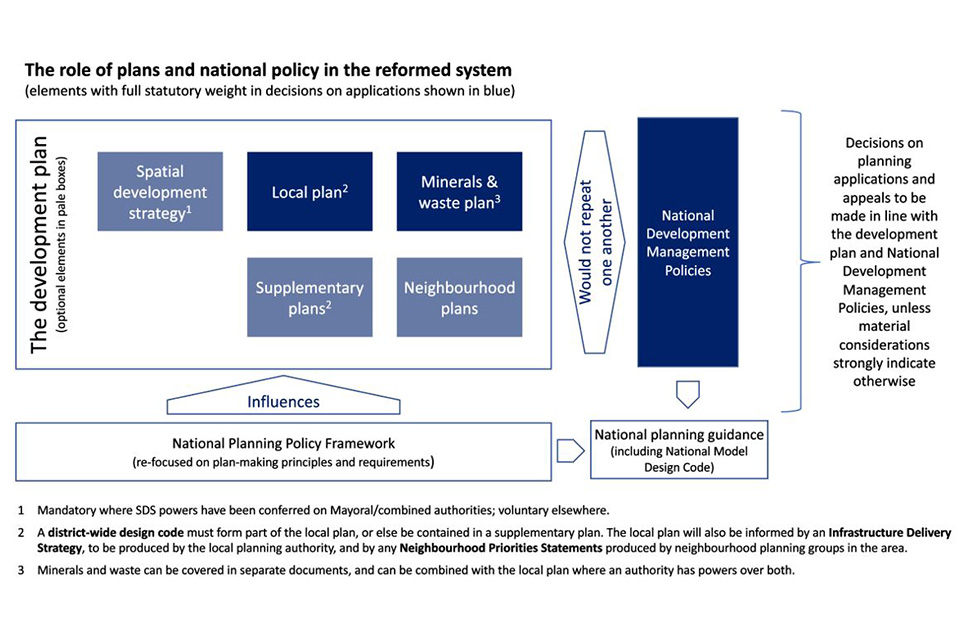

7. Finally, this document also sets out the envisaged role for National Development Management Policies (NDMPs). These are intended to save plan-makers from having to repeat nationally important policies in their own plans, so that plans can be quicker to produce and focus on locally relevant policies. National Development Management Policies should also provide more consistency for small and medium housebuilders, who otherwise must navigate a complex patchwork of similar but different requirements. We are proposing that National Development Management Policies are set out separately from the National Planning Policy Framework, which would be re-focused on principles for plan-making. This document calls for views on how we implement NDMPs and the government will consult on the detail next year ahead of finalising the position.

Chapter 2 - Policy objectives

1. The proposals in this document are designed to support our wider objectives of making the planning system work better for communities, delivering more homes through sustainable development, building pride in place and supporting levelling up more generally. They should be read alongside the policy paper which accompanied the introduction of the Levelling Up and Regeneration Bill published on 11 May.

2. Building beautiful and refusing ugliness: Good design and placemaking that reflects community preferences is a key objective of the planning system. We have taken steps to emphasise this, including changes made to the National Planning Policy Framework in July 2021 following the important recommendations of the Building Better, Building Beautiful Commission, and the publication of the National Model Design Code; changes which are already having positive effects on new development. The Bill will go further and require every local planning authority to produce a design code for its area. These will set simple clear minimum standards on development in that area – such as height, form and density. These codes will have statutory status when making decisions on development, either through forming part of local plans or being prepared as a supplementary plan. They will empower communities, working with local authorities, to have a say on what their area will look like by setting clear standards for new, beautiful development. The wider review of the Framework next year and accompanying consultation on National Development Management Policies will reflect and consolidate these changes.

3. Securing the infrastructure needed to support development: The Bill includes important measures to capture uplifts in land value more effectively through a new Infrastructure Levy, as well as powers to pilot land auctions as an alternative way for authorities to identify land suitable for planning permission. It will also support better planning for infrastructure through new Infrastructure Delivery Strategies. We propose to update the Framework through the wider review next year to support the implementation of these changes. They will ensure that development delivers the infrastructure that communities need and expect, including at least as much affordable housing as at present. Good infrastructure is also critical to support a changing and competitive economy, such as the development requirements brought about by the growth in ecommerce. More details will be set out in a future consultation on the details of the Infrastructure Levy.

4. More democratic engagement with communities on local plans: The Bill includes measures to require locally prepared plans to be prepared to a swift two-year time frame whilst increasing the amount of community consultation undertaken within that process. It also sets a higher bar to depart from the plan in decision-making so as to give more certainty to communities about where development will and will not be. In next year’s wider review of the Framework, we will set out clear principles to be taken into account when preparing plans, where these are not already set out in the legislation, including the importance of effective community engagement in plan-making. In revising national policy, we will also want to restate and reinforce the importance of community engagement in decision-making, especially in light of the opportunities that improved use of digital technology can offer – including putting environmental evidence at the fingertips of communities and developers. In developing National Development Management Policies, we will seek to support faster plan-making without undermining community control.

5. Better environmental outcomes: Planning can make an important contribution to conserving and enhancing the natural environment, and the vitally important task of mitigating and adapting to climate change. We committed in the government’s Net Zero Strategy, published in October 2021, to review the National Planning Policy Framework to make sure it contributes to climate change mitigation and adaptation as fully as possible. In advance of next year’s wider review, which will consider the issue further, we are exploring how to do more through planning to measure and reduce emissions in the built environment. We also propose to do more to support environmental enhancement, nature recovery and climate change adaptation; to mitigate the effects of pollution; and to embed the important reforms introduced by the Environment Act.

6. Empowering communities to shape their neighbourhoods: The Bill will strengthen opportunities for people to influence planning decisions that affect their immediate area. We will give increased weight to neighbourhood plans to ensure the efforts of local communities to produce them bear fruit, introduce Neighbourhood Priorities Statements as a means for communities to formally input into the preparation of local plans, and allow residents to bring forward the development they want to see on their street through innovative new ‘street votes’. The wider review of the Framework next year will support this.

7. All this is needed to deliver more homes in the right places, supported by sustainable and integrated infrastructure for our communities and our economy. We need more homes to meet the needs of communities and allow more people to own their own home. Communities want beautiful new development, in a local plan shaped by the community, supported by appropriate new infrastructure, that enhances the environment, creating new neighbourhoods while respecting existing ones – if that is what communities demand, then a remade planning system that enables that will deliver more of the right homes in the right places year-on-year. The government remains committed to its manifesto commitment of 300,000 homes a year by the mid-2020s and is clear that every local planning authority having a local plan in place is the best way of achieving this. But planning for housing is not just about numbers; it is about getting the types and quality of homes that communities need in the right places and supported by the right infrastructure – and supporting our wider economic objectives like delivering levelling up, fuelling urban regeneration and redeveloping brownfield land. We will therefore also consider how national policy can be reframed to support smaller developers, self- and custom-build developers and other innovators to enter the market, building a competitive house building market with high standards, strong rules and clear accountability.

Chapter 3 – Providing certainty through local and neighbourhood plans

1. Every local authority should have a simple, clear local plan in place to plan for housing delivery in a sustainable way for years to come. However, only around 40% of local authorities have local plans adopted within the past 5 years and the government is determined to change this. Plans can protect the important landscapes communities cherish, direct homes to the places local people prefer, give confidence to investors and businesses that they can grow, and secure the sorts of homes and neighbourhoods communities want to see, supported by clear design codes.

2. We also need to make sure that once plans are in place, they are effective and deliverable. The Bill will make an important change, by increasing the weight given to adopted plans. Alongside this, here we set out changes that we propose would take effect from spring 2023 to the 5-year housing land supply rules in areas with up-to-date plans and where communities have made neighbourhood plans.

3. It is right that the presumption in favour of sustainable development set out in the National Planning Policy Framework remains an important part of the planning system, to ensure that development comes forward where up-to-date plans are not in place. Equally, where local authorities have up-to-date plans which are delivering as expected, they should not be forced to expend resources defending against speculative applications that run counter to the plans agreed in consultation with communities. Plans should deliver what they promise.

Reforming the 5 year housing land supply (5YHLS)

4. As previously announced, we are proposing to remove the requirement for local authorities with an up-to-date plan, (which in this case means where the housing requirement as set out in strategic policies is less than 5 years old[footnote 3]), to demonstrate continually a deliverable 5-year housing land supply. We propose the change to take effect when we publish the revised National Planning Policy Framework, expected in spring 2023. Our intention is to provide local authorities with another strong incentive to agree a local plan, giving communities more of a say on development and allowing more homes to be built. Alongside this, we intend to make further changes to simplify the operation of 5-year housing land supply requirements.

Q.1: Do you agree that local planning authorities should not have to continually demonstrate a deliverable 5-year housing land supply (5YHLS) for as long as the housing requirement set out in its strategic policies is less than 5 years old?

5. The Framework currently requires local authorities to include a buffer of 5%, 10% or 20% on top of their 5-year housing land supply in plan-making or when making decisions. These buffers were built into the 5-year housing land supply as contingency. Currently the 5% buffer is expected in all cases as a minimum, the 10% buffer is applied when an Annual Position Statement or recently adopted plan meets specific criteria (as set out in the Framework) and the 20% buffer is applied as a consequence of the Housing Delivery Test, where a local planning authority delivers less than 85% of the homes it is required to. However, the buffers can add a complexity which may not bring equivalent supply rewards. For plan-making, they can prolong debate, making it harder to get plans into place. For decision-making they can open additional routes to unplanned development. Therefore, to simplify the planning system, support a plan-led approach and to make housing land supply calculations more comprehensible to the public, we propose removing these 5-year housing land supply buffers from national planning policy in the future. Of course, it will remain vitally important that when making plans, local planning authorities identify a robust and deliverable 5-year housing land supply from the intended date of adoption of the plan.

Q.2: Do you agree that buffers should not be required as part of 5YHLS calculations (this includes the 20% buffer as applied by the Housing Delivery Test)?

6. We also recognise that current guidance on using any oversupply of housing in 5-year housing land supply calculations leaves room for different interpretations. We have a system that has the potential to penalise those local planning authorities that overdeliver their housing requirements early in the plan period. In particular, where a local planning authority cannot justify using historic oversupply in its 5-year housing land supply calculations, it can result in a shortfall in a 5-year housing land supply later in the plan period. Consequently, the presumption in favour of sustainable development can result in additional development on land which is not allocated for development in the local plan or in line with local policies.

7. We propose bringing our position on oversupply in line with that on undersupply, when calculating a 5-year housing land supply. This will enable a local planning authority to include historic oversupply in its 5-year housing land supply calculations and to demonstrate it is meeting its community’s overall housing requirements. This would be implemented by amending the Framework and planning practice guidance.

Q.3: Should an oversupply of homes early in a plan period be taken into consideration when calculating a 5YHLS later on, or is there an alternative approach that is preferable?

Q.4: What should any planning guidance dealing with oversupply and undersupply say?

Boosting the status of Neighbourhood Plans

8. Currently, where the most important policies for determining an application are out-of-date (including situations where a local planning authority cannot demonstrate it has a 5-year housing land supply, or housing delivery has been below 75% over the previous 3 years), the National Planning Policy Framework (under existing paragraph 11d) places an emphasis on granting permission. One exception is where any adverse impacts of doing so would significantly and demonstrably outweigh the benefits, when assessed against policies in the Framework. However, where a neighbourhood plan is in force, the decision-maker also needs to consider paragraph 14 of the existing Framework. It says that the adverse impact of allowing development that conflicts with the Neighbourhood Plan is likely to outweigh the benefits, but only if that plan meets the following conditions:

- the neighbourhood plan became part of the development plan 2 years or less before the date on which the decision is made;

- the neighbourhood plan contains policies and allocations to meet its identified housing requirement; and

- the local planning authority has at least a 3-year supply of deliverable housing sites (against its 5-year housing supply requirement) and housing delivery was at least 45% of that required over the previous 3 years.

9. Existing National Planning Policy Framework paragraph 14 gives strong protection from speculative development to areas with a neighbourhood plan less than 2 years old that meets its housing requirement. It does, however, mean that areas with older neighbourhood plans, or where the local planning authority has a low housing land supply or poor housing delivery, can be vulnerable to speculative development.

10. We expect that neighbourhood plans will be more protected in future, because this consultation proposes that where a local plan for the area is up-to-date, a 5-year housing land supply will not be required. This would mean that the presumption in favour of sustainable development would not apply as often.

11. Nevertheless, we are also proposing additional protections for neighbourhood plans in circumstances where a local planning authority’s policies for the area covered by the neighbourhood plan are out-of-date. First, we are proposing to extend protection to neighbourhood plans that are up to 5 years old instead of the current 2 years. Second, we are proposing removing tests which currently mean local planning authorities need to demonstrate a minimum housing land supply and have delivered a minimum amount in the Housing Delivery Test for Neighbourhood Plans to benefit from the protection afforded by the Framework.

Q.5: Do you have any views about the potential changes to paragraph 14 of the existing Framework and increasing the protection given to neighbourhood plans?

Chapter 4 – Planning for housing

1. Ensuring that enough land is allocated to provide the right homes in the right places that our communities need, alongside other economic, social and environmental needs, is a central task of planning. This chapter is seeking your views on potential changes to the Framework and planning practice guidance that will support our objective of a planning system that delivers the new homes we need while taking account of important areas, assets or local characteristics that should be protected or respected.

2. Sustainably planning for housing to reflect the importance of planning for housing, as well as the other forms of development that places need, we propose making small additions to paragraphs 1 and 7 of the existing Framework (the Introduction and Chapter 2 on Achieving Sustainable Development). These changes are intended to signal that providing for necessary development that is integrated with local infrastructure is a core purpose of the planning system, while not negating the fundamental importance of respecting the overarching economic, social and environmental objectives which set out in Chapter 2.

Q.6: Do you agree that the opening chapters of the Framework should be revised to be clearer about the importance of planning for the homes and other development our communities need?

Local housing need and the standard method

3. The standard method for assessing local housing need was introduced in 2018 to make sure that plan-making by local authorities is informed by an objective assessment of projected household growth and affordability pressures, while speeding up the process of establishing housing requirement figures through local plans. It remains important that we have a clear starting point for the plan-making process and we are not proposing any changes to the standard method formula itself through this consultation. However, we will review the implications on the standard method of new household projections data based on the 2021 Census, which is due to be published in 2024.

4. Our proposed changes respond to the concerns we have heard from a wide range of stakeholders. We have heard that:

- there can be confusion about how and when it is acceptable to bring forward a plan that does not meet housing needs in full due to recognised constraints such as Green Belt. As a result, some local authorities are not progressing plans, or are struggling to make their case at examination.

- some major urban centres are not meeting, or proposing to meet, their housing need in full, with the prospect of it being ‘exported’ to surrounding areas, contrary to the objective of delivering need in those areas with the best sustainable transport links and infrastructure, and with the greatest brownfield opportunities.

- delivering more homes than expected in the early years of a plan can create a “ratchet effect” as local authorities have to find more land for homes, even if overall they have delivered on expectations, thus disincentivising ambitious plans.

- some authorities are subject to consequences through the Housing Delivery Test due to developer behaviour when they are granting more than enough permissions.

- areas with recently made neighbourhood plans can find that those plans are overridden and open to unplanned development because the local planning authority cannot demonstrate a sufficient supply of housing, or their plans are set aside due to low performance in the Housing Delivery Test.

- there are concerns about the pace at which some sites, which have been granted planning permission, move through to construction and completion of new homes.

5. The combined effect is to inhibit plan-making, fuel opposition to development and ultimately hinder the supply of high-quality homes where they are needed. To address this, we propose making changes to the current National Planning Policy Framework and associated guidance on local housing need and the Housing Delivery Test. These changes are designed to support local authorities to set local housing requirements that respond to demographic and affordability pressures while being realistic given local constraints. Being clearer about how local constraints can be taken into account and taking a more proportionate approach to local plan examination is intended to speed up plan-making. Since we know that areas with up-to-date local plans have higher levels of housing delivery compared to authorities with an out-of-date local plan, or no plan at all , this is an important part of boosting housing supply. Our proposed changes to the operation of the Housing Delivery Test are similarly designed to support a plan-led system, by preventing local authorities who are granting sufficient permissions from being exposed to speculative development, which can undermine community trust in plan-making. We seek views on specific proposals now so that we can make a focused update to the National Planning Policy Framework and guidance, and quickly have an impact on plan-making and on speculative development in those areas granting enough permissions.

6. Our proposed changes for planning for housing are intended to support plan-making and in doing so help deliver more homes. We would be interested in your views on the overall implications these changes may have on plan-making and housing supply.

Q.7: What are your views on the implications these changes may have on plan-making and housing supply?

Introducing new flexibilities to meeting housing needs

7. We propose making the following changes to take effect from spring 2023:

8. Using an alternative method: local authorities will be expected to continue to use local housing need, assessed through the standard method, to inform the preparation of their plans; although the ability to use an alternative approach where there are exceptional circumstances that can be justified will be retained. We will, though, make clearer in the Framework that the outcome of the standard method is an advisory starting-point to inform plan-making – a guide that is not mandatory – and also propose to give more explicit indications in planning guidance of the types of local characteristics which may justify the use of an alternative method, such as islands with a high percentage of elderly residents, or university towns with an above-average proportion of students. We would welcome views on the sort of demographic and geographic factors which could be used to demonstrate these exceptional circumstances in practice.

Q.8: Do you agree that policy and guidance should be clearer on what may constitute an exceptional circumstance for the use of an alternative approach for assessing local housing needs? Are there other issues we should consider alongside those set out above?

9. Taking account of constraints and previous plans: we propose to make 3 changes relating to matters that may need to be considered when assessing whether a plan can meet all of the housing need which has been identified locally:

- First, we intend to make clear that if housing need can be met only by building at densities which would be significantly out-of-character with the existing area (taking into account the principles in local design guides or codes), this may be an adverse impact which could outweigh the benefits of meeting need in full (as set out in paragraph 11(b)(ii) of the existing Framework). This change recognises the importance of being able to plan for growth in a way which recognises places’ distinctive characters and delivers attractive environments which have local support; imperatives which are reflected in the Framework’s chapter on achieving well-designed places.

- Second, through a change to the Framework’s chapter on protecting Green Belt land, we propose to make clear that local planning authorities are not required to review and alter Green Belt boundaries if this would be the only way of meeting need in full (although authorities would still have the ability to review and alter Green Belt boundaries if they wish, if they can demonstrate that exceptional circumstances exist). This change would remove any ambiguity about whether authorities are expected to review the Green Belt, which is something which has caused confusion and often protracted debate during the preparation of some plans.

- Third, we are aware that in some cases authorities may feel that they are having to plan for more than they need to, having delivered more homes than were planned for during the preceding plan period. We therefore intend to make clear that authorities may also take past ‘over-delivery’ into account, such that if permissions that have been granted exceed the provision made in the existing plan, that surplus may be deducted from what needs to be provided in the new plan. This is separate to the proposals described earlier which would allow oversupply to be taken into consideration for the purposes of calculating a 5-year housing land supply.

Q.9: Do you agree that national policy should make clear that Green Belt does not need to be reviewed or altered when making plans, that building at densities significantly out-of-character with an existing area may be considered in assessing whether housing need can be met, and that past over-supply may be taken into account?

Q.10: Do you have views on what evidence local planning authorities should be expected to provide when making the case that need could only be met by building at densities significantly out-of-character with the existing area?

11. The purpose of these changes is to provide more certainty that authorities can propose a plan with a housing requirement that is below their local housing need figure, so long as proposals are evidenced, the plan makes appropriate and effective use of land, and where all other reasonable options to meet housing need have been considered. We will also make clearer in policy that authorities who wish to plan for more homes than the standard method (or an alternative approach) provides for may do so, where they judge that is right for their areas, for example to capitalise on economic development opportunities.

12. We also want to make sure that plans are subject to proportionate assessment when they are examined, in particular to avoid local planning authorities and other parties having to produce very large amounts of evidence to show that the approach taken to meeting housing need is a reasonable one. To do so, we propose to simplify and amend the tests of ‘soundness’ through which plans are examined, so that they are no longer required to be ‘justified’. Instead, the examination would assess whether the local planning authority’s proposed target meets need so far as possible, takes into account other policies in the Framework, and will be effective and deliverable. Although authorities would still need to produce evidence to inform and explain their plan, and to satisfy requirements for environmental assessment, removing the explicit test that plans are ‘justified’ is intended to allow a proportionate approach to their examination, in light of these other evidential requirements. We intend to update national policy in spring 2023 to reflect this.

13. For the purposes of the changes to the test of soundness, we propose that these will not apply to plans that have reached pre-submission consultation stage[footnote 4], plans that reach that stage within 3 months of the introduction of this policy change, or plans that have been submitted for independent examination.

Q.11: Do you agree with removing the explicit requirement for plans to be ‘justified’, on the basis of delivering a more proportionate approach to examination?

Q.12: Do you agree with our proposal to not apply revised tests of soundness to plans at more advanced stages of preparation? If no, which if any, plans should the revised tests apply to?

14. Delivering the urban uplift: Whilst important constraints need to be recognised when planning for homes, so too do the opportunities to locate more homes in sustainable urban locations where development can help to reduce the need to travel (thereby supporting sustainable patterns of development overall) and contribute to productivity, regeneration and levelling up. The uplift supports our approach to making the best use of brownfield land. The method for calculating local housing need was amended in 2020 to apply an uplift of 35% for the 20 largest towns and cities, in recognition of this potential. The government intends to maintain this uplift and to require that this is, so far as possible, met by the towns and cities concerned rather than exported to surrounding areas, except where there is voluntary cross-boundary agreement to do so (for example through a joint local plan or spatial development strategy). It will be important to capitalise on opportunities to further densify in these already-developed urban areas, using local design codes to do so in ways that take account of the existing environment. We propose a change to the Framework (see associated draft revised Framework published alongside this document for details) to make clear in policy how the uplift should be applied.

15. The Bill will remove the Duty to Co-operate, although it will remain in place until those provisions come into effect. To secure appropriate engagement between authorities where strategic planning considerations cut across boundaries, we propose to introduce an “alignment policy” as part of a future revised Framework. Further consultation on what should constitute the alignment policy will be undertaken. We are, however, aware that the boundaries of some towns and cities mean that there is sometimes minimal distinction between areas that are part of one of the 20 urban uplift authorities and neighbouring authorities. In some cases, there is good co-operation between such authorities, but we would like to hear views on how such adjoining authorities should consider their role in meeting the needs of the “core” town or city.

Q.13: Do you agree that we should make a change to the Framework on the application of the urban uplift?

Q.14: What, if any, additional policy or guidance could the department provide which could help support authorities plan for more homes in urban areas where the uplift applies?

Q.15: How, if at all, should neighbouring authorities consider the urban uplift applying, where part of those neighbouring authorities also functions as part of the wider economic, transport or housing market for the core town/city?

16. The government does not propose changes to the standard method formula or the data inputs to it through this consultation. However, the government has heard representations that the 2014-based household projections data underpinning the standard method should no longer be relied on. The government continues to use these data to provide stability, consistency and certainty to local planning authorities. Once we have considered the implications of new 2021 Census based household projections, planned to be published by the Office for National Statistics in 2024, the government will review the approach to assessing housing need, to make sure the method commands long-term support based on the most relevant data.

Enabling communities with plans already in the system to benefit from changes

17. Authorities can begin planning in line with these changes, should they be implemented following public consultation, in spring 2023. We recognise that any changes to emerging plans which are necessary may result in delays in getting an up-to-date plan in place. So, to reduce the risk of communities being exposed to speculative development, we propose the following time-limited arrangements. For the purposes of decision-making, where emerging local plans have been submitted for examination or where they have been subject to a Regulation 18 or 19 consultation[footnote 5] which included both a policies map and proposed allocations towards meeting housing need, those authorities will benefit from a reduced housing land supply requirement. This will be a requirement to demonstrate a 4-year supply of land for housing, instead of the usual 5. These arrangements would apply for a period of 2 years from the point that these changes to the Framework take effect, since our objective to provide time for review while incentivising plan adoption.

18. We are also proposing a number of transitional arrangements with respect to moving to the new plan-making system, as set out in Chapter 9 of this document.

Q.16: Do you agree with the proposed 4-year rolling land supply requirement for emerging plans, where work is needed to revise the plan to take account of revised national policy on addressing constraints and reflecting any past over-supply? If no, what approach should be taken, if any?

Q.17: Do you consider that the additional guidance on constraints should apply to plans continuing to be prepared under the transitional arrangements set out in the existing Framework paragraph 220?

Taking account of permissions granted in the Housing Delivery Test (HDT)

19. The Housing Delivery Test was introduced in 2018 to measure homes built in local planning authorities across England. Where delivery is below the number of homes planned for, policy consequences are applied to help identify the reasons for under-delivery and to make sure sufficient land is brought forward for development (an action plan for those delivering below 95%, a 20% buffer added to 5-year housing land supply for those delivering below 85%, and the presumption in favour of sustainable development for those delivering below 75%).

20. The government wants to apply the HDT in a way which does not penalise local planning authorities unfairly when slow housing delivery results from developer behaviour. With this in mind, we are proposing adding to the current Housing Delivery Test an additional permissions-based test. This will ‘switch off’ the application of ‘the presumption’ as a consequence of under-delivery, where a local planning authority can demonstrate that there are ‘sufficient’ deliverable permissions to meet the housing requirement set out in its local plan. This is in addition to the proposal to delete the 20% HDT buffer consequence in the above section on the 5-year housing land supply.

21. To qualify for the Housing Delivery Test presumption ‘switch off’, a local planning authority would need to have sufficient permissions for enough deliverable homes to meet their own annual housing requirement or, where lacking an up-to-date plan (adopted in the past 5 years), local housing need, plus an additional contingency based on the number of planning permissions that are not likely to be progressed or are revised.

22. The figures currently collected by the department are the numbers of decisions on planning applications submitted to local planning authorities, rather than the number of homes included in each application, so we will need a robust approach for counting permissioned homes. Our assessment is that some contingency will be required: based on an analysis of the number of planning permissions that are not progressed or are revised, this should be set at 15%. We therefore propose defining ‘sufficient’ deliverable units as 115% of the housing requirement or local housing need, and this will form the basis for the ‘switch off’. If a local planning authority can show they have permissioned enough housing, the application of the presumption will be ‘switched off.’ However, the authority will still be required to prepare an action plan that assesses the causes of housing under-delivery and identifies actions to increase housing delivery in future years.

Q.18: Do you support adding an additional permissions-based test that will ‘switch off’ the application of the presumption in favour of sustainable development where an authority can demonstrate sufficient permissions to meet its housing requirement?

Q.19: Do you consider that the 115% ‘switch-off’ figure (required to turn off the presumption in favour of sustainable development Housing Delivery Test consequence) is appropriate?

Q.20: Do you have views on a robust method for counting deliverable homes permissioned for these purposes?

23. It remains our intention to publish the 2022 Housing Delivery Test results. However, given our proposed changes and consultation on the workings of the Housing Delivery Test, we would like to receive views on whether the test’s consequences should follow from the publication of the 2022 Test or if they should be amended, suspended until the publication of the 2023 Housing Delivery Test, or frozen to reflect the 2021 Housing Delivery Test results while work continues on our proposals to improve it. We will take a decision on the approach to the Housing Delivery Test and the implementation of any the proposed changes in due course, once we have analysed consultation responses.

Q. 21: What are your views on the right approach to applying Housing Delivery Test consequences pending the 2022 results?

Chapter 5 – A planning system for communities

1. The government is committed to creating a planning system that focuses not simply on housing numbers, but on delivering the types of homes that communities want and need. That means a diverse range of homes, more genuinely affordable housing and specific provision for older people – all built to designs that suit local communities and at densities that make efficient use of land while aligning with local character. Below we consult on some specific changes to take effect from spring 2023 and seek views on a set of wider proposals.

More homes for social rent

2. The Levelling Up White Paper made clear our commitment to “increase the amount of social housing available over time to provide the most affordable housing to those who need it” and to “ensure home ownership is within the reach of many more people”. If we want to have functioning communities, with the right homes in the right places, then we need to deliver more homes that are genuinely affordable to rent and to own.

3. The Framework currently includes specific stipulations about securing homes for affordable home ownership, outlining an expectation that 10% of homes in major developments should be available for affordable home ownership. We believe our national planning policy must continue to support this but equally that it should place much greater value on the most affordable housing tenure: Social Rent.[footnote 6]

4. We therefore intend to make changes to the Framework to make clear that local planning authorities should give greater importance in planning for Social Rent homes, when addressing their overall housing requirements in their development plan and making planning decisions. Securing Social Rent homes will already be the priority for many local planning authorities, and we want national planning policy to support this. We would welcome views on how we could make specific provisions in the revised framework to deliver this, alongside the existing provisions for affordable home ownership.

Q.22: Do you agree that the government should revise national planning policy to attach more weight to Social Rent in planning policies and decisions? If yes, do you have any specific suggestions on the best mechanisms for doing this?

More older people’s housing

5. This government is committed to further improving the diversity of housing options available to older people and boosting the supply of specialist elderly accommodation. The National Planning Policy Framework supports this ambition by asking local authorities to provide for a diverse range of housing needs, including for older people.

6. The Framework already makes clear that the size, type and tenure of housing needed for different groups in the community, including older people, should be assessed and reflected in planning policies. In 2019, we also published guidance to help local authorities implement the policies that can deliver on this expectation.

7. The population of the UK is ageing rapidly and around 1-in-4 will be aged 65 or over by 2041. We need to ensure that our housing market is prepared for this challenge and that older people are offered a better choice of accommodation to suit their changing needs, to help them to live independently and feel more connected to their communities. In 2021, a report by the International Longevity Centre indicates that there will be a shortfall of 37% in specialist retirement housing by 2040.

8. We have therefore been considering ways in which the Framework can further support the supply of older people’s housing. We propose to do this by adding an additional specific expectation that within ensuring that the needs of older people are met, particular regard is given to retirement housing, housing-with-care and care homes, which are important typologies of housing that can help support our ageing population.

9. Alongside this, we are also launching a taskforce on older people’s housing, which we announced in the Levelling Up White Paper. This taskforce will explore how we can improve the choice of and access to housing options for older people and will follow important work conducted recently by Professor Mayhew on meeting the challenges of our ageing population.

Q.23: Do you agree that we should amend existing paragraph 62 of the Framework to support the supply of specialist older people’s housing?

More small sites for small builders

10. Small sites play an important role in delivering gentle density in urban areas, creating much needed affordable housing, and supporting small and medium size (SME) builders. Paragraph 69 of the existing National Planning Policy Framework sets out that local planning authorities should identify land to accommodate at least 10% of their housing requirement on sites no larger than one hectare; unless it can be shown, through the preparation of relevant plan policies, that there are strong reasons why this 10% target cannot be achieved. The Framework also asks local planning authorities to use tools such as area-wide design assessments and Local Development Orders to help bring small and medium sized sites forward; and to support the development of windfall sites through their policies and decisions. Local planning authorities are asked to work with developers to encourage the sub-division of large sites where this could help to speed up the delivery of homes.

11. We have heard views that these existing policies are not effective enough in supporting the government’s housing objectives, and that they should be strengthened to support development on small sites, especially those that will deliver high levels of affordable housing. The government is therefore inviting comments on whether paragraph 69 of the existing Framework could be strengthened to encourage greater use of small sites, particularly in urban areas, to speed up the delivery of housing (including affordable housing), give greater confidence and certainty to SME builders and diversify the house building market. We are seeking initial views, ahead of consultation as part of a fuller review of national planning policy next year. Alongside this, the government has developed a package of existing support available for SME builders, including the Levelling Up Home Building Fund which provides development finance and Homes England’s Dynamic Purchasing System which disposes of parcels of land.

Q.24 Do you have views on the effectiveness of the existing small sites policy in the National Planning Policy Framework (set out in paragraph 69 of the existing Framework)?

Q.25 How, if at all, do you think the policy could be strengthened to encourage greater use of small sites, especially those that will deliver high levels of affordable housing?

More community-led developments

12. To support levelling up and housing market diversification and delivery, we want to encourage a greater role for community-led housing groups. We propose to strengthen statements within Chapter 5 of the Framework to make sure there is more emphasis on the role that community-led development can have in supporting the provision of more locally-led affordable homes.

13. We want to encourage local planning authorities to support the role of community-led groups in delivering affordable housing - including on exception sites - by referencing community-led developments specifically. We are also proposing to define community-led developments in the Glossary of the framework to assist in the implementation of this policy change.

14. We want national planning policy to recognise the important contribution that community-led groups can make to the development of new affordable homes, and the associated benefits in terms of design quality, and sustaining local communities and local economies. Some community-led developers have told us that the definition of “affordable housing for rent” in the Framework glossary makes this more difficult because it defines this type of housing as having a landlord that is a Registered Provider of social housing (other than where part of Build to Rent schemes).

15. Restricting the definition to homes let by Registered Providers ensures that the residents who will eventually live in those homes benefit from the protections offered by the regulatory system for social housing. We are currently in the process of enhancing those protections through the Social Housing Regulation Bill.

16. Whilst community-led developers may apply to become Registered Providers, many prefer not to do so on grounds of proportionality. Almshouses – who also make a valuable contribution to the provision of affordable housing – have raised similar concerns about the definition.

17. We would therefore welcome views on whether the definition of “affordable housing for rent” should be amended to make it easier for organisations that are not Registered Providers – in particular, community-led developers and almshouses – to develop new affordable homes. We would also welcome views on how we can ensure that any change aligns with our drive (including through the Social Housing Regulation Bill) to ensure that social housing is of good quality and that residents can have access to swift and fair redress. In addition, we would like to make it easier for community groups to bring forward exception sites for affordable housing in rural areas, as they are often particularly well placed to understand community needs and aspirations. We are not aware of any major barriers for community groups in making use of the existing rural exception sites policy but would be keen to seek the views of stakeholders as to whether this is in fact the case, and if there are any broader changes that government could make to encourage community involvement in affordable housing delivery, particularly in rural areas.

Q.26: Should the definition of “affordable housing for rent” in the Framework glossary be amended to make it easier for organisations that are not Registered Providers – in particular, community-led developers and almshouses – to develop new affordable homes?

Q.27: Are there any changes that could be made to exception site policy that would make it easier for community groups to bring forward affordable housing?

Q.28: Is there anything else that you think would help community groups in delivering affordable housing on exception sites?

Q.29: Is there anything else national planning policy could do to support community-led developments?

18. Separately from these immediate changes to the NPPF, we want to take the opportunity to consult on potential ways to improve developer accountability and, in particular, take account of past irresponsible behaviour in decision-making.

19. Public confidence in the planning system is undermined if planning rules are deliberately ignored and there is no sanction against such behaviour. Although the vast majority of developers and landowners follow the rules, instances of irresponsible individuals and companies persistently breaching planning controls or failing to deliver their legal commitments to the community are not uncommon. It is particularly frustrating when local communities see these individuals and companies securing planning permission again despite their blatant disregard for the rules.

20. The Bill already includes a package of planning enforcement reforms to enable local planning authorities to take more effective enforcement action against unauthorised development, but the government wants to go further. We are keen to explore whether past irresponsible planning behaviour should be taken into account when applying for planning permission. This would ensure bad developers cannot continue to play the planning system, helping to strengthen local communities’ trust in it.

21. We recognise that it is a long-standing principle that planning decisions should be based on the planning merits of the proposed development – and not the applicant. This principle is critical to ensuring the planning system is fair, open and focused on land use considerations. Nonetheless, there are instances where personal circumstances can be taken into account, and we consider it would be legitimate to consider widening this scope to include an applicant’s past irresponsible behaviour.

22. We consider there are at least two potential ways of take account of this past irresponsible behaviour:

- option 1: making such behaviour a material consideration when local planning authorities determine planning applications so that any previous irresponsible behaviour can be taken into account alongside other planning considerations;

- option 2: allowing local planning authorities to decline to determine applications submitted by applicants who have a demonstrated track record of past irresponsible behaviour prior to the application being considered on its planning merits - similar to the amendment which we have already made to the Levelling Up and Regeneration Bill allowing local planning authorities to decline to determine new applications on sites where the build out of development has been too slow.

These options will require primary legislation, as well as further engagement with local planning authorities, the development sector and other stakeholders to ensure that the proposals are fair, proportionate and workable.

Q.30: Do you agree in principle that an applicant’s past behaviour should be taken into account into decision making? If yes, what past behaviour should be in scope?

Q.31: Of the 2 options above, what would be the most effective mechanism? Are there any alternative mechanisms?

More build out

23. The government is absolutely clear that developments should be built out as soon as possible once planning permission is granted. However, we recognise that there are concerns about the pace at which some sites, which have received the grant of planning permission, are progressing. We have therefore developed a package of measures to incentivise the prompt build-out of permitted housing sites and to support local authorities to act against those who fail to meet these commitments.

24. Through proposals in the Bill, housebuilders will be required to formally notify local authorities, via a Development Commencement Notice (DCN), when they commence development. We will also modernise and streamline existing powers for local authorities to serve a completion notice (which has the effect that if the development is not completed within the period specified in the notice, the planning permission for unfinished development lapses), making the process much quicker and simpler. Furthermore, housing developers will be required to report annually to local authorities on their actual delivery of housing against a proposed trajectory that they submit on commencing a scheme for which they have permission. Finally, local planning authorities will have discretion to decide whether to entertain future planning applications made by developers who fail to build out earlier permissions granted on the same land. Of course, alongside this we expect local authorities to do their bit in promptly processing planning permissions and discharging conditions and an increase in planning fees that we intend to consult on is intended to help resource local authorities to do this.

25. To further strengthen this package, following passage of the Bill, we intend to introduce 3 further measures, via changes to national planning policy:

a) We will publish data on developers of sites over a certain size in cases where they fail to build out according to their commitments.

b) Developers will be required to explain how they propose to increase the diversity of housing tenures to maximise a development scheme’s absorption rate (which is the rate at which homes are sold or occupied).

c) The National Planning Policy Framework will highlight that delivery can be a material consideration in planning applications. This could mean that applications with trajectories that propose a slow delivery rate may be refused in certain circumstances.

26. These measures will improve transparency and public accountability over build out rates once permission is granted, empower local authorities to take account of build out considerations when making planning decisions, and give authorities stronger tools to address build out problems where they arise. We are seeking initial views, ahead of consultation as part of a fuller review of national planning policy next year.

27. We will be launching a separate consultation on proposals to introduce a financial penalty against developers who are building out too slowly.

Q.32 Do you agree that the 3 build out policy measures that we propose to introduce through policy will help incentivise developers to build out more quickly? Do you have any comments on the design of these policy measures?

Chapter 6 – Asking for beauty

Ask for beauty

1. As the Building Better, Building Beautiful Commission made clear, beauty is not a cost to be negotiated away once planning permission has been obtained. It is the benchmark that all new developments should meet. It includes everything that promotes a healthy and happy life, everything that makes a collection of buildings into a place, everything that turns anywhere into somewhere, and nowhere into home.

2. Through our work on levelling up we make clear the importance of well-designed beautiful places to boosting civic pride, with people having a say on how and where beautiful sustainable homes and neighbourhoods are built. As set out in Chapter 2, better design supports housing supply because we know that communities are more welcoming of new development that is beautiful.

3. Design codes prepared by local authorities with communities will ensure beautiful and well-designed development by helping to shape buildings, public spaces, streets and neighbourhoods. These will set simple clear minimum standards on development in that area – such as height, form and density. We intend to consult on introducing secondary legislation so that existing permitted development rights with design or external appearance prior approvals will take into account design codes where they are in place locally.

4. The National Planning Policy Framework was updated in July 2021 to strengthen the emphasis on beauty, place-making and good design. We have updated the reference in existing paragraph 135 on the use of design assessment tools and processes by local planning authorities. This reflects that the National Model Design Code (NMDC) is now in widespread use and that the primary means of assessing and improving the design of development should be through the preparation of local design codes in line with the NMDC, which will provide a framework for creating healthy, safe, green, environmentally responsive, sustainable and distinctive places, with a consistent and high-quality standard of design.

5. We propose to make the changes to the Framework to emphasise the role of beauty and placemaking in strategic policies to further encourage beautiful development and deliver on the levelling up missions through our national planning policy. We also propose to make a stronger link between good design and beauty by making additions to Chapters 6, 8 and 12 of the Framework to further reflect the importance of beautiful development in our everyday lives as recognised by the Building Better, Building Beautiful Commission report so it becomes a natural result of working within the planning system.

Q.33: Do you agree with making changes to emphasise the role of beauty and placemaking in strategic policies and to further encourage well-designed and beautiful development?

6. We also propose to replace the references to ‘well-designed’ in the title of Chapter 12 and existing paragraphs 84a and 124c to read ‘well-designed and beautiful’.

Q.34: Do you agree to the proposed changes to the title of Chapter 12, existing paragraphs 84a and 124c to include the word ‘beautiful’ when referring to ‘well-designed places’ to further encourage well-designed and beautiful development?

Refuse ugliness

7. It is important that local planning authorities have visual clarity on the design of development as part of the planning application process by ensuring conditions refer to clear and accurate plans and drawings. This will help support effective enforcement and ensure well-designed and beautiful places where the design quality of approved development is not materially diminished after a scheme is permitted. We propose to amend the Framework to encourage local planning authorities to consider how they can ensure that planning conditions associated with applications reference clear and accurate plans and drawings which provide visual clarity about the design of development, as well as clear conditions about the use of materials where appropriate, so they can be referred to as part of the enforcement process.

Q.35: Do you agree greater visual clarity on design requirements set out in planning conditions should be encouraged to support effective enforcement action?

Embracing gentle density

8. Building upwards in managed ways can help deliver new homes and extend existing ones in forms that are consistent with the existing street design, contributing to gentle increases in density. The Framework sets out how local planning policies and decisions should consider airspace development above existing residential and commercial premises for new homes. This includes allowing upwards extensions where the development would be consistent with criteria relating to neighbouring properties and the overall street scene, as well as being well-designed and maintaining safe access and egress for occupiers.

9. In some locations, local planning authorities have been reluctant to approve mansard roof development, as it has been considered harmful to the character of neighbourhoods[footnote 7]. As a general approach, this is wrong - all local planning authorities should take a positive approach towards well designed upward extension schemes, particularly mansard roofs. It is proposed that a reference to mansard roofs as an appropriate form of upward extension would recognise their value in securing gentle densification where appropriate.

Q.36 Do you agree that a specific reference to mansard roofs in relation to upward extensions in Chapter 11, paragraph 122e of the existing Framework is helpful in encouraging LPAs to consider these as a means of increasing densification/creation of new homes? If no, how else might we achieve this objective?

Chapter 7 – Protecting the environment and tackling climate change

1. Leaving the environment in a better state and tackling climate change are two of the greatest long-term challenges facing the world today. The government is committed to ensuring that the town and country planning and Nationally Significant Infrastructure Project regimes contribute to addressing both of these challenges. The planning system should, as a whole, reflect the government’s ambition to help business and communities protect and enhance the environment for future generations, build a net zero carbon future, and adapt to the impacts of climate change. National planning policies and guidance, spatial development strategies and local plans should all contribute to this core objective of planning.

2. The National Planning Policy Framework already places environmental objectives at the heart of the planning system, making clear that planning should protect and enhance our natural environment, mitigate and adapt to climate change, support the transition to a low carbon future and take full account of flood risk and coastal change. The Environment Act has further strengthened the role of the planning system, through mandatory Biodiversity Net Gain and Local Nature Recovery Strategies, setting the foundations for planning to have a more proactive role in promoting nature’s recovery. Government is setting targets under the Environment Act, which will also drive action across government including through the proposed changes to the planning system to deliver environmental improvement. The changes we have committed to are designed to support more holistic placemaking – through application of the National Design Guide, National Model Design Code and local design codes – will also contribute to these objectives.

3. The government wants to build on these existing protections to make sure that protecting and improving the environment and tackling climate change are central considerations in planning. In principle, planning policies and decisions can support this in 6 main ways:

- protecting important natural, landscape and heritage assets, whilst also incorporating nature, landscape and public space into development and its surroundings;

- supporting habitat creation and nature recovery in ways which benefit nature and people. For instance, nature based solutions can store carbon, assist adaptation (e.g. by reducing water run-off rates) and protect and enhance ecology;

- promoting locational and design decisions that reduce exposure to pollution and hazards and respond to changing climate conditions, for example the risk of overheating, surface-water flooding, and water scarcity;

- enabling renewable and low carbon energy production and distribution, at both a commercial and household scale; and policies for regulating carbon-generating extraction and energy generation;

- promoting development locations, and designs and layouts, that contribute to healthier lifestyles, energy and resource efficiency consumption, for example by reducing the need to travel, increasing public transport connectivity and accessibility and promoting active travel i.e. walking, wheeling and cycling; and

- bringing together the spatial strategy for a place in a way which addresses these in a holistic way and reflects its unique characteristics, whilst also providing a clear framework for development and regeneration.

4. We recognise that some local authorities have already made significant progress in the areas above. We want to ensure these frontrunners continue to innovate and lead the way. And we want to support wider adoption of their best practice. We will review the strategic objectives set out in planning policy to ensure that they support this, along with government’s commitments on environmental targets under the Environment Act, net zero and the National Adaptation Programme. Ahead of the wider review of national planning policy next year, we are seeking views on the approach to carbon assessments and the role planning can play in supporting climate adaptation. In the short-term, we are consulting on specific changes to make sure that the food production value of land is reflected in planning decisions that we propose will take effect from spring 2023.

Delivering biodiversity net gain and local nature recovery

5. Whilst conserving and enhancing the environment has always been a central objective of the planning system, the growing scale of the environmental challenges which we face make the role of planning more important than ever. In particular, we believe the planning system can play a do more to enable nature and environmental improvements. The world-leading Environment Act 2021 provides the foundations for this, giving planning a crucial role in delivering its ambitious environmental programme, designed to halt the decline of species by 2030, clean up our air and protect the health of our rivers, reform the way in which we deal with waste and tackle deforestation overseas. In particular:

- it introduced a requirement to demonstrate at least 10% biodiversity net gain on all development sites, other than a small number of exemptions. This will become mandatory from November 2023 and will be a core component of our commitment to ensuring planning enables better outcomes for nature.

- it introduced new Local Nature Recovery Strategies, which will map important habitats and areas for nature recovery and enhancement. It is important that we reflect these strategies in the plan-making process if we are to capitalise on opportunities to strategically site off-site biodiversity net gain, public access to nature, nutrient mitigation and carbon sequestration; and

- during passage of the Act, the government made a commitment to review the National Planning Policy Framework policy on ancient woodlands and ancient and veteran trees, to consult on the wording in the Framework, and to introduce a new duty on planning authorities to consult the Secretary of State for DLUHC before granting permission for development affecting ancient woodland.

6. Making sure that Biodiversity Net Gain delivers: We have heard concerns about the risk of gaming the system by developers or landowners, clearing sites before applying for planning permission in order to lower the baseline from which gain is assessed. We will work with Defra to review the current degradation provisions for Biodiversity Net Gain, to reduce the risk of habitat clearances prior to the submission of planning applications, and before the creation of off-site biodiversity enhancements.

7. Embracing wider opportunities to support biodiversity: We are also seeking views on how we can strengthen policy and associated national design guidance to promote small-scale changes that can enhance biodiversity and support wildlife recovery. The National Model Design Code already promotes design that will encourage more wildlife-friendly neighbourhoods, including bat and bird boxes, bee and swift bricks and hedgehog highways. In addition, the government has already set out its view that artificial grass has no value for wildlife. Its installation can have negative impacts on both biodiversity drainage for flood prevention or alleviation, and plastic pollution, if installed in place of natural earth or more positive measures such as planting flowers, trees or providing natural water features. We want to go further and will consider how we can make sure that our policy and design guidance fully supports habitats and routes for wildlife, as well as halting the threat to wildlife created by the use of artificial grass by developers in new development (noting the importance of some uses of artificial grass such as on sports pitches).

Q.37 How do you think national policy on small scale nature interventions could be strengthened? For example in relation to the use of artificial grass by developers in new development?

8. Reflecting Local Nature Recovery Strategies in the planning system: The Environment Act has already established that local authorities have a responsibility, including through their planning functions, to have regard to the contents of these strategies. We have committed to bring forward further guidance on how local authorities will be expected to comply with this duty. This will set out how plan and decision making in the planning system can play a complementary role to the objectives of the strategies that are bought forward.

9. Ancient woodlands protection: Working with Defra, we will undertake the promised review of ancient woodlands and ancient and veteran trees protection in the Framework. As it is prescribed in the current system, development can only adversely impact ancient woodland and ancient and veteran trees if there are “wholly exceptional reasons, and a suitable compensation strategy exists”. As part of this review, we will consider the options for further protecting these important habitats through the planning system.

Recognising the food production value of farmland