Police powers and procedures: Other PACE powers, England and Wales, year ending 31 March 2022

Published 17 November 2022

Applies to England and Wales

Frequency of release: Annual

Forthcoming releases: Home Office statistics release calendar

Home Office responsible statistician: Jodie Hargreaves

Press enquiries: pressoffice@homeoffice.gov.uk

Telephone: 0300 123 3535

Public enquiries: policingstatistics@homeoffice.gov.uk

Privacy information notice: Home Office Crime and Policing Research and Annual Data Requirement (ADR) data - Privacy Information Notices

1. Introduction

1.1 Changes to the Police Powers and Procedures statistics release

In 2021 the Home Office made the decision to split the annual ‘Police powers and procedures’ statistical bulletin into two separate releases given the volume and variety of topics covered.

The first release, Police powers and procedures: Stop and search and arrests, England and Wales, year ending 31 March 2022, which was published on 27 October 2022, contains statistics on the use of the powers of stop and search and arrest by the police in England and Wales up to the year ending 31 March 2022.

This release is the second of the two publications on police powers and contains statistics on detentions under the Mental Health Act 1983, detentions and intimate searches under the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984, detentions in police custody (new), strip searches (new), and the use of pre-charge bail and released under investigation by the police in England and Wales up to the year ending 31 March 2022. Data on breath tests and fixed penalty notices (and other outcomes) for motoring offences, for the year ending 31 December 2021, are also included in this release.

1.2 Contents of this release

For the first time in the year ending March 2022, the Home Office has collected data on people who have been detained in police custody. Information on strip searches that have taken place in custody has also been collected for the first time and is presented in Chapter 2 of this bulletin.

The section on police custody contains data provided by a subset of the 43 police forces in England and Wales (see Chapter 2 for more detail), on a financial-year basis. These have been designated as Experimental Statistics. It includes statistics on the:

-

number of detentions in police custody

-

age-group, sex, and ethnicity of persons detained and all offences linked to the custody record (including notifiable and non-notifiable offences)

-

whether a child was detained in custody overnight

-

whether an appropriate adult was called (where applicable)

-

whether a detained adult was declared vulnerable

-

number of strip searches carried out

-

age, sex, and ethnicity of persons strip searched

-

number of persons detained by police in England and Wales under part IV of Police and Criminal Evidence (PACE) Act for more than 24 hours and subsequently released without charge

-

number of intimate searches made under section 55 of PACE

The section on detentions under section 136 of the Mental Health Act 1983 contains data provided by the 42 police forces in England and Wales, and British Transport Police, on a financial-year basis. It includes statistics on the:

-

number of detentions under section 136 of the Mental Health Act 1983

-

age-group, sex and ethnicity of persons detained

-

type of place of safety used to detain individuals, and the reason for using a police station (where applicable)

-

method of transportation used to transport an individual to a place of safety, and the reason for using a police vehicle (where applicable)

The breath tests section contains data from 40 police forces in England and Wales on a calendar-year basis. It includes statistics on the number of alcohol screening breath tests carried out by police and tests that were positive or refused.

The Fixed Penalty Notices (FPNs) and other outcomes for motoring offences section contains data from the national fixed penalty processing system (PentiP) for 43 police forces in England and Wales, on a calendar-year basis. It includes statistics on the number of:

-

endorsable and non-endorsable FPNs issued for a range of motoring offences

-

FPNs issued as a result of camera-detected offences

-

cases where the penalty was paid

-

motoring offences that resulted in a driver retraining course, or court action

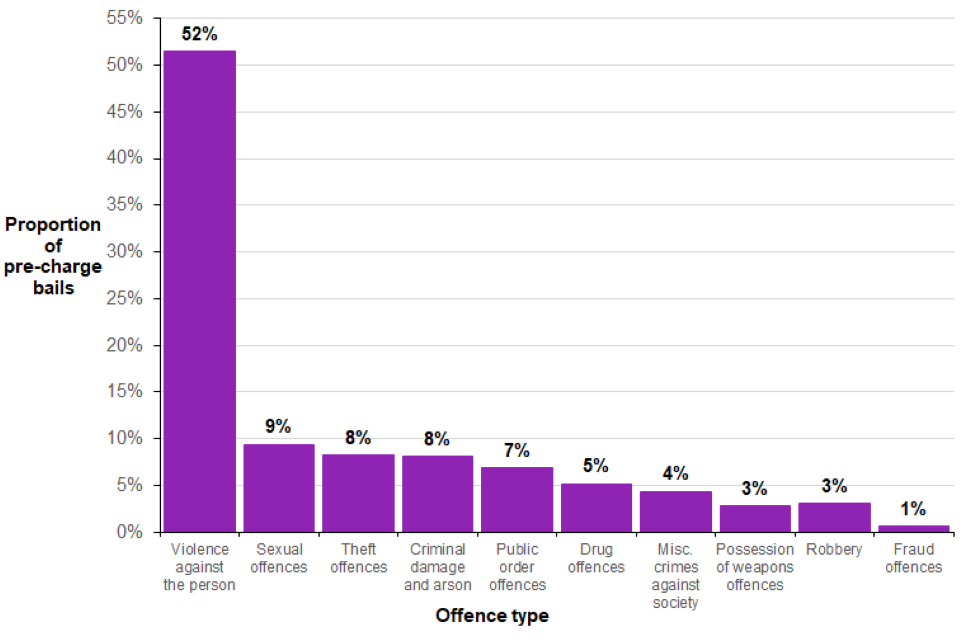

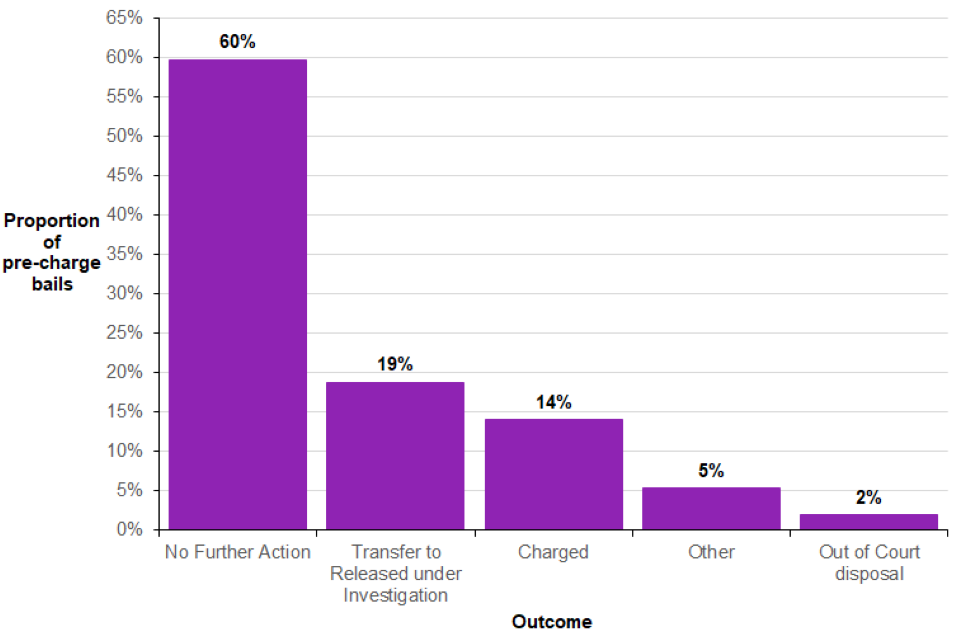

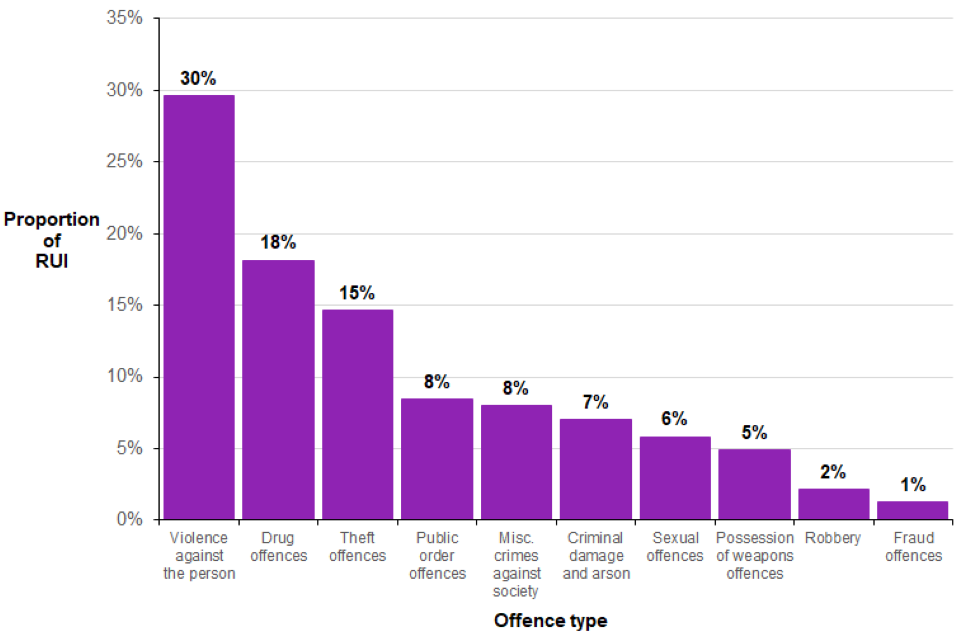

The pre-charge bail and released under investigation section contains data provided from a subset of the 43 police forces (see Chapter 6 for more detail) in England and Wales on a financial-year basis. These have been designated as Experimental Statistics. It includes statistics on:

-

number of persons released on pre-charge bail, released under investigation, who voluntary attended interview and number of persons who breached pre-charge bail conditions

-

age, sex, and ethnicity of persons released on pre-charge bail, released under investigation, voluntarily attended interview, or breached pre-charge bail conditions

-

duration of release under pre-charge bail or release under investigation

-

duration between first voluntary attendance to interview and outcome of the investigation

-

all offences linked to pre-charge bail, release under investigation, voluntarily attendance to interview or breach of pre-charge bail records

-

outcome of pre-charge bail, release under investigation, and voluntary attendance to interview

The detentions under section 135 of the Mental Health Act 1983 section contains data provided from the 38 police forces in England and Wales on a financial-year basis. These have been designated as Experimental Statistics. It includes statistics on:

-

number of detentions under section 135 of the Mental Health Act 1983

-

age-group, sex and ethnicity of persons detained

1.3 National Statistics status

These statistics have been assessed by the UK Statistics Authority to ensure that they continue to meet the standards required to be designated as National Statistics. This means that these statistics meet the highest standards of trustworthiness, impartiality, quality and public value, and are fully compliant with the Code of Practice for Statistics.

The Home Office worked closely with the UK Statistics Authority to improve information on the quality and limitations of the various datasets, and the ways in which the Home Office engages with users of the statistics. This is documented in the user guide, which is published alongside this release.

Given the partial nature of the data and inconsistencies across forces, statistics on detentions under section 135 of the Mental Health Act, pre-charge bail and released under investigation, and police custody and strip searches are designated as Experimental Statistics. These statistics do not yet meet the overall quality standards necessary to be designated as National Statistics. The Home Office intends to improve the completeness and quality of these data in future years.

2. Experimental statistics - police custody

2.1 Key findings

In the year ending March 2022 (based on a subset of forces and excluding unknowns):

- there were a total of 546,170 people detained in custody, of whom 35,114 were children (aged under 18)

- a third (33%) of offences for which people were in custody, were violence against the person offences

- around three-quarters (76%) of people in custody were of a white ethnic background, excluding the Metropolitan Police Service this rose to 86%

- people falling within the 21-30 and 31-40 age brackets made up the largest proportions of people in custody (30% and 29% respectively)

- an Appropriate Adult was called for the vast majority of children in custody (99%), for adults that were deemed vulnerable the proportion was much lower (41%)

- just under half (45%) of children taken into custody were detained overnight

- 65,336 people were strip searched in custody, the equivalent of 12% of all people in custody

- there were 19 intimate searches carried out by police in the year ending March 2022, a decrease of 17 compared with the previous year

- there were a total of 4,581 persons detained by police in England and Wales under part IV of Police and Criminal Evidence Act for more than 24 hours and subsequently released without charge, this represented a decrease of 3% compared with the previous year (based on data from 36 forces that were able to provide complete data for both years)

- of those detained and subsequently released, 94% (4,290) were held for between 24 and 36 hours, a further 153 persons were held for more than 36 hours before being released without charge, and 138 people were detained under warrant for further detention for up to 96 hours

2.2 Introduction

Background

It is important that both the Government and the public can fully understand the populations entering police custody suites and the way that police powers are used. The inclusion of custody data in the annual statistical bulletin ‘Police Powers and Procedures’ will increase transparency in this area and bring detention related issues into the public domain.

The custody data included in this chapter has been developed in consultation with police forces in England and Wales, a number of key stakeholders such as the Independent Custody Visiting Association and views from national documents including:

- Dame Elish Angiolini’s report into deaths and serious incidents in police custody

- HM Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Service custody expectations document

- “Good Police Custody” research produced by Dr. Layla Skinns and Dr. Angela Sorsby

Data collection

For the first time in the year ending March 2022, the Home Office has collected data on all people who have been detained in police custody. Information on strip searches that have taken place in custody has also been collected for the first time and is presented in this chapter.

This chapter includes information and analysis on the following areas:

- number of detentions in police custody broken down by age, sex, self-defined ethnicity, and details of all offences linked to the custody record (including notifiable and non-notifiable offences)

- information on children detained in custody overnight

- whether an Appropriate Adult was called out

- whether a detained adult was declared vulnerable

- number of strip searches carried out, broken down by age, sex and ethnicity

- intimate searches carried out, broken down by age, sex, ethnicity, and offence type (these data have been collected since year 2001/02 and have been moved from what was previously the ‘Other PACE Powers’ chapter of this bulletin)

- persons detained in custody under part IV of PACE for over 24 hours and subsequently released without charge (these data have been collected since 2001/02 and have been moved from what was previously the ‘Other PACE Powers’ chapter of this bulletin)

Data quality

As is standard practice for all new data collections which are collected under the Annual Data Requirement (ADR), the police custody collection was introduced to the 2021/22 ADR as a voluntary collection to allow forces time to embed the recording processes and make changes to their systems. Some forces reported that extracting the data from their systems would not be viable for this reporting year; as such, the analysis in this chapter is based on a subset of forces that were able to provide at least some of the data requested. Therefore, the police custody and strip search data presented in this chapter should be treated with caution as it is partial and not representative of the national picture. These data have been labelled as Experimental Statistics to indicate that there are data quality issues.

Although the forces already record information on who has entered custody, recording processes are not consistent across the 43 forces and the data in forces systems does not always easily map across to the ADR format. Data collected under the ADR is done so under the Home Secretary’s statutory powers aiming to bring consistency, transparency and accountability to crime and policing related statistics. The Home Office continues to work with forces and the NPCC to improve the quality of the data in this collection, with the ambition of making the collection mandatory. All data collections are reviewed each year by the Policing Data Requirement Group (PDRG), which is comprised of Home Office analysts, policy officials and policing representatives. The PDRG must agree all changes to the ADR, including whether a collection should move from voluntary to mandatory.

For the police custody collection, we ask for details of all offences linked to an individual’s custody record, including notifiable and non-notifiable offences. The analysis presented in this chapter is based on the number of detentions - this has been done using the custody unique reference number. It is therefore possible that an individual may appear more than once in the dataset if they have been in custody on multiple occasions. Although for ease throughout the chapter we refer to the number of people detained in custody, this should not be inferred as the number of unique individuals as it is not possible to ascertain this information from the data.

Any comparisons made to the arrests data series should be done so with caution as the arrests data collection is based on notifiable offences only, whereas the custody collection is based on both non-notifiable and notifiable offences. Furthermore, the custody collection is based on a subset of the 43 police forces in England and Wales.

The strip searches data presented in this chapter relate to those carried out in police custody only; those carried out further to a stop and search are not currently collected by the Home Office. There are plans to start collecting this information from police forces from April 2023.

Analysis presented in the custody section is based on 26 out of 43 forces unless otherwise specified. For the strip searches section, analysis is based on 28 out of 43 forces (the same 26 who provided custody data plus an additional two forces). For more details on which forces provided data, please see the Custody tables.

2.3 Detentions in police custody - experimental statistics

As forces were not always able to provide all data requested, analysis presented in this chapter excludes records where the information was unknown unless otherwise specified.

Based on a subset of 26 forces, in the year ending March 2022 there were 546,170 people detained in custody, for 1.02m offences (including non-notifiable offences).

Over half (59%) of all people detained in custody were aged between 21 and 40. Those aged under 18 comprised 6% of all detainees and those aged 61 and over accounted for 3% of all detainees.

Table 2.1 - Number of people detained in police custody, by age group and selected police forces, year ending March 2022

| Age group | Number | Percentage of total |

|---|---|---|

| 10-17 years | 35,114 | 6% |

| 18-20 years | 42,731 | 8% |

| 21-30 years | 161,110 | 30% |

| 31-40 years | 160,352 | 29% |

| 41-50 years | 90,664 | 17% |

| 51-60 years | 42,143 | 8% |

| 61 and over | 13,983 | 3% |

| Unknown | 73 | |

| Total | 546,170 |

Source: D_04, Custody data tables

Notes:

- Data based on a subset of 26 forces, therefore the analysis should be interpreted with caution.

- Due to rounding, percentages may not add up to 100%.

The majority of detainees were male (85%), whilst 15% were female. A very small number (less than 0.5%) of detainees were reported as other sex. Similar proportions for male, female and other were seen for adults and children.

Around three-quarters (76%) of people detained in custody self-defined as belonging to a white ethnic group, 10% self-defined as being of black or black British background, 8% belonged to the Asian group, 4% were of a mixed ethnic background and 2% defined as belonging to any other ethnic background.

Children detained in custody had higher proportions of individuals belonging to ethnic minority backgrounds (excluding white minorities), most notably 16% of children detained were from a black or black British ethnic background compared with 10% of adults, see table 2.2 below.

Table 2.2: Ethnicity of people detained in custody, selected police forces, year ending March 2022

| All | Adults | Children | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asian | 8% | 8% | 6% |

| Black | 10% | 10% | 16% |

| Mixed | 4% | 3% | 8% |

| White | 76% | 76% | 68% |

| Other | 2% | 2% | 2% |

Source: D_01, Custody data tables

Notes:

- Excludes records where ethnicity was unknown (13% of total).

- Data based on a subset of 26 forces, therefore the analysis should be interpreted with caution.

- Due to rounding, percentages may not add up to 100%.

The table below shows the ethnic distribution of detainees more closely reflects the general population of the selected forces (according to the 2011 Census) when the Metropolitan Police Service (MPS) is excluded. This is likely due to the MPS having a more ethnically diverse resident population compared with other Police Force Areas.

Table 2.3: Ethnicity of people detained in custody, selected police forces (excluding MPS), year ending March 2022

| All | Adults | Children | 2011 Census** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asian | 6% | 6% | 4% | 6% |

| Black | 5% | 4% | 6% | 2% |

| Mixed | 3% | 3% | 6% | 2% |

| White | 86% | 86% | 83% | 90% |

| Other | 1% | 1% | 1% | 1% |

Source: D_01, Custody data tables

Notes:

- Excludes records where ethnicity was unknown (16% of total).

- Data based on a subset of 25 forces, therefore the analysis should be interpreted with caution.

- Due to rounding, percentages may not add up to 100%.

- ** 2011 Census - Office for National Statistics (ons.gov.uk).

Reason for being in custody

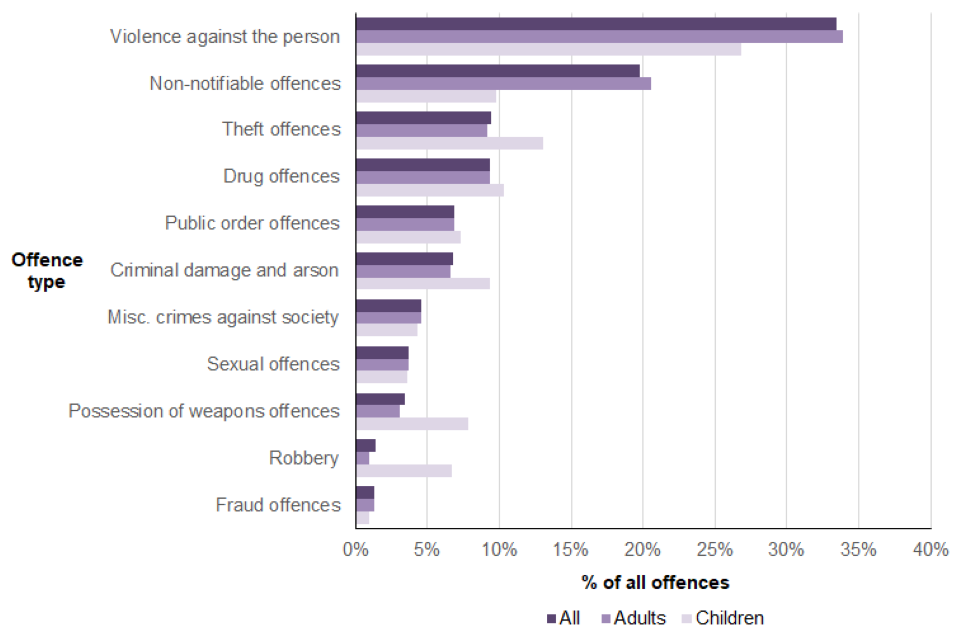

Of the 1.02 million offences for which people were detained in custody in the year ending March 2022, for 2% of the records the offence type was not known. Excluding unknowns, the most common offence was violence against the person (33% of all offences). Non-notifiable offences accounted for a fifth (20%) of all offences. Drug and theft offences each accounted for 9% of all offences. A small proportion of custody records (2%) did not have offence information.

One notable difference between adults and children was that children were more likely to be detained in custody for robbery offences, possession of weapons offences and theft offences, whilst they were less likely to be in custody for non-notifiable offences, suggesting that children were detained in custody for more serious offences, as shown in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1: Detentions in custody by offence group, selected police forces, year ending March 2022

Source: D_05, Custody data tables

Notes:

- Data based on a subset of 26 forces, therefore the analysis should be interpreted with caution.

- Due to rounding, percentages may not add up to 100%.

Appropriate Adults

Appropriate Adults (AAs) safeguard the welfare, rights and effective participation of children and vulnerable people who are detained or interviewed as suspects. It is a legal requirement for children (detainees under the age of 18) to have an AA present when they are detained in custody.

A person may be considered vulnerable if they have difficulty understanding the full implications or communicating effectively about anything to do with their detention, have difficulty understanding the significance or things they are told or questions they are asked, or be particularly prone to confusion or suggestibility. This may be due to a mental health condition or disorder but this is not a requirement.

An individual is automatically considered to be vulnerable if they are under the age of 18 years old.

Around 1 in 6 (or 17%) of adult detainees were reported as vulnerable, and an AA was called in just over two-fifths (41%) of cases where the adult was deemed to be vulnerable. For children, an AA was called in 99% of cases.

Whether an adult was deemed vulnerable varied slightly by ethnicity. Just under a fifth (18%) of adults from a white ethnic background were classed as vulnerable compared with 15% of people from a mixed ethnic background; 10% of adults who were black or black British; 9% of adults from any other ethnic background and 7% of people who self-identified as Asian or Asian British.

Vulnerability did not vary significantly by age group, ranging between 16% and 18%, whilst a slightly higher proportion of females (22%) were deemed vulnerable compared with males (16%).

Children detained overnight

The NPCC have stated that custody should only be used as a last resort for children. Specialist provision should be given to children in custody to meet their additional needs requirements of the Concordat on Children in Custody should be met. See the Further Information section of this chapter for more details.

Forces were asked to report on whether any children kept in custody were detained overnight. For the purposes of this data collection, the definition of overnight means they must have spent a minimum of 4 hours in custody and that at least part of this period in custody must be between 00:00 and 04:00, regardless of when the child entered custody. The definition in this ADR collection has been aligned and agreed with the National Police Chiefs’ Council.

Just under half (45%) of all children detained in custody were held overnight. Most children detained overnight were male (85% - the same proportion as all children detained in custody). The ethnic profile of children detained overnight was generally similar to that of all children detained in custody with a couple of exceptions; just under two-thirds (62%) of children detained overnight self-identified as white compared with 68% of all children detained in custody and around a fifth (21%) of children detained overnight were from a black or black British background compared with 16% in custody overall, see Table 2.4 below.

Table 2.4: Ethnicity of children detained overnight in custody compared with all children detained in custody, selected police forces, year ending March 2022

| Ethnicity | Childern detained overnight | All child detainees |

|---|---|---|

| Asian | 6% | 6% |

| Black | 21% | 16% |

| Mixed | 9% | 8% |

| White | 62% | 68% |

| Other | 2% | 2% |

Source: D_06, Custody data tables

Notes:

- Excludes records where ethnicity was unknown (11% for children detained overnight and 12% for total child detainees).

- Data based on a subset of 26 forces, therefore the analysis should be interpreted with caution.

2.4 Strip searches in custody - experimental statistics

Section 54 of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (PACE) permits a person to be searched if the custody officer considers it necessary to enable him to carry out his duty in ascertaining everything that the arrested person has with him and to the extent that the custody officer considers necessary for this purpose. Clothes and personal effects may only be seized if the custody officer believes that the person from whom they are seized may use them to cause physical injury to himself or any other person; to damage property; to interfere with evidence; or to assist him to escape.

A strip search in police custody is a search involving the removal of more than outer clothing (including shoes and socks). A strip search may take place only if it is considered necessary to remove an article which a detainee would not be allowed to keep and the officer reasonably considers the detainee might have concealed such an article. Conduct of these searches is covered by Code C of PACE. Strip searches shall not be routinely carried out if there is no reason to consider that articles are concealed.

Based on a subset of 28 forces (26 of whom also provided custody data), in the year ending March 2022, 65,336 people were strip searched in custody, equating to 12% of all people detained in custody (12% of adults in custody and 9% of children in custody - based on the 26 forces who could provide both custody and strip search data).

Of the people strip searched in custody, just under two-thirds (64%) were aged between 21 and 40. Around a fifth (21%) were aged over 40 and a small proportion were aged below 18 (5%). As a proportion of all people in custody within the same age group, those aged 18-20 had the highest proportion of people strip searched (15%) in custody, whereas only 3% of people aged 61 and over in custody were strip searched, see Table 2.5 below.

Table 2.5 - Number of people strip searched, by age group and selected police forces, year ending March 2022

| Age group | Number | Percentage of total strip searches | Percentage of age group strip searched in custody |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10-17 years | 3,133 | 5% | 9% |

| 18-20 years | 6,519 | 10% | 15% |

| 21-30 years | 21,579 | 33% | 13% |

| 31-40 years | 19,865 | 31% | 12% |

| 41-50 years | 10,348 | 16% | 11% |

| 51-60 years | 2,962 | 5% | 7% |

| 61 and over | 431 | 1% | 3% |

| Unknown | 499 | ||

| Total | 65,336 | 12% |

Source: SS_04, Custody data tables

Notes:

- Data based on a subset of 28 forces, therefore the analysis should be interpreted with caution.

- Proportions of age group in custody are based on the 26 forces who could provide custody data.

- Due to rounding, percentages may not add up to 100%.

The majority of those strip searched were male (87%), with females accounting for 13% and those identifying as ‘other’ less than 0.5%. Male representation was slightly higher among children (92%) compared with adults (87%).

The following analysis is based on a subset of 26 forces as two of the 28 forces were not able to provide information on ethnicity.

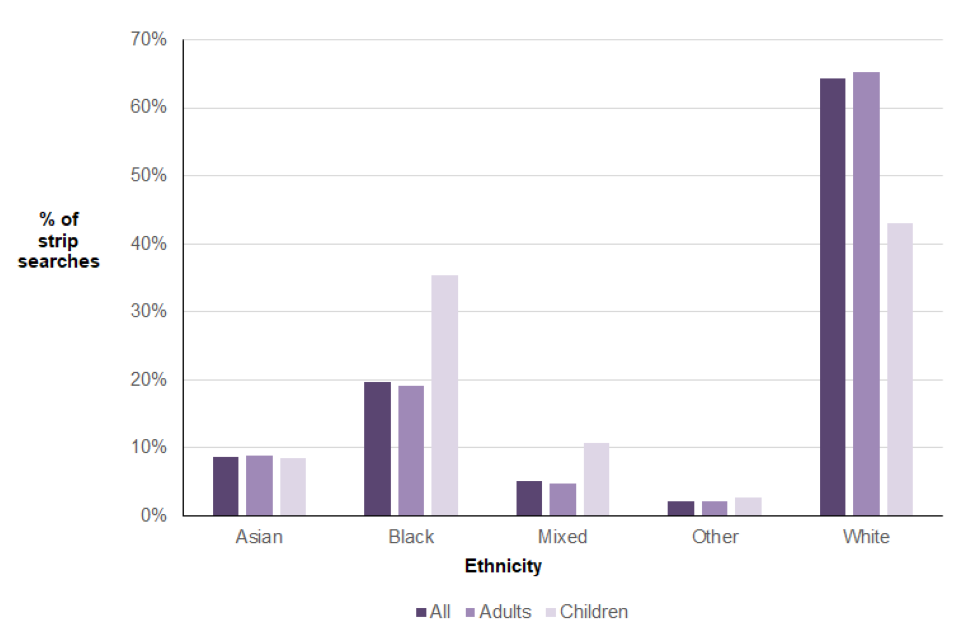

Almost two-thirds (64%) of people strip searched in custody were of a white ethnic background (compared with 76% of all people in custody), a fifth (20%) were from a black or black British background (compared with 10% in custody), 9% were of an Asian or Asian British background (similar to 8% overall in custody), 5% were of a mixed ethnic background (similar to 4% in custody) and 2% were from any other ethnic background (the same as for custody).

The most notable differences between adults and children strip searched were that higher proportions of children strip searched self-defined as being of a black or black British background compared with adults (35% compared with 19%); and less than half (43%) of all children strip searched were of a white ethnic background, compared with 65% of adults strip searched (see Figure 2.2 below).

Figure 2.2: Ethnicity of people strip searched in custody, selected police forces, year ending March 2022

Source: SS_03, Custody data tables

Notes:

- Data based on a subset of 26 forces, therefore the analysis should be interpreted with caution.

- Excludes records where the ethnicity was not known.

- Due to rounding, percentages may not add up to 100%.

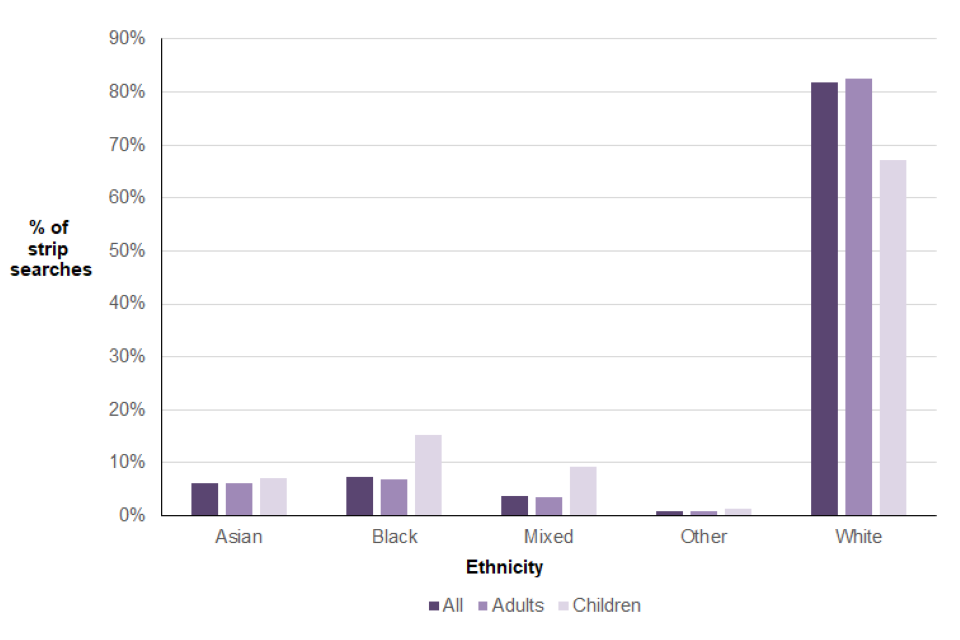

Excluding the MPS from the analysis shows higher proportions of people strip searched from a white ethnic background, although this was lower for children strip searched compared with adults (67% compared with 82% respectively). Proportions for minority ethnic groups (excluding white minorities) were lower once the MPS are excluded from the analysis although still higher for children compared with adults, see Figure 2.3 below.

Figure 2.3: Ethnicity of people strip searched, selected police forces (excluding MPS), year ending March 2022

Source: SS_03, Custody data tables

Notes:

- Data based on a subset of 25 forces, therefore the analysis should be interpreted with caution.

- Excludes records where the ethnicity was not known.

- Due to rounding, percentages may not add up to 100%.

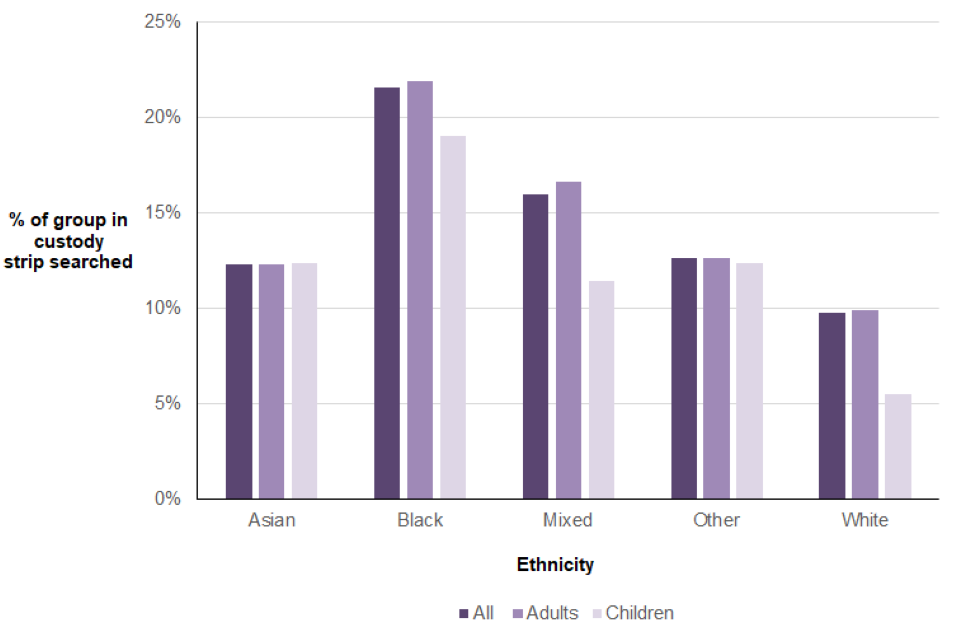

As a proportion of all those in custody, almost a quarter (22%) of people from a black or black British background were strip searched, this was followed by those of a mixed ethnic background (16%), 13% of those of any other ethnic background, 12% of Asian people and 10% of people from a white ethnic background.

For the following groups, smaller proportions of children in custody were strip searched compared with adults: those that self-defined as black or black British (19% compared with 22% respectively), mixed ethnicity (11% compared with 17%) and white (6% compared with 10%), see Figure 2.4 below.

Figure 2.4: Proportion of all people in custody strip searched, by self-defined ethnicity, selected forces, year ending March 2022

Source: SS_03, Custody data tables

Notes:

- Data based on a subset of 26 forces, therefore the analysis should be interpreted with caution.

- Excludes records where the ethnicity was not known.

- Due to rounding, percentages may not add up to 100%.

2.5 Intimate searches

If a person who is arrested is believed to be concealing Class A drugs, or anything that could be used to cause physical injury, a suitably qualified person may carry out an intimate search under section 55 of PACE. This section includes data on the number of intimate searches carried out by police in England and Wales, as well as details of who conducted the search and why, on a financial-year basis. Additionally, for the first time, data has been collected on the age, sex and ethnicity of persons subjected to an intimate search. Further details can be found in the user guide.

Based on the 42 forces who could supply data, there were 19 intimate searches carried out by police in the year ending March 2022, a decrease of 17 compared with the previous year, in which 36 intimate searches were carried out. All 19 of the intimate searches in the latest year were carried by a medical practitioner or other suitably qualified person.

Fifteen intimate searches were made in an attempt to find Class A drugs (79% of the total), with the remaining 4 searches conducted to find harmful articles. This is consistent with breakdowns for recent years, where around 80% to 90% of searches were conducted to find Class A drugs. Of the searches made for drugs in the latest year, Class A drugs were found in 27% of cases, the same as the previous year. No harmful articles were found in the 4 searches conducted to find them.

Twelve intimate searches were undertaken on males and 7 on females. All of the persons searched were over 18.

Eleven of the intimate searches were undertaken on people who self-defined their ethnicity as white, 4 were black, 2 were Asian, 1 was mixed ethnicity and 1 person did not state their ethnicity.

Of the 42 police forces in England and Wales who supplied data to the Home Office, 11 had carried out intimate searches in the year ending March 2022. Merseyside Police, Essex Police and Norfolk Constabulary each carried out 3 intimate searches in the year ending March 2022.

2.6 Detentions in custody over 24 hours

Under section 42 of PACE, police may detain a suspect before charge, usually for a maximum of 24 hours, or for up to 36 hours when an alleged offence is an indictable[footnote 1] one. From 20 January 2004, powers were introduced which enabled an officer of the rank of superintendent or above to authorise continued detention for up to 36 hours following an arrest. Additionally, police may apply to the Magistrates’ Court to authorise warrants of further detention, extending the detention period to a maximum of 96 hours without charge. Further details can be found in the user guide.

This section provides information on the number of persons detained for more than 24 hours who were subsequently released without charge. It also provides details on the number of warrants for further detention that were applied for and that led to charges. Data are requested by the Home Office from the 43 territorial police forces in England and Wales on a financial-year basis, though not all forces have been able to provide these data due to technical issues and data quality concerns.

In the year ending March 2022, there were a total of 4,581 persons detained by police in England and Wales under part IV of PACE for more than 24 hours and subsequently released without charge. This represented a decrease of 3% compared with the previous year, based on data from 36 forces who were able to provide complete data for both years (from 4,640 in the year ending March 2021 to 4,509 in the year ending March 2022).

Of those detained and subsequently released without charge, 94% (4,290) were held for between 24 and 36 hours. A further 153 persons were held for more than 36 hours before being released without charge and 138 were detained under warrant for further detention (before being released without charge).

In the year ending March 2022, police in England and Wales applied to magistrates for 461 warrants of further detention. Of these applications 13 were refused, meaning warrants were granted in 97% of cases, a similar proportion to previous years. The majority of extensions were granted for an additional 24 to 36 hours (321 out of 448 warrants granted).

When a warrant of further detention was granted, this led to a charge in 58% of cases (261 cases). This proportion is down slightly compared to the last four years, in which 60-63% of warrants of further detention led to a charge.

Source: Other Pace Powers data tables, D_01 to D_04, Home Office

Data quality

The presented statistics in this section are correct at the time of publication. Cheshire, Durham, Gloucestershire, Greater Manchester, North Wales and Thames Valley police forces were unable to provide complete detentions data for the year ending March 2022. The reason for this was normally that accurate data could not be retrieved from their record management systems.

These forces, along with those who could not provide complete data for the year ending March 2021, have been excluded from any year on year comparisons, as outlined in the footnotes accompanying the detentions tables.

The user guide provides further details relating to definitions, legislation and procedures, and data quality.

2.7 Further information

It is vital that both the Government and the public can fully understand the populations entering police custody suites and the way that police powers are used. The inclusion of custody data in the annual statistical bulletin ‘Police Powers and Procedures’ will increase transparency in this area and bring detention related issues into the public domain.

The custody data included here has been developed in consultation with police forces in England and Wales, a number of key stakeholders and influencing national documents including: Dame Elish Angiolini’s report into deaths and serious incidents in police custody; HM Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Service custody expectations document; views from the Independent Custody Visiting Association and the key findings from the “Good Police Custody” research produced by Dr. Layla Skinns and Dr. Angela Sorsby.

Legislation - Appropriate Adults

Public concern over the Maxwell Confait murder case in 1972 led Parliament, via a Royal Commission, to pass the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (PACE) and its Codes of Practice. PACE sets out the rules and safeguards for policing in England and Wales including role of the appropriate adult.

The principal intention of the appropriate adult safeguard was to reduce the risk of miscarriages of justice as a result of evidence being obtained from children and vulnerable persons which, by virtue of their age and/or vulnerability, could lead to unsafe and unjust convictions. The role of the appropriate adult therefore is to safeguard the rights, entitlements and welfare of children and vulnerable persons to whom the Codes of Practice apply. Under PACE Code C, the police must secure an appropriate adult as soon as is practicable if, at any time, an officer has any reason to suspect that the person is either a child or is vulnerable. The appropriate adult is a mandatory procedural safeguard imposed on police and, unlike legal advice, is not waivable by the person suspected of an offence.

The ‘appropriate adult’ means, in the case of a child under the age of 18:

- the parent, guardian or, if the child is in the care of a local authority or voluntary organisation, a person representing that authority or organisation

- a social worker of a local authority

- if these are not available then some other responsible adult aged 18 or over who is not: a police officer, employed by the police or under the direction or control of the chief officer of a police force, or a person who provides services

Legislation - children in custody

Pre-charge detention of children:

Officers must work in accordance with the College of Policing Authorised Professional Practice and take into account the age of a child or young person when deciding whether any of the PACE Code G statutory grounds for arrest apply. They should pay particular regard to the timing of any necessary arrests of children and young people and ensure that they are detained for no longer than needed in accordance with PACE Code C, paragraph 1.1. (All persons in custody must be dealt with expeditiously, and released as soon as the need for detention no longer applies).

Reviewing inspectors and custody officers should ensure that the provisions of PACE have been strictly applied to avoid keeping children and young people in police custody any longer than necessary, both pre- and post-charge.

Post-charge detention of children:

Under s38 Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 the detention of a child (who has not been arrested on a warrant or for breach of bail) after charge at a police station is permissible where it is impracticable for them to be released or where the child has attained the age of 12 years and no secure accommodation is available and that keeping him in other local authority accommodation would not be adequate to protect the public from serious harm from him. If either of the above conditions are not met the arrested child must be moved to local authority accommodation.

The Government published the ‘Concordat on Children in Custody’ in 2017 which clearly sets out the statutory duties of the police and local authorities and provides a protocol for how transfers of children from custody to local authority accommodation should work in practice. The Concordat recognises that different agencies must work in partnership to ensure that legal duties are met. A diverse group of agencies has contributed to its development, acknowledging the fact that a child’s journey from arrest to court is overseen by a variety of professionals with varying duties.

Legislation - Strip searches

Section 54 of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (PACE) permits a person to be searched if the custody officer considers it necessary to enable him to carry out his duty in ascertaining everything that the arrested person has with him and to the extent that the custody officer considers necessary for this purpose. Clothes and personal effects may only be seized if the custody officer believes that the person from whom they are seized may use them to cause physical injury to himself or any other person; to damage property; to interfere with evidence; or to assist him to escape.

The officer can search the detainee (excluding intrusion into a body orifice except for the mouth) and their property with them whilst in police custody.

A strip search in police custody is a search involving the removal of more than outer clothing (including shoes and socks). A strip search may take place only if it is considered necessary to remove an article which a detainee would not be allowed to keep and the officer reasonably considers the detainee might have concealed such an article. Conduct of these searches is covered by Code C of PACE. Strip searches shall not be routinely carried out if there is no reason to consider that articles are concealed.

The reasons and extent for a s54 PACE search of a detainee will be based on the principle of ensuring that police custody is a safe and secure environment for everyone and the need to secure and preserve evidence. The extent of such a search would be determined by such matters as the offence for which the detainee has been arrested, intelligence known about the detainee (this could include admissions), their behaviour amongst other factors so that justification can be provided.

The conduct of strip searches (including safeguards for children and vulnerable persons)

When strip searches are conducted:

A police officer carrying out a strip search must be the same sex as the detainee.

The search shall take place in an area where the detainee cannot be seen by anyone who does not need to be present, nor by a member of the opposite sex except an appropriate adult who has been specifically requested by the detainee.

Except in cases of urgency, where there is risk of serious harm to the detainee or to others, whenever a strip search involves exposure of intimate body parts, there must be at least two people present other than the detainee, and if the search is of a child or vulnerable person, one of the people must be the appropriate adult. Except in urgent cases as above, a search of a child may take place in the absence of the appropriate adult only if the child signifies in the presence of the appropriate adult that they do not want the appropriate adult to be present during the search and the appropriate adult agrees. A record shall be made of the child’s decision and signed by the appropriate adult. The presence of more than two people, other than an appropriate adult, shall be permitted only in the most exceptional circumstances.

The search shall be conducted with proper regard to the dignity, sensitivity and vulnerability of the detainee in these circumstances, including in particular, their health, hygiene and welfare needs. Every reasonable effort shall be made to secure the detainee’s co-operation, maintain their dignity and minimise embarrassment. Detainees who are searched shall not normally be required to remove all their clothes at the same time, e.g. a person should be allowed to remove clothing above the waist and redress before removing further clothing.

If necessary to assist the search, the detainee may be required to hold their arms in the air or to stand with their legs apart and bend forward so a visual examination may be made of the genital and anal areas provided no physical contact is made with any body orifice.

If articles are found, the detainee shall be asked to hand them over. If articles are found within any body orifice other than the mouth, and the detainee refuses to hand them over, their removal would constitute an intimate search, which therefore must be carried out in accordance with the requirements of an intimate search.

A strip search shall be conducted as quickly as possible, and the detainee allowed to dress as soon as the procedure is complete.

Even though a strip search is not classified as an intimate search (which consists of the physical examination of a person’s body orifices other than the mouth) the search may still involve the exposure of intimate parts of the body which may or may not be body orifices.

Legislation - Intimate search

If a person who is arrested and in police detention is believed to be concealing Class A drugs, or anything that could be used to cause physical injury, a suitably qualified or authorised person may carry out an intimate search under section 55 of PACE.

An intimate search consists of the physical examination of a person’s body orifices other than the mouth. Body orifices other than the mouth may be searched only if:

- authorised by an officer of inspector rank or above who has reasonable grounds for believing that the person may have concealed on themselves

- anything which they could and might use to cause physical injury to themselves or others at the station

- a Class A drug which was in their possession with the appropriate criminal intent before their arrest

If the search is for drugs, the detainee’s appropriate consent must be given in writing.

An intimate search may only be carried out by a registered medical practitioner or registered nurse, unless an officer of at least inspector rank considers this is not practicable and the search is to take place for an item that could cause injury in which case a police officer may carry out the search. Any proposal for such a search to be carried out by someone other than a registered medical practitioner or registered nurse must only be considered as a last resort and when the authorising officer is satisfied the risks associated with allowing the item to remain with the detainee outweigh the risks associated with removing it.

The intimate search for an item that could cause injury may take place only at a hospital, medical surgery, other medical premises or police station. The intimate search for drugs may take place only at a hospital, medical surgery or other medical premises and must be carried out by a registered medical practitioner or a registered nurse.

In the case of a child or a vulnerable person, the seeking and giving of consent must take place in the presence of the appropriate adult. A child’s consent is only valid if their parent’s or guardian’s consent is also obtained unless the child is under 14, when their parent’s or guardian’s consent is sufficient in its own right.

An intimate search at a police station of a child or vulnerable person may take place only in the presence of an appropriate adult of the same sex unless the detainee specifically requests a particular appropriate adult of the opposite sex who is readily available. In the case of a child, the search may take place in the absence of the appropriate adult only if the child signifies in the presence of the appropriate adult that they do not want the appropriate adult present during the search and the appropriate adult agrees.

When an intimate search for an item that could cause injury is carried out by a police officer, the officer must be of the same sex as the detainee. A minimum of two people, other than the detainee, must be present during the search. The search shall be conducted with proper regard to the dignity, sensitivity and vulnerability of the detainee including in particular, their health, hygiene and welfare needs.

3. Detentions under section 136 of the Mental Health Act 1983

Key results

In the year ending March 2022:

-

there were 36,594 detentions under section 136 of the Mental Health Act 1983. This was an 8% increase compared with the previous year (excluding Dyfed-Powys who were unable to provide data in the year ending March 2021), and a 7% increase compared to the year prior to the pandemic

-

where the details were known, 52% were detentions of males, 94% of cases were adults aged 18 or over and 84% were detentions of people from the white ethnic group

-

where the details were known, the person being detained was taken to a health-based place of safety in over two-thirds (68%) of cases. Twenty-nine per cent of detainees were taken to Accident and Emergency as a place of safety, and 264 people (0.8%) were taken to a police station

3.1 Introduction

Police forces in England and Wales regularly interact with people experiencing mental ill health. Sometimes these interactions may result in the need to remove a person from where they are, and take them to a place of safety, under sections 135 and 136 of the Mental Health Act 1983. This chapter relates to detentions under section 136 only. See Chapter 7 for information on detentions under section 135 of the Mental Health Act 1983.

Under section 136 of the Mental Health Act a police officer may remove a person from any public place, other than a private dwelling, to a place of safety if, in the officer’s judgement, that person appears to be suffering from a mental disorder and needs immediate care or control, in the interests of their safety or that of others to be assessed by an approved mental health professional and an approved s12 doctor. The maximum period for which a person can be detained at a place of safety under sections 135 or 136 is usually up to 24 hours, with the possibility of this period being extended by a further 12 hours if a person could not be assessed for clinical reasons.

Data Collected

Following concerns raised about the quality and transparency of police data in this area, at the Policing and Mental Health Summit in October 2014 the then Home Secretary announced that the Home Office would work with the police to develop a new data collection covering the volume and characteristics of detentions under the Mental Health Act 1983.

A data collection was developed which requests forces to provide information on the age, sex and ethnicity of people detained, as well as the place of safety used (including, where applicable, the reason for using police custody), and the method of transportation used (including, where applicable, the reason for using a police vehicle).

In this report, we refer to the sex of people detained. We are reporting the data in the format they are collected and we are working to bring these data in line with Government Statistical Service sex and gender harmonisation standards.

This section summarises the findings on detentions under section 136 from police forces in England and Wales, as well as the British Transport Police, for the year ending March 2022. Prior to 2016/17, data on the total number of section 136 detentions were collected and published by the National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC), available here.

Dyfed-Powys were not able to supply data for the year ending March 2021, and provided partial data for the year ending March 2022. They have therefore been excluded from year-on-year comparisons of the total number of detentions under section 136, however have not been excluded from statistics on sex, ethnicity, place of safety, method of transport to place of safety, or reason taken to a police station. Additionally, some forces mentioned improvements to recording practices in the latest year. Therefore, caution should be taken when interpreting changes between the latest year and the previous year.

3.2 Detentions under section 136 of the Mental Health Act 1983

In the year ending March 2022 there were 36,594 detentions under section 136 of the Mental Health Act 1983.

When comparing forces who were able to submit complete data in both years[footnote 2], this was an increase of 8% compared with the previous year, and an increase of 7% compared with the year prior to the pandemic, ending March 2020. Detentions under section 136 had been increasing between the year ending March 2018 and the year ending March 2020, but fell during the year ending March 2021 (the year of the pandemic), before increasing again in the latest year.

Of the cases where the sex of the person being detained was recorded (98%), 52% were male detainees.

The majority of cases (94%) involved adults aged 18 or over (excluding those cases where the age of the person being detained was not recorded).

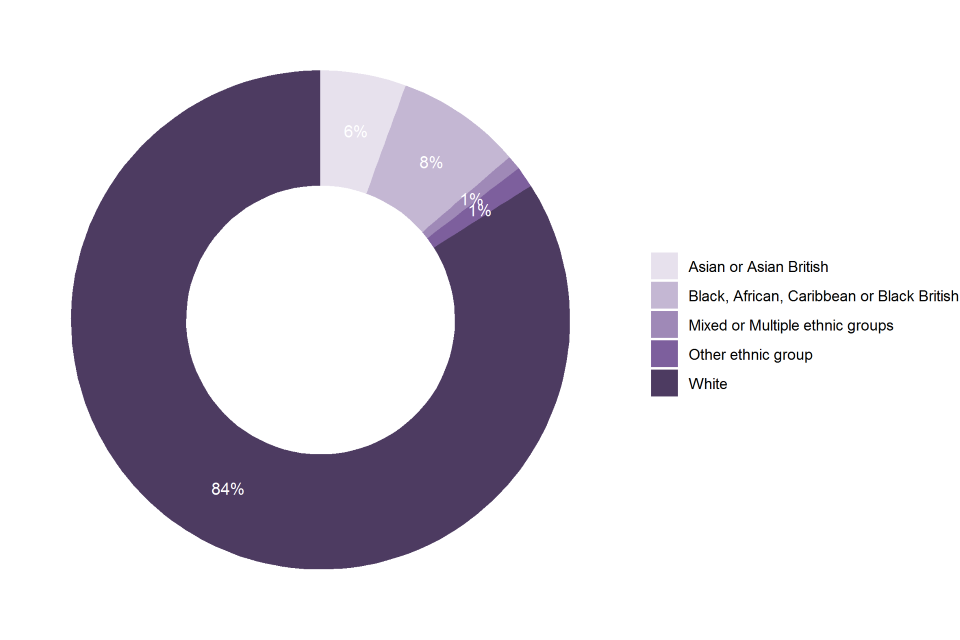

In terms of the self-defined ethnicity of those being detained (excluding those cases where the self-defined ethnicity was not recorded):

- 84% were White

- 8% were Black, African, Caribbean or Black British

- 6% were Asian or Asian British

- 1% were of mixed or multiple ethnic groups

- the remaining 1% of people detained were of another ethnic group

Figure 3.1 Self-defined ethnicity of those detained under section 136 of the Mental Health Act 1983, England and Wales, year ending March 2022

Source: Table MHA_03, Home Office

Notes:

- Excludes those cases where the ethnicity was not known.

Method of transport to a place of safety

Some forces were unable to distinguish the method of transport used to transport a person to a place of safety. This resulted in the method of transport for 9% of cases being recorded as “not known”. Of those cases where the method of transport was recorded, a police vehicle was used in just over half (18,131 or 54%) of cases. This was up from the previous year (44%) but more similar to the year before the pandemic (51%) and prior years. An ambulance was used in a further 13,568 (41%) of cases. Opposite to the trend seen in use of police vehicles, the proportion of cases where an ambulance was used was down on last year (52%), but with a smaller increase when compared to the year before the pandemic (45%). The remaining 5% were ‘None (already at a place of safety)’, ‘Other health vehicle’, or ‘Other’. However, the most common method of transport used varied greatly by police force area. For example, a police vehicle was used in 11% of detentions in West Midlands (excluding unknowns), but for over 90% of detentions in some police force areas of Wales and the North East.

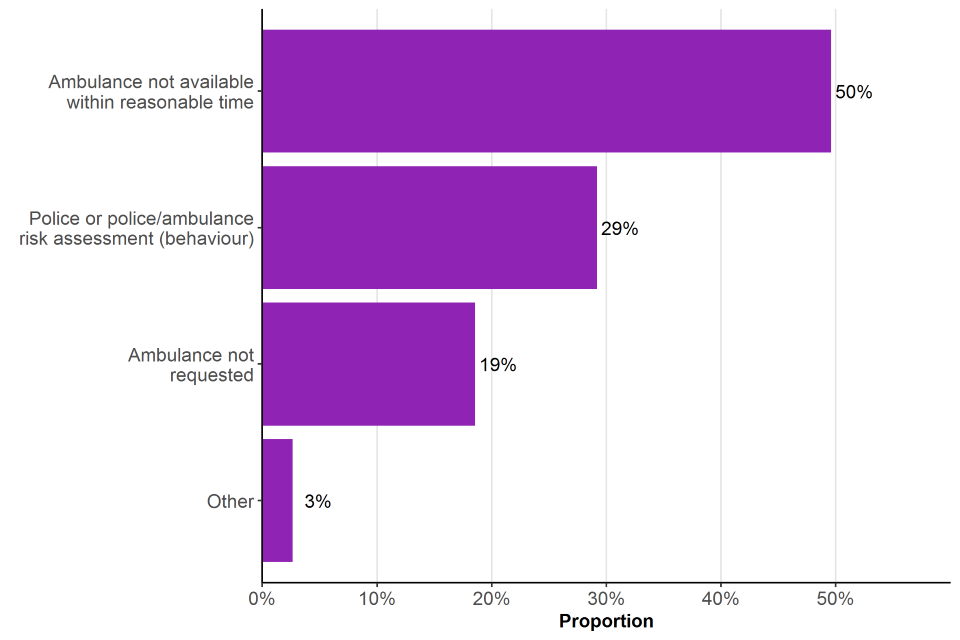

In the case where a police vehicle was used to transport the person to a place of safety, police forces are requested to give a reason why. In the 18,131 cases where a police vehicle was used, the reason why was “not known” in 2,724 cases (15%). Of those cases where the reason for using a police vehicle was recorded, 50% were because an ambulance was not available in a reasonable amount of time, up from 28% in the previous year and 38% in the year ending March 2020 prior to the pandemic. In a further 19% of cases, an ambulance was not requested. Some forces reported increased difficulty in acquiring an ambulance due to increased pressures on the ambulance service. There were also 4,498 cases (29%) where a risk assessment concluded the person being detained should be transported in a police vehicle due to their behaviour. The remaining cases (3%) were for other reasons including where an ambulance was re-tasked to a higher priority call and when an ambulance crew refused to convey.

Figure 3.2 Reasons for using a police vehicle to transport a detainee to a place of safety, England and Wales, year ending March 2022

Source: Table MHA_04b, Home Office

Notes:

- Excludes those cases (2,724) where the reason for using a police vehicle was not known.

- Other includes cases where an ambulance was re-tasked to a higher priority call and when an ambulance crew refused to convey.

Place of safety

Following a detention under section 136 of the Mental Health Act, a place of safety was recorded in 94% of cases. Of the cases where the place of safety was known, over two-thirds (68%) of detainees was taken to a health-based place of safety (HBPOS), down from 77% and 73% in each of the last two years. Over a quarter (29%) of people were taken to Accident and Emergency as a place of safety in the latest year. This was up from 18% in the previous year, and 21% in the year ending March 2020. 264 people (0.8%) were taken to a police station.

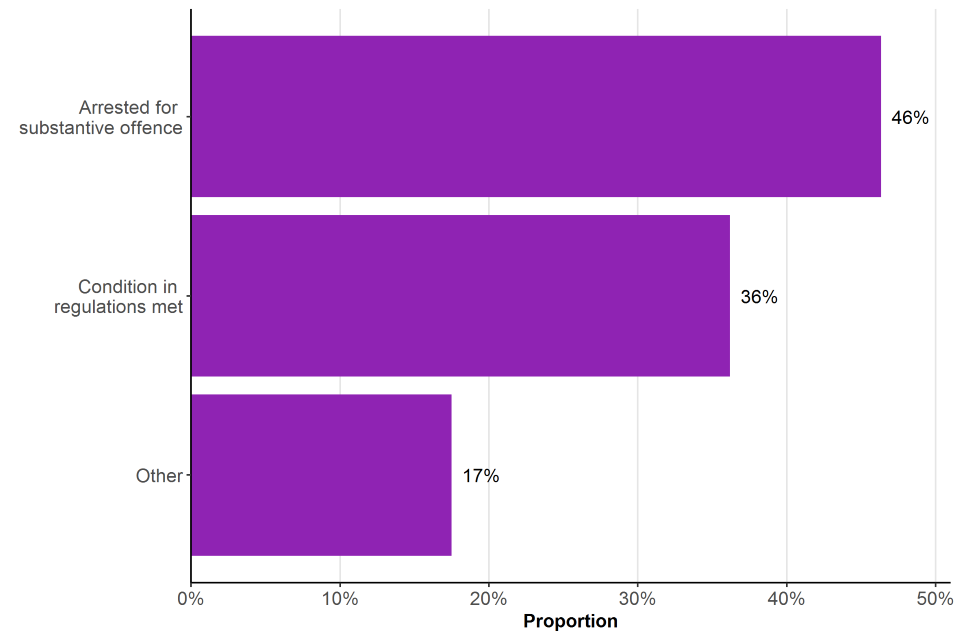

In those cases where the person being detained was taken to a police station (excluding those cases where the reason is not known)[footnote 3]:

- 46% were arrested for committing an offence

- 36% were because conditions in Regulations were met[footnote 4]

- 17% were for another reason

Figure 3.3 Reasons for the detainee being taken to a police station, England and Wales, year ending March 2022

Source: Table MHA_05b, Home Office

Notes:

- Excludes those cases where the reason for using a police station was not known.

New provisions contained in the Policing and Crime Act 2017 and designed to improve outcomes for people in mental health crisis, came into effect on 11 December 2017. These included banning the use of police cells for under 18s in mental health crisis and ensuring that they can only be used as a place of safety for adults in genuinely exceptional circumstances. Where age and place of safety were reported, there was one under 18 taken to police custody as a place of safety in the latest year.

3.3 Other data sources

As part of its annual Mental Health Bulletin, NHS Digital (formerly the Health and Social Care Information Centre) publishes data on inpatients detained in hospitals in England under the Mental Health Act 1983. Although these numbers will include some cases where the police initially detained the individual, they will also include a large number of other cases where the police were not involved. The latest data can be found here: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/mental-health-act-statistics-annual-figures/2021-22-annual-figures.

Data on the number of occasions where a HBPOS was used can differ between the NHS Digital data and the NPCC data, due to the different data sources used.

4. Breath tests

Key results

In the year ending December 2021:

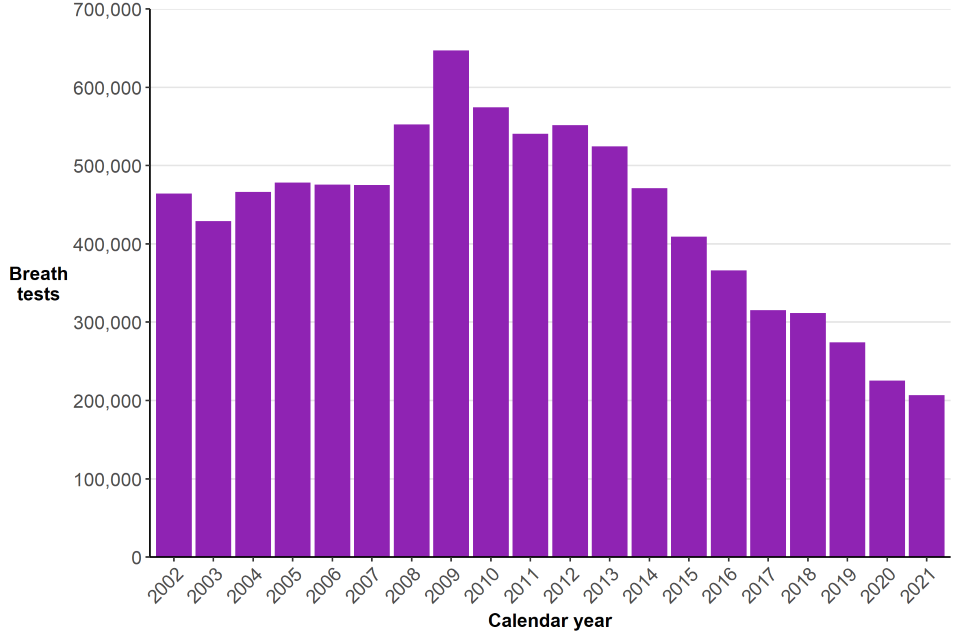

There were 224,162 breath tests carried out by police, a 7% fall compared with the previous year (when comparing data for 40 forces who were able to provide full data in both years). Additionally, the level of breath tests in 2021 was 23% below the number in 2019 (291,326).

This fall continues the downward trend seen since the peak of 709,512 breath tests in 2009.

As in previous years, more breath tests were undertaken in December than any other month, coinciding with police drink and drug driving campaigns.

Seventeen per cent of breath tests were positive or refused, a similar proportion to the previous year.

4.1 Introduction

Under the Road Traffic Act 1988, police may conduct a breath test at the roadside to determine whether motorists are driving with alcohol in their body, beyond the prescribed limit.

This section includes data on the number of breath tests carried out by police in England and Wales (excluding BTP). It presents data on a calendar-year basis up to and including 2021. The data show the number of:

-

breath tests carried out by police in England and Wales

-

positive/refused breath tests

-

breath tests conducted per 1,000 population in each police force across England and Wales

Further details relating to definitions, legislation and procedure are given in the user guide.

4.2 Trends in breath tests

The Metropolitan Police have been unable to provide data on the total number of breath tests since 2017, and are therefore not included in the national totals presented in this chapter and have also been excluded from previous years’ totals. However, they were able to supply information on the number of positive tests in both years.

Cambridgeshire Constabulary and Hertfordshire Constabulary were unable to provide accurate breath test data for 2021, due to technical issues with their breath test database. Their data has been excluded from year-on-year comparisons. The issues are being investigated, with the aim of providing a complete data set when these statistics are next published.

There were 224,162 breath tests undertaken in 2021 (excluding the three forces outlined at the start of this section). When comparing the 40 forces that provided full breath test data in both 2020 and 2021, there was a 7% fall compared with the previous year (from 241,577 in 2020 to 224,162 in 2021). Figure 3.1 shows how this fall continues the downward trend seen since the peak of 709,512 breath tests in 2009 (again excluding the forces who could not provide complete data in 2020 or 2021).

Figure 4.1 Number of breath tests carried out by police in England and Wales, 2002 to 2021

Source: Breath test table BT.03, Home Office

Notes:

- Excludes Cambridgeshire, Hertfordshire, Metropolitan, Norfolk, Suffolk and Sussex Police, who could not supply complete data for all years.

In 2021, there were 40,861 positive or refused breath tests. Based on the 41 forces who supplied complete data for 2020 and 2021, there was an 8% decrease in the number of positive or refused breath tests in 2021 (from 44,348 to 40,861).

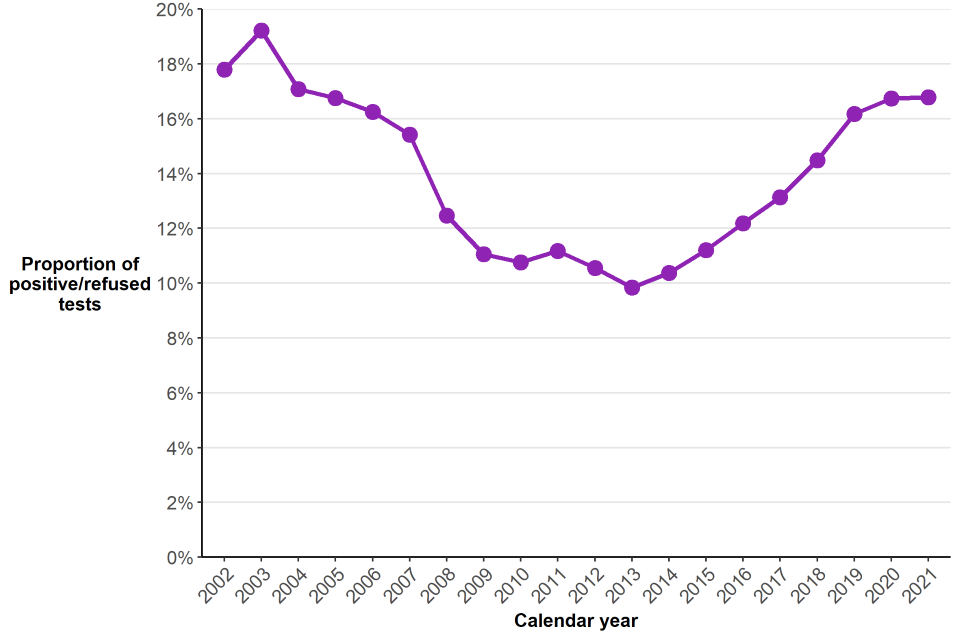

The number of positive or refused breath tests in 2021 represents 17% of the total number of breath tests, similar to the previous year. The proportion of breath tests that were positive or refused gradually fell from 19% in 2003 to 10% in 2013. From 2014 to 2020 there has been a gradual increase in the proportion of breath tests that were positive or refused, from 10% to 17%.

Figure 4.2 Proportion of positive/refused breath tests carried out by police in England and Wales, 2002 to 2021

Source: Breath test table BT.033, Home Office

Notes:

- Excludes Cambridgeshire, Hertfordshire, Metropolitan, Norfolk, Suffolk and Sussex Police, who could not supply complete data for all years.

4.3 Seasonal variation

This section also excludes data for Cambridgeshire Constabulary, Hertfordshire Constabulary and Metropolitan Police, who were unable to provide data on number of breath tests performed. Additionally, the figures in this section for the year 2021 exclude City of London Police, who were unable to provide breath tests data in January to April 2021.

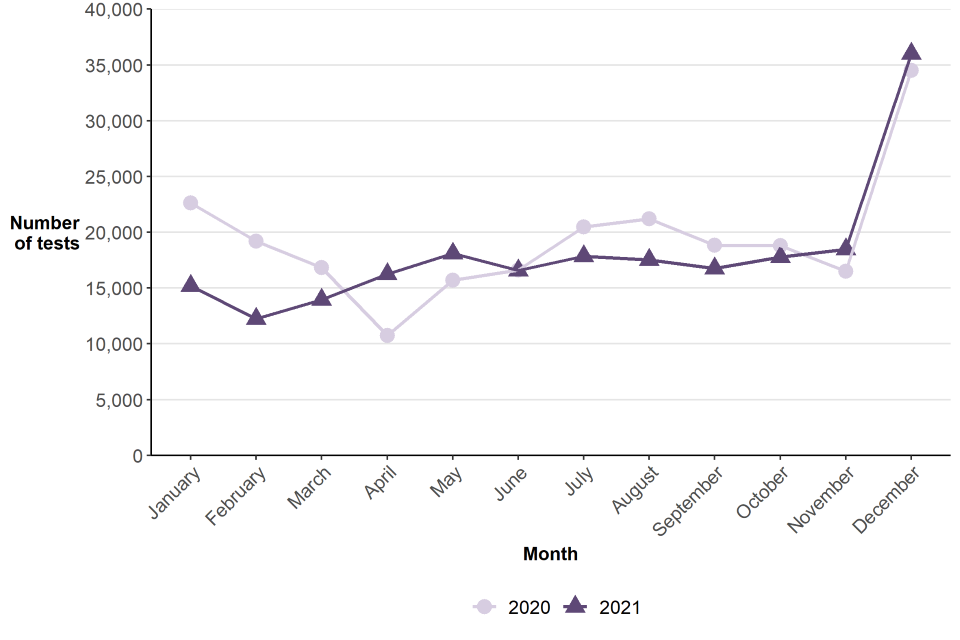

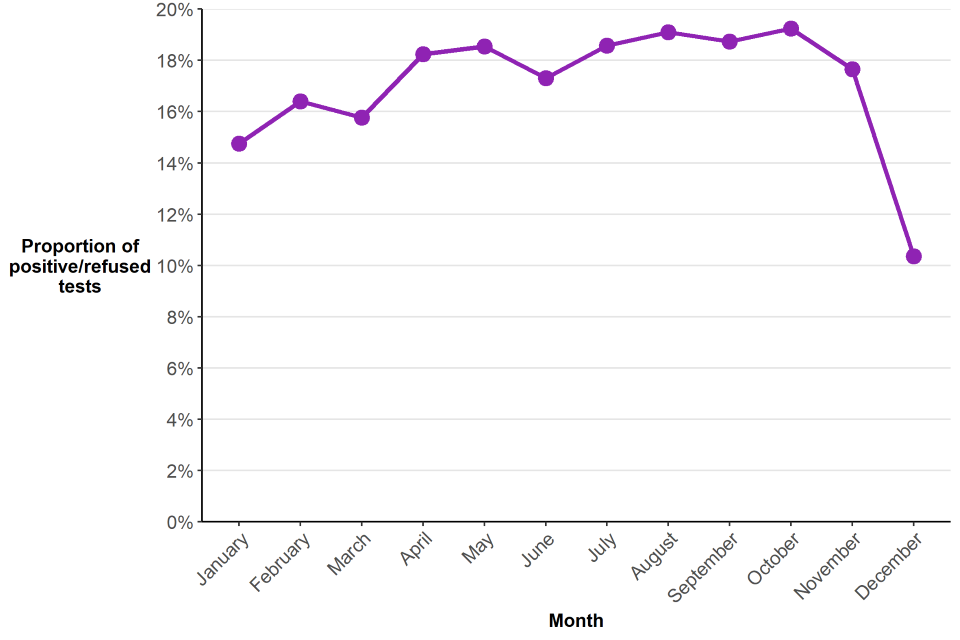

In 2021, as in previous years, more breath tests were carried out in December than any other month (37,067). This coincided with the annual national Christmas drink and drug driving campaign. Despite the overall number of breath tests in 2021 being lower than 2020, the number of breath tests in December was up by 2% from 2020 (when comparing forces who submitted full data for both years). This may be partly due to some police forces cancelling their Christmas drink and drug driving campaigns in 2020, with fewer drivers on the road during the COVID-19 pandemic. In total, 17% of breath tests in 2021 took place in December, up 2 percentage points compared with December 2020. However, December 2021 had the lowest proportion of tests that were positive or refused (10%).

February had the lowest number of breath tests (12,828) in 2021. This was down by more than a third (36%) on the number of breath tests carried out in the same month in 2020.

Trends in breath tests in 2020 were largely influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic. Carrying out a breath test requires the officer to stand close to the driver, and police forces cited minimising close contact with the public, fewer cars being out on the road, and closure of the night-time economy resulting in less offences as reasons for fewer breath tests being carried out during periods of national lockdown. Additionally, many forces reported cancelling their summer drink-drive campaign in 2020, which in previous years had led to a small peak in the number of breath tests in June.

The largest monthly increase in 2021 compared with the corresponding month in 2020 was in April. In April 2021, there were 16,598 breath tests conducted, an increase of 48% compared with April 2020.

Figure 4.3 Number of breath tests carried out by police in England and Wales, by month, 2020 and 2021

Source: Breath test table BT.043, Home Office

Notes:

- Excludes North Wales Police, who were unable to provide breath tests data for November 2020, City of London Police who were unable to provide data for January to April 2021 and Bedfordshire Constabulary, Hertfordshire Constabulary and Metropolitan Police, who were unable to provide data on the number of tests in 2021.

Excluding December, the percentage of tests which were positive or refused varied between 15% and 19% in each month, which is similar to previous years.

Figure 4.4 Proportion of positive/refused breath tests carried out by police in England and Wales, by month, 2021

Source: Breath test table BT.043, Home Office

Notes:

- Excludes the Cambridgeshire Constabulary, Hertfordshire Constabulary, Metropolitan Police and City of London Police.

4.4 Geographical patterns

In 2021, excluding Cambridgeshire Constabulary, Hertfordshire Constabulary and Metropolitan Police who were unable to supply complete data, 5 breath tests were conducted per 1,000 population across England and Wales. The rate for Wales (6 per 1,000 population) was greater than that for England (5 per 1,000 population), which has been true for recent years.

As with previous years, North Wales Police had the highest rate of breath tests per population in England and Wales (10 per 1,000 population). In England, Durham Constabulary had the highest rate with 9 tests per 1,000 population, whereas Lincolnshire Police had the lowest rate with 2 tests per 1,000 population. The proportion of breath tests that were positive or refused ranged from 9% in Cleveland to 33% in West Yorkshire Police Force Area.

4.5 Data quality and interpreting the figures

Results of breath alcohol screening tests can only be regarded as indicative of the level of alcohol present in a sample of breath and are not used to determine whether or not a driver was above or below the legal limit to drive. It remains the case that it is only at a police station or hospital that a specimen(s) can be obtained to determine a person’s actual alcohol concentration, using pre-calibrated evidential devices ensuring the sample has not been affected by any interfering substances or that blood or urine specimens may be taken for subsequent laboratory analysis. These subsequent evidential tests are not included in the breath test statistics.

From April 2008, new digital recording equipment started to be used by forces. The devices are able to record exact breath alcohol readings and the result of individual tests, as well as reason for test, time of day, day of week and age and gender profiles of those tested, and results are downloaded to data systems on a monthly basis and provided to the Department for Transport (DfT).

Data presented here have been sourced from annual statistical returns received from the 43 police forces in England and Wales. By 2011, a large number of police forces in England and Wales had made greater use of the digital breath test devices, in comparison with previous years. However, the manual recording systems are still used by some police forces. The figures presented here are based on the combined results of both systems. Negative breath test data supplied to the Home Office may have been under-reported based on the old system and it is likely that moving to the digital services has led to improvements in data recording practices by forces. This appears to have been reflected in the decrease in the proportion of positive or refused tests of total breath tests, since the beginning of 2008.

The user guide provides further details relating to data quality and interpreting the figures.

4.6 Other data sources

Analysis of reported roadside breath alcohol screening tests, based on data from digital breath testing devices, is published by the Department for Transport (DfT). Latest figures were included within DfT’s Reported road casualties in Great Britain: 2021 annual report.

5. Fixed Penalty Notices and other outcomes for motoring offences

Key results

In the year ending December 2021:

- excluding 527,021 cancelled cases, there were 2.8 million motoring offences recorded in 2021 which resulted in a Fixed Penalty Notice or another outcome, an increase of 17% compared with the previous year (2.4 million)

- compared with 2019 (pre-pandemic) there was a 5% increase in motoring offences similar to increases seen between 2017 and 2019

- over four-fifths (86%) of recorded motoring offences were for speed limit offences (2.4 million) up 19% on the previous year (2.0 million) and 6% on 2019 (2.3 million, pre-pandemic), the increase in 2021 resumes the year-on-year increases seen since 2011 with the exception of 2020 when speed limit offences fell during the pandemic

- almost half (47%) of driving offences resulted in driver retraining, while a fine was paid in a further 37% of cases and 15% of cases involved court action (excluding those subsequently cancelled), similar proportions to 2020 and 2019

5.1 Introduction

A fixed penalty notice (FPN) is a prescribed financial penalty which may be issued to a motorist as an alternative to prosecution. They can be issued for a limited range of motoring offences, such as speeding offences and using a handheld mobile phone while driving. An FPN can be endorsable (accompanied by points on a driving licence) or non-endorsable (not accompanied by points on a driving licence).

Data in this section are extracted from the PentiP system, a central database, which replaced the Vehicle Procedures and Fixed Penalty Office (VP/FPO) system in 2011. VP/FPO data were previously supplied to the Home Office by individual police forces. Further information can be found in the user guide.

In 2020 the Metropolitan Police Service (MPS) stopped processing Notice for Intended Prosecutions (NIPs) for camera-detected motoring offences through the PentiP system. Instead, they began to use their own internal StarTraq adjudication system to record and process camera-detected motoring offences and their subsequent disposals.

As such, the data the Home Office publish for MPS is a combination of data received from the PentiP system and data provided directly from the MPS StarTraq system. This change in recording practices is unlikely to affect the total number of motoring offences the Home Office receive and the way in which disposals are recorded. The data is considered to be a true representation of all motoring offences resulting in FPNs and other disposals, issued by MPS.

In 2017 the Home Office widened the scope of the collection for motoring offences to include cases where a driver retraining course, such as a speed awareness course, was attended by the individual, as well as cases where an individual faced court action. However, information on the outcome of those summoned to court is not provided and therefore data do not contain the number of individuals prosecuted for motoring offences[footnote 5]. A full time-series back to 2011 was published.

Since PentiP is an administrative dataset used by police forces, data for previous years can be amended as case details are updated. Furthermore, there is a cleansing process where some outcomes (particularly cancelled FPNs) are removed from the system after 6 months. During the COVID pandemic several forces reported suffering staff shortages and a backlog in cases that required finalising. As such, the number of motoring offences that are currently recorded as having an outcome of ‘incomplete’ (i.e. not assigned an outcome) is higher than pre-pandemic levels. But these cases only comprise a small proportion of all motoring offences (0.3%, or 11,110 cases in 2021, 0.2% or 5,671 cases in 2020 compared with 0.1% or 3,734 cases in 2019). It is expected that the count and outcomes of some motoring offences will be updated between publications.

This section contains data on the outcomes for motoring offences (as recorded on the PentiP system) for the territorial Police Force Areas (PFAs) in England and Wales on a calendar-year basis. Data are broken down by the number of motoring offences:

- that resulted in an FPN (endorsable and non-endorsable)

- where the driver attended a driver retraining course

- those which resulted in court action

- cancelled FPNs

The data also contain information on the types of motoring offences which led to these outcomes, whether or not the offence was camera detected, and whether or not a fine was paid (where the offence resulted in an FPN). For the first time, information on the month in which a motoring offence occurred has also been provided. These data are only available for 2020 onwards and can be found in Table FPN_02b.

The Home Office is aware that not all forces will exclusively use the PentiP system to record motoring offences. For example, several police forces including Durham, North Wales, South Wales, Gwent, North Yorkshire, Nottinghamshire, and Derbyshire do not record all outcomes of motoring offences on the PentiP system. Therefore, it is likely that the data published is not a complete record of all motoring offences that occur in England and Wales and is potentially an undercount.

The data does not contain offences for driving under the influence, or dangerous driving. Statistics on drink and drug driving can be found in the ‘Road Accident and Safety Statistics’ published by the Department for Transport. Dangerous driving is a notifiable offence and is therefore included in the ONS ‘Crime in England and Wales’ statistics.

Data on FPNs and other outcomes for motoring offences in England and Wales are presented in the FPN and other outcomes data tables.

5.2 Trends in FPNs and other outcomes of motoring offences

Excluding cancelled cases[footnote 6] (527,021 cases), the PentiP system recorded[footnote 7] 2.8 million motoring offences in 2021, which resulted in an FPN or another outcome, an increase of 17.2% compared with the previous year, and a 5.1% increase on 2019 (pre-pandemic levels). Specifically, in 2021:

- 921,777 cases resulted in the driver receiving an endorsable FPN (33%)

- 135,238 cases resulted in a non-endorsable FPN (5%)

- an individual attended a driver retraining course in 1,312,195 cases (47%)

- 410,579 cases resulted in court action (15%)

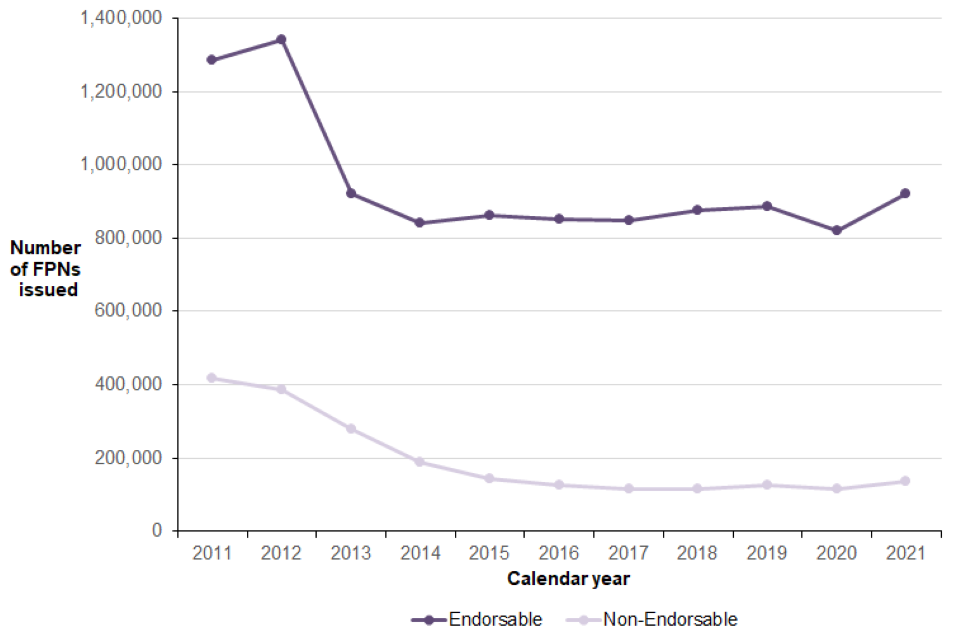

The number of endorsable FPNs issued remained fairly stable between 2014 and 2019 but following a decline in 2020 (to 820,383 during the pandemic) the data showed an increase in 2021 (to 921,777) similar to 2013 levels (921,447). The number of non-endorsable FPNs had fallen year-on-year from 2011 to 2017 but has been increasing since 2018, with the exception of a fall in 2020 likely due to the pandemic. In the latest year the number began to increase again from 126,592 in 2019 and 115,097 in 2020 to 135,238 in 2021 (Figure 5.1).

Figure 5.1: Number of motoring offences resulting in an endorsable or non-endorsable FPN, England and Wales, 2011 to 2021

Source: Table FPN_01, Home Office

Notes:

- Excludes FPNs which were subsequently cancelled.

- Excludes motoring offences which were dealt with via other outcomes such as cases where the individual attended a driver retraining course or faced court action.

- Excludes British Transport Police.

5.3 FPNs and other outcomes by offence type

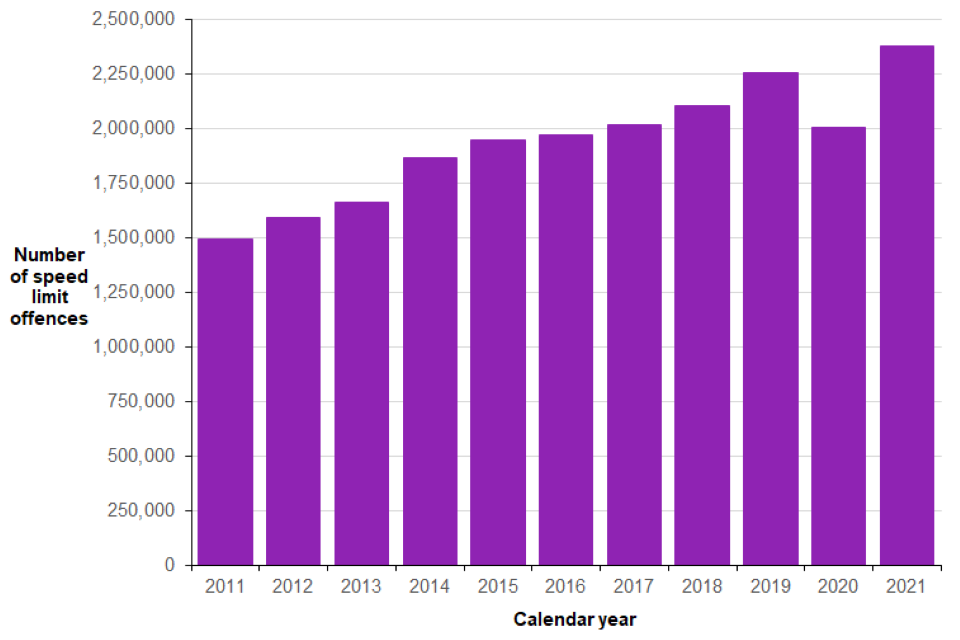

Over four-fifths (86%) of the motoring offences recorded on PentiP were for speed limit offences (2,378,373), up 19% on the previous year (when there were 2,006,382 issued) and 6% on 2019 (where there were 2,253,948 issued in the year prior to the pandemic). Other than a decline in 2020, likely due to the pandemic, the number of speed limit offences has increased in every year since 2011 (Figure 5.2).

Figure 5.2: Number of speed limit offences recorded on the PentiP system, England and Wales, 2011 to 2021

Source: Table FPN_02, Home Office

Notes:

- Excludes FPNs which were subsequently cancelled.

- Includes cases where the individual attended a driver retraining course or faced court action.

- Excludes British Transport Police.

Following the reported reduction in traffic volumes due to the pandemic in 2020, the majority of offences have shown an increase in detection in 2021. Careless driving offences (excluding the use of a handheld mobile phone while driving) saw one of the largest percentage increases, up by 39% in 2021 compared with the previous year (from 30,183 to 42,061), and up 71% on 2019 (pre-pandemic). This is the fourth consecutive increase for this offence since 2017.

Table 5.1: Number of motoring offences resulting in fixed penalty notices, driver retraining, or court action by offence type, England and Wales, 2019 to 2021

| Offence Description | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Speed limit offences | 2,253,948 | 2,006,382 | 2,378,373 |

| Licence, insurance and record-keeping offences | 102,239 | 114,453 | 111,397 |

| Neglect of traffic signs and directions and of pedestrian rights | 92,819 | 68,524 | 79,088 |

| Vehicle test and condition offences | 51,892 | 41,022 | 55,413 |

| Seat belt offences | 39,745 | 48,189 | 50,511 |

| Obstruction, waiting and parking offences | 32,140 | 24,177 | 18,307 |

| Use of handheld mobile phone while driving | 28,321 | 17,873 | 19,655 |

| Careless driving (excluding use of handheld mobile phone while driving) | 24,621 | 30,183 | 42,061 |

| Work record and employment offences | 4,961 | 3,182 | 3,319 |

| Other offences | 7,443 | 9,895 | 13,046 |

| Lighting and noise offences | 7,183 | 7,797 | 8,012 |

| Miscellaneous motoring offences (excluding seat belt offences) | 429 | 396 | 555 |

| Operator’s licence offences | 17 | 28 | 52 |

| Total | 2,645,758 | 2,372,101 | 2,779,789 |

Source: Table FPN_02, Home Office

Notes:

- Excludes FPNs which were subsequently cancelled.

- Includes offences were an FPN was issued or the individual attended driver retraining or court action.

- Excludes British Transport Police.

- The ‘other offences’ offence grouping includes load offences and offences peculiar to motor cycles.

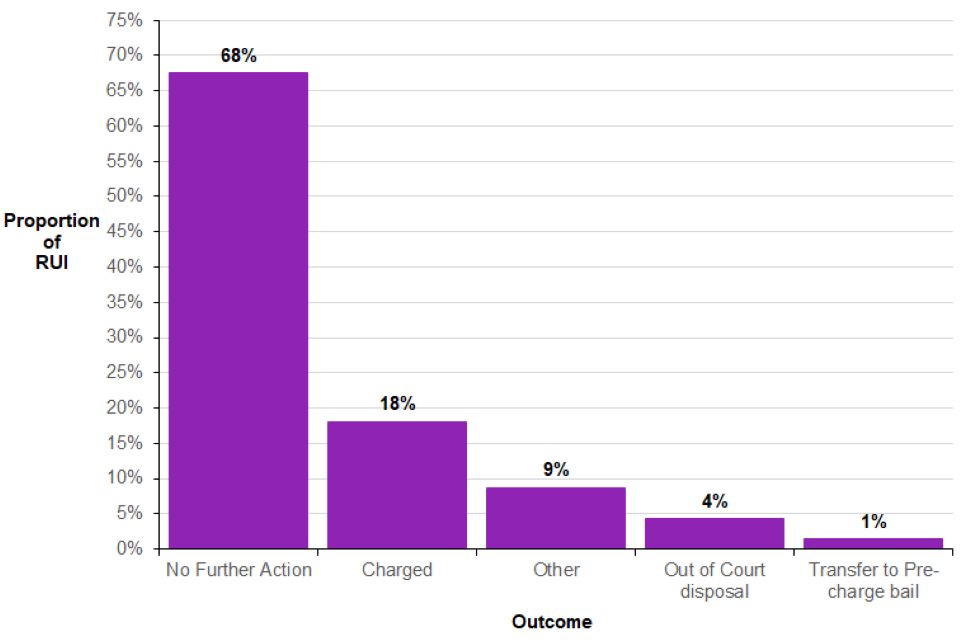

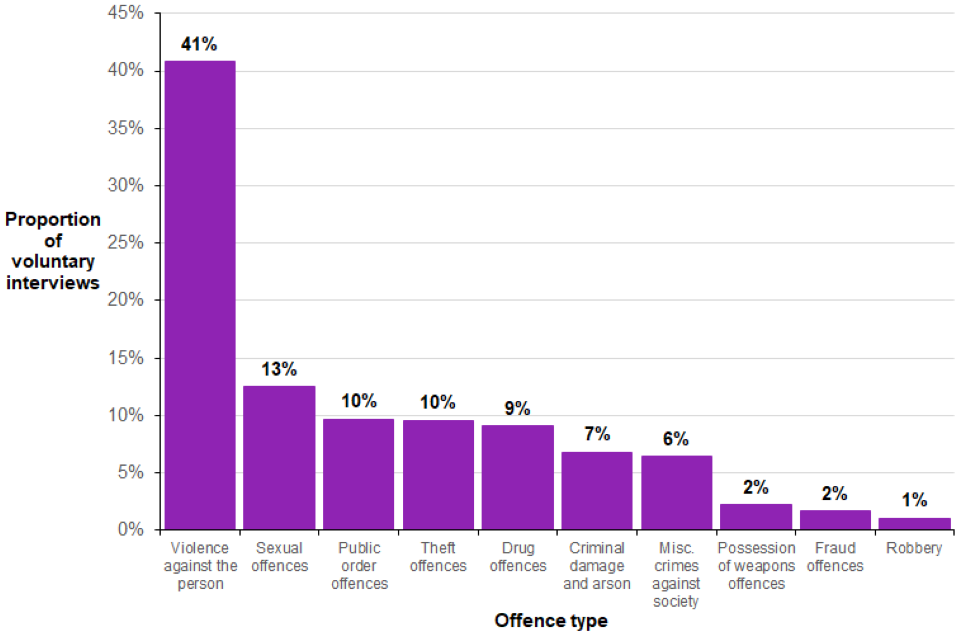

Use of a handheld mobile phone offences increased by 10% from 17,873 offences in 2020 to 19,655 in 2021. This is the first increase in the past decade following a year-on-year decline since 2011. However, the volume of this type of offence is 31% lower than pre-pandemic levels (28,321 offences in 2019) and is therefore likely to reflect traffic volumes returning to normal after a decrease in 2020 during the pandemic. The fall in this offence type compared with pre-pandemic levels may also reflect a change in driver behaviour, as shown by the data collected by the Office for National Statistics and published by the Department for Transport on self-reported mobile use while driving. Statistics for the year ending March 2020 showed that a large proportion of drivers who reported using a mobile phone whilst driving did so via Bluetooth, Voice command or a dashboard holder