The Strategic Defence Review 2025 - Making Britain Safer: secure at home, strong abroad

Updated 8 July 2025

Prime Minister’s Introduction

My first duty as Prime Minister is to keep the British people safe. That is why national security is the foundation of this Government’s Plan for Change. In this new era for defence and security, when Russia is waging war on our continent and probing our defences at home, we must meet the danger head on. We must recognise the very nature of warfare is being transformed on the battlefields of Ukraine and adapt our armed forces and our industry to lead this innovation. And we must understand that global instability affects economic security too, driving down growth and driving up the cost of living for working families here at home.

That’s why, in one of my first acts as Prime Minister, I launched this Strategic Defence Review, setting the Reviewers the formidable challenge of examining how our nation should meet this moment. The fundamental truth is clear: a step-change in the threats we face demands a step-change in British defence to meet them. We will never gamble with our national security. So I have already acted, announcing the largest sustained increase in defence spending since the Cold War. We are delivering our commitment to spend 2.5% of GDP on defence, accelerating it to 2027, and we have set the ambition to reach 3% in the next Parliament, subject to economic and fiscal conditions. This investment will end the hollowing out of our armed forces and enable the UK to step up, to lead in NATO, and take greater responsibility for our collective self-defence.

But our response cannot be confined to increasing defence spending. We also need to see the biggest shift in mindset in my lifetime: to put security and defence front and centre—to make it the fundamental organising principle of government.

Our experience of the pandemic exposed the vulnerabilities of relying on international just-in-time supply chains and required a whole-of-society response. In that spirit, we must drive a new partnership with industry and a radical reform of procurement, creating jobs, wealth, and opportunity in every corner of our country—this is the ‘defence dividend’ which we are determined to seize. It must drive innovation at a wartime pace, making the UK the leading edge of innovation in NATO and equipping our forces with the full range of conventional and technological capabilities. And it must foster a collective national endeavour through which the state, business, and society unite in pursuit of the security of the nation and the prosperity of its people.

This landmark Strategic Defence Review will help to make this a reality. I am very grateful to Lord Robertson of Port Ellen, General Sir Richard Barrons, and Dr Fiona Hill for all their work to lead it. This Government will now drive a national effort to deliver it.

The Rt Hon Sir Keir Starmer MP

Foreword from the Secretary of State

The world has changed. The threats we now face are more serious and less predictable than at any time since the Cold War, including war in Europe, growing Russian aggression, new nuclear risks, and daily cyber-attacks at home.

Our adversaries are working more in alliance with one another, while technology is changing how war is fought. Drones now kill more people than traditional artillery in the war in Ukraine, and whoever gets new technology into the hands of their Armed Forces the quickest will win.

And since we began the Strategic Defence Review (SDR), the UK and our European allies have been challenged to step up on European security.

We are in a new era of threat, which demands a new era for UK Defence. This Review sets out a vision to make Britain safer, secure at home and strong abroad.

Delivering for Defence

Since the General Election less than a year ago, we have demonstrated that we are a Government dedicated to delivering for Defence.

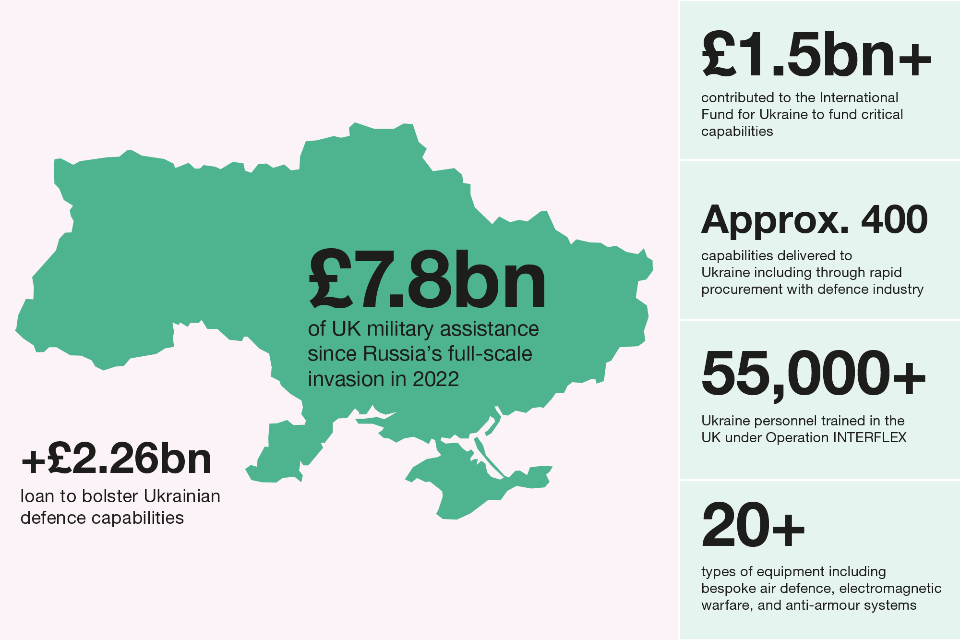

We have announced the largest sustained increase to defence spending since the end of the Cold War, stepped up support for Ukraine, awarded Service personnel the biggest pay rise in over 20 years, signed the historic Trinity House Agreement with Germany, bought back over 36,000 military homes to improve housing for forces families and save UK taxpayers billions, set new targets to tackle the recruitment crisis, made it easier for veterans to access essential care and support under the new VALOUR system, and passed through Parliament the Armed Forces Commissioner Bill to improve service life.

This first-of-its-kind Strategic Defence Review was launched by the Prime Minister within two weeks of the General Election. It has been externally led by George Robertson, Richard Barrons, and Fiona Hill, who have worked closely with the Ministry of Defence to harness the best expertise from inside and outside Government to produce the first root-and-branch review of UK Defence in 25 years. We are extremely grateful for their exceptional work.

During the review process, 1,700 individuals, political parties, and organisations submitted over 8,000 responses, 200 companies provided written contributions, over 150 senior experts took part in the Review and Challenge panels, and nearly 50 meetings took place between the Reviewers and our senior military figures. Members of the public also toured Defence sites as part of a ‘Citizens’ Panel’ to offer their views. These views are presented throughout this report.

I want to say a huge ‘thank you’ to everyone who has been involved. We set up the SDR in this unique way to break old thinking, inject fresh ideas, but importantly, to ensure the SDR serves as Britain’s Defence Review, not just the Government’s.

A New Era

The SDR signifies a landmark shift in our deterrence and defence: moving to warfighting readiness to deter threats and strengthen security in the Euro-Atlantic.

This will be achieved by the UK leading within NATO and taking on more responsibility for European security. That’s why our defence policy is ‘NATO First’. The UK’s strategic strength comes from our allies and, in a dangerous world, our unshakeable commitment to NATO means we will never fight alone. But ‘NATO First’ does not mean ‘NATO only’—and we remain committed to our allies and partners across the world, as our security is closely connected.

The SDR sets a path for the next decade and beyond to transform Defence. We will end the hollowing out of our Armed Forces and lead in a stronger, more lethal NATO. We will also draw lessons from the war in Ukraine, which has demonstrated that a nation’s Armed Forces are only as strong as the industry, innovators, and investors that stand behind them. And that technological innovation is vital to stay ahead of our adversaries.

Importantly, it sets a new vision for how our Armed Forces should be conceived—a combination of conventional and digital warfighters; the power of drones, AI, and autonomy complementing the ‘heavy metal’ of tanks and artillery; innovation and procurement measured in months, not years; the breaking down of barriers between individual Services, between the military and the private sector, and between the Armed Forces and society.

The SDR is the Plan for Change for Defence. It sets out the following new ambitions:

- ‘NATO First’—stepping up on European security by leading in NATO, with strengthened nuclear, new tech, and updated conventional capabilities.

- Move to warfighting readiness—establishing a more lethal ‘integrated force’ equipped for the future, and strengthened homeland defence.

- Engine for growth—driving jobs and prosperity through a new partnership with industry, radical procurement reforms, and backing UK businesses.

- UK innovation driven by lessons from Ukraine—harnessing drones, data, and digital warfare to make our Armed Forces stronger and safer.

- Whole-of-society approach—widening participation in national resilience and renewing the Nation’s contract with those who serve.

The Government—and our military chiefs—strongly welcome this vision and direction. This will set the strategic framework for UK Defence. To achieve this vision, the Government will Reform, Invest, and Act.

Reform

On Day 1 in Government, we launched the Defence Reform programme—the deepest defence reforms for 50 years. The SDR strongly endorses this programme of change and recognises that one cannot succeed without the other.

From 1 April 2025, we established a new Military Strategic Headquarters (MSHQ), set up a new National Armaments Director (NAD) to drive our defence industrial strategy, and gave new powers to the Chief of the Defence Staff (CDS) to command the Service Chiefs for the first time. We have also ended the Levene Reforms and have replaced ten budget holders with four new budget areas for tighter budget control.

These changes will strengthen Defence with stronger leadership, clearer accountability, faster delivery, less waste, and better value for money. We will unlock nearly £6bn of new savings over the course of this Parliament through efficiency and productivity savings, civilian workforce changes, and structural simplification.

Defence Reform is a Parliament-long programme. More improvements will come over the next 12 months—increasing integration, reducing duplication, and improving delivery. We will also introduce radical reforms to the defence procurement system, which the Public Accounts Committee and Defence Select Committee have both called ‘broken’.

Invest

On 25 February 2025, the Prime Minister announced the largest sustained increase to defence spending since the end of the Cold War—rising to 2.5% of GDP by 2027, and to 3% in the next Parliament when fiscal and economic conditions allow. We have already boosted defence by £5bn this year. Defence is now central to both our national security and our economic growth.

At the heart of this investment lies our total commitment to operate, sustain, and renew our nuclear deterrent which is deployed every minute of every day to protect our people, nation, and way of life. The UK’s nuclear deterrent is a truly national endeavour that has existed for over 60 years and sends the ultimate warning to anyone who seeks to do us harm.

A new £11bn ‘Invest’ annual budget has also been established under the NAD. This will fund kit for our front-line forces which is affordable and grows our UK industrial base. Our new partnership with industry and a decade of consistently rising defence spending will encourage more private finance to grow our world-leading scale-up and dual-use tech companies.

Act

This Government is endorsing the vision and accepting all 62 recommendations in the SDR, which will be implemented. In line with SDR findings, we are also taking further immediate action.

-

We will secure the future of our nuclear deterrent, by committing to £15bn investment in the sovereign warhead programme this Parliament and supporting over 9,000 jobs.

- We will create a ‘New Hybrid Navy’, building the Dreadnought and SSN-AUKUS submarines, cutting-edge warships and support ships, transforming our carriers, and introducing new autonomous vessels to patrol the North Atlantic and beyond.

-

We will create a British Army which is 10x more lethal to deter from the land, by combining more people and armoured capability with air defence, communications, AI, software, long-range weapons, and land drone swarms.

-

We will create a next-generation RAF, with F-35s, upgraded Typhoons, next-generation fast jets through the Global Combat Air Programme, and autonomous fighters to defend Britain’s skies and strike anywhere in the world.

-

We will protect the UK homeland, with up to £1bn new funding invested in homeland air and missile defence and creating a new CyberEM Command to defend Britain from daily attacks in the grey zone.

-

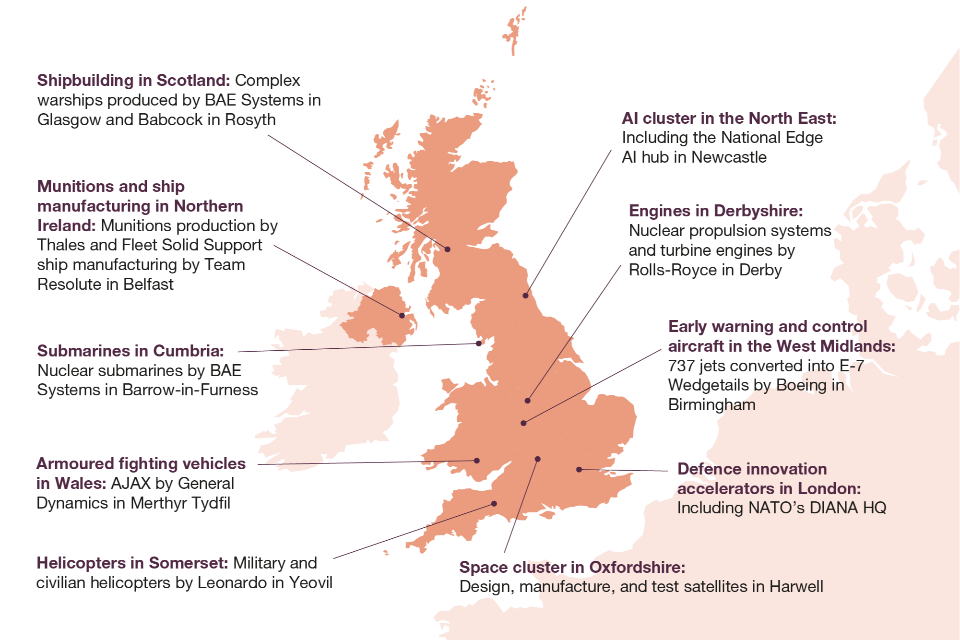

We will ensure Defence is an engine for growth across the UK, by investing £6bn in munitions this Parliament, including £1.5bn in an ‘always on’ pipeline for munitions and building at least six new energetics and munitions factories in the UK, generating over 1,000 jobs and boosting export potential.

- We will commit to continuous submarine production through investments in Barrow and Raynesway that will allow us to produce a submarine every 18 months. Through the AUKUS programme, this will allow us to grow our nuclear-powered attack submarine fleet to up to 12. This will reinforce our Continuous at Sea Deterrent (CASD) and position the UK to deliver the AUKUS partnership with the US and Australia.

- We will build up to 7,000 new long-range weapons in the UK to provide greater European deterrence and support around 800 jobs.

- We will invest in world-leading innovation in autonomous systems this Parliament to boost UK export potential. And we will invest more than £1bn to integrate our Armed Forces through a new Digital Targeting Web delivered in 2027.

-

We will provide leadership in NATO, by transforming our aircraft carriers to become the first European hybrid airwings—with fast jets, long-range weapons, and drones.

-

We will establish UK Defence Innovation with £400m to fund and grow UK-based companies.

-

We will create a new Defence Exports Office in the Ministry of Defence to drive exports to our allies and growth at home.

- We will deliver a generational renewal of military accommodation, with at least £7bn of funding in this Parliament—including over £1.5bn in new investment for rapid work to fix the poor state of forces family housing.

Defence Investment Plan

We will develop a new Defence Investment Plan to deliver the SDR’s vision. We will ensure the Plan is deliverable and affordable, considers infrastructure alongside capabilities, enables flexibility to seize new technology opportunities, and maximises the benefits of defence spending to grow the UK economy. This will supersede the old-style Defence Equipment Plan.

This will deliver the best kit and technology into the hands of our front-line forces at speed and, importantly, invest in and grow the UK economy. The Defence Investment Plan will be completed in Autumn 2025.

The Rt Hon John Healey MP

Foreword from the Reviewers

When the Prime Minister and the Defence Secretary asked the three of us—a politician, a soldier, and a foreign policy expert—to lead, externally, the new Strategic Defence Review, the world was already in turmoil. Russia, a nuclear-armed state, had invaded and brutally occupied part of a neighbouring sovereign state. And in doing this it was supported by China, supplied with equipment from Iran and by troops from North Korea, deployed in Europe for the first time ever.

The sheer unpredictability of these and other global events, combined with the velocity of change in every area, has created alarming new threats and vulnerabilities for our country—and a dangerous complexity in the world.

If anything, the geopolitical context has worsened since we started. The challenge to the free world has intensified through so-called ‘great power’ competition and a collapse of the post-Second World War consensus. The certainties of the international order we have accepted for so long are now being questioned—and not only by authoritarians. The international chessboard has been tipped over.

In a world where the impossible today is becoming the inevitable of tomorrow, there can be no complacency about defending our country. Defence can no longer be seen as contracted out only to our Armed Forces, good and brave as they are. With multiple threats and challenges facing us now, and in the future, a whole-of-society approach is essential. Everyone has a role to play and a national conversation on how we do it is required.

We, the Reviewers, were initially asked by the Prime Minister and the Defence Secretary to ‘determine the roles, capabilities and reforms required to meet the challenges, threats and opportunities of the twenty-first century’. Over the past eleven months that is what we have endeavoured to do. This report, then, is the product of the intensive scrutiny of every aspect of Defence and it has involved one of the deepest and most thorough consultations on the subject ever.

It is a truly transformational and genuinely strategic review. It is designed to bolster deterrence by rebuilding our warfighting readiness. As the old saying goes, ‘If you want peace, prepare for war’. Our independent nuclear deterrent, one of the determining factors in the minds of our adversaries, is committed to NATO and as such adds to the security of the whole Euro-Atlantic community. It is being renewed.

We are proposing a combination of reinforced homeland resilience and a new model Integrated Force, putting NATO first. We therefore ensure that the British people will be safer at home and more influential abroad. However, we will never, in the future, expect to fight a major, ‘peer’ military power alone. NATO is the bedrock of our defence, with 31 other countries committed to collective security. A billion people in the Euro-Atlantic area sleep easily each night, protected by the mutual defence clause, Article V of the North Atlantic Treaty. We must work hard to make sure this remains the case, bolstering the Alliance through our approach and our daily efforts.

By ruthlessly examining every aspect of Defence, the Review challenges the very idea of ‘business as usual’, just as our enemies too have developed and modernised. It proposes a new partnership with industry, led by a powerful new National Armaments Director, to ensure our forces have the equipment they need—on time and on budget. Taxpayers have a right to be confident that the money they pay to keep them safe is used wisely and appropriately.

The Review will boost the Reserves, re-invigorate training, tackle the troop accommodation problems, eradicate ingrained bureaucracy, and change the culture in Defence. Learning from the cutting-edge developments in use in Ukraine, the fundamental lesson for today is that with technology developing faster than at any time in human history, our own forces, and the whole of Defence, must innovate at wartime pace. The hollowing out of our forces—which was the hallmark of taking a big ‘peace dividend’ after the end of the Cold War—will, over time, be reversed.

We were asked to conduct our Review within the budgetary context of a transition to 2.5% of GDP.[footnote 1] We acknowledge with relief that this will apply from 2027 and not later. What is also significant is the ambition to spend 3% of GDP on defence in the 2030s if economic and fiscal conditions allow. Given that the present 2.3% (which includes significant investment in the nuclear deterrent, the nation’s top defence priority, and other core commitments) might have forced savings in essential capabilities, this is good news.

We are confident that the transformation we propose for the harder world we now live in is affordable over ten years, given these promised new resources. However, as we live in such turbulent times it may be necessary to go faster. The plan we have put forward can be accelerated for either greater assurance or for mobilisation of Defence in a crisis.

We have conducted this Review with, and not to, the Ministry of Defence and we have worked closely with the Prime Minister and the Defence Secretary. There should therefore be no surprises—even if we did not seek consensus or shy away from being bold and radical.

The Review has benefited from the endeavours and expertise of our fellow reviewers, the ‘Defence Review Team 6’: Grace Cassy; Edward Dinsmore; Jean-Christophe Gray; Angus Lapsley; Robin Marshall; and Rt Hon Sir Jeremy Quin. We have also had all along heroic assistance from a dedicated, talented, multi-departmental team—drawn from within the MOD, the Armed Forces, other Government departments, and a cohort of international military liaison officers and civilian officials—to whom we are profoundly grateful.

Lord Robertson of Port Ellen KT GCMG

General Sir Richard Barrons KCB CBE

Dr Fiona Hill CMG

1. Introduction and Overview

A generational challenge demands a generational response. For the first time since the end of the Cold War, the UK faces multiple, direct threats to its security, prosperity, and democratic values. The world itself is beset by volatility and deep uncertainty.

In response, the UK, with its allies—especially those in NATO—must once again be ready to deal with the most demanding of circumstances: deterring and preventing a full-scale war by being ready to fight and win. Until recently, such a war against another country with advanced military forces was unthinkable. It would likely be high-intensity, protracted, and costly in every way. Moving to warfighting readiness in this new era is essential.

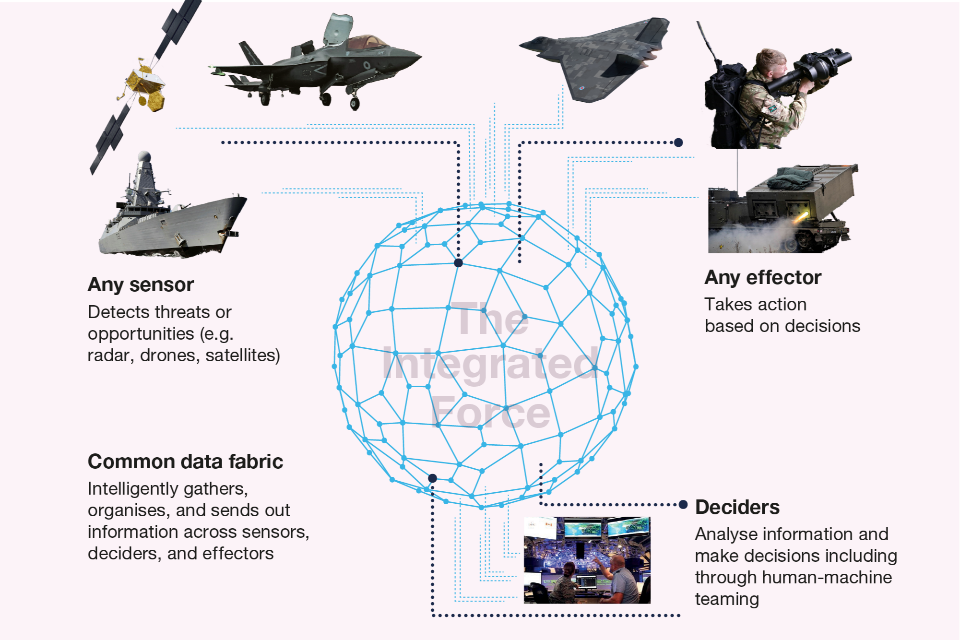

With rapid advances in technology driving the greatest change in how war is fought for more than a century, the UK must pivot to a new way of war. It must continually harness new technology and think differently about what conventional ‘military power’ is and how to generate it. In modern warfare, simple metrics such as the number of people and platforms deployed are outdated and inadequate. It is through dynamic networks of crewed, uncrewed, and autonomous assets and data flows that lethality[footnote 2] and military effect are now created, with military systems making decisions at machine-speed and acting flexibly across domains.

The UK’s Armed Forces must once again be able to endure in long campaigns through assured access to key capabilities—all underwritten by a thriving industry that is ready to scale and sustain innovation and production as required.

And in a decisive shift from the post-Cold War era, a renewed emphasis on home defence and resilience is also imperative, with ‘sub-threshold’ activities,[footnote 3] growing access to space and cyberspace, and unrelenting advances in weapons systems all making it easier for adversaries to cause the UK harm, even at distance.

Where previous reviews have more narrowly addressed the Armed Forces, this Strategic Defence Review (SDR) delivers the ‘root-and-branch’ review of UK Defence that was commissioned by the Prime Minister in July 2024 in response to this rapidly changing world. It outlines the deep reform needed ‘to ensure the United Kingdom is both secure at home and strong abroad—now and for the years to come’.[footnote 4]

Overseen by the Secretary of State for Defence, the SDR was unprecedented in being led by external Reviewers: Lord (George) Robertson; General Sir Richard Barrons; and Dr Fiona Hill. It has been conducted within the Terms of Reference set by the Government and latterly costed within an increased defence budget of 2.5% of GDP from April 2027 and 3% in the 2030s, subject to economic and fiscal conditions.[footnote 5] The Review process, including its extensive engagement with internal and external expertise, is set out in the Appendix.

In this report, we set out:

- Why UK Defence needs to change, considering the international and security context in the period to 2040 and the current state of Defence (Chapter 2).[footnote 6]

- What roles Defence should perform and where in the coming years (Chapter 3).

- How the Armed Forces should fight and how wider Defence should support that fight, with the transformation of UK warfighting delivered by an empowered and adaptive workforce (Chapter 4).

- Who Defence should fight alongside: the centrality of allies and partners with which the UK can build industrial power and common capabilities, and ultimately fight and win (Chapter 5); and the importance of a renewed connection with UK society to ensure resilience and strategic depth in the event of crisis or conflict (Chapter 6).

- The capabilities with which the Integrated Force should fight (Chapter 7), addressing the front-line elements and foundational enabling capabilities of UK Defence—creating a force fit for war in the 21st century through the new ten-year Defence Investment Plan.[footnote 7]

A new era of threat

This is an important moment for the UK and its allies (Chapter 2). Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 was a strategic inflection point. It irrefutably demonstrated the changing and dynamic nature of the threat, with state-on-state war returning to Europe, adversaries using nuclear rhetoric in an attempt to constrain decision-making, and the UK and its allies under daily attack beneath the threshold of war as part of intensifying international competition. The conflict has also shown the power of emerging technology to change where, how, and with what war is fought. Armed Forces that do not change at the same pace as technology quickly risk becoming obsolete.

Importantly, Ukraine is just one flashpoint of many amid growing global instability and a volatility that is exemplified by the remarkable rate of change in the international landscape since this Review was launched in 2024. Most immediately relevant at the time of writing, this includes: negotiations for a ceasefire in the Ukraine-Russia war; the possible deployment of a ‘reassurance force’ to Ukraine in the event of a ceasefire; and major questions about the future of European security that inevitably follow the United States’ change in security priorities, as its focus turns to the Indo-Pacific and the protection of its homeland.[footnote 8] Fundamentally, the UK’s longstanding assumptions about global power balances and structures are no longer certain.

UK Armed Forces have begun the necessary process of change in response to this new reality. But progress has not been fast or radical enough. The Armed Forces remain shaped by the risks and demands of the post-Cold War era—optimised for conflicts primarily fought against non-state actors on Europe’s periphery and beyond. Although substantial and demanding, these operations also did not require ‘whole-of-society’ preparations for war, home defence, resilience, and industrial mobilisation.

A new era for UK Defence

In response to this strategic context, our Review articulates a new era for Defence. Building on changes already underway, our vision is that, by 2035, UK Defence will be:

A leading tech-enabled defence power, with an Integrated Force that deters, fights, and wins through constant innovation at wartime pace.

Defence must be able to fulfil its fundamental role: to deter threats to the UK and its allies by being ready for war, and to provide the definitive insurance policy should deterrence fail. This should be pursued as part of a whole-of-society approach to deterrence and defence under which Defence combines its strengths with those of wider Government, industry, and society.

Roles for UK Defence

The starting point for this Review is the Government’s ‘NATO First’ policy (Chapter 3). There is an unequivocal need for the UK to redouble its efforts within the Alliance and to step up its contribution to Euro-Atlantic security more broadly—particularly as Russian aggression across Europe grows and as the United States of America adapts its regional priorities. In a shift in approach, the Alliance should be mainstreamed in how Defence plans, thinks, and acts.

‘NATO First’ does not mean ‘NATO only’. The UK should take a pragmatic approach to bolstering collective security in the Euro-Atlantic through stronger bilateral and minilateral partnerships.[footnote 9] The Alliance itself recognises the importance of working with partners outside the region—reflecting the connection between Euro-Atlantic security and that of other regions such as the Middle East and Indo-Pacific. Defence must also be able to pursue and protect the UK’s significant interests, commitments, and responsibilities outside the region, including the defence of its sovereign territory.

Nevertheless, the fundamental importance of meeting Alliance commitments and shaping deterrence in the Euro-Atlantic every day is reflected in the enduring and mutually reinforcing roles that Defence must fulfil. The three core Defence roles are:

- Role 1: Defend, protect, and enhance the resilience of the UK, its Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

- Role 2: Deter and defend in the Euro-Atlantic.

- Role 3: Shape the global security environment.

The two enabling roles for Defence are to:

- Develop a thriving, resilient defence innovation and industrial base.

- Contribute to national cohesion and preparedness.

Transforming UK warfighting

To meet the threats of today and tomorrow, Defence must fundamentally change how it fights and how it supports that fight: rapidly increasing the Armed Forces’ lethality and enhancing their ability to fight at the leading edge of technology (Chapter 4). Drawing on lessons from the war in Ukraine and enabled by organisational change under Defence Reform, the whole of Defence (the Armed Forces and Department of State together) should be driven by the logic of the innovation cycle—able to find, buy, and use innovation, pulling it through from ideas to front line at speed.

At the heart of this transformation are three fundamental changes in approach. Defence must be:

- Integrated by design. For the Armed Forces to be more lethal than the sum of their parts, they must complete the journey from ‘joint’ to ‘integrated’: designed and directed as one force under the authority of the Chief of the Defence Staff, and delivered according to this design by the single Services and Strategic Command. Under this new model, there is no fixed force design to be delivered by a specified date. The design and capabilities of the Integrated Force, and the way that wider Defence supports it, must continue to evolve as threats and technology do. The Integrated Force must be capable of operating in different configurations: as part of NATO Component Commands by design; in coalition; and as a sovereign force. To deliver a step-change in lethality, the Integrated Force must be underpinned by a common digital foundation and shared data. Delivery should be a top priority. A single ‘digital mission’—to deliver a digital ‘targeting web’[footnote 10] in 2027—should enable Defence to succeed where it has previously failed, as should the creation of an expert Digital Warfighters group that can be deployed alongside front-line personnel (Chapter 4.1).

-

Innovation-led. Today, much of the best innovation is found in the private sector, while the increasing prevalence of dual-use technologies[footnote 11] has widened the net of potential suppliers that can contribute to Defence outcomes. Defence must embrace its role in seeding innovation and growth, rapidly adopting new technology to keep the Integrated Force at the forefront of warfare. In particular, Defence should build relationships with the investors behind the innovators. External expertise should be systematically accessed through a new Defence Investors’ Advisory Group whose membership includes venture capital and private equity investors, while private finance should be crowded in under new funding models. To set itself up for success internally, Defence should reorganise existing structures to create two distinct organisations under the National Armaments Director:

- A Defence Research and Evaluation organisation,[footnote 12] focused on enabling external early-stage research and providing a gateway to academia.

- The new UK Defence Innovation (UKDI) organisation,[footnote 13] focused on harnessing commercial innovation, including for dual-use technologies. UKDI will have a ringfenced annual budget of at least £400m (Chapter 4.2).

-

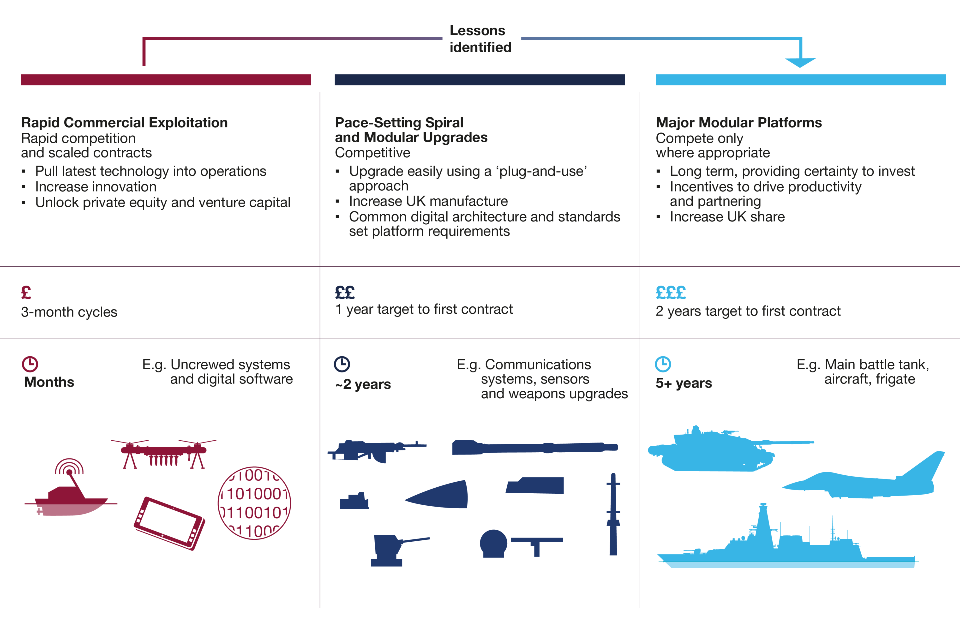

Industry-backed. To develop a thriving, resilient innovation and industrial base that can scale in support of the Integrated Force, Defence must create a new partnership with industry. Under the forthcoming Defence Industrial Strategy and the leadership of the National Armaments Director, this involves overhauling acquisition processes from top to bottom: engaging industry early in procurement processes on desired outcomes; ensuring that suppliers are rewarded for productivity and for taking risks; and reducing the burden on potential suppliers from startups to primes. At the heart of this partnership should be a new, segmented approach to procurement:[footnote 14]

- Major modular platforms (contracting within two years).

- Pace-setting spiral and modular upgrades (contracting within a year).

- Rapid commercial exploitation (contracting within three months), with at least 10% of the MOD’s equipment procurement budget spent on novel technologies each year.

- Exports and international capability partnerships[footnote 15] should also be mainstreamed into acquisition processes from the outset, with responsibility for defence exports returned to the Ministry of Defence (MOD) and a new framework for building and sustaining government-to-government relationships. Investment decisions should consider associated costs to ensure they are genuinely affordable—for example, through-life upgrades, acquisition and support, and attendant changes to infrastructure (Chapter 4.2).

By more purposefully using its market power and by prioritising UK-based business, Defence should also strive to deliver for the UK economy while delivering for the warfighter. Defence has significant untapped potential to be a new engine for growth at the heart of the UK’s economic strategy. Radical root-and-branch reform of defence procurement—combined with substantial investment in innovation, novel technology, advanced manufacturing, and skills—would grow the productive capacity of the UK economy. Defence should aim high, measuring success in the number and scale of defence and dual-use technology companies in the UK. Success will also see significant improvement in Defence productivity, competitiveness, exports, and value for money, supported by the new Defence Reform and Efficiency Plan (Chapter 4.2). [footnote 16]

This transformation of UK Defence must ultimately be delivered by its people (Chapter 4.3), empowered through changes in culture and ‘people’ policies that remove red tape and eradicate behaviour that is unacceptable in the workplace. Targeted intervention is needed to tackle Defence’s workforce crisis—improving recruitment through faster, more flexible options such as military ‘gap years’, and improving retention through the MOD’s planned ‘flexible working’ initiative and prioritised investment this Parliament in accommodation that falls well short of the standards required.

The focus must be on maximising the effectiveness of the ‘whole force’:[footnote 17]

- To fulfil the roles set out in this Review, there is no scope for reducing the number of highly trained and equipped Regulars across all three Services, even as the forces move to a much greater emphasis on autonomy. Overall, we envisage an increase in the total number of Regular personnel when funding allows. This includes a small uplift in Army Regulars as a priority.

- Increasing the number of Active Reserves by 20% when funding allows (most likely in the 2030s) and reinvigorating the relationship with the Strategic Reserves.

- Reshaping the Civil Service workforce with an emphasis on performance, productivity, and skills, reducing costs by at least 10% by 2030.

- Releasing military personnel in back-office functions to front-line roles and automating 20% of HR, Finance, and Commercial functions by July 2028. This should be a minimum first step.

- Reforming training and education so that it is much more adaptive to operational lessons, ensures managed risks can be taken in military training, and creates greater capacity and flexibility through developing a single virtual environment. Civilian qualifications and education provision should be used where possible to increase efficiency and to reduce the barriers between Defence, industry, and wider society.

Strengthening deterrence through alliances and partnerships

The UK must bolster collective security and create strategic depth by actively investing in its relationships (Chapter 5). Finite resources mean the UK cannot be everything to everyone. It must prioritise its approach, informed by the roles outlined in Chapter 3 and using the full range of tools available to it.

Bilateral agreements and capability partnerships—with the United States and European NATO Allies—offer a powerful tool through which to strengthen relationships and Euro-Atlantic stability. The same is true of minilateral activity, including through the Joint Expeditionary Force, E3, and E5 formats,[footnote 18] supplemented by implementation of the UK-EU Security and Defence Partnership. AUKUS and the Global Combat Air Programme must be developed as exemplars of capability collaboration and a powerful signal of the UK’s ambition to bring partners from different geographic regions closer together in support of collective security. Doubling down on support to Ukraine in pursuit of a durable political settlement is critical, as is learning from its extraordinary experience in land warfare, drone, and hybrid conflict.

Home defence and resilience: a whole-of-society approach

A renewed focus on home defence and resilience is vital to modern deterrence, ensuring continuity in national life in a crisis (Chapter 6). Reconnecting Defence with society should be the starting point, as part of a national conversation led by the Government on defence and security. This can be achieved in part through expanding Cadet Forces by 30% by 2030 (with an ambition to reach 250,000 in the longer term) and working with the Department for Education to develop understanding of the Armed Forces among young people in schools.

A more substantive body of work is necessary to ensure the security and resilience of critical national infrastructure (CNI) and the essential services it delivers. The MOD should explore, with wider Government, a ‘new deal’ for the protection and defence of CNI that is rooted in partnership with private-sector and allied operators. To support this, the Royal Navy should play a new leading and coordinating role in securing undersea pipelines, cables, and maritime traffic.

The Government must also be able to achieve a sustainable and effective transition to war if necessary. A new Defence Readiness Bill should provide the Government with powers in reserve to mobilise Reserves and industry should crisis escalate into conflict. It should also facilitate external scrutiny of UK warfighting readiness.

The Integrated Force: a force fit for war in the 21st century

The essential task is to transform the Armed Forces, restore their readiness to fight, and reverse the ‘hollowing out’ of foundational capabilities without which they cannot endure in protracted, high-intensity conflict (Chapter 7).

The UK must continue to dedicate its independent nuclear deterrent to NATO (Chapter 7.1), adapting its alliances, industrial base, and military capabilities to ensure it can continue to deter the most extreme threats. The UK will need a full spectrum of options to manage escalation as part of NATO, delivered by its nuclear and conventional forces in combination. Defence should commence discussions with the United States and NATO on the potential benefits and feasibility of enhanced UK participation in NATO’s nuclear mission. Further investment in conventional deep precision strike and Integrated Air and Missile Defence would increase options for deterring and responding to high-impact threats.

Senior Ministers must drive efforts to sustain the nuclear deterrent as Defence’s top priority and as a ‘National Endeavour’. The programme to replace the sovereign warhead is critical and will require significant investment this Parliament. Confirming the intended numbers of SSN attack submarines would provide clarity on the required build capacity and tempo for all nuclear-powered submarines. To secure the long-term future of the nuclear deterrent, the Government should start work in this Parliament to define the requirement for the successor to the Dreadnought class submarine.

An immediate priority for force transformation should be a shift towards greater use of autonomy and Artificial Intelligence within the UK’s conventional forces (Chapter 7). As in Ukraine, this would provide greater accuracy, lethality, and cheaper capabilities—changing the economics of Defence. This shift towards AI and autonomy should exploit the parallel development of a common digital foundation, a protected Defence AI Investment Fund, and an initial operating capability for a new Defence Uncrewed Systems Centre established by February 2026.

The Armed Forces should accelerate their transition to a ‘high-low’ mix of equipment—for example, through:

- The Royal Navy’s ‘Atlantic Bastion’ concept for securing the North Atlantic for the UK and NATO and its plans for hybrid carrier airwings (Chapter 7.2).

- The Army’s ‘Recce-Strike’ model for land fighting power, aiming to deliver a ten-fold increase in lethality.[footnote 19] This new model should underpin the transformation of the two divisions and Corps Headquarters committed to NATO’s Strategic Reserves Corps (Chapter 7.3).

- The RAF’s development of the Future Combat Air System—a sixth-generation, crewed jet operating with autonomous collaborative platforms (Chapter 7.4).

With the Integrated Force fighting as one across all five domains, greater attention must be given to the space and cyber and electromagnetic (CyberEM) domains:[footnote 20]

- Assured access to operate in, from, and through space underpins UK security and prosperity. The MOD should invest in the resilience of military space systems, with a focus on space control, decision advantage, and capabilities that support ‘Understand’ and ‘Strike’ functions. A reinvigorated Cabinet sub-Committee should set the UK’s strategic approach to space, maximising synergies between the UK civil space sector and clear military needs (Chapter 7.5).

- The CyberEM domain is similarly essential to securing and operating in all other domains and is fundamental to the digital targeting web. Hardening critical Defence functions to cyber-attack is crucial. Defence must move to a more proactive footing in this domain. A new CyberEM Command—established within Strategic Command—should emulate Space Command in ensuring domain coherence, rather than directing execution. An initial operating capability should be established by the end of 2025 (Chapter 7.6).

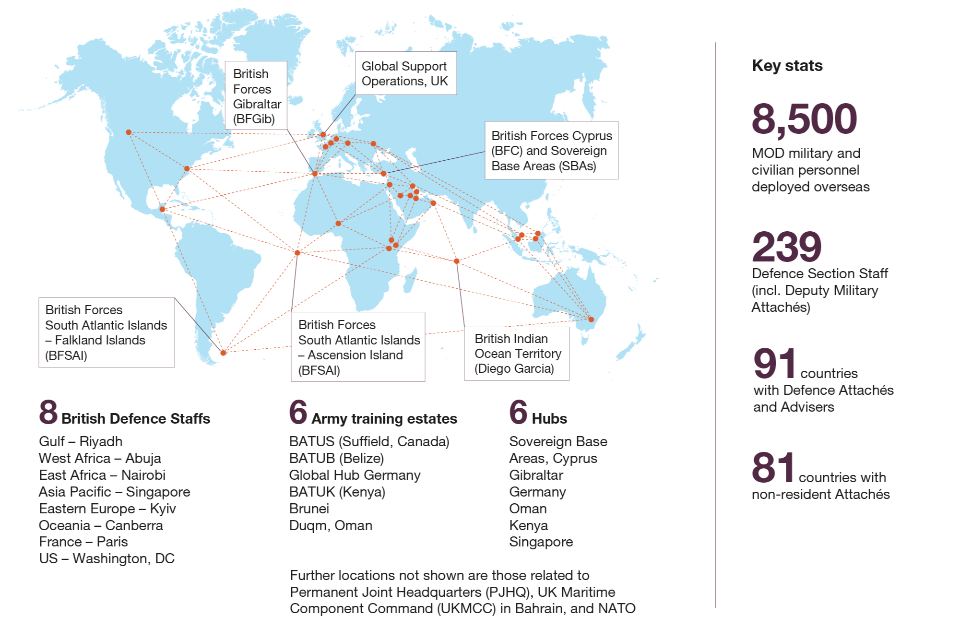

Under Defence Reform, Strategic Command will be responsible for delivering, at the direction of the new Military Strategic Headquarters, many of the joint enablers and specialist capabilities for the Integrated Force—from Defence Intelligence to the Integrated Global Defence Network, Defence Medical Services, and Special Forces and Special Operations Forces. UK Special Forces—the ‘tip of the spear’—represent a working model of the Integrated Force, leading the way in innovation of new technologies and systems across all domains. Defence must continue to enhance its Special Forces, ensuring UK sovereign choice by maintaining this strategic capability at the very highest level.

Where some past reviews have focused on front-line equipment at the expense of foundational capabilities, we have sought to redress this balance. We recommend a focus on:

- Empowering Defence Intelligence as the functional leader of all defence intelligence organisations—pursuing common priorities and standards, underpinned by a new Defence Intelligence charter, and, in time, fully interoperable with the UK Intelligence Community (Chapter 7.9).

- Rebuilding Defence Medical Services, cohering disparate defence medical resources and initiating a sprint review with the Department of Health and Social Care to ensure personnel needs can be met in peacetime and in war (Chapter 7.10).

- Restoring the Strategic Base[footnote 21] from which the Armed Forces deploy: delivering a Defence Infrastructure Recapitalisation Plan by February 2026 to address years of underfunding and identify ways to maximise the value of the estate as a national asset (Chapter 7.11).

- Targeted investment in joint support enablers and munitions. Defence should maintain an ‘always on’ munitions capability, laying the industrial foundations for production to be scaled up at speed if needed. This should be complemented by the further development of novel directed energy weapons (Chapter 7).

The transformation imperative

Prudent sequencing is needed to ensure the Armed Forces have what they need, when they need it, within the resources available and to achieve the best possible return on investment. This includes being ready to accelerate efforts to transform the Armed Forces and restore readiness should conditions deteriorate further, or to mobilise UK Defence rapidly in the event of a crisis. In this new and uncertain era, nobody should be surprised if it became necessary to transform further and faster.

There is no reason to delay in changing fundamentally how Defence works, however, leveraging Defence Reform—the ongoing programme of organisational and cultural change (Box 1)—as a driver for reform across the Department of State and the Armed Forces. Unlike other departments in Government, the MOD does not control the timetable for confrontation and conflict. ‘Events’ and the UK’s adversaries do. Bold and decisive action is needed. ‘Business as usual’ is not an option.

We are acutely aware that words such as ‘transformation’ have been used before in defence reviews but the intention has seldom been delivered. A key factor in success in the coming years will be Defence Reform. Where the SDR states what Defence must do in the next decade and beyond, Defence Reform will ultimately determine how, and how successfully, it is delivered. To support implementation, we have identified key interventions and deadlines to further catalyse progress where in the past it has been slow and lacked accountability. The MOD will necessarily take this work forward in creating detailed implementation plans—an essential part of the department taking ownership of the Review’s findings and recommendations.

Box 1: Defence Reform: setting Defence up for success

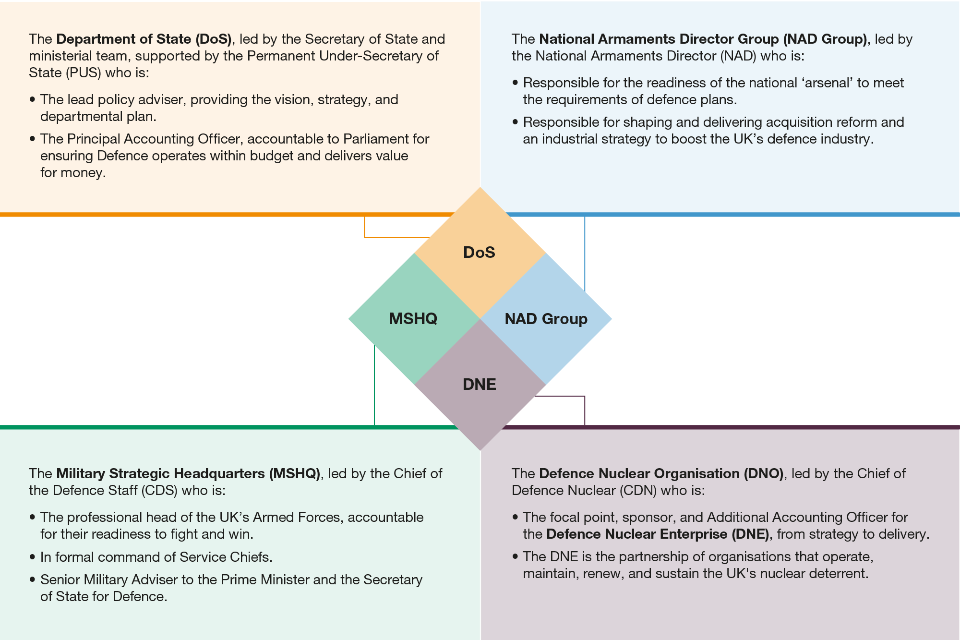

The purpose of Defence Reform is to establish robust and streamlined governance, clearer accountabilities, and faster decision-making processes across the Ministry of Defence and the Armed Forces. The starting point is the restructuring of Defence under four areas (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Responsibilities of senior officials and military personnel under Defence Reform

Diagram of the four components of a reformed UK Defence, their roles, and responsibilities: the Department of State; the National Armaments Director Group; the Military Strategic Headquarters; and the Defence Nuclear Enterprise.

We strongly endorse the organisational change launched by the Defence Secretary and pursued under Defence Reform. As it progresses, it should focus on:

- Supporting a ‘One Defence’ mindset through career management structures that reward behaviour and action accordingly, with NATO a primary consideration. More radical options to break down single Service siloes, such as joint promotion boards or central career management, should be explored.

- Delivering a step-change in the department’s financial and programme management. As the Principal Accounting Officer, the Permanent Under-Secretary must retain primary responsibility for financial planning and must be able to account for the department’s financial position, even as other senior leaders are given greater financial authority within their respective areas of responsibility. Further streamlining programme and project approvals might be achieved through full implementation of the industry-standard ‘three lines of defence’ model for risk assurance.[footnote 22] Incorporating HM Treasury and the Cabinet Office Commercial Function in this model offers the basis for an improved working relationship.

- Ensuring the role of the National Armaments Director is focused on engaging with industry and international partners to progress the Government’s defence industrial and exports agenda. This will require delegating authority for acquisition management and other elements of the work of the National Armaments Director Group.

- Supporting the continual adoption of new technologies, in particular Artificial Intelligence (AI), that will enable Defence to take leaps forward both in how it fights and the productivity with which it delivers. The MOD must engage in the implementation of the AI Opportunities Action Plan[footnote 23], led by the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology, wherever possible.

We have primarily taken our lead from, or worked with, the Defence Reform team on the most effective organisational structures for governance and delivery within Defence. However, in this report, we occasionally make suggestions on roles and responsibilities for consideration as the Defence Reform programme is developed further.

2. The Case for Transformation

The UK is entering a new era of threat and challenge. The world is more volatile and more uncertain than at any time in the past 30 years and it is changing at a remarkable pace.

The UK and its allies are once again directly threatened by other states with advanced military forces. The UK is already under daily attack, with aggressive acts—from espionage to cyber-attack and information manipulation—causing harm to society and the economy. State conflict has returned to Europe, with Russia demonstrating its willingness to use military force, inflict harm on civilians, and threaten the use of nuclear weapons to achieve its goals. More broadly, the West’s long-held military advantage is being eroded as other countries modernise and expand their armed forces at speed, while the United States’ security priorities are changing, as its focus turns to the Indo-Pacific and to the protection of its homeland.

This is only one part of the picture, however. In this more complex world, the UK must deal with a wide array of challenges to its security, prosperity, and values at the same time. It must also be ready to absorb and respond to surprises and shocks, recognising that it cannot prevent or protect against all risks and threats.

Previous reviews have recognised the rapid deterioration of the international security environment. However, the speed of change in Defence has not kept pace with the threat or the scale of the challenge. The imperative for a shift in approach is clear.

A more volatile and uncertain world: the strategic context to 2040

The environment in which Defence must operate in the coming years is shaped by two major and accelerating trends:

- Growing multipolarity and intensifying strategic competition between states—and with non-state actors—for political, military, economic, and technological power. As part of this competition, states are seeking to reshape the rules-based international order that has governed international relations since the Second World War.[footnote 24] The clear shift in US security priorities underlines how urgent and different managing strategic competition now is.

- Rapid and unpredictable technological progress that drives strategic competition and continually changes how armed forces must be organised, equipped, and fight.

These trends will interact with a backdrop of persistent transnational challenges, including:

- Climate change and environmental degradation, which: are creating new geographical realities and competition for resources; are driving migration, instability, and more frequent humanitarian disasters; and demand military adaptation for operations in more extreme weather conditions. Of particular importance to Defence is the likelihood that the Arctic and High North will be ‘ice-free’ each summer by 2040, providing access to more actors and creating a new site for competition within the UK’s wider neighbourhood.

- The enduring threat of terrorism. The threat posed by overseas terrorist groups is rising again, demanding attention and resources.[footnote 25] Daesh and al-Qa’ida have evolved, while state support is increasing some terrorist groups’ capabilities, including in cyberspace.

- Uneven global demographic change, which is altering global power balances and driving domestic and regional instability, including through migration, urbanisation, and new demands on governments for employment and social welfare support.

Confronting any one of these challenges is difficult. Confronting them simultaneously poses a huge test for the UK and for Defence.

Growing multipolarity and strategic competition

Intensifying strategic competition will make it more difficult for the UK and its allies to shape the world and events in their interests. Regional settlements and solutions may be necessary as it becomes harder for states to achieve common goals at the global level. The relationship between the US and China will be a key factor in a more multipolar world marked by ‘great power’ competition and in which global power is more widely—if unevenly—distributed across regions and countries. This competition is not just among states: terrorist organisations, organised crime groups, proxy actors and partner groups, and powerful private actors all seek to shape the geopolitical environment to their advantage.

Managing competition between states—and the potential for escalation to crisis and conflict—will be more challenging. States such as Russia are intentionally blurring the lines between nuclear, conventional, and sub-threshold threats, complicating the ability of the UK and its allies to manage potential escalation and miscalculation. Technology creates new paths for escalation by creating new ways to disrupt and coerce, for example, in cyberspace and space. States and non-state actors are ever-more aggressive in using sub-threshold activities to seek advantage.

At the other end of the spectrum, nuclear-armed states like Russia and China are putting nuclear weapons at the centre of their security strategies, increasing the number and types of weapons in their stockpiles. The coming decades will be defined by multiple and concurrent dilemmas, proliferating and disruptive technologies, and the erosion of international agreements and organisations that have previously helped to prevent conflict between nuclear powers. Strategic stability will be challenged, with new and more complex pathways to escalation that the UK and its allies will need to address. Allied assurance will become more complicated as others may be incentivised to develop nuclear weapons of their own.

Russia: an immediate and pressing threat. Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine makes unequivocally clear its willingness to use force to achieve its goals, as well as its intent to re-establish spheres of influence in its near-abroad and disrupt the international order to the UK and its allies’ disadvantage. While the Ukraine conflict has temporarily degraded Russian conventional land forces, the overall modernisation and expansion of its armed forces means it will pose an enduring threat in key areas such as space, cyberspace, information operations, undersea warfare, and chemical and biological weapons. Russia’s war economy, if sustained, will enable it to rebuild its land capabilities more quickly in the event of a ceasefire in Ukraine.

China: a sophisticated and persistent challenge. China is increasingly leveraging its economic, technological, and military capabilities, seeking to establish dominance in the Indo-Pacific, erode US influence, and put pressure on the rules-based international order. Chinese technology and its proliferation to other countries is already a leading challenge for the UK, with Defence likely to face Chinese technology wherever and with whomever it fights. China is likely to continue seeking advantage through espionage and cyber-attacks, and through securing cutting-edge Intellectual Property through legitimate and illegitimate means. It has also embarked on large-scale, extraordinarily rapid military modernisation across its forces. This includes:

- A vast increase in advanced platforms and weapons systems, such as space warfare capabilities.

- The unprecedented diversification and growth of its conventional and nuclear missile forces, with missiles that can reach Europe and the UK.

- More types and greater numbers of nuclear weapons than ever before, with its arsenal expected to double to 1,000 nuclear warheads by 2030.

Iran and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK): regional disruptors. Iran will continue to conduct destabilising activities across the region, including sponsoring proxies and partners such as Hamas, Hezbollah, the Houthis, and Iranian-aligned Iraqi militias. Its escalating nuclear programme presents a risk to international security and the global non-proliferation architecture. The DPRK will likely pursue further nuclear modernisation to guarantee regime survival and coerce its neighbours. Both countries are developing missile programmes with growing reach, and they continue to pose a direct threat to the UK in cyberspace.

Continued alignment and new sources of hostility. China and Russia have deepened their relationship and there will continue to be grounds for both strategic and opportunistic alignment with Iran and the DPRK. However, the dynamics of these relationships will be conditioned by differing interests and longstanding mistrust. They will likely continue seeking to draw others into their transactional networks in pursuing a variety of objectives. As global power dynamics change, it will be important to scan for new threats, including from emerging ‘middle powers’ that may be hostile to UK interests.

Rapid and unpredictable technological change

Rapid advances in technology offer both opportunity and risk, changing the global distribution of power. Emerging technologies are already changing the character of warfare more profoundly than at any point in human history. Progress will continue across a range of technologies whose collective impact will be highly unpredictable (Box 2).

Warfare will be shaped by an evolving mixture of high-end and low-end military capabilities.[footnote 26] The widespread availability of commercial, off-the-shelf capabilities will enable a broader range of state and non-state actors to develop and possess them. This will have significant implications for deterrence and escalation management, as well as for the UK’s freedom of manoeuvre across land, sea, air, and space. It will also change the economics of defence, with low-cost weapons being used to damage or exhaust expensive military capabilities. Technological advancements are outpacing the development of regulatory frameworks to govern many of the most potentially disruptive technologies. The UK’s competitors are unlikely to adhere to common ethical standards in developing and using them.

Box 2: Technologies that are redefining warfare

Advantage on the battlefield will not come from a single technological advance but from the combination of existing capabilities and a range of emerging technologies that include:

- Artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning, and data science, improving the quality and speed of decision-making, the resilience of digital networks, and operational effectiveness. Forecasts of when Artificial General Intelligence[footnote 27] will occur are uncertain but shortening, with profound implications for Defence.

- Robotics and autonomy, with armed forces increasingly using uncrewed and autonomous capabilities to generate mass and lethality.

- Enhanced precision weapons that mean targets can be struck with greater accuracy from ever greater ranges.

- Directed energy weapons, such as the UK’s DragonFire, which have the potential to reduce collateral damage and reliance on expensive ammunition.

- Hypersonic missiles, which, travelling at over five times the speed of sound, may offer greater range and greater ability to evade defences.

- Space-based capabilities that enable all aspects of modern operations. States are rapidly developing ways to disrupt military and civilian assets in and from space.

- Quantum. Advances in quantum computing offer the potential to break encryption, making secure communications much more difficult. Quantum technologies have the potential to reduce dependence on satellite-based GPS, which may be vulnerable to interference.

- Cyber threats that will become harder to mitigate as technology evolves, with AI, quantum technology, and the increasing dependence on satellite communications likely driving the most disruptive changes to the cyber threat landscape.

- Engineering biology that creates the potential to enhance the capacity of the armed forces through advances in medicine, healthcare, and wellbeing, possibilities for new energetic and explosive materials, as well as avenues for enormous harm in the shape of new pathogens and other weapons of mass destruction.

What does this mean for the UK and for Defence?

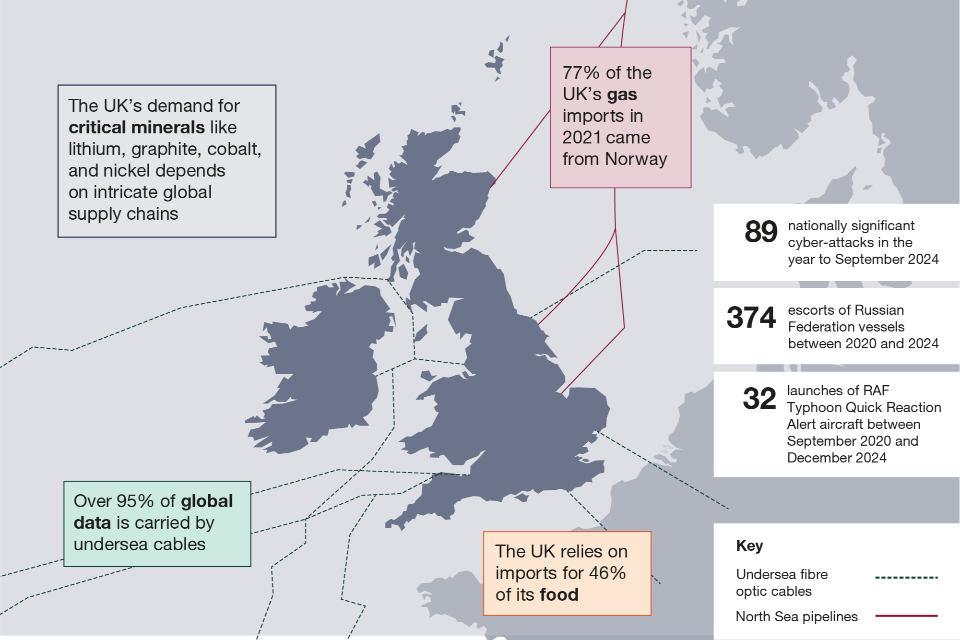

Defence must prepare for a much more difficult world of heightened competition, more frequent crisis, and conflict that sees conventional military attacks combined with intensified sub-threshold aggression (Box 3) and potentially with threats to use nuclear or other weapons of mass destruction. The UK is already subject to daily sub-threshold attack, targeting its critical national infrastructure, testing its vulnerabilities as an open economy and global trading nation (Figure 2), and challenging its social cohesion. Changes in the strategic context mean that UK Defence must plan on the basis that NATO Allies may be drawn into war with—or be subject to coercion by—another nuclear-armed state. With the US clear that the security of Europe is no longer its primary international focus, the UK and European Allies must step up their efforts.

Figure 2: UK daily life: overseas dependencies and threats

Map of the UK surrounded by key facts demonstrating the UK’s reliance on global supply chains for critical minerals, gas and food imports, and undersea fibre optic cables for data. It includes further statistics on the threat facing the UK demonstrated by the number of cyber-attacks, naval escorts of Russian Federation vessels, and launches of RAF Typhoon Quick Reaction Alert aircraft.

Box 3: Potential effects of war on the UK’s way of life

Based on current ways of war, if the UK were to fight a state-on-state war as part of NATO in 2025, it could expect to be subject to some or all of the following methods of attack:

- Attacks on the Armed Forces in the UK and on overseas bases.

- Air and missile attack (from long-range drones, cruise, and ballistic missiles) targeting military infrastructure and critical national infrastructure (CNI) in the UK.

- Increased sabotage and cyber-attacks affecting on- and offshore CNI.

- Attempts to disrupt the UK economy—especially the industry that supports the Armed Forces—including through cyber-attack, the interdiction of maritime trade, and attacks on space-based CNI.

- Efforts to manipulate information to undermine social cohesion and political will.

The state of Defence today

The starting point for this Review is a UK military with innumerable strengths, respected worldwide for its dedication and professionalism. The UK remains at the forefront of NATO efforts to safeguard the Euro-Atlantic against growing Russian aggression in all domains, providing the ultimate guarantee of UK and Allied security in declaring its nuclear deterrent to the Alliance. The Armed Forces are a vital and agile instrument in achieving Government priorities: securing NATO’s front line in Estonia and Poland; airdropping aid for the Palestinian people into Gaza; helping to defend Israel against Iranian air attack; protecting international shipping lanes in the Red Sea; defending the UK against persistent cyber-attack; and enhancing UK relationships with its allies and partners in support of collective security.

Defence also remains an integral part of the UK economy and wider society, supporting 440,000 high-quality jobs across the country and driving social mobility through the training it offers to Armed Forces personnel and civil servants, including thousands of apprentices. Examples of innovation excellence within Defence demonstrate its ability to deliver cutting-edge capabilities to warfighters and the potential to deliver greater economic growth across the UK.

However, Defence is still largely shaped by the operations of the post-Cold War era, primarily conducted against non-state opponents. The size and readiness of the Armed Forces declined as the threat posed by the Soviet Union receded. The Cold War’s large standing force of over 311,000 Regular personnel has fallen to just over 136,000, with only a small set of forces ready to deploy at any given moment and the rest held at varying levels of readiness. Defence spending reduced in parallel, from 4.1% of GDP in 1989 to 2.3% today.

We do need to put more into our defences because otherwise it won’t be long before something more significant happens and we will think it should’ve been more of a priority

Citizens’ Panel member, Rollestone Camp

This trajectory of declining investment has been made more acute in recent years by additional financial pressures, including inflation and currency fluctuations following the Covid-19 pandemic and Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Positive efforts to improve military personnel’s salaries and buy equipment designed to meet future threats have added further pressure on departmental finances.

More fundamentally, Defence’s wider ways of working remain suited to a peacetime era, with innovation stifled and bureaucracy consuming precious time and effort. The result is an organisation that is not currently optimised for warfare against a ‘peer’ military state:[footnote 28]

- A focus on ‘exquisite’ capabilities has masked the ‘hollowing out’ of the Armed Forces’ warfighting capability. Stockpiles are inadequate, further reduced by the important and necessary transfer of materiel to Ukraine. The Strategic Base lacks capacity and resilience following years of under investment. Medical services remain optimised for counter-terrorism operations and lack the capacity for managing a mass-casualty conflict.

- Procurement systems and Defence’s relationship with industry have not materially changed since the Cold War. Risk reduction and consensus decision-making are prioritised over productivity and innovation at the pace of technological change. Export opportunities are too frequently an afterthought in planning. Optimism about equipment cost and timelines for delivery means the Equipment Plan is consistently over-budget and outdated capabilities remain in the field for too long. Defence struggles to prioritise science and technology spending and exploit innovation for operational advantage. It is insufficiently prepared for the digital battlefield, lacks scale and resilience in data flows, and carries intolerable levels of cyber risk.

- Poor recruitment and retention, shoddy accommodation, falling morale, and cultural challenges have created a workforce crisis. The numbers of UK Regulars and Reservists have been in persistent decline (by 8% since 2022 for the Regular Armed Forces). The shortfall impacts disproportionately on the skills most critical to UK advantage, as it does for allies and partners.

The case for transformation

The Armed Forces have begun the essential process of transformation in response both to this changing context and to lessons from the war in Ukraine. However, they remain fundamentally shaped by the risks and demands of the post-Cold War era, when successive Governments reasonably sought to maximise the ‘dividend’ offered by peace in Europe.

The MOD, wider Government, and industry must be better prepared for high-intensity, protracted war. The sweeping and rapid changes to the international security environment mean it is not enough to change only how and with what the Armed Forces fight. To deter threats through being ready for war, the whole of Defence must change how it supports the Armed Forces as part of a more flexible policy response: deterring attacks that blur the lines between competition and conflict across all domains, harnessing the very best technologies at wartime pace, and drawing on support from across Government, industry, society, and allies. The following chapters chart the course of this transformation.

3. Roles for UK Defence

The fundamental role of the Armed Forces is to deter threats so that fighting a war—in defence of the UK, the Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies, and allies—is not necessary. It must be unequivocally clear to potential adversaries that the UK and NATO have the ability and will to fight.

The UK last faced a direct military threat from a highly capable state adversary during the Cold War. Since then, it has relied largely on an expeditionary approach to disrupt potential threats before they could reach Europe. In parallel, the UK has guarded against the possible re-emergence of more significant threats through its nuclear deterrent and membership of NATO. This is no longer sufficient. The dynamic nature of today’s threats (Chapter 2) presents a vastly more complex security challenge.

As the Prime Minister has stated, navigating this environment demands an integrated, whole-of-society approach to deterrence and defence. Most importantly, the Government must be able to act and adapt with agility to create doubt and dilemmas for adversaries and to maintain escalation dominance—detecting and attributing attacks, choosing when and how to respond, and being able to sustain that response and escalate again if necessary. To achieve this, the UK will need to:

- Increase its options for threatening retaliation—whether developed nationally or with allies—to convince a potential adversary that the cost of its actions will outweigh the potential benefits.

- Build national resilience to attacks and shocks, enhancing the UK’s ability to withstand and recover quickly and to deny adversaries potential benefits. Infrastructure that is critical to the UK economy and way of life must be protected. Re-establishing credible national preparations for war, home defence, and industrial mobilisation is a priority.

- Nurture strong relationships with allies. No state can address all these challenges alone. Together, the UK and its allies have greater economic, military, and diplomatic influence than any of their potential adversaries—individually or combined.

Defence plays a central role in this whole-of-society approach. It is a key instrument of Government: home to the UK’s nuclear deterrent, multi-domain conventional and Special Forces; and sole provider of highly specialist capabilities that are vital to national security, such as counter-terror and counter-chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear expertise. To achieve maximum effect in support of Government objectives—whether in war or during periods of heightened competition or crisis—it must seamlessly direct these forces across domains[footnote 29] and with allies, drawing on partners across Government, industry, and wider society.

A ‘NATO First’ approach to deterrence and defence

Collective security, underpinned by formal alliances and partnerships, is a force multiplier for the UK’s deterrence and defence. At the forefront of the UK’s many valuable alliances is NATO, which has brought peace to the Euro-Atlantic for more than 75 years. Under Article V of NATO’s founding treaty, the UK would always expect to fight a ‘peer’ military adversary alongside Allies. But the Alliance provides more than just strength in numbers in the event of a crisis. It provides a unique forum for collective action and industrial collaboration in the Euro-Atlantic and facilitates agreement on global issues and partnership with countries beyond the region.

There is an unequivocal need for the UK to redouble its efforts within the Alliance and to step up its contribution to Euro-Atlantic security more broadly—particularly as Russian aggression across Europe grows and as the United States of America (US) adapts its regional priorities.

The defining principle of this Review is therefore ‘NATO First’ (Box 4). This demands a different approach from that taken since the end of the Cold War. The Alliance must be the starting point for how the Armed Forces are developed, organised, equipped, and trained in order to contribute to deterrence in the Euro-Atlantic, shaping the environment and potential adversaries’ thinking every day. This approach will require organisational and cultural change within Defence and across Whitehall, given the vital support provided by other Government departments. Efforts to deepen bilateral and minilateral relationships should similarly be geared to strengthening Europe’s security architecture (Chapter 5).

Box 4: What does ‘NATO First’ mean for UK Defence?

Defence will be integrated with NATO by design. This demands that NATO is:

- Foremost in how Defence plans. The UK should prioritise its ability to contribute to NATO plans (including for defending the UK), which should be at the heart of capability development and force design. The UK must play a leading role in developing Alliance plans, standards, and verification.

- The foundation of how Defence thinks: mainstreamed through policy, doctrine and concepts development, education, and talent management.

- Embedded in how Defence acts: ensuring national activity prioritises and enhances NATO objectives and integration. This includes operations, exercises, industrial strategy, and defence engagement activity.

As NATO renews its own approach to deterrence and defence, the UK must:

- Back up its commitment to Article V by putting NATO at the heart of how it plans to fight in the Euro-Atlantic area. The UK should prioritise its ability to fight as part of NATO strategic and operational plans, actively support their development, and contribute leadership within the command structures that will execute them. This must continue to be underwritten by the UK’s nuclear deterrent, assigned to the defence of NATO and adapted as nuclear threats to the Alliance increase.

- Put NATO at the centre of its force development, with a focus on shaping and meeting ambitious NATO Capability Targets designed to strengthen the Alliance’s military capabilities and to improve burden-sharing between Europe and Canada on the one hand and the US on the other.

- Meet civil defence and resilience planning obligations under Article III of the NATO founding treaty to strengthen deterrence and assure the UK’s ability to project power in support of NATO in the Euro-Atlantic and beyond.[footnote 30] The UK must also ensure it can provide military and civilian Host Nation Support to NATO, including in times of crisis and war.

- Support NATO’s development in areas critical to warfighting. This should include: leading the way in new concepts; encouraging NATO to reflect priority defence and dual-use technologies in capability planning processes; and influencing standards and operating practices accordingly. Drawing on experience, expertise, and capabilities developed through national and minilateral activity—for example, as part of the Joint Expeditionary Force—would further support NATO-wide innovation. Engaging with and leveraging the work of NATO’s UK-based innovation organisations[footnote 31] would be mutually beneficial in pursuing this goal.

- Engage fully in NATO-led efforts to strengthen transatlantic industrial cooperation as a central plank of collective deterrence and defence, with NATO an increasingly important convenor and standard-setter. Influencing NATO standards and adopting them by default is key.

A ‘NATO First’ approach does not mean ‘NATO only’. The Alliance itself recognises the importance of working with partners such as the Indo-Pacific Four[footnote 32]—reflecting the connection between Euro-Atlantic security and that of other regions such as the Middle East and Indo-Pacific. The UK also has significant interests, commitments, and responsibilities beyond the Euro-Atlantic. These include: the defence of UK sovereign territory; the UK’s status as one of five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council; the Five Eyes intelligence alliance;[footnote 33] and flagship capability partnerships AUKUS and the Global Combat Air Programme. All are critical to UK and allied security and to shaping the international security environment.

Core defence roles

The Review has identified enduring and mutually reinforcing roles that Defence must fulfil to deliver the outcomes set by the Government within the resources available. They have informed our recommendations on the transformative methods and capabilities in the chapters that follow. In alignment with a NATO First approach, under Role 1 and Role 2 effort and resources are focused on defence and deterrence in the Euro-Atlantic, centred on home defence and resilience. Role 3 uses all Defence levers—as part of a cross-government effort—to defend where the UK must and to shape the environment in favour of national interests where it can. Delivery of all three roles will depend on capabilities deployed in the space and cyber and electromagnetic domains as well as common foundational enablers. It is intended that the UK Special Forces would also contribute to delivery of all three roles where needed, as part of a Defence-wide effort to deliver crisis response, whether in the UK, the Euro-Atlantic, or beyond.

To meet the most significant threats facing the UK, the roles for Defence are:

Role 1: Defend, protect, and enhance the resilience of the UK, its Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies

The nature of today’s threats mean Defence must once again have credible plans for defending UK home territory as part of NATO, rooted in improved national resilience (Chapter 6)—a NATO Article III obligation. The Armed Forces must also be able to defend and protect the Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies and be ready to deploy globally to support British nationals overseas during crises.

Role 2: Deter and defend in the Euro-Atlantic