Guidance on the management of suspected tetanus cases and the assessment and management of tetanus-prone wounds

Updated 15 March 2024

Applies to England

Changes from previous guidance

Main changes to guidance 2023

Due to the lack of sensitivity of the assay and ethical guidance – Animal (scientific procedures) Act 1986 – the service for the detection of tetanus neurotoxin in serum has been terminated. Debrided tissue from suspected site of infection should be sent to the Gastrointestinal Bacteria Reference Unit, UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA), Colindale for Clostridium tetani PCR and culture.

Minor update to guidance 2019

Results of testing by National Institute for Biological Standards and Control (NIBSC) for anti-tetanus antibodies for additional intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) products (for treatment of clinical tetanus) and human normal immunoglobulin (HNIG) products (for management of tetanus-prone wounds) are included.

Main changes to guidance 2018

These revised guidelines amalgamate previous guidelines on management of clinical tetanus and provide updated advice on laboratory testing and treatment of suspected tetanus cases and management of tetanus-prone wounds.

Emphasis is placed on the clinical diagnosis of suspected tetanus (rather than waiting for the results of laboratory investigations) as the major criterion for initiating treatment and case management.

The guidance emphasises the importance of C. tetani PCR on debrided wound tissue as the primary confirmatory laboratory test for tetanus. However, a negative result is insufficient to exclude clinical tetanus.

Whilst historically serology testing has been a key method to support the investigation of clinically suspected tetanus, a review of recent cases highlighted that some cases of clinical tetanus occurred in the presence of protective levels of anti-tetanus antibodies (>0.1U/ml). Therefore antibody levels above the protective threshold is also not sufficient to rule out clinical tetanus.

Since the publication of interim guidance on use of IVIG, testing of additional IVIG products for the presence of anti-tetanus antibodies has been undertaken by NIBSC and is summarised. Recommendations for IVIG now incorporate results from this additional testing.

Guidance of classification of tetanus-prone wounds has been updated.

Revised guidance on the use of intramuscular tetanus specific immunoglobulin (IMTIg) and HNIG for of the management of tetanus-prone wounds is included in response to ongoing supply shortages. The updated guidance, which has been approved by the UK Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI) has been informed by an evidence review of the comparative boosting of a prophylactic dose of TIG with a booster dose of tetanus vaccine.

The scope of this document is to assist in the diagnosis, treatment and clinical management of cases of tetanus and in the management of tetanus-prone wounds. Further detailed information on tetanus vaccine and the national vaccination programme is available in the Green Book (1).

1. Causative organism

Tetanus is caused by a neurotoxin produced by Clostridium tetani, an anaerobic spore-forming Gram positive bacterium. C. tetani can be present in the gastrointestinal tract and faeces of horses and other animals and the spores are widespread in the environment, including soil. Spores can survive hostile conditions for long periods of time and human infection is acquired when C. tetani spores are introduced into the wounds contaminated with soil. However, tetanus may also follow injecting drug use or abdominal surgery. In some cases no exposure is reported and it is assumed that unnoticed minor wounds were the route of entry. The incubation period of the disease is usually between 3 and 21 days, although it may range from one day to several months depending on the character, extent and localisation of the wound (2).

2. National epidemiology

The incidence of tetanus decreased substantially following the introduction of national tetanus immunisation in 1961 (1). On average, over the last 3 decades, there have been less than 10 cases of tetanus per year reported in England and Wales (3). Immunisation provides personal protection only since, as C. tetani is an environmentally acquired organism, there is no herd immunity effect. Between 2001 and 2022, 147 cases of tetanus were reported to UKHSA (formerly Public Health England) through multiple data sources (range 3 to 22 cases per year) (3, 4, 5). The highest incidence has been observed among individuals aged over 64 years old who are at highest risk of being under-immunised, with very few cases of tetanus reported amongst children. Of the cases with information on immunisations status, less than 10% were appropriately immunised for their age. A characteristic of 2 of the recent tetanus cases in older individuals was that they were documented as having received a ‘booster’ dose of a tetanus-toxoid containing vaccine, despite no evidence of primary vaccination.

More recently there has been a trend to more localised rather than generalised tetanus and the over-all case-fatality rate among all reported cases of tetanus in England and Wales reduced from 29% between 1984 and 2000 (6) to 11% in the following 14 years (7) suggesting the severity of illness may be decreased by partial immunity. Of the 16 deaths reported in England and Wales between 2000 and 2022, 4 were cryptogenic with no reported injury.

Between July 2003 and September 2004, the first cluster of cases in people who inject drugs (PWID) in the UK was identified. This included 25 clinically diagnosed cases in young adults, of which 2 patients died (case fatality 8%) (8). Potential sources of C. tetani in PWID include contamination of drugs, adulterants, paraphernalia, and skin. Intramuscular and subcutaneous drug use, in particular, is associated with tetanus infections (9). Following this cluster in 2003 to 2004 only 13 sporadic cases of tetanus were reported in PWID to the end of 2022.

3. Clinical features

The most common presentation of tetanus is generalised tetanus, however, 2 other forms, local and cephalic, are also described (2). Neonatal tetanus is also described but has been eliminated in the UK for decades.

Generalised tetanus is characterised by trismus (lockjaw), tonic contractions and spasms. Tonic contractions and spasms may lead to dysphagia, opisthotonus and a rigid abdomen. In severe cases they may cause respiratory difficulties. Autonomic instability is typical. Consciousness is not affected.

Localised tetanus is rigidity and spasms confined to the area around the site of the infection and may be more common in partially immunised individuals. Localised symptoms can continue for weeks or may develop into generalised tetanus.

Cephalic tetanus is localised tetanus after a head or neck injury, involving primarily the musculature supplied by the cranial nerves.

4. Diagnosis

Tetanus is primarily a clinical diagnosis (6). A probable case can be defined as:

“‘In the absence of a more likely diagnosis, an acute illness with muscle spasms or hypertonia, and diagnosis of tetanus by a health care provider.”

The key clinical features of generalised tetanus include at least 2 of the following:

- Trismus (painful muscular contractions primarily of the masseter and neck muscles leading to facial spasms).

- Painful muscular contractions of trunk muscles.

- Generalized spasms, frequently position of opisthotonus.

Severity can be graded as below.

Grading of severity

Grade 1 (mild)

Mild to moderate trismus and/or general spasticity, little or no dysphagia, no respiratory embarrassment.

Grade 2 (moderate)

Moderate trismus and general spasticity, some dysphagia and respiratory embarrassment, and fleeting spasms occur.

Grade 3a (severe)

Severe trismus and general spasticity, severe dysphagia and respiratory difficulties, and severe and prolonged spasms (both spontaneous and on stimulation).

Grade 3b (very severe)

As for severe tetanus plus autonomic dysfunction, particularly sympathetic overdrive.

Localised tetanus (see section 3) can present with symptoms around the site of the wound.

4.1 Laboratory testing to support clinical diagnosis

Laboratory tests are available to support the clinical diagnosis. Although a serum sample should be taken before administering immunoglobulin, treatment of clinical case of tetanus should never be delayed to wait for the laboratory result (see Appendix 1) and case management should proceed based on clinical review including clinical presentation, history of injury and vaccination status.

Samples

- Tissue samples: If there is an obvious wound, debrided tissue or pus may be sent in cooked meat broth ( or anaerobic broth) for PCR and culture isolation of C. tetani. Tissue is the best specimen and debridement has an additional therapeutic benefit which is crucial in the management of tetanus.

- Isolates from wound culture: Suspect clinical isolates of Clostridium should be sent in cooked meat broth.

- Serum: A serum sample may also be collected. This should be taken before immunoglobulin is given. Serum, at least 200uL, will be used for measuring the level of antibodies specific to tetanus neurotoxin.

Wound, pus, debrided tissues and cultures should be sent to the Gastrointestinal Bacteria Reference Unit (GBRU), and serum to the Respiratory and Vaccine Preventable Bacteria Reference Unit (RVPBRU) at:

UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA)

61 Colindale Avenue

London NW9 5EQ

Please notify the laboratories when sending samples on telephone: 0208 327 7887.

Testing

Laboratory investigations available to support a diagnosis of tetanus are:

Detection of C. tetani and tetanus neurotoxin gene

In tissue or deep wound material or from a pure culture, by direct PCR and culture methods. A negative result does not exclude tetanus. This is the most sensitive test currently in use and wound debridement to obtain samples is clinically beneficial.

Detection of IgG against tetanus toxoid in serum

An antibody level of less than 0.1 IU/mL in serum taken during the acute illness but before administration of any immunologulin can support the diagnosis of tetanus. An antibody level of 0.1 IU/mL or above does not, however, exclude the diagnosis of tetanus.

If in doubt regarding interpretation of the result, please contact the RVPBRU for advice on 020 8327 7887.

Point of care (POC) antibody testing kits are not recommended for use in diagnosis of suspected tetanus (see below).

5. Clinical management

Clinical management of suspected tetanus (including localised tetanus) includes:

- early wound debridement

- antimicrobials including agents reliably active against anaerobes such as intravenous benzylpenicillin, metronidazole can used, please discuss with your local Microbiology team about choice of antibiotics and doses.

- intravenous Immunoglobulin based on weight (see section 5.1)

- vaccination with tetanus toxoid following recovery (see section 6.1)

- supportive care (benzodiazepines for muscle spasms, treatment of autonomic dysfunction, maintenance of ventilation, nursing in a quiet room and so on)

5.1 Treatment of clinical tetanus with IVIG

Early treatment with IVIG can be lifesaving and its use should be considered based on clinical judgement or diagnosis. An IV tetanus immunoglobulin (TIG) product is no longer available in the UK. In the absence of IV TIG, IVIG is the recommended treatment for clinical suspected tetanus. This is based on previous testing of the IVIG product Vigam 5% for anti-tetanus antibodies, which was carried out by the NIBSC and showed that Vigam contained reasonable levels of tetanus antibody when measured by ELISA which correlated well with in vivo toxin neutralising test (TNT) anti-toxin assays.

More recently, 10 further IVIG products that were being used in the NHS: Gammaplex (5%), Privigen 10%, Octagam (5 and 10%), Intratect (5% and 10%), Flebogama (5% and 10%), Panzyga 10% and Gammunex 10% have been tested for the presence of anti-tetanus antibodies by NIBSC and have been shown to be comparable in terms of their anti tetanus potency. Test results are shown in Appendix 2.

The recommended dose of anti-tetanus antibodies is based on weight:

- for individuals less than 50kg, 5,000 IU (international units)

- for individuals over 50kg, 10,000 IU

The volume of human IVIG required to achieve the recommended dose of anti-tetanus antibodies is shown in Table 1.

Table 1. IVIG products for treatment of clinical tetanus

| IVIG Products tested for anti-tetanus antibodies | Volume required (in mL) for individuals under 50kg | Volume required (in mL) for individuals over 50kg |

|---|---|---|

| Gammaplex 5%, Intratect 5%, Flebogamma 5%, Vigam 5%, Octagam 5% | 400mL | 800mL |

| Privigen 10%, Octagam 10%, Intratect 10%, Flebogamma 10%, Panzyga 10%, Gammunex 10% | 200mL | 400mL |

*Due to the slight variability between the products and batches, the lowest antibody levels found have been used to calculate the doses of intravenous immunoglobulin required to achieve the recommended dose of anti-tetanus antibodies.

Please note that IVIG is not available from UKHSA. Healthcare trusts should contact manufacturers directly for supply (see Appendix 2).

For advice regarding clinical management of cases or other queries relating to suspected cases during office hours, please contact the Gastrointestinal Bacteria Reference Unit (GBRU), UKHSA Colindale on 0208 327 7887 or email GBRU@ukhsa.gov.uk

The UKHSA duty doctor is requested to discuss all suspected cases with the on-call consultant microbiologist if calls are received during working hours.

Out of hours please contact the UKHSA duty doctor on 0208 200 4400 for all queries and advice.

6. Preventative measures

6.1 Primary prevention

Effective protection against tetanus can be achieved through active immunisation with tetanus vaccine, which is a toxoid preparation. A total of 5 doses of vaccine at the appropriate intervals are considered to provide lifelong immunity (1). Single antigen tetanus vaccine (T) and combined tetanus/low dose diphtheria vaccine (Td) have been replaced by the combined tetanus/low dose diphtheria/inactivated polio vaccine (Td/IPV) for adults and adolescents for all routine uses in these age groups (11). Recovery from tetanus may not result in immunity and vaccination following tetanus is indicated. A full course of tetanus and diphtheria vaccines consists of 5 doses as follows:

Table 2. Schedule of tetanus and diphtheria vaccination

| Schedule | Children | Adults |

|---|---|---|

| Primary course | 3 doses of vaccine (usually as DTaP/IPV/Hib/HepB) at 2, 3 and 4 months of age | 3 doses of vaccine (as Td/IPV) each one month apart |

| 4th dose | At least 3 years after the primary course, usually pre-school entry (as DTaP/IPV) | 5 years after primary course (as Td/IPV) |

| 5th dose | Aged 13 to 18 years before leaving school (as Td/IPV) | 10 years after 4th dose (as Td/IPV) |

For further details see Chapter 30 in UKHSA’s Green Book: Immunisation against Infectious Disease and Vaccination of individuals with uncertain or incomplete immunisation status.

6.1.1 Occupational Health

Tetanus is not transmitted from person-to-person, so those caring for patients with tetanus are not at risk of acquiring tetanus from the patient. However, like the general population, if they have not received the recommended 5 doses of tetanus-containing vaccine or are unsure about their vaccination status, they should check with their GP practice.

Employees in some occupations may be at increased risk of tetanus-prone wounds (see below) so it is particularly important that occupational health providers check tetanus vaccination status.

6.2 Management of tetanus-prone wounds

Tetanus-prone wounds [note 1] include:

- puncture-type injuries acquired in a contaminated environment and likely therefore to contain tetanus spores [note 1], for example gardening injuries

- wounds containing foreign bodies such as wound splinters [note 1]

- compound fractures

- wounds or burns with systemic sepsis

- certain animal bites and scratches [note 2]

Notes

Note 1: Individual risk assessment is required and this list is not exhaustive, for example a puncture-wound from discarded needle found in a park may be a tetanus-prone injury but a needlestick injury in a medical environment is not.

Note 2: Similarly, although smaller bites from domestic pets are generally puncture injuries, animal saliva should not contain tetanus spores unless the animal has been rooting in soil or lives in an agricultural setting.

High-risk tetanus-prone wounds include any of the above with either:

- heavy contamination with material likely to contain tetanus spores, for example soil, manure

- wounds or burns that show extensive devitalised tissue

- wounds or burns that require surgical intervention that is delayed for more than 6 hours are high risk even if the contamination was not initially heavy

Thorough cleaning of wounds is essential, surgical debridement of devitalised tissue in high risk tetanus–prone wounds is crucial for prevention of tetanus. If the wound, burn or injury fulfils the above high risk criteria, IM-TIG or HNIG should be given to neutralise toxin. A reinforcing dose of tetanus-containing vaccine is recommended (see Table 4).

Treat tetanus prone-wounds with antibiotics (metronidazole, benzylpeniciilin or coamoxiclav) depending on clinical severity with a view to preventing tetanus and give a reinforcing dose of tetanus containing vaccine.

Suspected cases of localised tetanus (where there is rigidity and/or spasms around the wound) should be treated as clinical cases as described in section 4 and section 5, and not as a tetanus-prone injury. Further doses of vaccine should be administered as required to complete the recommended schedule to provide long term protection.

Table 4. Tetanus immunisation and prophylaxis following injuries

| Immunisation status | Immediate treatment: clean wound [note 1] | Immediate treatment: tetanus prone | Immediate treatment: high risk tetanus prone | Later treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Those aged 11 years and over, who have received an adequate priming course of tetanus vaccine [note 2] with the last dose within 10 years Children aged 5 to 10 years who have received priming course and pre-school booster Children under 5 years who have received an adequate priming course | None required | None required | None required | Further doses as required to complete the recommended schedule (to ensure future immunity) |

| Received adequate priming course of tetanus vaccine [note 2] but last dose more than 10 years ago Children aged 5 to 10 years who have received an adequate priming course but no preschool booster Includes UK born after 1961 with history of accepting vaccinations | None required | Immediate reinforcing dose of vaccine | Immediate reinforcing dose of vaccine One dose of human tetanus immunoglobulin [note 3] in a different site | Further doses as required to complete the recommended schedule (to ensure future immunity) |

| Not received adequate priming course of tetanus vaccine [note 2] Includes uncertain immunisation status and/or born before 1961 | Immediate reinforcing dose of vaccine | Immediate reinforcing dose of vaccine One dose of human tetanus immunoglobulin [note 3] in a different site | Immediate reinforcing dose of vaccine One dose of human tetanus immunoglobulin [note 3] in a different site |

Notes

Note 1: Clean wound is defined as wounds less than 6 hours old, non penetrating with negligible tissue damage.

Note 2: At least 3 doses of tetanus vaccine at appropriate intervals. This definition of ‘adequate course’ is for the risk assessment of tetanus-prone wounds only. The full UK schedule is 5 doses of tetanus containing vaccine at appropriate intervals.

Note 3: If TIG is not available, HNIG may be used as an alternative.

Patients who are severely immunosuppressed may not be adequately protected against tetanus, despite having been fully immunised and additional booster doses may be required.

Determination of vaccination status may not be possible at the time of assessment and therefore a number of POC antibody testing kits have been developed. There is limited information on the clinical benefits of these rapid immunoassays since the published studies are relatively small, with varying results in terms of sensitivity and specificity, and little data with reference to capacity of individuals to respond to antibody boosting. Given the lack of evidence on use in the clinical pathway, POC antibody testing is currently not recommended for use in assessment of tetanus prone wounds or diagnosis of suspected tetanus by the World Health Organization (WHO) (10).

Determination of vaccination status using vaccination records remains the preferred method.

6.2.1 Post-exposure Prophylaxis of Tetanus Prone Wounds with TIg for Intramuscular use (IM-TIg)

Rationale for guidance on post exposure management

Supplies of TIG are sourced from a single supplier and for many years, there has been a supply shortage. In response, in 2013 a Public Health England-convened expert working group advised the use of Human Normal Immunoglobulin product (Subgam), based on the results of potency testing, as an alternative when TIG could not be sourced by NHS Trusts. In July 2018, PHE became aware of a severe shortage of both TIG and Subgam available to the NHS due to manufacturing issues. PHE undertook an urgent review of the comparative boosting of a prophylactic dose of TIG with a booster dose of vaccine, and the likely susceptibility of the UK population, in order to prioritise the use of TIG /HNIG for those at genuine risk. Given the ongoing and serious issues with supply, interim guidance issued in July 2018 has now been formally approved by the JCVI for ongoing use.

Universal vaccination was introduced into the UK in 1961. In the UK, 5 doses of tetanus containing vaccine are routinely offered. The primary series of tetanus containing vaccine is at 2, 3 and 4 months of age, and then a school-entry booster is recommended at 3 years 4 months. Although antibody levels decline around 5 years after the primary series in infancy, there is an excellent response to the booster at 3 years 4 months of age and antibody levels persist at least until age 14, when the adolescent booster dose also results in rapid and high increase in antibody. A recent WHO review concluded that following the primary series, typically immunity persists for 10 years after the fourth dose and for at least 20 years after the fifth dose (10).

The rationale for using IM-TIG in at-risk individuals is to sufficiently and rapidly raise antibody levels in exposed individuals with antibody levels below the protective threshold, and who are not expected to make a sufficiently rapid memory response to vaccination. The median incubation period for tetanus is reported as 7 days but can range from 4 to 21 days and therefore it is important that either TIG or active boosting occurs promptly following an exposure. Peak levels are achieved 4 days after an IM dose. In individuals who receive a vaccine booster after have completed a full primary course, a measurable increase in antibody titres following a vaccine booster has been observed as early as 4 days, and levels increase substantially from day 7. The antibody levels achieved 5 to 7 days after a reinforcing dose of vaccine likely exceeds the estimated antibody boost from a prophylactic dose of IM-TIG in an adult.

The recommended dose if intramuscular TIG is:

- 250 IU for most cases

- 500 IU if more than 24 hours have elapsed or there is risk of heavy contamination or following burns

The dose is the same for both adults and children. IM-TIG is available in 1mL ampoules containing 250 IU. If TIG (for intramuscular use) cannot be sourced, HNIG for subcutaneous or intra-muscular use may be given as an alternative.

Based on testing for the presence of anti-tetanus antibodies of one HNIG product, Subgam 16% in 2011 (see Appendix 2), the volume of Subgam 16% required to achieve the recommended dose of 250 IU was approximately 5mLs, or one vial of the 750mg Subgam product, administered intramuscularly.

Based on in house manufacturer testing in 2018 of a newly available 1,000mg Subgam product, which indicated a slightly lower anti-tetanus potency, the recommended dose of 250 IU is 1 vial of the 1,000mg product (equivalent to 6.4mLs) to be administered intramuscularly in divided doses (please note previously both intramuscular and subcutaneous routes of administration were included in the product license although current license includes subcutaneous route only; however UKHSA recommends the intramuscular route). NIBSC Testing has also been carried out on 2 other HNIG products for subcutaneous or intramuscular use (Cuvitru 20% and Gammanorm 16.5%) with similar levels of antitetanus potency based on their immunoglobulin concentration (see Appendix 2). The dosage recommendations for the management of tetanus-prone wounds using IM-TIG or HNIG for subcutaneous use are summarised in the Table 5.

Table 5. The dose guidelines for management of tetanus prone wounds using IM-TIG or HNIG for subcutaneous use

| Indications | IM-TIG | Subgam 16% | Cuvitru 20% | Gammanorm 16.5% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| For most uses | 250 IU | 6.4mL | 4.5mL | 5mL |

| If more than 24 hours have elapsed or there is risk of heavy contamination or following burns | 500 IU | 12.8mL | 9mL | 10mL |

NHS trusts should source supplies of immunoglobulin for management of tetanus prone wounds directly from the manufacturer.

7. Reporting

Tetanus (local and generalised) is a notifiable disease. Doctors have a statutory duty to notify the ‘proper officer’ at their local council or local health protection team (HPT) of suspected cases.

Clinicians are requested to complete a notification form immediately on diagnosis of a suspected case without waiting for laboratory confirmation of a suspected infection. Diagnostic laboratories also have a statutory duty to report identification of Clostridium tetani under the Health Protection (Notification) Regulations 2010 (12).

Enhanced surveillance of tetanus for England is also carried out by the Immunisation and Vaccine Preventable Diseases Division, UKHSA. CCDCs or HPTs are requested to inform the National Surveillance Team of details of the case by completing the enhanced surveillance questionnaire and returning it to diphtheria_tetanus@ukhsa.gov.uk or phe.diphtheria.tetanus@nhs.net

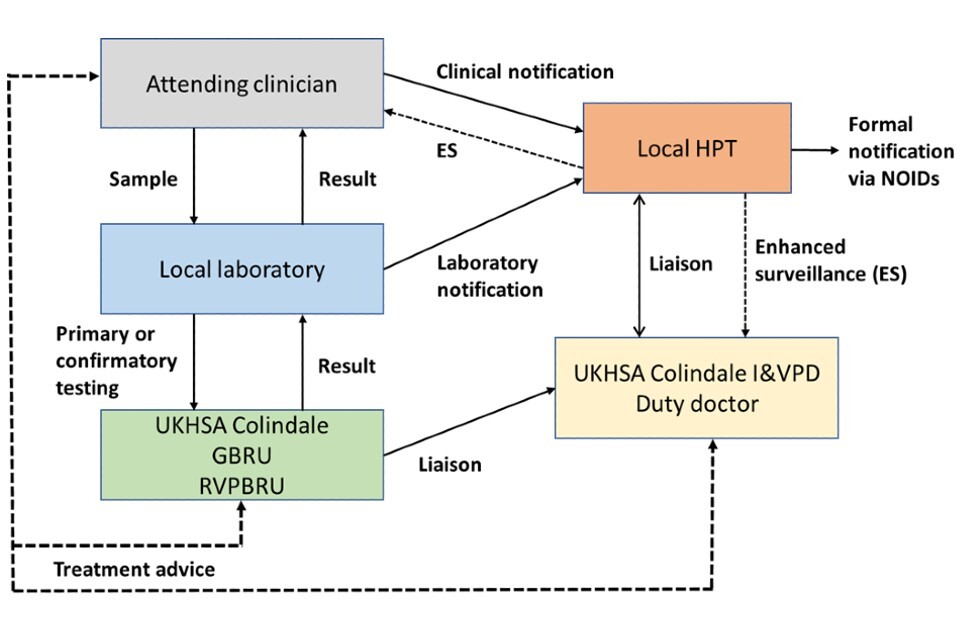

Figure 1 describes data flows between the local NHS laboratory, local HPTs, and UKHSA Colindale for tetanus cases in England.

Figure 1. Case notification flowchart and interaction between departments

Text version of Figure 1

The attending clinician should send samples to the local laboratory for testing and notify the local HPT. The attending clinician will liase with the UKHSA Colindale GRBU for clinical advice (or if out-of-hours, the Immunisation and Vaccine Preventable Diseases Division duty doctor), if needed.

The local laboratory will receive the samples from the attending clinician and will send the samples to the GBRU and/or the RVPBRU for primary or confirmatory testing. The local laboratory will return the results to the attending clinician and should notify the local HPT via a laboratory notification.

UKHSA Colindale GBRU/RVPBRU will receive the samples for primary or confirmation testing from the local laboratory and will share the result with the local laboratory. They will also liase with the UKHSA Colindale Immunisation and Vaccine Preventable Diseases Division.

The local HPT will receive a clinical notification from the attending clinician and/or receive a laboratory notification from the local laboratory. They will liase with the UKHSA Colindale Immunisation and Vaccine Preventable Diseases Division (in hours) and the duty doctor (out of hours). In addition, the local HPT will conduct enhanced surveillance in conjunction with the attending clinician and the UKHSA Colindale Immunisation and Vaccine Preventable Diseases Division

The UKHSA Colindale Immunisation and Vaccine Preventable Diseases Division will liaise with the HPT to complete the enhanced surveillance form.

References

1. UKHSA (2023) ‘Tetanus: the Green Book, Chapter 30’

2. Mandell GL and others. ‘Clostridium tetani’ in Mandell, Bennett, and Dolin’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases’. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone, 2003

4. PHE (2016). ‘Tetanus in England and Wales: 2015. Health Protection Report: volume 10 number 13’

5. PHE (2017). ‘Tetanus in England: 2016. Health protection report: volume 11 number 13’

6. Rushdy AA and others. ‘Tetanus in England and Wales, 1984 to 2000’. Epidemiology and Infection 2003: volume 130, pages 71 to 77

7. Collins S and others. ‘Current epidemiology of tetanus in England, 2001 to 2014’ Epidemiology and Infection 2016: volume 144.

8. Hahné SJM and others. ‘Tetanus in injecting drug users, United Kingdom’. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2006: volume 12 number 4

9. Chin J. (editor). Control of communicable diseases manual. Washington: American Public Health Association, 2000

10. WHO (2018). ‘The immunological basis for immunization series module 3: Tetanus Update 2018

11. Department of Health (2004). ‘New vaccinations for the childhood immunization programme. Chief Medical Officer (CMO) Letters 10 August 2004’

12. UKHSA (2010). ‘Notifiable diseases and causative organisms: how to report’

Appendix 1. Algorithm for diagnosis of tetanus

Text version of algorithm for diagnosis of tetanus

1. When there is a clinical suspicion of tetanus (to be considered in: injecting drug users (PWID), gardening injuries, animal bites or scratches, incompletely immunised patients), the first action is to consider if there is an appropriate clinical scenario.

2. If there is not an appropriate clinical scenario, then consider alternative diagnoses.

3. If there is an appropriate clinical scenario, then please carry out the following actions:

- take samples (see section 4.1): debrided tissue or pus, serum may also be collected (please note this should be taken before immunoglobulin is given)

- give tetanus immunoglobulin or IVIG (see section 5.1)

- contact local microbiologist for advice on antimicrobials and debridement

- notify case to health protection team (see section 7)

- send debrided tissue, wound or pus and cultures to UKHSA Colindale GBRU and serum samples to RVPBRU for primary or confirmation testing

4. For testing of serum samples (see section 4.1):

- the tetanus antibody detection results should be available within 24 hours of receipt (if urgent testing); results may take up to 21 days and therefore treatment should never be delayed while waiting for laboratory results

- results showing tetanus antibody (IgG) levels below 0.1U/ml support a diagnosis of tetanus, however levels above this threshold do not exclude tetanus

5. For testing of wound, tissues or pus (see section 4.1):

- the tetanus PCR or culture results should be available within 5 days of receipt

- results showing the detection of C. tetani support a diagnosis of tetanus, but a negative result does not exclude tetanus

Please note that laboratory tests are supportive and may need expert opinion for interpretation as detailed in section 5.

Appendix 2. Results from tetanus antitoxin assays for human normal immunoglobulin

Testing of human normal immunoglobulin products Subgam and Viagam for levels of tetanus antibodies was performed at the National Institute for Biological Standards and Control (NIBSC) in 2008 and 2011. In 2016, NIBSC undertook further testing of Subgam (for subcutaneous or IM use) and 8 IVIG products commonly in use in the NHS: Vigam 5%, Gammaplex 5%, Privigen 10%, Octagam 10%, Intratect (5% and 10%) and Flebogama (5% and 10%). In 2019, NIBS carried out testing of 3 further commonly used IVIG products (Octagam 5%, Panzyga 10% and Gammunex 10%) and Subgam and 2 further HNIG products for SC/IM use (Cuvitru 20% and Gammanorm 16.5%).

All IVIG products tested were comparable in terms of tetanus potency. The 5% products have a tetanus potency of approximately 15 IU/mL and the 10% products of approximately 30 IU/mL. Similar levels were found in the HNIG products in 2019, but potency levels (approximately 3 IU/mL per 1% immunoglobulin content) were slightly lower than earlier testing of Subgam (3.5 to 4.0 IU/mL per 1% immunoglobulin content). Due to the slight variability between the products and batches, the lowest antibody levels found have been used to calculate the doses of human normal immunoglobulin required to achieve the recommended dose of tetanus antibodies.

| Year of test | Product | Manufacturer | Route | Batch number | ELISA IU/mL (95% CI) | TNT assay IU/mL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | Subgam | BPL | SC/IM | SCBN7647 | 63 | 57 (48-69) |

| 2008 | Subgam | BPL | SC/IM | SCBN7651 | 64 | 57 (48-69) |

| 2011 | Subgam (750mg) | BPL | SC/IM | SCBN8611 | 66.4 | |

| 2011 | Subgam (750mg) | BPL | SC/IM | SCBN8949 | 56.9 | |

| 2011 | Subgam (1500mg) | BPL | SC/IM | SCAN9129 | 60.8 | |

| 2008 | Vigam | BPL | IV | VLAN7724 | 23 | 26 (18-46) |

| 2008 | Vigam | BPL | IV | VLAN7759 | 20 | 18 (15-22) |

| 2008 | Vigam | BPL | IV | VLAN7730 | 23 | 21 (18-26) |

| 2011 | Vigam (5g) | BPL | IV | VLCN9116 | 17.5 | |

| 2011 | Vigam (5g) | BPL | IV | VLCN9117 | 17.9 | |

| 2011 | Vigam (10g) | BPL | IV | VLAN9219 | 15.9 | |

| 2011 | Vigam (10g) | BPL | IV | VLAN9220 | 15.9 | |

| 2016 | Vigam 5% | BPL | IV | VLA15350 VLA15015 VLAN0825 | 15.3 (14.5-16.2) 16.7 (15.8-17.6) 17.6 (16.7-18.6) | 21.0 (17.8-25.4) |

| 2011 | Gammaplex (5g) | BPL | IV | VSCN8627 | 17.8 | |

| 2011 | Gammaplex (5g) | BPL | IV | VSCN9016 | 17.2 | |

| 2011 | Gammaplex (5g) | BPL | IV | VSCN9156 | 19.6 | |

| 2011 | Gammaplex (10g) | BPL | IV | VSAN8599 | 21.6 | |

| 2011 | Gammaplex (10g) | BPL | IV | VSAN9070 | 16.7 | |

| 2011 | Gammaplex (10g) | BPL | IV | VSAN9083 | 17.6 | |

| 2016 | Gammaplex 5% | BPL | IV | VSB15360 VSA15074 VSA15278 | 15.0 (14.2-15.9) 16.6 (15.7-17.6) 14.7 (13.9-15.6) | 19.8(16.8-24.0) |

| 2016 | Privigen 10% | CSL | IV | 432900015 | 27.7 (26.0-29.5) | 32.6 (27.7-39.5) |

| 2016 | Octagam 10% | Octapharma | IV | L609A8541 A436B854E A550B8542 | 30.1 (28.2-32.0) 34.3 (32.2-36.6) 31.2 (29.5-33.0) | 39.6 (33.7-47.9) |

| 2016 | Intratect 10% | Biotest | IV | B790035 8 B790035 6 B790016 02 B790155 7 | 24.0 (22.8-25.4) 25.8 (24.5-27.3) 30.7 (28.5-33.2) 28.2 (26.2-30.5) | 27.9 (23.8-33.8) |

| 2016 | Intratect 5% | Biotest | IV | B791275 6 B791405 13 B791615 6 B791415 4 | 15.7 (14.6-16.9) 14.6 (14.0-15.3) 15.4 (14.7-16.1) 14.5 (13.8-15.1) | |

| 2016 | Flebogamma 10% | Grifols | IV | IBGP4JNJP1 IGGP5B6001 IBGN4DIDK1 | 29.3 (27.5-31.2) 32.1 (30.2-34.2) 31.4 (29.5-33.4) | 36.1 (30.7-43.7) |

| 2016 | Flebogamma 5% | Grifols | IV | IBGL5DCDE1 IBGK4EPES1 IBGJ5R4R61 | 14.8 (14.0-15.6) 16.3 (15.5-17.2) 15.6 (14.8-16.4) | |

| 2019 | Octagam 5% | Octapharma | IV | K822A844A K816A844E K82SB8444 | 16.6 (15.4-17.8) 16.9 (16.2-17.6) 16.8 (15.9-17.8) | |

| 2019 | Panzyga 10% | Octapharma | IV | K819A8214 K820A8262 K725B8215 | 27.4 (25.6-29.4) 29.4 (28.2–30.7) 29.0 (27.3-30.8) | |

| 2019 | Gammunex 10% | Grifols | IV | B3GLC00183 B3GKC00263 B3GJB00303 | 29.2 (27.3-31.3) 35.4 (34.0-36.9) 32.4 (29.0-36.2) | |

| 2019 | Subgam 16% | BPL | SC/IM | SFA18133 SFA18205 SFC17520 | 43.6 (40.5-47.0) 44.3 (42.3-46.5) 46.2 (43.6-49.1) | |

| 2019 | Gammanorm 16.5% | Octapharma | SC/IM | M824A8608 M811C8609 M824D8603 | 49.8 (46.2-53.6) 49.5 (47.2-51.9) 54.5 (51.4-57.9) | |

| 2019 | Cuvitru 20% | Baxalta (Supplier: Shire) | SC/IM | LE135001BB LE13T028AQ LE13T028AH | 56.5 (52.4-60.9) 62.2 (59.3-65.2) 61.1(57.5-64.9) |

Manufacturers’ contact details

| Manufacturer | Phone number |

|---|---|

| Bazalta | 01256 894003 |

| Biotest UK Ltd | 0121 733 3393 |

| BPL (Bio Products Laboratory) | 020 8258 2200 |

| CSL Behring | 01334 447400 |

| Grifols UK Ltd | 0845 2413090 |

| Octapharma | 0161 837 3771 |

Appendix 3. Useful contact details

For advice regarding clinical management of cases or other queries relating to suspected cases during offices hours, please contact the Gastrointestinal Bacteria Reference Unit (GBRU), UK Health Security Agency, Colindale on 0208 327 7887 or email GBRU@ukhsa.gov.uk

The UKHSA duty doctor is requested to discuss all suspected cases with the on-call consultant microbiologist if calls are received during working hours.

Out of hours please contact the UKHSA duty doctor on 0208 200 4400 for all queries and advice.

For queries related to sending clinical samples and interpretation of toxin testing results:

Gastrointestinal Bacteria Reference Unit (GBRU)

UKHSA

61 Colindale Avenue

London NW9 5EQ

Telephone: 0208 327 7887

Please notify the laboratory when sending samples.

For queries regarding interpretation of serology testing, please contact the Respiratory and Vaccine Preventable Bacteria Reference Unit (RVPBRU) for advice.

Telephone: 0208 327 7887

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the expert review and advice received from:

- colleagues in the UKHSA Immunisation and Vaccine Preventable Diseases Division

- Dr Paul Stickings and colleagues at NIBSC

- Dr Abhishek Katiyar at Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust

Prepared by

Gayatri Amirthalingam, Gauri Godbole, Corinne Amar, Meera Chand, Norman Fry, Colin Brown, Joanne White, Charlotte Gower, Shennae O’Boyle.