Small Employer Offer evaluation

Published 20 July 2021

DWP research report no. 1003

A report of research carried out by Ipsos Mori on behalf of the Department for Work and Pensions.

Crown copyright 2021.

You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit The National Archives or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email psi@nationalarchives.gov.uk.

If you would like to know more about DWP research, email socialresearch@dwp.gov.uk.

First published July 2021

ISBN 978-1-78659-337-5

Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and Pensions or any other government department.

Executive summary

Introduction

This report presents findings from an evaluation of the Small Employer Offer (SEO), a policy delivered by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) between June 2017 and March 2019, to help people with disabilities and long-term health conditions move towards and into work. A key part of the SEO was the creation of Small Employer Adviser (SEA) roles, who worked with small employers to identify and fill work placements and job opportunities suitable for claimants with a disability or health condition.

The SEO evaluation consisted of qualitative in-depth interviews with SEAs, other Jobcentre Plus (JCP) staff, small employers and claimants with health conditions or disabilities who had been referred to, or started, an SEO work opportunity.

Academics in the Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research at Sheffield Hallam University undertook a literature review as part of this study to set out the broader context for this research.

Key findings

Existing literature suggests that a joined up approach to employment support, including a focus on employers, is crucial in helping move more disabled people towards and into work. The literature also notes that careful job matching tailored to an individual’s circumstances with on-going support for employers and claimants is a key driver for ensuring placements are successful for both parties.

The SEO policy design reflects many of the lessons learnt from existing literature. The SEO was successful in identifying a large number of work opportunities from employers. However, the initiative was less successful in filling these opportunities because there were limited numbers of ‘work ready’ eligible claimants.

The qualitative research found that employers with prior experience of working with people with health conditions and disabilities, felt that doing so was a positive practice. These employers felt confident accommodating and supporting people with a long-term health condition or disability.

For private sector employers it was important that any employee was motivated and understood the social norms of a working environment such as good time-keeping and showing initiative. Third sector employers were more likely to feel they could accommodate work placements from claimants who lacked awareness of the social norms of work and help them to learn these.

Private sector employers with no experience of hiring or working with candidates with a long-term health condition or disability were less likely to be confident about doing so in the future. These employers tended to have a narrow view of disability as a physical condition and found it more difficult to see how they could accommodate this.

Positive employer experiences of SEO starts were characterised by a perceived high standard of job-matching and when the claimant was viewed as completing the work to a high standard. Less successful SEO starts for private sector employers were characterised by claimants being unwilling or unable to complete tasks, placements being too short for the claimant to make a meaningful contribution to the organisation and claimants needing more support than the employer felt able to provide or was available from the SEA.

The qualitative research found that claimants’ health conditions or disabilities influenced the type of work they felt able to do or whether they felt able to work at all. It also led to indirect barriers, such as anxiety about re-entering the labour market due to extended time out of work, which could result in a lack of awareness and understanding of the social norms of a workplace, such as showing initiative and good time keeping.

Claimants reported that the SEO was most successful for them when they received intensive support from JCP staff tailored to their personal circumstances and health condition.

Positive effects reported by claimants who took up an opportunity through SEO included a sense of achievement, establishing a routine and improvements in confidence and soft skills such as communication and time-keeping.

The SEO experience also helped motivate claimants to look for more work and to develop a clearer idea of the type of roles they would like to pursue.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all those who gave their time to participate in this research and Janet Allaker from the DWP Disability Analysis Division, ESA Research Team for her help and support throughout the research process.

The authors

The authors of this report are:

- Joanna Crossfield, Research Director, Ipsos MORI

- Kelly Finnerty, Senior Research Executive, Ipsos MORI

- Katie Hughes, Research Executive, Ipsos MORI

- Professor Christina Beatty, Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research, Sheffield Hallam University

- Dr Tony Gore, Research Fellow, Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research, Sheffield Hallam University

- Catherine Harris, Research Associate, Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research, Sheffield Hallam University

Glossary

Access to Work (AtW)

A publicly funded employment support programme that aims to help people with a disability or health condition enter or stay in work. It can provide practical and financial support for people who have a disability or health condition. Support can be provided where someone needs help or adaptations in the workplace beyond the reasonable adjustments employers are required to make.

Community Partners (CP)

A specialist role within Jobcentre Plus at the time of the research. The role involved driving cultural change and challenging misconceptions, stereotypes and language about disability within Jobcentre Plus and upskilling and increasing capability of other Jobcentre Plus staff and employers.

Disability Confident (DC)

A scheme designed to help employers recruit and retain disabled people and people with health conditions for their skills and talent.

Disability Employment Adviser (DEA)

A role at Jobcentre Plus which aims to support DWP colleagues by developing their skills to understand the interaction between individuals, their health and disability and employment, to help to provide more personalised support, tailored to each claimant’s individual needs.

Employer Adviser (EA)

A role in Jobcentre Plus that involves engaging with employers to identify opportunities for claimants and promote DWP initiatives such as Disability Confident and the Small Employer Offer.

Employment and Support Allowance (ESA)

A type of benefit offering financial support to people who are out of work due to long-term illness or disability.

Personal Independence Payment (PIP)

A type of benefit offering financial support to help people aged 16 to 64 with some of the extra costs caused by long-term ill-health or disability (e.g. mobility and/or daily living costs). It is available to those in and out of work.

Reverse job-matching

A process of finding a suitable role for a claimant, by approaching employers about them, rather than presenting a claimant with a list of available roles.

Small Employer Adviser (SEA)

Jobcentre Plus employees who worked with small employers (those with fewer 25 employees) to identify and fill opportunities suitable for claimants with a disability or health condition as part of the Small Employer Offer.

Small Employer Payment (SEP)

A £500 payment given to employers in some areas who employed an eligible claimant through SEO for 12 weeks or longer, for 16 hours or more per week.

Work Coach (WC)

A role in JCP which works with claimants on a one-to-one basis to help them overcome work barriers.

Work Experience

A DWP initiative for claimants who do not have a recent history of work. Claimants volunteer for placements lasting between two and eight weeks and continue to receive benefits.

Work Psychologist (WP)

A role in JCP which provides specialist advice on the implications of specific health conditions or disabilities. Work psychologists provide support to both JCP staff and directly to claimants.

Work Trial

A DWP initiative which offers claimants unpaid work trials that are linked to a paid job vacancy. The potential employee undertakes the job for up to 30 days (duration agreed in advance, typically one week) and continues to receive their benefits. The claimant must meet eligibility conditions and volunteer to take part.

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Explanation |

|---|---|

| AtW | Access to Work |

| CP | Community Partner |

| DC | Disability Confident |

| DEA | Disability Employment Adviser |

| EA | Employer Adviser |

| ESA | Employment and Support Allowance |

| JCP | Jobcentre Plus |

| JSA | Job Seekers Allowance |

| PIP | Personal Independence Payment |

| SEA | Small Employer Adviser |

| SEP | Small Employer Payment |

| SME | Small and medium-sized enterprise |

| UC | Universal Credit |

| WC | Work Coach |

| WCA | Work Capability Assessment |

| WP | Work Psychologist |

Summary

Introduction

This report presents findings from an evaluation of the Small Employer Offer (SEO), a policy delivered by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) between June 2017 and March 2019, to help claimants with disabilities and long-term health conditions move towards and into work. A key part of the SEO was the creation of Small Employer Adviser (SEA) roles, who worked with small employers to identify work placements and job opportunities suitable for claimants with a long-term health condition or disability.

The SEO was part of a more personalised and holistic DWP approach to providing employment support for employers as well as claimants. This initiative aimed to increase engagement activities with small employers, to raise awareness of disability and support businesses to take on claimants with long-term health conditions or disabilities. Reverse job matching was a key element of SEO; SEAs worked with employers to identify jobs, work placements and work trials that were suitable to individual claimants’ needs.

The SEO evaluation consisted of a literature review and primary research; composed of qualitative, in-depth interviews conducted by telephone with Small Employer Advisers (SEAs), other Jobcentre Plus (JCP) staff, small employers (those with fewer than 25 staff) and claimants with health conditions or disabilities, who had been referred to, or started an SEO work opportunity. All employers interviewed had been involved with the SEO.

Academics in the Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research at Sheffield Hallam University undertook a literature review as part of this study. This involved reviewing the existing evidence on: the characteristics and barriers to work for claimants with long-term health conditions or disabilities; previous and current initiatives to support claimants into work; and the attitudes of employers and their role in supporting claimants into work. The evidence is summarised to provide the broader context of the evaluation.

Literature Review

The command paper Improving Lives: The Future of Work, Health and Disability (DWP and Department of Health, 2017) acknowledges that many people with long-term health conditions or disabilities miss out on the opportunity to benefit from the positive outcomes that can be derived from work. Having a more joined up approach to employment support which includes employers is important if the goal of having one million more disabled people in work by the end of 2027 is to be delivered.

The role of employers, as well as individuals and support workers is important. Many employers have very different understandings of the concept of disability and they need support to embed inclusive employment practices. Increasing employers’ awareness of disability may allay some of their fears or misconceptions about employing workers with long-term health conditions or disabilities (Rashid, 2017). Many employers also lack knowledge about relatively simple adaptations or flexible working practices which might be deployed to support workers with health conditions or disabilities to remain in work or take up employment opportunities. In the main, the perceptions of small employers are similar to those seen across all sizes of employers. The overriding concern of most employers is to find someone who they perceive could ‘do the job’ or who was the best person for the job (Davidson, 2011).

However, small employers often worry about the cost implications for their business which might be associated with making adaptations or allowances for an employee with a health condition or disability (Kelly, 2005). Promoting schemes such as Access to Work (AtW) which offers practical advice or financial support to businesses as well as workers may also encourage more small employers to open up job opportunities to people with long-term health conditions or disabilities (Dewson et al., 2009).

The literature review finds supporting evidence that the design of SEO reflected best practice seen in a range of wider initiatives:

- the need for individualised support tailored to an individual’s health condition or disability, capabilities and labour market experience

- a multi-layered approach, involving a range of specialist professionals working in partnership together, offers a better chance of success

- work-trials, work placements and voluntary work are all stepping stones towards entry to paid employment and assist in building confidence in employers as well as clients

- finally, careful job matching is key to ensuring that placements for both the client and employer are successful

Key findings

Research with staff

Research with Jobcentre Plus (JCP) staff found that the SEO scheme had been successful in identifying work opportunities from employers but had less success in filling these opportunities because there were limited numbers of work ready eligible claimants.

At the start of the SEO scheme, SEAs focused on employer engagement to generate opportunities. On finding that there were insufficient claimants ready to fill the available opportunities, SEAs increased their focus on helping claimants move closer to the labour market and prepare for work

Their work also included seeking roles to match individual claimants to, a process known as reverse job-matching.

SEAs worked closely with other colleagues to deliver SEO, particularly Employer Advisers (EAs) and Disability Employment Advisers (DEAs).

Research with employers

The research found that employers’ previous experiences of working with someone with a disability or long-term health condition strongly influenced attitudes towards doing so in the future, for the employers interviewed.

Social benefit organisations and charities interviewed were the most positive about recruiting candidates with health conditions or disabilities as this was usually part of their organisational purpose. Their funding models meant they were more likely to provide work placements than paid roles, but they felt able to support those furthest from the labour market to take steps towards paid work.

Employers with experience of working with people with health conditions and disabilities felt that doing so was a positive practice. These employers felt confident accommodating and supporting people with a long-term health condition or disability. However, for private sector employers it was important that any employee was motivated and understood the social norms of a working environment such as good time-keeping and showing initiative. Third sector employers were more likely to feel they could accommodate work placements from claimants who lacked awareness of the social norms of work and help them to learn these.

Private sector employers with no experience of hiring or working with candidates with a long-term health condition or disability were less likely to be confident about doing so in the future. These employers tended to have a narrow view of disability as a physical condition and found it more difficult to see how they could accommodate this.

A lack of experience of hiring someone with a health condition or disability meant it was more effective for JCP to approach this sub-group of employers about a specific candidate than the general concept of hiring someone with a health condition. This focus on a specific candidate helped employers to see how the individual could fit in to their workplace.

Positive employer experiences of SEO starts occurred when they perceived a high standard of job-matching or when the candidate was seen as being interested in the work (regardless of their experience), willing to learn and to fit in to the working environment.

Less successful SEO starts were characterised by placements being too short for the claimant to make a meaningful contribution to the organisation; claimants needing more support than the employer felt able to provide or was available from the SEA and attitudinal barriers from the claimant, for example, poor time-keeping, lack of proactivity or unwillingness to complete tasks. Whilst these attitudes and behaviours could be due to their disability or health condition, particularly for those with a mental health condition, private sector employers felt that they did not have capacity to support claimants in this way and needed work-ready candidates. Social benefit organisation or charities were more willing and able to support claimants who needed support to understand what was expected in the workplace.

Research with claimants

The claimants interviewed had a mix of health conditions, disabilities and levels of work experience, ranging from those with decades of professional experience to those who had never had a job before. However, all claimants had been away from the labour market due to their ill-health for at least a year.

The research found that a claimant’s health condition or disability influenced the type of work they felt able to do, or whether they felt able to work at all.

Their health condition or disability also led to indirect barriers, such as anxiety about re-entering the labour market due to extended time away or a lack of awareness and understanding of the social norms of a workplace. This could lead to a reluctance to accept a work placement/job or risked the experience of the placement being unsuccessful.

SEO was most successful for claimants when they received intensive support, tailored to their personal circumstances, and health condition. Claimants appreciated one-to-one regular and informal guidance from their SEA or work coach and liked seeing the same person as this helped build rapport and trust.

The support from JCP staff which claimants found most helpful depended on their proximity to the labour market. Claimants closer to the labour market preferred support directly related to preparing for work, such as help with CVs, finding and arranging suitable opportunities and accompanying them to interviews. Those further from the labour market reported that the most valuable type of support from JCP was on-going conversations to help them prepare for work and to address specific issues whilst in placements or work.

Claimants felt that the job-matching process needed to be tailored to their interests, skills and health condition and their future career goals. Claimants who had narrow views of the types of roles they would consider, needed help from JCP to see the benefits of different roles including temporary and voluntary placements.

Positive effects of SEO reported by claimants who took up an opportunity through the programme included a sense of achievement, establishing a routine and improvements in confidence and soft skills such as communication and time-keeping.

Claimants also reported that the SEO experience helped motivate them to look for more work and to develop a clearer idea of the type of roles they would like to pursue.

Conclusions

The research with employers suggests that experiences of working with JCP for employers could be improved through better candidate matching, meaning they only receive applications from appropriate candidates. Employers also appreciated regular communication from JCP, preferably with a named contact, and some requested more support before and during placements.

Charities and social benefit organisations have a valuable role in helping claimants move closer to work. Employers interviewed from this group described their commitment and capacity to providing support to candidates furthest from the labour market.

Claimants referred to SEO demonstrated a need for intensive coaching and support to help them prepare to return to the labour market. Support directly related to preparing for work, such as help with CVs and interview skills was beneficial but the claimants particularly benefitted from wider, softer support. For example, conversations about what to expect in the workplace and social norms of being at work, such as good time-keeping and showing initiative. These claimants also benefitted from help to think beyond their current expectations of the type of work which might be suitable for them or which they might be interested in. Future provision may need to allow for this more intensive work before job-matching can begin.

These conclusions dovetail with themes from the literature review about the need to take a holistic approach, working closely with both employers and claimants. The individual needs and preferences of both parties need to be considered in the process of improving employment prospects for those with health conditions or disabilities.

1. Introduction

This report presents findings from an evaluation of the Small Employer Offer (SEO) commissioned by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP).

1.1 Background

In 2017, the Department for Work and Pensions and Department of Health released a joint command paper Improving Lives: Work, Health and Disability. The paper acknowledged that many disabled people and people with long-term health conditions face multiple barriers and disadvantages to get into and remain in work. As a consequence, many miss out on the opportunity to benefit from the positive health and well-being outcomes that can be derived from work. The paper set an ambitious goal of having one million more disabled people in work by the end of the ten-year period to 2027. The vision was to create:

a society where everyone is ambitious for disabled people and people with long-term health conditions, and where people understand and act positively upon the important relationship between health, work and disability. (Improving Lives: The Future of Work, Health and Disability DWP and DoH, 2017).

A more joined-up approach across the welfare system, the healthcare system and the workplace was identified as being key to delivery. The paper notes that a more joined-up approach will facilitate tailored support for individuals with long-term health issues or disabilities. The paper also notes that enabling employers as well as individuals is seen as being crucial to success.

From April 2017, a £330 million package of funding was made available over four years to support these aims, known as the Personal Support Package (PSP). The PSP aimed to create transformational change by providing personalised and tailored support for people with disabilities and long-term health conditions and is delivered both by JCP staff and a range of external providers. As part of this package DWP introduced the Small Employer Offer.

1.2 Small Employer Offer

The SEO epitomised the aims of the Improving Lives: The Future of Work, Health and Disability command paper, to develop new ways of delivering employment support services which not only took into account individuals’ health and employment needs but also supported employers’ needs.

The key delivery mechanism for SEO were Small Employer Advisors (SEAs). They worked with small employers and claimants of Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) and the equivalent Universal Credit (UC) claimants. The SEA role aimed to expand engagement activity with employers with 25 or fewer employees (small employers) and break down preconceived ideas about employing people with long-term health conditions or disabilities. The SEAs encouraged small employers to create job opportunities, work trials and work experience placements which assisted people with long-term health conditions or disabilities to enter work. They advised employers on how they could make reasonable adjustments and adaptations, or how in-work support could be accessed, if a person with a health condition or disability was taken on. SEAs also raised awareness amongst small employers of schemes such as Disability Confident (DC)[footnote 1], Access to Work (AtW), the Fit for Work Service and the Small Employer Payment[footnote 2] (SEP).

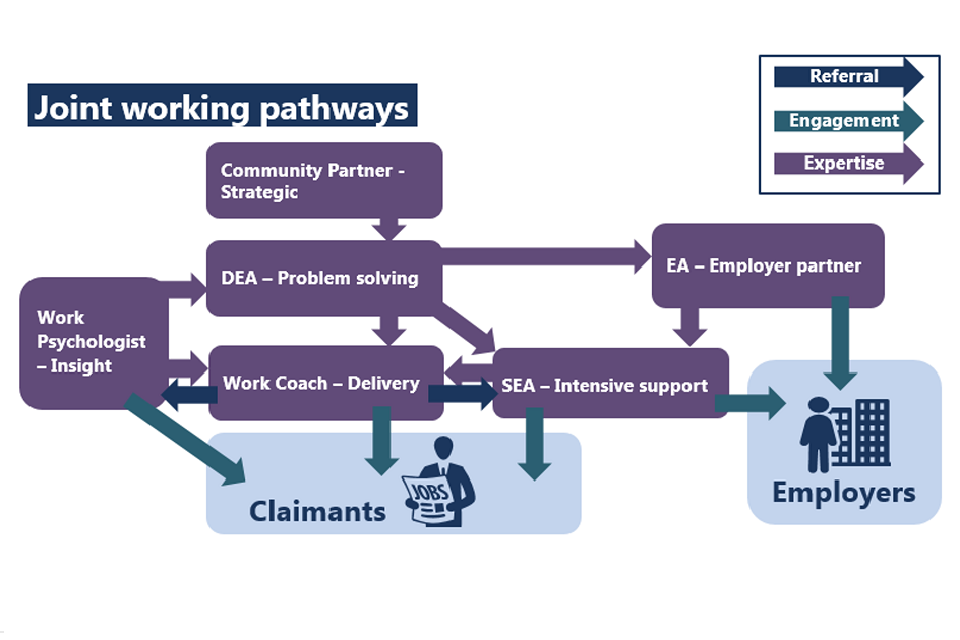

Reverse job-matching was used so that claimants’ health conditions, access needs and employment requirements were taken into account when identifying or creating potential work opportunities. This ensured claimants were matched to appropriate placements, jobs and employers. The SEA supported both the claimants and employers through the recruitment process including offering support for job interviews, induction, mentoring and in-work support. A range of other JCP roles also supported delivery of the SEO. These included:

-

Disability Employment Advisers (DEAs), who provide expert advice to JCP staff to raise awareness of specific disability issues. DEAs support and upskill work coaches (WCs), Employer Advisers (EAs) and other JCP staff such as Partnership Managers (PMs). They develop local training for WCs, raise awareness of local disability employment support options and advise on referrals for claimants.

-

Employer Advisers (EAs) support all sizes of business with tailored recruitment services. Their role includes helping employers to provide work trials, sector specific training or work experience for any claimants searching for work via JCP. EAs assist employers to match candidates to job opportunities and access schemes such as DC and AtW.

-

Community Partners (CPs) were employed by JCP to strengthen the understanding of disability amongst WCs, EAs and other JCP staff. They had lived experience or expert knowledge of disability and helped JCP staff tailor support to claimants’ needs. CPs provided advice, raised awareness, developed local training, highlighted disability employment support options and awareness of AtW.

-

Work Psychologists (WPs) support “harder to help” claimants and implement psychological interventions to assist them into work. WPs also work with JCP staff to advise them on appropriate support to help their claimants move closer to work.

1.3 Aims and objectives

The purpose of this evaluation was to gain an in-depth and rounded picture of how the Small Employer Offer (SEO) was operating, exploring the effectiveness of the SEO in supporting claimants towards or into work, engaging employers and matching claimants to employers and suitable roles.

As the SEO has now ended this report focuses on the learning that can be taken forward by DWP to inform future provision and engagement with employers and claimants.

There were three stages of research activity. Firstly, a literature review considered existing evidence around the characteristics and barriers to work for claimants with long-term health conditions or disabilities; previous and current initiatives to support claimants into work; and the attitudes of employers and their role in supporting claimants into work. Secondly, qualitative research interviews were conducted with JCP staff (including SEAs), claimants and employers. There were different aims and objectives for each stage of the qualitative research, outlined below.

The JCP staff research considered:

- organisation of JCP staff in relation to the SEO

- effectiveness of each role and how they worked together to deliver the SEO

- JCP staff suggestions for improvements in delivery of the SEO

Following on from this, the research with employers and claimants considered:

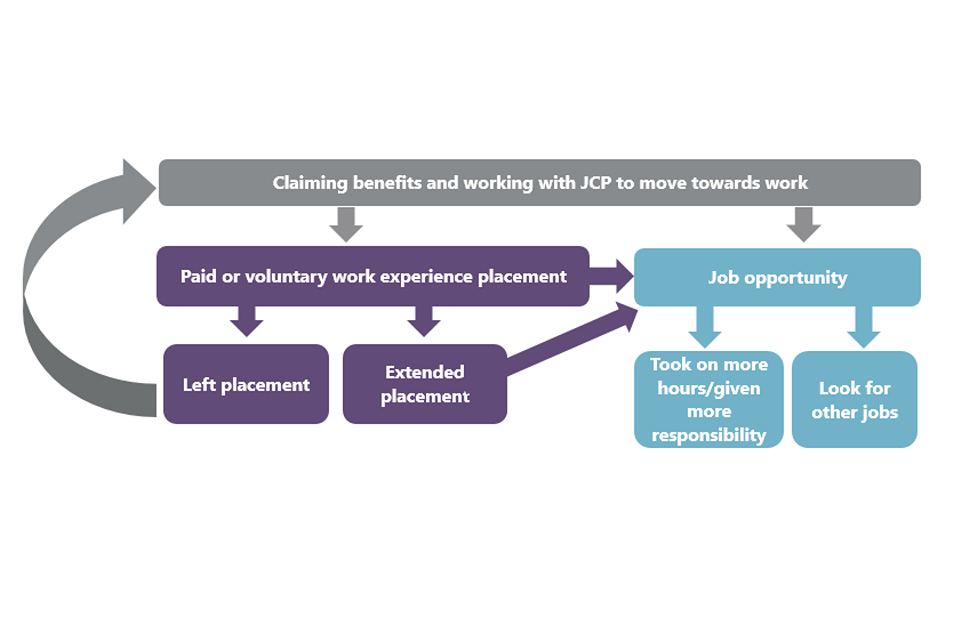

- claimant attitudes towards work and progression once in work, prior to and after participation in the SEO

- employers’ attitudes towards, and experience of, hiring employees with a disability or health condition prior to, and after, participation in the SEO

- experiences of employers and claimants including advice and support received from JCP before and after a start in an SEO opportunity

- outcomes as a result of the SEO and impact on behaviours and attitudes for both employers and claimants

1.4 Methodology

1.4.1 Literature review

Academics in the Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research at Sheffield Hallam University undertook a literature review as part of this study. This involved reviewing the existing evidence base and summarising the findings to set out the context for this research. This includes an overview of the characteristics and barriers to work for claimants with long-term health conditions or disabilities; previous and current initiatives to support claimants into work; and the attitudes of employers and their role in supporting claimants into work.

1.4.2 Research interviews

A qualitative approach was taken for the research to gain in-depth insight from the different groups involved with SEO.

The interviewees for this research were:

- Small Employer Advisors

- other Jobcentre Plus staff

- employers who had been approached about and involved in the initiative

- claimants who had been referred to, or started an SEO work opportunity

A sample of claimants and employers who had participated in the SEO, and JCP staff who had been involved in delivery, were provided by DWP for Ipsos MORI to recruit research participants from. A purposive sampling approach was adopted, whereby key quotas, such as experience of SEO and employers’ sector, for example, were set and participants were recruited according to these, using a screening document. Full details of the quotas are shown in Appendix A.

All interviews were conducted by telephone. Each interview lasted between 45 minutes to an hour and was conducted by an Ipsos MORI researcher using a discussion guide agreed with DWP. Separate discussion guides were developed for each of the four groups (SEAs, JCP staff, claimants and employers).

Small Employer Advisers

In total, 30 Small Employer Adviser (SEAs) were interviewed across 21 JCP districts (which cover local areas), in July 2018.

Other Jobcentre Plus staff

Fifty-five members of wider Jobcentre Plus staff were interviewed across six districts in August and September 2018. Jobcentre Plus roles that were interviewed were:

- Disability Employment Advisers (DEAs)

- Employer Advisers (EAs)

- Work Coaches (WCs)

- Community Partners (CPs)

- Work Psychologists (WPs)

1.4.3 Employers

Eighty-four small employers were interviewed between January and March 2019. For the purpose of the SEO and this research, small employers were defined as those with 25 employees or fewer.

Quotas were set on the level of employer engagement with the SEO. Secondary variables ensured a mix of sectors, areas and size of employers (fewer than 10 and fewer than 25) were included. Full details of the final sample profile can be found in the Appendix A, Table 1.

1.4.4 Claimants

Twenty-two claimants who had been part of the SEO were interviewed. These claimants all had long-term health conditions or disabilities and were in the Employment Support Allowance Work-Related Activity Group (ESA WRAG) or Universal Credit Limited Capability for Work group. These claimants had undergone a Work Capability Assessment and been assessed as being able to prepare for work. Research interviews were conducted in January and February 2019.

Claimants interviewed had been offered an SEO work opportunity (placement or paid job) and included those who had started and those who had declined the opportunity to participate. The sample included those with a range of health conditions including mental health conditions, learning disabilities and physical health conditions. The final sample profile of claimants can be found in the Appendix A, Table 2.

1.4.5 Analysis and interpretation of data

The interview data were analysed using a robust inductive[footnote 3] framework approach, as part of which the data was synthesised thematically and interrogated for patterns and relationships.

Qualitative research is illustrative, detailed and exploratory. It seeks to understand not only what people think and do but why this is the case. The volume and richness of the data generated allows for a detailed picture to be developed of the range and diversity of views, feelings and behaviours and this can be used to develop new concepts and theories. The findings in this report are intended to provide insight into the views of different SEO stakeholders but the purposive nature with which the sample was drawn and small number of interviews conducted means that they cannot be considered representative of these populations as a whole.

2. Literature review

This chapter provides contextual information relevant to the implementation of the SEO. It summarises key evidence from academic literature, government and third sector policy documents and administrative data to help to situate the findings emerging from the SEO evaluation. The following themes were explored:

- trends in disability benefit receipt and employment rates; barriers to work amongst people with long-term health conditions or disabled people

- historic and current initiatives, at both national and local levels, which seek to support people with health conditions or disabilities into work

- employers’ attitudes, support needs and experiences of employing people with long-term health conditions or disabilities

The SEO sat within DWP’s wider policy framework that takes a holistic approach to working with employers and claimants, reflecting the ethos of Improving Lives: The Future of Work, Health and Disability.

2.1 Disability benefit receipt and barriers to work amongst people with long-term health conditions or disabilities

2.1.1 Background

Substantial jobs growth following the 2008/09 recession led to record high employment rates and claimant unemployment[footnote 4] falling to pre-recession levels in recent years (Figure 1). Whilst non-disabled claimant unemployment (Jobseekers Allowance (JSA) and Universal Credit (UC) equivalent) has been responsive to the economic cycle, the trend in ESA and equivalent benefits[footnote 5] has not. Successive government policy documents acknowledge that these are issues that need to be tackled (21st Century Welfare DWP, 2010; and Improving Lives: The Future of Work, Health and Disability DWP and DoH, 2017). The government has recognised that raising employment rates amongst people with long-term health conditions or disabilities, as well as supporting them to remain in work, is seen as important to raising productivity in the workforce and supporting economic growth (DWP & DoH, 2017, p14).

Figure 1: Working age claimant unemployment and claimants on ESA or equivalent benefits, Great Britain, 1979-2018

""

Source: DWP administrative data[footnote 6]

2.1.2 The benefits system for claimants with health conditions or disabilities

The benefits system for claimants with health conditions or disabilities underwent a number of changes in the past decade. In 2008, ESA replaced Incapacity Benefit (IB) for new claimants unable to work due to ill health or disability. Under ESA claimants are required to undertake a Work Capability Assessment (WCA). If as a result of the WCA, the claimant is deemed to be unable to work on health grounds they are allocated to one of two groups:

- ESA Work Related Activity Group (ESA WRAG) - claimants are expected to undertake some preparation towards moving into work

- ESA Support Group - benefit receipt is unconditional for this group of claimants who are assessed as having the most severe health conditions or disabilities and are not required to undertake any work related activity, but can do so on a voluntary basis

Recent welfare reform includes the introduction of Universal Credit (UC) (DWP, 2015). After a WCA, UC claimants with long-term health conditions or disabilities are allocated to one of two conditionality groups:

- Limited Capability for Work (LCW) - equivalent to ESA WRAG. Claimants are not expected to look for work but are expected to take steps to prepare for work

- Limited Capability for Work and Work Related Activity (LCWRA) - equivalent to the ESA Support Group. Claimants are not required to undertake any work related activity.

2.1.3 The Disability Employment Gap

The Disability Discrimination Act 1995 (DDA) defines being disabled as having “a physical or mental impairment which has a substantial and long-term adverse effect on a person’s ability to carry out normal day-to-day activities”. The Equality Act 2010 (EA) defines being disabled as having “a physical or mental impairment that has a ‘substantial’ and ‘long-term’ negative effect on your ability to do normal daily activities”.

Ill health or disability is not always an insurmountable obstacle to employment. However, over the course of a year, disabled people who are in work are twice as likely to move out of work than non-disabled people (10% versus 5%); and if they are out of work they are nearly three times less likely to move into work than non-disabled people (10% versus 26%) (DWP and DoH, 2017, pp.82-83).

Consequently, disabled employment rates are much lower than for non-disabled people. The difference between the two is known as the ‘disability employment gap’. A number of recommendations, including the importance of supporting employers, were made in the Disability Employment Gap written by the Work and Pensions Committee in 2017:

The government will struggle to achieve its objective if it cannot bring employers on board, and enhance in-work support. Employment opportunities must be opened up to more disabled people and employers helped to see how taking on disabled people, and retaining employees who become disabled, could be good for their businesses. Some employers may need additional financial support and incentives to take on disabled people, and a great many could benefit from access to more practical, tailored, specialist advice at the point of need.” (Disability Employment Gap, House of Commons Work and Pensions Committee, 2017, p.3).

The ONS Annual Population Survey indicates that progress has been made in increasing the number of disabled people in employment and reducing the disability employment gap:

- between 2013 to 2014 and 2017 to 2018 disabled employment rates increased by 5.8 percentage points to 51.1% in Great Britain

- this compared to a 3.1 percentage point increase to 80.8% in the non-disabled employment rate between 2013 to 2014 and 2017 to 2018

- the national disability employment gap reduced over the period by 2.7 percentage points to 29.7%

- in 2017 to 2018, disability employment rates were highest in the South East, South West and East regions and the lowest in the North East, Wales and Scotland; ranging from 58.4% in the South East to 44.3% in the North East

- in 2017 to 2018, the disability employment gap was nearly 20 percentage points higher in the North East (44.3%) than in the South East (24.1%) or South West (25.2%)

2.1.4 Barriers to work for people with health conditions and disabilities

Even with strong economic growth, multiple challenges exist to re-engaging claimants with health conditions or disabilities with the labour market (Beatty and Fothergill, 2013). Extensive literature highlights a number of common barriers to work for this group including poor health, skills, qualifications and the lack of recent labour market experience.

Health conditions and disability

An Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) funded survey of 3,500 incapacity benefits claimants in Britain undertaken in 2008 found that 80% reported that their health limited their ability to work ‘a lot’ or that they ‘couldn’t do any work’; around half expected their health condition to deteriorate; and only 5% expected it to get better (Beatty et al., 2009). Three-quarters of respondents who said that they would like a job thought that employers would regard them as ‘too ill or disabled’ or ‘too big a risk’ to employ.

Employees with disabilities or health conditions tend to have limited awareness of their rights in terms of reasonable adjustments (Adams and Oldfield, 2012). This study also found that employees’ judgements are often based on what they feel their employer will be able to afford and they state that smaller companies may be impacted more negatively than larger ones.

Perception of health was found to be an “overwhelmingly important” factor in determining whether participants in the Pathways to Work programme returned to work (Becker et al., 2010). Participants in this study most frequently cited poor health as a barrier to work and those with ‘good or improving’ health were far more likely to return to work. Oakley (2016) found that those with an improving health condition are twice as likely to move into work.

The negative impact of disability also affected the quality of employment individuals accessed (Konrad et al., 2013). This issue is not merely confined to the UK; thus, a review of the empirical evidence on disability and the labour market across European countries, America and Australia concluded:

Regardless of country, data source or time period disability serves to reduce labour market prospects.” (Jones, 2008, p.405).

Mental health conditions

The Annual Population Survey indicates an increasing proportion of claimants report mental and behavioural health conditions: rising from 35% of claimants in 2000, to 43% in 2007 and 51% in 2018. A detailed analysis of the differential employment outcomes of individuals indicated that those with a mental health condition were around 30% less likely to move into work than those with other health conditions or disabilities (Oakley, 2016). Many other studies also highlight poor mental health as a key barrier to work (Hale, 2014; Benstead and Nock, 2016). Claimants often face complex multiple mental health issues, such as depression or anxiety, in addition to a primary diagnosis for a physical health condition (Kemp and Davidson, 2010; Lindsay and Dutton, 2012).

Evidence suggests that greater awareness of mental health issues and better recruitment practices are needed amongst employers. A DWP study of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) found that small employers are sometimes reluctant to employ people with a mental health condition (Davidson, 2011). Some of the SMEs interviewed also voiced concerns that this might be difficult to manage in their workplace.

Multiple disadvantage in the labour market

Additional factors known to be associated with lower employment rates are prevalent amongst people with long-term health conditions or disabilities. These include: having an older age profile; low skills or qualifications; previous employment in a manual job; long-term detachment from the labour market; and lack of experience or relevant experience for the types of jobs which are available (Beatty and Fothergill, 2012; 2013). A short summary of key evidence is presented here.

Age

ESA claimants have an older age profile than the population; half are aged 50-64 compared to 26% of JSA or UC equivalent claimants or 30% of working age population as a whole (DWP Benefits Data, NOMIS and Stat-Xplore; ONS mid-year population estimates, 2018).

In the UK, older people with work-limiting conditions are less likely to move into work than younger people (Oakley, 2016).

Qualifications and skills

A DWP survey of disabled people claiming Job Seekers Allowance (JSA), ESA or IB indicates that 41% of disabled people seeking work reported a lack of qualifications/skills/experience as a barrier to work (Cole, 2013).

2015 LFS data for GB indicates that 27% of ESA claimants aged 18-64 had no qualifications; this compares with 19% of JSA claimants, and 5% of employed people (Beatty et al., 2016).

Individuals with work-limiting health conditions or disabilities and who have low (below A Level) or no qualifications are less likely to move into work (43%) compared to those with higher qualifications (61%) (Oakley, 2016).

50% of ESA claimants’ previous employment was in a low skill job; this compares with 28% of those currently in employment (Beatty et al., 2016).

Duration out of work

Two-thirds of ESA or UC equivalent claimants have been on benefit for over two years compared to 10% of JSA claimants (DWP, 2016).

Those with work-limiting health conditions or disabilities who have been out of work for less than six months are eight times more likely to move into work than those out of work for over five years (Oakley, 2016).

2.2 Historic employment support initiatives for claimants with health conditions or disabilities

2.2.1 Background

Various employment support initiatives for those with health conditions or disabilities have been tried and tested at different points in time. Previous initiatives tended to emphasise enhancing employability through traditional employment support and, at times, this was combined with health interventions. More recently, there has been a move towards tailoring support to meet not only individual needs but increasingly the needs of the employer. These include initiatives that offset additional costs borne by an individual or employer in order to support a transition into work. Other initiatives aim to raise awareness amongst employers of the benefits of employing disabled people. This section provides a brief overview of both historical and recent initiatives.

2.2.2 Previous national DWP initiatives

A brief overview of previous national DWP initiatives relevant to the SEO is provided below.

New Deal for Disabled People (NDDP)

Introduced nationally from 2001, this voluntary programme operated through a network of Job Brokers to support employers and help people move into sustained employment. The evaluation reports indicate that NDDP had mixed success with employers in terms of building sustained relationships with them and was more targeted at supporting the individuals enrolled on the programme (Aston et al., 2005).

Pathways to Work (PtW)

This initiative, piloted in 2003 and launched in 2007, sought to address the health‐related and personal barriers of claimants with long-term health conditions or disabilities to help them move closer to work. PtW included compulsory work-focussed interviews plus a range of voluntary options, including training, referral to NDDP; and a back-to-work credit of £40 a week for the first year for those entering low-paid employment. Another voluntary element of PtW was the Condition Management Programme (CMP) which emphasised awareness, reassurance and advice rather than directly treating health conditions (Kellett et al., 2011). There is some evidence that cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) used within the CMP element of PtW had some positive effects on participants’ well-being, perceptions of health, confidence and readiness to work but the findings for positive employment outcomes is less clear-cut and moving directly into paid employment was not a common outcome (Dibben et al., 2012 Secker et al., 2012; Nice and Davidson, 2010). Overall, there is mixed evidence on the degree to which PtW and the CMP element was successful (Bewley et al., 2008; National Audit Office, 2010; Beatty et al., 2013).

Work Programme (WP)

The WP replaced PtW in 2011 and provided support for the long-term unemployed as well as incapacity benefit claimants. It supported claimants’ labour market activity (such as job search) and tackled employability issues, such as skills gaps. The DWP evaluation of WP (Newton et al., 2013) suggests that in the early years of the WP contract providers made little effort to deliver sophisticated or specialist services to claimants with health conditions or disabilities. However, more specialist services were developed over time. The slower rate at which incapacity benefit claimants found work compared to the unemployed claimants also influenced the contractors’ targeting of resources (ERSA, 2013).

Work Choice (WC)

WC was introduced in 2010 as a specialist disability employment programme for those who could not be supported through mainstream employment programmes. WC provided a flexible programme of personalised pre- and in-work support for claimants, the use of the ‘place and train’ model of supported employment, and support for employers which included financial incentives for some. The initial evaluation indicates that widening employer engagement activities was seen as important and that employers were positive about the support they received. Many employers suggested that they would probably not have employed claimants without the support received and that this was necessary to maintain ongoing employment (Purvis et.al., 2013).

2.2.3 Local initiatives

Local initiatives have often tested more joined-up local approaches to delivery with employment support services, employers and other partners as well as testing financial incentives for employers. Some examples of local initiatives with detailed evaluations are explored below.

Northern Way Worklessness Pilots

The Northern Way was a collaboration of three northern Regional Development Agencies. They initiated a programme of local interventions between 2005 and 2008 in ten areas with high incapacity benefits rates. Participation was voluntary. Some pilots adopted a ‘health-centred’ approach whilst others opted for an ‘employment-focused’ approach. Pilots sought to enhance skills, enable volunteering, boost confidence and improve social interaction skills of claimants.

The evaluation concluded that flexible and creative approaches that were attuned to local circumstances assisted incapacity benefits claimants to move towards employment. A combined health and employment-related approach which was tailored to individual needs was seen as the most beneficial model (ECOTEC Research and Consulting, 2009). The evaluation highlighted successful aspects of employer engagement and support, many of which echo features embedded within the SEO. These include:

- raising awareness amongst employers about the benefits of employing people with health conditions and reassuring them around specific concerns were both essential first steps to getting them on board

- making use of existing employer engagement activity infrastructure rather than duplicating established approaches

- work tasters and placements, and in work transitional support were valuable for both the prospective employee and the employer

- initial wage subsidies can also persuade some employers (and especially SMEs) to take on claimants with health conditions or disabilities

Aim High Routeback

A detailed local evaluation was undertaken of the Aim High Routeback initiative which was one of the Northern Way Worklessness Pilots in Easington (Frontline, 2008). This initiative deployed a ‘health-first’ approach involving partnership working between health professionals and employment support professionals. One in three of the claimants subsequently found work which was well above the average for the Northern Way pilots as a whole. Success factors included the voluntary nature of the scheme, the flexibility of support available and the team-based approach to delivery.

Project Search

Project Search programmes run in over 40 localities across the UK and focus on working with employers to provide supported internships for people with learning disabilities. If a suitable ‘job match’ takes place, then claimants have the opportunity to be employed on a more permanent basis.

The UK evaluation covered 17 projects and suggests that around half of the claimants moved into paid employment (Kaehne, 2016). Projects appeared to work less well with small employers who had limited capacity and resources to: develop positive relationships with the interns; work alongside external job coaches; or the ability to offer a permanent post at the end of the training period.

2.2.4 Summary

The evidence from previous national programmes and local initiatives in the UK is mixed both in terms of approaches taken and employment outcomes achieved. There are some common themes which emerge over time from across the evidence. First, holistic approaches which are delivered by a range of professionals from different disciplines working in partnership tend to be viewed more positively by claimants. Often this includes those delivering psychological therapies, health professionals, and employment support workers. Second, individualised support which is tailored to a participant’s health condition or disability, capabilities and labour market experience rather than a ‘job first’ approach are viewed as being more beneficial to both claimants and employers. Third, increasing employer engagement and support for the employer, including after a placement has been made, is seen in a positive light. Specifically targeting SMEs for support is not mentioned by any of the interventions and there is almost no evidence on the effectiveness of interventions in relation to the size of employer. Finally, the range of schemes demonstrate that, even with support, delivering sustained employment outcomes for claimants with long-term health conditions or disabilities is difficult. Claimants often require long-term and intensive support to achieve a job outcome. However, targeted interventions often achieve wider benefits such as an improvement to the health and well-being of the claimants.

2.3 Current national initiatives which include employer engagement

There are a number of current initiatives which aim to build on lessons learnt from previous schemes by taking a more holistic and individualised approach to employment support. They aim to increase engagement with employers as well as offering support to individuals in order to increase employment amongst disabled people or those with long-term health conditions.

Work and Health Programme (WHP)

The WHP provides targeted contracted employment provision to offer more intensive, tailored support to meet individuals’ needs. The scheme replaces WP and WC and is voluntary[footnote 7] for new ESA WRAG or UC equivalent claimants (House of Commons Library, 2018a). It was launched in November 2017 and takes a joined-up approach to provision to tackle the labour market and health barriers of claimants. Employer engagement is increasingly recognised as an essential component of WHP. This includes developing relationships with employers to open up job opportunities to people with health conditions or disabilities as well as supporting employers to increase retention of claimants with health issues they take on through the scheme.

Disability Confident (DC)

Launched in 2016, DC supports employers to gain the techniques, skills and confidence they need to recruit, retain and develop people with long-term health conditions or disabled people in the workforce. As of September 2019, 13,600 organisations were signed up to the scheme. The three levels of engagement include:

- being ‘Committed’ to follow good practice and take actions that make a difference

- ‘Employer’ organisations complete an action-focused self-assessment taking on ‘core actions’ and at least one ‘activity’

- and ‘Leader’ organisations are validated by a third party and act as a champion for disability employment within the local and business communities

A survey of DC employers found that half had recruited one or more individuals with a disability or long-term health condition as a result of joining the scheme (DWP, 2018). However, smaller employers were less likely to have done this than larger organisations: 30 % of micro-employers, compared with 47 % of small employers, 50 % of medium employers and 66 % of large employers[footnote 8].

Overall, 88 % of employers reported that they had made changes to their recruitment practices for disabled people as a result of joining the scheme. A quarter said that they were unlikely to have made these changes without DC; rising to a third for micro employers, suggesting it was particularly important for small businesses. Smaller employers were also more likely to report that they had to started implementing practices and activities within the following 12 months.

Access to Work (AtW)

Access to Work provides advice and a financial grant for practical support to help people overcome work related barriers due to disability. It is available to people with a disability or health condition who are already in paid employment or those about to start or return to paid employment. AtW provision includes individual assessments which explore workplace barriers to employment and recommend how these can be overcome. For some, this results in provision of advice and/or a grant which helps with the cost of practical support for both the employee and the employer. Access to Work statistics show that in 2018/2019, 32,010 people received AtW provision a 15% increase from 2017/2018.

Evaluation evidence shows that smaller employers were less aware of AtW than larger ones, and that employers learnt a lot from the assessment process about how to make reasonable adjustments (Sayce, 2011; Dewson et al., 2009). Employers felt that raising awareness of AtW amongst small employers would help to allay their fears about the costs of employing someone with a long-term health condition or disability (Dewson et al., 2009).

DWP qualitative research on AtW indicates that both employers and individuals were mostly positive about the scheme (Adams et al., 2018). Employers reported that they had employed staff with health conditions or disabilities that they may not have without the scheme and that this was especially notable amongst small employers. DWP research indicates that costs for adjustments due to limited cash flow may be an issue for some small employers (Dewson et al., 2009). Small businesses could also benefit from a more flexible approach to AtW which may include part-funding of cover for significant periods of sick leave for employees with fluctuating conditions (Sayce, 2011). People with disabilities or health conditions who had claimed AtW and were working in SMEs reported supportive, rewarding and trusting relationships with their employers (Adams and Oldfield, 2012).

2.4 The role of employers

2.4.1 Background

Support to assist people with health conditions or disabled people into work often focuses on supply-side initiatives such as improving skills or job search activities (Cornell University Employment and Disability Institute, 2013). The role of employers and demand-side barriers which impede disabled people from progressing into paid work are often overlooked (Lindsay and Houston, 2011). However, research shows that employer recruitment practices; stigma and discrimination; physical challenges around access; and availability of suitably flexible job opportunities also act as barriers to work (Roulstone and Barnes, 2005; Barnes et al., 2010). There is an increasing recognition that employers have an important role to play if disability employment rates are to be increased:

The Government has little prospect of halving the disability employment gap unless employers are fully committed to taking on and retaining more disabled people. (House of Commons Work and Pensions Committee, 2017, p.41)

Evidence on employer attitudes, barriers to employing people with long-term health conditions or disabilities, and their support needs are now considered. However, it should be noted that the evidence tends to refer to employers in general rather than specifically in relation to the size of the business. A DWP qualitative study of SMEs attitudes confirms this:

..despite the prevalence of SMEs in the UK economy, relatively little is known about their recruitment procedures and how these might relate to the employment of disabled people. (Davidson, 2011, p.1)

2.4.2 Employer attitudes

Numerous studies explore employer attitudes in relation to recruitment practices, retention polices or employment of people with specific types of health conditions. The evidence is relatively mixed depending on the size of employer, type of employment and type of health condition or disability. A DWP commissioned survey of employers (Young and Bhaumik, 2011) indicates:

- nearly nine out of ten employers recognised that they have a role to play in encouraging health and wellbeing amongst their staff

- many employers actively supported staff at risk of leaving work but only just over half agreed that the financial benefits outweigh the costs

- this was particularly the case for SMEs, who were less likely to provide occupational health services to employees: only 16% of micro employers and 33 % of small employers provided access to occupational health services compared to 85% of large employers

Employer concerns include the possibility that future health difficulties may result in financial pressures for the business. Having a better understanding of the health issues faced by employees may allay their concerns about the scale or costs of adaptations that might be needed (Rashid et al., 2017). A study on mental health and employment confirms employers are generally open to taking on employees with mental health conditions but that larger employers find it easier to make adaptations (Sainsbury et al., 2008).

2.4.3 Small and medium sized employers

DWP commissioned a study on SME attitudes and recruitment procedures for disabled people or people with long-term health conditions (Davidson, 2011). The resultant literature review highlighted that for SMEs barriers to recruiting disabled staff include:

- perceptions that disabled people may be more of a health and safety risk than non-disabled people

- perceptions that disabled people may be less productive than non-disabled people; that efficiency may be reduced; and that there may be disruption in the workplace especially for those with ‘severe’ impairments

- narrow perceptions of disabled workers, i.e. as wheelchair users (Disability Rights Commission, 2004)

- a reluctance to challenge discriminatory attitudes of wider staff (Duckett, 2000)

- concerns about making workplace adjustments, e.g. financial implications and resentment from other staff (Kelly et al., 2005)

The study also included qualitative interviews with 30 SMEs which indicate that their perceptions reflect similar views voiced by other sized businesses in previous studies. Some used relatively narrow definitions of disability associating it with physical conditions, whilst others included all health conditions or degrees of severity. This echoes findings from a systematic review which highlights small employers’ wide ranging views on disability (Beyer and Beyer, 2017). The respondents within the Davidson study depict common concerns as:

- lacking awareness and knowledge of health conditions which makes it difficult to judge whether an applicant can perform tasks associated with a specific role

- their preference to reduce hours worked to help disabled employees cope in the workplace, rather than changing the range of tasks involved in a given role

- worries about fluctuating conditions which may result in unpredictability, absence, disruption to workplace routines or managing rest of the workforce

- the costs involved in making adaptations and/or purchasing appropriate equipment for one recruit or that this might be wasted if the person left their post

- uncertainties due to: the suitability of the built environment; risks to productivity; risks to the disabled person, other staff or customers - especially where the work was considered to be relatively dangerous; and wider cost implications

The main concern of most employers in the study was to find someone who they perceived could ‘do the job’ or who is the best person for the job. Many employers agreed that disabled workers can be as productive as non-disabled workers, provided they are in the right job. In general, SMEs focused on attaining flexibility, maintaining productivity, lowering their costs and increasing profit margins by finding the best person for the job. Some SMEs recognised the benefits of employing disabled people including: bringing diversity and a different viewpoint, enhancing employer reputation, showing employers’ commitment to staff. Some SMEs felt that larger employers would be better placed to take on disabled workers as they could exploit greater economies of scale and a greater volume of job vacancies.

SMEs within the study indicated a range of ways that they could be supported including:

- matching disabled applicants with suitable opportunities

- information on health conditions and capabilities of applicants

- education for wider workforce to prevent discrimination

- work trials to assess capability and suitability

- financial help for the business for adaptations or specialist equipment

- increasing awareness of DWP policy initiatives amongst SMEs

2.4.4 Supporting employers to employ people with developmental disabilities

The role of employers in achieving successful employment outcomes with disabled candidates is frequently overlooked (Nicholas et al., 2015) but several studies highlight the benefits of supporting employers to employ people with developmental disabilities. Canadian research shows that this can be instrumental in helping individuals with developmental disabilities to gain employment (Rashid et al., 2017). This includes using employment support workers in building employer capacity to assist people with autism to transition into and maintain work.

Close liaison between employment support workers and employers is associated with better outcomes. Claimants with employers who received employment support had higher salaries, greater job progression, and were employed for longer than those with employers not receiving support (Nicholas et al., 2015). Successful support strategies include building on existing relationships with employers, maintaining contact and listening to employer concerns after hire, as well as providing job coaching to the individual (Migliore et al., 2012).

A British systematic review highlights the benefits of supporting employers to take on people with learning disabilities (Beyer and Beyer, 2017). The evidence indicates employers have limited awareness of disability and may be resistant to hiring people with learning disabilities. Concerns are associated with the perceived additional costs of: hiring; making reasonable adjustments or accommodations; additional supervision; loss of productivity; difficulty in carrying out job terminations if needed; and potential employees having skill deficits (Peck and Kirkbride, 2001; Konrad et al., 2013).

Positive disability employment outcomes stem from specific employment support services which engage positively with the worker and the employer (Lengnick-Hall et al., 2001). Support which continues in the workplace remains important in delivering positive work experiences. Employers with experience of employing people with a learning disability (including work placements) are more positive in valuing their contribution to the company.

2.4.5 Financial incentives for employers

Many small employers voice concerns about additional costs which may be associated with employing staff with long-term health conditions or disabilities (Davidson 2011). Potentially, financial support which offsets these costs may provide an incentive for some to offer work opportunities to disabled workers. However, the evidence that this works is relatively mixed. Whilst some SMEs report that financial help to offset these costs may be beneficial, many express an overriding concern is to get the right person who could ‘do the job’ and meet their business needs. Small employers state that for employment or a placement to work, the right job needs to be available which is appropriate for the candidate. These factors appear to outweigh the potential for financial incentives. The Routes to Work initiative in Barrow was part of the Northern Way Pilots and included a substantial six month jobs subsidy. Again, employers stressed the crucial importance of people’s aptitude and attitude for the job on offer (ECOTEC Research and Consulting, 2009). On the whole, employers thought that a wage subsidy would not make a difference to their decision to employ somebody. A small number of respondents expressing an interest in a wage subsidy thought it could be useful to cover a high-risk initial training period or as a means of offering short-term work placements. However, those who took part in the initiative were almost all large firms (or branches of bigger organisations operating nationwide).

There does not appear to be clear evidence on the benefits of financial support offered to some employers or the use of a wage incentive for young people within the Work Choice programme (Purvis et. al., 2013). One Work Choice provider offered incentives in various forms, including a payment of £500 for employers who employed a participant. However, this had not been taken up and as a result they had steered away from using financial incentives.

A study of wage subsidies for disabled workers in Sweden (Gustafsson et al., 2014) indicates that employer attitudes and matching candidates to appropriate positions are important factors in determining whether financial incentives work. Employers with positive earlier experiences of people with disabilities were more willing to consider people with disabilities for jobs, but for hiring to take place, there must also be a match between the right person and the right job. Employers saw substantial wage subsidies (in this case up to 80 % of the wages) as important and stated they would probably not have hired the person without it. All employers emphasised the advantages of cheaper labour and the subsidy was seen as compensation for reduced productivity. This was especially the case amongst small employers as the overall wage reduction offered by a substantial wage subsidy was seen as extremely important to offer them a competitive edge.

2.4.6 Reverse job matching

The SEO offered a personalised approach to working with the claimant and employer to reverse job match candidates to employers which could offer opportunities that are appropriate to the individual’s health condition, experience, needs and interests. The SEA may have approached an employer that they already had a relationship with and who they knew was open to the idea of offering an opportunity to a person with long-term health condition or disability. Alternatively, the SEA may have sought out a potential employer in a particular sector and engaged with them to see if they were open to offering a placement or work experience to a disabled claimant.

There is relatively limited literature available on the benefits of reverse job matching especially in relation to small employers. However, many of the studies discussed here stress the importance of ensuring that an appropriate job match, which is suitable to both the employer and the claimant, is needed if a placement is to be successful. This view is proffered in many instances by both employers and employment support workers. Small employers report that having support which matches disabled applicants with suitable job opportunities is an important requisite of any successful placement (Davidson, 2011). Careful job matching is a key feature of successful projects which offer tailored employment support for jobseekers with mental health conditions and learning difficulties (Roulstone et. al., 2014). Finding a suitable ‘job match’ is also seen as the basis for work placements to have the potential to turn into more permanent positions (Kaehne, 2016). A Swedish study of wage subsidies for disabled workers (Gustafsson et al., 2014) also highlighted the importance of matching candidates to appropriate positions if placements are to be successful.

2.4.7 Summary

The role of employers is frequently overlooked in the design of employment initiatives which support people with long-term health conditions or disabilities into work. And yet the research considered here indicates that employer recruitment practices, stigma and discrimination, employers concerns about additional costs or productivity of staff, and the willingness of employers to offer suitable or flexible job opportunities can all act as barriers to work for this group. Therefore, there is an increasing recognition that more holistic approaches which include employers are needed if disability employment rates are to be increased. Existing research highlights that there are a number of approaches that may be beneficial. These include - increased engagement with employers to raise awareness and understanding of health conditions and disabilities faced by potential employees. Assisting employers to understand how relatively straightforward adaptations can be made to support an employee, and supporting them with the costs involved, may also allay their concerns about the scale or costs of adaptations that might be required. The importance of matching candidates to suitable job opportunities is also shown to be beneficial to employers and helps meet their primary concerns that they get the right candidate who can do the job. Evidence on small employers specifically is relatively lacking. However, most of the attitudes identified amongst SMEs seem similar to those of employers in general. However, due to their size, they frequently voice concerns about their capacity to absorb additional costs, provide additional support or manage the impact of fluctuating health conditions all of which may make them risk adverse and deter them from employing staff with long-term health conditions or disabilities.

3. Research with Jobcentre Plus staff

This chapter presents findings from research with JCP staff; with SEAs and other members of JCP staff: Employment Advisors (EAs), Disability Employment Advisors (DEAs), Work Coaches (WCs), Work Psychologists (WPs) and Community Partners (CPs).

This chapter discusses the purpose of the SEO and the SEA role and the roles and relationships between other JCP colleagues in relation to the delivery of the SEO.

3.1 The SEA role and delivery of the SEO

The SEA role was created to work with small employers to identify work placement and job opportunities for claimants with disabilities and/or long-term health conditions. There were approximately three SEAs in each JCP district when the research was conducted[footnote 9].

The SEA role changed over time. They began with an initial focus on employer engagement, to generate employment opportunities. However, SEAs reported identifying more work placement and job opportunities than there were claimants eligible and ready to take these up. As a result, their focus shifted more towards supporting claimants to move closer to the labour market and increased reverse job-matching.

Through reverse job-matching, SEAs sought roles based on claimants’ interests and skills, rather than matching claimants to existing roles. SEAs felt this approach increased the likelihood of the claimant taking up the role and was seen as creating a better impression on employers than sourcing roles which they then may not have anyone to fill. In some cases this led SEAs to approaching larger employers if a suitable opportunity was not available from small employers.

SEAs also started providing intensive employment support for claimants as they felt this was a gap in JCP provision for this claimant group. There were two reasons for this; firstly, SEAs perceived that work coaches did not always have the skills or capacity to provide the intensive support they felt these claimants needed. Secondly, SEAs suggested that changes to the role of the DEA were a factor because DEAs were no longer working directly with claimants[footnote 10]. In response to this perceived gap in support for claimants, SEAs took on additional claimant facing responsibilities to support their wider team. In time, SEAs described their role as a being a conduit between employers and claimants; a means of helping claimants with health issues and disabilities to get into work and to promote other DWP initiatives such as Disability Confident to employers.

There was a relationship between how SEAs perceived their current role and the previous role they had held at JCP. For example, an SEA who had previously had an employer facing role, such as an EA, might focus more on the employer aspect of the SEO. Those who had previously been in a claimant facing role focused more on claimants. Other SEAs described an equal focus on both parties. These differences are reflected in the quotes below:

I see the Small Employer Offer as a way of helping people with health issues and disabilities to get them into work. (SEA)

For me the SEO is being the in-between link for client and the employer. (SEA)

The Small Employer Offer is to promote Disability Confident to smaller employers locally. (SEA)