Salt targets 2017: progress report summary

Updated 18 January 2019

1. The problem with salt

As a nation, we are consuming too much salt, 8 grams a day on average. This is a third higher than the government’s maximum recommendation of 6 grams per day for adults. To put that into perspective, 6 grams is equivalent to one teaspoon. This is concerning because excess salt can lead to high blood pressure, which triples the risk of heart disease and strokes, 2 of the leading causes of death for adults in the UK.

With added salt in many of our foods and drinks, it’s easy to see how people are consuming too much without realising it. In fact, about four-fifths of our intake comes from salt already in the foods we buy – without us even adding any during cooking or at the table.

This is why salt targets were first introduced by the government in 2006, challenging the food industry to reduce salt in everyday foods such as ready meals, cooking sauces and processed meat – as well as foods such as biscuits and cakes, which despite being sweet in taste, can be surprisingly high in salt.

Salt reduction programme

1.1 Results

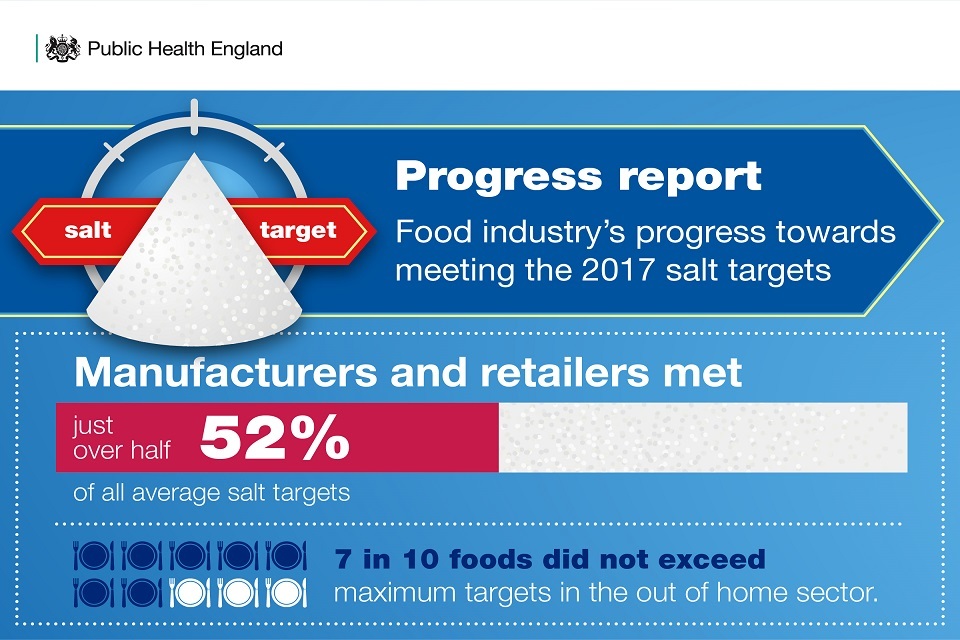

PHE has published a report on the food industry’s progress towards meeting the 2017 targets (set in 2014). The categories for all sectors (retailers, manufacturers and out of home businesses) cover 28 specific food groups contributing the most salt to the population’s intake and were set to be achieved by December 2017.

These include a mix of average and maximum targets because:

- maximum targets motivate businesses to look at products that are high in salt, benchmark them against competitors and make reductions

- average targets aim to lower the overall salt levels in a sub-category while maintaining flexibility to allow for variation between individual products (for example ready meals)

The report shows that just over half (52%) of all the average targets set were met by manufacturers and retailers.

Performance of food categories varied considerably for manufacturers and retailers. Some categories such as breakfast cereals and stocks and gravies are meeting all average targets. Others, such as meat products, have failed to meet average targets and have more than 4 in 10 products with salt levels above maximum targets. On average, retailers performed better than manufacturers for both the average and maximum targets.

Specific salt reduction targets per serving were also developed for 11 food categories, based on the most popular out-of-home foods, as well as a specific target for children’s meals. These targets were set to take account of generally higher levels of salt in products than those bought to be eaten at home reflecting less initial progress on salt reduction.

As with retailers and manufacturers, there were variations in progress across the out-of-home sector. For example, pizzas, children’s meals and sandwiches performed well, with at least 75% of products below the maximum target. However, other categories such as pasta meals and burgers in a bun showed less progress.

1.2 What does this mean?

With over 80 food categories covered by the salt reduction programme, mixed progress is to be expected. However, with the foods included in the salt reduction programme providing around 54% of the salt we consume, there can be no excuses for inaction. We have seen successes within some food categories demonstrating that positive action can be achieved with the right leadership.

Salt targets

2. Salt reduction programme – the story so far

In 2003, the Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN) published its Salt and Health report which recommended that salt intake be reduced to no more than 6 grams per day for adults. At the time, the nation’s salt intake was almost 9 grams per day.

Following this, in 2006 the Food Standards Agency (FSA) set salt reduction targets for retailers and manufacturers to be met by 2010. A revised set of targets for achievement by 2012 was published in 2009.

In 2010, responsibility for nutrition transferred from the FSA to the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), then called the Department of Health.

In March 2011, DHSC set new targets under the Public Health Responsibility Deal – this saw companies sign up to pledges to reduce salt in everyday products.

In 2014, DHSC set manufacturers, retailers and the out of home sector (such as pubs, restaurants, cafes, quick service restaurants, takeaway and meal delivery businesses) new targets for salt reduction to be achieved by December 2017 – this included targets across 76 food sub-categories for all sectors, and targets set specifically for the out of home sector across 24 food sub-categories.

A further commitment to salt reduction was included in chapter one of the Childhood Obesity Plan, published in 2016. It stated that businesses should continue to work towards achieving the 2017 salt targets.

In March 2017, as part of its formal responsibility for salt reduction, PHE republished the 2017 salt targets. PHE committed to transparently monitoring and reporting on industry’s progress, as part of the wider reformulation programme, including sugar reduction and calorie reduction.

To date, 4 sets of targets have been published (2006, 2009, 2011 and 2014), covering up to 80 individual product types. The salt reduction programme has contributed to an 11% reduction in salt intakes in the UK (between 2006 and 2014).

3. Next steps

In November 2018, Secretary of State Matt Hancock launched his Prevention Vision, which included plans for “realistic but ambitious goals to bring salt levels down further”.

This intention will be set out in detail by Easter 2019.