JCVI interim statement on phase 2 of the COVID-19 vaccination programme: 26 February 2021

Updated 13 April 2021

Introduction

The Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI) is an independent expert advisory committee which advises the UK health departments on vaccination. In December 2020, JCVI advised the vaccination of nine key priority groups against COVID-19,[footnote 1] covering all adults aged 50 years and over, and younger adults with underlying health conditions that put them at specific risk from COVID-19. This part of the programme, termed phase 1, began rollout in the UK from 8 December 2020. Phase 1 aims to reduce mortality from COVID-19, along with the protection of UK health and social care systems.

The programme has been a great success in terms of delivery, with over 18 million people vaccinated so far.[footnote 2] Given the time taken for people to develop an immune response following vaccination, and the time between infection and disease, we are only just starting to see the impact of the programme on disease rates.[footnote 3] These early data are encouraging, and as time goes on, we hope to see more of an impact as more people are vaccinated and start to be protected from COVID-19.

The successful delivery of the phase 1 programme can be attributed to the exceptional efforts of the NHS, volunteers and community organisations and the operational simplicity of the programme. Programmes that are less complicated to organise are more able to be delivered at speed and are more likely to achieve high vaccine coverage.

Safety data from delivery of the programme so far in the UK indicate that the available vaccines are safe, although mild to moderate short-lived side effects such as a sore arm, headache or mild fever are relatively common.[footnote 4] After considering safety data, JCVI advises that it remains acceptably safe to consider extending the programme to the remainder of the adult population aged less than 50 years old.

Data on hospitalisations due to COVID-19 indicate a number of admissions occur in people under the age of 50 years who would not be vaccinated in the first phase of the vaccination programme.[footnote 5], [footnote 6], [footnote 7], [footnote 8], [footnote 9] JCVI has been asked by the Department for Health and Social Care (DHSC) to formulate advice on the optimal strategy to further reduce mortality, morbidity and hospitalisations from COVID-19 disease in the next phase of the programme.

Options considered for the next phase (phase 2) of the programme include:

- direct protection of those at higher risk of serious disease and hospitalisation, including groups associated with an increased risk

- targeted vaccination to reduce transmission of COVID-19 in the population, or

- vaccination of occupational groups at higher risk of exposure

These groups are not mutually exclusive.

Advice

Mathematical modelling of vaccination strategies for phase 2 indicate that rapid vaccine deployment is the most important means to maximise public health benefits against severe outcomes from COVID-19. [footnote 10], [footnote 11] A strategy aimed primarily at reducing transmission of infection would take longer to achieve reductions in hospitalisations and would require very high vaccine uptake in the target populations. Data are only now emerging on any potential impact of vaccination on transmission, and those who are vaccinated will still need to follow government advice on social distancing. There is evidence that some occupations have an increased risk of morbidity due to COVID-19 and that males aged 40 to 49 years are more likely to be employed in these occupations. [footnote 12], [footnote 13] A mass vaccination strategy centred specifically on occupational groups would be more complex to deliver and may require new vaccine deployment structures which would slow down vaccine delivery to the population as a whole, leaving some individuals unvaccinated for longer. Operationally, simple and easy-to-deliver programmes are critical for rapid deployment and high vaccine uptake.

There is good evidence that the risks of hospitalisation and critical care admission from COVID-19 increase with age, and that in occupations where the risk of exposure to SARS-CoV2 is potentially higher, persons of older age are also those at highest risk of severe outcomes from COVID-19. JCVI therefore advises that the offer of vaccination during phase 2 is age-based starting with the oldest adults first and proceeding in the following order:

- all those aged 40 to 49 years

- all those aged 30 to 39 years

- all those aged 18 to 29 years

An age-based delivery model will facilitate rapid vaccine deployment.

In addition, data indicate that in individuals aged 18 to 49 years there is an increased risk of hospitalisation in males, those who are in certain black, Asian or ethnic minority (BAME) communities, those with a BMI of 30 or more (obese/morbidly obese), and those experiencing socio-economic deprivation.[footnote 5], [footnote 6], [footnote 7], [footnote 8], [footnote 9], [footnote 14] JCVI strongly advises that individuals in these groups promptly take up the offer of vaccination when they are offered, and that deployment teams should utilise the experience and understanding of local health systems and demographics, combined with clear communications and outreach activity to promote vaccination in these groups.

Unvaccinated individuals who are at increased risk of severe outcomes from COVID-19 on account of their occupation, male sex, obesity or ethnic background are likely to be vaccinated most rapidly by an operationally simple vaccine strategy. JCVI will continue close monitoring of the programme in terms of vaccine safety, effectiveness, and uptake, and will update its advice as required.

This interim advice refers to the COVID-19 vaccines currently used in the UK and will be reviewed following considerations on the supply and availability of COVID-19 vaccines for the second phase of the programme.

Background and considerations

Hospitalisations

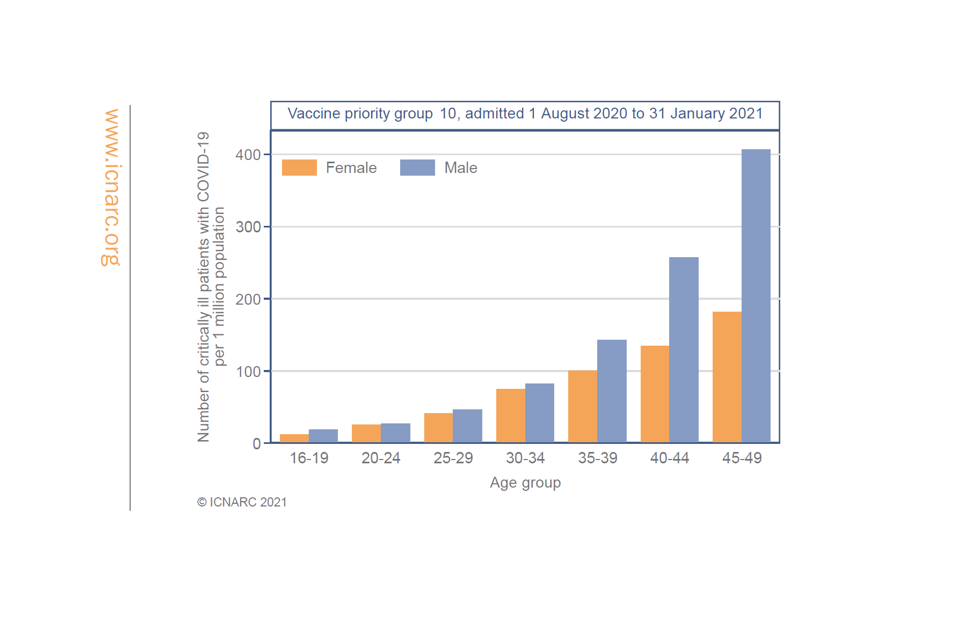

Evidence from ICNARC, ISARIC/CO-CIN, SARi-watch, and OpenSAFELY [footnote 5], [footnote 6], [footnote 7], [footnote 8], [footnote 9] all indicate that the risk of hospitalisation and critical care admission increases with age. Those at highest risk of hospitalisation outside of cohorts 1 to 9 (phase 1) are those aged 40 to 49 years, with the risk reducing with descending age. An example of this evidence is provided in figure 1.

The evidence also indicates that males, certain black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) groups, people in lower socio-economic groups, and those with a BMI of 30 or over, are at higher risk of hospitalisation (see below).

Figure 1: profile of critical care admissions with COVID-19, 1 August 2020 to 31 January 2021

Figure 1 source[footnote 15]

The chart shows the profile of critical care admissions with COVID-19: 1 August 2020 to 31 January 2021. The number of critically ill patients with COVID-19 per 1 million population is highest in those age 40 to 49 years, and declines with reducing age. Rates are higher in males than females.

Male sex

Evidence on hospitalisations indicates an increased risk of hospitalisation in males, particularly those aged 40 to 49 years (figure 1). This risk may be associated with male sex itself, exposure to infection, occupation, and/or other factors.

JCVI strongly advises that males promptly take up the offer of vaccination.

Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) groups

People in certain black, Asian and minority ethnic groups are at higher risk of hospitalisation from COVID-19.[footnote 5], [footnote 6], [footnote 7], [footnote 8], [footnote 9], [footnote 14] This follows a similar pattern to data on mortality reviewed in considerations relating to phase 1 of the programme. There is no strong evidence that ethnicity by itself (or genetic characteristics) is the sole explanation for observed differences in rates of severe illness and deaths. Between waves 1 and 2 of the pandemic changes in the risk of infection and mortality to BAME groups, and within BAME groups, have been observed.[footnote 16] Such large rapid changes are unlikely to be due to biological factors and are far more likely to be related to environmental and behavioural changes.

Discussions with BAME communities and opinion leaders highlight the importance of building trust and the avoidance of stigmatisation or discrimination when planning the delivery of vaccination programmes.[footnote 17], [footnote 18] Thus far, in phase 1 of the vaccination programme, slower uptake has been noted in persons from BAME backgrounds.[footnote 19] Well-recognised factors that impact on vaccine uptake are:

a) access to vaccination

b) vaccine confidence (safety and efficacy), and

c) perception of risk from disease

The reasons for slower uptake in BAME communities are unclear at present, but there is evidence that addressing structural issues related to access and involving community influencers can have a positive impact.

JCVI strongly advises that priority is given to the deployment of vaccination in the most appropriate manner to promote vaccine uptake in BAME communities.

This may include planning to enable easy access to vaccination sites, supported engagement with local BAME community and opinion leaders, and tailored communication with local and national coverage. As appropriate, these efforts should consider a longer-term view beyond the current COVID-19 mass vaccination programme and seek to address inequalities which already exist across the wider immunisation programme.

JCVI strongly advises persons from BAME communities to promptly take up the offer of vaccination.

Underlying health conditions

Evidence indicates that individuals aged 18 to 49 years who have a BMI over 30 (obese/morbidly obese) [footnote 5], [footnote 6], [footnote 7], [footnote 8], [footnote 9] are at higher risk of hospitalisation compared with age matched peers. Only very modest increased risks for hospitalisation were identified in persons with certain underlying health conditions not already covered in phase 1 of the programme. Further analyses are ongoing to better estimate the size of these risks and how these might influence the advice regarding phase 2 vaccination.

Children

JCVI has started to consider evidence on the risk of serious disease in children, the role children may play in transmission, and the safety and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines in children. Following infection, almost all children will have asymptomatic infection or mild disease. There are limited data on vaccination in adolescents, with no data on vaccination in younger children at this time. As evidence becomes available it will be reviewed and advice offered as appropriate.

Women who are pregnant

Both nationally and internationally, no concerning safety signals have been identified so far in relation to the vaccination of women who are pregnant. JCVI is continuing to review data on the risks and benefits of vaccination for women without significant underlying health conditions who are pregnant. As evidence becomes available it will be reviewed and advice offered as appropriate.

Transmission

Targeting groups more likely to interact with multiple other individuals with a vaccine which reduces the risk of infection, onwards transmission, or both, could have some impact on the spread of COVID-19 in the UK. There is emerging evidence that vaccination may prevent asymptomatic infection, which may be inferred as evidence of an impact on transmission.[footnote 20] However, while these data are very encouraging, they are still limited and currently there is no strong real-world evidence of an impact of vaccination on transmission.

Furthermore, which groups contribute to viral transmission is currently not well defined. Data on mixing patterns generally indicate that people mainly mix with others of the same age group, with a higher frequency of contact than with those who are younger.[footnote 21] In addition, members of certain occupations are required to interact with the general public to a lesser or greater degree, or have frequent close contact with co-workers. However, at present there is limited evidence to indicate that any particular age groups or occupations are associated with higher levels of transmission of SARS-CoV2 infection.

Mathematical modelling of strategies for phase 2 vaccination indicates that a transmission-based approach affords modest benefit at best. Speed of vaccine deployment is the single most important factor for an optimal programme that maximises public health benefit. As evidenced in phase 1, a simple age-based programme is considered the keystone of rapid vaccine deployment. Maintaining this structure through phase 2 of the programme will enable the continued high pace of vaccine deployment.

Occupational exposure

While many have been able to work at home during the pandemic, some occupations are not compatible with home working and cannot be undertaken without interaction with other people. In these circumstances individuals may be exposed to SARS-CoV-2. These include workers who have public facing roles, or who work in close contact with co-workers. Commuting to a workplace using public transport constitutes a potential additional risk of infection.

JCVI has reviewed data to understand the association between occupation and the risk of exposure to SARS-CoV2, the risk of COVID-19 disease and the risk of COVID-19 related severe outcomes, including mortality.

The evidence indicates that certain occupations have a higher risk of exposure, and these are more likely to be occupations involving frequent contact with multiple other people in enclosed settings. These encompass the elementary occupations, manufacturing, processing and those working in the caring, leisure and a broad range of service occupations. Where increased risk of serious disease is evident, this is considered likely to be associated with a combination of various risk factors for exposure and poorer outcomes including: older age, an overrepresentation of certain underlying health conditions in those undertaking certain jobs, socio-economic deprivation, household size and inability to work from home. Occupational risk associated with poorer outcomes from COVID-19 has predominantly affected men aged 40 to 49 years (please see annex A for more details).

Delivery of a programme targeting occupational groups is recognised to be operationally complex given a number of key factors:

- robust data on the infection exposure risk for every occupational group, or in every occupational setting, are not available

- occupation is not routinely recorded within primary care records and these records may not be up-to-date

- advice to target certain occupations could be considered discriminatory towards those in occupations where no data are available or that are not accurately listed within primary care records

- workplaces that may be associated with higher exposures to infection may include individuals from multiple occupational groups

Overall, JCVI considers that an operationally simple, age-based programme starting with those aged 40 to 49 years is the optimal way to protect individuals, working in jobs with a potentially higher risk of exposure to SARS-CoV2, from severe disease related to COVID-19.

References

-

Priority groups for coronavirus (COVID-19) vaccination: advice from the JCVI, 30 December 2020. ↩

-

PHE monitoring of the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccination, COVID-19 vaccines and medicines: updates for February 2021. ↩

-

COVID-19 vaccines and medicines: updates for February 2021. ↩

-

ICNARC data on hospitalisations in those aged under 50 years – unpublished. ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5

-

Features of 20,133 UK patients in hospital with covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: prospective observational cohort study, The BMJ. ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5

-

ISARIC data on hospitalisation in those aged under 50 years (unpublished). ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5

-

SARi-watch – National flu and COVID-19 surveillance reports. ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5

-

OpenSAFELY analysis on the risk of hospitalisation in those aged under 50 – unpublished. ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5

-

Vaccination and Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions: When can the UK relax about COVID-19?, medRxiv ↩

-

University of Warwick modelling on options for phase 2 of the COVID-19 programme – unpublished. ↩

-

SAGE-EMG-Transmission Working Group paper - COVID-19 Risk by Occupation and Workplace. ↩

-

Disparities in the risk and outcomes of COVID-19 (publishing.service.gov.uk). ↩ ↩2

-

Harrison D, Rowan K – ICNARC data – unpublished. ↩

-

Bhaskaran K - OpenSAFELY - Ethnicity and COVID-19 death in the early part of the COVID-19 second wave in England: an analysis of OpenSAFELY data from 1 September to 9 November 2020 (unpublished). ↩

-

Annex A: COVID-19 vaccine and health inequalities: considerations for prioritisation and implementation. ↩

-

SPI-B consideration of priorities for phase 2 of the programme. ↩

-

Voysey et al. Single dose administration, and the influence of the timing of the booster dose on immunogenicity and efficacy of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (AZD1222) vaccine. ↩

-

Mossong et al. Social Contacts and Mixing Patterns Relevant to the Spread of Infectious Diseases. ↩