Policing Productivity Review (accessible)

Updated 23 April 2024

Foreword

Policing matters. It matters because the police is the service we all need to know we can rely on, particularly when the worst happens. To keep us safe, and to maintain the rule of law. Officers and staff work hard, day and night, dealing with emergency calls, bringing offenders to justice, and keeping us safe in our communities and our homes.

And yet while there has been considerable investment in policing, there is also significant focus on how policing can improve the outcomes it delivers for the public. This spans across the country, across crime types, and across the millions of interactions the police have with the public every day. We saw great work when we visited each and every police force in the UK during this review. We also saw areas in which productivity gains can improve outcomes for the public.

This review was commissioned in summer 2022, against a backdrop of tens of thousands of new officers, significant challenges to trust and confidence in policing, and greater expectations of our police service.

Productivity matters because it means we are getting the best possible policing service we can from the resources we have available. Good policing is the cornerstone of a safe and thriving society.

In the course of the review, we have helped identify and deliver tangible improvements to the frontline: the changes already agreed in terms of how policing responds to mental health calls and how crime is recorded are freeing up over one million hours.

In this report we make recommendations which would free up more police time: police hours which could be used to attend more burglaries, more cases of domestic abuse, more incidents of antisocial behaviour.

We also recommend improvements in how police forces make best use of good practice and of science and technology, now and in the future. We found that forces have more in common than is sometimes argued and that targeted financial incentives to forces will help unlock productivity improvements.

Working with a small number of forces, we have developed a model process tool which will enable police forces to deliver improved outcomes for the public. We recommend rolling this out to all forces in England and Wales in the next 18 months. The insight this tool delivers will improve the service police forces offer, as well as strengthening future service models. Officers and staff must have the confidence to do the right thing and to do it well.

Finally, improving productivity needs to be more ingrained in policing culture. We make several recommendations, including a big push on data and evaluation and a bespoke policing productivity function to drive improvement. It will be important to build on the momentum created by early productivity gains.

When taken together, all the recommendations in this review have the potential to free-up about 38 million hours of police time over the coming 5 years – this will of course require considerable effort from policing and from its partners. This is the equivalent of another police officer uplift.

Thank you to all who have engaged with the review – partners in forces across the country, the HM Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services (HMICFRS) and the College of Policing, the National Police Chiefs Council, the Association of Police and Crime Commissioners, the Home Office, and, of course, my team. The engagement and energy have been vital to the progress we have made so far; we need this positive drive to continue.

At a crucial juncture for policing, seizing productivity gains will improve outcomes for the public and improve trust and confidence in policing. Nothing can be more important.

Alan Pughsley QPM

Productivity in policing

Why policing productivity matters

Policing must demonstrate the public benefits of the substantial investments it has received

This Review was established to ‘identify ways in which forces across England and Wales can be more productive, improving outcomes’[footnote 1]. In the three financial years to March 2023, Government funded the recruitment of an additional 20,000 police officers. This – together with additional resources provided by precept - is a considerable investment into policing. As new recruits build up experience and capabilities, we would expect to see its impact in terms of public safety.

Compared to 2007, officer numbers have increased seven per cent whilst the population has increased by about 12 per cent (and with it, demand). However, like-for-like comparisons are not necessarily helpful: technology for example should have made police forces more productive since then. But to a large extent we have found that if the uplift has helped fill the most urgent capacity gaps (and improve performance), it has not taken away the need to prioritise and task resources effectively. A productivity drive is as necessary now as it was in the years of officer reduction.

An environment of budget pressures suggests difficult choices ahead for public sector investment. Public agencies will need to evidence, more than ever, that they are providing value for money and becoming more productive.

Pouring additional resources into a service might create more outputs but it does not per se increase productivity if these resources are not used wisely. Neither do officer numbers guarantee reduced crime[footnote 2]. Effective resource allocation is essential to deliver the greatest gains. Coordinated planning and multi-agency collaboration are vital to maximise the chances of better public outcomes. In this context, as a pre- requisite to further investment demands and to strengthening public legitimacy, it is imperative that the policing sector is able to demonstrate how it is making best use of its resources and what direct benefits its activity delivers to the public.

The operating landscape of policing is shifting

Policing demand has changed. Since the mid-1990s, there have been long-term falls in overall crime levels but since 2014, offences have risen again (while still 20 per cent below their 2002/03 level). New technologies have created new criminal opportunities: the Office for National Statistics (ONS) reports 3.8 million fraud offences[footnote 3] and cyber-enabled, or cyber-dependent crimes, and even across “traditional” crimes, the Metropolitan Police Service assesses that two fifths of robberies and 70 per cent of theft are for mobile phones.

Technological advances can also give rise to investigative opportunities, and policing productivity (and its perceived effectiveness in using technology) can act as a deterrent to criminality.

Some patterns of crime are less easy to read. Violent offences recorded by police increased, but the Crime Survey for England and Wales suggests a decrease. Recorded sexual offences have markedly increased. More victims are finding the courage to come forward and report crimes such as rape, domestic abuse and the sexual exploitation of children. The recognition of vulnerability in victimisation has become a powerful element shaping policing since the death of Fiona Pilkington and her daughter in 2007.

Because of these changes, policing today requires a very different skillset. In 2003, armed with a knowledge of three crime types (burglary, theft and criminal damage), a constable knew how to approach 80 per cent of the demand coming their way. In 2023, in order to manage the same proportion of their work, this constable has to be competent across six disparate and wider categories of crime: theft, fraud (including online), violence with injury, stalking and harassment, public order and violence without injury. Non crime demand on officers equally broadened in scope during that time.

The policing mission is broad, and in some respects, forces have experienced “mission creep” in the last decade as the reach of a number of other public services has reduced, in a context of tighter resources and rising demand. In this, our findings echo the Chief Inspector of Constabulary’s recent State of Policing report[footnote 5]. Today the police role encompasses three interconnected spheres:

-

work that only the police can do because it requires the exercise of their unique powers. This includes maintaining the peace on the streets.

-

work undertaken by the police to meet their obligations within the criminal justice service (i.e., seeking justice outcomes).

-

work in multi-agency partnerships that seek to solve societal, community-based problems (crime and non-crime demand) or address specific offender management issues.

The last category is where it is easiest for the police to step-in to fill a service provision gap left by partners. This is not a new issue: a Home Office (1995) Review of Police Core and Ancillary Tasks, attempted to identify superfluous core and ancillary tasks that could be shed or moved to other agencies . Many changes subsequently took place – but other areas of mission creep have since arisen (as detailed for example in the mental ill-health section).[footnote 6]

Against this shifting landscape, the productivity question moves from a general one (are police productive?) to more specific lines of enquiries: are police productive in their response to areas of rising demand, such as domestic abuse or fraud? How are they developing the right capabilities to match their operating needs? Are policing resources being used productively in the criminal justice, social or emergency arena?

Figure 1: breakdown of crime types. Source: ONS [footnote 4]

| Crime type | 2002/03 | 2022/23 |

|---|---|---|

| Theft | 50% | 25% |

| Criminal damage | 16% | 8% |

| Burglary | 13% | 13% |

| Violence with injury | 5% | 12% |

| Violence without injury | 4% | 8% |

| Fraud | 3% | 17% |

| Public order | 2% | 9% |

| Drugs | 2% | 2% |

| Robbery | 2% | 2% |

| Weapons possession | 1% | 1% |

| Sexual | 1% | 3% |

| Stalking and harrassment | 0% | 10% |

Public consent and trust are drivers of productivity - and a productive police service feeds trust and confidence

Societal and public expectations are evolving. More people expect choice, accessibility and convenience in the service delivery they receive from public sector organisations. But even as technologies evolve and the policing environment changes, some core public expectations remain constant: police visibility, neighbourhood presence, criminal justice effectiveness, and the ability to trust.

Levels of trust and confidence in the police in England and Wales have dropped in recent years. One driver of this decline is the gravity and number of criminal acts perpetrated by serving officers, and more widely the issues with culture and behaviour highlighted by a number of reviews, most notably Baroness Casey’s Review into the standards of behaviour and internal culture of the Metropolitan Police Service[footnote 7]. HMICFRS’ Chief Inspector of Constabulary talks about “a limited window of opportunity to repair public trust”.

In this context, one could query whether productivity should be a priority at all. However, productivity and trust are closely interlinked. Three elements can, to various degrees, drive the public’s perceptions of their police:

-

Values (including fairness and perceptions of fairness, and issues of police integrity).

-

Reliability (for example through the police interactions with the public, clarity of expectations and follow-up with victims).

-

Capability (through perceptions of police effectiveness and competence)

Forces delivered substantial efficiencies through the 2010s as funding, and officer numbers, decreased. However, improving productivity is different from identifying savings: reducing inputs to reduce costs can lead to a poorer service, declining outputs and lower productivity.

For example, neighbourhood policing was the area which suffered most from the decline in officer numbers. Yet, neighbourhood policing cultivates community consent, fostering trust and legitimacy in policing; it provides officers with contextual understanding for the judicious use of their powers; perceptions of a local police commitment to civic engagement are strongly associated with higher confidence in the police; in reverse, perceptions of antisocial behaviour and disorder (where neighbourhood police have a key role) are correlated with low confidence in the police[footnote 8].

Low legitimacy and low levels of trust, in return, impact police effectiveness. For example, it creates situations where officers ‘have to be persuasive just to get basic information such as statements and other evidence’[footnote 9]. It decreases the attractiveness of forces to get the best candidates on the job market. A lack of legitimacy also means officers on the street have to work harder and longer to get results, becoming less productive.

The Casey Review highlighted that “policing should start with engagement, rather than simply end with the passive public endorsement of plans or initiatives”. This is also key to driving up productivity in the sector. Reconnecting with the public will provide better knowledge of what users expect, need or what they do not care for (which could inform prioritisation of what the service should deliver[footnote 10]). It provides a platform to educate the public on the policing choices that must be made within existing resources. Many forces – supported by their Police and Crime Commissioners - are currently working to strengthen their dialogue with communities (Greater Manchester Police, Metropolitan Police Service, Lincolnshire Police and others) – if this feeds into the decision-making processes, it will help them maximise public value by improving outcomes for citizens. It can re-ignite a virtuous circle between productivity and trust[footnote 11].

Figure 2: links between trust in policing and productivity

Higher levels of trust and satisfaction:

- Operations: more public participating in prevention; eyewitness accounts and victim statements are a critical factor determining the likelihood of solving a crime; more volunteers helping solve local problems.

- Officers: improved interactions with the public; increased compliance.

- HR: more applicants, increased diversity of applicants, wider pool to choose from.

- Finance: better targeting of resources, improved understanding of impact, clear focus on what makes a difference to people.

- Strategy: clearer articulation of decisions and expected public impact; improved transparency, performance, accountability and culture; stronger funding case

Leads to a more productive police sector:

- More productivity frees up officer time hence more cases dealt with, more neighbourhood presence, better timeliness in attending scenes.

- The police service offer is able to better match public expectations.

- Better outcomes for victims.

- Increased perception of reliability.

- Reduction in fear of crime and increase in feeling of safety.

- A force more effective at dealing with crime and more likely to be seen as fair.

Leading to higher levels of trust and satisfaction.

What we mean by policing productivity

Productivity in a public sector context

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), an authoritative international source on methodology for productivity analysis defines productivity as ‘a ratio between the output volume and the volume of inputs. In other words, it measures how efficiently inputs, such as labour and capital are being used … to produce a given level of output’[footnote 12].

In a public sector context, the concept is more complex because outputs (what is directly provided by the public organisation) are ‘non-market’ outputs, most often provided free of charge. The value of these services to the public (outside a market’s pricing mechanism) is divorced from the cost of their provision and their quality standard.

Public sector productivity can perhaps be better understood as the combination of efficiency and effectiveness: how good a public organisation (or sector) is at delivering the public outcomes it was set up to deliver, making the best use of its available resources. A focus is on improving productivity then means:

-

Delivering the same quantity and quality of service outputs, but at a reduced cost, or

-

Improving the delivery of service outputs (in quality or quantity) for the same cost[footnote 13]

The challenges to measuring productivity in policing

As is often the case in policing, the Peelian principles[footnote 14] are an initial reference point. Robert Peel’s statement that the “test of police efficiency is the absence of crime and disorder” provides an idea of the public outcome sought, but little practical help in terms of productivity measurement (in common with much of the prevention area, where assessing what might have happened if no activity had been undertaken is a fiendish exercise).

The absence of crime and disorder objective arguably sets a laudable but unrealistic framework given that the drivers of crime are mostly outside police controls (a parallel in the health sector might be to set the absence of illnesses as a measure for the NHS). Areas like prevention also require a whole-system approach complementing policing activity.

In practical terms, one can point to areas of policing success. Burglary is at an historic low and many serious crime types remain below pre-pandemic levels; the sector has again and again, shown its effectiveness in dealing with a wide array of major events (from the pandemic to public disorder and terrorism threats), supporting the UK’s attractiveness as a place to live, work and invest. Many forces have been successful in reducing their running costs and delivering substantial efficiency savings in the past ten years.

Yet in other areas police effectiveness and efficiency is either not where it should be, or evidencing it suffers from a lack of data and evaluation[footnote 15].

Two specific challenges to making an assessment of policing productivity relate to the “multi-output” and “multi-outcome” nature of police activity, and to the shifting priorities they are subject to in strategic and operational terms[footnote 16].

Proxies to measure policing productivity have been used, whether in academic studies, government policy or in the media. Often based on an output method, measures typically include those with a more direct links to police activity[footnote 17]: number of arrests, rate of crimes solved, average response time to calls for service. Each approach has limitations and only provides a partial picture.

With a wide-ranging set of responsibilities and a society that expects so many things from its police service, set measures of policing productivity risk favouring certain policing activities over others that are less measurable, but just as essential[footnote 18]. External factors also impact police performance, whether it is officers responding to non-crime demand (unwarranted police involvement), “picking up the slack” to make up for pressures on other public services (such as in the mental health area), or whether backlogs further down in the criminal justice process are slowing down new cases leading to higher “victim attrition”. Policing productivity needs to be looked at in the context of the effectiveness of its partners, and of its partnerships.

Finally, there needs to be a recognition of the different ways in which an output can be delivered – for example in terms of the quality of the service experienced by the public. A factory churning out a high number of faulty products would not be productive – and so it would be for police investigations or case files.

For those reasons, it has been important to the Review team to use a combination of approaches to provide a fuller picture of policing’s effectiveness and efficiency. For the policing sector, the challenge is two-fold:

- How does it know it is productive with its current and new resources, and is it able to articulate clearly, through data, the public benefits that stem directly from its activities?

- How, on an ongoing basis and in the long term, can it improve its productivity further, for example to deliver the 0.5 per cent annual productivity growth sought by the Chancellor[footnote 19]

The police mission

Whilst policing inputs (such as police officer numbers) are easy to count, measuring productivity requires consensus as to what the desired outputs from policing are, in practice that means a common understanding on what the police are here to do.

The National Police Chiefs Council (NPCC) sets out six “policing missions” in its 2030 Vision[footnote 20] which chief constables agree resources and activities should be deployed to: “To keep our communities safe; To prevent crime and criminality; To effectively respond to all types of demand; To develop and inspire our workforce and transform our culture; To strengthen and advance our partnerships to prevent crime and deliver justice for victims; And to embed a culture of continuous improvement and innovation in policing”. Productivity would then refer to the efficiency and effectiveness with which police forces carry out these duties and responsibilities. However, the breadth of these missions only further highlights the challenge of setting a clear productivity measure – as well as the need for policing to be more precise on its objectives to enable success and productivity to be effectively measured.

In practice the police are under a duty to provide free, comprehensive, universal services, often in pressing situations. To a large extent, it responds to a “live” urgent demand beyond its direct control. In that context, the service’s task is to respond to community needs effectively, to maximise outcomes for the public and for victims. To do this, forces grade calls from the public as to priority, recording and allocating crimes with viable lines of enquiry for investigation.

With constrained resources, what policing should prioritise is always a thorny question. Police and Crime Commissioners and government, with their democratic accountability, provide some strategic objectives and priorities.

Consideration of harm, threat and risk is a complementary approach. In crime statistics offences are all equivalent numbers, but homicide is far more harmful than shoplifting – and naturally more resources should be allocated to prevent and investigate the more harmful crimes. Harm measurements (such as the Cambridge Crime Harm Index or the ONS Crime Severity Score) can be a tool for prioritisation – and to an extent a proxy to show the recent increases in the “complexity” of crime[footnote 21], against a decrease in actual volume.

Policing productivity is perhaps better assessed by how (and whether) the duties and responsibilities of the police are shaped into clear aims and objectives; what inputs (resources) go into meeting these objectives; what outputs are created from these resources (including the quality standard) and what tangible benefits (outcomes) arise for the public. The Review therefore focussed on what could make a difference to the public, rather than settling for an index of productivity for policing. This has guided our multistrand approach.

Improving policing productivity

Looking back

Notable historic reviews touching upon policing productivity (and the closely related themes of efficiency and effectiveness) have included the Operational Policing Review (1990)[footnote 22], Making a Difference: Reducing Bureaucracy and Red Tape in the Criminal Justice System (2003)[footnote 23], and the Independent Review of Policing by Sir Ronnie Flanagan (2008)[footnote 24].

Issues have lingered. For example, many of the findings of the extensive 1990 Operational Policing Review feel contemporary:

- It noted pressures on police demand: “a very significant proportion of all manpower and financial increases achieved… have been absorbed by new procedures, new legislation…”. “Changes in mental health provision have resulted in (higher demand for policing)… These calls are frequently extremely demanding in terms of police time”.

- Issues of mission clarity and data consistency. There is a “desperate need for the service to be clear as to the critical indicators or success and to standardise measurement of common activities across all forces”. It recommended that “data methodology should be standardised nationally to allow reliable comparisons”.

- The drive for short-term efficiencies has come at the cost of effectiveness (less measurable work such as prevention, reassurance/patrols and “customer service” side of things) creating negative longer- term effects in the quality of service and public satisfaction.

- Barriers to long-term innovation: “The proportion (of funding) that is committed to capital projects and other major equipment programmes is far too low when compared to other sectors of public service and industry. It is virtually impossible for chief police officers to plan ahead and to make provision for long- term projects”.

- Sector inconsistency across technology. “The lack of a national information technology strategy has led in many cases to piecemeal and sporadic development … which have led to an incompatibility between many systems and methods. The overall effect of this lack of coordination and strategic development has been the failure to grasp many of the opportunities that have been presented by the growth in information handling and use”. The 1990 police-led review suggested that central mandation should be introduced: “Following evaluation of IT systems, standard minimum specifications should be set”. “Mandatory IT standards should be introduced throughout all police forces”, and “police IT research and development should be centrally directed to ensure interoperability where appropriate and quality control”. At the same time, they were hopeful about “the technological forecasts … that police, magistrates courts, crown courts, prisons and probation services (will soon) work on linked systems”.

- The review also noted that training commitments had increased, increasing abstraction, and that training effectiveness could be difficult to assess against real-life demands.

These findings still echo in the pages of this report through our own findings and analysis. The imperative to change the narrative dictates two actions:

-

Firstly, the practical, hands-on approach that we have taken in this Review. We have aimed to use our findings to create momentum and work with the Home Office and forces to enact change there and then. By building a Model Process tool with six forces, the Review has aimed to show – not just tell – what can be achieved. With support from the Policing Minister, the Review has already freed up police officer time by unblocking barriers to productivity across mental ill-health demand and in crime reporting.

-

Secondly, politicians and sector leaders need to use this Review’s recommendations more effectively than their predecessors did of previous reviews in the 1990s. In the current context of economics, public trust and the technological pace of change, inaction, muddling through or making incremental tweaks carries far more risk to police legitimacy and productivity than can be afforded. The focus on action must continue beyond this report.

Our practical approach

Change in policing frequently stems from failure – and the subsequent inquiries, inspections or commissions. This Review wants change in policing to be also inspired by success: what works, what benefits the public, and makes a positive difference.

The Review has looked at organisational and individual productivity: assessing where the sector makes best use of its assets, and whether individuals are used as effectively as can be in terms of their capabilities. We have concerned ourselves with identifying practical, implementable ways in which policing can be more efficient and effective, improving public benefits – in both quantity and quality. We have identified operational and structural barriers. We have also sought to robustly evaluate the productivity impact of innovations and approaches that some forces have adopted, and where wider adoption would benefit all forces.

We have sought to take the policing sector and its leaders with us, building consensus on the issues and challenges, bringing in their participation across all strands of study, and in implementing the identified improvements.

The Review, with the support of the policing minister, has created momentum in identifying areas of activity that may not be a productive use of police officer time – helping free up additional capacity. The section on barriers in policing reviews three example areas: mental ill-health demand, Home Office crime recording rules, and criminal justice processes.

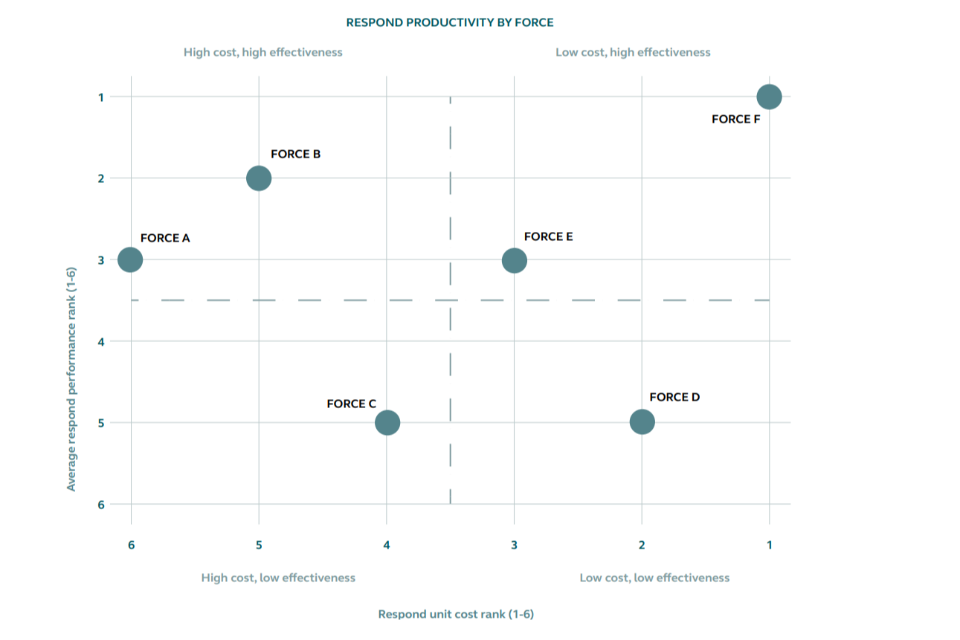

The Review has used various methodologies to assess policing productivity. It has developed a process-based approach (outputs by activity) to assess impact against resourcing for a number of offences and processes (burglary, domestic abuse including coercive and controlling behaviour, violence with injury, adult rape and serious sexual offences, antisocial behaviour, responding to the public). A tool developed with six police forces (Cumbria Constabulary, Durham Constabulary, South Wales Police, Thames Valley Police, West Midlands Police, West Yorkshire Police) and complemented by data from the Home Office’s Police Activity Survey (PAS) provides senior leaders with an insight into the productivity levers they can use to improve processes and deliver better quality outcomes. The tool sets out the steps in each process, the performance in relation to the cost, and potential actions other forces use to improve their own productivity and effectiveness.

We have examined where forces have added capacity or created new specialist capabilities (police officer uplift or precept increases), and what outputs (reports, detection, arrests…) are being delivered by the addition of these resources. This aims to strengthen the articulation between police investment and public outcomes.

Working with the Vice Chair of the NPCC and chief constable of South Wales, and National Policing Chief Scientific Adviser, we have identified how the systemic use of innovation and technology can be improved across 43 forces. Technology is an asset whose exploitation by policing has been necessary but patchy. We looked at the potential for greater national consistency and risk appetite - where technological investment are not simply about replacing legacy systems, but about innovations to improve productivity in areas such as investigations.

Finally, policing needs to develop a culture focused on approaches that demonstrate their effectiveness, driven by delivering best outcomes to the public and value for money. The Health and Education models should be applied to policing to lever better evidence sharing and encourage robust innovation. The Review developed the idea and a proof of concept for a Police Endowment Fund.

Within the twelve months of the Review and with a lean team, we could not tackle all the inefficiencies that have accumulated over, sometimes, decades. The Review team has prioritised the areas where short term impact can be achieved, and put in the foundation blocks to a more effective system in the longer term.

With limited time, the Review has largely focused on areas where some of the biggest potential productivity gains were within grasp. Other opportunities for productivity gains have been identified. Among them, and prioritised for further exploration in the next phase of work are a review of police custody; the police response to, and involvement with, missing person incidents; officers on restricted duties; and the potential of artificial intelligence.

Policing productivity: a duty for forces and partners

Systemic constraints exist in policing which are not conducive to productivity. These include budget constraints, frequent policy interventions and short-term policy focus, external bodies’ guidance and recommendations. If maximising productivity depends on being able to use the most appropriate resource for the job, in many instances, police forces are too financially constrained to do so. Set officer numbers, savings requirements and lack of capital funding and long-term revenue visibility can mean that officers end up in back-office functions or that technology investment is neglected in favour of labour-intensive processes.

Many of the productivity levers that would be available to a CEO are out of reach for chief constables: short and long-term priorities, delivery and training standards, demand resourcing ratio, even dismissals, are often set by other players in the wider policing sector. Internally, regular turnover in senior officers’ areas of responsibilities can lead to a patchy follow-through with critical initiatives already underway whether in terms of sustainability, consistency or upscaling. Yet there is much to be gained if a wider ownership of productivity is taken on at all levels, internally and externally:

- Police forces need to create an innovative culture across their workforce. Bedfordshire Police for example is working with Amazon Web Services (AWS), to promote workforce participation in identifying areas of activity that could be improved. Using AWS’ methodology of “working backwards” (starting by picturing the public service offer), the force is encouraging submissions of proposals ready to be presented to an expert panel.

- Forces need to measure, understand and articulate the links between their activities and the public benefits these deliver. This means clearer objectives, better, comparable data, and stronger evaluations.

- Finally forces, supported at the national level, need to look beyond what is urgent today, and plan against the needs of tomorrow. They need to work together to scope technological opportunities, develop workforce capabilities and prioritise resourcing strategically.

- The Police Reform and Social Responsibility Act 2011 requires Police and Crime Commissioners to “secure an efficient and effective police for their area”, so they have a leading role in promoting productivity – and making it a focus of the oversight.

Every year, hundreds of new recommendations, guidelines and changes in standard or processes are put forward to forces by external partners. For example, in September 2023 on HM Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services (HMICFRS) recommendation portal, each individual police force had on average four current causes of concern, 101 live recommendations, 28 pending areas for improvement (stemming from more than 80 inspections on average). These address failings or areas for improvement – and aim to minimise risk. Taken collectively however, they create considerable resourcing demand to implement and to deliver on a sustainable basis. Yet it is not always clear whether the resourcing demand has been considered to ensure that it is commensurate with the expected public benefits.

From the outset of the Review, and in our visits to forces, Chief Officers raised a number of areas outside their direct control that were preventing their force from being as productive as possible and hindering the deployment of their officers. Whilst it was felt that these might create a substantial drag on resources, there was very little data to confirm their perception and estimate the scale of that impact.

The Review looked into three areas raised by forces recurringly: unwarranted police response to mental ill-health incidents, crime recording rules, and precharge files. The review has demonstrated such external barriers can be addressed if:

-

the demand can be accurately assessed to generate a meaningful national picture,

-

an evidence base is created to build the appropriate support for change, and

-

the policing sector works with partners to implement pragmatic solutions.

The barriers studied in this chapter have external drivers, but whilst partnership working is essential to bring about their fundamental resolution, in each case we have also found clear opportunities for forces to complement this with internal processes or delivery improvements.

Recommendation

Organisations that review or inspect policing – including HMICFRS, the Independent Office for Police Conduct and the College of Policing - should have a duty to assess the investment implications of their guidance or recommendations. The two major considerations should be: (i) whether effectiveness has been demonstrated, and (ii) whether the required resourcing is a commensurate and cost-efficient way of delivering the expected benefits (Recommendation 4).

Barriers to productivity

Mental ill health demand

Police has a legitimate role dealing with individuals who are suffering mental ill-health (for example victims or perpetrators of crime, or those who pose an immediate and serious risk to themselves or others), but officers find themselves intervening in broader situations, where other public services have the expertise and ought to take the lead.

Police activity outside of its core mission leads to three key negative outcomes:

- Individuals such as mental ill health patients do not receive the timely and appropriate professional response they need.

- This demand is not visible to partner agencies, preventing them from making the investments or changes required to deal with that demand (or bid for funding to improve services).

- Police resources become tied up dealing with things they should not be doing (unwarranted effort or demand) having a negative impact on policing productivity and public confidence. The mission creep becomes entrenched – with further recommendations from inspection or accountability bodies.

The review worked with all 43 police forces in England and Wales on a snapshot of 24 hours of mental ill health related demand in October 2022. Several police forces also conducted deep dives on their available data to understand the different forms of demand and a second snapshot with six police forces took place in January 2023. Our findings are captured in our Mental Health Demand on Policing report[footnote 25].

In 2021/22, police forces recorded over 600,000 incidents linked to mental ill health, indicating that policing could be spending 2.2 million hours annually dealing with mental health related incidents[footnote 26].

While some incidents involving mental ill-health do require police attendance, 45 per cent involved no immediate threat of serious injury, nor any crime. In our second report, we demonstrated police could be spending almost 1.6 million hours at incidents of a “non-crime no immediate threat” nature where arguably other public services should take the lead[footnote 27]. For many of these, the deployment of officers, rather than specialist health support, is not a valid use of police resources. The review also identified instances where forces or their Police and Crime Commissioner were paying for elements of provision that should be funded through the NHS long term plan.

Data capture by police forces can underplay the mental ill-health element of police demand. Our first snapshot identified that 5.8 per cent of incidents recorded by police were related to mental ill-health, with large variations across forces. The second snapshot - with six police forces in January 2023 – recorded an average of 8.9 per cent of incidents related to mental illhealth[footnote 28]. Data quality work undertaken before and during the second snapshot helped forces better identify mental ill-health demand and has increased consistency of reporting across the sample.

Key causes of “unwarranted” demand

Section 136 dwell times: Police officers have the power under Section 136 of the Mental Health Act to detain individuals they encounter in public who are experiencing a mental health crisis and need immediate care. Once detained, the individual should be conveyed to a specialist health-based place of safety for assessment by professionals. Police officers are spending unacceptable amounts of time safeguarding these patients, usually in hospital Emergency Departments while they await an assessment. While police involvement at the point of detention might be warranted, the use of police resources to safeguard the patient awaiting an assessment clearly is not. The review identified police officers spend an estimated 800,000 hours annually waiting with mental health patients. This is time they could use more effectively attending 400,000 domestic abuse incidents, 1.3 million antisocial behaviour reports or 500,000 burglary reports.

Detention in custody suites: Individuals who have been arrested and taken to police custody suites may be assessed by mental health professionals. If they decide the individual needs to be detained for further treatment, they will seek to identify a suitable bed. Police forces report that patients are being regularly held, for their own safety, in custody suites without any legal framework until those beds can be found (as many as 3,000 people a year). Police forces take inconsistent approaches to address these situations.

Missing from NHS institutions: Every year, about 25,000 individuals are reported to the police as missing from mental health settings and hospitals. A report on missing episodes from healthcare settings in 2020 reported that in 37 per cent of cases reviewed, it had been “inappropriate” to make a missing report to police and the incident should have been resolved by the relevant agency[footnote 29]. This is worth further analysis (see recommendation x).

Towards a more productive partnership with other agencies

Policing needs to be clearer with the public and partners where it will, and will not, accept responsibility from other agencies. Where another agency already has an established duty of care, police involvement should be limited to:

-

when there is a real and immediate risk of death or serious injury, or

-

crime has occurred or is occurring, and there is a requirement to secure evidence, or

-

there is a requirement for policing powers.

Some police forces had already worked with partners to address the issues above. Two examples were highlighted in our previous report.

The “Multi-agency response for adults missing from health and care settings: A national framework for England[footnote 30]” encourages partners to carry out relevant actions such as telephone enquiries and searches of the immediate area, and to only report patients missing to the police if there is a critical concern for their safety, they are detained under the Mental Health Act, or they have failed to return home and there is concern they will not return or suffer serious harm. West Yorkshire Police is in the process of implementing this framework with partners.

Right care, right person

In 2018/19 Humberside Police received 14,000 calls for service in relation to mental ill health, a rise of 35 per cent in two years. This accounted for six per cent of all its demand. Dealing with these calls severely hampered the force’s ability to respond to other calls for service. This led the force to create a multi-agency partnership ‘task & finish’ group with senior representatives from local authorities, mental health service providers, hospitals, Commissioning Groups and Ambulance Trusts. New processes set out clearly when the police involvement in health and welfare incidents was inappropriate and could be better dealt with by another partner agency.

Key to success was collaboration with partners to help them understand what demand might be re-directed, and help them implement appropriate policies, structures, and resources. Legal advice was also sought. The robust position revealed unresourced demand, which also enabled partners to seek investment into areas that required it.

The proportion of non-crime mental health incidents to which police deployed to fell 16 per cent, an average of more than 500 fewer deployments per month, saving in excess of 1,100 officer hours per month.

Progress on mental health demand on policing report recommendations

In November 2022, the Policing Productivity Review made eight recommendations in its Mental Health Demand on Policing report.

The first recommendation (to implement the Right Care Right Person model) is now being implemented in every Home Office police force. In July 2023, NHS England, the police and government signed up to the National Partnership Agreement: Right Care, Right Person. This sets the parameters for a police response to a mental health-related incident: to investigate a crime that has occurred or is occurring; or to protect people when there is a real and immediate risk of death or serious harm. It also requires local partners in England to work towards taking responsibility for individuals detained by police under Section 136 of the Mental Health Act, within one hour of that person arriving at the appropriate facility[footnote 31]. Partners in Wales are also working through implementation.

Our recommendation to implement the national framework for missing adults will be incorporated into the Right Care, Right Person approach. The framework places responsibility on care providers to prevent missing episodes and take action to locate individuals prior to contacting the police.

Our recommendations on improvements to the quality of police recording and reporting on mental ill health demand have been incorporated in the NPCC Mental Health & Policing Strategy published in December 2022. They are being implemented through the roll out of Right Care Right Person. This will help policing and healthcare services better understand the nature of mental ill health demand.

We also made recommendations for dedicated healthcare staff to attend mental health incidents and provide dedicated telephone support. Health care trusts are expanding the provision of mental health transport vehicles, mental health nurses in ambulance control rooms.

Other recommendations to review Section 136 legislation and address gaps linked to patients being detained in custody are still being considered across relevant NPCC portfolio areas.

Recommendations

The Review made a number of recommendations in November 2022 and February 2023 to improve productivity in how the public sector manages mental ill-health demand. The resulting national partnership agreement – including Right Care Right Person – is a significant achievement which should enable improvements.

To ensure continued progress, the Policing Productivity Review team and the national police lead for mental health should report to ministers twice a year on implementation against the recommendations made in February 2023. The first of these reports should be submitted by 31 December 2023 (Recommendation 5).

Home Office counting rules

The Home Office counting rules were established in 1998 and have been amended several times over recent years in response to concerns that police forces were under-recording crime. HMICFRS has encouraged forces to adopt early crime recording practices often summarised as a move towards “crime to investigate”’ rather than “investigating to crime”. Working with the Chief Constable of Lancashire Constabulary (NPCC lead in this area), the Review has addressed three barriers to productivity raised by police forces:

-

The counting rules have become confusing and bureaucratic, requiring significant resources to manage and check.

- Police officers and staff have found themselves recording or unable to cancel crimes they knew had not happened.

- The volume of duplicate crime records confuses victims and investigators, preventing them from focussing on the principal crimes that needed to be investigated and the highest risks that needed to be prevented.

In early 2023, the NPCC lead consulted with all police forces to identify simplification opportunities that would make a material difference in reducing bureaucracy while maintaining a clear victim focus and ensuring that the service the victim receives would not be diminished. The review supplemented this work with illustrative data from two police forces (Hertfordshire Constabulary and Kent Police).

The Review reported in May 2023 that the Home Office counting rules had led to police forces “double recording” some crimes and inappropriately recording others. This had resulted in significant time and effort being spent by police forces recording crimes unnecessarily. It made four recommendations for changes to the rules which were accepted and implemented in May 2023. The full findings are set out in the Review’s Home Office Counting Rules report[footnote 32]. The key changes were:

- Changes to the crime cancellation rules to redress the current imbalance. Police forces to take a proportionate approach and give authority to Force Crime Registrars to make final decisions on what crimes should be cancelled.

- Removal of double counting of behavioural crimes. Restore a version of the principal crime rule so police forces are recording the most impactive crime such as harassment, stalking offences and controlling/coercive behaviour.

- Changes to the ways malicious communication offences are recorded. Now requires police to consider whether the communication may be an expression which would be considered to be freedom of speech, and allows for recording and investigation in more serious cases where the principal crime rule does not apply.

- De-notification of the offence of Section 5 of the Public Order Act 1986

The implementation of these recommendations (and the double-counting in particular) is expected to lead to the reduction of as much as four per cent (236,000) of crime reports per year, improving the accuracy of crime recording and the service to victims. It will save as many as 433,000 officer hours that can be redeployed from unnecessary recording tasks, to dealing with offences or attending incidents (the equivalent of the initial attendance at 220,000 domestic abuse incidents, 270,000 burglaries, or almost 740,000 antisocial behaviour incidents).

Home Office counting rules phase 2

The Policing Productivity Review team continue to work closely with the NPCC lead to identify further opportunities to reduce bureaucracy. Submissions will be made in autumn 2023 with the expectation that implementation should follow swiftly, prior to the end of 2023/24. Phase 2 will focus on the detailed work of other NPCC portfolio leads namely:

-

Reducing bureaucracy linked to outcome recording.

- Ensuring Op Soteria[footnote 33] is embedded into the new outcomes framework.

-

Changing the status of offender, where it’s a child, in cases of “non-aggravated requests for indecent images” from suspect to person of interest.

-

Implementing a process which will ensure all unexpected and non-suspicious deaths are recorded.

- Updating the Home Office counting rules to ensure it reflects the requirements of modern slavery incident recording.

- Reviewing the notifiable offence list.

Review of the National Standards of Incident Recording

The Policing Productivity Review Team has instigated a review of the National Standards of Incident Recording. These standards were introduced in 2011 to ensure common recording practices across policing. Nevertheless, police forces interpret or implement them differently. For example, some police forces resolve up to 60 per cent of their calls without recording an incident or contact log, whilst at least nine forces report that they create a record for every call. In addition, the National Standards of Incident Recording do not help in the context of online contact.

It is estimated that annually there might be about 40 million calls for service to the police through 999 and 101 telephone numbers[footnote 34]. Call takers spend an average of 14 minutes recording and risk assessing an incident on a command-and-control system[footnote 35]. One force (which records all contacts) recorded almost 1.7 million incidents and contacts in 2022/23. If the new standards allow that force to resolve 60 per cent of their calls without creating a record, this has the potential to save them as many as 200,000 hours a year[footnote 36].

The review will focus on areas where the National Standards of Incident Recording does not provide clear standards (that are understood by all forces in the same way), to bring out clarity and effectiveness in processes:

-

Changes in the way police contact centres operate including use of digital contact methods and first contact resolution.

-

Use of risk assessment processes (THRIVE[footnote 37] and RETHRIVE)

-

Improvements to recording of antisocial behaviour, missing person and transport incidents (including pursuits)

-

Embedding Right Care Right Person, the Violence Against Women and Girls Strategy and Operation Soteria into recording practices

-

Incident closing processes

Recommendations will be submitted to the NPCC in the autumn and to the College of Policing, once agreed, for immediate implementation. An annual review of the National Standards of Incident Recording should subsequently take place to ensure they remain up to date and relevant.

Recommendations

Following the work of the Review with NPCC leads, significant changes were made to the Home Office counting rules – the way in which crime is recorded- in April 2023.

To ensure the productivity gains continue, the Policing Productivity team and the national police lead for crime data integrity should report progress to ministers every six months. The first of these reports should be submitted by 31 December 2023.

Proposals for further changes should be brought forward by the national police lead for crime data integrity by October 2023. HMICFRS should ensure their inspection approach reflects the changes. (Recommendation 6)

Pre-charge files

In addition to looking at productivity improvements in the management of mental health demand and Home Office counting rules, the review has also focused on a specific part of the criminal justice process: pre-charge files, i.e., the case material that police send to the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) for charging consideration.

The average time between the offence and the charge or summons has increased substantially, from 14 days in 2016 to 44 days in 2023[footnote 38]. The NPCC argues that the introduction of Data Protection Act 2018, the Director’s Guidance on Charging and the Attorney General’s Guidelines on Disclosure, compounded by the sharp increase in the volume of data and additional responsibilities for public protection and safeguarding, have created significant resourcing requirements to the criminal justice process[footnote 39]. The Review has worked to quantify the scale of this.

Streamlining the pre-charge file requirements

On 31 December 2020, the revised code of practice to the Criminal Procedure and Investigations Act 1996, the Director’s Guidance on Charging (sixth edition) and the Attorney General’s Guidelines on Disclosure came into effect, introducing significant changes to the criminal justice processes, impacting police forces and the CPS. This included:

- Introduction of the Investigation Management Document, requiring police to complete a 17-part form for almost all pre-charge files to CPS.

- the requirement to provide and redact all material that falls under the “rebuttable presumption” categories in the pre-charge files to CPS, irrespective of whether the police assesses that material as capable of meeting the test for disclosure.

- higher disclosure schedule requirements on police for CPS pre-charge files.

These changes “place greater requirements on the police to produce material at an early stage, rather than when the case is already in the court system”[footnote 40], and dramatically increase the amount of material that police investigators have to process.

To substantiate this, the Review worked with four police forces (Durham Constabulary, Kent Police, Leicestershire Police and Merseyside Police) to quantify the time investigators spend building a non-complex pre-charge file for CPS decision. Sampling from forces showed that between 4.8 and 23 hours[footnote 41] are required for each file, an average of 14 hours (of which about 20 per cent is spent on redaction). There are large variations: even within the same force, a similar spread exists depending on the individual cases and crime types.

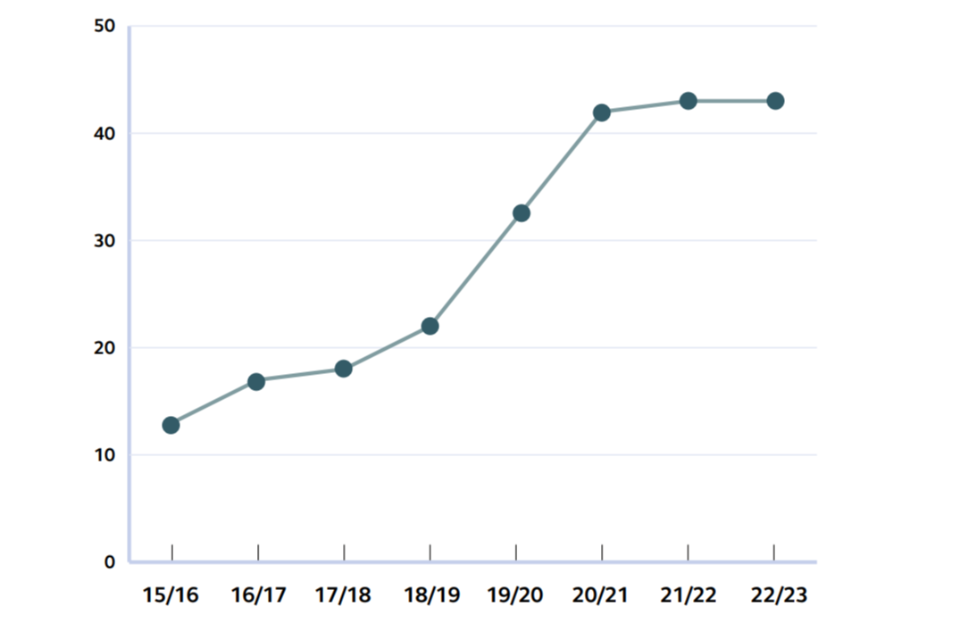

Figure 3: average days between offence and charge/summons

For complex cases, the time required to build a file is of course even higher: Kent Police estimated that child abuse casefiles take an average of 112 hours. Across all crime types (complex and non-complex) it takes 63 hours.

Workload has increased in a number of ways:

-

A review by Surrey Police found the requirement for investigators to complete the Investigation Management Document has added an average of three hours of work when completing a file[footnote 42]. If we extrapolate this for every pre-charge file sent to CPS, this equates to 540,000 officer hours a year[footnote 43].

-

The requirement to provide everything that falls under the “rebuttable presumption” categories has inflated the volume of material (see next section).

-

Under the current requirements, police now have to provide full disclosure schedules for a pre-charge decision. “Put simply, if the police submitted 100 cases to the CPS under the old regime, about 75[footnote 44] would result in a charge and then require the officer to complete a file. Now, all 100 require a file (to be submitted) even though 25 will not ultimately result in a charge. This represents a 33 per cent increase, not only in workload, but in effort ultimately to no avail”[footnote 45]. The Review estimates that in 2022/23 the CPS decided to take no further action in relation to about 38,000 pre-charge files. Using the estimated average of 14 hours for officers to complete a pre-charge file, it means that about 532,000 officer hours were used to build full files that go no further[footnote 46]. This time usage should be minimised.

The requirements of the Criminal Procedure and Investigations Act code of practice, the Director’s Guidance on Charging (sixth edition) and the Attorney General’s Guidelines have added significant time to the work of the police investigator. Given that much of this material provided to the CPS is never going to be shared with defence, much of that time could not be classified as productive use of officers’ time. The Review recommends that these documents are reviewed to ensure that the criminal justice process (police and CPS) becomes more effective. Options may include:

-

Removing the need for the Investigation Management Document or reducing its need to Crown Court submissions only.

- Removing the requirement for investigators to send “rebuttable presumption” material to the CPS where this will not meet the Disclosure Test (unless specifically requested by the CPS).

- Introducing streamlined files for certain pre-charge decisions.

Lightening the redaction burden

The Data Protection Act 2018 requires police forces to redact all unnecessary personal information out of any material they send to CPS for review. A recent NPCC review[footnote 47] of pre-charge files from 2020 (i.e. before the changes) showed on average six items of “unused”[footnote 48] material for each file sent to the CPS. In 2023 files, that number had increased to 16 “unused” items, an average of 129 pages of text and 49 minutes of audio/visual material. Using Thames Valley Police methodology[footnote 49] of two minutes to review/ redact a page and 1.5 times to review the length of audio-visual material, the Review estimates that an average 5.5 hours is required to redact the material for each pre-charge file.

Redaction will always be required for files that progress to court – however police forces will have spent 210,000 hours redacting material for the 38,274 files that do not progress beyond CPS. This is an amount of time that would be much better served attending 100,000 domestic abuse incidents, or 130,000 burglaries. A legislative exemption to the Data Protection Act allowing policing in England and Wales[footnote 50] to share material with the CPS without redacting it, will remove this wasted effort. Redaction would, for the relevant files only, be undertaken by police post-CPS charging decision.

There are also technical solutions to reducing the time spent by forces on redacting the material that needs to be shared with CPS. About 770,000 hours are spent by investigators redacting text material annually[footnote 51], so even if digital redaction only achieved a 80 per cent saving in time efficiency (as per Bedfordshire Police evaluation), this could free up 618,000 hours of investigators’ time.

Auto redaction

Several police forces, including Avon and Somerset Police, Cleveland Police, Devon and Cornwall Police, Dorset Police, Greater Manchester Police, Merseyside Police, the Metropolitan Police Service, Thames Valley Police and Wiltshire Police have been exploring technical solutions to reduce the amount of time they spend manually reviewing and redacting case file material.

One example is Docdefender tested in Bedfordshire Police. The tool assists the reviewer by automatically highlighting the potential data that might need to be redacted. Time and motion studies have been conducted against the current approach. The data from this concluded that the use of DocDefender offered between 80 and 92 per cent time savings. Examples included the redaction of a phone download (578 pages equivalent) in 20 minutes (previously this have taken a couple of days), and the redaction of a 350,000 cells spreadsheet in thirty minutes (this would previously have taken four hours). Bedfordshire Police also report a decrease in investigator time spent redacting witness statements, with a potential efficiency savings of 18,900 police officer hours per annum.

Police Digital Services have been engaging with other forces exploring “auto redaction” and following a commercial process the aim is to ensure all forces have access to this kind of solution. Work has also begun to scope the requirements and market for audio and visual redaction, with a view to implementing it in 2024.

Improving the timeliness of charging decisions

Timeliness is a crucial factor in the effectiveness of the criminal justice process. “An important driver of victim disengagement is how long it takes to complete an investigation and to charge a suspect… Delays between a crime being reported and a suspect being charged, negatively impact the mental and physical health of victims, witnesses and the accused, who are often vulnerable”[footnote 52]. Delays may compromise the recollection of those required to give evidence[footnote 53] and result in more witnesses and victims withdrawing from the process, leading cases to collapse[footnote 54]. The delays affect confidence in the legal system[footnote 55] and police legitimacy – given the public-facing role of officers in that process[footnote 56].

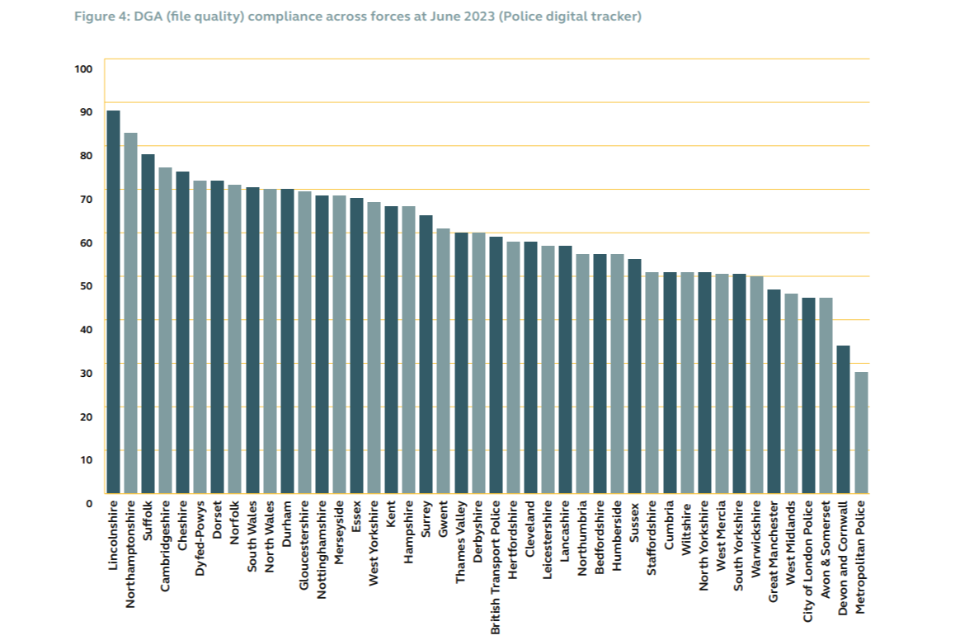

As noted, the average time between the offence and the charge or summons has increased substantially. It is not possible to disaggregate the time between offence and when police submit the file – however a high percentage of files sent to CPS do not reach the required standard in the first place[footnote 57]. This lengthens the process, as files go back and forth between CPS and forces. There are wide variations across forces, as illustrated in figure 4 below.

Clearly, police forces must track and improve the timeliness and compliance of their submissions. There is an opportunity to use the Model Process approach to compare different forces’ approaches and resource allocation to identify cost effective ways to achieve this. The Review is therefore recommending that case file timeliness and quality be added to the Model Process tool.

There are also delays on the CPS side. CPS aim to make charging decisions within 28 days but only meet this target 75.5 per cent of the time – and things are getting slower[footnote 58].

Because both sectors are measured on different performance indicators, there are different drivers at play. Police forces and the CPS need shared performance measures to incentivise the timely processing of files, for example through better use of early advice, where the CPS assist investigators in decision making, reducing the “no further action” outcomes. This whole-system approach would increase productivity on both sides.

The scope for police charging decisions is narrow. NPCC is seeking to identify and pilot some additional charging decisions being transferred from the CPS to high performing police forces (specifically relating to anticipated guilty plea offences being tried in Magistrates’ courts). This could provide an opportunity to relieve demand from the CPS, reduce the demand on police to complete pre-charge files for a CPS decision, and improve the timeliness of charging decisions.

Figure 4: DGA (file quality) compliance across forces at June 2023 (Police digital tracker)

Once charged, there is a significant delay before defendants are dealt with at court. Data from HM Court and Tribunal’s Service showed that by August 2023, there were over 400,000 cases waiting to be heard[footnote 59] and the backlog of cases in the Crown Court was the highest ever recorded (64,015). The median time from offence to completion at magistrates’ is 187 days and for Crown Court it is 398 days)[footnote 60]. To improve outcomes, the capacity gap in the CPS and the courts also needs to be addressed.

Shared performance measures across police, CPS and courts would provide common objectives and reduce the incentive for criminal justice partners to transfer workload to each other and allocate blame.

Recommendations

The Government should carry out an urgent review of guidance and practice on how police submit case files to the CPS, with the specific intention of making processes more time-efficient and productive. Ministers should consider the findings of that review by June 2024 (Recommendation 7).

Information sharing rules currently inhibit productivity in the criminal justice service. Two changes should be made:

-

The Government should introduce an exemption to the Data Protection Act by March 2024 to incentivise closer joint working between police and the CPS, including easier sharing of material at early stage for CPS advice (Recommendation 8).

-

Police forces must implement technical opportunities to redact material by September 2024; delivery of this must be a top priority for the Police Digital Service and the Policing Productivity Team.

The Home Office and criminal justice partners should align success measures for CPS and policing by March 2024. This should drive a more productive partnership approach to case management of crimes going through the criminal justice service (Recommendation 9).

CPS and NPCC should run a pilot giving some additional charging decisions – where a guilty plea is expected - to high performing police forces (Recommendation 10).

The Policing Productivity team should undertake further work to look at other ‘barriers’ to police productivity. Two important areas of focus are missing persons and how police custody operates. The Productivity Team should report back on this by March 2024 (Recommendation 11).

Future opportunities for productivity gains

There are opportunities to address other barriers to productivity. For example, there were about 60,000 incidents relating to children missing from care in 2021/22[footnote 61] (a large proportion of all missing children incidents) and it is estimated that missing person investigations use the equivalent of 1,500 full time officers per year[footnote 62] in terms of resourcing. This includes unwarranted demand such as officers recovering, caring for, or transporting children because a partner agency has a capability or capacity gap.

Another complex area that should be probed is the management of suspects, for example in police custody. There are many partnerships at play including health, social care, Courts and Tribunals, the Prison Service and criminal defence – and processes may not be as streamlined as they could be.

Policing productivity can be boosted by technological investments and process improvements, but first and foremost, officers and staff are driving the outcomes provided to the public: they are forces’ main asset. A capable, motivated and effective workforce, operating at a high standard is central to productivity.

Over 77 per cent of police force’s expenditure is on staff and officer costs[footnote 63]. As at 31 March 2023, the total workforce[footnote 64] across England and Wales was 233,832 with 147,430 full-time equivalent officers in post. The police officer uplift has provided much needed capacity and been used to manage rising demand and improve performance. There were also 6,841 special constables (headcount) and 7,322 Police Support Volunteers.

If productivity depends on the right resource being used for the right job, then getting the right mix of officers/ staff or specialists/generalists is important. The current targets and funding approach on officer numbers have resulted in some de-civilianisation. Workforce planning and resourcing need to recognise the important role of police staff, whether in a frontline capacity in roles that do not need warranted powers, and in roles that demand specific skills outside the police officer curriculum. There is appetite for future investment to be more focussed on proactive and preventative work to reduce demand, and to strengthen specialist skills such as forensics and digital investigation. As criminality becomes more sophisticated and technology advances, policing must improve digital and data literacy skills across its workforce.

We have not sought to undertake a root and branch review of all workforce aspects. Instead, the Review surveyed all police forces and identified some key areas where productivity could be improved. It also explored how sickness, training abstractions and limited duties are impacting on policing productivity.

Workforce

Strategic deployment of the workforce assets

Police officer numbers dropped from about 143,000 to 122,000 between 2010 and 2018 (-15 per cent), while staff numbers decreased even more sharply. During that time, allocation of resources was broadly made on the principles of preserving the frontline, developing “omnicompetence” of officers to make-up for the loss of specialist units, as well as moving resources to address inspection findings, in effect addressing urgent problems by shifting risks from one area to another. “Managing demand” became about reducing demand to more manageable volumes (triage, de-prioritisation), often at the expense of service quality (customer service, positive judicial outcomes).

Over the last three years, with the uplift (frequently supplemented by funding from local precept) creating a larger police workforce, forces have been able to increase capacity (full-time equivalent posts) in the design of some commands and to create new units without having to make a corresponding reduction elsewhere. Through a data request to every force, and insight from all chief constables, the Review sought to understand how and where forces have strategically chosen to deploy additional capacity, what value these investments are delivering, and what challenges remain.

Most forces (83 per cent) have used the opportunity of higher officer numbers to evaluate demand across the board, a majority using the Force Management Statement process introduced by HMICFRS. A number of forces (27 per cent) went further by reviewing their operating models, for example Derbyshire Constabulary and Wiltshire Police. For many, investment decisions are strongly driven by the views of external bodies (Police and Crime Commissioners and HMICFRS inspections (29 per cent), as well as professional judgment (37 per cent).

Clearly, there is a risk that chief constables use the main tool at their disposal (officer capacity) to address issues that might be tackled more effectively in other ways (staff, automation etc). Few forces raised this pitfall, albeit one chief constable explicitly sought whether “performance could … be achieved with changes to processes, systems, leadership …without a presumption that the answer was increased officer resources just because they were becoming available”).

Additional capacity has often been allocated to areas suffering from backlogs, delays and poor performance, and therefore workflows are expected to improve and with it the quality of outcomes (such as less case attrition to court). Because the increased capacity is provided by more experienced officers moving from response / frontline into specialist areas (in particular investigation and public protection areas), some forces expect that these areas will benefit disproportionately – and therefore become more productive.

The reactive choices in terms of capacity increases show that policing is still “catching-up”, “shoring up commands under pressure”, and trying to stabilise and strengthen the core functions of the policing model – patrol, neighbourhood and volume crime investigation. From a productivity angle, a majority of the capacity increases are not yet driven by “best bang for buck”, but by “squeakiest wheel”.

Importantly, a number of forces (but not all), have simultaneously implemented (or strengthened) performance measurements, governance and benefits realisation to accompany the officer increase. Some even assigned “each area of uplift a dedicated project manager and a benefits manager” to baseline and monitor “the benefits which are measurable improvements resulting solely from the investment of resource”. That said, impact monitoring and evaluation is patchy across forces.

An increase in officers does not in itself increase productivity. Without the right leadership, the same workload might be spread across more people without any improvement in output, quality, or outcome. The organisation might lose impetus to make further efficiency drives (for example through technological investments) simply because there are more people to carry out tasks. In Appendix, the Review is expanding on the major impact to date of the capacity investments made by forces. The Review has found the quality of data and evaluations inconsistent. Yet given their size, policing capacity investment should be project-managed, and their impact evaluated with the same rigour that forces might apply to a capital or technological investment. Robust data and performance management will help drive better results and show what produces best results. In time, these will support the policing sector articulate – and evidence- the public outcomes that investment in policing can deliver (in future Spending Review rounds for example).

A temporary experience shortfall

The main drawback of having increased the officer population so fast is a negative short and medium term impact on productivity because a large proportion of the total workforce lack experience. As at 31 March 2023, 36 per cent of all officers (where the length of service is known) had less than five years’ service (53,774 headcount).

In the very first stage, there is a demand on the system (where everyone is geared towards delivering the officer numbers, recruiting, vetting, training etc). During that time, the new workforce is not fully deployable (“very large numbers of students with 20 per cent protected learning time, lots of tutoring and double crewing and a level of inexperience”).

In a second stage, the new recruits need close supervision, guidance and support from first line managers (sergeants). This is at a time where the organisation does not have enough experienced officers at (or promotable to) sergeant level (and above) which forces are addressing through leadership development programmes and uplifts (e.g. Humberside Police’s new LEAD programme, Greater Manchester Police’s sergeant uplift).

Forces estimate that the uplift benefits will increase in stages and be fully realised by 2025. This highlights a third stage: new recruits will first help address demand in generalist areas but specialist areas will continue to experience shortfalls until the newer recruits have accumulated the experience to become, for example, PIP2 qualified detectives and armed response officers, cybercrime investigators, and roads policing officers etc. Forces will need time to translate capacity increase into capability improvements. There is a natural lag between investment decisions, having the people in place and fully realising the capabilities required from that investment.

Future capabilities

The Review asked chief constables about which areas they would be seeking to expand further, if there was another uplift in the future – and found many areas of consensus.

A focus on neighbourhood policing remains important. A chief constable highlights that “including the proactive and investigative capability – this is where policing by consent is maintained, and this is where problems can be addressed early and sustainably”. Whilst the uplift allowed forces to fill the most pressing resources gaps and consolidate core functions, in the longer-term, it is clear that they want to use the capacity gained to develop new proactive capabilities for early intervention and “essentially … go upstream of demand”.