Dementia and people with learning disabilities: making reasonable adjustments - guidance

Published 18 June 2018

Introduction

This guide aims to help staff in public health, health services and social care to provide services that are accessible to people with learning disabilities that have or are at risk of developing dementia. Additionally, this guide is also intended to be of use to families and friends of people with learning disabilities.

Under the Equality Act 2010, public sector organisations have to make changes in their approach or provisions to ensure that services are accessible to disabled people as well as everybody else. This guide (an update on the 2013 version) is one in a series of guidance looking at reasonable adjustments in a specific service area. The aim of these reports is to share information, ideas and good practice in relation to the provision of reasonable adjustments.

We searched for policy and guidelines that relate to people with learning disabilities and dementia; these can be found in the following chapters. We also looked at websites to find resources that might be of use in relation to dementia in people with learning disabilities.

We put a request out through a range of networks for people interested in services and care for people with learning disabilities. We asked people to send us information about what they have done to prevent dementia or to support people with learning disabilities who have dementia.

This report sets out what we found in our research. It also describes the online resources we found and where you can access them. This is followed by a selection of case studies and examples of reasonable adjustments made in relation to people with learning disabilities and dementia.

Why is this an important issue?

People with learning disabilities are living longer, thanks to improvements in health and health care, although life expectancy for people with learning disabilities is still shorter compared with the general population [footnote 1]. As a result, carers who look after people with learning disabilities are met with an increasing number who are developing dementia [footnote 2]. Achieving this will require reasonable adjustments to public health initiatives on prevention, NHS dementia diagnostic services, health and social care for people with dementia and their families, and services for people with learning disabilities.

Evidence and research

Prevalence of dementia in people with learning disabilities

Estimates of the prevalence of dementia in people with learning disabilities vary, in part because there has not always been good recognition, assessment and diagnosis.

Analysis of the data from a range of studies suggested [footnote 3]:

- age-related dementia of all types is more common at earlier ages in people with learning disabilities than in the rest of the population (about 13% in the 60 to 65 year old age group compared with 1% in the general population)

- across all over-60 age groups the prevalence was estimated at 2 to 3 times greater in people with learning disabilities

- people with Down’s syndrome are at particular risk of early onset Alzheimer’s disease

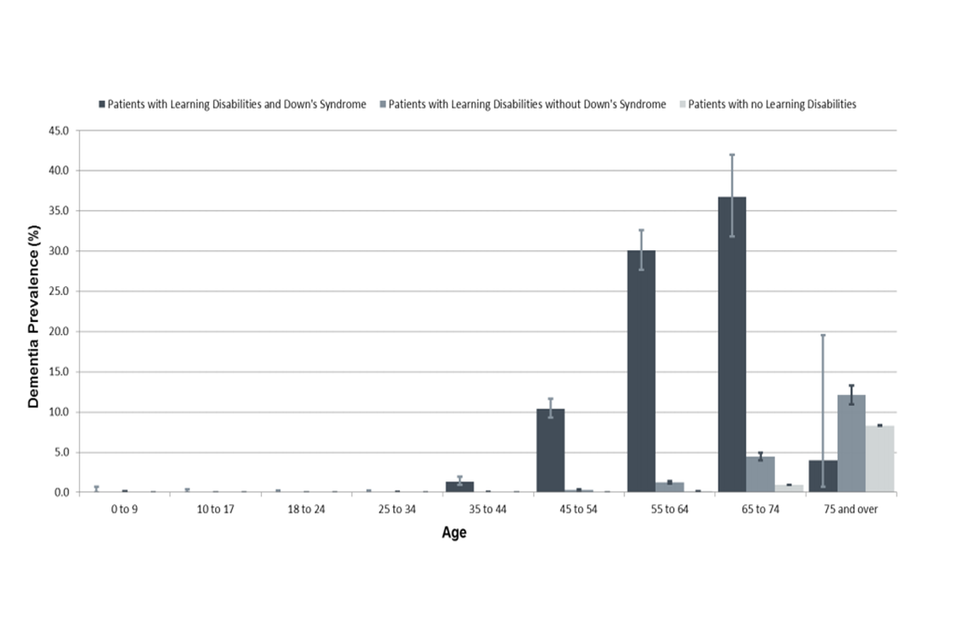

- data from GPs show that the number of people with learning disabilities diagnosed with dementia is 5.1 times the number expected, “if general population age and sex specific rates had applied” [footnote 4] (see Figure 1).

A graph showing the prevalence of patients with Down's Syndrome and learning disabilities compared to those with only Down's Syndrome and patients without leaning disabilities, grouped by age.

(Reproduced under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 from ‘Health and care of people with learning disabilities 2014 to 2015’, NHS Digital, 2016)

Prevention

Public Health England (PHE) estimates [footnote 5] suggest that 30% of the current incidence of dementia in the general population would be preventable by addressing risk factors such as:

- diabetes

- high blood pressure

- obesity

- inactivity

- depression

- smoking

People with learning disabilities are at increased risk of most of these factors, with the exceptions of high blood pressure and smoking [footnote 4]. People with Down’s syndrome are thought to be particularly vulnerable to developing dementia at younger ages and do so at earlier ages than others.

Information for people with learning disabilities, families and staff

Families and people with learning disabilities often want more information about the risks of dementia. However, in 2017 the Dementia Action Alliance found that people with learning disabilities were not always even told if they had dementia. The Alliance argued that people themselves, as well as family carers, should be supported to understand as much as possible about their condition and the options for treatment, care and support [footnote 2]. Resources such as ‘Talking together’ [footnote 6] can help with this.

Good information is also important for friends and partners, so they can understand what is happening to the person [footnote 7]. As noted by Towers and Wilkinson [footnote 8], starting such conversations can seem difficult, but people often feel relieved and less anxious once they start talking.

Early signs and diagnosis

Early recognition of signs that a person may be developing dementia offers an important opportunity to investigate and, if appropriate, seek a diagnosis. Recognition can be complicated because [footnote 9]:

- signs of other health problems (such as depression, sensory loss, or hypothyroidism) or reactions to a recent major life event [footnote 10] may be wrongly interpreted as the onset of dementia

- early signs of dementia may be missed (perhaps masked by other health problems) or attributed to the person’s learning disability or ‘challenging behaviour’

- people with learning disabilities who do not understand what dementia is may be less likely to seek advice if they notice their memory is not working as well as it used to

The onset of epilepsy in a person with Down’s syndrome later in life may be a strong sign that dementia is developing [footnote 9].

It is therefore important that:

- people who know a person with learning disabilities well are confident about noticing changes in the person’s health and behaviour and about seeking help if they are concerned

- people with learning disabilities have full annual health checks that cover physical and mental health, vision, hearing and medication review, with action taken on any health problems discovered

- people with learning disabilities showing signs suggestive of dementia should have the normal recommended investigations to identify any treatable causes of cognitive decline

- people with Down’s syndrome have a formal ‘baseline’ dementia assessment from age 30 so that any changes can be measured

In some areas, people with mild or moderate learning disabilities are supported to follow the local dementia pathway for diagnosis (perhaps with support from the local learning disability service to enable dementia services to make reasonable adjustments). In other areas, it is more likely that a person recognised as having a learning disability would be seen by the learning disability services.

Support

The principles of person-centred planning and maintenance of general health apply to support people with learning disabilities who have dementia, just as for people without dementia. The 2016 international summit on intellectual disability and Dementia [footnote 7] drew on international research and experience to recommend specific extra attention to:

- post-diagnostic support for the person, family carers and others close to or supporting the person: information, counselling, education and training, assessment of how the condition affects that particular person and how it may progress, and regular review

- the person’s environment: planning for the person to stay in familiar surroundings for as long as possible, designing adaptations to help the person make sense of the environment (for example, through the use of colour, labels, decluttering)

- helping family carers and staff to understand how their support may need to change over time as the person’s condition progresses, with decreasing emphasis on promoting independence and more on helping the person to enjoy life and sustain communication and relationships

- planning ahead for progression of the condition and end-of-life care: to include advance care planning and other tools to ensure that the person continues to have as much choice and control as possible

Similar points, rooted in a rights-based approach to supporting people to live well with dementia, were reiterated in recent guidance for support providers [footnote 11] and recommendations from the Dementia Action Alliance[footnote 2].

The summit report[footnote 7] also emphasised the importance of both practical and emotional support for family carers, noting that dementia services may not have had a lot of experience of working with families who have provided lifelong care and support. This topic was explored in more detail by Towers and Wilkinson[footnote 8], who described both the barriers family carers may face in planning ahead and a model to support them in undertaking a form of person-centred planning tailored to the circumstances of older people and their families[footnote 12].

Sensory engagement and dementia

Sensory engagement is the process of gaining the attention of one or more sensory systems of people and using that attention to support them or enrich their lives in some way[footnote 13]. The senses develop rapidly during the early weeks of life of the average person. Understanding what experiences (such as smell) elicit responses in early sensory development can be very helpful when supporting a person with dementia. People are often able to connect with early developmental sensory experiences long after they have stopped responding to and understanding other experiences. For example, the smell of a favourite food, combined with the sensation of it in the mouth, may be recognised. Sensory experiences can be used to communicate and to offer reassurance, which is especially valuable for people whose dementia has taken away their ability to understand and respond to other forms of communication and reassurance[footnote 14]. The sensory experiences most likely to engage a person with dementia will be described in a book due for publication in 2018[footnote 13].

Deterioration of a person’s sensory capacity and ability to process sensory information successfully can cause significant stress and distress, to the point where the person may lash out violently. A sensory understanding of the environment and personal interactions can help to prevent such incidents and also inform responses should they occur.

Sensory engagement has been used successfully with people who have dementia (including people with learning disabilities) to:

- enrich their lives through sharing sensory stories and sensory life stories[footnote 15]

- foster engagement in activities by setting them up in a way that maximises a person’s ability to interact with them

- promote independence by adjusting the environment and providing resources for activities that maximise a person’s chances of being able to do them

- support eating by providing food that offers the level of sensory stimulation appropriate to the individual and presenting it in a way that is accessible to the senses

- support behaviour in a positive way by reducing stress

- cultivate mental wellbeing by creating sensory environments and providing activities within those environments that reassure and calm the individual

Planning ahead: legal and financial matters

Early recognition that a person may be developing dementia provides an immediate prompt to consider planning ahead. While person centred planning may be well established in many learning disability services, plans do not always cover topics such as how (and by whom) decisions will be made in the future about financial and legal matters. Yet a person with learning disabilities may, at this early stage, have the capacity to make a will, draw up lasting powers of attorney (for health and welfare as well as for property and financial affairs) and consider advance care planning. For people who lack capacity to make such decisions themselves, it may still be possible to find out about their wishes and ensure that these are reflected in best interest decisions. The Mental Capacity Act provides for the Court of Protection to make a statutory will in accordance with the person’s best interests.

Research on access to legal services by people with learning disabilities and family carers[footnote 16] showed that many people were not confident about getting legal advice. However, some examples of supported decision-making were described in the 2017 Law Commission consultation on reforming the law of wills[footnote 17]. Solicitors had used creative approaches such as picture cards and counters to help people with learning disabilities to think about and express their wishes. The ‘Everyday decisions’ project[footnote 18] also found examples of people with learning disabilities who had put in place one or both types of lasting powers of attorney, but none of the participants had made a will. This research “found very low levels of awareness and/or willingness to engage with decisions on wills, power of attorney and advance decisions among care professionals”. It may be particularly important for people with learning disabilities that they are prompted to think about such matters.

End-of-life care

The principles of good end-of-life care apply to people with learning disabilities and dementia, just as for people without dementia. Evidence, policy, resources and practical examples of good practice are set out in a previous reasonable adjustments guide[footnote 19].

One specific consideration emphasised in some of the literature on people with learning disabilities and dementia[footnote 20] is that people may find it more difficult as their condition progresses to express that they are in pain. Pain might be communicated through changes in behaviour and these could be attributed mistakenly to the person’s dementia. Extra care is needed to check for and deal with possible causes of pain.

Policy and guidance

Policy and guidance on dementia in the general population

This section describes government policy on dementia in the general population, not specific to people with learning disabilities[footnote 21]. This emphasises prevention, early diagnosis, inclusion (for example, through dementia-friendly community development) and good support for people living with dementia and their families, from diagnosis through to end of life care.

Recent guidance from PHE[footnote 5] says that the risk of developing dementia can be reduced by helping people to:

- eat well

- reduce alcohol consumption

- stop smoking

- be more active

- develop and sustain social relationships and connection with others

This ‘healthy lifestyles’ message fits well with other public health advice. The guidance advises that “what is good for your heart is good for your brain”.

Building on earlier PHE guidance[footnote 22], the range of interventions proposed covers:

- population level: including attention to the built environment, promotion of healthy lifestyles, and dementia awareness programmes for health professionals as well as the public

- community level: support for healthy living, action to combat social isolation and loneliness, and support for living well with dementia

- family and individuals: make every contact count (by identifying people at risk, promoting healthy behaviours, advising on risk reduction), ensure people know where to turn for advice and diagnosis, support families

A dementia profiles tool provides indicators that allow local commissioners (both NHS and local authority) and providers to benchmark their current practice against other clinical commissioning groups, local authorities and England.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), together with the Social Care Institute for Excellence, issued guidance on support for people with dementia and their carers in 2006 [footnote 23]; at the time of writing this is under review, with an intended publication date of June 2018. The guidance set out principles and recommendations covering:

- Information and training to improve awareness and understanding of dementia (including in acute hospitals and in services for younger people at risk)

- Preliminary assessment in primary care, with referral to specialist memory services for comprehensive assessment and coordination of care planning

- Post-diagnostic support, including information, discussion of implications and options, and psychological support as required for both the person and family carers

- Person centred plans to promote and maintain independence for as long as possible, with a mixture of interventions according to the exact diagnosis and the person’s circumstances

- Assessment of carers’ needs and preferences, with psychological and practical support offered as appropriate

- Observance of the Mental Capacity Act principles, and good communication with and involvement of the person themselves and close family and friends

- Co-ordination and integration of health and social care services

- Interventions such as cognitive stimulation programmes, drug treatment, investigation of symptoms or behaviours not related to cognition (and responses such as sensory engagement), and psychological interventions for depression or anxiety

- Environmental design such as lighting, colour schemes, floor coverings, signage and assistive technologies to help the person to make sense of the environment and to maximise the person’s independence

- Palliative and end of life care, including advance care planning and attention to pain assessment and relief

NHS England’s ‘Well pathway’, accompanied by an implementation guide and resource pack set out a transformation framework to deliver the aims and standards of:

- preventing well

- diagnosing well

- supporting well

- living well

- dying well

These should be underpinned by improvements in research, joint working, commissioning, training and monitoring.

Skills for Care and Skills for Health developed a set of ‘Common core principles for supporting people with dementia’ to guide training for staff in health and social care’. The principles covered:

- awareness and recognition of early signs, and support to gain a diagnosis

- sensitive communication; respect and support for family carers

- promotion of independence and meaningful activity

- recognition of and response to distress

- support for team members and working jointly with others

Each principle was supported by a set of indicative behaviours that staff should demonstrate. The guide included advice and resources for service managers on assessing and meeting training needs to make their services ‘dementia-friendly’.

Policy and guidance on dementia in people with learning disabilities

NICE guidance on mental health in people with learning disabilities[footnote 24] and the accompanying quality standard added some specific points to its guidance on dementia in the general population:

- the annual health check for people with learning disabilities should include a review of mental health, including signs of dementia, especially in adults with Down’s syndrome

- people requiring an assessment for dementia should be referred to a clinician with specialist expertise in the mental health of people with learning disabilities

- assessment for dementia should be supplemented with tools devised for use with people with learning disabilities

- interventions (such as psychological or drug treatments) should be adapted to the individual

The recent NICE guideline on the care and support of people growing older with learning disabilities reinforced the importance of obtaining a baseline assessment, attending to family carers’ needs (including the possibility of mutual caring relationships) and planning for the future.

The British Psychological Society and the Royal College of Psychiatrists produced very comprehensive guidance[footnote 3] on the assessment, diagnosis, interventions and support of people with learning disabilities who develop dementia. This provided much more detailed advice on assessment approaches and tools, exclusion of other conditions and the possible course of dementia. Considerable emphasis was placed on supporting the person, family carers, friends, peers and support staff to understand the diagnosis and the possible course of the condition, and involving the person and those important to them in exploring and developing individualised support options (including emotional and practical support for families).

Life story work can be valuable to underpin person-centred support and the guidance drew attention to the importance of considering ethnicity and culture. Detail was included on the recognition and management of health conditions that are specifically associated with advancing dementia, such as epilepsy, sleep disorders, pain and gastrointestinal disorders. The characteristics of ‘capable environments’ were described, offering advice about a number of simple ways of maximising independence and reducing anxiety. For example, changes in the way a person with dementia perceives colour, depth and shadow effects may cause confusion and distress that can be alleviated by thoughtful design. A substantial section of the guidance covered interventions, including psychological support and drug treatments, alongside attention to the basics of care such as good nutrition and hydration. A recommended outcomes tool was attached; this took account of the possible stages of progression.

Guidance for GPs on diagnosis and management was developed by NHS Northern England Clinical Networks, based on the guidance described above. This described the possible clinical presentations of dementia in people with learning disabilities and offered recommendations for screening, referral and the design of support.

Resources

Fact sheet about dementia in people with learning disabilities Plain explanations about diagnosis and support (Alzheimer’s Society)

Information about dementia for families and support staff ‘Living with dementia’ guide, plus booklets to support conversations with people with learning disabilities (Down’s Syndrome Scotland)

Guide for families about Alzheimer’s disease ‘Alzheimer’s disease’ booklet covering diagnosis and support (Down’s Syndrome Association)

Resource pack on the Mental Capacity Act for families and friends Sections explain how to use different aspects of the Act; section 13 covers lasting powers of attorney (HFT)

Guide for families and staff on planning ‘Thinking ahead’ guide on planning for the future (Together Matters)

Guide for families and staff on supporting conversations about ageing ‘Talking together’ guide to facilitating peer support activities to help people with learning disabilities understand about growing older and living with dementia (Together Matters)

Comprehensive guidance for staff Guidance on assessment, diagnosis, interventions and support (British Psychological Society/Royal College of Psychiatrists)

Guidance and accompanying quality standard Mental health problems in people with learning disabilities: prevention, assessment and management. Includes a section on dementia (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE))

Guidance with links to tools and resources Care and support of people growing older with learning disabilities. Includes a section on dementia (NICE)

Guidance for GPs Diagnosis and management information for GPs (NHS Northern England Clinical Networks)

Knowledge exchange website Open access resources on ageing, later life and dementia (Karen Watchman, University of Stirling)

Web page with resources and links Recommended reading, resources and stories about support and services (British Institute of Learning Disabilities (BILD))

Guide for support service providers Evidence summary and examples of how to provide good support (Voluntary Organisations Disability Group (VODG))

Multi-media learning and information resources Case studies, films, ‘hot tips’ briefings and discussion cards (MacIntyre)

Developing sensory stories and resources Series of guides and leaflets with ideas and advice (The Sensory Projects)

Recognising and managing pain Factsheet and guides for GPs, support staff and carers (Joseph Rowntree Foundation)

Easy-read and accessible resources about dementia

Easy-read factsheets on dementia Factsheets entitled ‘What is dementia?’ and ‘Understanding and supporting a person with dementia’ (Alzheimer’s Society and BILD)

Easy-read booklets on growing older, dementia and death Booklets in a ‘Let’s talk about… .’ series intended to support conversations on these topics (Down’s Syndrome Scotland)

Easy-read leaflets on dementia; photo bank Leaflets about dementia. Photobank of images related to dementia, which can be used to create new materials (NHS South of England)

Easy-read book and postcards on dementia ‘Jenny’s diary’ book and postcards for family, friends and staff to use to support conversations (Pavilion)

Easy-read guide on planning ahead ‘I’m thinking ahead’ book to help people to think and talk about plans for the future (Together Matters)

Easy-read guide on making decisions ‘Making decisions’ booklet: covers support for decision-making, lasting powers of attorney, and independent mental capacity advocacy (Office of the Public Guardian)

Easy-read guide to making a will Leaflet about how to make a will. (Note: the web page includes information that is only applicable to the Republic of Ireland, but the content of the leaflet is entirely transferable to the UK) (Inclusion Ireland)

Apps related to dementia

Helpful technology Examples of apps and other technology (not all free) and how they can help (Young Dementia UK)

Electronic memory aids Advice about how to use devices and apps (part of a series of web pages on memory aids, tools and strategies) (Alzheimer’s Society)

Resources for professionals (not specific to people with learning disabilities)

Guidance and accompanying quality standards Dementia: supporting people with dementia and their carers in health and social care (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE))

Guidance on promoting healthy lifestyles that can reduce the risk of dementia Health matters: midlife approaches to reduce dementia risk (PHE)

Guidance covering prevention and interventions Dementia: applying ‘All our health’ (PHE)

Dementia profile to enable data analysis across populations (PHE)

Resources to support the implementation of the 2020 challenge on dementia Guide to good care planning for people with dementia; ‘Well pathway’ setting out standards for each stage (NHS England)

Guide to training the social care and health workforce to support people with dementia Common core principles for supporting people with dementia (Skills for Care, Skills for Health, Department of Health)

‘Is your care home dementia friendly?’ Environmental assessment tool Set of questions and advice on how to use them (King’s Fund)

Living well through activity in care homes toolkit Practical ideas to support people with activities that are important to them. Includes training materials and audit tools (College of Occupational Therapy)

Pain assessment tool for people with advanced dementia Five item tool with clear descriptors (Massachusetts General Hospital)

Draft guidance on decision-making and mental capacity Includes guidance on supported decision-making. Expected publication date May 2018 (NICE)

Guidance and tools to support making care decisions in advance Comprehensive guidance, supported by information and educational resources (NHS Northern England Clinical Networks)

Advance care planning ‘Recommended summary plan for emergency care and treatment’ – approach to advance care planning being implemented in stages (A coalition of professional bodies including Royal Colleges, Resuscitation Council (UK) and the Care Quality Commission)

Conclusion

People with learning disabilities are at increased risk of dementia compared with the general population and people with Down’s syndrome are at particular risk of early onset dementia. Early assessment is important in order to exclude any other cause of signs such as confusion or behaviour change, to obtain a diagnosis and to plan appropriate support. Policy and good practice guidance encourage:

- prevention, with healthy lifestyles advice similar to that for heart health

- early assessment and intervention to help people live well with dementia

- environmental design to promote independence and confidence

- person centred support that changes emphasis over time from supporting independence to helping the person to enjoy life and sustain communication and relationships

- continued attention to maintaining good general health

- emotional and practical support for family carers

- planning ahead for progression of the condition and end-of-life care

These elements of support need to be underpinned by:

- good information for and involvement of people with learning disabilities, friends and families

- information and training for staff in a range of services to promote awareness of dementia and, for those supporting a person with dementia, to develop their skills and confidence

This guide includes a range of good practice examples and resources to support services in planning and making reasonable adjustments for people with learning disabilities who have dementia.

References

-

Heslop P, Blair P, Fleming P, Hoghton M, Marriott A, Russ L. Confidential Inquiry into premature deaths of people with learning disabilities (CIPOLD): Final report. Bristol: Norah Fry Research Centre, University of Bristol; 2013. ↩

-

Dementia Action Alliance. Meeting the challenges of dementia for people with learning disabilities: roundtable discussion briefing paper. London: Dementia Action Alliance; 2017. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

The British Psychological Society and the Royal College of Psychiatrists. Dementia and people with intellectual disabilities. Guidance on the assessment, diagnosis, interventions and support of people with intellectual disabilities who develop dementia. Leicester: The British Psychological Society; 2015. ↩ ↩2

-

NHS Digital. Health and care of people with learning disabilities: England 2014 to 2015, experimental statistics. Leeds: NHS Digital; 2016. ↩ ↩2

-

Public Health England [Internet]. [Updated 2018.] Dementia: applying ‘All our health’. ↩ ↩2

-

Towers C, Glover C. Talking together: facilitating peer support activities to help people with learning disabilities understand about growing older and living with dementia. London: Foundation for People with Learning Disabilities; 2015. ↩

-

Watchman K, Janicki M and members of the International Summit on Intellectual Disability and Dementia. Report of the 2016 International Summit on Intellectual Disability and Dementia, 2017. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Towers C, Wilkinson H. Planning ahead. Supporting families to shape the future after a diagnosis of dementia. In: Watchman K, editor. Intellectual disability and dementia. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London; 2014. p. 161 to 182. ↩ ↩2

-

Alzheimer’s Society. Learning disabilities and dementia. Factsheet 430LP. London: Alzheimer’s Society; 2015. ↩ ↩2

-

Wark S, Hussain R, Parmenter T. Down syndrome and dementia: is depression a confounder for accurate diagnosis and treatment? Journal of Intellectual Disabilities. 2014;18(4):305 to 314. ↩

-

Voluntary Organisations Disability Group. Staying put: developing dementia-friendly care and support for people with a learning disability. London: Voluntary Organisations Disability Group; 2017. ↩

-

Towers C. Thinking ahead: a planning guide for families. London: Foundation for People with Learning Disabilities and Together Matters; 2015. ↩

-

Grace J. Sharing sensory stories and conversations with people with dementia: a practical guide. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; forthcoming 2018. ↩ ↩2

-

Grace J. Sensory-being for sensory beings: creating entrancing sensory experiences. London: Routledge; 2017. ↩

-

Leighton R, Oddy C, Grace J. Using sensory stories with individuals with dementia. Journal of Dementia Care [Internet]. 2016 July 11. ↩

-

Swift P, Johnson K, Mason V, Shiyyab N, Porter S. What happens when people with learning disabilities need advice about the law? Bristol: Norah Fry Research Centre, University of Bristol; 2013. ↩

-

Law Commission. Making a will. London: Law Commission; 2017. ↩

-

Harding R, Tascioglu E. Everyday decisions project report: supporting legal capacity through care, support and empowerment. Birmingham: Birmingham Law School, University of Birmingham; 2017. ↩

-

NHS England in association with the Palliative Care for People with Learning Disabilities (PCPLD) Network. Delivering high quality end of life care for people who have a learning disability. Resources and tips for commissioners, service providers and health and social care staff. NHS England; 2017. ↩

-

Kerr D, Cunningham C, Wilkinson H. Responding to the pain experiences of people with a learning difficulty and dementia. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation; 2006. ↩

-

Department of Health. Prime Minister’s challenge on dementia 2020. London: Department of Health; 2016. ↩

-

Public Health England. Health matters: midlife approaches to reduce dementia risk. Public Health England; 2016. ↩

-

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Dementia: supporting people with dementia and their carers in health and social care. Clinical guideline CG42. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2006. ↩

-

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Mental health problems in people with learning disabilities: prevention, assessment and management. NICE guideline NG54. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2016. ↩