Health equity audit guide for screening providers and commissioners

Updated 24 September 2020

Drawing 1 (equality) shows a man and 2 boys watching baseball over a fence. All 3 stand on boxes but the shortest boy still cannot see. In drawing 2 (equity) the man stands on the ground and the shortest boy stands on 2 boxes. All 3 can now see.

1. Introduction

Identifying and addressing health inequalities is a legal duty for all screening services. All public sector organisations are obliged to seek to understand and address inequalities in service provision and access.

A health equity audit (HEA) is a process that examines how health determinants, access to relevant health services, and related outcomes are distributed across the population.

Health determinants encompass a range of factors including, but not limited to:

- individual characteristics

- individual behaviours

- the environment we live in

- broader social and economic factors (see chapter 6 of Health profile for England: 2017)

This toolkit provides guidance for public health professionals, screening providers and commissioners. It provides a series of questions to help develop an audit protocol that addresses 3 areas:

-

Identifying health inequalities for the eligible cohort of screening services.

-

Assessing health inequalities in relation to screening services.

-

Identifying actions you can take to help reduce inequalities.

This guidance is designed to be used in conjunction with Public Health England’s (PHE’s) generic Health Equity Audit Tool (HEAT). It has been tailored to be more specific to issues of relevance to screening services. Note that Public Health England was disbanded in 2021. Its functions were taken over by the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA), the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (OHID) in the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), and NHS England (NHSE).

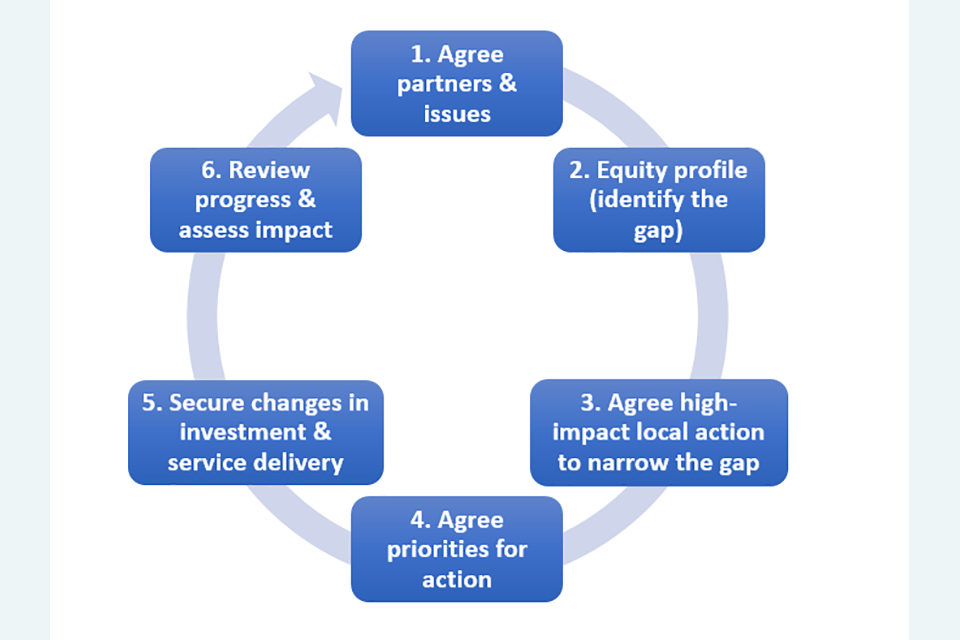

It is generally agreed that there are 6 stages in the HEA cycle (see figure 1 below), although the process should be flexible and iterative. HEAs are circular activities that should result in action planning. Senior leadership and good project management are important at all stages of the HEA process.

Figure 1: the health equity audit cycle (Health Development Agency, 2005)

The 6 stages of the HEA cycle are:

- Agree partners and issues.

- Equity profile (identify the gap).

- Agree high-impact local action to narrow the gap.

- Agree priorities for action.

- Secure changes in investment and service delivery.

- Review progress and assess impact.

2. Purpose of HEAs

Health inequalities are differences in health status between different population groups, defined by factors such as socio-economic differences, geographical area, age, disability, gender and ethnicity.

The aim is to fairly distribute resources in relation to need, and not necessarily equally (see the equality versus equity image at top of this publication).

Health inequalities in England exist across a range of dimensions or characteristics, including some of the 9 [protected characteristics of the Equality Act 2010]((https://www.gov.uk/guidance/equality-act-2010-guidance). These protected characteristics are age, sex, race, religion or belief, disability, sexual orientation, gender reassignment, pregnancy and maternity, marriage and civil partnership.

Health inequalities also exist in relation to screening services. Certain groups of people are more likely not to access screening services despite screening being universal for the respective target population. Victora C G and others (2000) in their publication in the Lancet describe how those most at need are less likely to take up new healthcare interventions.

Examples of characteristics associated with inequalities in screening can be found in section 4 below. For additional information, please refer to the NHS population screening inequalities strategy.

It is worth recognising that screening primarily benefits those at most clinical risk. If these groups are also less likely to take up screening, this may change the distribution of potential benefits and harms across the population. HEAs will help identify these groups and enable screening providers to improve coverage and reduce barriers to screening. Although this document seeks to highlight areas that screening providers should pay consideration to, it is by no means an exhaustive list. Local expertise and knowledge is invaluable in highlighting potential inequalities.

3. Scope

When carrying out HEAs it is important to define the scope and agree the purpose at the outset. This is a very important first step and it must be remembered that HEAs do not need to be all-encompassing and very broad.

The scope defined at the outset must be realistic. In order for resulting actions to be timely, a narrowly defined scope is acceptable if that is all resources and time allow. For example, some antenatal screening providers may find it helpful to prioritise an audit of their sickle cell and thalassaemia screening by 10 weeks gestation.

It is worth conducting HEAs, acknowledging and taking note of limitations (for example, lack of access to extensive datasets), rather than delay addressing health inequalities.

4. Preparing for HEAs

When preparing to conduct HEAs, you should consider the:

- target population

- inclusion and exclusion criteria

- geographical catchment

- aims of the screening service

- data available and types of analysis you want to undertake

- outcomes you are going to measure

For example, some outcome measures could come from standards documents or continuous improvement programmes. Note that increases in uptake alone may not indicate a reduction in health inequalities. It is possible for existing inequalities to be masked by an improving picture for overall uptake.

You may need statistical support to analyse data. You may need information governance approval to access data.

The HEAT and PHE Inequalities Strategy state that inequalities are likely to exist across a range of factors. These include (but are not limited to):

- socio-economic differences, for example, by:

- National Statistics Socio-economic classification (NS-SEC)

- employment status

- income

- area or regional variations, for example, by:

- deprivation level using index of multiple deprivation

- service provision

- urban and rural differences

- ethnicity, for example among black, Asian and other ethnic minority groups

- lesbian and bisexual women

-

men, who are less likely to be screened than women

- excluded and under-served groups, which may be missed within screening cohort identification, including:

- people with severe mental illness (see Population screening: access for people with severe mental illness)

- drug and alcohol users

- people experiencing domestic violence

- homeless people

- people in prison

- young people leaving care

- gypsy, travellers and boating communities

- transgender people

- people serving in the military and their dependants

- people with learning disabilities or physical disabilities where the service needs to make reasonable adjustments (see reasonable adjustments for people with a learning disability and cancer screening)

- young parents

- individuals with limited or no access to the internet

- new migrants

- pregnant women who book late or present unbooked in labour

- individuals whose first language is not English

Examples of regional variations by deprivation and ethnic group can be seen in videos explaining the abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) screening inequalities report.

5. Health inequalities across the screening pathway

There are 8 themes that describe the screening pathway:

- Population

- Coverage (see the NHS population screening glossary of terms)

- Uptake (see the NHS population screening glossary of terms)

- Test

- Diagnosis/intervention

- Referral

- Intervention/treatment

- Outcome

Screening pathways can also be described as flowcharts.

Consider potential health inequalities that may occur at each point along the screening pathway. The examples of potential areas to explore are not exhaustive.

Cohort identification and invitation

Does the call-recall process depend on being registered at a GP practice?

How are unregistered populations identified?

How is the cohort identified and contacted?

Are text messages sent? What about individuals without mobile telephone numbers?

Are letters sent? What about individuals with no registered address, or those in residential institutions?

If cohort identification depends upon gender, have transgender individuals been considered? See NHS population screening information for transgender and non-binary people.

What are the characteristics of the local population and local area? For example, include potentially under-served groups (see section 4 above) such as new migrants, the homeless, traveller communities, prison populations, pregnant women who book late or present unbooked in labour, and individuals whose first language is not English.

Provision of information about screening

Is the way individuals are required to access information about screening a barrier? For example, is information solely available online, in which case access to a computer or smartphone and an internet connection is required.

Are individuals able to make a personal informed choice? See definition of personal informed choice. An informed choice whether to accept or decline screening is based on access to accessible, accurate, evidence-based information covering:

- the condition being screened for

- the testing process

- the risks, limitations, benefits and uncertainties

- the potential outcomes and ensuing decisions

How accessible is the information provided about screening? For example, language and format. See information on Accessible Information Standard.

Are interpreters available?

Access to services

What is the geographical location of screening services and are they easily accessible?

Does the physical environment allow easy access to services? For example, is there access for individuals with disabilities?

Are individuals easily able to travel to appointments? For example, what are the availability and feasibility of transport options? Are there any restrictions on driving after any screening interventions, such as after dilating drops instilled during diabetic eye screening?

Are there any car parking charges and travel costs?

What are the times of screening services, and do they allow easy access for all individuals including, for example, single parents, carers and working individuals, including those on zero-hour contracts who may be unable to get paid time away from work for screening appointments.

May onward referral be required and, if so, how are referrals completed? For example, is it only via online self-referral?

Are any subsequent referral and treatment services easily accessible? Consider access to these and not just the screening services themselves.

Outcomes

Where possible, consider not only screening outcomes such as coverage or timeliness of appointments in the population audited, but also overall health outcomes.

For example, outcomes might include incidence, morbidity, and survival, if applicable. However, it is important to obtain population level data which might be for a larger geographical footprint because data at smaller area level can show skewed findings.

In smaller cohorts, small changes in numbers can result in large changes in percentages.

Consider:

- any regional variations and factors that may impact on these differences

- patient experience and how that impacts on future attendance

- individuals who have not attended their appointment

6. Data and evidence

Consider the important sources of data you need to identify health inequalities in your work.

Also consider the size of the population. In smaller cohorts, small changes in numbers can result in large changes in percentages.

What type of data do you need? Does your analysis require identifiable data to link with other datasets or make contact with individuals? Does the data hold enough information for a person to be identified indirectly?

Any data that can be used to identify a person is considered ‘personal data’ under the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and must be processed in line with the law – confidentially, securely and transparently.

Which organisation(s) controls the data? Is the data held in a system that is controlled by NHS England or a local service? Can data be shared, or are legal and ethical approvals required before data sharing?

Accessing anonymous data is usually much more straightforward than accessing identifiable and potentially identifiable data.

It is worth considering using published data (see the PHE Screening blog post on publishing and sharing data).

In some screening services, retrieving extensive datasets can be complex and very early advice from NHSE England (NHSE) should be sought. See guidance on data requests and research.

Published data

There are population screening key performance indicator (KPI) data for all 11 screening programmes

Annual data reports and statistics are available for:

- diabetic eye screening

- fetal anomaly screening

- infectious diseases in pregnancy screening

- newborn blood spot screening

- newborn hearing screening

- sickle cell and thalassaemia screening

- cancer services

Other sources of information include:

- the‘Fingertips’ tool (a public health data collection)

- the Strategic Health Assets Planning and Evaluation application

- a health equity audit presentation by PHE

- guidance on reducing health inequalities in AAA screening

- other published data

- interviews with staff, patients and screening and immunisation teams

7. Implementation, evaluation and feedback

The overarching goal of the HEA is to address inequalities. To make a difference, areas identified as priority action must feed into continuous improvement plans. These plans should be monitored for progress and outcomes evaluated to ensure inequalities are addressed.

Raise the profile of the HEA with leadership within providers, commissioners and other relevant stakeholders and use programme boards as a tool for sharing learning, agreeing and monitoring action plans. By using the information identified in the HEA, progress can be made to reduce the barriers to screening enabling people to attend.

Sometimes it is difficult to identify inequalities due to, for example, difficulties in capturing data for certain groups. This includes excluded and under-served groups (see section 4 above), or where data is not well captured, for example for ethnicity or learning disabilities. Examples of ways to improve identification of such groups include the development of IT solutions to capture data or improve recording of such data.

Additional challenges include identifying solutions to any inequalities that have been demonstrated. Learning from other screening providers and engaging local communities are useful ways of gaining insights and tackling inequalities in novel ways.