Performance of lateral flow devices during the COVID-19 pandemic

Updated 27 April 2023

Testing has been a vital tool in controlling the spread of coronavirus (COVID-19) since the start of the pandemic.

Initially, reliance for testing was on the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test. This is excellent at providing an accurate measure of the presence of the virus. However, its use was limited by laboratory capacity, and it had other disadvantages, notably the time it took to get results and the cost.

Rapid antigen tests – better known as lateral flow tests – potentially offered some crucial advantages. They did not involve a lab, results were produced within minutes and tests were much cheaper, enabling people to test themselves much more frequently than was possible with PCR tests. However, we needed to be sure they were accurate before they were used and to continuously monitor their performance once they were in use.

Here we provide a summary of our findings and the context of the introduction of lateral flow devices (LFDs). A detailed scientific report on the performance of the different LFDs used in the UK testing programme can be found at Lateral flow device performance data.

The differences between PCR and LFDs

PCR detects the presence of ribonucleic acid (RNA), the genetic material of the virus. LFDs detect the presence of an antigen (a type of protein) produced by the SARS-CoV-2 virus when it is active. PCR testing detects all RNA, even small fragments, but the virus is only infectious when the RNA is intact. The task for LFDs wasn’t to diagnose whether the individual had the infection, but whether they were infectious – would this person infect others?

Sensitivity of tests over the viral timeline: PCR and LFDs compared

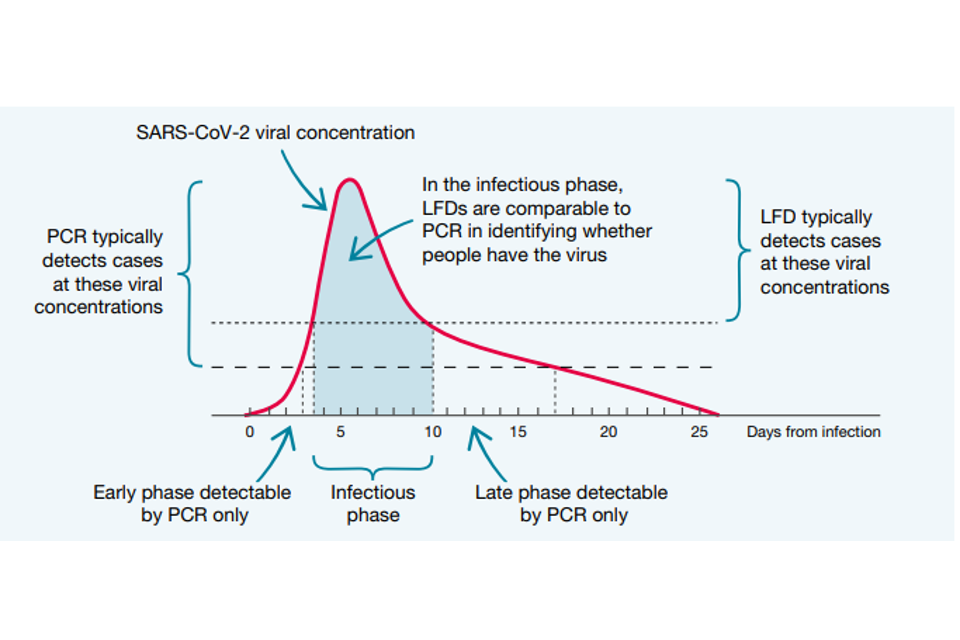

Both PCR tests and LFDs identify people when they are at their most infectious, typically 4 to 10 days after contracting the virus. As Figure 1 shows, PCR tests are much more sensitive than LFDs at the beginning and end of the infection timeline, but they are broadly comparable in the middle of the timeline. At the beginning, the greater sensitivity of PCR is certainly valuable, acting as an early warning that someone is about to become infectious.

However, that 2-to-3-day advantage may be offset by the time it would typically take to have a PCR test and get the results, compared to the near-instant feedback from LFDs. At the end of the infection, a PCR test may still give a positive result when the person has stopped being infectious, and the remains of the virus are still in the body.

Studies show that the level of viral concentration – how much viral genetic material there is in the sample – is a good indicator of how infectious the individual is. Viral concentration is measured as the number of RNA copies per millilitre (RNA copies/ml). Someone with a high viral concentration (greater than one million RNA copies/ml) is likely to be very infectious. Someone with a low viral concentration (less than 10,000 RNA copies/ml) is much less likely to be infectious. Medium viral concentrations were set between 10,000 and 1 million RNA copies/ml.

For LFDs to be useful in stopping the spread of infection, what was important was how they performed in identifying those with medium and high viral concentrations, because studies have shown that more than 4 out of 5 who caught the virus were infected by someone with a viral concentration greater than 10,000 RNA copies/ml.

The baseline studies

To ensure devices used across testing services were appropriate, safe and operated as expected, a robust quality assurance system has been in place throughout their use.

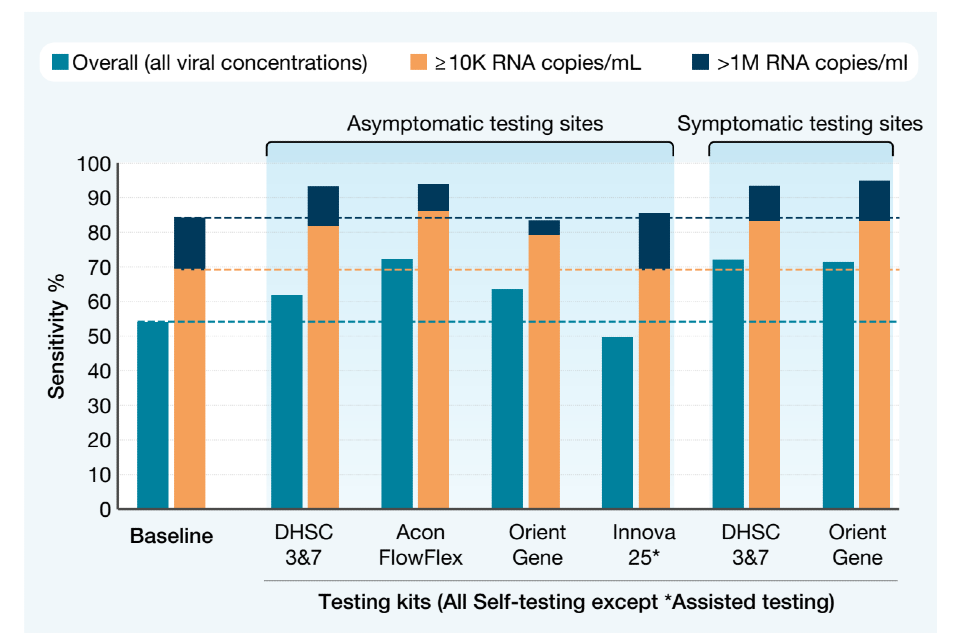

Initial validation studies were carried out at UKHSA’s Porton Down laboratories on all LFDs prior to them being used in the testing programme. Devices that passed the laboratory studies were then put into a real-world testing environment. People visiting walk-in or drive-in PCR testing centres were asked to also take an LFD at the same time for the purposes of the analysis. The sensitivity – percentage of correctly identified positive cases (as identified by PCR results) – could then be calculated.

LFDs were much better at identifying positive results in people with medium and high viral concentrations, and at the highest viral concentrations, that is the most infectious, the sensitivity was 84.5%. LFDs were less effective at detecting people with a low viral concentration, but this was considered acceptable as these people were so much less likely to be infectious.

These results formed the basis of an authorisation request to the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) which was granted with the condition that the performance of LFDs continued to be assessed, and that the results were at least as good as the baseline studies.

Lateral flow devices are effective at finding people with high viral loads who are most infectious and most likely to transmit the virus to others

Dr Susan Hopkins, COVID-19 Strategic Response Director to Public Health England and Chief Medical Adviser to NHS Test and Trace, March 2021

The ongoing evaluation

There was a need to maintain surveillance both to satisfy the regulatory requirements and because the context was under constant change – for example, the changing prevalence of the virus, the appearance of mutations and variants, and the introduction of vaccinations. In the light of these various changes, did LFDs still perform in line with, or better than, the baseline?

Around 70,000 paired tests were gathered from various settings in which testing was happening – for example work, school and college, home, healthcare settings – specifically for the purposes of evaluating LFD performance. The LFD result was then compared with the PCR result.

This chart shows the percentage of positive PCR cases also identified by the various LFDs, at the overall, medium and high viral concentrations. As you can see, the real-world tests showed a similar or higher sensitivity than at baseline for each of the approved LFD kits.

Sensitivity of the various devices, as used in different test settings

Conclusion

LFDs have proven themselves a vital tool for detecting the presence of SARS-CoV-2 when it is most infectious, and this has remained true through the appearance of new variants including Alpha, Delta and Omicron.

The results of ongoing evaluations have shown they are accurate at the medium and higher viral concentrations, where infectiousness is greatest. Their low cost and simplicity of use means that they can be deployed on a mass population basis, vital in a pandemic.

LFDs were used in the UK as a mass testing device earlier than anywhere else in the world, so this was revolutionary. The initial and ongoing testing made this important breakthrough in the UK’s ability to control the spread of COVID-19 possible.