International perspectives on early years

Published 20 June 2023

Applies to England

Executive summary

Around the world, countries are investing increasingly in the early years. In many cases, governments are driven by the need to provide safe and healthy environments for children so that parents can re-enter the workforce. However, countries also continue to respond to growing evidence of the benefits of high-quality early years provision, both for social and educational development.[footnote 1]

This report explores the aims and purposes of early years provision in an international context. Our insights draw on evidence from international research literature, and a survey and roundtable discussion involving academics and representatives of inspectorates from various European countries.

The insights are organised into 4 themes:

- availability and access

- workforce

- curriculum and pedagogy

- inspection and regulation

Throughout the report, we reflect on where England sits within the international context.

We found that many countries have implemented measures to increase participation in early years provision, although the difficulty of recruiting and retaining a highly skilled early years workforce continues to present challenges to this ambition. Many countries are recognising that the educational aspects of early years provision need more attention, to ensure that all children, regardless of background, are prepared for their next steps. However, many inspectorates continue to focus on structural factors, rather than on the quality of education. Ensuring that all children receive the high-quality early education that will give them the best start in life is a priority for Ofsted, and has been central to our work for many years.

Key insights

Many countries have implemented measures to improve children’s participation in early years provision. Many also target specific groups, such as children from low-income backgrounds. This is because they recognise that high-quality early years provision improves outcomes later in life, and that all children, regardless of background, should have access to this.

Many countries find it challenging to recruit and retain a highly skilled workforce. Staff shortages make it difficult to meet demand for provision, maintain preferred ratios of children to staff, and maintain the quality of provision. Highly skilled staff are better able to provide the high-quality early years provision that gives children the best start in life. Despite this, mandatory professional development is not common in the early years, particularly for adults working with children younger than age 3.

In many countries, early years provision focuses more on education as children get older and approach school age. Some countries do not have curriculum requirements for younger children (those under 3), and qualification and professional development requirements for staff are often lower. In England, the early years curriculum framework starts from birth. The curriculum is seen as crucial for guiding what children need to learn next. A well-considered curriculum, implemented throughout the early years phase, ensures that all children can make good progress. This reduces the attainment gap between children with lower starting points, including those from vulnerable groups, and their peers.

In most countries, the early years curriculum focuses on communication and language, social and emotional development, and physical development. As in England, these areas of learning are considered a priority because they provide the foundations for wider areas of learning and later educational success. Delegates who attended our roundtable discussion felt that a focus on communication and language is particularly important for certain groups of children, including those from low-income backgrounds, who may not have language-rich home environments.

Across countries, play is considered a crucial aspect of the early years. Most countries recommend a mixture of free and guided play. Delegates highlighted the importance of adults’ knowledge in facilitating play that leads to learning. In England, play is seen as essential for children’s development. Ofsted recognises the important role of adults in considering how best to teach what children need to learn (through play or otherwise), by considering what the children already know.

In many countries, particularly in settings for children under 3, inspections are not routine, regular or education-focused. When they do occur, they often focus on structural factors (such as staff qualifications and ratios) rather than on quality of education. In some countries, guidance for inspectors is not clear. This makes it difficult for inspectors to make sound judgements and to maintain the quality of inspections. Inspection and regulation are important for keeping children safe and ensuring that provision is of the high quality that will give children the best start in life.

Introduction

In England, children can attend early years provision between the ages of 0 and 5. This is an important developmental point in their lives. High-quality early years provision prepares children for success in later education by giving them the building blocks for future learning. The ‘Effective pre-school, primary and secondary education project’ found that children who attended early years provision, of any kind, achieved better GCSE results than those who did not. In addition, children who attended higher quality provision were more likely to achieve better GCSE results.[footnote 2]

International research shows that high-quality early years provision provides long-term benefits for both cognitive and social and emotional skills. Children who spend longer in early years provision have better educational outcomes.[footnote 3] International research has also found that high-quality early years provision particularly benefits children from low-income backgrounds. Accessible, affordable, high-quality provision not only supports family income by ensuring that parents can work, but also supports children’s development, well-being and success later in life.[footnote 4]

Internationally, the early years sector is usually referred to as ‘early childhood education and care’. In England, and throughout this report, we refer to ‘the early years’ and ‘early years provision’. The early years refers to the period when children are aged from birth to five (when they start Year 1). Early years provision refers to any provision children may attend during this phase, including both centre-based and home-based provision.

While the importance of the early years is widely accepted, early years systems vary around the world. Across, and even within, countries, people have different views on the role and purpose of early years provision. These views are often on a spectrum that has pure education at one end and pure childcare at the other. Many see early years provision as some combination of the 2. The length of the early years phase also varies across countries. For example, in many countries, the early years phase continues until age 6 or 7, when children start school in those countries.[footnote 5]

Given the importance of early years education, we welcome the opportunity to learn from the international early years research base and from international early years experts. We will use this learning to inform our practice, and to help ensure that all children get the best start in life.

How we gathered our insights

In autumn 2022, we carried out a review of international early years research. We included research that referred to more than one country. This included international data gathered by bodies such as the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and Eurydice, and wider policy and academic papers.[footnote 6] We only included literature from 2018 onwards, to give an up-to-date representation of practice.

Following the literature review, we identified gaps in the evidence base (for example, around home-based provision), and areas where further insights would benefit our understanding. This included seeking perspectives and experiences from individual countries, beyond the largely descriptive data offered by literature.

To get a broad range of perspectives and views, we contacted delegates from academic and inspectorate backgrounds, from a range of European nations. We invited the delegates to complete a survey and attend a roundtable event. The survey asked for the delegates’ opinions about the biggest issues facing the early years sector. The survey was completed in November 2022 by 12 of the delegates, representing 12 nations.[footnote 7] In December 2022, a total of 15 delegates attended the online roundtable discussion, representing 13 European nations.[footnote 8] The roundtable discussion focused on the evidence gaps identified in the literature: curriculum and pedagogy; home-based provision; and inspection and monitoring.

This final report gives an overview of literature about the early years in an international context. Throughout the report, we highlight data from the survey and roundtable discussion, where delegates provide further insights. We also reflect on where England sits within the international context.

Availability and access to early years provision

Summary

It is crucial that all children have the opportunity to access high-quality early years provision, because this is linked to more positive outcomes later in life. As in England, many countries offer a period of funded early years provision for all children. Many also offer additional funded provision, or priority access, for certain vulnerable groups. Research shows that these groups often benefit the most from high-quality provision but usually have poorer participation. Despite efforts to increase participation in the early years, a shortage of places continues to be a barrier in many countries. Some countries have expanded the offer of funded places, as has been proposed in England, but struggle to meet demand, particularly for younger children. This is often due to workforce shortages.

Types of setting

There is a broad range of early years provision in England, and across many countries. Provision may be centre-based or home-based. Within these 2 categories, there are many types of setting. Centre-based provision includes day nurseries, pre-schools, kindergartens and crèches. Home-based provision includes childminders, nannies and care by relatives.[footnote 9] In some countries, home-based provision makes up a large proportion of the early years provision. In France, it is the most popular form of provision for children under 3. In other countries, it is much less common.[footnote 10] In England, childminders offer around 14% of the total places in England.[footnote 11]

In England, we have a ‘split system’. In split systems, children move to a different type of setting at a certain age. For example, at age 4, most children in England move to a school-based Reception class. Reception classes help prepare children for their next steps, for example the transition to key stage 1. Many other countries, including Italy and the Netherlands, also have a split system. Children in split systems overseas usually move to a different setting at age 3. In some countries, different settings in the split system have a different focus. Settings for younger children (usually below 3) focus mainly on childcare, whereas settings for older children (usually above 3) often provide education as well. Other countries, such as Finland and Norway, have a more integrated system. In integrated systems, children stay in the same early years setting until they start primary school. Most integrated systems focus on education throughout the early years phase.[footnote 12]

As in England, many OECD countries (for example, Ireland, Australia and the Netherlands) have a mixture of publicly and privately owned and operated settings. Public settings are not for profit and are often run by local authorities. Private settings are sometimes owned and operated by businesses and are therefore run for profit. Other private settings are operated by the voluntary sector (including charitable organisations such as churches) and are not for profit. Private settings may be self-financing (for example, funded by fees) or receive public funding. Younger children (for example, those under 3) are more likely to attend private self-financing settings, because in most countries, these children are not offered publicly funded provision.[footnote 13] In England, many private settings receive public funding, for example to provide 15 hours of free provision for 3- and 4-year-olds.

Participation

It is important that children’s participation in the early years is high. Access to provision, especially high-quality provision, is linked to healthy development and educational success. It also reduces social inequalities and attainment gaps between children from different socio-economic backgrounds.[footnote 14] Equal access to provision is also crucial for ensuring that parents, particularly mothers, can work.[footnote 15]

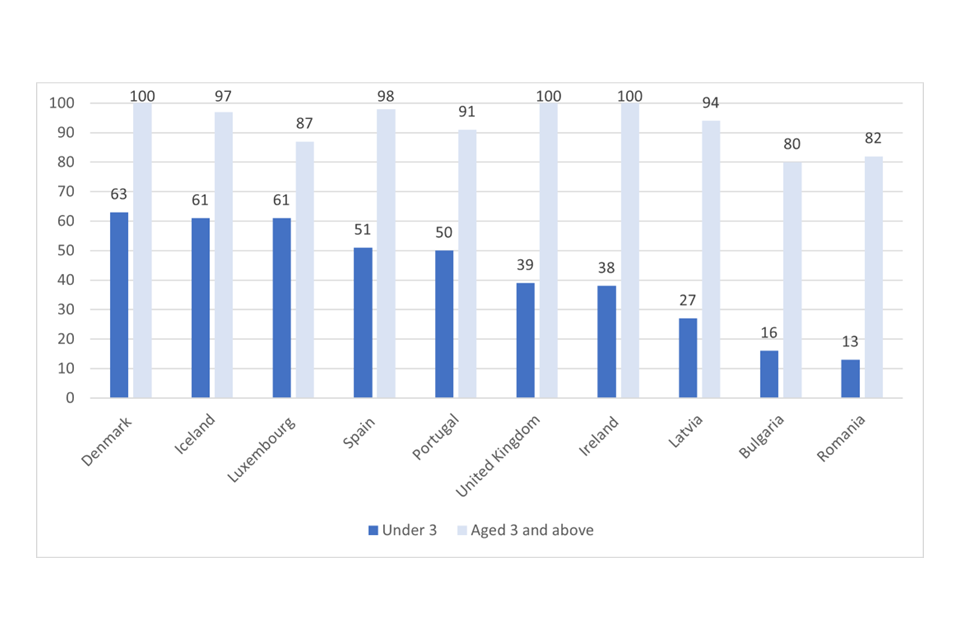

Children participate in early years provision at different ages across countries. Younger children (under age 3) are less likely to attend early years provision than older children. Participation is highest for younger children in Denmark, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Iceland, where over half of under-3s attend. In other countries, such as Bulgaria, Czechia and Romania, far fewer under 3s attend early years provision.[footnote 16] Across countries, participation in the early years is usually much higher for children over 3.[footnote 17]

Figure 1: Participation of children aged under 3 and aged 3 and above in early years provision across some European countries, as at 2018

Note: The data used for figure 1 was sourced from the Eurostat database, ‘Children in formal childcare or education by age group and duration – % over the population of each age group – EU-SILC survey’; ‘Pupils from age 3 to the starting age of compulsory education at primary level by sex – % of the population of the corresponding age.’ Latest available data (that included the UK) was from 2018.

View data in an accessible table format.

Participation in early years provision across countries is even higher for children aged over 4. In many European countries (for example, Denmark, Estonia and Iceland), over 95% of children aged over 4 attend early years provision. As in a number of European countries, around 100% of children aged over 4 attend early years provision in the UK.[footnote 18] In England, these children usually attend school-based Reception classes.

Participation rates in early years provision can be challenging to compare internationally. For example, they may be skewed due to parental leave policies. Some European countries do not provide parental leave, whereas others offer it for more than one year. This can reduce participation rates for children under 3 in countries that offer longer parental leave (such as Estonia and Norway), because children do not usually attend provision during the parental leave period. In addition, no internationally comparable statistics are available for home-based provision. This includes childminders, nannies, au pairs and care by relatives. In several countries (for example, in much of central Europe), large numbers of children attend home-based provision. Again, this may skew participation data.[footnote 19] Also, the number of hours children spend in early years provision varies across countries. Children in England spend far fewer hours per week in early years provision than the average across Europe.[footnote 20]

Affordability

Fees for early years provision vary greatly across countries and across different types of provision. England, and the wider UK, has some of the most expensive early years provision in the OECD.[footnote 21]

Unlike in England, fees are regulated in most European countries. Some place a specific limit on fees, or the limit may be a proportion of a family’s income or setting’s costs. For example, in Norway kindergarten fees are limited to 6% of a household’s income, and in Denmark, the income from fees cannot be more than 25% of a setting’s estimated gross operating cost.[footnote 22]

Many countries provide a period of funded early years provision. Countries are more likely to provide funded places for older children. However, some countries, including Denmark, Germany and Norway, offer funded places for children from a very young age (6 to 18 months), often immediately after the parental leave period. Almost half of European systems offer a funded place from age 3, and around three quarters in the last year of their early years phase. A growing number of countries, including Bulgaria, Greece and the Netherlands, are making attendance compulsory in the final 1 or 2 years of provision. This compulsory phase often explicitly aims to prepare children for primary education.[footnote 23] In England, all 3- and 4-year-olds are currently entitled to 15 hours of free provision a week, until they start Reception or reach compulsory school age (the term after their 5th birthday). Some 3- and 4-year-olds are eligible for an additional 15 hours of free provision a week, if their parents are in work.

In March 2023, the UK government announced plans to expand funded early years entitlement. It proposes that by September 2025, all children aged over 9 months, of eligible working parents, will be offered 30 hours of free early years provision.

In the roundtable discussion, there was a strong consensus that funding and affordability are important issues in the early years sector. Some delegates felt that their early years systems would benefit from more government funding. Others discussed upcoming reforms. For example, in the Netherlands, there are plans to extend heavily subsidised early years provision to all working parents, regardless of income. The importance of well-funded provision and its broader role in the early years was also highlighted:

Good levels of funding underpin both access and quality.

(Aline-Wendy Dunlop, academic from Scotland)

Access for all

In the roundtable discussion, delegates were concerned about participation rates for children from low-income families. These concerns are reflected in the literature. Across the OECD, children from low-income families are less likely than others to participate in early years provision.[footnote 24] This is worrying because, while attending early years provision has positive outcomes for all children, research shows that these outcomes are most positive for children from low-income backgrounds.[footnote 25] In England, children from low-income families are less likely than their peers to take up the full offer of funded provision.[footnote 26]

To increase the participation of children from low-income backgrounds, England offers additional free early years places, beyond the usual entitlement for 3- and 4-year-olds. For example, children whose parents receive certain benefits are eligible for 15 hours of free provision at age 2. In 2022, 92% of 3- and 4-year-olds were registered for the provision they were entitled to, but only 72% of eligible 2-year-olds were.[footnote 27] As in England, many countries have introduced means-tested support to increase participation of children from low-income backgrounds. For example, in Sweden, fees for one child are usually capped at 3% of the family income, with an additional maximum monthly cost. Families with lower incomes or more children pay less than this, or no fees at all.[footnote 28] The importance of encouraging children from low-income backgrounds to attend early years provision was highlighted in our roundtable discussion by one delegate from France:

In certain areas, overseas, rural territories or economic and socially disadvantaged areas or… near very big cities such as Paris, Marseille in the south, Lille in the north, children are welcomed [into early years provision] when they are 2 or 2 and a half because we know it is very important for the development of language and families benefit from [early years provision].

(Benedicte Abraham, inspectorate representative from France)

England also offers free provision at age 2 to other vulnerable groups of children, to increase their participation in early years provision. These include children in foster care, children who were previously looked after, and children with an education, health and care plan (EHC plan). Similarly, many other countries target children from vulnerable groups, to increase their participation. Approaches include offering funded provision from an earlier age (as in England), reducing fees or offering additional hours of provision. Some countries also offer priority access to certain groups. These measures target groups including:

- children under social protection or in foster care (for example, Hungary, Slovenia and Serbia)

- children whose parents cannot provide the necessary care (for example, Germany, Hungary and Portugal)

- children who are homeless (Ireland); children of women in shelters fleeing domestic violence (Greece and Spain)

- children whose family members are disabled or ill (Greece and Serbia).

Some countries also target children from certain regional or ethnic minorities. For example, Croatia, Cyprus and Albania have specific measures that support access to provision for Roma children. In Ireland, a programme offers free part-time provision for refugees.[footnote 29]

Most delegates in the roundtable discussion also expressed concern that not all children can access early years provision that is of high quality. This was largely discussed in the context of home-based provision. In the Netherlands, research has found that a parent’s socio-economic status is strongly linked to the quality of home-based provision that their children attend. Children with parents from low-income backgrounds are less likely to attend high-quality provision.[footnote 30] Another delegate explained that in Sweden, home-based provision, while decreasing overall, is becoming more popular in areas characterised by families of low income, lower levels of parental education and high levels of immigration. They explained that childminders in these areas often have limited language skills in Swedish. This may present problems for language development, which is typically a focus of early years provision. The delegate from Sweden discussed the findings of government research.[footnote 31] This has shown that many children who attend home-based provision in Sweden have lower knowledge and skills than children who have attended pre-school settings:

Children who attended [childminders] were not prepared enough for school. They lacked skills. We could also see that even though the number of [childminders] decreased, they seem to grow bigger in segregated areas, leading to segregating the children even more because the childminders don’t speak Swedish [most of the time].

(Maria Klasson, inspectorate representative from Sweden)

Availability

To ensure good levels of participation in the early years, it is also crucial that there are enough places to meet demand. Across Europe, there is a shortage of places for children under 3. The supply of places is usually better for children over 3. Nearly all countries provide an adequate supply of provision for children in their last year of early years education.[footnote 32] This may reflect the perceived purpose of the early years at different ages. Many consider education to be a more important aspect of the early years as children get older, for example to prepare them for starting school. In the roundtable discussion, delegates expressed concerns about the availability of provision in their countries. This included shortages of certain types of provision, for example flexible provision to suit parents’ shift work. They also discussed regional gaps in availability, as highlighted by a delegate from Italy:

In my country – Italy – the availability is very irregular, concentrated in a few regions and parts of regions, absent in the south, ranging from over 40% [for ages] 0 to 3 to 2% roughly… this is a major obstacle for a shared investment on quality.

(Susanna Mantovani, academic from Italy)

In some countries, poor availability of early years places means that not all children who are eligible for funded provision are able to attend. For example, in Germany, children are legally entitled to an early years place from the age 1. However, due to a lack of places, not all children who request a place are able to enrol. Children aged over 3 are more likely to receive a place than younger children. In many countries, shortages of places are the result of workforce shortages.[footnote 33]

In England, the total number of registered early years providers has fallen by 8% in the last year. However, the number of places has only declined by 2%. This is due to an increase in the number of places offered by each provider over time.[footnote 34] Data shows that many providers currently have spare places.[footnote 35] However, the total number of early years places, in particular places for children under 3, will need to increase as the government begins to implement its recent plans to expand funded places to 1- and 2-year-olds.

Workforce

Summary

It is essential that the early years workforce is highly skilled. Highly skilled staff are better able to provide the high-quality provision that gives children the best start in life. Qualification and professional development requirements vary across countries but are usually lower for adults working with younger children than for those who work with children approaching school age. This may reflect a stronger focus on education in the early years as children get older. As in England, recruitment and retention are a challenge across many countries, with many experiencing workforce shortages. There was a consensus among delegates that this is one of the main problems facing the early years sector. Shortages make it difficult to maintain preferred ratios and availability of places.

Qualifications

Research suggests that staff qualifications have an impact on the quality of early years provision. Studies from across the OECD show that staff with better qualifications are generally more able to deliver high-quality provision.[footnote 36] While qualifications themselves do not guarantee better teaching, evidence suggests that highly qualified staff are more effective at providing a stimulating environment and engaging in high-quality interactions with children. These features are linked to more positive well-being, development and learning outcomes for children.[footnote 37] Highly qualified staff may also be better equipped to understand children’s starting points and design the curriculum accordingly, as they know what the most important things to teach are. In the roundtable discussion, there was a strong consensus among delegates that working with young children is challenging. They explained that early years staff need a high level of knowledge, understanding and skill. One delegate highlighted the importance of maintaining a highly skilled workforce:

It is essential that young children are met by observant and knowledgeable practitioners who recognise children’s current development and are capable of building on this, whether cognitively, emotionally, socially or physically.

(Aline-Wendy Dunlop, academic from Scotland)

Qualification requirements for early years staff vary widely across countries. Adults working with older children (usually over 3) are generally required to hold higher levels of qualifications. Around three quarters of European countries require core practitioners working with older children to be qualified to degree level or equivalent.[footnote 38] Some countries (for example, France, Iceland and Italy) require core practitioners working with older children to hold master’s-level qualifications.[footnote 39] However, only a third of European countries require core practitioners who work with younger children (usually under 3) to hold degree-level qualifications.[footnote 40] This was highlighted by a delegate in our roundtable discussion. They explained that in Belgium there is no requirement for any specific training or qualifications to work with children younger than 2 and a half. However, from beyond that age, practitioners must have a bachelor’s degree. These differences in qualification requirements may reflect the way the focus on education increases as children get older and approach school age.

In many countries, core practitioners are supported by early years assistants. Assistants generally have lower qualifications, and qualification requirements, than core practitioners. In most European countries, there are no qualification requirements for early years assistants. Those countries that do use assistants (for example, France and Slovenia) typically require a level 3 qualification related to early years or education.[footnote 41]

In England, there are no minimum qualifications for staff in the early years. However, setting managers must hold an approved level 3 qualification, and at least half of all other staff must hold an approved level 2 qualification.[footnote 42] Most early years staff in England are qualified to at least level 3 (broadly equivalent to A level). Most early years staff do not hold a degree, except teachers in Reception classes, who usually do. In general, childminders are less highly qualified than staff in other provider types.[footnote 43]

Professional development

Across Europe, mandatory professional development is less common for early years staff than for primary and secondary teachers. Professional development is mandatory for all staff in only a few European countries (including Scotland, Serbia and Luxembourg). It is more often required for adults who work with older children (usually over 3).[footnote 44]

In England, however, professional development is expected of all early years staff. The statutory framework for the early years foundation stage (EYFS) states that ‘providers must support staff to undertake appropriate training and professional development opportunities to ensure they offer quality learning and development experiences for children that continually improves’. For example, providers must ensure that all staff receive induction training. This should also include training in safeguarding, child protection and health and safety.[footnote 45] However, there is evidence that access to professional development varies across the sector. Some settings offer limited access to training beyond mandatory training (for example, in safeguarding). This is often because they struggle to afford it.[footnote 46]

Workforce shortages

Workforce shortages are a challenge in many countries. In almost all OECD countries, more children are attending early years settings. This is due to a combination of higher birth rates, more mothers in paid work and increasing numbers of children being offered a funded place in provision. The workforce is struggling to keep up.[footnote 47] Across the OECD, there is an aging early years workforce. Almost a third of OECD pre-primary teachers are over 50. As these teachers begin to retire, workforce shortages are likely to worsen.[footnote 48]

In our roundtable discussion, there was a clear sense that delegates shared these concerns about the early years workforce. This was highlighted by one delegate from Italy:

In my country – Italy – recruiting [early years] professionals has become very difficult in the last years. It’s a threat for the development of [early years]. An emergency.

(Susanna Mantovani, academic from Italy)

There are many possible reasons why countries are struggling to recruit and retain early years staff. Low wages, feeling undervalued, poor working conditions and limited opportunities for professional development cause problems both for recruitment and retention. For those who do choose a career in the early years, it is not always long term. Many move on to a career in primary teaching instead, where there may be higher pay or greater perceptions of recognition. Across the OECD, countries also struggle to recruit men into the workforce. For example, men make up an average of only 3.2% of pre-primary teachers.[footnote 49]

Workforce shortages have serious implications for participation. As discussed earlier, Germany has been unable to meet demand after expanding the legal entitlement to an early years place to cover all children over the age of one. Workforce shortages have contributed to this, and the problem is likely to worsen in the coming years as staff retire.[footnote 50] One delegate highlighted their concerns about the German early years workforce. They described a cycle that is making the problem worse:

[A problem is] the lack of staff in the [early years] sector. This can lead to a loss of quality in the offer and furthermore to overload [on staff], institutions and the whole sector. [There is a] vicious circle [with] shortages of skilled staff leading to absenteeism due to overload.

(Daniel Turani, academic from Germany)

Workforce shortages lead to many other problems. A sufficient workforce is necessary to maintain preferred staff-to-child ratios. In the roundtable discussion, delegates also explained that workforce shortages make it difficult to provide both good-quality care and good-quality education. They suggested that, when staff numbers are limited, care (for example, ensuring that children are safe, fed and clean) may be prioritised over education. This was highlighted by the same delegate from Germany:

Poor working conditions can lead to loss of quality and more care than education in the end.

(Daniel Turani, academic from Germany)

As in many countries, shortages in the early years workforce are a concern in England. For example, increasing numbers of childminders are leaving the profession. There are currently 35% fewer childminders in England than in 2015.[footnote 51] The reasons for workforce shortages in England are similar to those seen in other countries. A review of the stability of the workforce in England identified 6 barriers:

- low income

- high workload and responsibilities

- over-reliance on female practitioners

- insufficient training and opportunities for progression

- low status and reputation

- negative organisational culture and climate[footnote 52]

The OECD has made various recommendations to address workforce shortages. To improve recruitment, it recommends increasing pay and requiring higher-level qualifications to improve career status. It also recommends increasing efforts to recruit more men into the workforce. To encourage people to stay in their early years career, it recommends improving working conditions and prioritising training and development opportunities to give practitioners a stronger professional identity and more career satisfaction.[footnote 53] Our delegates suggested various ways to address workforce shortages. These broadly aligned with the OECD’s recommendations, and included better salaries and working conditions, and making professional development a priority. They felt that these changes would improve the general status and reputation of a career in the early years. This was highlighted by one delegate:

Considerable strategic focus on establishing institutional opportunities for workforce development as well as on improving employment conditions is needed… to create work conditions that attract enough [early years] sector workers and… develop the [early years] workforce in a way that is fit to shoulder the tasks and strategic aims that lie at the core of the [early years] expansion.

(Ingela Naumann, academic from Switzerland)

Ratios

The ratio of children to adults in a setting is linked to the quality of interactions between adults and children, which has an important role in children’s learning and development.[footnote 54] Research evidence suggests that optimal adult-to-child ratios for early years settings are:

- 1 to 3 for children under 2

- 1 to 4 or 1 to 5 for children aged between 2 and 3

- between 1 to 10 and 1 to 17 for children aged 3 to 5[footnote 55]

Across OECD countries, ratios vary depending on the age of the children at a setting. In England, younger children require higher adult-to-child ratios. However, in most countries, ratio requirements do not align with the ‘optimal’ ratios recommended by some research. In OECD countries, average adult-to-child ratios are:

- 1 to 7 for children aged below 3

- 1 to 18 for children aged from 3 to the start of school[footnote 56]

The difference between the recommended ‘optimal’ ratios and the actual ratios is likely to be a consequence of workforce shortages. Countries are unable to require the optimal ratios if they are struggling to recruit and retain a sufficiently qualified workforce, particularly with increasing participation rates. In England, adult-to-child ratios are generally higher than the OECD average: 1 to 3 or 1 to 4 for children under 3, compared with the OECD average of 1 to 7 for children under 3. [footnote 57] In England, these ratios include qualification requirements. For example, to meet the 1 to 4 ratio for children aged 2, at least 1 member of staff must hold an approved level 3 qualification and at least half of the rest of the staff must hold a level 2 qualification.[footnote 58]

Ratio regulations for home-based providers are more complex. They are therefore more difficult to compare across countries. This is because childminders and nannies can look after children of different ages, and for different lengths of time. Across European countries, the maximum number of children a home-based provider can look after is usually around 4 or 5, but it can range from 3 to 8. Most countries also have a maximum number of younger children (usually under 3 years old) that can be in the setting.[footnote 59] In England, a childminder can look after a maximum of 6 children under the age of 8. Of these, a maximum of 3 children can be under 5, and a maximum of 1 can be under age 1.[footnote 60]

In March 2023, the government announced a change to the ratio requirements in England, to start from September 2023 (subject to parliamentary procedure). The required adult-to-child ratio will change from 1 to 4 to 1 to 5 for 2-year-olds. This is in line with the ratio in Scotland. It is still higher than the OECD average. The proposed ratio will also remain in line with the optimal ratio described in some research. The government will also give childminders more flexibility in ratios, including exceptions to the usual ratios when childminders are caring for their own children and for sibling groups.[footnote 61] These changes may help providers to keep up with demand, following the announcement that the number of children entitled to a funded place from 9 months old will expand by September 2025.

Curriculum and pedagogy

Summary

In the roundtable discussion, delegates highlighted that early years provision should provide both high-quality care and high-quality education. Across countries, a crucial purpose of the early years is preparing children for their next steps, including school. It is important that what children are taught in the early years contributes to their ‘readiness’ for these next steps. However, curriculums vary across countries. Some do not have curriculum requirements for younger children. Where there are requirements, areas of learning differ, particularly literacy (although sometimes learning is broadly similar, because objectives considered to be literacy in some countries sit under communication and language in others). As in England, many countries’ curriculums focus on areas of learning that provide the foundations for wider learning. These are communication and language, personal, social and emotional development, and physical development. In particular, delegates highlighted the importance of prioritising communication and language for children from low-income backgrounds, to prepare them for their next steps. There is a consensus across countries that play is a crucial component to how children are taught in the early years. In the roundtable, delegates recognised the importance of adult knowledge in facilitating play that leads to learning. As in other countries, in England, play is seen as essential to children’s development. It is important for adults to consider what children already know and can do, what they need to learn next, and how best to teach this.

The role of curriculum

A curriculum defines what is taught, often in the form of broad areas of learning and specific objectives within these. In England, all early years providers must follow the EYFS, regardless of the ages of children in the setting.[footnote 62] This includes 7 broad areas of learning but is not a curriculum in itself. Providers should decide how best to teach the areas of learning by creating a curriculum that works for their setting, considering the children’s interests and needs. Development Matters provides additional guidance on the early years curriculum, including examples of how to support children in achieving objectives.[footnote 63]

Curriculum expectations and requirements vary internationally. In many European countries, top-level guidelines provide a basis for regions, local authorities and settings to develop their own curriculum guidance. For example, in Italy, where there is significant regional autonomy, individual regions are responsible for providing detailed early years curriculums. In the majority of European countries, however, early years settings are free to develop their own curriculums, often for the entire early years phase, or part of the phase. In Liechtenstein, early years settings create their own curriculums for children aged 0 to 3. However, their kindergartens, for children aged 4 and 5, must implement the national curriculum. In some countries, only settings for children older than 3 have to set a curriculum at all. For example, in Bulgaria, Poland and Slovakia, there are no curriculum requirements for children under 3.[footnote 64]

The absence of a curriculum for children younger than 3 in some countries may be related to different perceptions of the purpose of early years provision. In some countries, early years provision, especially for younger children, is seen more as a form of childcare that allows parents to return to work. In our roundtable discussion, delegates suggested that this is a problem, and that all early years settings should provide both care and education:

The fact that there exist different settings for early education and childcare suggests that there still exists an understanding that these settings somehow provide something different – to children, parents, society. For children themselves, these 2 aspects of their environment (care and education) cannot be separated. Fully integrated settings that do not distinguish between education and care might thus help to ensure all learning environments are caring environments and that all care settings provide educational stimulation.

(Ingela Naumann, academic from Switzerland)

In many countries, as in England, top-level educational guidelines apply to home-based settings as well as centre-based settings (for example, in Norway, Sweden and France). However, in some countries, educational guidelines do not apply to home-based provision (for example, in Portugal, Spain and Poland).

Curriculum areas

Curriculum guidelines, where they exist, describe the areas of learning and development that should be the focus of early years provision. Regardless of age, the most common areas across Europe are:

- emotional, personal and social development

- physical development

- artistic skills

- language and communication skills

- understanding of the world

- cooperation skills

- health education[footnote 65]

These learning areas are broadly similar to the areas described in the EYFS. In England, the 7 areas of learning are:

- communication and language

- personal, social and emotional development

- physical development

- literacy

- mathematics

- understanding the world

- expressive arts and design[footnote 66]

In many European countries, some learning areas are only included in curriculum guidelines for older children (usually those aged over 3), for example numerical reasoning and reading literacy. Some countries also include early foreign language learning and digital education for older children. These learning areas are often taught in pre-primary classes.[footnote 67]

Delegates highlighted the learning areas that they felt should be the priority in the early years. These were:

- communication and language

- social and emotional skills

- physical development

They felt that these areas were important for several reasons. One was that these skills are the foundation for other areas of learning. Delegates felt that focusing on these foundations would have a long-term impact on children in school and beyond:

When talking about curriculum and pedagogy we also should focus on those skills, not only social, emotional, or self-regulation skills but also types of academic skills, that have this foundational nature and have long-term impact. My guess would be it’s not about learning letters or [phonics], because that’s quite easily acquired when children are… in school, but it’s more that deep understanding and deep vocabulary and self-regulation skills should be the focus of curriculum.

(Paul Leseman, academic from the Netherlands)

Another reason was that these foundational skills, particularly social and emotional development, help to create ‘well-rounded individuals’. There was a consensus in the roundtable discussion that a purpose of the early years is to develop individuals who can contribute positively to society. For example, a delegate from France discussed the value their ‘Maternelle’ settings place on the development of social skills. A core purpose of this is to support positive behaviours later in life:

The collective life at school is very important to well-being and social skills… from a very young age, educational actions that engage pupils in concrete situations… help build future citizens and demonstrate the values of solidarity and cooperation, which are essential to the French education. A fundamental aspect of the Maternelle is preventing rudeness, violence, and high-risk behaviour.

(Benedicte Abraham, inspectorate representative from France)

In England, we view these learning areas in a similar way. Out of the 7 learning areas described in the EYFS, there are 3 ‘prime’ areas. These are:

- communication and language

- personal, social and emotional development

- physical development

These are crucial for development and wider learning. According to the EYFS, the prime areas are ‘important for building a foundation for igniting children’s curiosity and enthusiasm for learning, forming relationships and thriving.’[footnote 68]

In the roundtable discussion, delegates recognised that these foundational skills were important for all children. However, they felt they were particularly important for certain groups of children. For example, delegates discussed the important role of the early years in providing foundational skills for children from low-income backgrounds. They recognised that some of these children may not have language-rich home environments[footnote 69] A delegate from Czechia highlighted the important role of early years provision in the social and language development of these children:

Especially for children from a socio-culturally disadvantaged environment, kindergarten fulfils a social function, where the child can meet peers and develop communication skills. Language skills and understanding of word content are very important for a child’s further education.

(Irena Borkovcova, inspectorate representative from Czechia)

Delegates also discussed children who are second language users. They highlighted that these children require a particular focus on language development. They felt this should ideally be in small groups, but that staffing shortages meant that this was not always possible. Some education systems (typically in central and eastern Europe) recognise the importance of maintaining children’s home language. In Estonia, financial support is offered for ‘Sunday schools’. These provide home language teaching in 17 ethnic minority languages for children over age 3. Some countries offer specific support for children from migrant backgrounds. This may include teaching about culture and developing their identity and cultural awareness.[footnote 70] In England, the EYFS advises providers on how to support children who speak English as an additional language. It states that providers must offer opportunities for children to develop and use their home language in play and learning. They should also ensure that children have opportunities to learn English to a good standard across the early years phase.[footnote 71]

In England, the 3 prime areas are strengthened and applied in the 4 ‘specific’ areas of learning. These are:

- literacy

- mathematics

- understanding the world

- expressive arts and design.

Whether and to what extent literacy is taught in the early years vary greatly across countries. Some education systems (including Denmark, Ireland and Italy) do not specify literacy as a learning area in the early years at all. However, these countries do set objectives under communication and language that overlap with early literacy objectives in other countries.[footnote 72] For example, in Denmark, the curriculum guidance talks about children engaging with books under the theme of communication and language. It says that children should have the opportunity to look at books, talk to staff about the content and ask questions about letters. The guidance also states that children should have access to writing utensils and paper.[footnote 73] In England, these would be considered part of the literacy area of learning. In our roundtable discussion, delegates suggested that too much focus on literacy and maths in the early years might be limiting. They felt this focus could delay the development of other necessary skills, such as learning to climb on a climbing frame or dressing independently. One delegate used Switzerland as an example. They explained that Switzerland’s focus on areas of learning other than reading and writing does not have negative long-term consequences for their children:

By 3 or 4, [children in Switzerland] definitely do not know how to read and write, and when we look at the end, when they come out of high school and they go on to further education, it doesn’t seem to harm them.

(Ingela Naumann, academic from Switzerland)

It is important to note that in England children are not expected to read and write at age 3 or 4. According to Development Matters (non-statutory curriculum guidance), children at 3 and 4 will be learning to:

- understand key concepts about print (for example, that English is read from left to right and top to bottom)

- develop their phonological awareness (for example, recognising words with the same initial sounds, such as money and mother)

- engage in extended conversations about stories

- write some or all of their name

- write some letters accurately

In Reception classes, when children are turning 5, they learn to read and write simple sentences using phonics and some common exception words (for example, ‘the’ and ‘go’). It is important that children in England begin to learn to read and write at this age because the English language is complex. For example, Finnish, Spanish and Italian have almost one-to-one consistency between letters and speech sounds. In contrast, in English, most sounds are represented by many letter combinations.[footnote 74]

Readiness for the next steps of learning

The role of the early years in preparing children for their next steps (for example, school) is recognised in many countries.[footnote 75] In England, the EYFS states that it ‘promotes teaching and learning to ensure children’s ‘school readiness’ and gives children the broad range of knowledge and skills that provide the right foundation for good future progress through school and life.’[footnote 76] This highlights the importance of the early years in preparing children for life more broadly, beyond simply starting school. The starting age for primary education varies across Europe, from age 4 (for example, in Northern Ireland) to age 7 (for example, in Sweden). In England, children start primary school in the school year that they turn 5.

Across countries, there is some variation in what ‘readiness’ looks like. This may be due to different perspectives on the appropriate level of development/learning at a given age. For example, the age at which a child is expected to read a simple sentence varies internationally. This may be due to varying complexities in the language code (for example, English has a more complex code than Italian). Another reason may be differences in the school starting age. Children who live in a country where they start school later (for example, 6 or 7) are often taught to read later than children who start school at 5.[footnote 77]

In general, being ‘ready’ suggests that a child should be emotionally, cognitively, psychologically and physically mature enough for primary education. In some countries (including Germany, Austria and Hungary), not all children transition to primary education at the typical age for that country. For example, a child’s entry to primary school may be delayed if it is thought that they are not ‘ready’.[footnote 78] In England, delaying entry to Year 1 is not common. Most children who start school later than usual are born in the summer.

In many countries (such as Italy and Finland), parents have a role in deciding whether their child is ready for primary education. In other countries, the early years setting is responsible for assessing school readiness. In Estonia, the early years setting issues a school readiness card for parents to show the primary school.[footnote 79] The card describes the child’s level in various development areas. These include the child’s cognitive skills, physical skills and areas that need further support. It also includes the opinions of speech therapists, and music and movement teachers.[footnote 80] In Croatia and Austria, the primary school a child is due to attend evaluates school readiness, usually following an assessment and/or observation of a child’s development. Sometimes, the school will consult specialists. In Serbia, schools evaluate all children enrolled to determine whether they should adopt an individual education plan or provide any additional support. In Montenegro, national standardised tests of school readiness decide whether a child should start primary education.[footnote 81] In England, requests to delay school entry are made to the school’s admission authority. The authority considers the views of the parents and early years provider, information about the child’s development and progress, and evidence from health or social care professionals.[footnote 82]

There is a period of compulsory early years provision in over a third of European countries. This not only improves participation rates, but also supports children in being ready for school.[footnote 83] In England, most children start Reception classes in the September after their 4th birthday. However, children do not reach compulsory school age until the term after they turn 5. This means that for some children (those born in the summer term), there is no period of compulsory early years provision, and they do not have to start school until Year 1. In France, the age for mandatory participation in early years education was recently lowered substantially. A delegate explained this was because the early years has a crucial role in supporting future learning, particularly for those from low-income backgrounds.

The age of mandatory education was brought down in France to 3 as of 2022 – as opposed to 6 years old formerly – in order to support young children’s social interaction and skills, to bolster their competence in spoken language, to ensure that [their vocabulary is sufficient], which is decisive for their future learning, especially in disadvantaged areas.

(Benedicte Abraham, inspectorate representative from France)

Many countries have a specific pre-primary programme that children must attend, lasting 1 or 2 years. The programmes aim to support the transition from largely play-based provision to primary education, where teaching happens in a more formal way. These classes are also often on the same site as the primary school, which again helps transition. To prepare children for school, some countries (such as Sweden and Serbia) introduce certain areas of learning in pre-primary classes. This may include early literacy, for example through vocabulary enrichment, storytelling and phonological awareness activities. In some countries, there has been an attempt to align the early years curriculum with the curriculums of later education phases.[footnote 84] For example, in Finland, a curriculum reform involving teachers, leaders, local authorities and researchers aimed to provide a continuous learning path from the early years into primary, and beyond into secondary education.[footnote 85] Pre-primary classes are broadly similar to Reception classes in England. The EYFS specifies that in Reception there should be a stronger focus on teaching the essential skills and knowledge in the specific areas of learning, including reading and mathematics. This helps prepare children for Year 1.[footnote 86]

Many countries recommend that early years staff and primary school teachers collaborate to help children with the transition from early years to primary education. This often includes passing on information to the primary school about a child’s achievements in the early years.[footnote 87] In England, the EYFS makes similar recommendations. It states that assessment should inform an ongoing dialogue between early years staff and Year 1 teachers about each child’s learning and development.[footnote 88]

Pedagogy

Curriculum refers to what is taught; pedagogy refers to how things are taught. We acknowledge that practitioners may use ‘pedagogy’ and ‘curriculum’ in different ways. Ofsted recognises that effective pedagogical choices (how something is taught) rely on a clear recognition and understanding of the curriculum (what is to be taught).

Countries that have top-level educational guidelines (for example, Sweden, Malta and Ireland) usually recommend specific pedagogical approaches. Most systems recommend these approaches for the whole early years phase, from birth to the start of school. Internationally, play is a core pedagogical focus of early years education.[footnote 89] Many countries recommend that play is embedded throughout the curriculum, taking the view that children learn through play, rather than spending some time learning and some time playing.[footnote 90]

There is a spectrum of different types of play. Free play is play that is spontaneous, with no set goal, and is initiated by the child. Guided play usually has a learning objective or goal and is supported by an adult in some way. Most countries recommend a mixture of free and guided play.[footnote 91] One delegate in our roundtable discussion highlighted recent changes to curriculum guidance in Sweden. Sweden now explicitly states that there should be a mixture of types of play:

[The curriculum states] a child has the right both to the free play that they start, but also a play which includes an active adult.

(Maria Klasson, inspectorate representative from Sweden)

As in other countries, in England, the statutory guidance recognises the crucial role of play, and recommends a combination of free play and guided play. It states: ‘Play is essential for children’s development, building their confidence as they learn to explore, relate to others, set their own goals and solve problems. Children learn by leading their own play, and by taking part in play which is guided by adults.’[footnote 92] This is highlighted in part 1 of our early years review series, where we discuss that play is essential for children’s development.[footnote 93]

In many countries, guidelines describe the important role of adults in listening to and encouraging children’s thinking during play.[footnote 94] In England, we also recognise the important role of adults in facilitating play in the early years. This includes providing stimulus material that encourages play, building on teaching that has already taken place. Adults also have an important role in increasing children’s knowledge for use in play. This may include their vocabulary, to ensure that play with peers is effective. Adults should have an in-depth knowledge of individual children’s starting points, to ensure that the children have the knowledge they need to engage in effective play. Children with lower starting points may need more explicit teaching to gain the knowledge they will need during play. Delegates in our roundtable discussion agreed that adults have an important role in the early years. They highlighted that supporting play effectively is complex and requires staff to have a deep understanding:

It’s really important to focus on education for our educators, rather than training, because there isn’t a recipe book to follow. They need to be able to respond intelligently and effectively to everything they see.

(Aline-Wendy Dunlop, academic from Scotland)

It is important to note that teaching and play are difficult to separate. During play, adults are likely to be teaching, unconsciously or consciously.[footnote 95] For example, an adult may teach counting to a child who is lining up toy cars. In England, ‘teaching’ refers to a broad range of ways in which adults help children to learn. This includes interactions with children during child-initiated play, modelling language, demonstrating, questioning, and providing a narrative for what they are doing. There are times when play may not be the most appropriate method of teaching. For example, if children are learning something for the first time, it may be better for them to be taught explicitly. Explicit teaching is an approach where adults introduce new information or skills to an individual or group of children. This can be effective in teaching children specific knowledge, for example how to fasten buttons on a coat. It is important that adults know the curriculum well, and what individual children need to know next, to decide on the best way to teach specific knowledge. In the early years, explicit teaching is usually for very short periods of time. It is likely to be followed by other forms of teaching, for example guided play.[footnote 96]

There was a clear consensus among delegates in the roundtable discussion that play is a crucial aspect of early years provision. However, what was less clear was how individual delegates defined play. This was not explicitly discussed during the roundtable, although different delegates did seem to be referring to slightly different concepts when talking about play. For example, some mainly discussed play in the context of unstructured and unguided play. Others recognised varying levels of adult involvement.

During the discussion, delegates highlighted the role of play in learning. For example, play provides a good opportunity to reinforce previously taught knowledge through practice. Delegates also discussed the role of play in children’s development. They suggested that play is crucial in developing communication and language, and social and emotional skills. The foundational nature of play and its essential role in learning was highlighted by one delegate from Scotland:

Learning is an important outcome of play and play must be the priority. It’s children’s business, from tiny. If we foster play supported by companionable adults and peers, then we have a foundation for everything that follows.

(Aline-Wendy Dunlop, academic from Scotland)

Many delegates in the roundtable discussion also felt that play has intrinsic value, regardless of its benefits to learning. For example, delegates discussed the benefits of play for children’s well-being. The OECD suggests that children who have more opportunities for play are happier. They suggest that this is because children develop skills when they play. These include listening to others, expressing feelings and preferences, sharing, and solving problems.[footnote 97] Delegates also highlighted the value in children simply enjoying play, and that itself being important. This idea is expressed in the framework for kindergarten in Norway. It states that play should be the focus in kindergarten, and that the inherent value of play must be acknowledged.[footnote 98] One delegate explained:

Play is not just a function so that children then learn better. Play is an intrinsic value of what we do and what children do and how they explore the world.

(Ingela Naumann, academic from Switzerland)

Delegates in the roundtable discussion also highlighted changes to the priority given to play in early years provision. A delegate explained that in France there are proposals to give French children a ‘real school’ from the age of 3, rather than provision focused mainly on play. Other delegates felt there are too few opportunities for free play in their countries, or that opportunities for free play are decreasing. A delegate from Norway described an ongoing debate around free play in Norwegian early years provision. The delegate expressed a desire for more free play, because of its positive effects on children’s development:

[There is] too little free play in Norwegian early childhood centres and this leads to consequences for children later on in their life. We strongly advocate free play. Of course, because play has a value in itself, it is important for a good childhood, but also in the context of children [becoming future adults].

(Elin Birgitte Ljunggren, academic from Norway)

Inspection and regulation

Summary

In many countries, early years inspections are not routine, regular or education-focused, particularly of settings for younger children. When they do occur, they often focus on structural factors, such as staff qualifications and ratios, rather than on quality of education, such as implementation of the curriculum. In some countries, guidance for inspectors is not clear. This makes it difficult to make sound judgements and maintain quality. In some countries, quality requirements and/or standards are lower for some types of provision, for example home-based provision. In England, all types of provision are subject to the same high expectations. Inspection and regulation are important for keeping children safe and ensuring that provision is of the high quality that will give children the best start in life. Ofsted inspects all setting types across the early years phase, following the same inspection framework. Inspections focus on education, including how well settings support learning and child development. Ofsted also carries out regulatory work in response to concerns, to help keep children safe.

Purpose of inspection and regulation

In England, Ofsted is responsible for inspecting and regulating all registered early years settings. Ofsted inspections in the early years evaluate the overall quality and standards of provision, including ensuring that safeguarding arrangements are effective. Ofsted’s regulatory work ensures that those registered are suitable to provide care and education for children. This includes registering providers and responding to and acting on concerns about the welfare of children.

During the roundtable discussion, delegates agreed that early years inspections are important for ensuring quality because they identify strengths, weaknesses and areas for development. In England, Ofsted inspections have an important role in supporting settings to improve their provision. During inspections, there is a discussion about what the setting could do to improve. This forms part of the published report. Following a previous judgement of inadequate, more than half of providers improve to good or outstanding at their next inspection.[footnote 99]

In Norway, inspectors play an important role in providing guidance to settings. This was explained by a delegate from Norway in our roundtable discussion:

In Norway the inspectors have a two-fold mandate – they inspect but also guide. So, you have a competence development part of being an inspector… it’s not just inspection, it’s guidance as well and this relates to all [early years] settings in Norway.

(Elin Birgitte Ljunggren, academic from Norway)

In England, the experiences of children in provision are at the heart of inspection. Ofsted’s focus is on improving experiences and outcomes for children, allowing all to reach their full potential.[footnote 100] Delegates in the roundtable discussion agreed that the main purpose of monitoring quality should be to benefit children. A delegate from Ireland highlighted that children should be the focus of inspections:

We’re thinking about how evaluation monitoring can actually benefit children themselves rather than benefiting the external stakeholders who usually look to inspectorates for accountability.

(Maresa Duignan, inspectorate representative from Ireland)

Delegates also discussed how monitoring work has an important role in keeping children safe. In England, Ofsted’s regulatory activity plays an important role in safeguarding children.[footnote 101] When Ofsted receives concerns about a setting, regulatory professionals decide whether to wait for the next inspection or to make a regulatory telephone call, visit the setting or carry out an inspection.[footnote 102] A delegate from Belgium explained that Belgium is working to increase the frequency of inspections in response to emerging problems around safeguarding:

Currently [there is] a big issue in Belgium because a number of incidents of mistreatment of young children have led to closure of facilities… extra inspectors are being recruited for the frequency of inspections to be raised.

(Els Heirweg, inspectorate representative from Belgium)

In many countries (for example, in Belgium and the Netherlands), evaluations of individual settings are used not only to improve those settings, but also to evaluate the overall early years system. For example, evaluations of individual settings may be collated to report overall findings at local, regional or national level. These reports usually give an overview of the strengths and weaknesses of the early years system.[footnote 103] In England, Ofsted uses inspection evidence to provide further insights, for example into specific areas of interest. This includes regularly publishing data and research reports. We also publish a broader ‘state of the nation’ annual report that includes a section on the early years.[footnote 104]

Quality

The overall quality of early years provision is affected by many factors. In the literature, these are usually grouped into 2 broad categories: structural quality and process quality. Delegates in the roundtable discussion referred to quality in terms of these 2 categories.

- Structural quality refers to organisational and physical features, such as health and safety, staff qualifications and staff-to-child ratios.

- Process quality refers to how well the setting supports learning and child development. This includes considering how the curriculum is implemented, the quality and variety of activities, and the quality of interactions and relationships between staff and children.[footnote 105]

It is important to consider both structural and process quality to ensure that early years provision is of high quality.[footnote 106] However, monitoring process quality is not very common in OECD countries.[footnote 107] England is one of the countries that monitors this, for example by observing staff practices, in the early years.[footnote 108]

To assess quality effectively, it is important that quality requirements and guidance are clear. In the roundtable discussion, some delegates expressed concerns that weak requirements and guidance have consequences for effective inspection. A delegate from Sweden explained that if requirements are unclear, it is harder to identify problems with provision:

The Swedish Education Act has few quality requirements for pre-schools that are measurable and can be inspected. Since we do not have achievement goals for the children in pre-school, there are also few variables that can indicate that a pre-school has problems with its education and teaching.

(Maria Klasson, inspectorate representative from Sweden)

Delegates also said that for some provider types, quality requirements are less clear or quality standards are lower. This contrasts with the approach taken in England, where all types of early years provision are subject to the same high expectations. For example, a delegate from the Netherlands said that while home-based provision broadly has to meet the same requirements as other types, differences in the way it is inspected may result in poor-quality provision:

Although the same basic curriculum and pedagogy requirements apply to… childminders, the inspection regime is more lenient than for centre-based care. Therefore, [there is] more variation in quality and especially outliers to very low quality.

(Paul Leseman, academic from the Netherlands)

Inspections

Inspections are assessments of early years settings carried out by individuals or teams who are not directly involved in the setting being evaluated. Inspectors report to local, regional or national authorities. They usually report on quality and suggest ways to improve practice. As in England, some countries (for example, Spain and the Netherlands) consider both structural and process quality when evaluating centre-based settings across the early years phase. In many countries, only structural quality is assessed in settings for children under age 3 (for example, Portugal and France).[footnote 109] In our roundtable discussion, a delegate from Germany discussed different approaches to inspection within the country. He explained that across much of Germany, there is consistent evaluation of structural quality but not process quality:

With our 16 jurisdictions and their responsibility of the educational sectors, we have more or less 16 different approaches. However, there are no nationwide, standardised, systematic and compulsory inspections of [early years] settings across Germany when it comes to process quality. This applies only to Berlin and Hamburg where an institute takes the role of an inspectorate. There are, however, inspections and surveys about health, safety and infrastructure or financial aspects, and early years providers may have their own evaluations on process quality in place.

(Daniel Turani, academic from Germany)

Whether inspections focus on structural and/or process quality is linked to the body responsible for inspections. For example, when an education inspectorate or ministry carries out inspection, the focus is usually on process quality. When non-education inspectorates or ministries carry out evaluation, there is usually a focus on structural quality. Such bodies may include ministries for family, childhood or social affairs (Ireland, Czechia, Portugal); inspection services for the care sector (Wales); or local child protection services (France). In around half of European countries, different government bodies are responsible for early years settings for children of different ages. For example, education ministries may be responsible for children over 3, and ministries for children and families responsible for children under 3. This may be why there is less focus on structural quality for children under 3.[footnote 110] In some countries, different bodies are responsible for inspecting different aspects of early years provision. This was highlighted by one delegate from Ireland:

[In Ireland] we have the Child and Family Agency who… are the statutory regulator and they inspect those more structural quality items… whereas we [the Department of Education] focus very much on process quality.

(Maresa Duignan, inspectorate representative from Ireland)

In some countries (for example, Nordic countries, Germany and Lithuania), the body operating the setting is responsible for monitoring the quality of provision. These may be local authorities or other private bodies. These providers are usually responsible for setting up their own processes. For example, in Lithuania, each municipality develops its own regulations and procedures for evaluation. While the main responsibility for ensuring quality lies at the local level in these countries, top-level authorities become involved in some situations, for example following complaints or safeguarding concerns. In Sweden, parents report concerns to the Swedish Schools Inspectorate. It is the responsibility of the Swedish inspectorate to investigate and decide what a setting should do to improve.[footnote 111]

In the roundtable discussion, delegates explained that in some countries, different types of settings are inspected in different ways and by different departments. For example, a delegate from Scotland explained that home-based provision is the responsibility of the care inspectorate rather than the education inspectorate, although a consultation in 2022 did seek views on a shared inspection framework for all early years provision. In other countries, home-based provision is inspected in the same way as centre-based provision, using the same framework, as it is in England:

In Norway you have to be approved to be able to open a [home-based setting]… Inspectors also inspect those settings, and they have to follow the framework and the curriculum in the same way as other [early years] settings. So, they have the same framework plan they follow, and they have the same regulations and the same inspectors coming to them.