18th public meeting: Held online, 6 July 2023

Updated 3 November 2023

The Industrial Injuries Advisory Council Proceedings of the 18th public meeting Held on 6 July 2023 Cardiff and online.

Foreword

The eighteenth public meeting of the Industrial Injuries Advisory Council (IIAC) was held on 6 July 2023 in Cardiff. This meeting was the first hybrid IIAC public meeting with a mixture of people attending in person and others simultaneously joining online. IIAC speakers were able to respond to questions from the floor in Cardiff and to those from the online chat, together with questions sent in before the meeting. There have been a few changes in the composition of the Council since the previous public meeting in 2021, due to some members reaching the end of their terms of office. Recently 4 new members have joined the Council, 1 employee member, 1 employer member and 2 independent members, the latter with expertise in epidemiology, occupational health and mental health.

The Council have evaluated several major issues over the last two years and these have resulted in 3 Command papers making recommendations for prescription. These have addressed major adverse health effects of COVID-19 in Health and Social Care Workers, and substantial revaluation and amendment of the prescriptions for Pneumoconiosis and Hand Arm Vibration Syndrome. There were presentations at the public meeting on these topics, together with summaries of on-going work on review of selected respiratory diseases and on neurodegenerative disease in sports people. The discussions at the meeting also raised other important issues and provided helpful and interesting views on the topics presented. The Council and the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) will consider these going forward. I would like to thank everyone who attended the meeting for contributing to a useful and productive occasion.

Dr Lesley Rushton

IIAC Chair

IIAC is a non-departmental public body which advises the Secretary of State for the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) and the Department for Social Development (DSD) in Northern Ireland, on the Industrial Injuries Scheme. The DWP and DSD are responsible for the policy and administration of the Scheme. IIAC is independent of the DWP and the DSD. It is supported by a secretariat provided by the DWP and endeavours to work co-operatively with Departmental officials in providing its advice.

This document is a record of the online public meeting and covers events and discussions on 6 July 2023. However, this report should not be taken as guidance on current legislation, nor current policy within the DWP nor DSD, as members may have expressed personal views, which have been recorded here for information.

Agenda

10:00 – 10:45: Welcome remarks Chair of IIAC – Dr Lesley Rushton

How IIAC provides evidence on health risks associated with occupational exposures for the purposes of prescription for Industrial Injuries Disablement Benefit and A brief overview of IIAC’s work in the past year – with Q&A – Chair of IIAC – Dr Lesley Rushton

10:45 – 11:30: Vibration related disorders within the scheme – with Q&A – Dr Ian Lawson

11:30 – 11:45: Tea / coffee break

11:45 – 12:30: Review of respiratory disease – with Q&A and Neurodegenerative diseases in professional sports people – with Q&A – Prof Damien McElvenny

12:30 – 13:30: Lunch

13:30 – 14:15: IIAC’s proposed revision of PD D1 – Pneumoconiosis / silicosis – with Q&A – Dr Chris Stenton and Dr Gareth Walters

14:15 – 15:00: COVID-19 and occupational exposures – with Q&A – Dr Jennie Hoyle and Dr Lesley Rushton

15:00 – 15:30: Open Forum and closing remarks – Dan Shears

15:30: – End of public meeting

Welcoming Remarks

Dr Lesley Rushton

Chair of IIAC

1. Dr Rushton welcomed everyone to the public meeting, both online and in person, and gave an overview of the forthcoming talks. Attendees online were asked to remain on mute and to ensure their video was turned off.

2. The Chair then gave an opening presentation which covered the industrial injuries scheme and IIAC’s methods for assessing related health risks. It also included an overview and summary of recent work carried out by the Council.

3. The Industrial Injuries Scheme provides non-contributory, no-fault compensation, which principally includes Industrial Injuries Disablement Benefit (IIDB). This is paid to people who become ill as a consequence of a workplace accident or an occupational accident or one of 70 + prescribed diseases known to be a risk from certain jobs.

4. The Scheme compensates employed earners; the self-employed are ineligible to claim IIDB for work-related ill-health or injury.

5. Certain prescribed diseases are given the benefit of ‘presumption’ – if a claimant is diagnosed with a disease and had an appropriate exposure then it is presumed that their occupation has caused the disease. This spares claimants the burden of gathering detailed evidence to demonstrate causation.

6. The Scheme compensates for “loss of faculty” (mental or physical) and its resultant “disablement”. Disablement is decided by comparison to the condition of an age- and gender-matched healthy person and assessed by healthcare advisers engaged by the Department. Assessments of disablement are based on loss of function, rather than loss of earnings and are expressed as a percentage.

7. Thresholds for payment are applied such that, in general, payments can be made if disablement is equal to, or greater than, 14%. Assessments of disablement can be aggregated (this is the process whereby two or more concurrent assessments are added together to produce one award of benefit).

8. Claimants can receive benefit from 90 days after the accident or onset of the prescribed disease; shorter periods of disablement are not compensated. IIDB can be paid 15 weeks following an industrial accident and prescribed diseases cannot be paid more than 3 months before date of claim.

9. IIAC is supported by a small secretariat which is provided by DWP.

10. IIAC is a statutory body, established under the National Insurance (Industrial Injuries) Act 1946, to provide independent scientific advice to the Secretary of State for the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) and the Department for Social Development (DSD) in Northern Ireland on matters relating to the IIDB Scheme or its administration. IIAC is a non-departmental government body and is independent of DWP.

11. The members of IIAC are appointed by the Secretary of State after an open competition and consist of a Chair, scientific and legal experts and an equal number of representatives of employers and employees. There are four meetings of the full Council per year and its sub-group, the research working group (RWG) also meets 4 times per year, which provides a steer to the main council on scientific matters.

IIAC current members

Lesley Rushton: Chair

Chris Stenton: Chair, Research Working Group

Raymond Agius: Member

Kim Burton: Member

John Cherrie: Member

Lesley Francois: Member

Max Henderson: Member

Jennifer Hoyle: Member

Damien McElvenny: Member

Sharon Stevelink: Member

Gareth Walters: Member

Sally Hemming: Employer representative

Ian Lawson: Employer representative

Steve Mitchell: Employed earner representative

Dan Shears: Employed earner representative

Members who have left

Keith Corkan (member)

Andrew White (employer representative)

Karen Mitchell (employed earner representative)

Doug Russell (employed earner representative)

What does IIAC do?

12. The majority of IIAC’s time is spent providing advice to the Secretary of State on the prescription of occupational diseases. IIAC’s other roles are to advise on proposals to amend regulations under the Scheme, to advise on matters referred to it by the Secretary of State, guidance for medical assessors and to advise on general questions relating to the IIDB Scheme. The Council has no involvement in the decision-making of individual claims.

13. IIAC investigates diseases following referrals from the Secretary of State, correspondence from MPs, medical specialists, trade unions, and others, including topics brought to its attention by its own members and by other stakeholders. The Council also has an on-going surveillance of new literature, reports, work of other committees, IARC, court cases etc. Public meetings are an important forum to draw attention to topics for the Council to investigate. The Chair commented that evaluation of the adverse health effects of COVID-19 on workers during an on-going pandemic was a situation that the Council had not faced before.

14. Industrial diseases (prescribed diseases (PD)) are grouped according to their cause, namely the name of the disease or the type of exposure/typical jobs:

| Classification | Type | No. diseases |

|---|---|---|

| A | Physical cause | 15 |

| B | Biological cause | 15 |

| C | Chemical cause | 34 |

| D | Any other cause | 13 |

15. IIAC uses a number of criteria in assessing the evidence needed to prescribe a disease, including:

- Scientific evidence

- Consistent independent good quality epidemiological evidence that the risk in workers in a certain occupation is much greater than risk to the general population

- A clearly defined substance of concern, exposure and/or job/occupation

- If available, evidence of a dose-response relationship between the exposure or occupation and increased disease risk

- A clear definition of both the disease of concern and how to diagnose it

- Practical considerations that the prescription:

- Can be administered effectively by decision makers without epidemiological experience

- Both disease and exposures are verifiable within scheme

- The disease is a cause of genuine impairment/disablement; for COVID, recommendations for prescription were made for health and social care workers (H&SCWs) as a whole with the caveat of being in close contact with patients.

16. The scientific evidence, which the Council requires, is obtained by:

a. Literature searches carried out by the IIAC scientific officer

b. Literature review by IIAC scientific secretariat/IIAC members

c. Oral and written evidence from:

i. Invited experts

ii. Action groups

iii. Members of the public

iv. Industry

v. Unions.

17. Deciding which diseases to recommend for prescription depends upon the complexity of the topic. “Straightforward” diseases include those that only occur due to particular work or are almost always associated or linked with work, for example pneumoconiosis or mesothelioma/asbestos. Some may be supported by specific medical tests showing a link with work (occupational asthma/dermatitis) or easily linked to work exposure (certain infections/chemical poisonings), with COVID being an example, although it may not always certain where the exposure occurred.

18. Less “clear-cut” diseases require more extensive scrutiny. These could be common in the wider public due to non-work-related causes (e.g., smoking in respiratory diseases) and in individual cases there may have no reliable way to test if it is occupational or not. IIAC looks for evidence that the disease can be attributed to occupational exposure with reasonable certainty; for this purpose, ‘reasonable certainty ’is interpreted as being based on the balance of probabilities i.e., that the risk of the disease in a particular job or exposure to a hazard is more likely than not due to the occupation.

19. Where there are good quality epidemiological studies, the Council looks for evidence that the risk of the disease in a particular job or exposure to a hazard is more than double the risk than those not exposed. However, if there are limited epidemiological studies of long-term disabling disease with good quality occupational information, IIAC collects and collates all available qualitative and quantitative evidence on exposure, risks and disease outcomes and evaluates the strength and consistency of the information in making a judgement regarding ‘more likely than not’.

20. Openness and transparency are essential criteria of IIAC, and the Council ensures it meets these criteria through stakeholder engagement and through a range of publications including:

a. Command papers – laid before Parliament and placed in the libraries of the House of Commons & the Lords.

b. Position papers – deposited in the libraries of the House of Commons & the Lords.

c. Information notes.

d. Also, annual reports, proceedings from public meetings and the minutes from full Council and RWG meetings.

e. The Council can also commission reviews which are also published.

21. After IIAC has completed an investigation and made recommendations for prescription, it is then out of the Council’s hands. DWP officials will:

a. Prepare submissions to Ministers

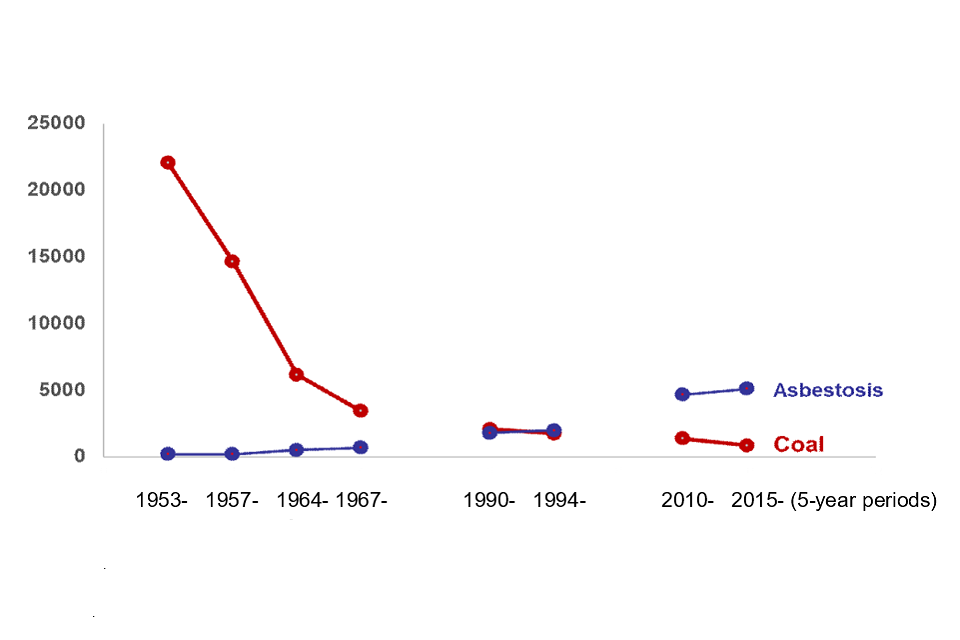

b. Consideration of legal implications and the impact of the recommendations:

i. Numbers of claims

ii. Costs of awards and operational costs

iii. Deliverability implications.

22. If Ministerial approval is granted:

a. Drafting of legislation takes place – scrutinised by the Council

b. Laid before Parliament

c. Guidance for DWP staff and decision makers written or updated

d. Communication with stakeholders.

23. The Chair reiterated that IIAC provides independent advice to Ministers and will help DWP officials, where required, for example, with the impacting process. However, IIAC is not a lobby group – it will have discussions with Ministers if further explanation is required. This has happened for Dupuytren’s and more recently COVID-19.

24. The current and recent work programme for the period 2021-23 includes:

a. Command Papers:

i. COVID-19 and occupational impacts (published)

ii. Hand-arm vibration and assessment of exposure (published)

iii. Review and update of the prescription for PD D1, pneumoconiosis (almost complete)

b. Position Papers:

i. Limitations of epidemiology when investigating occupations with a potential for significant vibration exposure and PD A11, hand-arm vibration syndrome (HAVS) (published).

c. Information notes:

i. Dupuytren’s contracture – clarification and amendment of the prescription (published).

d. Other issues discussed by the Council included:

i. Firefighters and cancer

ii. Neurosensory testing regime HAVS

iii. Audiometric testing for noise-induced hearing loss (Northern Ireland).

25. IIAC Future Work Programme:

a. COVID-19: Continue monitoring of evidence particularly for occupations such as transport and education and evaluation of ‘Long-Covid’, although data linking long-covid to occupation is difficult to find.

b. Commissioned Review: comprehensive review and evaluation of the literature on selected work-related malignant and non-malignant respiratory diseases (including lung cancer and COPD) to inform update and potential expansion of the IIDB scheme.

c. Neurodegenerative disease in footballers and in other contact sports.

d. Occupational disease in women:

i. Ovarian cancer and asbestos

ii. Overview of non-malignant disease

Other issues:

e. Update of the B diseases, particularly viruses

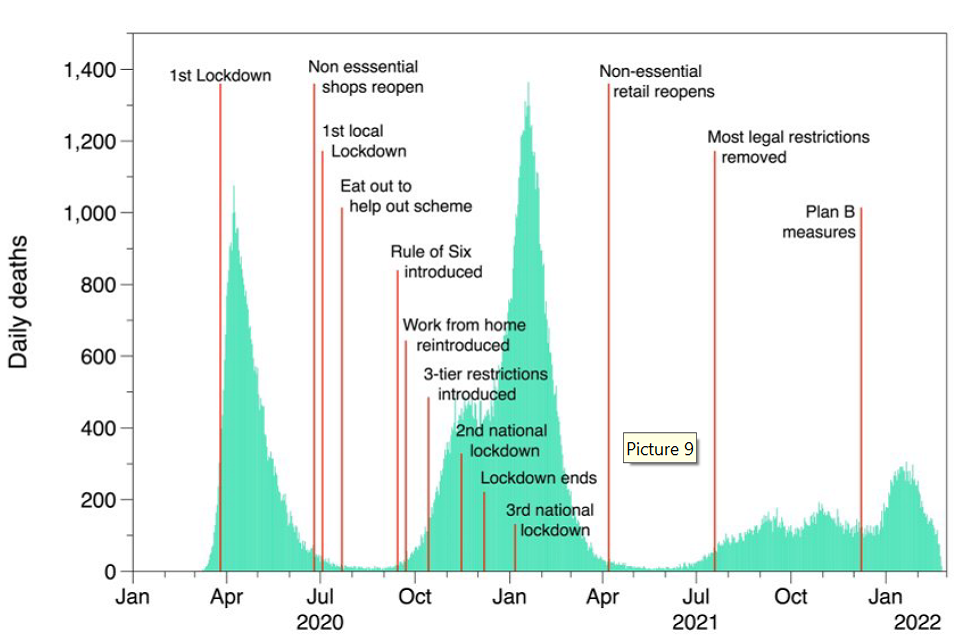

f. Welding fumes, including lung and ocular cancers.

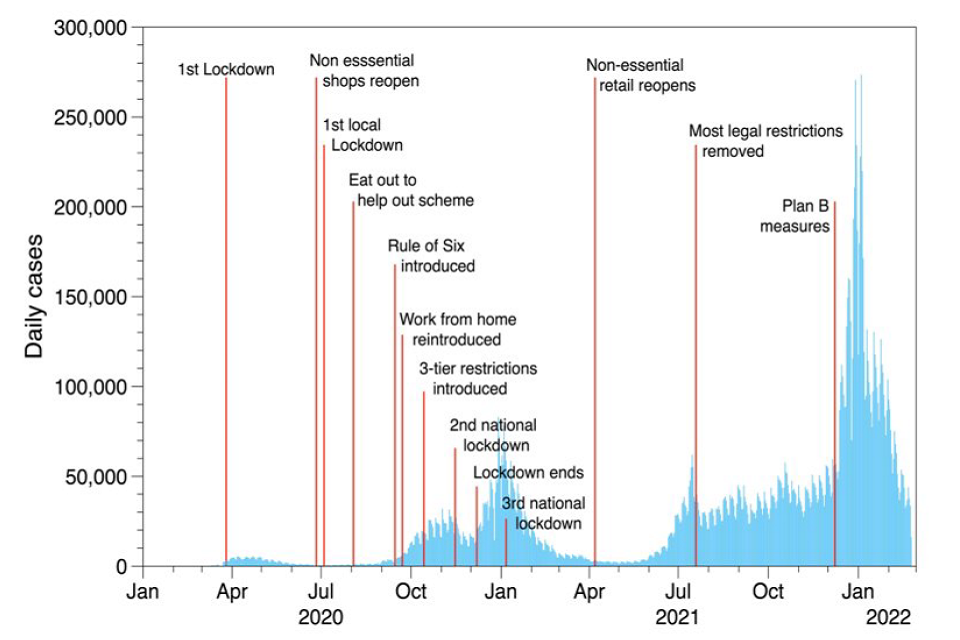

Comments, questions and answers from the ‘Welcoming Remarks ’and ‘How IIAC evaluates evidence on health risks associated with occupational exposure ’sessions.

26. A representative from the Fire Brigades Union (FBU) commented that since the Council published its last review on cancers in firefighters, other papers have been published, particularly by Professor Stec (UCLan). These new data have indicated firefighters have a greatly increased risk of dying from cancers. Other factors such as stroke or heart attacks were also elevated due to toxic contaminants. The FBU asked about IIAC’s review process and whether these new data would trigger a new review, given its workload, and would this be prioritised.

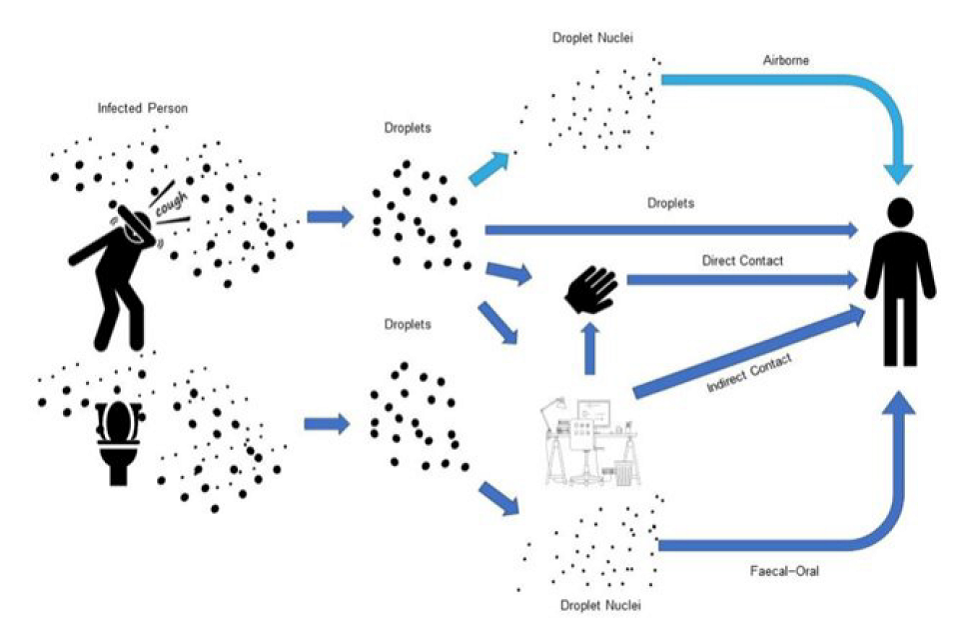

27. The Chair indicated they would be willing to discuss the implications of the recent publications in more detail with the FBU on a personal basis. The Chair then outlined the reasons why the more recent investigation into cancers in firefighters was initiated, which resulted in a position paper (published 2021) as a response to recommendations made by the Environmental Audit Committee’s (EAC) report. The EAC report featured evidence from the Grenfell Tower fire relating to the exposure of firefighters to toxic chemicals. The Council did not find risks estimates which were doubled, but acknowledged there were associations between certain cancers and firefighting.

28. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) published a monograph which classified firefighting as a hazard and stated this occupation is a group 1 (definite human hazard) for mesothelioma and bladder cancer. Mesothelioma is already covered by IIDB.

29. The Chair addressed the recent publications from UCLan on Scottish firefighters which showed very high-risk estimates for a wide range of diseases, in contrast to the estimates shown in other literature including that reviewed by IARC. The methodology used compared the observed numbers of firefighter deaths with what might be expected in the general population. This type of comparison would generally yield a ‘healthy-worker’ effect, i.e., overall and for many non-malignant diseases the death rates in a worker population will be lower than that of the general population as the latter includes those who are unable to work through ill-health.

30. As the methodology was not clear in the UCLan papers, IIAC wrote to the author asking for clarification and received a helpful response. However, this led to further questions which were put to the author, but the Council has yet to receive a response to this second set of queries. The Chair commented that if there were no methodological issues with the UCLan papers, this evidence would be examined alongside other evidence and it may not make a difference to the Council’s conclusions as it is one study which is relatively small compared to other studies. The Council will continue to monitor the situation and will report in due course.

31. A representative of the British Dietetic Association (BDA) commented that they felt it was right to recognise health workers in the recent IIAC recommendations for prescription for the impact of COVID-19, but long-covid was now prevalent as well as symptoms such as anxiety/distress. They asked what provision the Council is making for mental health issues.

32. The Chair replied that when IIDB claimants are medically assessed for disability, consideration is taken of both their mental health and their physical health. The Chair also asked an IIAC member with experience of long-covid clinics to contribute. This member commented that long-covid was a complex issue and some aspects would be covered by a later presentation. The difficulty has been ascribing this condition to occupation in a pandemic alongside the complexity of accurately diagnosing the condition, which has resulted in a set of varied symptoms. There are studies going on which are expected to report soon.

Presentations

Vibration Related Disorders

Dr Ian Lawson

35. This presentation was comprised of two elements:

a. Hand-arm vibration syndrome and assessment of exposure, PD A11, with the focus being on exposure assessment.

b. Dupuytren’s contracture due to hand-transmitted vibration, PD A15

Prescribed disease A11

36. The speaker gave an overview of vibration related disorders, which occur in people who use vibrating tools:

a. PD A11, Hand Arm Vibration Syndrome, (HAVS) being the most commonly known

i. Vascular: Vibration white finger (VWF) a form of Raynaud’s phenomenon (A11a 1985).

ii. Sensory: tingling, numbness, reduced sensory perception and dexterity (A11b 2007)

b. PD A12, Carpal Tunnel Syndrome, CTS (1993)

c. PD A15, Dupuytren’s Contracture, DC (2018)

NB: Musculoskeletal disorders including osteoarticular (arthritis, bone cysts) and Hypothenar Hammer Syndrome.

d. Prevalence of vibration related PDs can be viewed at the following: https://www.hse.gov.uk/statistics/causdis/vibration/index.htm

37. Although the main focus of the talk was exposure assessment, the speaker gave an overview of the current PD A11 prescription which is comprised of type of job and the tools used. The jobs indicated below have been in place since 1981:

a. the use of hand-held chain saws on wood; or

b. the use of hand-held rotary tools in grinding or in the sanding or polishing of metal, or the holding of material being ground, or metal being sanded or polished, by rotary tools; or

c. the use of hand-held percussive metalworking tools, or the holding of metal being worked upon by percussive tools, in riveting, caulking, chipping, hammering, fettling or swaging; or

d. the use of hand-held powered percussive drills or hand-held powered percussive hammers in mining, quarrying, demolition, or on roads or footpaths, including road construction; or

e. the holding of material being worked upon by pounding machines in shoe manufacture.

The above criteria were derived from expert evidence rather than epidemiological data.

38. The Council receives requests to review prescriptions and in this instance a correspondent indicated gardeners using strimmers should be covered by PD A11, prompting this review. Case studies were examined, but there was insufficient epidemiological data to meet the doubling of risk criterion. When the guidance from the HSE was reviewed, there were differences between the list of tools on the prescription and those listed in HSE guidance – for instance powered mowers and strimmers were listed by the HSE, but not under PD A11.

39. The PD A11 prescription has been reviewed in the past:

a. 1995 where recommendations were made to expand the list of tools (not implemented)

b. 2004 recommended for tools… ‘Ideally, coverage would be broader….. Estimated as a dose…[but] appears to be too difficult in practice’….

40. In this current review, two approaches were taken:

a. review of the assessment of vibration magnitudes, exposure response relationships and risk prediction modelling based on International Standard, ISO 5349-1.

b. A consultation exercise with external experts on the feasibility of extending the list based on their knowledge and experience of vibrating tools[footnote 1] and the potential to develop HAVS e.g., vibration magnitudes equivalent to those on the list. An issue with HAVS is that often a claimant will hold a workpiece against a vibrating surface.

41. Assessment of vibration dose requires knowledge of three variables: the vibration magnitude, the daily usage, and the years of exposure to vibrating tools. A model including these three variables can be used to estimate a dose-response relationship with the percentage of people experiencing onset of white finger or finger blanching as the response measure. The non-occupational rate of finger blanching is approximately 5% in the male population. The model can thus be used to indicate the different values of the vibration magnitudes, daily usage and years of exposure that would give a rate of finger blanching that is 10% or more, i.e., doubled the risk.

42. The International Standard ISO 5349-1 covering these three variables was used to prepare a standalone procedure which was shared with internal stakeholders and external experts and feedback sought. A number of issues were identified:

a. The ISO 5349-1 model is based on the studies of groups, not individuals

b. The ISO 5349-1 model overestimates risk for low frequency tools (e.g., road breakers) and underestimates risk for intermediate or higher frequency tools (e.g., using grinders and drills)

c. Other literature is not supportive of this model (HSL:RR1060,2015)

d. Factors other than the vibration magnitude affect symptom onset e.g., individual susceptibility, ergonomic risks, tool maintenance, workpiece hardness.

e. There would be practical issues for both claimants and assessors e.g., additional information gathering, reliable information on tool magnitudes, individual exposure recall.

Consequently, this approach was deemed unsuitable for recommendation.

43. The second approach was to consult with external experts:

a. A consultation exercise was carried out with external experts on extending the list of tools based on their knowledge and experience of vibrating tools and the potential to develop HAVS. This is included in the recently published command paper (CP 868) with recommendations for revision of Schedule 1 of the current prescription

b. ‘Tools and processes which are associated with significant exposure to hand transmitted vibration including any hand-held, hand-guided or hand-fed, powered machine (e.g., pneumatic, hydraulic, electric (wired or battery) or internal combustion engine) that:

i. is fitted with an abrasive or polishing attachment…. (e.g., grinders, sanders) or finishing (e.g., polishers including floor polishers); or,

ii. is fitted with an attachment such as a cord (e.g., strimmer), blade (e.g., jigsaw, cut-off saw, hedge trimmer, brush cutter, etc.) or cutting bit (e.g., woodworking machine or router) …; or,

iii. is fitted with an attachment such as a drill bit (e.g., rotary hammer) vibrating needles (e.g., needle scaler), scabbling head (e.g., scabbler), tines or spikes (e.g. aerator, scarifier), chisel, pick, spade (e.g., breaker, demolition hammer)….; or,

iv. is fitted with a rotating socket, driver bit or other attachment for the purpose of fastening or unfastening… (e.g., wrench, ratchet, nut runner, impact driver, rivet gun, etc.); or,

v. is fitted with a ram, plate or roller for smoothing or compaction of material (e.g., plate compactor, trench rammer, sand rammer, concrete screeding machine); or,

vi. which propels or expels a fluid (air or water) for the purposes of cleaning or moving dust, dirt and debris (e.g., leaf blower, water jetting lance); or,

vii. which has a vibratory action for the removal of air from concrete (e.g., concrete poker).

Note. An operator may also be at risk of developing HAVS if they grip a workpiece, tool or component as it is worked on or impacted by a machine (e.g., pedestal grinder, polishing machine, drop forge, spring hammer, bucking bar, shoe pounding machine).

44. The speaker summarised the presentation on HAVS and exposure assessment:

a. This is a fairer approach to suspected cases of HAVS which are not supported by epidemiological evidence.

b. Medical assessors will continue to determine whether vibration has been of sufficient intensity and duration when assessing PD A11 claims.

c. The Presumption rule is retained for the existing/current list of tools.

d. Command paper CP 686 is supported by position paper 49 on ‘Limitations of epidemiology when investigating occupations with a potential for significant vibration exposure and PD A11, Hand-Arm Vibration Syndrome’

e. Included in position paper 49 is supportive evidence of more than a doubling of relative risk for the current list of occupations and limitations in other occupations (e.g. gardeners, orthopaedic surgeons and dentists[footnote 2]).

Comments, questions and answers from the vibration related disorders presentation:

45. No questions from the audience.

Dupuytren’s contracture, PD A15 – with Q&A

46. Dr Lawson introduced the topic by giving an overview of the recommended prescription for Dupuytren’s contracture (DC) which was published in command paper CM 8860 in 2014. The regulations for PD A15 came into force in December 2019 and are shown below with changes to the original prescription shown in red.

| Disease | Occupation |

|---|---|

| Dupuytren’s contracture resulting in [red text: fixed flexion deformity of one or more digits] | Any occupation involving the use of hand-held powered tools whose internal parts vibrate so as to transmit that vibration to the hand, but excluding those tools which are solely powered by hand, where the use of those tools amounts to a period or periods in aggregate of at least [red text: 10 years] and where, within that period or those periods, the use of those tools amounts to at least [red text: 2 hours per day for 3 or more days per week] and where the onset of the disease fell within the period or periods of use specified in this paragraph. |

47. An overview of the condition was given, which noted that there can be some confusion between Dupuytren’s disease (DD) and DC. DD is fibroproliferative connective tissue disorder:

a. In the hand it affects the palmo-digital fascia (aponeurosis) – soft tissues in the palm side of the hand

b. Manifests as nodules and cords in the palm or fingers which can progress to contracture (DC) of the fingers.

48. The condition is diagnosed from typical characteristics but can be confused with trigger finger, ganglions or cysts. There are a number of risk factors for DD including family history, age, diabetes, alcohol, and smoking. A systematic review reported DD is commoner in men, rising with age: median prevalence 12% at 55 yrs, 21% at 65yrs and 29% at 75yrs. Tests for staging of the condition include the Heuston table top test and Tubiana scale.

49. Presumption was discussed and the history of how the regulations were drafted following a request from DWP policy officials to explain what was meant by ‘fixed flexion contracture of digits and the resulting prescription differing from that originally proposed in the 2014 command paper.

a. A significant number of DC cases only affect the metacarpophalangeal joints (MCP)

b. A minority of nodules can progress to contracture

c. These corrections were addressed by issuing information notes with guidance for medical assessors and claimants.

50. Following feedback, the PD A15 prescription was amended in March 2022 paraphrased below; Providing the occupational criteria is satisfied…

i. Fixed flexion deformity of one or more metacarpophalangeal joints (MCP) greater than 45 degrees or fixed flexion deformity of one or more interphalangeal joints (IP) that developed either:

1. during the course of the claimant’s occupation or

2. after the period of occupation where there is evidence of onset of MCP joint involvement or palmar changes (nodules or thickening) during the period of occupation.

51. Following the amendments to the prescription, DWP officials conducted an audit of claims to the prescription to check if it was working as the Council intended;

PD A15 case files audited by IIDB official

i. Just over half of claims accepted by the decision maker resulted in diagnosis of PD A15

ii. Some cases were captured by the amended prescription

iii. Disablement percentages varied but generally aligned with the flexion deformity recorded

iv. Medical practitioner’s advice on the disablement percentage is robust and correlates with the suggested disablement

v. Capturing sole IP, sole MCP and combined involvement and clinical picture tends to be more complex than involvement of a single joint.

52. The speaker concluded the presentation by discussing the Quadriga phenomenon[footnote 3] and how this relates to overall disability with DC.

Comments, questions and answers from the Vibration Related disorders and Dupuytren’s contracture session.

53. An attendee gave an example of when a claim for PD A11 was declined because of their occupation, but a similar case from a different occupation was allowed. Dr Lawson explained that if the diagnostic criteria were met, then the proposals in the command paper should address this anomaly and open the prescription to more occupations.

54. An attendee representing mineworkers asked about DC developing after employment had ceased and gave examples of where this has occurred. The onset of the condition may well have started whilst in employment, but the worker would likely not be aware of the disease and put the symptoms down to hard work. Dr Lawson responded that this could be broken down into two elements – latency of onset and progression of the disease. If symptoms of DC had started during employment, then this should be covered – medical evidence is not required. If no symptoms were observed during employment, then this would likely to not be accepted. This is because DC is not uniquely occupational and there are other risk factors (e.g., age, smoking, alcohol) which can cause it.

55. Another mineworker representative felt that some claims to PD A15 were not being assessed according to the intention of the Council as onset of the disease was disputed. Dr Lawson stated he was unable to answer that but reiterated that, should a claimant who satisfies the occupational element of the prescription report that symptoms started during employment, then this should be accepted.

56. The Chair thanked Dr Lawson for the presentations and attendees for their questions.

Review of respiratory diseases – with Q&A

Prof Damien McElvenny

57. Professor McElvenny started the session by stating that whilst he was an independent scientific member of IIAC, he is also principal epidemiologist at the Institute of Occupational Medicine (IOM), which won a competitive tender to carry out this review.

58. This review was commenced because the Council was concerned that prescriptions relating to respiratory disease (cancer and non-cancer) were out of date or were missing exposure-disease outcomes that should be prescribed.

59. Examples of currently prescribed respiratory diseases (RD) were given, but the main focus of the review was on malignant diseases and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), so asthma and other types of RD were not included in the review. Professor McElvenny gave an overview of the IOM project team, which included an external RD expert.

60. The review is focusing on respiratory cancer and COPD and the approach taken was to:

a. Carry out literature searches for review articles (WoS, Pubmed, Embase, Cochrane Reviews)

b. Use authoritative sources such as IARC, IIAC reports, charity websites, views of HSE respiratory physicians, HSE WHEC papers

c. Develop criteria for prioritizing for a more in-depth investigation (in collaboration with IIAC).

61. The screening of the literature, based on reviews, yielded the following numbers of published papers:

| Subject of paper | Number |

|---|---|

| Lung cancer | 145 |

| COPD | 51 |

| Unspecified respiratory disease | 25 |

| COPD; asthma | 17 |

| Mesothelioma | 10 |

| Unspecified respiratory cancer | 10 |

| Laryngeal cancer | 7 |

| Asthma | 5 |

| Lung cancer; mesothelioma | 5 |

| COPD; lung cancer; asthma | 4 |

| Lung cancer; laryngeal cancer | 4 |

| Sino-nasal cancer | 4 |

| Respiratory symptoms | 3 |

| Asthma; respiratory symptoms | 2 |

| COPD; asthma; unspecified respiratory disease | 2 |

| Lung cancer; asthma | 2 |

| Lung cancer; silicosis | 2 |

| Lung cancer; unspecified respiratory disease | 2 |

| Non-malaignant respiratory disease | 2 |

| Pleural cancer | 2 |

But excluded asthma.

62. In terms of occupations:

| Occupation | Numbrer |

|---|---|

| Various | 14 |

| Miners | 9 |

| Agricultural | 7 |

| Asbestos workers | 6 |

| Construction industry (work in) | 6 |

| Transport | 5 |

| Farmers | 4 |

| Healthcare workers | 4 |

| Painters | 4 |

| Aluminium production | 3 |

| Cement dust | 3 |

| Cleaners | 3 |

| Sailors | 3 |

| Welders | 3 |

| Dust | 2 |

| Industrial radiation workers | 2 |

| Inorganic dust | 2 |

| Metal smelting workers | 2 |

| Nuclear | 2 |

| Rubber industry | 2 |

| Soldiers | 2 |

63. The most common agents, which were subject to reviews, included:

a. Asbestos

b. Silica

c. Diesel exhaust

d. Pesticides

e. Radon

f. Outdoor pollution

64. A matrix of disease by occupation allowed IOM, in conjunction with IIAC to select which disease/exposure combinations to take forward.

65. The main prioritisation criteria included:

a. Estimated annual number of cases in the UK (as determined by attributable fraction studies and some evidence of a likely raised relative risk (RR) (and therefore a prospective of identifying a sub-population with RR > 2) (i.e., captures associations with large number of cases, but also rarer associations where RR quite high)

b. Reviewed by IIAC in the past, but significant recent epidemiology since last review

c. Not previously considered by IIAC, but significant recent epidemiology

d. Relevant for the UK – e.g., excluded Uranium mining as this is not done in the UK.

66. Other potential criteria included:

a. Sufficient volume of epidemiological literature

b. Reasonable possibility of being able to define at least one administratively workable exposure situation

c. Sufficient information on exposure-response – associated with doubling of RR

d. Evidence provides ability to deal with the confounding effects of tobacco smoking

e. Can document where the key exposures have taken place.

67. When the reviews were sifted and prioritisation criteria applied, the following disease/exposure combinations were suggested to take forward:

a. Silica and lung cancer

b. Silica and COPD

c. Work as a cleaner and COPD

d. Radon and lung cancer

e. Hexavalent chromium and lung cancer

f. Arsenic and lung cancer

g. Asbestos and lung cancer

h. Work as a painter and lung cancer

68. Other medium priorities were identified, but six disease/exposure combinations were selected to proceed for review:

a. Silica and lung cancer

b. Silica and COPD

c. Cleaning agents and COPD

d. Hexavalent chromium (Chromium VI) and lung cancer

e. Asbestos and lung cancer

f. Farming and COPD.

69. Although the initial literature searches focused on reviews, when the priorities had been agreed, it was necessary to go back to the primary literature to identify find the evidence which IIAC requires. The speaker gave an example of the breadth of literature found for silica and COPD. For all priorities, data needed to be extracted and tables of evidence produced.

70. When data analysis is complete, IOM plan to produce reports to include:

a. Brief summary of main findings of each study

b. Summarise by industry/occupations/agents

c. Provide a preliminary view on:

i. Change to current prescriptions

ii. New prescriptions.

71. The speaker then summarised progress to date and gave an indicative timeline with final reporting expected before Easter 2024.

72. The Chair made the point that for exercises such as this, all the papers identified have to be scrutinised and data extracted from them – e.g., for lung cancer and asbestos, over 1000 papers were identified, which is a significant amount of work. This applies to all investigations carried out by IIAC.

Comments, questions and answers from the RD Commissioned Review session.

73. An online attendee commented that there are fewer studies involving women and occupation (and are often excluded from studies), so would IIAC require the same standard of evidence for women.

74. Professor McElvenny stated that (rightly or wrongly) it was assumed that occupational risks for men were the same as for women, but epidemiologically, it is not known if that is the case. For some of the issues included in the RD review, there will be predominantly female workforces, for example cleaning products and COPD. In this instance, it would be unlikely a less stringent standard of evidence would be applied.

75. An online attendee made the point that workers in schools may be exposed to asbestos but this may not be regarded as occupationally related.

76. Professor McElvenny replied that he felt longitudinal studies into teacher mortality is an under-researched area. It was felt that it would be useful if more studies were carried out on teachers as this may present IIAC with evidence. The Chair stated that mesothelioma cases could be covered by IIDB (PD D3), but also stated this may come up as part of the RD review.

Neurodegenerative diseases (NDD) in professional sports people – with Q&A

77. Professor McElvenny started by declaring a conflict of interest that he was part of studies and was actively researching in this area:

a. Funding from Drake Foundation for BRAIN (Rugby study; Gallo et al 2022 -https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34668650

b. Funding from Drake Foundation for HEADING study https://www.lshtm.ac.uk/research/centres-projects-groups/heading-study

c. Funding from Colt Foundation for MORSE study (MORtality Study of former professional footballers in England and Wales).

78. The speaker then went on to describe IIAC’s interest in this area:

a. This is a very active area of research

b. New studies are being published at quite a rapid rate, but can be confusing

c. They cover a range of sports (and range of levels, professional/elite, varsity, school), but not all are relevant to IIAC in terms of prescription, but are indicative for the risks

d. Concerns have been expressed to IIAC by Professional Footballer’s Association, but this investigation has been widened to consider other sports.

79. IIAC reviewed this topic in 2016 and published an information note, which found:

a. Several epidemiological studies of neurodegenerative diseases (NDDs) in sportspersons have more than doubling of relative risks (RRs)

b. Evidence for Parkinson’s Disease (PD) and dementia is sparse

c. There is more evidence for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS, also known as motor neurone disease) but the evidence was not felt to be sufficiently robust.

80. An overview of ALS was then given:

a. ALS (or Lou Gehrig’s disease in the USA) is a rare neurological disease that affects motor neurons

b. For 10% of those diagnosed, it has a genetic cause

c. For remaining 90% causes are generally unknown (thought most likely to be a complex mixture of gene and environment interactions)

d. Risk increases with age up to age 75 (most common aged 60 to mid-80s)

e. Before age 65, the risk is slightly more common in men than women; the difference disappears after age 70

f. Other risk factors include:

i. Smoking, especially for (post-menopausal) women

ii. Environmental endotoxin exposure

iii. Lead?

iv. Military service (Metals? Chemicals? Traumatic injuries? Viral infections? Intense exertion?)

81. An overview of Parkinson’s disease was then presented:

a. PD is caused by a loss of nerve cells in the substantive nigra (brain)

b. Causes are generally unknown, but are probably a combination of genetic and environmental factors

c. Specific genetic changes have been identified that cause PD, but they are uncommon except in rare cases when many family members affected

d. Environmental toxins (herbicides, pesticides) may increase the risk of PD, but risk is small

e. PD usually develops at age 60 or older

f. It is more likely in men than women

g. Smoking may reduce risk.

82. Dementia was then discussed:

a. This is an umbrella term for a range of progressive conditions that affect the brain

b. Different types: Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia, fronto-temporal dementia, mixed dementia

c. Dementia tends to occur at age 65+, with the risk doubling every 5 years or so above this age

d. Certain ethnic communities (e.g., South Asian, African or African-Caribbean) are at increased risk - thought to be explained by risk factors associated with stroke, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease, as well as differences in diet, smoking, exercise and genes are thought to explain this

e. More women are affected than men (2 to 1 globally). Twice as many women over age 65 are diagnosed with Alzheimer’s whereas vascular dementia in slightly more in men that women

f. In rare cases it can be passed from one generation to another

g. Modifiable risk factors include: diabetes, high alcohol intake, high blood pressure, lack of exercise, low educational attainment, obesity, poor physical health, smoking.

83. Professor McElvenny mentioned declining cognitive function as this may be an early sign of later development of NDD:

a. Cognitive decline is a normal process of ageing

b. Some aspects e.g., vocabulary can increase with age

c. Most e.g., conceptual reasoning, memory, processing speed, decline gradually over time

d. Relatively little decline until around 50, accelerates in the late 70s

e. Some protection from “cognitive reserve” (can be traced back to intelligence in childhood)

f. Various psychometric instruments for measuring cognitive decline

g. Cognitive decline can predict future neurodegeneration.

84. The final NDD discussed was chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE):

a. This is a brain condition thought to be linked to repeated head injuries and blows to the head (sport, military combat). It slowly gets worse over time and leads to dementia

b. It has been associated with second impact syndrome in which a second injury happens before previous head injury symptoms have fully resolved

c. It cannot be definitively diagnosed during life, except (recently) for people with high-risk exposures

d. “Punch drunk” syndrome – a term coined by Martland in 1928 a term which was replaced in in 1937 by the less derisive “dementia pugilistica” is becoming associated with CTE.

85. Mild traumatic brain injury can occur following concussion. This can be severe or mild traumatic brain injury, also known as sub-concussive head impact in football.

a. Amsterdam 2022 Consensus Statement on Concussion in Sport tried to define concussion and this is important as this relates to what the Council is trying to look at:

i. “Sport-related concussion is a traumatic brain injury caused by a direct blow to the head, neck or body resulting in an impulsive force being transmitted to the brain that occurs in sports and exercise-related activities. This initiates a neurotransmitter and metabolic cascade, with possible axonal injury, blood flow change and inflammation affecting the brain. Symptoms and signs may present immediately, or evolve over minutes or hours, and commonly resolve within days, but may be prolonged.”

b. A direct or indirect blow to the head and neck can cause the brain and skull to “shake together violently” – this may be a relevant exposure, but is difficult to capture epidemiologically

c. So, if there is an association between sports-related activity, it could be due to;

i. High levels of physical activity

ii. Blows to the head (TBI)

iii. Concussions (mTBI)

iv. Blows to the body (causing brake to shake).

86. Some recent systematic reviews found in the literature were then discussed as this a useful place to start to assess the evidence IIAC requires. These reviews illustrate the variations found in the types of sports studies (athletes, professional sports people, rugby players, footballers, boxers etc.), and different measures of disease and exposures used.

87. When the Council looked at this topic (ALS) in 2016 they found that:

a. Most evidence was derived from Italian football league (studies originally in the context of a drug doping scandal)

b. It was likely (but not clear) that most cases described in the three main studies common to all reports (less independent evidence)

c. There was some support from other studies but nothing in other professional soccer players

d. The Council was unable to recommend prescription at this time (due to limitations of evidence base).

88. The speaker then went on to outline the current approach the Council is taking for this investigation:

a. There is a need to consider disabling conditions

b. They are looking for robust evidence “on balance of probabilities”

c. Decisions on where to start will be based on where evidence is perhaps strongest, ALS in professional sportspersons

d. A literature search is being undertaken

e. A table of evidence will be complied to inform the way forward

f. IIAC will also look at PD and dementia (may subdivide) and possibly CTE (if evidence permits).

Comments, questions and answers from the NDD in sportspeople session.

89. A representative of the Unite Union requested clarification on a point where trauma in the military was given as a risk factor for ALS – was this physical or mental trauma such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)? The attendee also asked what the relevance of smoking is when examining the evidence as this can be a complicating factor for IIDB claims and for GP attitudes. An example of smoking and inhaling asbestos was given where the risks of malignant disease is greatly increased.

90. Professor McElvenny commented that he thought the trauma in the military was due to explosions or being near to munitions as they are fired, but the evidence is not strong. Studies in this area may help to understand what is happening in sports. Regarding smoking, Professor McElvenny was aware that the relative risks for asbestos were more than doubled for smokers compared to non-smokers, so should not be dismissed by GPs where asbestos is involved. Smoking is a risk factor for many NDDs other than PD.

91. The Chair thanked Professor McElvenny for the presentations and drew this session to a close to break for lunch.

IIAC’s proposed revision of PD D1 – Pneumoconiosis / silicosis – with Q&A

Dr Chris Stenton and Dr Gareth Walters

92. Dr Lesley Rushton welcomed everyone back and introduced respiratory disease (RD) experts Dr Chris Stenton and Dr Gareth Walters to give an overview of the proposed changes to the PD D1 prescription.

93. Dr Stenton started by saying that this review had been ongoing for some time and external RD experts had also been consulted, but the proposals outlined in the presentation would likely be final. Dr Stenton described the proposed changes to PD D1 and Dr Walters gave some insight into new causes of pneumoconiosis.

94. Dr Stenton presented slides which illustrated how pneumoconiosis is represented on an x-ray and explained that it is diffuse lung shadowing (fibrosis) caused by mineral dusts. This distinguishes this condition from others such as asthma which may show fairly normal x-rays.

95. Pneumoconiosis is one of the most common claims to IIDB ~1200 cases per year with the majority of claims being associated with asbestos exposure:

| Substance | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Asbestos | 79% |

| Coal | 18% |

| Silica | 1% |

| Other | 2% |

However, the Surveillance of Work-related and Occupational Respiratory Disease (SWORD) database indicates much higher rates of pneumoconiosis caused by silica, causing concern that silica-related pneumoconiosis is under-represented in IIDB.

96. IIDB pneumoconiosis awards have changed over the years with those associated with coal exposure declining rapidly in the 20 years since 1950:

97. Concerns over the lack of awareness of silicosis prompted the review of PD D1 and the complexity of the prescription where there are 12 categories and 14 subcategories. This makes the prescription difficult to navigate.

98. Dr Stenton then set out the reasons and approach for the proposed changes to PD D1:

a. Simplified list of pneumoconiosis

b. Removing any restrictions about cause

c. Removing the ‘open’ category open’category

d. Changes to the rules about presumption

e. Bringing awards into line with those for other conditions

f. Changing awards for TB and COPD

99. It is proposed that the current multi-category prescription be replaced with:

a. Asbestosis

b. Coal worker’s pneumoconiosis

c. Silica-containing dusts

d. Metals.

100. In reality, the situation is more complex with silica-containing dusts covering:

i. Silicosis – exposure to fairly pure silica e.g. sandstone

ii. Mixed mineral dust fibrosis – this is very rare but can modify the impacts of silica and a different picture in the lungs can be apparent e.g., cutting concrete or other construction jobs

iii. Silicate pneumoconiosis (non-fibrous silicates talc, mica, china clay) – rare, but feasible

And metals including

iv. Aluminium

v. Beryllium – often mis-diagnosed and confused with sarcoidosis

vi. Hard metal/ tungsten carbide/ cobalt e.g. making of tools/drill bits

vii. Indium tin oxide

viii. Cerium

101. The Council also proposes to remove any restrictions about the cause – pneumoconiosis is almost exclusively occupationally related and any cause outside of work is exceptionally rare. In addition, for both silicosis and asbestos the occupations listed in the current PD D1 are mainly obsolete.

102. Dr Stenton then discussed the open category in the current PD D1, which was introduced in 1953.

Exposure to dust if the person employed in it has never at any time worked in any of the other occupations listed.

103. There have been few awards under this category and few new causes of pneumoconiosis since then. In addition, the restriction that a claimant under this category should not have worked in any of the other categories is no longer applicable as workers can change occupations regularly and so would be disadvantaged.

104. Presumption, which is a fundamental feature of the IIDB scheme, allows medical advisors to assume that a disease is due to the occupation. Presumption doesn’t work well for pneumoconiosis as this condition is almost always linked to work.

105. The current prescription for pneumoconiosis requires more than 2 years’ work in aggregate with the relevant exposure. However, there are cases where the condition can develop with less than 2 years exposure. The Council therefore propose the following that diagnosis should be established by an appropriate medical specialist.

106. Another proposed change to PD D1 covered by Dr Stenton (which was previously recommended in the IIAC command paper (cm 5443) published in 1973) was to bring the prescription into line with those for other conditions regarding the award. The claim award should be based on actual disability and not be restricted to 10% increments.

107. The Council would also like to change awards linked to tuberculosis (TB) and COPD:

a. Patients with pneumoconiosis have an elevated risk of contracting TB

i. With silicosis and mixed dust fibrosis

ii. But not with asbestosis, or coal workers pneumoconiosis

b. There is no reason to restrict TB disability to those with 50% or more disability from silicosis

c. The increased risk also includes non-tuberculous mycobacteria.

108. COPD should not be included in assessment of pneumoconiosis as:

a. COPD is already covered by PD D12

b. COPD is being reviewed in the RD commissioned review being carried out by the IOM.

109. Dr Stenton then summarised the proposed changes to PD D1:

a. Simplified list of pneumoconioses

b. Removing any restrictions about cause

c. Removing the ‘open ’category

d. Changes to the rules about presumption

e. Bringing awards into line with those for other conditions

f. Changing awards for TB and COPD

Causes of pneumoconiosis

Dr Gareth Walters

110. Dr Walters started the presentation by giving an overview of respirable crystalline silica (RCS) and sources of potential exposure:

| Material | Approximate crystalline silica content |

|---|---|

| Sandstone | 70-90% |

| Concrete, mortar | 25-70% |

| Tile | 30-45% |

| Granite | 20-45%, typically 30% |

| Slate | 20-40% |

| Brick | Up to 30% |

| Limestone | 2% |

| Marble | 2% |

111. Emerging causes of pneumoconiosis were then discussed:

a. Stonemasons and bricklayers (26%)

b. Other construction work (25%)

c. Mining and quarrying (20%)

d. Foundry-related occupations (13%)

These occupations were identified from the SWORD database, 2022.

112. In 2016, the HSE published supplementary guidance for occupational health professionals indicating that certain workers were in high-risk occupations e.g.:

a. Construction

b. Foundry work

c. Brick and tile work

d. Ceramics

e. Slate manufacturing

f. Quarries and stonework

The guidance stated that health surveillance for silicosis should be considered where workers are exposed to RCS dust and there is reasonable likelihood silicosis could develop.

113. Dr Walters then discussed other potential sources of exposure, such as that faced by dental technicians or those involved in the artificial stone industry; the frequency of reported silicosis in the latter is significantly increasing.

114. The presentation moved on to discuss metals and chronic beryllium disease (berylliosis) was illustrated. The latter presents as nodules in the lung and lymph glands and mimics Sarcoidosis or Silicosis. Beryllium is a strong but lightweight metal, which is used in alloys with applications in the aerospace and automotive industries and has many other uses. Workers may be unaware of sensitization to beryllium which although treatable can progress to fibrosis.

115. Cobalt was the next metal to be covered and the condition which is caused by exposure to this is referred to by a number of terms:

a. Hard metal disease

b. Cobalt lung disease

c. Tungsten carbide (WC) lung disease.

116. It has a number of applications including hard metal tips produced by sintering. It causes a destructive fibrosis of the lung with a distinctive pattern on X-ray ‘giant cell’ pneumonitis. Exposure can occur during metal machining.

117. The speaker then talked about indium tin oxide which has applications in screens due to its conductive nature - windscreens are made in the UK, so potential for exposure.

118. Indium lung disease is very destructive and has been reported in the far East (none in the UK) due to the manufacture of mobile ‘phones etc. It causes a rapidly progressive fibrosis with little option for treatment.

119. The rare earth metals such as cerium are theoretical potential causes of exposure, but rare:

a. Most abundant rare earth metal “lanthanide”

b. Catalysts, in high performance magnets used in electric motors or turbines, electronics and alloys

c. <20 case reports: carbon arc lamp operators, photoengravers and lens polishers

d. UK – recycling?

e. Diffuse fibrosis or chronic inflammation

120. Although the exposure is rare, all the above metals have been included in the proposed new prescription to future-proof it and ensure no one is disadvantaged.

Comments, questions and answers from the proposed revision of PD D1 – Pneumoconiosis / silicosis session.

121. A representative of the NUM asked if there had been any research that pneumoconiosis and lung cancer are linked. Dr Stenton stated that a review paper had been published recently which did not show an increased risk in coalminers, so would unlikely reach the threshold which IIAC requires.

122. An online attendee asked about mixed dusts from cutting wood, chipboard etc. as this is not included in the proposals. Dr Walters was aware of a link with a form of lung fibrosis from cutting wood, but the link is not strong and there were questions around confounding exposures which may contribute to the fibrosis.

123. An online attendee commented on the proposal to remove payments for IIDB in 1-13% range disability but felt there was no explanation why this formed part of the current prescription. Dr Stenton answered that this was probably included to compensate for loss of earnings when an underground coal worker was suspected of having pneumoconiosis and was moved to be a surface worker.

124. An attendee in the room asked if workers (e.g., nurses/teachers) would be covered if there were exposed to dusts caused by construction work going on around them. Dr Stenton felt workers would be covered if they were exposed as a consequence of their work.

125. The Chair thanked the speakers and the audience for the questions. Dr Rushton stated that the proposals will be laid before Parliament as a command paper in the near future.

COVID-19 and occupational exposures – with Q&A

Dr Jennie Hoyle and Dr Lesley Rushton

126. Dr Rushton started the final talk of the day by stating that COVID-19 had probably been the most difficult topic the Council had ever covered. Data and evidence are being published at a rapid rate so this has been a huge challenge for the Council.

127. The presentation started by giving an overview of COVID. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a virus:

a. First identified end of December 2019 in China as cause of outbreak of ‘atypical viral pneumonia’.

b. Atypical means that it looks and behaves differently in a clinical sense compared to other causes of pneumonia frequently caused by bacterial infection

c. Many bacterial pneumonias will cause an acute respiratory illness which most will recover from over a 4 to 6 week period, although for those who are susceptible such as the frail, elderly, death can occur in the initial illness.

d. SARS-CoV-2 has since been recognised as having more effects on health than just those affecting the respiratory system. This will be covered later in the talk.

128. A graph showing the daily deaths with time was shown which illustrated the waves of the infection and the restrictions that were put in place:

129. The next slide showed the daily cases with time – at the early stages of the pandemic, testing was restricted. Analysis of these data was also challenging.

130. The speaker discussed the changing patterns of work during the pandemic including increasing use of homeworking and redeployment, particularly in the early stages. However, there were around one third of workers who were classed by the government as ‘key’ so continued to go into work.

a. Usual place of work changed in many occupations e.g., home working

b. Redeployment e.g., in hospitals

c. 33% (10.6m) key workers:

i. Health and Social Care (HSC), education, childcare, key public services, local/national government, food manufacture/processing, public safety, transport, utilities, communication, financial services

d. 15% with a health condition considered moderate risk

e. Many (approx. 30%) in 3 lowest pay deciles

f. Many of the key workers could not work from home:

i. 80%+ accommodation, food services, transport, storage

ii. 70-76% HSC, retail, construction, manufacturing

131. Dr Rushton explained that during the early stages of the pandemic, there was a lot of focus on preventing viral transmission through touching surfaces. However, as time progressed, it was acknowledged that the virus was mostly transmitted by droplets and inhalation was the main mode of transmission as shown below.

132. Environmental and personal factors affecting transmission were then discussed:

a. Poorly ventilated spaces increase transmission

b. Cold environments with dry air maintain the viability of the virus

c. Singing, shouting, loud talking increases emission

d. Wearing respirators, surgical masks and face coverings reduces emission and may offer protection

e. Avoiding close contact with infected individuals reduces chance of transmission.

133. There were a number of outbreaks in workplaces, and this is something the Council is currently looking at. The HSE have collected a lot of data which will be useful for the Council’s work. The speaker then discussed risks of infection by occupation and the sources of information available. There are numerous studies particularly in healthcare, but fewer in the community generally. Access to testing in the UK and other countries was limited early on with sectors such as healthcare being prioritised; many studies in this sector were therefore opportunistic.

a. Interpretation of these studies is often limited by biases such as:

i. test availability

ii. small sample sizes or unclear participation rates

iii. lack of comparator populations

iv. imprecise exposure estimates

v. no control for confounders or other variables

b. Informative population studies include: ONS, REACT, Virus-Watch, PHE, Biobank

c. Series of studies show how risks vary over the pandemic with risks often being higher when the general population infection rate was also high.

134. After assimilation of various data sources, IIAC was able to gather enough evidence for health and social care workers (H&SCWs). There is clear evidence that HSCWs have increased risk of infection compared to general population which was very high during the first wave. Rates fell when community rates fell but there is good evidence of an increase in subsequent waves. Studies in hospitals tended to show higher infection rates in those with patient-facing roles than non-patient facing roles. Similar results were found for sickness absence.

135. Mortality by occupation data showed high rates for several groups within H&SCWs. Other occupations which came out high included taxi/cab drivers and security guards.

136. IIAC concluded that for H&SCWs there was a large body of consistent supporting evidence from infection, morbidity and mortality data showing significantly increased risk. IIAC recommend prescription for Workers in hospitals and other healthcare settings, Care Home Workers and Home Care Workers working in proximity to patients/clients in the 2 weeks prior to infection. The speaker noted that that Infection (and mortality) was now declining for H&SCWs.

137. The Council considered other occupations whilst evaluating the risks for HSCWs and concluded that:

a. There was evidence for increased risk from several occupations including transport, protective services

b. However, at the time there were far fewer studies with more inconsistent results

c. The evidence was weaker, so Council concluded that, at that time, there was insufficient evidence to prescribe for other occupations.

138. More evidence is now emerging including more extensive mortality and infection data and data for outbreaks. IIAC is currently evaluating this for:

i. Transport: mortality consistently raised but not infection

ii. Education: Infection consistently raised when schools open; mortality not raised.

COVID-19 long-term complications

Dr Jennie Hoyle

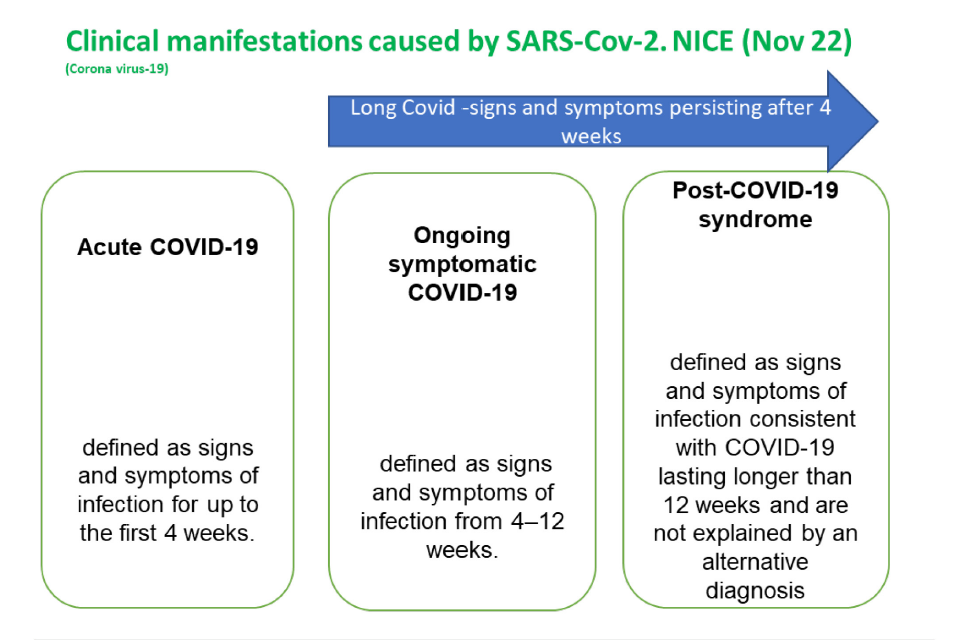

139. Dr Hoyle relayed some of her experiences of working as a respiratory disease physician on the front line and how some additional complications of having had COVID-19 were emerging, which is continuing to evolve today. Dr Hoyle showed a slide which illustrated the definitions of the progression of the disease:

140. Symptoms of acute and long-covid were then described:

a. Approximately 1/3rd of people who develop COVID-19 do not develop acute symptoms

b. The majority recover within the first few weeks of illness

c. However, published reports indicate that approximately 10– 20% of COVID-19 patients experience lingering symptoms for a number of weeks to months following acute SARS-CoV-2 infection[footnote 4].

d. Symptoms can be varied and multi-system, cluster, overlap and fluctuate – this is a complicating factor for IIAC

e. Not all symptoms have a clear pathophysiological basis – this is also an issue for IIAC.

141. How IIAC has approached post COVID-19 was then explained:

a. Complications or consequences of infection with SARS-Cov-2 which cause prolonged or long-term impairment which likely lead to a disability.

i. Have a measurable diagnostic

ii. New onset and timely in relation to likely infection

iii. Infection confirmed (where tests are/were available), if not when deemed clinically probable and cannot be explained by an alternative diagnosis[footnote 5].

142. Dr Hoyle then showed a slide which illustrated a large range of complications of infection and demonstrated this is a multi-system disorder which is debilitating.

143. Working through the evidence, IIAC identified five conditions, which develop as a consequence of having had COVID-19, which it was able to recommend for prescription:

a. Persisting pneumonitis or pulmonary fibrosis

b. Pulmonary hypertension following pulmonary embolus

c. Ischaemic stroke

d. Myocardial Infarction

e. Post Intensive Care Syndrome

These conditions were then explained by Dr Hoyle.

144. Persisting pneumonitis or pulmonary fibrosis:

a. This is a scarring condition of the lung where persisting inflammation impairs oxygen transfer into the blood stream

b. It is rare under the age of 65

c. The likelihood of persisting lung abnormalities is related to the initial severity of infection

d. These conditions improve over time; however a small percentage persist over 1 year

e. The disability caused by these is measurable with lung function testing and radiology.

145. Pulmonary hypertension following pulmonary embolus:

a. Blood clots form in the deep veins and travel to the lungs, where they obstruct circulation

b. There is clear evidence of increased risk following infection with SARS-Cov-2, with rates much higher compared to other infections

c. There are specific pathological mechanisms (coagulopathy), extending beyond acute infection (up to 3 months).

d. Pulmonary hypertension results from the persisting burden of clots in the lungs causing pressure on the heart

e. It is measured using radiography and echocardiography techniques, disability can be measured using walking tests, oxygen saturations.

146. Ischaemic stroke:

a. Again, there is clear evidence of an increased risk of stroke following infection with SARS-Cov-2

b. Incident rate ratios of stroke were doubled or more in the acute phase and were likely to remain raised for 28 days following infection

c. The relationship between hemorrhagic stroke and SARS-Cov-2 infection is, however, less clear

d. Many patients will recover, but in others there will be measurable changes on radiography and residual demonstrable disablement which may range from limb weakness, visual loss, cognitive impairment.

147. Myocardial Infarction:

a. The increased risk evidence is similar to that of ischaemic stroke

b. Persisting breathlessness and chest pain is experienced

c. The effects are measurable on ECG, echocardiography and blood tests

d. Disability experienced relates to breathlessness, chest pain and exercise impairment.

148. Post Intensive Care Syndrome:

a. Intensive Care Unit survivors are recognised to suffer from new physical and non-physical health problems

b. Many will usually have improvement in symptoms over the first 6-12 months following hospital discharge

c. Some can have reduced ability to work due to reduced exercise capacity (muscle weakness), nerve damage (neuropathy), impairments of memory and concentration

d. This may last years and those affected will have a recognised period of requiring advanced respiratory support

149. Post-COVID syndrome (long-covid) is a challenging condition, which Dr Hoyle discussed:

a. The range of persisting symptoms in literature is wide

b. Many symptoms are not specific to COVID-19 infection e.g. tiredness

c. The pathophysiological mechanism behind many symptoms is still largely unknown – the studies of literature are lacking

d. Diagnosis does not have a specific test yet

e. NICE (Nov 2022) acknowledges the lack of certainty of the evidence base. The current evidence base is moderate to low in terms of quality

f. The risk of bias due to study design is moderate to high for symptoms described (fatigue, breathlessness)

150. The last slide presented by Dr Hoyle addressed the future work for IIAC:

a. The council recognises the importance and the need to review evidence as more information comes to light

b. IIAC continues to review the evidence in terms of occupation

c. Specifically, IIAC are currently reviewing the literature on transport workers and workers in education

d. In terms of post-COVID syndrome (long-covid) IIAC continue to monitor evidence as it emerges; however, information regarding long-covid related to occupation is sparse.

151. Dr Rushton thanked the speaker and invited questions.

Comments, questions and answers from the COVID-19 and occupational exposure session.

152. An online attendee commented that the Council identified risks in certain occupations, but across all sectors people have continued to go into work and risk being exposed to COVID, so felt the job was important rather than the sector they worked in. Dr Rushton explained that when the Council recommends prescription, it has to have a link between work and the disease. There have been studies which showed key workers had higher risks, but reflecting this in a prescription would be very difficult. Data on outbreaks, which the Council are waiting for, may help define how the Council looks at this. Dr Hoyle added that, in general, occupational data have sometimes been poor or difficult to obtain.

153. Another online attendee asked if the Council can make recommendations on what infections and conditions are reportable e.g. continued COVID-19 exposure indicative of increased risk or women developing breast cancer in particular occupations. Dr Rushton responded that that is not something the Council can easily do – reporting systems such as SWORD, are useful but otherwise it is down to individual physicians to make reports. Dr Hoyle commented that the HSE is a reporting body, RIDDOR being part of that.

154. An online attendee asked if H&SCWs would continue to be monitored for other post-COVID conditions. Dr Hoyle answered that all the conditions would be monitored as little is known around the background for long-covid and the mechanisms behind this.

155. A Unite Union representative commented they felt there was a case for prescription in transport workers and those in education. They made the point that there were differences in socio-economic situations between these occupational groups e.g., not such good sick-pay schemes in the transport sector, which may account for the lower infection rates but higher mortality. Transport workers, such as bus drivers, are exposed to both colleagues and the general public which might affect risk. Similarly for the education sector. The attendee asked when the investigation into other occupational groups would be completed. Dr Rushton stated IIAC has quite a lot of data, but infection data for transport is meagre. The demographics between education and transport are different, but there is difficulty in obtaining occupational data for both. There are a variety of jobs within the transport sector with different risks and with differences in death rates being higher in those who are public facing. Also, there is a tendency for transport workers to have more obesity or diabetes which will influence the death rates following COVID-19. There were also differences in the education sector with early years (nurseries) staying open and similarly for teaching assistants who remained in the schools, whereas teachers and lecturers tended to teach online. Consequently, Dr Rushton was unable to give a timeline, but alluded it would take some time to work through everything.

156. Another attendee asked if there would be any lessons learned from this pandemic and would there be better preparedness in the future. Dr Rushton stated IIAC would be unable to answer that, but from its own perspective, for a situation where there are no data IIAC will be better informed. However, its investigations are unlikely to be quicker.

Open forum and closing remarks

Mr Daniel Shears - Representative of employed earners.

Dr Sharon Stevelink – independent scientific expert.

157. Dan Shears introduced himself and stated he would be compering the session, bringing in other members as necessary. Some questions had been given in advance, some would be taken from online and others from in the room.

158. A representative of mineworkers asked about COPD, specifically the 20 year / 40 year rule for PD D12 in mineworkers as surface workers and those who worked underground. Some surface worker jobs were in very confined spaces so these workers were exposed to more dust than some underground workers. Dr Stenton stated the 20 year rule for underground workers came from a series of studies. IIAC is looking for a level of exposure where the risk of getting the disease is doubled as presumption can then be applied. The studies, carried out in the 1970s and published in the 1980s, showed that the risk of developing COPD was doubled after working the equivalent of 20 years with 6 mg/M3 dust in the air. There has been nothing published in the literature since then which calls this into question.

The second question around the levels of exposure for some surface workers would need to be checked as it was assumed the exposure level for a surface worker would be half that of an underground worker. Dr Stenton stated that if there was evidence that the levels of exposure in mineworkers was different to that reported, then IIAC would need to look at it again.