HPR volume 10 issue 15: news (15 April)

Updated 16 December 2016

1. Zika virus: epidemiological update

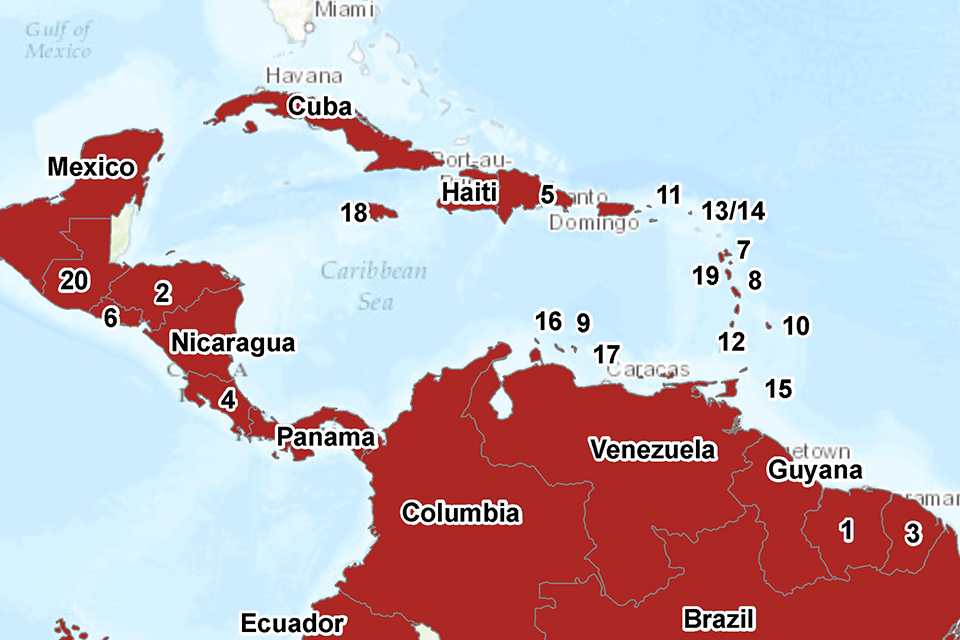

As of 14 April, 48 countries and territories worldwide have reported confirmed cases of autochthonous (locally acquired) Zika virus infection in the last nine months (see the PHE Zika webpage [1] for latest information). Countries and territories in the Americas (South and Central America) and the Caribbean continue to account for the majority of countries currently reporting active transmission (34 out of 48) (see Americas map below; and PHE global map). It is anticipated that in the coming weeks and months further countries and territories within the geographical range of competent mosquito vectors – especially Aedes aegypti – will report autochthonous transmission.

AUTOCHTHONOUS TRANSMISSION IN THE AMERICAS IN THE LAST NINE MONTHS (Bolivia and Paraguay not shown). Numbered countries are as follows: 1. Suriname; 2. Honduras; 3. French Guiana; 4. Costa Rica; 5. Dominican Republic; 6. El Salvador; 7. Guadeloupe; 8. Martinique; 9. Curacao; 10. Barbados; 11. US Virgin Islands; 12. Saint Vincent and the Grenadines; 13/14 Saint Martin/Sint Maarten; 15. Trinidad & Tobago; 16. Aruba; 17. Bonaire; 18. Jamaica; 19. Dominica; 20. Guatemala.

Aedes albopictus, a potential vector of Zika virus, is established in most places around the Mediterranean coast [2]. While the vector competence of this species has not yet been confirmed for European mosquito populations, during the summer season (most likely from July by analogy with other mosquito-borne disease transmission in the EU), autochthonous transmission in the continental European Union – following the introduction of the virus by a viraemic traveller – may be possible in areas where Aedes albopictus is established [3].

To date, within continental Europe, no autochthonous cases of Zika virus infection due to vector-borne transmission have been reported. As of 14 April, ECDC has recorded 409 imported cases in 17 EU/EEA countries [4].

In the UK, the risk of autochthonous, vector-borne Zika virus transmission is deemed to be negligible for climatic reasons (that preclude the Aedes mosquito vector surviving). As of 13 April, 14 imported Zika virus cases associated with the current outbreak have been reported in the UK (from Barbados, Brazil, Colombia, Curacao/Venezuela, Guyana/Suriname, Jamaica, Mexico/Venezuela and Venezuela) [1].

While almost all cases of Zika virus infection are acquired via mosquito bites, a small number of possible cases of sexual transmission from males to their sexual partners (both male and female) have been reported in non-outbreak countries. Advice on how to prevent infection (including via sexual transmission) is available on the PHE [1] and NaTHNaC websites [5].

The majority of people infected with Zika virus have no symptoms. For those with symptoms, Zika virus tends to cause a mild, short-lived (2 to 7 days) illness [1]. Based on a growing body of research, there is scientific consensus that Zika virus is a cause of microcephaly and other congenital anomalies (also referred to as congenital Zika syndrome) and Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) [6,7,8]. To date, microcephaly and other foetal malformations potentially associated with Zika virus infection have been reported in six countries: Brazil (1,113 cases), Cape Verde (2), Colombia (7), French Polynesia (8), Martinique (3) and Panama (3). Two further cases, each associated with a stay in Brazil, were detected in Slovenia and the United States of America [6].

In addition, 13 countries worldwide have reported an increased incidence of GBS and/or laboratory confirmation of a Zika virus infection among GBS cases [6]. More studies are required to determine the spectrum of effects of Zika virus infection, the frequency at which complications occur, and the factors that determine or influence outcomes of infection.

Additional information on Zika virus infection as well as guidance for health professionals can be found on the PHE website [1]. Travel advice can be found on the NaTHNaC Travel Health Pro website [5].

Recent and past publications on Zika virus infection can be found in the following collections: WHO; WHO PAHO; CIDRAP; The Lancet; and Transactions of the RSTMH.

1.1 References

-

PHE website. Zika virus: health protection guidance collection.

-

ECDC. Communicable Disease Threats Report, week 15: 10-16 April 2016.

-

NaTHNaC Travel Health Pro. Zika virus resources.

-

WHO. Zika virus, microcephaly and Guillain-Barré syndrome situation report, 14 April 2016.

-

ECDC. Accumulating evidence on Zika virus disease and potential link to severe outcomes.

-

Rasmussen et al (2016). Zika virus and birth defects – Reviewing the evidence for causality.

2. Yellow fever in Angola

Since December 2015, an outbreak of yellow fever (YF) has been ongoing in Angola. As of 10 April 2016, 1,751 suspected cases including 242 deaths (case fatality: 13.8%) have been reported in 17 of 18 provinces; 582 cases have been confirmed [1]. Luanda, the capital of Angola (see map [2]), is the most affected province where 406 confirmed cases and 165 deaths have been reported. While cases are increasing in other affected provinces, including Huambo (85 confirmed cases) and Benguela (22 confirmed cases), there are some early indications that overall incidence is decreasing. Angola is a YF-endemic country but this is the worst outbreak to occur there in 30 years [3].

Cases have been reported in both Angolan nationals and expatriates resident in Angola, including nationals of Cape Verde, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Eritrea, India and Lebanon [4]. At least six Chinese citizens have also died from YF while in Angola [5]. In addition imported cases – in travellers who had recently returned from Angola – have been reported in China (nine cases) [6], DRC (three cases) [7], Kenya (two cases) [8] and Mauritania (one case) [4]. In DRC, locally-acquired cases of YF are regularly reported; between early January and 22 March 2016, 151 suspected cases including 21 deaths had been reported, mostly in the northern part of the country not bordering Angola [7]. Only four of these cases have been confirmed in DRC so far, of which three were acquired in Angola.

A vaccination campaign began in Luanda in early February to control the outbreak and, as of 10 April 2016, 90% of the target population had been vaccinated and case numbers in Luanda have decreased. Huambo province launched their vaccination campaign on 12 April and a campaign in Benguela is in preparation. Support for the response activities is being provided by the World Health Organization (WHO) and other international partners [1].

2.1 Background

The yellow fever virus (YFV) can cause an illness that results in jaundice (yellowing of the skin and eyes) and bleeding with severe damage to the major organs (eg liver, kidneys and heart). The mortality rate is high in those who develop severe disease [9]. YFV circulates between infected monkeys or humans and mosquitoes, and is a risk in tropical parts of Africa, South America, eastern Panama in Central America and Trinidad in the Caribbean. Areas with a “risk of YF transmission” (also known as endemic) are countries (or areas within countries) where mosquito species known to transmit the disease are present and where the infection is reported in monkeys and/or humans. Around 90% of reported YF cases occur in sub-Saharan Africa [10].

YF is a vaccine-preventable disease. In order to prevent the international spread of YF, under the International Health Regulations 2005) (IHR) [11], countries may require proof of vaccination, recorded in an International Certificate of Vaccination or Prophylaxis (ICVP). A Medical Letter of Exemption from vaccination may be taken into account by a receiving country, and can be considered in some circumstances if the vaccine is contraindicated.

2.2 Advice for travellers

Yellow fever is a rare cause of illness in travellers. Between 1970 and 2013, only 10 cases have been documented in unvaccinated travellers from the United States and Europe who travelled to risk areas in Africa or South America [5,12]. The imported cases recently reported in China highlights the need to reinforce YF vaccine recommendations and certificate requirements for all travellers who visit countries with risk of yellow fever.

YF is transmitted by mosquitoes. All travellers visiting countries with a risk of any disease transmitted by mosquitoes should take insect bite avoidance measures, day and night.

As well as mosquito bite avoidance, vaccination is recommended for personal protection for anyone travelling to or through areas of Angola or any other countries with risk of yellow fever. Under the IHR, a yellow fever vaccination certificate is required from all travellers over 1 year of age travelling to Angola [13].

Further information about yellow fever, including vaccine recommendations and certificate requirements under the IHR for each country, is available from the NaTHNaC Travel Health Pro website.

If a case of yellow fever is suspected, samples should be sent to the PHE Rare and Imported Pathogens Laboratory (RIPL); this should be done by liaising with the local diagnostic laboratory. Full clinical and travel history details (including relevant dates) should be provided on the request forms.

The Imported Fever Service is available to health professionals should specialist advice be needed.

2.3 References

-

WHO Regional Office for Africa (11 April 2016). Situation Report: Yellow fever outbreak in Angola.

-

WHO (March 2016). Angola grapples with worst yellow fever outbreak in 30 years.

-

ECDC (1 April 2016). Epidemiological update: outbreak of yellow fever in Angola.

-

ECDC (24 March 2016). Rapid Risk Assessment: Outbreak of yellow fever in Angola.

-

WHO (6 April 2016). Disease Outbreak News: Yellow fever – China.

-

WHO (11 April 2016). Yellow Fever – Democratic Republic of the Congo.

-

WHO (6 April 2016). Yellow fever – Kenya.

-

NaTHNaC Travel Health Pro website (13 April 2016). Yellow fever factsheet.

-

WHO (22 March 2016). Yellow fever: Questions and Answers.

-

WHO (2005). International Health Regulations: 1-60.

-

Chen J, Lu H (2016). Yellow fever in China is still an imported disease. BioScience Trends (online).

-

NaTHNaC Travel Health Pro website (31 March 2016). Yellow fever in Angola.

3. Outbreak of high level azithromycin resistant gonorrhoea in England

A National Resistance Alert was issued to microbiologists in England in October 2015 calling for all gonococcal samples to be tested for azithromycin resistance and for resistant isolates to be referred to PHE’s Sexually Transmitted Bacteria Reference Unit (STBRU). This followed evidence of a potential outbreak of high-level azithromycin resistant (HL-AziR) infections in the north of England.

According to a new report on the situation published in this issue of HPR [1], the outbreak has since spread to the West Midlands and south of England, including London. Initial cases were among heterosexuals but more recent evidence suggests HL-AziR infections are now spreading among men who have sex with men.

PHE continues to monitor and investigate gonorrhoea HL-AziR gonococcal infections and further reminders to raise awareness among clinicians and microbiologists have been issued.

3.1 Reference

- Outbreak of high level azithromycin resistant gonorrhoea in England. HPR 10(15): infection report.

4. Training for participation in fifth HCAI point prevalence survey

PHE is coordinating English participation in the European Centre for Disease Control (ECDC) Point Prevalence Survey (PPS) on HCAI. This will be England’s fifth PPS on HCAI and second national survey on antimicrobial consumption and prescribing quality indicators. PHE has invited all acute hospitals in England to participate in the PPS which should occur over any two week period in each hospital between September and November 2016. Letters were sent to the Directors of Infection Prevention and Control (DIPCs) and Chief Pharmacists in February 2016 requesting each Trust to nominate two surveillance leads (eg lead IPC nurse and antimicrobial pharmacist) and email names to PPSEngland@phe.gov.uk by 30 April 2016. To date almost 50% of NHS acute Trusts have signed up.

Training courses to aid participation will be provided in June 2016. Currently confirmed training dates are as follows (a further date and venue for the north east of England has yet to be agreed):

- Manchester: Tuesday 7th June 2016

- London: Monday 13th June 2016

- Bristol: Monday 20th June 2016.