Health Assessment Channels Research

Published 7 October 2024

DWP research report no. 1072

A report of research carried out by Ipsos on behalf of the Department for Work and Pensions. Crown copyright 2023.

You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence.

To view this licence, visit the National Archives

Or write to:

Information Policy Team

The National Archives

Kew

London

TW9 4DU

Email: psi@nationalarchives.gov.uk

This document/publication is also available on our website at: Research at DWP

If you would like to know more about DWP research, email: socialresearch@dwp.gov.uk

First published October 2024.

ISBN 978-1-78659-724-3

Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and Pensions or any other government department.

1. Executive summary

DWP conducted a Health Assessment Channels Trial to evaluate how well telephone and video assessments are working compared to face-to-face assessments. This report presents findings from mixed-method research conducted by Ipsos to understand the impact of the introduction of remote channels on claimant experiences.

1.1. Research design

This research comprises a multi-mode (online and CATI) survey conducted between the 3rd of March and 1st of May 2023. In total 7,262 responses were received from Personal Independence Payment (PIP), Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) or Universal Credit (UC) claimants who had an initial health assessment for their benefit between June 2022 and January 2023.

Key Drivers Analysis was run using the quantitative data. This identified which areas of the assessment were most important in determining participant agreement that that the assessor had understood their condition and how it affected their everyday life (for PIP claimants) or ability to work (for UC or ESA claimants). Sixty follow-up qualitative telephone interviews were also conducted to understand the assessment experience in more depth.

1.2. Findings

Findings from the quantitative survey, Key Drivers Analysis and qualitative interviews did not identify clear patterns in claimant beliefs that the assessor understood their health condition or disability, or that they had been able to explain this properly, by assessment channel (Section 6.6).

Rather, Key Drivers Analysis identified that perceptions of whether the assessor had understood their health condition or how it affected them were driven by agreement that:

- the questions which were asked allowed them to explain how their condition affected them

- the assessor had understood their application form and other evidence

- the assessor had listened to them during the assessment

The qualitative research found that positive interactions with an assessor were characterised by the assessor explaining the assessment process, having a high degree of confidence in the assessor’s ability to assess their condition and the assessment feeling tailored to their condition (or understanding the purpose of questions which felt less relevant).

This suggests that assessors should prioritise these behaviours. The evidence suggests that assessors can demonstrate these behaviours across all three assessment channels (face-to-face, telephone or video).

PIP claimants were more likely to express uncertainty about all the channels. This suggests that PIP claimants may need additional support or reassurance through the assessment process.

Claimants were more likely to agree a channel was suitable after experiencing it. Future preferences for assessment channel were strongly correlated to the channel claimants had experienced most recently. Participants who had a positive interaction with the assessor also had high confidence in their assessment channel (Section 7.2).

In the survey, awareness of the ability to change channel amongst trial participants was low. A minority of participants had changed from the assessment channel initially allocated for their assessment. The qualitative interviews identified that participants only changed their assessment channel when they could not attend the channel they had originally been allocated. They did this regardless of whether they recalled that they had been told they could change their assessment channel (Section 4.2).

When asked in the survey if they would like a choice of which channel their assessment is conducted by in the future, nearly nine in ten said that they would. In the qualitative research, offering a choice of assessment was seen as giving participants control over part of the process, empowering them. Participants felt they could choose the channel which they felt was appropriate for their condition and needs (Section 8.2).

Acknowledgements

This research was commissioned by the Department for Work and Pensions.

The authors would like to thank all of the people who gave their time to participate in this research.

We would also like to thank Deborah Grayson, Gursharan Gill, Abigail Holland and Bella Barton for their valuable input throughout the study.

2. Summary

2.1. Introduction

DWP commissioned Ipsos to conduct quantitative and qualitative research into the experience of respondents who had an initial health assessment as part of their benefit claim during the Health Assessment Channels Trial. DWP conducted the Health Assessment Channels Trial to evaluate how well telephone and video assessments are working compared to face-to-face assessments. The trial compares award outcomes across channels for people who have attended an initial Personal Independence Payment (PIP) assessment or Work Capability Assessment (WCA), who were eligible to attend all three channels, and whose assessment was automatically allocated to one of those channels. To understand the impact of the introduction of remote channels on claimants, DWP commissioned Ipsos to conduct a mixed-method study exploring claimant experiences. The trial and research will develop the evidence base on the use of different channels, inform wider implementation, assess value for money and determine next steps.

2.2. Study methodology

This research comprises a multi-mode (online and CATI) survey conducted between the 3rd of March and 1st of May 2023. In total 7,262 interviews were conducted with PIP, Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) or Universal Credit (UC) claimants who had an initial health assessment for their benefit between June 2022 and January 2023. The quantitative data was used to run a Key Drivers Analysis, to identify which areas of the assessment were most important in determining agreement that the assessor had understood their condition and how it affected them. As well as identifying the areas which were important to determining this, it identified how well the assessment experience was performing against these metrics.

Sixty follow-up qualitative telephone interviews were conducted to understand claimants’ assessment experience, and the role of assessment channel, in more depth.

2.3. Key findings

Information about the assessment

Over nine in ten (93%) recalled receiving information about their assessment before it took place. DWP was the most commonly recalled source of information and those who had a face-to-face assessment were most likely to recall receiving information from DWP. Participants recalled that the information related to the practicalities of attending the assessment, such as location, appointment length and the overall process.

Over eight in ten (81%) of claimants found the information provided by DWP or the assessment provider clear. There were no differences in the perceived clarity of information by assessment channel. However, ESA and UC claimants were more likely to have found the information clear than PIP claimants (Section 4.1).

A quarter of participants knew that they could ask for their allocated assessment channel to be changed. Overall, 12% had their assessment using a different channel to the one originally allocated, including those whose assessment channel was changed by the provider and participants who changed their assessment channel themselves. The qualitative interviews found that people requested to change assessment channel out of necessity, such as being unable to travel to a face-to-face appointment or take part in a video call, rather than preference (Section 4.2).

Perceptions before the assessment

Before receiving the invitation to the assessment, participants were more likely to be aware that they might need to have an assessment than why or what would happen. Awareness of the need to have an assessment was higher among PIP claimants (89%) than UC (82%) or ESA (81%) claimants (Section 5.1).

For most (at least six in ten) participants, knowing that the assessment could be carried out using telephone, video or face-to-face made no difference to their intention to make a benefit claim. Participants were most likely to say that knowing the assessment could be carried out face-to-face would make them less likely to apply whilst knowing that it could be carried out over the telephone would make them more likely to apply (Section 5.2.1).

Before the assessment, over half of participants felt that the assessor would be able to assess their condition very or fairly well using their assessment channel. Participants were most likely to express doubts about telephone or video assessments (38% each) and less so about face-to-face (28%). Across all channels, PIP claimants were least confident that an assessor would be able to accurately assess their condition (Section 5.2.2).

The qualitative interviews found that participants’ attitudes to claiming benefits shaped their attitudes towards the assessment. We identified three broad groups. The first group were reluctant to claim, and felt a stigma attached to doing so. They did not expect to receive a benefit award and expected the assessor to be hostile towards them (reflecting the stigma they attached to claiming). The second group included those who were uncomfortable about discussing their health condition. This group were at risk of leaving out important information or downplaying the severity of their condition. The third group had high confidence in being awarded their benefit claim and felt that this would validate the extent to which their condition affected them (Section 5.2.3).

Assessment experience

Nine in ten participants agreed that the appointment time they were offered was convenient and they were informed of this with time to prepare.

Despite this, six in ten said they were concerned about the assessment on the day. This was most likely amongst those who had a face-to-face assessment. PIP or UC claimants were more likely to be concerned than ESA claimants. The qualitative interviews found that the assessment was a significant event for participants which they found preparing for, and attending, stressful. Participants felt that more information about what would be covered in the assessment could help them to prepare and mitigate their anxiety about attending (Section 6.2).

The quantitative and qualitative strands identified that the interaction with the assessor was key to determining perceptions that the assessor had understood their condition. The qualitative interviews identified that feeling the assessor understood their condition helped ensure the legitimacy of the assessment, including for participants who were not given a financial award.

Overall, participants were most likely to agree that the assessor had treated them well. They were less likely to agree that they felt they had been able to explain how their condition affects them. Nine in ten agreed that the assessor treated them with respect and dignity through the assessment and the same proportion agreed that the assessor explained their role. Participants were less likely to agree that the questions asked were relevant and appropriate (74%) or that they allowed them to fully explain the impact of their condition (70%). Fewer were likely to agree that they had been able to explain how their health condition affects their daily life and / or ability to work (68%) or that the assessor understood this (61%). Experiences were consistent across assessment channels. PIP claimants were consistently less positive across all measures than ESA or UC claimants (Section 6.5).

The Key Drivers Analysis (KDA) identified that feeling listened to, feeling that the assessor had read and understood their application form, and being asked relevant questions, determined agreement that the assessor had understood their condition. Assessment channel did not play a role in this. In the analysis, DWP was performing strongly across these measures.

The qualitative interviews identified several characteristics of a positive assessment experience:

- the assessor introducing themselves and explaining their professional background

- the assessor explaining the purpose of the assessment and that not all questions would be relevant

- the assessor demonstrating that they had read the application form in advance

- participants understanding the questions and feeling able to answer them accurately, with support and further explanation from the assessor if needed

- the assessment feeling tailored to the individual’s needs and condition

Participants who had these experiences were more likely to feel positively about the assessment overall.

Together, the KDA and qualitative findings show the importance of the participant’s interaction with the assessor in determining agreement that their health condition, and how it affects them, had been understood. This identifies behaviours and actions for assessors to prioritise (Section 6.6).

Around two thirds of participants felt that their assessment channel was suitable. This was consistent across channels. PIP claimants were least likely to see their assessment channel as being suitable, across all assessment channels. This suggests that perceived suitability is related to the needs of PIP claimants rather than the channel (Section 6.9).

Having an assessment using a particular channel influenced perceptions of suitability. Claimants were more likely to see a channel as suitable after they had had an assessment using it, than before the assessment (Section 6.9).

Assessment outcomes and satisfaction

PIP claimants were most likely to know their assessment outcome at the point of the survey (91% compared to 82% of ESA claimants or 83% of UC claimants). They were also least likely to be satisfied with their outcome (44% compared to 69% of ESA and 71% of UC claimants).

There were no significant differences in satisfaction with outcomes between the different assessment channels (just over half for each channel). However, claimants who had a video assessment were more likely to be dissatisfied with the outcome of their assessment (43%) than those who had a face-to-face assessment (37%). There were no significant differences in dissatisfaction between either of these channels and those who had a telephone assessment (39%).

Those who were satisfied with their assessment outcome were more likely to agree that the assessor had understood their condition and how it affects their daily life or ability to work (Section 7.1).

Qualitative findings showed that claimant perceptions of the suitability of their assessment channel depended on how well they felt the assessor had understood their health condition. There was a relationship between claimants’ satisfaction (or dissatisfaction) with the interaction with assessor and their satisfaction (or dissatisfaction) with their award outcome.

Claimants who felt their assessment channel was more suitable than expected after receiving their award outcome were more likely to have had an assessment using remote channels. This group were likely to have been uncertain about having an assessment through a remote channel prior but felt positively about their interaction with the assessor following the assessment.

Claimants who felt that their assessment channel was less suitable than expected after receiving their award outcome were more likely to have had an assessment using remote channels and be dissatisfied with both their interaction with the assessor and award outcome. These claimants felt that the remote assessment channel had not enabled them to fully demonstrate how their condition affected them (Section 7.2).

Channel choice

When asked in the survey, 86% of participants said they wanted a choice of how their future assessments were carried out. Future preference for channel was closely correlated with the channel which participants had experienced for their most recent assessment.

In the qualitative interviews, participants felt that being offered a choice of assessment would enable them to choose the channel which they felt was appropriate for their condition and which would help them to best manage the emotional impact of the assessment. Participants felt that this would give them a sense of control and empowerment over the process (Section 8.2).

2.4. Conclusions

Findings from the quantitative survey, Key Drivers Analysis and qualitative interviews did not identify clear patterns in claimant beliefs that the assessor understood their health condition or disability, or that they had been able to explain this properly, by assessment channel.

Rather, Key Drivers Analysis identified that perceptions of whether the assessor had understood their health condition or how the participant’s disability affected them were driven by:

- being asked questions which allowed them to explain how their condition affected them

- feeling that the assessor had understood their application form and other evidence

- feeling listened to during the assessment

The qualitative research found that positive interactions with an assessor were characterised by the assessor explaining the assessment process, having a high degree of confidence in the assessor’s ability to assess their condition and the assessment feeling tailored to their condition (or understanding the purpose of questions which felt less relevant).

This suggests that assessors should prioritise these behaviours. The evidence suggests that assessors can demonstrate these behaviours across all three assessment channels (face-to-face, telephone or video). PIP claimants were more likely to express uncertainty about all the channels. This suggests that PIP claimants may need additional support or reassurance through the assessment process.

Claimants were more likely to agree a channel was suitable after experiencing it. Future preferences for channel were strongly correlated to the channel claimants experienced most recently. Participants who had a positive interaction with the assessor also had high confidence in their assessment channel.

Overall awareness of the ability to change assessment channel was low, and a minority of participants had changed the channel for their assessment. The qualitative interviews identified that participants only changed their assessment channel when they could not attend the channel they had originally been allocated. They did this regardless of whether they recalled that they had been told they could change channel.

When participants were asked about future choice, nearly nine in ten said they would like a choice of which channel their assessment is conducted using in the future. In the qualitative research, offering a choice of assessment was seen as giving participants control over part of the process, empowering them. Participants felt they could choose the channel which they felt was appropriate for their condition and needs.

3. Background and Methodology

3.1. Research background

Government financial support is available for people who are ill or have a health condition or disability which affects their ability to work or who have extra living costs because of their disability or health condition. People with limited capability for work and work-related activity (LCWRA) can claim an additional amount of Universal Credit (UC). New Style Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) is available to people who are ill or have a health condition or disability which affects their ability to work and who have been working within the last 2 to 3 years and have made (or been credited with) Class 1 or Class 2 National Insurance Contributions (NICs) before the year they are claiming in.

Personal Independence Payment (PIP) can help people with extra living costs if they have a long-term physical or mental health condition or disability and experience difficulty doing certain everyday tasks or getting around because of their condition. PIP is not income-related or means tested and people can claim PIP whilst they are in work.

As part of the claim process for UC LCWRA, ESA or PIP, claimants complete an application, provide evidence of how their health condition affects them and commonly have a health assessment.

DWP conducts around 1.9 million health assessments each year. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, 80% of assessments were conducted face-to-face and 20% were based on a review of application forms and supporting evidence. During the COVID-19 pandemic face-to-face assessments were stopped and remote health assessments by telephone and video were introduced, reflecting the social distancing regulations in place and the health vulnerabilities of these claimants. This represented a significant change to practice for DWP and claimants.

DWP conducted the Health Assessment Channels Trial to evaluate how well telephone and video assessments are working compared to face-to-face assessments. The trial has compared award outcomes across channels for people who have attended an initial PIP assessment or Work Capability Assessment (WCA), who were eligible to attend all three channels, and whose assessment was automatically allocated to one of those channels. To understand the impact of the introduction of remote channels on claimants, DWP commissioned Ipsos to conduct a mixed-method study exploring claimant experiences.

3.2. Research aims

The aim of this research was to understand what impact assessment channel had on claimant experience. It aimed to provide evidence on how claimant experience differed according to assessment channel and claimant characteristics, allowing DWP to consider the merits of each channel.

The quantitative survey explored:

- whether and how channel affected the claimant experience of the assessment

- the extent to which claimants felt able to convey what they needed to the assessor during their assessment and whether this was influenced by channel

- the extent to which there is claimant appetite for channel choice or change and whether this varies by claimant group or characteristics

- what the barriers are to having an assessment using the different channels

The qualitative strand explored the experience of participants in greater depth, specifically:

- claimant experiences of the assessment

- experiences of having an assessment using each of the channels in detail

- why customers perceived their assessment as being easier or more difficult than expected

- how the assessment experience influenced perceptions of channel suitability

- how the assessment influenced future channel preferences

- channel perceptions and preferences

- whether claimants saw the different assessment channels as fulfilling different roles

- what role the claimant’s personal context and benefit claim had in determining channel preferences

- what role changes to how other types of appointment are delivered had on attitudes towards choice of channel for these assessments

- how claimants balance speed of assessment or choice of assessment channel

- channel choice

- why some customers requested to change assessment channel

- why customers want a choice of assessment channel and how this may shape attitudes towards the assessment

- how being offered a choice of assessment channel could affect customers

3.3. Research design

A mixed methodology was used for this research, comprised of a quantitative survey and follow up in-depth qualitative interviews.

3.3.1. Quantitative survey

A stratified random sample of claimants who attended an initial health assessment between June 2022 and January 2023 was chosen for the survey. The sample was stratified by assessment type and channel to ensure inferences could be made about these subgroups in the wider population. Those for whom DWP held an email address were sent an email inviting them to take part in the survey online. Those for whom DWP held only a postal address were sent a letter inviting them to take part in the survey online. Both communications set out the different ways in which participants could take part in the survey if an online survey was not suitable or accessible for them. Participants who did not reply to the invitations to take part in the survey and did not ask to be removed from the research were contacted over the telephone to complete the survey.

A stratified sampling approach was used to ensure that there were sufficient sample sizes amongst each of the different benefit types for sub-group analysis and to allow for analysis at the total population level. Weighting was used to achieve a sample profile representative of the different benefit types at the total level and the age and gender profile for each benefit.

The quantitative survey achieved 7,262 responses completed either online or over the telephone between 3 March and 1 May 2023. The following numbers of responses were achieved with each benefit type:

- 4,370 Personal Independence Payment claimants

- 2,153 Universal Credit claimants

- 739 Employment and Support Allowance claimants

Full details of the sampling and weighting approach are in Appendix A.

3.3.2. Qualitative interviews

Ipsos conducted follow-up in-depth interviews with 60 purposively selected survey participants who had completed the quantitative survey. This comprised:

- 30 Personal Independence Payment claimants

- 15 Universal Credit claimants

- 15 Employment and Support Allowance claimants

Interviews were held either online (using MS Teams) or over the telephone. All interviews took place between 13th July – 17th August 2023 and lasted up to 45 minutes.

Full details of the achieved sample are in Appendix B.

3.3.3. Analysis and interpretation of the data

The survey data was weighted by gender, age and benefit type based on DWP data on the trial population. Only findings from the survey which are statistically significant at the 95% confidence level have been reported in the commentary (although charts and tables may include non-statistically significant differences). All tables and charts report weighted data but include the unweighted base.

The final data from the survey is based on a weighted subset of the Health Assessment Channels Trial population, rather than the entire population. Percentage results are therefore subject to margins of error which vary with the size of the sample and the percentage figure concerned. Where figures do not add to 100 per cent, this is due to rounding or because the question allows for more than one response. Where base sizes are less than 100, percentages have not been reported and findings should be treated with caution. All quantitative findings are aggregated, and no individual participant can be identified.

Qualitative research is detailed and exploratory. It offers insights into people’s opinions, feelings and behaviours. All participant data presented should be treated as the opinions and views of the individuals interviewed. Quotations from the qualitative research have been included to provide rich, detailed accounts, as given by participants. The qualitative interviews were follow up interviews with those who had completed the quantitative survey and given consent for Ipsos to contact them again for this purpose.

Qualitative research is not intended to provide quantifiable conclusions from a statistically representative sample. Owing to the sample size and the purposive nature with which it was drawn, qualitative findings cannot be considered representative of the views of the trial population as a whole. Instead, this research was designed to explore the breadth of views and experiences to develop a deeper understanding of the experiences of having a health assessment during the trial period.

3.3.4. Reporting notes

In this report, ‘participant’ is used to refer to DWP customers who had an initial health assessment as part of their PIP, ESA or UC claim during the trial period and completed the survey and / or took part in a qualitative interview. In some cases, an appointee responded to the survey or qualitative interview on behalf of the claimant.

4. Information about the assessment and channel change

This chapter presents findings about where participants recalled receiving information about their assessment from, what they recalled about these communications and how easy or difficult they were to understand. It goes on to cover participant understanding of their ability to change their assessment channel and motivations and behaviours in relation to doing so.

4.1. Information about assessment

4.1.1. Overall source of information

Over nine in ten (93%) recalled receiving information about their assessment prior to it taking place. DWP was the most commonly recalled source of information (37%) and a quarter had received information from friends and family (26%). As shown in Figure 4.1.1, one in ten recalled receiving information from their work coach (12%), the assessment provider (11%), or a charity (10%). Social media (8%), the UC journal (8%), and local authorities (5%) were less commonly used sources of information. A small percent of participants (4%) did not recall receiving any information about the assessment.

Participants who had a face-to-face assessment were more likely to recall receiving information from DWP (43%) than those whose assessments took place over a video (41%) or telephone call (39%). Participants who had a telephone or video assessment were more likely to remember receiving information from friends and family (27% and 26% respectively) than those who had face-to-face (23%) assessments.

Younger participants (aged 18 to 24) were more likely than the total population to turn to friends and family for information (39%, compared to 26% overall).

Figure 4.1.1 Sources of information participants recalled receiving information about the assessment from

| Source | Percentage |

|---|---|

| DWP | 37% |

| Friends and family | 26% |

| Other | 20% |

| Work Coach | 12% |

| Assessment provider | 11% |

| Charity | 10% |

| Social media | 8% |

| UC Journal | 8% |

| Local authority | 5% |

| Didn’t get information about the assessment | 4% |

| Don’t know | 3% |

B3. Before your assessment where did you/they get information about it from?

Base: All respondents (7,262). Percentages do not sum to 100% as claimants may have received information from multiple sources.

4.1.2. Information provided

Participants who received information or advice from DWP or the assessment provider commonly said that the advice they received related to the logistics of attending the assessment. Around two thirds said they had received information about how the assessment would be held (65%), how long the assessment would last (64%), how long the process takes from start to finish (62%) and what the overall assessment process involved (62%). This is shown in figure 4.1.2.

Figure 4.1.2 Information provided by the DWP / assessment provider

| Information | Percentage |

|---|---|

| How the assessment would be held | 65% |

| How long the assessment will last | 64% |

| How long assessment process takes from application to receiving decision | 62% |

| What the overall assessment process involves | 62% |

| How you would be informed about the decision after assessment | 61% |

B4. What type of information or advice did you/they get from DWP or the assessment provider?

Base: All those who received information from DWP/the assessment provider (2,984)

As shown in Figure 4.1.3, eight in ten (81%) participants who received information or advice from DWP or the assessment provider reported that they found this information clear. However, around a sixth said the information or advice provided was unclear (17%).

Over eight in ten participants found the information provided by DWP or the assessment provider very (38%) or fairly (43%) clear. Fewer than two in ten participants found the information not very (13%) or not at all (4%) clear. There were no differences in perceived clarity of information by assessment channel. There were differences by benefit type. ESA and UC claimants were more likely than PIP claimants to have found the information clear (84% and 82% respectively, compared to 79%, see Figure 4.1.4).

Figure 4.1.3 Clarity of information provided by the DWP / assessment provider about the assessment process

| Clarity | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Not at all clear | 4% |

| Not very clear | 13% |

| Fairly clear | 43% |

| Very clear | 38% |

B5. How clear or not was the information you/ they got from DWP/ the assessment provider about the assessment process? Base: All those who received information from DWP/the assessment provider (2,984)

Figure 4.1.4 Clarity of information provided by the DWP / assessment provider about the assessment process by benefit claimed

| Benefit | Not at all clear % | Not very clear % | Fairly clear % | Very clear % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PIP | 4% | 15% | 44% | 35% |

| ESA | 3% | 11% | 43% | 41% |

| UC | 5% | 10% | 40% | 42% |

B5. How clear or not was the information you/ they got from DWP/ the assessment provider about the assessment process? Base: All those who received information from DWP/the assessment provider (2,984)

In the qualitative interviews participants felt that the advance information they received gave them the practical and logistical details they needed to attend the assessment. Those who had an in-person assessment recalled information about the time and date of the appointment, and address of the assessment centre. Those who had a video call assessment recalled being sent the link to join the assessment appointment and how to check that they could log on to the online session. Those who had a telephone call had received information that someone would call and when. In addition to this practical information, participants would have welcomed more information about the types of questions which would be asked. Participants felt that this would have helped them prepare for the content of the assessment and help to mitigate any worry they felt before attending. Participants acting as an appointee for a claimant were also likely to feel that the claimant would have benefitted from being able to prepare for the content of the assessment.

Female, 45 to 54, PIP, In-person assessment, said:

The leaflet was useful - instructions around the time, the location and that the meeting was to understand how my illness affected me, directions and that you could claim for travel expenses.

Participants in the qualitative interviews, across all assessment channels, who had received a text message reminder of their appointment time identified that this had been particularly useful.

Male, 18 to 24, ESA, Telephone assessment, said:

And two days before, I got a text reminder. I think that’s really good, I’d give the system 9/10. That definitely made me feel more comfortable, it allows for the fact you might have forgotten about it.

Female, 35 to 44, UC, Video call assessment, said:

I also got confirmation in the post and reminders by text. That was brilliant, very useful.

Participants who discussed their assessment with someone before having it spoke about the practicalities of attending, the assessment channel (for video assessments only) and the emotional impact of the assessment. Participants were particularly likely to have discussed the practicalities of attending if they needed support to attend their assessment channel. For example, those attending a face-to-face assessment discussed travel arrangements, such as getting a lift or arranging a taxi. Those having a video assessment who needed support with logging on had discussed this. Participants who did not have someone who supported them and wanted additional information before the assessment went to GOV.UK.

Female, 55-64. ESA, In-person assessment, said:

Did discuss with my family, as I needed someone to take me and just be around after…. [I] didn’t need anyone in the room with me though, as I would feel judged.

Male, 45-54, UC, Video call assessment, said:

Spoke to dad about it, and he helped out, we logged in [to the assessment link] about 20 mins before to ensure it was all working.

For video assessments specifically, participants whose family or friends had recently attended a health assessment discussed having their assessment using this new channel, which they had not been aware of before.

Beyond the practicalities of attending, participants discussed the emotional impact of the assessment. The health assessment was a significant event for participants which could lead to feelings of anxiety. Those who were claiming because of a mental health condition were particularly likely to feel anxious about attending the assessment. As identified above, more information on the content of the assessment, such as the questions which would be asked was seen to be helpful in mitigating this anxiety.

Female, 45-54, PIP, In-person assessment, said:

I discussed it with my fiancé because I’m not very good at expressing myself in words, I’m very emotional and have severe anxiety, so [I] was worried about leaving the house and very anxious about the upcoming assessment.

4.2. Channel change

Claimants having a health assessment can request to change their assessment channel. In the quantitative survey, three quarters of assessments were conducted over the telephone (76%), 13% face-to-face and 10% over a video call. Two per cent of participants said they didn’t know which assessment channel was used.

4.2.1. Awareness of channel change

A quarter (25%) of participants were aware that they could change their assessment channel. Overall, 12% had their assessment using a different channel from the one they were originally offered, including those whose assessment channel was changed by the assessment provider.

Excluding those who said their assessment was changed by DWP or the assessment provider, around half who changed their assessment had originally been offered an in-person assessment (48%), a similar proportion had been offered a video call (45%) and 7% a telephone assessment. Nearly all (90%) of those who changed assessment channel changed to a telephone assessment.

UC claimants (15%) were most likely to have had a different assessment type from that originally offered, followed by ESA (12%) and PIP claimants (11%).

Awareness of the ability to change channel was highest among older participants, with 30% of those aged 65 or over saying they knew this was the case. Just over two in five (22%) of 25 to 34 year olds were aware they could request an alternative assessment channel.

In the qualitative interviews, awareness of the ability to change channel varied widely. No clear patterns in awareness of this were identified.

4.2.2. Process of changing assessment channel

Overall, seven in ten (71%) participants who changed their assessment channel reported the process of doing so was easy (this excludes those who said that DWP or the assessor changed their assessment channel). As shown in Figure 4.2.1, over four in ten (45%) said the process of changing the assessment channel was very easy and around a quarter (26%) fairly easy.

Figure 4.2.1 Ease of changing assessment channel

| Ease | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Very difficult | 6% |

| Fairly difficult | 6% |

| Fairly easy | 26% |

| Very easy | 45% |

C5. How easy or difficult was it for you/them to change the type of assessment you/they had? Base: All who changed assessment channel (829)

As shown in Figure 4.2.2, participants who had a telephone assessment were most likely to have found changing assessment channel easy. Three quarters (73%) found it very or fairly easy. Around six in ten of those who had a video assessment (62%) or in-person assessment (59%) found it easy to change assessment channel.

Figure 4.2.2 Ease of changing assessment channel by channel attended

| Channel | Very difficult % | Fairly difficult % | Fairly easy % | Very easy % | Very/Fairly easy % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In person | 12% | 16% | 28% | 31% | 59% |

| Telephone | 6% | 5% | 26% | 47% | 73% |

| Video call | 9% | 9% | 30% | 32% | 62% |

C5. How easy or difficult was it for you/them to change the type of assessment you/they had? Base: All who changed the type of assessment (829)

ESA claimants found the process of changing their assessment channel easier than other benefit claimant types. Fifty-six percent of ESA claimants said they found the process ‘very easy’, compared to 46% of UC claimants and 42% of PIP claimants. See Figure 4.2.3. Older participants were more likely to find the process of changing their assessment channel easier, with 48% of those aged 55 and over saying they found the process ‘very easy’.

Figure 4.2.3 Ease of changing assessment type by benefit claimed

| Benefit | Very difficult % | Fairly difficult % | Fairly easy % | Very easy % | Very/Fairly easy % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PIP | 7% | 6% | 28% | 42% | 70% |

| ESA | 4% | 5% | 23% | 56% | 79% |

| UC | 5% | 6% | 24% | 46% | 70% |

C5. How easy or difficult was it for you/them to change the type of assessment you/they had? Base: All who changed the type of assessment (829)

4.2.3. Reason for changing assessment channel

The two most common reasons why participants had an assessment using a different channel than originally offered were a) the channel was changed by the assessment provider (23%),or b) the participant did not feel able to attend using the original channel because of their health condition (22%). Other reasons included being anxious about completing the assessment in that way (15%), technical issues (14%) or being unable to travel to the assessment centre (11%).

ESA claimants (32%) were most likely to change their assessment type because of their health condition. This applied to around a quarter (23%) of PIP and just under one in five (18%) of UC claimants. Findings from the qualitative interviews reinforced the survey findings. Participants who changed their assessment channel did so for reasons related to their ability to attend that channel rather than simply preference.

Participants said they requested a change of assessment channel if they could not attend the original channel they were allocated, for example, they were unable to travel to the appointment or join an online video assessment. In the qualitative sample, no participants who were allocated a telephone assessment requested to change their assessment channel. As such, participants in this position requested to change channel, regardless of whether they knew or recalled being told that they could. Participants who were aware of the possibility of changing their assessment channel did so out of necessity rather that preference. If they were able to attend using their originally allocated channel, they did so.

Male, 55-64, PIP, Video call assessment, said:

I didn’t know how to use the technology to do a video call and didn’t have any technology, [computer or iPad or smart phone] so wouldn’t know where to start to have an online call. So [I] phoned the number on the letter and changed it to a phone call which was not difficult.

Qualitative research participants who had a poor preconception of DWP, and recalled information about being able to change assessment channel, did not always think that this offer was genuine. They believed that the offer of being able to change assessment channel was to identify ‘troublemakers’.

Male, 25-34, Universal Credit, Video call assessment, said:

I think it probably makes them [assessor] more hostile if you ask to change [assessment channel].

5. Participant perceptions before the assessment

This chapter discusses participants’ initial awareness of the assessment process, awareness of the different assessment channels available and expectations and attitudes towards the assessment.

5.1. Awareness of the assessment process

5.1.1. Awareness of the need to have an assessment

Before receiving the invitation to the assessment, participants were more likely to be aware that they might need to have an assessment than why or what would happen. Nearly nine in ten participants were aware that they might need to have an assessment (86%), compared to eight in ten (80%) who knew why they might need to have one, and nearly seven in ten (67%) who knew what might happen.

As shown in Figure 5.1.1, awareness of the need to have an assessment was higher among PIP claimants (89%) than ESA (81%) or UC (82%) claimants. PIP claimants were also more aware of the purpose of the assessment (81%) than ESA (76%) and UC (79%) claimants.

Participants were less likely to feel well informed about what would happen at their assessment. Two in three (67%) reported being aware of what happens; this was again higher for PIP claimants (69%) than ESA (61%) or UC (64%) claimants, and higher for female participants (70% compared to 63% of males).

Figure 5.1.1 Awareness of needing an assessment, why they need an assessment, and what happens at the assessment by benefit claimed

| Benefit | That you/the person you are claiming for might need to have an assessment % |

|---|---|

| PIP | 89% |

| ESA | 81% |

| UC | 82% |

| Benefit | Why you/the person you are claiming for might need to have an assessment % |

|---|---|

| PIP | 81% |

| ESA | 76% |

| UC | 79% |

| Benefit | What happens at an assessment % |

|---|---|

| PIP | 69% |

| ESA | 61% |

| UC | 64% |

B1A. Before you/they received an invitation to the assessment were you/they aware… %Yes Base: All respondents (7,262)

5.1.2. Awareness of the assessment channels

The majority of trial participants (83%) were aware that the assessment could be conducted over the telephone, and three quarters (75%) were aware that it could be held in-person. Fewer (56%) were aware that assessments could be held over a video call.

PIP claimants were more likely than ESA and UC claimants to know that the assessment could be conducted over the telephone. 85% of PIP claimants were aware that the assessment could be held over the telephone, compared to 79% of ESA and 78% of UC claimants. This is shown in Figure 5.1.2

Figure 5.1.2 Awareness of the channels available to conduct the assessment by benefit claimed

| Benefit | That the assessment may be held in person % |

|---|---|

| PIP | 76% |

| ESA | 71% |

| UC | 74% |

| Benefit | That the assessment may be held on the telephone % |

|---|---|

| PIP | 85% |

| ESA | 79% |

| UC | 78% |

| Benefit | That the assessment may be held on a video call % |

|---|---|

| PIP | 85% |

| ESA | 79% |

| UC | 78% |

B1A. Before you/they received an invitation to the assessment were you/they aware… %Yes

Base: All respondents (7,262)

5.2. Perceptions of assessment channels

5.2.1. Impact of channel on claim behaviour

Participants who were aware that the assessment could be carried out using each of the assessment channels were asked what impact, if any, this channel had on their likelihood of making a claim. Figure 5.2.1 shows that for around six in ten, knowledge of the different assessment channels available to them had no impact on their likelihood of applying.

Overall, knowing the assessment may be held in-person had the biggest impact on the likelihood of applying for a benefit. Whilst 61% said it would make no difference, 19% of participants said it would make them more likely to apply for the benefit and 16% said this made them less likely to apply.

Figure 5.2.1 Impact of awareness of assessment channels on likelihood of making a benefit claim

| Channel | Much less likely % | Little less likely % | Makes no difference % | Little more likely % | Much more likely % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowing assessment may be on a video call | 5% | 7% | 62% | 7% | 16% |

| Knowing assessment may be on the telephone | 4% | 4% | 60% | 9% | 20% |

| Knowing assessment may be in person | 7% | 9% | 61% | 6% | 14% |

B2. What impact did the following have on your/ their likelihood to apply for [Benefit]? Base: All respondents who were aware of each assessment channel (video: 4,127, telephone: 5,877, in-person: 5,493)

A greater proportion of people claiming PIP (17%) said that the assessment being conducted in-person made them less likely to apply than those claiming ESA (10%) or UC (14%).

Younger participants were most likely to say that having a face-to-face assessment would make them less likely to apply. About three in ten (31%) of those aged 18 to 24 and 25% of those in the 25 to 34 age group said that a face-to-face assessment would mean they were less likely to apply, compared to 4% of participants aged 65 or more. Similarly, people with psychiatric disorders (26%), anxiety and/or depression (21%) or any sensory disability or health condition (also 20%) were less likely to apply if this required attending an in-person assessment. In the qualitative research, these groups were more likely to find an in-person assessment difficult to attend.

Telephone assessments were considered the most accessible channel. Nearly three in ten (29%) said this made them more likely to apply for the benefit (60% no difference, 8% less likely). This was particularly the case for the groups who with psychiatric disorders (35%), anxiety/depression (32%), and younger participants (37% of 18 to 24s and 35% of 25 to 34s).

Around a quarter (23%) said that knowing they could have a video assessment made them more likely to apply. To 62% it made no difference. 12% said it made them less likely to apply. Differences by condition, disability, or age were less marked for this channel.

5.2.2. Expectations of the assessment channel

Participants were asked about their expectations of having an assessment using the channel using which their assessment was conducted. Prior to the assessment, over half of participants felt that the assessor would be able to assess their condition very or fairly well using the assessment channel their assessment was conducted using. However, a substantial minority expressed doubts about this. This was particularly the case for telephone and video calls (38% in each case). Fewer participants (28%) expressed concern about the accuracy of face-to-face assessments (Figure 5.2.2).

Figure 5.2.2 Confidence in the assessor’s abilities to assess their condition or disability accurately

| Channel | Don’t know % | Not at all well % | Not very well % | Fairly well % | Very well % | Very/Fairly easy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In person | 8% | 16% | 22% | 32% | 22% | 54% |

| Telephone | 13% | 11% | 17% | 31% | 27% | 58% |

| Video call | 8% | 17% | 21% | 34% | 20% | 54% |

C8. Before you/they had the assessment, how accurately did you/they think the assessor would be able to assess your/their health condition or disability?. Base: Respondents whose assessment was conducted via each channel (Telephone 4,904; In-person 1,163; Video call 1,105).

Across all channels, PIP claimants were least confident that the assessor would be able to accurately assess their condition. Overall, half of PIP claimants (50%) thought the assessor would be able to assess their condition very or fairly well using their assessment channel, whilst 43% believed they would not. Comparatively, ESA and UC claimants were more confident that the assessor would be able to assess their condition very or fairly well (64% and 61% respectively), and fewer thought this would be not very well or at all well (28% and 27% respectively).

5.2.3. Attitudes towards the assessment

In the qualitative interviews, participants described how the assessment was a significant experience for them. Participants’ attitudes towards the assessment before having it related to how they felt about their condition and making a benefit claim. In our sample, there were three broad attitudes to the benefit claim and the assessment:

- reluctance to claim benefits

- discomfort discussing their health condition

- high confidence in being awarded benefits

These attitudes fed into anxiety about the assessment either because of the uncertainty it caused, discomfort discussing their condition and/or importance of receiving an award.

Participants who were reluctant to claim described feeling like a failure or guilty for needing to claim benefits. These claimants usually had an extensive work history and described feeling that others were in greater need than them and should be prioritised above them. Seeing themselves as less deserving of a benefit award, this group demonstrated uncertainty about whether they would receive one. There were examples of participants in this group who said others had recommended they claim benefits, rather than claiming proactively. Some in this group demonstrated attitudes which suggested they saw claiming benefits as being stigmatised. Participants who were unwilling to claim or embarrassed about doing so worried about feeling judged by the assessor.

Female, 35 to 44, UC, In-person assessment, said:

I thought they [assessor] were there to punish me, because I’m not working, and to have a go at me because I’m not working.

Participants who felt uncomfortable discussing their health condition were either uncomfortable acknowledging the impact of their health condition(s) or found it difficult to talk about their condition and their need to claim. For example, one male claimant who was claiming PIP because of the effects of Multiple Sclerosis felt uncomfortable talking about this.

Male, 45 to 54, PIP, Video call assessment, said:

Maybe it’s a male pride thing…and the [assessor] was female and younger…When asked questions like how far I can walk without crutches. I double the length that I could actually walk… Speaking to a young girl…I was embarrassed to reveal that I can’t walk far…MS can also lead to bladder control issues. Now it’s really hard to say that to a stranger when you can see their face.

A claimant whose health conditions had been caused by being physically attacked also experienced Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). He found it very difficult to discuss how his health conditions affected him because this brought back traumatic memories of when he had been attacked. This group also included those whose parents were acting as their appointee. In these cases, the appointee described the difficulty the claimant had in attending appointments and assessments. For example, one parent who was an appointee for her son reported that he become distracted and agitated during the assessment so had to leave.

Those who were confident that they would receive a benefit award were more likely to know someone else who was claiming PIP, ESA or in the UC LCW or LCWRA conditionality group. This led them to feel confident about their likelihood of receiving an award, as they compared their experiences to those of their friend or family member. There were also people in this group who had done research online into what the criteria for receiving a PIP award are, and felt they met them. As a result, they strongly believed they would receive an award. These participants felt that receiving an award would validate the extent to which their health condition affected them.

Attitudes towards, and anxiety about, the assessment intersected with assessment channel for some types of claimants. For example, those with some mental health conditions, such as anxiety, were more likely to prefer a telephone assessment to an in-person or video assessment. These participants felt that attending an in-person assessment, which would mean travelling and being around people they didn’t know, could exacerbate their condition. Some participants with these types of conditions also found taking part in a video assessment difficult for similar reasons. Participants with physical health conditions were also likely to find attending an in-person assessment difficult. They expressed concern about the practicalities of attending and the potential impact on their health. Participants who lacked digital confidence wanted support with attending the assessment and were more likely to prepare for this in advance, or get support, than more digitally confident participants. Attitudes towards the assessment channel intersected with previous experiences with DWP and subsequent expectations of what the interaction would be like. Participants who had neutral attitudes tended to have had little experience of the benefits system and no or few preconceptions. In contrast, those who had negative attitudes had heard negative stories about engaging with DWP, either through word of mouth or in the press. They believed that the assessor would be biased against giving them an award. There was no relationship between the assessment channel the participant attended and pre-existing attitudes towards DWP.

6. The assessment experience

This chapter covers participant’s overall experience of having a health assessment including the practical elements of preparing for the assessment and their thoughts and feelings during the assessment. This chapter also outlines the findings from Key Drivers Analysis to identify the factors which underpin agreement that the assessor understood their health condition or disability.

6.1. Preparation on the day of the assessment

When participants recalled how they felt on the day of their assessment, the majority felt satisfied that they had the information they needed to attend their assessment. Nine in ten (90%) agreed the appointment time was convenient and 92% that they were informed of this time early enough to give them time to prepare. Participants were less likely (75%) to agree that they knew who to contact if they had questions or needed to rearrange the appointment.

As shown in Figure 6.1, of those who attended an in-person assessment, two thirds (67%) agreed this was in a location they could get to easily; three in ten (31%) disagreed.

Figure 6.1 Perceptions before the assessment

| Perception | Strongly disagree % | Tend to disagree % | Tend to agree % | Strongly agree % | Don’t know % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The apppointment time I was offered was convenient for me/them | 3% | 4% | 34% | 57% | 3% |

| Informed of the assessment time in enough time to make preparations | 3% | 3% | 29% | 62% | 3% |

| I/they knew who to contact to ask questions or rearrange appointments | 9% | 9% | 22% | 53% | 7% |

| DWP made it clear that it is allowed to bring someone to the assessment | 9% | 9% | 22% | 53% | 7% |

| The face-to-face assessment was in a location that I/they could get to easily | 17% | 15% | 26% | 42% | 1% |

C9. To what extent do you agree or disagree with each of the following statements…? Base: Statements _1 to _4 all respondents (7,262); statement 5 all who were invited to an in-person assessment (1,163)

In the qualitative interviews, participants discussed making both general and channel specific preparations for their assessments. Across all channel and benefit types it was clear that the assessment was a significant event for participants. They placed great importance on arriving at or joining the assessment on time. This meant planning how they would attend and, for those joining remote sessions, making sure they were undisturbed. Participants wanted to be able to answer the assessor’s questions in detail. Reflecting this, almost all discussed ensuring that they had their medication and/or medical documents with them for the assessment. Participants who had an in-person assessment discussed organising transport and looking into travel routes and timings to the assessment centre. This included booking taxis, checking public transport routes or arranging a lift.

Those with lower digital confidence were likely to prepare in advance for a video call. This group discussed setting up their laptop or tablet before the assessment and testing joining the call. In some cases, this included getting support from a friend or family member to give the participant confidence that they would be able to join on time and reduce the risk of technical difficulties. Those with high digital confidence did not feel the need to prepare as they knew how to use the video call application and were confident they could join the call successfully.

Those who had a telephone assessment were least likely to describe making specific preparations, although one participant described changing their shift at work to ensure they were in a quiet area to receive the call.

6.2. Concerns on the day of the assessment

Across all benefit types and assessment channels, 6 in ten (60%) participants said they had been either very or fairly concerned about attending the assessment on the day.

Participants who attended an in-person assessment were most likely to have been concerned about it in advance (68%). Those who had a video (60%) or telephone (59%) assessment were equally likely to have been concerned about this.

People claiming ESA were less likely to feel concerned on the day than those claiming PIP or UC. Half (50%) reported feeling concerned, compared to around 6 in ten PIP (61%) or UC (62%) claimants.

Concern was higher among younger participants. Two thirds (66%) of those aged 18-24 reported feeling concerned about attending the assessment on the day compared to 44% of those aged 65 or over. Levels of concern were higher than average among participants with a psychiatric disorder (76%), anxiety/depression (68%) or a sensory disability or condition (67%).

Two fifths (41%) of participants with a psychiatric disorder thought the assessor would not be able to assess their health condition accurately, followed by 39% of those with a sensory disability or 38% of participants with anxiety and depression.

6.3. Participants who had a companion for the assessment

Participants were allowed to bring someone else to the assessment with them if they wanted to. Three quarters (75%) were aware of this, although 18% disagreed that DWP had made it clear that they could do this and 7% were not sure.

Overall, nearly three in ten (27%) participants took someone with them to their assessment. Those who had a face-to-face assessment were most likely to take a companion with them to the assessment (45%), compared to 31% for video and 24% for telephone assessments.

PIP claimants (29%) were more likely to have taken someone with them to the assessment than UC claimants (26%), who were in turn more likely to have done so than ESA claimants (20%).

Taking a companion was most common among those with sensory disabilities or conditions (34%) or psychiatric disorders (33%), and participants under the age of 25 (48%).

Figure 6.3 shows the proportion of participants who took someone with them into the assessment, by benefit type and channel.

Figure 6.3 Proportion of participants who had a companion for the assessment

| Assessment | Percentage |

|---|---|

| PIP – Telephone | 26% |

| PIP – In person | 50% |

| PIP – Video call | 32% |

| ESA – Telephone | 17% |

| ESA – In person | 35% |

| ESA – Video call* | 21% |

| UC – Telephone | 22% |

| UC – In person | 42% |

| UC – Video call | 28% |

C13. Did you/they take anyone into the assessment room/ask someone to join the telephone assessment/ask someone to join the video call with you/them? %Yes Base: All respondents (7,262) *Caution small base (90)

The most common reasons participants took a companion with them to their assessment were to support them with needs associated with their disability (69%), to provide moral support and company (58%), or help with the information needed to answer questions (52%). A third (34%) said their companion was there to answer questions on their behalf, around a quarter were there to take notes (27%) or to ask questions (24%). The qualitative interviews supported this, with participants sharing that the main reasons for taking someone with them to a face-to-face or video assessment was for either emotional or practical support.

In the qualitative interviews, experiences in the assessment depended on whether the companion was a formal appointee or not. Formal appointees reported that the way the assessor conducted the assessment reflected their formal role and that they were able to speak on behalf of the claimant. For example, one mother who was her son’s appointee reported that her son found the video assessment experience very challenging. Reflecting this, the assessor allowed the claimant to leave the assessment and for his mother, the appointee, to conclude the assessment without him present.

Participants took informal companions either to help better explain aspects of their condition to the assessor or to help them (the participant) better understand the assessor’s questions. In these cases, participants reported that informal companions were not able to respond on their behalf or that assessors could become frustrated if the companion tried to help the participant understand the questions. This came as a surprise to participants, as they had expected their companion would be able to fulfil this role. This suggests there is a need for greater clarity about the role informal companions can play during an assessment.

Female, 45 to 54, PIP, In-person assessment, said:

She [the assessor] was very abrupt and asked a lot of questions that I didn’t understand, so I kept looking at my fiancé and asking him to put them in a language that I could understand and sometimes he answered for me. I think she was getting a bit frustrated because I kept doing that.

6.4. Challenges attending the assessment

Around a third (35%) of participants reported experiencing some form of challenge attending the assessment on the day. Those who had a face-to-face assessment were most likely to report difficulties attending – over half (55%) reported at least one challenge. These were most commonly challenges related to accessing the assessment centre. Nearly a quarter (24%) of those who attended in-person reported difficulties accessing the assessment centre due to their health condition and a similar proportion (22%) had transport difficulties. In the qualitative interviews, the difficulties attending the assessment centre included having to park far away from the entrance to the assessment centre which was difficult for people with mobility difficulties; difficulty finding the assessment centre when driving; or not being able to access the assessment centre using public transport. The latter experience created a challenge to attending for those without a car.

Of those who had a video call, over four in ten (43%) reported at least one difficulty attending. The most common difficulty for this group was the assessor running late (17%). A similar proportion (15%) had difficulties using the video call technology or difficulties with their internal connection (15%). Around one in eight (12%) reported that the call was of poor quality.

Just over 3 in ten (31%) of those who had a telephone appointment reported at least one challenge attending, the lowest proportion of all channels. The most common challenge was delays to their appointment time (12%). Less than one in ten (9%) reported the call was of a poor quality, and 4% that the assessor called unexpectedly.

In total, 13% of participants reported delays to their appointment time as a challenge they experienced on the day. This was most common for face-to-face assessments (18%) or video calls (17%) and less common for telephone appointments (12%). In the qualitative interviews, participants who spoke about experiencing delays to their appointment described that this added to the anxiety they already felt about having the assessment. Those who had an in-person assessment reported having to wait in uncomfortable waiting rooms. If it was too hot or too cold this exacerbated their health condition, making the assessment harder for them.

Male, 35 to 54, PIP, said:

The waiting room was uncomfortable, and this was stressful. The assessment did not go well.

Participants who had video appointments reported waiting for up to 40 minutes for an assessor to join the video call without any communication about the delay or when their appointment would be held.

Male, 25 to 34, UC, said:

There was [sic] no tech issues, you were given a timeframe of when the appointment is but there was an additional 30-minute delay in starting…But you weren’t told why you were delayed or how long, you just sat there staring at a blank screen for the host to come on. This caused internal frustration…It is not the individual’s [assessor’s] fault and I tried not to feel antagonistic about it.

Some participants who had telephone appointments reported having to wait for up to two hours for the assessor to call.

Female, 55 to 64, UC, said:

The nurse rang me to say she was running late by one and a half hours…The hanging about then made me even more nervous, my stomach was in knots…I hate waiting, it just worked me up even more.

In all cases, delays to the assessment caused nervousness and anxiety for the participants. This seems to have been more pronounced for those having remote assessments, as they had no communication about why their appointment was delayed, when it would take place, or how to contact the assessor to find out when it would be. For nearly seven in ten (68%) participants who experienced a challenge attending their assessment, the appointment went ahead on the same day, using the original assessment channel. Less common consequences of challenges attending the assessment included the assessment being carried out through a different channel (9%) or being given a new date or time for the appointment (8%).

6.5. Interactions with assessor

Findings from both the quantitative and qualitative strands found that a participant’s interaction with their assessor determined how well they felt the assessor had understood their condition. This was the case across all assessment channels.

The quantitative survey found that participant’s ratings of the way the assessor communicated with them during the assessment were generally positive, as shown in Figure 6.5. In total, nearly nine in ten (89%) participants agreed the assessor treated them with respect and dignity throughout, and the same proportion that the assessor had explained what their role was in the assessment. The majority (86%) agreed the assessor had explained the assessment purpose and structure before starting.

Most participants were positive about their understanding of what they were being asked to do (82%). Of those who had a face-to-face or video assessment, fewer (54%) agreed that the measurements and functional tests that were carried out were relevant and appropriate. This question was not asked of those who had a telephone assessment as these activities are not included in telephone assessments.

Eight in ten (80%) said their communication and language needs were considered. Just over three quarters (76%) agreed they felt listened to during the assessment, and a similar proportion (75%) that they had enough time to explain how their condition affects them.

Three quarters (74%) agreed that the questions asked by the assessor were relevant and appropriate and a similar proportion (71%) agree they allowed the participant to fully explain the impact of their condition on their ability to work or their day-to-day life. Seven in ten (70%) said the assessor had understood their application form and supporting evidence.

Figure 6.5 Perceptions of the assessment experience

| Perception | Strongly agree % | Tend to agree % |

|---|---|---|

| The assessor treated me/them with respect and dignity during the assessment | 66% | 23% |

| The assessor explained what his/her role was | 59% | 30% |

| The assessor explained the purpose and structure of the assessment before starting | 57% | 29% |

| I/they understood what I/they were being asked about being asked to do | 50% | 32% |

| My/their communication and language needs were considered | 52% | 28% |

| I/they felt listened to during the assessment | 52% | 24% |

| I/they had enough time during the assessment to explain how my/their condition affects me/them | 50% | 25% |

| Questions were relevant and appropriate to my/their condition | 46% | 25% |

| Assessor had understood application form and supporting evidence | 47% | 23% |

| Relevant and appropriate measurements and functional tests were carried out | 35% | 19% |

C15. Please tell me to what extent you agree or disagree with each of the following statements about the assessment? Base: All respondents (7262) except “Relevant and appropriate measurements” statement: Respondents who had received an in-person or video call assessment (924)

Experiences were consistent across telephone, in-person and video call assessments.

Differences in attitudes were present amongst claimants of different benefit types. PIP claimants were less positive and were less likely to agree that:

- the assessor explained their role (88%, compared to 91% of ESA claimants and 90% UC)

- the assessor treated them with dignity and respect (87% compared to 93% of ESA claimants and 92% UC)

- they felt listened to during the assessment (71% compared to 85% of ESA claimants and 83% UC)

- their communication and language needs were taken into consideration (77%, compared to 85% of ESA claimants and 84% UC)

- the assessor understood their application form and other evidence (65%, compared to 79% of both ESA and UC claimants)

- they were asked relevant and appropriate questions (69%, compared to 82% of both ESA and UC claimants)

- the questions asked allowed them to explain the impact of their condition (66%, compared to 80% of ESA claimants and 79% UC)

- they had enough time to explain how their condition affects them (70%, compared to 84% of ESA claimants and 83% UC)

- they understood what was being asked of them (80%, compared to 90% of ESA claimants and 85% UC).

6.6. Assessors’ understanding of how the participants’ condition affected their daily life or ability to work

Participants were asked the extent to which they agreed that they were able to explain how their condition affects their daily life or ability to work, depending on the benefit they had an assessment for, and that the assessor understood this. PIP claimants were asked in relation to how their condition affected their day-to-day life and ESA and UC claimants in relation to their ability to work, reflecting the purpose of the different benefit types. This perception underpins the perceived efficacy, and therefore legitimacy, of the assessment.

Overall, around two-thirds of participants (68%) agreed they had been able to explain how their health condition affects their daily life or ability to work, and around six in ten (61%) agreed their assessor understood this. Assessment channel had no impact on the extent to which participants agreed with these statements.

Reflecting their lower positivity about the assessment experience overall, PIP claimants were less likely to agree with either statement. Around six in ten (62%) agreed they had been able to explain how their health condition affected them compared to around eight in ten ESA (80%) and UC (77%) claimants. PIP claimants were also less likely to agree that the assessor had understood the impact of their condition. Around half agreed with this (52%) compared to around three quarters of ESA (75%) claimants and UC (76%) claimants.

Figure 6.6 Agreement that the assessor understood their condition and how much it affected them

| Statement | PIP – Telephone | PIP – In person | PIP – Video call | ESA – Telephone | ESA – In person | ESA – Video call* | UC – Telephone | UC – In person | UC – Video call |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessor understood condition and how it affects daily life/ability to work % | 53% | 49% | 52% | 75% | 78% | 74% | 77% | 77% | 82% |

| How much do you agree or disagree with the following statements – I/they was able to explain how healthy condition affects daily life/ability to work % | 62% | 58% | 61% | 80% | 81% | 83% | 79% | 78% | 85% |

C25_A. How much do you agree or disagree with the following statements… Base: All respondents (7262) *Caution small base (90)

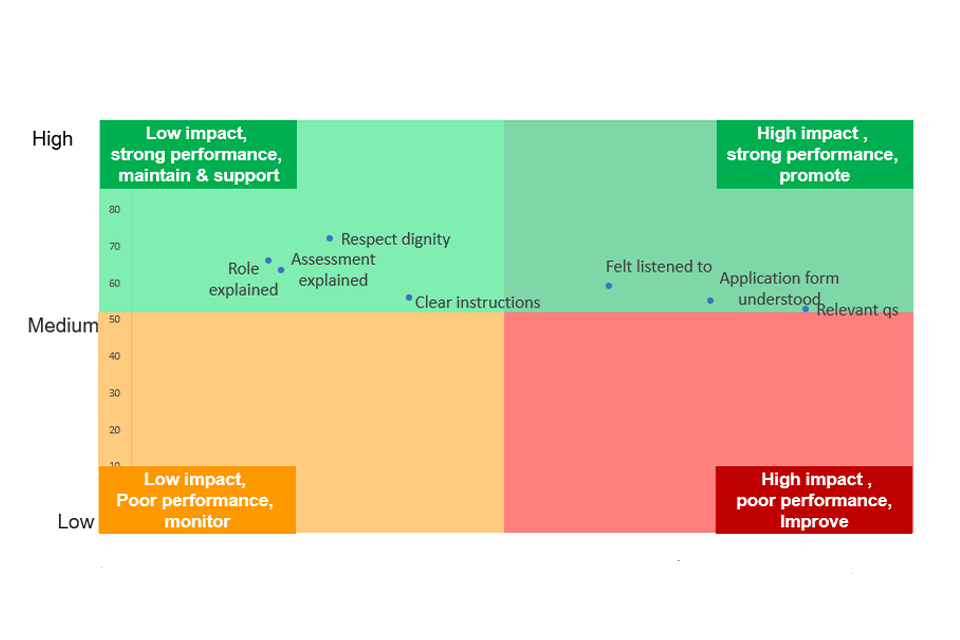

6.6.1. Factors which underpin agreement that the assessor understood the impact of their condition

Key Drivers Analysis