Evolving the regulatory approach to master trusts

Published 22 November 2023

A review of the master trusts authorisation and supervisory regime and the wider market

November 2023

Ministerial foreword

Master trusts are the engines of growth in the pensions market in the UK. By the end of the decade, master trusts could triple their assets under management in real terms. This will improve the opportunity to invest billions of pounds on behalf of their members in productive finance, including in the UK economy. And I want to encourage master trusts to continue to grow, consolidating the long tail of single-employer trusts where it is in members’ interests, so that they can reap the potential benefits through improved investment performance and lower costs that come with scale.

Master trusts are integral to our pensions system, allowing millions of members to benefit from the sorts of scale efficiencies which may otherwise be out of reach for so many employers. Following 5 years of rapid growth in master trusts, this review is conclusive in its finding that the direction of travel for this market is continued strong growth and higher concentration, thanks to a healthy competitive environment. Scheme consolidation into well-run, well governed, value for money master trusts is a driver of good pension outcomes. This brings the potential to improve opportunities for investment in the UK, which is core to the government’s commitment to making the UK the most innovative and competitive financial centre in the world.

But many of the nearly 24 million members of master trusts have been defaulted into saving for their retirement, and whether they know it or not, they bear the risk of their investments. Pension schemes are at their heart, an investments business, and net returns, along with contribution levels, are the strongest determinant of how large a defined contribution (DC) pot will be at the end of a lifetime of saving.

That is why are putting savers and value for money at the heart of our policy and regulatory framework. Moving the dial on competition in the market focussing on value not just cost, and ensuring there is effective scrutiny of scheme decision-making will help savers receive the best possible retirement outcome. However, the regulatory framework for master trusts currently focusses more narrowly on ensuring schemes are resilient to shocks, prepared for all outcomes and reporting regularly to the Regulator. The Pensions Regulator (TPR) will shift the focus of its regulatory approach and enhance the supervision of investment governance: through this we can raise standards of trusteeship, build scale and expertise to invest in a diversified range of assets, and ensure that all savers receive value for their money by default. Government will cement this value-focussed approach by taking forward legislation to introduce the value for money framework, when parliamentary time allows.

Master trusts are going to be key to the delivery of the Mansion House reforms, as well as wider policy initiatives. To ensure the success of these reforms which will improve outcomes for members, it is important that the regulatory environment reflects the evolving market. I am pleased that this report demonstrates that TPR expects to take a more influential approach to master trusts to see these objectives achieved.

Our organisations will work together to explore what further interventions may be necessary to protect members in future, where schemes are consolidating, reaching systemically important size.

This review allows us to take stock of how the master trust market has developed and identifies where we can work together and with industry to ensure that we protect, enhance, and innovate the market in savers’ interests.

Paul Maynard MP

Minister for Pensions

Introduction

Five years on from the coming into force of the Occupational Pension Schemes (Master Trusts) Regulations 2018, DWP and TPR have jointly reviewed the master trusts market; looking at market segmentation, costs, charges, consolidation, increasing scale, and the relationship with the Chancellor’s Mansion House compact and other DWP policies and policy proposals. We describe ways in which TPR is responding to this evolving market, and areas where the master trust authorisation and supervisory regime (the regime) may need to be updated, with a particular focus on investment governance and working more closely with schemes as they grow. Further evolution of TPR’s approach to supervision will also continue in the future, in line with its corporate objectives.

About this report

This review of the master trusts market and authorisation and the regime was conducted working jointly with TPR. There are actions that DWP and TPR will each take separately as a result of our findings, however we will continue to work collaboratively as these are further explored and/or taken forward. DWP has worked in partnership with TPR to understand the practical application of the regime. We have also had input from the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) which regulates FCA-authorised organisations that sponsor master trusts, to hear their unique perspective. We have also held insightful conversations with a number of master trusts, investment managers, consultancies and others, to gain a greater understanding of the market’s dynamics and pressures, from those operating within it.

Summary and context

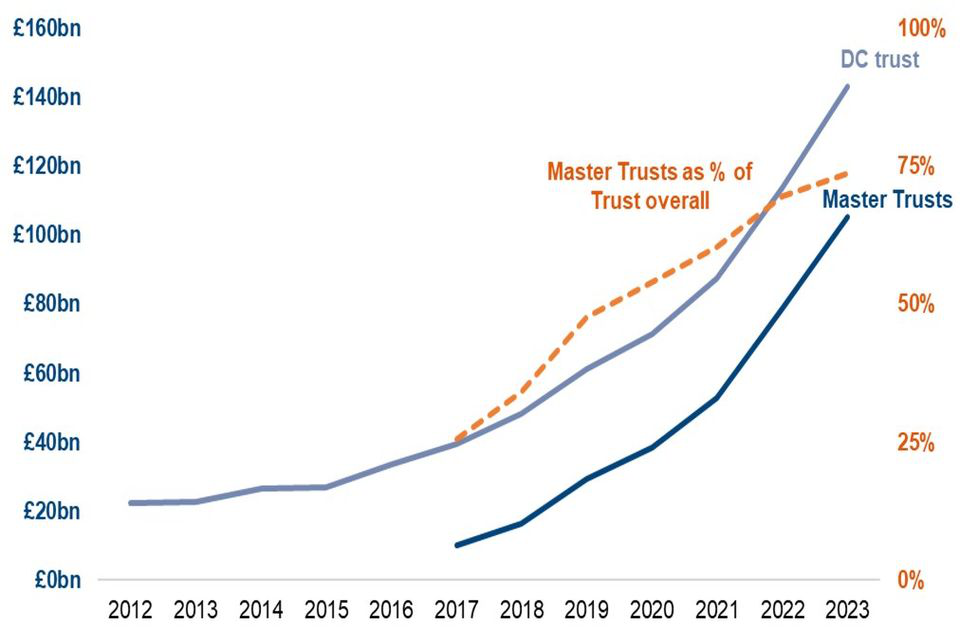

1. Master trusts are set to play a leading role in the reforms announced at Mansion House and at the Chancellor’s Autumn Statement. DWP analysis shows that the trust-market as a whole could grow from around £140 billion in 2023 to about £420 billion in 2030 in real terms[footnote 1]. This scale will open up opportunities for large schemes to become more dynamic and sophisticated in their investment strategies, and government’s hope is that this dynamism will also have positive effects for the UK economy, through long-term investment in UK based assets, where it is in pension members interests, contributing to higher growth.

2. Looking at schemes by size, this could lead to over half of trust-based DC assets being in schemes of over £50 billion, nearly two-thirds in schemes holding more than £30 billion and over three-quarters in schemes of over £20 billion[footnote 2]. The investing power of these entities in their potential to create growth should not be underestimated.

3. With the potential growth in members of these schemes, this could mean that over three-quarters of trust-based DC members could be in schemes of over £50 billion, approaching 80% of members in schemes holding more than £30 billion and over 80% in schemes of over £20 billion. Though it should be noted that these assumptions are highly volatile and dependent on future market conditions and potential policy changes.

4. And master trusts will account for a huge portion of this. Master trusts already account for 90% of DC memberships, with 82% of members concentrated in the largest 5 schemes by assets under management. And we forecast that this will continue to concentrate, particularly in larger schemes[footnote 3].

5. Master trusts[footnote 4] entered the workplace pensions market to meet the increasing need for pension provision for millions of savers following the introduction of automatic enrolment (AE) in 2012. In 2018, to combat the emerging risks arising from this scheme type, the government introduced a regulatory framework for master trusts, ensuring that only master trusts authorised by TPR were permitted to operate.

6. Since the introduction of the master trusts authorisation and the regime, master trusts have become the vehicle of choice for around 1.3 million employers[footnote 5] as they make the case that they can provide security, sophistication of strategy, good governance, low cost for employers, and reduced charges for members.

7. 5 years on, we are now anticipating a future where, alongside several smaller master trusts[footnote 6], a smaller number of very large master trusts are in operation, providing members with value for money (VFM) consistent with the joint DWP, TPR, and FCA VFM Framework. Value will be delivered in part via sophisticated investment strategies producing high-performing returns from a wide range of assets, including accessing the opportunities presented by innovation within the UK economy.

8. Many of the millions of members of master trusts have not made an active choice to save, as AE has utilised defaults to harness the power of inertia and 94% of master trust memberships are within the default investment strategy[footnote 7]. Therefore it is vital that TPR is able to continue to strike the balance of regulation and risk, and that the regime continues to provide TPR with the powers it needs to protect members and drive the best outcomes for members.

Mansion House reforms

9. Master trusts are set to play a leading role in the reforms announced at Mansion House and at the Chancellor’s Autumn Statement. The projected scale of the largest master trusts means they will be able to access a broader range of investment opportunities, including those that contribute to UK growth, benefit from cost saving opportunities that come from economies of scale and deliver new and innovative services to members in accumulation and decumulation.

10. Master trusts, with their increasing ability to consider and assess the value and understand the opportunities of a wide range of assets, are exploring these avenues: 10 organisations, 9 of which sponsor a master trust, are now signatories to the Mansion House compact, intending to achieve a minimum 5% allocation to unlisted equities[footnote 8]. The Minister for Pensions signalled her support to this at a speech at the Onward Thinktank following the announcement of the Mansion House reforms.

The Chancellor and I are united in our commitment to creating a pension market which delivers for savers, one that is boosted by investment in innovative UK businesses and a broader class of productive assets[footnote 9].

11. Some master trusts, along with group personal pensions (GPPs) are also likely to be among the default consolidators of deferred small pots[footnote 10], as described in the government response to the consultation on “Ending the proliferation of deferred small pots” as their scale allows them to keep operating costs low.

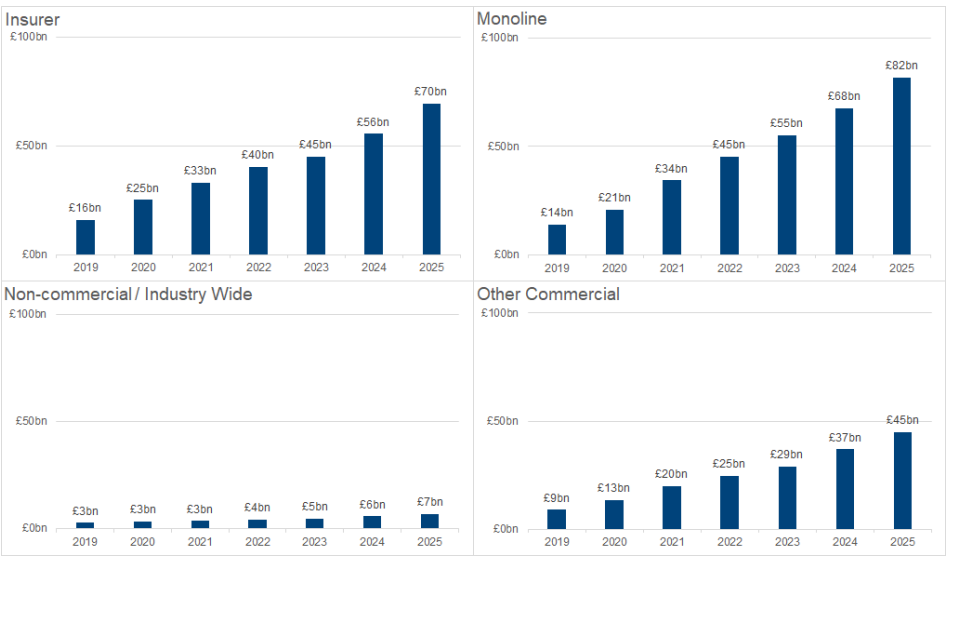

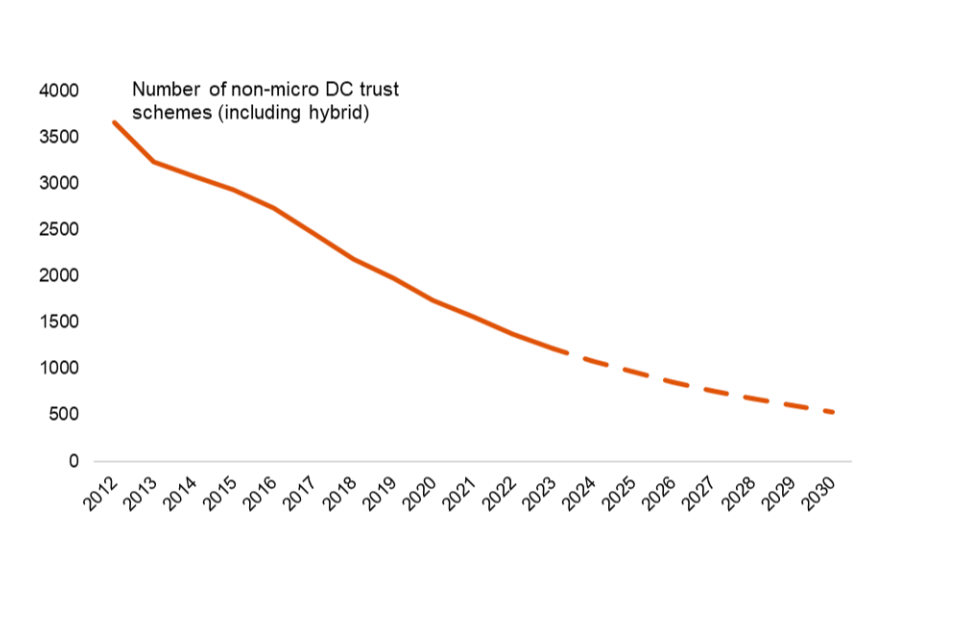

12. The Pensions (Extension of Automatic Enrolment) Act 2023, which received Royal Assent on 18 September introduced powers to lower the age criteria and lower earnings limit for AE. Monoline[footnote 11] master trusts in particular are in a position and likely to provide services to those brought into pension saving by these measures.

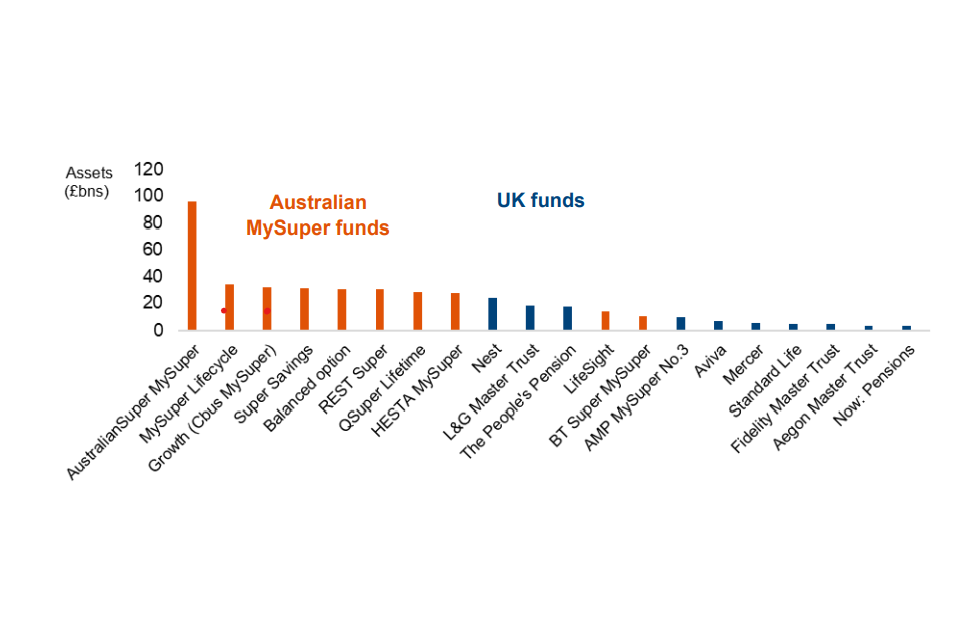

13. Master trusts will also likely be the pension provision of choice for schemes winding up under the ‘value for members’ assessments, and proposed VFM framework[footnote 12]. In the contract-based pensions market, this role could be fulfilled by GPPs and group self-invested personal pensions (Group SIPPs).

14. In response to the consultation on “Helping savers understand their pension choices”[footnote 13], all trustees will be required to offer decumulation services with products to members and develop default solutions, based on the general profile of their members either directly, or in partnership with another organisation. This will include trustees of master trusts.

15. In addition, we also envisage that master trusts will play a role in establishing a market for collective defined contribution (CDC) schemes, and we will be consulting on draft regulations to expand CDC to multi-employer schemes early next year.

16. It is therefore vital that these schemes are delivering the best value for their millions of members, and that members are adequately protected. As such, we have reviewed the master trusts market, and are exploring areas where the regime may need to be revisited to equip it for the future.

The value for money framework

17. The VFM framework will have a significant impact on the DC market in the coming years. The policy objectives of this initiative are to drive up standards and consolidate the market around a smaller number of well-performing, well-governed large schemes. The regulators (FCA and TPR) are working together to develop a framework that can be applied holistically across the entire market.

18. We expect that most master trusts, given their scale and governance and their additional authorisation and oversight, will be proactive in ensuring their scheme meets ‘value for money’ metrics. But master trusts should not stop there – these schemes should be striving for the best possible outcomes for their members, focussing on continuous improvement. As part of this review DWP and TPR have identified that there is a role for TPR to play in driving better outcomes within the master trust market, which can begin before the introduction of the VFM framework in legislation.

19. TPR will enhance their approach in the supervision of investment governance in master trusts.

-

As part of an enhanced focus on investment governance TPR will build on the current provision of investment data, seeking an increased flow of more timely investment information. This will enable TPR to closely review the changes to strategies and understand trends in investment, building a market-wide picture and allowing TPR to intervene to warn members at timely moments.

-

This information will be used (alongside information already gathered) to drive better performance by challenging schemes at key moments and will include challenging how decisions are made and the expertise on trustee boards, and prompt schemes to consider their strategy if they are underperforming relative to others in the market and focus on continuous improvement.

-

TPR will evaluate this strategy and explore further with DWP whether any legislative changes may be necessary in future to support this enhanced level of scrutiny.

20. This is part of TPR’s evolving approach, speaking at the Pensions and Lifetime Savings Association (PLSA) conference 2023, TPR’s chief executive officer, Nausicaa Delfas said “In this new pensions landscape, as a regulator we need to go beyond basic compliance, influenc[ing] the market for greater saver outcomes. ”[footnote 14] As the risks of scheme failure in a more mature market will be lower, TPR’s approach can manoeuvre from primarily seeking to prevent and mitigate against failure (although this work will of course continue), to a collaborative supervisory approach, challenging schemes to be in a mindset of continuous improvement. The Department is supportive of the Regulator’s value-led approach and the importance it has placed on increasing its focus on value at pace and over the near term.

21. Going further, should these additional measures require, DWP will seek to legislate to place them on a statutory footing, consistent with the developing evidence-base.

Consolidation

22. The master trust market has seen huge growth. Signs of continuing growth from continuing contributions are very strong, and we must also consider the potential impacts of the Mansion House reforms in further increasing the scale of master trusts.

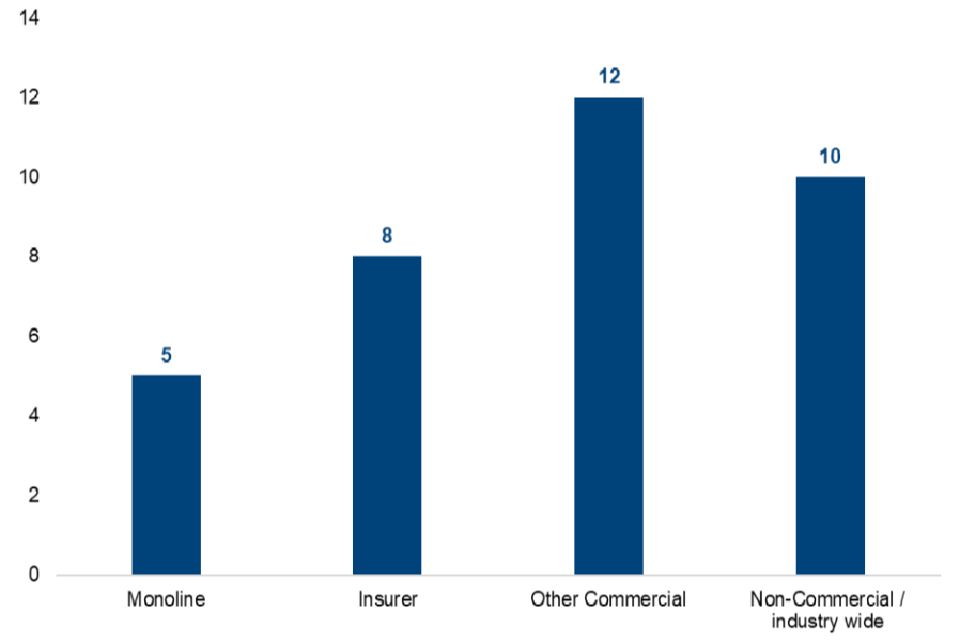

23. Master trusts are in strong competition to scale up quickly, and to do this they need to either attract employers, consolidating single-employer trust schemes, or grow by acquiring other master trusts. Both strategies are resulting in consolidation across the trust-based DC market. Market dynamics are at work, and small or slower growing master trusts have already become targets for further consolidation, with a number of anticipated mergers underway. As master trusts continue to grow in scale, they will become an even greater proposition for employers as they use this scale to develop sophisticated investment strategies, with access to the best expertise, trusteeship and are able to use economies of scale to operate at a low cost. We are encouraged by these market dynamics, which we believe can serve in members’ best interests, with the right focus on value over the risks associated with low cost, and effective competition.

Recommendations

24. In investigating the master trusts market, we have found that the regime is overall fit for purpose at this stage. In the majority of cases, it allows TPR adequate oversight and engagement with master trusts. However, there are areas which warrant further action by TPR in the medium term, and possible further regulatory intervention or regulation by DWP, subject to further evidence.

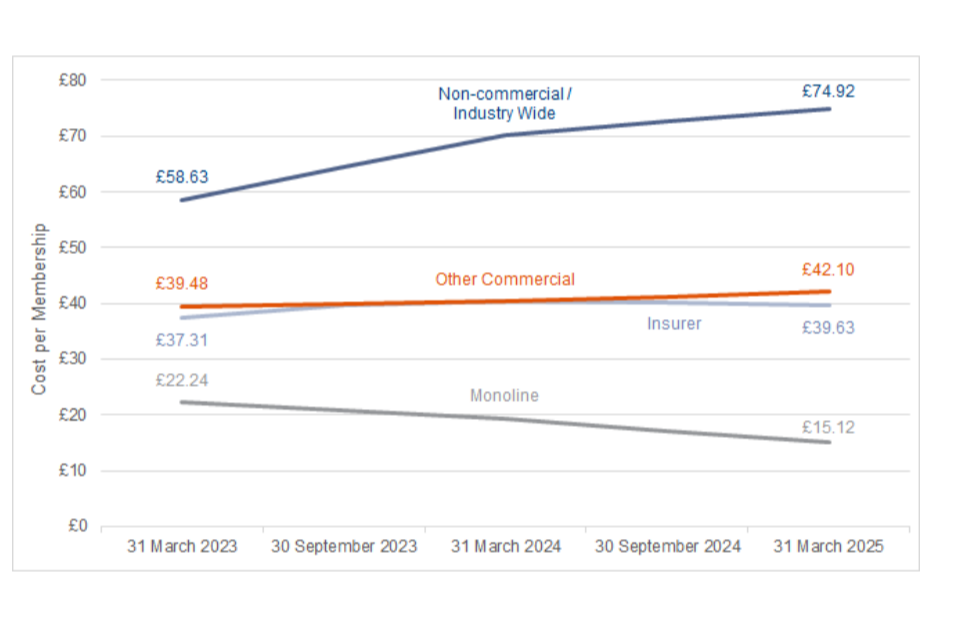

TPR:

-

Will adopt a collaborative supervisory approach, which will focus on value and continuous improvement.

-

As part of an enhanced focus on investment governance TPR will build on the current provision of investment data, seeking an increased flow of more timely asset management and investment information. This will enable TPR to closely review the changes to strategies and to understand trends in investment, building a market-wide picture and allow TPR to intervene to warn members at timely moments.

This information will be used (alongside information already gathered) to drive better performance by challenging schemes at key moments and will include challenging how decisions are made and the expertise on trustee boards, and prompting schemes to consider their strategy if they are underperforming relative to others in the market, focussing on continuous improvement. -

Will evaluate this strategy and explore further with DWP whether any legislative changes may be necessary in future to support this enhanced level of scrutiny.

-

Will expect that trustee boards have appropriate levels of expertise in investments.

-

Will work to define and identify schemes reaching systemically important size and consider what additional oversight these schemes may require.

-

Will consider how to mitigate against potential conflicts of interest arising from multiple trustee appointments.

DWP:

-

Will support TPR in its focus on value, enhanced investment governance and forward-looking strategy, and will consider legislative changes if necessary.

-

We will keep under consideration and may further explore changes to the regime which have been highlighted through this work. This may include:

1. Amending the regime to consider market withdrawal in the cases of mergers and acquisitions, ensuring that the regime is appropriate for these circumstances, and that TPR have proper oversight.

2. The addition of the chief investment officer to the list of persons who are required to undergo a ‘fit and proper’ persons check.

3. The addition of risk notices as part of the master trusts regime.

4. The removal of pre-agreements in tightly prescribed circumstances, to promote further market competition, if necessary.

As scale in the market is built and the VFM framework is embedded, we intend to work with TPR to understand competition in the market and any further emerging risks resulting from scheme size.

25. As part of this work, we also identified that employer motivations are often cost-driven. In addition to the VFM framework, there may be several levers which could make a positive impact on this picture, shifting the focus onto value, including publishing further information for employers on selecting a pension scheme, as proposed in the response to the call for evidence “Pension trustee skills, capability and culture”.[footnote 15]

26. TPR’s overall approach to supervising the master trust market will continue to evolve as the market changes. DWP supports this commitment to protect savers’ money, to enhance the pension system and, as we look to the future, help to drive innovation which is member-centric and in savers’ interests.

Background

27. A master trust, as defined by the Pension Schemes Act 2017 (the Act)[footnote 16] is an occupational pension scheme providing money-purchase benefits that is used (or intended to be used) by multiple unconnected employers and is not a relevant public service pension scheme. TPR was given the role of authorising and supervising these multi-employer schemes, and therefore master trusts must satisfy TPR that they meet the 5 authorisation criteria set by the Act in order to be granted authorisation. TPR supervise master trusts on an ongoing basis in line with the authorisation and the regime and following its introduction, the market has consolidated with the withdrawal of over 50 schemes.

28. Master trusts operate as part of a wider workplace pensions market that includes single-employer trusts, as well as contract-based workplace[footnote 17] pensions. The FCA regulates the contract-based workplace pensions market, and TPR regulates the trust-based market.

29. Prior to 2018 there was no minimum requirement to enter the master trust market and little protection for members if a scheme were to fail. These risks had the potential to be exacerbated by the loss of direct employer oversight. The regime had the following objectives:

-

to ensure that only well-run schemes which could reach financial sustainability, were permitted to operate,

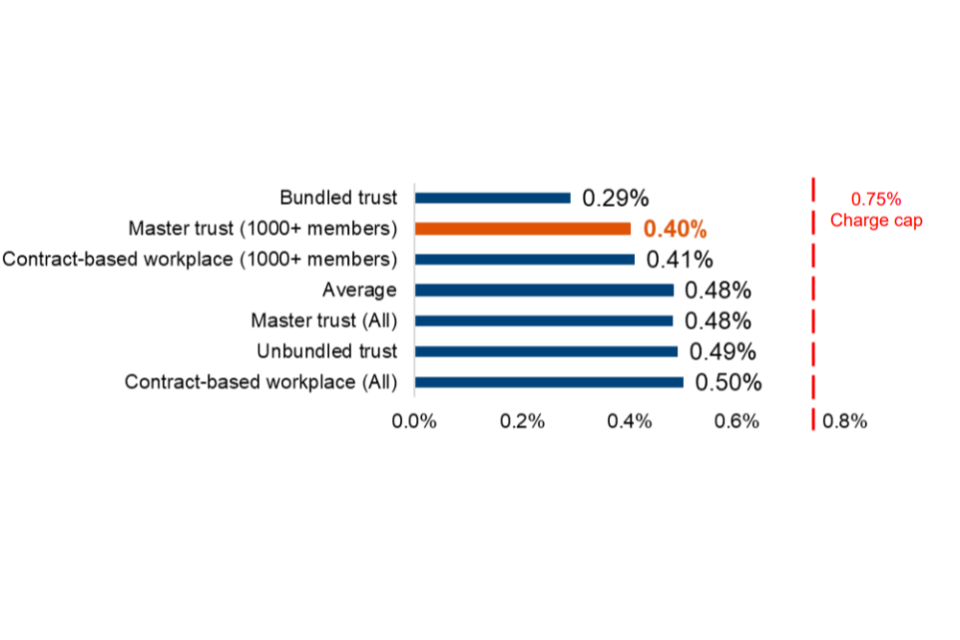

-

to ensure that members of master trusts were as well insulated from risks that were largely unique to the master trust market (protecting member pots in the event of scheme failure) as possible and,

-

to ensure that risks arising from scale or scheme structure are identified, and that there is an appropriate balance of risk prevention and intervention.

30. Government expected the market would contract by way of merger of schemes as a result of some being unable to meet the requirements placed on them with the coming into force of the master trust Regulations 2018[footnote 18] and strict authorisation criteria. It was also anticipated that some schemes would withdraw prior to Royal Assent of the Act, which is why it was given retrospective effect, to protect members of exiting schemes.

31. It has been 5 years since the master trusts regulations came into force. AE has been successfully rolled out which has resulted in high participation and low opt-out rates and increased pension saving. In 2022, £29 billion more in real terms was saved into pensions in that year compared to 2012, when AE was rolled out.[footnote 19] 90% of members, and 95% of active members in the trust-based market are in master trusts[footnote 20], and we have already discussed the projected scale of this market.

Therefore, now is the right time to review the master trust market to explore:

- how it has grown and how schemes are performing,

- how market forces are shaping it,

- what consolidation activity is happening, and

- how it can be further developed for the benefit of savers now and in the future, before the market truly enters ‘super’ scale.

32. We know that scale generally improves member outcomes, (although within the master trust market there is a wide variation in returns) as schemes make efficiencies and improve governance[footnote 21]. As such, government has been making the case for greater consolidation since 2019 in the consultation “Investment Innovation and Future Consolidation.”[footnote 22] Consolidation primarily can help improve member outcomes, but has a secondary effect in increasing scale. The overall DC trust market has seen steady consolidation, from 2,180 schemes in 2018, to 1,220 in 2023, and could fall to around 500 schemes by 2030 on current trends.[footnote 23]

33. But as well as reducing the number of small schemes, we would welcome consolidation at the large end of the scale where it is in the members interests, so that master trust members can further realise the economies of scale and efficiencies that can come from mergers even at the largest size, as seen in Australia,[footnote 24] where seven of the eight largest ‘My Super’ entities have around £30 billion in assets under management – with the largest entity managing almost £100 billion. Though we must also be mindful of the risks of market consolidation, should this reduce employer choice, concentrate risk, and create an oligopoly. Therefore we want to continue to see smaller master trusts with unique propositions or technology and the appetite to scale quickly, challenging the largest schemes, creating competition and driving up standards. Until very recently, consolidation within the master trusts market slowed after an initial contraction following introduction of the authorisation and the regime. We have considered market dynamics affecting this plateau and if there are barriers in the regime to mergers and acquisitions.

34. We are working towards a future where a smaller number of very large master trusts are in operation, (alongside several smaller master trusts) providing members with sustainable returns, from a wide range of assets, providing excellent governance and good user experience. There is a direct link to the VFM framework jointly proposed between DWP, TPR and the FCA, where schemes will be required to assess and disclose their investment performance, asset allocation, member charges and quality of services. The VFM framework has the potential to create further competition and raise standards across the market, but there is also a role for TPR to play to drive value within the master trust market.

35. We have seen from other industries that as entities reach systemically important size, there is a need for close regulation, due to the consequences of failure. However, where efficiencies in regulation can be realised for both industry and the TPR, there may be areas where the burden of regulation may be relaxed in future.

36. When the regime was introduced, government sought to allow the master trust market to evolve in a way which supported good member outcomes through healthy competition, and which achieved the appropriate balance between protection of scheme members and the regulatory burden on business – these priorities remain true.

Undertaking the review

37. When the Master Trust Regulations 2018 were introduced, The Department for Work and Pensions committed to “keeping these policies under review and should any issue arise with these policies, it will assess the evidence and, if appropriate, consider whether any changes may be necessary.”[footnote 25]

38. An independent review of TPR was published in 2023, and although the review of the master trusts market and authorisation regime does not directly address the recommendations in that report, it is conscious of TPR’s regulatory responsibilities and how they might evolve as the market grows and changes. In particular we consider TPR’s role relating to investments which was also explored as part of the independent review. The lead reviewer recommended that “I do not believe that TPR should be given a statutory duty in respect of economic growth but – considering its statutory duty towards the interests of savers – it should have a view on how regulation can drive investment behaviour that is in savers’ best long-term interests.”[footnote 26]

Chapter 1: The shape of the market

Development since authorisation

39. Master trusts dominate the trust-based DC landscape. There are currently 35 authorised master trusts in operation.[footnote 27] These 35 schemes hold 95% of active members, 74% of assets, and 90% of asset growth within the trust-based DC market (excluding hybrid schemes[footnote 28] and micro-schemes[footnote 29]). [footnote 30]

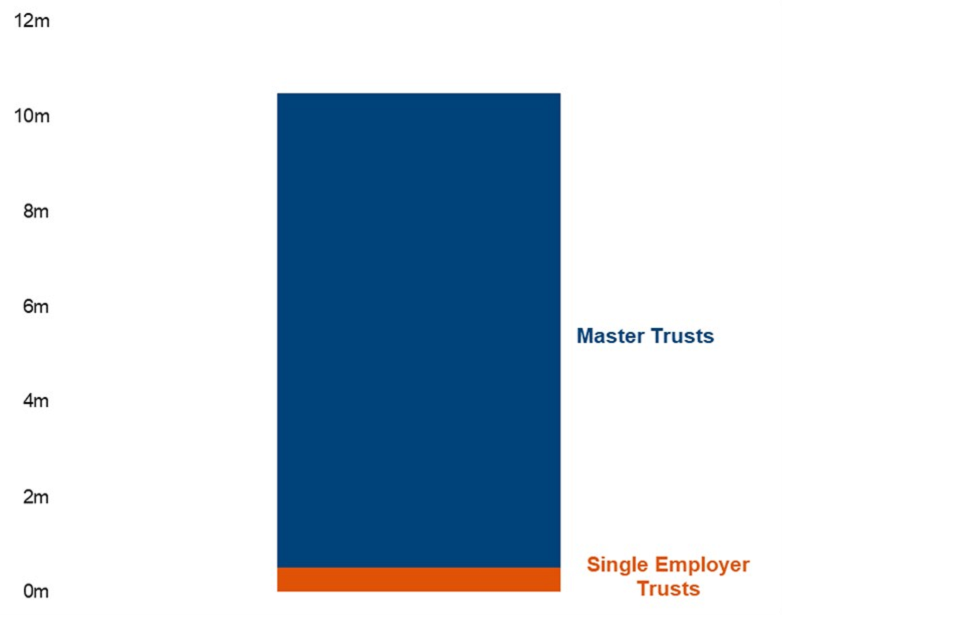

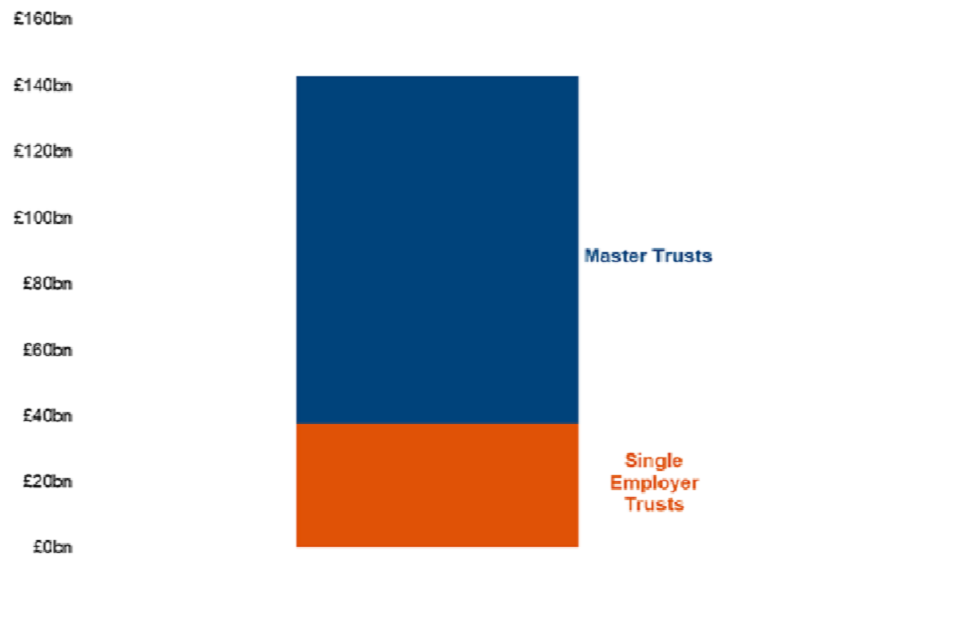

Figure 1: Active memberships in master trusts vs. single-employer trusts (2023)[footnote 31]

Figure 2: Asset split between single and master trusts (2023)[footnote 32]

Figure 3: DC trust assets, master trust assets, and master trust assets as a proportion of DC trust assets (right-hand axis)[footnote 33]

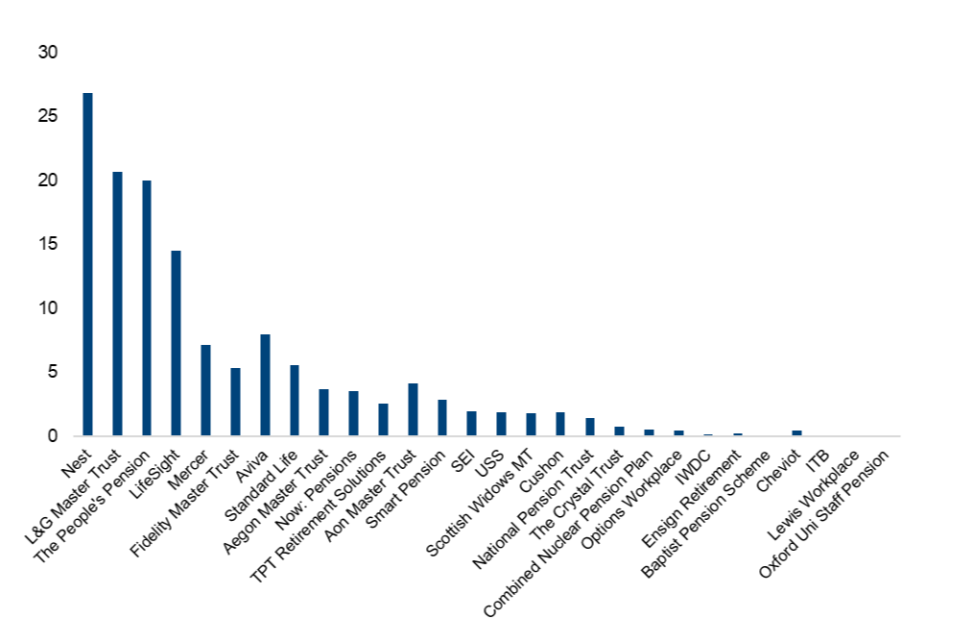

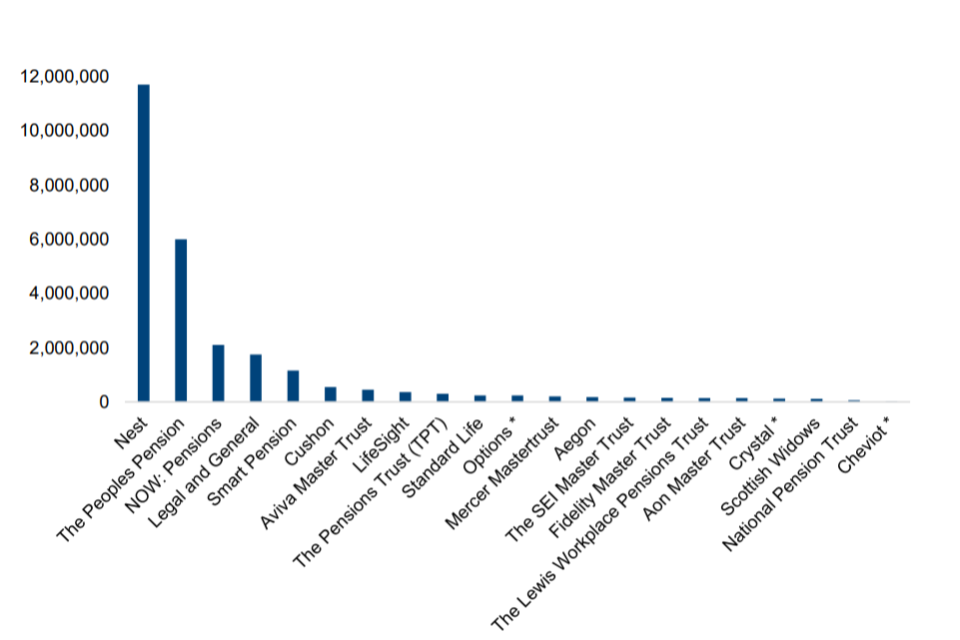

40. There is concentration within the market of memberships and assets. The top 5 (by assets under management) master trusts account for around 60% of trust assets held and around 80% of savers in the trust market.[footnote 34] By 2030, we expect the largest 5 schemes by assets under management to have over 80% of the share of memberships. And DWP analysis shows that a large majority of savers could be in schemes of over £30 billion (albeit this analysis uses assumptions which are volatile and subject to future market conditions and policy changes). [footnote 35]

41. Compared to the more mature Australian market (whose equivalent of AE started in 1992 and where contribution levels are greater than the UK), made up of more than 50 ‘My Super’ entities (as well as a large number of small funds),[footnote 36] the UK master trust market is already more concentrated, with the UK’s largest master trusts beginning to reach comparable scale. The UK master trust market will continue to develop, particularly as a result of the structural shift away from defined benefit (DB) schemes (where less than 1 million people save into a private sector DB scheme[footnote 37] ) and the continued rise of DC, combined with various policy initiatives to drive scale and consolidation.

Figure 4: AUS/UK scheme assets under management (2022)[footnote 38]

42. The asset value contained within master trusts is also more concentrated in the UK than in the Australian market. In Australia, the largest ten funds account for almost half of market assets and one third of its memberships, whereas, according to Go Pensions data the largest five master trusts account for slightly less than two thirds of assets.[footnote 39]

Figure 5: Assets of DC trust scheme default funds (£billions)[footnote 40]

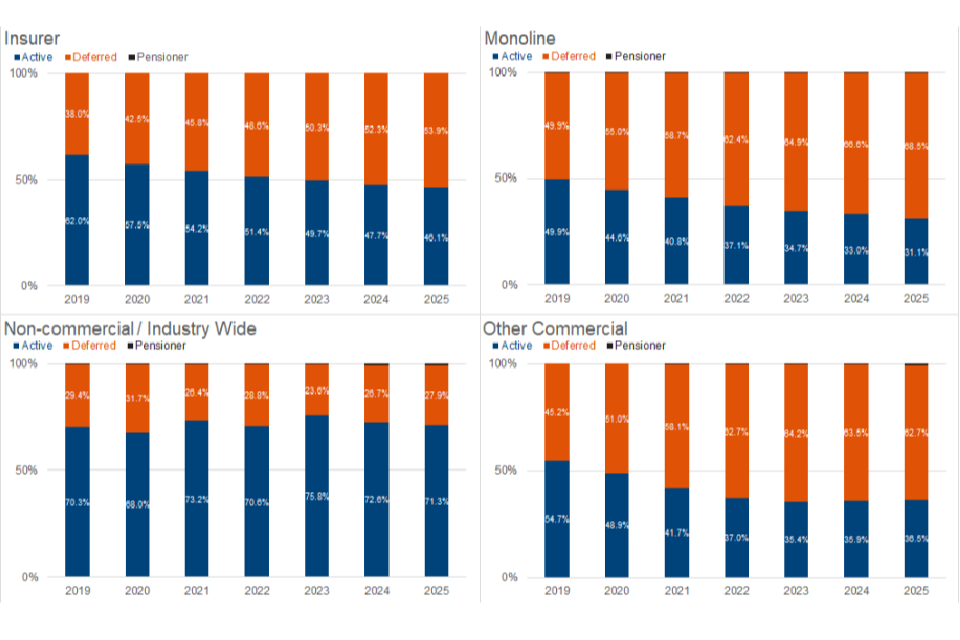

43. Membership too, is very concentrated within the UK master trust market. Around 80% of members across master trusts are concentrated in just 5 schemes.[footnote 41] Also of note is the shifting balance between active and deferred memberships. As of 30 September 2023, 64% out of a total of 27.3 million master trust memberships was deferred status, and TPR data indicates that the ratio is likely to continue to widen.[footnote 42] This statistic indicates that the management of smaller, deferred pots is likely to remain a key consideration for providers in the future.

Figure 6: DC master trust by number of members[footnote 43]

44. The concentration of assets and memberships within the master trust market is significant. It suggests that scale is being achieved within these schemes, which is likely to impact on member outcomes as economies of scale are realised.

45. Commercial master trusts[footnote 44] remain optimistic about their growth potential although TPR estimate that long term, this optimism has the potential to exceed the actual size of the available market given the significant overlap in the growth strategies and target markets of some master trusts. This points to the further consolidation of master trusts that we are beginning to see, as not all schemes’ growth strategies may be as successful as anticipated.

Figure 7: DC Master trusts – projected AUM growth by market segment[footnote 45]

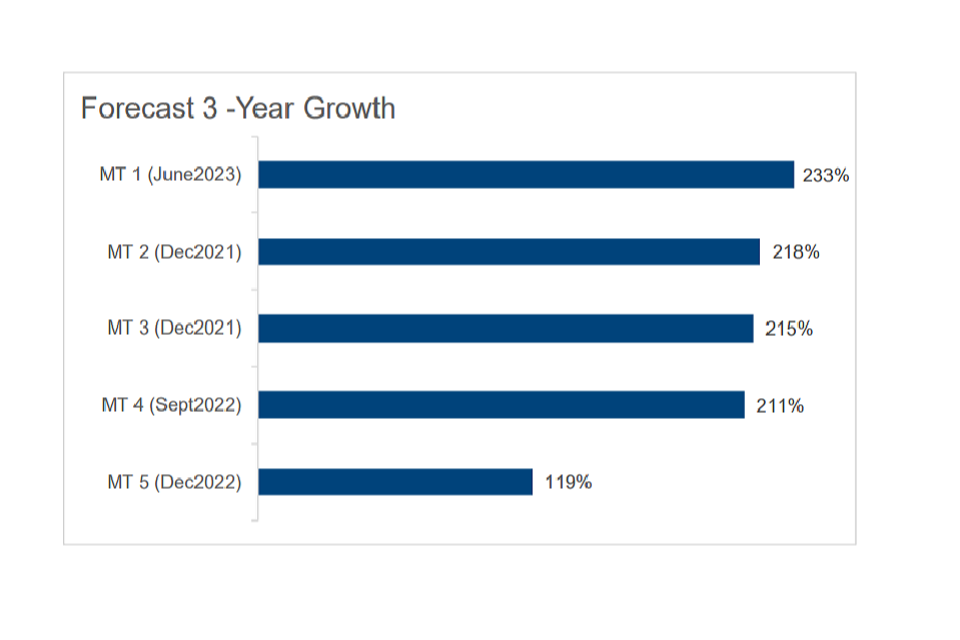

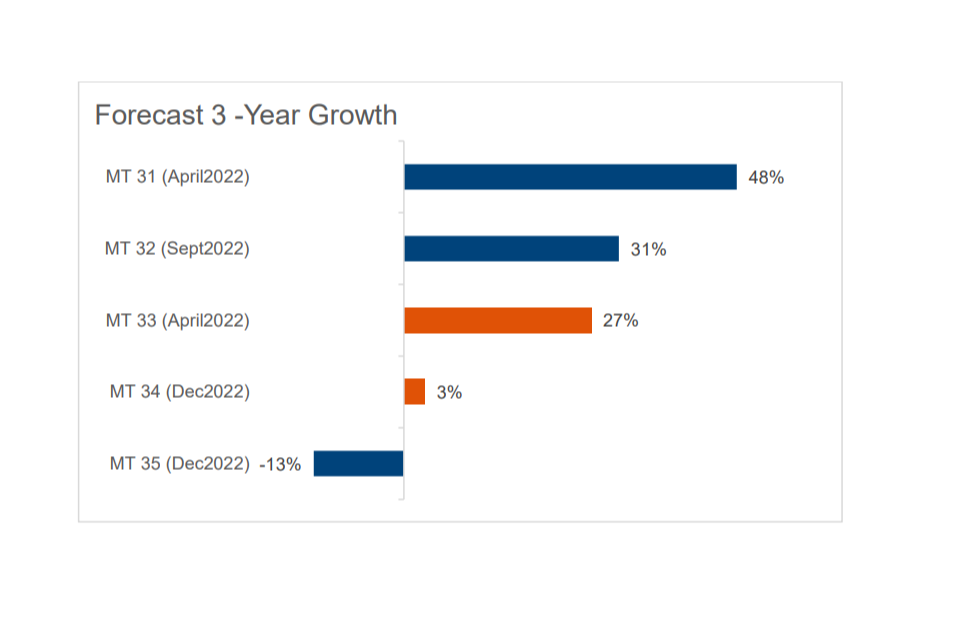

46. Scale is vital for longevity, and schemes that can demonstrate that they have plans for growth may be a more compelling proposition for business. Figures 8 and 9 below show growth in the master trusts with the highest and lowest master trusts by forecasted 3-year growth in assets under management. In the top 5 are master trusts that have been active consolidators in the very recent past, which indicates that a combination of organic and inorganic growth strategies can provide competitive growth. These fastest growing schemes are at the smaller end of the scale, as they can increase faster proportionally owing to their smaller size. Conversely, out of the bottom 5 performers 2 of these (bars highlighted in orange) are at various stages of the consolidation process, showing that there is a commercial imperative underpinning the survival of master trusts, and not all schemes have been able to effectively commercialise their operations.

Figure 8: Highest 5 schemes by forecast 3-year growth in AUM[footnote 46]

Figure 9: Lowest 5 schemes by forecast 3-year growth in AUM (orange highlight indicates a consolidating scheme[footnote 47]:

47. We wish to see growth in the market so that scheme members can benefit from efficiencies, but it would not be in savers’ interests to see a market dominated by average performers who just happen to be large. The current master trust market shows no correlation between size and investment returns. This demonstrates the need for balance between scale and value. We wish for the market to remain a competitive environment where smaller, more agile master trusts with unique offerings can challenge the largest providers by attracting clients through novel propositions. The proposed VFM framework will provide a cross-market mechanism to support this.

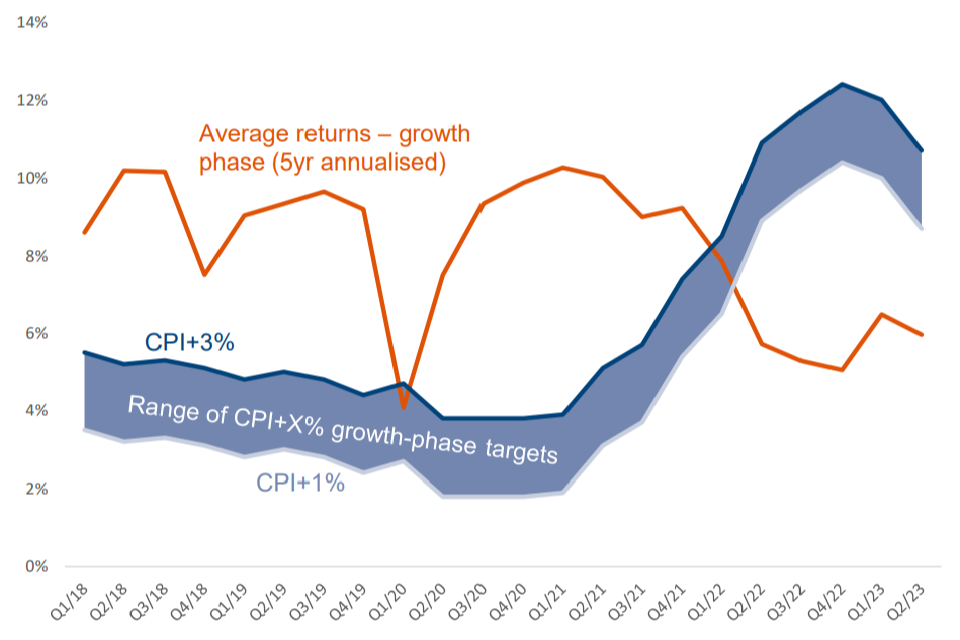

48. Generally, master trusts have performed well in the last 5 years, albeit the COVID-19 pandemic, above-target inflation, and Autumn 2022’s bond market spike presenting challenging investment conditions. 5-year annualised returns show more consistent performance above commonly used benchmarks of CPI+1% (or 3%), especially from 2018-2022. Comparing against long-term inflation assumptions (around 2%), many schemes would still be outperforming despite challenging investment markets (see figure 10).

Figure 10: CAPA average annual investment returns in the growth phase, compared to a range of CPI+X% targets%[footnote 48]

Summary:

-

The master trust market is achieving scale, with greater assets under management collectively than single-employer trusts, and this scale will continue to grow in the coming years. However there are still a number of large individual single-employer trusts.

-

Concentration of memberships and assets is high within a handful of schemes.

-

Further consolidation is likely, as schemes without strong growth become targets for consolidation.

-

Deferred members make up a significant proportion of overall memberships.

Market segments

49. Although there are 35 authorised master trusts, a few of these schemes are operated by the same sponsor: split into separate master trusts for administrative or historical reasons, or are in the process of merging with another master trust, the process of which takes some time to complete. As far as we understand, the intention is for these acquired schemes to be fully merged, leaving a more consolidated pool of under 30 master trusts.

50. The Master Trust Regulations 2018 have enabled different types of organisations to apply to become authorised, recognising that different organisations will cater for different demographics. As such, one way to categorise the market is along these organisational lines.

51. There are commercial master trusts:

-

Monolines – schemes set up to specifically cater for the mass AE market

-

Master trusts sponsored by insurers –these insurers may also provide workplace GPPs, individual personal pensions and life assurance products, as well as other products such as annuities.

-

‘Other commercial’ – this group consists of employee benefit consultancies and other organisations.

And non-commercial or industry wide master trusts, serving discrete communities.

Figure 11: Master trusts by market segment[footnote 49]

52. Master trusts are regulated by TPR. However some of the sponsors of master trusts are also regulated by the FCA for other parts of their business. This includes all of the insurers, as well as some other commercial master trusts. These organisations must meet the FCA’s expectations, including in relation to the Consumer Duty, where relevant and where they have a material influence over these.

The role of the FCA

Master trusts and single employer trusts are supervised by TPR. The contract-based DC market is regulated by the FCA and covers workplace and non-workplace pensions. The workplace segment of this market covers 12 million members with £260 billion in assets under administration (compared to 18.2 million members with £218 billion in the trust-based market).[footnote 50]

The FCA regulates around 100 firms[footnote 51] that provide individual personal pensions, stakeholder personal pensions, self-invested personal pensions (SIPPs), GPPs and Group SIPPs, as well as retirement income products such as annuities.

The FCA’s regulatory reach in the pensions and retirement income market also extends beyond firms that sponsor pension schemes. The FCA regulates firms and individuals that advise on investments including pensions, and that provide DB pension transfer advice, as well as asset managers and other investment services firms. This includes firms providing investment services to occupational schemes and master trusts, except where they provide advice on asset allocation or investment strategy.

The FCA has a range of supervisory tools to monitor and support ongoing compliance, and enforcement powers that can be exercised if a firm does not meet these expectations and requirements, including disciplinary sanctions, fines and de-authorisation, where appropriate.

53. The schemes which responded to the demand for pension provision created by the AE mass market, the ‘monolines’, cater for a wide range of employers, including those who may not be as attractive to other parts of the market. For example, many small businesses who have fewer employees and/or employees with lower average earnings and, therefore, smaller pension pots. There may also be a higher proportion of workers on short-term contracts who will not provide as regular an income stream for schemes than permanent employees. National Employment Savings Trust (Nest) was set up with a public service obligation to take on any employer who chooses to use the scheme, including those with lower-paid workers and/or those on short term contracts who may not be as individually profitable. Nest is the largest master trust with over 11 million members and £30 billion in assets under management.[footnote 52] Nest proved the trust-based, low-cost digital model could work at scale and other providers have entered to cater to the workplace pensions mass market. Other providers have seen the value in attracting a high volume of members to reach scale, looking at future profitability of their entire book, rather than how profitable each employer or member is to them.

54. As the monolines cater to the mass market, they generally have higher membership numbers and therefore higher volumes of contributions (depending on the proportion of active members) as a result and have realised some efficiencies which have led to the lowest operating costs per member across organisational types (see figure 12). These low costs are a key factor in helping the monolines to continue to attract new business, continue growth and secure external investment. This segment of schemes also has a greater proportion of deferred small pots, which are proportionally more expensive to administer, something which the government aims to mitigate through the automatic consolidation of eligible small pots into a small number of authorised default consolidators.[footnote 53]

55. For the insurers and other commercial master trusts, a master trust is typically part of the parent company’s wider offering in the pensions space, which may include GPPs,[footnote 54] asset management, investment advice, saving vehicles, pensions consultancy and life assurance products, and the master trust can benefit from scale built across the business. For these providers, a master trust offered an opportunity to expand their business and leverage existing expertise and contacts in pensions, capitalising on the growing popularity of multi-employer schemes.

56. Employee benefit consultancies (EBCs), asset managers, and insurers sponsoring master trusts may be attractive to employers who are looking for more bespoke arrangements, as they are likely to offer a wide range of funds in addition to the default, through their wider business. The relationship between bespoke and default funds is discussed at paragraph 116.

57. There is a more disparate group of ‘other’ commercial providers who have a more unique offering, for example through their technology, investment strategy, or extended services such as financial advice.

58. Across these commercial market segments, different schemes are likely to be competing for different, though overlapping employers or industries, rather than the ‘mass AE market’ of the monolines. For example, these schemes may use their resources to seek out the largest employers, or large employers with high average earners within a certain sector, as these clients represent bigger wins than seeking out smaller businesses which take time and resource to onboard, for less immediate profitability. Where master trusts are seeking out the same clients, (often competing through an employer’s use of a consultancy or intermediary), some schemes will be unsuccessful, and as a result may not reach scale via their chosen strategy, resulting in scheme consolidation.

59. There are also the ‘non-commercial’, or ‘independent’ master trusts. These are generally related to a single industry but have been captured by the regime by virtue of their structure. For example, the Superannuation Arrangements of the University of London (SAUL), provides a pension for the employees of the University of London, but as this is made up of multiple employers, this scheme was required to apply for master trust authorisation. This group of schemes are not competing in the market in the same way as the other master trusts and have smaller memberships. The average cost per member in these schemes is also significantly higher than in other master trusts, but members do not necessarily feel this through their charges, as these more paternalistic employers may offset this. For these reasons, they may be thought of as more of an extension of the single employer trust market, bringing the de facto number of commercial master trusts down further, from under 30, to below 20 schemes.

60. These different market segments have varying operating costs (see figure 12), with average costs predicted to fall across insurers and monolines. Costs are predicted to fall the fastest in the monoline schemes, who are already operating at, on average, a lower cost per member than other segments. The insurers and other commercial schemes have higher operating costs per member. However, it is also important to note that operating costs within these segments vary, and therefore some schemes may have found greater operating efficiencies than others. It is unclear why costs are higher for these groups, it could be due to the clients they attract, associated costs within their supply chain or other reasons. For the non-commercial schemes, higher operating costs may not be passed onto the individual members, as they may be absorbed by paternalistic employers.

Figure 12: Average cost per member by organisational segment[footnote 55]

61. We have heard from various master trusts that the market is not yet mature; as well as seeking scale, many schemes are making large investments in technology, administration, and other areas. These project costs may be reflected in current overall costs, but you might expect these to reduce once these projects are complete and the benefits come on stream. A Pensions Policy Institute (PPI) report in 2020 highlighted the significant investment required to set up a master trust, including repayments of capital to fund their initial startup, which impacts costs, and flagged that it is harder for organisations without existing pension infrastructure to enter the market.[footnote 56] We predict that this will continue to be the case as schemes grow.

Summary:

-

Different market segments have different characteristics, competing for different employer types. Some of this competition overlaps, meaning there will be winners and losers in scaling.

-

Non-commercial master trusts should be thought of as an extension of the single-employer trust space, subject to higher levels of regulatory oversight, but not seeking to increase scale to gain a higher market share.

-

Operating costs vary across market segments, with monoline schemes benefitting from the lowest costs per member, which are set to decrease even further.

Chapter 2: Increasing scale, reducing costs, supporting diversification

62. Not all master trusts have reached breakeven (revenue greater or equal to costs). Before this point is reached, the scheme funder will see no direct return on their significant investment to set up the scheme. If this continued, or if it was predicted that it would take a long time to reach profitability, this would not be sustainable for the scheme funder, and they may take the decision to consolidate. If evidence cannot be provided to TPR that the scheme is commercially sustainable in the long term, TPR would consider withdrawing authorisation. An exception to this may be where the master trust exists to introduce clients to the sponsor’s wider business. It may be more sustainable for these organisations to continue running the master trust at a loss, on the basis that this is sustainable when looking at the broader business. TPR review these strategies to ensure commercial sustainability.

63. The view that the master trust market will further consolidate is held by many in the pensions industry. Lane Clark & Peacock (LCP) recently predicted that the market will contract to around 10 providers, and that larger single employer trusts will also move to master trusts in the coming years.[footnote 57]

64. Reaching scale can be achieved through organic or inorganic growth.

Organic growth involves the continuing contributions and investment returns of current scheme members, and attracting:

a) employers who have been running their own single employer trust,

b) employers seeking to fulfil their AE duties,

c) employers moving from master trust to master trust, the ‘secondary market’, and

d) employers moving from contract-based arrangements to a master trust,

There is limited movement from contract-based to master trusts, and as we will discuss, a secondary market is only just beginning to emerge. Inorganic growth involves acquiring another master trust to achieve scale quickly. This is discussed in chapter 3.

65. As AE has been fully rolled out with over 2 million employers having fulfilled their duties, growth by attracting new employers is limited. Initially this was very fruitful due to the volume of employers required to fulfil their duties.[footnote 58] Business could be attracted based on cost (including whether or not there is an employer connection fee), on the package of assistance provided for employers to ensure that they were correctly fulfilling their duties, or business could be attracted via an employer’s supply chain, for example, payroll providers. The independent review of TPR found that “It was suggested to me that accountants, financial advisers and payroll providers play an important role in influencing outcomes for savers, on the basis that many small businesses look to these intermediaries to recommend a pension scheme, and payroll providers in particular are well-placed to ensure compliance by small businesses with AE obligations.”[footnote 59]

66. New business from single employer trusts can be won through direct engagement with employers, or the use of intermediaries or consultancies, who consider the different offerings of schemes on behalf of their clients to aid in the selection process.

67. Scale itself is a boon to attracting business from single-employer trusts. TPR operational insight has found that larger single-employer trusts are unlikely to select a small master trust who cannot evidence managing a scheme of very large size, and whom these employers may be less confident in a smaller master trust’s ability to stay in the market. Therefore, scale begets scale.

68. While the ‘back book’ of members is valuable through the charges that larger pension pots bring as they grow from investment returns, active membership is incredibly important for building scale. Active members will create a steady income stream for the master trust and will create greater organic growth through ongoing contributions. TPR analysis has shown that without healthy active membership, profitability and efficiencies are limited.

69. Deferred memberships are growing across commercial master trusts (see figure 13), with around 60% of memberships in trust-based market being deferred pots.[footnote 60] As set out in the government response to the consultation on “Ending the proliferation of deferred small pots”,[footnote 61] we have confirmed that we will implement the multiple default consolidator approach to automatically consolidate individuals eligible deferred small pots. This will reduce the number of deferred pots which schemes hold, which are mostly unprofitable.

Figure 13: Deferred membership growth, historic and projected[footnote 62]

70. Active membership can be built by attracting new employers and/or single-employer trusts or acquiring other master trusts to generate growth. Schemes which can show that their assets or memberships will grow will be valuable clients and will be able to negotiate lower fees with the promise of future business. For asset management, scale increases the opportunities available to schemes and enables them to create sophisticated investment strategies within the default, as asset managers seek to win business. In addition to investment funds, schemes with very large scale can create discretionary portfolios, which allows greater breadth of investments, increased flexibility and innovation in how this fund is used.

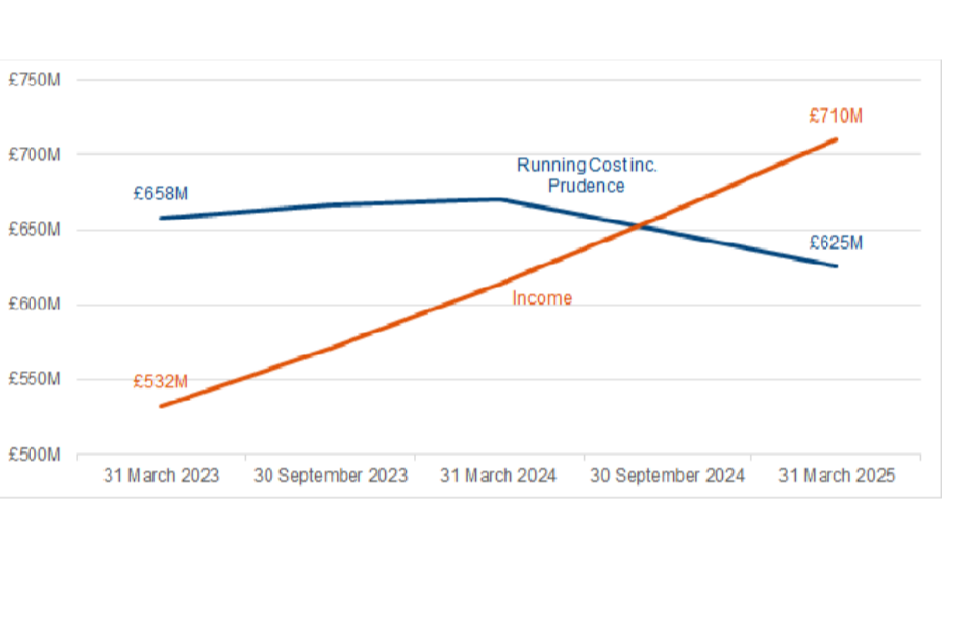

71. Increased scale should generate operating efficiencies by reducing the average cost per product. Securing low costs is an effective business model as it helps schemes win business and create further scale through the offer of lower member charges, borne out of these supply-side negotiations. However, TPR have not yet seen evidence of a simple correlation between scale and cost reduction, rather, as income is increasing, there are signs that costs are beginning to level off at the aggregate level (see figure 14). Total running costs are likely to continue to rise as increased assets and membership are managed.

Figure 14: Master trust running costs and income[footnote 63]

72. Though economies of scale may be being found at scheme level, we cannot confidently currently conclude that economies of scale are yet being realised across the master trust market. This may be due to the relative immaturity of the market, as schemes continue to make investments to improve their propositions. This may include reducing member charges, making for technological or system improvements, or decumulation offerings. Investments in these types of scheme improvements may temporarily increase operating costs and/or member costs, but are likely to be positive for scheme growth, governance and/or members’ overall offering. Master trusts operate in a competitive environment, and this can create a positive competition feedback loop, as schemes compete on their overall offering.

73. Some master trusts achieve efficiencies by limiting the number of available funds and operating a single or very few default funds, therefore reducing operating costs. Where schemes operate a wider pensions or insurance business, efficiencies may also be found. Schemes with existing experience in the wider pensions market also create efficiencies through effective models of governance which is also very important for competition, as trustees can challenge the decisions brought to them and seek improvements through their supply chain.

74. As schemes become even larger still, a range of investment skills and capability is likely to be brought in house. This will help to reduce costs once embedded, and would give these master trusts even greater freedom over their investments. Nest, the largest master trust, has an in house investment team which manages all important investment decisions and processes. This enables Nest tight control of their strategy, access to new markets and more efficient management of risk.

75. A report by the PPI looking at evidence from the Netherlands and US, found that £0.5 billion in assets under management was optimal for reducing member borne costs specifically,[footnote 64] after which point there are diminishing returns. Looking wider, sources from Australia have suggested A$30 billion is needed to be competitive within that market,[footnote 65] and efficiency gains can still be achieved at A$100 billion.[footnote 66] Efficiencies from mergers of Australian schemes have been evidenced even at the largest size;[footnote 67] though this is largely driven by lowering costs (rather than via investment returns). Costs are unlikely to increase completely linearly with membership size, and likewise, governance processes may not need to undergo large changes due to increased membership, especially if the scheme is already a considerable size.

76. Likewise, the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, in the consultation “Local Government Pension Scheme (England and Wales): Next Steps on investments”,[footnote 68] explored asset pooling within local government pension schemes (LGPS), and the scale benefits that this can bring. By pooling assets, significant savings have been made, and expertise and capacity has been developed in private markets. It is DLUHC’s assessment that in pooling assets, the benefits of scale are present in the £50-75 billion range and may improve as far as £100 billion. As such, government also wishes to see further scale within the master trust market.

Diversification: The Mansion House Compact

77. Beyond the potential cost savings associated with greater scale, there is evidence that scale can support the diversification of pension schemes into less liquid assets such as private equity. Key channels through which this may occur include the ability to bring specialist investment capabilities in house, increased bargaining power with intermediaries and access to a wider range of investment opportunities.[footnote 69] The Pensions and Lifetime Savings Association has argued that larger schemes, for example those with more than £25-50 billion of assets, have considerable governance capability and find it easier to invest directly, or alongside others, in productive finance.[footnote 70] The think tank New Financial has argued that a more concentrated market of super trusts with around £50 billion of assets each would be enabled by economies of scale, wider investment horizons and increased professionalisation to invest in a broader range of assets in the long term interest of their members.[footnote 71]

78. At this stage, there is no clear evidence that the scale efficiencies being seen are being passed onto members either directly, through lower charges, or indirectly, through greater spending on investment and development of investment strategy. In 2022, Corporate Advisor, in their ‘master trust and GPP defaults report, found that “none of the master trusts and GPP providers included in this report say they expect to change the amount spent on asset management within the next two years. However, as they achieve greater scale, they may be able to embrace innovative charging structures within their existing overall price constraints.”[footnote 72] We currently lack evidence on the breakdown of fee budgets, but as government increases focus on value for scheme members, this is something we will seek to understand.

79. It is highly promising that 10 organisations are now signatories to the Mansion House compact, intending to achieve a minimum 5% allocation to unlisted equities, 9 of which sponsor a master trust. The signatories come from across the scheme types, including monolines, insurers, and an employee benefit consultancy (EBC).

80. It is also important to note that members of the Mansion House compact are not the only schemes investing, or considering investing in private assets. A few master trusts dedicate the same or an even greater proportion of their default to private assets and sit outside of the top 10 schemes by assets under management. This demonstrates that scale is not the only factor determining allocation to private assets, which may include investment expertise from the scheme funder (or might indicate that scale is achieved through the wider business).

81. Scale can increase access to private assets by increasing the probability that the scheme has the internal capabilities to deal with these investments and is likely to be able to negotiate lower investment fees. There are, however, risks relating to scale which have been studied in the Australian superannuation system.[footnote 73] For very large schemes, whilst allocating assets to investments in private markets, schemes rightly consider liquidity management – their ability to transfer or sell those assets in the event of a merger or acquisition. Investment in different asset types may also be linked to scheme demographics, particularly regarding average proximity to retirement and knock-on liquidity considerations.

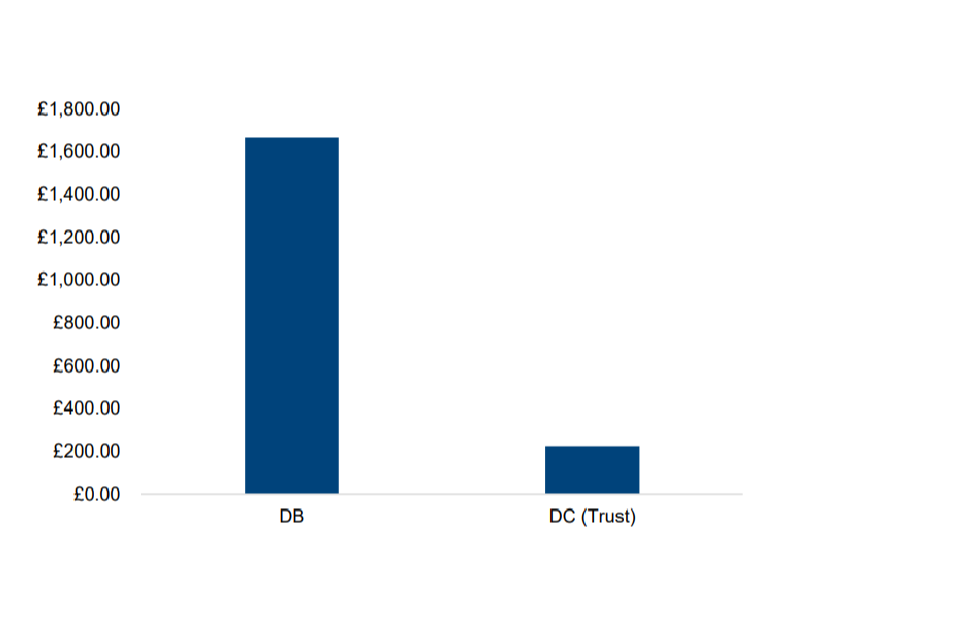

82. The DB market holds over 7x the assets of the current trust-based DC market,[footnote 74] however this does not prove a good example of how scale can be used to diversify in high growth assets as most DB schemes are closed to new members and are maturing. They have therefore been gradually de-risking their investments, as they have less time to recover from the effects of volatility.

Figure 15: Private sector defined benefit assets v defined contribution assets (trust-based market) 2022[footnote 75]

83. This is in contrast to LGPS, an open scheme, which the report ‘Investing in the Future: Boosting Savings and Prosperity for the UK’ cites as a good example of schemes with scale and long-term horizons investing in productive assets.[footnote 76] However, it is important to note that LGPS are not subject to the same market pressures as commercial master trusts, with the associated impacts on charges and liquidity.

84. On balance we consider that there is persuasive evidence that schemes operating at a very large scale, with a healthy active membership, are likely to realise scale efficiencies in future, and can be better placed than smaller schemes to create diversified investment strategies, including investments in new asset classes with the associated potential benefits for saver outcomes.

Summary:

-

Master trusts have different growth strategies, and seek to reduce operating costs through building scale, refining their product offering, and by negotiating with their suppliers (asset managers, third party administrators etc.)

-

Active membership is key for creating a steady income stream for master trusts.

-

Scale can bring a range of benefits to savers and through these benefits can support the diversification by pension schemes into a wider range of investments.

Charges

85. Members in default funds are subject to low charges as schemes are operating well below the 0.75% charge cap. 83% of members in default funds are subject to fees of 0.5% or less.[footnote 77]

Figure 16: Average ongoing charge (as a percentage of funds under management) paid by members, by detailed scheme type (2020)[footnote 78]

86. An average earner saving over their career could have £3,000 more in their pension pot as a result of moving into a large master trust from a scheme with market average charges.[footnote 79] While the average annual management charge within a master trust with over 1000 members is 0.4%, employers negotiate the charges for their own employees with their master trust. During the scaling up period that we have seen over the past 5 years, competition for clients which will help the scheme reach scale quickly, is being almost purely driven by shaving off basis points on charges. Multiple stakeholders from industry flagged this issue at a recent roundtable hosted by the House of Lords, highlighting that employer drivers are based around cost, which is filtering through EBCs, who are asking schemes if they can reduce charges further as part of the selection exercise, and that this cost pressure is stifling innovation in investments.[footnote 80]

87. A few basis points can impact a members pot a great deal over the course of their savings journey and therefore in isolation, low member charges are positive for members. However, to deliver value, trustees, providers and their advisors should be considering a wide range of investment opportunities that can improve saver outcomes over the long term. A reduced investment budget both impacts on the amount a scheme can spend on investment decision making, and limits their ability to invest in assets with higher charges, which have the potential to produce greater returns. This ultimately impacts on member pots at retirement. As costs are knowable while returns are not, this is a difficult balancing act for trustees.

88. Overall, scale can open up opportunities to make more diverse investments by attracting investment managers to create sophisticated investment strategies. However, aggressive price competition could put this at risk, if a high exposure to cheap index funds were the result. It could create a negative feedback loop if there is a knock-on impact on the supply of products and services. If small investment budgets make the UK DC market unattractive to asset managers, there could be more limited investment choices for schemes, potentially limiting performance and increasing investment risk. This risk is contrary to government’s ambition for the market, where greater scale will open a diverse range of investment opportunities for master trusts.

89. To address this risk, DWP has already taken steps to encourage more diversified investments by exempting performance-based fees which meet the criteria set out in regulations[footnote 81] from charge cap calculations, and through the same legislative vehicle, new requirements are placed on schemes to include their policy on investing in less liquid assets in the scheme’s statement of investment principles, the first of which are beginning to be published. From October 2023, trust-based schemes are also disclosing the percentage of assets allocated in the default arrangement to specified assets via their chair’s statements.

90. By achieving lower charges, it is much easier for trustees and their advisers to reason that it is overall to the benefit of members to move to a master trust. For employers too, it is easier to gain buy-in from their employees if they can explain that they will be moving to a new pension scheme, and as a result the employees will pay either the same or less than they are currently paying. Although it may be slightly harder to explain that they feel confident in their choice of scheme as they believe and have been advised that higher charges offer the potential of higher returns due, effective communication by employers to their employees on this point may help further move the dial away from cost and towards value. We would encourage employers to use ‘Money Helper’, delivered by the Money and Pension Service, which offers useful guidance for individuals explaining member charges.[footnote 82]

91. We have heard from stakeholders that the decision to consider moving to a master trust is a business consideration undertaken by financial directors, and chief executive officers, often based on efforts to reduce the administrative costs of running the scheme. One of the roles of the trustee in these circumstances is to provide due diligence to ensure member interests are protected and as such trustees may not be involved in these strategic decisions at an early stage or be in a position to make a recommendation to the business, as these decisions are largely commercial. This distance has the potential to further remove member value as a consideration.

92. As part of their due diligence in scheme selection, we believe that trustees of single-employer trusts looking to move their scheme should be empowered to challenge master trusts on their pricing policies if they feel they could be detrimental to the long-term sustainability of the master trust.

93. The Office of Fair Trading, in its 2013 report on the DC pensions market, highlighted the principal-agent problem within the current system,[footnote 83] and though this report was, at that time, concerned with charges, the motivations of employers remain key for member outcomes. As employers look to discharge the burdens of governing and cost of running their own scheme, although the member is seemingly no worse off with the same or lower charges in a master trust, we must consider that those members can receive less overall investment in their pension by taking on the admin and investment fees themselves, so it is vital that they are receiving better value for what they are paying. A few employers use this cost saving to further contribute to their employees’ pots or may continue to pay the admin charges in the new arrangement, however this is believed to be in the minority of cases and would only apply to current employees.

94. A DWP qualitative research study into employers’ views and behaviours on AE and DC schemes in 2022,[footnote 84] found that employers who were choosing a pension for their employees considered issues including time and financial resource, the reputation and security of a scheme, value for members and advice or recommendations from outside bodies; and that when switching provider (an uncommon occurrence in those surveyed[footnote 85]), value was a priority. Likewise, the DWP Employer Survey 2022 asked what factors the 1,121 employers who offered DC pensions considered, and found the following results:[footnote 86]

Table 1: DWP Pensions Employer Survey 2022: What factors did you take into consideration when you chose a pension provider and scheme for your employees? (Responses from employers providing a DC pension): – multiple responses.

| Employers considering this factor | |

|---|---|

| Ease or convenience of the provider or scheme | 64% |

| Advice from a professional body, or formal advice from colleagues or other employers | 51% |

| The fees on the employer | 49% |

| The value for members | 49% |

| The value for money of the provider or scheme on the employer | 45% |

| The fees or costs on your employees | 42% |

| Scheme governance | 44% |

| Investment outcomes | 31% |

| Previous relationship with the provider | 15% |

| Informal advice from friends or family | 10% |

| Other | 2% |

| Don’t know | 7% |

95. These results demonstrate that there are a wide range of issues that employers consider when choosing a pension for their employees, and that value for members, while commonly considered, is one of many considerations. The prominence of employer fees reflects the competitive behaviour we are observing in industry shows. There will also be variation in priorities across employers.

96. We expect that VFM framework assessment results will provide a basis upon which engaged employers can decide which scheme to enrol their employees into and in reviewing whether schemes continue to best fit the needs of their employees. Adoption of a VFM approach will further help move focus away from cost alone and drive improvement by encouraging underperforming schemes to either improve their performance, consolidate, or exit the market. We have jointly proposed, with TPR and the FCA, that there will be instances where mandatory communication of VFM framework assessment results to employers from schemes will be required. When a scheme arrangement is not providing value for money, we have proposed that the employer will be made aware within a reasonable timeframe and will understand what actions the scheme intends to take to either improve the VFM offering or transfer or wind-up in savers’ best financial interest. Employers will use their discretion to act in the best interests of their workers and businesses.

Summary:

-

Competition to win business from employers is driving employer costs and member charges down (average 0.4% AMC in a master trust with over 1000 members).

-

Employers should increase their consideration of value, something which the VFM framework will help to combat.

-

Trustees should have meaningful involvement in the decision to move pension provider, to enable them to properly critique the offer.

-

Competition on cost risks limiting the available budget to spend on making investment decisions and could rule out more expensive investments.

-

However, the increasing scale of large master trust increases their ability to exert greater control over investments, and access more sophisticated strategies.

Chapter 3: Master trust consolidation

97. Significant consolidation occurred within the master trust market due to the introduction of the master trust authorisation and the regime in 2018. Further consolidation in the market is beginning to happen again. The following acquisitions have all happened in recent years and are in varying stages of the process of being merged with another master trust.

Table 2: Announcements of master trust consolidations post-2021

| Receiving or acquiring scheme | Consolidating scheme | Date of announcement |

|---|---|---|

| Cushon Master Trust (purchased The Salvus Master Trust April 2020 and launched in January 2021) | Workers Pension Trust | June 2021 [footnote 87] |

| Creative Pension Trust | January 2022 [footnote 88] | |

| The SEI Master Trust | Atlas Master Trust | October 2021 [footnote 89] |

| National Pension Trust | July 2023[footnote 90] | |

| Smart Pension Master Trust | The Ensign Master Trust | October 2021 [footnote 91] Wound up September 2023 [footnote 92] |

| The Crystal Trust | July 2023 [footnote 93] |

98. Mergers will occur in the commercial side of the market when schemes no longer feel that they will be able to attain sufficient scale to compete, and they become a target for consolidation from acquiring schemes seeking to increase their market share. In these cases, the scheme funder[footnote 94] or the funder’s ownership looks to sell the business to see some return on their investment. Master trust mergers are complex commercial negotiations. Decisions may take a long time to resolve and are likely to have commercial sensitivities. As such, we expect consolidation to happen opportunistically, and it is not possible to forecast future consolidation rates.

99. For the independent or non-commercial master trusts, consolidation is likely to be for bespoke reasons; for example, schemes which are run by employers with a DB scheme might seek to exit the market if the DB section seeks insurance buyout, and they no longer have the large governance function and scale across the scheme to support the master trust. We may see specialist schemes continue to operate even without scale, as there may not be a master trust to suit their chosen investments in line with their principles.

100. If the schemes actively pursuing an inorganic growth strategy exhaust such opportunities due to a dwindling pool of commercially attractive master trusts, then we may see this consolidation activity slow or halt for a period.

101. For the acquiring scheme, inorganic growth via consolidation brings immediate scale, in some cases close to doubling the size of the scheme by assets in a single transaction. However, it is expected that scale efficiencies will not be fully realised until schemes are fully merged. This process takes some time, but this is not necessarily negative, as it allows changes to the scheme to be made gradually, and employer buy-in to be gained from within the merging scheme. The process of merging two master trusts is approached and implemented by schemes in different ways. This can be seen in table 2, where a full merger of the Ensign Master Trust has been completed in under 12 months, compared to other mergers which are still ongoing. master trusts may choose to take their time to merge schemes, as they integrate different systems, make new appointments and change the investment strategy of the ceding scheme. But it is in schemes’ interest to merge schemes fully, to realise efficiencies and increase their scale.

102. Mergers are large projects and scheme capacity to manage these may be a factor in how often consolidation occurs. But undoubtedly, schemes who have been through this process before will learn from the experience and are more likely to be able to manage this better in future. Indeed, this experience might even form part of their bid.

103. These mergers have, so far occurred towards the smaller end of the market. Should a scheme with tens of billions in assets under management, (as is more likely to be the case as scale increases), with hundreds, or thousands of employers, look to exit the market, the size of this undertaking has the potential to cause disruption in the wider master trusts market. The regime allows for this eventuality, as schemes can be wound up into multiple schemes. However, this is not to say that operationally an exit at that level would not be very challenging.

104. The total cash consideration payable to XPS (sponsor of National Pension Trust) upon completion following regulatory approval is up to £42.5 million, comprising of £35 million initial consideration and the potential for up to £7.5 million in addition based on business performance over two years. [footnote 95] For this, SEI have purchased a scheme of 60,000 members and £1.5 billion in assets under management.[footnote 96] At a greater scale, Cushon, themselves an active consolidator, was acquired by Natwest Group in June 2023 for £144 million (for 85% of Cushon).[footnote 97] We can expect these sorts of prices to increase, as scale continues to grow within the market.

105. Natwest and HSBC both identified opportunities to enter the market, inorganically and organically respectively. Banks have the financial strength to acquire established master trusts, and the more recent Natwest/Cushon example highlights the potential appetite within the banking sector to enter the market in this way. Whereas HSBC entered organically, setting up their own master trust, and subsequently decided to exit.

106. Organic growth is achieved by winning business from employers (as discussed in chapter 2). Winning this business also has costs attached in using resources to attract new business, and project costs to onboard schemes. Schemes pursuing inorganic growth strategies must weigh up the costs of organic vs inorganic growth, to determine if a purchase is in their best interest, or whether they should pursue organic growth only. This is another reason why large employers represent high value for master trusts, as schemes can increase their membership without the full costs of purchasing a scheme.

107. Depending on the circumstances, some mergers may cause a triggering event.[footnote 98] The triggering event sets into train a series of actions which give TPR greater oversight and member protection, wherein the ceding scheme must set out an implementation strategy to be approved by TPR, following which, the scheme is required to report regularly to TPR until the triggering event is resolved. For the duration of the triggering event period, the ceding scheme must not take on any new employers, and employer or member communications must be sent out to explain this process.

108. The triggering event and continuity options were designed to manage exits where there was a failure of governance or where the scheme failed to meet other authorisation criteria. The dynamic of the market has now changed, where financially stable schemes are seeking to exit via mergers. To signal that mergers can be positive, there may be a need to investigate whether a new triggering event and/or an additional continuity option is required which more appropriately fits the circumstances of mergers we are seeing rather than the market exits we expected to see when the regime was designed.

109. Likewise, some mergers happen outside of the parameters of the triggering events as set out in the Act meaning there is no formal notification to TPR. For example, where a consolidator purchases the scheme funder of a ceding scheme (usually the entity controlling the scheme), the ownership of the scheme funder has changed but the scheme funder’s relationship with the scheme has not changed. TPR remains engaged with ceding schemes to ensure that authorisation criteria continue to be met, but, unless the acquiring entity itself falls within the legal definition of scheme funder (i.e. it is contractually obliged to meet the costs or receive profits directly from the master trust), which brings the merger under a triggering event, TPR have no legislative grip over the acquiring entity in terms of financial sustainability, fitness and propriety, and systems and processes. Based on recent operational experience, TPR see this as a key risk which may increase if master trusts businesses, once consolidated at scale, are subsequently sold on to other investors – for example, you may have a master trust business acting a cross guarantor for significant acquisition debt but with TPR having very little grip over the ultimate owners. This risk, and the fact that regulatory oversight of a merger is almost randomly determined by this arbitrary way of distinguishing the motivation behind a transaction is another reason we may wish to revisit this legislation in due course.

110. As part of the broader regulatory framework relating to financial services sector, any decision to acquire or increase control of an FCA-authorised firm should be communicated to the FCA for the purpose of obtaining prior FCA approval. This means that FCA approval must be obtained prior to a proposed acquisition of an FCA-authorised firm sponsoring a master trust. Prior approval must also be obtained from the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) where the firm is also regulated by the PRA, who will consult with the FCA as part of their assessment. The assessments are of the suitability of the proposed controller against criteria set out in FSMA.[footnote 99]

Conflicts of interest