Value for Money: A framework on metrics, standards, and disclosures

Updated 25 July 2023

Ministerial Foreword

Following the success of Automatic Enrolment, record numbers of hard-working people are now saving for their retirement. It is vital they have confidence that their pension delivers value for money. Driving a long-term focus on value for money across the pensions sector is a key priority for this Government. This consultation marks a significant step in that journey and is the culmination of joint work between the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP), The Pensions Regulator (TPR) and the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). It sets out a transformative framework of metrics and standards to assess value for money across Defined Contribution (DC) pension schemes.

Ensuring that pension schemes deliver value for money doesn’t just mean low costs and charges. It also means that savers get good value from their investments and receive a quality level of service.

Improving the availability and transparency of information and data on these key factors will enable schemes to compare and improve the overall value for money they provide, driving competition across the market. In addition, it can improve performance and help drive consolidation by removing underperforming schemes from the market.

We have listened to industry and taken on board responses provided to TPR and FCA’s discussion paper (September 2021). We are grateful for the support we have received from industry in shaping this policy consultation.

We do not believe that requirements to disclose and assess additional information should be unduly burdensome. We want to ensure that any regulatory requirements of a Value for Money (VFM) framework are proportionate to the benefits that increased value for money brings savers.

We want to deliver good outcomes for those saving for retirement through policy that works in practice for the pensions market, whilst maintaining a focus on value for money for pension savers. This framework is designed to ensure that member outcomes are front and centre when decisions about people’s savings are made.

Mel Stride MP

Secretary of State for the Department of Work and Pensions

Laura Trott MP

Minister for Pensions

The Pensions Regulator Foreword

Delivering value for money in pensions is a key priority for TPR – all part of our work to put savers at the heart of what we do. Regulators, industry and others must be able to effectively assess value for money to ensure good pensions outcomes. The consultation sets out our ambitions for an industry-wide VFM assessment framework.

DC savers rely on the pension system working as best as it can over the lifetime of their saving - every penny counts. The vast majority of savers do not choose or engage with their pensions, and the system is effectively built and driven by inertia. For this reason, we think that those responsible for providing oversight of value should be supported in their focus on what matters most for pension saver outcomes. Under existing measures, it is not possible to accurately scrutinise schemes to compare value relative to others on the market. That is why trustees need a framework which provides a holistic assessment of what VFM means to allow them to hold their providers to account and deliver the best possible outcomes for savers. We believe that a system driven by inertia must ensure that all savers receive value for money by default.

We are determined to drive a long-term focus on value for money across the pensions sector by focusing on driving transparency, comparability, and competition. Over the last two years, we have been working closely with the FCA and the DWP to establish a common assessment framework. This proposed framework will allow comparisons between different schemes’ costs and charges, investment performance and service standards. Underperforming schemes that are unable to make improvements are likely to exit the market, thereby improving its efficiency.

We think the time is right to encourage a more consistent and structured approach to VFM assessment that drives long-term value for pension savers.

David Fairs

Executive Director, The Pensions Regulator

Financial Conduct Authority Foreword

Consumer outcomes are at the heart of the FCA’s regulatory strategy and the new Consumer Duty which requires firms to act to deliver good outcomes for retail customers. Ensuring that schemes and firms deliver good outcomes for pension savers is critically important and that’s what these proposals aim to deliver.

It is clear that value for money is not just about costs and charges. These proposals will help ensure that schemes deliver against value for money in the round. Transparent and consistent disclosure of the key elements of value for money will better identify underperforming schemes. We know that most workplace savers don’t engage with their pension and must trust the system to deliver value for them. Where a scheme is assessed as being poor value for money – with objective assessments – we will expect a provider to take action so that a pension saver can never be in an underperforming scheme for long.

To achieve long-term improvements in the way the market functions, it is also vital that competition works in the interests of pension savers. This new VFM framework will help shift the focus of competition away from short-term cost to long term value for savers, and ultimately better retirement outcomes. It will encourage schemes and providers to take a longer-term view on the types of investment they build into their default designs.

This joint work of government and the regulators means that the same proposals apply across the DC market. That will enable consistent and comparable assessments regardless of the type of scheme a workplace pension saver is in. It builds on the joint FCA/TPR regulatory strategy and the work we have done together on the pensions consumer journey.

It is hugely important that the industry, consumer groups and other stakeholders continue to be part of our joint work to make the VFM framework as effective as possible. While our focus at this stage is on workplace defaults, we have clearly signalled our intention in the future to consider extending the framework to workplace self-select options, non-workplace pensions and pensions in decumulation.

Sarah Pritchard

Executive Director of Markets, Financial Conduct Authority

Introduction

This consultation seeks views on policy proposals to require trustees and managers of defined contribution (DC) relevant occupational pension schemes and the providers and Independent Governance Committees (IGCs) of workplace personal pension schemes to disclose, assess and compare the value for money their workplace pension scheme provides.

This policy seeks to improve retirement outcomes for millions of defined contribution pension savers. By promoting a focus on transparency, competition, and innovation, these proposals aim to ensure that savers are receiving optimum value for money and that investments by trustees and providers are in the best interests of savers.

Roles and Responsibilities

The Department for Work & Pensions (DWP) is responsible for pensions policy in the UK. Our policies aim to ensure that the pension system provides the financial security that savers need in later life.

Regulation of the pensions industry in the UK is split between the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA)[footnote 1] and The Pensions Regulator (TPR)[footnote 2].

The FCA regulates personal pensions in the UK, including workplace personal pensions, and regulates the conduct of around 50,000 firms in the UK to ensure that markets work well. The FCA supervises firms to make sure they continue to meet its standards and rules after they are authorised. If firms and individuals fail to meet these standards, the FCA has a range of enforcement powers it can use. The FCA has rule making powers set out in legislation. All FCA regulated firms must comply with its rules as set out in the FCA Handbook. The FCA’s operational objectives are to protect consumers, maintain market integrity and promote competition in the interests of consumers.

TPR regulates occupational pensions in the UK. TPR’s statutory objectives are: to protect savers’ benefits; to reduce the risk of calls on the Pension Protection Fund (PPF); to promote, and to improve understanding of, the good administration of work-based pension schemes; to maximise employer compliance with automatic enrolment duties; and to minimise any adverse impact on the sustainable growth of an employer (in relation to the exercise of the regulator’s functions under Part 3 of the Pensions Act 2004 only).

About this consultation

Who this consultation is aimed at:

- DC pension scheme trustees and managers;

- Independent Governance Committees (IGCs) of workplace personal pension schemes

- Providers of workplace personal pension schemes

- DC pension scheme savers and beneficiaries;

- pension scheme service providers, other industry bodies and professionals;

- employers

- civil society organisations;

- consumer organisations / representatives with an interest in pensions capability / financial capability;

- pensions administrators; and

- any other interested stakeholders

Purpose of the consultation

This consultation seeks to gather views and evidence on the metrics, standards and public disclosure of data required under the proposed Value for Money (VFM) framework and the proposed use of this data in comparisons and assessments of VFM.

Scope of consultation

This consultation applies to Great Britain (England, Scotland and Wales). Occupational pensions are a devolved matter for Northern Ireland, and it is envisaged that Northern Ireland will make corresponding provisions.

Duration of the consultation

The consultation period begins on 30 January 2023 and runs until 27 March 2023. Please ensure your response reaches us by that date as any replies received after that date may not be taken into account.

How to respond to this consultation

Please send your consultation responses on the template provided via email to: Value for Money Team: DC Policy

Email: pensions.vfmframework@dwp.gov.uk

Your response will be shared with the FCA and TPR. In addition, your response will not be treated as confidential unless you specifically request otherwise. When responding please indicate whether you are responding as an individual or representing the views of an organisation.

Our response

We will aim to publish the government response to this consultation on the GOV.UK website. The report will summarise the responses and set out the Government’s proposed next steps, taking account of the responses.

How we consult – Consultation principles

With our proposals, we want to achieve common standards across all defined contribution (DC) pensions. Therefore, this is a joint consultation. However, due to the differing legal form of different types of pensions, and our differing respective remits, the ultimate requirements to be developed will be set out separately, albeit with common outcomes in mind. Through this consultation, DWP, TPR and the FCA are seeking views to inform development of their respective requirements, as well as the common outcomes we seek to achieve. Our proposals and questions in this joint consultation paper apply to both occupational pension schemes (regulated by TPR) and workplace personal pensions (regulated by the FCA) unless stated otherwise. All references in this paper to our proposals and questions should be read accordingly and by reference to how each body may then take the proposals forward: i.e. DWP and TPR in relation to occupational pension schemes and the FCA in relation to personal pension schemes.

This consultation is being conducted in line with the revised Cabinet Office consultation principles published in March 2018. These principles give clear guidance to government bodies / departments on conducting consultations.

An FCA consultation would typically contain proposed rules, but the FCA is not consulting on specific rules at this stage. The FCA expects to conduct a further consultation with proposed changes to FCA rules, taking account of responses received to this paper. DWP also expects to conduct a further consultation with proposed changes to regulations. References to consultation principles relevant to the Government apply only to the Government. The FCA’s principles for consultation follow, among other things, the Legislative and Regulatory Reform Act and general public law requirements.

Feedback on the consultation process

We value your feedback on how well we consult. If you have any comments about the consultation process (as opposed to comments about the issues which are the subject of the consultation), including if you feel that the consultation does not adhere to the values expressed in the consultation principles or that the process could be improved, please address them to:

DWP Consultation Coordinator

2nd Floor

Caxton House

Tothill Street

London

SW1H 9NA

Email: caxtonhouse.legislation@dwp.gsi.gov.uk

Data protection and confidentiality

For this consultation, we will publish all responses except for those where the respondent indicates that they are an individual acting in a private capacity (e.g. a member of the public). All responses from organisations and individuals responding in a professional capacity will be published. We will remove email addresses and telephone numbers from these responses; but apart from this, we will publish them in full. For more information about what we do with personal data, you can read DWP’s Personal Information Charter.

Chapter 1: Background and rationale

1. This consultation sets out proposals to introduce a Value for Money (VFM) framework and regulatory regime covering DC pension schemes. The framework looks to ensure that schemes deliver the best possible value and better long-term outcomes for pension savers.

2. The proposals within this consultation encourage greater transparency and standardisation of reporting across the DC pension market, allowing trustees to make more informed investment and governance decisions and employers to better compare the value and performance between DC schemes when choosing where to automatically enrol their employees.

3. Encouraging a cultural shift across the DC pensions market from focussing on cost to overall value will also encourage market consolidation, allowing more schemes to benefit from the economies of scale. This would give them the opportunity to invest in more diverse asset classes, diversifying members’ portfolios, lower running costs and potentially providing higher investment returns.

4. Value for money was identified as a key priority in the joint regulatory strategy published by the FCA and TPR in October 2018. In September 2021, TPR and the FCA published a Value for Money (VFM) discussion paper[footnote 3]. This paper invited views on developing a holistic framework and metrics to assess VFM in regulated DC pension schemes as part of a future regulatory regime. TPR and FCA released their feedback statement on the responses received to the discussion paper on 24 May 2022[footnote 4].

5. DWP, the FCA and TPR are working together to develop a VFM framework and regulatory regime. This framework is intended to provide a standardised understanding of value via clear metrics, allowing more transparent comparisons to be made between pension schemes and driving more effective competition.

6. We welcome continued engagement and support from the pensions industry and consumer groups on this subject. The insights and contributions we have received have helped us to shape the proposals included in this consultation. We are also grateful for stakeholder recognition of the benefits a VFM regime can bring in helping deliver stronger outcomes and in shifting the focus away from low cost to improving long term value for savers.

7. We accept this is a complex area with mixed views on certain aspects of the framework. This consultation seeks to move this debate forward and we hope these proposals enable informed and constructive discussions as we work towards finalising a regulatory regime.

1.1. Defining Value for Money

8. ‘Value for Money’ is a concept that is currently interpreted in varying ways by different market participants. For the purposes of this consultation, we consider ‘Value for Money’ to mean that pension savers’ contributions are well invested in the best interests of savers, and savings are not eroded by high costs and charges in the context of the market today.

9. Customer service and scheme oversight also contribute to whether a saver achieves good retirement outcomes and so are included in our concept of ‘Value for Money’. For example, good customer service to help savers make the right decisions at the right time, may make a real difference to how much they contribute and engage with their retirement needs.

10. In our view, the key elements of the VFM framework are:

- Investment performance;

- Costs and charges; and

- Quality of services

1.2. Rationale for Intervention

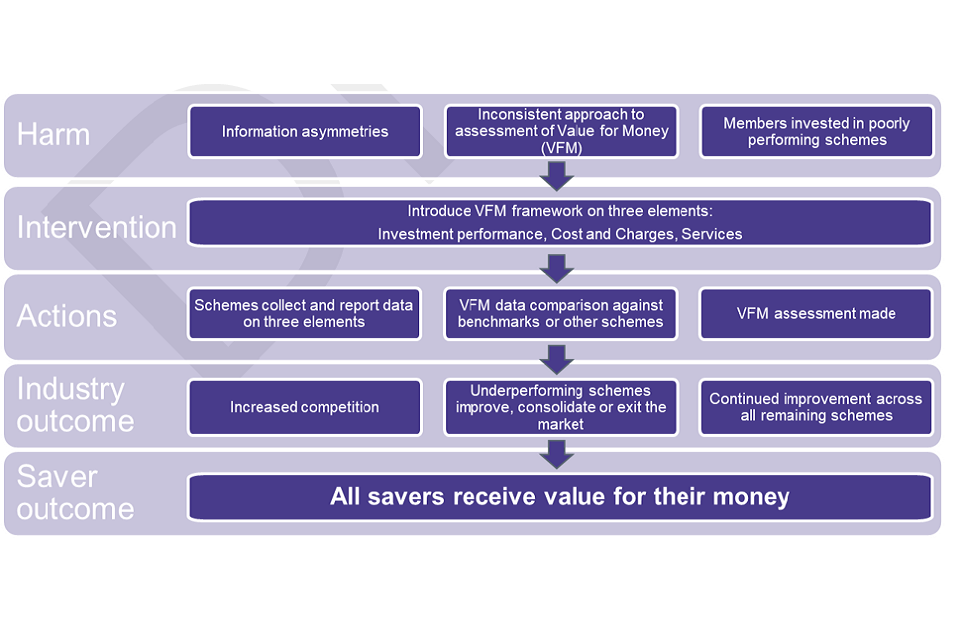

11. The need for regulatory interventions in the pensions market arises from a combination of challenges in the existing pension market shown in the figure below.

Figure 1: VFM Causal Chain

VFM Causal Chain

This figure shows how the existing pension market can make it difficult for DC pension schemes to assess the value for money (VFM) pension savers receive. It shows how the VFM framework proposes to change this – through targeted actions such as the reporting of schemes’ key data on three elements: investment performance, costs and charges and quality of services; and the publication of VFM assessments. Industry outcomes, such as increased competition and underperforming schemes improving, consolidating or existing the market are expected. We expect this will result in all pension savers receiving value for their money.

Current focus on costs

12. Engagement with stakeholders and responses to the pension charges survey[footnote 5] shows that considerations of cost can dominate decision-making in many pension schemes, especially with some contracts now being won or lost over very small differences in cost. While costs are important, too much emphasis on cost can be detrimental to savers.

13. The VFM framework aims to shift the focus from cost by considering other factors that feed into overall VFM and are important for long-term outcomes. This will enable a more holistic and informed view of the value that pension schemes provide.

Limited transparency and low comparability

14. Limited transparency around the performance of pension products can make it difficult to access the information needed to inform decision making and compare the value delivered. This has contributed to inconsistent approaches to assess value and subjective decision-making. We know that some IGCs are less effective than others and we are also concerned that some trustees may have lower standards in assessing value in comparison to others[footnote 6].

15. The VFM framework is designed to change this by providing consistent value metrics and a transparent approach to assess and compare the overall value and performance offered by schemes across the pensions industry. Greater transparency will raise awareness of the VFM delivered and help increase comparability leading to better outcomes for pension savers.

16. Without fair comparisons, there cannot be effective competition. We expect the VFM regime to drive improvement by encouraging underperforming schemes to improve performance, consolidate or exit the market; and for all schemes to use the disclosures to understand best practice. Over time, this will create an environment that leads to continuous improvement, healthy competition, and innovation throughout the DC pensions industry.

17. Increased transparency in the DC market will also aid employers when in the process of deciding which scheme they should enrol their employees into. The VFM disclosures would allow them to gain easier access to clear and standardised comparisons of value offered by schemes.

International Evidence

18. The UK is not the only pensions market facing these challenges. Other jurisdictions have taken steps to enhance transparency and improve value for money in their pension offering.

19. For example:

- In New Zealand, pension providers are required to assess member fees against performance on qualitative criteria, resulting in a significant reduction of fees[footnote 7]

- In Australia, the introduction of the annual performance test in 2021 is credited with contributing to over 5.1 million MySuper members (just over 38%) now paying lower fees than they were last year[footnote 8]

Chapter 2: Interaction with the wider policy framework

20. This chapter sets out how the VFM framework complements and builds on wider policy disclosure requirements and initiatives across occupational and contract-based pension schemes.

2.1. The VFM framework and consolidation

21. The overall aim of the VFM framework is to drive better outcomes in DC pensions and increase the value delivered to savers. Greater scale of pension schemes can mean greater opportunity and potential to deliver holistic value for savers. Our intention is for the framework to drive and support the further consolidation of pension schemes, where this is in the best interests of savers. We are also considering whether TPR should have new powers to enforce wind up and consolidation where a scheme is consistently not offering value for its members.

2.2. The VFM framework and Value for Members assessment

22. In October 2021, regulations came into force requiring occupational DC schemes with less than £100m in assets under management to complete a more detailed Value for Members assessment[footnote 9]. The purpose of completing this assessment is for schemes to determine whether savers will receive optimal value in their existing scheme over the long term, or whether savers could achieve better value in a different scheme. Underperforming schemes are encouraged to consolidate to a larger occupational pension scheme or set out the immediate action they will take to make improvements.

23. The VFM framework intends to build on, and in time, replace the value for members assessments by requiring all occupational pension schemes to report on wider value metrics and use this data to assess the value of their offering against market comparisons.

24. Our expectation is that, over the next few years, schemes of under £100m in assets not offering VFM will have either wound up, be in the process of winding up or will have made improvements and therefore consider themselves to offer VFM. When the VFM framework comes into force, we will expect those schemes with under £100m in assets under management that consider themselves to be VFM, to move to the VFM framework in order to carry out their annual assessments.

25. Where the Value for Members assessment encourages schemes to improve or consolidate into a better performing scheme, we are considering whether the VFM framework could place a statutory requirement on trust-based occupational pension schemes to consolidate following repeated ‘underperforming’ assessment results, where this is in the best interests of savers. We are considering a related requirement in FCA rules on contract-based providers to improve or consider transferring savers, where this is in the best interests of savers.

2.3. The VFM framework and Deferred Small Pots

26. Automatic enrolment (AE) has made workplace pension saving the norm for many workers, including low/median earners and those who move jobs frequently. However, this has resulted in individuals accumulating multiple deferred small pension pots over their working life.

27. The growth of deferred small pots creates costs and inefficiencies in the AE workplace pensions market, which could be passed on to members. It increases the risk that scheme members lose track of their workplace pension savings – acting as a disincentive to member engagement and later life planning. Alongside this, the growth of deferred small pots means some members with larger pension pots will effectively be cross-subsidising administration costs, which may impact on their own returns. Some providers may find that the costs of managing large numbers of deferred small pots outweigh the amount they receive in charges, threatening their longer-term financial sustainability.

28. To address the growth of deferred small pots and the challenge that this presents to VFM, DWP published a call for evidence seeking views and evidence on the optimal large-scale automated solution that can deliver a material reduction in small pots and overall net benefits for savers[footnote 10]. The VFM framework will complement this work by strengthening the governance that applies to schemes. A meaningful reduction of deferred small pots will improve outcomes for members and providers by removing inefficiencies and wasted administration costs.

2.4. FCA Consumer Duty

29. The FCA has introduced a Consumer Duty (FCA Principle for Business 12) which requires firms to act to deliver good outcomes for retail customers. FCA regulated providers will have an obligation under the Consumer Duty[footnote 11] to consider the value of the pension products they offer, as well as other outcomes. Providers with occupational pension schemes as clients will have to consider whether they can determine or materially influence member outcomes, since the Consumer Duty will apply to the extent that they can, for example in relation to member understanding or support.

30. We consider that proposals for disclosure of VFM metrics and a more structured and comparable approach to VFM assessments by IGCs are consistent with the Consumer Duty and its aims of the setting higher and clearer standards of consumer protection across financial services and requiring firms to put their customers’ needs first. The publicly disclosed data and focus on pension saver outcomes will also support firms in meeting their obligations under the Consumer Duty.

31. For workplace personal pension schemes specifically, the VFM assessments carried out by IGCs are embedded in FCA rules for the Consumer Duty. A provider must use its IGC’s VFM assessment in the provider’s own value assessment. Where a provider disagrees with its IGC’s assessment, the provider must explain why, and set how it considers that the scheme provides fair value, using the assessment framework for IGCs.

Chapter 3: Scope, criteria, and outcomes

32. This chapter sets out the proposed scope, criteria and outcomes of the VFM framework, building on TPR and FCA’s discussion paper and wider engagement to date with stakeholders and experts.

3.1. Scope and intended audience

33. We propose a phased approach to implementation, learning from the successful introduction of automatic enrolment. This will give us the opportunity to test and learn and build the trust and confidence of industry and savers.

Phase 1

Scope

34. The growth of AE, with 96% of pension savers invested in a pension scheme’s default investment strategy (for non-micro schemes)[footnote 12] makes it essential these provide long-term value in the accumulation phase. Therefore, we propose the VFM framework applies to “default arrangements”, as defined in regulation 1(2) of the Occupational Pension Schemes (Investment) Regulations 2005[footnote 13] and “default arrangements” as defined in the FCA Handbook[footnote 14].

35. We do not think it is proportionate to apply the framework to default arrangements with very small numbers of savers invested or assets under management below a particular threshold, including some defaults that can arise when savers are moved after contributions to some investments are suspended.

36. We propose legacy schemes,[footnote 15] to also be in scope. Some of these schemes charge significantly more than more modern schemes, as identified in an independent audit in 2014[footnote 16]. Following work by the industry, with further reviews by the FCA and DWP[footnote 17], industry took action to bring possible charges down to 1% or less. While a significant benefit to pension savers, even this lower level of charges does not necessarily bring members value as VFM in legacy schemes needs to be assessed holistically.

37. We propose to include pension arrangements where 80% or more of pension savers were enrolled. This approach mirrors that used to identify defaults for the purposes of the regulatory charge cap for AE schemes.

38. We propose to exclude Small Self-Administered Schemes (SSAS) and Executive Pension Plans (EPP). These micro schemes have members who are more engaged with decisions around investments and are typically advised. They may have less need for the VFM framework. We also consider that it would not be proportionate in this phase to apply the VFM framework to these micro schemes given the cost to them.

Intended audience

39. At this stage, we propose the VFM framework is targeted at the professional audience and decision makers (including trustees, IGCs, providers, and other industry professionals) who oversee workplace default arrangements, used both for AE and other workplace schemes.

40. We expect employers to use VFM assessment results when deciding which scheme to automatically enrol their members into, or when considering whether the pension scheme their employees are in continues to provide value for money to their employees.

Phase 2

Scope

41. While starting with default arrangements of workplace pensions, our intention is to extend the framework more widely. We propose to consider extending the framework to cover self-select options, non-workplace pensions and DC pensions in decumulation in phase 2.

Intended audience

42. We envisage that the pensions sector will evolve as the VFM framework is embedded. For example, over the longer term, industry tools may emerge to enable greater market comparability and we expect the VFM framework to reflect these industry developments over time.

43. With the future launch of pensions dashboards, we expect increased pension saver engagement. While we do not expect pension savers to engage with the detail of the value metrics, we expect savers to take increasing interest in the VFM delivered by their scheme.

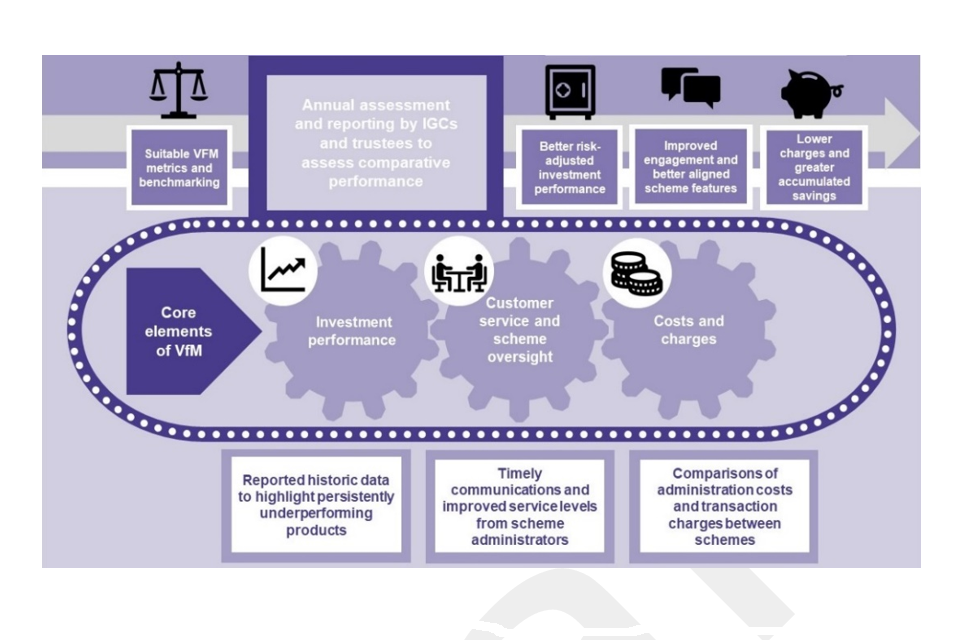

Figure 2: Proposed VFM framework

Proposed VFM framework

This figure shows how the data disclosure of the core elements of the VFM framework (investment performance; costs and charges; quality of services) and reporting of annual VFM assessments, would enable better investment performance, lower charges and improved saver engagement across DC pension schemes.

Consultation question

Q1: Do you agree with the proposed phased approach?

3.2. Criteria for the VFM framework

44. Transparency was identified a key criterion for effective decision-making in the Discussion Paper. Our proposed VFM framework will provide market-wide transparency and has been designed to meet the following criteria:

- A clear driver of saver outcomes: Ensuring savers achieve good long-term retirement outcomes is the overarching objective of the VFM framework.

- Comparable: Comparisons across the pension industry is essential if schemes are to accurately assess the value of the offerings.

- Drive continuous improvement: trustees, providers and IGCs will be required to identify and act on areas of underperformance, learn from best practice or new opportunities to innovate.

- Minimise opportunity for providers to ‘game’ the system: A consistent and standardised approach of VFM framework provides transparency thus minimising opportunities to ‘game’ the system.

- Minimise costs and burden to industry, regulators, and employers: While we recognise that additional disclosures could come at a cost to schemes, we aim to ensure these are proportionate.

- Consistent with other policy initiatives: Over the past few years government, regulators and industry have taken important steps to place VFM at the centre of pensions policy. The VFM framework aims to build on existing policy initiatives and help drive forward further changes in an evolving pensions landscape.

3.3. Outcomes

45. The overarching aim of the proposed VFM framework is to improve the value savers get from their DC pension. It will take time to be able to measure this outcome. In the short term, other measures may act as a useful proxy to evaluate the effectiveness of the regulatory changes: switching of schemes by employers, or better negotiated terms, for example.

46. We propose that these outcomes will be delivered by trustees of pensions schemes and by providers with IGCs using a mandatory regulatory framework to assess their VFM. By requiring pension schemes to disclose consistent metrics, the VFM framework will equip governance bodies and the people who advise them with the information they need to understand how their offerings compare with those of other schemes and encourage competition on the quality of these offerings.

47. Comparisons will enable underperforming pension schemes to focus on areas where they need to improve as well as give trustees and IGCs the information they need to challenge poor performance.

48. Under the proposed framework, pension schemes that do not deliver VFM would be accountable to the regulators that could take action, where considered necessary. This is explored further in Chapter 8.

3.4. Market Structural Differences

49. Proposals in this consultation paper aim to drive improvements in VFM across the DC workplace pensions market. However, there are important differences in market structure and to whom the proposals would apply, depending on the type of pension in question.

50. For trust-based occupational pension schemes, trustees would be expected to assess the VFM of their scheme and make decisions on actions that would improve VFM. The proposals in this paper are directly relevant to trustees and their advisers.

51. For workplace personal pension schemes, which are contract-based, an IGC must independently assess the VFM of the scheme. Under FCA rules, every provider of a workplace personal pension scheme must have an IGC, which acts solely on behalf of pension savers. The provider is required to take reasonable steps to respond to any concerns raised by the IGC and must provide written reasons where it departs in any material way from an IGC’s advice or recommendations. Under the FCA’s Consumer Duty, FCA-authorised firms will be required to carry out value assessments. IGC assessments are embedded in this since a provider must use the IGC’s VFM assessment in its own value assessment.

52. In this joint consultation paper, any reference to IGC is also a reference to Governance Advisory Arrangement (GAA) unless stated otherwise. A GAA is a proportionate alternative to an IGC for providers with smaller and less complex workplace personal pension schemes.

Chapter 4: Investment performance

4.1. Objectives of our proposals

53. This chapter sets out the investment performance metrics for proposed public disclosure. Our primary focus is on factual, historic information showing the past value delivered to pension savers. We are therefore proposing disclosure of backward-looking investment performance, net of all costs across a range of time periods and age cohorts. This central dataset would be supplemented by simple risk-adjusted metrics to indicate the level of risk borne by pension savers in achieving the reported returns. In addition, we propose disclosure of a simple forward-looking metric for target future performance.

54. In determining what investment performance metrics to require, we have the following objectives:

a. Reflecting member outcomes

b. Enabling meaningful comparison

c. Supporting assessment of investment strategies

d. Allowing consideration of expected future performance

4.2. Backward-looking returns, net of all costs

55. We propose disclosure of backward-looking returns to help trustees, providers, IGCs and their advisers compare and understand the drivers behind scheme outcomes and identify under-performance. While past performance is not always an indicator of future performance at the level of individual funds, there is a strong empirical correlation between past and future returns by asset class. In addition, the proposed disclosure of a forward-looking metric would reflect any changes to investment strategy reflected in current design.

56. In our view, performance data is most useful when reflecting member experience. Therefore, we are proposing that investment performance should be disclosed net of all costs and charges, including transaction costs and performance-based fees. Where charges are monthly, we think a sufficiently accurate approach would be to net out the charges on an annual basis. Mutual companies would take account of profit share with a corresponding reduction in costs and charges.

57. We plan to address further detail of what we would expect to be calculated and disclosed in a subsequent consultation(s) on regulations and FCA rules. We would welcome views to help us with that.

Employer subsidies

58. Where a sponsoring employer undertakes to pay certain costs or charges of its workplace pension scheme on behalf of its employees, this has the effect of improving the apparent investment returns net of all charges.

59. Therefore, our initial proposal is that investment performance should be disclosed net of the sum of member-borne costs and charges and all costs paid by an employer to a scheme or pension provider. This would allow comparisons of net investment performance to be carried out on a like-for-like basis.

Legacy schemes

60. Default arrangements in legacy schemes may have valuable guarantees which affect their overall VFM, such as a guaranteed investment return or a guaranteed annuity rate. We propose that all VFM metrics should apply to funds with guarantees but that the scheme’s disclosure should contain a short qualitative statement indicating the nature of the guarantee, or any other feature which should be taken into account in comparisons.

61. Some legacy schemes may have a default arrangement that is a with-profits fund. Our initial thinking is that VFM metrics for investment performance should be computed using the annual bonus rate declared to pension savers and any other one-off additions to asset share during the period (based on the proceeds of a disposal or similar).

62. The average of any loyalty bonus would be used to compute a corresponding reduction in the costs and charges set against investment performance.

4.3. Reporting periods, granularity and age cohorts

Reporting returns in ranges for cohorts rather than individual employer level

63. Many pension schemes are set up in a way that they effectively offer a range of terms and conditions for different clients. Requiring multi-employer schemes to report investment returns net of all costs for each individual employer could result in very large data disclosures being produced.

64. We therefore propose that employers be grouped into employer cohorts for disclosure of data, for the purposes of proportionality and simplicity. In determining what those cohorts should be, we want to enable consistent comparisons between multi-employer schemes.

65. We propose cohorts based on assets under management, with a number of prescribed bands of assets under management, from the lowest to the highest. Each scheme would divide up its employers into these bands and report net returns for each band. We are also considering an alternative or additional disclosure against bands based on the number of pension savers for an employer. This is similar to the approach already used by IGCs, where each provider with its IGC discloses data by bands, both for assets and number of savers, to a third party acting as the central hub and compiler for comparison purposes.

66. For each band, net returns would be disclosed as the range for that cohort as well as the average. To exclude outliers, we could require disclosure of the range of net returns for the employers representing the middle 80% within the cohort. This would exclude the bottom 10% and top 10% of net returns.

67. An alternative and simpler approach to prescribed bands would be to require schemes to divide employers into their own quartiles or deciles, with the same number in each cohort. A scheme would rank employers by assets under management, and then divide them up, with net returns disclosed as above. While this would avoid the need for prescribed bands, it would also reduce comparability, since the asset bands would be different for one scheme versus another.

Reporting periods

68. Investment returns need to be evaluated over appropriate periods of time. Short-term performance data may reflect market volatility rather than the quality of a firm’s investment strategy.

69. For reporting periods, we propose disclosure of annualised returns net of all costs for 1, 3 and 5-year periods, and 10 and 15-year periods, if the data is available. This builds on DWP’s existing guidance for schemes but with an additional data point for returns over 3 years and without the 20-year period.

70. For comparability, we think all returns data should be reported to the same end date in time. Otherwise, recent market volatility may make a significant difference to reported returns depending on the end date used, even for returns over longer time periods. This issue is explored further in Chapter 7.

Age cohorts

71. It is common for schemes and providers to automatically adjust the asset mix of the default through the pension saving journey to reduce investment risk for savers nearing retirement. This can affect the investment performance of default arrangements for savers at different ages.

72. Existing DWP statutory guidance sets out how relevant occupational pension schemes should report performance at ages 25, 45 and 55[footnote 18]. We propose to extend this approach to all workplace schemes in scope of this consultation. However, because we recognise that there are risks of value erosion during the final years leading up to retirement, we are considering an additional requirement for providers to report investment performance at one day before state pension age (SPA). This is also in line with the proposed draft guidance for “disclose and explain” disclosures set out by DWP[footnote 19].

73. Schemes and providers would be expected to report net investment performance for each of the periods going back in time for each age cohort. For example, schemes would be expected to report the annualised return net of all costs over the previous 5 years, based on the investment strategy and asset mix adopted for savers at the ages 25, 45, 55 and one day before SPA during this period.

Consultation question

Q2: Do you agree with our focus on and approach to developing backward-looking investment performance metrics?

4.4. Risk metric alongside reported net returns

74. The disclosure of net investment returns without risk adjustment could hamper comparability of performance, be misleading or incentivise excessive risk-taking. We therefore believe that it is important to consider requiring disclosure of the degree of risk associated with reported investment performance.

75. We recognise that a range of approaches can be taken to prescribing a standardised approach to assessing the risk associated with investment performance. For example, the DWP’s statutory guidance suggests net investment returns are presented as an annual geometric average but allows schemes to show risk-adjusted returns where it would be helpful to do so.

76. For the VFM framework, we are proposing the disclosure of two specific risk-adjusted metrics to be reported alongside net returns. These are maximum drawdown and annualised standard deviation (ASD) of returns. Both would be reported on a backward-looking basis for each of the age points and reporting periods set out above.

77. Maximum drawdown provides an easily understood, tangible, meaningful measure of the risk associated with the default strategy. It facilitates easy comparison between strategies and outcomes associated with specific stressed market events. Users could quickly gain insight into the scale of the value at risk profile of a strategy and quickly understand how it could perform if certain conditions repeated themselves in future, prompting a more thorough review and analysis of the risk profile of the strategy. We are proposing disclosure of best and worst drawdown data over discrete 3 months, 1, 3, 5 and 10-year periods on an historic basis at each age cohort.

78. ASD is a well understood readily used metric, likely to be familiar to most pension professionals, regularly used in comparative performance data and is currently used in the production of projections for annual benefit statements. We recognise that ASD may be less effective as an accurate indicator for private market and alternative investments, however, it enables users to easily consider relative risk adjusted returns across multiple strategies to assess the relative risk profile of their default strategy in relation to a wide range of benchmarks and their competitors.

Consultation question

Q3: Do you agree with our proposals to use Maximum Drawdown and/or ASD as risk-based metrics for each reporting period and age cohort?

4.5. Chain-linking

79. Where changes to portfolio composition or strategy occur within a reporting period, we still want schemes to report meaningful and comparable information about their investment performance and outcomes for pension savers.

80. We are considering requiring schemes and providers to track the investment returns experienced by the broad group of savers in the default when it was initially set up, rather than tracking the investment returns corresponding to the product’s current investment strategy. In practice, this means we would want schemes to apply a ‘chain-linking’ methodology whenever it calculates the net investment returns over time.

81. Where one group of savers are moved and merged with those from another default offered by the same provider or scheme, we expect the reported returns of the combined group to correspond to the weighted average return based on membership size of each group. This would ensure that disclosures reflect the experience of savers.

82. Where mergers occur between different providers, we do not propose to apply chain-linking requirements because we do not want to discourage consolidating schemes from accepting legacy business from poorer performing providers.

83. We believe this approach would provide comparable data about investment performance and member outcomes even when schemes introduce changes. It would also discourage instances where changes to default composition or investment strategy have been relied upon to “re-set” reporting of past investment performance.

Consultation question

Q4: Do you agree with our proposals on “chain-linking” data on past historic performance where changes have been made to the portfolio composition or strategy of the default arrangement?

4.6. Returns net of investment charges only

84. We also propose an expectation that schemes disclose returns net of investment charges and transaction costs only. Since transaction costs are already in fund gross returns, we refer to this metric as ‘returns net of investment charges only’ in this consultation paper. This metric will show investment returns in a direct relationship with the charges associated with them and highlight the subsequent impact of administration charges on outcomes for pension savers.

85. For returns net of investment charges only, we propose to expect disclosure of at least the return over one year. This will show the difference with the return net of all charges over one year.

86. We are also considering disclosure of returns over 3, 5, 10 and 15 years, if available. This is because it may be difficult for some providers with vertically integrated business models or with single or combination charging structures to retrospectively determine the split between investment charges and administration charges for longer periods going back.

87. We intend to provide additional guidance to clarify how we define investment charges and transaction costs, based on a non-exhaustive list of costs and charges previously published by DWP[footnote 20].

Consultation question

Q5: Do you agree with proposals for the additional disclosure of returns net of investment charges only?

4.7. Asset allocations

88. DWP’s October 2022 consultation “Broadening the investment opportunities of defined contribution pension schemes” proposed draft regulations and statutory guidance that would require qualifying DC and CDC schemes to disclose in their annual Chair’s Statement the percentage of assets allocated to eight main asset classes (cash, bonds, listed equities, private equity, property, infrastructure, private debt and “other”) in their default arrangements (main arrangements for CDC).

89. We intend to propose similar disclosures under this VFM framework to help decision-makers interpret data on investment performance. We are considering requiring asset allocation disclosure for each of the different age points, but only covering the portfolio mix from the previous reporting year.

Consultation question

Q6: Do you agree with requiring disclosure of asset allocation under the eight existing categories for all in-scope default arrangements?

4.8. Forward-looking metrics

90. While the majority of the investment performance data under the VFM framework would be backwards-looking, factual data, we recognise that future investment performance is what ultimately matters to savers.

91. Calculating reliable, useful, and comparable forward-looking projections of investment returns can be challenging. However, we think a simple forward-looking metric could supplement backward looking information. This would be helpful to employers and others in selecting and monitoring schemes, as well as to trustees and IGCs when comparing the expected performance and inherent risk of their current default design to that of other schemes.

92. A forward-looking perspective would also be useful where schemes have made changes to their investment strategies or cost structures.

93. We recognise that schemes and providers may have an incentive to inflate expected returns to attract business, but over-promising is likely to be called out publicly over time.

Approaches for calculating forward-looking metrics

94. We have been working closely with the Government Actuary’s Department (GAD) to consider the options for a forward-looking investment performance metric which balances robustness, ease of understanding, and consistency. This has focused on:

- Stochastic modelling – Methods which involve multiple simulations to project investment performance. This would show an expected distribution of future investment performance that would illustrate a central estimate and upside and downside outcomes.

- Deterministic modelling – Methods which involve calculating the investment returns with fixed input assumptions. Scenarios could be modelled to illustrate a range of possible outcomes.

95. The early scoping work has identified a number of challenges, including the availability and capability of schemes to model outcomes, the ability to understand what judgement has been applied in those outcomes, and how this may influence the use of these forward-looking metrics.

96. Three broad approaches were identified on which we welcome views, along with further suggestions:

- Stochastic modelling with a range of outputs – Model runs with randomly varying assumptions to obtain a distribution of investment returns.

- Stochastic modelling with “Risk at Retirement” output – Relate the change in asset value to what it means for a DC member. For example, given an investment shock, how many extra years would a member have to save to make up investment returns.

- Deterministic modelling – Using prescribed returns assumptions applied to the scheme’s investment strategy. An extension of this could include further prescribed return assumptions to simulate a range of scenarios as an alternative way of considering risk.

97. We are considering an approach to require the disclosure of a single metric for expected return and a single metric for risk. With both metrics estimated for a pension saver in the default arrangement from age 25 to state pension age. For comparability, the expected return metric would be reported on a cash/CPI+X% basis.

98. Schemes will have internal objectives for their investment portfolios so we think this information should be readily calculable and we would provide guidance to support his calculation.

Consultation question

Q7: Do you think we should require forward-looking performance and risk metrics, and if so, which model would you propose and why?

Chapter 5: Costs and charges

5.1. Objectives of our proposals

99. Our overarching aim for requiring publication of costs and charges data is for trustees and IGCs to see how their overall costs and charges impact on the overall value they provide to their members and how this compares to other schemes. We want them to be able to use this data alongside services data to compare the quality of services with the costs charged for those services.

100. Having taken respondents’ comments from the previous discussion paper on board, we propose building on the definitions that underpin existing disclosures – primarily ‘administration charges’ and ‘transaction costs’ - and to limit the production of further data to that necessary to enable comparisons to be made.

101. We want trustees and IGCs to take account of costs and charges throughout the assessment process, starting with net returns. However, we think that separate disclosure of costs and charges is also needed for clear comparison between schemes. The disclosure of investment charges only will complement the corresponding net returns metric, by showing how much a scheme is paying for asset management, including any performance-based fees. Additionally, the disclosure of all “service” costs (all costs aside from investment charges and transaction costs), as a percentage of assets under management, will highlight differences between schemes and assessment of whether the services delivered are worth the cost.

102. For schemes with multiple employers, we think that the format of cost and charges disclosures should mirror the cohort approach proposed for net investment returns.

Our proposals

103. Our proposal differs from the existing requirements in two respects. Firstly, we propose that schemes disclose total charges rather than ‘member borne’ charges. Our rationale for this is that the inclusion of employer subsidies provides a more comparable metric and avoids schemes with subsidies appearing better value.

104. Secondly, we propose that schemes also disclose the total amount of administration costs. By this we mean the amount spent on anything other than investment. Our rationale here is that IGCs and trustees will need this figure in order to compare the quality of their services (as disclosed under the services metric) against the cost of those services.

5.2. Disclosure of charges

Bundled schemes

105. Schemes using a vertically integrated provider for both investment and administration will need to unbundle these costs in order to disclose the amount they are paying specifically for services. We appreciate that this may not be straightforward but should be achievable.

106. We propose service costs and charges to be understood as all costs and charges that aren’t directly investment costs and charges. We intend to provide additional guidance to clarify how we define service charges, based on a non-exhaustive list of costs and charges previously published by DWP[footnote 21].

Consultation question

Q8: Are there any barriers to separating out charges in order to disclose the amount paid for services?

Combination charging structures

107. Most schemes apply an annual percentage charge on funds under management. However, we are aware that there are schemes which apply a combination charging structure. For default arrangements of DC schemes used for automatic enrolment, there are only two permissible combination charging structures:

- a percentage of funds under management combined with a contribution charge

- a percentage of funds under management charge combined with a flat annual fee

108. In order for schemes to be able to compare their charges, disclosure for the purposes of the framework must be on a like for like basis. We are therefore considering requiring schemes with a combination charging structure and legacy schemes with more complex charging structures to express those charges as a single annual percentage. We intend to provide additional guidance to clarify how schemes should do this.

Consultation question

Q9: Do you have any suggestions for converting combination charges into an annual percentage? How would you address charging structures for legacy schemes?

Schemes with multiple employers

109. We recognise that for master trusts and overarching HMRC-registered schemes, charges vary by employer, and we feel it is important to provide greater transparency in this area. It is important for trustees and IGCs to be able to assess whether the charges for their scheme are reasonable compared to others in the market. We therefore propose that multiple charges be broken down according to cohorts of employers based on assets under management. This would be consistent with the approach we have outlined in chapter four regarding the provision of net performance data.

Consultation question

Q10: Do you agree with our proposal to provide greater transparency where charging levels vary by employer? Do you agree that this is best achieved by breaking down into cohorts of employers or would it be sufficient to simply state the range of charges?

Chapter 6: Quality of services

110. In response to the FCA and TPR’s discussion paper, there was consensus that outcomes for savers should be central in assessing the value of services provided and that this should be based on measurable metrics.

6.1. Objectives of our proposals

111. Our aim is to provide a holistic view of VFM. This means having to take account of other factors (over and above investment performance and costs) which make a meaningful contribution to long-term outcomes that savers value. We use the term ‘service’ to describe these factors, covering aspects such as scheme administration, governance and effective member communication to support saver understanding and decision-making. There are other aspects of service that, while potentially attractive to savers and their employers, may not drive long-term value and so should not be of primary concern when assessing a scheme.

112. We are therefore proposing key performance metrics as options that could be used to directly assess the impact service measures have on saver outcomes. The metrics proposed in this chapter are a starting point and are not intended to be comprehensive. Instead, they will enable comparisons between schemes on a small number of key indicators for the quality of services. We expect these comparisons to be used in the assessment of the value of the services offered by the scheme.

Defining clear minimum service standards for schemes

113. We believe that all schemes should be expected to meet a minimum standard of service, but we also want to avoid schemes gold plating services where costs outweigh the benefits to savers. However, we neither want the framework to be a box ticking exercise nor hinder innovation or competition amongst stakeholders. Schemes may go beyond minimum standards to deliver value by supporting and giving confidence to savers throughout their pension saving journey.

114. We propose to require assessments on features for which all savers pay, rather than additional features paid for separately by certain individuals but which are not captured by the assessment of costs and charges. We therefore propose to relate the quality of services and oversight to the disclosures of non-investment costs and charges.

A focus on assessment of outputs

115. We accept there are challenges with a consistent measurement and quantification of a subjective and qualitative concept such as ‘quality’. Measuring ‘quality’ is difficult not only because of the differences in rules between scheme types, but also because different schemes have different membership profiles, and the expectations of savers vary between memberships and the different stages of the retirement journey. Therefore, the metrics must reflect saver experience and demonstrate how they have helped savers at critical junctions in their pension journey where they need support to make good decisions.

116. We are proposing an approach where the quality of service is measured against the member outcomes (outputs) it delivers. Instead of requiring schemes and providers to report on a large number of service metrics, some of which are qualitative, we propose that schemes and providers report on selected elements of service that are quantifiable.

117. We do not intend that schemes stop providing value to savers through other elements of service, which are not covered by our proposed metrics. Trustees and IGCs will be able to provide more detail about the other service offerings that they consider contribute and add value, when completing their VFM assessments. We expect this approach to improve transparency and encourage stakeholders to engage in meaningful conversations on their approach to services and share their metrics accordingly. Commercial schemes must not collude on their approach with competing schemes.

118. Over time, we expect more consistency in how the industry measures other aspects of service quality, such as pension saver engagement. We may in the future propose adding to the service metrics in the framework.

6.2. Member communications

119. Effective communications can influence member behaviour and decisions at every stage of the retirement journey, including investment choices, contributions, retirement age and drawdown decisions. Good quality communication can support members in making informed and timely decisions about their savings and thereby ultimately drive improved member outcomes. We want to allow schemes to develop and assess their communication strategies against those of other schemes, which we expect to result in improvements across the industry.

120. The key point to measure and assess is not the communications in themselves but whether or not they drive improved member outcomes. The quality of communication should be measured based on its effectiveness and against the member outcomes it leads to. The following metrics seek to capture this.

Proposed options

121. In line with suggestions made by respondents we propose the following two metrics as options that trustees and providers of contract-based schemes could use to assess and disclose the:

- Percentage of members who update/confirm their selected retirement date, and how they wish to take benefits, and/or update their expression of wishes; and

- The outcomes of member satisfaction surveys, including the percentage of members who have completed the survey, the Net Promoter Score, and/or member feedback against a small number of standard focus questions.

Consultation questions

Q11: Are these the right metrics to include as options for assessing effective communications? Are there any other communication metrics that are readily quantifiable and comparable that would capture service to vulnerable or different kinds of savers?

6.3. Scheme administration

122. Efficient administration is critical to ensuring a positive experience for employers, trustees and savers. All schemes are expected to meet certain basic administrative requirements, with most trustees and many contract-based providers outsourcing administrative services. However, trustees and providers cannot outsource responsibility for the quality of administration. High-quality administration results in added value through good record keeping, accurate and timely core financial transactions and the availability of informative and engaging servicing tools. Poorly administered schemes and delays to core transactions have consequences, such as value detraction and a loss of confidence from savers. Even if interactions between a scheme and its savers are infrequent, better administrative quality provides crucial value for savers at key moments, such as when accessing funds at retirement.

Proposed options

123. In line with our aim of building on existing requirements, we have considered the value for members assessment requirements for trust-based schemes under £100m assets under management. For these schemes, the Occupational Pension (Scheme Administration Regulations[footnote 22] (‘the Administration Regulation’) set out 7 key metrics of administration and governance that must be considered and assessed. Of the seven metrics, two of these are readily quantifiable, and we welcome your views on extending these to all schemes, including schemes offered by FCA regulated providers, to report on:

Promptness and accuracy of core financial transactions

According to the Administration Regulations and existing DWP guidance[footnote 23], the promptness and accuracy of core financial transactions should be considered by trustees of specified schemes as part of their value for members assessment. Core financial transactions include, but are not limited to:

- Payment in and investment of member and employer contributions

- Transfers between schemes

- Transfers and switches between investments within a scheme

- Payments out of the scheme to beneficiaries

Similarly, IGCs must assess whether core financial transactions are processed promptly and accurately.

124. We propose that trustees and providers disclose the proportion of the above member transactions that have been completed accurately and within required timeframes set in legislation and according to any service level agreements (SLA) set within the scheme. This should help to determine whether they are achieving good value for members under this measure.

Quality of record keeping

According to existing DWP guidance[footnote 24], trustees should collectively consider the security, accuracy, scope and quality of their data to determine whether they are providing value for members in the area of record keeping. Currently, TPR requires trustees to report their data scores for common and scheme specific data in their annual scheme return. We could consider whether to require disclosure of these scores as framework metrics, which would mean contract-based providers needing to assess the quality of their common and scheme specific data in the same way.

Consultation question

Q12: Are these the right metrics to include as options for assessing the effectiveness of administration and/or are there any other areas of administration that are readily quantifiable and comparable?

6.4. Governance

125. We propose that there is no standalone ‘governance’ metric. Some respondents to the FCA / TPR discussion paper felt that the quality of governance is already reflected in other aspects of the VFM framework and therefore should not be included as a separate component. We also believe that it will be challenging to reduce the ‘governance’ dynamic to a purely quantitative metric or key indicators.

Chapter 7: Disclosure templates and publication timings

7.1. Reporting Templates

126. To enable meaningful VFM assessment and accurate comparisons, framework data will need to be collected and published in a consistent and accessible format where data can be easily extracted and processed.

127. We are considering requiring schemes to report data against the value metrics of the three VFM components (investment performance, costs and charges and quality of services) using a prescribed reporting template. We intend to consult on template design proposals at a later stage.

7.2. Publishing Options

128. We are considering two options for the publication of the framework data:

- A decentralised approach, such as providers websites.

- Via an official centralised portal.

129. Both options have different costs and benefits and we would welcome stakeholder views on the likely impacts as we consider which option to take forward. We intend to publish an Impact Assessment alongside formal proposals.

Decentralised approach

130. Under this approach, those responsible for schemes would be required to disclose their framework data on a publicly accessible website using a prescribed template. This could be a provider’s own website or another publicly available site. Collectively, all the published data would then constitute an ‘open source’ of schemes’ framework data. All stakeholders should have free access to this information.

131. To ensure compliance with the publication timeline, we are considering a parallel obligation for trustees and providers to notify the relevant regulator that publication has taken place and to provide them with the relevant URL. For trust-based schemes this could be via the Scheme Return and the FCA could introduce a notification requirement for workplace personal pension schemes.

132. Potential advantages with this solution include getting framework data into the public domain quickly and relatively cheaply – without the potential delays and additional expense that would come from introducing a dedicated platform. We expect this solution to deliver a high degree of accessibility and transparency with complete scheme data available to our target audience and regulators.

133. This approach could also give rise to the development of industry and/or private sector initiatives to make the data more user-friendly. This could be through services that collate the scheme return data and make this commercially available alongside search and comparison tools to our target audience.

134. However, we also recognise that there are data accessibility, quality and validity issues with this approach that could compromise the comparison of scheme performances that VFM assessments are designed to deliver. For example, stakeholders may need to go to the websites of different providers to obtain the data and it might be challenging to verify the quality of data. One way of mitigating this risk could be to ensure that data is used appropriately by commercial comparison sites through a formal accreditation process.

Centralised approach

135. An alternative option would be to develop a ‘central repository’ for the data being collected, to which schemes would be required to submit their data directly via a web portal using a prescribed template. The repository would validate and process the data which would then be published for a professional audience to use. The central repository could be hosted by regulators, or with delivery outsourced to an accredited and independent third-party industry provider.

136. The advantages of this approach are that it simplifies the handling and analysis of the data itself, with data processes required to be carried out only once at source and not on multiple occasions by multiple providers. Avoiding successive manipulation of the data helps eliminate the possibility of it being subject to errors.

137. A centralised solution could also give regulators – directly or through data access arrangements with any third-party provider – greater control and visibility of the collected data for compliance purposes. This may give stakeholders more confidence about the quality and reliability of the data against which individual comparisons are being made.

138. In the long-term, regulators might use the data to support their own assessment and comparisons. This could mean designing comparator tools that would show schemes where their performance ranks in terms of the aggregated results of all assessments, both overall and against each of the individual VFM criteria.

139. A centralised approach would entail work to design, build and launch the necessary information architecture as well as new powers in legislation to enable funding and operation. It is therefore likely that this option will be slower in implementing than the decentralised approach. It will also impose ongoing costs on the regulated sectors associated with the development and maintenance of the data repository and comparator tools.

Consultation question

Q13: Do you agree with a decentralised or a centralised approach for the publication of the framework data? Do you have any other suggestions for the publication of the framework data?

7.3. Reporting Periods and Deadlines

Publication of Framework data

140. Without clear deadlines for the publication of VFM data, stakeholders will not have consistent access to the information required for their analysis and comparisons, potentially creating misleading assessments. To address this, we propose setting deadlines for publication of data VFM assessment reports.

141. We propose to require all framework data to be published by the end of the first quarter of the calendar year. Trustees and IGCs will then be able to use the published framework data from other schemes for their VFM assessments.

142. The framework data will need to be recorded to the same end point in time. This is important for investment performance data, where the end point can make a substantial difference to reported returns. Since returns would be reported net of costs, both net of all costs and net of investment charges only, the cost data may not be immediately available for some schemes. Therefore, we propose an end point for net returns data of 30 June of the previous year. The same costs would be reported in the costs and charges data, disclosed separately so that the amount of costs and charges and net returns can be considered.

Publication of VFM assessments reports

143. A consistent publication timing of VFM assessment results is essential so schemes have enough time to analyse the framework data published by other schemes in comparison with their own, and for the purpose of standardised, accurate monitoring and compliance.

Qualifying trust-based schemes

144. We propose to require occupational trust-based pension schemes to publish their VFM assessment results by the end of October and separately from the Chair’s Statement. Publication in the Chair’s Statement would not allow consistent reporting of VFM assessment results as occupational schemes have different scheme year ends and are required to publish their Chair’s Statement within seven months of their scheme year end. The ongoing review into the Chair’s Statement means that we cannot propose to commit to requiring VFM assessment results to be published in the Chair’s Statement. The means of publication will therefore be determined at a later stage.

145. We considered aligning scheme year ends to ensure that all schemes publish their VFM assessments at the same time. However, engagement with the industry suggested this would be a costly and burdensome policy to implement due to schemes needing to reorganise their governance structures. There are also existing statutory reporting requirements based around scheme year end dates that could be impacted if a single scheme year end was required for all schemes.

146. Industry feedback suggested that schemes may need 6-7 months to publish their VFM assessment results. A publication date of October would mean that occupational pension schemes with an April scheme year end would have 6 months to publish their results. Pension schemes with a December scheme year end would have 9 months to publish their results. However, schemes with a scheme year end between May and October may need to consider changing their scheme year end so they can conduct their assessments and meet the publication deadline.

Contract-based schemes

147. We propose to require contract-based schemes to publish their VFM assessment results in their IGC Chair’s Report by the end of October. Under FCA rules IGCs must publish their IGC Chair’s Report by the end of September. This proposal would give IGCs one more month to publish their VFM assessment results.

Consultation question

Q14: Do you agree with the proposed deadlines for both the publication of the framework data and VFM assessment reports?

Chapter 8: Assessing Value for Money

148. This chapter covers our proposals for potential approaches to VFM comparisons and a step-wise approach to assessing VFM. It also proposes three possible outcomes to a VFM assessment, the next steps a scheme should take following assessment outcomes and potential compliance and enforcement mechanisms.

149. In terms of potential enforcement mechanisms that we are considering, they include giving TPR the powers it needs to enforce wind up and consolidation where a scheme is consistently not providing value for its members.

8.1. Regulator-defined benchmarks

150. The FCA and TPR received mixed views on comparisons against market wide benchmarks of industry performance. Many industry respondents felt this might cause investment strategies to ‘cluster towards the middle’ or drive schemes to focus on short-term performance to exceed the benchmark.

151. However, benchmarks would allow us to define VFM in an objective way. Some respondents noted that performance evaluation cannot occur in a vacuum and were supportive of regulators prescribing a reasonable benchmark.