Completing the annual Value for Members assessment and Reporting of Net Investment Returns

Published 21 June 2021

Guidance for trustees of relevant occupational defined contribution pension schemes.

This guidance is effective from 1 October 2021.

Background

About this Guidance

1. The Occupational Pension Schemes (Administration, Investment, Charges and Governance) (Amendment) Regulations 2021 (‘the 2021 Regulations’) introduce new requirements for trustees and managers (referred to in the remainder of this document as trustees) of ‘relevant’[footnote 1] occupational pension schemes.

2. From 1 October 2021[footnote 2] trustees of all relevant pension schemes, regardless of asset size, are required to calculate and state the return on investments from their default and self-select funds, net of transaction costs and charges. This information must be recorded in the annual chair’s statement and published on a publicly accessible website.

3. For the first scheme year that ends after 31 December 2021,[footnote 3] and at intervals of no more than one year thereafter, trustees of relevant schemes with under £100 million of total assets, which have been operating for 3 or more years (‘specified schemes’) must carry out a more detailed assessment of how their scheme delivers value for members. The assessment must include a comparison of reported costs and charges and fund investment (performance) net returns against 3 other schemes, and a self-assessment of scheme governance and administration criteria, which are prescribed in the 2021 Regulations.

4. The outcome of the value for member assessment must be reported in the annual chair’s statement and published on a publicly accessible website. The outcome must also be reported to the Pension Regulator (TPR) via the annual scheme return.

5. The 2021 Regulations reflect the government’s expectation that if a specified scheme does not demonstrate good value for members when assessed against the comparator schemes then trustees of the specified scheme should consider winding up the scheme and transferring their members rights to another scheme that does offer good value.

6. The more detailed value for member assessment enhances the existing requirement for relevant schemes to assess the extent to which costs and charges represent good value for pension scheme members.

7. This guidance, issued by the Secretary of State for the Department for Work and Pensions, should be read in tandem with the 2021 Regulations. It is intended to assist trustees of all relevant schemes in the reporting of net investment returns. For trustees of ‘specified schemes’ it is intended to assist them in understanding the factors to be considered as part of the detailed value for members assessment, including how they might carry out a relative assessment against 3 comparison schemes.

8. This guidance also supports trustees after undertaking the value for members assessment with some factors which they may wish to take into account when determining whether it is in scheme members’ interests to wind up the scheme and transfer the rights of members into a larger pension scheme or personal pension scheme that offers better value.

9. This guidance does not provide an exhaustive definition of value for members. It sets out what trustees must have regard to, when carrying out the value for members assessment. Existing legislation places duties on trustees in relation to scheme administration and governance and trustees must ensure they are familiar with these duties. Trustees should also refer to TPR’s codes of practice and guidance on the standards expected when complying with their legal duties and seek their own legal advice.

Expiry or review date

10. This guidance will be reviewed within 18 months, from the date of first publication, and updated when necessary. When the guidance is reviewed, established and emerging good practice and user testing may be included.

Who is this guidance for?

11. This guidance is for trustees of ‘relevant’ occupational pension schemes regardless of size, who must comply with the requirements to report past investment performance (net returns) in regulation 23(1)(aa) of the Occupational Pension Schemes (Scheme Administration) Regulations 1996 (‘the Administration Regulations’).

12. This guidance is also for trustees of ‘specified schemes’ who are required to carry out the more detailed value for members assessment set out in regulation 25(1A) of the Administration Regulations. A ‘specified scheme’ is defined by regulation 25(5) of the Administration Regulations, inserted by regulation 2(3)(c) of the 2021 Regulations.[footnote 4]

13. Trustees of relevant schemes with total assets of £100 million or greater must continue to assess and explain how the costs and charges of their scheme generally represent value for members in their chair’s statement, in accordance with regulations 25(1)(b) and 23(1)(c)(iv) of the Administration Regulations.

14. This guidance is not relevant to:

- pension schemes where the only money purchase benefits offered arise from Additional Voluntary Contributions (AVCs)

- ‘relevant small’ pension schemes[footnote 5]

- executive pension schemes

- public service pension schemes, as defined by section 318 of the Pensions Act 2004

Legal status of this guidance

15. This statutory guidance is produced under the powers in:

- Paragraph 2 of Schedule 18 to the Pensions Act 2014

- Section 113 (2A) of the Pension Schemes Act 1993

16. Trustees must have regard to this guidance when complying with their obligations to: (i) disclose net investment returns under regulation 23(1)(aa) of the Administration Regulations; (ii) carry out the value for members assessment for a specified scheme required by virtue of regulation 25(1A) of the Administration Regulations; and (iii) publish information about net investment returns and the results of the value for members assessment, required by regulation 29A of the Disclosure Regulations.

Compliance with this guidance

17. TPR regulates legislative compliance for all occupational pension schemes and publishes guidance on the roles of employers and trustees. Neither the government nor TPR can provide a definitive interpretation of legislation, which is a matter for the courts.

18. Where trustees do not comply with a relevant legislative requirement TPR can take enforcement action depending on the nature of the breach. This could include a financial penalty.

19. Enforcement of Part V of the Administration Regulations, including the production and content of the chair’s statement, is provided for in Part 4 of the Occupational Pension Schemes (Charges and Governance) Regulations 2015.[footnote 6]

Reporting net investment returns

For all relevant Defined Contribution (DC) schemes

20. The 2021 Regulations require trustees of relevant occupational pension schemes to report on the net investment returns for their default arrangement(s) and for each fund which scheme members are, or have been able to, select, and in which scheme members are invested during the scheme year. Net investment returns refers to the returns on funds minus all transaction costs and charges.

21. Trustees should report on net investment returns for their default arrangement(s) (regardless of how or when they became default arrangements) where members are still invested in the fund.

22. The information on net investment returns must be stated in the annual chair’s statement for the first scheme year ending after 1 October 2021, and published on a publicly available website.

23. Net return disclosure is intended to help members understand how their investments are performing. Disclosure is also necessary for trustees of specified schemes to enable them to carry out the new detailed value for members assessment; as net returns for their schemes will need to be compared with the returns of 3 other schemes.

24. This section of the guidance is designed to assist trustees in the reporting of net investment returns for past years. For illustration only, we suggest how information could be displayed for different member age cohorts and different charging structures.

Reporting period

25. The first chair’s statement to include this information should be for the first scheme year that ends after 1 October 2021.

26. Trustees should include as a minimum the net return for the scheme year. We believe up-to-date information ensures employers and members can spot immediate trends. We recommend figures for net investment returns should also be shown dating back at least 5 years, where possible, or the start date of the pension scheme, if that is later. Where these figures are not provided for example, because data is not available or is incomplete for past years, trustees are advised to make members aware of this by reporting the reasons for this in the chair’s statement.

27. Where data for longer periods is available, i.e, 10, 15 or even 20 years, trustees should look to report this, as returns over longer periods do often reflect an investment strategy’s performance through different market conditions.

28. Please refer to the tables below which illustrate how returns could be reported.

Composition of returns

29. We advise that returns should be shown as an annual geometric average- the annual net return which, when compounded over time, delivered the return shown. The geometric mean rather than the arithmetic mean return is more accurate when measuring portfolio returns. It takes into account the compounding interaction between individual returns in addition to the returns themselves.

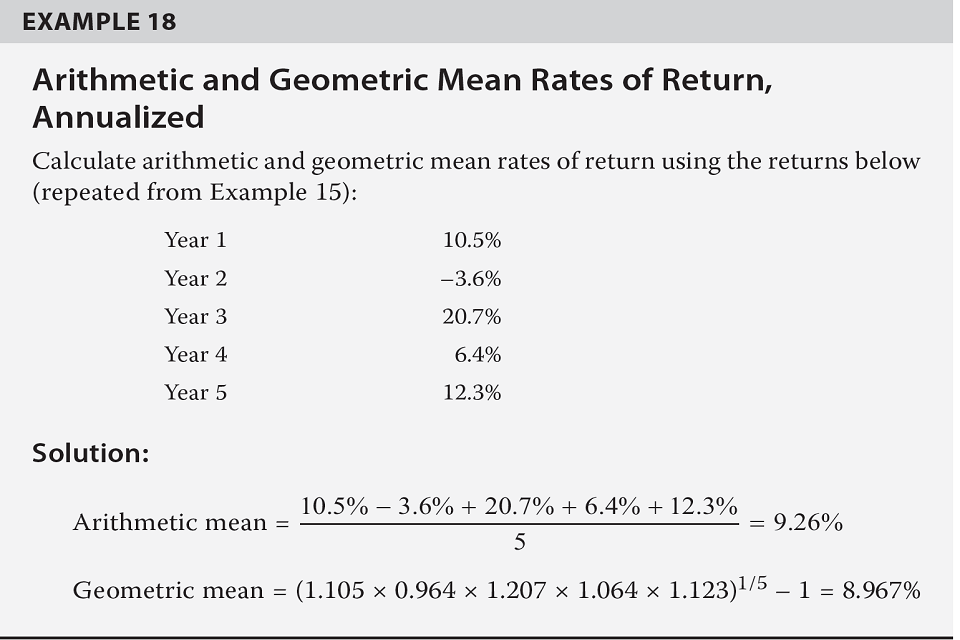

30. Whilst we believe that this concept is commonplace in financial terminology, an example of the use of a geometric average is shown below:[footnote 7]

Alternative measures of net investment return reporting

31. Trustees, if they choose, may use measures such as the individual Internal Rate of Return (IRR) or risk adjusted returns if they believe this information on investment performance is informative to their members. However, we would advise that this should be in addition to the recommendation that we have set out for net investment returns above. The reason for this is so there is a consistency in approach when it comes to schemes needing to compare net returns with 3 other schemes, as part of the detailed value for member assessment requirements.

Consideration of savings profile

32. For illustrative purposes trustees may decide to show returns on a £10,000 lump sum allocation to a fund at the start of the reporting period, with no subsequent contributions or added fees when the allocation was made.

Investments where net returns vary with scheme member age or with employer

33. For an arrangement where the net returns vary with age – for example a target date fund, lifestyle arrangement or an arrangement with some other kind of de-risking – trustees should show age specific results for savers aged 25, 45, and 55 at the start of the recommended five-year reporting period. It is not expected that trustees will show age specific results for savers aged under 25 or over 55.

34. For an arrangement where the net returns vary with employer – for example, because employees of different employers are charged different amounts for the same funds – pension schemes should present net returns in such a way that a scheme member would be able to identify the returns they have received or would have received, were they to have the savings profile and age suggested above.

Example presentations of data

Example 1: Arrangement with no age-related returns – same charge levied on all savers

Annualised Returns (%)

| (if available) 20 years (2001 to 2021) | (if available) 15 years (2006 to 2021) | (if available) 10 years (2011 to 2021) | (expected) 5 years (2016 to 2021) | (expected) 1 year (2021) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| x.y% | x.y% | x.y% | x.y% | x.y% |

Example 2: Arrangement with age-related returns – same charge levied on all savers

Annualised Returns (%)

| Age of member in 2021 (years) | (if available) 20 years (2001 to 2021) | (if available) 15 years (2006 to 2021) | (if available) 10 years (2011 to 2021) | (expected) 5 years (2016 to 2021) | (expected) 1 year (2021) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | x.y% | x.y% | x.y% | x.y% | x.y% |

| 45 | x.y% | x.y% | x.y% | x.y% | x.y% |

| 55 | x.y% | x.y% | x.y% | x.y% | x.y% |

Example 3: Arrangement with age related returns and returns which vary by employer

35. In this example, the scheme applies different charges to different employers, meaning that returns may vary between employees. Trustees do not need to produce multiple tables of returns but can instead provide additional information for each group of employers. The example below shows a scheme with 4 groups of employers (labelled simply as Employer A, B, C or D) who pay differing charges:

Annualised Returns (%)

| Age of member in 2021 (years) | Employer A, B, C or D | (if available) 20 years (2001 to 2021) | (if available) 15 years (2006 to 2021) | (if available) 10 years (2011 to 2021) | (expected) 5 years (2016 to 2021) | (expected) 1 year (2021) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | Employer A | x.y% | x.y% | x.y% | x.y% | x.y% |

| Employer B | ||||||

| Employer C | ||||||

| Employer D | ||||||

| 45 | Employer A | x.y% | x.y% | x.y% | x.y% | x.y% |

| Employer B | ||||||

| Employer C | ||||||

| Employer D | ||||||

| 55 | Employer A | x.y% | x.y% | x.y% | x.y% | x.y% |

| Employer B | ||||||

| Employer C | ||||||

| Employer D |

Subsequent updating of returns data

36. Subsequent years’ data should be added and the average return recalculated. There is no need to remove data from earlier years, as longer time series allow for more reliable comparison. The example given below is for reporting in 2022.

Example 4

Annualised Returns (%)

| Age of member in 2022 (years) | (if available) 20 years (2002 to 2022) | (if available) 15 years (2007 to 2022) | (if available) 10 years (2012 to 2022) | (expected) 5 years (2017 to 2022) | (expected) 1 year (2022) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | x.y% | x.y% | x.y% | x.y% | x.y% |

| 45 | x.y% | x.y% | x.y% | x.y% | x.y% |

| 55 | x.y% | x.y% | x.y% | x.y% | x.y% |

New detailed annual ‘Value for Members’ assessment

For specified schemes only

37. From the first scheme year ending after 31 December 2021 trustees of ‘specified schemes’[footnote 8] are required to carry out a more detailed value for members assessment. The assessment must involve a comparison of reported costs and charges and fund performance (net investment returns) with 3 other schemes, and a consideration of key governance and administration criteria.

38. The outcome of this assessment must be explained in the annual chair’s statement and published on a publicly accessible website. The outcomes must also be reported to TPR via the annual scheme return.

39. The government is clear in its expectation that members should be in well run schemes that deliver optimal value for members over the long term, and that this can be achieved by consolidation. The basis of the new more detailed value for members assessment is therefore to determine whether members will receive this value in their existing scheme over the long term, or whether they would achieve better value in a different scheme.

Calculation of total assets and hybrid schemes

40. One of key factors in determining if you are a ‘specified scheme’ is by the total assets held. The ‘total assets’ of a scheme are defined by regulation 25(6) of the Administration Regulations, inserted by regulation 2(3)(c) of the 2021 Regulations. The calculation should (except in the case of an ear-marked scheme) use the total of the amount of the net assets of the scheme recorded in the audited accounts for the scheme year.

41. Hybrid schemes where the total assets (Defined Contribution (DC) and Defined Benefits (DB) elements of the scheme added together) are below £100 million, are within the definition of specified schemes set out in regulation 25(5) of the Administration Regulations. However, regulation 25(1E), as inserted by regulation 2(3)(b) of the 2021 Regulations makes clear that the trustees should only assess the costs and charges and investment returns relating to the DC element of their scheme when conducting the detailed value for members assessment. Where a comparison is made with a hybrid scheme, that comparison should only be with costs and charges and investment returns relating to the DC element of the comparison scheme.

Schemes in the process of wind-up to be exempt from the detailed value for member assessment

42. Trustees of specified schemes will not be required to carry out the value for member assessment or report its outcome, if they have notified TPR under section 62(4) or (5) of the Pensions Act 2004 that the winding up of the scheme in question has commenced, before the date by which they are required to prepare a chair’s statement under regulation 23(1) of the Administration Regulations. Trustees must however explain in the annual chair’s statement that wind-up is the reason why they are not complying with this duty.

43. Schemes entering wind-up to which this exemption applies will continue to be relevant schemes and as such trustees will still be required to state their investment returns and costs and charges with an assessment of whether the latter offers value for members in the chair’s statement. This is important because it means trustees are still obliged to assess whether their costs and charges offer good value to members up until the point that wind up of the scheme is completed.

44. Trustees should also refer to TPR’s existing guidance[footnote 9] on wind-up to understand the steps to be taken when winding-up their scheme.

Factors to take into account when completing the value for member assessment

45. When carrying out the value for members’ assessment, trustees must consider 3 factors:

- Costs and Charges

- Net investment returns

- Administration and Governance

46. Costs and charges and net investment returns must be assessed relatively, based on comparison with other pension schemes, having due regard to this guidance.

47. Administration and Governance is assessed on an absolute basis within the pension scheme itself, having due regard to this guidance.

Against whom should trustees compare themselves for the relative assessment?

48. For the purposes of assessing costs and charges and net investment returns as part of the value for members assessment, each specified scheme must compare itself with 3 ‘comparison schemes’.[footnote 10]

49. Each scheme used as the basis for the comparison should be:

- an occupational pension scheme which on the relevant date (the date on which the trustees obtained audited accounts for the scheme year that ended most recently) held total assets equal to or greater than £100 million; or

- a personal pension scheme, which is not an investment-regulated pension scheme within the meaning of paragraph 1 of Schedule 29A to the Finance Act 2004

50. In respect of hybrid schemes which are specified schemes, we recommend that the comparison schemes they should aim to use are either a scheme which provides only DC benefits or a larger hybrid scheme where the total assets held to provide DC benefits are £100million or more.

51. We expect trustees to have a clear rationale for the schemes they have chosen as comparators. The comparators should include a scheme that is different in structure to their own, where possible. For example, bundled corporate pension schemes should look at an unbundled example, and pension schemes not used for automatic enrolment should not limit their comparison to other such schemes.

52. Trustees of pension schemes in which employers subsidise charges should take this benefit into account when comparing charges with other schemes.

53. Trustees of pension schemes with combination charge structures should use their scheme’s demographic profile to identify an approximate per member average reduction in yield, and use this for the basis of their comparison of net returns and charges with those available from other pension schemes.

54. When selecting the 3 comparator schemes the 2021 Regulations also require that trustees of specified schemes must ‘have had discussions’ with at least one of the comparator schemes about a transfer of the member’s rights if the specified scheme is wound up. This requirement is intended to ensure that schemes are selecting at least one comparator scheme that could reasonably be expected to accept a transfer of the rights of the members of the specified scheme in the event that the scheme decides following the value for members assessment that it does not provide good value. By only requiring discussions to have taken place, this means a specified scheme will always be able to carry out the value for member assessment against 3 comparators even if subsequently the terms of a transfer of members from that scheme cannot be agreed with the potential comparator scheme.

55. Trustees of specified schemes are of course at liberty to choose their own comparison schemes, each time they conduct the value for members assessment, but they may wish to note that TPR publishes an up-to-date list of authorised master trust schemes which trustees might find useful.

Factor 1: Costs and Charges

56. Relevant pension schemes are already required to state their charges and transaction costs in the annual chairs’ statement. For the purposes of the value for members assessment, there are no new requirements in relation to disclosure of charges and transaction costs, however trustees of specified schemes could build on this by recording existing disclosures alongside the anonymised costs and charges data from the 3 comparator schemes in a simple form similar to the example given below.

| Scheme | Charges | Transaction costs | Total of charges and costs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Default | |||

| Comparator A | |||

| Comparator B | |||

| Comparator C | |||

| Self-select 1 | |||

| Comparator A | |||

| Comparator B | |||

| Comparator C | |||

| Self-select 2 | |||

| Comparator A | |||

| Comparator B | |||

| Comparator C |

57. Where charges and transaction costs vary by age, we suggest that charges and costs are shown for a number of ages, for example at 10 year intervals.[footnote 11]

Sources of comparison data

58. As with investment performance, trustees should be able to compare their charges and transaction costs against other relevant pension schemes, using the disclosures which those other pension schemes are required to publish.

59. Trustees may also use data from their advisers, dedicated service providers, or other published reports such as the DWP DC Pension Charges Survey,[footnote 12] and those which are published by commercial organisations.

What should be compared

60. Trustees should compare their most recent assessment of the total charges and transaction costs for their own funds with those of their chosen comparison pension schemes.

61. Where charges and transaction costs are unusually high for a reason which is unlikely to be repeated, trustees may use an average of the last 5 years. Where data is available for fewer than 5 years, an average of total charges and transaction costs over the years for which data is available may also be used.

62. Trustees should compare charges and costs of their own default arrangement against other schemes’ default arrangements, even though the investment strategy may not be identical.

63. Trustees should compare the total most recent charges and transaction costs for their popular self-select funds with the nearest comparable funds in other pension schemes. Where the trustees provide popular non-default ‘legacy funds’ such as with-profits, and the comparison pension scheme does not offer comparable funds, these legacy funds should be compared with default arrangements.

When the charges represent good value for members

64. When assessing value for members, the total charges and transaction costs in default arrangements should be given greater weight than self-select funds in which smaller numbers of members are likely to be invested.

65. If - giving greater weight to the charges and costs relating to the default arrangement – a majority of the total of charges and transaction costs across popular funds are closely comparable with or lower than the average for comparator pension schemes, then it would be reasonable to assume that the scheme as a whole represents good value for members from the standpoint of costs and charges. However, if higher charges are justified by higher, not just broadly comparable, investment returns, then pension schemes should be reported as good value from a costs and charges perspective.

66. Where, however, again giving greater weight to defaults, a majority of the funds under consideration have higher total charges and transaction costs than the average for comparator pension schemes, and there are not mitigating circumstances, for example, higher average performance, then it would be reasonable to assume that the pension scheme as a whole represents poor value for members from a costs and charges perspective.

Factor 2. Investment Returns (Fund Performance)

67. Trustees are required as part of the value for member assessment to consider their investment returns against the investment returns of the 3 comparator schemes. Whilst the value for member assessment requires trustees to assess investment returns and costs and charges of their funds, trustees are expected to place more weight on the performance of their investment returns over costs and charges.

68. While past performance is not necessarily an indicator of future performance, sustained long-term underperformance of investment returns should signal poor value for members. When looking at investment returns, trustees should therefore compare net performance investment returns both in the short term (we recommend a one-year period) to give an immediate indication of performance trend, and over a longer more sustained period for which broadly comparable data can be found (preferably 5, 10 and 15 years).

Sources of comparison data

69. Trustees of specified schemes should be able to compare their net returns against those contained in the published disclosures of investment returns of other relevant schemes who are required to comply with the new requirements in the 2021 Regulations.

70. As schemes start to comply with these requirements i.e. for the first value for member assessment there will be some trustees of pension schemes that need to make their comparisons without access to equivalent disclosures from other pension schemes. In this instance trustees may want to ask advisers or dedicated service providers for anonymised data, where it is available, from other pension schemes they advise, subject to client consent. Alternatively, they can use commercially published sources of data.

71. Trustees may wish to continue to supplement published statutory disclosures as a data source with other sources of intelligence on net returns.

What should be compared

72. Trustees should compare returns of their default arrangements with other pension schemes’ default arrangements – it is not necessary for the default arrangements to have a similar asset allocation.

73. Trustees should compare returns for their most popular self-select funds with the nearest comparable funds in other pension schemes. Where the trustees provide ‘legacy funds’ such as with profits, and the compared pension scheme does not offer comparable funds, these should be compared with default arrangements (see ‘How to value legacy funds’ in paragraph 117).

When the performance is good value for members

74. The investment returns in default arrangements should be given more weight than self-select funds. Trustees should not give weight to funds in which only a small proportion of members are invested.

75. If a majority of net return figures for a pension fund in which the scheme members are frequently invested are closely comparable with or better than the average for comparator funds, then it would be reasonable to deduce that the fund represents good value for members from the standpoint of investment returns for that fund.

76. If – giving greater weight to the defaults – this is repeated across a majority of other funds offered by the pension scheme in which members funds are frequently invested, then it would be reasonable to deduce that the pension scheme as a whole represents good value for members from an investment returns perspective.

77. Where a clear majority of net performance figures for a particular fund are worse than the average for comparator funds, this is an indicator that the fund represents poor value for members. If this is repeated across a majority of funds in which members are frequently invested, again giving greater weight to the defaults – and there is not a clear strategic choice that explains this outcome for example, members in this default are closer to retirement than comparators and therefore less likely to be invested for growth – then it would be reasonable to deduce that the scheme as a whole represents poor value for members from an investment performance perspective.

Factor 3. Governance and Administration

78. Trustees must assess the value delivered by their governance and administration offering as part of their assessment of value for members, together with costs and net returns. Effective scheme governance is essential for the operational and financial sustainability of pension schemes, for good outcomes from investment, and for the trust and confidence of scheme members.

79. Where functions or tasks have been delegated to third party administrators or other suppliers, trustees should remember that the responsibility for those functions remains with the trustees. Trustees should ensure that the performance of their scheme administrator and all other providers of key functions to the scheme are closely and regularly monitored.

80. For the value for members assessment, the Administration Regulations (as amended by the 2021 Regulations) set out the 7 key metrics of Administration and Governance that must be considered and assessed, these are listed below:

I) Promptness and accuracy of core financial transactions

81. Delays or inaccuracies in processing financial transactions and the work to reconcile and rectify errors significantly impact on the value members receive. Trustees should have effective processes in place to control such risks and these should be reviewed regularly.

82. Core financial transactions must be processed promptly and accurately.[footnote 13] Transactions that are not processed promptly not only affect scheme member satisfaction, but can also affect scheme members’ net returns due to out-of-market risks. Trustees should also remember that there are legal requirements to complete certain tasks and transactions within maximum timescales.

83. Identifying, reconciling and rectifying errors is a cost and resource intensive exercise. The quality of member records and scheme data has a significant impact on accuracy.

84. The promptness and accuracy of the following 4 core financial transactions should be considered by trustees of specified schemes as part of their value for members assessment. General guidance on effective processing of core transactions may be found on TPR’s website:[footnote 14]

A. Payment in and investment of member and employer contributions

B. Transfers between schemes

C. Transfers and switches between investments within a scheme

D. Payments out of the scheme to beneficiaries

85. Trustees should assess the proportion of member transactions that have been completed accurately and within required timeframes set in legislation and according to any service level agreements (SLA) set within the scheme. This should help to determine whether they are achieving good value for members under this measure. Trustees could also examine the level of member/beneficiary complaints in determining whether the scheme delivers value for members in terms of promptness and accuracy.

II) Quality of Record Keeping

86. Reliable, accurate and secure data is essential to delivering value for scheme members, particularly where employment patterns are becoming increasingly disjointed and unpredictable.

Security of Data

87. Trustees should have controls in place to ensure that scheme members data is secure and is processed in accordance with the requirements of the Data Protection Act 2018.

88. Data security is a key part of trustee governance and should feature prominently in the scheme’s risk register and risk planning. This is particularly important when considering business continuity mitigations and how the scheme can continue to operate securely if, for example, key personnel are unavailable. Trustees should assess the robustness of the controls they have in place. Trustees should also consider whether they have effective controls in place to deal with data security and cyber risk.

89. Where record keeping is outsourced trustees should look at the effectiveness of data security controls put in place by their outsourced provider.

Accuracy and scope of records and data kept

90. It is essential that accurate scheme data and member records are kept. Smaller schemes with legacy records may find it particularly challenging to demonstrate value for money in terms of data accuracy.

91. Trustees should check that they are holding all the data that they are required to hold by law including, for example, books and records relating to trustee meetings and certain transactions.[footnote 15]

92. Trustees could assess the quality and accuracy of their common data (member’s personal data and membership status) and scheme specific data (financial data and options exercised). Guidance on what common and specific data should be held can be found on TPR’s website.[footnote 16]

93. Questions that trustees should ask when assessing the quality of all their data include:

- Is the data up to date?

- Is there any data missing?

- Are there systems in place to monitor and update data regularly - for example, members’ addresses and members’ fund choices?

- Is it clear who is responsible for maintaining, monitoring and updating the data?

- Are validation checks and reports being run regularly?

94. TPR requires schemes to report their data scores for common and scheme specific data in their annual scheme return. Trustees may wish to consider using the level of these scores as a guide to determining how well they are delivering value to their members in relation to accuracy and scope of their data.

Review of Data

95. A review of scheme member records should be undertaken regularly. TPR advises that this should be at least once per year. Trustees should complete such a review in advance of each annual value for members assessment. Regularly reviewing the quality of record keeping is essential for maintaining good standards, and is a key component of delivering value for members in this area.

96. Trustees should collectively consider the security, accuracy, scope and quality of their data review to determine whether they are providing value for members in the area of record keeping

III) Appropriateness of the default investment strategy

97. The quality of decision-making and governance in relation to the scheme’s investment strategy is a crucial part of the value delivered by the scheme.

98. Legislation requires the chair of trustees to include a copy of the most recent statement of investment principles for the default arrangement in the annual chair’s statement, and to give details of any review of the default strategy and the performance of the default arrangement that took place during the year.[footnote 17]

99. In order to assess the value for members delivered by the default strategy, trustees should assess the extent to which the following apply to their default arrangement(s), and explain how these positions have been achieved:

a) The investment strategy is clear, is appropriate for each stage of the member journey, and is consistently followed in accordance with strategy objectives;

b) The value added from portfolio construction, asset allocation and manager selection is assessed when the investment strategy is reviewed;

c) The risk and return in the investment strategy is properly considered and is suitable for the objectives of the scheme and the demographic profile of the members;

d) The policies on ESG and climate change risks and opportunities in the statement of investment principles are not generic, but are tailored to the investment strategy of the scheme or fund.

IV) Quality of Investment Governance

100. Trustees retain responsibility for securing the proper management of the scheme’s assets, and good scheme investment governance is crucial. Expert and robust investment governance comes to the forefront particularly during economic shocks that affect the value of pension assets.

When assessing value for members in this area, trustees should consider the following measures of good investment governance:

a) Documented and robust investment governance procedures are in place and adhered to. In schemes where there is more than one trustee, there is a clear investment governance structure in place and each member within that structure is clear about their role and level of authority in decision making;

b) Where tasks and decisions in relation to investment are delegated, those individuals have the required knowledge and expertise to perform their role competently in accordance with sections 34 and 36 of the Pensions Act 1995[footnote 18] and are being held to account;

c) Trustees can demonstrate that where fiduciary managers and investment managers are used, trustees remain actively engaged with such managers when investment decisions are made;

d) The trustee board as a whole has the knowledge and competence to oversee investment effectively, they ensure investment objectives and strategies are understood and followed, and are able to challenge investment advice where necessary;

e) Reviews of how funds are performing against those objectives and reviews of portfolios are being carried out regularly;

f) Trustees recognise the role of trustees in asset allocation, setting investment strategy and the selection, monitoring and retention of managers;

g) Trustees have risk management and continuity plans in place to deal with economic crises and market volatility, and clear governance structures in place in relation to long term financial sustainability of investments including consideration of climate change and ESG factors;

h) Trustees have good oversight of the communication strategies used to keep members informed about their investment options

101. Trustees should consider all of the points above when assessing whether they can demonstrate value for members in this area.

V) Level of trustee knowledge, understanding and skills to operate the pension scheme effectively

102. The knowledge, understanding and skills held across the trustee board as a whole can have a significant impact on the member experience and outcomes.

- Sections 247 to 249 of the Pensions Act 2004[footnote 19] and regulations made under those sections, set out the legislative requirements that trustees of occupational pension schemes must meet in terms of knowledge and understanding. TPR also provides guidance on trustee knowledge and understanding and scheme management skills[footnote 20]

103. When assessing the value for members delivered by their scheme, trustees should assess and explain how well they have performed against these requirements.

104. When seeking to demonstrate compliance, trustees should include reference to the following:

Whether sufficient time is spent running the scheme

- In their guidance, TPR suggests that board meetings should usually be held at least quarterly.

Diversity of trustee board in terms of background, experience and skills

- A variety of different skills, experiences and backgrounds should be evident on the Board as a whole and be relevant to meet the needs of the scheme. For example, the attributes of different board members might range from particular knowledge of investment matters to understanding the employer’s priorities to simply asking the right questions

Quality of leadership and effectiveness of board decision making

- The chair of trustees should also be able to demonstrate effective leadership skills. These include managing conflicts and adopting an inclusive approach which draws in the various skills and experiences across the members of the board. TPR recommends that the performance and effectiveness of the board should be evaluated annually. There are various ways of achieving this including peer review, questionnaire or the use of an external agency

Trustee Continuous Learning and Development

- Boards should be able to explain how they ensure that trustees have the necessary knowledge and understanding to carry out their role and act in the best interest of their members. TPR recommends all trustees keep a record of training undertaken and plans for future training to ensure that they possess, or are in the process of obtaining, appropriate knowledge and skills

Quality of working relationships with employer/third parties

- TPR suggests that the performance of advisers and providers will be reviewed at least quarterly by many schemes but that it may be appropriate for reviews to be less frequent for smaller, less complex schemes. They also recommend that trustees should be in regular contact with the employer in order to foster a constructive relationship

VI) Quality of communication with scheme members

105. The Disclosure Regulations set out the type of information that must be communicated to scheme members by trustees as a minimum.[footnote 21]

106. In addition to their statutory obligations, the following points should be considered by trustees as part of an assessment of the quality of communications with scheme members:

i) Information should be given to scheme members in an accurate, clear and concise way which is easy for them to understand. How well this is done could be assessed by feedback from scheme members, including the number of complaints about quality and quantity of information received.

ii) Scheme members’ individual preferences for mode of communication should be acknowledged and technology and digital platforms used as appropriate.

iii) The quality and timeliness of information in the following areas:

- Information and guidance in relation to the rights to transfer to another scheme

- The quality of guidance on spotting potential scams

- Information to help with decision making on investment options

- Information in the retirement wake up pack

- General signposting of members to various guidance bodies

- Information to help with decision making on pension saving, including, for example, an indication of the value at retirement and the impact of contribution levels on that value

107. To have demonstrated good value in this area we expect trustees to have concluded that they’ve met their statutory obligations, as well as explaining how they have met the expectations in points (i) to (iii) above.

VII) Effectiveness of management of conflicts of interest

108. Conflicts of interest may arise either among trustees, between trustees and the employer or scheme provider, or with service providers and advisers.

109. The pension scheme should therefore have:

i) a robust policy and written procedures in place that identify, manage and monitor conflicts of interest effectively, which is regularly reviewed;

ii) controls in place to ensure that all trustees are aware of the requirement to declare and discuss any potential conflicts;

iii) a conflicts of interest register in place to record and declare interests that is discussed at every Board meeting;

iv). controls in place to ensure that all conflicts of interest are declared upon appointment of trustees and other service providers.

110. We would expect trustees to have all 4 of points (i) to (iv) in place and be able to show that they have been followed and are effective in practice in order to demonstrate they have achieved value for members in their management of conflicts of interest.

Does the scheme governance and administration overall provide value for scheme members?

111. Having considered all 7 metrics within the theme of administration and governance trustees must decide if overall the administration and governance of the scheme provides good value for scheme members.

112. We would expect all of the metrics for administration and governance to be satisfied for a pension scheme to be able to demonstrate satisfactory value for members. In the event that one or more of the metrics are not successfully met then trustees should seriously consider the impact of this on the overall quality of administration and governance and the quality of services in general that members are paying for.

Deciding the outcome of the value for members assessment - does the pension scheme provide overall value for members?

113. Trustees should be able to explain how the scheme delivers on all 3 overall areas of this assessment:

- costs and charges

- net investment returns

- governance and administration

114. Trustees should not give excessive weighting to costs and charges in their assessment. In fact, we would expect trustees to give more weight to net investment returns, and to their ability to properly manage the scheme over the long term, as evidenced by their performance on governance and administration, rather than an over focus on costs and charges. A focus on driving down costs should not be at the expense of data quality or operational sustainability. Similarly, for some asset classes or investment strategies higher charges may be justified in terms of the returns achieved.

115. However, in cases where the costs and charges for their scheme are significantly higher than those that can be achieved in the market, for example for some small schemes compared to large master trusts, without a demonstrable, material difference in governance and/or investment return, we would normally expect trustees of these schemes to conclude that they are unable to deliver value for members.

116. Pension schemes are a long-term financial product and trustees should ensure members retirement savings are protected by an effective system of governance. Trustees who are finding governance standards challenging should consider their capacity to sustain effective operational resilience in the longer term.

How to value legacy funds

117. By ‘legacy funds’, this statutory guidance refers predominantly to funds with special features - typically, guaranteed annuity rates, defined benefit underpins and with-profits, whether those have a guarantee or are simply smoothed. Trustees of schemes with legacy funds should value these to determine what action to take going forward for the future of the scheme.

118. When such legacy funds are default arrangements, they should be compared with a range of other default arrangements, not just defaults with similar features. When legacy funds are self-select funds, they should be compared with similar funds in comparison pension schemes where present, or with the default arrangement if not.

119. It can be difficult for trustees to compare the value offered by these benefits with those from products currently available in the market. The market may not be able to provide such generous benefits in existing products.

120. However, trustees should not assume that benefits with such guarantees are automatically value for members. Trustees should compare the value available from modern products without guarantees, as well as, where appropriate, other guaranteed products – or the same products offered by other providers.

121. In particular, trustees of specified schemes should remember that they need to assess the value offered by their scheme in the round. Trustees should also consider their ability to provide long-term operational and financial stability for members.

122. In addition, trustees of specified pension schemes should not assume that it will be impossible to find an alternative scheme willing to accept transferring scheme members rights with guarantees. Some authorised Master Trusts will accept with-profits or other funds with guarantees that are underwritten by third party insurers. The issuers of the guarantees may accept the scheme members – sometimes via a process called ‘assignment’ - into an individual personal pension or a ‘section 32 buyout’.

123. Trustees of pension schemes offering guarantees, particularly if they may wish to exit pension provision, should consider contacting the issuer of the guarantee and a range of authorised Master Trusts to discuss their options.

124. Note that these are processes for valuing the legacy funds for the purposes of the value for members assessment. Where trustees are seeking to transfer the rights of scheme members to another pension scheme, for example, without consent under regulation 12 of the Occupational Pension Schemes (Preservation of Benefits) Regulations 1991,[footnote 22] the safeguards set out in the regulations – as well as trustees’ fiduciary duties – apply.

Valuing Guaranteed annuity rates

125. Guaranteed annuity rates (GARs) may offer particularly valuable rates of conversion of a pension pot into a guaranteed income stream for life. For the purposes of the value for members assessment, trustees should estimate the value of a GAR as follows:

- First, calculate the multiple by which the GAR exceeds the open-market rate for a comparable annuity. For example, a GAR of 8.00% for a level single life annuity at 65 is 50% higher than an open market GAR of 5.33%

- Second, calculate the average age of the membership who are in possession of a pension policy with a GAR (say, 55 years), and the percentage of the membership who have such a guarantee (say, 60%)

- Then calculate the annualised increased return which the average saver would need to receive to achieve an equivalent uplift to that offered by the GAR – while taking account of the proportion of the membership who are eligible for the guarantee

- For the example data above, a 4.1% annual increase in the investment return from age 55 would deliver a 50% higher pension pot by 65, when the GAR becomes available. However, as this is only available to 60% of members, the investment returns can be treated as 0.6 x 4.1 or 2.5% higher

- As the annual assessment in the chair’s statement measures the value of the scheme to members as a whole, the above illustrated assessment assesses the value of the guarantee spread across the whole of the scheme. However, as some members of a scheme may have guaranteed benefits and others may not, schemes may wish to consider the value they offer separately for each group of members. This process should be undertaken before a decision is made on the wind-up of the scheme

Valuing with-profits and DB underpins

126. While a with-profits fund or a DB underpin may offer guarantees, the practical value of such a guarantee should be measurable over the long term. Trustees should evaluate the net performance, charges and transaction costs of with profits in the same way as any other fund, but in doing so they should specifically select comparison schemes which are able to report net performance data over a long time horizon. When assessing value, trustees should also consider any terminal or annual bonuses in such schemes that could be lost on transfer.

Reporting the outcome of the Value for Members assessment

Chair’s Statement

127. The outcome of the detailed value for members assessment and an explanation of the assessment should be reported in the annual chair’s statement. This should also be published on a publicly available website.

128. Trustees should decide how to present the outcome of the value for members assessment in their chair’s statement, considering the communication needs and preferences of the scheme membership.

129. Trustees could approach this by providing a rationale in the chair’s statement to explain whether or not they have met all the required measures in the value for member’s assessment, then by summarising the results for members.

Scheme Return

130. The outcome of this value for members assessment should also be reported in the annual scheme return. The outcome of the previous value for members assessment (if one was carried out for the previous scheme year) should also be given. The annual scheme return will also give trustees space to set out which action(s) they intend to take if they have concluded that their scheme does not provide value for members.

131. Trustees who have concluded that their scheme does not provide good value for members will need to state in accordance with regulation 3(1)(hb) of the Register of Occupational and Personal Pension Schemes Regulations 2005 as inserted by regulation 3(2)(b) of the 2021 regulations, whether they propose to transfer the DC rights of their members into another scheme, and whether or not they also propose to wind up the scheme. If they do not propose to wind up the scheme they should also include their reasons for not doing so, along with what improvements they propose to make to ensure the scheme does provide good value for members.

Action following the Value for Members assessment

132. If, having completed the value for members assessment the trustees have concluded that the scheme does not provide value for members, then trustees should look to wind up the scheme[footnote 23] and transfer the rights of their members into a larger occupational pension scheme or personal pension scheme,[footnote 24] or set out the immediate action they will take to make improvements to the existing scheme.

133. There are likely to be costs involved in winding up/transferring members rights from a scheme. Sometimes the employer will agree to meet these costs. Members may also be liable for exit penalties upon leaving a scheme. Both these types of costs should not be considered as part of the annual value for members assessment as that is designed to assess the value of the scheme while in operation. However, when trustees are considering the best course of action after failing to demonstrate value for members then the level of wind up costs and exit penalties should then be considered.

134. We would expect the benefits of moving members to a better governed scheme with lower costs and potentially higher long term net returns to be considered very carefully, even if the wind up costs and exit penalties appear to be relatively high. Exit and wind up costs should not be an automatic barrier to winding up the scheme and transferring members rights into a larger occupational pension scheme or personal pension scheme.

135. In the event of a scheme not providing value for members, trustees should not wait until they report this in the annual scheme return before taking the necessary corrective action. Depending on when the scheme year ends, completion of the annual scheme return could be some months away. Trustees should start the wind up process or start making improvements immediately, and report this to TPR both in accordance with section 62(4) of the Pensions Act 2004, and when their next scheme return falls due.

136. If trustees do not take action to wind up/transfer the rights of members into another scheme then they must state the reasons for this in the annual scheme return to TPR. They must also, explain details of the steps they will now take to ensure that the scheme does deliver value for members. For example, if trustees strongly believe that there are only small areas of improvement required to raise scheme standards to levels that would deliver value, or that the resource commitment and cost of making those improvements is more favourable to members than the costs of winding up, then that option could be explored. However, this needs to be considered very carefully in the interests of members. The improvements should ensure members enjoy a continued level of good value for members in the long term.

137. Trustees should be aware that if the improvements identified are not made within a reasonable period, for example within the next scheme year, then trustees will be expected to wind up and transfer members benefits to another scheme.

138. It should also be noted that where a scheme has not completed wind up within seven months of the year end, trustees are required to prepare a chair’s statement before the seven-month period has elapsed. Failure to produce a chair’s statement within this period attracts an automatic penalty from TPR.

139. TPR also has the power to order the wind up of a pension scheme in certain circumstances.

-

A ‘relevant scheme’ is defined by Regulation 1(2) of the Occupational Pension Schemes (Scheme Administration) Regulations 1996. This definition includes most schemes that provide money purchase benefits while excluding defined benefit schemes. ↩

-

Regulation 1(3) of the 2021 Regulations defines when the regulations first apply. ↩

-

Regulation 1(4) of the 2021 Regulations defines when the regulations first apply. ↩

-

A relevant scheme which, on the relevant date (the date on which the trustees obtained the audited accounts for the scheme year that ended most recently): held total assets worth less than £100 million, and has been operating for 3 or more years. ↩

-

Definition of ‘relevant small’ schemes is found in regulation 1 (2ZB) of the Administration Regulations ↩

-

The Occupational Pension Schemes (Charges and Governance) Regulations 2015 ↩

-

A ‘specified scheme’ is defined by regulation 25(5) of the Administration Regulations, inserted by regulation 2(3)(c) of the 2021 Regulations. ↩

-

The Pensions Regulator: Winding up a defined contribution scheme ↩

-

The requirements that must be met by a ‘comparison scheme’ are set out in new regulation 25 (1D) of the Administration Regulations, as inserted by the 2021 Regulations. ↩

-

See paragraphs 42-44 of chapter 1 of Disclosure of costs, charges and investments in DC occupational pensions: Government response ↩

-

Pension charges survey 2020: charges in defined contribution pension schemes ↩

-

The Occupational Pension Schemes (Scheme Administration) Regulations 1996 ↩

-

The Pensions Regulator: Code 13: Governance and administration of occupational trust-based schemes providing money purchase benefits - Administration ↩

-

Section 49 of the Pensions Act 1995: Receipts, Payments and Records ↩

-

The Occupational Pension Schemes (Scheme Administration) Regulations 1996 ↩

-

Pensions Act 2004 c. 35 Obligations of Trustees of occupational pension schemes ↩

-

The Pensions Regulator: Trustee knowledge and understanding ↩

-

The Occupational and Personal Pension Schemes (Disclosure of Information) Regulations 2013 No. 2734 Part 2 ↩

-

The Occupational Pension Schemes (Preservation of Benefit) Regulations 1991. SI 1991/16 ↩

-

The Pensions Regulator: Winding up a defined contribution scheme ↩

-

The personal pension scheme should not be an investment regulated scheme within the meaning of Paragraph 1 of Schedule 29A of the Finance Act 2004 ↩