Independent review of The Pensions Regulator (TPR)

Updated 3 October 2023

Foreword

As Lead Reviewer, I am pleased to present this Departmental Review of The Pensions Regulator.

I would like to thank everyone who has contributed to this review. It has benefited from constructive engagement from TPR itself, from officials in the DWP, and from stakeholders in the industry, all of whom responded to my questions willingly and openly. I am very grateful to all those who gave their time to be interviewed and who shared their valuable insight and observations.

TPR is overall well-run, has a strong relationship with the DWP, and is generally well-regarded by its main stakeholders. Some regard it as overly risk averse, and in light of current policy debates about regulation and growth I have explored TPR’s risk-appetite and stance on growth in this report.

TPR has grown significantly in recent years, reflecting the addition of new responsibilities. With further remit expansion in the pipeline, there is a risk that TPR grows inexorably unless it can bring about a step-change in its ways of working – which it plans to do through digital transformation. TPR’s main challenge is pursuing its digital agenda in a way that meets its strategic ambitions yet provides enduring value for money.

There are big shifts underway in the UK pensions sector, as it transitions from a defined benefit to defined contribution basis, looks to increase contributions, and starts to explore new models such as superfunds and collective defined contribution schemes. The key recommendations in this report relate to addressing future challenges, both strategically and operationally.

I would like to thank the DWP team who supported this review for all their hard work, help and guidance.

Mary Starks

Addendum August 2023: This report was finalised prior to the Chancellor’s Mansion House speech on the 10 July, where a series of measures were announced to boost saver outcomes and increase funding liquidity for high-growth companies through reforms to the UK’s pension market.

Summary of Recommendations

TPR is broadly well-run and well-regarded, as reflected in its consistently strong performance in DWP’s annual assurance ratings, and TPR’s staff and stakeholder surveys. It has some notable successes in its track record, for example the implementation of Automatic Enrolment (AE). It has a coherent strategy focussed on clear outcomes with the interests of savers at its heart and holds itself to account against a range of key outcome and performance indicators. The recommendations in this report relate to areas for improvement but should be viewed against this positive backdrop.

I make 17 recommendations in this report. They are listed below, with a brief explanation of context for each (and fuller reasoning in the main body of the report). I highlight here three themes that came up in my discussions with stakeholders and that underpin the recommendations:

- risk and growth: following the Liability Driven Investments (LDI) event last autumn and broader policy concerns about productive finance, the question of how UK pension funds are invested has come under the spotlight. It is important that TPR plays an authoritative part in these policy discussions, as an informed and expert voice aligned with the interests of savers.

- compliance and enforcement: TPR has a thoughtful approach to driving compliance by both employers and pension schemes, based on facilitating and encouraging compliance where possible, backed up by enforcement action as necessary. This is effective at driving compliance but leaves some stakeholders questioning TPR’s appetite to punish wrongdoing. It is important that TPR is known for taking tougher action when necessary.

- digital transformation and value for money: TPR has grown significantly in recent years (in common with many other regulators) reflecting additional workload associated with EU exit and the pandemic, as well as the addition of new responsibilities. To avoid inexorable growth as its remit expands TPR must find ways to discharge existing functions more efficiently, and plans to do this through digital transformation. This represents a great opportunity to transform ways of working but also a significant risk of spending scarce budget badly. Getting this right should be a key focus for TPR’s leadership in the coming period.

The recommendations are set out below. I have not set out an explicit timeframe for implementation but believe the majority could be implemented within the coming year.

Efficacy

Regulatory responsibilities

The institutional framework for pensions regulation is split between trust-based schemes regulated by TPR and contract-based schemes regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). This gives rise to some concerns in principle (risk of issues falling between gaps, duplication for regulated entities, risk of regulatory arbitrage, confusion for customers). However, these risks appear to be well managed between the two regulators. It has also been suggested that TPR’s responsibilities for automatic enrolment could sit with an over-arching regulator for employment. However, there are no firm plans to create such a regulator at this stage. Therefore, I do not believe that there is a strong case for revisiting the institutional framework for pensions regulation at this point.

Recommendation 1: That TPR remains a standalone entity for the time being, albeit with continued strong lines of communication with the FCA, His Majesty’s Revenue & Customs (HMRC) and other public bodies. Longer term, DWP and His Majesty’s Treasury (HMT) should keep the institutional framework under review as pensions and employment policy and the pensions sector continue to evolve.

Objectives and duties with respect to the Pension Protection Fund

TPR’s statutory objective to minimise calls on the Pension Protection Fund (PPF) may drive it to be overly risk averse, particularly given the PPF’s strong funding position. With the advent of the Defined Benefit (DB) funding code, TPR should be in a good position to understand which schemes are taking too much risk and which could take more if they wanted. It should also be able to triage which schemes are on track for their long-term goals, which schemes need to take action to get back on track, and which schemes are unlikely to make it to buy out. Management of this last cohort should be co-planned by TPR and the PPF to maximise the benefit to savers.

Recommendation 2: Following the publication and implementation of the final DB Funding Regulations, TPR should work jointly with the PPF to manage DB pension schemes unlikely to make it to buy-out, in a way that maximises the benefit to savers.

Proposed objective on financial stability

The role of pension schemes and LDI instruments in last autumn’s gilts market volatility raised questions about how TPR fits into the regulatory framework for financial stability. Both the House of Lords Industry and Regulators Committee and the Bank of England’s Financial Policy Committee (FPC) have recommended that TPR be given a duty in respect of financial stability, a recommendation subsequently endorsed by the Work and Pensions Select Committee.

Recommendation 3: TPR to work with HMT and DWP to determine how TPR should best interface with the FPC on financial stability. This to include consideration of whether TPR should have a formal objective in respect of financial stability, as well as the powers, resourcing and information needed to fulfil such a role effectively.

TPR’s role in respect of growth and productive finance

There are ongoing policy debates about the role of UK pensions in ‘productive finance’ and about the role of regulators in economic growth. I do not believe that TPR should be given a statutory duty in respect of economic growth but – considering its statutory duty towards the interests of savers – it should have a view on how regulation can drive investment behaviour that is in savers’ best long-term interests. This includes a view on growth opportunity as well as downside risk, particularly for Defined Contribution (DC) savers who stand to benefit and lose directly from investment performance.

Recommendation 4: TPR to factor into the annual review of its corporate strategy its role in monitoring asset allocations and the likelihood of delivering good long-term outcomes for savers.

Scope and remit

The pensions supply chain is complex with many entities having influence over outcomes for savers, not all of whom are subject to regulatory or professional body oversight. There is a case for considering regulation of pension administrators, who are currently outside TPR’s remit, and the authorisation of professional trustees.

Recommendation 5: TPR to monitor evolution of the pensions supply chain in its strategy work and flag any concerns about gaps in regulatory oversight to DWP. DWP to work with TPR to understand the costs and benefits of extending TPR’s remit to cover pension administrators and introduce formal standards and authorisation for professional trustees.

Rule-making powers

The previous review recommended that DWP should consider the benefits of giving TPR rule-making powers in specific circumstances. This recommendation was not taken further due to other pressures, but I believe it should now be given proper consideration. While core pensions policy should sit clearly with DWP, there is a case for delegating day-to-day regulatory rulemaking to the regulator within constraints.

Recommendation 6: DWP to consider delegating day-to-day regulatory powers to TPR. DWP and TPR to jointly produce an options paper to include analysis of what areas of rulemaking could be delegated, and any legislative change necessary to enable this.

Enforcement strategy with schemes

TPR is not an enforcement-led regulator, choosing to focus primarily on enabling and supporting compliance, which it does to good effect. However, not all stakeholders believe that TPR is willing to use its most serious powers when necessary. This is partly because some of its powers are cumbersome to use. While I support TPR’s overall approach to driving compliance, it is also important that TPR is known to be willing and able to use its enforcement powers when necessary.

Recommendation 7: TPR to review its enforcement approach, resourcing, and communication around enforcement outcomes. DWP to consider the case for simplifying the regime for use of financial support directions (FSDs) at the next legislative opportunity.

Automatic Enrolment (AE) compliance

AE compliance is systematically monitored and is high. Nonetheless, The Pensions Ombudsman (TPO), MPs and the Minister for Pensions (MfP) do receive complaints from individuals about non-compliant employers. It is important that TPR continues to take action in this space and has a strategy for dealing with (i) rogue employers (this is likely to involve cooperation with other agencies who may have concerns about the same companies) and (ii) failing firms. However, at some point the cost of trying to drive out residual non-compliance will exceed the cost of compensating those affected.

Recommendation 8: TPR to consider whether there are cost-effective options to increase incentives to comply among smaller and financially weaker employers, and to secure contributions early from employers in financial difficulty.

Supervision strategy

With initiatives underway to drive consolidation across the pensions landscape in the future, TPR will still need to oversee a ‘long tail’ of small schemes for the time being. At the same time, it needs to provide effective oversight of large and sophisticated financial players. This means TPR’s supervision strategy will need to encourage consolidation among smaller schemes, whilst overseeing them in the meantime, and build capability to deal with the biggest players.

Recommendation 9: TPR to develop a strategy that drives consolidation among smaller schemes that are sub-scale and at risk of being badly run and also sets out its supervisory offer to deal with the largest, most sophisticated schemes. This to include consideration of the powers TPR might need to achieve this, as well as what additional capabilities it needs to invest in.

Governance

Panels

TPR has a well-resourced (if under-utilised) Determinations Panel, which allows it to draw on senior regulatory and enforcement expertise. By contrast it has no formal way to draw on pensions industry expertise and could benefit from having access to a cadre of senior staff recruited for this purpose.

Recommendation 10: TPR governance team to present options paper to TPR Board on access to, and utilisation of, senior regulatory, enforcement and sector expertise, with a view to ensuring TPR is accessing senior expertise through appropriate channels.

Executive Committee structure

TPR’s committee structure is complex, and a single decision can require approval from multiple committees. I understand the incoming Chief Executive Officer (CEO) plans to review decision-making processes and committee structure. Decision-making can only be streamlined effectively in combination with efforts to re-articulate risk tolerance and to establish an improved culture of autonomy and trust.

Recommendation 11: TPR to review its internal committee structure and risk framework with a view to stream-lining decision making at the appropriate level, giving due weight to cultural as well as procedural aspects.

Accountability

Impact reporting

TPR holds itself to account publicly against a range of key outcome and performance indicators. Nonetheless, impact reporting remains a work in progress and one which I encourage. A key challenge is being able to devote time and resource to doing it properly.

Recommendation 12: TPR to consider the next stage in the evolution of its approach to monitoring of outcomes and impact, with a focus on capturing lessons learnt. To include consideration of budget to devote to this activity, and where in the organisation this function should sit.

Efficiency

Delivering 5% efficiency savings

TPR has agreed a plan for delivering 5% efficiency savings. Further savings may be available from revisiting the AE operating model now that AE has been fully implemented. The Cabinet Office Public Bodies Corporate Function Benchmarking exercise also suggested modest efficiency gains are available in corporate functions.

Recommendation 13: TPR to review its plans for delivering 5% efficiency savings, with a particular focus on identifying further savings in addition to those already being realised through estate costs and the Capita insourcing.

Funding streams

It has been suggested that now AE employer compliance is moving into steady state, TPR could be fully funded by the pensions sector, rather than having an element of taxpayer funding. In my view this would be a sensible development but the timing needs consideration in light of the need to recover the significant deficit in the General Levy on pension schemes.

Recommendation 14: DWP, in consultation with HMT, to undertake an analysis of how TPR could be fully funded by the pensions sector to inform a recommendation to Ministers. This should account for timing given the levy deficit, and the appropriate distribution of costs across the industry.

Hybrid working

TPR staff have not returned to the office post-covid to the same extent as many other organisations. This partly reflects that TPR has more staff based outside Brighton than pre-pandemic. TPR is currently in the ‘test and learn’ phase of its hybrid working trial. In assessing the results of that trial, I encourage it to consider the distinct needs of staff in Brighton and staff based elsewhere as it develops its working policy going forward.

Recommendation 15: On completion of the ‘test and learn’ phase, TPR to review its policy on hybrid working and its estates policy outside Brighton.

Digital transformation

TPR’s ambition to become a data-led regulator is in keeping with broader regulatory trends and is the right ambition. TPR has started to consider factors including resource, investments, expected pay-offs and digital readiness of the sector but has some way to go to articulate its digital and data ambitions in detail and to make key choices about priorities and sequencing.

Recommendation 16: TPR to develop a clear strategy for digital transformation in terms of both invest-to-save and invest-to-improve measures. Within this, ensure that the best mix of in-house and external contracting is used to minimise costs and grow in-house skills and capability; and that sequencing and prioritisation of projects takes into account capability in the sector. TPR to design specific governance for digital transformation and to seek support from DWP for training in new ways of working and navigating Government Digital Services standard assessment process.

Levy Deficit

In recent years the General Levy has fallen significantly into deficit, following ministerial decisions not to raise the levy in line with costs. A remediation plan is now in place; nonetheless the existence of a deficit pushes already incurred costs onto future savers and reduces financial headroom and flexibility for the regulatory regime. There should be stronger measures to stop this happening in future.

Recommendation 17: DWP to develop and implement procedural controls to ensure TPR budgets and funding stay within agreed tolerances.

Scope and Purpose of the review

1. The report sets out the findings from the public bodies review of The Pensions Regulator (TPR), which is a non-departmental public body (NDPB), sponsored by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP), reporting to the responsible Minister on behalf of the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions.

2. TPR was last reviewed in 2019[footnote 1]; the full set of recommendations from that review is set out in Annex A. All the previous recommendations have since been implemented or made business as usual, apart from Recommendation 1; that DWP consider extending the rule-making powers of TPR. This was not fully considered after the review publication due to competing pressures resulting from Brexit and the pandemic, so this recommendation has been revisited within this review.

3. This review was undertaken during the early part of 2023, with support from a small review team within DWP. The review’s terms of reference, found in Annex B, were agreed by the Minister for Pensions and Secretary of State, in accordance with the recently updated Cabinet Office (CO) Public Bodies guidelines[footnote 2].

4. The review aims to provide a robust challenge to, and assurance of TPR. In doing so it draws on the structure and approach of the CO’s plan for future reviews, focussing on four key areas:

- governance

- accountability

- efficacy

- efficiency

5. CO guidance sets a requirement to identify efficiency savings of more than 5% in nominal terms as of 2022/23 budgets, to be achieved by Arm’s Length Bodies (ALBs) within 1-3 years of the review, unless a pre-existing efficiency savings target is already in place[footnote 3]. TPR has already identified a range of efficiency savings and I comment on these in this report.

6. The period of the review coincided with the end of the previous Chief Executive’s term, and the new Chief Executive starting in post. This is likely to entail some organisational and strategic review. Where plans are already in place, I reference these in the report, but I note that it is early days. I hope the incoming CEO will find this report useful; it is not intended to be constraining in any way.

7. In light of the above, and focussing on areas where this review can add value, I have considered:

- whether TPR is well set up to do its job within the wider systems of pensions and financial regulation, with appropriate objectives, powers and resources

- whether TPR is well set up to adapt and respond to future challenges, including the operational implications of the proposal that TPR should have a remit in respect of financial stability

- whether TPR is well governed, efficiently run and appropriately funded

- how well TPR is managing relationships with its key stakeholders, including the pensions industry, other public bodies in the pensions sector, DWP, and the other relevant departments and branches of Government

- whether there are opportunities to undertake activities in a more efficient manner, making best use of technology, and the case for increased expenditure to support digital transformation

8. In undertaking the review, I spoke with key TPR staff and over twenty external stakeholders, with meetings conducted both virtually and face-to-face, and received additional written communication from another two stakeholders. I also reviewed documentation provided from both TPR and DWP. This input suggested issues to explore in more depth and helped shape the findings of this report. I also attended a TPR Board meeting and visited the TPR offices in Brighton. A full list of the organisations interviewed is at Annex C.

Overview of TPR

9. In this section I outline TPR’s remit and provide an overview of:

- its size and funding

- its strategy and plans

- staff and stakeholder sentiment

10. I then turn to the context in which TPR is operating, with a brief overview of the pensions landscape and upcoming policy and regulatory developments.

The remit of TPR

11. TPR is the UK regulator of workplace pension schemes, working with trustees, employers, and business advisers in the public and private sectors. TPR’s statutory objectives are set out in the Pensions Act 2004[footnote 4], amended by the Pensions Acts 2008[footnote 5] and 2014[footnote 6]. These are:

- to protect the benefits of members of occupational pension schemes

- to protect the benefits of members of personal pension schemes (where there is a direct payment arrangement).

- to promote and to improve understanding of the good administration of work-based pension schemes.

- to reduce the risk of situations arising which may lead to compensation being payable from the PPF.

- to maximise employer compliance and employer duties and the employment safeguards introduced by the Pensions Act 2008.

- in relation to DB scheme funding, to minimise any adverse impact on the sustainable growth of an employer

12. TPR’s role has grown in recent years with new powers introduced for the regulation of Master Trusts in the Pensions Schemes Act 2017[footnote 7]. In addition, the Pension Schemes Act 2021[footnote 8] introduced new powers to penalise reckless behaviour, Collective Defined Contribution (CDC) Schemes, and new requirements related to Climate Change risk and DB funding.

Size and funding[footnote 9]

13. TPR has 928 payroll full-time equivalent (FTE) and 59 contractor FTE staff on 31 May 2023 and is funded through grant-in-aid from DWP, with a total expenditure in 2022/23 of £104.7 million (including capital expenditure).

14. TPR comprises two distinct operating segments: employer compliance with the AE regime; and the regulation of new and existing DB and DC schemes. These are currently separately funded and operationally distinct.

15. The regulation of occupational pension schemes is funded through the General Levy charged on occupational and personal pension schemes in the United Kingdom. It is paid as a Grant-in-Aid[footnote 10] from DWP, and costs are offset by levy income. AE is taxpayer funded through a separate Grant-in-Aid stream from the DWP, and resources are charged and treated separately from levy funded activities.

16. TPR’s budget is allocated on an annual basis following conversations with DWP Partnership, Policy and Finance officials, with final clearance through the Minister for Pensions. The budget conversation considers business as usual requirements alongside ministerial priorities and policies.

17. Table 1 and Figure 1 below look at expenditure over time against budget. In 2022/23, TPR had a net expenditure of £104.7m (including capital expenditure), of which £68.1m related to levy-funded activities and £36.6m was attributable to AE.

18. For the past two years actual expenditure on AE was lower than the allocated budget. This was due to lower than forecast spend on projects, and savings associated with AE transformation, IT contracts, and other professional services. There was, in addition, a small underspend on the General Levy budget, predominately relating to the move to new premises and lower than expected expenditure on IT.

19. From 2018/19 total expenditure grew each year until 2020/21, reflecting growth in both TPR’s AE and regulatory activities. The small decrease in 2021/22 came from reductions in temporary resource, the refocusing of the profile of IT contract spend on multi-year Microsoft licences, delayed project spend and case costs, offset by increases in salaried spend and depreciation. In 2022/23 net expenditure reflected continued growth in the TPR workforce offset by a full year of savings from the AE Transformation project.

Table 1: Actual expenditure and budget over time

| £ million | 2018-2019 | 2019-2020 | 2020-2021 | 2021-2022 | 2022-2023 | 2023-2024 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Expenditure | 85.7 | 93.6 | 105.1 | 102.0 | 104.7 | – |

| Levy Expenditure | 50.9 | 56.9 | 66.8 | 62.4 | 68.1 | – |

| AE Expenditure | 34.9 | 36.7 | 38.3 | 39.6 | 36.6 | – |

| Total Budget | 88.6 | 99.0 | 104.4 | 111.9 | 117.3 | 121.7 |

Source: TPR management accounts

20. TPR’s Corporate plan[footnote 11] sets out how the 2023/2024 budget is forecast to increase. The increase is down to increased spend on specific new initiatives such as Pension Scams Action Group, CDCs, and climate change regulation[footnote 12] and planned expenditure to deliver against the accommodation strategy.

21. Table 2 sets out the average number of FTE persons employed (including employees and contractors), broken down by department. Staffing levels have increased significantly in recent years – by over one third since 2019/20. Much of the increase in AE headcount has come from bringing the majority of TPR’s AE functions in-house (these were previously outsourced to Capita). The other areas of significant headcount increase are Data, Digital and Technology, Projects, and Strategy and Communication. I understand some of this increase is temporary resource.

Table 2: Average number of persons employed (FTE) over time

| 2019-2020 | 2020-2021 | 2021-2022 | 2022-2023 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AE Direct | 97 | 95 | 122 | 141 |

| Case Costs | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Corporate Services | 95 | 116 | 103 | 110 |

| Data, Digital and Technology | 69 | 78 | 93 | 115 |

| Frontline Regulation | 211 | 228 | 224 | 227 |

| Governance, Risk and Assurance* | 26 | 23 | 47 | 51 |

| Human Resources | 19 | 25 | 26 | 28 |

| Projects | 19 | 52 | 70 | 82 |

| Regulatory Policy, Analysis and Advice | 120 | 112 | 116 | 124 |

| Strategy & Communications* | 52 | 63 | 62 | 67 |

| Total | 709 | 791 | 862 | 952 |

Source: TPR management accounts *Governance, Risk and Assurance and Strategy and Communications did not exist until April 2022, when different teams were brought together.

22. Considering the growth in TPR’s budget and headcount, I have attempted to benchmark its size relative to that of the FCA. (The respective responsibilities of the FCA and TPR for pensions are discussed in the Efficacy section). It is impossible to make a robust like-for-like comparison, however I note that the FCA employs around 4000 staff[footnote 13] In terms of its pensions responsibilities, it regulates the providers of contract-based DC schemes, with around 31 million members and £728 billion assets in accumulation, of which approximately 12 million members and £260 billion assets are in workplace pension schemes[footnote 14].

It also oversees the wider investment management sector and banking sector, worth £trillions[footnote 15]. In total it regulates around 50,000 firms[footnote 16].

23. TPR employs under 1000 staff. It regulates trust-based occupational pension schemes, covering almost 10 million members of just over 5,000 DB schemes with £1,700 billion in assets, and 18 million members of trust-based DC schemes (including master trusts), with £218 billion in assets[footnote 17]. In addition, it oversees the compliance with AE of around 1.5 million employers[footnote 18]

24. In my view, this comparison does not immediately suggest that TPR has become too big relative to the role it plays. Nonetheless I explore the potential for efficiency gains in a later section.

Strategy and plans

25. TPR published its first corporate strategy in 2021[footnote 19]. This strategy explicitly focussed on outcomes for groups of pensions savers (segmented by age and wealth). It looked at each group’s reliance on DB, DC, state pension, and other long-term savings; the different challenges facing each group; and the major trends that TPR expects will shape retirement savings over the next 15 years.

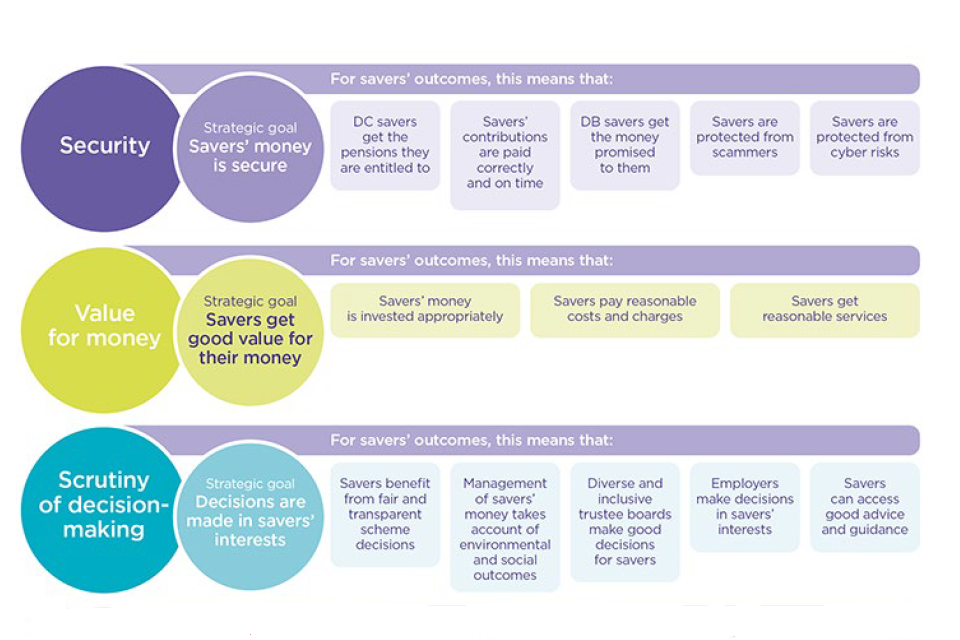

26. The strategy sets out five focus areas, illustrated below:

The above illustration shows strategy focus areas 1 to 3 for security, value for money and scrutiny of decision making. Further information is given in paragraphs 25 to 30.

Source: TPR

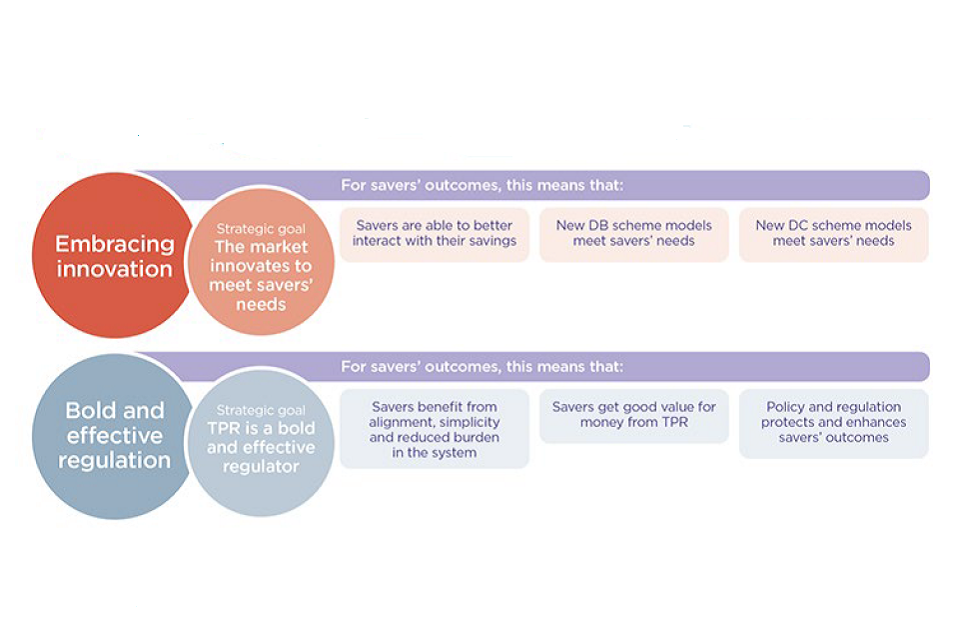

The above illustration shows strategic focus areas 4 and 5 for embracing innovation and bold and effective regulation. Further information is given in paragraphs 25 to 30.

Source: TPR

27. TPR operates a three-year strategy cycle, with an annual review to update for any changes to the regulatory landscape or other developments. It has concluded the first three-year cycle and is embarking on the second cycle. This has included re-analysing the risk picture and validating the approach with its Board.

28. TPR recently released its Corporate Plan[footnote 20] for 2023/24, outlining its priority activity and milestones for the upcoming year across all five strategic priorities. These are summarised in the table below:

Key activities and milestones 2023/24 (table 3 in the PDF)

Strategic priority: Security

- preparing for the launch of our DB funding code and regulatory framework in 2024

- improving how we monitor and assess market risks and events

- developing our relationship supervision team, including working with further administrators in Q1

- delivering year 2 of our pension scams strategy

- developing AE operations so they are more efficient and effective in the long term

Strategic priority: Value for money

- contribute to the joint consultation response on the value for money framework — Q2

- develop a value for money policy with the FCA and DWP

- undertake a regulatory initiative on value for member assessments

- engage with administrators and increase engagement levels in Q1

Strategic priority: Scrutiny of decision-making

- publishing our general code in Q1

- commencing our regulatory initiatives on equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI) and climate change in Q1

- delivering a range of activities to support our commitment to climate change

- creating an option analysis on the future regulation of governance and trusteeship — Q4

Strategic priority: Embracing innovation

- reviewing our DB superfunds guidance

- assessing authorisation applications for DB superfunds and CDC schemes and carrying out ongoing scheme supervision

- helping the pensions industry to prepare for pensions dashboards

Strategic priority: Bold and effective regulation

- delivering our supervision strategy in Q1

- delivering against our AE operational strategy

- completing our internal value for money pilot and set out recommendations

- embedding our digital, data and technology (DDaT) directorate

- net zero plan in Q4

29. It also provides an overview of plans beyond March 2024. This includes:

- a new “twin track” approach to oversight of DB valuations (comprising both “fast track” and “bespoke” engagements).

- streamlining AE compliance work to make it more targeted and risk-based.

- embedding the value for money framework - monitoring outcomes and taking remedial action where poor value schemes remain in the market.

- work on protecting value at decumulation for DC savers.

- further policy work on professionalisation of trustees, together with DWP.

- delivering new regimes for authorising and overseeing new models (DB superfunds and CDC schemes)

- build digital platforms for engaging with the regulated community to capture and analyse data and streamline operations

30. In my view these plans are coherent and well-aligned with TPR’s longer-term strategy, with clear milestones allowing stakeholders (including both the regulated community and DWP) to track progress.

Staff and stakeholder sentiment

31. TPR staff engagement has been improving in recent years and is now high. The overall employee engagement score was 72% for 2022. It was 72% in 2021, 62% in 2020 and 58% in 2019[footnote 21]. While staff raised a few specific issues with me, which I cover in the following chapters, these figures show that specific concerns were raised against an overall positive backdrop.

32. TPR is generally well-regarded by stakeholders. Figure 2 shows results from TPR’s most recent (2022) stakeholder survey, demonstrating consistently positive results over several years. Annex F shows a more detailed analysis by activity.

Figure 2: Stakeholder rating of TPR’s overall performance as a regulator

| 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poor | 2% | 2% | 1% | 1% | 1% |

| Fair | 27% | 23% | 17% | 21% | 22% |

| Good | 51% | 54% | 58% | 54% | 50% |

| Very Good | 14% | 16% | 17% | 15% | 21% |

| Don’t know | 6% | 5% | 7% | 9% | 6% |

Source: TPR internal analysis of their Perceptions tracker Pensions research and analysis – The Pensions Regulator

33. The survey results[footnote 22] show that most stakeholders were favourable towards TPR. Stakeholders praised TPR for performing its role well and recognised that the job is often a difficult one given its challenging remit, its expanding powers and sheer volume of recent developments within the industry, the uncertain economic climate and general global instability. Caveats to this favourability included a perceived lack of resourcing, which was also raised with me during this review.

34. Stakeholders raised a number of specific additional issues in discussions with me, which I cover in the following chapters. But again, the survey figures demonstrate that specific concerns were raised against an overall positive backdrop.

Pensions landscape

35. The shift in workplace pensions away from DB towards DC and the introduction of AE are changing the pensions landscape profoundly. Around half of DB schemes are now closed to benefit accrual[footnote 23], while over 10 million employees have been AE in DC schemes in the decade since the programme began.

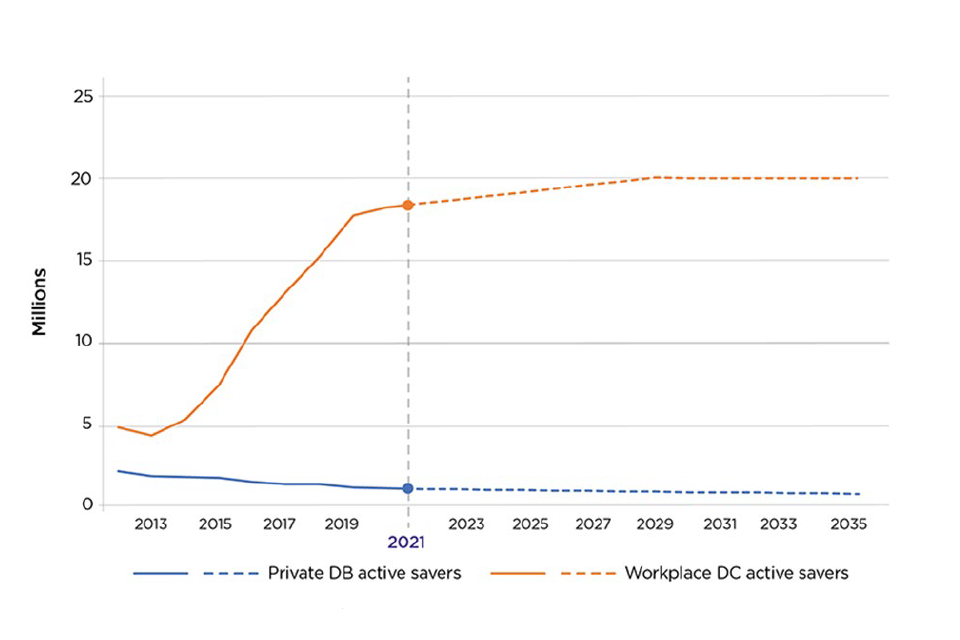

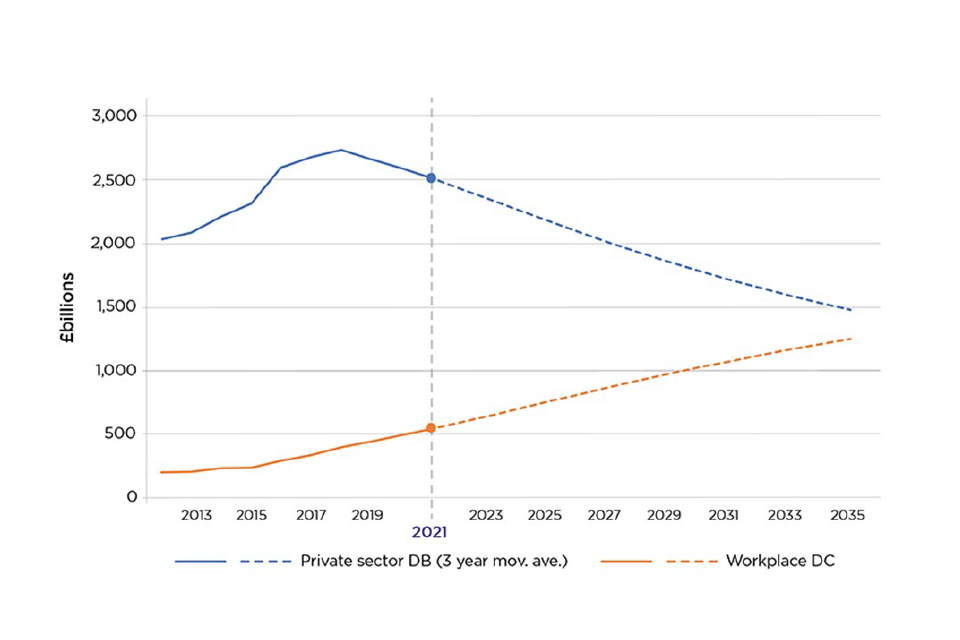

36. Many more savers are now enrolled in DC than DB schemes. However, many DC savers have relatively little pension wealth; the majority of pension assets are still within DB schemes, as illustrated in Figure 3. This is likely to remain the case for some years.

Figure 3: Memberships and Assets in DB and DC Schemes over time

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DB Active Membership (millions) | 2.1 | 1.91 | 1.81 | 1.75 | 1.44 | 1.31 | 1.28 | 1.1 | 1.08 | 0.98 | 0.93 |

| DC Active Membership (millions) | 0.98 | 1.29 | 3.07 | 4.51 | 5.87 | 7.43 | 9.23 | 9.98 | 10.22 | 10.17 | 11.18 |

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DB Assets (£bn) | £1,027 | £1,119 | £1,138 | £1,298 | £1,341 | £1,541 | £1,573 | £1,615 | £1,701 | £1,721 | £1,667 |

| DC Assets (£bn) | £23 | £26 | £27 | £34 | £39 | £48 | £61 | £71 | £87 | £114 | £143 |

Source: *DC: DC trust: scheme return data 2022 to 2023 annex, The Pensions Regulator *DB: Purple book, Pension protection Fund

Notes: DC Assets data does not include hybrid schemes, but active memberships numbers do. DC data is for trust-based schemes only

37. TPR’s strategy is clear on these shifts and on the need to evolve its activities and focus in the coming years.

Figure 4: Active DB and DC savers – includes projected figures until 2035[footnote 24]

The above graph shows the increase in workplace DC active saver numbers from about 5 million in 2013 to about 18 million in 2021. This is projected to rise to about 20 million by 2035. Also shows a decline in private DB active savers from about 2 million in 2013 to about 1 million in 2021. This is projected to decline further by 2035.

Source: Corporate Strategy Pensions Future, The Pensions Regulator

Figure 5: DB obligations/DC assets under management (AUM) including projected figures until 2035[footnote 25]

The above graph shows DB obligations rose from about £2 billion in 2013, peaked at about £2.7 billion in 2017 and then dropped to about £2.5 billion in 2021. The figure is projected to drop to about £1.5 billion by 2035. Also shows workplace DC assets increased from about £200 billion in 2013 to about £500 billion in 2021. It’s projected to continue to rise to about £1.3 billion by 2035.

Source: Corporate Strategy Pensions Future, The Pensions Regulator

38. The market is seeing consolidation of schemes, in both DB and DC, as illustrated in Figure 6 below. However, there are a very large number of micro schemes which continue to exist, as shown in Figure 7. Both DWP and TPR expect and plan for consolidation to continue, meaning in future TPR will need to regulate a smaller number of larger schemes, which will present a different set of regulatory challenges. I return to this below.

Figure 6: Number of DB and DC schemes with 12 or more members over time

| Year | DB Schemes | DC Schemes |

|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 7,751 | – |

| 2007 | 7,542 | – |

| 2008 | 7,400 | – |

| 2009 | 7,098 | – |

| 2010 | 6,850 | – |

| 2011 | 6,550 | – |

| 2012 | 6,460 | 3,660 |

| 2013 | 6,225 | 3,240 |

| 2014 | 6,070 | 3,080 |

| 2015 | 5,967 | 2,930 |

| 2016 | 5,886 | 2,740 |

| 2017 | 5,671 | 2,470 |

| 2018 | 5,524 | 2,180 |

| 2019 | 5,436 | 1,980 |

| 2020 | 5,327 | 1,740 |

| 2021 | 5,220 | 1,560 |

| 2022 | 5,131 | 1,370 |

| 2023 | – | 1,220 |

Source: *DC: DC trust: scheme return data 2022 to 2023 annex, The Pensions Regulator *DB: Purple book, Pension protection Fund

Figure 7: Micro DC trust schemes by relevant small schemes (RSS) status (excluding hybrid schemes) 2016 to 2023[footnote 26]

| Date | RSS | Non-RSS | Unknown | Number of Schemes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01/01/2016 | 22,500 | 5,050 | 5,330 | 32,880 |

| 01/01/2017 | 22,930 | 4,360 | 4,710 | 32,000 |

| 01/01/2018 | 22,070 | 3,670 | 4,790 | 30,530 |

| 01/01/2019 | 21,930 | 3,200 | 4,220 | 29,340 |

| 01/01/2020 | 21,860 | 2,050 | 3,860 | 27,760 |

| 01/01/2021 | 21,750 | 1,670 | 3,300 | 26,720 |

| 01/01/2022 | 21,970 | 1,520 | 2,770 | 26,260 |

| 01/01/2023 | 21,100 | 1,340 | 3,260 | 25,700 |

Source: DC trust: scheme return data 2022 to 2023, The Pensions Regulator

Upcoming policy and regulatory developments

DB schemes:

39. TPR is preparing for the launch of the new Defined Benefit Funding Code. The Code will provide practical guidance to trustees and sponsoring employers on how to comply with the new scheme funding legislation. This legislation will require DB schemes to have a funding and investment strategy that ensures pension and other benefits can be paid over the long term. Schemes will be required to report progress against targets to TPR. This will strengthen TPR’s ability to enforce DB scheme funding rules and enable TPR to intervene more effectively by making it easier to assess scheme risks and target interventions. Subject to Parliamentary approval, DWP and TPR are planning for both the Defined Benefit Funding Code and the Occupational Pension Schemes (Funding and Investment Strategy and Amendment) Regulations 2023 to come into force from April 2024.

40. In 2018 DWP consulted on a number of measures to support the consolidation of DB schemes including a new legislative and regulatory regime for superfunds. A superfund is a commercial consolidator – a multi-employer DB scheme backed by private capital, which takes on responsibility for paying members’ benefits.

Superfunds are designed to improve the likelihood that members of a closed DB scheme will get their full benefits and offer a new way for employers to remove the scheme from their balance sheet. TPR has been regulating on an interim basis, pending the outcome of the consultation and legislation underpinning an enduring regime. Stakeholders I spoke to expressed frustration at the slow progress towards an enduring regime, and the impact of the delay on the nascent market: only one superfund has so far been authorised (Clara Pensions, assessed prior to publication). However, I understand that DWP remains committed to responding to the consultation and to legislating when parliamentary time allows. In the meantime, DWP is working with TPR to review the interim regime and ensure the market develops in a controlled manner with clear standards and requirements in place.

DC schemes:

41. DWP, TPR and the FCA are working closely together to develop a Value for Money (VfM) framework and regulatory regime. A policy consultation ran from January to March 2023 and in the consultation response published in July, DWP, TPR and the FCA set out proposals for a framework of metrics, standards, and disclosures to assess value for money across DC schemes[footnote 27]. The framework is designed to improve retirement outcomes and increase the levels of transparency and competition in the pension sector. The framework also proposes new powers for regulators to enforce the consolidation of consistently underperforming schemes.

42. This builds on the introduction of a statutory obligation in 2021 for smaller schemes (under £100m in assets) to conduct a Value for Members assessment, with a view to requiring schemes to consolidate if they cannot offer good value for members[footnote 28]. There have been reports that many schemes were unaware of this obligation[footnote 29].

43. Once the VFM framework is introduced, it will replace the Value for Members assessment. In the meantime, the Value for Members assessment has a key role to play in helping trustees focus on the value their scheme provides, including net investment returns, costs and governance, and in prompting underperforming schemes to improve, wind up or consolidate.

CDC schemes:

44. CDC schemes provide an alternative to traditional DB and DC pension schemes. In CDC schemes, member and employer contributions are pooled in a collective fund from which an aspired to pension income for life is drawn. From a saver perspective, the advantage over DC is that longevity and investment risks are pooled. From an employer perspective, the advantage over DB is that costs are predictable. The legislative framework for single and connected employer CDC schemes came into force in August 2022 and in April 2023 TPR authorised the first such scheme. TPR is currently working with DWP to develop the appropriate regulatory framework for unconnected multi-employer CDC schemes, CDC master trusts[footnote 30] and CDC decumulation products which will increase the number of employers and members who can benefit from such schemes.

Automatic Enrolment (AE):

45. October 2022 saw the 10-year anniversary of AE into workplace pensions. More than 10.8 million workers have been enrolled into a workplace pension to date[footnote 31], saving around an additional £32.9 billion in real terms in 2021 compared to 2012[footnote 32]. Future ambitions for AE are to give lower earners, including those in part-time work, greater opportunity to build retirement savings and to enable 18 to 21-year-olds to start building a pension from their first day in work, through implementation of the 2017 AE review measures. The necessary legislation to provide enabling powers is currently before parliament, before looking at further changes to the AE framework, recognising the current minimum contribution of 8% on a band of earnings is unlikely to support the retirement lifestyle to which most individuals aspire.

46. TPR, DWP and the Department for Business and Trade (DBT) continue to work on the complex issue of ‘gig’ economy workers. DWP’s view is that many gig economy workers are already eligible for AE, including those on fixed term contracts, zero-hours contracts and agency workers. TPR acts primarily on the basis of findings of Employment Tribunals on the status of workers. It has to date opened eight investigations involving gig economy operators, mainly in the delivery sector (people, goods, food). TPR estimates that through its enforcement action to date, around 100,000 workers have been automatically enrolled and around £100m has been paid into their pension savings through backdated contributions by the operators involved.

Efficacy

47. In this section I consider TPR’s scope and remit, and whether it is well set up to discharge its responsibilities. This includes specific consideration of:

- whether TPR meets the CO’s three tests for an arm’s length body.

- whether the split of responsibilities between TPR and the FCA is appropriate and well-managed.

- whether TPR’s duty to minimise calls on the PPF drives undue risk aversion

- the implications of including financial stability within TPR’s remit.

- whether TPR should have duties in respect of growth or productive finance.

- whether TPR’s remit should be extended to pension administrators, or other currently unregulated pensions industry participants and authorisation of professional trustees.

- whether the balance of rule-making powers between DWP and TPR is appropriate.

- whether TPR is set up to make good use of its enforcement powers.

- future issues for TPR to address as part of its supervision strategy.

Form and Function

ALB status

48. CO guidance[footnote 33] outlines three criteria for classification of an organisation as an ALB; of which at least one of the three tests must be met:

- is this a technical function, which needs external expertise to deliver?

- is this a function which needs to be, and be seen to be, delivered with political impartiality?

- is this a function that needs to be delivered independently of ministers to establish facts and/or figures with integrity?

49. In my view TPR meets all three tests above. There is a clear need for specialist expertise, related to pensions policy but also actuarial skills, enforcement and legal expertise. Decisions (such as enforcement) require political impartiality, as with all regulators of powerful interests. I will discuss further, in the section on rule making powers, whether the line between Government policy and independent regulation is drawn in the right place. I also note in respect of the final test, this will be increasingly important if TPR is asked to contribute facts and data to financial stability discussions.

Split of regulatory responsibilities between TPR and the FCA

50. Pension schemes in the UK can be trust-based or contract-based. Trust-based schemes are governed by a trust deed and overseen by pension fund trustees, while contract-based schemes are governed by individual contracts between the member and the scheme provider[footnote 34]. Trust-based schemes (which include all DB schemes, and some DC schemes) are regulated by TPR, while contract-based schemes (all DC) are regulated by the FCA.

51. Figure 8 below illustrates this division of responsibilities and the scale of each regulator’s coverage, in terms of scheme members and pension assets.

Figure 8: TPR and FCA responsibilities[footnote 35]

| DB Workplace Pensions | DC Workplace Pensions | Non-workplace Pensions | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TPR regulated (Trust-based) | £1,700 billion – 9.9m members | Trust-based £218 billion – 18.2 million members | – |

| FCA regulated (Contract-based) | – | Contract-based £260 billion – 12 million members | Contract-based £468 billion – 18.7 million members |

Source: TPR

52. I understand this split responsibility for pension regulation is a result of history more than design. The question arises, therefore, whether there is a case for combining pensions regulation within a single body, for example by merging TPR and the FCA.

53. This question was considered in the Tailored Review of TPR in 2019[footnote 36]. The review concluded that the two organisations are distinct in their missions and would not benefit from being merged into one body.

54. Among the stakeholders I spoke to, no-one argued that the status quo was optimal, but most did not feel there was an urgent case for change, noting joint work on areas of common interest and generally good working relationships between the two organisations. For example:

- TPR and the FCA published an update to their joint strategy in 2022[footnote 37]. It addresses the issues facing the pensions sector and outlines priorities over the next five years, including improving consumer protection, promoting competition and combating financial crime. It also emphasises the importance of collaboration between both organisations in ensuring effective oversight of the industry.

- TPR, the FCA and DWP have also consulted jointly on the VfM framework[footnote 38]. The consultation (which closed in March 2023) set out metrics and standards to assess value for money across both trust- and contract-based pension schemes, to enable comparisons between different schemes’ costs and charges, investment performance and service standards.

55. Some stakeholders raised concerns in principle, related to risks of issues falling between gaps, duplication of effort for regulated entities, risk of regulatory arbitrage, and confusion for customers. However, most felt these risks were fairly well managed. The clearest example brought to my attention of actual harm was the British Steel pension liberation scams, where one stakeholder argued that a unified regulator would have been better placed to anticipate and mitigate this risk, for example by staggering the process so that fewer savers were facing major decisions at the same time and ensuring the right support was in place.

56. Stakeholders also raised significant questions around the future of DC pensions policy that go beyond the issue of having two regulators. These included:

- regarding consolidation of weaker schemes, there exists a mechanism for trust-to-trust transfer but there are no straight forward mechanisms for trust-to-contract transfer, even where this might be in savers’ best interests.

- AE is premised on low engagement, while pensions freedoms are premised on engagement. In a contract-based world (underpinned by the FCA’s consumer duty) firms can and do support customers through the transition to retirement; in a trust-based world there is no similar regulatory framework, but DWP are consulting on this.

57. While these are important questions, they are beyond the scope of this review.

58. The gilt market volatility of September 2022 tested regulatory coordination under pressure. The stakeholders I spoke to felt that communication and decision-making between TPR and the FCA had worked well on the whole.

59. Taking all this into account, I do not recommend a change to the institutional framework at this time, since it is far from clear that the benefits of shifting to a single regulator outweigh the costs and risks of distraction. Experience suggests that merging public bodies can be more difficult than first apparent, particularly where the two regimes have different legal bases. (For example, in 2007 the Government accepted a recommendation to merge TPO and the Financial Ombudsman Service (FOS), but this was abandoned once the legal complexities were properly examined). I note also that TPR’s responsibilities for employer compliance would not sit well with the FCA (I discuss these responsibilities further below).

60. Instead, I recommend TPR and FCA continue to work collaboratively on areas of common interest and to monitor and mitigate the risks to which the split regulatory framework gives rise. Policy discussions around TPR having an explicit role with respect to financial stability (discussed in more detail below) raise the possibility of closer cooperation with the FCA in areas such as data and analysis.

61. Longer-term DWP and HMT should keep the institutional framework under review, in parallel with the evolution of pensions policy.

Regulatory framework for employers

62. Several stakeholders noted that TPR’s responsibilities for AE were essentially employment regulation rather than financial regulation.

63. TPR works with HMRC on AE compliance. Specifically, TPR can access certain HMRC data to detect when employers may be failing to make AE contributions. One stakeholder suggested HMRC might be better placed to ensure compliance through automatic collection of AE contributions (akin to national insurance contributions).

64. TPR staff and other stakeholders recognised that in many cases employers who are failing on their AE duties may also be failing on other duties (e.g. tax, health and safety) for example “rogue” employers, or businesses under severe financial pressure.

65. The idea of a unified employment regulator was proposed by Government in 2018[footnote 39] but has not been taken forward. In April, the Resolution Foundation concluded a programme of work on labour market enforcement[footnote 40], recommending the introduction of a single enforcement body (SEB) – this would go further than the Government’s 2018 proposal and would include employers’ AE duties.

66. While the question of employment regulation is far broader than the scope of this review, any future review of the institutional framework for pensions regulation should obviously take account of any further developments in this space.

67. In the meantime, I understand TPR is keen to explore the potential for sharing data and intelligence on non-compliant employers with HMRC and other public bodies.

Recommendation 1: That TPR remains a standalone entity for the time being, albeit with continued strong lines of communication with the FCA, HMRC and other public bodies. Longer term, DWP and HMT should keep the institutional framework under review as pensions and employment policy and the pensions sector continue to evolve.

Objectives and duties

68. TPR’s objectives, duties and scope of remit are set out in the Overview section above. For the most part, stakeholders felt these were appropriate. However, there were some questions raised, which I cover in the following sections.

Objective with respect to the PPF

69. Stakeholder feedback indicates a strong working relationship between the PPF and TPR. The PPF is well-funded and believes it has a surplus over the reserve it needs to meet future compensation payments[footnote 41]. In light of the PPF’s healthy funding level, some stakeholders questioned whether it was right that TPR should have an objective to minimise calls on the PPF, or whether this objective was driving excessive risk aversion in regulation of DB schemes. To put it another way, having created a backstop to address the risk of scheme failure, it is odd for the regulator to have a statutory objective to avoid using it, and this potentially drives a degree of risk aversion that is not in savers’ best interests.

70. However, the PPF is an important safeguard for DB savers, but not a complete one. If a pension fund cannot meet its liabilities and a call on the PPF is made, savers are only compensated to around 90%, and the shortfall can be considerably greater for those who are still in accrual. For as long as this remains the case, it will be strongly in the interests of affected savers to be paid out by their scheme rather than be compensated by the PPF – the more so for those still in accrual.

71. With half of all DB schemes now closed to accrual the window for schemes to take action to improve their funding position and avoid calls on the PPF is closing. As noted above, the DB funding code will drive transparency about whether schemes are on track to meet their liabilities.

72. It is likely to become apparent that there is a cohort of closed schemes that are not on track, and for which a call on the PPF is increasingly likely. For this cohort TPR and PPF should work together in the best interests of savers, for example engaging ahead of insolvency in pre-transition planning. It will be in savers’ best interests for TPR to approach this pragmatically and be realistic about the scale of the challenge, and for both PPF and Government to be supportive on this.

73. There is a further question about whether it is in the best interests of savers in the round for PPF compensation to be significantly discounted in some cases. However, this concerns the overall allocation of risk in the pensions system and is beyond the scope of this review.

Recommendation 2: Following the publication and implementation of the final DB Funding Regulations, TPR should work jointly with the PPF to manage DB pension schemes unlikely to make it to buy-out, in a way that maximises the benefit to savers.

Proposed objective on financial stability

74. The role of pensions schemes’ use of liability-driven investment (LDI) in last autumn’s gilts market volatility raised new questions about the significance of pension funds for financial stability, and about how TPR fits into the regulatory framework for financial stability. This has historically been focussed on banks and, to a lesser extent, insurers and is overseen by HMT and the Bank of England’s FPC.

75. This review has not looked in any detail at the events of Autumn 2022 and does not seek to make recommendations about financial stability. However, other reviews have considered whether TPR’s remit should be expanded to include financial stability, and I have considered the strategic and operational implications of this.

76. In a letter[footnote 42] to the Economic Secretary to the Treasury and the Minister for Pensions in February 2023, Lord Hollick, Chair of the Industry and Regulators Committee called for action to improve regulation and reduce the risk of disruption caused by the use of LDI strategies by DB pension funds. The letter recommended, amongst other things, that TPR should be given a statutory duty or ministerial direction to consider the impacts of the pensions sector on the wider financial system. It also recommended that the FPC should be given the power to direct action by regulators in the pensions sector if they fail to take sufficient action to address risks.

77. On 29 March 2023 the FPC published its recommendations to TPR on LDI funds[footnote 43], which were:

- that TPR specify minimum levels of resilience to ensure funds are resilient to a yield shock of 250 basis points, with the expectation that to manage any day-to-day volatility funds maintain levels above this.

- that TPR have a remit to take into account financial stability considerations, for example through a requirement to ‘have regard’ to financial stability in its objectives.

78. The Work and Pensions Select Committee also published a report on 23 June setting out the findings of their recent inquiry into ‘Defined Benefit Pensions with Liability Driven Investments’[footnote 44]. Several of the 10 recommendations set out in the report touch on regulatory remits and objectives. The main recommendations that concern TPR are:

- on the LDI event last Autumn and monitoring system risks, DWP should work with TPR and the PPF to produce, by the end of 2023, a detailed account of the impact on pension schemes of the LDI episode. TPR should also report back jointly with DWP on how they plan to monitor whether LDI resilience is being maintained and consult on whether introducing disclosure requirements on pension schemes relating to the use of LDI would help improve standards of governance. TPR should also review with the FCA whether the guidance that the FCA issued to LDI funds in April has been implemented effectively.

- on data collection and future use of LDI, the Committee recommends that TPR require trustees to report certain data on their use of LDI and develop a strategy for engaging with schemes based on the results more closely. More broadly, also that TPR set out a timeline for its commitment to become a more digitally enabled and data-led organisation, with plans to resource this transformation.

- on governance, among recommendations relating to DWP publishing the superfunds consultation response, the Committee proposes that DWP and TPR work together as a priority to improve the regulation of trustees and standards of governance.

- finally on financial stability, the Committee broadly agrees with the FPC recommendations and recommends that DWP and TPR explain how they intend to deliver on these recommendations. In view of the FPC’s recommendation for TPR to take account of financial stability, they recommend DWP and TPR should halt their existing plans for a new funding regime until this issue is resolved.

79. These developments raise important questions about TPR’s role in respect of financial stability, and its relationship to other regulators with financial stability responsibilities, notably the FPC. These include:

- responsibility for setting financial resilience measures: TPR has given effect to the FPC’s first recommendation by publishing new guidance for trustees and fund managers, including the requirement to increase capital buffers from 150 to 250 basis points[footnote 45]. Going forward, there is a question as to whether TPR should assume responsibility for designing and calibrating such measures itself, or whether it should take direction from the FPC.

- TPR’s role in accessing and analysing data for financial stability purposes: the events of autumn 2022 demonstrated that neither TPR nor any other regulator had access to real-time information on pension fund assets and liabilities. In the circumstances, the necessary information was assembled quickly on a voluntary basis by the sector (thanks in part to TPR’s strong relationships with key stakeholders). But going forward there is a question as to what data is needed to support monitoring of financial stability risks, which organisation is best placed to secure access to that data, and arrangements for sharing it with other regulators thereafter.

- TPR’s statutory footing on financial resilience matters. This includes the question of whether TPR should ‘have regard’ to financial stability in pursuing its statutory objectives, its information gathering powers, and its relationship with the FPC (for example whether the FPC can direct TPR to pursue or desist from specific regulatory measures).

80. It is for HMT and DWP together with the regulators to design robust arrangements to ensure that risks to financial stability from pension funds are visible and well-managed. Since this is a new area for TPR, it is crucial that proper consideration is given to clarity of expectations, to the skills and capabilities TPR will need to develop in order to discharge new responsibilities well, and to other operational implications (for example on TPR’s digital program).

81. I would also urge TPR to consider any new responsibilities as not being purely additive but to look for opportunities to take advantage of new capability or capacity (including in the digital space) to pursue over-arching efficiencies in its regulation of pension schemes.

Recommendation 3: TPR to work with HMT and DWP to determine how TPR should best interface with the FPC on financial stability. This to include consideration of whether TPR should have a formal objective in respect of financial stability, as well as the powers, resourcing and information needed to fulfil such a role effectively.

Role in respect of growth and productive finance

82. I note that there is a broad policy debate ongoing about economic and financial regulators’ role in respect of economic growth. For example, the Financial Services and Markets Bill proposes to introduce a secondary objective for the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) and FCA in respect of growth and international competitiveness, and the Department for Business and Trade has recently published a policy paper on regulation and growth[footnote 46].

83. In my view the most important contribution economic and financial regulators make to economic growth is by providing stable and predictable ‘rules of the game’ to support investment and other business decisions. The business department, National Audit Office (NAO) and other bodies have articulated principles of good regulation that capture this well[footnote 47]. I do not therefore see any benefit in TPR having an explicit objective in respect of economic growth.

84. Relatedly, a number of stakeholders raised the issue of “productive finance” in discussions, the suggestion being that pension fund assets are being invested in low growth asset classes (bonds rather than equities and listed rather than private equity) in part due to risk aversion and a narrow focus on cost control on the part of TPR.

85. The shift in asset allocation by DB schemes in the last decade and a half is illustrated in Figure 9:

Figure 9: DB Scheme Asset Allocation

| Year | Equities | Bonds | Other |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 61% | 28% | 11% |

| 2007 | 60% | 30% | 11% |

| 2008 | 54% | 33% | 14% |

| 2009 | 46% | 37% | 17% |

| 2010 | 42% | 40% | 18% |

| 2011 | 41% | 40% | 19% |

| 2012 | 38% | 43% | 18% |

| 2013 | 35% | 45% | 20% |

| 2014 | 35% | 44% | 21% |

| 2015 | 33% | 48% | 19% |

| 2016 | 30% | 51% | 18% |

| 2017 | 29% | 56% | 15% |

| 2018 | 27% | 59% | 14% |

| 2019 | 24% | 63% | 13% |

| 2020 | 20% | 69% | 10% |

| 2021 | 19% | 72% | 9% |

| 2022 | 19% | 72% | 9% |

Source: PPF Purple Book 2022

Note: figures may not sum to 100% of the ‘Other’ investments due to rounding

86. There is a lively debate about the causes of this shift. At least some of it reflects the maturity and closure of DB schemes, although there are also concerns that de-risking has been exacerbated by regulation – both accounting standards and TPR guidance. While DC schemes with a younger saver demographic might reasonably be expected to invest in higher growth asset classes, as Figure 9 above shows, assets under management in DC schemes are still small relative to DB. This means there has been a net shift of pension fund wealth out of UK equities. This has raised concerns about UK capital markets and companies’ access to finance. This is a complex set of issues and largely beyond the scope of this review.

87. Nonetheless in my view it is important that TPR has a clear stance on the interests of savers in this debate, and that it articulates this confidently to ensure that the interests of savers are as audible to policymakers as the interests of capital markets and corporates. There are two key aspects to this.

88. In a fiscally constrained environment, it is natural that Government looks towards private finance to help deliver a range of policy goals, for example economic growth, investment in low carbon infrastructure, or levelling up. TPR and scheme trustees have an important role protecting pension funds from political or interest group pressures and ensuring that pension funds are invested in the best interests of savers. The pursuit of policy goals can be aligned with savers’ interests, for example through tax incentives, but savers’ interests should be paramount in pension fund asset allocation.

89. As an outcomes-focussed regulator TPR should have a view on whether the pensions system is driving allocations that are in savers’ best interests. This should include whether DC savers have enough exposure to upside growth potential. The VfM framework, described above, will be an important starting point for assessing outcomes holistically (rather than looking at cost alone) and considering upside potential as well as downside risk.

90. Some trustees I spoke to felt that regulation was driving excessive risk aversion. In particular, some DB trustees felt that regulatory pressure to de-risk was causing DB schemes to close to new members earlier than they otherwise would; they felt strongly that this was not in savers’ interests. They recognised that there is a “sweet spot” in terms of scheme risk, between allowing a DB scheme to stay open with an attractive offer to new members and running the risk that the scheme makes commitments it cannot deliver. But in their opinion regulation had pushed schemes too far towards de-risking; absent this, they would have appetite to put more risk into DB schemes.

91. This evidence is anecdotal, so I cannot conclude that TPR is necessarily driving de-risking that is against savers’ interests. In any case judgements about appropriate levels of risk are necessarily subjective. Nonetheless, as an outcomes-focussed regulator I would encourage TPR to find ways to challenge itself about whether it has got this balance right.

92. In summary, I do not recommend that TPR be given a statutory objective in respect of growth, productive finance, or any other objective beyond the interest of savers. However, I do encourage TPR to develop its outcomes-focus, including if needed developing its data capabilities to allow it to monitor and assess saver outcomes (in addition to the visibility it already has over scheme processes and governance).

93. TPR should challenge itself on whether regulatory measures have the effect (regardless of intent) of driving scheme risk-appetite and asset allocations that are likely to deliver good outcomes for savers over the longer term – particularly for DC savers who stand to benefit and lose directly from investment risk. The VfM framework will be an important starting point, as will TPR’s developing focus on impact assessment (discussed in the Accountability section below). I would also encourage TPR to return to the assessment of saver outcomes in its next strategic review.

Recommendation 4: TPR to factor into the annual review of its corporate strategy its role in monitoring asset allocations and the likelihood of delivering good long-term outcomes for savers.

Scope of remit

94. At present, TPR’s regulatory remit extends to trust-based schemes, and to employers. These are the only organisations that TPR can formally direct or sanction. They can also authorise Master trusts and CDCs on a statutory basis. Several stakeholders suggested to me that there would be merit in extending TPR’s remit to cover other players in the pensions supply chain.

Pension scheme administrators

95. Pension scheme administrators are responsible for the day to day running of pension schemes, while trustees are responsible for strategic decisions. There are currently around 13 administrators covering approximately 70% of pension scheme members which TPR regulates.

96. Formally, trustees are accountable for the quality of scheme administration. Nonetheless TPR views administrators as important stakeholders, since the quality of their work has a direct bearing on saver outcomes, particularly for members of smaller schemes. I understand that a significant proportion of judgements by The Pensions Ombudsman concern administration errors. Furthermore, administrators are critical for operational resilience. Were a major administrator to suffer a serious cyber-attack or other failure, this would have severe consequences for the sector.

97. Capita is a major scheme administrator for several large pension schemes. They were recently victims of a ‘ransomware’ attack, resulting in the loss of personal customer data. DWP have advised that TPR are supporting Capita and scheme trustees, throughout the reactive process and have kept them abreast of updates which has been extremely helpful.

98. TPR’s Supervision team currently engages with three pension scheme administrators on a voluntary basis. In my view voluntary engagement by the Supervision team is an unsatisfactory half-way house, as TPR has only partial coverage and no hard powers to act if it has concerns. I understand that TPR views administrators as an important channel for oversight of the large number of smaller schemes. While consolidation may change the landscape over time, in my view TPR will need to have effective oversight of a large population of small schemes for the foreseeable future. In my view therefore DWP should assess the case for bringing administrators into formal regulation.

Professional trustees

99. As a general matter, TPR encourages schemes to appoint at least one independent or professional trustee. TPR does not mandate schemes to appoint at least one professional trustee, however where appropriate TPR does suggest schemes consider appointing a professional trustee. Where TPR has specific concerns, it can step in and appoint a professional trustee.

100. There is no regulatory definition of a professional trustee. TPR considers a professional trustee to be a person whose business includes trusteeship, who has represented themselves to one or more schemes as having expertise in trustee matters, and who is independent of the scheme in question (i.e. not a member or employed by the sponsoring employer). Professional trustees may be paid, and some are employed by professional trustee firms, which are private companies.

101. There are no hard regulatory requirements for becoming a professional trustee, although there exists a voluntary accreditation framework and a set of standards developed by a group of industry representatives with TPR input[footnote 48]. Professional trustee firms are not regulated.

102. Stakeholders put it to me that TPR should have stricter requirements for schemes to appoint professional trustees, stricter standards for what it means to be a professional trustee and maintain a register of professional trustees (with the ability to strike off unsuitable individuals).

103. I understand that, at present, there are fewer people who hold themselves out as professional trustees than there are schemes; in other words, TPR cannot currently mandate that all schemes appoint a professional trustee because there are not enough to go around. This problem should ease as the number of schemes falls with scheme consolidation. However, consolidation also means there may be limited incentive for people to qualify as professional trustees if the market is shrinking over time. In considering the case for formal requirements regarding professional trustees, therefore, DWP and TPR need to consider the desirable ‘endgame’ pension industry structure and the trajectory for getting there.

104. I understand that over the summer DWP and TPR will be doing further work on trustee capability, including on the confidence and skills to govern schemes able to invest in a wide range of assets.

Other

105. TPR currently regulates superfunds on a voluntary basis. While it remains government’s intention to introduce formal powers in this area, there have been significant delays (superfund regulation was first proposed in 2018)[footnote 49]. In the meantime, TPR has offered superfunds voluntary authorisation, which allows funds to demonstrate that they meet TPR’s standards before accepting scheme transfers. Currently only one fund (Clara) has been assessed as meeting TPR’s standards. While this interim approach is welcome in the circumstances, in the medium-term it is no substitute for a statutory framework.

106. It was suggested to me that accountants, financial advisers and payroll providers play an important role in influencing outcomes for savers, on the basis that many small businesses look to these intermediaries to recommend a pension scheme, and payroll providers in particular are well-placed to ensure compliance by small businesses with AE obligations.

107. I note also that there are many other professional advisers in the pensions supply chain. Some of these are overseen by a professional body (for example actuaries), while others are not currently regulated (for example investment consultants, though I note the proposal to bring these into regulation by the FCA)[footnote 50].

Recommendation 5: TPR to monitor evolution of the pensions supply chain in its strategy work and flag any concerns about gaps in regulatory oversight to DWP. DWP to work with TPR to understand the costs and benefits of extending TPR’s remit to cover pension administrators and introduce formal standards and authorisation for professional trustees.

Rule-making powers

108. At present, most rules governing the pensions industry are set by DWP through primary and secondary legislation. TPR has no formal ability to set rules, although in practice it can influence market-wide behaviour through its codes of practice and guidance.

109. The last review, in 2019, recommended that DWP consider giving TPR powers to make rules in specific circumstances. In particular, the review felt that giving TPR the ability to make rules in relation to information-gathering would help it become a stronger, more pro-active regulator. Unfortunately given other priorities (notably the pandemic) this recommendation was not taken forward. I therefore considered whether it is still relevant and should be picked up again.