Evaluation of the Libraries: Opportunities for Everyone innovation fund

Published 8 November 2018

1. Executive Summary

1.1 Introduction

The Libraries: Opportunities for Everyone (LOFE) innovation fund was launched in December 2016 as part of and alongside the Libraries Deliver: Ambition for Public Libraries in England 2016-21 strategy document, which set out plans to reinvigorate public library services in England.

Its primary aim was to enable local authority library services to trial innovative projects that would benefit disadvantaged people and places in England.

Specifically, the LOFE fund aimed to support projects that would:

- provide library users and communities with opportunities to remove or reduce disadvantage

- enable library services to develop innovative practice that meets the needs of people and places experiencing disadvantage

The fund was also delivered within the framework of the Society of Chief Librarians’ (now called Libraries Connected) then 5 Universal Offers, and the Libraries Deliver: Ambition’s 7 strategic outcomes.

Figure 1: Libraries Deliver: Ambition's 7 strategic outcomes

1.2 Funded projects

Managed by the Arts Council, the £3.9 million fund awarded grants of between £50,000 and £250,000 to 30 projects across 46 library services in March 2017. These were grouped into one of 5 thematic ‘clusters’ within the evaluation, bringing together projects focused on Libraries Deliver: Ambition outcome areas, aims or activities.

Arts and culture

Arts-based activities that aimed to improve young people’s confidence and skillsets, as well as their relationship with art, culture, literature and their local library.

Digital

Digital activities that aimed to improve people’s digital literacy and reduce social exclusion, embedding this within library services through staff training.

Families and wellbeing

A wide range of activities to increase families’ engagement, and to improve access to information and physical, emotional and mental wellbeing.

Literature and creative expression

Creative activities that aimed to address low levels of participation and bring literature to life for vulnerable and marginalised groups.

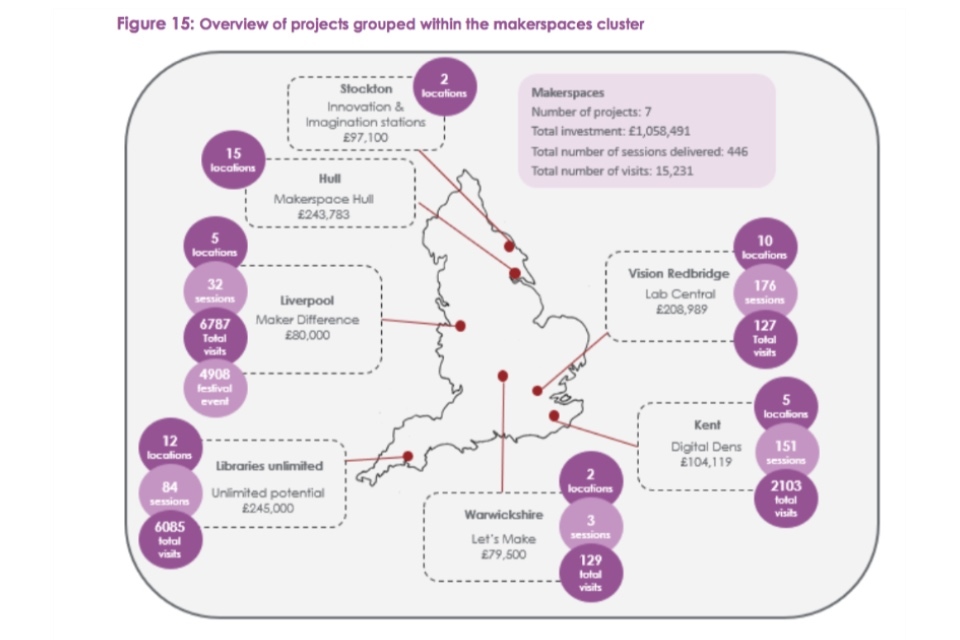

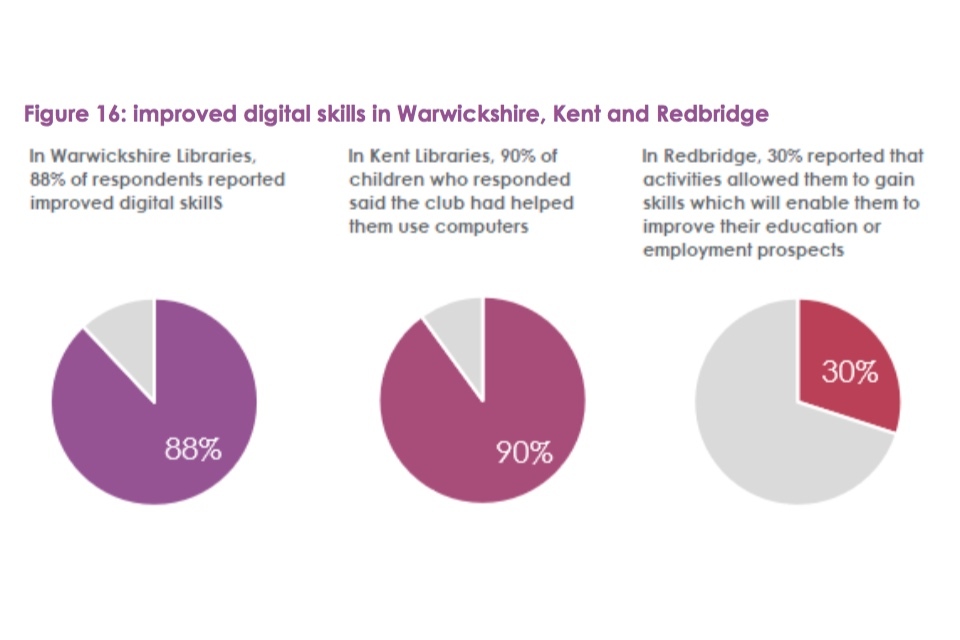

Makerspaces

Physical hubs that aimed to address local deprivation through digital taster sessions, activities and courses, including creative activities such as 3D printing, animation, robotics and coding.

1.3 Evaluation of the LOFE fund

Traverse was selected DCMS to undertake an independent evaluation of the LOFE fund in November 2017. The evaluation aimed to investigate what activities were undertaken by projects and whether these made a difference to participants, libraries and local communities. It also sought to generate learning from both the approaches taken by projects and the support that was provided by DCMS, the Arts Council and Traverse.

The evaluation applied a mixed method approach that incorporated elements of supported self-evaluation. This focused on helping projects to collect and collate their own quantitative data (how many, how much and how often) and qualitative data (what happened, what effects were felt and why).

In doing so, this report presents preliminary evidence on the extent to which expected outcomes occurred, and also provides qualitative insights into approaches to project design and delivery, as well as how to improve upon them. However, it should be noted that the variable quality of project-level evaluations limits the extent to which this evaluation can comment on impact and attribution across the whole programme.

As such, this report provides an initial evidence base that indicates both promise and potential in terms of the differences that libraries can make to the lives of service users, their staff and local communities. There is also an opportunity for this to be used by libraries to inform the conduct of more targeted, project-level evaluations in the future.

1.4 Meeting the aims of the programme

The evaluation drew together a wide body of evidence to assess the extent to which aims of the LOFE fund were met, which are summarised below.

Fund objective: library users and communities have opportunities to remove or reduce their experience of disadvantage

Achievement of objective

The available evidence suggests that the LOFE fund engaged regular, irregular and non-users of library services with opportunities to reduce their experience of disadvantage. This included:

- engaging individuals in co-design and co-production activities, which provided individuals with a sense of ownership and helped involve other people from hard-to-reach groups

- building individuals’ awareness of the opportunities that engaging with library services, digital tools and reading or arts-based activities could provide

- participation in activities then enabled library users to develop skills that could not only help them to address aspects of disadvantage but also develop the confidence to apply these skills in their everyday lives

- anecdotal evidence of early improvements in mental and general wellbeing, such as reduced social isolation, improved relationships and improved access to employment opportunities.

Fund objective: library services will have developed innovative practice that meets the needs of people and places experiencing disadvantage

Achievement of objective

The available evidence suggests that library services have used their funding to develop new tools and approaches to support people and places experiencing disadvantage. This included:

- developed spaces which provided access to a range of technological resources and workshops that had a marked impact on digitally deprived communities

- improved digital confidence and skills among library staff, which bolstered libraries’ offers and improved their position as a service provider

- improved understanding among library staff of how best to support people with special educational needs and learning disability, often through working with partners, this led to improved practices and the creation of more inclusive spaces

- transformed service offers where LOFE-funded activities were felt to have helped libraries take a significant step forward in terms of embedding digital or inclusive practices as part of their core offer

1.5 Other impacts on libraries

Many projects commented on how coming together around a clear purpose and delivering LOFE-funded activities had a transformative effect on their services. This included improvements in staff morale where staff had accessed training or taken ownership of delivering innovative activities, and extending their service reach into disadvantaged communities. It also included the transformation of library environments where new spaces had been built or innovative services embedded.

The available evidence suggests these developments also challenged and improved people’s perceptions of what their local library could offer and achieve. This was felt to have contributed to greater understanding and improved working relationships with local organisations and other council teams such as IT, public health, social services and policy departments, as well as increased service use.

1.6 Enablers

Where projects had worked well, project leads highlighted a number of common factors that were felt to underpin the development of innovative library service activities for disadvantaged people and places in England. A summary of enablers is below.

Staff

Many projects emphasised that securing the support of management, frontline and volunteer staff had been instrumental to the success of their project, especially as project teams often relied on in-kind resources to help them design and deliver activities. Several projects benefitted from electing to recruit project coordinators, reducing their reliance on overstretched library staff and enabling them to push forward with project delivery at ‘crunch moments’.

Partnerships

Working through local community organisations enabled some projects to engage and work with vulnerable and marginalised groups which had historically limited engagement with library services. Some libraries also felt that working alongside these groups helped raise the profile and change perceptions of libraries in these communities.

Engaging participants

Engaging target groups in consultation or co-production activities, often with the support of local organisations, helped projects to better understand the needs of and challenges faced by their target groups. When working with vulnerable and marginalised groups, projects also emphasised the importance of tailored approaches to engagement and project activities.

Programme management

Robust programme management approaches such as working with a multi-disciplinary steering group and undertaking monitoring and evaluation from the start of projects were felt to have helped shape effective project design.

Some libraries also reported that their LOFE grant had enabled them to attract and secure additional funding from local authorities and new partners over and above the 10% match funding required within applications. This additional funding tended to be directed towards the renovation of rooms to house LOFE-funded spaces, or towards the addition of further features within existing spaces, rather than towards increasing the scale of activities.

1.7 Challenges

Funded projects identified a wide range of challenges that they had faced in developing activities for disadvantaged people and places in England. Suggested solutions to these challenges can be found in the challenges and solutions section. A summary of challenges is below.

Staffing

Many projects struggled to engage overstretched staff. Where projects were perceived as additional work this sometimes resulted in a reluctance to engage while, even among enthusiastic staff, limited capacity sometimes made it difficult to attend training or commit sufficient time to projects.

Projects often worked alongside volunteers to help address this demand, though recruitment processes often took longer than expected due to high demand for them among services and volunteers were occasionally unreliable in their commitment.

Engaging and working with participants

Some projects found it challenging to both engage and work alongside vulnerable and marginalised groups – including managing behaviours that may challenge, and unreliable attendance. Other projects also struggled to communicate new types of activities to their target groups.

Working with partners

Some projects developed new partnerships with organisations that later turned out to be unreliable, while, despite good will, other partners’ contributions were also limited by competing demands. Several projects that engaged organisations from different sectors also reported a clash of working styles.

Project delivery

Projects also faced a wide range of delivery challenges, including procurement delays when purchasing IT equipment, health and safety obstacles when building spaces and internal issues with IT infrastructure.

1.8 Lessons learned

Projects reflected on their participation in the grant programme and identified a number of learning points:

Small grants can make a big difference to services

The open brief behind the LOFE funding enabled projects to deliver innovative activities without fear of failure. Across all projects, funding was felt to have made the most difference through providing projects with the opportunity to invest in high-value equipment and resources, support their staff with training, and market their full-service provision to local communities.

Funders should provide clear communication and flexible support

Clear grant aims and criteria supported applicants during a compressed grant application window. The Arts Council’s flexible approach to project plan adjustments was also felt to have enabled projects to better respond to emerging needs and challenges.

Grant recipients value opportunities to share ideas, challenges and lessons learned

‘Learn and share’ events provided project staff with opportunities to network, share transferable learning and seek reassurance from others – outcomes that can also be supported via online forums.

Embed evaluation activities in grant awards

Undertaking programme-wide evaluation activities at the start of the grant programme would have better supported project development processes, enabled projects to ensure that adequate resource was allocated to evaluation activities, and reduced the risk of duplicating local evaluations.

1.9 Recommendations

The following recommendations have emerged from the delivery and evaluation of the Libraries: Opportunities for Everyone innovation fund (LOFE).

Focusing library activities on specific audiences and outcomes

Awarding funding in a way that focuses library activities on specific audiences and outcomes helps to galvanise staff and partners to keep momentum on projects, even as circumstances change.

Through the LOFE fund, libraries channelled their energy into addressing particular areas of need and engaging specific groups in ways that time and resources may not usually allow. Project leads developed new and innovative ways to reach some of those target audiences, often supported by expert advice and local stakeholder groups. These approaches will enable libraries to continue to build those audiences and strengthen their impact and social value into the future.

Building in evaluation from the start of a project

This focus on outcomes links to the value of building in evaluation from the start of a project. This not only improves data collection and evidence but helps libraries to strengthen and reflect on their aims (e.g. through the theory of change process) before plotting a particular course.

Some projects in the LOFE fund reported that creating a theory of change, with support, at the beginning of their project lifespan would have led them to approach some activities differently. It would also have focused their efforts in different ways to reach their intended outcomes.

Value of giving libraries flexibility around the use of funding

However, funders do not need to be prescriptive in how those outcomes are achieved. The LOFE fund demonstrated the value of giving libraries flexibility around the use of funding. In some cases, staff have already have the ideas, the confidence, the skills and the networks to deliver something fantastic, and a (potentially modest) amount of funding is all they need to make it happen.

For services which used the funding to invest in new equipment or entirely new spaces, this is changing what those libraries are and how they engage audiences into the future.

In other cases, a more important investment will be in library staff (and potentially volunteers) where they need support to develop the skills and confidence to work with a new product or project and bring it to life. Without this, the best projects might never gain traction. It is important for funders and project leads to understand that context and invest resources where they are needed, such as including staff training in grant criteria and funding bids.

Encourage (or require) libraries to reach out to local partners in order to deliver a programme

Where funders encourage (or require) libraries to reach out to local partners in order to deliver a programme it can help those services forge strong, long-term bonds with organisations in their community.

These partnerships can enable libraries to raise their game in terms of accessibility and engagement of diverse audiences, raise their profile with other services and community groups, and improve their reputation with more innovative, dynamic partners who may not have looked to libraries as potential partners in the past.

At its most positive, this can result in the renewal of libraries as a partner and a focal point in a local ‘system’ and a local community.

Using programmes like this as a vehicle for building networks and learning across the sector

There are clear opportunities for using programmes like this as a vehicle for building networks and learning across the sector. Funders who are visible, active and engaged by hosting regional and thematic workshop events can also maximise their impact through the production of thoughtful agendas, activities and resources to underpin learning.

2. Introduction

2.1 The LOFE fund

The Libraries: Opportunities for Everyone innovation fund (LOFE) was launched in December 2016 as part of and alongside the Libraries Deliver: Ambition for Public Libraries in England 2016-21 strategy document, which set out plans to reinvigorate public library services in England. The fund was established by DCMS to enable local authority library services[footnote 1] to trial innovative projects that would benefit disadvantaged people and places in England[footnote 2]. Specifically, the aims of the fund were to:

- provide library users and communities with opportunities to remove or reduce their experience of disadvantage

- enable library services to develop innovative practice that meets the needs of people and places experiencing disadvantage

Managed by the Arts Council, the £3.9 million fund awarded grants to 30 projects across 46 library services in March 2017. Lead applicants were required to be local authority library services or to have been commissioned to deliver the whole library service on behalf of local authorities.

Each of these projects also delivered within the Society of Chief Librarians’ (now called Libraries Connected) then 5 Universal Offers and the Libraries Deliver: Ambition’s 7 strategic outcomes. The latter are shown below and referenced as icons throughout the report where project impacts were considered to have contributed towards them.

Figure 2: Libraries Deliver: Ambition's 7 strategic outcomes

Successful applicants were awarded grants of a value between £50,000 and £250,000 for the period April 2017 – March 2018, which was added to a required minimum of 10% match funding in either cash and/or in-kind support. Some projects also supplemented their award with funds from wider local authority resources.

A list of projects and their grant awards can be found in the Annex A of this report.

2.2 Evaluation of the LOFE fund

Methodology

Traverse, formerly known as OPM Group, was selected by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) to undertake an independent evaluation of the LOFE fund in November 2017.

The aims of the evaluation were to:

- provide an overview of activities undertaken by individual projects, highlighting major themes

- provide an understanding of the difference that these activities made to participants, libraries and local communities (project impacts)

- draw out the main learning from the approaches taken by projects, including which activities were felt to be successful and why, as well as what challenges were encountered and how these were overcome

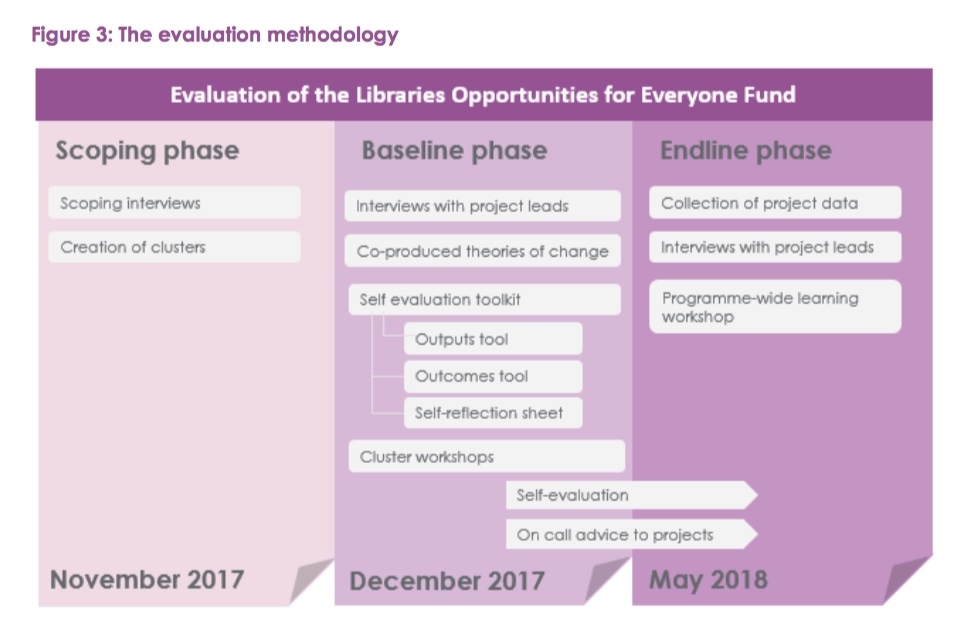

The evaluation of the LOFE fund applied a mixed method approach that incorporated elements of supported self-evaluation (Figure 3).

This focused on helping projects to collect and collate their own quantitative data (how many, how much and how often) and qualitative data (what happened, what effects were felt and why).

Figure 3: the evaluation methodology

The main evaluation activities included:

- the development of 5 thematic ‘clusters’ and accompanying theories of change, which grouped projects by common aims and activities

- the provision of a mixed method self-evaluation toolkit, which included tools to help projects capture their outputs (what they produced), outcomes (what changed as a result) and lessons learned during delivery

- the provision of evaluation support to projects to help projects plan or refine their data collection activities

- peer learning opportunities that enabled projects to share progress, challenges and potential solutions

- baseline and endline interviews with library authority staff to explore their expectations, perceptions of which project elements were successful, challenges encountered and how these were overcome, and lessons learned for the future

A detailed explanation of the methodology is presented in Annex B of this report.

Caveats to the findings

Overall, the level of engagement from project leads was high across all evaluation activities, including the return of the self-evaluation toolkit components.

However, the quality of data within these returns varied significantly between projects. While some projects commissioned external evaluations (and then went to great lengths to transport this data into the Traverse tools), others undertook their own monitoring and evaluation activities, with data gathered in different ways. For some of these projects, the Traverse evaluation was also commissioned at too late a stage to inform their data collection processes.

When considering the findings presented in this report, it is also important to note the following:

- the impacts of the grants have been self-reported by project leads and cannot be verified by Traverse

- some projects were still in the middle of their delivery timeline at the point of publication, so the impact of their initiatives has not been fully captured

2.3 Structure of this report

This report presents impacts and learning from across projects in the following sections:

- findings from funded projects

- enablers

- challenges and solutions

- recommended project delivery approaches

- lessons learned for grant programme delivery

- conclusions

The report has 3 primary audiences:

- central government

- local government

- people working in libraries

It includes transferable learning on what works well (enablers section) and potential challenges that should be mitigated when undertaking new activities in library services (challenges and solutions), as well as recommended approaches towards working towards specific outcomes that feed into Libraries Deliver’s strategic outcomes (lessons learned section).

This report is supplemented by a separate projects information booklet, which provides further information about the aims, activities and impacts of each funded project, as well as contact details.

3. Findings from funded projects

This section provides an overview of projects’ target audiences, activities, emerging impacts, and perceived sustainability.

3.1 Overview of clusters

Funded projects were grouped into one of 5 thematic ‘clusters’ within the evaluation, which brought together projects focused on Libraries Deliver: Ambition outcome areas, aims or activities[footnote 3].

Table 1: Overview of programme clusters

| Clusters | Libraries |

| Cluster 1: Arts and culture - arts-based activities that aimed to improve young people’s confidence and skillsets, as well as their relationship with art, culture, literature and their local library | Merton, Middlesbrough, Lewisham |

| Cluster 2: Digital - digital activities that aimed to improve people’s digital literacy and reduce social exclusion, embedding this within library services through staff training | Barnsley, Hampshire, Lincolnshire, Manchester, Nottingham, Sandwell, Telford & Wrekin, West Sussex |

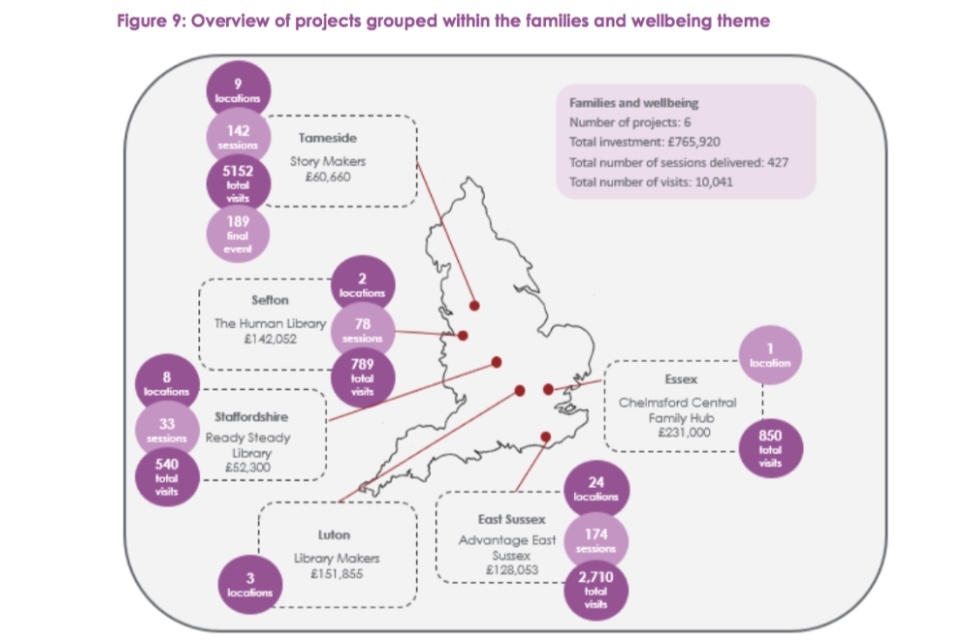

| Cluster 3: Families and wellbeing - a wide range of activities to increase families’ engagement, and improve access to information and physical, emotional and mental wellbeing | Essex, East Sussex, Luton, Sefton, Staffordshire, Tameside |

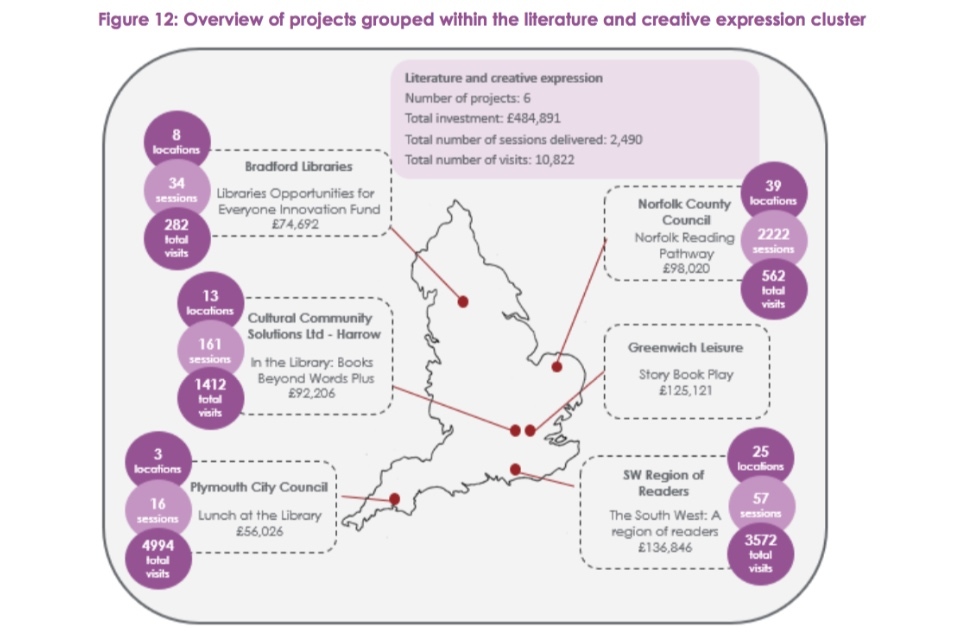

| Cluster 4: Literature and creative expression - Creative activities that aimed to address low levels of participation and bring literature to life for vulnerable and marginalised groups | Bournemouth Borough Council (SW Region of Readers), Bradford Libraries, Cultural Community Solutions Ltd – Harrow, Greenwich Leisure, Norfolk County Council, Plymouth City Council |

| Cluster 5: Makerspaces - Physical hubs that aimed to address local deprivation through digital taster sessions, activities and courses, including creative activities such as 3D printing, animation, robotics and coding | Hull, Kent, Libraries Unlimited – Devon, Liverpool, Stockton, Vision Redbridge, Warwickshire |

Funded projects responded to a wide range of local needs and priorities within different parts of England, delivering tailored activities to their identified target groups. For this reason, this section first explores the following at a cluster level:

- local needs - what projects set out to address

- target groups - who funded projects engaged and how

- activities - what innovative activities were undertaken by funded projects

- impacts on individuals - What changes were measured or observed in participants

It then explores the following at a programme-wide level, which were more common across the 5 clusters:

- impacts on libraries and local communities - what changes were measured or observed within library services and local communities

- legacy impacts and sustainability - which impacts were anticipated to last beyond the LOFE funding period, and how funded projects planned to support them

Insights have been brought together from a range of sources, including:

- self-evaluation monitoring data and self-reflection questionnaires submitted by project

- baseline and endline telephone interviews with project leads

- programme-wide evaluation workshops

These have then been structured in line with the 5 co-produced theories of change.

This section looks at the emerging outcomes of funded projects on individuals, library services, and their communities as a whole.

Measuring these impacts within a 6-month timeframe is challenging, made even more difficult in the case of projects where anticipated outcomes are expected to emerge over far longer periods of time.

Projects were therefore encouraged and supported to monitor and evaluate their activities against the short-to-medium term outcomes within the 5 developed theories of change, which could then demonstrate attribution towards longer-term impacts. Methods of data collection commonly returned by projects included: registration and booking forms; post-event feedback forms; surveys with project participants, staff and partners; and observation.

Some projects also commissioned external evaluations to assess the difference that they had made to participants and communities. Where available, these findings have also been incorporated within this section.

3.2 Impacts on individuals

Cluster 1: Arts and culture

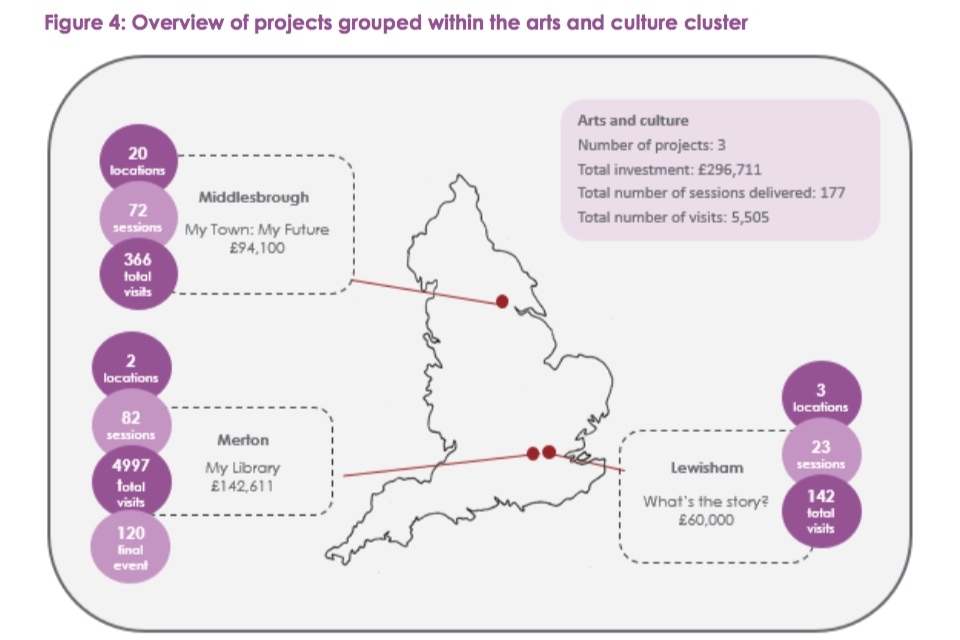

Three LOFE-funded projects focused on activities relating to arts and culture (Figure 4)[footnote 4].

Figure 4: overview of projects grouped within the arts and culture cluster

Projects within this cluster:

- mostly aimed to improve the confidence and skills of young people with lower life chances, as well as improve their relationship with literature, arts and culture and their local libraries

- were all targeted at specific audiences where library membership and regular library usage tended to be low -this included individuals who displayed behaviours that may challenge or those with learning difficulties.

- 2 of 3 were aimed to improve civic engagement through the creative exploration of local history - it was also hoped that participants’ work would create a lasting resource that will enhance local knowledge and provide a sense of pride in local communities

- generally included exhibitions or performances that showcased participant work, which in some instances meant developing an exhibition space

The text below provides an overview of the projects’ local priorities, target groups and approaches to engagement, and a brief overview of the activities undertaken. Where projects are hyperlinked, this links to posts written by projects that have been published on the Taskforce blog.

Lewisham

What local issues did the funded project address?

- Goldsmiths has 10 full fee-waived places a year for undergraduates from underprivileged local areas, but currently struggle to fill these

- Lewisham is in the 8 poorest London boroughs across all measures of poverty (London poverty profile, 2015)

- 1 in 4 of Lewisham residents are aged under 19, where disadvantage is highest

- Lewisham is among the 4 lowest-ranked boroughs for numbers of people on out-of-work benefits, for GCSE attainment and for 19-year olds lacking Level 3 qualifications (2 or more A-levels)

Who were the target groups and how were they engaged?

- recruited young people through the council website and other community links

- held 3 information sessions in various venues

- worked closely with Goldsmiths University

- engaged a member of the Lewisham Young Citizens’ Panel (a body of civically engaged local 11 to 18-year olds) as part of the steering groups

- used connections with local secondary schools

- shared project information through a local job fair, social media sites including Twitter as well as distributing leaflets in Lewisham Library

What were the main activities?

- supported young people aged 16 to 21 to take part in a multi-media journalism project which would enhance skills, prospects and provide an introduction to further education

- sourcing, interpreting and editing stories about their local community

- learning how to use a video camera, interview techniques, field work, and how to edit a Wikipedia page

- the course used the Battle of Lewisham as a central focus to develop a deeper relationship with and understanding of the local area

Merton

What local issues did the funded project address?

- decline in library usage in the borough from primary school to secondary school

- 45% of Merton school pupils are living in an area of deprivation (IDACI) - these pupils are half as likely to achieve 5 good GCSE results compared to their peers (White Paper, The importance of teaching, 2010)

- aimed to increase young people’s engagement with reading, libraries and the art in localities with reduced life chances

Who were the target groups and how were they engaged?

- outreach and consultation with young people

- engagement with potential participants through cultural partners

- developed and shared the ‘art space’ brand through a website and on social media

- engagement with secondary school teachers

What were the main activities?

- hired a youth engagement manager

- delivered a series of workshops that met young people’s interests, including art, drama and poetry

- culminated in an exhibition and performances designed by participants with professional support

- created a high school reading scheme to encourage library sign ups

- created dedicated arts spaces within Mitcham and Wimbledon libraries including an exhibition space for the ‘My library’ art competition

Middlesbrough

What local issues did the funded project address?

- focused on wards in the top 20% most deprived in the country, with many featuring in the top 5%

- aims to highlight past and present contributions made by marginalised groups to the local area

- only targeted wards in the top 20% most deprived in the country for deprivation (Index of Multiple Deprivation 2015)

Who were the target groups and how were they engaged?

- libraries have restructured to form community hubs

- the project has focused on areas where there are community hubs with libraries and they have delivered activities in at least 5 different hubs

- worked with some schools to recruit participants

- promotion via council website and Ageing Better Middlesbrough

- word-of-mouth by participants

What were the main activities?

- digitisation of centrally-held resources (such as photos) by the library service using new scanners

- creating new photographs of landmarks in the area in contrast to the old archive images

- creative writing workshops and creation of a digital platform for hosting their outputs

- displaying images on a digital platform as well as in a touring exhibition

Some projects within other clusters also had elements which related to the arts and culture theme. Where relevant, these projects are included in the commentary below:

Table 2: Other projects of relevance to the arts and culture cluster

| Project name | Main cluster | Arts and culture crossover |

| Vision Redbridge | Makerspaces | Aimed to give young people in more deprived areas access to technology. Produced a public art commission, which relied on working with secondary schools producing digital art through workshops and gallery visits. |

| Devon | Makerspaces | Aimed to promote literacy, digital literacy, as well as health, wellbeing and employment prospects amongst targeted communities. Delivered a variety of activities and workshops to encourage creativity, literacy and engagement with the library, including over 40 outreach events. |

Impacts on individuals

Projects within the arts and culture cluster varied greatly, but all have reported a wide range of outcomes from LOFE-funded activities for project participants. These are outlined below.

Enhanced skills and prospects for individuals

Across all arts and culture projects, sessions focused on enhancing participant skills.

Improved digital and creative skills

In Lewisham and Middlesbrough, activities were partly focused on enhancing participants’ digital skills, and ensuring that these skills can be meaningfully applied to creative and professional endeavours. This involved giving participants from less advantaged backgrounds access to digital tools that they otherwise would not get to use.

There is some anecdotal evidence to suggest that participants will go on to apply these newly acquired skills in the future. For example, in Lewisham, 1 of the 12 course participants continued to use software for a personal project inspired by the course.

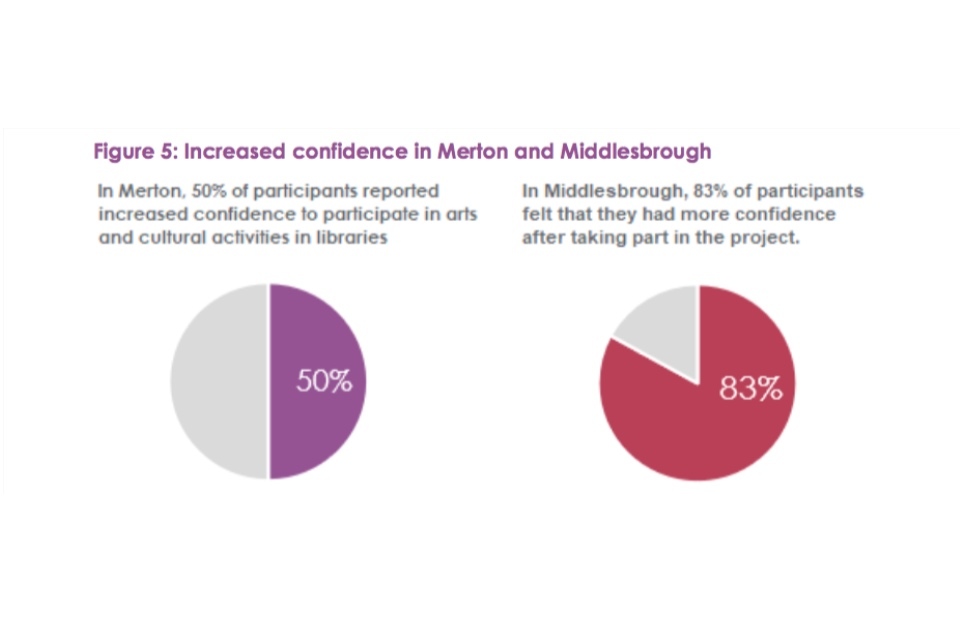

In Middlesbrough, 33% of course participants felt that they were more digitally confident following the course, although 83% neither agreed nor disagreed that they would use skills learned in other aspects of their life. This may be because the photography and digital scanning software was very specific and perhaps less easily applied to alternative contexts.

Improved access to jobs and further education

In Lewisham, many participants were not in education at the time the course started and had no experience of a university setting. The workshops took place at Goldsmiths University and gave participants a taste of what studying journalism in a formal environment might be like. Participants were able to complete the course with a tangible piece of work showcasing their newly acquired journalism skills, including sourcing, shooting and editing content. Following the course, one participant applied to a formal journalism course.

In Middlesbrough, 50% of participants reported that they felt they had gained valuable skills from the workshops that would help them gain employment. Having said this, the impacts of the digitisation part of the project were more limited, as most volunteers who took part were already retired and therefore did not plan to use newly acquired skills for future employment.

In Merton, 67% of participants reported that they had increased skills as a result of taking part in the project, while project leads at Vision Redbridge felt that engagement with the project has raised the aspirations of the young participants.

Increased engagement with arts and culture

For most of the projects, participants said that taking part in project activities had led them to join or consider joining more arts or library-based activities. In Middlesbrough 85% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that as a result of the project, they had engaged more with public libraries and 67% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed they had engaged more with creative arts.

This was reflected in Merton where 80% of facilitators surveyed felt that the workshops had improved young people’s engagement with arts and libraries.

“Some of the marginalised groups that we have worked with before… had never worked in arts before. It gave them a whole strand of ideas of activities that they can be involved in with this group.” Project Lead

“Having a theatrical performance in the library is so fab. It gives children a chance to experience a live theatrical performance.” Project participant, Devon

Improved wellbeing

All of the projects within this cluster reported perceived improvements in participants’ wellbeing, mostly through the development and showcasing of new or enhanced skills.

Showcasing skills

In Redbridge, Middlesbrough, Lewisham and Merton, activities included a showcase of participants’ skills, where workshops culminated in an exhibition or performance. In Redbridge, for example, this gave participants the opportunity to have their work seen by over 14,000 people. In Merton, the ‘art spaces’ were created with exhibiting in mind. In Lewisham, the course was designed to help participants create a portfolio for job and university interviews.

Increased confidence

Participants across all of the projects in this cluster self-reported perceived increases in their confidence levels, including day-to-day confidence and their confidence to join other arts and culture activities.

Figure 5: increased confidence in Merton and Middlesbrough

Reduced social isolation

The development of confidence and skills has, in some cases, potentially had an impact on participants’ social interactions. In Lewisham, project leads reported that the project helped participants meet like-minded people and build connections through working together. In Merton, the project lead reported that engaging in creative activities has made the participants - often young people who had reported feeling ostracised - feel part of a community.

Cluster 2: Digital

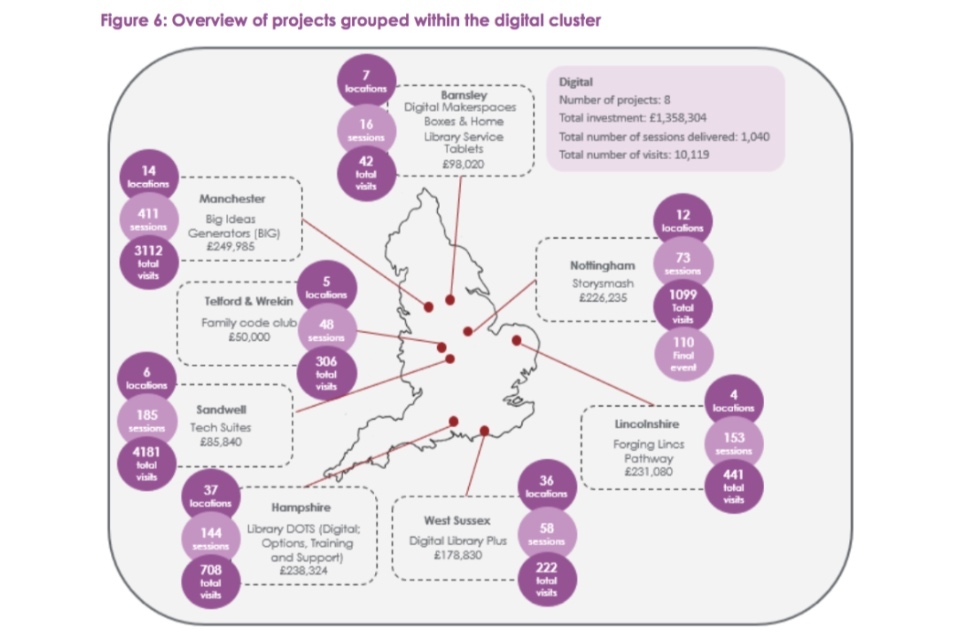

A total of 8 LOFE-funded projects focused on reducing digital exclusion through introducing and training participants in how to use digital tools (Figure 6). Projects in the ‘Makerspaces’ cluster developed similar activities, but are reported separately.

Figure 6: overview of projects grouped within the digital cluster

Projects within this cluster:

- aimed to improve digital literacy and reduce social exclusion through the use of digital tools

- worked across a wide range of target groups, from children and young people to families, older people, jobseekers and isolated ethnic groups

- ran a wide range of activities, from iPad lending schemes to creative workshops on photography

- staff training was an important activity, with a view to making digital assistance normalised within library services

The text below provides an overview of the projects’ local priorities, target groups and approaches to engagement, and a brief overview of the activities undertaken. Where projects are hyperlinked), this links to posts written by projects that have been published on the Taskforce blog.

Barnsley

What local issues did the funded project address?

- widespread social isolation and digital exclusion

- opportunity to act on corporate outcomes

Who were the target groups and how were they engaged?

- focus on particularly hard-to-reach-groups such as the elderly and the housebound

- digitally excluded community groups who cannot afford digital equipment or do not have the knowledge to use it

What were the main activities?

- developed digital kits involving camcorders, tablets, laptops, Raspberry Pi sets and micro:bits

- one-to-one sessions with target groups without a pre-set list of activities, using the digital kits

- ran or facilitated group sessions with community groups and other local partners

East Sussex

What local issues did the funded project address?

- high unemployment and poverty

- low levels of digital literacy

- who were the target groups and how were they engaged?

Who were the target groups and how were they engaged?

- The project had 6 different strands targeted towards people with specific needs, 2 of which involved digital activities with jobseekers and children aged 8 to 12-years old

What were the main activities?

- code clubs with 40 children aged 8 to 12, run by 12 volunteers

- IT for you - sessions with jobseekers

Hampshire

What local issues did the funded project address?

- reducing digital exclusion and social isolation

Who were the target groups and how were they engaged?

- targeted various groups to capture a wide audience (lone parents, Nepalese community, people with low literacy across the region)

What were the main activities?

- initial 3-hour training session (crash course)

- iPad lending schemes over a 4-week period

- contact with tutor and coordinator over the course of 4 weeks (pointing people to look at e-books, e-magazines, health and wellbeing, money management)

Lincolnshire

What local issues did the funded project address?

- coastal deprivation, predominantly rural areas leading to social isolation and digital deprivation

- high unemployment rates

Who were the target groups and how were they engaged?

- 16 to 25-year olds

- opened up target group over the course of the project to anyone who was interested

What were the main activities?

- created Tech Labs in 4 libraries and mobile IT kits to serve 9 other libraries

- 153 workshops and tutored courses in a range of digital and creative suites (e.g. graphic design, music production, photography, coding, computer game writing)

Greater Manchester[footnote 5]

What local issues did the funded project address?

- need for new businesses to extend reach across Greater Manchester

- help with innovation and entrepreneurship

- ensure that libraries contribute to meeting business information needs

Who were the target groups and how were they engaged?

- a broad range of participants interested in developing a new skill or business idea

- worked with partners to reach out to desired target groups

What were the main activities?

- over 400 group workshops on 3D printing, cloud computing, business idea guidance, online tools, social media

- one-to-one sessions at the Business and Intellectual Property Centre

- smart TV and stand purchased for workshop presentations and streaming events

Nottingham

What local issues did the funded project address?

- low library engagement with young people above the age of 11

- tackling area’s literary deficit

- focusing on 5 geographical areas that are hard to reach

Who were the target groups and how were they engaged?

- the target group were young people aged 11 to 25

- recruited through academies, intense promotional activity and outreach

What were the main activities?

- created gaming hubs in 5 libraries, teaching people to create games using specific software (Twine)

- photography, music editing, coding, creative writing courses

- author-led writing workshops

- developed youth council for library service to develop the direction of the project

Sandwell

What local issues did the funded project address?

- an inner-city area to the west of Birmingham with low income, high levels of deprivation and low ownership of many technologies

- council is delivering more services online as part of a channel shift agenda

Who were the target groups and how were they engaged?

- 2 focused target groups with specific activities for each:

- Children and families

- Older people: iPads for beginners

What were the main activities?

- virtual reality sets and robotics (for children and families)

- tablet loan (iPads) and classes

- classes on using council web portal

- staff training

Telford and Wrekin

What local issues did the funded project address?

- tackling unemployment and skill shortages

- 4 libraries that serve the most deprived areas of Telford

Who were the target groups and how were they engaged?

- initial focus on parents and young children, but later broadened to those outside target group who were interested in joining the sessions

- reached out via social media, by using existing connections and partners (e.g. Town and Parish councils).

- audience development sessions

What were the main activities?

- family code clubs aimed at getting parents to learn coding skills to help them have a better chance of getting jobs

- sessions using a 3D printer.

- staff training

West Sussex

What local issues did the funded project address?

- a large, predominantly rural county with just under half the population living in rural areas, and a fifth of those living in the smallest, most remote communities

- individuals experience increased hardship through rural isolation

Who were the target groups and how were they engaged?

- 3 digitally excluded target groups: isolated older people (who find it hard to get digital assistance); job seekers with low digital skills; and people with learning difficulties

- engaged through signposting new services to existing customers; referrals from partners working with target groups; job fairs; and proactive relationship development with relevant organisations (e.g. hospitals)

What were the main activities?

- delivered across whole county via 36 libraries, including sessions in homes, children’s centres and job centres

- home library sessions – providing assistance to older people to use technology if they have it or encourage to borrow iPads. Coaching visits and referral routes in place

- bespoke workshops with jobseekers on CV building and job search, online software, as well as free one-to-one tuition on public network computers

- storytime sessions using Matrix Maker software (speech therapy devices)

Impacts on individuals

Projects within the digital cluster reported a wide range of outcomes from LOFE-funded activities at individual, library and community levels.

Increased digital literacy

One of the main driving forces behind the projects within the digital cluster has been the desire to increase digital literacy among selected target groups. Libraries attempted to capture this change through a variety of methods, from conducting pre- and post-activity surveys, to collecting participant stories and developing case studies based on participant or staff feedback. Impacts related to increased digital literacy have emerged in the following ways:

Increased awareness of and access to digital tools and information

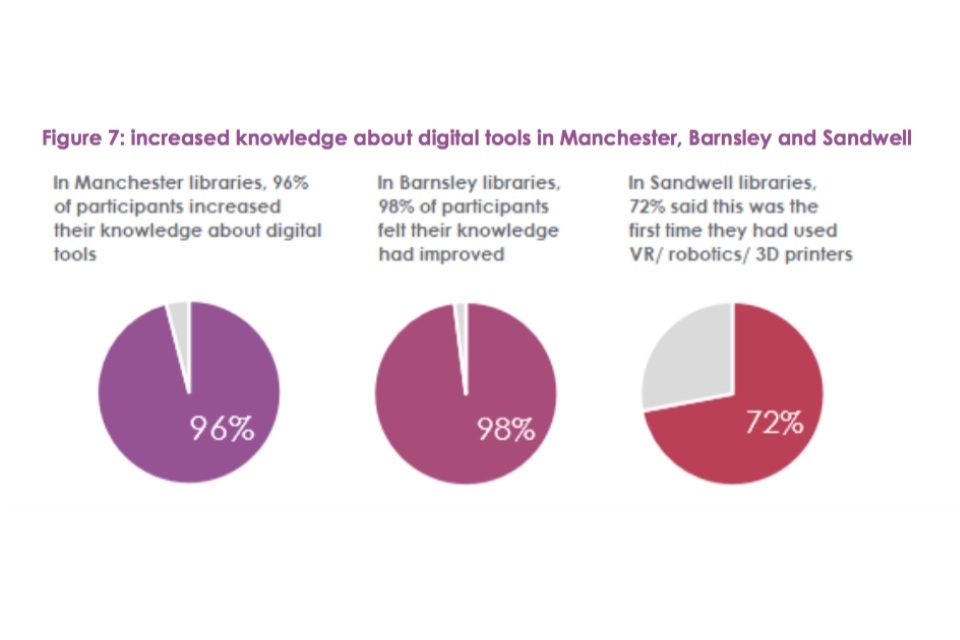

Taking participants on a journey of digital awareness was often reported as one of the biggest successes by project leads. The technology that was made available to service users through the LOFE fund was often new to them, as shown in a selection of survey results below:

Figure 7: increased knowledge about digital tools in Manchester, Barnsley and Sandwell

In some instances, access to new digital tools had the potential to have an immediate impact on participants’ quality of life. West Sussex libraries worked with participants with learning disabilities, for instance, for whom free-to-access technology such as Matrix Maker opened up new possibilities:

Case study: increased access to digital tools

Michael has a degenerative condition. To help him communicate, he had a laminated book with sheets that his parents had created for him. His carer was keen to help Michael communicate more and told his mother about the wide range of digital technology that could assist him. However, his mother was not convinced whether it would work and was not sure if she should spend money on it. West Sussex libraries lent Michael an iPad pre-loaded with the Matrix Maker app, containing hundreds of pictures and templates that can be used to create pictures and communication tools.

“This helps customers see what works for them and it has a real impact on the quality of their lives.”

West Sussex Project Lead

Improved digital and creative skills

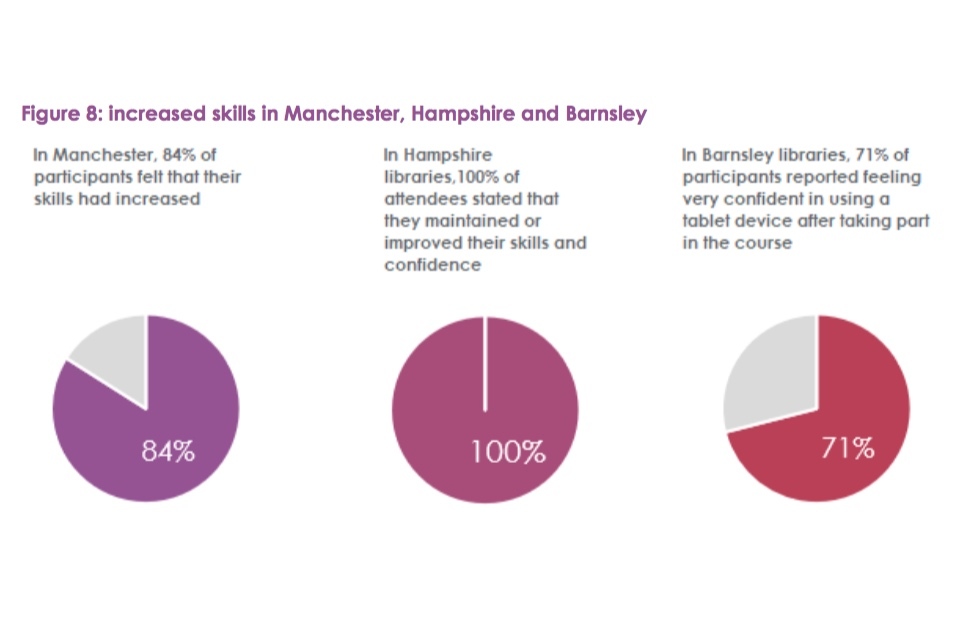

As result of actively engaging in the sessions, participants have not just gained awareness of what opportunities digital technologies can bring to their lives but have also picked up skills in how to use them, whether for socialising, job-seeking or other purposes.

Figure 8: increased skills in Manchester, Hampshire and Barnsley

Other libraries did not administer self-assessment questionnaires, but reported similar impacts through tutor observations during sessions.

“Their knowledge is the biggest impact. A lot of them came to us with no knowledge at all in the thing that they wanted to study. They had an interest in the subject but no formal training in those areas. Definitely that was the biggest draw – that they could learn for free and take that knowledge away and use that to help them find a job.” Project Lead

In some cases, by engaging with certain types of digital technology participants were required to draw on other skills, too. For example, in order to create more advanced Twine games, the young people who took part in Nottingham’s Storysmash utilised and developed supporting skills in art, design, photography and music, as well as coding. Project leads reported that some of those young people started to become self-sufficient in teaching themselves certain subjects in order to develop their own games. Participants attending events in Hampshire and Lincolnshire libraries also took courses in a range of creative skills such as graphic design, product design and photography.

Increased confidence in the digital world

Evidence suggests that the projects may have had an impact on participants’ confidence in using digital technology, particularly among some older participants who felt daunted at the thought of using digital technology.

Libraries adapted their approach to activities in order to address prevalent feelings of fear and uncertainty around what digital technology is and what it enables. This often required a one-to-one approach, which limited the number of people that libraries were able to approach during the funding period. However, project leads often felt that the personalised route led to more tangible impacts on individuals’ lives.

“One of the biggest impacts has been the ability to improve their digital confidence. We are just embarking on this so there is not a huge number of people, but we left all of them in much better place in terms of confidence and ability. It’s small scale improvement, but what we try to do is listen to the person and figure out what they are interested in and how they need help.” Project Lead

More frequent use of digital tools

Whether as a result of being more aware of digital technology or confident using it, participants across projects reported an increased frequency of using a variety of digital tools.

Project leads in Hampshire reported early evidence and stories from participants who had started using NHS weblinks to book and attend appointments as well as find local dental provision. In East Sussex, customers were also reported to use their newly-acquired digital skills to seek employment and manage aspects of their lives online. In Barnsley’s libraries, a final survey of home library service customers has shown that several more people are now interested in having access to digital devices, setting a good foundation for future growth.

Increased employability

Some projects such as East Sussex, Manchester, Telford & Wrekin and Lincolnshire targeted jobseekers. While evidence of people getting jobs at this stage is very limited, libraries attempted to capture outcomes within this space by asking participants to report on the perceived impact on their skills and prospects.

In Manchester, for instance, several participants reported a desire to pursue their own business ideas. In Lincolnshire libraries, over the course of the project the number of participants who thought that improving their employment possibilities was an important reason for taking part in the project increased from 30% to 50%. Lincolnshire Libraries provided a couple of anecdotal examples of early impact. Project leads reported anecdotal evidence of one participant finding a work experience placement with one of the library tutors and another participant finding work as a result of the portfolio that she built during the project.

“Even if we don’t manage to get the unemployed parents into work, I hope that the cycle can be broken because the young people now have the knowledge.” Project Lead

Reduced social isolation and exclusion

Reducing social isolation and (digital) exclusion was an important thread throughout the objectives of projects within the digital cluster. Several sources of evidence across all projects indicate that this was achieved, including both participant testimonies and library staff observations. Many libraries took a proactive approach in reaching those who were isolated, taking digital tools to them and showing them how this can impact on their lives. This is very well-evidenced in the case study presented below. It refers to participants from West Sussex library, but many similar examples were also reported elsewhere.

Case study: reducing social isolation

Shelley is an 82-year-old Home Library Direct customer. She owned an iPad but had very little idea how to use it. During the first visit, it quickly became apparent how isolated Shelley was. After losing her husband and her mobility, she had become largely housebound. Her only regular visitors were the library volunteer who delivered her books and her friend who helped her with her garden.

The first thing that Shelley was keen to learn was email, so that she could keep in touch with friends from London and also register for other online services. Thanks to her working life as a PA her keyboard skills were very good, and she picked it up quickly. She was also interested in BBC iPlayer and once she registered, she couldn’t believe that she was suddenly able to use her iPad to watch Blue Planet.

On her second visit, Shelley reported using her iPad every day. She said that the iPlayer had helped her insomnia and that she had even watched a film in bed. During the visit, she learned how to use other digital apps and resources. Shelley spoke of the importance of those extra activities to fill her day because she was quite lonely and isolated.

It was evident to the Home Library Direct volunteers how much the iPad could improve her quality of life and how much the entire experience of the visit built her confidence. Her subsequent feedback form and emails support this:

“I am using my iPad every day now (I’m beginning to show off…) - it’s not shut in a drawer any more. It’s magic!”

Even for participants who were not necessarily isolated or excluded, participation in these projects was perceived to have increased their levels of social contact. In Hampshire, 75% of participants said that the project had enabled them to improve contact with friends and family and 17% said that activities had helped them connect with new people.

In Nottingham, several young people created a youth council to develop a more advanced game and planned to enter it into a competition. Project leads reported witnessing a great deal of enthusiasm to create something together, and feedback from participants supports that view.

“I’d have to say that Storysmash helped me find my love for coding again and it’s definitely helped me be more social, even if it was daunting at first. Having a group project has been really fun and inspiring.” Participant from Storysmash

Improved health and wellbeing

Many project leads documented or observed perceived increases in participants’ wellbeing, often linking this to perceived increases in social contact, confidence and employability, as well as access to new opportunities via digital tools. Examples across projects range from non-native participants making friends and overcoming depression, to those experiencing physical or learning disabilities or mobility issues getting out and about more, or feeling more useful to friends and family.

In Sandwell, 95% of participants strongly agreed or agreed that the project had increased their wellbeing. In Barnsley, 71% of participants felt that having access to this technology had been beneficial to their wellbeing, with over half finding they used it more than they thought they would.

Cluster 3: Families and wellbeing

A total of 6 LOFE-funded projects had a significant focus on activities aimed at increasing wellbeing among individuals and families (Figure 9).

Figure 9: overview of projects within the families and wellbeing theme

Projects within this cluster:

- aimed to address a lack of community engagement with libraries and prevalent issues within their local areas which ranged from low levels of literacy and digital literacy, to low levels of parenting support and attainment in children, and rising number of mental health challenges

- ran a wide range of activities that were designed to increase engagement with libraries, improve participants’ access to information and levels of confidence in engaging with libraries (specifically through co-production), as well as improve their physical, emotional and mental wellbeing

While the outcomes of some of these activities overlap with those of other clusters (e.g. increased literacy, increased confidence in engagement with literature, arts and culture), the focus of these projects has been on using these activities as tools to engage families and ultimately improve participants’ wellbeing.

The text below provides an overview of the projects’ local priorities, target groups and approaches to engagement, and a brief overview of the activities undertaken. Where projects are hyperlinked (underlined), this links to posts written by projects that have been published on the Taskforce blog.

East Sussex

What local issues did funded projects address?

- aimed to support various groups of people in vulnerable situations (affected by unemployment, poverty, mild mental health problems)

- focused on communities (both of people and place) in areas of high deprivation

- Intended to trial new approaches to inform their new strategy

Who were the target groups and how were they engaged?

- 4 different strands targeted towards groups:

- adults and families with children and teenagers who wanted to improve their mental wellbeing, engaged through partners and promotional events

- a well-established community of refugees and migrants in the Hastings area with limited English skills, engaged through a local drop-in centre

- people with visual impairments, engaged through work with local blind societies and word-of-mouth

- young people in secondary schools and Hastings, engaged directly or through community groups

- 2 additional strands addressed digital literacy and are included within this report under the digital cluster

What were the main activities?

- developed wellbeing boxes that, though originally intended for adults, were expanded to families and children and teenagers - this included stress balls, wellbeing journals, colouring books; information signposting to other services; and launch events

- dual language rhyme time and story times with refugees and migrants

- bought hardware and software and held sessions to support visually-impaired people to read and be more independent; recruited visually-impaired volunteers to train others on equipment

- creative writing workshops held by writer-in-residence

Essex

What local issues did funded projects address?

- many areas experiencing high unemployment, contributing to low levels of parental support and child attainment, and high referral rates for speech and language delay

- aimed to develop a space for a range of services and integrate the service offers of Chelmsford library and the local Children’s Centre

Who were the target groups and how were they engaged?

- the space has been created for parents, carers, children and young people (pre-birth to 19) with the help of 2 contracted partners: Barnardo’s and Virgin Care Limited

- participants were not specifically recruited to take part in any activities

What were the main activities?

- redesigned an inspirational, innovative space to provide a range of services that support learning, digital literacy, health, wellbeing and cultural enrichment

- delivery of other activities had not commenced at the time of the evaluation

Luton

What local issues did funded projects address?

- low levels of community engagement among a wide range of vulnerable people

Who were the target groups and how were they engaged?

- the project aimed to create a ‘cradle-to-grave’ pipeline of engagement in the community, targeting a wide range of irregular and non-users of library services

- recruited volunteers and engaged with partner organisations and artists to co-produce 3 spaces for teens, children, and an area dedicated to health and wellbeing - also engaged a range of partners to use the health and wellbeing space for their own activities

What were the main activities?

- refurbished 3 spaces through co-production with service users and/ or partners

- co-production involved focus groups and consultations with service users and partners

- used social media to engage volunteers through a system of ‘challenges’ (useful activities that would be taken on by skilled volunteers to help existing staff)

Sefton

What local issues did funded projects address?

- create a ‘human library’ of volunteers and partnerships to build community engagement

- address issues related to poor mental health and social isolation in one of the borough’s most deprived areas

- high number of older people, disabled people and young people experiencing disadvantage

Who were the target groups and how were they engaged?

- adults who are at greater risk of social isolation and poor mental health issues (with an emphasis on unemployed adults, carers, new and lone parents)

- target group was expanded to include older people who identified themselves as lonely and isolated, as well as children

- participants were recruited through local paper advertisements, community groups, existing or new partners, as well as promoting activities to existing library users

What were the main activities?

- a series of creative, artist-led programmes aimed at uncovering local talents, who became volunteers and led various sessions with participants

- the sessions included story-time tea toast (as snacks were observed to improve engagement), cooking in the library, podcasting, glazing ceramics, flower arrangement workshops and yoga, among others

Staffordshire

What local issues did funded projects address?

- low percentage of children who have access to universal education provision; low levels of school-readiness

- working to reduce the number of children entering the local authority system

Who were the target groups and how were they engaged?

- parents or carers of babies, toddlers and pre-schoolers, identified with the help of the county council’s Early Years Commissioning Lead, early years providers, Family Support Workers and other local partners who work with young parents

What were the main activities?

- co-produced 7 activity boxes with parents through a series of focus groups and workshops - these included resources and suggested activities for target groups, as well as information that signposted to other services

- other activities, such as stories and song, accompanied the wellbeing boxes and promoted group cohesion

Tameside Libraries

What local issues did funded projects address?

- low levels of literacy among adults in 4 of Tameside’s most deprived neighbourhoods

- aimed to improve early years’ school readiness

- low engagement with libraries and with cultural activities

Who were the target groups and how were they engaged?

- families with pre-school children or carers of pre-school children from more deprived areas, engaged thorough partners such as early years providers and voluntary and council bodies (children centres, networks for children looked after), as well as health and arts organisations

- the recruitment involved intense outreach activities, as well as marketing and advertising - project leads report that word-of-mouth from early participants was also an important enabler

What were the main activities?

- held interactive storytelling sessions, ran by a team of actor/musicians

- recruited a writer and illustrator to to-create a series of 4 pictures books with children and their families; these were printed and published professionally

- partnered with the Lowry Theatre and the Halle Orchestra from Manchester to hold special performances and workshops for the regular attendees

Two other projects also had elements which related to the families and wellbeing theme:

Table 3: Other projects of relevance to the families and wellbeing cluster.

| Project name | Main cluster | Families and wellbeing crossover |

| Plymouth | Literature and creative expression | Aimed to combat holiday hunger among children experiencing disadvantage and increase family engagement with the library. Targeted children and families at 6 schools in Plymouth. Lunch at the Library and pop-up library sessions, which offered healthy free lunches and included family crafts and coding activities. |

| Stockton | Makerspaces | Aimed to address health issues identified in various communities (e.g. dementia, visual difficulties, autism). Targeted people with specific needs, experiencing a range of health-related conditions, engaged through partners such as Dementia Hub. Built a sensory room (‘Imagination Station’), with projection facilities along 3 panels of the wall, where people can experience a range of activities, from interactive storytelling to videos and aromas. |

Impacts on individuals / service users

Increased knowledge among people experiencing disadvantage of how to support their own and their families’ wellbeing

All the spaces and activities created by projects within this cluster were aimed at supporting this outcome. Available data suggests that this has either been achieved or is on track to being achieved once the changes (redesigned spaces or new activities) have been bedded in.

Libraries have attempted to capture their impact in various ways. For example, all the wellbeing boxes created at East Sussex Libraries contained feedback forms, which participants were asked to complete. The questions ranged from asking about any positive outcomes that participants and their families experienced after borrowing the boxes, to asking about overall impressions about their contents and suggestions for improvement.

“The wellbeing box is an excellent idea. I found it particularly good for getting you to think about different aspects of your ‘wellbeing’. It offers way more than I expected.” Project participant, East Sussex

As shown below, the co-production process involved in creating the wellbeing boxes in East Sussex and Staffordshire Libraries was also an important part of increasing participants’ knowledge:

93% of self-reflection sheets collected in Staffordshire Libraries show that the co-production sessions improved participants’ knowledge on how to support child development.

“I’m more mindful to [take] a few minutes of quiet to listen to my child playing; allowing her to just make [things], even if it’s not what I thought or wanted. I don’t need to control the situation, just enjoy the process with her.” “I learned that it’s playing with my kids that is important – not what you play (with)… [and] not to keep stressing about how he’s doing, just enjoy him growing and learning.” Project participant, Staffordshire

Both East Sussex and Staffordshire Libraries reported that throughout their projects, demand for the wellbeing boxes increased, with various partners asking for the resources to use with their own customers. This demand, as well as the number of loans on the boxes, suggest a raised level of awareness and knowledge about wellbeing among the beneficiaries.

In Luton Libraries, the Well & Wise space (a dedicated space co-created with health providers and other health organisations) was opened in February 2018. It offers partners the possibility to hold 17 sessions with customers per week. At the time of the evaluation there was insufficient data to make a meaningful analysis of trends and impacts on participants’ knowledge, but feedback from health providers shows that they are finding the use of the space invaluable in engaging with customers:

“An unstructured session as we establish our presence at the library with good interest shown in our service” Red Cross Connecting Communities

Improved confidence and mental wellbeing

Most projects provided anecdotal evidence of increases in the levels of confidence and mental wellbeing among participants. For instance, the writer in residence employed by East Sussex libraries reported perceived increases in the confidence of participants, as shown in the case study below.

Case study: increased confidence

Maria attended 3 creative writing workshops with her mother. During the workshops, the writer in residence engaged participants in conversations about their feelings and their use of libraries. At first, Maria was not confident and would not speak aloud in the sessions, letting her mother speak for her. By the end of the 3rd workshop, she approached the facilitator to thank him for everything she had learned.

This example illustrates a common outcome reported by many other libraries. The project leads at East Sussex also reported seeing a great impact on the quality of life of visually impaired people, although no primary data exists to support this.

Furthermore, several project leads reported noticing an effect on participants’ general levels of wellbeing and happiness. While project leads reported collected some feedback locally (or in their own evaluation), there was limited primary data for this evaluation. Anecdotal feedback (below) from one project lead at Stockton Libraries suggests that the immersive Imagination Station is helping to ease the difficulties of people living with anxiety of dementia:

“[There is] a gentleman who uses our dementia café at Thornaby every month… he lives with dementia and often experiences anxiety and aggression, but finds the Imagination Station the perfect solution. He made a point of telling our Health Librarian that nothing has helped him deal with the challenges he faces more than sitting in the room experiencing the images, sounds, videos and aromas that we programme in. We were very keen to see what kind of impact this facility would have on mental health and here was a direct example” Project Lead

Feedback forms from one strand of Tameside’s project suggest that the sessions contributed to boosting the confidence and self-esteem of adults and children (based on the evaluation undertaken by the University of Salford). Project leads from Sefton Libraries have also provided anecdotal reports that all participants (who self-identified as suffering from depression or anxiety, or simply leading stressful lives) noted a positive change in their wellbeing and happiness levels.

Reduced social isolation

Sefton Libraries and East Sussex Libraries focused particularly on reducing social isolation among certain target groups. While this outcome is particularly difficult to measure, reported accounts from participants and direct feedback from project leads who were interviewed suggest that the activities have had the desired effect.

Sefton project leads reported several participant stories about how taking part in the Human Library enabled them to meet new people from their neighbourhood, improved their sense of belonging and reduced their isolation. There are similar accounts from East Sussex:

“We worked with 3 or 4 people where the improvement to their quality of life was immediate. Some of the visually impaired people we worked with had lost their sight early, and felt marginalised and excluded. They are getting a lot out of working with the equipment and volunteers; they are building friendships and a support network. We also did work with home educational groups… children built links they didn’t have due to being home-schooled.” Project Lead

Increased engagement with creative and cultural activities

To build an inspirational space for children and young people, the team at Essex libraries ensured that people from these target groups were engaged in the design of the space. Project leads reported that all attendees were overwhelmingly positive about the opportunity to take part and influence the look and feel of the new space.

In Luton Libraries, a group of year 8 students co-produced the new adolescent space and created visual artwork that related to them and their peers. Working with an artist encouraged their interaction with books, social media and augmented reality, which helped create a new and vibrant environment. Project leads reported that all of the students involved in this project felt their contribution made a positive impact and the majority of students stated that taking part in this project encouraged them to visit the library more. It is believed that the co-production process helped to create a new audience for that space by involving local young people in the project and developing their knowledge of library literature and facilities, and that the project will form a legacy of ongoing engagement with them.

Furthermore, the Library Makers website and challenge structure aimed to stimulate creative outputs by volunteers, in order to co-produce resources such as items for children’s trails, design colouring pictures or artwork.

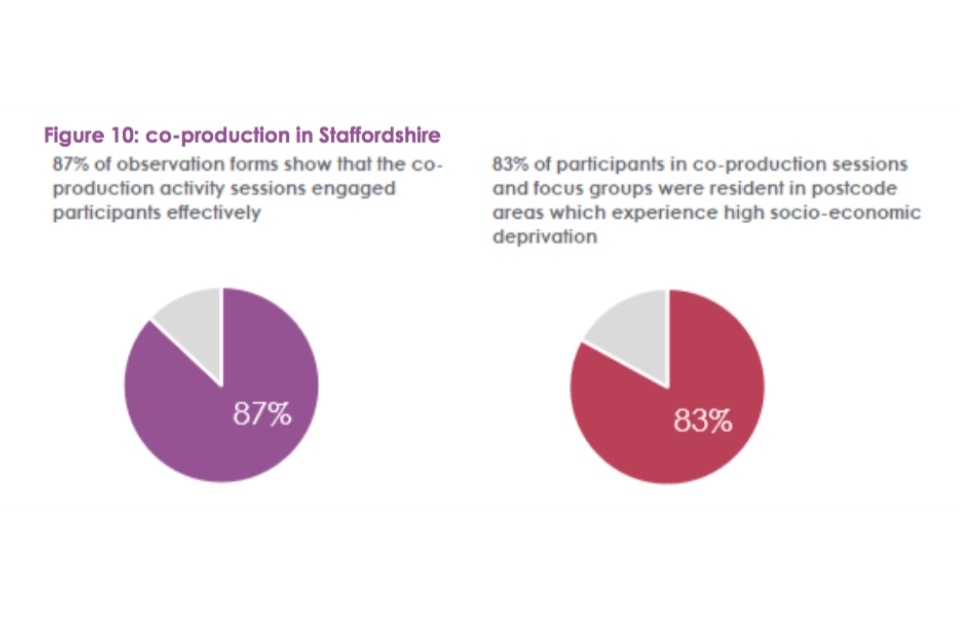

These outcomes are not unique to Luton, with project leads from Staffordshire also reporting that through its nature, co-production had helped improve the engagement of those involved:

Figure 10: co-production in Staffordshire

Project leads from Tameside also reported that their storytelling activities, theatre trips and Halle orchestra workshops had created high levels of engagement among participants, with 30% of people engaging with such activities for the first time.

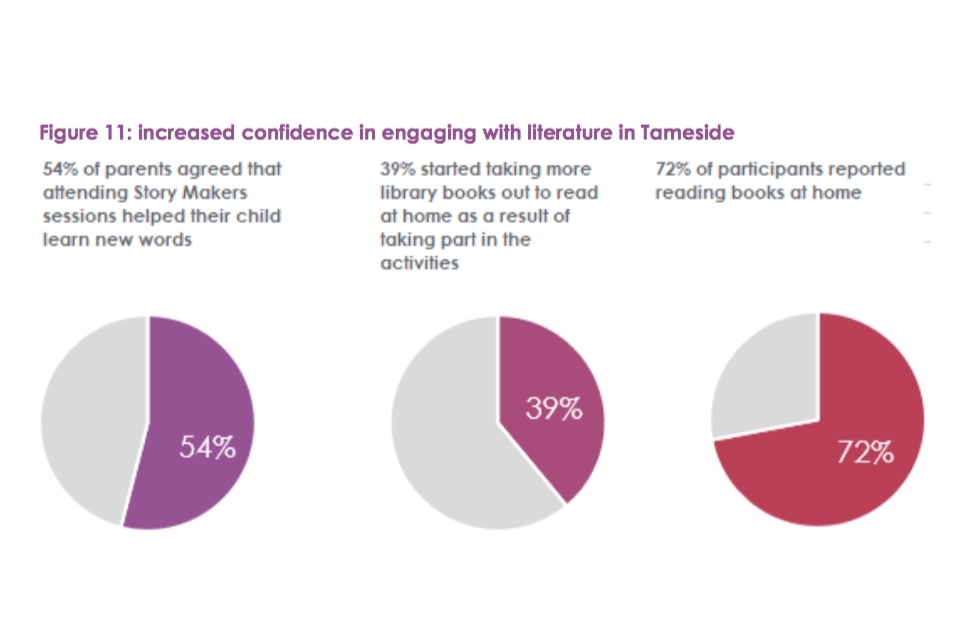

Increased confidence in engaging with literature and creative expression

Both projects in Tameside and East Sussex worked with writers with a view to improving literacy and engagement with literature among target groups. As shown below, participant feedback forms from Tameside indicated that:

Figure 11: increased confidence in engaging with literature in Tameside

The Writer in Residence employed by East Sussex libraries also provided examples of participants who were worried about not being able to write, who had subsequently turned in pages of writing after taking part in the workshops. Observations from staff at East Sussex libraries also suggested that children and mothers from refugee communities had improved their English language skills.

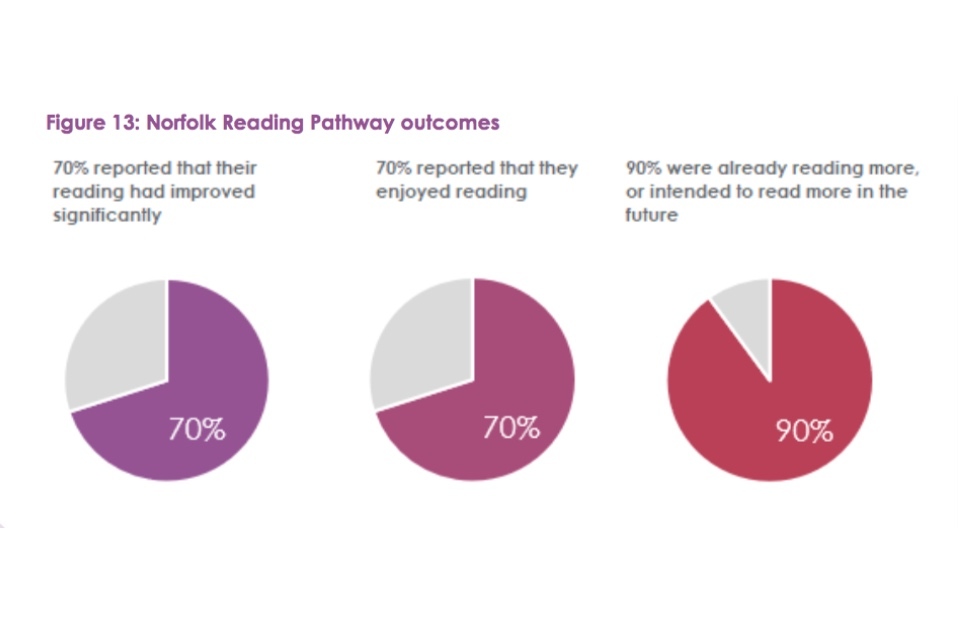

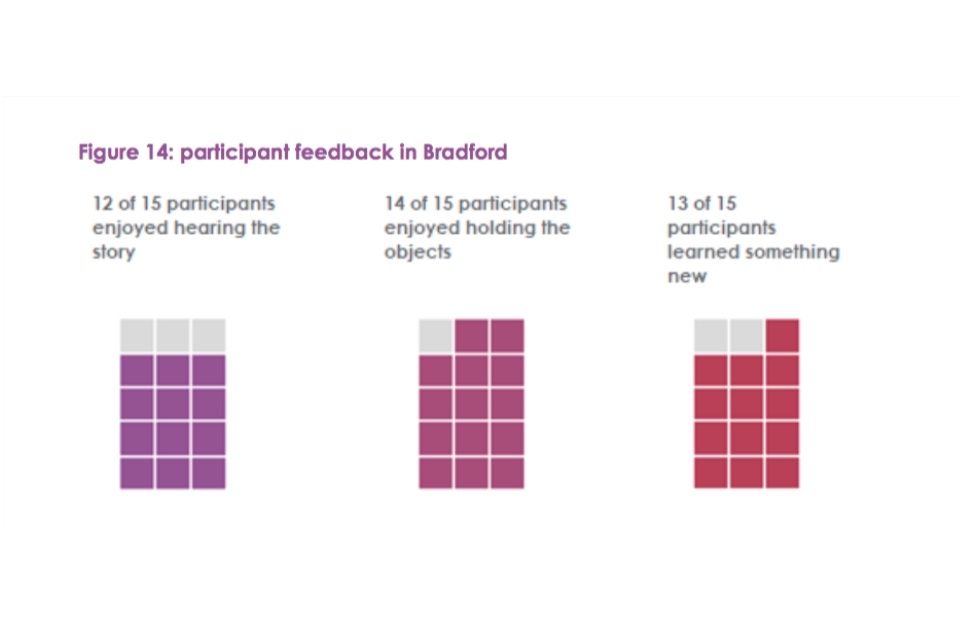

Cluster 4: Literature and creative expression

A total of 6 LOFE-funded projects focused on engaging vulnerable and marginalised groups in their communities and bringing literature to life through storytelling activities and opportunities for creative expression[footnote 6] (Figure 12).

Figure 12: overview of projects grouped within the literature and creative expression cluster

Projects within this cluster typically:

-

aimed to address low levels of participation in library services in areas that experienced multiple disadvantages, including high levels of deprivation - these areas, it was often felt, lacked adequate service provision for vulnerable and marginalised groups

- worked across a wide range of target groups, but with a specific focus on vulnerable and marginalised groups that were either irregular users or non-users of library services, or could access only limited services - this typically included children and adults with special educational needs and families from lower income backgrounds

- ran a wide range of creative activities that were designed to bring literature to life through interactive exercises and environments

The text below provides an overview of the projects’ local priorities, target groups and approaches to engagement, and a brief overview of the activities undertaken. Where projects are hyperlinked (underlined), this links to posts written by projects that have been published on the Taskforce blog.

Bournemouth / Poole, Wiltshire, Dorset, South Gloucestershire, Bristol (SW Region of Readers)

What local issues did funded projects address?

- targeted communities experiencing disadvantage in Bournemouth, Bristol, Dorset, Poole, South Gloucestershire and Wiltshire

- all target communities experience poor health outcomes

- most communities displayed high levels of deprivation for older people; low levels of educational achievement, skills and employment amongst the working age population; as well as social isolation and loneliness

Who were the target groups and how were they engaged?

- targeted adults, families, digitally disadvantaged adults and irregular library users

- network of 9 partners across library and literature development sectors

- outreach activities by local library staff and community volunteers to engage people face-to-face

- direct marketing via social media

What were the main activities?

- a network of shared reading groups where participants relax, share stories, read aloud or just listen