Trade in goods: guidance for enforcement authorities on complying with the UK Internal Market Act 2020

Updated 16 February 2022

Disclaimer

This guidance clarifies and explains the practical operation of the market access principles as outlined in Part 1 of the UK Internal Market Act (UKIMA) 2020. It does not create or amend any legal obligations. Enforcement authorities should also refer to relevant goods legislation, and the UKIMA 2020 itself, when giving effect to the market access principles.

This guidance is for enforcement authorities in all parts of the UK which are responsible for the regulation of goods. There is different guidance if you are a trader selling goods.

Overview: the UK Internal Market Act 2020

On 1 January 2021, following the end of the transition period, EU rules that govern how each UK nation trades with the others fell away, and powers previously exercised at the EU level flowed directly to the UK government and the devolved administrations in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland.

To ensure traders can continue to sell their goods freely across the UK without barriers, the UK Internal Market Act 2020 (UKIMA) introduces the market access principles of mutual recognition and non-discrimination.

The mutual recognition principle means that if goods comply with relevant statutory requirements in the part of the UK where they were produced in or imported into, they can be sold in any other part of the UK without having to comply with any differing statutory requirements there.

The non-discrimination principle means that a statutory requirement will have no effect if, and to the extent that, it either directly or indirectly discriminates against goods with a relevant connection with another part of the UK.

It is important that enforcement authorities understand when these principles apply so that they continue to enforce existing goods regulation against traders in a lawful way. This guidance seeks to aid that understanding.

Enforcement authorities only need to assess whether the market access principles apply if they find goods for sale that appear to be non-compliant with the relevant statutory requirements of the part of the UK in which those goods are sold.

Check which regulatory regimes are affected by the market access principles

The mutual recognition principle does not apply to regulatory divergence within the UK which existed on 30 December 2020 (that is to requirements that were in force in a part of the UK on or before 30 December 2020 which differed from the requirements that were in force elsewhere in the UK on or before that date). The non-discrimination principle does not apply to all requirements that were in force on or before 30 December 2020.

If such requirements are amended in a way that substantively changes their effect or outcome (for example changes to requirements that traders must follow to sell goods), the market access principles would then apply. Minor amendments that do not alter a requirement’s effect or outcome would remain out of scope (for example changes which do not materially affect what a trader must do to sell goods).

Furthermore, the market access principles will have no effect in practice for goods from Great Britain that are sold within Great Britain where requirements are the same for those goods across Great Britain (England, Scotland, and Wales).

For goods moving from Great Britain to Northern Ireland, the provisions of the Northern Ireland Protocol take precedence over the market access principles. This means that any differing EU requirements on goods sold in Northern Ireland which apply as a result of the Protocol will have to be complied with.

For ‘qualifying Northern Ireland goods’ moving from Northern Ireland to Great Britain, the market access principles apply. Read the definition of ‘qualifying Northern Ireland goods’.

Definitions of sale and goods for the purposes of the market access principles

The concepts of ‘sale’ and ‘goods’ underpin the market access principles.

‘Sale’ means supplying goods in almost any way. It can include:

- exchange for money

- trial samples

- free gifts

- goods bartered

- goods that are leased or hired

‘Sale’ can also mean agreeing to sell, advertising or storing for sale.

Supplies of goods for the purpose of carrying out a public function (for example supplies of medical equipment or food by public health services) are not defined as a sale.

Some enforcement authorities may be more familiar with the terms ‘placing goods on the market’ or ‘making goods available on the market’. The definition of ‘sale’ for the purposes of the market access principles is broader than both.

‘Goods’ are defined widely to include any tangible movable thing (except water or gas that isn’t sold in limited quantities).

Check if the sale of goods qualifies for the benefits of the mutual recognition principle

Goods moved between parts of Great Britain (England, Scotland, and Wales)

The mutual recognition principle enables goods which comply with the relevant statutory requirements in the part of Great Britain they were produced in or imported into (for example Scotland) to be sold in any other part of Great Britain without having to comply with the relevant statutory requirements in that other part (for example Wales or England).

Goods moved from Northern Ireland into Great Britain

The mutual recognition principle applies if the goods in question are ‘qualifying Northern Ireland goods’.

If the goods are not ‘qualifying Northern Ireland goods’, mutual recognition does not apply. The goods will have to comply with the relevant statutory requirements of the part of Great Britain where they are first moved into. If they do, the goods can subsequently be sold in another part of Great Britain in reliance on the mutual recognition principle.

Goods moved from Great Britain into Northern Ireland

Mutual recognition does not apply to goods sold in Northern Ireland that need to comply with relevant EU rules under Annex 2 to the Northern Ireland Protocol.

If the goods are not regulated by requirements that apply to Northern Ireland under the Northern Ireland Protocol, mutual recognition applies.

Exclusions from the mutual recognition principle

Some areas of goods regulation are excluded from the mutual recognition principle and in these cases goods will need to comply with the rules in the part of the UK in which they are sold. Exclusions include certain regulations related to:

- controlling pests or diseases

- unsafe food or animal feed

- chemicals

- pesticides

- fertilisers

Legislation relating to the imposition of any tax, rate, duty or similar charge is also excluded.

Further details of these exclusions and the conditions that have to be met for the exclusions to apply are set out in Schedule 1 of the UKIMA 2020.

Areas of goods regulation may in future be added to or removed from this Schedule 1 list by the Secretary of State through a Statutory Instrument. For example, this could be done to give effect to an agreement within a Common Framework.

Giving effect to the mutual recognition principle

Part 1 of the UKIMA 2020 (which deals with goods) does not introduce any new enforcement bodies, powers, or penalties, but instead relies on enforcement provisions in existing goods regulation to give effect to the market access principles.

In line with existing guidance on best practice, for example the Regulator’s Code, Food and Feed Codes of Practice, and the Scottish regulators’ strategic code of practice, enforcement authorities should assess and/or enforce compliance with goods regulations, taking account of the market access principles, in a pragmatic, risk-based, and proportionate way. Doing so minimises the regulatory burden for traders.

Should an enforcement authority identify goods for sale that appear to be non-compliant with local regulations (and are not subject to an exclusion set out in Schedule 1) it should follow the below two steps to assess whether the sale of those goods qualify for the mutual recognition principle:

-

Determine where in the UK the goods were produced in or first imported into (England, Scotland, Wales or Northern Ireland).

-

If the goods have been moved from another part of the UK, determine whether they comply with the relevant statutory requirements for that other part of the UK.

To make this assessment, (and in line with existing information-gathering powers) enforcement authorities should, in the first instance, contact the trader to ask whether they are relying on the mutual recognition principle, providing a link to UKIM guidance for traders to facilitate a response. If a trader states they are relying on mutual recognition, they should provide accompanying evidence to demonstrate compliance by showing where in Great Britain the goods were produced in or first imported into and can be lawfully sold, or whether they are ‘qualifying Northern Ireland goods’.

Subject to the provision of adequate evidence to support the trader’s reliance, it will then, in most cases, be for the enforcement authority to determine whether the goods comply with the relevant requirements in that other part of the UK (working with the most appropriate enforcement authority in that other part if necessary). If they do, mutual recognition will apply.

Where the trader has a direct Primary Authority partnership, the primary authority, drawing on its detailed knowledge and understanding of the business and its compliance systems, may be able to provide assistance to enforcement authorities on the applicability of the mutual recognition principle.

Step 1: Determine where goods were ‘produced in’ or ‘imported into’

To assess whether the sale of goods qualifies for mutual recognition, it is first necessary to determine if the goods came from another part of the UK – that is where they have been ‘produced in’ or first ‘imported into’, or in the case of Northern Ireland, whether the goods meets the definition of ‘qualifying Northern Ireland goods’.

‘Produced in’

For the purposes of the mutual recognition principle, goods are regarded as ‘produced in’ a part of the UK (if not wholly produced there), if the most recent significant production step, which is also a regulated step, has occurred in that part.

A production step is regulated if it is the subject of a statutory requirement in the part of the UK it took place in, or if it materially affects whether the good can lawfully be sold in that part. For example, if there was a requirement introduced in England that flour be fortified with an additional particular vitamin, the adding of that vitamin to flour would constitute a regulated step.

A production step is significant if it affects the character of the goods or their purpose (for example the baking of a loaf of bread would constitute a significant step). Production steps not considered to be significant (whether or not they are regulated), include:

- activities carried out specifically to ensure goods do not deteriorate before being sold (such as maintaining them at or below a particular temperature);

- activities carried out solely for purposes relevant to their presentation for sale (such as cleaning or pressing fabrics or sorting different coloured items for packaging together);

- activities involving communication with a regulatory or trade body (such as registering the goods or notifying the goods or anything connected with them or their production);

- activities carried out for the purpose of testing or assessing any characteristic of the goods (such as batch testing a pharmaceutical product);

- packaging, labelling, stamping or marking of goods (except if it is fundamental to the character of the goods or their purpose).

Suggested approach to compliance

Enforcement authorities should take a pragmatic, risk-based, and proportionate approach to the types of evidence that traders can rely on to demonstrate the location of production.

In most cases, existing, readily available documentation which provides the above information should be sufficient to evidence the location of production, or that goods are ‘qualifying Northern Ireland goods’. For example, for manufactured goods a technical file or dispatch note may be sufficient, while for agri-food an invoice or labelling which shows where goods were produced or grown.

If a trader does not have access to suitable documentation to evidence the location of production, or that goods are ‘qualifying Northern Ireland goods’, enforcement authorities should consider instead requesting evidence regarding who supplied the goods, in order to move up the supply chain as necessary until it is possible to determine the location of production.

Enforcement authorities should be aware that if a manufacturer’s address is affixed to goods, this may not necessarily correspond with where the last significant and regulated production step took place.

‘Imported into’

For the purposes of mutual recognition, goods are ‘imported into’ the part of the UK that hosts their geographical point of first entry into the UK, though how that geographical point is determined varies depending on whether the goods are brought by sea, by air or by land. Goods brought by sea are imported when the ship carrying them enters the limits of the port where they are discharged, goods brought by air are imported when they are unloaded, and goods brought by land are imported when they enter the UK. As the definition of ‘imported into’ is based on the geographical point of first entry rather than customs formalities, the presence of a ‘Freeport’ is not relevant for mutual recognition.

So, for example, if goods arrive in the UK by ship via the port of Felixstowe, they are regarded as having been ‘imported into’ England when the ship carrying them enters the limits of Felixstowe port. The goods would then need to comply with the relevant requirements for sale in England to benefit from the mutual recognition principle and be sold in Scotland, without necessarily complying with relevant requirements in Scotland. If the goods ‘imported into’ England comply with the Scottish rules but not the English rules, the goods could be lawfully sold in Scotland but cannot rely on the mutual recognition principle to be sold elsewhere in the UK without meeting the rules there.

Goods that are produced in or first imported into one part of the UK (the originating part) and are then subsequently exported outside of the UK before being re-imported back into the UK without any substantive changes, are still considered as being produced in or imported into the originating part.

If goods (including ‘qualifying Northern Ireland goods’) were imported into one part of the UK and then underwent a significant and regulated production step in a second part of the UK, the goods would be treated as having been produced in that second part.

Suggested approach to compliance

As with the location of production, enforcement authorities should take a pragmatic, risk-based, and proportionate approach to the types of evidence that traders can rely on to demonstrate the location of importation, or that goods are ‘qualifying Northern Ireland goods’. In most cases existing, readily available documentation like a customs declaration which shows port of entry, should be sufficient.

If a trader does not have access to suitable documentation to evidence the location of importation, or that goods are ‘qualifying Northern Ireland goods’, enforcement authorities should consider instead requesting evidence regarding who supplied the goods in order to move up the supply chain as necessary until it is possible to determine the location of importation.

Enforcement authorities should be aware that if an importer’s address is affixed to goods, this may not necessarily correspond with the part of the UK the goods were first imported into.

Step 2: Determine if goods comply with the relevant requirements for mutual recognition

If goods comply with the ‘relevant requirements’ of the part of the UK where they were produced in or imported into (or if they meet the definition of ‘qualifying Northern Ireland goods’), they can benefit from the mutual recognition principle. The goods do not actually need to be sold in that part of the UK to benefit from the mutual recognition principle, just meet the relevant requirements which apply there if they were to be sold. For example, where goods are imported into Wales but moved to England where they are sold - if the goods meet the relevant requirements in Wales they would benefit from the mutual recognition principle and could be lawfully sold in England.

Relevant requirements for the mutual recognition principle are statutory requirements imposed by legislation that must be satisfied before the goods can be sold or outright ban their sale. They must relate to one or more of the following:

a) characteristics of the goods themselves (such as their nature, composition, age, quality or performance);

b) presentation of the goods (such as the name or description applied to them or their packaging, labelling, lot-marking or date-stamping);

c) anything connected with the production of the goods or anything from which they are made or is involved in their production (including the place at which, or the circumstances in which, production or any step in production took place);

d) anything relating to the identification or tracing of an animal (such as marking, tagging or micro-chipping or the keeping of particular records);

e) the inspection, assessment, registration, certification, approval or, authorisation of the goods or any other similar dealing with them;

f) documentation or information that must be produced or recorded, kept, accompany the goods, or be submitted to an authority;

g) anything not falling within paragraphs (a) to (f) which must (or must not) be done to, or in relation to, the goods before they are allowed to be sold.

Statutory requirements that affect the manner or circumstances in which goods are sold (such as where, when, by whom, or to whom the goods can be sold, the price of the goods, or other terms on which they may be sold) are not ‘relevant requirements’ for the purposes of mutual recognition. These ‘manner of sale’ requirements are instead covered by the non-discrimination principle. For example, a ban on selling particular goods to under 18s would be a ‘manner of sale’ requirement; whereas a requirement to make the goods in a particular way would be a ‘relevant requirement’ under the mutual recognition principle.

There is however, one exception to this, where ‘manner of sale’ requirements will be considered ‘relevant requirements’ for the purposes of mutual recognition. This is where a ‘manner of sale’ requirement is artificially designed to avoid the mutual recognition principle (for example, where a restriction on the hours of the day in which goods could be sold was so extreme that it left businesses with no practical chance of selling the goods).

Suggested approach to compliance

In determining whether goods comply with the relevant requirements of the part of the UK where they were produced in or first imported into, the investigating enforcement authority should use existing networks and communication channels to engage with the most appropriate authority from that part of the UK to assess the evidence provided by the trader.

Where the trader has a direct Primary Authority partnership, the primary authority, drawing on its detailed knowledge and understanding of the business and its compliance systems, may be able to provide assistance to enforcement authorities in relation to the applicability of the mutual recognition principle.

If the traders’ evidence satisfies the investigating enforcement authority that the goods comply with the relevant requirements of the part of the UK where they were produced in or imported into, or that they are ‘qualifying Northern Ireland goods’, the goods can benefit from the mutual recognition principle and be lawfully sold.

If goods are shown not to comply with the relevant requirements of the part of the UK where they were produced in or imported into, or are not ‘qualifying Northern Ireland goods’, they cannot benefit from the mutual recognition principle.

In this case, an enforcement authority in that part of the UK may consider taking appropriate enforcement action against the trader for non-compliance with local requirements in line with their enforcement policy and existing powers in relevant goods regulation.

Should relevant legal tests be met enabling an enforcement authority to prosecute a trader for non-compliance with local requirements, it will be for the enforcement authority to prove that non-compliance in the usual way.

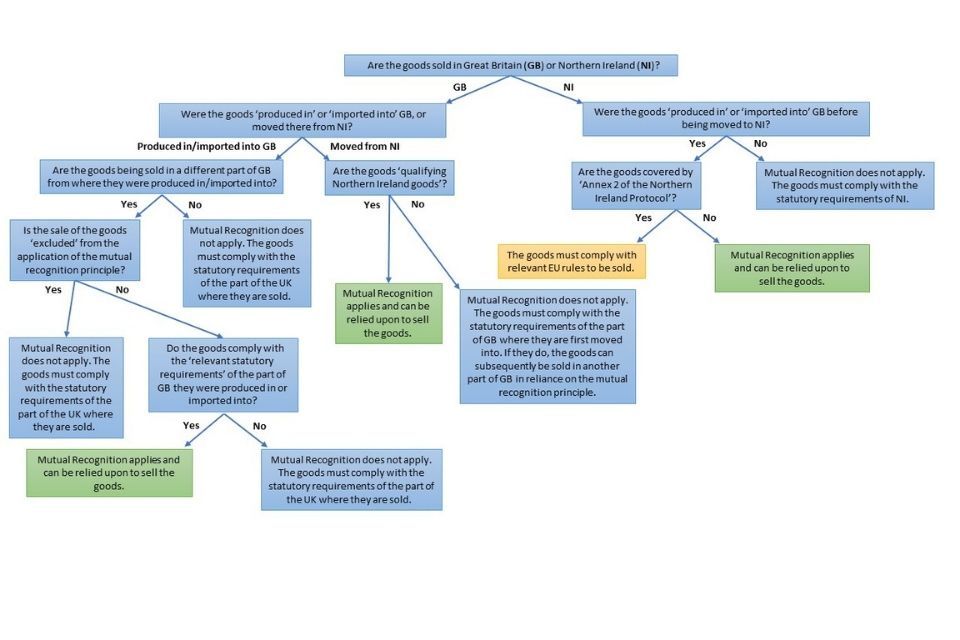

Flowchart to check whether the sale of goods qualifies for the mutual recognition principle

The following diagram outlines for illustrative purposes how to determine whether the sale of a good qualifies for the benefits of the mutual recognition principle.

Check if the non-discrimination principle applies to the sale of goods

The non-discrimination principle sits alongside and complements the market access principle of mutual recognition, applying to certain statutory requirements that fall out of scope of mutual recognition.

Under the non-discrimination principle, a relevant statutory requirement will have no effect if and to the extent that it either directly or indirectly discriminates against incoming goods (i.e. goods with a ‘relevant connection’ with another part of the UK).

Relevant requirements for the non-discrimination principle are defined as statutory provisions that apply to, or in relation to, goods sold in a part of the UK, and relate to any one or more of the following:

a) the circumstances or manner in which goods are sold (such as where, when, by whom, to whom, or the price or other terms on which they may be sold);

b) the transportation, storage, handling or display of goods;

c) the inspection, assessment, registration, certification, approval or authorisation of the goods or any similar dealing with them (unless failure to meet the requirement results in sale of the goods being prohibited, in which case it would fall under the mutual recognition principle);

d) the conduct or regulation of businesses that engage in the sale of certain goods or types of goods.

Goods are deemed to have a ‘relevant connection’ with a part of the UK if they, or any of their components:

- are produced in that part;

- are produced by a business based in that part (i.e. where its registered office is, its head office is or principal place of business is – assessed in that order); or

- come from, or pass through, that part before reaching the destination part.

Goods that are not ‘qualifying Northern Ireland goods’ do not have a relevant connection with Northern Ireland for the purposes of the non-discrimination principle.

Test for direct discrimination

Direct discrimination occurs when, due to the incoming goods having a relevant connection with another part of the UK, a relevant requirement applies to those goods but does not or would not apply to local goods; and places the incoming goods at a disadvantage relative to local goods. For example, a Welsh requirement that goods coming from Scotland or England must be chilled, but local goods produced in Wales do not.

Goods are put at a disadvantage if it is made in any way more difficult, or less attractive, to sell or buy the goods, or do anything in connection with their sale.

For the purposes of direct discrimination, ‘local goods’ are actual or hypothetical goods that lack the relevant connection of the incoming goods with the part of the UK they came from, but otherwise are materially the same as, and share the material circumstances of, the incoming goods. The inclusion of hypothetical goods covers a situation where, for example, goods are protected by an intellectual property right and are not yet available in both parts of the UK.

Exclusions from direct discrimination

In addition to the exclusion of legislation that relates to the imposition of any tax, rate, duty, or similar charge, a statutory requirement will not directly discriminate against incoming goods to the extent that it can reasonably be justified as a response to a public health emergency that poses an extraordinary threat to human health. Furthermore, where regulatory safeguards are needed to manage risks associated with the movement of pests or diseases, the non-discrimination principle may not apply.

The details of these exclusions are set out in paragraphs 1, 5, and 11 of Schedule 1 of the UKIMA 2020.

Suggested approach to compliance

In most cases, enforcement authorities should be able to make an independent assessment of whether a relevant requirement directly discriminates by examining if the requirement applies equally to both the local and incoming goods. Enforcement authorities should therefore generally be able to determine that directly discriminatory relevant requirements have no effect (in accordance with section 5(3) of the UKIMA 2020 if and when they are identified without needing to engage traders directly.

Test for indirect discrimination

Indirect discrimination occurs, in general terms, when a relevant requirement, which does not directly discriminate, disadvantages incoming goods compared to local goods and as a result has a significant adverse effect on competition for those goods.

For a relevant requirement to indirectly discriminate against goods connected with another part of the UK, all of the following must apply:

- it does not directly discriminate against the goods;

- it applies to, or in relation to, the goods connected with another part of the UK in a way that puts it at a disadvantage;

- it has an adverse market effect; and

- it cannot reasonably be considered a necessary means of achieving a legitimate aim.

‘Adverse market effect’

A relevant requirement has an adverse market effect if it puts goods connected with another part of the UK at a disadvantage (but not comparable local goods, or not to the same extent), and by so doing causes a significant adverse effect on competition for those goods. The goods will be at a disadvantage if it is made more difficult, or less attractive, to sell or buy them.

Comparable local goods are goods that are alike to the incoming goods in all respects (or closely resemble them), or could reasonably be said, from the view of a purchaser, to be interchangeable with them.

‘Legitimate aim’

Where a relevant requirement can reasonably be considered a necessary means of achieving a legitimate aim, it will not be indirectly discriminatory. Legitimate aims are:

- the protection of the life or health of humans, animals, or plants; and/or

- the protection of public safety or security.

Exclusions from indirect discrimination

In addition to the exclusion of legislation that relates to the imposition of any tax, rate, duty, or similar charge, a statutory requirement in, or made under, an Act of Parliament will not be taken to indirectly discriminate against incoming goods if the same or substantially the same requirement also applies in the part of the UK where the goods came from (and that requirement was also in, or made under, an Act of Parliament). Note though, that if the same requirement applied in, say, England and Scotland, but not Wales, the English or Scottish requirement could still indirectly discriminate against goods from Wales. Furthermore, where regulatory safeguards are needed to manage risks associated with the movement of pests or diseases, the non-discrimination principle may not apply.

The details of these exclusions are set out in paragraphs 1, 11, and 12 of Schedule 1 of the UKIMA 2020.

Suggested approach to compliance

Enforcement authorities should prioritise early, open, and constructive dialogue with traders to assess whether the indirect discrimination principle applies, given its highly context specific nature.

Enforcement authorities should take a pragmatic, risk-based, and proportionate approach to the types of evidence traders could rely on to demonstrate an ‘adverse market effect’, when determining whether a potentially indirectly discriminatory relevant requirement should not have effect in relation to incoming goods. As for assessing whether a relevant requirement can reasonably be considered a necessary means for achieving a legitimate aim, enforcement authorities should, in most cases, be able to make an independent assessment without engaging traders directly. As part of that assessment, enforcement authorities will need to consider the legislation itself and any communications from the relevant executive which indicate its purpose and intended effects.

Should relevant legal tests be met enabling an enforcement authority to take enforcement action against a trader for non-compliance with local regulations, it will be for the enforcement authority to substantiate its assessment of that non-compliance in the usual way. This will require it to show that the regulations do not directly or indirectly discriminate against the goods, where that is relevant.

Flowchart for determining whether direct or indirect discrimination applies

The following diagram outlines for illustrative purposes how to determine whether direct or indirect discrimination applies to the sale of goods.

More information

Contact

Email ukinternalmarket@beis.gov.uk if you have any questions about this guidance.